Abstract

The architecture of the entire photosynthetic membrane network determines, at the supramolecular level, the physiological roles of the photosynthetic protein complexes involved. So far, a precise picture of the native configuration of red algal thylakoids is still lacking. In this work, we investigated the supramolecular architectures of phycobilisomes (PBsomes) and native thylakoid membranes from the unicellular red alga Porphyridium cruentum using atomic force microscopy (AFM) and transmission electron microscopy. The topography of single PBsomes was characterized by AFM imaging on both isolated and membrane-combined PBsomes complexes. The native organization of thylakoid membranes presented variable arrangements of PBsomes on the membrane surface. It indicates that different light illuminations during growth allow diverse distribution of PBsomes upon the isolated photosynthetic membranes from P. cruentum, random arrangement or rather ordered arrays, to be observed. Furthermore, the distributions of PBsomes on the membrane surfaces are mostly crowded. This is the first investigation using AFM to visualize the native architecture of PBsomes and their crowding distribution on the thylakoid membrane from P. cruentum. Various distribution patterns of PBsomes under different light conditions indicate the photoadaptation of thylakoid membranes, probably promoting the energy-harvesting efficiency. These results provide important clues on the supramolecular architecture of red algal PBsomes and the diverse organizations of thylakoid membranes in vivo.

Photosynthesis is an important biological process performed by a series of pigment-protein complexes in photosynthetic membranes with strong cooperativity. In prokaryotic cyanobacteria and eukaryotic red algae, the photosynthetic membrane network can be divided into two distinct functional platforms: the thylakoid membrane itself, which contains a set of intrinsic photosynthetic protein complexes such as photosystem I (PSI),2 photosystem II (PSII), ATP synthase, and cytochrome b6/f (1, 2), and the thylakoid (stromal) surface, which is covered by one layer of phycobilisomes (PBsomes), the extrinsic photosynthetic antenna complexes (3–8). Solar energy is captured by the PBsome complexes and transferred efficiently to the chlorophyll pigments in the photosynthetic reaction centers, and subsequent energy transformation is carried out by the photosynthetic machinery embedded within the membrane. For maintaining the high efficiency of energy migration, the close coupling between the topographs of both photosynthetic platforms is required, and of interest.

The application of electron microscopic techniques at the cellular and subcellular levels has been key to the discovery and extensive studies of the PBsome complexes (9–12). The arrangement of PBsomes on the membrane surface and that of photosystems within the membrane were observed in the unicellular red alga Porphyridium cruentum by Gantt and coworkers (13, 14). Based on electron microscopic data, a hemiellipsoidal structural model of PBsomes from P. cruentum was proposed (15). Recently, we further analyzed the morphology of hemiellipsoidal PBsomes by single particle transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (16). In addition, utilizing biochemical and molecular biological techniques, a large amount of valuable information about, for instance the DNA and protein sequences of phycobiliproteins (PBPs) and linker polypeptides, as well as their refined crystal structures, has been obtained (for reviews, see Refs. 3, 7, 17, 18). Structural data are also available now for a variety of photosynthetic complexes from x-ray crystallography and electron microscopy (19–25).

Increasing interest has recently been focused on the supramolecular architecture of native photosynthetic membranes and the dynamic arrangements of photosynthetic proteins with the aim of surveying the functional coordination and physiological regulation among those photosynthetic complexes. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) has been demonstrated to be a powerful tool to directly acquire the morphology of supramolecular assemblies in native membranes under near-physiological conditions (26). Recently, it has fostered the exploration of photosynthetic membranes of purple bacteria (27–32) and higher plant (33–35). Investigation using AFM to visualize the native three-dimensional structure of PBsomes and the supramolecular architecture of thylakoid membrane is unique and interesting (36–38).

In this work, we applied AFM for the first time to investigate the native configuration and architecture of PBsome-combining thylakoid membranes from red alga P. cruentum, as well as the diverse organizations of thylakoid membranes with respect to various light illuminations using AFM and TEM. The results provide important clues as to the photosynthetic function of red algal PBsomes in vivo in relation to their supramolecular architecture.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Growth of Cells—P. cruentum were grown in an artificial sea-water medium (39). Flasks were supplied with 3% CO2 in air at 18 °C. Cultures were illuminated continuously with light provided by daylight fluorescent lamps at different light intensities, 6 watts·m-2 (low light, LL) and 15 watts·m-2 (medium light, ML).

Separation of Intact PBsomes and PBsome-thylakoid Membrane—Intact PBsomes were separated following the previous protocol (16). The preparation of PBsome-membrane vesicles followed the earlier procedure (13) with slight modifications. Cells were harvested (5000 × g, 10 min), rinsed, and then suspended in SPC medium (0.5 m sucrose, 0.5 m potassium phosphate, 0.3 m sodium citrate). After homogenization cells was broken in French pressure cell with relative low pressure (4000 p.s.i.) for achieving large membrane sheets with ideally less disturbance. The broken cell mixture was layered on a two-step gradient of sucrose (1.0 and 1.3 m) in 0.5 m phosphate/0.3 m citrate, pH 7.0. After centrifugation for 30 min, the PBsome-containing thylakoids were collected from the 1.0–1.3 m sucrose interface.

Spectral Analysis—Absorbance spectra and their second derivatives were recorded with UV-160A spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Japan). Room-temperature fluorescence spectra were obtained with LS 55 Luminescence spectrometer (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) at the excitation wavelength of 545 nm.

SDS-PAGE—Intact PBsomes were suspended in 20 mm K-buffer (pH 6.8) before loading. The protein composition was determined by SDS-PAGE using a 12.5% polyacrylamide gel and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250. Molecular mass was estimated using a molecular size marker set (PageRuler™ Unstained Protein Ladder SM0661, Fermentas).

AFM—5 μl of isolated PBsomes or PBsome-containing membranes fixed with 1% glutaraldehyde was spread on freshly cleaved mica for 30–60 min. Afterward the sample was rinsed with dialysis water to remove salt and membranes that were not firmly adsorbed to the substrate. The samples were measured in AFM with tapping mode in ambient condition at room temperature. AFM cantilevers with a length of 240 μm, spring constant 2.0 newtons/m, and operating frequencies of 65–80 kHz (Olympus Micro cantilever tip, Japan) were used.

TEM—According to our reported procedure (16), samples were fixed with 2% glutaraldehyde on carbon-coated copper grids before washing with distilled water, and then negatively stained with 2% uranyl acetate. Electron microscopy was performed on a JEOL JEM-1010 transmission electron microscope operated at an accelerating voltage of 80 kV.

RESULTS

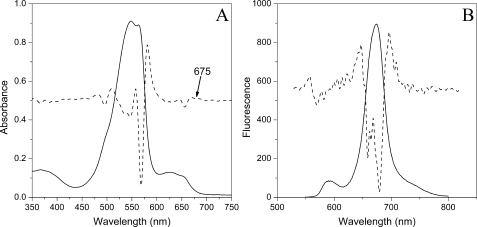

Spectral Properties of Isolated PBsomes—Isolated PBsomes shows an absorbance maximum at 549 nm with additional absorbance at 564 nm due to the presence of phycoerythrin (PE) molecules (Fig. 1A). The shoulder at 500 nm is attributed to phycourobilins of PEs. Other pronounced shoulders at 624 nm and 650 nm are attributed to R-phycocyanins and allophycocyanins, respectively. The second derivative of this spectrum clearly reveals a slight shoulder at 675 nm, which will be characterized as the absorbance of allophycocyanin B, consistent with previous results (11, 40).

FIGURE 1.

Absorbance (A) and fluorescence (B) properties of PBsomes from P. cruentum in 0.75 m potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0. Excitation was at 545 nm. The second derivative analysis is represented by dashed lines.

Fluorescence emission spectrum (Fig. 1B) with excitation at 545 nm exhibits four distinct spectroscopic components at 580 nm (PE), 663 nm (allophycocyanin), 671 nm (LCM), and 681 nm (allophycocyanin B) (41–43). Such a fluorescence behavior could verify the structural and functional integrity of the isolated PBsomes (40, 44).

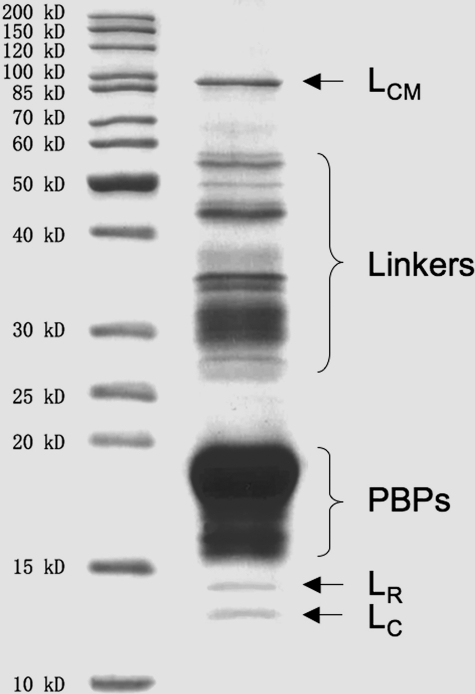

SDS-PAGE Analysis—The major components of PBsomes are PBPs, which are mainly composed of α and β subunits with molecular masses of 15–20 kDa (Fig. 2). Other proteins include LCM with 90 kDa, linker polypeptides of 28–36 kDa, and smaller linkers (LR, LC) of 12–15 kDa. It further demonstrates the integrity of isolated PBsome complexes (40, 45).

FIGURE 2.

Coomassie staining of polypeptide components of isolated PBsomes from P. cruentum identified by SDS-PAGE (12.5%). Left panel, standard protein marker (Fermentas); right panel, isolated PBsomes.

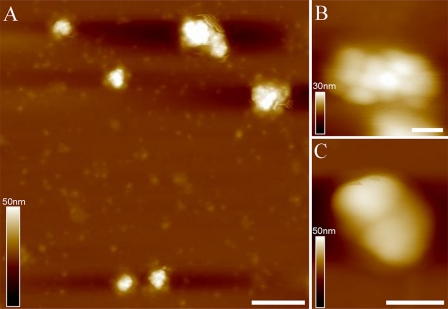

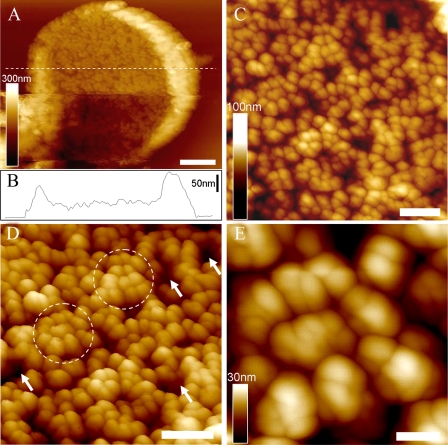

AFM Topography of Isolated PBsomes—To retain the conformational integrity, the PBPs in the PBsome structures were chemically cross-linked with glutaraldehyde. Fig. 3A shows the AFM micrographs of isolated PBsome complexes absorbed on the mica surface. Single PBsomes imaged with AFM have average dimensions of 64 × 42 × 28 nm (length × width × height) (Table 1), and are slightly elongated in one direction. This is in reasonable agreement with the TEM result of 60 × 41 × 34 nm (16), if one takes into account some uncertainty in setting the boundaries of the complex, arising, for example, from tip convolution and compression effects in the case of AFM. Also, sample conditions are somewhat different in both experiments. Fig. 3B presents a top view of a single PBsome. The structure of a single PBsome complex exhibits a higher central part and lower peripheral sides, in close agreement with the early description of ellipsoidal conformation (15). The peripheral PBP units are observed as protrusions with the size of ∼13 nm, consistent with previous data (12, 46). Each may represent one individual PBsome rod. More interestingly, PBsome aggregates are also visible as larger particles, e.g. Fig. 3C shows a dimeric structure. Similar with previous TEM images (47, 48), the two PBsomes in such a dimer are coupled bottom-to-bottom with one another. This dimeric configuration may be caused by the hydrophobic property of linker polypeptides in PBsome core complexes, LCM, which is involved in the anchoring of the PBsome complexes to photosynthetic reaction centers (49).

FIGURE 3.

AFM micrographs of isolated PBsome complexes absorbed on the mica surface. A, the distribution of individual PBsomes on the substrate; B, raw AFM image of single PBsome complex; C, raw AFM image of PBsome-dimer configuration. Lateral dimension of PBsome particle is characterized in detail in Table 1. Scale bar: A, 100 nm; B, 20 nm; C, 50 nm.

TABLE 1.

Measurements of PBsome dimensions

| Measurement | Length | Width | Height |

|---|---|---|---|

| nm | |||

| TEM singlea | 60 | 41 | 34 |

| AFM single | 64 ± 4 | 42 ± 3 | 28 ± 3 |

| TEM MLa | 60 | 41 | 34 |

| TEM LLa | 60 | 41 | 34 |

| AFM ML | 60 ± 4 | 39 ± 3 | 30 ± 3 |

| AFM LL | 57 ± 3 | 32 ± 2 | 32 ± 2 |

Data from our previous work (16)

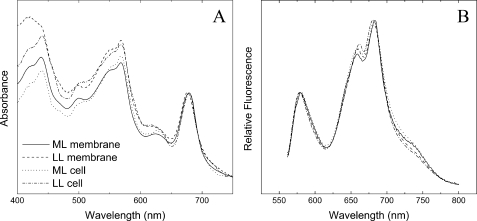

Medium-light Acclimation of PBsome-thylakoid Membrane—Fig. 4 shows the room temperature absorption and fluorescence spectra of whole cells and PBsome-thylakoid membranes grown under ML and LL. The optical properties of the separated samples are consistent with those reported in the previous literature (13), confirming the physiological attachment of PBsomes to the thylakoid membranes. In both illumination conditions, moreover, the spectral features of PBsome-thylakoid membranes are comparable to those of whole cells, indicating that the gentle isolation procedure did not cause remarkable perturbation in the coupling of PBsomes to the photosystems. TEM has been applied to study the isolated thylakoid membranes densely covered with PBsomes (16).

FIGURE 4.

Spectral properties of whole cells and isolated PBsome-thylakoid membranes from P. cruentum grown under LL (6 watts·m-2) and ML (15 watts·m-2). A, absorption spectra. Spectra were normalized to the chlorophyll absorption band at 682 nm. It shows several partially resolved peaks, which are assigned to chlorophyll a (439 nm and 678 nm), carotenoids (490 nm), and PBsomes (500–650 nm); B, room temperature fluorescence spectrum. Excitation was at 545 nm. It shows three distinguishable fluorescence bands at 580, 660, and 680 nm. The 580 nm peak corresponds to the PE fraction of PBsomes. The 660 nm fluorescence emission components may come from the intact PBsomes. The fluorescence emission at 680 nm is attributed to mostly PSII and a small shoulder at 730 nm is from PSI, because PSI fluorescence emission is generally low at room temperature.

The first AFM topograph of the three-dimensional organization of native PBsome-thylakoid membranes is shown in Fig. 5. After adsorption on freshly cleaved mica, the thylakoid membranes were mostly found to expose the stromal surface to the probe side, and the membrane-combined PBsome complexes can be used as topographic features that can be readily identified (Fig. 5A). The lipid layer was recognized as the dark regions in between the PBsomes (Fig. 3D, arrows). The thylakoid fragments have diameters as large as 2.5–3.0 μm. Fig. 5B presents the height profile of one patch of thylakoid membrane fragment. It clearly characterizes three different plateaus representing the mica surface, the single PBsome membrane (a mean height of 48 nm), and folding membrane edges (average height of 90 nm on the left and 130 nm on the right), respectively. The membrane surface is covered with more or less randomly distributed PBsome complexes (Fig. 5C). The size of single PBsomes is recorded with the length of 60 ± 4 nm, the width of 39 ± 3 nm, and the height of 30 ± 3 nm (n = 30) (see Table 1), comparable with that of isolated PBsomes as shown in Fig. 5B. Moreover, it appears, by closer inspection of the AFM topography, that some PBsomes have a tendency to form clustered domains (Fig. 5D, circles). The clustering arrangement of PBsomes might enable light-harvesting complexes to form physiological units to promote energy trapping. Furthermore, individual PBsome complexes and their subcomponents were visualized in AFM topography with a slight heterogeneity with regard to lateral dimension and height (Fig. 5E). Actually, the AFM analyses of ML-adapted thylakoid membranes did not resolve very detailed substructure of individual PBsomes, probably due to the flexible dimension and soft configuration of PBsome supramolecular complexes.

FIGURE 5.

AFM micrographs of PBsome-attached membrane from P. cruentum grown in ML. A, two-dimensional AFM images of PBsome-attached membrane fragment; B, height profile of PBsome-attached membrane in panel A; C, enlarged AFM image from panel A showing random PBsome arrangement; D, enhanced three-dimensional AFM images of PBsome distribution on the photosynthetic membrane surface. PBsome clusters are shown as circles, and PBsome-free membrane regions are represented by arrows; E, enlarged view high resolution AFM images of the PBsome-clustering domain. Individual PBsomes and the substructures can be visualized. Scale bar: A, 500 nm; C and D, 200 nm; E, 50 nm.

Low-light Acclimation of PBsome-thylakoid Membrane—The thylakoid membranes from P. cruentum grown under LL (6 watts·m-2) were also analyzed. Normalized fluorescence emission spectra of the LL-adapted membranes present a somewhat similar profile compared with that of ML-grown membranes, suggesting no significant functional changes in the light-harvesting capacity of both samples. Absorption spectroscopy allows the comparative analysis of pigment compositions of thylakoid membranes with respect to light variation (Fig. 4). In view of the invariable size of PBsomes (16, 50), the increase of PE/chlorophyll ratio in the absorbance of LL-adapted membranes might indicate an inclined PBsome density per thylakoid area, to meet a higher demand for light-harvesting capacity. This was further demonstrated by the increased density of PBsomes (560 ± 40 PBsomes/μm2) on LL-adapted membranes (16).

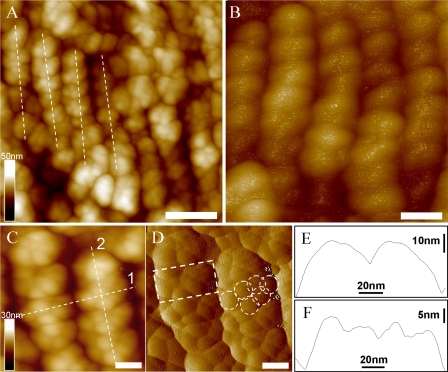

The native two-dimensional-crystalline motif of PBsomes on the isolated thylakoid membranes was observed in AFM images (Fig. 6). On the large fragment, PBsomes were observed to arrange in parallel rows (Fig. 6A, lines), although some random PBsome domains were still visible. Close inspection of the thylakoid organization showed that PBsomes within the regular rows along the short axis of PBsomes are closely packed side-to-side, the distance between adjacent parallel rows being very short (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, we found that the substructure of individual PBsomes, presumably individual rods, can be visualized by applying gentle force in this case, as shown in Fig. 6 (C and D). Each PBsome rod was characterized by a diameter of 13 nm. In the higher central part of the PBsome, there are two rods vertically protruding with respect to the membrane surface, and several neighboring rods seem to intersect with each other to form a condensed configuration. The profound complexity of the architecture of the hemiellipsoidal PBsome is incompatible with a structure consisting of two closely packed hemidiscoidal PBsomes as suggested before (40); in that case the rods would be located in the same plane vertical to the core cylinders. This conclusion is consistent with our single-particle analysis of TEM data (16). In Fig. 6 (E and F), the spacing between rows of PBsomes was measured to be 56 ± 4 nm along the long axis and 35 ± 2 nm on the short axis (n = 20), corresponding to the spacing of PSII rows as reported before (51, 52). The PBsome dimension was obtained by the height measurement relative to the membrane surface: the length of 57 ± 3 nm, the width of 32 ± 2 nm, and the height of 32 ± 2 nm (n = 30) (Table 1). The somewhat reduced lateral dimension that we observe is probably due to the crowding of PBsomes. The packing effects may also hamper the precise height recording of PBsomes, because the membrane surface under the PBsome layer is hard to observe in the images. Yet, the AFM topographs still provide new insights into the spatial rendering of PBsomes, and the observed parallel arrangement of PBsomes strongly supports the hypothetical model of the thylakoid membrane in PBsome-containing species (48, 53–55).

FIGURE 6.

AFM micrographs of PBsome-attached membrane from P. cruentum grown in LL. A, raw two-dimensional AFM images of PBsome-attached membrane. Crystal line arrays of PBsome are presented with dotted lines; B, enhanced three-dimensional AFM topograph of parallel rows of PBsomes on the membrane; C, height-mode high resolution AFM image of PBsome arrangement; D, amplitude-mode high resolution AFM image of PBsome arrangement. Substructures of individual PBsome complexes (square) are discerned, and PBsome rods in each macromolecular complex are shown as circles; E and F, height profiles of PBsome configurations on the thylakoid membrane along lines 1 and 2 in panel C, respectively. Scale bar: A, 100 nm; B, 50 nm; C and D, 25 nm.

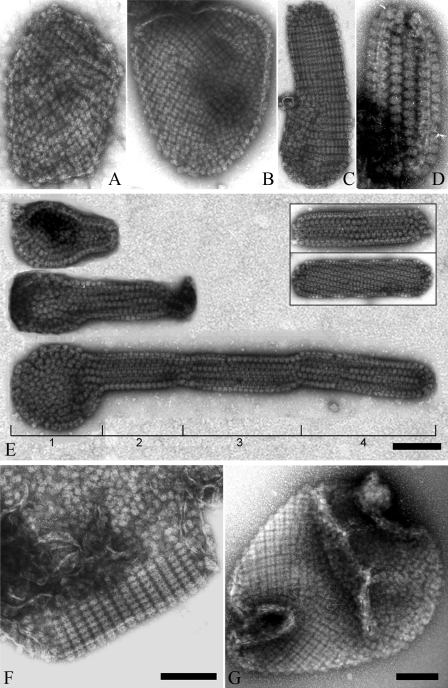

Diverse Distribution Pattern of PBsomes on Thylakoid Membrane by TEM—Despite the results presented above, further structural investigation of thylakoid morphology by means of TEM showed various patterns of PBsome arrangements, for instance random distribution, crystalline arrays, and even mixed arrangements (Fig. 7). Although large membrane patches were frequently monitored with gentle preparation, tubular-shape fragments appear occasionally. It was seen that most of the tubular fragments are densely covered with well crystallized PBsomes, and along the tubular direction PBsomes have a preference to form either straight or helical packing, probably due to large dimension of extrinsic PBsomes and high PBsome-to-lipid ratio. Except the artificial disturbance and auto-crystallization during sample treatments, they were presumed to exist in vivo as the internal linkages between different layers of the photosynthetic membranes (56, 57). Distinct lengths of tubular fragments might also indicate the development of the photosynthetic membranes. It is worthy to note that parallel arrangement of PBsomes is actually the most common, but not the sole pattern existing in vivo at low irradiance, because disordered PBsome-thylakoid sheets, and even the mixture of both ordered and disorder arrangements were occasionally visible (Fig. 7, F and G).

FIGURE 7.

Diverse morphological patterns of PBsomes-thylakoid membranes. A and B, flat patches; C and D, tubular shapes and vesicle topography. Interestingly, besides individual tubular fragments (E, inset), a successive process of thylakoid growth is observable. A small fragment protrudes from a base patch, which is generally bound by less organized PBsomes (E, part 1), and then develop to tubular membrane fragments with variable lengths and copies (E, parts 2–4). In addition, ordered and disorder arrangements can occasionally be imaged on the same membrane patch (F and G).

DISCUSSION

Lateral mobility of PBsomes in vivo has been proposed in cyanobacteria (58–61). There is evidence that concentrated buffers, such as the SPC medium used in this work (see “Experimental Procedures”), have the effect of artificially stabilizing the interaction of PBsomes and photosynthetic reaction centers (37, 61), so that PBsomes could be immobilized upon thylakoid membrane surface and imaged by AFM.

The primary structure of PBsomes from the unicellular red alga P. cruentum has been proposed on the basis of TEM images (15). Here, our AFM topographs present the native hemi-spherical configurations of isolated PBsomes and membrane-combined PBsomes at three-dimensional level, although high resolution is difficult to achieve. This is probably due to the conformational flexibility and height properties of PBsomes. Nevertheless, AFM topography was demonstrated to be able to depict the physiological architecture of PBsomes and their organization upon the native thylakoid membrane.

P. cruentum exhibits the simplest organization of eukaryotic chloroplasts, with unstacked and mostly parallel thylakoid membranes. In addition to the native three-dimensional configurations of single PBsomes, we investigated for the first time the three-dimensional supramolecular organization of native PBsome-combining thylakoid membrane by means of AFM. The most striking feature of the native thylakoids is the various types of PBsome arrangements observed. In one pattern, PBsome complexes were arranged randomly, similar to previous TEM results (13, 14). Moreover, PBsomes in this pattern had a tendency to form locally clustered motifs that are expected to improve the light-harvesting capacity.

When grown under LL conditions, PBsomes are organized into rather parallel rows on the isolated thylakoid membranes of P. cruentum. Despite the close packing of PBsomes located on opposite thylakoid layers in vivo (13), such an effect of confinement may also arise from interactions within the lateral dense monolayer of PBsome complexes. Furthermore, the ordered arrays of PBsomes present an inclined density of PBsomes on the thylakoid surface, which was corroborated with the absorption spectra (Fig. 4A). This apparently implies that light intensity is an essential factor in determining the PBsome densities as well as the lateral arrangements of PBsomes on the thylakoid membrane. We conclude that the variation of PBsome arrangement and density upon the chloroplasts is probably a physiological strategy to adapt to light irradiance, with the aim to modulate the capacity of energy utilization of photosynthetic complexes. Such a photoadaptation bears resemblance to the findings obtained from photosynthetic bacteria, which have demonstrated the significance of high and low light conditions (chromatic adaptation) for determining the organization of light-harvesting complexes in the photosynthetic membranes of purple bacteria (28, 30).

Our data, moreover, clearly showed the fact that PBsomes are densely packed on the membrane surface. Such a dense packing of photosynthetic proteins may provide a greater concentration of chromophores and electron transport complexes in a limited membrane area, allowing a higher rate of photosynthetic activity; and enhance the efficiency of light-harvesting by promoting the interaction of light-harvesting antennae with reaction centers (36).

In cyanobacteria and red algae, the photosynthetic membrane network can be differentiated into two structural and functional entities: the thylakoid membrane containing the primary photosynthetic apparatus, and the PBsome pool closely coupled to the thylakoid membrane. Energy transfer between these two entities is mediated by the spatial organizations and interactions of photosynthetic pigment proteins. Two possible arrangements of PSII and PSI core complexes in the thylakoid membrane of cyanobacteria have been proposed (62). One assumes that PSII dimers arrange in rows, whereas PSI trimers are randomly distributed between the PSII rows. The other presents PSII dimers and PSI trimers as randomly dispersed in the thylakoid membrane. In our case, that of red algae, both random and ordered arrangements of PBsomes are found, indicating a variable distribution of photosystems in the thylakoid membrane. More specifically, the presence of parallel rows of PBsomes may also hint the specific combination of PBsomes with PSII.

Alternatively, it is worthy to note that the PSI shoulder at ∼740 nm is relatively higher in both cells and membranes from ML growth conditions, as shown in the fluorescence spectra (Fig. 4B). This preference of energy transfer from PBsomes to PSI reaction centers may indicate a potential interaction between PBsomes and PSI, inducing more randomized distribution of PBsomes in ML-adapted cells.

We have also investigated the morphology of PBsome-thylakoid membranes from P. cruentum during state transition,3 by adjusting red and green light as reported before (63). The variety of PBsome arrangement that we observed might be expected to occur in the energy redistribution process (13, 63–65). However, no significant structural changes were monitored under red and green light at the same intensity level, suggesting on the other hand, the significance of light illumination in determined the arrangements of PBsomes.

Because PSI and PSII complexes are distributed throughout the thylakoid membrane (13) and the spacing between neighboring photosystems are imaged too small,3 the crowded coverage of PBsomes on the thylakoid surface indicates the possibility that both PSII and PSI coexist closely underneath one hemiellipsoidal PBsome complex. Such a specific organization could ensure excitation energy from PBsome complexes to be efficiently and dynamically redistributed to distinct relevant photosynthetic reaction centers (65). In state transition of red alga P. cruentum, it is possible that local conformational changes, for example nanoscale movement of PBsomes between adjacent PSII and PSI complexes, rather than long distance diffusion of PBsome complexes, can account for energy redistribution from PSII to PSI. More evidences are still needed to address the question.

The work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant 40676078), by the Hi-Tech Research and Development program of China (Grant 2008AA09Z404), and by the Key International S&T Cooperation Project of China (Grant 2008DFA30440). This project is part of the research programme “From Molecule to Cell” funded by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research and the Foundation for Earth and Life Sciences. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: PSI, photosystem I; PSII, photosystem II; AFM, atomic force microscopy; LL, low light; ML, medium light; PBsome, phycobilisome; PBP, phycobiliprotein; PE, phycoerythrin; TEM, transmission electron microscopy.

L.-N. Liu, T. J. Aartsma, J.-C. Thomas, G. E. M. Lamers, B.-C. Zhou, and Y.-Z. Zhang, unpublished data.

References

- 1.Bald, D., Kruip, J., and Rögner, M. (1996) Photosynth. Res. 49 103-118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gantt, E. (1994) in The Molecular Biology of Cyanobacteria (Bryant, D. A., ed) pp. 119-138, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht

- 3.Adir, N. (2005) Photosynth. Res. 85 15-32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gantt, E. (1986) in Photosynthesis III: Photosenthetic Membranes and Light Harvesting Systems (Staehelin, L. A., Anderson, J. M., and Arntzen, C. J., eds) pp. 260-268, Springer, Berlin

- 5.Glazer, A. N. (1985) Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biophys. Chem. 14 47-77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grossman, A. R., Schaefer, M. R., Chiang, G. G., and Collier, J. L. (1993) Microbiol. Rev. 57 725-749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacColl, R. (1998) J. Struct. Biol. 124 311-334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sidler, W. A. (1994) in The Molecular Biology of Cyanobacteria (Bryant, D. A., ed) pp. 139-216, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht

- 9.Gantt, E., and Conti, S. F. (1966) J. Cell Biol. 29 423-434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barber, J., Morris, E. P., and da Fonseca, P. C. (2003) Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2 536-541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ducret, A., Muller, S. A., Goldie, K. N., Hefti, A., Sidler, W. A., Zuber, H., and Engel, A. (1998) J. Mol. Biol. 278 369-388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yi, Z. W., Huang, H., Kuang, T. Y., and Sui, S. F. (2005) FEBS Lett. 579 3569-3573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mustardy, L., Cunningham, F. X., Jr., and Gantt, E. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89 10021-10025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dilworth, M. F., and Gantt, E. (1981) Plant Physiol. 67 608-612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gantt, E., Lipschultz, C. A., and Zilinskas, B. (1976) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 430 375-388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arteni, A. A., Liu, L. N., Aartsma, T. J., Zhang, Y. Z., Zhou, B. C., and Boekema, E. J. (2008) Photosynth. Res. 95 169-174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Betz, M. (1997) Biol. Chem. 378 167-176 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu, L. N., Chen, X. L., Zhang, Y. Z., and Zhou, B. C. (2005) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1708 133-142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bumba, L., Havelkova-Dousova, H., Husak, M., and Vacha, F. (2004) Eur. J. Biochem. 271 2967-2975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferreira, K. N., Iverson, T. M., Maghlaoui, K., Barber, J., and Iwata, S. (2004) Science 303 1831-1838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gardian, Z., Bumba, L., Schrofel, A., Herbstova, M., Nebesarova, J., and Vacha, F. (2007) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1767 725-731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jordan, P., Fromme, P., Witt, H. T., Klukas, O., Saenger, W., and Krauss, N. (2001) Nature 411 909-917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kamiya, N., and Shen, J. R. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100 98-103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nield, J., Kruse, O., Ruprecht, J., da, F. P., Buchel, C., and Barber, J. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 27940-27946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zouni, A., Witt, H. T., Kern, J., Fromme, P., Krauss, N., Saenger, W., and Orth, P. (2001) Nature 409 739-743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scheuring, S., Seguin, J., Marco, S., Lévy, D., Robert, B., and Rigaud, J.-L. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100 1690-1693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frese, R. N., Pamies, J. C., Olsen, J. D., Bahatyrova, S., van der Weij-De Wit, C. D., Aartsma, T. J., Otto, C., Hunter, C. N., Frenkel, D., and van Grondelle, R. (2008) Biophys. J. 94 640-647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scheuring, S., Gonçalves, R. P., Prima, V., and Sturgis, J. N. (2006) J. Mol. Biol. 358 83-96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gonçalves, R. P., Bernadac, A., Sturgis, J. N., and Scheuring, S. (2005) J. Struct. Biol. 152 221-228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scheuring, S., and Sturgis, J. N. (2005) Science 309 484-487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bahatyrova, S., Frese, R. N., Siebert, C. A., Olsen, J. D., van der Werf, K. O., van Grondelle, R., Niederman, R. A., Bullough, P. A., Otto, C., and Hunter, C. N. (2004) Nature 430 1058-1062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scheuring, S., Sturgis, J. N., Prima, V., Bernadac, A., Lévy, D., and Rigaud, J.-L. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101 11293-11297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gradinaru, C. C., Martinsson, P., Aartsma, T. J., and Schmidt, T. (2004) Ultramicroscopy 99 235-245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaftan, D., Brumfeld, V., Nevo, R., Scherz, A., and Reich, Z. (2002) EMBO J. 21 6146-6153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kirchhoff, H., Lenhert, S., Buchel, C., Chi, L., and Nield, J. (2008) Biochemistry 47 431-440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mullineaux, C. W. (2008) Photochem. Photobiol., in press [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Mullineaux, C. W. (2008) Photosynth. Res. 95 175-182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gantt, E., Grabowski, B., and Cunningham, F. X., Jr. (2003) in Light-Harvesting Antennas in Photosynthesis (Green, B. R., and Parson, W. W., eds) pp. 307-322, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht

- 39.Jones, R. F., Speer, H. L., and Kury, W. (1963) Physiol. Plant. 16 636-643 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Redecker, D., Wehrmeyer, W., and Reuter, W. (1993) Eur. J. Cell Biol. 62 442-450 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gindt, Y. M., Zhou, J., Bryant, D. A., and Sauer, K. (1994) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1186 153-162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Glazer, A. N., Chan, C., Williams, R. C., Yeh, S. W., and Clark, J. H. (1985) Science 230 1051-1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Houmard, J., Capuano, V., Colombano, M. V., Coursin, T., and Tandeau de Marsac, N. (1990) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 87 2152-2156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu, L. N., Elmark, A. T., Aartsma, T. J., Thomas, J. C., Lamers, G. E. B., Zhou, B. C., and Zhang, Y. Z. (2008) PLoS ONE 3 e3134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Redlinger, T., and Gantt, E. (1981) Plant Physiol. 68 1375-1379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ficner, R., and Huber, R. (1993) Eur. J. Biochem. 218 103-106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ritz, M., Lichtle, C., Spilar, A., Joder, A., Thomas, J. C., and Etienne, A. L. (1998) J. Phycol. 34 835-843 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wanner, G., and Köst, H. P. (1980) Protoplasma 102 97-109 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Redlinger, T., and Gantt, E. (1982) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 79 5542-5546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ohki, K., Gantt, E., Lipschultz, C. A., and Ernst, M. C. (1985) Plant Physiol. 79 943-948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Giddings, T. H., Wasmann, C., and Staehelin, L. A. (1983) Plant Physiol. 71 409-419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsekos, I., Reiss, H. D., Orfanidis, S., and Orologas, N. (1996) New Phytologist 133 543-551 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lefort-Tran, M., Cohen-Bazire, G., and Pouphile, M. (1973) J. Ultrastruct. Res. 44 199-209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gantt, E. (1980) Int. Rev. Cytol. 66 45-80 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tsekos, I., Reiss, H. D., and Delivopoulos, S. G. (2004) Phycologia 43 543-551 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nevo, R., Charuvi, D., Shimoni, E., Schwarz, R., Kaplan, A., Ohad, I., and Reich, Z. (2007) EMBO J. 26 1467-1473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shimoni, E., Rav-Hon, O., Ohad, I., Brumfeld, V., and Reich, Z. (2005) Plant Cell 17 2580-2586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sarcina, M., Tobin, M. J., and Mullineaux, C. W. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 46830-46834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mullineaux, C. W., Tobin, M. J., and Jones, G. R. (1997) Nature 390 421-424 [Google Scholar]

- 60.Joshua, S., Bailey, S., Mann, N. H., and Mullineaux, C. W. (2005) Plant Physiol. 138 1577-1585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Joshua, S., and Mullineaux, C. W. (2004) Plant Physiol. 135 2112-2119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mullineaux, C. W. (1999) Aust. J. Plant Physiol. 26 671-677 [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cunningham, F. X., Dennenberg, R. J., Jursinic, P. A., and Gantt, E. (1990) Plant Physiol. 93 888-895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brimble, S., and Bruce, D. (1989) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 973 315-323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McConnell, M. D., Koop, R., Vasil'ev, S., and Bruce, D. (2002) Plant Physiol. 130 1201-1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]