Abstract

Background

Omental cakes typically are associated with ovarian carcinoma, as this is the most common malignant aetiology. Nonetheless, numerous other neoplasms, as well as infectious and benign processes, can produce omental cakes.

Methods

A broader knowledge of the various causes of omental cakes is valuable diagnostically and to direct appropriate clinical management.

Results

We present a spectrum of both common and unusual aetiologies that demonstrate the variable computed tomographic appearances of omental cakes.

Conclusion

The anatomy and embryology are discussed, as well as the importance of biopsy when the aetiology of omental cakes is uncertain.

Keywords: Gastrointestinal, Malignancy, Infection, CT, Biopsy

Introduction

The greater omentum plays a unique role in intraperitoneal pathology and the corresponding computed tomographic (CT) imaging of that pathology. As a predominantly fat-containing structure within the abdomen, its inherent contrast on CT makes inflammatory, infectious, and neoplastic processes more apparent. In time, these processes result in a diffuse thickening of the omentum, such that it changes from a barely discernible fatty band to a mass that can displace underlying bowel from the abdominal wall, i.e., the so-called “omental cake”. This classic radiological sign and its nuances stem from the early 1900s surgical literature [1].

Ovarian carcinoma is the most common prototype malignancy to produce omental cakes; however, numerous other malignancies may have a similar or forme fruste appearance. Moreover, several infections and other uncommon disease states also can produce omental cakes. We present various usual and unusual aetiologies and imaging characteristics of omental cakes, as well as the anatomy and embryology of the greater omentum. The role of percutaneous image-guided biopsy is discussed when the cause of omental cakes is uncertain.

Embryology, anatomy, and pathophysiology

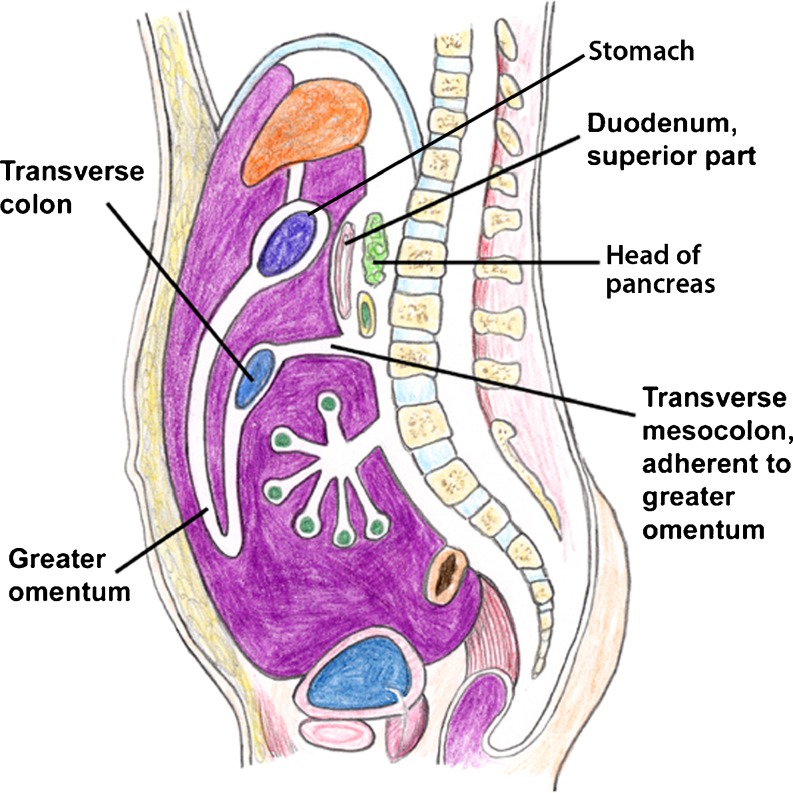

The greater omentum is a derivative of the dorsal mesogastrium, brought anteriorly by the counterclockwise rotation of the gut at 6 weeks of gestation. From the greater curvature of the stomach, two layers of peritoneum join and form an apron-like structure that hangs inferiorly anterior to the small bowel, then doubles back upon itself to fuse with the superior layer of the transverse mesocolon (Fig. 1) [2]. Laterally it extends to the pylorus or first portion of the duodenum on the right, and on the left is continuous with the gastrosplenic ligament. These four layers of variably apposed peritoneum may act either as an actual or potential anatomic space [3].

Fig. 1.

Schematic sagittal diagram demonstrating the anatomy of the greater omentum (Modified and reprinted with permission from [2])

The size of the greater omentum and its correlative CT appearance are largely dependent on the amount of fat it contains. The greater omentum also contains gastroepiploic vessels, lymphatics, and “milky spots”, or accumulations of immune cells that are comprised predominantly of macrophages [4]. These “milky spots” are involved in the clearance of pathogens from the peritoneum and serve as part of the “abdominal policeman” role of the greater omentum. They also are potential traps for intraperitoneal metastases, particularly by intraperitoneal seeding [5]. These areas are located throughout the peritoneum and are seen in the highest concentration in the greater omentum, explaining the high frequency of omental involvement in intraperitoneal disease processes (Fig. 2).

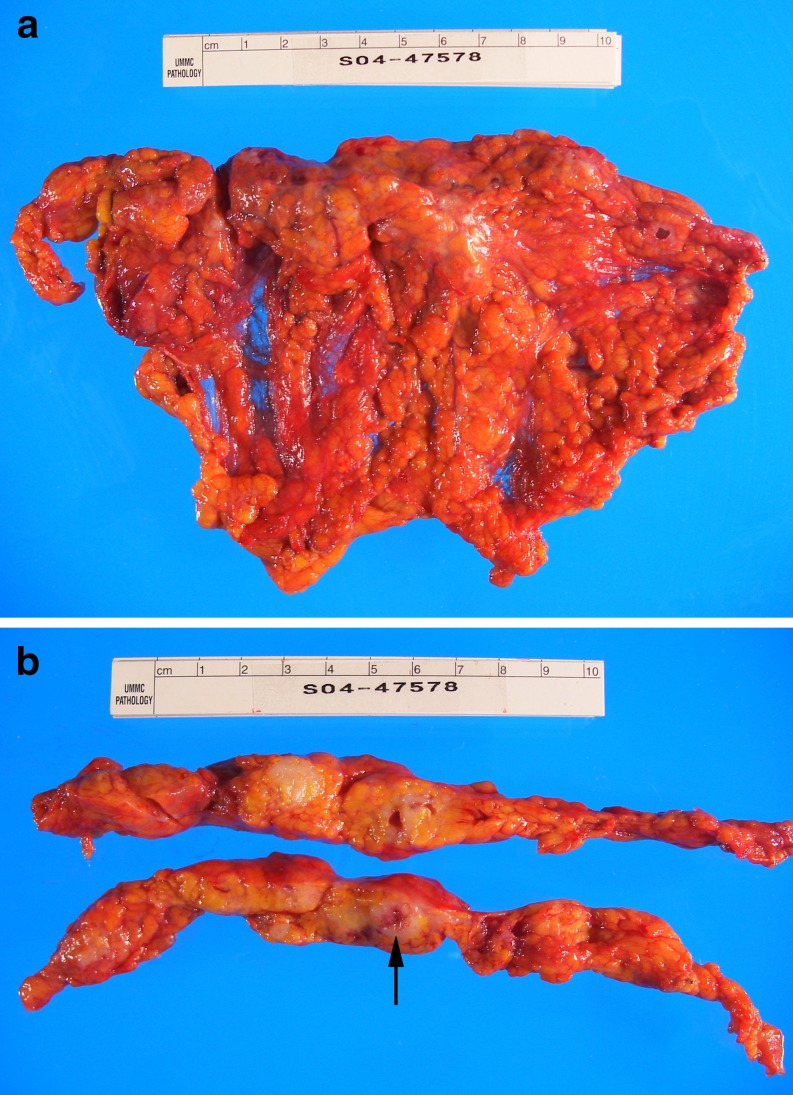

Fig. 2.

(a,b). Adenocarcinoma of the vulva in a 55-year-old woman. a Gross omental cake specimen with an 8-cm irregular firm nodular lesion at the superior border. b Transverse sections of the omentum show that the lesion is solid, tan-white with scattered foci of hemorrhage (arrow)

Imaging

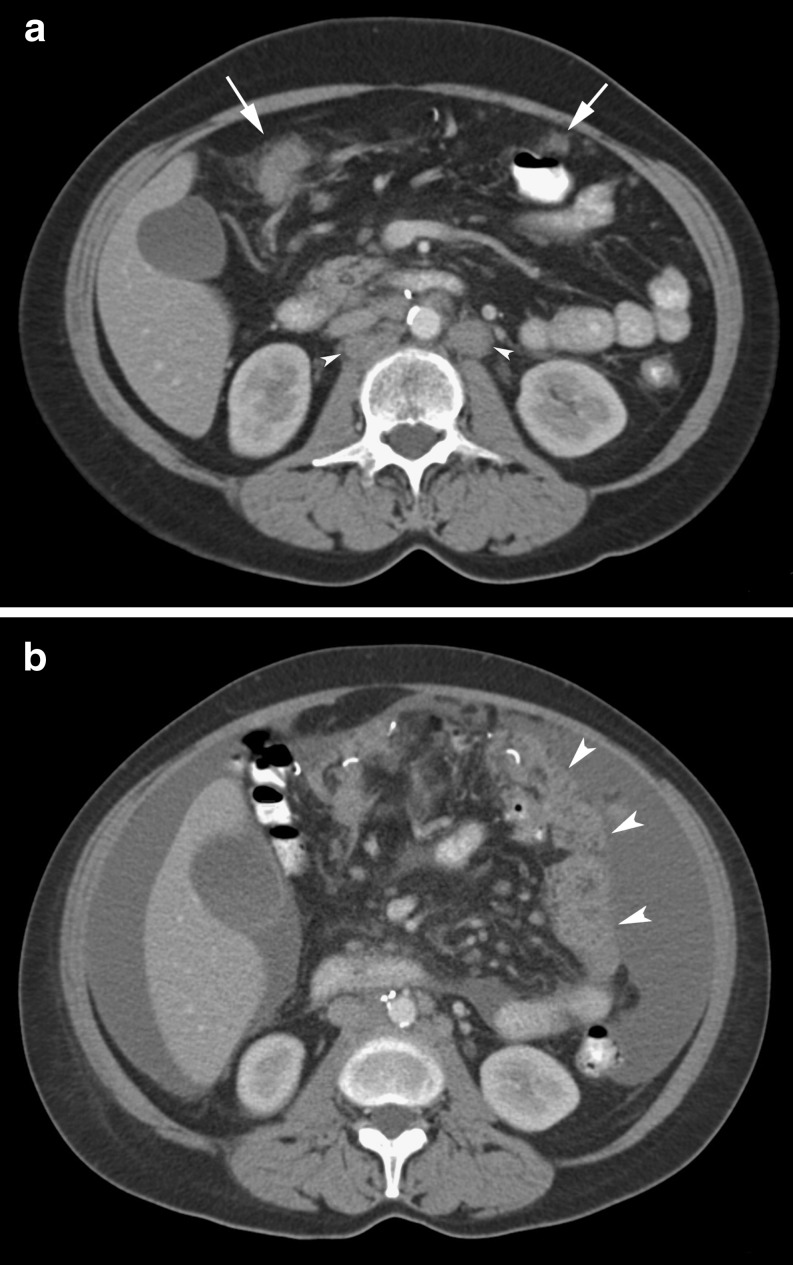

On CT, the normal greater omentum appears as a band of fatty tissue with variable width. The CT appearance of omental pathology is dependent on the extent and duration of disease involvement. Early omental disease manifests as a smudged or permeated appearance of the omental fat (Fig. 3a). Enhancing soft tissue nodules form within the omentum as the disease progresses. An omental cake arises when these nodules coalesce to form a diffusely thickened mass and replace the normal fat (Fig. 3b) [6]. Depending on the cause of the omental cake and the extent of intraperitoneal disease, ascites may be an accompanying feature.

Fig. 3.

(a,b). Ovarian cancer in a 47-year-old woman demonstrating progresssion of omental cake. a Initial CT image shows early infiltration and nodularity of the omentum (arrows) and retroperitoneal adenopathy (arrowheads). b Interval progression of disease with ascites and the mass-like omental cake (arrowheads) in the remaining omentum after a partial omentectomy on a CT scan 3 months later

While 100–150 cc of non-ionic iodinated intravenous contrast material (1.5-2 cc/s) is desirable to increase the intrinsic contrast of the images, it may not be necessary to diagnose the extent of an omental cake, unless knowledge of the extent is important to surgical planning. Frequently, however, intravenous contrast material is administered, mostly to evaluate coexisting liver or other solid organ disease. Oral contrast material is valuable to avoid confusing unopacified bowel loops with omental pathology and to define the extent of the omental findings [7].

The presence of associated intraabdominal and intrahepatic findings, such as hepatic metastases and lymphadenopathy, may be the only clues as to the origin of omental disease if the diagnosis is unknown; the appearance of the omental cake itself is non-specific with respect to the diagnosis [6]. As there are many conditions that can produce an omental cake, the need for a specific diagnosis relies on percutaneous biopsy of the cake if the aetiology is unknown.

Ultrasound (US) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) also have been used to evaluate the greater omentum [8, 9]. US serves an alternative to CT in guiding biopsy of omental cakes [8]. MRI demonstrates omental cakes and other peritoneal implants, but unless a gastrointestinal contrast agent is administered, there is inferior contrast resolution relative to CT [9]. Thus, CT is the mainstay modality to image the greater omentum. Nevertheless, MRI may be utilized in patients with contraindications to CT (contrast sensitivity, pregnancy) or as an adjunct in patients with inconclusive CT findings. Delayed enhancement after gadolinium improves detection of peritoneal metastases [10]. Furthermore, the use of diffusion-weighted MRI is emerging as a potential technique for omental and peritoneal metastases [11].

Malignancy

Metastatic involvement is the most common cause of omental cakes [6]. Along with peritoneal fluid (74%) and peritoneal thickening with enhancement (62%), omental involvement is a frequently encountered finding with peritoneal carcinomatosis on CT [12]. While ovarian carcinoma is the most common cause of omental cakes, colonic, pancreatic, and gastric cancers are other common malignancies that may result in omental metastases [13]. However, virtually any tumour capable of intraperitoneal spread, such as endometrial or bladder cancer, may cause an omental cake (Figs. 4, 5, 6, 7) [13].

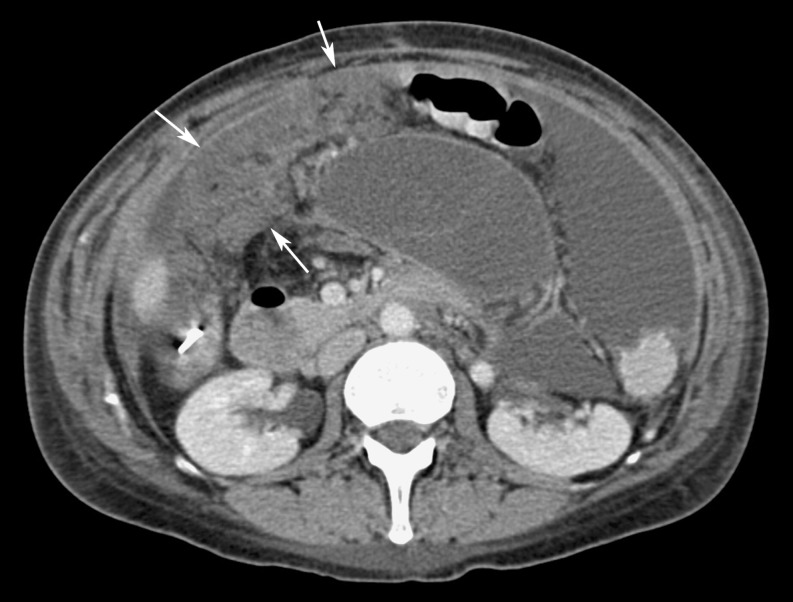

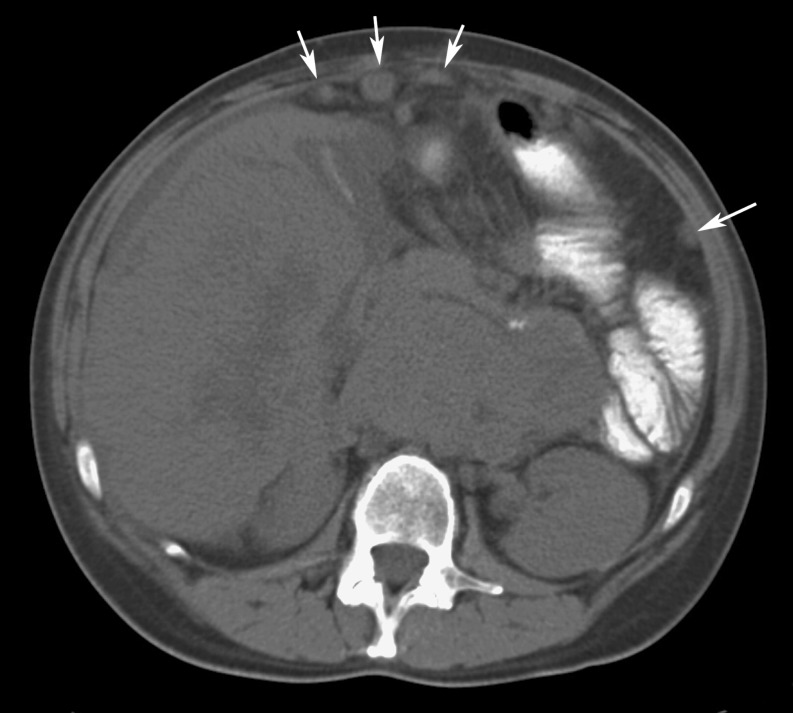

Fig. 4.

Ovarian cancer in a 51-year-old woman. CT image shows extensive omental thickening (arrows) and ascites

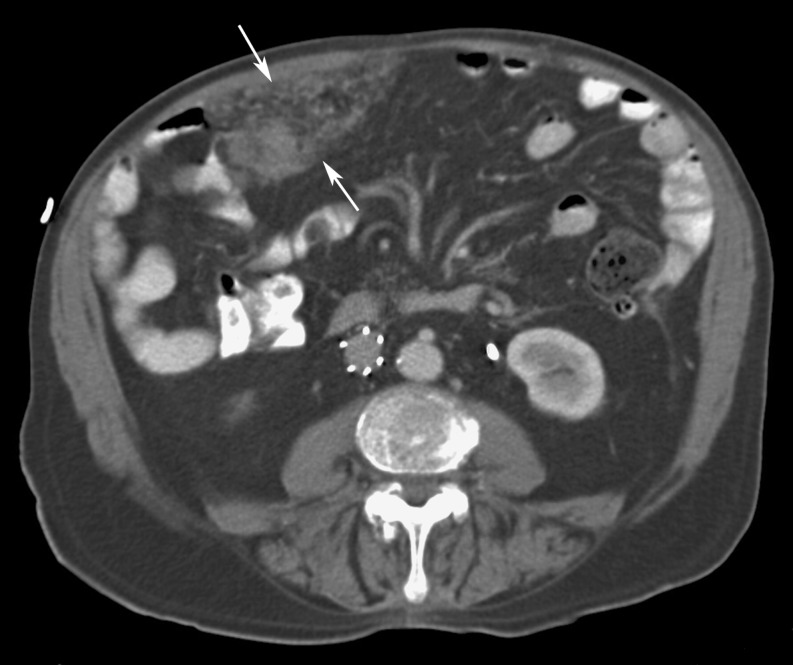

Fig. 5.

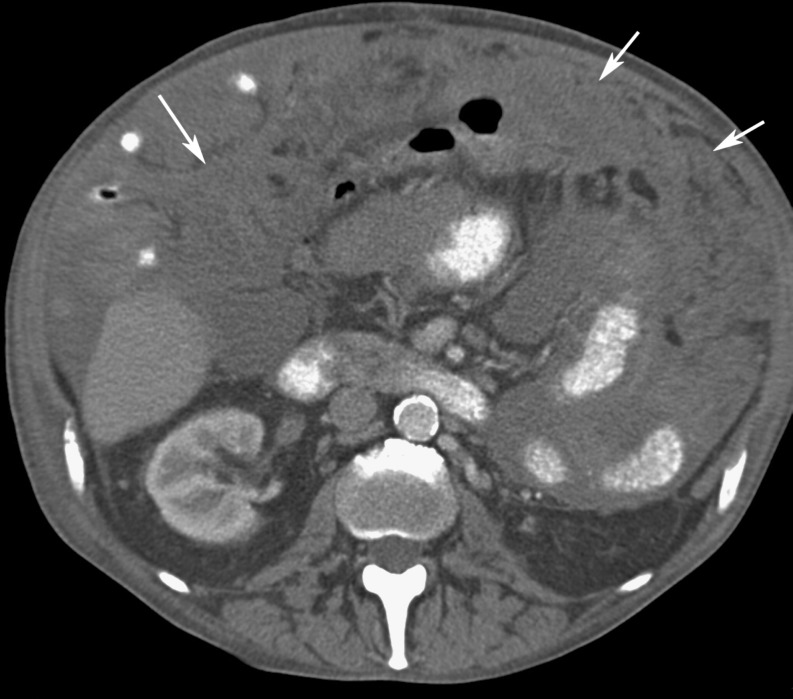

Colon cancer in a 65-year-old man. CT image demonstrates a thick omental cake in the left anterior abdomen (arrows). Peripheral ascites is also present, predominantly on the right side

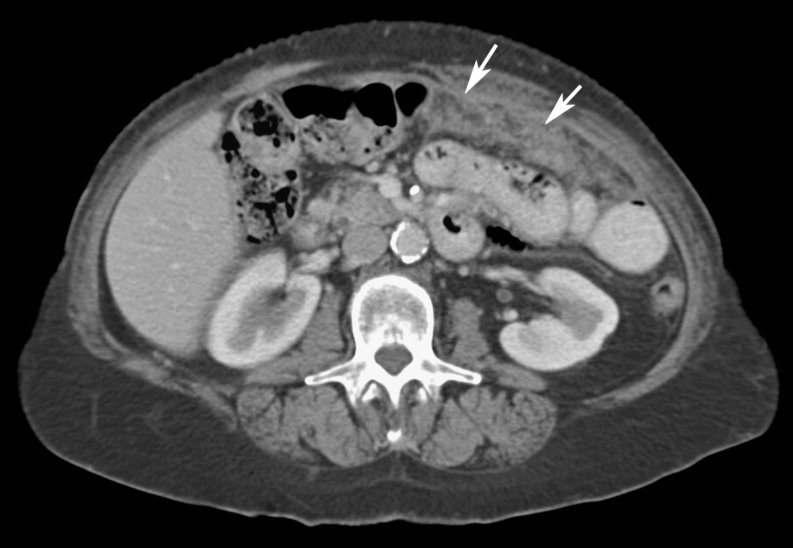

Fig. 6.

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma in a 58-year-old man. CT image shows multiple, ill-defined, soft tissue nodules and masses (arrows) permeating the omental fat. Ascites is also present in the right paracolic gutter

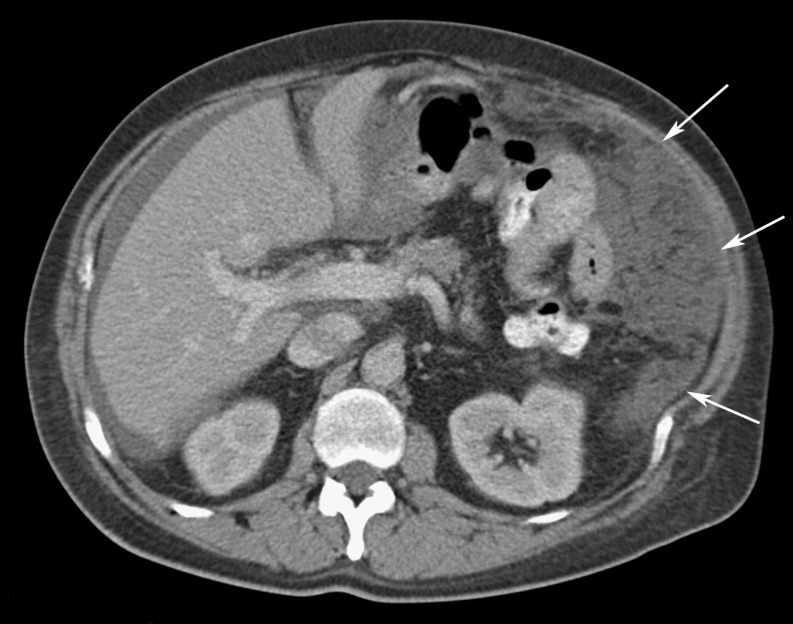

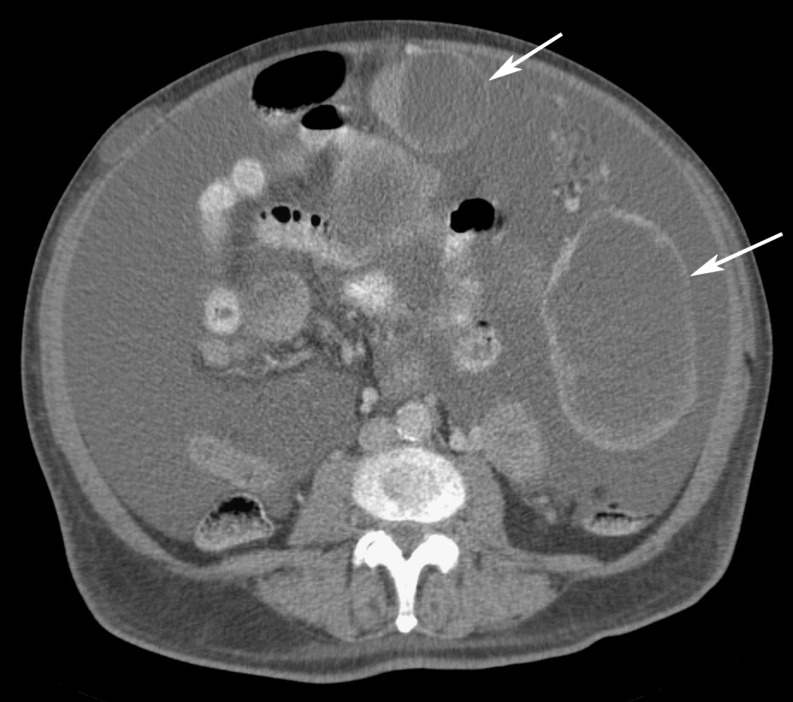

Fig. 7.

Gastric cancer in a 53-year-old woman. CT image demonstrates diffuse linear infiltration, nodularity, and thickening of the omentum (arrows)

Metastases gain access to the greater omentum by any of four principal routes: (1) direct extension of tumour along peritoneal ligaments, (2) intraperitoneal seeding, or via (3) haematogeneous or (4) lymphatic spread of disease [7]. Hepatobiliary malignancies, such as gallbladder carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma, are unusual causes of omental cakes that often are the result of direct extension of tumour along the hepatoduodenal ligament and lesser omentum (Figs. 8, 9, 10) [7]. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma to the omentum may break through the renal capsule, the anterior renal fascia, and the closely apposed posterior parietal peritoneum to spread along the peritoneal surface [14]. Unusual gynaecologic (fallopian tube and endometrium), genitourinary (prostate and urothelium), small bowel, and appendiceal primary cancers also may result in intraperitoneal seeding (Figs. 11, 12, 13, 14). Melanoma, lung, and breast cancers can cause omental cakes, typically by haematogenous spread. Metastases from breast cancer to the stomach may extend directly into the greater omentum (Figs. 15 and 16). Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and, very rarely, Hodgkin’s disease, can develop omental cakes, often with associated diffuse peritoneal and retroperitoneal disease, and ascites from lymphatic spread (Fig. 17) [15].

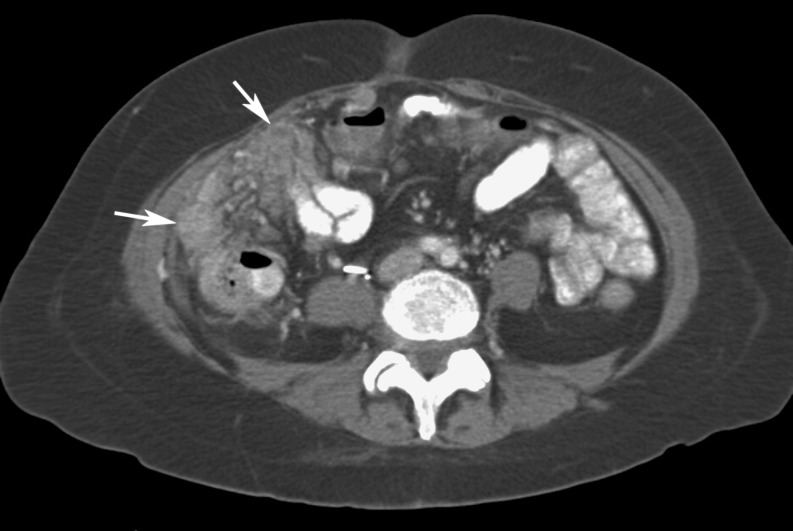

Fig. 8.

Renal cell carcinoma in a 62-year-old man. CT image shows extensive soft tissue nodules present within the omentum (arrows) and the retroperitoneum. A right nephrectomy with surgical clips is seen in the right renal fossa, and ascites is also seen on the right

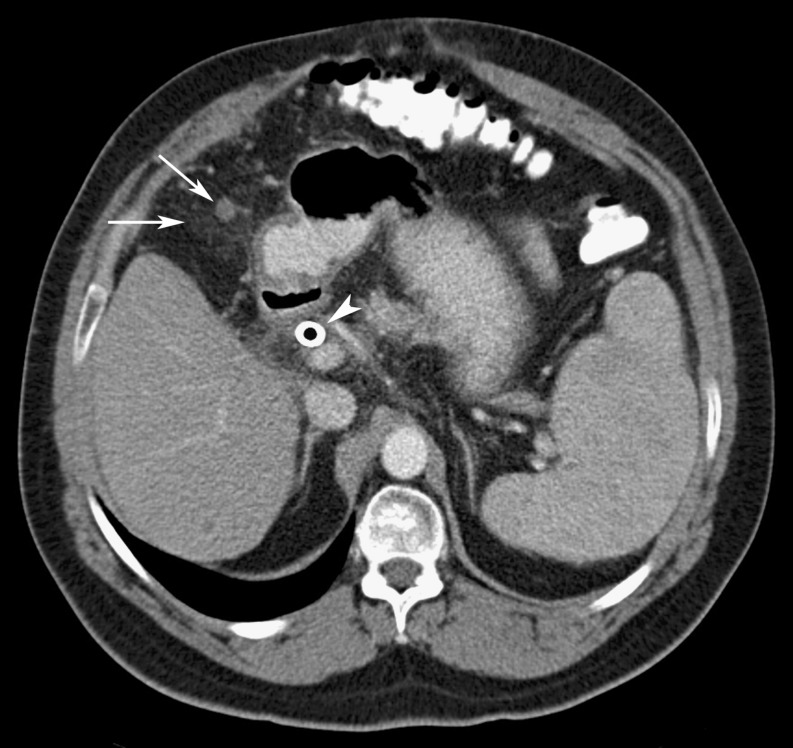

Fig. 9.

Gallbladder carcinoma in a 70-year-old woman. CT image illustrates an omental cake anterior to the liver with infiltration and nodularity of the omental fat (arrows). The tumour also infiltrates the fat of the lesser sac (arrowheads)

Fig. 10.

Cholangiocarcinoma in a 56-year-old man. CT image shows omental involvement with infiltration and nodules (arrows). A biliary stent is also present (arrowhead). Splenomegaly is present

Fig. 11.

Fallopian tube carcinoma in a 45-year-old woman. CT image demonstrates omental involvement (arrows) as infiltration of the fat, nodularity, and coalescence of the nodules form an omental cake

Fig. 12.

Endometrial adenocarcinoma in a 50-year-old woman. CT image shows multiple nodular metastases present within the omentum (arrows) and along the peritoneal surface, the result of intraperitoneal seeding. Hepatomegaly and retroperitoneal metastases are present

Fig. 13.

Prostate cancer in a 75-year-old man. CT image demonstrates omental infiltration (arrows) seen in the absence of ascites or other signs of peritoneal carcinomatosis. Note is made of an inferior vena cava filter

Fig. 14.

Urothelial carcinoma of the bladder in a 59-year-old man. CT image shows extensive diffuse omental involvement (arrows), including the surfaces of the adjacent bowel

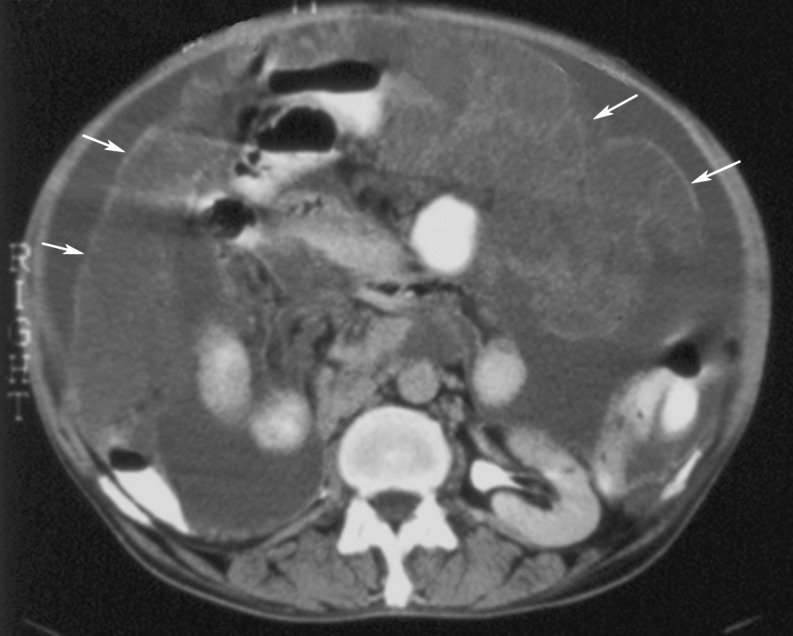

Fig. 15.

Breast cancer in a 45-year-old woman. CT image illustrates peritoneal carcinomatosis with ascites, peritoneal thickening, nodularity (curved arrow), and omental cake (arrowheads). Note also the shrunken liver (arrows) with pseudocirrhosis appearance seen after treatment for liver metastases from breast cancer

Fig. 16.

Non-small cell lung cancer in a 65-year-old man. CT image demonstrates hematogenous metastases seeding the omentum as seen in this omental cake (arrows) adjacent to the spleen and left upper quadrant. There are small bilateral pleural effusions

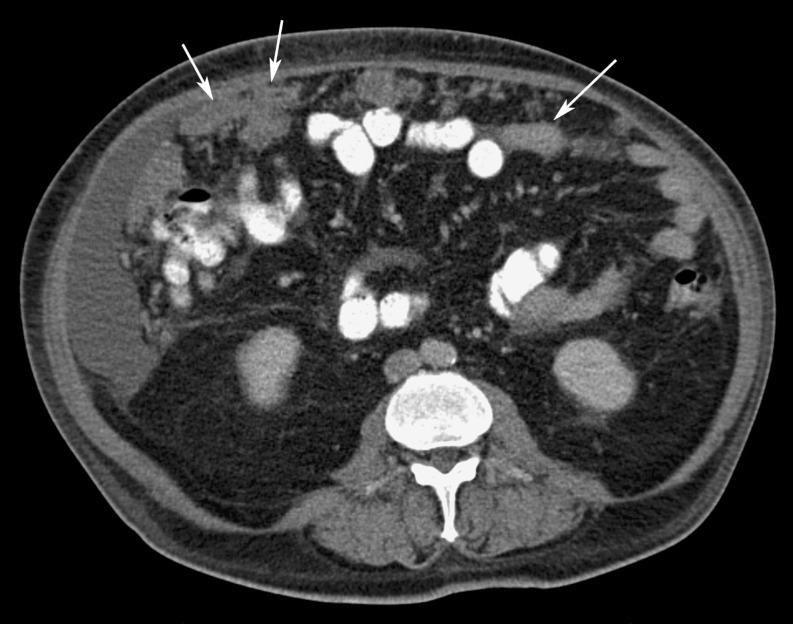

Fig. 17.

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in a 70-year-old man. CT image shows omental cakes (arrowheads) manifested as ill-defined areas of soft tissue anteriorly and peripherally in the abdomen. Multiple renal cysts and calcified gallstones are present, as is ascites

With regards to imaging findings, obvious careful search for the primary malignancy is important to determine the aetiology if the cause of the omental cake is unknown. Metastatic omental involvement occasionally may be heralded by abdominal pain secondary to bowel obstruction or intussusception in cases of gastrointestinal malignancies that metastasise to the small bowel.

Primary malignancies and benign tumours of the peritoneum and omentum are rare. Typically of mesenchymal origin, they include: abdominal mesothelioma, haemangiopericytoma, leiomyoma, leiomyosarcoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST), lipoma, liposarcoma, neurofibroma, fibrosarcoma, and small round cell tumours (Figs. 18, 19, 20, 21) [16, 17]. While these primary lesions are rare, these should be considered in the absence of a known or suspected primary organ-based malignancy [17]. With respect to differentiating imaging findings for benign versus malignant neoplastic cakes, benign lesions usually are well circumscribed, while malignant cakes commonly have indistinct margins and invade surrounding structures [13].

Fig. 18.

Primary mesothelioma in a 52-year-old man. CT image shows a thin omental cake (arrows) in the anterior abdomen with a small amount of ascites in the left paracolic gutter and perihepatic spaces

Fig. 19.

Testicular mesothelioma in a 53-year-old man. CT image shows an omental cake (arrows) in the anterior abdomen

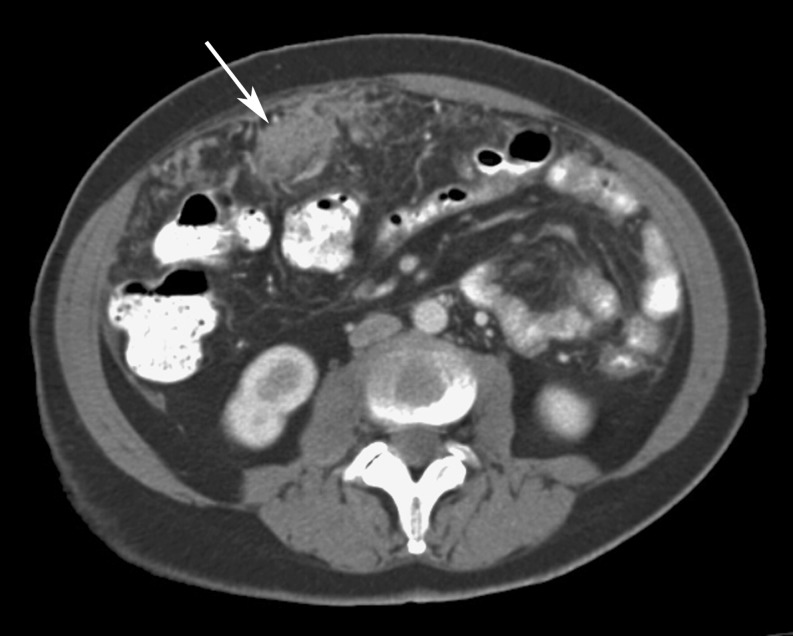

Fig. 20.

Gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST) in a 45-year-old man. CT image shows large, cystic-appearing masses (arrows), some involving the omentum, and a large volume of ascites. The patient had been treated with imatinib mesylate (Gleevec; Novartis, New York, NY) that led to the cystic changes. There is a subcutaneous implant in the right anterior abdominal wall

Fig. 21.

Liposarcoma in a 56-year-old man. CT image demonstrates multiple, clustered, nodular metastases present within the omentum seen in the right abdomen (arrows)

Infection

Infectious diseases are rare causes of omental cakes. Typically, these diseases are the result of haematogenous, lymphatic, or direct spread of infectious organisms into the peritoneum.

Tuberculous peritonitis commonly exhibits omental manifestations, albeit this condition is rare in developed countries. The appearance frequently is similar to peritoneal carcinomatosis. Nevertheless, there are several findings that can help distinguish tuberculous peritonitis from peritoneal carcinomatosis. These include: mesenteric macronodules, irregularity of the infiltrated omentum, an omental line, i.e. a fibrous wall covering the infiltrated omentum, and/or splenomegaly or splenic calcification [18]. The “fibrotic-fixed” form of tuberculous peritonitis produces an omental mass that may mimic metastatic disease (Fig. 22) [19]. Furthermore, the presence of associated enlarged and necrotic mesenteric lymph nodes may be a coexisting finding to narrow the differential diagnosis towards tuberculosis.

Fig. 22.

Tuberculosis in a 51-year-old man. CT image demonstrates ascites and large, low-attenuation omental macronodules covered with a thin omental line (arrows)

Actinomycosis produces an infiltrative solid or cystic omental mass that invades normal anatomic barriers, usually with dense inhomogeneous contrast enhancement [20]. Due to nonspecific clinical findings of actinomycosis, the diagnosis often is not suspected. If there is an omental mass along with clinical signs of leukocytosis and fever without an attributable source, biopsy/aspiration can determine the aetiology (Fig. 23). Attention to the appendix and colon should also be made, as these are the most common intraabdominal organs involved with actinomycosis [20].

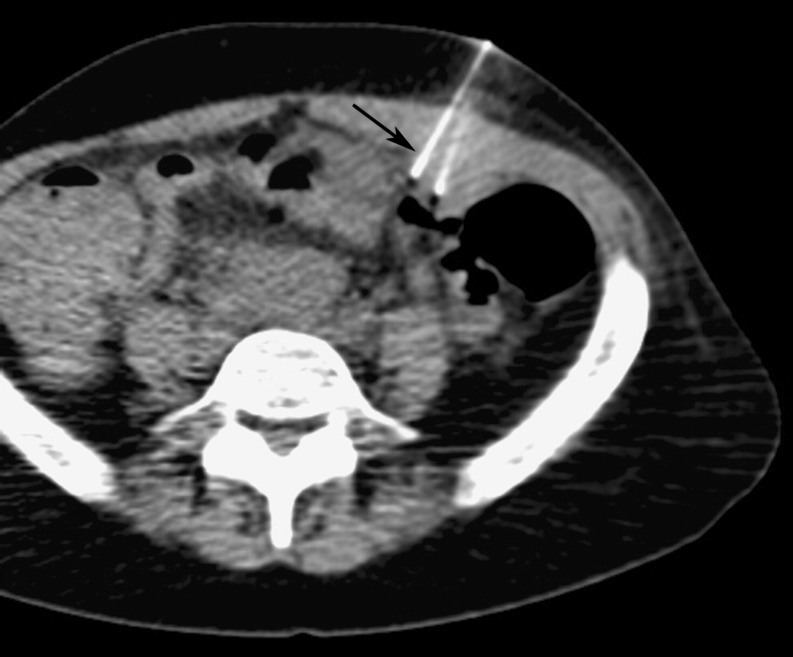

Fig. 23.

41-year-old woman with AIDS, an ovarian mass, and omental cake: CT fluoroscopic-guided percutaneous biopsy of the omental thickening using a 22-g needle revealed Actinomyces israelii, but no evidence of malignancy

Coccidioidomycosis rarely involves the peritoneum and omentum, but also can exhibit an omental cake that mimics peritoneal malignancy (Fig. 24) [21]. In another report [22], CT showed peripherally enhancing deposits in the peritoneal cavity in a patient with systemic coccidioidomycosis. In patients with omental masses and systemic infection geographically in the San Joaquin Valley in California or in Arizona, endemic coccidioidomycosis should be considered. A differentiating feature of coccidioidomycosis is that the gastrointestinal manifestations of coccidioidomycosis are usually preceded by pulmonic, neurological, and musculoskeletal involvement.

Fig. 24.

Coccidioidomycosis in a 43-year-old woman. CT image shows an omental nodule in the right anterior abdomen (arrow) and mesenteric lymph nodes (arrowheads). (Courtesy of Dr. Arash Heidari)

Non-tuberculous mycobacterial infection, histoplasmosis, and omental paragonimiasis all have been reported to cause omental cakes [23, 24]. A unique feature of omental paragonimiasis is the multiple, irregularly shaped, conglomerate calcifications that sometimes occur [24].

Other unusual aetiologies

Various rare benign processes can infiltrate the omentum to such a degree that an omental cake may develop. Extramedullary haematopoiesis, secondary to a number of conditions such as myelofibrosis, is another rare cause of omental caking (Fig. 25). Along with hepatosplenomegaly and multiple masses in various organs in the abdomen, mesenteric and omental masses should raise the suspicion of extramedullary haematopoiesis [23].

Fig. 25.

Myelofibrosis in a 66-year-old man with a history of splenectomy. CT image shows extensive omental infiltration (arrows) with areas of nodularity and ascites. Oral contrast is noted in bowel loops. Biopsy revealed extramedullary hematopoiesis. Benign omental cakes are indistinguishable from those caused by malignancy

Sclerosing omentitis and amyloidosis both may involve the greater omentum and contain scattered calcifications that mimic the appearance of metastatic ovarian cancer or treated peritoneal mesothelioma [25]. Associated calcifications in the subcutaneous tissues, kidneys, and urethra may be additional clues of the presence of amyloidosis [25].

Role of image-guided biopsy

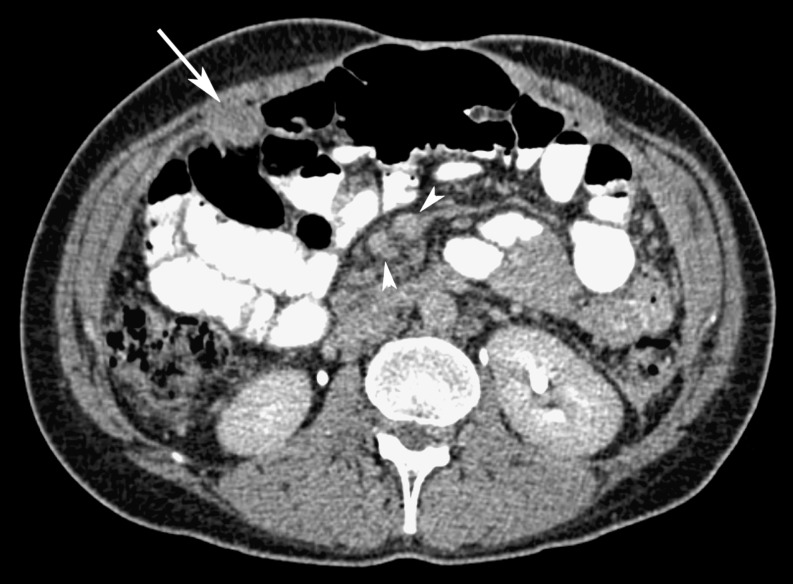

Due to the non-specific CT appearances of omental cakes, biopsy is important to diagnose the etiology if unknown. The superficial location of omental cakes is ideally suited for both image-guided fine-needle (20 g or smaller) and large needle core biopsy (19 g or larger) under either CT or US guidance (Fig. 26).

Fig. 26.

Unknown primary cancer and omental cake in a 65-year-old man. CT fluoroscopic-guided biopsy of the omental cake using a 22-g needle (arrow) revealed adenocarcinoma, with the primary being in the colon

One study reported a sensitivity of 89.5%, specificity of 100%, and accuracy of 92% in the detection of malignancy in 25 percutaneous CT-guided large-needle core biopsies of omental lesions. Furthermore, they were able to obtain a specific diagnosis of the malignancy in 78.9% (15/19) of cases [26]. In another study of 111 percutaneous image-guided peritoneal and omental biopsies, the overall diagnostic rate was 89%, with a sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 86% [26]. Moreover, the authors concluded that a second malignancy was revealed in approximately 10% of patients with a known primary cancer (8/79), such as non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma [27].

The risk of serious complications is minimal with these relatively superficial omental biopsies. It should be noted, however, that although omental involvement can be both conspicuous and relatively straightforward to biopsy, early cases may be subtle and challenging both to visualize and to biopsy.

If there is any question of where the cake-bowel interface is, bowel opacification with oral contrast should be administered to avoid inadvertent needle puncture of the gastrointestinal tract. US also may be used in cases of unexplained ascites with a thickened omentum. One study showed that of 258 patients with nodules in the greater omentum, definitive diagnoses were achieved in 94.57% of cases by US-guided biopsy [8].

Conclusions

While ovarian carcinoma is the prototype omental cake, many malignancies from a wide spectrum of primary sites and organ systems can produce this appearance. Although malignancy is by far the most common aetiology of omental cakes, numerous benign causes exist as well. The non-specific CT appearances of omental cakes make the need for a pathological diagnosis paramount for proper treatment if the primary diagnosis is unknown. The typical omental cake, located superficially within the abdomen, is ideally suited to percutaneous CT or US-guided biopsy for primary diagnosis and staging.

References

- 1.Wilson T (1913) Gelatinous glandular cysts of the ovary, and the so-called pseudomyxoma of the peritoneum. Proc R Soc Med 6 (Obstet Gynaecol Sect):9–42 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Miller Q, Kline AL (2008) Solid Omental Tumours. eMedicine.com http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/193622-overview. Image modified and reprinted with permission from eMedicine.com, 2010

- 3.Sompayrac SW, Mindelzun RE, Silverman PM, Sze R. The greater omentum. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;168:683–687. doi: 10.2214/ajr.168.3.9057515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krist LFG, Kerremans M, Broekhuis-Fluitsma DM, Eestermans IL, Meyer S, Beelen RHJ. Milky spots in the greater omentum are predominant sites of local tumour cell proliferation and accumulation in the peritoneal cavity. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1998;47:205–212. doi: 10.1007/s002620050522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Platell C, Cooper D, Papadimitriou JM, Hall JC. The omentum. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:169–176. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i2.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper C, Jeffrey RB, Silverman PM, Federle MP, Chun GH. Computed tomography of omental pathology. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1986;10:62–66. doi: 10.1097/00004728-198601000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Healy JC, Reznek RH. The peritoneum, mesenteries, and omenta: normal anatomy and pathological processes. Eur Radiol. 1998;8:886–900. doi: 10.1007/s003300050485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Que Y, Tao C, Wang Y, et al. Nodules in the thickened greater omentum: a good indicator of lesions? J Ultrasound Med. 2009;28:745–748. doi: 10.7863/jum.2009.28.6.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chou CK, Liu GC, Su JH, Chen LT, Sheu RS, Jaw TS. MRI demonstration of peritoneal implants. Abdom Imaging. 1994;19:95–101. doi: 10.1007/BF00203480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forstner R. Radiological staging of ovarian cancer: imaging findings and contribution of CT and MRI. Eur Radiol. 2007;17:3223–3235. doi: 10.1007/s00330-007-0736-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whittaker CS, Coady A, Culver L, Rustin G, Padwick M, Padhani AR. Diffusion-weighted MR imaging of female pelvic tumours: a pictorial review. Radiographics. 2009;29:759–774. doi: 10.1148/rg.293085130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walkey MM, Friedman AC, Sohotra P, Radecki PD. CT manifestations of peritoneal carcinomatosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;150:1035–1041. doi: 10.2214/ajr.150.5.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamrick-Turner JE, Chiechi MV, Abbitt PL, Ros PR. Neoplastic and inflammatory processes of the peritoneum, omentum, and mesentery: diagnosis with CT. Radiographics. 1992;12:1051–1068. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.12.6.1439011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tartar VM, Heiken JP, McClennan BL. Renal cell carcinoma presenting with diffuse peritoneal metastases: CT findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1991;15:450–453. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199105000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim YS, Cho OK, Song SY, Lee HS, Rhim HC, Koh BH. Peritoneal lymphomatosis: CT findings. Abdom Imaging. 1998;23:87–90. doi: 10.1007/s002619900292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoo E, Kim JH, Kim MJ, et al. Greater and lesser omenta: normal anatomy and pathologic processes. Radiographics. 2007;27:707–720. doi: 10.1148/rg.273065085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pickhardt PJ, Bhalla S. Primary neoplasms of peritoneal and sub-peritoneal origin: CT findings. Radiographics. 2005;25:983–995. doi: 10.1148/rg.254045140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ha HK, Jung JI, Lee MS, et al. CT differentiation of tuberculous peritonitis and peritoneal carcinomatosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167:743–748. doi: 10.2214/ajr.167.3.8751693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanson RD, Hunter TB. Tuberculous peritonitis: CT appearance. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1985;144:931–932. doi: 10.2214/ajr.144.5.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ha HK, Lee HJ, Kim H, et al. Abdominal actinomycosis: CT findings in 10 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1993;161:791–794. doi: 10.2214/ajr.161.4.8372760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dooley DP, Reddy RK, Smith CE. Coccidioidomycosis presenting as an omental mass. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:802–803. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.4.802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eyer BA, Qayyum A, Westphalen AC, Yeh BM, Joe BN, Coakley FV. Peritoneal coccidioidomycosis: a potential CT mimic of peritoneal malignancy. Abdom Imaging. 2004;29:505–506. doi: 10.1007/s00261-003-0149-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scott WW, Jr, Fishman EK. Extramedullary hematopoiesis mimicking the appearance of carcinomatosis or peritoneal mesothelioma: computed tomography demonstration. Gastrointest Radiol. 1990;15:82–83. doi: 10.1007/BF01888744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jeong WK, Kim Y, Kim YS, et al. Heterotopic paragonimiasis in the omentum. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2002;26:1019–1021. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200211000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coumbaras M, Chopier J, Massiani MA, Antoine M, Boudghene F, Bazot M. Diffuse mesenteric and omental infiltration by amyloidosis with omental calcification mimicking abdominal carcinomatosis. Clin Radiol. 2001;56:674–678. doi: 10.1053/crad.2000.0654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pombo F, Rodriguez E, Martin R, Lago M. CT-guided core-needle biopsy in omental pathology. Acta Radiol. 1997;38:978–981. doi: 10.1080/02841859709172113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Souza FF, Mortelé KJ, Cibas ES, Erturk SM, Silverman SG. Predictive value of percutaneous imaging-guided biopsy of peritoneal and omental masses: results in 111 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:131–136. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]