Abstract

Phosphatidylethanolamine is a major phospholipid class of all eukaryotic cells. It can be synthesized via the CDP-ethanolamine branch of the Kennedy pathway, by decarboxylation of phosphatidylserine, or by base exchange with phosphatidylserine. The contributions of these pathways to total phosphatidylethanolamine synthesis have remained unclear. Although Trypanosoma brucei, the causative agent of human and animal trypanosomiasis, has served as a model organism to elucidate the entire reaction sequence for glycosylphosphatidylinositol biosynthesis, the pathways for the synthesis of the major phospholipid classes have received little attention. We now show that disruption of the CDP-ethanolamine branch of the Kennedy pathway using RNA interference results in dramatic changes in phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylserine, and phosphatidylcholine. By targeting individual enzymes of the pathway, we demonstrate that de novo phosphatidylethanolamine synthesis in T. brucei procyclic forms is strictly dependent on the CDP-ethanolamine route. Interestingly, the last step in the Kennedy pathway can be mediated by two separate activities leading to two distinct pools of phosphatidylethanolamine, consisting of predominantly alk-1-enyl-acyl- or diacyl-type molecular species. In addition, we show that phosphatidylserine in T. brucei procyclic forms is synthesized exclusively by base exchange with phosphatidylethanolamine.

Phospholipids are major constituents of all biological membranes. In eukaryotic cells, phosphatidylcholine (PC)3 and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) represent the most abundant phospholipid classes, usually comprising 30–50 and 20–40%, respectively, of total phospholipid (1, 2). Besides being structural components, phospholipids are involved in various regulatory and trafficking processes and may affect protein function (3–7). Because the sites of phospholipid synthesis are localized in different organelles, a complex lipid trafficking system is needed to ensure proper distribution of all lipids within a cell (8).

Eukaryotic cells possess three different pathways for PE synthesis (1, 2, 9, 10). In the CDP-ethanolamine (CDP-Etn) branch of the Kennedy pathway (11), ethanolamine (Etn) is phosphorylated to ethanolamine-phosphate (Etn-P) by ethanolamine kinase (EK) and activated with CTP to CDP-Etn by ethanolamine-phosphate cytidylyltransferase (ET). Both reactions take place in the cytoplasm. CDP-Etn is subsequently transferred onto diradyglycerol by choline/ethanolamine-phosphotransferase (CEPT), a transmembrane protein localized to the endoplasmic reticulum and nuclear membrane. Many of the enzymes involved in PE synthesis by the Kennedy pathway in different cells show dual specificities for Etn and choline metabolites. However, evidence is emerging that specific enzymes for the CDP-Etn and CDP-choline branches also exist (12). In particular, a human Etn-specific phosphotransferase (EPT) has recently been cloned and characterized (13).

Alternatively, PE can be synthesized by decarboxylation of phosphatidylserine (PS) in mitochondria (14, 15). In mammalian cells, PS decarboxylation is mediated by a single gene product, whereas two separate enzymes have been identified in yeast (2). The relative contribution of PS decarboxylation to total PE synthesis varies between cells. Both the CDP-Etn and PS decarboxylase pathways for PE synthesis are essential for mouse development, however, their quantitative importance may depend on the cell type (2).

A third but quantitatively minor pathway for PE synthesis involves head group exchange (base exchange) with PS. This reaction is fully reversible and represents, together with the head group exchange with PC, the only pathway for PS synthesis in mammalian cells (2). In the mouse model, deletion of the two base exchange enzymes is lethal, whereas single knock-out animals are viable (16). In prokaryotes and yeast, PS is made by a completely different pathway involving transfer of serine to CDP-diacylglycerol (14, 17).

PE, which is preferentially located in the inner leaflet of plasma membranes, has a tendency to form non-bilayer structures and has been proposed to play important roles in membrane fusion and budding events (10, 12). Remarkably, in most eukaryotic cells substantial fractions of PE consist of alk-1-enylacyl-(plasmalogen-) and alkyl-acyl-type PE species rather than the more common diacyl-type species in most other phospho-lipid classes (12). Plasmalogen-PE species may particularly be suited for membrane fusion events because they form non-bi-layer structures at lower temperatures than diacyl-type PE species.

In Trypanosoma brucei, a protozoan parasite causing human African sleeping sickness and animal trypanosomiasis, PC and PE comprise the majority of phospholipids (18). A more detailed analysis revealed that both T. brucei bloodstream and procyclic forms are particularly rich in alk-1-enyl-acyl- and alkyl-acyl-type PE species (19). In contrast to other parasitic organisms, trypanosomes synthesize phospholipids de novo, however, the pathways for phospholipid synthesis in T. brucei have not been studied in great detail (20, 21). One exception is the biosynthesis of glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) lipids, where T. brucei has been used as a model organism to delineate the individual steps leading to GPI assembly (22). Because GPI synthesis in T. brucei bloodstream forms is essential and differs in certain aspects from the pathway in mammalian cells and yeast (23), the GPI pathway has been validated as a potential drug target against T. brucei (24). In addition, the pathway for the synthesis of phosphatidylinositol in T. brucei has recently been delineated (25, 26).

Very recently, we have shown that the pathways for PE and GPI synthesis in T. brucei procyclic forms are tightly connected. Based on a previous observation showing that PE is the precursor of the Etn group linking the GPI anchor to protein (27), we were able to completely block GPI synthesis and attachment to protein by inhibiting de novo PE synthesis using RNA interference (RNAi) against ET (28). The importance of PE synthesis for GPI assembly and cell viability prompted us to elucidate the complete biosynthetic pathway in T. brucei procyclic forms. We found that PE is organized in two separate pools, both of which are dependent on the CDP-Etn branch of the Kennedy pathway. Interestingly, the last step in PE biosynthesis by this pathway is mediated by two separate enzymes. Knocking down any of the enzymes involved in PE synthesis affects the rate of PE synthesis and the cellular phospholipid composition in T. brucei procyclic forms.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Unless otherwise noted, all reagents were of analytical grade and were from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany), Sigma, or MP Biomedicals (Tägerig, Switzerland). [1-3H]Ethan-1-ol-2-amine hydrochloride ([3H]Etn, 60 Ci mmol–1) was purchased from American Radiolabeled Chemicals Inc., St. Louis, MO. l-[G-3H]Serine ([3H]serine, 29.5 Ci mmol–1) was from PerkinElmer Life Sciences. [methyl-3H]Choline chloride ([3H]choline, 83 Ci mmol–1), [α-32P]dCTP, and Bio-Max MS films were from GE Healthcare and Kodak MBX films from Kodak (Lausanne, Switzerland).

Trypanosomes and Culture Conditions—The procyclic T. brucei strain 29-13 co-expressing T7 RNA polymerase and a tetracycline repressor (29) (obtained from Paul Englund, John Hopkins School of Medicine), which is derived from procyclic T. brucei 427, was cultured at 27 °C in SDM-79 (30) containing 15% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen), 25 μg/ml hygromycin, and 15 μg/ml G418 (Invitrogen). The derived clones AS0017, AS5730, AS1570, and AS0140 expressing different double strand RNA constructs were cultured in the presence of an additional 2 μg/ml puromycin. Generation of double-stranded RNA was induced by the addition of 1 μg/ml tetracycline.

RNAi-mediated Gene Silencing—The following gene products were down-regulated by RNAi using stem loop constructs containing a puromycin resistance gene: putative T. brucei ethanolamine kinase (GeneDB accession number Tb11.18.0017), putative T. brucei ethanolamine-phosphate cytidylyltransferase (accession number Tb11.01.5730), putative T. brucei choline/ethanolamine phosphotransferase (accession number Tb10.6k15.1570), and the gene product of Tb10.389.0140, which shows 16% amino acid sequence identity with human ethanolamine phosphotransferase (Swiss-Prot accession number Q9C0D9). Cloning of the gene fragments into the vector pALC14 (a kind gift of André Schneider, University of Bern) was performed as described (31), using PCR products obtained with primers Tb0017 (spanning nucleotides 261-810 of Tb11.18.0017), Tb5730 (spanning nucleotides 51-585 of Tb11.01.5730), Tb1570 (spanning nucleotides 236-760 of Tb10.6k15.1570), and Tb0140 (spanning nucleotides 592-1147 of Tb10.389.0140) (Table 1), resulting in plasmids pAS0017, pAS5730, pAS1570, and pAS0140, respectively. For transfection of T. brucei procyclic forms, the vectors were linearized with NotI (New England Biolabs).

TABLE 1.

Primers used for the RNAi constructs

| Primer | Direction | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| Tb0017 | Sense | 5′-GCCCAAGCTTGGATCCCTGCGAAGGATGGGAGGC-3′ |

| Antisense | 5′-CGTCTAGACTCGAGGCTGAGCAGGTCATTGTGG-3′ | |

| Tb5730 | Sense | 5′-GCCCAAGCTTGGATCCTCCGTACCCGCTTTATGCG-3′ |

| Antisense | 5′-CGTCTAGACTCGAGCAGATAGTGCGGACCCCG-3′ | |

| Tb1570 | Sense | 5′-GCCCAAGCTTGGATCCCAACGCCATTACCGTCACG-3′ |

| Antisense | 5′-CGTCTAGACTCGAGCAATCACGAACGAGCCACC-3′ | |

| Tb0140 | Sense | 5′-GCCCAAGCTTGGATCCCTTTCGCACACGCTCCACTATGAG-3′ |

| Antisense | 5′-CGTCTAGACTCGAGGCGGGCAGCTAACGAATATCAGAC-3′ |

Stable Transfection of Trypanosomes—T. brucei 29-13 procyclic forms were harvested at mid-log phase, washed once in buffer (132 mm NaCl, 8 mm KCl, 8 mm Na2HPO4, 1.5 mm KH2PO4, 0.5 mm magnesium acetate, 0.09 mm calcium acetate, pH 7.0), resuspended in 600 μl of the same buffer and mixed with 15 μg of linearized plasmids pAS0017, pAS5730, pAS1570, or pAS0140. Electroporation was performed with a BTX Electroporation 600 system (Axon Lab, Baden, Switzerland) with one pulse (1.5 kV charging voltage, 2.5 kV resistance, 25 microfarads capacitance timing, and 186 Ω resistance timing) using a 0.2-cm pulse cuvette (Bio-Rad). Electroporated cells were immediately inoculated in 10 ml of SDM-79 supplemented with 20% conditioned medium. Dilutions of 1:5 and 1:25 were plated into 24-well plates and after 24 h selected for antibiotic resistance by addition of 2 μg/ml puromycin. Clones were obtained by limiting dilution.

RNA Isolation and Northern Blot Analysis—Total RNA for Northern blotting, prepared by the standard acidic guanidium isothiocyanate method (32), was separated on formaldehyde-agarose gels (1% agarose, 2% formaldehyde in MOPS) and transferred to GeneScreen Plus nylon membranes (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). 32P-Labeled probes were made by random priming the same PCR products used as inserts in the stem-loop vector (Prime-a-Gene Labeling System, Promega, Madison, WI). Hybridization was performed overnight at 60 °C in hybridization buffer containing 7% (w/v) SDS, 1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin, 0.9 mm EDTA, 0.5 m Na2HPO4, pH 7.2. Finally, the membrane was analyzed by autoradiography using Bio-Max MS film and a TransScreen-HE intensifying screen (Kodak). Ribosomal RNA was visualized on the same formaldehyde-agarose gel by ethidium bromide staining to control for equal loading.

Metabolic Labeling and Extractions—Metabolic labeling of trypanosomes with [3H]Etn, [3H]serine, or [3H]choline was done essentially as described earlier (33). Briefly, labeled compounds were added to procyclic form trypanosomes at a density of 0.7–1.0 × 107 cells/ml, and incubations were continued for various times (16–20 h). Cells were spun down, washed with ice-cold buffer (10 mm Tris, 144 mm NaCl, pH 7.4) to remove unincorporated label, and phospholipids were extracted with 2 × 10 ml of chloroform:methanol (CM, 2:1, by volume).

[3H]Etn-labeled acid-soluble metabolites were extracted from trypanosomes according to Ref. 34. Briefly, 4 volumes of ice-cold perchloric acid were added to the washed trypanosomes. After 30 min on ice, the insoluble material was removed by centrifugation and the supernatant neutralized with 2.5 n KHCO3. After another 30 min on ice, the KHClO4 precipitate was removed by centrifugation and the supernatant dried under N2 and resuspended in H2O.

Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC)—TLC was performed on Silica Gel 60 plates. To analyze the major phospholipid classes, CM extracts were separated by one-dimensional TLC using solvent system 1, composed of chloroform:methanol:acetic acid:water (25:15:4:2, by volume). Minor phospholipid classes were separated by two-dimensional TLC using solvent system 2 (chloroform:methanol:ammonia:water, 90:74:12:9; by volume) for the first and solvent system 3 (chloroform:methanol:acetone:acetic acid:water, 40:15:15:12:8; by volume) for the second dimension (35). Etn metabolites were separated in solvent system 4, composed of 25% ammonium hydroxide, MeOH, 0.6% NaCl in water (1:10:10, by volume). On each plate, appropriate lipid standards were run alongside the samples to be analyzed. Lipid spots were visualized by exposing the plates to iodine vapor. Radioactivity was detected by scanning the air-dried plate with a radioisotope detector (Berthold Technologies, Regensdorf, Switzerland) and quantified using the Rita Star® software provided by the manufacturer. Alternatively, the plate was sprayed with EN3HANCE (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) and exposed to MXB film at –70 °C.

Lipid Phosphorous Determination—Lipid phosphorous was measured according to Rouser et al. (36). Briefly, phospholipids in chromatographic fractions scraped from TLC plates were digested by boiling in 70–72% perchloric acid for 30–45 min. The released inorganic phosphate was reacted with ammonium molybdate and the resulting blue color measured photometrically. For quantification of phosphate, each determination was accompanied by a series of inorganic phosphate standards. The assay was linear between 0 and 200 nmol of phosphate per sample (linear correlation coefficients >0.99 in all experiments).

Enzymatic and Chemical Treatment of Lipid Extracts—3H-Labeled lipid extracts were treated with Bacillus cereus phospholipase C or B. cereus phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C (Invitrogen) for 2 h at 37°Cin buffer containing 0.1% Triton X-100. After termination of the reaction, released products were extracted with water-saturated butan-1-ol and analyzed by TLC as described above. To test the susceptibility of lipids to mild base, extracts were dried under a stream of nitrogen, dissolved in 200 μl of chloroform:methanol:water (10: 10:3, by volume), and incubated with 40 μl of 0.6 m NaOH in methanol for 1 h at 37°C. Hydrolysis was stopped on ice by addition of 40 μl of 0.8 m acetic acid. The lysate was dried under N2 and partitioned between water and butan-1-ol.

Analysis of PE Molecular Species—The molecular species composition of PE was analyzed by electrospray tandem mass spectrometry (ES-MS-MS) in positive ion mode using a Waters Quattro Ultima triple quadrupole machine. Dried lipid extracts from ∼109 cells were dissolved in 400 μl of butan-1-ol with vortexing and residual salts extracted by vortexing with an equal volume of water. After centrifugation, 100 μl of the upper phase was infused, using a Harvard syringe pump, into the mass spectrometer at 6 μl/min via a megaflow source. The capillary and cone voltages were 2750 and 40 V, respectively, and the collision energy was 22 V using argon (2.9 × 10–3 mbar) as the collision gas. Spectra were collected in neural loss mode (neutral loss of m/z 141, i.e. loss of the Etn-P head group) to selectively detect PE molecular species. Spectra were collected over the m/z range of 400–1000 at 100 atomic mass units/s and groups of 70 spectra were averaged and processed using Waters MassLynx software.

RESULTS

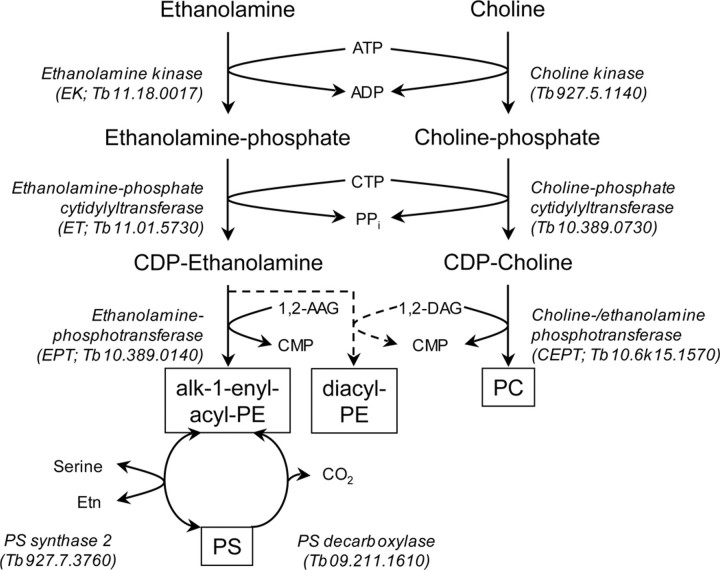

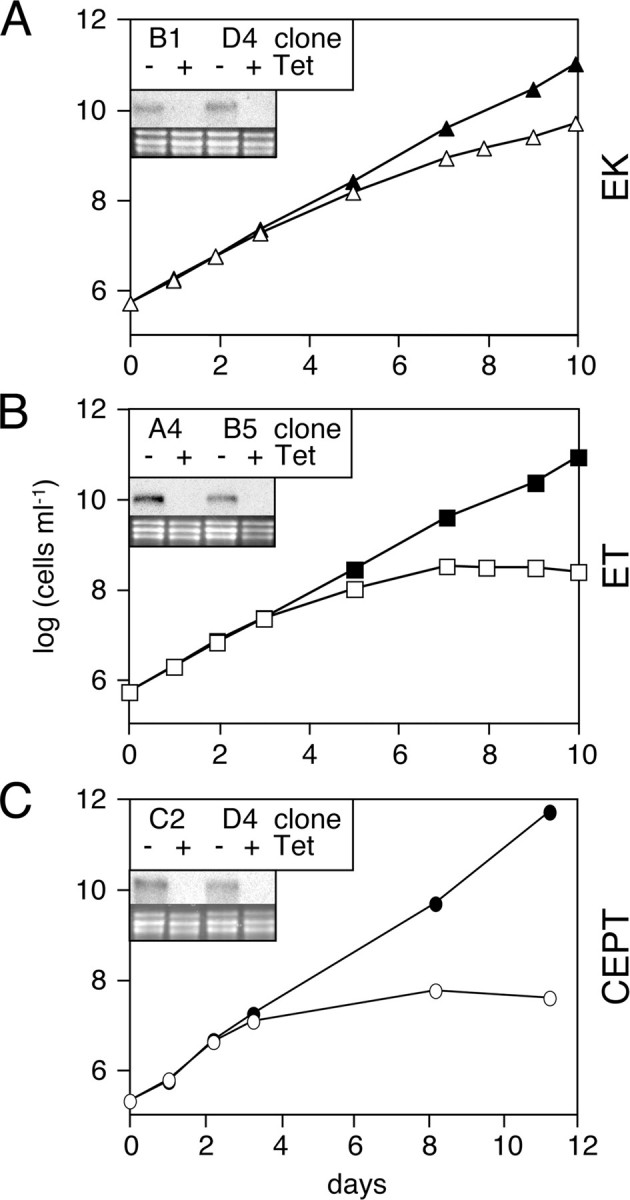

PE Biosynthesis in T. brucei Procyclic Forms Depends on the Kennedy Pathway—The T. brucei genome contains putative homologues for all three enzymes involved in PE biosynthesis by the Kennedy pathway. The sequence homologies between the deduced T. brucei and human proteins are 24, 45, and 28% for EK (Tb11.18.0017), ET (Tb11.01.5730), and CDP-alcohol phosphatidyltransferase (or CEPT; Tb10.6k15.1570), respectively. To determine the contribution of this pathway to the synthesis of bulk PE in T. brucei procyclic forms and to study the relative importance of the individual enzymatic reactions, we generated a series of tetracycline-inducible mutant parasites expressing double-stranded RNA against the three enzymes. We found that all clones tested show a clear growth phenotype after 3 days of induction compared with uninduced cells (Fig. 1). Interestingly, whereas growth of RNAi cells against ET and CEPT completely stopped in the presence of tetracycline, RNAi against EK only resulted in a marked reduction in the growth rate. Northern blot analyses showed that the respective RNAs were effectively degraded (Fig. 1, insets).

FIGURE 1.

Growth phenotype of RNAi cells targeting enzymes of the Kennedy pathway. Cumulative cell growth of T. brucei procyclic RNAi cells incubated in the absence (filled symbols) or presence (open symbols) of tetracycline to down-regulate EK (panel A), ET (panel B), or CEPT (panel C). The numbers represent mean values from two different clones. The insets show Northern blots of total RNA extracted after 3 days of incubation of cells in the absence (–) or presence (+) of tetracycline (Tet) and probed with 32P-labeled oligonucleotides used as inserts for the respective stem-loop vectors (top); rRNA is used as a loading control (bottom). Clones B1 (EK), B5 (ET), and D4 (CEPT) were selected for all subsequent experiments.

The biosynthesis of PE in T. brucei procyclic forms after induction of RNAi was analyzed by measuring incorporation of [3H]Etn into the phospholipid pool. Our results showed that labeling of cells in the absence of tetracycline results in incorporation of radioactivity into a single lipid class that co-migrates on TLC with a PE standard (result not shown; see also Ref. 28). The identification of the radioactive lipid as PE was confirmed by TLC in two additional solvent systems and its complete susceptibility to bacterial phospholipase C (results not shown). After 3 days of incubation in the presence of tetracycline to induce RNAi, incorporation of [3H]Etn into PE dropped to 15 or 22% of control levels when EK or ET, respectively, were down-regulated (Table 2). In contrast, RNAi against CEPT led to a slight increase in [3H]Etn incorporation into PE (Table 2). Although these results demonstrate changes in 3H-incorporation into PE after RNAi against individual enzymes of the Kennedy pathway, they do not provide information on possible changes in the absolute amounts of PE. Therefore, we determined the total PE levels in trypanosomes after RNAi against the three enzymes using TLC separation followed by lipid phosphorous analysis. The results show that RNAi against EK, ET, and CEPT resulted in a reduction in total PE of 38, 78, and 31%, respectively (Table 2). In contrast, PC levels were not significantly affected by down-regulation of PE synthesis, except for a 37% decrease in cells after RNAi against CEPT (Table 2). Together, these results demonstrate that down-regulation of EK, ET, and CEPT leads to a clear reduction in cellular PE levels, indicating that the Kennedy pathway represents the major route for PE synthesis in T. brucei procyclic forms.

TABLE 2.

EK, ET, and CEPT were down-regulated by RNAi

Individual clones were labeled with [3H]Etn during the last 18 h of culture, and phospholipids were extracted into CM and separated by TLC using solvent system 1. 3H-Labeled lipids were visualized and quantified by scanning the plate with a radioisotope detector. Quantification of PE and PC was done by lipid phosphorous determination.

| RNAi against | [3H]PEa | PEb | PCb |

|---|---|---|---|

| EK | 15.1 | 62.3 ± 11.5 | 106.5 ± 20.3 |

| ET | 22.7 | 22.5 ± 9.1 | 109.2 ± 21.1 |

| CEPT | 113.4 | 69.4 ± 13.0 | 63.8 ± 10.0 |

Incorporation of [3H]Etn into PE in cells after 3 days of RNAi against EK, ET, or CEPT, relative to control uninduced cells; numbers represent mean values from single scans from three independent experiments.

PE or PC content in cells after 5 days of RNAi against EK, ET, or CEPT, relative to control uninduced cells; numbers represent mean ± S.D. from seven to eight independent experiments.

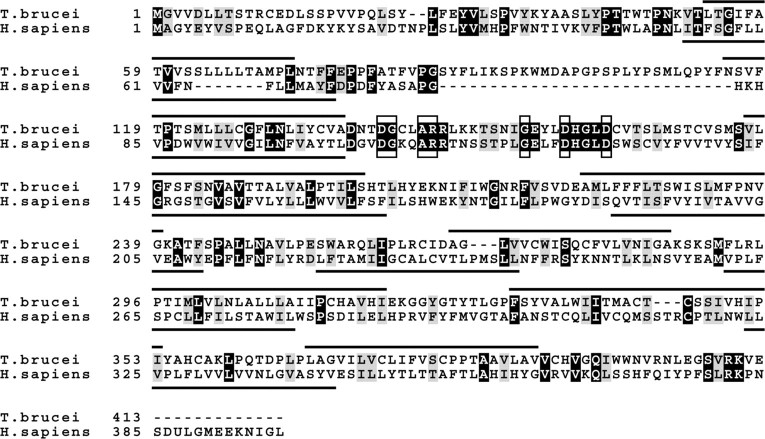

Identification of a Novel Enzymatic Activity in the PE Biosynthetic Pathway in T. brucei—Our observation that down-regulation of CEPT results in a reduction of cellular PE levels while incorporation of [3H]Etn into PE increased, suggests that the last step in the synthesis of PE by the Kennedy pathway may be mediated by a second activity that is not affected by RNAi against CEPT. In a recent report, a novel enzymatic activity was reported that specifically transfers Etn-P from CDP-Etn to diacylglycerol but is inactive against the choline analogues (13). We used the deduced amino acid sequence of this human EPT (Swiss-Prot accession number Q9C0D9) to search for a homologue in T. brucei and identified a predicted gene product with 16% homology on the amino acid level (Fig. 2). Similar sequences were also identified in the Trypanosoma cruzi and Leishmania major databases (results not shown). The T. brucei candidate EPT sequence shows 8 predicted transmembrane domains and contains the conserved CDP-alcohol phosphatidyltransferase motif (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

Amino acid sequence comparison between putative T. brucei ethanolamine-phosphotransferase and human ethanolamine-phosphotransferase. Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequences of putative ethanolamine-phosphotransferase (GeneDB accession number Tb10.389.0140) and human ethanolamine-phosphotransferase (Swiss-prot accession number Q9C0D9) was done using the ClustalW algorithm. White letters on black background indicate amino acid identity between the two sequences, black letters on gray background indicate similarity. The CDP-alcohol phosphatidyltransferase motif (DG(X)2AR(X)8G(X)3D(X)3D) is highlighted by boxes, predicted transmembrane domains are indicated with black bars.

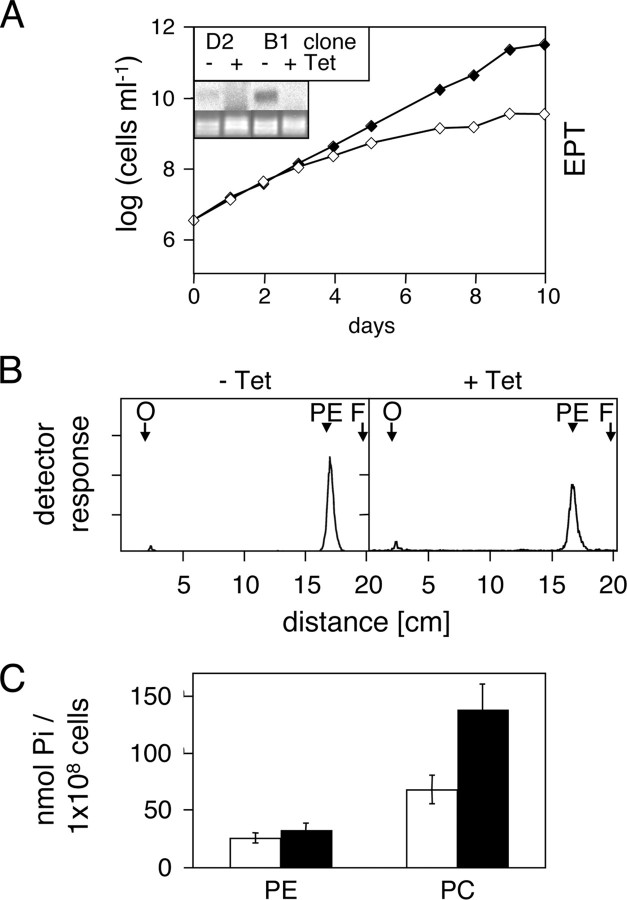

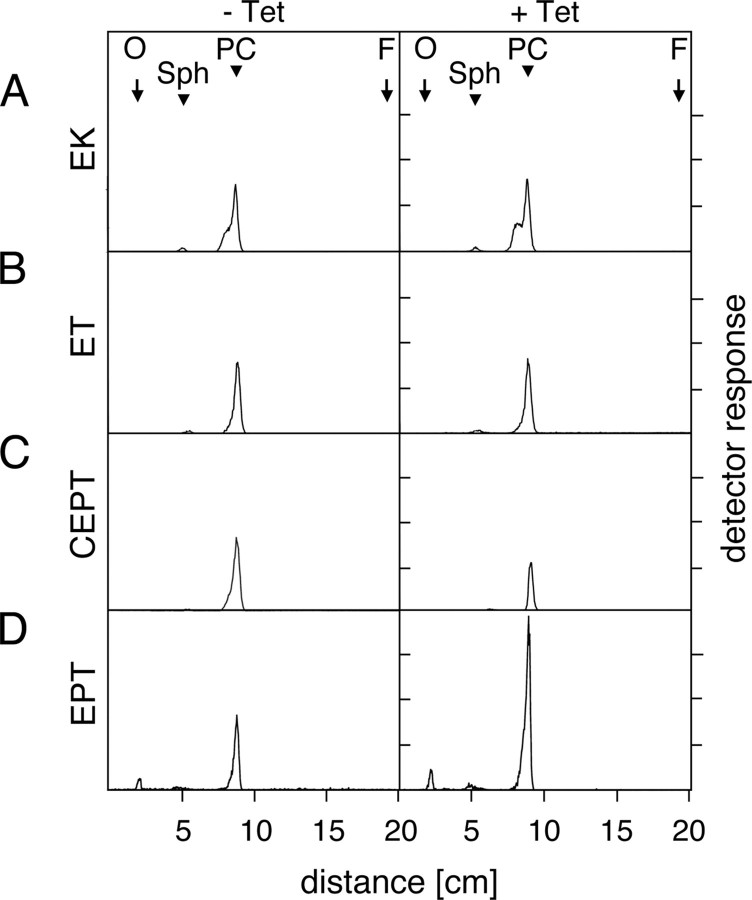

To test our hypothesis that this putative T. brucei EPT may be involved in the last step in PE synthesis by the Kennedy pathway, we generated RNAi cells expressing double-stranded RNA against EPT. The results show that down-regulation of EPT led to the disappearance of the corresponding RNA and a reduction in cell growth (Fig. 3A). In addition, we found that upon RNAi induction incorporation of [3H]Etn into PE slightly decreased, whereas total PE slightly increased compared with control cells (Fig. 3, B and C). Interestingly, RNAi of EPT caused a dramatic increase in the cellular PC levels by more than 100% (Fig. 3C). The unexpected increase in cellular PC after down-regulation of EPT was verified by labeling cells with [3H]choline. We found that addition of [3H]choline to T. brucei procyclic forms results in incorporation of radioactivity into two bands; the major product co-migrates with a PC standard run on the same TLC plate, whereas the minor band co-migrates with sphingomyelin (Fig. 4, A–D, left panels). Consistent with the phospholipid data shown in Table 2, down-regulation of EK or ET had no effect on incorporation of [3H]choline into PC (Fig. 4, A and B). Similarly, the 60% decrease in the generation of [3H]PC after RNAi against CEPT (Fig. 4C) is consistent with the observed decrease in total PC in these cells (Table 2). At present, it is unclear why the incorporation of radioactivity into PC is not completely blocked under these conditions; possible reasons may include a residual activity of CEPT, or the presence of a second enzyme that catalyzes the reaction. The dramatic increase in cellular PC content observed in RNAi cells against EPT (Fig. 3C) was paralleled by a massive increase in [3H]PC formation (Fig. 4D). Together, these findings show that down-regulation of EPT only slightly affects the total PE content in T. brucei procyclic forms but interferes dramatically with cellular PC levels.

FIGURE 3.

RNA-mediated gene silencing of putative T. brucei EPT. Panel A, cumulative cell growth of RNAi cells (mean values from two different clones) incubated in the absence (filled symbols) or presence (open symbols) of tetracycline to down-regulate EPT. The inset shows a Northern blot of total RNA extracted after 3 days of incubation of cells in the absence (–) or presence (+) of tetracycline (Tet) and probed with 32P-labeled oligonucleotides used as inserts for the respective stem-loop vector (top); rRNA is used as a loading control (bottom). Clone D2 was selected for all subsequent experiments. Panel B, biosynthesis of [3H]PE in RNAi cells incubated in the absence (–) or presence (+) of tetracycline for 3 days to down-regulate EPT. Cells were labeled with [3H]Etn during the last 18 h of culture, and phospholipids were extracted into CM and separated by TLC using solvent system 1. 3H-Labeled lipids were visualized by scanning the plate with a radioisotope detector. The arrows indicate the sites of sample application (O) and the solvent front (F), and the arrowheads the migration of a PE standard run on the same plate. The lanes contain extracts from equal cell equivalents. Panel C, cellular PE and PC contents in RNAi cells against EPT were determined after incubation in the absence (white bars) or presence (black bars) of tetracycline for 5 days. Phospholipids were extracted from cells and separated by one-dimensional TLC in solvent system 1. Each lane contained the extract from 4 × 108 cells. After visualization by iodine vapor, spots corresponding to PE and PC were scraped from the plates and quantified by phosphorous determination. The values represent mean ± S.E. from three independent experiments.

FIGURE 4.

Biosynthesis of [3H]PC in RNAi cells. T. brucei procyclic RNAi cells were incubated in the absence (–Tet) or presence (+Tet) of tetracycline for 3 days to down-regulate EK, ET, CEPT, and EPT. Individual clones were labeled with [3H]choline during the last 18 h of culture, and phospholipids were extracted and visualized as described in the legend to Fig. 3B. The arrows indicate the sites of sample application (O) and the solvent front (F), and the arrowheads the migration of PC and sphingomyelin (Sph) standards run on the same plate. The lanes of the individual clones contain extracts from equal cell numbers.

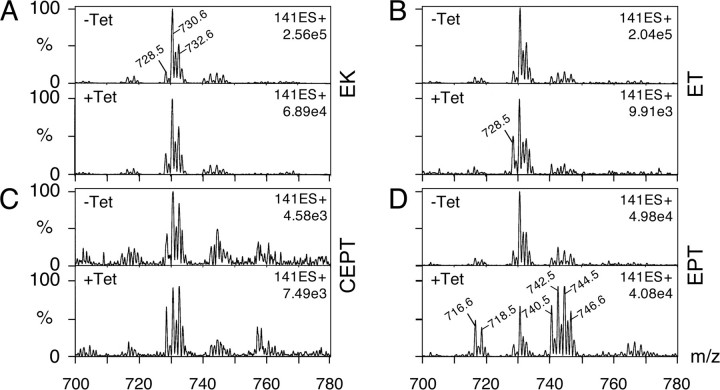

CEPT and EPT Are Responsible for the Synthesis of Different PE Molecular Species—The above results indicate that both CEPT and EPT are involved in PE synthesis in T. brucei procyclic forms. To study if the two enzymes generate different pools of PE, the molecular species composition of PE was analyzed in RNAi cells after down-regulation of CEPT or EPT. ES-MS-MS analysis of PE in uninduced cells shows that PE is composed of a set of alk-1-enylacyl-type molecular species in the [M + H]+ range 728.5–732.5, with 18:1/18:1-, 18:0/18:1-, and 18:0/18: 0-PE as the most prominent species (Fig. 5, A–D, top panels, and Table 3). The relative amounts of diacyl-type PE molecular species (peaks in the [M + H]+ range 716.5–718.5 and 740.5–746.5) are low compared with the ether-type species (Table 3). These results are in good agreement with a previous study (19). The PE molecular species composition was unchanged in parasites after down-regulation of EK, ET, or CEPT, except for a single species (C18:1/C18:1 alk-1-enyl-acyl-PE; [M + H]+ 728.5) that seems slightly increased in RNAi cells against EK, ET, and CEPT (Fig. 5, B and C, and Table 3). In contrast, the molecular species composition of PE was completely different in cells after down-regulation of EPT (Fig. 5D and Table 3). The diacyl-type species (peaks in the [M + H]+ range 740.5–746.6, i.e. 18:2/18:2-, 18:1/18:2-, 18:1/18:1-(and 18:0/18:2-), and 18:0/18:1-diacyl-PE), which represent a minor fraction in control cells (∼20% of total), clearly are the predominant species in EPT-depleted parasites (>50% of total). In contrast, the relative amounts of alk-1-enyl-acyl-PE species (peaks in the [M + H]+ range 726.4–732.6, i.e. 18:1/18: 2-, 18:1/18:1-(and 18:0/18:2-), 18:0/18:1-, and 18:0/18:0-alk-1-enyl-acyl-PE) in EPT RNAi cells decreased from >60% in uninduced to <20% in induced cells. These data indicate that CEPT and EPT are involved in the synthesis of different pools of PE in T. brucei procyclic forms.

FIGURE 5.

Analysis of PE molecular species. T. brucei procyclic RNAi clones were incubated in the absence (–Tet) or presence (+Tet) of tetracycline for 5 days to induce RNAi against EK (panel A), ET (panel B), CEPT (panel C), and EPT (panel D). Lipid extracts were analyzed for PE molecular species by ES-MS-MS in positive ion mode and scanning for neutral loss of 141 Da (Etn-P). The masses of the major species in control untreated cells are indicated in panel A; the masses of the species reflecting the major differences compared with control cells are indicated in panels B and D.

TABLE 3.

ES-MS-MS analysis of PE molecular species in trypanosomes after down-regulation of EK, ET, CEPT, and EPT

|

[M+H]+ |

Molecular species |

Abundance (% of total) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subclassa | Compositionb | Control | EK | ET | CEPT | EPT | |

| 702.5 | AA | C34:1 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 2.7 | 0.9 |

| 704.5 | AA | C34:0 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 3.3 | 0.5 |

| 714.5 | DA | C34:3 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 2.0 | 1.4 | 1.1 |

| 716.6 | DA | C34:2 | 3.2 | 2.2 | 3.5 | 4.4 | 8.0 |

| 718.5 | DA | C34:1 | 3.0 | 2.3 | 1.1 | 2.0 | 6.4 |

| 726.4 | AA | C36:3 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 0.5 |

| 728.6 | AA | C36:2 | 6.5 | 11.6 | 17.2 | 14.8 | 2.6 |

| 730.6 | AA | C36:1 | 38.0 | 37.5 | 33.4 | 20.6 | 11.2 |

| 732.6 | AA | C36:0 | 19.2 | 23.0 | 16.0 | 22.4 | 3.2 |

| 740.5 | DA | C36:4 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 4.7 | 1.2 | 11.3 |

| 742.5 | DA | C36:3 | 6.4 | 5.0 | 3.0 | 3.4 | 15.6 |

| 744.6 | DA | C36:2 | 6.2 | 4.6 | 4.9 | 4.9 | 16.3 |

| 746.6 | DA | C36:1 | 4.8 | 2.6 | 2.4 | 3.1 | 10.1 |

| 756.7 | AA | C38:2 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 2.1 | 1.1 |

| 758.4 | AA | C38:1 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 1.8 | 2.9 | 0.9 |

| 760.6 | AA | C38:0 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 4.6 | 0.7 |

| 764.5 | DA | C38:6 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 2.9 |

| 766.6 | DA | C38:5 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 3.2 |

| 768.5 | DA | C38:4 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 2.6 |

| 770.6 | DA | C38:3 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

AA, alk-1-enyl-acyl; DA, diacyl.

Total number of carbon atoms and double bonds.

Analysis of 3H-labeled acid-soluble metabolites showed that down-regulation of CEPT and EPT did not significantly change the amounts of [3H]Etn-P and CDP-[3H]Etn compared with uninduced cells (results not shown). In contrast, RNAi against ET resulted in accumulation of [3H]Etn-P and a complete lack of CDP-[3H]Etn (result not shown; see also Ref. 28).

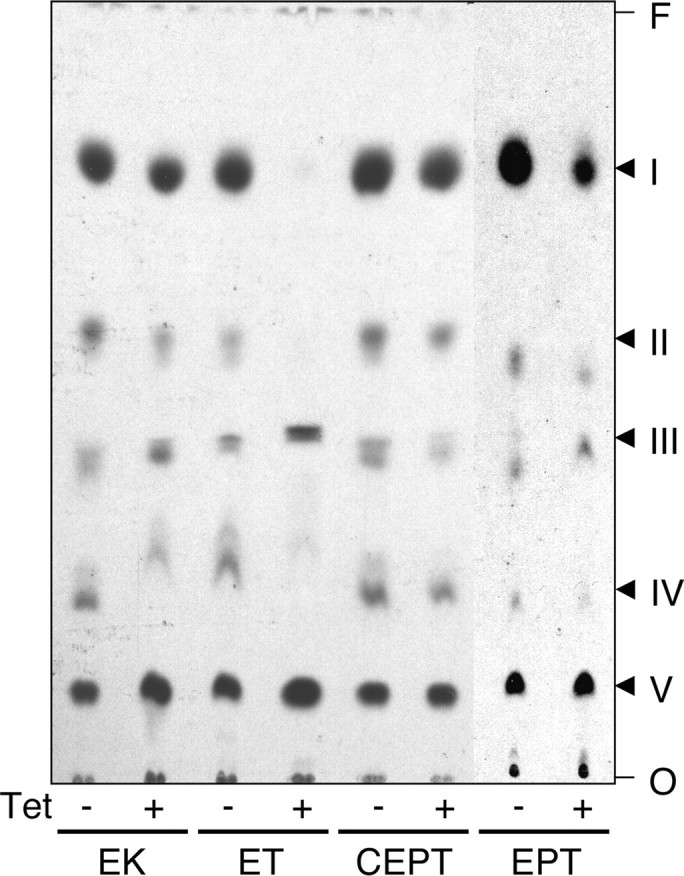

PS Is Generated by Head Group Exchange with PE in T. brucei Procyclic Forms—Our observation that the synthesis and cellular amount of PE is severely affected by down-regulation of EK or ET indicates that the Kennedy pathway provides most of the PE in T. brucei procyclic forms. However, because in many cells, the majority of PE is generated by decarboxylation of PS, we studied the importance of this pathway in T. brucei by labeling RNAi cells with [3H]serine. Incubation of control trypanosomes with [3H]serine showed that four major lipids were labeled (Fig. 6, bands labeled I–IV). Enzymatic and chemical treatment of the labeled CM extracts using phospholipase C, phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C, and mild base, in combination with the migration of appropriate lipid standards, identified the peaks as PE (I), PS (II), inositol phosphoceramide (III), and sphingomyelin (IV) (results not shown). The band designated V represents residual [3H]serine present in the CM extract.

FIGURE 6.

Analysis of [3H]serine-labeled lipids. RNAi against EK, ET, CEPT, and EPT was induced in T. brucei procyclic cells for 5 days by addition of tetracycline to the culture medium (+Tet). Uninduced cells served as controls (–Tet). Labeling with [3H]serine was done during the last 16–20 h of induction. Lipid extraction and separation by TLC was done as described in the legend to Fig. 3B. 3H-Labeled lipids were visualized by fluorography. The lanes contain extracts from equal cell equivalents. Individual spots were identified by co-migration with lipid standards and enzymatic and chemical treatment. I, PE; II, PS; III, inositol-phosphoceramide; IV, sphingomyelin; V, serine. The sites of sample application (O) and the solvent front (F) are indicated.

No major changes were seen in the [3H]serine labeling pattern after down-regulation of EK, CEPT, or EPT (Fig. 6). In contrast, RNAi against ET completely blocked incorporation of radioactivity into PS, indicating that [3H]PS in T. brucei procyclic forms can only be formed by head group exchange with PE, i.e. under conditions when PE synthesis is active. As a consequence of the lack of [3H]PS in ET RNAi cells labeled with [3H]serine, [3H]PE formation was also completely blocked (Fig. 6). To verify if the decrease in [3H]serine incorporation is also accompanied by a decrease in the PS content, CM extracts were separated by two-dimensional TLC and individual phospholipid classes were measured by lipid phosphorous determination. The results showed that in RNAi cells against ET the decrease in PE (from 18.5 to 4.6 nmol/108 cells) was paralleled by a decrease in PS (from 3.0 to 1.1 nmol/108 cells; mean values from two independent determinations). To compensate for the loss of PE and PS, the relative amounts of the other phospholipids slightly increased (PC, sphingomyelin, and cardiolipin) or remained unchanged (phosphatidylinositol, inositol phosphoceramide). The PS contents in parasites after RNAi against EK, CEPT, and EPT showed no differences to control uninduced cells (results not shown).

DISCUSSION

T. brucei procyclic and bloodstream forms contain all major phospholipid classes present in mammalian cells, with PC and PE comprising about 70% of total phospholipids (18, 19). However, except for the pathways for GPI (22) and phosphatidylinositol (25, 26) synthesis, little is known about the reaction sequences involved in phospholipid synthesis. Earlier reports, aimed at identifying the precursor of the Etn moiety in the GPI core structure (27) and to study Etn uptake and metabolism (34), showed that the CDP-Etn branch of the Kennedy pathway is functional in T. brucei bloodstream forms. However, the contribution of this pathway to bulk PE synthesis was not determined and no information is available on PE synthesis in T. brucei procyclic forms.

In the present report, we studied the synthesis of PE in T. brucei procyclic forms in culture using a series of RNAi cell lines and found that PE is exclusively synthesized by the CDP-Etn branch of the Kennedy pathway (Fig. 7). RNAi-mediated gene silencing of EK or ET, the first two enzymes of the Kennedy pathway, caused a severe reduction in the cellular PE content and a growth arrest of the mutant cells. These findings are surprising because bulk PE in eukaryotic cells is usually synthesized by decarboxylation of PS (1, 2, 10). In addition, our results seem to contradict previous reports showing that PE in T. brucei bloodstream and procyclic forms can also be generated by decarboxylation of PS (27, 34, 37), in particular because a homologue for PS decarboxylase is present in the T. brucei genome (gene accession number Tb09.211.1610). We confirmed the presence of an active PS decarboxylase in T. brucei procyclic forms by labeling trypanosomes with [3H]serine, which was readily converted to [3H]PE. However, the formation of [3H]PS, and accordingly the generation of [3H]PE from [3H]PS, was completely blocked when PE synthesis was inhibited by RNAi against ET, demonstrating that PS in T. brucei procyclic forms is synthesized by base exchange with PE and can subsequently be converted (back) to PE by PS decarboxylation. A gene homologue for PS synthase 2, catalyzing PE/PS base exchange, is present in the T. brucei genome (gene accession number Tb927.7.3760). In addition, we found that RNAi-mediated gene silencing of ET reduced the amount of PS to less than 1% of total phospholipid. Together, these results demonstrate that T. brucei procyclic forms are unable to synthesize PE de novo from PS and, thus, depend on the Kennedy pathway for PE synthesis.

FIGURE 7.

Synthesis of PE, PC, and PS in T. brucei procyclic forms. Putative genes for all enzymes depicted in the scheme are present in the T. brucei genome and are indicated in parentheses below the respective names of the enzymes. AAG, alk-1-enyl-acylglycerol; DAG, diacylglycerol.

In another protozoan parasite, Plasmodium falciparum, PE is converted to PC by methylation (38). Clearly, this pathway is not functional in T. brucei because incubation of cells with [3H]Etn shows no incorporation of label into PC (see also Refs. 27 and 34). In addition, we found no homologues of the corresponding methyltransferases in the T. brucei genome.

Unexpectedly, our results show that the last step in the CDP-Etn branch of the Kennedy pathway is mediated by two separate activities in T. brucei procyclic forms. Based on current schemes for PE and PC synthesis by the Kennedy pathway, transfer of CDP-Etn and CDP-choline to diradylglycerol is mediated by CEPT, an enzyme showing dual specificity for Etn and choline metabolites (2). Accordingly, we found that down-regulation of T. brucei CEPT in procyclic forms resulted in a moderate decrease in both the cellular PE and PC levels and the cells showed a reduction in the growth rate. In contrast, incorporation of [3H]Etn into CEPT-depleted cells increased rather than decreased, suggesting that a second pool of PE may exist that is supplied by a different enzyme. Based on a recent report describing the identification of the first human EPT (13), we identified a gene homologue in T. brucei and down-regulated its expression by RNAi. Interestingly, although gene silencing of T. brucei EPT showed little effect on PE levels, it completely changed the molecular species composition of PE from mostly alk-1-enyl-acyl-type species to mostly diacyl-type PE. In addition, it caused a dramatic increase in the cellular PC content. We interpret these findings as follows: bulk PE in T. brucei procyclic forms is synthesized by EPT, which is PE-specific and generates the ether-type molecular species that make up most of the PE in T. brucei procyclic forms (see also Ref. 19). Because the first steps in ether lipid biosynthesis in T. brucei occur in special organelles called glycosomes (39), we hypothesize that EPT, a protein containing 8 predicted transmembrane domains, is embedded into the glycosomal membrane. In contrast, bulk PC in T. brucei procyclic forms is synthesized by CEPT, which has been found to associate with the endoplasmic reticulum in human cells (40). Experiments to study the localization of EPT and CEPT in T. brucei procyclic forms are currently under way. Because T. brucei CEPT shows dual specificity for CDP-Etn and CDP-choline, it may take over PE production in the case when EPT is absent, i.e. down-regulated by RNAi. However, due to its (non-glycosomal) localization, CEPT will transfer CDP-Etn not to ether-type lipid precursors but to diacylglycerols, resulting in mostly diacyl-PE species that resemble the predominantly diacyl-type PC species in T. brucei procyclic forms (19). In addition, because CEPT shows higher affinity toward CDP-choline than CDP-Etn, increased CEPT activity results in the elevated PC content we find in these cells. This interpretation is in line with a previous report showing that two different enzyme activities are responsible for the synthesis of alk-1-enyl-acyl-PE and diacyl-PE in rabbit heart membranes (41). Separate pools of PE consisting of different molecular species have also been reported in other mammalian cells (42) and yeast (43).

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Schneider for plasmids and cell lines. P. B. thanks C. Nobs and the reviewers for valuable input.

The work was supported in part by Swiss National Science Foundation Grant 3100A0-116627 (to P. B.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: PC, phosphatidylcholine; PE, phosphati-dylethanolamine; CDP-Etn, CDP-ethanolamine; Etn, ethanolamine; Etn-P, ethanolamine-phosphate; EK, ethanolamine kinase; ET, ethanolamine-phosphate cytidylyltransferase; CEPT, choline/ethanolamine-phosphotransferase; CM, chloroform:methanol; TLC, thin layer chromatography; EPT, ethanolamine-specific phosphotransferase; PS, phosphatidylserine; GPI, glycosylphosphatidylinositol; RNAi, RNA interference; ES-MS-MS, electrospray tandem mass spectrometry; MOPS, 4-morpholinepropanesulfonic acid.

References

- 1.Vance, J. E., and Vance, D. E. (2004) Biochem. Cell Biol. 82113 –128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vance, J. E. (2008) J. Lipid Res. 491377 –1387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dowhan, W. (1997) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 66199 –232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tillman, T. S., and Cascio, M. (2003) Cell Biochem. Biophys. 38161 –190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Munro, S. (2004) Nat. Cell Biol. 6469 –472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Matteis, M. A., and Godi, A. (2004) Nat. Cell Biol. 6487 –492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang, X., Devaiah, S. P., Zhang, W., and Welti, R. (2006) Prog. Lipid Res. 45250 –278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Voelker, D. R. (2003) J. Lipid Res. 44441 –449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carman, G. M., and Henry, S. A. (1999) Prog. Lipid Res. 38361 –399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Birner, R., and Daum, G. (2003) Int. Rev. Cytol. 225273 –323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kennedy, E. P., and Weiss, S. B. (1956) J. Biol. Chem. 222193 –214 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bakovic, M., Fullerton, M. D., and Michel, V. (2007) Biochem. Cell Biol. 85283 –300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horibata, Y., and Hirabayashi, Y. (2007) J. Lipid Res. 48503 –508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanfer, J., and Kennedy, E. P. (1964) J. Biol. Chem. 2391720 –1726 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Voelker, D. R. (1984) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 812669 –2673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arikketh, D., Nelson, R., and Vance, J. E. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 28312888 –12897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nikawa, J. I., and Yamashita, S. (1981) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 665420 –426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dixon, H., and Williamson, J. (1970) Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 33111 –128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patnaik, P. K., Field, M. C., Menon, A. K., Cross, G. A. M., Yee, M. C., and Bütikofer, P. (1993) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 5897 –106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vial, H. J., Eldin, P., Tielens, A. G. M., and van Hellemond, J. J. (2003) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 126143 –154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Hellemond, J. J., and Tielens, A. G. (2006) FEBS Lett. 5805552 –5558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferguson, M. A. J. (1999) J. Cell Sci. 1122799 –2809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Orlean, P., and Menon, A. K. (2007) J. Lipid Res. 48993 –1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferguson, M. A. J. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 9710673 –10675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin, K. L., and Smith, T. K. (2006) Biochem. J. 396287 –295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin, K. L., and Smith, T. K. (2006) Mol. Microbiol. 6189 –105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Menon, A. K., Eppinger, M., Mayor, S., and Schwarz, R. T. (1993) EMBO J. 121907 –1914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Signorell, A., Jelk, J., Rauch, M., and Bütikofer, P. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 28320320 –20329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wirtz, E., Leal, S., Ochatt, C., and Cross, G. A. (1999) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 9989 –101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brun, R., and Schönenberger, M. (1979) Acta Trop. 36289 –292 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bochud-Allemann, N., and Schneider, A. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 27732849 –32854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chomczynski, P., and Sacchi, N. (2006) Nat. Protoc. 1581 –585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bütikofer, P., Ruepp, S., Boschung, M., and Roditi, I. (1997) Biochem. J. 326415 –423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rifkin, M. R., Strobos, C. A. M., and Fairlamb, A. H. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 27016160 –16166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bütikofer, P., Lin, Z. W., Kuypers, F. A., Scott, M. D., Xu, C., Wagner, G. M., Chiu, D. T. Y., and Lubin, B. (1989) Blood 731699 –1704 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rouser, G., Fleischer, S., and Yamamoto, A. (1970) Lipids 5494 –496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guler, J. L., Kriegova, E., Smith, T. K., Lukes, J., and Englund, P. T. (2008) Mol. Microbiol. 671125 –1142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pessi, G., Choi, J. Y., Reynolds, J. M., Voelker, D. R., and Mamoun, C. B. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 28012461 –12466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Opperdoes, F. R. (1984) FEBS Lett. 16935 –39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Henneberry, A. L., Wright, M. M., and McMaster, C. R. (2002) Mol. Biol. Cell 133148 –3161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ford, D. A. (2003) J. Lipid Res. 44554 –559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bleijerveld, O. B., Brouwers, J. F., Vaandrager, A. B., Helms, J. B., and Houweling, M. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 28228362 –28372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bürgermeister, M., Birner-Grunberger, R., Heyn, M., and Daum, G. (2004) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1686148 –160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]