Abstract

Colonic diverticulitis (CD) is a common entity whose diagnosis is particularly based on computed tomography (CT) examination, which is the imaging technique of choice. However, unusual CT findings of CD may lead to several difficulties and potential pitfalls: due to technical errors in the management of the CT examination, due to the anatomical situation of the diseased colon, in diagnosing unusual complications that may concern the gastrointestinal tract, intra- and retroperitoneal viscera or the abdominal wall, and in differentiating CD from other abdominal inflammatory and infectious conditions or colonic cancer. The aim of this work is to delineate the pitfalls of CT imaging and illustrate misleading CT features in patients with suspected CD.

Keywords: Colonic diverticulitis, CT, Computed tomography

Introduction

Colonic diverticulitis (CD) is a common entity with well-known clinical and radiological findings, especially with regard for CT features. Moreover, computed tomography (CT) is widely accepted as the standard of reference technique for diagnosis of CD [1–3]. However, the diagnosis may be misleading in the case of unusual presentation that may mimic several acute or even chronic abdominal pathological conditions [4]. Knowledge of the potential difficulties is essential for the management of these patients.

The objective of this work is to delineate the pitfalls of CT imaging in patients with suspected CD. We will discuss pitfalls related to technical factors, anatomical factors, CD complications and conditions that can mimic CD.

Technical pitfalls

CT is well suited to the evaluation of CD because it is able to demonstrate the wall of the colon as well as the surrounding pericolic fat. For imaging suspected CD and associated complications, careful attention to technique is necessary.

Timing of CT: The most common reason for CT failure in diagnosing CD is an excessively long interval between antibiotic therapy initiation and CT [5]. CT should be done within 48 h after onset of the symptoms suggesting CD (Fig. 1) [1].

Non-contrast-enhanced CT: This is the first step in CT examination. Performed before any opacification, it may demonstrate free-air perforation and/or severe intestinal occlusion, which are relative contra-indications of digestive opacification [6]. Sometimes it gives additional arguments in favour of the diagnosis, such as an intradiverticular stercolith that may be less visible on a contrast-enhanced phase (Fig. 2) [7].

Colonic opacification: Although colonic opacification is not mandatory for the diagnosis of CD, it helps prevent confusion between collapsed bowel and mural thickening due to inflammation by distending the rectum and colon, and provides better images of the colon wall and pericolic abnormalities [8]. In a few cases, failure to opacify the colonic lumen may hinder the diagnosis of CD. Furthermore, colonic opacification could be diagnostic even without intravenous contrast-enhanced CT, which is of great interest in patients with renal failure or proven allergy to contrast material (Fig. 3) [9]. Some authors use oral contrast material but it should not be advised because of the increased patient preparation time and an often insufficient anterograde colonic opacification [10].

Contrast-enhanced CT: Intravenous contrast material administration is crucial for CT examination [11]. Portal venous phase performed after a 70- to 80-s delay, usually sufficient for arterial visualisation and excellent for venous opacification, is critical for enabling detection of subtle bowel wall abnormalities and vascular complications that otherwise might not be visible (Fig. 4).

Investigation of the entire abdominal cavity: It is mandatory and far more frequently performed now than in the past, thanks to the development of multidetector CT [12]. Failure to comply with this rule carries a risk of missing other diagnoses, such as pylephlebitis, hepatic abscess or even CD somewhere other than in the sigmoid colon.

Multiplanar reformations (MPRs): MPRs are not actually technical pitfalls but insufficiencies of the interpretation methodology. MPRs improve advantageously the assessment of colic and pericolic abnormalities, especially in the case of unusual anatomical location or complications (Fig. 5). They are widely used and recommended in the assessment of acute abdominal conditions [13–15].

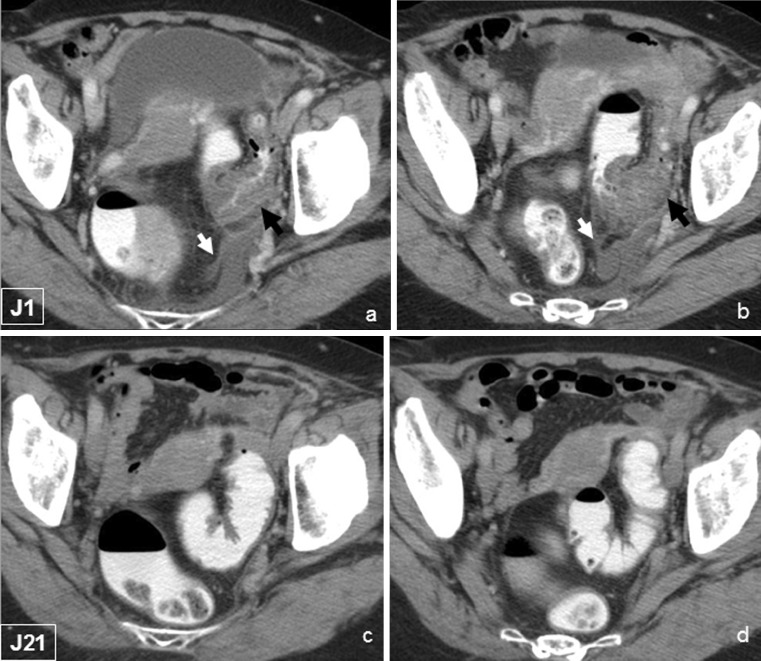

Fig. 1.

Abdominal CT performed within 24 h of symptoms onset demonstrating typical features of sigmoid diverticulitis (a, b), with colonic wall thickening (black arrow) and paracolic inflammation (white arrow). CT performed three weeks later, does not show any suggestion of diverticulitis

Fig. 2.

Stercolith within a diverticulum of the right colon is more clearly identified on non-contrast-enhanced CT (a) (white arrow) than on contrast-enhanced CT (b). The association with mild paracolic inflammation (black arrows) is diagnostic for diverticulitis of the right colon

Fig. 3.

Diverticulitis of the right colon in a 67-year-old woman with a history of renal failure. Only non-contrast-enhanced CT was performed in this patient and the assessment of CT features of diverticulitis (white arrows) was feasible thanks to colonic opacification

Fig. 4.

Abdominal CT in a 63-year-old woman, demonstrating typical features of non-complicated sigmoid diverticulitis (arrowheads). However, left uterine vein thrombosis with vein enlargement and filling defect (white arrows) was detected on portal phase contrast-enhanced CT

Fig. 5.

Diverticulitis of the right colon, with an inflamed diverticulum of the posterior wall of the caecum with fat stranding (arrow). MPR showing adjacent normal appendix (arrowheads) confirmed the diagnosis

Pitfalls related to anatomical factors

Colonic diverticulitis usually occurs in the left side of the colon (90%) but may occur anywhere, except in the rectum [16]. Clinical and imaging features are highly dependent on the location of the inflamed diverticulum within the colon and its anatomical connections with intra- and retroperitoneal spaces.

Diverticulitis of the right colon: The incidence of this form is low in Western countries (1.5%) but is significantly higher (55–70%) in Asian countries. It can present a significant diagnostic challenge, especially with acute appendicitis (Fig. 5) [17, 18]. Actually, the clinical preoperative diagnosis rate of right CD is as low as 5–35% [17, 19]. Performing CT improves significantly the diagnosis accuracy in right CD by showing typical features of an “inflamed diverticulum” (Fig. 6), which is defined as a rounded, paracolic outpouching centred within paracolic inflammation, with a measured soft tissue attenuation [20]. Therefore, CT may prevent the patient from undergoing unnecessary surgery.

Diverticulitis of the transverse colon: This represents a very unusual location of CD with only a few reports in the medical literature [21, 22]. It can masquerade clinically as cholecystitis, appendicitis, hepatic abscess, gastroduodenal perforation, pancreatitis, splenic and renal infection or infarction (Fig. 7).

Diverticulitis of the descending colon: Much more common than the previous location, it is actually similar to sigmoid diverticulitis in its uncomplicated form (Fig. 8). Nevertheless, in its complicated forms and because of its close anatomical connection with the retroperitoneum, it becomes closer to “retroperitoneal” forms [23, 24]. Thus, the differential diagnosis with any kind of retroperitoneal disease may arise, even if it is less likely because left-sided symptoms are often suggestive.

“Retroperitoneal” diverticulitis: Diverticula in the posterior colon wall that are in close contact with the posterior peritoneum may produce retroperitoneal abnormalities [23, 24]. Most of these patients also have intraperitoneal lesions (Fig. 9). Purely retroperitoneal forms are exceedingly rare but raise formidable diagnostic challenges (Fig. 10).

“Ectopic” diverticulitis: This term encompasses CD in a long sigmoid loop lying in the right iliac fossa (Fig. 11) and the few cases of CD within inguinal or parietal herniation [25].

Giant diverticulum: Diverticula may vary in size but usually range from 2 to 3 mm up to 2 cm. Giant diverticulum, defined as a colonic diverticulum measuring 4 cm in size or larger, is a rare complication of this common disease with fewer than 150 cases reported in the literature [26]. Preoperative diagnosis requires a high degree of suspicion and needs to be differentiated from sigmoid volvulus, caecal volvulus, intestinal duplication cyst, pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis, and similar conditions [27]. Awareness of this unusual condition and CT study are the keys to diagnosis.

Synchronous multifocal diverticulitis: Multiplicity is a characteristic of diverticular disease. However, the occurrence of CD in distinct colonic sites at the same time is quite exceptional and may be misdiagnosed if the entire colon is not thoroughly analysed (Fig. 12) [28, 29].

Recurrent multifocal diverticulitis: Recurrence is characteristic of CD, usually occurring more or less at the same location as the previous episode, which is most often the sigmoid colon, justifying, in some reference centres, elective surgery after the second episode of acute CD [30]. Recurrence of CD at a different location in the colon (e.g. right or transverse colon) is quite a rare condition, raising controversy about the most appropriate management of patients following two episodes of acute CD (Fig. 13) [31, 32].

Fig. 6.

Diverticulitis of the right colon with an inflamed anterior diverticulum (white arrow) and thickening of the caecal wall, demonstrating the “arrowhead sign” (black arrow)

Fig. 7.

A 49-year-old patient, presented with acute pain of the upper right quadrant of the abdomen. CT showed a significant fat densification of the upper right quadrant (white arrows) mimicking segmental omental infarction. However, thickening of the right transverse colon associated with a typical “inflamed diverticulum” (black arrow) were diagnostic for diverticulitis of the transverse colon

Fig. 8.

Diverticulitis of the descending colon with an anterior “inflamed diverticulum” (white arrows) associated with intraperitoneal paracolic inflammation

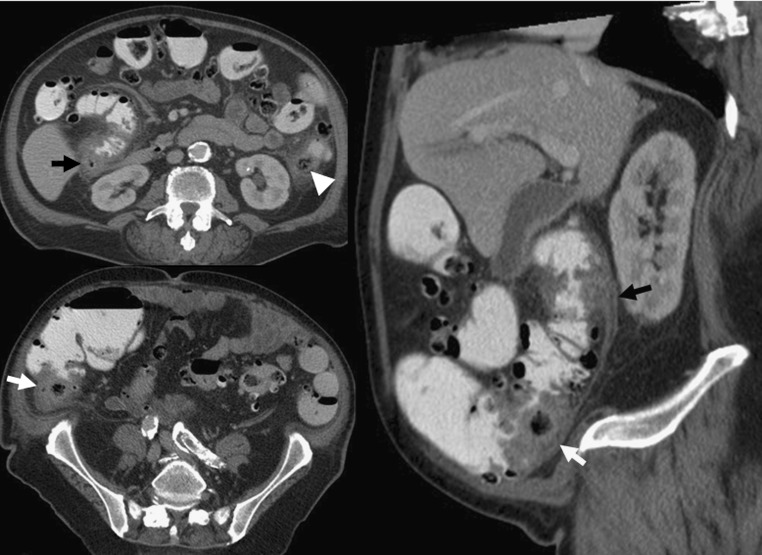

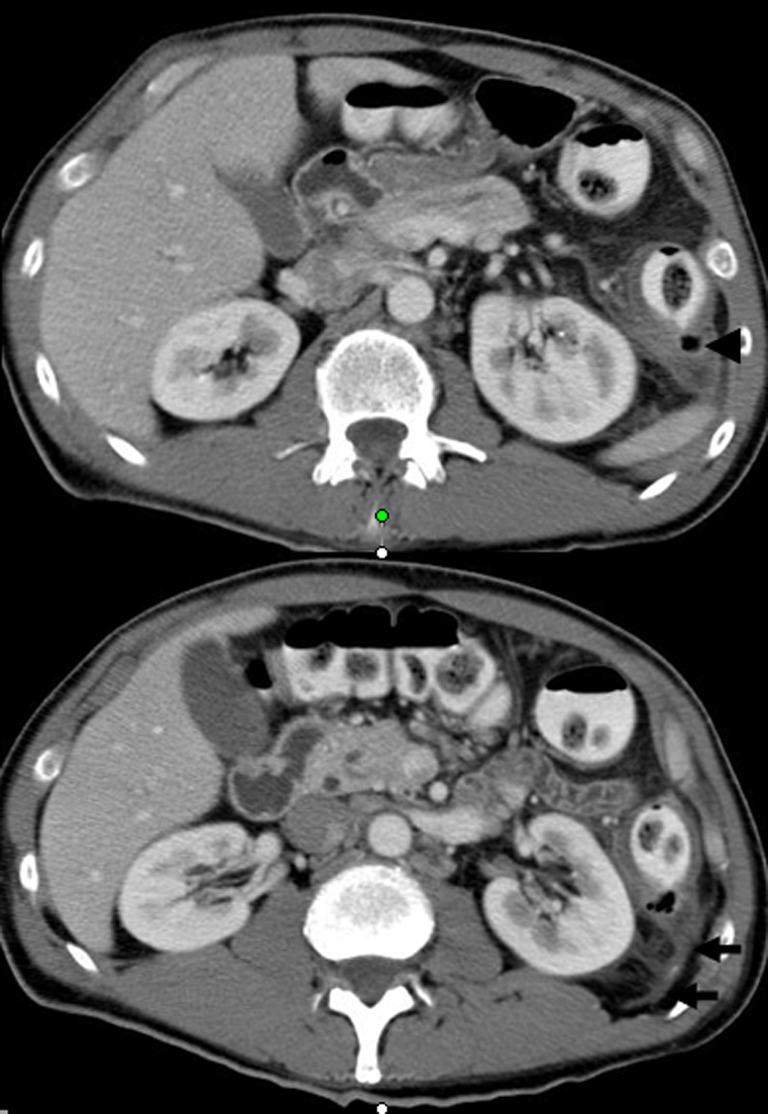

Fig. 9.

Diverticulitis of the descending colon with a posterior “inflamed diverticulum” (arrowhead) associated with retroperitoneal inflammation (arrows)

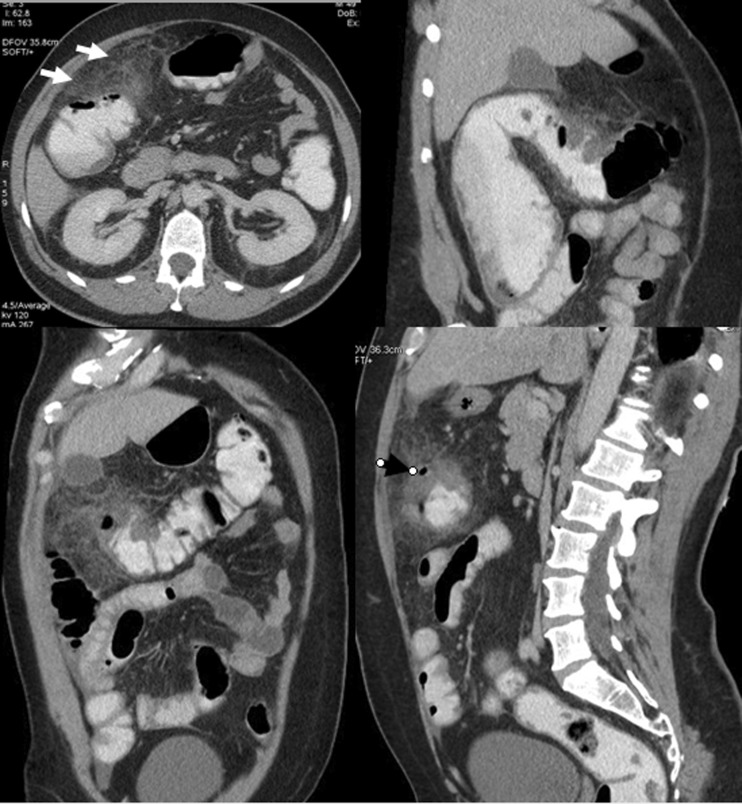

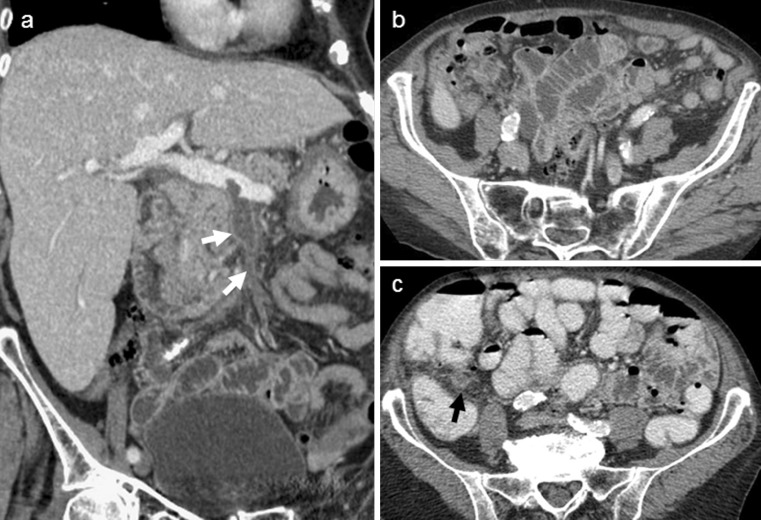

Fig. 10.

Contrast-enhanced abdominal CT performed for acute left-sided abdominal pain in a 56-year-old woman. a Upper sections show perirenal fat stranding (white arrows). Bilateral incidental parapyelic cysts are present. b Lower sections revealed “inflamed diverticulum” within the posterior wall of the descending colon (black arrow) confirming the diagnosis of left colonic diverticulitis with almost purely retroperitoneal involvement

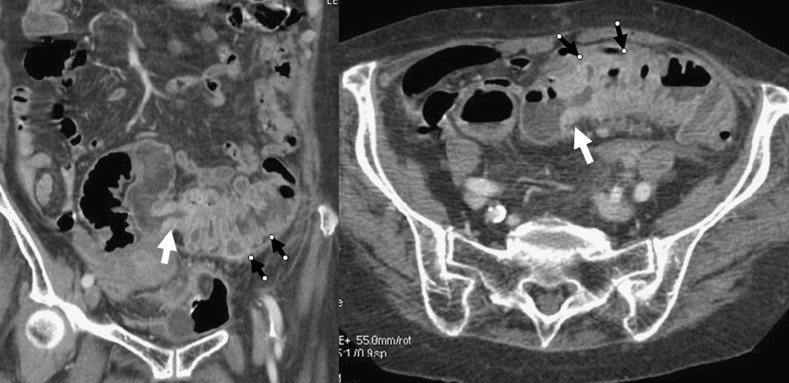

Fig. 11.

Sigmoid diverticulitis in a 29-year-old patient with a sigmoid loop lying in the right iliac fossa masquerading clinically as appendicitis. Inflamed diverticulum (white arrow). Pericolic abscess (black arrow)

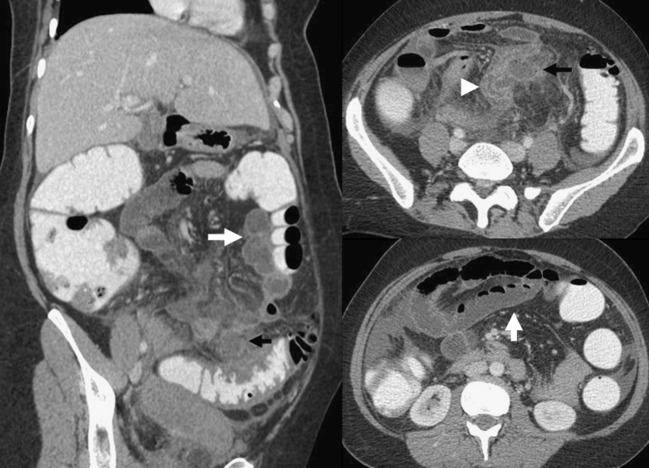

Fig. 12.

Synchronous multifocal diverticulitis with three “inflamed diverticula” visible on the same CT examination: two of them are located in the right ascending colon (white and black arrows) and one in the left descending colon (arrowhead)

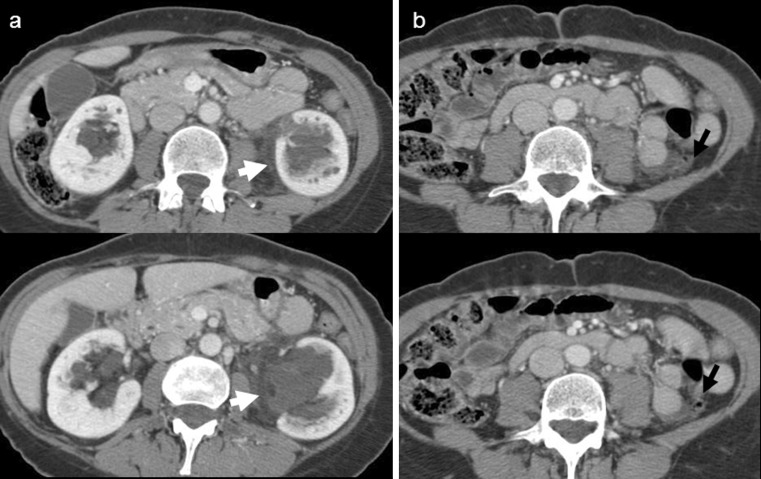

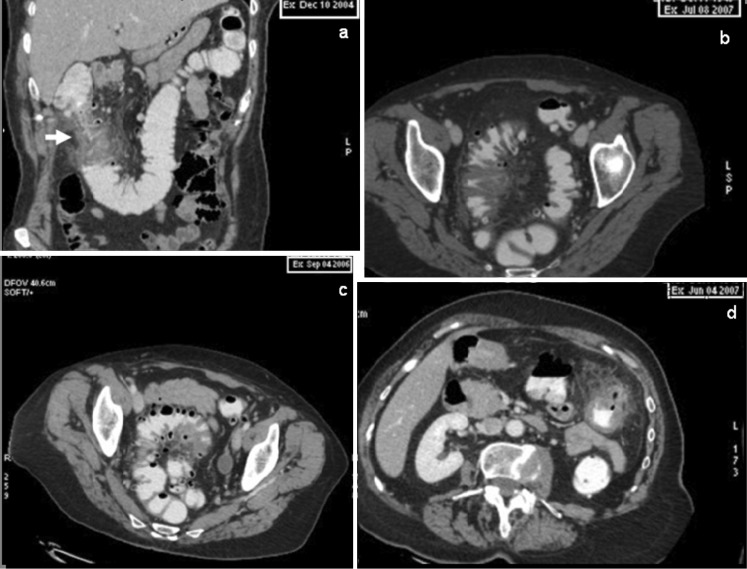

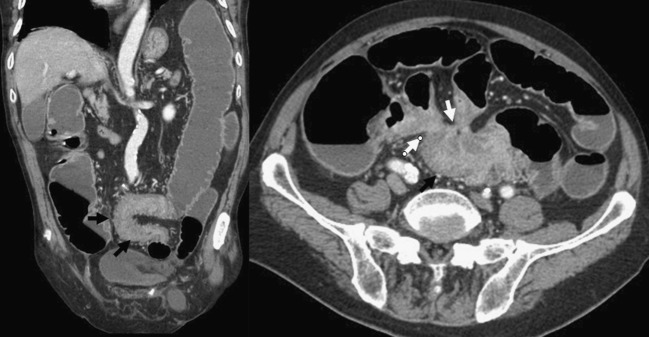

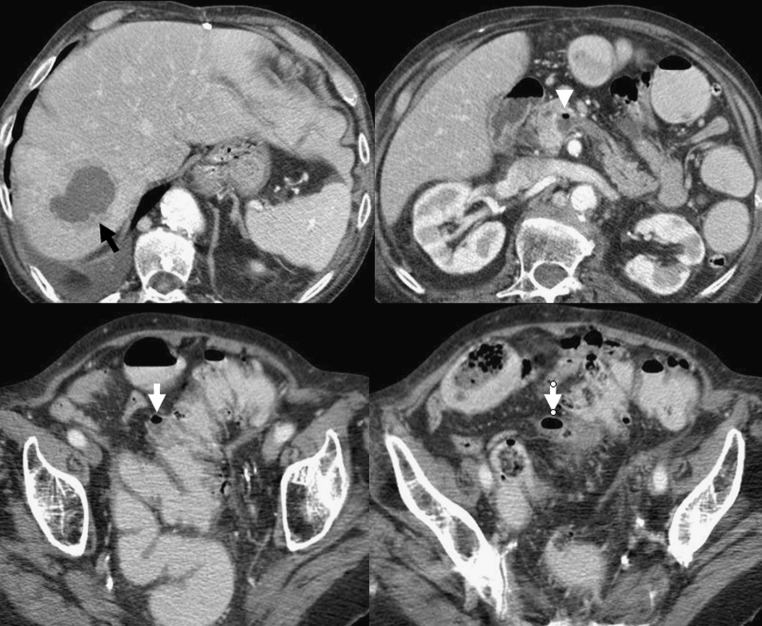

Fig. 13.

a A 61-year-old patient was admitted to hospital in December 2004 with acute abdominal pain. Abdominal CT was diagnostic for diverticulitis of the right transverse colon. The patient was scheduled for surgery and right colonic resection was performed two months after recovery. b The patient was readmitted in September 2006, for similar clinical symptoms. The diagnosis of sigmoid diverticulitis was made on CT. Conservative treatment was performed. c The patient was readmitted in June 2007 for similar clinical symptoms. CT revealed diverticulitis involving the descending colon. Conservative treatment was performed. d The patient was readmitted in July 2007, with a fourth episode of diverticulitis involving the sigmoid colon

Complicated diverticulitis

Colonic diverticulitis is associated with regional inflammation affecting the pericolonic fat, the adjacent mesentery, the retroperitoneum or the pelvis resulting in several complications that could come to the forefront, misleading the primary diagnosis.

Perforation and abscess formation: CT evidence of a pericolic abscess or extraluminal air or contrast material is a well-established risk factor for failure of non-surgical treatment (Figs. 14 and 15) [33]. Even in the case of successful medical treatment, presence of extraluminal air or pericolic abscess indicates a need for prophylactic surgery [33, 34]. Wide windows settings should be used to look for extraluminal air.

Small bowel obstruction: CD is an uncommon cause of small bowel obstruction and may be overlooked as a cause. Small bowel obstruction occurs when diverticular inflammation, most often located at the antimesocolic side of a sigmoid loop, comes into contact with the mesenteric side of the small bowel (Fig. 16). Preoperative CT diagnosis is of first interest to rule out organic small bowel obstruction and prevent unnecessary surgery because inflammation can usually be healed with medical treatment, secondarily relieving the small bowel obstruction [35].

Large bowel obstruction: CD is supposed to be the cause of 10% of large bowel obstructions [11]. The large bowel can be obstructed in two ways: acute inflammation and oedema of the affected segment of bowel, with perhaps a pericolic abscess narrowing the lumen, or chronic inflammation, after recurrent attacks of diverticulitis, can result in fibrous bands across the bowel lumen causing obstruction (Fig. 17). A stricture resulting from CD can be difficult to differentiate from an obstructing neoplasm [36]. CT alone may not distinguish the benign from the malignant causes of luminal narrowing and colonoscopy or sometimes surgery is required where diagnostic uncertainty remains.

Fistulisation: Fistulisation most frequently involves the bladder in men (Fig. 18), which is less frequently involved in women when the uterus is present [11, 37]. Uterine or adnexal or vaginal fistulisation may occur (Fig. 19) [38]. In other cases, fistulisation concerns the abdominal wall or the retroperitoneum and may have several presentations varying with the organ involved (hydronephrosis, psoas abscess, spondylodiscitis, etc.) [24, 39]. The diagnostic difficulty remains, proving the relationship between fistula and CD in the case of mild or absent colonic abnormalities.

Pylephlebitis: Pylephlebitis is the result of the extension of the septic process into the venous drainage of the affected portion of the colon [40]. Spontaneous hyperdensity of the inferior mesenteric vein may be seen on non-contrast-enhanced CT. Narrowing CT windows is required when looking for this hyperdensity which may be unseen with a large window which are more adapted to analysis of peritoneal abnormalities. Luminal filling defect is usually present and can be associated with intraluminal air [41]. Luminal filling defect may be missed on contrast-enhanced CT if the injection delay is not optimal (<70–80 s) for portal vein assessment (Figs. 20 and 21).

Liver abscesses: These are rare complications of CD. Therefore, CD must be considered within the aetiological diagnosis of liver abscesses [42]. A colonic septic source sometimes paucisymptomatic or hidden by an immunosuppressive treatment must be sought, especially when biliary tract disease is ruled out and no other septic origin is identified (Fig. 21).

Fig. 14.

Complicated sigmoid diverticulitis with two paracolic abscesses (white arrows)

Fig. 15.

Diverticular perforation complicating sigmoid diverticulitis in a 35-year-old man. CT demonstrated free gas within the mesosigmoid inflamed fat (white arrows)

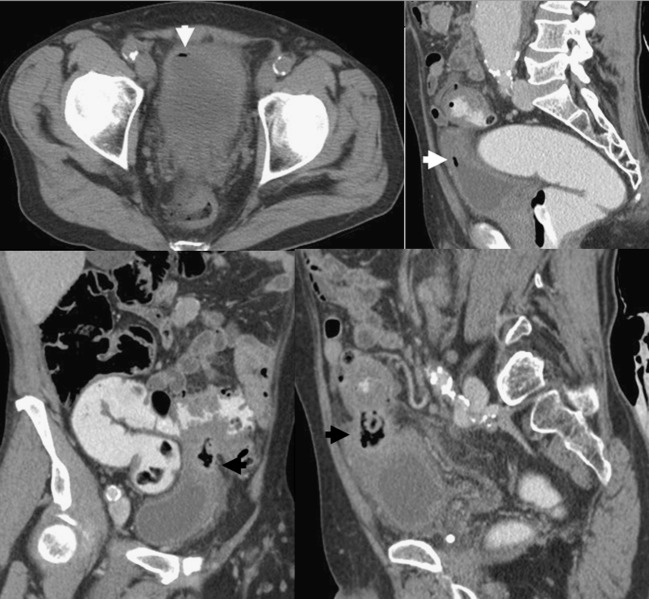

Fig. 16.

Sigmoid diverticulitis with abscess formation (black arrows) associated with thickening of adjacent small bowel wall (white arrowhead) responsible for intestinal obstruction (white arrows)

Fig. 17.

Chronic inflammatory narrowing of the sigmoid colon (black arrows), due to recurrent diverticulitis and responsible for large bowel obstruction and retraction of small bowel loops around an inflammatory mass (white arrows)

Fig. 18.

Contrast-enhanced abdominal CT demonstrating features of sigmoid “inflamed diverticulum” (black arrows) adjacent to a thickened bladder wall associated with free air within the bladder (white arrows), establishing the diagnosis of sigmoid diverticulitis with bladder fistulisation

Fig. 19.

Sigmoid diverticulitis with abscess formation (black arrow) and left adnexal extension of the inflammatory process (white arrow)

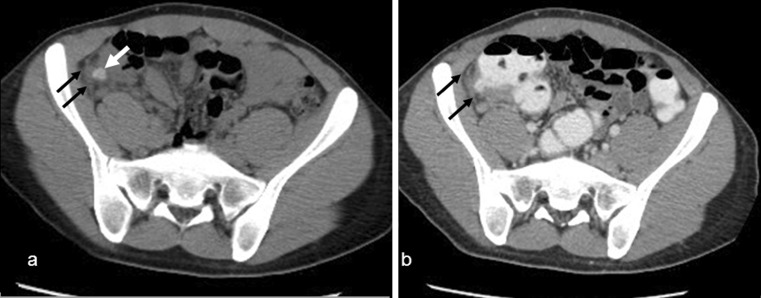

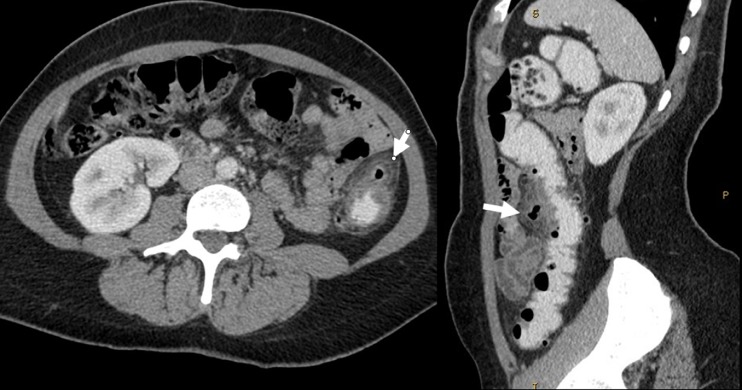

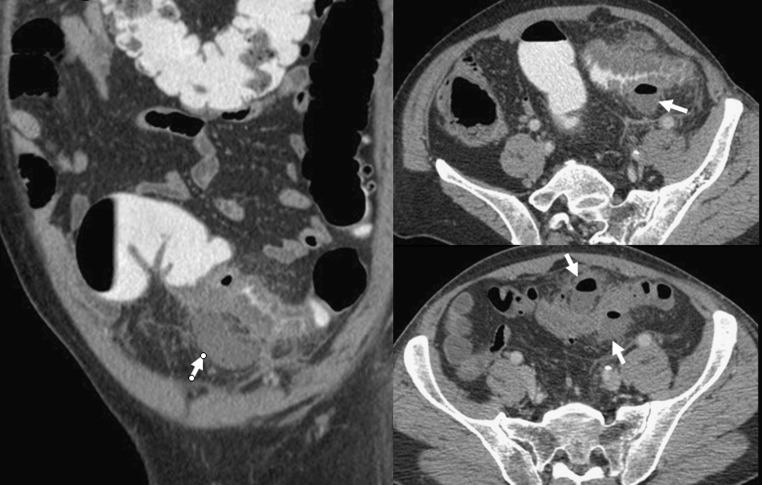

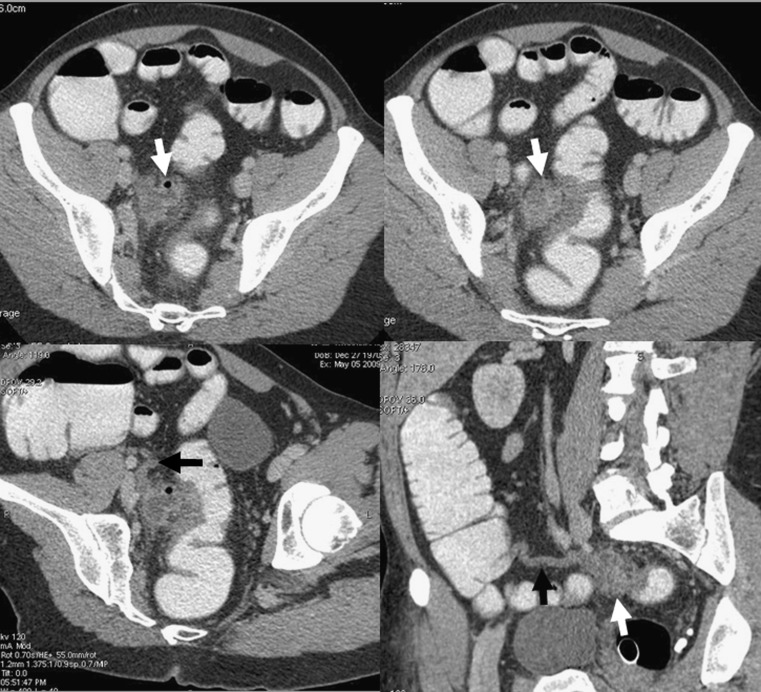

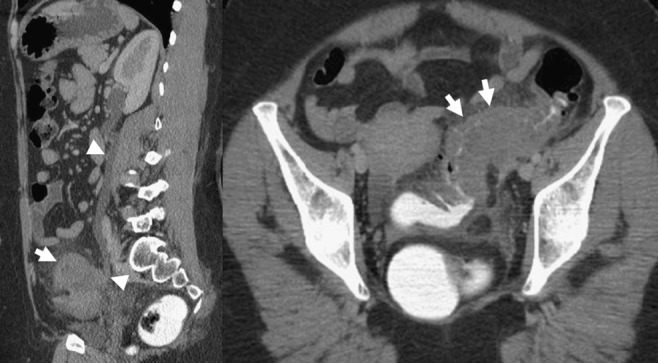

Fig. 20.

A 68-year-old man with abdominal pain and fever. Abdominal contrast-enhanced CT demonstrated a superior mesenteric vein thrombosis (white arrows), with no regional source identified on this first CT scan (a, b). The septic source of this pylephlebitis was diverticulitis of the right colon (black arrow) detected by a second CT examination performed later with colonic opacification (c)

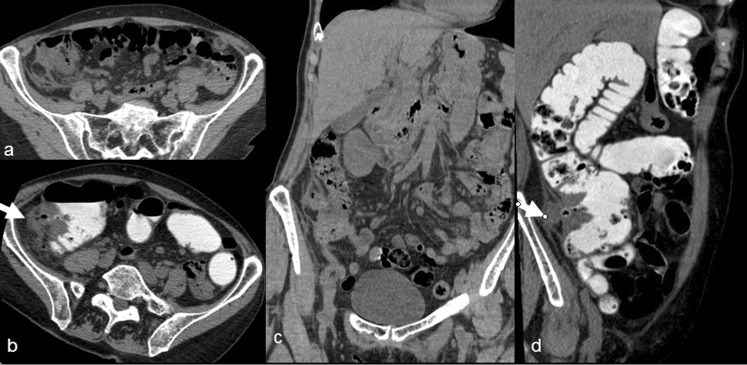

Fig. 21.

Contrast-enhanced CT demonstrating hepatic abscess (black arrow) and pylephlebitis with intravenous free air (white arrowhead) in the superior mesenteric vein. The lower CT sections revealed the septic source which was sigmoid diverticulitis with a small paracolic abscess (white arrows)

Conditions mimicking diverticulitis

The following conditions may be included in the differential diagnosis [43]

Acute appendicitis: As the most frequent abdominal emergency, appendicitis is important to consider systematically because of its extraordinary variability in clinical presentation, until or unless a normal appendix is visualised. Appendicitis and diverticulitis of the right colon share a younger patient population than sigmoid diverticulitis and clinical presentation is usually about the right lower quadrant. However, therapeutic issues diverge with emergency surgery for appendicitis and medical treatment for CD if uncomplicated, which make the differential diagnosis crucial [44]. On CT, differentiating appendicitis and right CD can be very challenging in the case of (1) pericaecal inflammatory stranding in the absence of a visualised appendix, (2) both thickened diverticular caecal wall and appendix with fat stranding or (3) appendicitis in a medial or pelvic location may simulate CD if the distal part of the appendix is in contact with a sigmoid loop (Fig. 22) [45, 46]. Factors that may contribute to a missed diagnosis include a misleading clinical history, paucity of intra-abdominal fat, incomplete contrast material filling of the caecum and small bowel ileus [47].

Appendagitis: Epiploic appendagitis is a rare condition that consists of inflammatory and ischaemic changes related to torsion or spontaneous venous thrombosis of one the epiploic appendices. Clinically, it is most often mistaken for CD. The two conditions are largely indistinguishable on the basis of clinical manifestations alone. However, management and therapeutic issues of these two pathological conditions are different. A misdiagnosis of acute appendagitis as CD may result in unnecessary hospital admission and antibiotic therapy [48]. Because the CT appearance (well-defined oval or round area of fat with an enhancing rim located immediately adjacent to the colon) usually suggests the correct diagnosis non-invasively, most cases can be managed conservatively (Fig. 23). Approximately 7.1% of patients investigated to exclude CD have imaging findings of primary epiploic appendagitis. Although the differential diagnosis is often easy, appendagitis may simulate CD including mild thickening of the colonic wall which is a rare but classically reported finding [49]. On the other hand, inflammation from CD may extend to involve secondarily epiploic appendages, which is a common finding in the case of CD, with the resultant increased difficulty of diagnosis on the basis of CT images [48, 50]. “Secondary” appendagitis should not be misdiagnosed as primary acute appendagitis (Fig. 24). Actually, extraluminal air, a lengthy segment of thickened colonic wall, fistula, abscess formation and bowel obstruction are extremely rare in primary acute appendagitis [48].

Colitis: Most acute inflammatory diseases of the colon, including infectious, non-infectious, and ischaemic disorders, are centred in the colon wall. For these diseases, the degree of colonic wall thickening typically exceeds the degree of associated fat stranding, and not uncommonly; fat stranding may be subtle despite marked mural abnormality [10, 51]. In CD, however, fat stranding is described as “disproportionate” (i.e. stranding more severe than expected for the degree of bowel wall thickening present), which is considered to be a reliable sign for the diagnosis of CD in patients with acute abdominal pain (Fig. 25) [51].

Colon cancer: The most important entity in the differential diagnosis of CD to exclude is colon cancer. Several studies have described the CT features differentiating CD from colon cancer, and have found statistically significant differences in the frequency of different CT findings in patients with colon cancer and those with CD [4, 52–54]. The CT signs that are most suggestive of CD are (1) a stenosis longer than 10 cm, (2) sloping transition zones, (3) colon wall thickness less than 1 cm, (4) fluid in the colonic mesentery, (5) engorgement of mesenteric vessels and (6) absence of enlarged pericolonic lymph nodes (Figs. 26 and 27). In spite of this good correlation, many authors reported a considerable overlap in the CT diagnosis of these two conditions, reaching 50% of cases [52]. By using strict criteria, however, one can make a correct unequivocal diagnosis of CD or cancer in approximately 50% of cases. In those cases, the patients need not undergo further diagnostic evaluation, and further evaluation may be carried out for surgical planning. Besides, the diagnosis may be twice as misleading when ischaemic colitis occurs, which is a classical associated feature in both colonic cancer and CD with mechanical obstruction [55]. Nevertheless, making the diagnosis on the basis of only imaging findings can be very difficult in approximately half of the patients, and colonoscopy at a distance from the acute flare is strongly recommended. Recently, a few studies have reported that functional CT perfusion measurements may facilitate differentiation and discrimination, in combination with morphological criteria, between cancer and CD [56].

Fig. 22.

Paracolic abscess with thickening of the adjacent sigmoid wall was very suggestive of sigmoid diverticulitis (white arrows). Curved MPR revealed a mild thickening of the extremity of the appendix (black arrows), which was pointing to the paracolic abscess. A final diagnosis of a perforated appendicitis was confirmed at surgery

Fig. 23.

Primary appendagitis of the descending colon with a fatty oval-shaped nodule (white arrow) located antero-laterally to the colon associated with mild thickening of the parietal peritoneum (white arrowhead)

Fig. 24.

Non-contrast-enhanced and contrast-enhanced CT revealing typical features of sigmoid diverticulitis associated with secondary appendagitis (white arrows)

Fig. 25.

An 81-year-old man presenting with acute abdominal pain. Abdominal CT demonstrates extensive wall thickening of a diverticular left colon (arrowheads) with “disproportionate” pericolic fat standing (arrows) and no identified “inflamed diverticulum”, suggesting the diagnosis of ischaemic colitis rather than diverticulitis

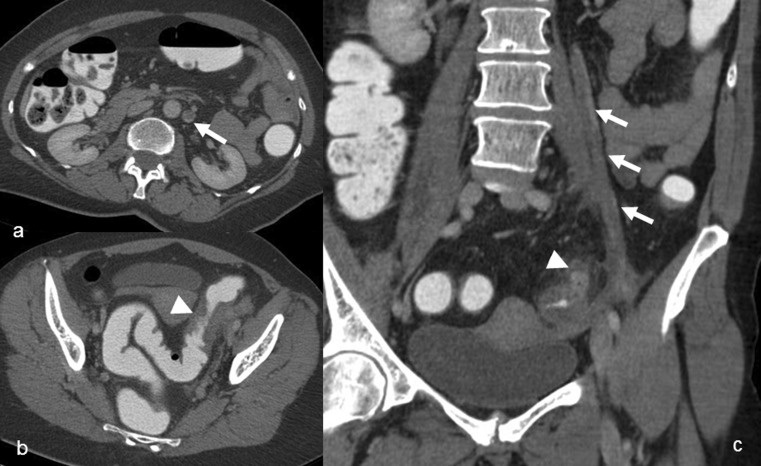

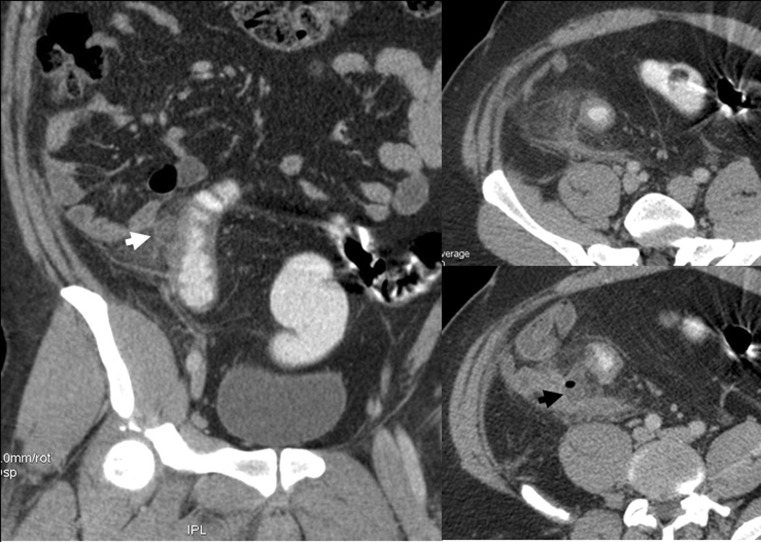

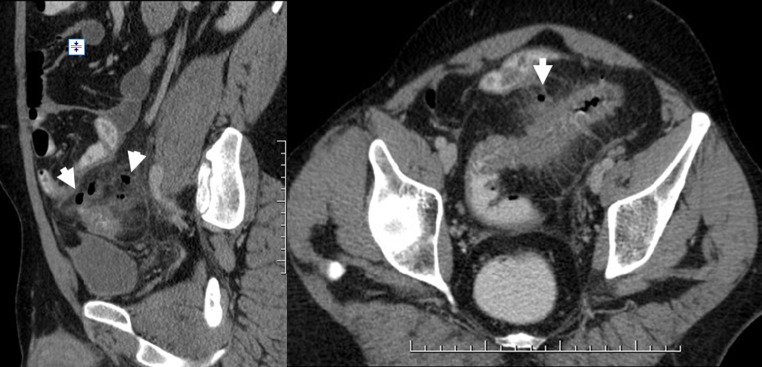

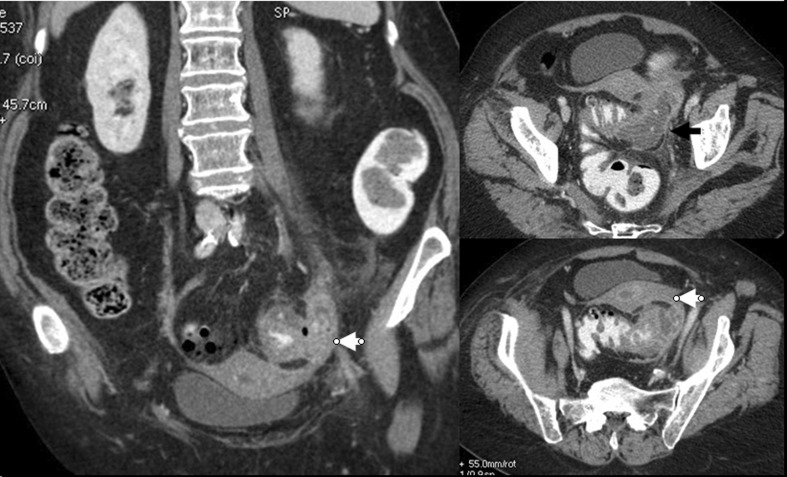

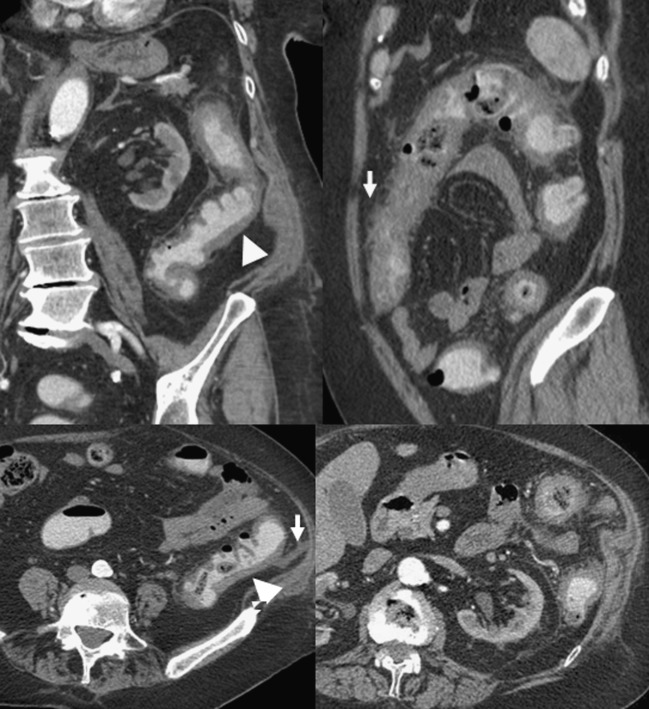

Fig. 26.

Sigmoid diverticulitis mimicking a sigmoid cancer (white arrows) with left ureteral involvement resulting in hydronephrosis (white arrowheads)

Fig. 27.

Abdominal CT in an 80-year-old patient admitted for acute abdominal pain and fever, demonstrating sigmoid thickening suggesting colonic cancer (white arrows) associated with the CT finding of upstream diverticulitis (black arrows). Evidence of the association between these two pathological conditions was surgically proven

Conclusion

Unusual presentations and complications of CD must be kept in mind by the radiologist who must perform CT examination with an optimised technical procedure. When the diagnosis of CD is made, the radiologist has to look for all possible complications that might modify the therapeutic strategy.

References

- 1.Zins M, Bruel JM, Pochet P, Regent D, Loiseau D. Question 1. What is the diagnostic value of the different tests for simple and complicated diverticulitis? What diagnostic strategy should be used? Gastroentérol Clin Biol. 2007;31:3S15–3S19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ambrosetti P, Jenny A, Becker C, Terrier TF, Morel P. Acute left colonic diverticulitis—compared performance of computed tomography and water-soluble contrast enema: prospective evaluation of 420 patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1363–1367. doi: 10.1007/BF02236631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laméris W, Randen A, Bipat S, Bossuyt PMM, Boermeester MA. Graded compression ultrasonography and computed tomography in acute colonic diverticulitis: meta-analysis of test accuracy. Eur Radiol. 2008;18:2498–2511. doi: 10.1007/s00330-008-1018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balthazar EJ, Megibow A, Schinella RA, Gordon R. Limitations in the CT diagnosis of acute diverticulitis: comparison of CT, contrast enema, and pathologic findings in 16 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1990;154:281–285. doi: 10.2214/ajr.154.2.2105015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brengman ML, Otchy DP. Timing of computed tomography in acute diverticulitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:1023–1028. doi: 10.1007/BF02237394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kircher MF, Kihiczak D, Rhea JT, Novelline RA. Safety of colon contrast material in (helical) CT examination of patients with suspected diverticulitis. Emerg Radiol. 2001;8:94–98. doi: 10.1007/PL00011885. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tack D, Bohy P, Perlot I, Maertelaer V, Alkeilani O, Sourtzis S, Gevenois PA. Suspected acute colon diverticulitis: imaging with low-dose unenhanced multi-detector row CT. Radiology. 2005;237:189–196. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2371041432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kircher MF, Rhea JT, Kihiczak D, Novelline RA. Frequency, sensitivity, and specificity of individual signs of diverticulitis on thin-section helical CT with colonic contrast material: experience with 312 cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;178:1313–1318. doi: 10.2214/ajr.178.6.1781313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rao PM, Rhea JT, Novelline RA, Dobbins JM, Lawrason JN, Sacknoff R, Stuk JL. Helical CT with only colonic contrast material for diagnosing diverticulitis: prospective evaluation of 150 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170:1445–1449. doi: 10.2214/ajr.170.6.9609151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thoeni RF, Cello JP. CT imaging of colitis. Radiology. 2006;240:623–638. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2403050818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buckley O, Geoghegan T, O’Riordain DS, Lyburn ID, Torreggiani WC. Computed tomography in the imaging of colonic diverticulitis. Clin Radiol. 2004;59:977–983. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taourel P, Bruel JM. Imaging contribution in gastro-intestinal emergencies. Gastroentérol Clin Biol. 2001;25:B178–B182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paulson EK, Harris JP, Jaffe TA, Haugan PA, Nelson RC. Acute appendicitis: added diagnostic value of coronal reformations from isotropic voxels at multi–detector row CT. Radiology. 2005;235:879–885. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2353041231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim HC, Yang DM, Jin W, Park SJ. Added diagnostic value of multiplanar reformation of multidetector CT data in patients with suspected appendicitis. Radiographics. 2008;28:393–406. doi: 10.1148/rg.282075039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hodel J, Zins M, Desmottes L, Boulay-Coletta I, Jullès MC, Nakache JP, Rodallec M. Location of the transition zone in CT of small-bowel obstruction: added value of multiplanar reformations. Abdom Imaging. 2009;34:35–41. doi: 10.1007/s00261-007-9348-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stollman NH, Raskin JB. Diverticular disease of the colon. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;29:241–252. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199910000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee IK, Jung SE, Gorden L, Lee YS, Jung DY, Oh ST, Kim JG, Jeon HM, Chang SK. The diagnostic criteria for right colonic diverticulitis: prospective evaluation of 100 patients. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:1151–1157. doi: 10.1007/s00384-008-0512-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chia JG, Wilde CC, Ngoi SS, Goh PM, Ong CL. Trends of diverticular disease of the large bowel in a newly developed country. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34:498–501. doi: 10.1007/BF02049937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Law WL, Lo CY, Chu KW. Emergency surgery for colonic diverticulitis: differences between right-sided and left-sided lesions. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2001;16:280–284. doi: 10.1007/s003840100339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rao PM, Rhea JT. Colonic diverticulitis: evaluation of the arrowhead sign and the inflamed diverticulum for CT diagnosis. Radiology. 1998;209:775–779. doi: 10.1148/radiology.209.3.9844673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamamoto M, Okamura T, Tomikawa M, Kido Y, Shiraishi M, Kimura T, Sugimachi K. Perforated diverticulum of the transverse colon. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1567–1569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jasper DR, Weinstock LB, Balfe DM, Heiken J, Lyss CA, Silvermintz SD. Transverse colon diverticulitis: successful nonoperative management in four patients. Report of four cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:955–958. doi: 10.1007/BF02237109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li SY, Jiang JK, Chang YH, Wu TC, Yang WC, Ng YY. Recurrent retroperitoneal abscess due to perforated colonic diverticulitis in a patient with polycystic kidney disease. J Chin Med Assoc. 2009;72:153–155. doi: 10.1016/S1726-4901(09)70042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rothenbuehler JM, Oertli D, Harder F. Extraperitoneal manifestation of perforated diverticulitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1985–1988. doi: 10.1007/BF01297073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenberg J, Arnell TD. Diverticular abscess presenting as an incarcerated inguinal hernia. Am Surg. 2005;71:208–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas S, Peel RL, Evans LE, Haarer KA. Best cases from the AFIP: giant colonic diverticulum. Radiographics. 2006;26:1869–1872. doi: 10.1148/rg.266065019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Praveen BV, Suraparaju L, Jaunoo SS, Tang T, Walsh SR, Ogunbiyi OA (2007) Giant colonic diverticulum: an unusual abdominal lump. 64(2):97–100 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Greenwald M, Nussbaum T. Right colon, sigmoid colon, and transverse colon diverticulitis in the same patient: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:162–166. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0757-7-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krajewski E, Szomstein S, Weiss EG. Synchronous diverticular perforation: report of a case. Am Surg. 2005;71:528–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rotholtz NA, Montero M, Laporte M, Bun M, Lencinas S, Mezzadri N. Patients with less than three episodes of diverticulitis may benefit from elective laparoscopic sigmoidectomy. World J Surg. 2009;33:2444–2447. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0162-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pittet O, Kotzampassakis N, Schmidt S, Denys A, Demartines N, Calmes JM. Recurrent left colonic diverticulitis episodes: more severe than the initial diverticulitis? World J Surg. 2009;33:547–552. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9898-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ambrosetti P. Acute diverticulitis of the left colon: value of the initial CT and timing of elective colectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1318–1320. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0489-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ambrosetti P, Becker C, Terrier F. Colonic diverticulitis: impact of imaging on surgical management: a prospective study of 542 patients. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:1145–1149. doi: 10.1007/s00330-001-1143-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sarma D, Longo WE, NDSG Diagnostic imaging for diverticulitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:1139–1141. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181886ed4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim AY, Bennett GL, Bashist B, Perlman B, Megibow AJ. Small-bowel obstruction associated with sigmoid diverticulitis: CT evaluation in 16 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170:1311–1313. doi: 10.2214/ajr.170.5.9574608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salem TA, Molloy RG, O'Dwyer PJ. Prospective study on the management of patients with complicated diverticular disease. Colorectal Dis. 2006;8:173–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2005.00865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cirocchi R, Mura F, Farinella E, Napolitano V, Milani D, Patrizi MS, Trastulli S, Covarelli P, Sciannameo F. Colovesical fistulae in the sigmoid diverticulitis. G Chir. 2009;30:490–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Panghaal VS, Chernyak V, Patlas M, Rozenblit AM. CT features of adnexal involvement in patients with diverticulitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:963–966. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaul V, Jackson M, Farrugia M. Non-tuberculous iliopsoas abscess due to perforated diverticulitis presenting with intestinal obstruction and a groin mass. Eur Radiol. 2001;11:959–961. doi: 10.1007/s003300000661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bekkhoucha S, Boulay-Colleta I, Turner L, Berrod JL. Pylephlebitis in the course of diverticulitis. J Chir (Paris) 2008;145:284–286. doi: 10.1016/s0021-7697(08)73761-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sywak M, Romano C, Raber E, Pasieka JL. Septic thrombophlebitis of the inferior mesenteric vein from sigmoid diverticulitis. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196:326–327. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(02)01767-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burgard G, Cuilleron M, Cuilleret J. An unusual complication of perforated sigmoid diverticulitis: gas in the portal vein with miliary liver abscesses. J Chir (Paris) 1993;130:237–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rao PM. CT of diverticulitis and alternative conditions. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 1999;20:86–93. doi: 10.1016/S0887-2171(99)90040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rao PM, Rhea JT, Novelline RA. Helical CT of appendicitis and diverticulitis. Radiol Clin North Am. 1999;37:895–910. doi: 10.1016/S0033-8389(05)70137-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lane MJ, Mindelzun RE. Appendicitis and its mimickers. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 1999;20:77–85. doi: 10.1016/S0887-2171(99)90039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karam AR, Birjawi GA, Sidani CA, Haddad MC. Alternative diagnoses of acute appendicitis on helical CT with intravenous and rectal contrast. Clin Imaging. 2007;31:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2006.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Levine CD, Aizenstein O, Lehavi O, Blachar A. Why we miss the diagnosis of appendicitis on abdominal CT: evaluation of imaging features of appendicitis incorrectly diagnosed on CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:855–859. doi: 10.2214/ajr.184.3.01840855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Singh AK, Gervais DA, Hahn PF, Sagar P, Mueller PR, Novelline RA. Acute epiploic appendagitis and its mimics. Radiographics. 2005;25:1521–1534. doi: 10.1148/rg.256055030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singh AK, Gervais DA, Hahn PF, Rhea J, Mueller PR. CT appearance of acute appendagitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:1303–1307. doi: 10.2214/ajr.183.5.1831303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jalaguier A, Zins M, Rodallec M, Nakache JP, Boulay-Coletta I, Jullès MC. Accuracy of multidetector computed tomography in differentiating primary epiploic appendagitis from left acute colonic diverticulitis associated with secondary epiploic appendagitis. Emerg Radiol. 2010;17:51–56. doi: 10.1007/s10140-009-0822-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pereira JM, Sirlin CB, Pinto PS, Jeffrey RB, Stella DL, Casola G. Disproportionate fat stranding: a helpful CT sign in patients with acute abdominal pain. Radiographics. 2004;24:703–715. doi: 10.1148/rg.243035084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chintapalli KN, Chopra S, Ghiatas AA, Esola CC, Fields SF, Dodd GD., 3rd Diverticulitis versus colon cancer: differentiation with helical CT findings. Radiology. 1999;210:429–435. doi: 10.1148/radiology.210.2.r99fe48429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chintapalli KN, Esola CC, Chopra S, Ghiatas AA, Dodd GD., 3rd Pericolic mesenteric lymph nodes: an aid in distinguishing diverticulitis from cancer of the colon. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169:1253–1255. doi: 10.2214/ajr.169.5.9353437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Padidar AM, Jeffrey RB, Jr, Mindelzun RE, Dolph JF. Differentiating sigmoid diverticulitis from carcinoma on CT scans: mesenteric inflammation suggests diverticulitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;163:81–83. doi: 10.2214/ajr.163.1.8010253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ko GY, Ha HK, Lee HJ, Jeong YK, Kim PN, Lee MG, Kim HR, Yang SK, Auh YH. Usefulness of CT in patients with ischemic colitis proximal to colonic cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;168:951–956. doi: 10.2214/ajr.168.4.9124147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goh V, Halligan S, Taylor SA, Burling D, Bassett P, Bartram CI. Differentiation between diverticulitis and colorectal cancer: quantitative CT perfusion measurements versus morphologic criteria—initial experience. Radiology. 2007;242:456–462. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2422051670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]