Abstract

Introduction

A necrotic lung ball is a rare radiological feature that is sometimes seen in cases of pulmonary aspergillosis. This paper reports a rare occurrence of a necrotic lung ball in a young male caused by Candida and Streptococcus pneumoniae.

Case report

A 28-year-old male with pulmonary candidiasis was found to have a lung ball on computed tomography (CT) of the chest. The patient was treated with β-lactams and itraconazole and then fluconazole, which improved his condition (as found on a following chest CT scan) and serum β-D-glucan level. The necrotic lung ball was suspected to have been caused by coinfection with Candida and S. pneumoniae.

Conclusion

A necrotic lung ball can result from infection by Candida and/or S. pneumoniae, indicating that physicians should be aware that patients may still have a fungal infection of the lungs that could result in a lung ball, even when they do not have either Aspergillus antibodies or antigens.

Keywords: lung ball, necrotic lung ball, Candida, Streptococcus pneumoniae

Introduction

Most mycetomas, so-called aspergillomas, are due to Aspergillus species growing inside an existing cavity.1 Some pulmonary findings of mycetomas due to Candida have been reported.2–6 These pulmonary mycetomas are commonly referred to as “fungus balls.” Necrotic lung balls were first described by Przyjemski7 and are usually detected in patients with pulmonary aspergillosis. This paper reports a rare occurrence of a necrotic lung ball caused by candidiasis and co-infection by Streptococcus pneumoniae and the identification of the lung ball by computed tomography (CT) of the chest, which demonstrated unique features in the clinical course of the patient.

Case report

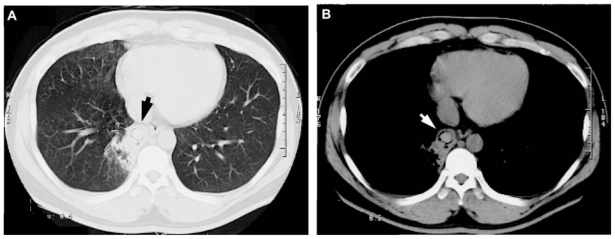

A 28-year-old male with a cough and hemoptysis who had developed pulmonary infiltration according to chest radiography and CT was transferred to the authors’ hospital. The illness began with coughing and hemoptysis in October 2009. In November, he experienced an increase in hemoptysis. Radiography and CT findings showed a mass mimicking an aspergilloma fungus ball shadow in the right lower lung field (Figure 1, Figure 2A, and B). He was found to be in an alerted state of consciousness and have a temperature of 37.1°C. Mild obesity (body mass index of 31.1 kg/m2) was noted. No rales were evident on auscultation of both lungs.

Figure 1.

A chest radiograph revealed infiltration in the lower lobe of right lung.

Figure 2.

Chest computed tomography ([A] chest lung image, [B] chest tissue image) showing infiltration and a lung ball shadow (arrow) in the right lower lung field.

The patient’s laboratory findings included a red blood cell count of 534 × 104/μL; hemoglobin, 16.9 g/dL; hematocrit, 47.5%; white blood cell count, 8000/μL (neutrophils, 64.8%; lymphocytes, 28.1%; monocytes, 4.8%; eosinophils, 2.0%; basophils, 0.3%); platelet count, 20.9 × 104/μL; aspartate aminotransferase, 36 IU/L; alanine aminotransferase, 101 IU/L; lactate dehydrogenase, 191 IU/L; alkaline phosphatase, 263 U/L; glucose, 132 mg/dL; Glycated hemoglobin, 5.9% (normal 4.3%–5.8%); C-reactive protein, 0.13 mg/dL; erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 13 mm/1 hour; and serum β-D-glucan 11.4 pg/mL (normal <11.0 pg/mL). The patient was negative for human immunodeficiency virus antibodies. There was a very low titer of Aspergillus antigen in his blood sample (1.1; cut-off index 1.0), and his blood was negative for Aspergillus antibodies. No Candida antigens were detected in the patient’s blood. The 75 g oral glucose tolerance test revealed that the patient had mild diabetes mellitus (pretest, 101 mg/dL; 30 minutes, 214 mg/dL; 60 minutes, 258 mg/dL; 90 minutes 263 mg/dL; 120 minutes, 260 mg/dL). A chest radiograph revealed infiltration in the lower lobe of right lung (Figure 1). This was confirmed by CT of the chest (Figure 2). Candida albicans and mucoid type S. pneumoniae were detected repeatedly from sputum. Several Candida species other than C. albicans, Candida krusei, and Candida glabrata were also detected. No acid-fast bacilli were recovered by smears, polymerase chain reaction, or from culture. Bronchial brush cytology of the part of the shadow visible on the CT scan by bronchofiberscopy detected yeast, as did bronchial wash cytology of the same region. A culture of the bronchial fluid detected the mucoid type of S. pneumoniae. The patient was diagnosed with pulmonary candidiasis and co-infection by S. pneumoniae.

Clinical course

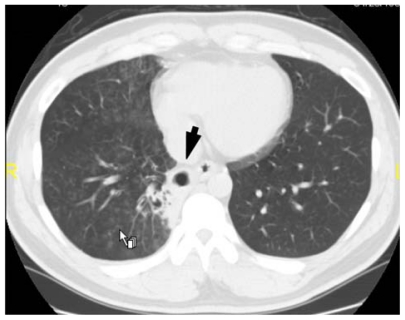

The patient was treated on an outpatient basis with ceftriaxone 2 g/day for 1 day following oral cefditoren 600 mg/day for 7 days. Thirteen days after the initial CT examination, the lung ball shadow on the chest CT was found to have disappeared (Figure 3). After bronchofiberscopy and serum tests for fungal infection, itraconazole (ITCZ) (200 mg/day) was administered. The patient’s symptoms were found to have improved, and ITCZ administration was thus continued. Gradually, his condition and chest imaging results improved. However, the patient’s serum β-D-glucan level still remained elevated. Four months later, he developed a recurrence of the pulmonary infiltration, and a high level of serum β-D-glucan was noted (peak, 33.3 pg/mL). ITCZ was re-administrated and his clinical symptoms and imaging findings on chest CT were found improved, but the improvement was still considered to be unsatisfactory. ITCZ was taken for 3 months. Aspergillus infection had been almost ruled out by this stage. The patient was therefore switched to fluconazole (200 mg/day) for a month. Thereafter, radiological findings improved and blood β-D-glucan levels also decreased to within the normal range (6.1 pg/mL).

Figure 3.

Chest computed tomography taken 13 days after presentation showing the disappearance of the lung ball (arrow) and the presence of a cavitary lesion in the right lower lung field.

Discussion

Most mycetomas are due to Aspergillus species. Some pulmonary findings of mycetomas due to Candida have been reported. Necrotic lung balls are also usually detected in patients with pulmonary aspergillosis and they are distinct from aspergillomas with regard to their pathological features. An aspergilloma is a fungus ball component with only an aspergillus body. In contrast, a lung ball is composed of necrotic lung tissue. Almost all previous reports describing either lung balls or necrotic lung balls were seen in patients with pulmonary aspergillosis.8,9 One rare case of a lung ball caused by Penicillium has also been reported.10 However, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, there have been no previous reports of lung balls caused by candidiasis. Pulmonary candidiasis is difficult to diagnose, because Candida species are so prevalent in the environment and within the human body. In fact, if Candida species are detected from a respiratory sample, it may actually be contamination by Candida from the oral cavity. Furthermore, there are no specific radiological features in pulmonary candidiasis. In the present case, bronchial brush cytology of a specimen obtained from the shadow area on CT scan by bronchofiberscopy revealed yeast, and bronchial wash cytology of the same region also revealed yeast. This means that Candida definitely existed. S. pneumoniae was also detected from the bronchial wash and sputum, in addition to the Candida species, and it was of the mucoid type, which is known to generally cause pneumonia. In this case, the necrotic lung ball may have been caused by S. pneumoniae. However, there was a high level of serum β-Dglucan, thus suggesting the existence of deep fungal infection. In addition, the patient’s blood was negative for Aspergillus antibodies, and had a very low titer of Aspergillus antigen, which indicated that the patient did not have aspergillosis. Therefore, it is suspected that this case of a necrotic lung ball was caused by a Candida infection or co-infection with Candida and S. pneumoniae.

CT is able to accurately identify and depict the features of necrotic lung balls. In this case, the CT scan of the chest, at first, showed a lung ball shadow and the lesion disappeared after treatment with ITCZ. A cavitary lesion was then present instead of a round density (Figure 3). The lung ball lesion was dissolved in a short period. As a result, this suggests that the ball shadow was necrosis of the lung, which is intriguing because the patient was young and not severely immunocompromised. The reason why a necrotic lung ball formed may be due to the fact that the patient had diabetes but not undiagnosed.

It was therefore concluded that S. pneumoniae had a relatively large effect on the immune response. According to the authors’ review of the pertinent literature, S. pneumoniae is seldom considered to be an etiologic pathogen of lung abscess, pulmonary gangrene, or necrotizing or cavitative pneumonia.11 However, some reports indicate that these pulmonary diseases occur due to S. pneumoniae.12 Mucoid type S. pneumoniae is considered especially virulent and to be one cause of lung abscess or purulent diseases. The authors could find no previous report describing a necrotic lung ball caused by S. pneumoniae; the present case therefore provides new information regarding the etiology of lung ball formation. It is now evident that a necrotic lung ball may result from infection by Candida and/or S. pneumoniae, thus indicating that physicians should be aware that patients may still have a fungal infection of the lungs, even when they do not have either Aspergillus antibodies or antigens, that may result in a lung ball.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors disclose no conflicts of interest in relation to this work.

References

- 1.Kibbler CC, Milkins SR, Bhamra A, Spiteri MA, Noone P, Prentice HG. Apparent pulmonary mycetoma following invasive aspergillosis in neutropenic patients. Thorax. 1988;43(2):108–112. doi: 10.1136/thx.43.2.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watanakunakorn C. Acute pulmonary mycetoma due to Candida albicans with complete resolution. J Infect Dis. 1983;148(6):1131. doi: 10.1093/infdis/148.6.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prats E, Sans J, Valldeperas J, Ferrer JE, Manresa F. Pulmonary mycetoma-like lesion caused by Candida tropicalis. Respir Med. 1995;89(4):303–304. doi: 10.1016/0954-6111(95)90092-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shelly MA, Poe RH, Kapner LB. Pulmonary mycetoma due to Candida albicans: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22(1):133–135. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abel AT, Parwer S, Sanyal SC. Pulmonary mycetoma probably due to Candida albicans with complete resolution. Respir Med. 1998;92(8):1079–1080. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(98)90359-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bachh AA, Haq I, Gupta R, Varudkar H, Ram MB. Pulmonary candidiasis presenting as mycetoma. Lung India. 2008;25(4):165–167. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.45285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Przyjemski C, Mattii R. The formation of pulmonary mycetomata. Cancer. 1980;46(7):1701–1704. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19801001)46:7<1701::aid-cncr2820460733>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glimp RA, Bayer AS. Pulmonary aspergilloma. Diagnostic and therapeutic considerations. Arch Intern Med. 1983;143(2):303–308. doi: 10.1001/archinte.143.2.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aquino SL, Kee ST, Warnock ML, Gamsu G. Pulmonary aspergillosis: imaging findings with pathologic correlation. Am J Roentgenol. 1994;163(4):811–815. doi: 10.2214/ajr.163.4.8092014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de la Cámara R, Pinilla I, Muñoz E, Buendía B, Steegmann JL, Fernández-Rañada JM. Penicillium brevicompactum as the cause of a necrotic lung ball in an allogeneic bone marrow transplant recipient. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1996;18(6):1189–1193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fraser RS, Müller NL, Colman N, Paré PD. Diagnosis of Diseases of the Chest. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1999. Bacteria other than Mycobacteria. Streptococcus pneumoniae; pp. 736–742. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yangco BG, Deresinski SC. Necrotizing or cavitating pneumonia due to Streptococcus Pneumoniae: report of four cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1980;59(6):449–457. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198011000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]