Abstract

Objective

The aim of this article is to illustrate the pectoralis minor muscle as a possible pain source in patients with anterior chest pain, especially those who are known to be beginner cross-country skiers.

Clinical Features

A 58-year-old man presented with anterior chest pain and normal cardiac examination findings. Upon history taking and physical examination, the chest pain was determined to be caused by active trigger points in the pectoralis minor muscle.

Intervention and Outcome

The patient was treated with Graston Technique and cross-country skiing technique advice. The subject's symptoms improved significantly after 2 treatments and completely resolved after 4 treatments.

Conclusion

This case demonstrates the importance of differential diagnosis and mechanism of injury in regard to chest pain and that chiropractic management can be successful when addressing patients with chest wall pain of musculoskeletal origin.

Key indexing terms: Pectoralis muscles, Biomechanics, Skiing, Chest pain

Introduction

Chest pain is common, representing the second most common complaint at North American emergency departments; and because of its potential fatality (ie myocardial infarct), overinvestigation occurs frequently and represents a significant expense to the health care system.1 Noncardiac chest pain refers to chest pain in the anterior chest wall that is not due to underlying heart pathology. It is important that noncardiac chest pain is diagnosed early to reassure patient concerns of potential ischemic myocardial infarction.2 These diagnoses may often include gastroesophageal dysfunction, psychiatric disorders, and musculoskeletal causes. Athletes competing in cross-country skiing often experience anterior chest wall pain of mechanical origin because of the repetitive motion of the upper extremities. Beginner cross-country skiers are particularly at risk for this condition as a result of recruitment of smaller muscle groups as opposed to larger muscle groups, particularly as they increase the intensity of their training. The somatic presentation of the pectoralis minor trigger point, as described by Simons et al,3 mimics cardiac angina and should be considered as a differential diagnosis for chest pain.

To date, there is a paucity of case reports describing pseudo–angina pectoralis caused by pectoralis minor trigger points.4,5 One recent report documents chest pain with subscapularis trigger points.6 This case report describes a 58-year-old man presenting with anterior chest wall pain with referral into the medial arm caused by a strain of pectoralis minor from cross-country skiing that was treated conservatively with Graston Technique, and discusses the importance of history taking and biomechanical understanding of cross-country skiing in the diagnosis of musculoskeletal causes of anterior chest pain.

Case report

A 58-year-old white man presented with anterior chest pain and normal cardiac investigation findings. Written informed consent for this case report to be published was obtained from the patient. The patient initially described his chief complaint as left-sided upper shoulder pain with radiation into the neck and down the medial aspect of the arm. There was no pain distal to the elbow joint. The patient revealed that he was a novice cross-country skier and that the pain severity gradually increased and became constant during cross-country skiing. The symptoms of pain and radiation were present during considerable exertion with cross-country skiing, mostly notably when skiing uphill. The symptoms would gradually abate with an easier skiing pace and with complete rest from any physical exertion. There were no other associated symptoms. There was no nausea, vomiting, diaphoresis, light headedness, dyspnea, syncope, anxiety, pallor, or feeling of impending doom. The pain and radiation into the medial aspect of the arm intensified over long periods of cross-country skiing, reaching an intensity of 8/10 on the numeric pain scale (NPS), with associated tachycardia, fatigue, and exhaustion.

The pain in the anterior aspect of the chest wall on the left and down the medial aspect of the left arm was completely relieved with rest. There was pain on palpation to the superior lateral aspect of the chest wall, pectoralis minor muscle, and pectoralis major muscle. Palpation of the superior lateral aspect of the chest wall, pectoralis minor muscle, and pectoralis major muscle revealed an increased sensation of pain over the proximal attachment of each muscle and also produced a slight increase in symptoms in the anterior aspect of the shoulder and down the medial aspect of the arm to the elbow joint.

Prior diagnostic workup included a stress electrocardiogram (ECG) several years prior due to a complaint of pain in the anterior aspect of the chest wall during an extended period of jet boat riding in heavy waves. The previous stress ECG was unremarkable. The attending physician diagnosed the subject with chest pain of chest wall origin based on the history, absence of signs and symptoms of cardiac ischemia, and prior ECG findings. No other diagnostic evaluation was completed at the time. No previous treatment was provided.

At the chiropractic clinic, neurological examination revealed a healthy, well-nourished male subject reporting pain in the anterior aspect of the chest wall on the left with radiation down the medial aspect of the left arm. Neurological examination was within normal limits and was composed of upper limb sensation (pain and light touch), motor evaluation (C5, 6, 7, 8, T1; graded 5/5), and myotendinous reflexes (C5, 6, 7; 2+ bilaterally). There was no evidence of muscular atrophy observed. Vital signs revealed a blood pressure of 106/62 mm Hg and a resting heart rate of 48 beats per minute. He has a body mass index of 25, a height of 165 cm, and a weight of 64 kg. The subject was active in most sports and reported a history of competitive marathon running. The patient has been a runner for the past 30 years with no significant injury.

The chiropractic assessment noted ongoing 8/10 NPS pain with cross-country skiing of considerable exertion, especially skiing uphill. The patient had no previous physical therapy or soft tissue management of the condition. The results of the physical examination revealed mild anterior head carriage and a decreased arm angle on the left side when side lying (shortened pectoralis minor test).7,8 Cervical spine active and passive ranges of motion were full, with extension and rotation causing mild pain bilaterally. Range of motion testing did not reproduce pain down the medial aspect of the arm. Motion palpation revealed restrictions in the lower cervical and upper thoracic spine. Passive and active ranges of motion of the shoulder were unremarkable. Orthopedic examination of the shoulder revealed negative O'Brian and Speeds tests. Thoracic outlet syndrome orthopedic testing revealed negative elevated arm stress test, Eden test (costoclavicular maneuver), and Wright test results (hyperabduction maneuvers). Resisted muscle testing of the rotator cuff muscles was normal (graded as 5/5). On palpation, tenderness over the acromioclavicular joint, but no hypermobility, was noted. Muscle tightness was noted in the left pectoralis minor muscle. The subject's left medial arm pain was reproduced on palpation of the pectoralis minor and major muscles. The patient was diagnosed with myofascial pain involving the pectoralis minor muscle with active trigger points in the pectoralis minor and major muscles on the left with a classic pain referral pattern.

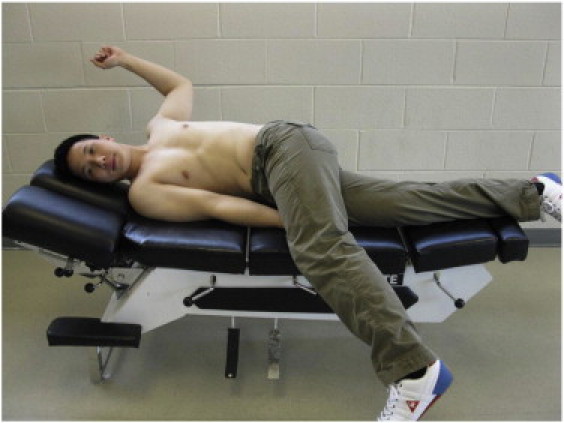

The subject reported that the pectoralis major and minor muscles were not evaluated by the previous practitioner (physician) who diagnosed him with anterior chest pain with chest wall origin. The subject was prescribed a manual therapy approach to reduce trigger point activation in the pectoralis minor and major muscles. The therapeutic intervention included instrument-assisted soft tissue technique to reduce trigger points in the pectoralis minor and major muscles. Graston Technique was performed on the subject on 4 separate visits. The Graston treatment protocols for pectoralis minor and pectoralis major were followed, using the GT1 and GT3 Graston tools. Before Graston treatment, the subject was instructed to increase core body temperature through 5 minutes on a Schwinn Airdyne bike and by heating the pectoral region with a warming bag. A gentle “Z” stretch of the pectoralis minor muscle and the pectoralis major muscle was also used during treatment and at home by the patient (the authors note that the ipsilateral piriformis muscle is stretched as well with full extension of the top leg), shown in Fig 1.

Fig 1.

“Z” stretch of the pectoralis minor muscle and the pectoralis major muscle.

After a series of 4 treatments over a period of 2 weeks to the pectoralis minor and pectoralis major muscles, the pain and referral patterns significantly decreased; he was able to continue cross-country skiing at considerable exertion with a reduction of symptoms after the second treatment. Advice to the subject to change his strokes in cross-country skiing to reduce the amount of use of the pectoralis minor muscle, as well as stretching of the pectoralis minor and pectoralis major muscles after skiing, prevented the recurrence of the subject's symptoms. Pain levels on exertion were measured after each treatment. By the second treatment, the subject rated his pain as 4/10 on the NPS, decreased from 8/10; and after the fourth treatment, the subject rated his pain as 0/10, demonstrating a complete resolution of pectoralis minor syndrome.

Discussion

Mechanical injuries of the anterior chest wall often need a high level of suspicion to diagnose. The most common form of anterior chest wall pain with exertion in a beginner athlete is usually mechanical in origin. Therefore, it is important to recognize the signs and symptoms of pectoralis minor muscle and pectoralis major muscle trigger point referral patterns.

Anatomy

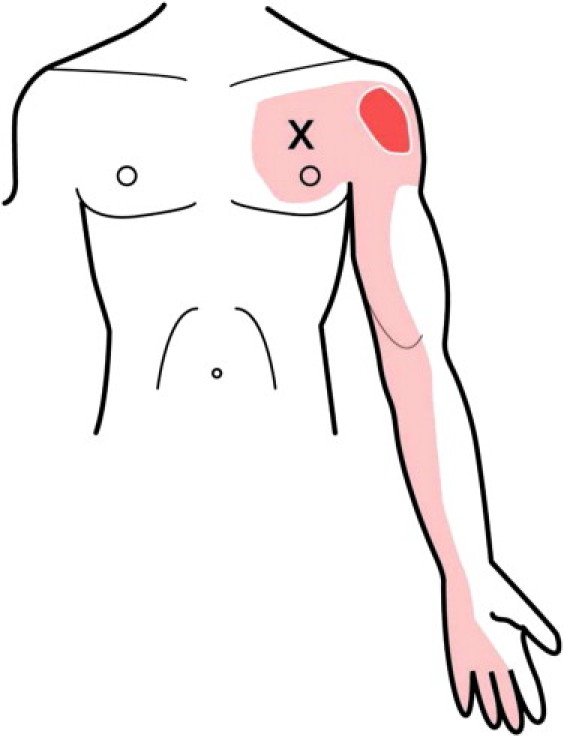

The pectoralis minor muscle attaches proximally on the third to fifth ribs near their costal cartilages and distally on the medial border and superior surface of the coracoid process of the scapula.9 The pectoralis minor muscle is innervated by the medial pectoral nerve (C8 and T1). The primary function of pectoralis minor muscle is stabilization of the scapula by drawing the scapula inferiorly and anteriorly against the thoracic wall.9 Simons et al3 described a pain referral pattern of pectoralis minor muscle as pain mostly over the anterior deltoid area and spilling over into the subclavicular and pectoral regions. The pain may extend down the medial aspect of the arm, forearm, and into the ulnar distribution of the hand and the third, fourth, and fifth digits (Fig 2). There is no distinction between an upper or lower pectoralis minor muscle trigger point. A trigger point in the pectoralis major or minor muscle may mimic cardiac ischemia.3

Fig 2.

Trigger point referral pattern for the pectoralis minor muscle.

Biomechanics

It has been described in the literature that there is a significant difference in the classic skate technique of cross-country skiing and the double poling technique. Furthermore, it has been hypothesized in the literature that there is a significant difference between a beginner cross-country skier and an elite-level cross-country skier with relation to the recruitment of the pectoralis minor and major muscles; the pectoralis minor muscle is often overused in beginner cross-country skiers when compared with elite-level cross-country skiers. Holmberg et al10 described the biomechanics of double pole skiing using electromyographic studies of the involved musculature using elite cross-country skiers. They found the abdominal muscles (rectus abdominis and external oblique) and the teres major to have the highest level of activation, followed by the latissimus dorsi and pectoralis major. Holmberg et al10 did not find a relationship between the recruitment of the pectoralis minor muscle and muscle recruitment patterns in elite-level cross-country skiers. Flexor carpi ulnaris, triceps, and biceps brachii were also recruited significantly in the upper body of the elite-level cross-country skiers. To analyze muscle sequencing, the onset and offset of muscle activity were determined, with the threshold defined as the level 2+ standard deviations greater than the mean base signal at rest. The recruitment sequence is as follows in elite-level cross-country skiers: trunk flexors (rectus abdominis, external oblique), teres major, latissimus dorsi and pectoralis major, triceps, biceps brachii, and flexor carpi ulnaris last. The abdominal muscles were the first to switch off, followed by the teres major, latissimus dorsi, pectoralis major, triceps, flexor carpi ulnaris, and biceps brachii last. Holmberg et al10 were able to characterize the subjects into “wide elbow” and “narrow elbow” skiers. The wide elbow group used more abduction in the shoulder joints and smaller elbow angles at pole plant, were faster, and more distinctly flexed elbow and hip joints during an altogether more dynamic poling phase (joint angles were measured using a goniometer). The narrow elbow group was opposite to the wide elbow group. With respect to the case presented in this article, the patient used wide elbow angles at pole plant.

Beginner skiers may not follow this pattern of muscle recruitment and activation, and instead may recruit other muscles, in particular the pectoralis minor. In this case report, the subject had recently taken up cross-country skiing and increased the intensity of activity shortly after. The beginner cross-country skier often does not use enough elbow extension and shoulder flexion to pull back using the latissimus dorsi and rhomboids. Instead, the motion often used is shoulder extension to pull back with bent elbows, placing an increased demand on pectoralis minor muscle. The pectoralis minor muscle is not often used in everyday life and is easily strained with overuse in cross-country skiing. In a 21-item questionnaire of 833 cross-country skiers performed by Butcher and Brannen,11 a trend was found toward more shoulder and elbow complaints in male cross-country skiers and more neck, back, and hip problems in female cross-country skiers.

To correct this mechanism while cross-country skiing, the subject in this case presentation was advised to flex the shoulders until the arm, hand, and pole handle were at eye level and to pull back, introducing elbow flexion until the elbows were at 90° and finishing with a wrist flick into ulnar deviation. This technique recruits larger muscles, that is, latissimus dorsi, rhomboids, and lower trapezius, and decreases the load on pectoralis minor. The subject's symptoms improved significantly with treatment and after making these changes to his cross-country skiing technique.

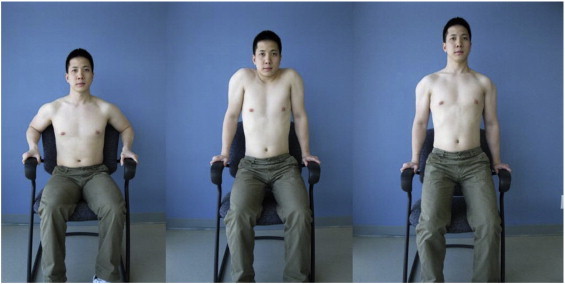

Additional exercise therapy

In addition to passive treatment and improving skiing technique, the stretch and strengthen motion shown in Fig 3 can be useful in the conservative management of a pectoralis minor strain.

Fig 3.

Stretching and strengthening exercise for the pectoralis minor.

Limitations

As with any case report, there are limitations. The results from this patient's treatment may not necessarily be expected when applied to other patients. It is possible that the patient improved regardless of the therapy. Larger clinical trials should be conducted to demonstrate the effectiveness of chiropractic management for pectoris minor pain and dysfunction. It is also important to note that a patient may have simultaneous conditions occurring at the same time and therefore may have a muscle as well as a cardiac condition; thus, cardiovascular disease should be ruled out.12

Conclusion

This case demonstrates the importance of a case history and understanding the biomechanics of the case-specific sport. Strain of pectoralis minor muscle should be considered as part of the differential diagnosis when assessing anterior chest pain, particularly in individuals who are beginners in cross-country skiing or who are using new body movements. Correction of posture and technique in cross-country skiing can help to diminish the progression and manifestation of symptoms.

Funding sources and potential conflicts of interest

No funding sources were reported for this study. Dr Lawson is a Graston Technique instructor.

References

- 1.Hess E.P., Wells G.A., Jaffe A., Stiell I.G. A study to derive a clinical decision rule for triage of emergency department patients with chest pain: design and methodology. BMC Emerg Med. 2008;6(8):3. doi: 10.1186/1471-227X-8-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stochkendahl M.J., Christensen H.W., Vach W., Hoilund-Carlsen P.F. Diagnosis and treatment of musculoskeletal chest pain: design of a multi-purpose trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;31(9):40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-9-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simons D.G., Travell J.G., Simons L.S. 2nd ed. Williams & Wilkins; Baltimore, MD: 1999. Travell & Simons' myofascial pain and dysfunction. The trigger point manual volume 1. Upper Half of Body. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhatia D.N., de Beer J.F., van Rooyen K.S., Lam F., du Toit D.F. The “bench-presser's shoulder”: an overuse insertional tendinopathy of the pectoralis minor muscle. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41(8):e11. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.032383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zvijac J.E., Zikria B., Botto-van Bemden A. Isolated tears of pectoralis minor muscle in professional football players: a case series. Am J Orthop. 2009;38(3):145–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jalil N.A., Prateepavanich P., Chaudakshetrin P. Atypical chest pain from myofascial pain syndrome of subscapularis muscle. J Musculoskelet Pain. 2010;18:173–179. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ko G.D., Whitmore S. Effective pain palliation in fibromyalgia patients with botulinum toxin type-A: case series of 25. J Musculoskelet Pain. 2007;15(4):55–66. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis J.S., Valentine R.E. The pectoralis minor length test: a study of the intra-rater reliability and diagnostic accuracy in subjects with and without shoulder symptoms. BMC Musculoskelet Disorders. 2007;8(64):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-8-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agur A.M.R., Dalley A.F. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Hong Kong: 2009. Grant's atlas of anatomy twelfth edition. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holmberg H.C., Lindinger S., Stoggl T., Eitzlmair E., Muller E. Biomechanical analysis of double poling in elite cross-country skiers. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;37(5):807–818. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000162615.47763.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butcher J.D., Brannen S.J. Comparison of injuries in classic and skating Nordic ski techniques. Clin J Sports Med. 1998;8:88–91. doi: 10.1097/00042752-199804000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumarathurai P., Farooq M.K., Christensen H.W., Vach W., Høilund-Carlsen P.F. Muscular tenderness in the anterior chest wall in patients with stable angina pectoris is associated with normal myocardial perfusion. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008;31(5):344–347. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]