Abstract

There are numerous pancreatic and peripancreatic conditions that can mimic pancreatic neoplasms. Many of these can be confidently diagnosed on computed tomography (CT), while others will require further imaging. Knowledge of these tumour mimics is important to avoid misclassification of benign conditions as malignant and to avoid unnecessary surgery. Mimics can be grouped as parenchymal, vascular, biliary and peripancreatic. These are discussed and illustrated in this review.

Keywords: Pancreatic neoplasm, Computed tomography, CT, Tumour mimics

Parenchymal tumour mimics

Pancreatitis

Alcohol and intraductal biliary calculi are the commonest causes of pancreatitis, although a variety of other aetiologies—including autoimmune, hereditary, infections and drugs—are also implicated [1]. Acute pancreatitis is a biochemical diagnosis and imaging is reserved to evaluate for sequelae such as necrosis and vascular complications. Diffuse pancreatitis is rarely a diagnostic challenge. However, focal pancreatitis may mimic pancreatic neoplasms.

Acute pancreatitis is seen as reduced attenuation with associated peripancreatic inflammatory changes while the fibrosis of chronic pancreatitis may appear as mass lesions. Unfortunately, the imaging findings of acute and chronic pancreatitis overlap with those of pancreatic carcinomas. Both conditions may produce focal pancreatic enlargement, hypoenhancing lesions with mass effect (Fig. 1), dilatation of the pancreatic and common bile ducts, duct strictures and increased density in the peripancreatic fat [1–3]. Further complicating matters are the increased incidence of pancreatic carcinoma in patients with chronic pancreatitis [4].

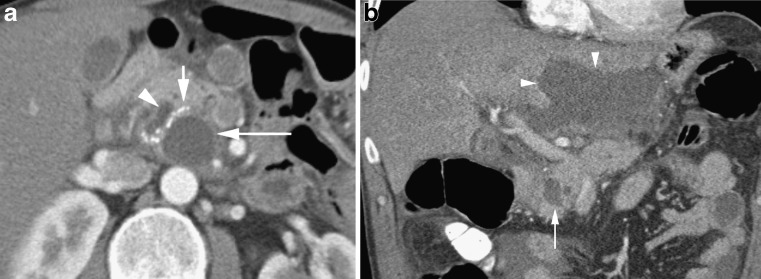

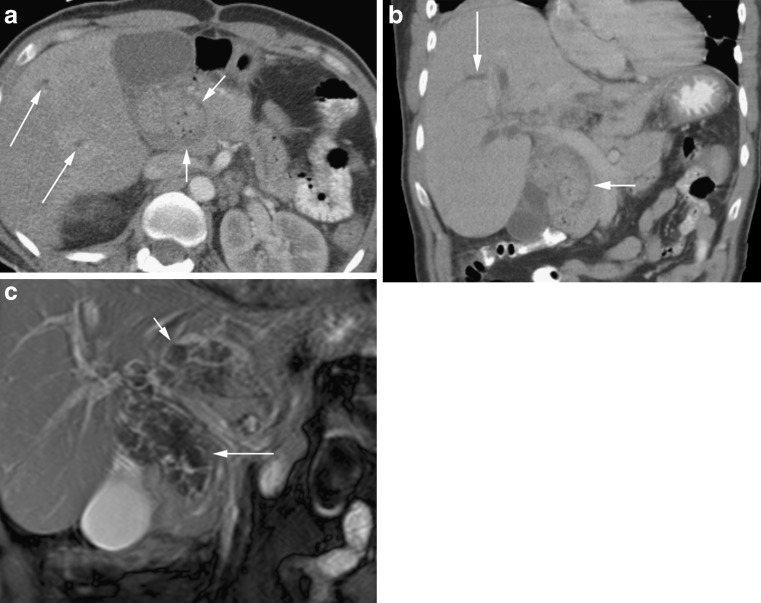

Fig. 1.

Focal pancreatitis as ill-defined low density in the pancreatic head (long arrow). Compare with normal density pancreatic tail (short arrow)

A variant of focal pancreatitis is a rare condition known as groove pancreatitis, which is isolated to the head of the pancreas in the ‘groove’ between the duodenum and common bile duct. It is most frequently induced by alcohol [5] and the condition can prove diagnostically challenging as it frequently presents as a hypoenhancing mass lesion. Fibrosis is prominent and cystic change may occur within the adjacent thickened duodenal wall with associated duodenal stenosis [6]. Because of the fibrosis, the common bile duct and main pancreatic duct may become stenosed with subsequent upstream dilatation. Identification of cysts in the duodenal wall and the presence of Brunners gland hyperplasia [6, 7] may suggest the diagnosis, but unfortunately there is considerable overlap with ductal adenocarcinomas and therefore histological sampling is often required [8].

Pseudocyst

A pseudocyst is defined as “a collection of pancreatic juice enclosed by a wall of fibrous or granulation tissue, which arises as a consequence of acute pancreatitis, pancreatic trauma or chronic pancreatitis” [9]. Pseudocysts are the most frequent pancreatic cystic lesion [10], complicating up to 55% of cases of acute pancreatitis, and may be intrapancreatic or extrapancreatic, solitary or multiple and with a wide variation in size. Pseudocysts are most frequently unilocular with a smooth regular wall (Fig. 2). A number of imaging features have been identified to help differentiate pseudocysts from cystic pancreatic neoplasms (Table 1). A lobulated shape, wall thickness less than 1 mm and smooth internal surface have been identified as benign features, while a round, oval or tubular shape is suspicious for malignancy along with a thick wall with irregular inner margin [11]. There was no statistical difference with location within the pancreas, cyst density or cyst size [11]. A large surgical review of 220 patients identified three features as suspicious for malignancy: (1) presence of a solid component, (2) peripheral calcification and (3) dilatation of the main pancreatic duct, with a combination of these features being more concerning than any one feature alone [12]. However, two or more of these features have a sensitivity of only 34% and specificity of 97%. Indeterminate cases should be referred for endoscopic ultrasound evaluation with aspiration of cysts for biochemical and cytological evaluation, which has been proved to be accurate at differentiating cyst types [13].

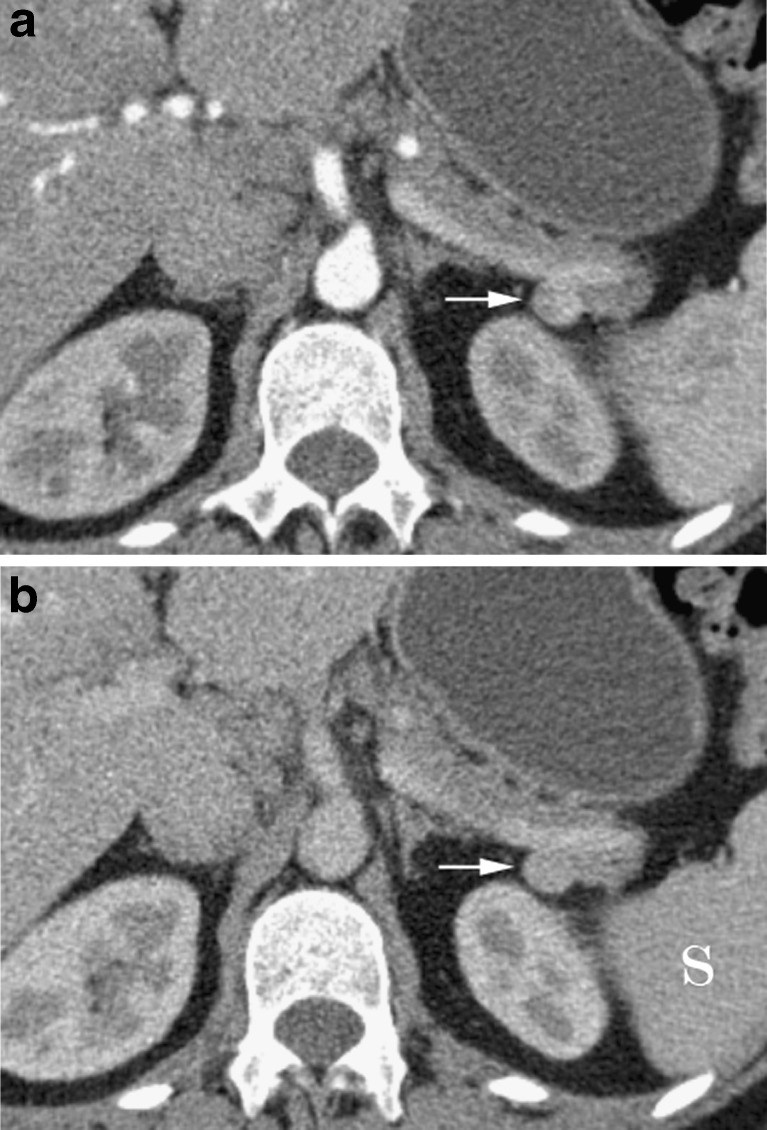

Fig. 2.

a Arterial phase CT in a 45-year-old male alcoholic with an intrapancreatic pseudocyst (long arrow). Note calcifications (short arrow) within the pancreatic parenchyma (not the cyst) and prominent pancreatic duct (arrowhead) from atrophy. b Small intrapancreatic pseudocyst (long arrow) with a large subhepatic pseudocyst (arrowheads) in a 50-year-old man with a history of pancreatitis

Table 1.

| Malignant features | Round, oval or tubular morphology |

| Thick wall | |

| Irregular inner margin | |

| Solid component | |

| Peripheral calcification | |

| Dilated main pancreatic duct | |

| Benign features | Lobulated morphology |

| Wall thickness less than 1 mm | |

| Smooth internal surface |

Cysts

Multiple systemic diseases are associated with pancreatic cysts, with von Hippel-Lindau (Fig. 3), cystic fibrosis and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease being the most frequently encountered. Small cysts may also be the sequelae of pancreatitis, or be true congenital cysts. In a study with 1,444 patients Zhang et al. [14] found pancreatic cysts in 19.6% of patients with an increasing incidence with age. Most were small measuring less than 10 mm, with just over half being solitary and most being simple. Malignant cysts were only seen in 5.7% of all patients with cysts and 26.5% of patients had pancreatitis.

Fig. 3.

Multiple small pancreatic cysts in a 48-year-old with Von Hippel–Lindau

Often pancreatic cysts are approached in a rather aggressive way to avoid missing a cystic neoplasm. However, simple cysts measuring less than 2 cm in patients without a history of pancreatitis or systemic cystic disorder may slowly grow over time, but are rarely associated with morbidity or mortality [15]. Moreover, the presence of a pancreatic cyst measuring 5 mm or greater was an independent risk factor for future development of a pancreatic cancer [16].

Fat infiltration

Fat infiltration and replacement of the pancreas may be idiopathic, or related to metabolic causes such as diabetes and hyperlipidaemia, cystic fibrosis, chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic duct obstruction. It can occasionally be caused by adjacent insulinomas [17]. Similar to fat deposition elsewhere, it may be diffuse (Fig. 4) or focal (Fig. 5) and the computed tomography (CT) attenuation of the involved parenchyma is reduced.

Fig. 4.

Diffuse fatty replacement of the pancreas in a 32-year-old with cystic fibrosis

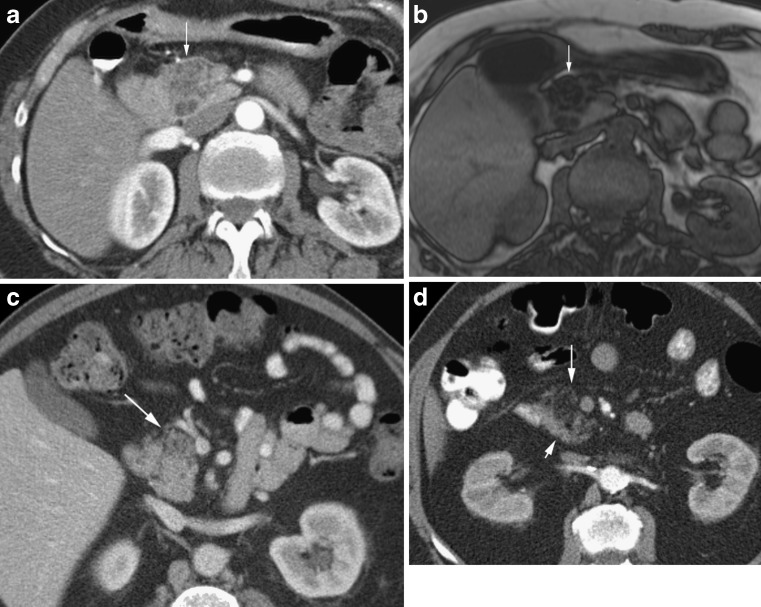

Fig. 5.

a Arterial phase CT in an 86-year-old diabetic patient with a hypodense mass-like region (arrow) in the head of the pancreas. Some elements within have Hounsfeld units of less than 50 in keeping with focal fatty infiltration. b T1 MRI out of phase MRI in the same patient at a comparable level showing signal dropout (arrow) confirming focal fatty infiltration. c Focal fatty infiltration in the anterior pancreatic head (arrow). Note the absence of mass effect. d More pronounced focal fatty infiltration of the anterior pancreatic head (long arrow) compared with the normal density posterior pancreas (short arrow)

The anterior aspect of the pancreatic head, a derivative of the embryological dorsal anlage, is most frequently involved, while the posterior aspect and parenchyma immediately surrounding the common bile duct, which are derived form the ventral anlage, are typically spared [18, 19]. When pronounced, a negative Hounsfield unit may be seen on unenhanced studies; however, mild cases may mimic a hypodense mass. Recognition of the area involved, lack of ductal dilatation and absence of distortion of the pancreatic contour are clues to this benign diagnosis. Most suspected cases should be clarified with MRI with chemical shift acquisitions, which have proved useful in differentiating focal fat infiltration from pancreatic neoplasm [20].

Lipoma

Intrapancreatic lipomas, previously thought to be rare, are being increasingly encountered. These are well-defined, homogeneous masses that do not show contrast enhancement and maintain low attenuation values of fat (Fig. 6) [21]. They are typically small, do not cause ductal obstruction and are asymptomatic.

Fig. 6.

Unenhanced CT showing a well-defined reniform fat density lipoma in the pancreatic head (arrowhead) abutting but not distorting the superior mesenteric vein (long arrow)

Vascular tumour mimics

Arteriovenous malformation

Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) of the pancreas are rare lesions that may be asymptomatic although they frequently present with gastrointestinal haemorrhage secondary to portal hypertension with pancreatitis also having been reported as a presenting complaint [22]. They typically appear as enhancing masses containing tortuous tubular vessels that follow the density of adjacent normal vessels (Fig. 7), with early enhancement of the portal venous system [23]. Their location within the pancreas is variable as is the size, with reported lesions varying between less than 1 and 10 cm.

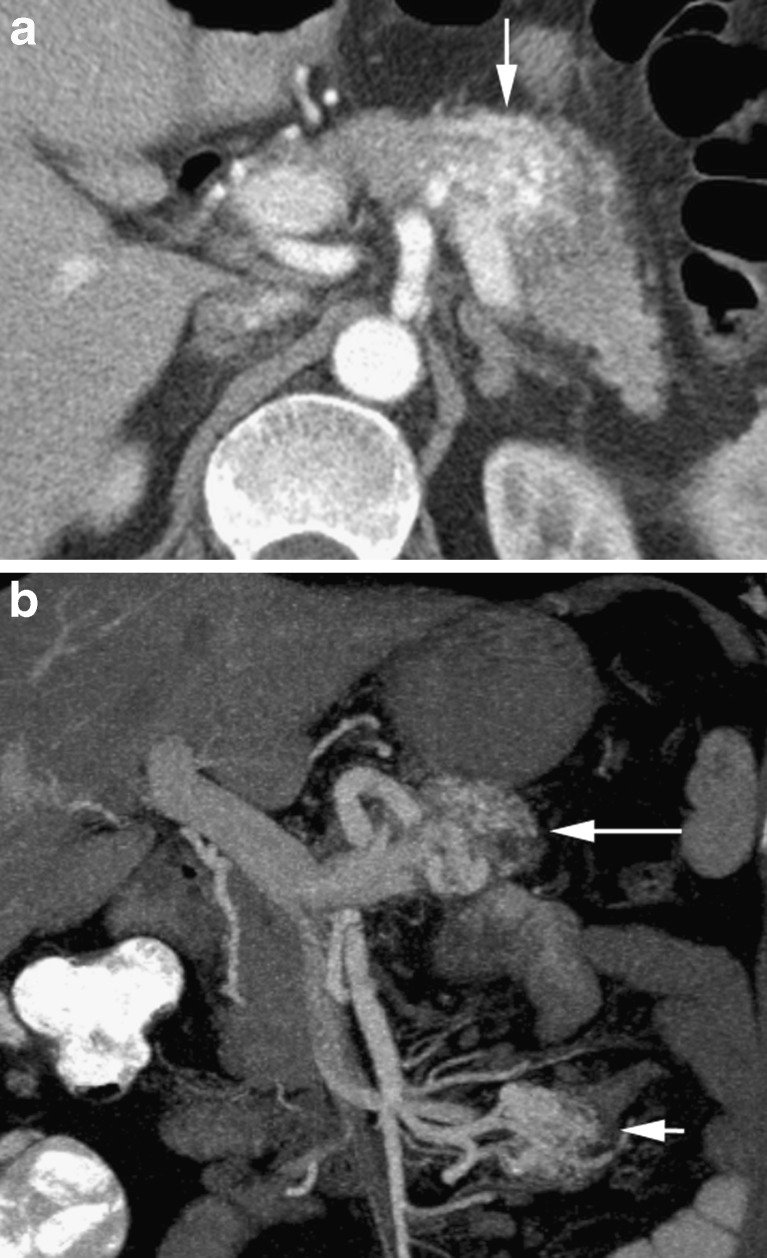

Fig. 7.

a Arterial phase CT in a 55-year-old man showing multiple tubular like enhancing structures (arrow) in an AVM of the pancreatic body with identical enhancement to vessels. b Coronal MIP in the same patient showing the tubular nature of the lesion (long arrow) and a mesenteric AVM (short arrow)

Aneurysm

Aneurysms from the splanchnic arteries are uncommon, with aneurysms of the pancreaticoduodenal and pancreatic arteries representing just 2% of all visceral artery aneurysms, and with 5% arising from the superior mesenteric artery [24]. Although many of the reports of pancreaticoduodenal artery aneurysms in the literature have presented with rupture and subsequent haemorrhage [25], they are being more frequently encountered as asymptomatic incidental findings with increasing use and improvements in abdominal CT. They may relate to atheroma, connective tissue disease, trauma, pancreatitis or be mycotic. Similar to aneurysms elsewhere the aneurysm follows the adjacent native vessel enhancement in all phases while thrombotic elements do not enhance and remain as soft tissue attenuation (Fig. 8). Peripheral calcification can occasionally be seen. Multiplanar reformations and multiphase imaging allows confident diagnosis [26].

Fig. 8.

a Arterial phase CT showing a heterogeneous mass in the pancreas. Note the arterial enhancing lumen of the gastroduodenal artery at the 11 o’clock position in the pseudo-aneurysm in this patient with previous pancreatitis. b A DSA in the same patient clearly defines the pseudoaneurysm. c A portal venous phase at the same level. Note that the feeding artery is less well appreciated and the lesion could be mistaken for a pancreatic mass or collection

Biliary tumour mimics

Choledochal cysts

Choledochal cysts are rare congenital dilatations of the biliary tree that may involve the intra- or extrahepatic bile ducts or both [27]. They are more common in females and Asians and may present with upper gastrointestinal symptoms such as pain, nausea, vomiting, jaundice, or with pancreatitis, cholangitis or biliary malignancy within the cyst [28–30]. Uncomplicated cysts will appear well defined and with fluid attenuation on CT, while when calculi, sludge or debris are present they may be more heterogeneous (Fig. 9). Demonstration of a tubular nature of the area is a clue to the diagnosis, which can be confirmed with either CT cholangiography or MR cholangiopancreatography.

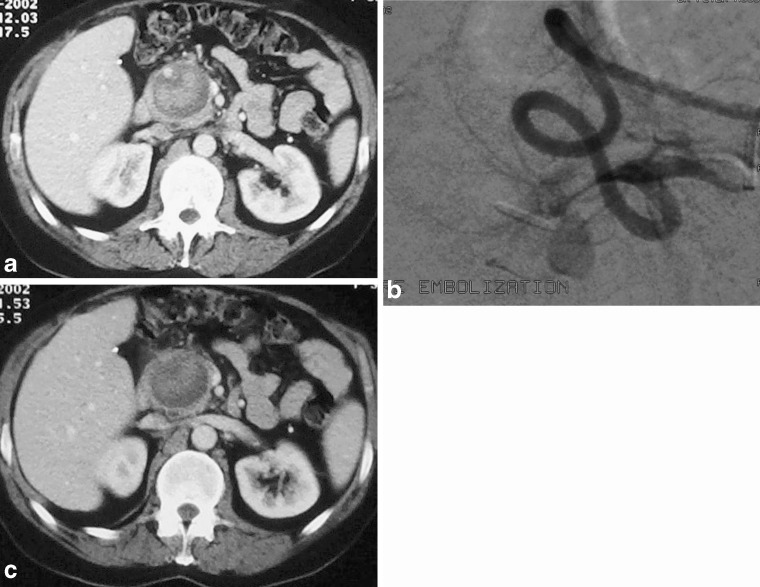

Fig. 9.

a Portal venous CT showing a heterogeneous mass (short arrows) in the pancreatic head with intrahepatic duct dilatation (long arrows). Note foci of low attenuation gas within calculi impacted in this type 1 choledochocele. b Coronal reconstruction in the same patient with the choledochocele (short arrow) and the intrahepatic duct dilatation (long arrow). The coronal better depicts the tubular nature of the cyst. c Coronal TRUFI MRI in the same patient with choledochocele (long arrow containing low signal calculi, with further stones within intrahepatic ducts (short arrow)

Peripancreatic tumour mimics

Splenunculi

Accessory spleens are common and because of embryological development with the pancreatic tail they may be closely applied to the pancreatic parenchyma or truly intrapancreatic. They are typically small, measuring 1–3 cm, are well defined and have similar enhancement to the spleen during all phases (Fig. 10) [31]. Because they enhance differently to the adjacent pancreatic parenchyma they may be mistaken for neoplasm [32], leading to inappropriate surgery. The diagnosis can be confirmed using supraparamagnetic iron oxide (SPIO)-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), sulphur colloid imaging or heat damaged red cell scintigraphy.

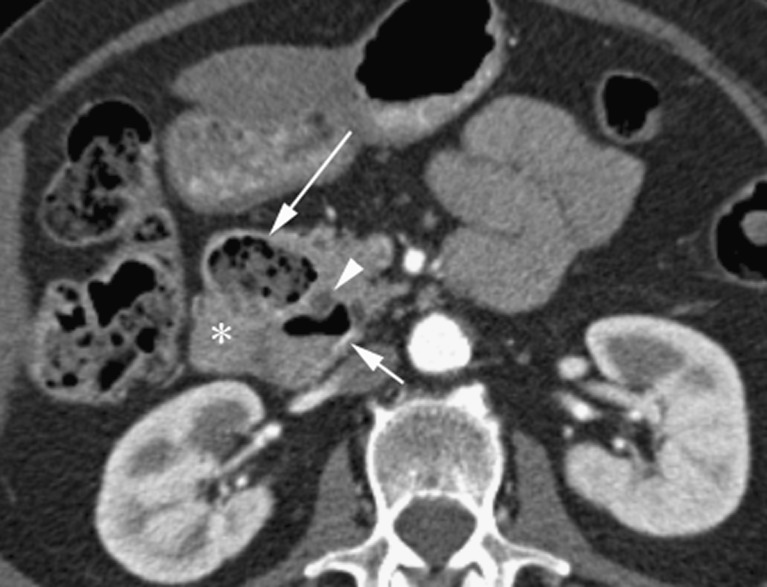

Fig. 10.

a Arterial CT showing a hyperenhancing ‘nodule’ (arrow) at the posterior aspect of the pancreatic tail. b Portal venous CT in the same patient shows the nodule (arrow) is of identical density to spleen (S) and is a splenunculus

Duodenal diverticuli

Diverticuli from the duodenum are common, occurring in up to 22% of patients [33], and are usually asymptomatic. They can be complicated by perforation, haemorrhage and duodenal diverticulitis [34]. They most frequently arise from the second and third parts of the duodenum, and are usually less than 5 cm in size. Because of their communication with the bowel lumen, they typically contain both fluid and air (Fig. 11), which usually poses no diagnostic challenge [35]. However, completely fluid-filled diverticuli may be mistaken for cystic pancreatic neoplasm [36, 37]. To further complicate matters, Lemmel first described periampullary diverticuli producing biliary obstruction, findings that have subsequently been widely confirmed [38–40]. In indeterminate cases, multiplanar CT with positive oral contrast agents may show contrast material entering the diverticulum to establish the diagnosis. MRI has also shown promise in challenging cases [41].

Fig. 11.

Arterial phase CT showing heterogeneous pancreatic head lesions with the anterior duodenal diverticulum (long arrow) containing food debris, and the posterior diverticulum (short arrow) having an air fluid level. Note the sandwiching of the common bile duct (arrowhead)

Other duodenal pathological features that may be mistaken for pancreatic neoplasia are congenital duodenal duplication, duodenal haematomas and duodenal malignancies (Fig. 12). Annular pancreas may be mistaken for enlargement of the pancreatic head, or the centrally located duodenum may be mistaken for a focal lesion if this congenital anomaly is not recognised (Fig. 13).

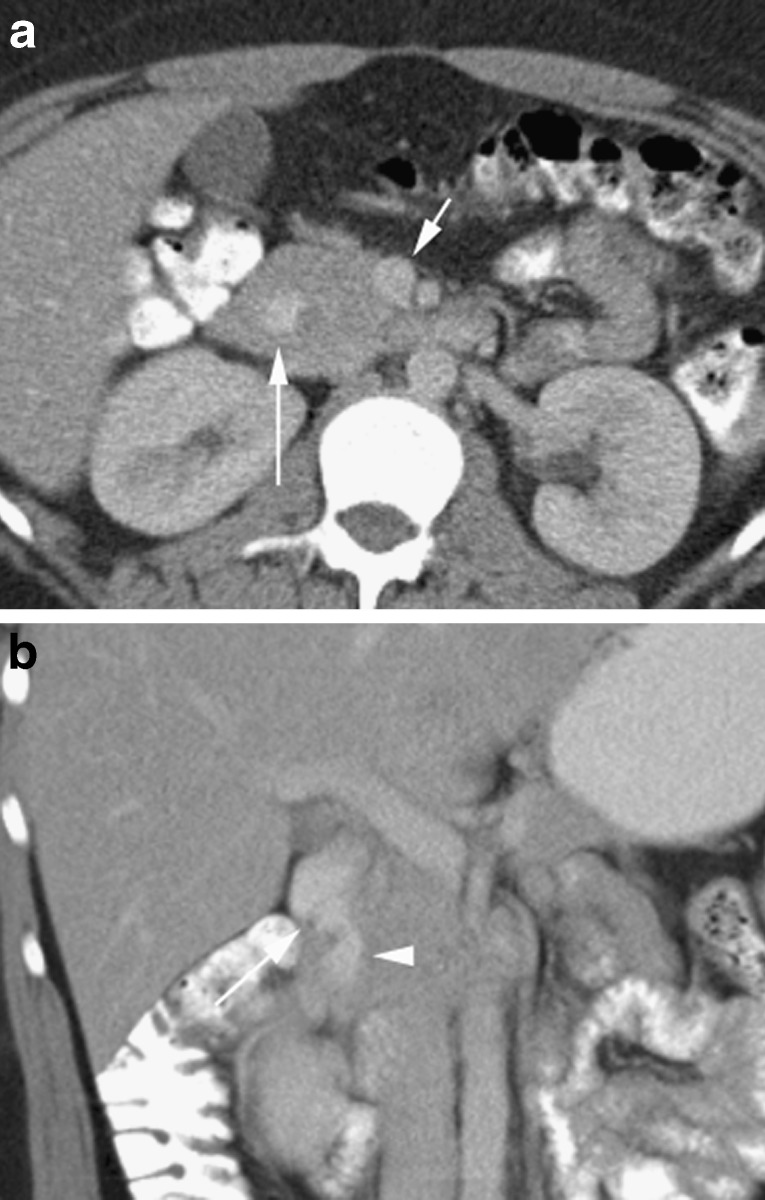

Fig. 12.

a Large mass replacing the head of the pancreas (long arrow) also fills the second part of the duodenum (short arrow) and was a duodenal carcinoid. Note the subtle arterially enhancing hepatic metastasis (arrowhead). b Portal venous coronal CT in a 55-year-old with distended pancreatic duct (long arrow) and common bile duct (arrowhead) secondary to an ampullary carcinoma (short arrow)

Fig. 13.

a Axial portal venous CT in a 22-year-old with a structure in the pancreatic head (long arrow) of similar density to the superior mesenteric vein (short arrow). b A coronal reformat shows this to be tubular (arrowhead) representing oral contrast agent within the second part of the duodenum in a patient with annular pancreas

Peripancreatic nodes

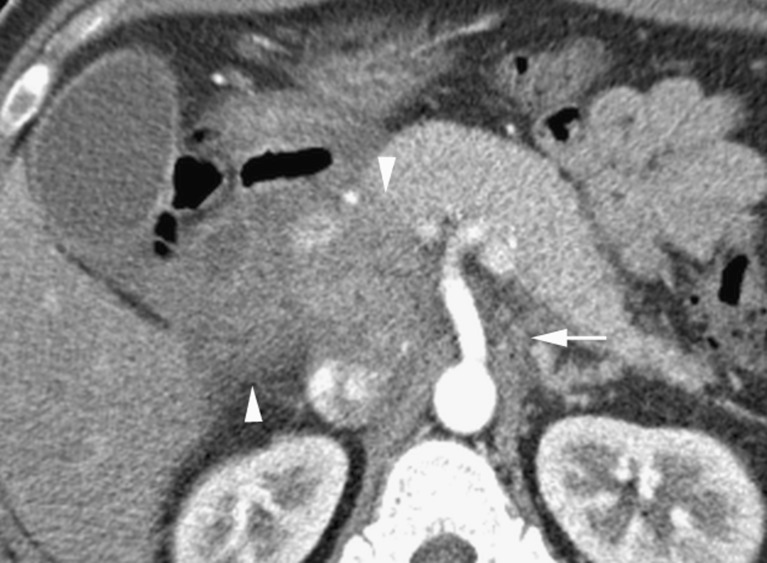

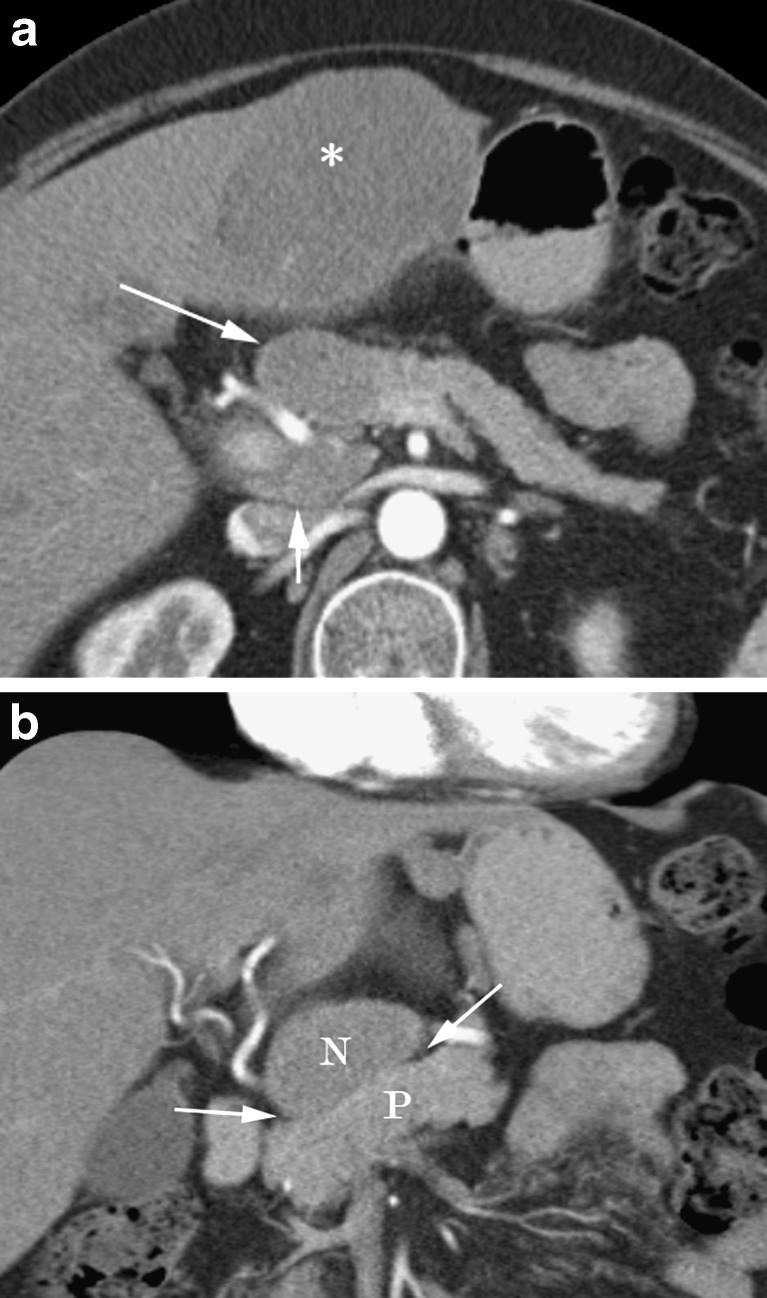

There are multiple normal lymph node groups that surround the pancreas. These can become involved in multiple disease processes, including mycobacterial infections (Fig. 14) [42], gastric, biliary and hepatic malignancy [43], pancreatitis [44], lymphoma [45], sclerosing mesenteritis [46] and sclerosing cholangitis [47]. They are typically hypodense compared with pancreas in the arterial phase and often a fat plane may be demonstrated between the nodal mass and pancreas (Fig. 15) [48]. Furthermore, lymph nodes inferior to the renal veins virtually exclude pancreatic adenocarcinoma [45].

Fig. 14.

Peripancreatic nodes (arrowheads) inseparable from the head of the pancreas and passing towards the liver, encasing the portal vein in a 27-year-old man with peripancreatic tuberculosis

Fig. 15.

a Arterial phase CT in a 64-year-old woman with a past history of breast cancer showing an hepatic mass (asterisk), an apparent hypodense mass in the head of the pancreas (long arrow) and a portocaval node (short arrow). b A coronal reformat shows a fat plane (arrows) between the breast cancer nodal metastasis (N) and the normal pancreas (P)

Direct invasion

The pancreas may be invaded directly by a number of tumours such as adrenal carcinomas, gastric carcinomas and gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs), renal tumours and retroperitoneal sarcomas. Determining the epicentre of these tumours can help to identify their true organ of origin.

Conclusion

A number of pancreatic and peripancreatic conditions may mimic pancreatic neoplasm. A thorough knowledge of these and detailed interrogation of all lesions will allow many to be accurately diagnosed on CT. Lesions that remain indeterminate may require further investigation.

References

- 1.Sunnapwar A, Prasad SR, Menias CO, et al. Nonalcoholic, nonbiliary pancreatitis: cross-sectional imaging spectrum. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195:67–75. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.4048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim T, Murakami T, Takamra M, et al. Pancreatic mass due to chronic pancreatitis: correlation of CT and MR imaging features with pathologic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177:367–371. doi: 10.2214/ajr.177.2.1770367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takahashi N, Fletcher JG, Hough DM, et al. Autoimmune pancreatitis: differentiation from pancreatic carcinoma and normal pancreas on the basis of enhancement characteristics at dual-phase CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:479–484. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P, Cavallini G, et al. Pancreatitis and the risk of pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(20):1433–1437. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199305203282001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casetti L, Bassi C, Salvia R, et al. “Paraduodenal” pancreatitis: results of surgery on 58 consecutives patients from a single institution. World J Surg. 2009;33:2664–2669. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0238-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Itoh S, Yamakawa K, Shimamoto K, et al. CT findings in groove pancreatitis: correlation with histopathological findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1994;18(6):911–915. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199411000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tezuka K, Makino T, Hirai I, Kimura W. Groove pancreatitis. Dig Surg. 2010;27:149–152. doi: 10.1159/000289099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gabata T, Kakoya M, Terayama N, et al. Groove pancreatic carcinomas: radiological and pathological findings. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:1679–1684. doi: 10.1007/s00330-002-1743-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edward L, Bradley III. A clinically based classification system for acute pancreatitis: summary of the International Symposium on Acute Pancreatitis, Atlanta, GA, September 11–13, 1992. Arch Surg. 1993;128:586–590. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1993.01420170122019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kosmahl M, Pauser U, Peters K, et al. Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas and tumor-like lesions with cystic features: a review of 418 cases and classification proposal. Virchows Arch. 2004;445:168–178. doi: 10.1007/s00428-004-1043-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim SH, Lim JH, Lee WJ, Lim HK. Macroscopic pancreatic lesions: differentiation of benign from premalignant and malignant cysts by CT. Eur J Radiol. 2009;71:122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goh BKP, Tan YM, Thng CH, et al. How useful are clinical, biochemical, and cross-sectional imaging features in predicting potentially malignant or malignant cystic lesions of the pancreas? Results from a single institution experience with 220 surgically treated patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.06.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewandrowski KB, Southern JF, Pins MR, et al. Cyst fluid analysis in the differential diagnosis of pancreatic cysts: a comparison of pseudocysts, serous cystadenomas, mucinous cystic neoplasms, and mucinous cystadenocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 1993;217(1):41–47. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199301000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang XM, Mitchell DG, Dohke M, et al. Pancreatic cysts: depiction on single-shot fast spin-echo MR Images. Radiology. 2002;223:547–553. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2232010815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Handrich SJ, Hough DM, Fletcher JG, Sarr MG. The natural history of the incidentally discovered small simple pancreatic cyst: long-term follow-up and clinical implications. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184(1):20–23. doi: 10.2214/ajr.184.1.01840020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tanaka S, Nakao M, Ioka T, et al. Slight dilatation of the main pancreatic duct and presence of pancreatic cysts as predictive signs of pancreatic cancer: a prospective study. Radiology. 2010;254:965–972. doi: 10.1148/radiol.09090992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eriguchi N, Aoyagi S, Hara M, et al. Insulinoma occurring in association with fatty replacement of unknown etiology in the pancreas: report of a case. Surg Today. 2000;30:937–941. doi: 10.1007/s005950070050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsumoto S, Mori H, Miyake H, et al. Uneven fatty replacement of the pancreas: evaluation with CT. Radiology. 1995;194:453–458. doi: 10.1148/radiology.194.2.7824726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawamoto S, Siegelman SS, Bluemke DA, Hruban RH, Fishman EK. Focal fatty infiltration in the head of the pancreas: evaluation with multidetector computed tomography with multiplanar reformation imaging. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2009;33:90–95. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e31815cff0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim HJ, Byun JH, Park SH, et al. Focal fatty replacement of the pancreas: usefulness of chemical shift MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188(2):429–432. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hois EL, Hibbeln JF, Sclamberg JS. CT appearance of incidental pancreatic lipomas: a case series. Abdom Imaging. 2006;31:332–338. doi: 10.1007/s00261-005-0362-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanno A, Satoh K, Kimura K, et al. Acute pancreatitis due to pancreatic arteriovenous malformation: 2 case reports and a review of the literature. Pancreas. 2006;32(4):422–425. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000220869.72411.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ogawa H, Itoh S, Mori Y, et al. Arteriovenous malformation of the pancreas: assessment of the clinical and multislice CT features. Abdom Imaging. 2009;34:743–752. doi: 10.1007/s00261-008-9465-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Messina LM, Shanley CJ. Visceral artery aneurysms. Surg Clin North Am. 1997;77(2):425–442. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6109(05)70559-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bageacu S, Cuilleron M, Kaczmarek D, Porcheron J. True aneurysms of the pancreaticoduodenal artery: successful non-operative management. Surgery. 2006;139:608–16. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horton KM, Smith C, Fishman EK. MDCT and 3D CT angiography of splanchnic artery aneurysms. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189:641–647. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Todani T, Watanabe Y, Narusu M, et al. Congenital bile duct cysts: classification, operative procedures, and review of thirty-seven cases including cancer arising from choledochal cyst. Am J Surg. 1977;134(2):263–239. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(77)90359-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiseman K, Buczkowski AK, Chung SW, et al. Epidemiology, presentation, diagnosis, and outcomes of choledochal cysts in adults in an urban environment. Am J Surg. 2005;189:527–531. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dhupar R, Gulack B, Geller DA et al (2009) The changing presentation of choledochal cyst disease: an incidental diagnosis. HPB Surg 2009:103739. doi:10.1155/2009/103739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Hopkins NFG, Benjamin IS, Thompson MH, Williamson RCN. Complications of choledochal cysts in adulthood. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1990;72:229–235. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spencer LA, Spizarny DL, Williams TR. Imaging features of intrapancreatic accessory spleen. Br J Radiol. 2010;83:668–673. doi: 10.1259/bjr/20308976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meyer-Rochow GY, Gifford AJ, Samra JS, Sywak MS. Intrapancreatic splenunculus. Am J Surg. 2007;194(1):75–76. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ackermann W. Diverticula and variations of the duodenum. Ann Surg. 1943;117:403–413. doi: 10.1097/00000658-194303000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ichikawa T, Koizumi J, Onous K, et al. CT features of juxtapapillary duodenal diverticula with complications. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. 2008;33(2):90–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wiesner W, Beglinger C, Oertil D, Steinbrich W. Juxtapapillary duodenal diverticula: MDCT findings in 1010 patients and proposal for a new classification. JBR BTR. 2009;92:191–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hariri A, Siegelman SS, Hruban RH. Duodenal diverticulum mimicking a cystic pancreatic neoplasm. Br J Radiol. 2005;78:562–564. doi: 10.1259/bjr/52543195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Macari M, Lazarus IG, Megibow A. Duodenal diverticula mimicking cystic neoplasms of the pancreas: CT and MR imaging findings in seven patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:195–199. doi: 10.2214/ajr.180.1.1800195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ono M, Kamisawa T, Tu Y, Egawa Initials. MRCP and ERCP in Lemmel Syndrome. JOP. 2005;6(3):277–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoneyama F, Miyata K, Ohta H, et al. Excision of a juxtapapillary duodenal diverticulum causing biliary obstruction: report of three cases. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2004;11(1):69–72. doi: 10.1007/s00534-003-0854-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schnueriger B, Vorburger SA, Banz VM, et al. Diagnosis and management of the symptomatic duodenal diverticulum: a case series and a short review of the literature. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1571–1576. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0549-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Balci NC, Noone T, Akun E, et al. Juxtapapillary diverticulum: Findings on MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2003;17(4):487–492. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hawkins CC, Gold JWM, Whimbey E, et al. Mycobacterium avium complex infections in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Ann Int Med. 1986;105(2):184–188. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-105-2-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Efremidis SC, Vougiouklis N, Zafiriadou E, et al. Pathways of lymph node involvement in upper abdominal malignancies: evaluation with high-resolution CT. Eur Radiol. 1999;9:868–874. doi: 10.1007/s003300050757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sahani DV, Kalva SP, Farrell J, et al. Autoimmune pancreatitis imaging features. Radiology. 2004;233:345–352. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2332031436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Merkle EM, Bender GN, Brambs HJ. Imaging findings in pancreatic lymphoma: differential aspects. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174:671–675. doi: 10.2214/ajr.174.3.1740671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Horton KM, Lawler LP, Fishman EK. CT findings in sclerosing mesenteritis (panniculitis): spectrum of disease. Radiographics. 2003;23:1561–1567. doi: 10.1148/rg.1103035010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnson KJ, Olliff JF, Olliff SP. The presence and significance of lymphadenopathy detected by CT in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Br J Radiol. 1998;71:1279–1282. doi: 10.1259/bjr.71.852.10319001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zeman RK, Schiebler M, Clark LR, et al. The clinical and imaging spectrum of pancreaticoduodenal lymph node enlargement. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1985;144:1223–1227. doi: 10.2214/ajr.144.6.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]