Abstract

This paper systematically investigates the effects of solution viscosity, applied voltage, and DNA chain length on the distribution of DNA translocation times through 8±2 nm diameter silicon nitride nanopores. Linear dsDNA translocation events were selected based on the magnitude of current blockage and accumulated into scatter plots of current blockage and event duration (translocation time). The translocation time distribution was fit to the solution of a Smoluchowski-type equation for 1D biased diffusion to a sink. The DNA drifting speed under bias and diffusion constant were extracted from the fits as functions of solution viscosity, applied voltage, and DNA chain length. Combined with the Einstein–Smoluchowski relation, this model allowed evaluation of the viscous drag force on DNA molecules. This model also allowed estimation of the uncertainty in determining the DNA chain length due to the contribution of Brownian motion. The data analysis suggests that the simple 1D biased diffusion model fits the experimental data well for a wide range of conditions. Some deviations from predicted behavior were observed and show where additional phenomena are likely to contribute to the distribution of DNA translocation times.

Keywords: DNA translocation, diffusion constant, drifting velocity, nanopore

1. Introduction

The interplay between friction, electrophoretic driving force, and thermal motions imposes limits on the resolution of analytical methods based on nanopore translocation of DNA polymers. The distribution of translocation times for DNA passing through voltage-biased nanopores reflects this interplay and can therefore be exploited to evaluate resolution limits for sizing DNA molecules and the uncertainty in more detailed analysis such as detecting the location of a nucleotide on a DNA chain for sequencing analysis. The time duration of a DNA molecule passing through a nanopore determines its temporal resolution. The DNA translocation time in solid state nanopores has been studied experimentally [1–7] and theoretically [8–14].

This work analyzes the experimental data distribution of double stranded DNA linear translocation times through biased silicon nitride nanopores [2, 5]. The time distribution was studied as functions of solution viscosity, applied voltage, and DNA chain length. To simplify the approach, we first assume that the width of the time distribution is the result of 1D random walk of DNA molecules in a nanopore; we then compare the parameters obtained from the simple 1D biased diffusion model with the results from other experiments. The data analysis reveals the utility and limits of applicability of a 1D biased diffusion model of DNA translocation.

2. Methods

2.1. Experimental background

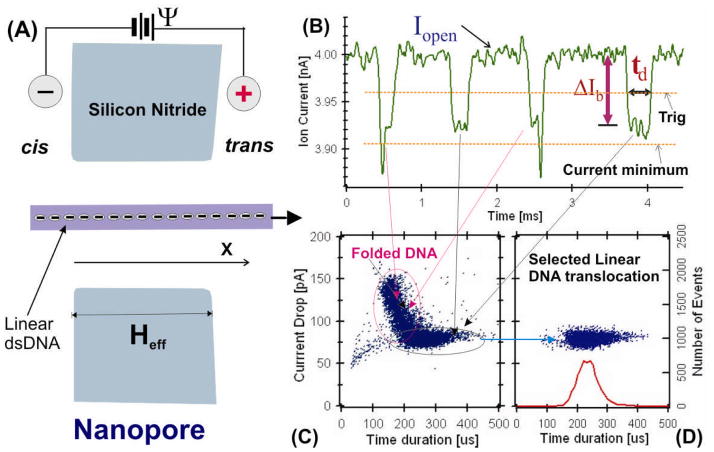

This work expands on previous experimental results that measured DNA translocation as a function of solution viscosity, bias voltage, and DNA chain length [2, 5]. Briefly, the experiment that detects DNA molecules translocation in a nanopore is illustrated in Fig. 1A. The nanopores used in this work were made in a silicon nitride membrane and are 8±2 nm in diameter. As shown in Fig. 1A, the silicon nitride membrane contains a nanopore separates two chambers connected electrically only by an ionic solution inside the nanopore. When a voltage is applied across the membrane, a stable open pore current I0 will be observed. After adding negatively charged DNA molecules to the cis chamber, the molecules in the vicinity of the nanopore will be captured by the electric field, and forced to pass through the nanopore to the positively biased trans chamber. The translocation of DNA molecules through a nanopore blocks the ionic current flow, produces transient ionic current blockages as shown in the pulses in Figure 1B. An integrated Axopatch 200B system (Molecular Devices) was used to perform the experiments. The 10 kHz low pass Bessel filter in the Axopatch 200B was selected for most of the measurements in this work, two sets of data for DNA chain length studies were recorded at 100 kHz filter as described in the Fig. 4 caption. The concentration of DNA molecules in the cis chamber was about 10 nM in this work. The salt solution used for the experiments were 1M KCl or 1.6M KCl plus glycerol with 10 mM TE buffer at pH 7.5±0.5. The data used in this work were measured with DNA molecules between 2.2 kbp (chain length LC=738 nm) to 23 kbp (LC=7820 nm). The chain length LC is much longer than the nanopore effective thickness (Heff ~20 nm [15]). The mean blockade current ΔIb was calculated from the current values below the trigger level and the time duration td was calculated as the time when the trigger line across the current pulses as shown in Fig. 1B using custom MatLab routines. Fig. 1C and 1D show scatter plots of ΔIb vs td to visualize the current blockage event distribution.

Figure 1.

(A) Illustration of linear DNA translocation experiment. (B) Typical 3 kbp DNA translocation events in a 8±2 nm diameter pore in 1.5 MKCl with 30% glycerol at pH 7.5. (C) All events distribution plot of current drop ΔIb vs translocation times td. (D) Selected linear translocation events plot from the data shown in (C).

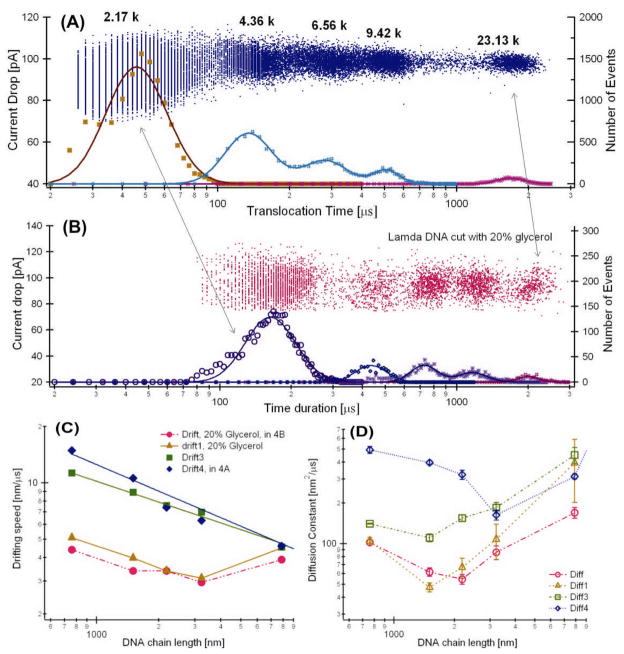

Figure 4.

(A) Event distribution plot of translocation of a DNA ladder (λ cut) that contains a mixture of ~2.17, 4.36, 6.56, 9.42, and 23 kbp DNA. The experiment was performed in 1.0 M KCl with no glycerol. More than 20,000 events are in this event distribution plot. (B) The experiment was performed in 1.6 M KCl with 20% glycerol. Both sets of data were recorded with low pass filter set at 100 kHz. The fitted drifting speed (C) and the diffusion constants (D) as a function of the DNA chain length. All data are measured with 10±2 nm silicon nitride pores and the applied voltage was 120 mV. The error bars for drifting speed in panel C are smaller than the markers for all the data points.

The DNA molecules used for the data in this work are from 3 kbp dsDNA (plasmid pSP65) and DNA ladder (Lambda hind III phage DNA) from New England Biolabs.

2.2. Linear translocation event selection

When the nanopores are 8±2 nm in diameter, DNA molecules translocate in either a linear or in a folded configuration [16]. Our earlier studies have shown that the events with one current blockage level are DNA molecules translocation in linear configuration, and the events with more than one blockage levels representing DNA passing a nanopore in partially folded form [16]. Several such events are shown in Fig. 1B and a typical event distribution plot is shown in Fig. 1C. In this work, we set up a current drop minimum and the current blockage levels below the minimum line (Fig. 1B) or folded events are not selected. The selected one current drop level events or linear translocation events are shown in Fig. 1D. We focus on the distribution of the time duration td histogram (on the bottom axis in Fig. 1D). We fit the time histograms to a first passage time distribution derived from a 1D biased diffusion model that describes a uniformly charged DNA polymer moving in a nanopore.

2.3. First Passage Time Distribution for Biased diffusion

We intend to estimate the range over which a 1D biased-diffusion model is adequate to describe dsDNA translocation. DNA translocation through a nanopore involves many phenomena. To simplify the problem, we assume free translocation and we ignore complex issues like DNA-pore interactions and electro-osmotic flow, and DNA (un)coiling in the (cis) and trans chambers. When the DNA molecule is captured by the strong electric field (~105V/cm) near the nanopore, the segment that is going through the pore must first unwind or uncoil. During translocation only a very small segment of the DNA chain is under the electric field. During translocation the uncoiling in the cis chamber will be compensated by the coiling in the trans chamber. The relaxation time of random coil is in the order of ~100 ms for a 10 kbp dsDNA [17], thus this (un)coiling effect is likely to contribute to the distribution of td. We therefore expect most of the deviations from 1D biased diffusion behavior to be a result of the insertion process. When the time of entrance becomes significant compared to the translocation times, we also expect deviations from the simple 1D model.

Here we briefly describe the derivation of the first passage time distribution for a charged polymer that has electrophoretic mobility ue and a diffusion constant D. In the simple 1D model described below, we assume that DNA molecules are uniformly charged long rodlike polymers with no flexibility. The polymer is located initially at position 0 to travel to a sink (trans chamber) located a distance Heff away when driven by an electric field ε = Ψ/Heff. The electric field only exerts an electrical force on the DNA polymer in the longitudinal direction of the nanopore within the range of Heff. The drifting velocity of the polymer is νd = ueε. Start with the Fokker Plank equation for the evolution of the position-time probability distribution function, we solve the 1-D Smoluchowski type diffusion equation below.

| (1) |

A general normalized solution of this equation with initial condition P(x,0)= δ(x) is

To account for the boundary condition at the exit of the nanopore, which we consider to be a sink beyond which the particle cannot return (absorbing boundary), P(dtrans, t)= 0, we introduce an image sink of amplitude A at position x0

The solution that satisfies this boundary condition is (with x0= 2(d-tv) and A=1)

Note, this solution is only valid for x≤d. When a DNA molecule has translocated to the “trans” chamber (outside of Heff) or for x>d,, the equation (1) is no longer valid so is its solution. The probability that a particle has not translocated (reached the boundary d, survived) is

The probability that a particle has translocated (reached the boundary and left the system) is

Substituting the definition of the drift velocity v = εue, the probability density function of the particle has reached the boundary is

| (2) |

This is the sojourn time (here t is the DNA translocation time td extracted from current drop events) distribution. d is the distance to be translocated. For a particle that is small with respect to Heff, d is just Heff. For a long polymer like DNA measured in this work, Lc≫Heff, d =LC+Heff is the DNA chain length LC plus the length of the pore Heff.

We fit P(t) of Equation (2) to the current blockage time histograms while holding the d =LC+Heff as a constant. We obtain the drifting velocity ν and the diffusion constant D from the fits.

3. Time Distribution Analysis

3.1. Solution Viscosity

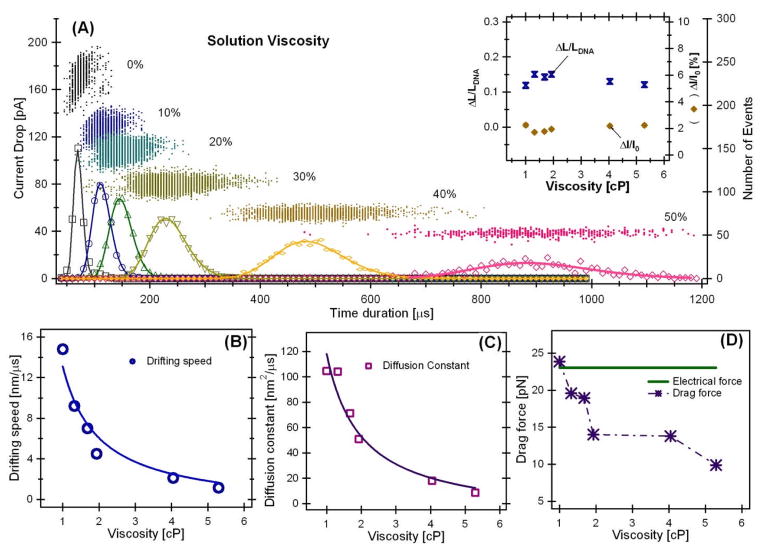

Adding glycerol increases aqueous solution viscosity and decreases solution conductivity. Fig. 2a shows the event distribution plot of 3 kbp DNA translocation in a nanopore as the glycerol percentage was increased from 0–50%. Glycerol decreased the current blockage amplitude ΔIb consistent with the decreased solution conductivity. To verify the translocation mechanism for selected events are the same linear translocation, we plot the relative blockade current ΔIb/Ib in the insert of Fig. 2a. The ΔIb/Ib (right axis) = 2.0±0.1% indicating that DNA molecules in the pore are in the same stretched conformation. Glycerol also increased the time durations td as expected from the higher solution viscosity. The time histograms on the bottom axis show that the distributions of the time durations td became broader as the viscosity increased.

Figure 2.

(A) Event distribution plot of 3 kbp (LC=1020 nm) DNA translocation as a function of solution viscosity in 1.5 M KCl, pH 7.5, and ψ=120 mV. Insert, left axis: the uncertainty in determine DNA chain length due to random walk ΔL/LDNA(

); right axis: the relative blockade current ΔI/I0 (◆). The error bars are smaller than the symbols. (B) The drifting speed, (C) the diffusion constant, and (D) the calculated drag force as a function of viscosity.

); right axis: the relative blockade current ΔI/I0 (◆). The error bars are smaller than the symbols. (B) The drifting speed, (C) the diffusion constant, and (D) the calculated drag force as a function of viscosity.

Fitting the distributions of the time durations on the bottom axis in Fig. 2A to Equation (2) are shown as the solid curves. The two fitting parameters: drifting velocity v and the diffusion constant D are plotted in Fig. 2B and 2C. Both the diffusion constant D and the drifting velocity ν are inversely proportional to the solution viscosity as expected from Einstein–Smoluchowski relation for charged particles described below.

| (3) |

and

| (4) |

Here Cfη =f is the friction coefficient. Cf is a friction constant that has a unit of “length” (for a spherical particle, Cf =6πr). Here Cf also includes the parameters we do not include in the equation. Since only a fraction, ~Heff/LC, of a DNA molecule is in the electric field, here we define ue*=ue( Heff/LC) is the “fraction mobility” of a DNA molecule. Q*= z* e0 is the instantaneous average electrical charge “interact” with the nanopore electric field while during translocation. The z* is the effective number of elementary charge (e0).

Values of Cf and Q*

Fitting the diffusion constants D vs solution viscosity η (solid curve, Fig. 2C), we obtained a fitting constant kBT/Cf=130.4±12 (×10−18 kg.nm/μs2). The estimated value of the friction constant is Cf≈31.6 nm with kBT =4.14×10−15 kg nm2/μs2. Fitting the drifting velocity ν as a function of η, resulted in a fitting constant (z*e0)ψ/(LCCf) = 14.1±0.8 (×10−18 kg/μs2). Using ψ =0.12 V and LC=1020 nm, the estimated value of the “instantaneous electrical charge” of a DNA molecule is Q* =23.7e0 ~ 24e0. The estimated linear charge density is ~24 e0/20nm or ~1.2e0/nm, here we have used Heff ~20 nm [15]. This is close to the values measured (~2e/nm or ~0.3e per phosphate) for linear charge density of DNA in ~1M KCl.

Drag Force

Using known values of Cf, η, ν, and Q*, we can further estimate how the drag force changes as solution viscosity varies, Fdrag = fv(LC/Heff)=Cfηv(LC/Heff). The electrical driving force=Q*E assuming that Q* does not change as solution viscosity changes. Both Q*E and Fdrag are shown in Fig. 2D. This analysis suggests that the estimated electrical driving force exerted on a DNA molecule would be ~23 pN. The drag force calculated decreased as the solution viscosity increased indicating that either the simple model for calculating the drag force was not accurate or the electrical charge Q* could have decreased at higher solution viscosity. It is unlikely that the electrical charge Q* could decrease by a factor of 2 due to viscosity, thus most likely the drag force calculated from the simple model could not count for all the forces that balance the electrical driving force.

Uncertainty of measuring LC

In addition, we can also estimate the uncertainty or resolution limit of determining the chain length of a DNA, ΔLC, by the nanopore measurement due to Brownian motion by

| (5) |

The insert in Fig. 2A shows the calculated values of ΔLC/LC from Eq. (5). Increasing DNA translocation time does overall slightly decrease the error in measuring a DNA’s length, but the improvement is very limited. This analysis shows that the error in determining the chain length of a DNA, ΔLC/L, is about 12–15%.

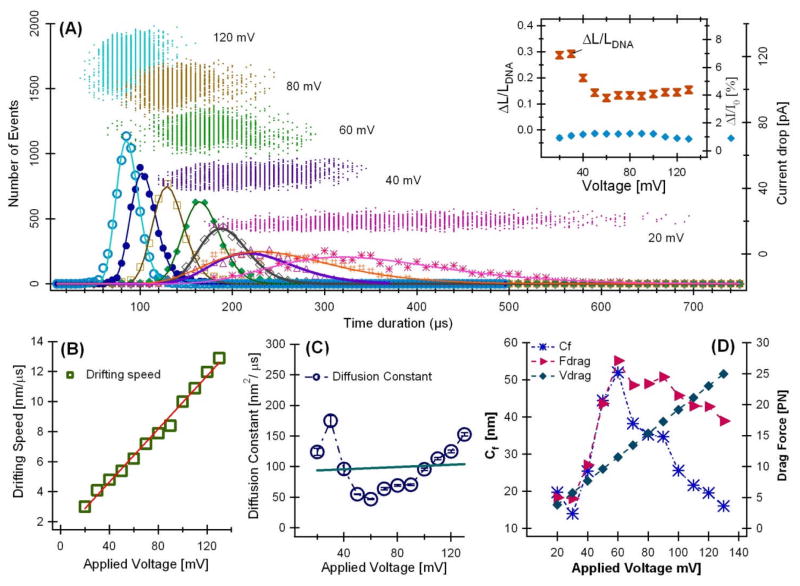

3.2. Bias Voltage

Changing applied voltage from ψ =130 to 20 mV, the time distributions (on the bottom axis) and several event distributions are shown in Fig. 3a. We plot the relative blockade current ΔIb/Ib in the insert of Fig. 3a to verify the translocation mechanism for selected events. The ΔIb/Ib (right axis) = 1.1±0.1% indicating that DNA molecules in the pore are in the same linear translocation configuration. Fitting the time distributions to the equation (2), we obtained the drifting velocities ν (Fig. 3b) and the diffusion constants D (Fig. 3c) as a function of ψ.

Figure 3.

(A) Event distribution plot of 3 kbp DNA translocation as a function of applied voltage. Insert, left axis: the uncertainty in determine DNA chain length due to random walk ΔL/LDNA(

); right axis: the relative blockade current ΔI/I0 (◆). The error bars are smaller than the symbols. (B) The drifting speed, (C) the diffusion constant, and (D) the calculated drag force as a function of voltage. The experiment was performed in 1.6 M KCl with 20% glycerol at pH 7.5 in a 8±2 nm silicon nitride pore.

); right axis: the relative blockade current ΔI/I0 (◆). The error bars are smaller than the symbols. (B) The drifting speed, (C) the diffusion constant, and (D) the calculated drag force as a function of voltage. The experiment was performed in 1.6 M KCl with 20% glycerol at pH 7.5 in a 8±2 nm silicon nitride pore.

Drifting Speed

Fitting the drifting speed ν as a function of the applied voltage ψ with a straight line, ν = slope*ψ, the slope=1.1±0.2 (nm/Vμs). Let the slope= ue*/Heff = ue/LC, using Heff =20 nm and LC=1020 nm, the estimated segmental mobility of DNA translocation in this nanopore is ue* =22 nm2/(Vμs) = 2.2 × 10−11 m2/Vs. The estimated electrophoretic mobility of the 3 kbp DNA is ue =1.12×103 nm2/(Vμs) or ~10−9 m2/Vs, which is one order of magnitude smaller than the values (3×10−8 m2/Vs) measured by gel electrophoresis for DNA of similar lengths [18]. The estimated smaller electrophoretic mobility could be due to: (1) the electric force only drag very small segment of a long DNA chain that could make a DNA less mobile; (2) we have ignored the DNA-pore interaction and electro-osmotic flow; and (3) the viscous drag on the chain portion in the cis and trans side is also neglected [19], all of these three factors could reduce DNA translocation velocity in silicon nitride pores.

Diffusion Constant

The average value of the diffusion constant is D = 99 ± 44 nm2/μs (or μm2/s, or ~10−10 m2/s (Fig. 3c). This value is about two orders of magnitude larger than the values (~10−12 m2/s) measured by gel electrophoresis at lower ionic strength conditions [20]. This shows that the “Diffusion constants” obtained by fitting the experimental data to the simple 1D-biased diffusion model deviate significantly from the bulk values. This is an important result as it suggests the underlying DNA translocation process is not as simple as the 1D biased diffusion model assumed.

During the translocation process of a DNA molecule in a nanopore, only a very small segment of the long DNA molecule is in the electric field due to Heff≪Lc. The segment that is going through the pore must first unwind at the entrance of the nanopore. The motion of the two random coiled ends of the DNA chain in the cis (unwinding) and trans (winding) chambers is likely contributes significantly to the distribution of the time duration or the peak width of the tds histograms.

The peak width of the time histograms is in Eq.(2). If the 1D Brownian motion was the only contribution to the peak width as the model assumed, then the “Diffusion constants” values from the fits should be close to the numbers in the bulk. However, if the DNA “Diffusion constants” in nanopores is two orders of magnitude larger than bulk, then it suggests that the processes other than “1D diffusion” are likely to contribute significantly to the time duration distribution. As we stated in the section 2.3, we therefore expect most of the deviations from 1D biased diffusion behavior to be a result of the insertion process or the unwinding process of the coiled DNA molecules at the nanopore entrance. In conclusion, our analysis shows that the DNA unwinding or the insertion process is likely to contribute to the time duration distribution significantly and could contribute to the deviations observed. However, the unwinding effect is beyond the scope of this paper.

If the DNA unwinding and insertion process contribute significantly to the time duration distribution (peak width), since the unwinding of DNA will depend on the electrical force as well as the drag force, thus the diffusion constants obtained from the fits as well as the calculated Cf are expected to change with the electrical field as we observed in Fig. 3c and 3d.

Drag force

Using the diffusion constants from Fig. 3c, we calculate the Cf using equation (3) and further calculate how the drag force changes as the voltage varies, Fdrag = fv(LC/Heff)=Cfηv(LC/Heff). Assuming the instantaneous average electrical charge Q* is approximately a constant, the electrical driving force on a DNA is Vdrag= Q*E. The estimated Cf, Fdrag, and Vdrag are shown in Fig. 3D. This analysis suggests: (1) the drag force is about 20 pN on DNA molecules when the bias voltage is above 60 mV which is in good agreement with the values measured by single molecule force measurement [21]; (2) The calculated drag force (▸) does not agree well the predicted electrical driving force (◆).

Entropic barrier

The diffusion constant analysis above also indicates that there is a barrier for DNA entering the pore. This has been studied and reviewed by Muthukumar [22] who proposed that there is an entropic barrier for DNA transport through pores.

If we assume there is an entropic barrier when DNA molecule is entering a pore, when the applied voltage ψ is less than the barrier height Hb, the translocation process is likely partially thermally activated. Three consequences would happen if ψ is less than Hb: 1) The electric field is not strong enough to bend a DNA molecule at the entrance of a nanopore thus the DNA molecule is less likely passing through in folded configuration. 2) More collision events should be observed at lower voltage as a DNA molecule is more likely to be bounced back to the cis chamber if it is in folded configuration; 3) the 1D biased diffusion model analysis would deviate from the DNA translocation process. All of the three consequences are consistent with the experimental results and data analysis. For example, at ψ =20 mV, most of the DNA current blockage events only had one level current drop (data not shown). We estimate the entropic barrier height is likely in the order of 60 mV as Fig. 3D shows a transition at ψ=60 mV.

Uncertainty of measuring LC

As shown in the insert of Fig. 3a, the accuracy of measuring the chain length of the 3 kbp DNA, ΔLC/Lc, improved from ~30% to ~12% when the applied voltage ψ increased from 20 mV to 50 mV. This indicates when the applied voltage ψ is less than 50 mV, the Brownian motion is likely comparable to the electrophoretic movement, thus, even a longer translocation time at lower voltage allows more accurate measurement of the current blockage signal; the random motion or “diffusion” effect of the DNA chain could cancel the benefit of longer measurement of time.

3.3. DNA Length

Using the data measured with a DNA ladder that contains a mixture of 2.17 (a mixture of 2027 and 2322 bp), 4.36, 6.56, 9.42, and 23 kbp DNA, we evaluate how time distributions change as a function of DNA length. Figure 4 shows the results of 4 sets of measurements performed with 4 different nanopores. In the event distribution plots without glycerol (Fig. 4A) and with 20% glycerol (Fig 4B) show that the time durations measured in a more viscous solution are longer as expected. Both sets of the distribution plots were measured at 100 kHz low pass filter. The peaks corresponding to different chain lengths are better separated with 20% glycerol. Longer time durations have wider time distributions as the DNA chain length was increased. The solid curves are best fits of the time histograms to Equation 2 while holding the DNA chain lengths as constants. The 2.17 kbp DNA peak is wider and has larger errors likely because it is an unresolved mixed peak from DNAs of 2027 and 2322 bp.

Drifting Speed

As shown in Fig. 4c, the drifting velocities were faster for the DNA measured without glycerol (square and diamond markers) compared to the data measured with 20% glycerol (circular and triangle markers). For the DNA measured without glycerol, the drifting velocity νd decreased approximately with a power law, νd = cL−α as the DNA chain length was increased. We fit the drifting velocity νd data with the power law and obtained exponents of α = 0.37 ± 0.02 and α = 0.47 ± 0.08. If we convert the drifting velocity to translocation time using td=LDNA/νd, then td ~L1.37 or td ~L1.47, respectively. These values are qualitatively in agreement with the value, tdwell ~L1.26, measured by Storm et al [3]. However, for slower translocations (with 20% glycerol in the solution), only when the DNA chain length is between 2.2 to 9.4 kbp, the drifting speed decreased approximately with a power law. For the very long chain length LC~23,13 kbp DNA, it seems the drifting speed value reached a constant, νd ~ 5 nm/μs. Analysis of a even longer DNA, λ DNA (48.5 kbp or LC=16,490 nm), the value of νd was ~ 5.4 nm/μs (data not shown) also supports this observation.

Diffusion Constants

The diffusion constants obtained from fitting the time histograms to equation (2) are shown in Fig. 4d. The diffusion constant values are D ~ 102 nm2/μs (μm2/s) for LC between 2.2 to 23 kbp (0.7–9 μm). Comparing to the values (~100μm2/s) measured by gel electrophoresis [18, 20], the diffusion constants estimated from the nanopore experiment are two order of magnitude larger; and the diffusion constant did not seem to scale with the DNA chain length as a power law, D ~ L−β.

The two order of magnitude larger value of D is likely caused by the fact that in a nanopore measurement, only a very small segment of DNA chain is in the electric field. That the scale of the diffusion constants (D) did not follow the power law may be due to the change of the entropic barrier height with DNA length. As the DNA chain length LC increases, the entropic barrier height (Hb) for DNA entering the pore is expected to be larger, or the translocation process is more thermally activated for longer DNA, thus higher voltage is needed for longer DNA translocation to be electrophoretic driven. This hypothesis is consistent with the fact that the transition for the D from decrease to increase is at longer LC for faster translocations (no glycerol data) shown in Fig. 4d. This hypothesis predicts that at higher enough voltages (ψ is higher than the barrier height), the power law, D ~ L−β, is expected to be observed. Further investigation is needed to test this hypothesis and to understand the diffusion constants magnitude scaling with DNA chain length shown in Fig. 4d.

4. Summary

In this work we have analyzed the time distribution of DNA linear translocation in ~10 nm diameter silicon nitride nanopores using a 1D biased diffusion model. This model was used to analyze the experimental data and to quantitatively extract diffusion constant and drifting speed. The analysis of the changes of these parameters as functions of solution viscosity, bias voltage, and DNA chain length allows better understanding about DNA translocation in solid-state nanopores. Our analysis shows that both the DNA drifting speed and diffusion constant are inversely proportional to the solution viscosity as expected. The DNA drifting speed is proportional to the bias voltage and obeys power law as the DNA chain length is less than 10 μm. The simple 1D biased diffusion model was consistent with many of the features of the data, but the values of the diffusion constants obtained are two orders of magnitude larger than the values in bulk. This suggests the processes of DNA unwinding and insertion at the entrance of the nanopore is likely to contribute significantly to the DNA translocation dynamics. Our analysis shows that more investigation is needed to understand the distribution of DNA translocation times in solid-state nanopores.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge discussion and criticism of this work by D. Hoogerheide and J. Golovchenko. Dr. D. Fologea and co-authors performed the original experiments published in references [2] and [5]. This work is supported by NIH R21HG003290 and NIH R21HG004776 to JL, and Supported by NIH R01GM071684 to DST.

References

- 1.Chen P, Gu J, Brandin E, Kim YR, Wang Q, Branton D. Nano Letters. 2004;4(11):2293–8. doi: 10.1021/nl048654j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fologea D, Uplinger J, Thomas B, McNabb DS, Li J. Nano Lett. 2005;5(9):1734–1737. doi: 10.1021/nl051063o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Storm AJ, Chen JH, Zandbergen HW, Dekker C. Phys Rev E. 2005;71 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.71.051903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Storm AJ, Storm C, Chen J, Zandbergen H, Joanny JF, Dekker C. Nano Lett. 2005;5(7):1193–1197. doi: 10.1021/nl048030d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fologea D, Brandin E, Uplinger J, Branton D, Li J. Electrophoresis. 2007;28:3168–3192. doi: 10.1002/elps.200700047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gershow M, Golovchenko JA. Nat Nanotechnol. 2007 DECEMBER;2:775–779. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wanunu M, Sutin J, McNally B, Chow A, Meller A. Biophys J. 2008 November;95:4716–4725. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.140475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lubensky DK, Nelson DR. Biophys J. 1999;77:1824–1838. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77027-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meller A. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter. 2003;15:R581–R607. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berezhkovskii AM, I, Gopich V. Biophys J. 2003;84:787–793. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74898-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forrey C, Muthukumar M. J Chem Phys. 2007;127(1) doi: 10.1063/1.2746246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lua RC, Grosberg AY. Phys Rev E. 2005;72 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.72.061918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lathrop DK, Ervin EN, Barrall GA, Keehan MG. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;32(6):1878–1885. doi: 10.1021/ja906951g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mathe J, Aksimentiev A, Nelson D, Schulten K, Meller A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(35):12377–12382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502947102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Talaga D, Li J. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:9287–9297. doi: 10.1021/ja901088b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li J, Gershow M, Stein D, Brandin E, Golovchenko JA. Nat Mater. 2003;2:611–615. doi: 10.1038/nmat965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doi M, Edwards SF. The Theory of Polymer Dynamics. New York: Oxford University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stellwagen E, Lu Y, Stellwagen NC. Biochemistry. 2003;42:11745–11750. doi: 10.1021/bi035203p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gauthier MG, Slater GW. J of Chem Phys. 2008;128 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robertson RM, Laib S, Smith DE. PNAS. 2006;103(19):7310. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601903103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keyser UF, Koeleman BN, Dorp Sv, Krapf D, Smeets RM, Lemay SG, Dekker NH, Dekker C. Nature Physics. 2006;2:473–477. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muthukumar M. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2007;36:435–450. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.36.040306.132622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]