Abstract

The three-dimensional crystal structure of Escherichia coli NhaA determined at pH 4 provided the first structural insights into the mechanism of antiport and pH regulation of a Na+/H+ antiporter. However, because NhaA is activated at physiological pH (pH 6.5–8.5), many questions pertaining to the active state of NhaA have remained open including the structural and physiological roles of helix IX and its loop VIII–IX. Here we studied this NhaA segment (Glu241–Phe267) by structure-based biochemical approaches at physiological pH. Cysteine-scanning mutagenesis identified new mutations affecting the pH dependence of NhaA, suggesting their contribution to the “pH sensor.” Furthermore mutation F267C reduced the H+/Na+ stoichiometry of the antiporter, and F267C/F344C inactivated the antiporter activity. Tests of accessibility to [2-(trimethylammonium)ethyl]methanethiosulfonate bromide, a membrane-impermeant positively charged SH reagent with a width similar to the diameter of hydrated Na+, suggested that at physiological pH the cytoplasmic cation funnel is more accessible than at acidic pH. Assaying intermolecular cross-linking in situ between single Cys replacement mutants uncovered the NhaA dimer interface at the cytoplasmic side of the membrane; between Leu255 and the cytoplasm, many Cys replacements cross-link with various cross-linkers spanning different distances (10–18Å) implying a flexible interface. L255C formed intermolecular S–S bonds, cross-linked only with a 5-Å cross-linker, and when chemically modified caused an alkaline shift of 1 pH unit in the pH dependence of NhaA and a 6-fold increase in the apparent Km for Na+ of the exchange activity suggesting a rigid point in the dimer interface critical for NhaA activity and pH regulation.

Regulation of intracellular pH, cellular Na+ content, and cell volume is essential for all living cells. Na+/H+ antiporters play primary roles in these crucial processes. They are integral membrane proteins, ubiquitous throughout the biological kingdom. Many Na+/H+ antiporters are tightly regulated by pH, a property that underpins their capacity to maintain pH homeostasis of the cytoplasm (1).

NhaA, the main Na+/H+ antiporter of Escherichia coli, has eukaryotic orthologs, including human (2, 3). It is an electrogenic antiporter with a stoichiometry of 2 H+/1 Na+ (1, 4) and is strongly dependent on pH; its rate of activity changes over 3 orders of magnitude between pH 7.0 and 8.5 (1, 4, 5).

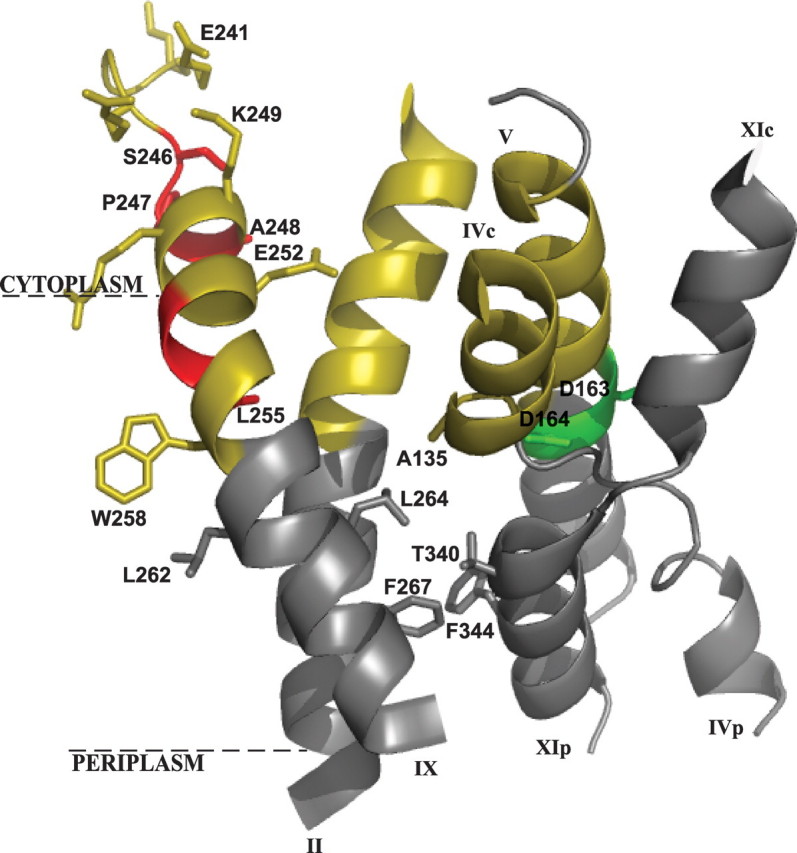

NhaA is a dimer in the native membrane as revealed by genetic complementation data, biochemical pulldown experiments, intermolecular cross-linking (6), ESR studies (7, 8), and cryoelectron microscopy of two-dimensional crystals (9, 10). The recently determined crystal structure of NhaA monomer at pH 4 (11) has provided the first structural insights into the mechanism of antiport and pH regulation of a Na+/H+ antiporter. NhaA consists of 12 TMSs2 with the N and C termini pointing into the cytoplasm. It represents a novel fold; TMSs IV and XI are each comprised of two short helices connected by extended chains that cross each other, in close contact, in the middle of the membrane (TMS IV/XI assembly (11) and Fig. 1). This creates a delicately balanced electrostatic environment in the middle of the membrane. An ion funnel opens to the cytoplasm with a negatively charged orifice that is most suitable to act as a cation trap and a “pH sensor.” The funnel (designated cytoplasmic) ends in the middle of the membrane in the vicinity of the putative ion binding site and the crossing of the TMS IV/XI assembly. Together these structural elements have been suggested to play a crucial role in the pH-controlled Na+/H+ exchange mechanism (11).

FIGURE 1.

Structure of the cytoplasmic funnel. Shown is a crystal structure-based ribbon representation of the cytoplasmic funnel (colored yellow) composed of TMSs II, IVc (c and p denote cytoplasmic and periplasmic sides, respectively), V, and IX. The TMS IV/XI assembly of short helices connected by extended chains is shown (11). The NhaA dimer interface is marked in red, the putative ion binding site is in green, and the membrane is represented by a broken line. The representation was generated using PyMOL (DeLano Scientific LLC).

Based on the NhaA crystal structure obtained at pH 4, very crucial functional and structural roles have also been assigned to TMS IX and the neighboring part of loop VIII–IX in the mechanism and pH regulation of NhaA. It contains amino acid residues that may (a) participate in the pH sensor at the orifice of the cytoplasmic funnel, (b) connect TMS IX to TMS XI of the TMS IV/XI assembly, (c) line the cytoplasmic cation funnel leading to the active site, and (d) line the NhaA dimer interface.

The three-dimensional structure of NhaA monomer agrees with the electron density map obtained by cryoelectron microscopy of the two-dimensional crystal, implying that it represents a native conformation in the membrane (12). However, because both the two-dimensional and three-dimensional crystals were obtained at pH 4, at which NhaA is down-regulated, the structure of the active conformation(s) and the process(s) leading to it have remained open questions. Hence it is crucial to conduct experiments, both structurally and functionally oriented, at physiological pH at which NhaA is active to obtain a working model for the mechanism of activity and pH regulation of the antiporter at physiological pH. The present study examined the roles of TMS IX and the neighboring part of loop VIII–IX at physiological pH when NhaA is active.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bacterial Strains and Culture Conditions—EP432 is an E. coli K-12 derivative, which is melBLid, ΔnhaA1::kan, ΔnhaB1::cat, ΔlacZY, thr1 (13). TA16 is nhaA+nhaB+lacIQ (TA15lacIQ) and otherwise isogenic to EP432 (4). Cells were grown in modified L broth (LBK, L broth in which Na+ is replaced by K+) (14) or in minimal medium A without sodium citrate (15) with 0.5% glycerol, 0.01% MgS04·7H2O, and 2.5 μg/ml thiamine. Antibiotic was 100 μg/ml ampicillin. The resistance to Na+ was tested in Na+ selective medium: LB containing 0.6 m NaCl buffered with 60 mm 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl) propane-1,3-diol; pH was adjusted with HCl to pH 7 or pH 8.3. For plates, 1.5% agar was used.

Plasmids—All plasmids used have pBR322 origin of replication and carry bla (AmpR). pCL-BSTX, a pCL-GMAR100 derivative (16) encodes Cys-less NhaA with a silent BstX site at codon 248 in nhaA. pCL-AXH3, a derivative of pCL-AXH2, contains a BstXI silent site at codon 248 in nhaA (17). It expresses cysteineless NhaA (CL-NhaA) from the tac promoter fused at its C terminus to two factor Xa cleavage sites followed by a His6 tag. pCL-HAH4 is a derivative of pCL-HAH3 (18), bearing the silent BstXI mutation at codon 248 in nhaA. It expresses from the tac promoter a variant of CL-NhaA of which segment Arg383–Val388 was replaced by a hemagglutinin epitope followed by two factor Xa cleavage sites and a His6 tag. All plasmids carrying mutations are designated by the name of the plasmid followed by the mutation.

Site-directed Mutagenesis—Site-directed mutagenesis was conducted following a polymerase chain reaction-based protocol (19) or site-directed mutagenesis facilitated by DpnI selection on hemimethylated DNA (20).

For Cys replacement of Lys242, His243, Gly244, Arg245, Ser246, Pro247, Ala248, Lys249, Arg250, Leu251, His253, Leu255, Trp258, and Leu262, pCL-HAH4 was used as a template. For Cys replacement of His256, Pro257, and Val259 pCL-AXH3 was used as template. For Cys replacement of Leu264, Phe267, Phe344, and Phe267/Phe344 pCL-AXH3 and pCL-BstX were used as templates. All mutations were verified by DNA sequencing of the entire gene through the ligation junctions with the vector plasmid.

Isolation of Membrane Vesicles and Assay of Na+/H+ Antiporter Activity—EP432 cells transformed with the respective plasmids were grown in LBK medium, and everted membrane vesicles were prepared and used to determine the Na+/H+ antiporter activity as described previously (21, 22). The assay of antiport activity was based upon the measurement of Na+-induced changes in the ΔpH as measured by acridine orange, a fluorescent probe of ΔpH. The fluorescence assay was performed with 2.5 ml of reaction mixture containing 50–100 μg of membrane protein, 0.5 μm acridine orange, 150 mm KCl, 50 mm 1,3-bis[tris(hydroxymethyl)methylamino]propane, and 5 mm MgCl2, and the pH was titrated with HCl as indicated. After energization with either ATP or d-lactate (2 mm, pH 7 titrated by KOH), quenching of the fluorescence was allowed to achieve a steady state, and then Na+ was added. A reversal of the fluorescence level (dequenching) indicates that protons are exiting the vesicles in antiport with Na+. As shown previously, the end level of dequenching is a good estimate of the antiporter activity (23), and the concentration of the ion that gives half-maximal dequenching is a good estimate of the apparent Km for Na+ (or Li+) of the antiporter (23, 24). The concentration range of the cations tested was 0.01–100 mm at the indicated pH values, and the apparent Km values were calculated by linear regression of the Lineweaver-Burk plot. High pressure membranes were isolated as described previously (25).

Protein Purification—For extraction of NhaA, membranes (0.5 mg of membrane protein) were resuspended in 1.15 ml of a solution containing 4.3 mm Tris/Cl (pH 7.5), 110 mm sucrose, and 60 mm choline chloride supplemented with 20% glycerol, 1% β-dodecyl maltoside, and 0.1 m MOPS (pH 7). The suspension was incubated for 20 min at 4 °C and centrifuged (Beckman TLA 100.4; 265,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C). For affinity purification of NhaA, the supernatant was added to 50 μl of Ni2+-NTA-agarose (Qiagen) and incubated with agitation for 1 h at 4 °C. Then beads were washed in binding and washing buffers (26). The protein was eluted in 200 μl of acid elution buffer (27) or by incubation for 20 min at 4 °C in 20 μl of SDS-PAGE sampling buffer supplemented with 300 mm imidazole and centrifuged (Eppendorf; 20,800 × g for 2 min at 4 °C).

Protein Determination—The protein was determined according to Bradford (28).

Detection and Quantification of NhaA and Its Mutated Proteins in the Membrane—NhaA and its mutated derivatives in membranes were quantitated in membranes by Western analysis as described previously (29) using the NhaA-specific monoclonal antibody 1F6 (30) or by resolving the affinity-purified proteins by SDS-PAGE, staining with Coomassie Blue, and quantification of the band density by Image Gauge (Fuji) software (6).

Accessibility of Cys Replacements of CL-NhaA to Impermeant Sulfhydryl Reagent MTSET—The accessibility assay in intact cells was performed as described previously (31), but the Tris buffer was replaced with 100 mm potassium phosphate and 5 mm MgSO4 (pH 7.5 or 8.5). For assay of accessibility to MTSET from the cytoplasmic side, everted membrane vesicles (500 μg of membrane protein) were incubated with 10 mm MTSET in the phosphate buffer (at pH 7.5 or 8.5) at room temperature with gentle shaking for 45 min. Then the reaction was stopped by dilution into 3 ml of TSC buffer (containing 10 mm Tris (pH 7.5), 250 mm sucrose, and 140 mm choline chloride) and centrifuged (Beckman TLA 100.4; 265,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C). The protein was extracted, affinity-purified on Ni+2-NTA, and left on the beads. The beads were washed twice in binding buffer (26) at pH 7.4, resuspended in 100 μl of binding buffer containing 0.2 mm fluorescein-5-maleimide (Molecular Probes), and further incubated for 30 min at 25 °C to determine the Cys left free following MTSET treatment. Then the beads were washed, and the protein was eluted in a sample buffer containing 300 mm imidazole and separated by SDS-PAGE. For evaluation of the fluorescence intensity, the gels were photographed under UV light (260 nm) as described previously (18). For quantifying the amount of the protein, the gels were Coomassie Blue-stained, and the density of the bands was determined. After normalization of the fluorescence intensity to the amount of protein in the band, the accessibility to MTSET was determined from the difference in the fluorescence of the reagent-treated and untreated samples (100% fluorescence = 0% modification by MTSET (18)).

In Situ Site-directed Intermolecular Cross-linking—Site-directed intermolecular cross-linking was conducted in situ on high pressure membrane vesicles isolated from TA16 cells overexpressing the various NhaA mutants (25). Membranes (500 μg of membrane protein) were resuspended in a buffer (0.5 ml) containing 100 mm potassium phosphate (pH 7.5 or 8.5), 5 mm MgSO4, and one of the freshly prepared homobifunctional cross-linkers: 2 mm BMH (Pierce), 1 mm o-PDM (Sigma), 1 mm p-PDM (Sigma), 2 mm MTS-2-MTS (Toronto Research Chemicals), or a 4 mm concentration of the oxidizing reagent diamide (Sigma). The stock solutions of the cross-linkers were prepared in N,N-dimethylformamide so that the amount of N,N-dimethylformamide in the reaction mixture did not exceed 1%, a concentration that does not affect the antiporter activity. The reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature with gentle rotation for 45 min, and the reaction was terminated by 10 mm β-mercaptoethanol in the case of maleimides (BMH, o-PDM, and p-PDM) or by dilution in TSC buffer (in the case of MTS-2-MTS and diamide). Then the affinity-purified proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (non-reducing conditions in the case of treatment with MTS-2-MTS and diamide) and Coomassie Blue-stained to determine the densities of the bands with mobility corresponding to that of NhaA monomers and dimers (6, 18). The sum of the densities of the monomers and dimers equals 100%. Measurement of accessibility to the cross-linking reagents was performed on the proteins bound to the beads as described above for MTSET.

Treatment of Membranes Expressing Cys Replacement Mutations with SH Reagents for Activity Assay—Membranes (0.5 mg of membrane protein) were resuspended in a reaction mixture as described above for cross-linking but containing one of the following reagents: 1 mm NEM, 1 mm MTSES (Anatrace), 1 mm MTSET (Anatrace), 1 mm AMS (Molecular Probes), or a 4 mm concentration of the oxidizing reagent diamide. The reaction mixture was incubated with gentle shaking for 20 min at room temperature. The reaction was stopped by addition of 3 ml of TSC buffer (containing 10 mm β-mercaptoethanol in the case of maleimide reagents) and centrifugation (Beckman TLA 100.4; 265,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C). The membranes were resuspended in TSC buffer (5–10 mg of membrane protein/ml), and the Na+/H+ antiporter activity was monitored as described above. For determination of accessibility to the SH reagents, the protein was affinity-purified, and free Cys residues were determined by fluorescein-5-maleimide labeling as described above for MTSET.

Reconstitution of NhaA into Proteoliposomes and Measurement of ΔpH-driven 22Na Uptake—NhaA proteoliposomes were reconstituted and ΔpH-driven 22Na uptake was determined as described previously (4, 32). All experiments were repeated at least twice with practically identical results.

RESULTS

Cys Replacement Mutations, Expression in the Membrane, and Growth Phenotypes at Physiological pH—The crystal structure of the acid pH-locked conformation of NhaA (11) and structure-based computation (33) combined with genetic and biochemical data (16, 25) have suggested that the cytoplasmic end of helix IX and the in-tandem part of loop VIII–IX contain amino acid residues involved in the pH sensor of NhaA. To identify these residues, we systematically replaced with Cys the amino acids residues (each separately) in segment Glu241–Val259 of NhaA excluding E241C, V254C (6, 25), and E252C (16) that were isolated previously (Fig. 1). In addition, Leu262, Leu264, and Phe267 were replaced with Cys (Fig. 1). The latter two amino acids have been shown by the crystal structure to be close enough to interact with TMS XI residues and therefore, even with no experimental support, have been assigned a structural and/or functional role in the translocation machinery (Ref. 11 and Fig. 1). All mutants were constructed in CL-NhaA, a variant that is as expressed and active as the native NhaA (26). The mutations were subjected to structural and functional studies at the physiological pH (pH 6.5–8.5) to reveal the physiological role of the replaced residues when NhaA is progressively activated with increasing pH (1, 4). Challenging the results obtained at the physiological pH with the predictions based on the acid pH-locked crystal structure also allowed us to deduce whether pH-induced conformational changes occurred during the activation process. To characterize the mutations with respect to growth, expression, and antiporter activity, the mutated plasmids were transformed into EP432, an E. coli strain that lacks the two Na+-specific antiporters (NhaA and NhaB (13)). This strain neither grows on selective media (0.6 m NaCl at pH 7 or 8.3) nor exhibits any Na+/H+ antiporter activity in isolated everted membrane vesicles unless transformed with a plasmid encoding an active antiporter (for a review, see Ref. 1; see also Table 1). As compared with the level of expression of the wild type (100%), all mutants were expressed at roughly 40% of wild type level (Table 1) from the multicopy plasmids. The mutant proteins, affinity-purified on a Ni+2-NTA column, were readily detected by Coomassie Blue staining. Notably this expression level is far above that obtained from a single chromosomal gene that confers a wild type phenotype (29). Whereas most of the single mutants conferred upon EP432 Na+ resistance similar to that of the wild type (Table 1), a few mutants grew somewhat less efficiently on the selective media as was evident by smaller colony number and colony size at either pH (K242C) or only at alkaline pH (R250C and H253C). Most interestingly, mutant F267C grew very similarly to the wild type at neutral pH but did not grow at all at alkaline pH (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Cys replacements of residues in loop VIII–IX, TMS IX, and TMS XI of NhaA For characterization of the mutations, EP432 cells were transformed with the plasmids carrying the indicated mutations. The expression level was expressed as a percentage of the control cells (EP432/pCl-HAH4) encoding CL-NhaA. Growth experiments were conducted on agar plates at 37 °C with high Na+ (0.6 m) at the indicated pH values. + + +, number and size of the colonies after 48 h of incubation at neutral pH; + +, number as above but smaller sized colonies after 48 h of incubation at alkaline pH; +, both number and size of colonies were reduced; –, no growth. The apparent Km for NaCl was determined at pH 8.5 as described under “Experimental Procedures.” ND, not determined.

|

Mutation |

Expression |

Growth, 0.6 m NaCl |

Apparent Km, Na+ |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH 7 | pH 8.3 | |||

| % | mm | |||

| E241Ca | 120 | + + + | + + | ND |

| K242C | 48 | + | + | 1.9 |

| H243C | 116 | + + + | + + | 1.2 |

| G244C | 82 | + + + | + + | 0.9 |

| R245C | 87 | + + + | + + | 4.8 |

| S246C | 98 | + + + | + + | 1.7 |

| P247C | 161 | + + + | + + | 1.2 |

| A248C | 84 | + + + | + + | 1.3 |

| K249C | 80 | + + + | + + | 2.6 |

| R250C | 89 | + + + | + | 1.9 |

| L251C | 72 | + + + | + + | 2 |

| E252C | 83 | + + + | + + | 10 |

| H253C | 37 | + + + | + | 1.5 |

| V254Ca | 110 | + + + | + + | ND |

| L255C | 47 | + + + | + + | 0.8 |

| H256C | 80 | + + + | + + | 3.5 |

| P257C | 50 | + + + | + + | 0.6 |

| W258C | 81 | + + + | + + | 0.4 |

| V259C | 50 | + + + | + + | 1.4 |

| L262C | 78 | + + + | + + | 0.6 |

| L264C | 83 | + + + | + + | 0.9 |

| F267C | 95 | + + + | – | 0.8 |

| F344C | 40 | + + + | + | 0.16 |

| F267C/F344C | 37 | – | – | |

| CL-NhaA | 100 | + + + | + + | 0.5 |

| pBR322 | – | – | ||

The data were obtained from Ref. 25

The Na+/H+ Antiporter Activity of the Mutants at Physiological pH—To assess the involvement of the Cys-replaced amino acid residues in the pH sensor of NhaA, we studied the antiporter activity of the mutants at the pH range (pH 6.5–8.5) that activates NhaA (1, 4). The Na+/H+ antiport activity was measured in everted membrane vesicles isolated from EP432 transformed with the plasmids encoding the various mutations. The activity was estimated from the change caused by Na+ to the ΔpH maintained across the membrane as measured by acridine orange, a fluorescent probe of ΔpH (Fig. 2A). EP432 transformed with plasmid encoding CL-NhaA or the vector plasmid pBR322 served as positive (Fig. 2, A and B, and Table 1) and negative (Table 1) controls, respectively. The apparent Km values for Na+ at pH 8.5 (half-maximal dequenching) of the Na+/H+ antiporter activity was determined for each mutant (Table 1). The apparent Km for Na+ of many mutants was very similar to that of the wild type (0.5 mm). The largest difference, an increase of 4–10-fold, was mainly observed with Cys replacements of potentially positively charged residues, K242C, R245C, K249C, R250C, and H256C (Table 1). Notably Cys replacement E252C was shown previously to have an apparent Km for Na+ of at least 10 times that of the wild type (Ref. 16 and Table 1). Here we found that Cys replacement L251C (next to Glu252) also increased by 4-fold the apparent Km for Na+ of NhaA (Table 1).

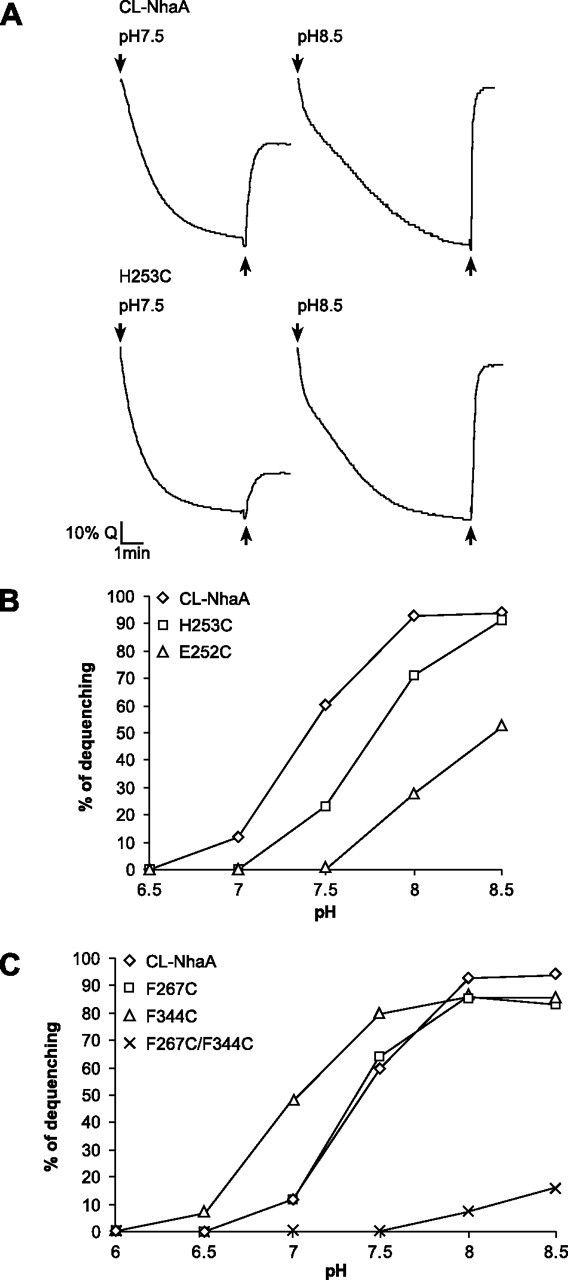

FIGURE 2.

Na+/H+ antiporter activity in everted membrane vesicles of NhaA mutants. Everted membrane vesicles were prepared from EP432 cells expressing the indicated NhaA mutants from pCL-HAH4 and grown in LBK (pH 7). The Na+/H+ antiporter activity was determined at the indicated pH values using acridine orange fluorescence to monitor ΔpH in the presence of 10 mm NaCl as described under “Experimental Procedures.” A, the data of typical experiments with CL-NhaA and mutant H253C are shown. At the onset of the reaction, ATP or d-lactate (2 mm) was added (↓), and the fluorescent quenching (Q) was recorded until a steady state level of ΔpH (100% quenching) was reached. NaCl (10 mm) was then added (↑), and the new steady state of fluorescence obtained (dequenching) after the addition was monitored. B, the percentage of dequenching as observed following the addition of 10 mm NaCl is shown versus pH. The results obtained with E252C (16) are also shown. C, experiments as in B with mutants F267C, F344C, and F267C/F344C. All experiments were repeated at least three times with practically identical results.

Previously we have defined two types of mutants of NhaA (34, 35). When measured at saturating concentrations of Na+, the first type of mutations have a pH dependence very similar to that of the wild type. In contrast, the second type of mutations demonstrate an abnormal pH dependence of the Na+/H+ exchange activity even at saturating concentrations of the ion. We therefore measured the effect of Na+ concentrations above saturation (up to 100 mm) on the maximal extent of dequenching of the mutants between pH 6.5 and 8.5. Mutants L255C, L264C, and F267C belong to the first type; their antiport activity in the presence of saturating Na+ concentration exhibited pH dependence similar to that of the wild type (data not shown). Remarkably all the other mutants belong to the second type; their pH profile of activity was consistently alkaline shifted by 0.5 pH unit even at saturating Na+ concentration (K242C, H243C, G244C, R245C, S246C, P247C, A248C, K249C, R250C, L251C, H253C, H256C, W258C, and L262C). Fig. 2B shows H253C as an example together with the pH profile of the activity of E252C, previously shown to be alkaline shifted by 1 pH unit (16). Hence in this screen, Cys replacements of many residues in the N-terminal half of TMS IX and the vicinal part of loop VIII–IX were found to affect the pH response of NhaA in line with the contention that this NhaA segment participates in the pH sensor.

Phe267 of TMS IX and Phe344 of TMS XI Are Important for the Na+/H+ Antiporter Activity—As discussed above, the crystal structure shows that TMS IX is in contact with the TMS IV/XI assembly, the core of the translocation machinery. The distance between (Cα) Leu264 (TMS IX) and Ala135 (TMS IVc) and Thr340 (TMS XIp) is 8.2 and 8.1 Å respectively; Phe267 contacts Phe344 of TMS XIp (Fig. 1 and Ref. 11). To study the role of these structural elements, we first constructed the single Cys replacement mutants L264C and F267C on the same face of TMS IX and L262C on the opposite face of helix IX (Fig. 1). As described above, the mutants were well expressed (Table 1 and Fig. 3C) and exhibited Na+/H+ antiporter activity with an apparent Km for Na+ very similar to that of the wild type (Table 1). The pH dependence of Na+/H+ exchange activity of these mutants was also very similar to that of the wild type (Fig. 2C and data not shown). Accordingly mutants L262C and L264C grew at rates similar to that of the wild type (Table 1). In contrast, mutant F267C had a most surprising growth phenotype; it grew similarly to the wild type at neutral pH but lost resistance to Na+ at alkaline pH (Table 1 and Fig. 3, compare A and B). These results raised the question as to why the Na+ resistance of mutant F267C was lost at alkaline pH.

FIGURE 3.

Growth curves of F267C, F344C, and F267C/F344C mutants in a Na+ selective medium at neutral pH and at alkaline pH and expression levels of the mutants. Shown are growth curves of EP432 cells expressing CL-NhaA and its mutants F267C, F344C, and F267C/F344C encoded from pCL-BstX in LB-based liquid medium containing 0.6 m NaCl at pH 7 (A) or pH 8.3 (B). C, Western blots of membranes (10 μg of protein) isolated from cells transformed with pBR322 (Lane a, negative control) or from cells expressing CL-NhaA (Lane b), F267C (Lane c), F344C (Lane d), or F267C/F344C (Lane e). The blots were analyzed using NhaA-specific monoclonal antibody 1F6 (30).

Notably the transmembrane pH difference is negligible in E. coli cells at alkaline pH (36). Therefore, whereas an electrogenic antiporter such as wild type NhaA, which moves a net positive charge during turnover (stoichiometry of 2 H+/1 Na+ (37)), can utilize the membrane potential to confer Na+ resistance, a less electrogenic antiporter such as NhaB (38) or electroneutral antiporters do not confer Na+ resistance at alkaline pH (1). We therefore considered the possibility that mutant F267C has a H+/Na+ stoichiometry different from that of wild type NhaA.

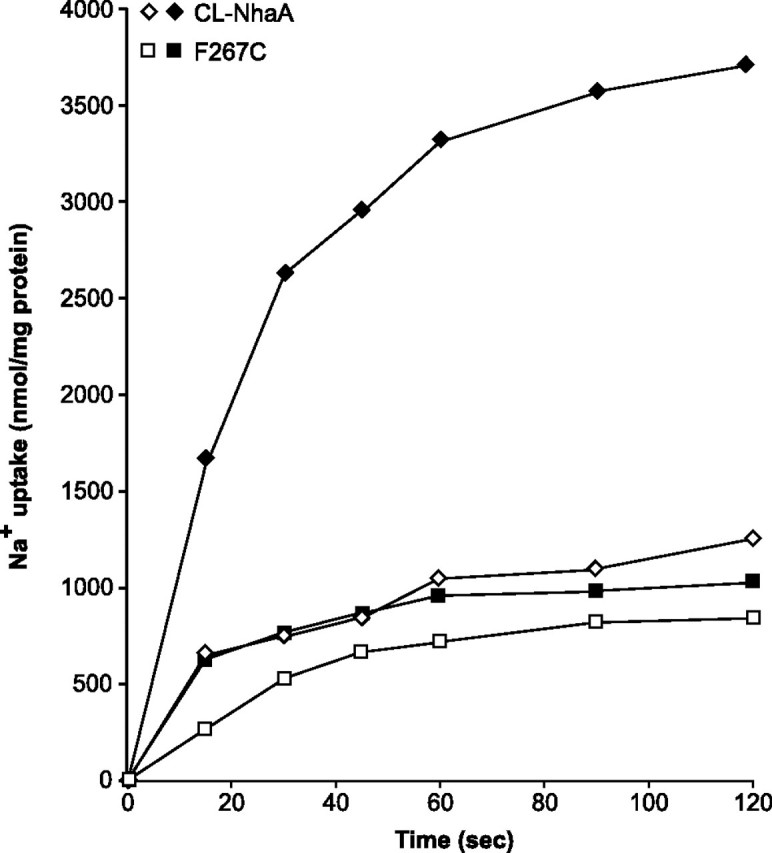

The activity of an electrogenic antiporter involves an electrophoretic movement of permeable ions (counterions) to compensate for charge translocation. Hence the presence of such counterions may determine the turnover rate of electrogenic transporters. K+ in the presence of the ionophore valinomycin has often been used as a counterion in reconstituted proteoliposomes. To test the effect of a counterion on the Na+ transport rate of mutant F267C, we measured ΔpH (acid inside)-driven uptake of 22Na+ into K+-loaded (10 mm) F267C proteoliposomes in the presence of 10 mm KCl with and without valinomycin. The results summarized in Fig. 4 show that in a reaction mixture containing K+ the initial rate of transport of the wild type was stimulated 4–5-fold by the presence, relative to the absence, of valinomycin. The respective steady state levels of antiport activity were 3700 nmol of Na+/mg of protein as compared with 800 nmol of Na+/mg of protein.

FIGURE 4.

The effect of counterion on 22Na transport by mutant F267C reconstituted into proteoliposomes. The affinity-purified proteins of CL-NhaA and F267C were reconstituted into proteoliposomes, and ΔpH-driven 22Na+ uptake was determined as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The reaction mixture (500 μl) contained 150 mm choline chloride, 10 mm Tris/Hepes (pH 8.6), 2 mm MgS04, 10 mm KCl, and 50 μm 22NaCl (1 μC/ml). Where indicated (filled symbols), valinomycin (5 μm) was added to the reaction mixture.

In marked contrast, valinomycin, in the presence of K+, stimulated much less the initial rate of antiport activity of mutant F267C, and the steady state level of transport reached in the presence or absence of the counterion was very low and similar (about 800 nmol of Na+/mg of protein; Fig. 4). It is thus suggested that the H+/Na+ stoichiometry of F267C is much lower than that of the wild type NhaA, explaining its lack of growth under the selective conditions at alkaline pH. Previously we have determined the stoichiometry (2 H+/1 Na+) of wild type NhaA (37). Unfortunately it was impossible to determine accurately the low H+/Na+ stoichiometry of mutant F267C because of the very low signal to noise ratio.

We next constructed the single mutant F344C and the double mutant F267C/F344C. These mutants were expressed at roughly 40% of the wild type level (Table 1 and Fig. 3C). When grown in liquid culture in the presence of high Na+, mutant F344C exhibited a growth phenotype very similar to that of the wild type both at neutral pH and at alkaline pH (Fig. 3, A and B). However, it produced smaller size colonies as compared with the wild type when grown on the agar selective medium at alkaline pH (Table 1). Whereas the apparent Km for Na+ of the antiporter activity of F344C was very similar to that of the wild type (Table 1), it showed an acidic shift of 0.5 pH unit in the pH dependence of the antiporter activity (Fig. 2C). This shift may account for the slower growth of the mutant on agar at alkaline pH (Table 1).

In marked contrast to the single mutants F267C and F344C that grew similarly to the control at neutral pH (Table 1 and Fig. 3A), the double mutant F267C/F344C did not grow on the high Na+ selective medium either at pH 7 or 8.3 (Fig. 3, A and B). Accordingly mutant F267C/F344C had no Na+/H+ antiporter activity up to pH 7.5 and had a marginal activity at alkaline pH in isolated membrane vesicles (Fig. 2C). Hence the double mutation and/or abrogation of the contact between TMSs IX and XI (mutant F267C/F344C) is more destructive to the Na+/H+ antiport activity than the effect of each separate mutant.

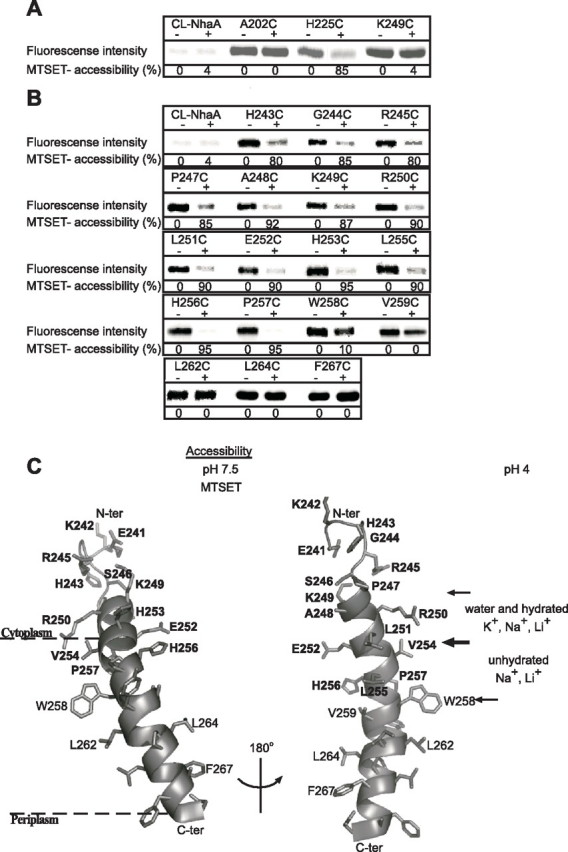

Accessibility to MTSET of the Cys Replacement Mutations— According to the crystal structure of the acid (pH 4)-down-regulated NhaA, the N-terminal half of TMS IX lines the cytoplasmic funnel of the antiporter (Fig. 1 and Ref. 11). Based on the dimensions of the funnel, the orifice is wide and accessible to water and hydrated Li+, Na+, and K+. Next the funnel narrows and extends to the middle of the membrane where it is potentially accessible only to non-hydrated Na+ and Li+ (11). Notably neither Na+ nor Li+ have been observed in the structure. Furthermore because the crystal structure of the active conformation(s) of NhaA at physiological pH has not yet been determined, the question as to which of the residues in TMS IX line the funnel in active NhaA has remained open.

It was therefore interesting to test whether the Cys replacements in TMS IX and the vicinal part of loop VIII–IX are freely accessible to MTSET, a membrane-impermeant water-soluble and positively charged SH reagent (39, 40). The dimensions of MTSET in the all-trans configuration are about 11.5 Å long and 6 Å wide. The width is similar to the diameter of hydrated Na+ (7.2 Å). The accessibility test was conducted at physiological pH when NhaA is active and from both the periplasmic and cytoplasmic sides of the membrane using intact cells and everted membrane vesicles, respectively (18).

Intact cells, which contain a plasmid encoding one of the Cys replacement mutations, were exposed to MTSET at pH 7.5 (Fig. 5A) and at pH 8.5 (data not shown). Then NhaA was affinity-purified on Ni2+-NTA beads and treated by fluorescein-5-maleimide to label any Cys left free following the MTSET treatment. The protein was resolved by SDS-PAGE, and the fluorescence intensity was determined and normalized to the amount of the protein on the gel. Accessibility to MTSET was estimated from the difference in the fluorescence intensity between untreated (100% fluorescence intensity = 0% modification by MTSET) and MTSET-treated cells. Mutants A202C, located in loop VI–VII facing the cytoplasm (Ref. 18 and Fig. 1), and H225C, located at the periplasmic end of TMS VIII facing the periplasm (Ref. 26 and Fig. 1), were used as cytoplasm-exposed and periplasm-exposed positive controls, respectively (Fig. 5A). A Cys-less NhaA served as a negative control (Fig. 5A). Similar to A202C (no accessibility) and in marked contrast to H225C (85% accessibility), all the Cys replacements were not exposed in intact cells implying that they are not accessible from the periplasm. Cys replacement K249C is shown as an example (Fig. 5A). Identical results were obtained when the accessibility test was conducted at pH 8.5.

FIGURE 5.

Accessibility of Cys replacements in loop VIII–IX and TMS IX to MTSET. Intact EP432 cells (A) expressing the various NhaA mutants from pCL-HAH4 and everted membrane vesicles isolated from them (B) were incubated with MTSET (+) or were untreated (-) as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Proteins were purified by Ni2+-NTA affinity chromatography and labeled on the beads with the fluorescent reagent fluorescein-5-maleimide to estimate the percentage of free cysteines left. Then the eluted proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and the fluorescence intensity on the gels was determined by a phosphorimaging system (Fuji Bas 1000). The same gels were also analyzed for the protein amounts using Coomassie Blue staining (not shown) and measuring the densities of the bands. The fluorescence intensities were normalized according to the amount of the proteins and expressed as a percentage of the untreated control (100%). Accessibility to MTSET = 100% - the percentage of fluorescein-5-maleimide labeling. CL-NhaA served as a negative control indicating the specificity of the reagents to SH groups. Several concentrations of the reagent were tested with similar results. The standard deviation was between 5 and 10%. C, a ribbon representation of TMS IX and the C-terminal part of loop VIII–IX. The single letter amino acid codes are used, and the location in the amino acid sequence is indicated by a number. Amino acid residues of which Cys replacements are accessible to MTSET at pH 7.5 are shown in white on black rectangles. Based on the crystal structure at pH 4 (11), the borders of the cytoplasmic funnel are depicted by thin arrows. The sections of the funnel above and below Glu252 (thick arrow) mark the orifice of the cytoplasmic funnel and the narrow passage into the middle of the membrane with their potential accessibility to ions at pH 4, respectively. The representation was generated using PyMOL. ter, terminus.

We next determined the accessibility of the Cys replacement mutations to MTSET in everted membrane vesicles at pH 7.5 (Fig. 5B) and at pH 8.5 (data not shown) with complementary results. The results summarized in Fig. 5, B and C, show that whereas W258C and all Cys replacements at its periplasmic side (V259C, L262C, L264C, and F267C) were not accessible to MTSET, all Cys replacement mutations located at its cytoplasmic side and in the vicinal part of loop VIII–IX were accessible to MTSET (80–95%) (Fig. 5, B and C, and data not shown). Hence at physiological pH, residues of TMS IX down to W258C are accessible to MTSET and therefore are suggested to line the cytoplasmic funnel in the active conformation of NhaA.

Amino Acid Residues Participating in the NhaA Dimer Interface— As revealed by cryoelectron microscopy of two-dimensional crystals (9, 10) and supported by genetic, biochemical (6), and biophysical data (7, 8), NhaA forms dimers in the membrane with a very short interface between the monomers. Recently by measuring the distance distribution between spin labels by pulsed electron paramagnetic resonance a structural model of the physiological NhaA dimer was obtained (8). It revealed two points of contact between the two NhaA monomers: one involving the β-hairpin at the periplasmic face of the membrane and the other at the cytoplasmic end of TMS IX, including Val254 and Trp258 at the cytoplasmic face of the membrane (8).

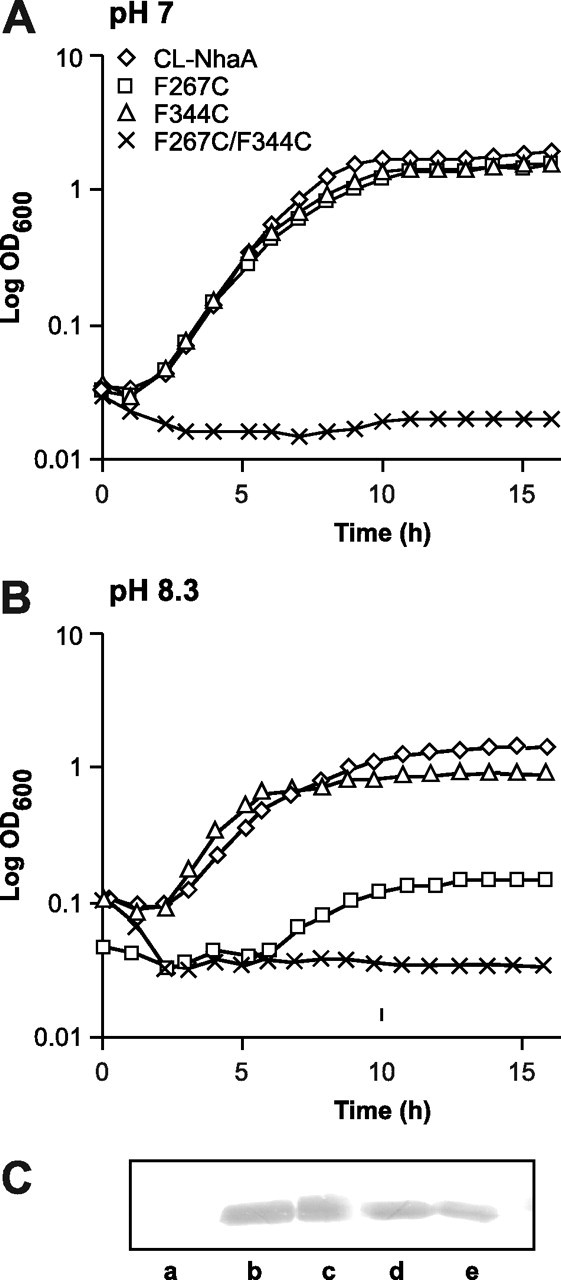

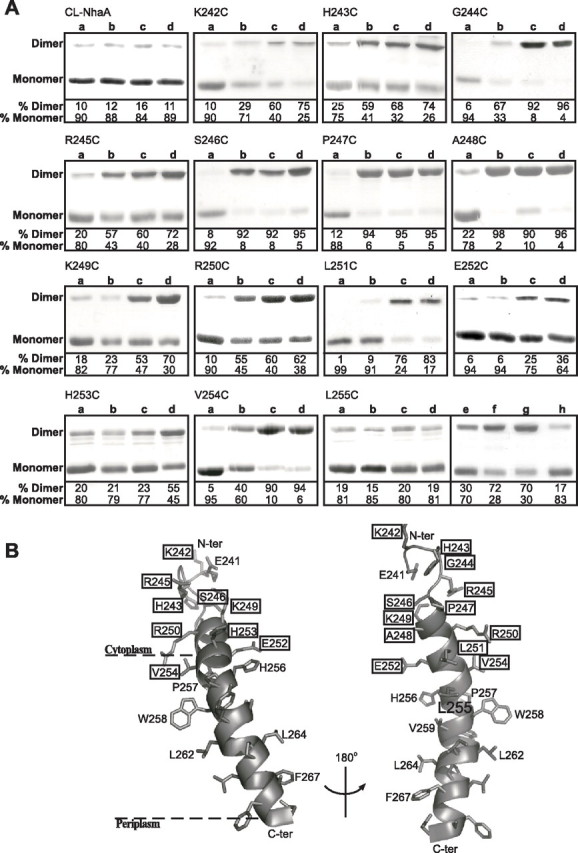

We assumed that in a symmetrical homodimer a Cys in a loop or a TMS that is located at or in close proximity to the NhaA dimer interface should be able to cross-link with its twin Cys in the other monomer. Using this approach, V254C in the N-terminal half of TMS IX but not E241C at the middle of loop VIII–IX was found previously at or close to the NhaA dimer interface (6). Therefore, we scanned all of the Cys replacements in TMS IX and loop VIII–IX for intermolecular cross-linking. For this purpose, membranes of the single Cys replacement mutants were exposed at pH 7.5 (Fig. 6A) and at pH 8.5 (data not shown) to homobifunctional, thiol-specific cross-linking reagents, o-PDM, p-PDM, and BMH, spanning different distances (∼10, 12, and 15 Å maximal distances, respectively (41)). The proteins were affinity-purified on Ni2+-NTA columns, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and Coomassie Blue-stained. Mutants that cross-linked had a gel mobility of dimers, whereas the non-cross-linked mutants appeared as monomers. Dimerization levels were estimated from the densities of bands (100% = the sum of both monomer and dimer band densities for each mutant). Untreated membranes served as a negative control to assess the level of spontaneous dimerization (Fig. 6A, Lanes a), which in most cases was very low (≤20%). Cys-less NhaA served as a negative control to verify the specificity of the cross-linking reagents to Cys residues; without Cys replacements CL-NhaA appears as a monomer in SDS-PAGE (Fig. 6A). Identical results were obtained when the cross-linking experiments were done at pH 8.5.

FIGURE 6.

Intermolecular cross-linking between NhaA monomers with a single Cys replacement. High pressure membrane vesicles were isolated from TA16 cells expressing the various NhaA mutants from pCL-HAH4. A, the membranes were untreated (Lanes a) or treated with the cross-linkers o-PDM (Lanes b), p-PDM (Lanes c), and BMH (Lanes d) as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Proteins were then purified, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and Coomassie Blue-stained, and the densities of the bands were determined. When intermolecular cross-linking takes place, a band, corresponding in mobility to that of the NhaA dimer, appears in SDS-PAGE. The extent of intermolecular cross-linking is expressed in percentage of dimers (100% = monomers + dimers). Panel L255C, Lanes a–d, as above; Lanes e–h, non-reducing conditions in the gel; Lane e, untreated; Lane f, diamide; Lanes g and h, MTS-2-MTS and o-PDM, respectively. Several concentrations of each reagent were tested with similar results. The standard deviation was between 5 and 10%. B, a ribbon representation of TMS IX and the proximal part of loop VIII–IX. The single letter amino acid codes are used, and the location in the amino acid sequence is indicated by a number. The various levels of cross-linking are depicted in rectangles of thin (partial cross-linking with BMH only), medium (partial cross-linking with two or all three reagents), and thick (efficient cross-linking with all three reagents) lines. The unique cross-linking behavior of Leu255 is represented in a filled black rectangle. The presentation was generated using PyMOL.

Negative results could be due to negative cross-linking or no accessibility to the cross-linking reagents. Therefore, we determined the accessibility of the mutants to the cross-linking reagents using fluorescein-5-maleimide to titrate the Cys left free following cross-linking (see above and Fig. 5). Between W258C and the cytoplasm, all Cys replacements showed very low fluorescein-5-maleimide fluorescence following treatment with the cross-linker reagents implying that these Cys replacements were accessible to all cross-linkers (data not shown). In contrast, W258C and the Cys replacements at its C-terminal side were not accessible to MTSET (Fig. 5) and accordingly were not accessible to the cross-linking reagents (data not shown).

The results summarized in Fig. 6, A and B, show that most Cys replacements located in the C-terminal half of loop VIII–IX and in the cytoplasmic end of TMS IX are significantly (3-fold above the background) intermolecularly cross-linked with at least one of the cross-linkers (H253C), two, and even all three (K242C–V254C). Remarkably a short segment at the cytoplasmic end of TMS IX (S246C, P247C, and A248C) cross-linked with all three reagents (12-, 8-, and 5-fold, respectively, above the background (Fig. 6, A and B)) and formed S–S bonds in the presence of diamide, an oxidizing agent (data not shown). Accordingly following cross-linking of these Cys replacements, a very low level (≤10%) of monomers was observed (Fig. 6A).

Cys replacement V254C was shown previously to form dimers in the presence of p-PDM and BMH (Ref. 6 and Fig. 6A). Most interestingly, L255C, the residue next to it, represents a unique spot of intermolecular cross-linking. Whereas it did not dimerize in the presence of o-PDM, p-PDM, and BMH (Fig. 6A, Panel L255C, Lanes b–d and h) it crossed-linked with a very short cross-linker, MTS-2-MTS, spanning 5.2 Å (Ref. 42 and Fig. 6A, Panel L255C, Lane g). Furthermore it showed an increase in spontaneous dimerization under non-reducing conditions as compared with reducing conditions (Fig. 6A, Panel L255C, compare Lane e with Lane a). The spontaneous cross-linking was inhibited by pretreatment of the membranes with o-PDM that does not cross-link but blocks the Cys residues (Fig. 6A, Panel L255C, compare Lanes h and e). These results suggest that L255C is able to form intermolecular cross-linking by S–S bonds. Indeed the presence of the oxidizing agent diamide increased the spontaneous cross-linking by at least 2-fold (Fig. 6A, Panel L255C, Lane f).

Because all the Cys replacements were active in Na+/H+ exchange, at least under the cross-linking conditions (Table 1), we can conclude that the cross-linking results reflect distances between monomers of native NhaA. The results presented here fully support the structural model of the NhaA dimer and show that in addition to the β-hairpin at the periplasmic side of NhaA a segment in TMS IX and loop VIII–IX contains amino acid residues that are located at or in proximity to the NhaA dimer interface.

Chemical Modification of L255C Causes an Alkaline Shift of the pH Dependence of the Na+/H+ Antiporter Activity and Increases the Apparent Km to Na+—We have shown previously that intermolecular cross-linking of V254C affects the pH response of NhaA (6). Therefore, we tested the effect of treatment of the isolated membrane vesicles by the cross-linkers on the Na+/H+ antiporter activity of each mutant. Except for L255C, no effect was observed (data not shown).

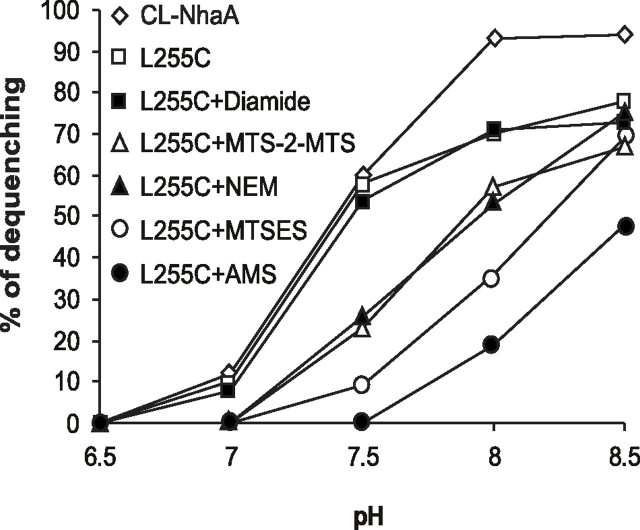

Untreated and the diamide-treated L255C membranes showed the same activity and pH profile as CL-NhaA (Fig. 7). On the other hand, treatment of L255C membranes by MTS-2-MTS caused an alkaline shift of about 0.5 pH unit in the pH dependence of the antiporter activity as compared with the wild type. We therefore next modified each of mutants S246C, P247C, A248C, and L255C that exhibit an efficient cross-linking in everted membrane vesicles by various SH reagents that differ in size and charge: NEM (molecular weight 125.1) that like MTS-2-MTS (molecular weight 250.36) is uncharged, negatively charged MTSES (molecular weight 242), positively charged MTSET (molecular weight 278.2), and uncharged AMS (molecular weight 536) (Fig. 7). The treated membranes were tested for the Na+/H+ antiporter activity. Cys replacements S246C, P247C, and A248C were not affected by any of the chemical modifications (data not shown). Remarkably all reagents modified the pH dependence of the activity of L255C; MTS-2-MTS and NEM had a similar effect, a shift of 0.5 pH unit (Fig. 7). Hence it is not the cross-linking itself that causes the pH shift. Both the positively charged MTSET (data not shown) and the negatively charged reagent MTSES (Fig. 7) shifted the pH profile of NhaA to the same degree, implying that the size rather than the charge causes the pH shift. Accordingly AMS, the largest and neutral reagent, caused the largest pH shift (more than 1 pH unit; Fig. 7). Whereas the wild type and the untreated L255C mutant exhibited the maximal activity at pH 8 (95 and 70% dequenching, respectively), the activity of the AMS-treated mutant reached 50% of the untreated L255C at pH 8.5.

FIGURE 7.

The Na+/H+ antiporter activity of mutant L255C is inhibited by SH reagents. Everted membrane vesicles were isolated from EP432 cells expressing CL-NhaA and its derived mutant L255C from pCL-HAH4. The membranes were untreated or treated with diamide, MTS-2-MTS (1 mm), NEM, MTSES, and AMS (1 mm each), washed, and tested for antiporter activity at various pH values as described in the legend to Fig. 2. Each experiment was repeated at least three times with essentially identical results.

The alkaline shifted pH dependence of the AMS treated mutant was not changed in the presence of 100 mm Na+, implying that the chemical modification changed the pH dependence of the antiporter. It was not possible to test the activity of the AMS-treated membranes at pH 9 because the respiration was inhibited. Therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility that this treatment in addition to the pH shift inhibited the extent of activity of NhaA.

The apparent Km of L255C for Na+ at pH 8.5 was similar to that of the wild type (Table 1; 0.8 mm). Treatment by MTSES or AMS increased the apparent Km for Na+ by 6-fold. The activity of the control, CL-NhaA, was not affected by the reagents (data not shown), indicating that the chemical modifications and their effects were specific to the Cys replacement of L255C. Our results show that chemical modification of L255C at the NhaA dimer interface dramatically affects the activity of NhaA and its pH regulation: the larger the chemical modifier (AMS), the greater the inhibitory effect on the Na+/H+ antiporter activity.

DISCUSSION

The three-dimensional crystal structure of the acidic pH-down-regulated NhaA has provided the basis for understanding the mechanism of Na+/H+ exchange and its unique regulation by pH (11). Furthermore it paved the way for structure-based studies aimed to answer questions that have remained open. These questions, in particular, are related to the open active conformation of NhaA because in contrast to the crystal structure obtained at pH 4 activation of NhaA occurs between pH 6.5 and 8.5 (1, 4). Here we focused on TMS IX and the neighboring part of loop VIII–IX and show that this NhaA segment plays a quadruple role in NhaA at physiological pH. It contains amino acid residues that (a) participate in the pH sensor, (b) affect the translocation machinery (TMS IV/XI assembly) and determine the H+/Na+ stoichiometry, (c) line the cytoplasmic funnel leading to the cation binding site, and (d) contribute to the NhaA dimer interface.

The pH Sensor—The crystal structure of NhaA identified a cluster of negatively charged residues in the orifice of the cytoplasmic funnel in the cytoplasmic end of TMS IV and the in-tandem part of loop VIII–IX most suitable to participate in the pH sensor of NhaA (11). Indeed at this location, a pH-induced conformational change was identified at Lys249 (25), and Cys replacements of a few amino acids were found to modify the pH response of NhaA. The most remarkable mutant found was E252C; it causes an alkaline shift of 1 pH unit in the pH dependence of NhaA and increases (by at least 10-fold) the apparent Km for Na+ of the antiporter, and Na+ and H+ increase its accessibility to 2-(4′-maleimidylanilino)naphthalene-6-sulphonic acid, a fluorescent probe.

Here we show that Cys replacements of potentially positively charged residues in this segment of NhaA (K242C, R245C, K249C, R250C, and H256C) caused an increase (4–10-fold) in the apparent Km to Na+ of the antiporter activity (Table 1). These Cys replacements and others in this area (H243C, G244C, S246C, P247C, A248C, L251C, H253C, W258C, and L262C) caused an equal alkaline shift (0.5 pH unit) in the pH response of NhaA (Fig. 2B). Remarkably computational analysis (multiconformation continuum electrostatics analysis (33)) showed that many of these residues form a cluster of strongly electrostatically interacting amino acid residues (His243, Lys249, Arg250, Glu252, His253, and His256), possibly explaining the uniform effect of their Cys replacements and other Cys replacements in their neighborhood on the pH dependence of NhaA. Our results support the contention that the cytoplasmic end of TMS IX and the vicinal part of loop VIII–IX participate in the pH sensor of NhaA at physiological pH. It is also remarkable that many mutations that affect the pH dependence also increase the apparent Km of the antiporter activity to the cations (16, 35).

Phe267 in TMS IX and Phe344 in TMS XI Are Essential for the Antiporter Activity and/or Its pH Regulation—The three-dimensional crystal structure shows that TMS IX, of which the cytoplasmic end harbors the pH sensor, is distorted, a feature that allows flexibility for a long range conformational change (11). In addition, close to its kink at the center of the membrane, TMS IX is in direct contact with the TMS IV/XI assembly (Fig. 1), a connection predicted to be essential for the Na+/H+ exchange machinery (11). Strikingly our results strongly support this structure-based prediction; each of the single mutants, F267C (on TMS IX) and F344C (on TMS XI), had an effect on the antiporter activity.

Mutant F344C caused an acidic shift in the pH profile of activity of NhaA (Fig. 2C). Interestingly other mutations in TMS XI were found to change the pH dependence of NhaA, G338S (32) and G345C (35).

Remarkably mutant F267C reduces the H+/Na+ stoichiometry of the antiporter exchange activity. This conclusion is based on the following results. (a) As measured by a fluorescent probe of ΔpH in everted membrane vesicles, the ΔpH-driven Na+ transport of the wild type and F267C were very similar and had identical pH dependence (Fig. 2C). Notably a counterion (150 mm Cl-) exists in this experimental system so that no ΔΨ exists across the membrane (43). (b) When the ΔpH-driven antiport activity was measured by 22Na uptake in proteoliposomes in the absence of a counterion, the activity of the electrogenic wild type NhaA, due to its stoichiometry of 2 H+/1 Na+, increased dramatically in the presence of a counterion (K+ in the presence of valinomycin); its rate and steady state level of Na+ uptake drastically increased (4–5-fold) (Fig. 4). In marked contrast, the Na+ uptake rate and the steady state level of transport of mutant F267C were only slightly affected by the presence of a counterion (Fig. 4), suggesting that the electrogenicity and thus the H+/Na+ stoichiometry of F267C is much lower than that of wild type NhaA.

The combination of alkaline pH and high Na+ is a very harmful stress condition for many bacterial cells that is overcome by NhaA (1). We have shown previously that the pH regulation of NhaA underpins its capacity in maintaining the homeostasis of cytoplasmic pH and Na+: activation at alkaline pH and down-regulation by acidic pH (1). The mutant F267C reveals yet another property of NhaA that is essential for its physiological importance in ions homeostasis: the high electrogenicity due to high H+/Na+ stoichiometry (2 H+/1 Na+). Because, at alkaline pH, mainly ΔΨ exists across E. coli membrane (1, 36), the wild type electrogenic antiporter with a H+/Na+ stoichiometry of 2 can utilize the ΔΨ and confer Na+ and H+ resistance. In marked contrast, an electroneutral antiporter or an antiporter with low H+/Na+ stoichiometry such as F267C cannot utilize ΔΨ and thus cannot confer resistance at alkaline pH in the presence of Na+ (Table 1, Fig. 3, and Refs. 1 and 13).

Whereas the single mutants, F267C and F344C, grew at neutral pH, even under selective conditions, the double mutant F267C/F344C did not grow in the Na+ selective media either at neutral pH or at alkaline pH and exhibited no/or marginal Na+/H+ antiporter activity in isolated everted membrane vesicles (Figs. 2C and 3). Although the double mutant was expressed in the membrane (Fig. 3C), we cannot exclude the possibility that the double mutation abrogates the structure. Nevertheless these results are in line with the crystal structure-based prediction that the connection and/or interaction between TMS IX and XI via Phe267 and Phe344 is most important for the antiporter activity.

Aromatic residues have been shown to mediate the self-assembly of different soluble proteins through π-π interaction (44, 45). Recently aromatic residues in TMSs of membrane protein have been shown to promote oligomerization (45). Here we show that Phe-Phe interaction between two TMSs (IX and XIp) within NhaA are crucial for the antiporter activity.

The Cytoplasmic Funnel at Physiological pH—The crystal structure of NhaA, obtained at pH 4, shows two funnels penetrating the molecule from both sides of the membrane, pointing to each other but separated by a hydrophobic barrier (11). The cytoplasmic funnel, the largest, is lined by four helices, II, IVc, V, and the N-terminal half of TMS IX (Fig. 1 and Ref. 11). Helices II, V, and IX (as well as XII) protrude from the membrane into the cytoplasm and create with their flexible loops a rough surface and a wide orifice of the funnel at the cytoplasmic side. At Glu252, about the membrane level, the funnel narrows and ends in the middle of the membrane at the putative ion binding site (Fig. 1 and Ref. 11). A computational accessibility analysis of the cavity of the cytoplasmic funnel for ions and water was conducted with the use of the respective ion radii as the probe size (3.58, 3.82, and 3.31 Å for hydrated Na+, Li+, and K+, respectively; 0.95 and 0.6 Å for non-hydrated Na+ and Li+, respectively; and 1.4 Å for water). This analysis suggested that whereas the wide orifice is accessible even to the hydrated cations the narrow passage to the middle of the membrane is potentially accessible only to non-hydrated Na+ and Li+ (11). As yet, neither Na+ nor Li+ have been observed in the structure. Furthermore the crystal structure of the active conformation(s) of NhaA at physiological pH (pH 6.5–8.5) has not yet been determined.

Here we addressed the question as to which of the Cys replacements in TMS IX and loop VIII–IX line the funnel at the physiological pH when NhaA is active. We tested the accessibility of the Cys replacements from both sides of the membrane to MTSET, a positively charged, membrane-impermeant reagent. The dimensions of MTSET are similar to those of hydrated Na+ (7.2-Å diameter). In addition to size, reactivity to MTSET may be affected by polarity, solvation, and the chemistry of the reactive group. Nevertheless our positive results reveal the following. (a) A cytoplasmic funnel exists at alkaline pH when NhaA is active just as it does at acidic pH when NhaA is inactive. Thus, many amino acid residues in TMS IX and loop VIII–IX are accessible to MTSET at the physiological pH from the cytoplasmic side but not from the periplasmic side of the membrane (Fig. 5). (b) At alkaline pH, the orifice of the funnel (above Glu252) is as wide as it is at acidic pH and readily accessible to MTSET (Fig. 5C). Note that at this segment amino acids residues on TMS IX and loop VIII–IX that do not face the funnel are also accessible to MTSET. These results are in line with the crystal structure showing that TMS IX protrudes from the membrane into the cytoplasmic space and therefore is accessible from the cytoplasmic side from all directions. It is also possible that the protruding segments are flexible. Indeed the cytoplasmic end of TMS IX undergoes a pH-dependent conformational change at alkaline pH (16, 25). (c) The narrow part of the funnel (below Glu252) is potentially accessible only to non-hydrated Na+ and Li+ in the acidic pH crystal structure. Yet at the physiological pH when NhaA is active, it is accessible at least to MTSET, which is larger than the naked cations. Thus, many Cys replacements down to W258C are MTSET-accessible (Fig. 5C). Assuming that the accessibility is via the cytoplasmic funnel, it is suggested that, at physiological pH, the cytoplasmic funnel between E252C and W258C widens. Notably our study was conducted on Cys replacement mutants that were normally expressed and exhibited antiport activity in the membrane. Therefore, the results reflect the wild type NhaA structure in the active conformation of NhaA. Furthermore our biochemical results are supported by a recent molecular dynamics simulation analysis predicting a drastic structural change at the bottom of the cytoplasmic funnel at alkaline pH (46).

The NhaA Dimer Interface at the Cytoplasmic End of Helix IX—The great similarity found between the three-dimensional crystal structure and the electron density map based on two-dimensional crystals, both obtained at pH 4, implied that the NhaA dimer interface is comprised of two principle sites of interaction between NhaA monomers (9, 12): the β-sheet in loop I–II at the periplasmic side and a few residues at the cytoplasmic end of TMS IX at the cytoplasmic side. Recent modeling of the NhaA dimer by measuring the distance distribution between spin labels by a pulsed electron paramagnetic resonance fully supported this contention (8).

In the present study scanning all Cys replacements in loop VIII–IX and TMS IX for intermolecular cross-linking, we revealed that single Cys replacements in the C terminus of loop VIII–IX and the cytoplasmic end of TMS IX cross-linked at least to a certain degree, implying a location at or very near the NhaA dimer interface. Furthermore our results show that there are two patterns of cross-linking. (a) The first pattern is an efficient intermolecular cross-linking with many reagents that is exemplified by Cys replacements S246C, P247C, and A248C, the extreme cases. They are cross-linked (92–98%) with all three cross-linkers (Fig. 6; o-PDM, p-PDM, and BMH, spanning ∼10–18 Å) and even can form S–S bonds. It is conceivable that Cys replacements that can accommodate several cross-linking reagents of different size are flexible and/or reside in a flexible site. Indeed S246C, P247C, and A248C are located at the junction between the cytoplasmic end of TMS IX and loop VIII–IX (Fig. 6B). All other Cys replacements with this pattern of cross-linking are located in part of TMS IX protruding out of the membrane or in loop VIII–IX (Fig. 6B). (b) The second pattern is intermolecular cross-linking only with the short reagent MTS-2-MTS (spanning 5 Å (42)) or forming S–S bonds as exemplified here with L255C (Fig. 6, A and B). This pattern implies a very rigid interface and a distance of around 5 Å between the monomers at this location. In line with this result, the ESR-based structural model of the NhaA dimer shows that V254C is located as predicted (6) in the NhaA dimer interface, and the distance between the twin V254C residues in the dimer is 8.1 Å between the sulfur atoms of the corresponding cysteines (8). We suggest that this second spot of intermolecular cross-linking is in a rigid dimer interface. The ESR-based model predicted additional restricted contacts between Tyr258 of TMS IX of one monomer and Arg204 and Leu210 of TMS VII in the other monomer. Unfortunately in line with our MTSET accessibility results (Fig. 5), we could not assay cross-linking of W258C and any other Cys replacements toward the C terminus of TMS IX because they were not accessible to the cross-linking reagents.

Notably as predicted by the ESR-based model of the NhaA dimer (8) the residues that cross-link efficiently cluster on one face of TMS IX (Fig. 1). This face of TMS IX, forming the dimer interface at the cytoplasmic side of the membrane, is directed away from the cytoplasmic funnel toward the other monomer exactly above the β-sheet, forming the interface at the periplasmic side of the membrane (8).

Chemical modification of all residues in the flexible segment of the dimer interface at helix IX and loop VIII–IX and the cross-linking itself had no effect on the antiporter activity. In contrast, at the rigid spot of L255C, chemical modification inhibited the activity of the antiporter in a reagent size-dependent fashion (Fig. 7). The cross-linking agent itself (diamide) had no effect. The negatively and positively charged reagents MTSES and MTSET had an identical effect implying that the type of charge is irrelevant. NEM and MTS-2-MTS shifted the pH dependence of the antiporter activity by 0.5 pH unit. MTSES and MTSET further increased the alkaline shift and to a similar degree, and the largest reagent, AMS, shifted the pH profile by 1 pH unit. Treatment by MTSES or AMS increased the apparent Km for Na+ of L255C by 6-fold. The pH dependence of V254C was shown previously to be affected by a rigid cross-linker but not by a flexible one (6). Taken together, these results highly suggest that the structure of the interface at the rigid point of the interface is crucial for the functionality of the antiporter.

It can be argued that NhaA is a functional dimer so that the integrity of the NhaA dimer is important for the activity of NhaA and/or its regulation by pH and that chemical modification at the NhaA dimer interface disturbs the native conformation of the dimer and causes the harmful defects of NhaA. However, recently by deleting the β-hairpin at the periplasmic side of NhaA we revealed that the functional unit of NhaA is a monomer (27). In addition, we found that AMS-modified L255C has a mobility of a dimer in a blue native gel (data not shown). We therefore suggest that abrogation of the rigid interface affects activity and regulation of the antiporter because of its location within a segment of NhaA that has multiple roles in addition to being part of the dimer interface: pH sensor, connection of TMS IX to the translocation machinery, and lining the cytoplasmic funnel.

This work was supported by United States-Israel Binational Science Foundation Grant 501/03-16.2 (to E. P.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: TMS, transmembrane segment; CL-NhaA, cysteineless NhaA; NEM, N-ethylmaleimide; BMH, 1,6-bismaleimidohexane; MTS-2-MTS, 1,2-ethanediyl bismethanethiosulfonate; MTSES, 2-sulfonatoethylmethanethiosulfonate; MTSET, [2-(trimethylammonium)ethyl]methanethiosulfonate bromide; AMS, 4-acetamido-4′-maleimidylstilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid, disodium salt; o-PDM, N,N′-o-phenylenedimaleimide; p-PDM, N,N′-p-phenylenedimaleimide; NTA, nitrilotriacetic acid; MOPS, 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid; L255C, NhaA Leu255 replaced with Cys (all other nhaA mutations are accordingly depicted).

References

- 1.Padan, E., Bibi, E., Masahiro, I., and Krulwich, T. A. (2005) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1717 67-88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brett, C. L., Donowitz, M., and Rao, R. (2005) Am. J. Physiol. 288 C223-C239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xiang, M., Feng, M., Muend, S., and Rao, R. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104 18677-18681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taglicht, D., Padan, E., and Schuldiner, S. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266 11289-11294 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Padan, E., Tzubery, T., Herz, K., Kozachkov, L., Rimon, A., and Galili, L. (2004) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1658 2-13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerchman, Y., Rimon, A., Venturi, M., and Padan, E. (2001) Biochemistry 40 3403-3412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hilger, D., Jung, H., Padan, E., Wegener, C., Vogel, K. P., Steinhoff, H. J., and Jeschke, G. (2005) Biophys. J. 89 1328-1338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hilger, D., Polyhach, Y., Padan, E., Jung, H., and Jeschke, G. (2007) Biophys. J. 93 3675-3683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams, K. A., Geldmacher-Kaufer, U., Padan, E., Schuldiner, S., and Kuhlbrandt, W. (1999) EMBO J. 18 3558-3563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams, K. A. (2000) Nature 403 112-115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hunte, C., Screpanti, M., Venturi, M., Rimon, A., Padan, E., and Michel, H. (2005) Nature 534 1197-1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Screpanti, E., Padan, E., Rimon, A., Michel, H., and Hunte, C. (2006) J. Mol. Biol. 362 192-202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pinner, E., Kotler, Y., Padan, E., and Schuldiner, S. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268 1729-1734 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Padan, E., Maisler, N., Taglicht, D., Karpel, R., and Schuldiner, S. (1989) J. Biol. Chem. 264 20297-20302 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis, B. D., and Mingioli, E. S. (1950) J. Bacteriol. 60 17-28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tzubery, T., Rimon, A., and Padan, E. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 3265-3272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kozachkov, L., Herz, K., and Padan, E. (2007) Biochemistry 46 2419-2430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rimon, A., Tzubery, T., Galili, L., and Padan, E. (2002) Biochemistry 41 14897-14905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ho, S. N., Hunt, H. D., Horton, R. M., Pullen, J. K., and Pease, L. R. (1989) Gene (Amst.) 77 51-59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fisher, C. L., and Pei, G. K. (1997) BioTechniques 23 570-571, 574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosen, B. P. (1986) Methods Enzymol. 125 328-336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldberg, E. B., Arbel, T., Chen, J., Karpel, R., Mackie, G. A., Schuldiner, S., and Padan, E. (1987) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 84 2615-2619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schuldiner, S., and Fishkes, H. (1978) Biochemistry 17 706-711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsuboi, Y., Inoue, H., Nakamura, N., and Kanazawa, H. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 21467-21473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gerchman, Y., Rimon, A., and Padan, E. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274 24617-24624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olami, Y., Rimon, A., Gerchman, Y., Rothman, A., and Padan, E. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272 1761-1768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rimon, A., Tzubery, T., and Padan, E. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 26810-26821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bradford, M. M. (1976) Anal. Biochem. 72 248-254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerchman, Y., Olami, Y., Rimon, A., Taglicht, D., Schuldiner, S., and Padan, E. (1993) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90 1212-1216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Padan, E., Venturi, M., Michel, H., and Hunte, C. (1998) FEBS Lett. 441 53-58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ninio, S., Elbaz, Y., and Schuldiner, S. (2004) FEBS Lett. 562 193-196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rimon, A., Gerchman, Y., Kariv, Z., and Padan, E. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273 26470-26476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olkhova, E., Hunte, C., Screpanti, E., Padan, E., and Michel, H. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103 2629-2634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Galili, L., Rothman, A., Kozachkov, L., Rimon, A., and Padan, E. (2002) Biochemistry 41 609-617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Galili, L., Herz, K., Dym, O., and Padan, E. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 23104-23113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Padan, E., Zilberstein, D., and Rottenberg, H. (1976) Eur. J. Biochem. 63 533-541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taglicht, D., Padan, E., and Schuldiner, S. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268 5382-5387 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pinner, E., Padan, E., and Schuldiner, S. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269 26274-26279 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Akabas, M. H., Staffer, D. A., Xu, M., and Karlin, A. (1992) Science 258 307-310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Akabas, M. H., Kaufmann, C., Archdeacon, P., and Karlin, A. (1994) Neuron 13 919-927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Green, N. S., Reisler, E., and Houk, K. N. (2001) Protein Sci. 10 1293-1304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Loo, T. W., and Clarke, D. M. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 36877-36880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dzioba-Winogrodzki, J., Winogrodzki, O., Krulwich, T. A., Boin, M. A., Hase, C. C., and Dibrov, P. (2008) J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol., in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.McGaughey, G. B., Gagne, M., and Rappe, A. K. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273 15458-15463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sal-Man, N., Gerber, D., Bloch, I., and Shai, Y. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 19753-19761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Olkhova, E., Padan, E., and Michel, H. (2007) Biophysics J. 92 3784-3791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]