Abstract

Analysis of RNA editing in plant mitochondria has at least in vitro been hampered by very low activity. Consequently, none of the trans-acting factors involved has yet been identified. We here report that in vitro RNA editing increases dramatically when additional cognate recognition motifs are introduced into the template RNA molecule. Substrate RNAs with tandemly repeated recognition elements enhance in vitro RNA editing from 2–3% to 50–80%. The stimulation is not influenced by the editing status of a respective RNA editing site, suggesting that specific recognition of a site can be independent of the edited nucleotide itself. In vivo, attachment of the editing complex may thus be analogously initiated at sequence similarities in the vicinity of bona fide editing sites. This cis-acting enhancement decreases with increasing distance between the duplicated specificity signals; a cooperative effect is detectable up to ∼200 nucleotides. Such repeated template constructs promise to be powerful tools for the RNA affinity identification of the as yet unknown trans-factors of plant mitochondrial RNA editing.

RNA editing in plant mitochondria and chloroplasts changes mostly C to U nucleotide identities in mRNAs and tRNAs as part of the manifold post-transcriptional RNA maturation processes. For specific recognition by the RNA editing activity, usually only ∼20–40 nucleotides are necessary upstream, and very few, if any, nucleotide identities downstream of a given editing site are required (1, 2).

The recent development of reliable in vitro RNA editing activities for chloroplasts (3–6) and mitochondria (7) has accelerated progress toward elucidating the details of cis-requirements and the mode of editing site recognition. These assays are, however, often limited by the efficiency of the in vitro reaction. For chloroplasts as well as for mitochondria, only some of the in vivo editing sites are detectably altered in vitro. A recent comprehensive investigation of in vitro editing of editing sites in tobacco chloroplasts revealed that only approximately half of the in vivo sites are edited in vitro, and many of these are at levels too low to allow in vitro analysis in any detail (8).

For plant mitochondria, we have made analogous observations with an in vitro RNA editing system from cauliflower inflorescences (Brassica oleracea) (9). In these assays in depth analysis of RNA editing is at many sites hampered by the notoriously low efficiency, which is for most sites below the levels of detection. Nevertheless those sites that could be investigated in some detail provided considerable information about the cis-requirements for site specificity (7, 10–12). A central element within the 20 nucleotides upstream of an editing site is usually sufficient to support in vitro editing.

The numerous RNA editing sites within a given mRNA raise the question of how the editing machinery can address all of these sites efficiently (13). Partially edited sites in the steady state plant mitochondrial mRNA population (14, 15) and sites partially or completely unedited in in organello assays (16, 17) are distributed randomly through the RNA molecules. These observations suggest a random approach of the editing complex to the RNA rather than a linear progression of the recognition factors along the template RNA.

To investigate this question and to determine the window of RNA sequence probed by the RNA editing complex, we analyzed the influence of additional attachment sites on a monitored RNA editing site at varied distances. Surprisingly additional cis-elements in vitro strongly enhance editing in a distance-dependent cooperation. The influence of duplicated attachment sites manifests in boosting in vitro editing from 2–3% to 50–80%. Consequently such template RNA constructs may be able to activate hitherto in vitro untestable editing sites to levels that can be analyzed.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Preparation of Mitochondrial Extracts—Heads of cauliflower were purchased at local markets. Approximately 900 g of the top tissues of the inflorescences were harvested, manually chopped into small pieces, and homogenized in a blender. Mitochondria were purified by differential centrifugation steps and a Percoll gradient (18). Lysis of the mitochondria, dialysis, and storage of the mitochondrial preparations were as described previously (18).

Generation of RNA Substrates—DNA clones were constructed in an adapted pBluescript SK+ to allow run-off transcription of the editing template RNA as described (19). Duplication of specific sequence regions was achieved by preligating PCR amplification products of the respective recognition sequences of the editing sites before a second ligation step together with the vector DNA. Identification of clones with duplicated mitochondrial sequences was done by screening respective analytical PCR products from clone colonies for their sizes. The exact sequences of the cloned constructs were all verified by direct sequence analysis.

In Vitro RNA Editing Reactions—In vitro RNA editing reactions were performed as described (18, 19). After incubation, template sequences were amplified by RT-PCR,3 the upstream primer being labeled with the Cy5 fluorophor. RNA editing activity was detected by mismatch analysis employing the thymine DNA glycosylase (TDG) enzyme activity (Trevigen). The TDG-treated fragments were separated, and the Cy5 fluorescence was scanned and displayed using an ALF express DNA sequencer (GE Healthcare). The in vitro RNA editing reaction was quantified by comparing the areas under the peaks of the cleaved and uncut DNA fragments (18).

When in vitro RNA editing was found to be efficient, direct sequence analysis of the RT-PCR products amplified from the incubated RNA substrate molecules was done, and the ratio of T to C signals was estimated. For the analysis of individual product RNA molecules, the RT-PCR DNA molecules were cloned by standard procedures and sequenced individually.

RESULTS

Strategy—To investigate how the RNA editing protein(s) and/or complex of proteins are attracted to their specific target sites in the substrate RNA molecule, we designed a family of RNA templates in which additional homologous specificity regions are present at various distances from a given site. The editing site is incorporated with its own cognate attachment region, the native cis-specificity element at the correct in vivo distance. This arrangement allows determination of the influence of the second, disconnected specificity region on the editing level at the monitored editing event. The in vitro editing activity at this site will display an increase in editing above the level of the native single copy element of ∼2–3% as well as a decrease below this level. The latter outcome can be expected in analogy to competition experiments, in which trans-added specificity regions on other RNA molecules compete with the trans-recognition factors and diminish the in vitro reaction at the monitored molecules (11, 12).

Tandem Duplication of a cis-Element Increases the in Vitro RNA Editing Activity—To focus the effect of the duplicated specificity elements on one editing site and to investigate the importance of the editing site itself for the specificity contact, the upstream copy of the cis-element was inserted in this template RNA without its native editing site (Fig. 1). A bona fide RNA editing site is thus only present downstream of the second copy of the two anchor regions. To allow only site atp4–248 of the three editing sites present in vivo in this cluster at nucleotides 248, 250, and 251 in the atp4 mRNA from cauliflower mitochondria to be altered in vitro, nucleotides required for editing of the other sites were altered (12).

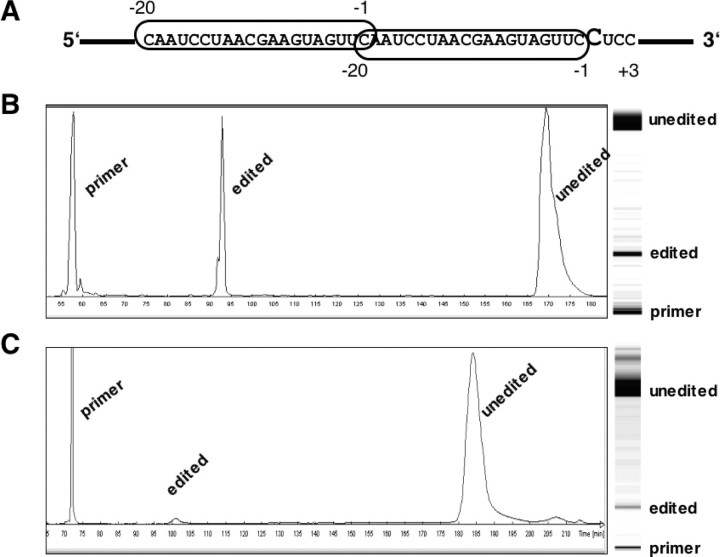

FIGURE 1.

Analysis of in vitro editing with a template construct containing two copies of an RNA editing specificity element in tandem. A, structure of the RNA editing template RNA. The specificity element (circled) of the atp4 coding sequence from cauliflower (B. oleracea) mitochondria covers the 20 nucleotides immediately upstream of the atp4–248 C from –20 to –1 (12) but not the edited nucleotide itself. The downstream copy is followed by the in vivo editing sites atp4–248 to atp4–251, after which the sequence has been altered to focus editing on site atp4–248, here at nucleotide position 0 (shown in a larger font). The bold line represents bacterial sequences from the cloning vector. B, fluorescence profile and gel image of the editing products after in vitro incubation and TDG treatment. Approximately 50% of the RNA template molecules have been altered from C to U moieties at the single editing site. C, for comparison, the fluorescence profile and the gel image of the editing products generated by in vitro incubation and TDG treatment of a template RNA containing a single copy of the atp4 specificity element and the cognate editing sites are shown. In this template ∼2–3% of RNA editing site atp4–248 have been altered from C to U moieties.

Surprisingly, a large increase of the editing activity is observed (Fig. 1). In this construct ∼50% of all template molecules are altered in vitro at the monitored site. For comparison, the single copy template yields ∼2–3% editing in vitro (Fig. 1).

The Presence of an Editing Site, Not the Editing Reaction as Such, Can Influence Attraction of the RNA Editing Complex—To investigate the functional role of the editing site on the attraction and assembly of the RNA editing machinery, a template RNA was tested in which both copies of the atp4 specificity region contain their cognate editing sites (Fig. 2). The upstream copy contains three nucleotides downstream of editing site atp4–248 (Fig. 2, templates 3 and 4) to focus on this site and to inactivate the editing site at atp4–251 (site atp4–250 is never seen edited in vitro) (12). In the downstream copy the native nucleotides are included up to +5 to activate site atp4–251.

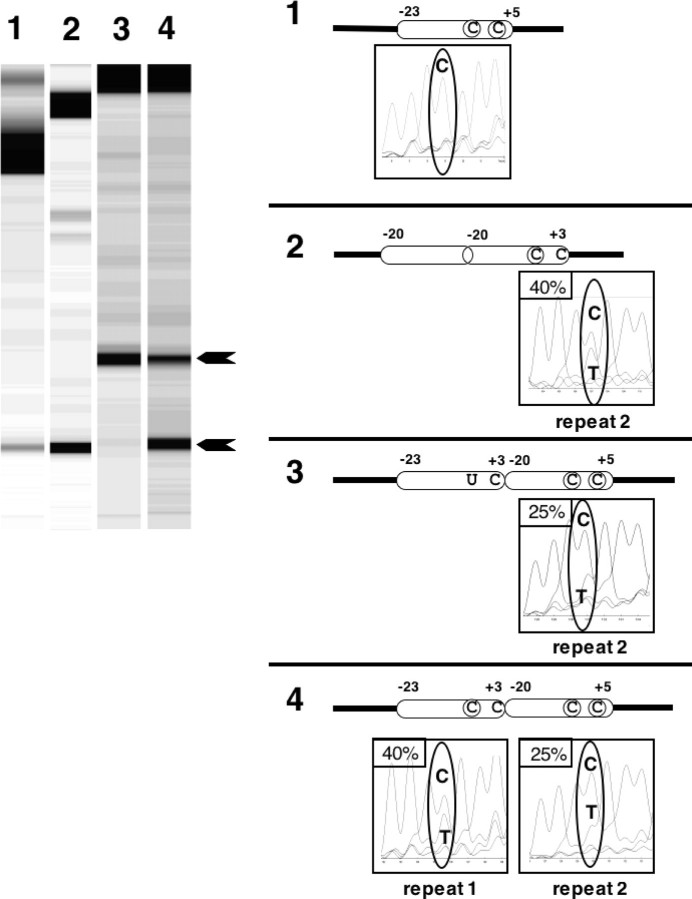

FIGURE 2.

Probing the influence of the edited nucleotide on the processivity of in vitro RNA editing. The left panel shows the gel image of the editing products after in vitro incubation and TDG treatment of four different template RNAs. The structures of the RNA editing template RNAs are schematically depicted on the right with the corresponding sequence tracings of the cDNA population after the in vitro reaction. The editable sites are shown as a circled C, and uneditable C and U in the positions of editing sites are indicated as plain letters in the oblongs that symbolize the specificity regions. Template 1 is the wild type arrangement with a single copy of the specificity element and the two editable sites atp4–248 and atp4–251 (circled) of the atp4 coding sequence from cauliflower (B. oleracea) mitochondria as a control. RNA template 2 is identical to the one investigated in Fig. 1 with an editable atp4–248 only in the downstream duplicated specificity region as a control for the lysate activity. Templates 3 and 4 contain two copies of this specificity element in tandem. The upstream copy covers nucleotides –23 to +3 relative to atp4–248, and the second copy covers nucleotides –20 to +5 (12). In the upstream copy only editing site atp4–248 can be edited in vitro, which is in construct 3 included as a pre-edited U and in construct 4 as a C that can be edited. The gel image of the editing products generated by in vitro incubation and TDG treatment of template 1 with a single copy of the specificity element shows the expected signal of 2–3% editing (lower arrowhead). This is not enough to be detectable in the corresponding sequence analysis (circled). The assay with template 2 as a control of the mitochondrial extract preparation is edited in this mitochondrial lysate to ∼40%. Templates 3 and 4 yield ∼25% in vitro editing at the downstream copy, which is detectable in the sequence tracings underneath the corresponding element on the right (marked as repeat 2). In template 4, ∼40% of the C at RNA editing site atp4–248 in the upstream copy (repeat 1) have been altered from C to U moieties. Site atp4–251 in Repeat 2 is always too weakly edited to be detectable in the sequence tracings.

The presence of the upstream editing site lowers the enhancing effect of the duplicated editing element: In this mitochondrial lysate preparation, the editing rate in the control template without the upstream editing site is ∼40% (Fig. 2, template 2), comparable with the 50% with the lysate in Fig. 1. The corresponding site in the downstream copy in this RNA template is edited to 25% (Fig. 2, template 4), which still represents a considerable enhancing effect in comparison with the 2–3% editing of the single copy element (Fig. 2, template 1) but is lower than the 40% seen without the upstream site. The diminished enhancement could be due to the increased distance or to a specific binding effect of the editing site sequence.

To determine a potential influence of the editing reaction as such, the next construct contains the upstream copy with the editing site pre-edited as a U (Fig. 2, template 3). The editing rate observed is ∼25%, similar to the editing efficiency at the corresponding site in the template with the upstream C (Fig. 2, template 4). This observation suggests that the actual editing process has little influence on the rate of the association and dissociation of the RNA editing complex.

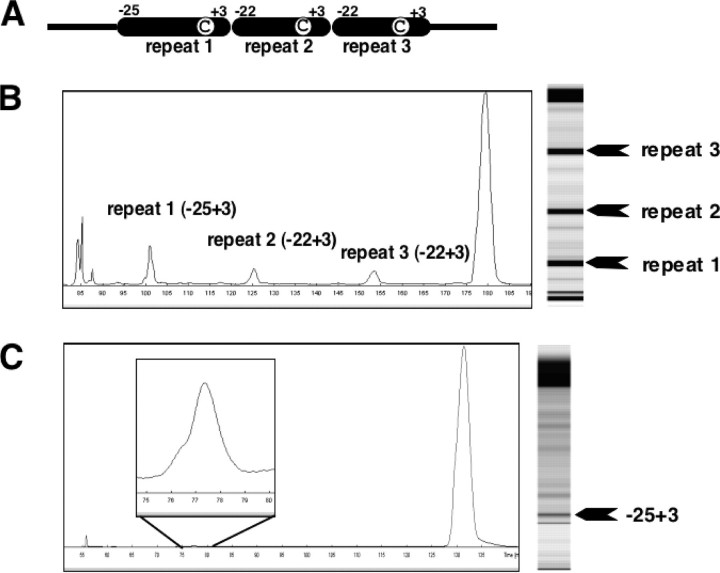

RNA Editing Is Enhanced by Amplification of the Specificity Elements Also at an Editing Site in the atp9 mRNA—To investigate the general validity of the enhancing effect of such recognition element duplications on an editing site, an RNA construct was tested in which the first editing site in the atp9 mRNA (atp9–20) and its cognate specificity element are present in three copies (10). With this template RNA, an analogous increase of the in vitro RNA editing activity is indeed observed in the amplified atp9 editing sites (Fig. 3), suggesting that this effect of facilitating a cooperation between neighboring editing sites is an intrinsic property of the RNA editing process and not specific to the atp4 recognition factor. The enhancing effect is with a 20-fold boost from ∼1% of the single copy to ∼20% in the amplified elements comparable with the one observed with the atp4 editing site. The difference in overall efficiency may reflect variant properties of the individual specificity factors of different sites. Such site-specific differences in in vitro editing have also been seen in chloroplast assays (8).

FIGURE 3.

Assays of in vitro editing in a template RNA with three tandem copies of an atp9 mRNA editing specificity element. A, structure of the RNA editing template RNA. The specificity element (symbolized by the black oblongs) of the atp9–20 editing site in the atp9 mRNA from cauliflower (B. oleracea) mitochondria amplified here covers the 22 (respectively 25 in the first repeat) nucleotides around atp9–20 from –22/–25 to +3 (9). The locations of the editing sites are displayed by the positions of the encircled Cs. B, fluorescence profile and gel image of the editing products after in vitro incubation and TDG treatment. Approximately 20% of the RNA template molecules have been altered from C to U moieties at the first editing site of the triple repeat. C, as a reference, fluorescence profile and gel image are shown of the editing products resulting from the in vitro incubation and TDG treatment of a wild type template RNA with a single copy of the atp9–20 specificity element and the editing site between –25 and +3. In this template ∼1% of the C nucleotides at the RNA editing site has been altered to U.

Implications for the RNA Editing Process—The observed enhancement of in vitro RNA editing by an additional copy of the specificity region has further reaching implications for the RNA editing process in plant mitochondria in general. The surprisingly massive increase of the editing activity by the duplicated cis-recognition sequence implies that one of the limiting factors in RNA editing can be the physical properties of gaining access to the cognate cis-region. The generally low in vitro editing efficiency observed in assays with template RNAs containing a single copy of the specificity region can be interpreted as being caused by a limiting concentration of the trans-factor(s). Competition in trans by an excess of additional RNA molecules containing this specific binding sequence cannot further narrow down the actual cause of the resulting lowered editing activity.

The in vitro assays reported here with duplicated specificity elements suggest that the availability of trans-factor(s) is not actually rate-limiting. Of course, they could still be comparatively few, and the improved attraction of the duplicated specificity region could help to overcome the difficulty of the bimolecular reaction partners finding each other in relatively low concentrations.

Multiple Specificity Regions Further Increase in Vitro RNA Editing and Reach the Limitation of Available trans-Factors—To further investigate the interplay of limited access and/or limited quantity of the specificity elements at RNA editing sites, RNA templates were designed that contain four copies of the atp4 specificity element with the cognate editing sites included in all four copies (Fig. 4). This template yields another rather dramatic increase of the in vitro RNA editing efficiency (Fig. 4B) with up to 80% of the cytosines at some editing sites in the RNA template converted in vitro to uridines.

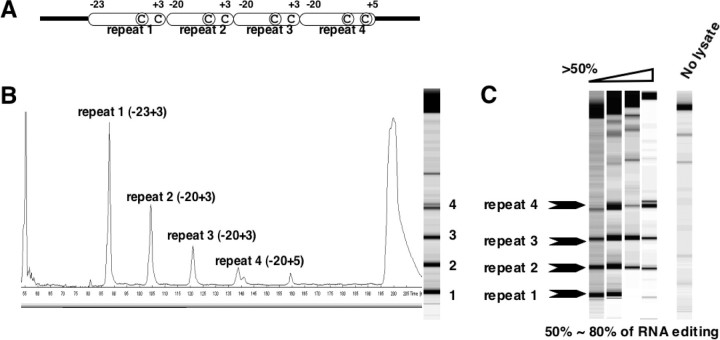

FIGURE 4.

Template RNAs with four times amplified recognition regions of an atp4 site are tested for in vitro RNA editing. A, the atp4 derived template RNA analyzed for RNA editing contains in tandem four copies of the recognition region (oblong boxes represent the sequence boxed in Fig. 1A) and the respective editable sites (circled C). The terminal cluster contains the wild type sequence up to nucleotide +5 to allow monitoring of the two editing sites at atp4–248 and atp4–251 (both shown circled). B, gel image and scan of the RNA editing products after in vitro incubation and TDG treatment. Approximately 50% of the RNA template molecules have been altered from C to U moieties at each of the editing sites. The signal diminishes progressively 5′ to 3′ because of the 5′ incisions by the TDG and the resulting loss of the 5′ fluorescent label for the downstream editing sites. C, efficient binding of the trans-factors exhausts the available trans-factors in some mitochondrial lysates. Different mitochondrial preparations show 80% nucleotide conversion at each of the editing sites in some extracts (right lane), 50% in another mitochondrial preparation (left lane) and intermediate levels with other lysates from cauliflower mitochondria (center lanes). In the control lane (No lysate), the lysate treatment was omitted. Only the full-length RT-PCR product uncut by the TDG and the background are detectable.

The limiting parameter now seems to be indeed the quantity of the trans-factors of specificity in the mitochondrial lysates rather than the access to the template RNA. Different lysate preparations from individual cauliflower heads (which we routinely test to corroborate the reproducibility of the results) generally vary in their RNA editing activity at single copy wild type template RNAs. Individual lysates also yield different activities with this template containing four tandem repeats (Fig. 4C). Although some lysates show ∼50% in vitro editing at the first repeat, the most active lysates reach ∼80%. Intermediate activities are seen for other mitochondrial lysate preparations.

To evaluate and corroborate the estimations of the TDG-generated fragments (Fig. 4B) by an independent method, the RT-PCR products of two such assays were cloned and sequenced. From an experiment with 50% in vitro editing estimated from the TDG reaction, 9 of 19 randomly selected clones were unedited. From a second assay with ∼90% editing by the TDG determinations, 31 cDNA clones were sequenced, of which only two were entirely unedited. Table 1 summarizes these cDNA clones and shows that most clones are edited at several sites.

TABLE 1.

Analysis of individual cDNA clones obtained from in vitro RNA editing reactions with an RNA template containing a four times repeated cis-element

The table lists the editing status of cDNA clones from two independent assays with two different mitochondrial lysates. A C represents an unedited position, and a T marks a successfully edited position. In Repeat 4, two nucleotides of the cluster of editing sites can be edited, which is indicated by the two nucleotides separated by a slash. In Assay 1, 50% in vitro editing was calculated from the TDG reaction. Confirming this, approximately half of the randomly selected cDNA clones (9 of 19) show no editing. In Assay 2, ∼90% editing was indicated by the TDG analysis. Of the 31 clones investigated for these cloned cDNAs, only two clones have no editing site altered.

| Repeat 1 | Repeat 2 | Repeat 3 | Repeat 4 | No. of clones | Editing events | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assay 1 | T | T | T | T/T | 1 | 5 |

| T | T | T | T/C | 2 | 4 | |

| T | T | T | C/C | 4 | 3 | |

| C | T | T | T/C | 1 | 3 | |

| T | C | C | C/C | 2 | 1 | |

| C | C | C | C/C | 9 | 0 | |

| Assay 2 | T | T | T | T/T | 1 | 5 |

| T | T | T | T/C | 1 | 4 | |

| T | T | T | C/T | 1 | 4 | |

| T | T | T | C/C | 16 | 3 | |

| T | T | C | C/C | 4 | 2 | |

| C | T | T | C/C | 2 | 2 | |

| T | C | T | C/C | 2 | 2 | |

| C | C | T | C/C | 2 | 1 | |

| C | C | C | C/C | 2 | 0 |

Although in all of the cDNA clones from both assays, one editing site has been altered in only four cDNA clones, and two sites have been changed in eight clones, three or more sites have been edited in the remaining 27 clones (Table 1). The site edited the slowest is site atp4–251 in the terminal repeat 4 (Fig. 4A). This may be due to the sterically different access of this site, which is reached either through a physical stretching of the editing activity bound to the upstream specificity region or requires a shift of this activity along the RNA by three nucleotides (12). It is also possible that an entirely different trans-factor is involved in the identification of this site.

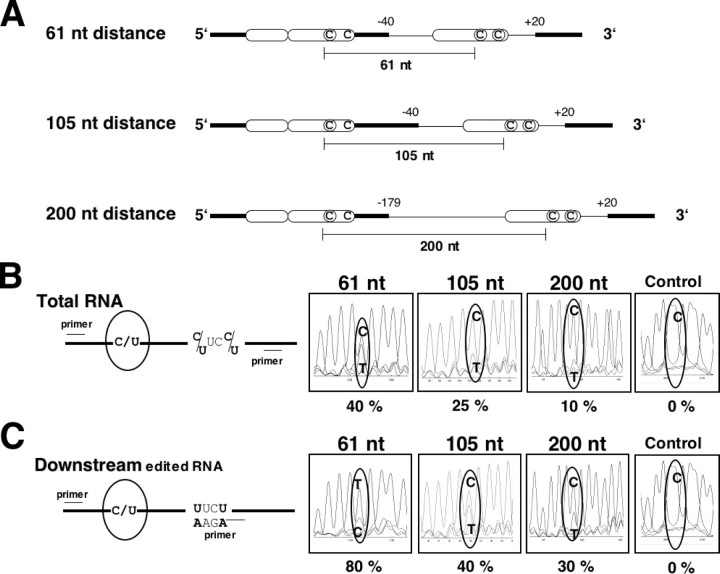

Lateral Influence of a Recognition Sequence Is Distance-dependent—To investigate the distance over which the RNA editing complex can be influenced laterally on the substrate RNA molecule, template RNAs with extended spacings between two repeated elements were constructed. In the first construct 40 extra nucleotides increase the distance between a set of upstream tandem repeats (A tandem repeat of 20 nucleotides implies a distance of 20 nucleotides between editing sites as in Fig. 1) and an additional downstream sequence motif to 61 nucleotides (Fig. 5A). The second of the tandem repeats and the distant downstream repeat contain the native editing sites atp4–248 to be able to determine the influence of the respective cis-elements. When the total cDNA population obtained after the in vitro editing reaction was sequenced, ∼25% of the downstream site were found altered (data not shown).

FIGURE 5.

RNA editing of RNA molecules with two specificity elements spaced 61, 105, or 200 nucleotides apart. A, the RNA editing template constructs contain two copies of editable atp4 sites (each indicated by a circled C) at a distance of 61 nucleotides (top), 105 (center), or 200 nucleotides (bottom). For the upstream editing site arrangement, the specificity region (white oblong) is duplicated in tandem without any editing site in the first copy. The distant element is followed by 20 native 3′ nucleotides, which allow editing also at editing site atp4–251 (also shown as circled C). Thin lines show mitochondrial sequences, and bold bars represent bacterial sequences. B, comparison of in vitro RNA editing in the three template RNAs. The left panel shows the location of the RT-PCR primers used for cDNA amplification after in vitro incubation relative to the editing sites. The upstream site is monitored (circled). The right panel shows the sequence chromatograms of the total cDNA populations obtained from the in vitro editing products of the respective templates. The percentages of edited products (T) are given underneath each panel. C, selective RT-PCR amplification from a downstream primer specific for RNA molecules edited at one or both of the two downstream sites. The left panel shows the location of the RT-PCR primers used for cDNA amplification after in vitro incubation relative to the editing sites. Primer design and PCR conditions were chosen to accommodate one mismatch, so that RNAs in which both or either of the two editing sites in the downstream repeat were edited could serve as templates. In the template with the 61 nucleotide distant elements ∼80% of these RNAs are also edited at the upstream editing site. Approximately 40% of the RNAs edited at one or both of the 105 nucleotides distant downstream sites were also edited in the upstream copy. In the template with the 200 nucleotides distant elements ∼30% of these RNAs are also edited at the upstream editing site. As control an unmodified sequence analysis of this region is shown (0% editing) where only the background trace of T is detectable. Sequencing was done from a more distant primer resulting in merged traces of dinucleotides.

This increase to 25% over the single copy template with an in vitro editing rate of 2–3% still represents a large influence of the 61 nucleotide distant upstream duplications. In the next RNA editing templates the distance between the repeats was increased to 105 and 200 nucleotides. With these template RNAs, the editing rates at the downstream sites are ∼10% at a distance of 105 nucleotides and ∼2–3% at the distance of 200 nucleotides as judged from the signal strengths of mismatch analyses performed in parallel (data not shown).

The editing rate at the upstream site located at the 3′ end of the tandem repeat reveals increasing inhibition of editing with increasing distance to the downstream editing site (Fig. 5B). Although this upstream site is preceded by the tandem duplication of the specificity element, which in other templates yields 40–50% editing (Figs. 1 and 5A), and still reaches 40% editing when the downstream element is 61 nucleotides apart, in vitro editing comes to only 25% when the downstream element is 105 nucleotides away and to only 10% at a distance of 200 nucleotides (Fig. 5B). These observations suggest that with increasing distance the cooperative effect of the downstream element decreases and that this element now competes for the trans-factors. This competition in cis may be analogous to (but more efficient than) the inhibition of RNA editing by competition in trans (10, 12).

Because the level of in vitro editing in the template where the two elements are spaced 200 nucleotides apart does not allow any conclusion about an enhancing influence over this distance, editing at these sites was analyzed for some potential connection over this distance.

Connection between Editing Events Is Distance-dependent—To determine whether the editing events in the distant repeats are correlated in the RNA molecules, RT-PCR was initiated from a downstream primer that was designed to bind only to RNA templates edited at one or both of the editing sites atp4–248 and atp4–251 in the downstream element (Fig. 5C). In these cDNA molecules from RNAs with 61 nucleotide distant elements, the editing site of the upstream element is identified as ∼80% T (Fig. 5C).

Analogous investigations of the correlation between the two editing sites in the 105 and 200 nucleotides distant repeated elements (Fig. 5C) in these molecules, which are edited at one or both of the downstream sites, revealed ∼40 and ∼30%, respectively, to be also edited at the upstream element. These increases from the general editing rates at these sites (Fig. 5B) from ∼25 to 40% for the 105 and from the 10 to 30% for the 200 nucleotides distances suggest that even at these distances there is some cooperative influence between editing recognition site sequences.

DISCUSSION

The surprising observation of a manifold amplification of the in vitro RNA editing activity by cis-duplications of the specificity regions in RNA template molecules reported here allows several conclusions about the RNA editing process in plant mitochondria (20).

The RNA Editing Complex Is Guided in cis on the Template RNA—The in vitro RNA editing assays with template RNAs in which the specificity regions for editing sites are duplicated show that the editing activity can be attracted to the RNA molecule by cognate-binding motifs. Once binding to such a sequence has occurred in the RNA, the probability of finding another nearby editing recognition sequence is greatly increased. This enhancement is observed for homologous sequences, whereas heterologous sites have no such effect on the finding of and binding to another site in the RNA. The influence of neighboring editing sites with different recognition regions has been tested in vitro in the atp9 mRNA (11). With such a template, rather an inverse effect is observed; the presence of both these sites in a template RNA yields only low level editing, and elimination of one site increases editing at the remaining site.

The positive effect of duplicated identical editing target motifs is most impressive in the tandem duplication and in the four times tandem repeat of the atp4 specificity element. This cis-enhancement of the editing reaction suggests that either the editing complex searches along the RNA or that a cooperative cis-effect between the duplicated elements promotes functional and effective assembly of the RNA editing complex on the RNA molecule.

The RNA Editing Complex Is Influenced for up to 200 Nucleotides on the Template RNA—The lateral enhancement of RNA editing between amplified cognate sequence motifs on the RNA template is most effective with the tandemly repeated motifs (i.e. 20 nucleotides between editing sites) and decreases with increasing distances between the specific recognition motifs, suggesting a declining slope of this influence between 20 and 200 nucleotides.

The decreasing enhancement of editing seen over the distances of 20, 61, 105, and 200 nucleotides between the two homologous elements suggests that there is no clear yes-or-no border of the effective range of cooperation but rather a slowly declining effect over the increasing distance. Other editing site sequences with their individually different specificity factors may show different ranges of the cooperative process observed here.

Distant Duplicated Attachment Sites Act as cis-Competitors—Analysis of in vitro editing at an upstream editing site enhanced by a tandem duplication of the specificity elements in the RNA templates tested with another downstream element at various distances (Fig. 5B) detects an overlaying effect of inhibition by the presence of this downstream element. At shorter distances the enhancing effect of the cooperation between duplicated elements is stronger than the competing effect and increases editing (Fig. 1).

Possible in Vivo Significance of the Enhancement of RNA Editing by Similar Sequences—In plant mitochondria, the recognition sequences of most editing sites are very different, and a global lateral enhancing effect between neighboring sites as observed here in vitro appears to be unlikely in vivo. However, whereas duplicated “real” editing sites with their cognate recognition elements are not found in vivo and thus do not use this effect, sequence similarities to genuine editing sites might be sufficient to evoke this enhancement. Low sequence similarities have been identified between two different editing sites in plastids to be apparently sufficient to guide specific binding by the same editing recognition factor (21, 22).

In mitochondria with their much higher number of editing sites, such similar specificity elements may occasionally coincide for nearby sites. An example is the editing site at nucleotide 89 in the atp4 mRNA (atp4–89), which is located 157 nucleotides upstream of the cluster of editing sites tested here at atp4–248 and atp4–251. Between editing site atp4–89 and the first site atp4–248, 12 of the 20 respectively preceding nucleotides are identical and could very well act cooperatively. Indeed, placing the 20 upstream nucleotides of the site atp4–89 in a template RNA in tandem upstream of the specificity element of site atp4–249 enhances in vitro RNA editing at this latter site ∼10-fold (data not shown).

In addition, the enhanced guiding of the RNA editing complex from one specific recognition region to another reported here will make in vivo editing of this complex RNA population more efficient wherever additional similar yet specific RNA sequence recognition motifs are present. These will of course not be the duplicated editing sites tested here in vitro but may be scattered sequence similarities in the vicinity of bona fide editing sites. Once the precise nucleotide requirements for specific recognition and binding of the trans-factors are resolved at a number of individual editing sites, such elements that guide and enhance RNA editing in vivo can be searched for in silico. In vitro such motifs may be detectable as enhancing sequences. These may be similar to the element previously identified to enhance editing at two atp9 sites at a distance of ∼70 nucleotides (11).

The suggestion that sequence similarities in the vicinities of editing sites may guide and enhance editing at bona fide sites requires that the specificity sequence motif is sufficient as such even in the absence of an actual editing site. The assays reported here of templates with and without editing sites that are preedited or editable show that the enhancement by multiple specificity motifs is indeed effective in the absence of editable sites and may in fact be even more efficient than a duplicated element with an attached editing site.

These considerations suggest that the in vitro effects observed here may have a significant influence in vivo to boost the editing efficiency by promoting finding and binding of the cognate editing sites by the RNA editing specificity factors and the active complex.

PPR Proteins as Potential Factors in RNA Editing in Plant Plastids and Mitochondria—In plastid C to U editing, two PPR proteins have been identified to be required for RNA editing at one specific site each (23, 24). Although in plant mitochondria no such trans-factor has yet been characterized, by extrapolation some of the ∼400–450 members comprising family of PPR proteins in flowering plants (25) may also be involved in the recognition of specific editing sites. The PPR proteins have been shown to bind RNA (25), the plastid CCR4 protein showing high affinity to its cognate editing site (26). Binding of the protein to the RNA specifically involves the –20 to –1 region in the mRNA, just upstream of the editing site (26). This region has also been identified by in vitro analyses in plastids (1, 3–5, 8) as well as by in organello and in vitro studies in plant mitochondria as an essential cis-element for various editing sites (2, 9–12, 27, 28). The biochemical properties, the predicted structures of the PPR proteins, and their binding to specific cis-RNA regions fit very well with the observations made here of enhanced in vitro RNA editing by amplification of such cis-recognition sequences.

Duplicated Specificity Regions Enhance Recognition of an Editing Site: Substrates for Affinity Purification of the Specificity Factors—The observation and reasoning that access to the RNA template can be the limiting factor in vitro rather than the amount of trans-factor(s) available in the lysate from plant mitochondria increases the chances to identify these trans-factors by biochemical approaches. Because the supply of trans-factors in the in vitro employed mitochondrial lysate is not exhausted by template RNAs with multiple binding sites, there may be sufficient amounts of these trans-factors present in such mitochondrial extracts to allow their enrichment and subsequent identification by RNA affinity purification steps. Because the attraction and binding of these trans-factors can now be considerably enhanced by amplified cognate recognition sequences, such RNAs may be useful as bait to purify and identify these trans-factors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dagmar Pruchner for excellent experimental assistance.

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: RT, reverse transcription; TDG, thymine DNA glycosylase; PPR, pentatricopeptide repeat.

References

- 1.Shikanai, T. (2006) Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 63 689–708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takenaka, M., Verbitskiy, D., van der Merwe, J. A., Zehrmann, A., and Brennicke, A. (2008) Mitochondrion 8 35–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirose, T., and Sugiura, M. (2001) EMBO J. 20 1144–1152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miyamoto, T., Obokata, J., and Sugiura, M. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22 6726–6734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hegeman, C. E., Hayes, M. L., and Hanson, M. R. (2005) Plant J. 42 124–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakajima, Y., and Mulligan, M. (2006) J. Plant Physiol. 162 1347–1354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takenaka, M., Verbitskiy, D., van der Merwe, J. A., Zehrmann, A., Plessmann, U., Urlaub, H., and Brennicke, A. (2007) FEBS Lett. 581 2743–2747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sasaki, T., Yukawa, Y., Wakasugi, T., Yamada, K., and Sugiura, M. (2006) Plant J. 47 802–810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neuwirt, J., Takenaka, M., van der Merwe, J. A., and Brennicke, A. (2005) RNA 11 1563–1570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takenaka, M., Neuwirt, J., and Brennicke, A. (2004) Nucleic Acids Res. 32 4137–4144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Merwe, J. A., Takenaka, M., Neuwirt, J., Verbitskiy, D., and Brennicke, A. (2006) FEBS Lett. 580 268–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verbitskiy, D., Takenaka, M., Neuwirt, J., van der Merwe, J. A., and Brennicke, A. (2006) Plant J. 47 408–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giegé, P., and Brennicke, A. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96 15324–15329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wissinger, B., Brennicke, A., and Schuster, W. (1992) Trends Genet. 8 322–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Handa, H. (2003) Nucleic Acids Res. 31 5907–5916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bolle, N., and Kempken, F. (2006) FEBS Lett. 580 443–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choury, D., and Araya, A. (2006) Curr. Genet. 50 405–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takenaka, M., and Brennicke, A. (2007) Methods Enzymol. 424 439–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takenaka, M., and Brennicke, A. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 47526–47533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gagliardi, D., and Binder, S. (2007) in Plant Mitochondria (Logan, D., ed) pp. 50–96, Blackwell Publishing, Oxford

- 21.Kobayashi, Y., Matsuo, M., Sakamoto, K., Wakasugi, T., Yamada, K., and Obokata, J. (2007) Nucleic Acids Res. 36 311–318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heller, W. P., Hayes, M. L., and Hanson, M. R. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283 7314–7319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kotera, E., Tasaka, M., and Shikanai, T. (2005) Nature 433 326–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okuda, K., Myouga, R., Motohashi, K., Shinozaki, K., and Shikanai, T. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104 8178–8183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lurin, C., Andrés, C., Aubourg, S., Bellaoui, M., Bitton, F., Bruyère, C., Caboche, M., Debast, C., Gualberto, J. M., Hoffmann, B., Lecharny, A., Le Ret, M., Martin-Magniette, M.-L., Mireau, H., Peeters, N., Renou, J.-P., Szurek, B., Taconnat, L., and Small, I. (2004) Plant Cell 16 2089–2103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okuda, K., Nakamura, T., Sugita, M., Shimizu, T., and Shikanai, T. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 37661–37667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choury, D., Farré, J.-C., Jordana, X., and Araya, A. (2004) Nucleic Acids Res. 32 6397–6406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farré, J.-C., Leon, G., Jordana, X., and Araya, A. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biol. 21 6731–6737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]