Abstract

Sodium channel Nav1.7 has recently elicited considerable interest as a key contributor to human pain. Gain-of-function mutations of Nav1.7 produce painful disorders, whereas loss-of-function Nav1.7 mutations produce insensitivity to pain. The inherited erythromelalgia Nav1.7/F1449V mutation, within the C terminus of domain III/transmembrane helix S6, shifts channel activation by -7.2 mV and accelerates time to peak, leading to nociceptor hyperexcitability. We constructed a homology model of Nav1.7, based on the KcsA potassium channel crystal structure, which identifies four phylogenetically conserved aromatic residues that correspond to DIII/F1449 at the C-terminal end of each of the four S6 helices. The model predicted that changes in side-chain size of residue 1449 alter the pore's cytoplasmic aperture diameter and reshape inter-domain contact surfaces that contribute to closed state stabilization. To test this hypothesis, we compared activation of wild-type and mutant Nav1.7 channels F1449V/L/Y/W by whole cell patch clamp analysis. All but the F1449V mutation conserve the voltage dependence of activation. Compared with wild type, time to peak was shorter in F1449V, similar in F1449L, but longer for F1449Y and F1449W, suggesting that a bulky, hydrophobic residue is necessary for normal activation. We also substituted the corresponding aromatic residue of S6 in each domain individually with valine, to mimic the naturally occurring Nav1.7 mutation. We show that DII/F960V and DIII/F1449V, but not DI/Y405V or DIV/F1752V, regulate Nav1.7 activation, consistent with well established conformational changes in DII and DIII. We propose that the four aromatic residues contribute to the gate at the cytoplasmic pore aperture, and that their ring side chains form a hydrophobic plug which stabilizes the closed state of Nav1.7.

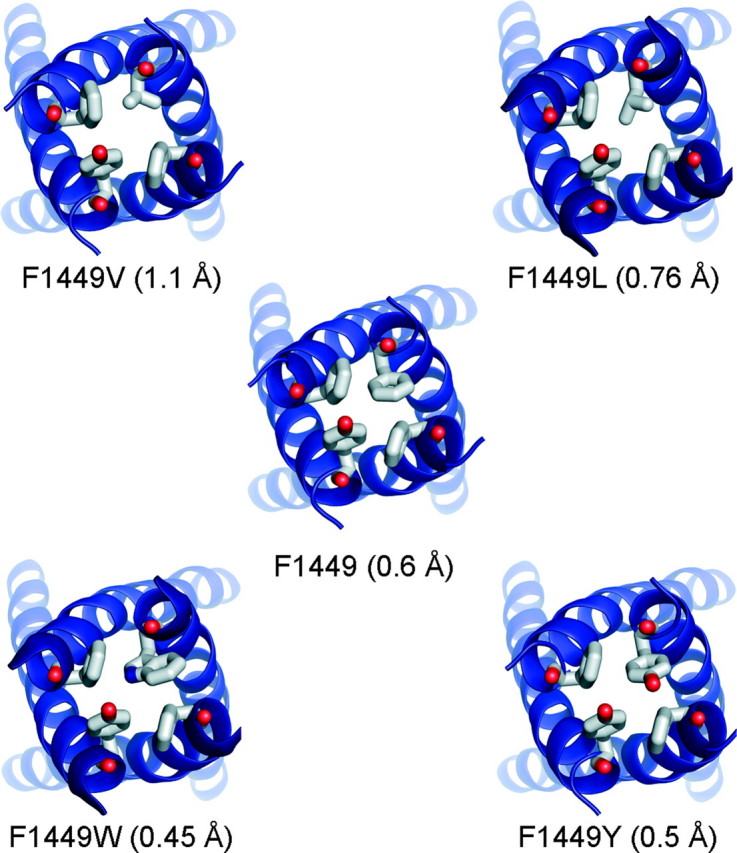

Neuropathic pain is a common disorder, often refractory to existing treatments, linked to hyperexcitability of dorsal root ganglion (DRG)5 neurons (1-3). Dysregulated expression of sodium channels contributes to neuropathic pain (4), and some nonspecific sodium channel blockers provide relief, albeit usually partial, for neuropathic pain (5). A direct link of specific sodium channel isoform and neuropathic pain has recently been established in humans by the discovery of mutations in SCN9A, the gene that encodes Nav1.7, a sodium channel preferentially expressed in DRG neurons (6). Gain-of-function mutations in Nav1.7 have been identified in patients with inherited erythromelalgia (IEM, also called erythermalgia), a disorder characterized by severe burning pain in the distal extremities in response to warmth (6), and paroxysmal extreme pain disorder, in which patients experience perirectal and periorbital pain (7); loss-of-function mutations in Nav1.7 have also been found in patients displaying congenital insensitivity to pain (8-10). All of the IEM mutations studied to date lower the threshold for Nav1.7 activation, whereas less than half show impaired steady-state fast inactivation (11-17). The effect on electrogenesis has been examined in transfected DRG neurons for three of these mutations (L858H, A863P, and F1449V), which have been shown to lower the threshold for single action potentials and increase the frequency of action potential firing in DRG neurons in response to graded stimuli (13, 15, 18).

Most IEM mutations in Nav1.7 are clustered in transmembrane segments (S1, S4, S5, and S6) and linkers joining S4 and S5 of domains I (DI) and DII (6, 19). However, the F1449V mutation, which causes inherited erythromelalgia in the largest family studied to date, is located more distally at the cytoplasmic end of the S6 segment of DIII and the juncture with L3, the cytosolic loop which joins DIII and DIV (13). Because L3 carries the peptide motif IFM, which functions as the fast inactivation gate of sodium channels (20), it is not surprising that the F1449V Nav1.7 mutation affects steady state fast inactivation (13). In contrast, the basis of the F1449V effect on channel activation is not obvious. We therefore constructed a homology model of Nav1.7, to test possible structural features that might underlie the altered channel activation. Here we show that phylogenetically conserved aromatic residues, located at equivalent positions in each S6 helix relative to the conserved “gating-hinge” glycine (or serine in DIV/S6) residue, contribute to the putative cytoplasmic activation gate of Nav1.7, possibly by forming a hydrophobic plug, which stabilizes the closed state of the channel. Our results also show that substitution of DIII/F1449 with bulky hydrophobic residues does not alter the voltage dependence of activation. Compared with wild-type Nav1.7, however, time to peak was shorter in F1449V, similar in F1449L, but longer for F1449Y and F1449W. The DIII/F1449V and DII/F960V mutations destabilize the closed state of the channel, consistent with channel activation being initiated by conformational changes in DII and DIII. These findings identify a conserved hydrophobic motif at the cytoplasmic aperture of Nav1.7 and provide a mechanistic basis for the decreased threshold for activation by the IEM mutation DIII/F1449V.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Computational Modeling of Nav1.7—A homology model of the closed-state pore domain of Nav1.7 was generated using the crystal structure of the KcsA potassium channel (PDB code 1BL8) (21) as the structural template. KcsA was chosen over the structure of Kv2.1, because the latter channel was crystallized in the open state (22). KcsA was also chosen over the closed-state KirBac1.1 (23) and KirBac3.1 channel structures, because more extensive experimental studies have been carried with KcsA to investigate the structural basis of pore gating. Moreover, although differences in prokaryotic and eukaryotic bilayer thickness and the presence of the S1-S4 voltage sensor may alter pore structure, numerous studies have used an homology model generated from the open-state MthK channel (e.g. Cronin et al. (24)), and KcsA is the more common template for homology modeling studies of closed state eukaryotic sodium (25, 26), potassium (27, 28), and calcium (29, 30) channel pores, demonstrating the suitability of potassium channels as structural templates for homology modeling.

The Nav1.7 sequence (Swiss-Prot accession Q15858) was aligned with the KcsA channel sequence (Swiss-Prot accession P0A334) using ClustalW (31). The outer helices (PDB file residues 23-48), pore-pointing helices (residues 63-74), and pore-lining inner helices (residues 88-117) of KcsA provided the coordinates for modeling the equivalent sequences in each of the four domains in the Nav1.7 model: S5 (Swiss-Prot sequence residues DI:239-264, DII:860-885, DIII:1315-1340, and DIV: 1638-1663), pore-pointing helices (residues DI:348-359, DII: 914-925, DIII:1393-1404, and DIV:1685-1696), and pore-lining S6 helices (residues DI:378-407, DII:944-973, DIII:1433-1462, and DIV:1736-1765) (Fig. 1). Aromatic residues (phenylalanine or tyrosine) are present at the C terminus of the four S6 helices at equivalent positions relative to the conserved glycine gating-hinge residues (or the corresponding serine residue in DIV/S6).

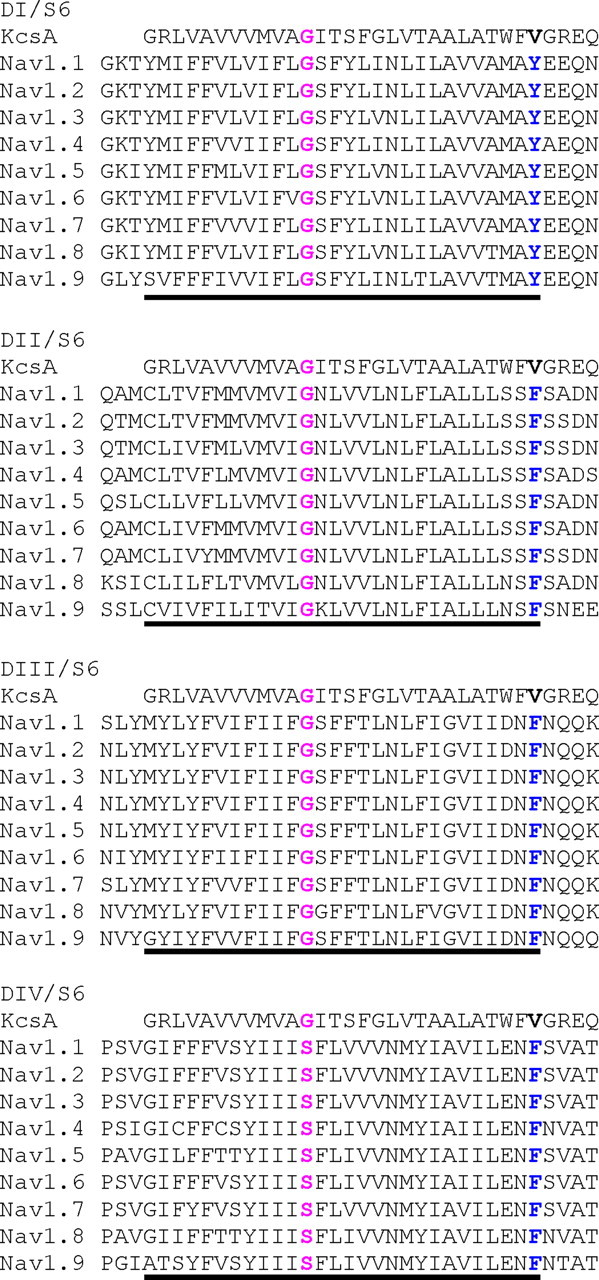

FIGURE 1.

Alignment of the S6 transmembrane segments from the four homologous domains of human voltage-gated sodium channels with the pore-lining transmembrane 2 sequence of the bacterial KcsA potassium channel. The conserved gating-hinge glycine residue in the middle of S6 is in boldface and red; serine is present at the equivalent position in DIV/S6. The C-terminal residue in each of the S6 segments is a highly conserved aromatic residue: tyrosine in DI and phenylalanine in the other domains are depicted in boldface and blue. The putative S6 helices are underlined.

Residues of the KcsA structure were mutated to the Nav1.7 sequence using the Biopolymer module of SYBYL (version 7.0, Tripos Inc., St. Louis, MO). Additional mutations were introduced to generate the F1449V, F1449L, F1449Y, and F1449W mutant Nav1.7 models. Both the wild-type and mutant models were subjected to 500 rounds of conjugate-gradient minimization in SYBYL using the Tripos force-field (32). The pore diameters of the channel models were calculated using the program HOLE (33). The figures were produced using the PyMOL molecular graphics system (DeLano Scientific, San Carlos, CA).

Plasmids and HEK 293 Cell Transfections—The plasmid carrying the TTX-resistant (TTX-R) version of human Nav1.7 cDNA (hNav1.7R) (34) and the DIII/F1449V mutant derivative (13) were previously described. The DIII/F1449L, DIII/F1449Y, DIII/F1449W, DI/Y405V, DII/F960V, and DIV/F1752V mutants and the double mutant F960V/F1449V were introduced into hNav1.7R using the QuikChange XL site-directed mutagenesis reagents (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Human embryonic kidney cells (HEK 293) were transfected with each individual mutant channel construct using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the procedures recommended by the manufacturer. Transfected HEK 293 cells were grown under standard culture conditions (5% CO2, 37 °C) in 50% Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium 50% F-12 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. We have previously shown that gating properties of Nav1.7R in transfected HEK 293 cells are similar to those of Nav1.7R in native DRG neurons (34).

Electrophysiology—Whole cell voltage clamp recordings (35) of HEK 293 cells transiently transfected with the sodium channels Nav1.7R, DI/Y405V, DII/F960V, DIII/F1449V, DIII/F1449L, DIII/F1449Y, DIII/F1449W, DIV/F1752V, or F960V/F1449V double mutant derivatives were performed with an EPC-9 amplifier (HEKA Electronics, Lambrecht/Pfalz, Germany) using fire-polished 0.5- to 1.5-MΩ electrodes (World Precision Instruments, Inc., Sarasota, FL). The pipette solution contained (in mm): 140 CsF, 10 NaCl, 1 EGTA, and 10 HEPES; 302 mosmol (pH 7.4, adjusted with CsOH), and the extracellular bath contained (in mm): 140 NaCl, 3 KCl, 10 glucose, 10 HEPES, 1 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 0.0003 TTX; 310 mosmol (pH 7.4, adjusted with NaOH). TTX was added to the bath solution to block all endogenous voltage-gated sodium currents that might be present in HEK 293 cells (36) and thereby permitted study of Nav1.7R in isolation. All recordings were conducted at room temperature (∼21 °C). The pipette potential was adjusted to zero before seal formation, and the voltages were not corrected for liquid junction potential. Capacity transients were cancelled, and series resistance was compensated at 10 μsby 65-95%. Leakage current was subtracted digitally online using hyperpolarizing potentials applied after the test pulse (P/4 procedure). Currents were acquired using Pulse software (HEKA electronics, Lambrecht/Pfalz, Germany), filtered at 10 kHz and sampled at a rate of 100 kHz.

Voltage protocols were carried out at a predetermined time after

establishing cell access. Standard current-voltage (I-V) families were

obtained using 40-ms pulses from a holding potential of -120 mV to a range of

potentials (-100 to +60 mV) in 5-mV steps with 5 s between pulses. The peak

value at each potential was plotted to form I-V curves. Activation curves were

obtained by calculating the conductance G at each voltage

V,

with Vrev being the reversal potential, determined for

each cell individually. Activation curves were fitted with the following

Boltzmann distribution

equation,

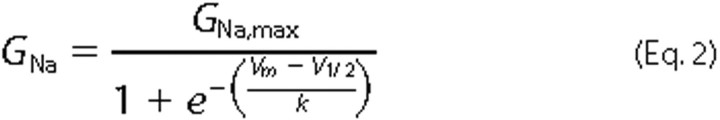

where GNa is the voltage-dependent sodium conductance, GNa,max is the maximal sodium conductance, V½ is the potential at which activation is half-maximal, Vm is the membrane potential, and k is the slope factor.

Protocols for assessing steady-state fast-inactivation consisted of a

series of pre-pulses from -130 to -10 mV, each lasting 500 ms from a holding

potential of -100 mV, followed by a 40-ms depolarization to -10 mV to measure

the non-inactivated transient current. The normalized curves were fitted using

a Boltzmann distribution

equation,

where INa,max is the peak sodium current elicited after the most hyperpolarized pre-pulse, Vm is the preconditioning pulse potential, V½ is the half-maximal sodium current, and k is the slope factor.

Analysis of variance tests were carried out using Prism version 4.0 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Statistical significance (p < 0.05) was tested using a two-sided Dunnett's multiple comparison test as post-hoc analysis. All data are compared with WT and presented as mean ± S.E.

RESULTS

Homology Model of Nav1.7 Pore—The crystal structures of potassium channels have been used as structural templates to generate homology models of human sodium channels (26, 37). In this study the crystal structure of the bacterial potassium channel KcsA, which has been the subject of molecular dynamics simulations (e.g. Holyoake et al. (38)) and direct observation (39) to elucidate the structural basis of pore gating, has provided the structural template for homology modeling of the Nav1.7 pore in a closed conformation. Fig. 1 shows the alignment of the S6 transmembrane segments in each of the four domains of Nav1.7 with the corresponding pore-lining helix from KcsA. The assignment of the C-terminal end of S6 of KcsA and the corresponding coordinates in Nav1.7 in our studies include the terminal tripeptide WFV representing the last helical turn of the inner helix of KcsA (21), which was missing in previously reported sodium channel models (25, 26). Sequence alignment of the nine human sodium channels shows that there are gating-hinge glycine residues in S6 in domains I-III (a serine residue is present in DIV/S6) at positions equivalent to those in the bacterial channels and that the terminal residue in each of the aligned S6 helices is an aromatic amino acid, either tyrosine in domain I (DI) or phenylalanine in the other three domains (Fig. 1).

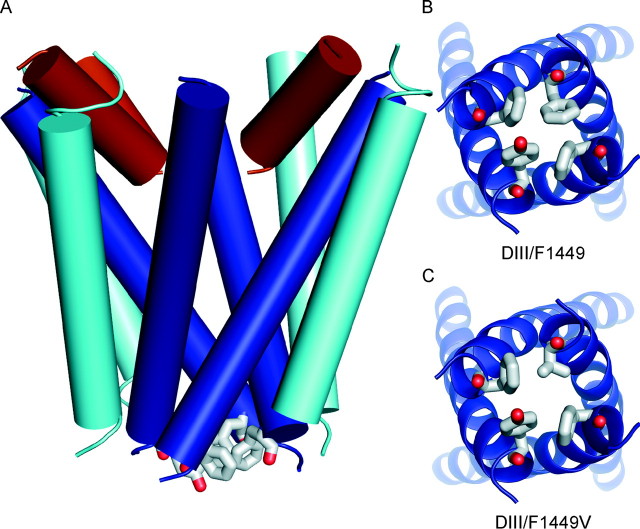

The wild-type Nav1.7 homology model shows that the side chain of the aromatic residue at the cytoplasmic end of S6 in each of the four domains (DI/Y405, DII/F960, DIII/F1449, and DIV/F1752) contribute to a potential pore-obstructing hydrophobic gate (Fig. 2A). A similar hydrophobic gate has been suggested for the acetylcholine receptor (40-42) and has been identified in the bacterial potassium channel KirBac1.1 (23). The model suggests that the four aromatic residues share a similar environment in Nav1.7 closed state. Thus, we expected that mutation to the small residue valine (Fig. 2, B and C) might destabilize the hydrophobic cluster in the closed-state conformation of the Nav1.7 pore, permitting the channel to open at more hyperpolarized potentials as has been observed in patch clamp studies (13).

FIGURE 2.

A, model of the wild-type Nav1.7 channel viewed parallel to the membrane plane. S5, P-loop, and S6 helices are shown in cylinder representation and in cyan, brown, and blue, respectively. The C-terminal aromatic residue of each S6 is shown in stick representation. B and C, cytoplasmic views (perpendicular to view A) of the S6 helices of wild-type and F1449V channels, respectively.

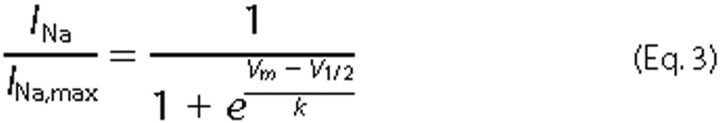

We investigated the effect of substitution of F1449 with an aliphatic hydrophobic residue leucine (F1449L), and the aromatic residues tyrosine (F1449Y) and tryptophan (F1449W). Fig. 3 shows Nav1.7 homology models with F1449V, F1449L, F1449Y, and F1449W substitutions. Calculations of the diameter of the pore in the vicinity of the aromatic residues reveal that the calculated pore diameter of WT channel is 0.6 Å, and that of F1449V is almost double at 1.1 Å. The substitution of another hydrophobic residue leucine (F1449L) is 0.76 Å, whereas substitution of F1449 by aromatic residues tyrosine (F1449Y) reduces the pore diameter to 0.5 Å, and tryptophan (F1449W) to 0.45 Å. Therefore changes in side-chain size alter the effective plugging of the pore in addition to reshaping inter-domain contact surfaces that are involved in the putative closed-state stabilization.

FIGURE 3.

Cytoplasmic views of the C-terminal ends of S6 helices of wild-type and mutant channels. The substitution of F1449 with valine increases the diameter of the pore from 0.6 Å to 1.1 Å. The diameter of the pore of F1449L, which has an extra methyl group in its side chain compared with valine, increases the diameter modestly to 0.76 Å. The substitution of tyrosine causes a reduction in the pore diameter to 0.5 Å, whereas F1449W, with a bulkier side chain compared with phenylalanine, produces the smallest pore diameter of 0.45 Å.

Effect of Substitutions at F1449 on Channel Opening—The predicted effects of substitutions at F1449 that emerged from computer modeling were tested in whole cell patch clamp studies. Whole cell patch clamp recordings of HEK 293 cells that were co-transfected with wild-type Nav1.7R (WT) or mutant channels and green fluorescent protein were carried out as described under “Experimental Procedures.” To avoid heterogeneity caused by transfections of up to four plasmids (α-subunit, β1 and β2 subunits, and green fluorescent protein), only the Nav1.7 channel α-subunit and green fluorescent protein were transfected into HEK 293 cells. As expected, WT and mutant Nav1.7 constructs produced fast inactivating transient sodium current (Fig. 4A, 5A, and Fig. 6A). The capacitance of HEK 293 cells did not significantly change when transfected with WT or mutant Nav1.7R constructs (Table 1). WT and DIII/F1449V, DIII/F1449L, or DIII/F1449Y channels produced comparable current densities while DIII/F1449W channels produced a significantly smaller current density that is about half that of WT channels (Table 1).

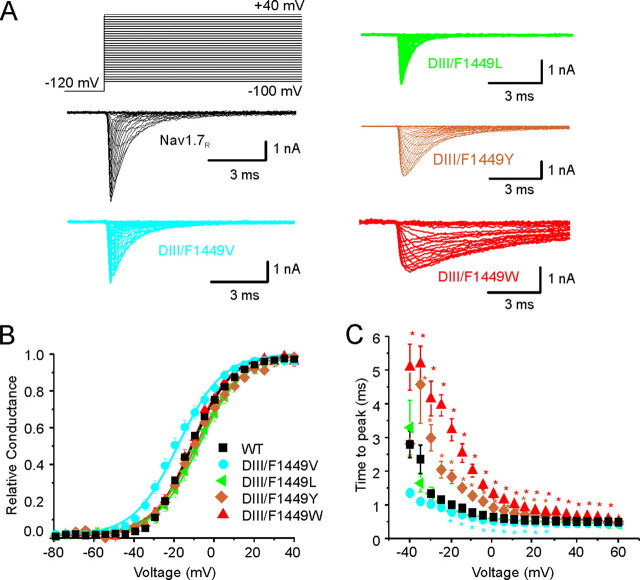

FIGURE 4.

Substitutions reveal importance of hydrophobicity and aromaticity at the C terminus of DIII/S6 for channel opening. A, representative traces of current families recorded from HEK 293 cells transiently expressing Nav1.7R WT (black traces), DIII/F1449V (cyan traces) DIII/F1449L (green traces), DIII/F1449Y (golden traces), or DIII/F1449W (red traces). Cells were held at -120 mV and depolarized stepwise to potentials ranging from -80 mV to +60 mV in 5-mV steps (see protocol; data displayed in the range from -80 mV to +40 mV). B, voltage dependence of activation is shown for Nav1.7R (black squares), DIII/F1449V (cyan circles), DIII/F1449L (green triangles), DIII/F1449Y (golden diamonds), or DIII/F1449W (red triangles). Conductance curves were deduced from current-voltage families, normalized, and fitted with a Boltzmann equation, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Lines are Boltzmann fits of mean values. C, voltage dependence of time to peak is shown for step depolarizations from a holding potential of -120 mV to the indicated voltages. The mutation DIII/F1449V (cyan circles) opens faster than Nav1.7R (black squares) at -10 mV, the mutations DIII/F1449Y (golden diamonds) or DIII/F1449W (red triangles) open slower, whereas the mutation DIII/F1449L (green triangles) shows no change compared with WT.

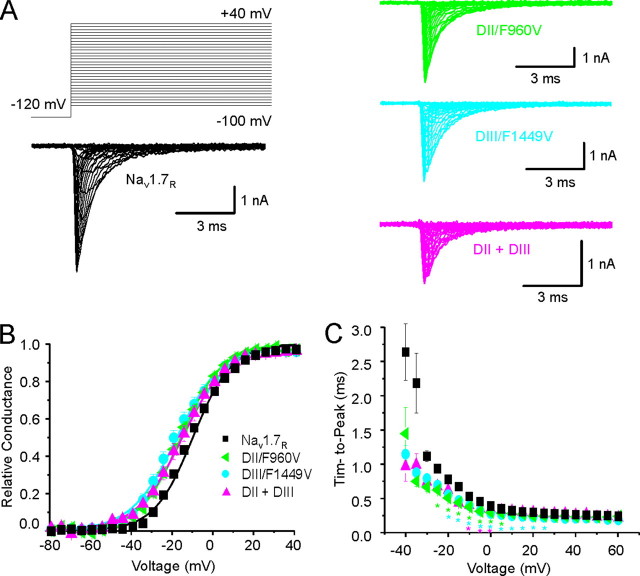

FIGURE 5.

Contribution of C terminus residues of DII/S6 and DIII/S6 to channel opening. A, representative traces of current families recorded from HEK 293 cells transiently expressing Nav1.7R WT (black traces), DII/F960V (green traces), DIII/F1449V (cyan traces), or the double mutation F960V/F1449V (magenta traces). B, voltage dependence of activation is shown for Nav1.7R (black squares), DII/F960V (green triangles), DIII/F1449V (cyan circles), or the double mutation F960V/F1449V (magenta triangles). C, voltage dependence of time to peak is shown for step depolarizations from a holding potential of -120 mV to the indicated voltages. The mutations DII/F960V (green triangles), DIII/F1449V (cyan circles), or the double mutation F960V/F1449V (magenta triangles) open faster than Nav1.7R (black squares) at -10 mV. WT and DIII/F1449V data are identical to those of Fig. 4 and are added for comparison.

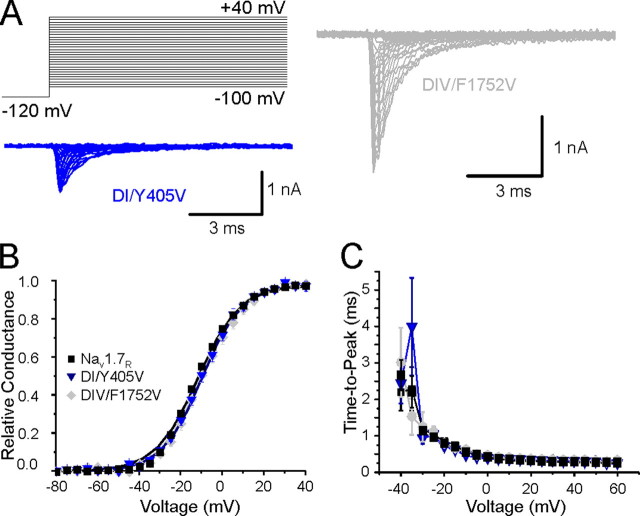

FIGURE 6.

Mutations DI/Y405V and DIV/F1752V do not alter activation kinetics. A, representative current-voltage (I-V) families recorded from HEK293 cells expressing DI/Y405V (blue traces) or DIV/F1752V (gray traces). B, conductance curves of Nav1.7R WT (black squares), DI/Y405V (blue triangles), and DIV/F1752V (gray diamonds), deduced from current-voltage families as described in methods. Lines are Boltzmann fits of mean values. C, time to peak from the onset of stimulation pulse is shown at various potentials for Nav1.7R WT (black squares), DI/Y405 (blue triangles), and DIV/F1752V (gray diamonds). WT data are identical with those of Fig. 4 and are added for comparison.

TABLE 1.

Activation and steady-state fast-inactivation parameters of Nav 1.7 channels with substitutions at the Phe-1449 position

Whole cell patch clamp recordings in transfected HEK 293 cells were used to measure current density, voltage dependence of activation and time to peak, and steady-state fast inactivation of wild-type (WT) and mutant Nav1.7 sodium channels. The terminal residue, phenylalanine, in domain III segment 6 (DIII/F1449) was substituted by valine (DIII/F1449V), leucine (DIII/F1449L), tyrosine (DIII/F1449Y), or tryptophan (DIII/F1449W). n is the number of cells analyzed for each parameter. Statistical significance was tested using analysis of variance and two-sided Dunnett's multiple comparison test as post-hoc analysis. All data are compared to WT and presented as mean ± S.E. pF, picofarads.

| WT | DIII/F1449V | DIII/F1449L | DIII/F1449Y | DIII/F1449W | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capacitance (pF) | 15.4 ± 1.1 (n = 57) | 14.1 ± 1.1 (n = 13) | 17.8 ± 1.8 (n = 16) | 20.7 ± 4.6 (n = 15) | 16.8 ± 3.2 (n = 13) |

| Current density (pA/pF) | 264.5 ± 28.9 (n = 57) | 228.6 ± 45.6 (n = 13) | 165.1 ± 40.1 (n = 16) | 180.9 ± 46.5 (n = 15) | 114.1 ± 18.3a (n = 13) |

| Activation V½ (mV) | −10.89 ± 0.78 (n = 53) | −18.11 ± 1.9b (n = 11) | −7.73 ± 2.13 (n = 15) | −8.99 ± 1.91 (n = 13) | −10.83 ± 0.92 (n = 9) |

| Slope factoract | 9.54 ± 0.26 (n = 53) | 10.59 ± 0.53 (n = 11) | 9.81 ± 0.48 (n = 15) | 10.60 ± 0.74 (n = 13) | 9.55 ± 0.71 (n = 9) |

| Time to peak at −10 mV (ms) | 0.54 ± 0.02 (n = 53) | 0.41 ± 0.02a (n = 11) | 0.47 ± 0.03 (n = 13) | 1.07 ± 0.1b (n = 13) | 1.85 ± 0.2b (n = 9) |

| Fast-inactivation V½ (mV) | −78.8 ± 0.7 (n = 56) | −74.5 ± 1.6 (n = 10) | −77.6 ± 1.3 (n = 10) | −57.3 ± 1.5b (n = 15) | −65.0 ± 1.7b (n = 14) |

| Slope factorinact | 6.9 ± 0.2 (n = 56) | 7.2 ± 0.2 (n = 10) | 8.84 ± 0.6b (n = 12) | 8.0 ± 0.9 (n = 15) | 6.4 ± 0.3 (n = 14) |

Significantly different compared to WT, p < 0.05.

Significantly different compared to WT, p < 0.01.

We have previously shown that the F1449V mutation at the cytoplasmic end of DIII/S6 changes gating of Nav1.7R compared with wild-type channels (13). We confirmed these changes in the current study (Table 1). The F1449V mutation causes a significant (p < 0.01) shift of -7.22 mV compared with WT channels in the voltage dependence of activation (Fig. 4B and Table 1). The hyperpolarizing shift in voltage dependence of activation of -7.2 mV induced by the F1449V in this set of experiments is comparable to the -7.6 mV shift that was previously reported (13).

To measure the rate of opening of the channel, we computed the time from the test pulse onset to the peak of sodium inward current (time to peak) at a series of voltages applied from the holding potential of -120 mV. Time to peak was plotted as a function of test voltages (Fig. 4C and Table 1), showing that F1449V channels open faster (p < 0.05) than WT channels. This finding provides additional evidence that DIII/F1449V may destabilize the closed state of Nav1.7.

Introducing the substitution F1449L and thereby elongating the side chain by one methyl group compared with valine restored the channel's wild-type characteristics (Fig. 4, B and C, and Table 1). As can be seen in Fig. 3, the aperture of F1449L is closer to that of the WT, consistent with similar activation properties. The substitution of the bulkier amino acids tyrosine (F1449Y) or tryptophan (F1449W) leads to a longer time to peak at -10 mV but without changing voltage dependence of activation (Fig. 4, B and C, and Table 1). These findings suggested that a bulky, hydrophobic residue at the C terminus of S6 is necessary for normal activation of Nav1.7.

DII/F960 and DIII/F1449 in S6 Segments Regulate Channel Activation and Time to Peak—The role of a hydrophobic gate at the cytoplasmic aperture of the Nav1.7 pore, which is formed by the S6 C-terminal aromatic residues in all four domains (DI/Y405, DII/F960, DIII/F1449, and DIV/F1752), was tested experimentally by substituting these residues with valine to mimic the naturally occurring IEM mutation DIII/F1449V and measuring the effect of this substitution on channel gating properties. The capacitance of HEK 293 cells did not significantly change when transfected with WT or mutant Nav1.7R constructs (Table 2). DII/F960V, DIII/F1449V, and DIV/F1752V mutant channels produced current densities comparable to WT channels, whereas DI/Y405V and the double mutant F960V/F1449V channels produced significantly lower current densities than WT channels (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Effects of valine substitutions at the terminal aromatic residue of each S6 of Nav 1.7

Whole cell patch clamp recordings in transfected HEK 293 cells were used to measure current density, voltage dependence of activation and time to peak, and steady-state fast inactivation of wild-type (WT) and mutant Nav1.7 sodium channels. The terminal aromatic residue in S6, tyrosine in domain I and phenylalanine in domains II, III, and IV, were substituted by valine: DI/Y405V, DII/F960V, DIII/F1449V, and DIV/F1752V. Data for WT and DIII/F1449V are from Table 1. n is the number of cells analyzed for each parameter. Statistical significance was tested using analysis of variance and two-sided Dunnett's multiple comparison test as post-hoc analysis. All data are compared to WT and presented as mean ± S.E. pF, picofarads.

| WT | DI/Y405V | DII/F960V | DIII/F1449V | DIV/F1752V | F960V/F1449V | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capacitance (pF) | 15.4 ± 1.1 (n = 57) | 17.7 ± 1.4 (n = 14) | 16.2 ± 1.8 (n = 17) | 14.1 ± 1.1 (n = 13) | 17.3 ± 2.6 (n = 13) | 21.9 ± 2.9 (n = 20) |

| Current density (pA/pF) | 264.5 ± 28.9 (n = 57) | 121.6 ± 24.6a (n = 14) | 279.0 ± 47.1 (n = 17) | 228.60 ± 45.6 (n = 13) | 199.2 ± 52.7 (n = 13) | 89.0 ± 10.5b (n = 20) |

| Activation V½ (mV) | −10.89 ± 0.78 (n = 53) | −9.5 ± 1.36 (n = 12) | −16.34 ± 1.21a (n = 15) | −18.11 ± 1.9b (n = 11) | −8.8 ± 1.71 (n = 11) | −15.47 ± 1.68a (n = 17) |

| Slope factoract | 9.45 ± 0.26 (n = 53) | 9.67 ± 0.46 (n = 12) | 9.71 ± 0.31 (n = 15) | 10.59 ± 0.53 (n = 11) | 9.64 ± 0.32 (n = 11) | 10.20 ± 0.50 (n = 17) |

| Time to peak at −10 mV (ms) | 0.54 ± 0.02 (n = 53) | 0.46 ± 0.04 (n = 9) | 0.39 ± 0.02b (n = 15) | 0.41 ± 0.02a (n = 11) | 0.6 ± 0.05 (n = 11) | 0.41 ± 0.03b (n = 14) |

| Fast-inactivation V½ (mV) | −78.8 ± 0.7 (n = 56) | −78.5 ± 1.8 (n = 10) | −87.3 ± 1.6b (n = 15) | −74.5 ± 1.6 (n = 10) | −76.2 ± 2 (n = 12) | −75.7 ± 1.8 (n = 12) |

| Slope factorinact | 6.9 ± 0.2 (n = 56) | 7.5 ± 0.8 (n = 10) | 7.2 ± 0.2 (n = 15) | 7.2 ± 0.2 (n = 10) | 8.0 ± 0.4 (n = 12) | 7.8 ± 0.40 (n = 12) |

Significantly different compared to WT, p < 0.05.

Significantly different compared to WT, p < 0.01.

F960 in the S6 of DII also contributes to normal channel activation. Similar to DIII/F1449V substitution, the substitution DII/F960V caused a hyperpolarizing shift of voltage dependence of activation (Fig. 5B and Table 2) and a shorter time to peak (Fig. 5C) compared with WT channels. The combination of both mutations (F960V/F1449V) conferred a hyperpolarizing shift in activation, compared with WT channels, which is similar to that of the individual mutations (Table 2). In contrast, mutations of the aromatic residues at the cytoplasmic end of S6 in DI (Y405V) and DIV (F1752V) did not alter the voltage dependence of activation (Fig. 6B and Table 2) or time to peak (Fig. 6C) compared with WT channels.

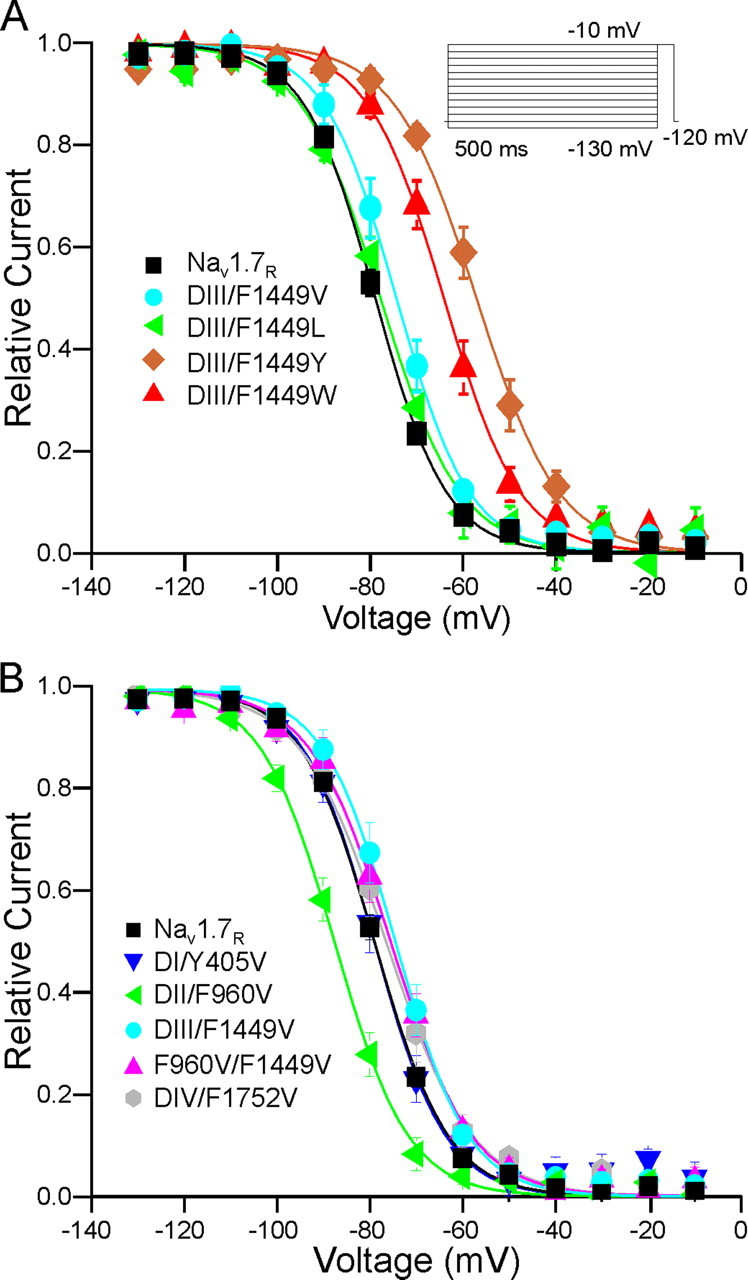

DII/F960 Regulates Steady-state Fast Inactivation of Nav1.7R—We investigated the effect of all of these Nav1.7 mutations on the voltage dependence of steady-state fast inactivation using a 500-ms pre-pulse followed by a short test pulse assessing availability (Fig. 7 and Tables 1 and 2). Boltzmann fits of steady-state fast inactivation reveals a small depolarizing shift for DIII/F1449V (Table 1), similar to what was reported earlier (13), which did not reach significance, possibly due to the need to use multiple comparisons.

FIGURE 7.

Voltage dependence of steady-state fast inactivation of Nav1.7R and mutant derivatives. A, steady-state inactivation of DIII/F1449W and DIII/F1449Y are shifted to more depolarized potentials. Voltage dependence values of steady-state fast inactivation are shown for Nav1.7R WT (black squares), DIII/F1449V (cyan circles), DIII/F1449L (green triangles), DIII/F1449Y (golden diamonds), or DIII/F1449W (red triangles). B, voltage dependence of steady-state fast inactivation are shown for Nav1.7R WT (black squares), DI/Y405V (blue triangles), DII/F960V (green triangles), DIII/F1449V (cyan circles), or DIV/F1752V (gray diamonds) and the double mutation F960V/F1449V (magenta triangles). For better comparison, WT and DIII/F1449V are shown in both graphs. Steady-state fast inactivation was obtained by measuring the current evoked by a 40-ms pulse to -10 mV after inducing fast inactivation with a 500-ms pre-pulse to potentials ranging from -130 mV to -10 mV (see protocol). DII/F960V shows a hyperpolarized shift in steady-state fast inactivation.

DIII/F1449L substitution does not alter steady-state fast inactivation compared with WT channels (Fig. 7A and Table 1). In contrast, introducing a more hydrophobic amino acid, DIII/F1449W led to a pronounced depolarizing shift (+13.8 mV, p < 0.01) of the V½ of steady-state fast inactivation, whereas DIII/F1449Y causes an even bigger depolarizing effect (+21.6 mV, p < 0.01) on the V½ of steady-state fast inactivation (Fig. 7A and Table 1).

Compared with WT channels, DII/F960V mutant channels showed a significant hyperpolarizing shift (-8.5 mV, p < 0.01) of the V½ of steady-state fast inactivation (Fig. 7B and Table 2). The midpoints and slope factors of steady-state fast inactivation for DI/Y405V, DIV/F1752V, and the double mutant F960V/F1449V were comparable to WT channels (Fig. 7B and Table 2).

DISCUSSION

The Nav1.7 sodium channel, which is preferentially expressed in nociceptors, has been the subject of intense recent interest because point mutations in this channel are linked with several human painful disorders, including inherited erythromelalgia, a striking disorder in which mutant Nav1.7 produces hyperexcitability of nociceptors (6). The increase in nociceptor excitability is largely caused by a hyperpolarizing shift in voltage dependence of activation (17). In this study, we examined the structural basis for the effect on activation of the F1449V erythromelalgia mutation.

Crystallographic studies of potassium channels have helped to elucidate the structural basis for channel ion selectivity, pore gating, and coupling of voltage-sensor domains to the pore domain (21, 22, 43). Potassium channel structures have provided templates for homology modeling of voltage-gated sodium channel transmembrane regions (44). The resultant sodium channel models have been used for ligand-docking studies (23, 37, 45) and have provided structural frameworks for modeling the selectivity filter and channel vestibule (46).

In this study the crystal structure of Streptomyces lividans potassium channel KcsA (21) provided the template for homology modeling of the Nav1.7 pore domain in the closed conformation, facilitating structural comparison of the wild-type and disease-associated mutant channel. The gating-hinge glycine and serine residues in human sodium channels and bacterial potassium channel sequences were aligned (Fig. 1) to produce the helix register of the four S6 segments of the sodium channels, with binding determinants of pore-binding ligands oriented into the pore. We identified aromatic residues, which are conserved in most sodium channel isoforms (Fig. 1 and Guda et al. (47)), at equivalent positions in the C terminus of each of the S6 helices with their ring side chain oriented into the pore. These four residues form a hydrophobic plug at the channel's cytoplasmic aperture. Analogous hydrophobic residues that contribute to a cytoplasmic gate have been noted in the acetylcholine receptor (40) and bacterial mechanosensitive channel MscL (48). Crystallographic studies of the closed state potassium channels Kirbac1.1 and MlotiK1 revealed a structural motif of four aromatic residues at the cytoplasmic mouth of those pores (23, 49).

The Phe-146 residues in the four KirBac1.1 monomers form an energetically stable hydrophobic assembly due to extensive van der Waals' interactions between their side chains. Edge-face interaction of adjacent aromatic residues can further stabilize this structural motif via electrostatic interactions of π-electrons localized on the ring face of one residue, with partial positive charges on hydrogen atoms at the ring edge of an adjacent residue (50). Substitution of Phe-168 (analogous to Phe-146) in Kir6.2, the mammalian homologue of KirBac1.1, shows that smaller residues favor the open state, whereas the aromatic amino acid tryptophan behaves like wild-type Kir6.2 (51). Similarly, each of the aromatic residues at the C termini of Nav1.7 S6 helices (DI/Y405, DII/F960, DIII/F1449, and DIV/F1752) can interact with its neighbors to form a pore-blocking hydrophobic assembly or gate that contributes to stabilization of the Nav1.7 closed state.

Recently the structure of cyclic nucleotide-regulated potassium channel MlotiK1 crystallized in the closed state has been solved (49). Of relevance to the current study is the presence of two sets of aromatic side chains projecting into and blocking the pore in the closed state. The aromatic assemblies are located above and below the cross-over point of the helix bundle, with the more intracellularly located ring corresponding to the aromatic assembly shown in our sodium channel model. Alanine substitution of either the Phe-203 or Tyr-215 residues increased the rate of ion uptake in proteoliposomes, consistent with a destabilized closed state (49).

Structural comparison of KcsA with the potassium channel Mthk (43) suggests that the constriction at the cytoplasmic end of a closed pore, formed through close proximity contacts of the pore-lining helices, is relaxed in the open state. The pore-lining helices of the MthK open-channel crystal structure are bent around a gating-hinge glycine, with splaying of the helices producing a cytoplasmic opening (∼12 Å) of the pore. Electrophysiological studies have provided evidence for a functional gating-hinge residue in the bacterial voltage-gated sodium channel NaChBac (52). We propose that the DIII/F1449V Nav1.7 mutation substitutes a smaller, non-aromatic residue into the hydrophobic plug, weakening contacts with adjoining aromatic rings, thus eliminating a stabilizing inter-domain contact of the DIII/S6 helix; the reduced energetic barrier for DIII/S6 helix movement facilitates bending associated with pore gating. Supporting the conclusion that increased propensity of the DIII/S6 helix to move can hasten Nav1.7 activation, the DIII/F1449V mutation hyperpolarizes activation (this study and Ref. 13).

We adopted a 2-fold approach to test the hypothesis of closed-state stabilization of Nav1.7 through inter-domain hydrophobic interactions. First, the Nav1.7 Phe-1449 residue was mutated to residues differing in size and aromaticity. Second, the aromatic residue at the equivalent position to Phe-1449 in each S6 helix was mutated to valine to mimic the F1449V mutation.

Electrophysiological analysis of these mutant Nav1.7 channels reveals changes in closed-to-open state kinetics, namely time to peak and mid-point of activation, showing that, of the F1449L, F1449Y, F1449W, and F1449V mutations tested, F1449V has the greatest destabilizing effect on the closed state. In contrast F1449L channels have wild-type activation kinetics, whereas the F1449Y and F1449W channels increase the time to peak. Thus the effect of the hydrophobic substitution at position 1449 can be correlated with size of the hydrophobic residue, consistent with our model of a cytoplasmic aperture within Nav1.7 modulated by inter-domain interactions.

C-terminal valine substitution in each S6 helix revealed that the effect was domain-dependent: F960V substitution at the analogous site in DII/S6 produced a similar effect on Nav1.7 activation, whereas the Y405V or F1752V mutations at analogous sites in DI/S6 and DIV/S6 did not. Thus, the four aromatic residues form a hydrophobic ring, but with unequal contributions to Nav1.7 closed-state stability. The effects of DIII/F1449V and DIV/F1752V mutations can be correlated with different activation kinetics of their domains (53, 54). Domain III activates fastest, and the DIII/F1449V mutation shifts activation to more hyperpolarized potentials, consistent with a destabilized closed state arising from increased DIII/S6 bending propensity. In contrast, domain IV/S4 movement correlates with the slow component (53), and the DIV/F1752V mutation retains wild-type activation. Fluorescence imaging studies (53) in Nav1.4 suggest that the ionic current onset occurs faster than the kinetics of DIV/S4 movement, indicating that DIV/S4 voltage-dependent movement, and by extension DIV/S6 helix bending, may not be necessary for pore opening.

The DII/F960V substitution in Nav1.7 shifts activation by -5.5 mV, similar to DIII/F1449V. The role of domain II in promoting activation is demonstrated by the effect of β-scorpion toxin and insecticides, which have been shown to bind to S1-S2 and S3-S4 or S4-S5 and S5 sections of domain II in Drosophila sodium channels and Nav1.4, stabilizing the voltage sensor in its activated state (55, 56). The voltage dependence of the toxin-modified channel is shifted to more negative potentials. The DII/F960V mutation also hyperpolarizes Nav1.7 activation albeit with a less dramatic effect. The increased bias of the mutated DII/S6 to adopt the activated conformation is predicted to consequently promote activation of the domain II voltage sensor in Nav1.7.

With domain III activating fastest (53) and domain II apparently sharing a role in the early stages of activation, gating-associated movements of domain I may occur later in the process. Thus the DI/Y405V mutation would be expected to have less impact than DII/F960V or DIII/F1449V mutations, as is the case. If sufficient movement of DII/S6 or DIII/S6 does occur initially, then the hydrophobic ring would be effectively disrupted, and DI/Y405V would have a negligible effect on stabilization of DI/S6 in the closed-state position. Consistent with this view, the double mutant F960V/F1449V produces a shift in Nav1.7 activation similar to those of the individual substitutions.

Sodium channel fast inactivation occurs when the tripeptide IFM within the domain III-IV intracellular linker docks at its receptor site, occluding the pore (57). The receptor site includes hydrophobic residues of the S4-S5 linkers of domains III and IV and the C-terminal half of DIV/S6 (58-60). The DII/F960 and DIII/Phe-1449 residues might contribute to the inactivation particle receptor site in Nav1.7 or have an allosteric effect on formation of this site, so that fast inactivation is altered by DII/F960V and DIII/F1449V mutations. Interestingly, the DIII/F1449V mutation appears to de-link activation and inactivation (which are shifted in opposite directions), and this effect is dominant in the double mutant channel over DII/F960 (Fig. 7B), which hyperpolarizes fast inactivation. Paradoxically, DIII/F1449Y and DIII/F1449W produce large depolarizing shifts in steady-state fast inactivation, suggesting that they favor the Nav1.7 open state. The phenotype of DII/F960 mutant channels suggests coupling of activation and inactivation rather than a contribution to the IFM peptide receptor site. DIV/F1752V substitution, however, does not affect fast inactivation of Nav1.7. Thus either F1752 does not contribute to the Nav1.7 inactivation particle receptor, or the F1752V substitution retains sufficient hydrophobicity to maintain block of the pore by interaction with the IFM tripeptide.

In conclusion, the F1449V erythromelalgia mutation of Nav1.7 produces a hyperpolarizing shift in activation (13) that has been shown to be a major driver of nociceptor hyperexcitability (17), which underlies chronic pain. The homology model and functional data implicate the S6 C-terminal aromatic residues in a putative hydrophobic block of Nav1.7 cytoplasmic aperture. The present study provides a structural basis for gating changes that destabilize the closed state of the Nav1.7 channel.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Xiaoyang Cheng and Dr. Mark Estacion for helpful discussions and Bart Toftness for technical assistance.

This work was supported in part by grants from the Rehabilitation Research Service and Medical Research Service, Department of Veterans Affairs, the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, and the Erythromelalgia Association. The work in the laboratory of B. A. W. was supported by grants from the UK Biotechnology and Biological Sciences and Research Council. The Center for Neuroscience and Regeneration Research is a Collaboration of the Paralyzed Veterans of America and the United Spinal Association with Yale University. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: DRG, dorsal root ganglion; IEM, inherited erythromelalgia; DI-III, domains I-III; WT, wild type; TTX, tetrodotoxin.

References

- 1.Wall, P. D., and Gutnick, M. (1974) Nature 248 740-743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Devor, M., and Wall, P. D. (1990) J. Neurophysiol. 64 1733-1746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wall, P. D., and Devor, M. (1983) Pain 17 321-339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waxman, S. G. (2001) Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2 652-659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rice, A. S., and Hill, R. G. (2006) Annu. Rev. Med. 57 535-551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dib-Hajj, S. D., Cummins, T. R., Black, J. A., and Waxman, S. G. (2007) Trends Neurosci. 30 555-563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fertleman, C. R., Baker, M. D., Parker, K. A., Moffatt, S., Elmslie, F. V., Abrahamsen, B., Ostman, J., Klugbauer, N., Wood, J. N., Gardiner, R. M., and Rees, M. (2006) Neuron 52 767-774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox, J. J., Reimann, F., Nicholas, A. K., Thornton, G., Roberts, E., Springell, K., Karbani, G., Jafri, H., Mannan, J., Raashid, Y., Al-Gazali, L., Hamamy, H., Valente, E. M., Gorman, S., Williams, R., McHale, D. P., Wood, J. N., Gribble, F. M., and Woods, C. G. (2006) Nature 444 894-898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldberg, Y., Macfarlane, J., Macdonald, M., Thompson, J., Dube, M. P., Mattice, M., Fraser, R., Young, C., Hossain, S., Pape, T., Payne, B., Radomski, C., Donaldson, G., Ives, E., Cox, J., Younghusband, H., Green, R., Duff, A., Boltshauser, E., Grinspan, G., Dimon, J., Sibley, B., Andria, G., Toscano, E., Kerdraon, J., Bowsher, D., Pimstone, S., Samuels, M., Sherrington, R., and Hayden, M. (2007) Clin. Genet. 71 311-319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmad, S., Dahllund, L., Eriksson, A. B., Hellgren, D., Karlsson, U., Lund, P. E., Meijer, I. A., Meury, L., Mills, T., Moody, A., Morinville, A., Morten, J., O'Donnell, D., Raynoschek, C., Salter, H., Rouleau, G. A., and Krupp, J. J. (2007) Hum. Mol. Genet. 16 2114-2121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi, J. S., Dib-Hajj, S. D., and Waxman, S. G. (2006) Neurology 67 1563-1567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cummins, T. R., Dib-Hajj, S. D., and Waxman, S. G. (2004) J. Neurosci. 24 8232-8236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dib-Hajj, S. D., Rush, A. M., Cummins, T. R., Hisama, F. M., Novella, S., Tyrrell, L., Marshall, L., and Waxman, S. G. (2005) Brain 128 1847-1854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han, C., Rush, A. M., Dib-Hajj, S. D., Li, S., Xu, Z., Wang, Y., Tyrrell, L., Wang, X., Yang, Y., and Waxman, S. G. (2006) Ann. Neurol. 59 553-558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harty, T. P., Dib-Hajj, S. D., Tyrrell, L., Blackman, R., Hisama, F. M., Rose, J. B., and Waxman, S. G. (2006) J. Neurosci. 26 12566-12575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lampert, A., Dib-Hajj, S. D., Tyrrell, L., and Waxman, S. G. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 36029-36035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheets, P. L., Jackson Ii, J. O., Waxman, S. G., Dib-Hajj, S., and Cummins, T. R. (2007) J. Physiol. (Lond.) 581 1019-1031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rush, A. M., Dib-Hajj, S. D., Liu, S., Cummins, T. R., Black, J. A., and Waxman, S. G. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103 8245-8250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waxman, S. G., and Dib-Hajj, S. (2005) Trends Mol. Med. 11 555-562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Catterall, W. A. (2000) Neuron 26 13-25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doyle, D. A., Morais Cabral, J., Pfuetzner, R. A., Kuo, A., Gulbis, J. M., Cohen, S. L., Chait, B. T., and MacKinnon, R. (1998) Science 280 69-77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Long, S. B., Campbell, E. B., and MacKinnon, R. (2005) Science 309 897-903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuo, A., Gulbis, J. M., Antcliff, J. F., Rahman, T., Lowe, E. D., Zimmer, J., Cuthbertson, J., Ashcroft, F. M., Ezaki, T., and Doyle, D. A. (2003) Science 300 1922-1926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cronin, N. B., O'Reilly, A., Duclohier, H., and Wallace, B. A. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 10675-10682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lipkind, G. M., and Fozzard, H. A. (2000) Biochemistry 39 8161-8170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scheib, H., McLay, I., Guex, N., Clare, J. J., Blaney, F. E., Dale, T. J., Tate, S. N., and Robertson, G. M. (2006) J. Mol. Model (Online) 12 813-822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ranatunga, K. M., Law, R. J., Smith, G. R., and Sansom, M. S. P. (2001) Eur. Biophys. J. 30 295-303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stansfeld, P. J., Gedeck, P., Gosling, M., Cox, B., Mitcheson, J. S., and Sutcliffe, M. J. (2007) Proteins 68 568-580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cosconati, S., Marinelli, L., Lavecchia, A., and Novellino, E. (2007) J. Med. Chem. 50 1504-1513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tikhonov, D. B., and Zhorov, B. S. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283 17594-17604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thompson, J. D., Higgins, D. G., and Gibson, T. J. (1994) Nucleic Acids Res. 22 4673-4680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clark, M., Cramer, R., and Van Opdenbosch, N. (1989) J. Computat. Chem. 10 982-1012 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smart, O. S., Neduvelil, J. G., Wang, X., Wallace, B. A., and Sansom, M. S. P. (1996) J. Mol. Graph. 14 354-360, 376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herzog, R. I., Cummins, T. R., Ghassemi, F., Dib-Hajj, S. D., and Waxman, S. G. (2003) J. Physiol. (Lond.) 551 741-750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hamill, O. P., Neher, M. A., Sakmann, B., and Sigworth, F. J. (1981) Pflügers Arch. 391 85-100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cummins, T. R., Zhou, J., Sigworth, F. J., Ukomadu, C., Stephan, M., Ptacek, L. J., and Agnew, W. S. (1993) Neuron 10 667-678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cestele, S., Yarov-Yarovoy, V., Qu, Y., Sampieri, F., Scheuer, T., and Catterall, W. A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 21332-21344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holyoake, J., Domene, C., Bright, J. N., and Sansom, M. S. P. (2004) Eur. Biophys. J. 33 238-246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shimizu, H., Iwamoto, M., Konno, T., Nihei, A., Sasaki, Y. C., and Oiki, S. (2008) Cell 132 67-78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Unwin, N. (1995) Nature 373 37-43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beckstein, O., and Sansom, M. S. P. (2006) Phys. Biol. 3 147-159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miyazawa, A., Fujiyoshi, Y., and Unwin, N. (2003) Nature 423 949-955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jiang, Y., Lee, A., Chen, J., Cadene, M., Chait, B. T., and MacKinnon, R. (2002) Nature 417 523-526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cronin, N. B., O'Reilly, A., Duclohier, H., and Wallace, B. A. (2005) Biochemistry 44 441-449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O'Reilly, A. O., Khambay, B. P., Williamson, M. S., Field, L. M., Wallace, B. A., and Davies, T. G. (2006) Biochem. J. 396 255-263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tikhonov, D. B., and Zhorov, B. S. (2005) Biophys. J. 88 184-197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guda, P., Bourne, P. E., and Guda, C. (2007) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 352 292-298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sukharev, S., Betanzos, M., Chiang, C. S., and Guy, H. R. (2001) Nature 409 720-724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Clayton, G. M., Altieri, S., Heginbotham, L., Unger, V. M., and Morais-Cabral, J. H. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105 1511-1515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burley, S. K., and Petsko, G. A. (1985) Science 229 23-28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rojas, A., Wu, J., Wang, R., and Jiang, C. (2007) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1768 39-51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhao, Y., Yarov-Yarovoy, V., Scheuer, T., and Catterall, W. A. (2004) Neuron 41 859-865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chanda, B., and Bezanilla, F. (2002) J. Gen. Physiol. 120 629-645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chanda, B., Asamoah, O. K., and Bezanilla, F. (2004) J. Gen. Physiol. 123 217-230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Campos, F. V., Chanda, B., Beirao, P. S., and Bezanilla, F. (2007) J. Gen. Physiol. 130 257-268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Usherwood, P. N., Davies, T. G., Mellor, I. R., O'Reilly, A. O., Peng, F., Vais, H., Khambay, B. P., Field, L. M., and Williamson, M. S. (2007) FEBS Lett. 581 5485-5492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.West, J. W., Patton, D. E., Scheuer, T., Wang, Y., Goldin, A. L., and Catterall, W. A. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89 10910-10914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McPhee, J. C., Ragsdale, D. S., Scheuer, T., and Catterall, W. A. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91 12346-12350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McPhee, J. C., Ragsdale, D. S., Scheuer, T., and Catterall, W. A. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273 1121-1129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smith, M. R., and Goldin, A. L. (1997) Biophys. J. 73 1885-1895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]