Abstract

Purpose

To determine the incidence and classification of new-onset epilepsy, as well as the distribution of epilepsy syndromes in a population-based group of children, using the newly proposed Report of the ILAE Commission on Classification and Terminology 2005–2009.

Methods

We identified all children residing in Olmsted County, MN, 1 month through 17 years with newly diagnosed epilepsy from 1980–2004. For each patient, epilepsy was classified into mode of onset, etiology, and syndrome or constellation (if present). Incidence rates were calculated overall and also separately for categories of mode of onset and etiology.

Results

The adjusted incidence rate of new-onset epilepsy in children was 44.5 cases per 100,000 persons per year. Incidence rates were highest in the first year of life and diminished with age. Mode of onset was focal in 68%, generalized/bilateral in 23%, spasms in 3% and unknown in 5%. Approximately half of children had an unknown etiology for their epilepsy, and of the remainder, 78 (22%) were genetic and 101 (28%) were structural/metabolic. A specific epilepsy syndrome could be defined at initial diagnosis in 99/359 (28%) children, but only 9/359 (3%) had a defined constellation.

Conclusion

Nearly half of childhood epilepsy is of “unknown” etiology. While a small proportion of this group met criteria for a known epilepsy syndrome, 41% of all childhood epilepsy is of “unknown” cause with no clear syndrome identified. Further work is needed to define more specific etiologies for this group.

Keywords: Pediatric epilepsy, incidence, epilepsy syndrome

1.1 Incidence

The reported incidence of new-onset seizures in children has shown considerable variation, depending on inclusion criteria. Some studies have included only children with two or more seizures, whereas others have included all first seizures, febrile seizures or neonatal seizures. A small number of population-based studies have reported on the incidence of new-onset epilepsy in developed countries, with the reported incidence ranging from 33.3 to 82 cases per 100,000 persons per year (Blom et al., 1978, Camfield et al., 1996, Cavazzuti, 1980, Doose and Sitepu, 1983, Freitag et al., 2001, Hauser et al., 1993, Larsson and Eeg-Olofsson, 2006, Adelow et al., 2009, Christensen et al., 2007, Olafsson et al., 2005). Incidence rates have been consistently reported as highest in the first year of life, and as slightly higher in boys than girls.

As epilepsy is a heterogenous disorder, with marked variation in severity and prognosis, further classification of epilepsy is crucial. The most current ILAE Commission on Classification and Terminology report classifies epilepsy based on (1) mode of onset, (2) etiology and (3) syndrome or constellation, if present (Berg et al., 2010). Such epidemiological data is important to allocate health care resources and compare incidence and prevalence rates as well as etiologies, possible preventable causes, and treatment response among different populations. In addition, for a given patient, delineation of a specific epilepsy syndrome assists with choice of further investigations and therapies, and provides a more accurate prognosis regarding seizure and cognitive outcome. Several studies have reported the incidence of epileptic syndromes in a population-based sample, but were conducted prior to the most recent ILAE Classification Report (Loiseau et al., 1990, Zarrelli et al., 1999). One study focused exclusively on the pediatric population, but included only 36 children (Freitag et al., 2001).

The aim of this study was to determine the incidence and classification of new-onset epilepsy, as well as the distribution of epilepsy syndromes in a population-based group of children, using the newly proposed Report of the ILAE Commission on Classification and Terminology 2005–2009 (Berg et al., 2010).

2.1 METHODS

2.1.1 Case Identification

Cases were ascertained by screening of the complete diagnostic indexes of the Rochester Epidemiology Project. These indexes include inpatient diagnoses, as well as diagnoses at the time of outpatient and emergency room visits at all medical care facilities in Olmsted County, MN (Melton, 1996). All charts were screened using a diagnostic rubric which included all seizure and convulsion diagnosis codes, and all identified charts were reviewed by a pediatric epileptologist. We identified all children aged 1 month through 17 years with new onset epilepsy diagnosed while residing in Olmsted County, Minnesota, between 1980 and 2004. Date of epilepsy diagnosis was defined as the date the child or teen was first given the diagnosis of epilepsy by a physician.

2.1.2. Definitions

Epilepsy was defined as a predisposition to unprovoked seizures. Most subjects had two or more unprovoked seizures. However, patients with a single unprovoked seizure who had evidence of an enduring alteration of the brain that increases the likelihood of further seizures (Fisher et al., 2005), and who were commenced on antiepileptic drug treatment were also included. An abnormal neurodevelopmental examination, focal abnormality on brain imaging, initial presentation in status epilepticus, or specific EEG findings (epileptiform discharge, intermittent rhythmic focal delta activity) were considered indicative of an enduring alteration of the brain that increases the likelihood of further seizures. Patients who were treated after a single seizure, but who lacked any of the preceding features were excluded. We included children who had two afebrile seizures occurring within 24 hours as these children likely have epilepsy (Camfield and Camfield, 2000).

Children presenting with acute symptomatic seizures alone, defined as “seizures at the time of a systemic insult or in close temporal association with an acute neurological insult” (Beghi et al., 2010) were excluded. Similarly, children who had only febrile seizures were excluded. Children with neonatal seizures were included only if their seizures recurred after one month of age.

2.1.3. Data obtained from chart abstraction

Data variables abstracted from the medical charts are shown in Table 1. Magnetic resonance imaging was not routinely used until 1984. Epilepsy outcome at 1, 2, 3, 5, 10, 15 and 20 years after epilepsy onset regarding both seizure control (ongoing seizure frequency or seizure-free for the previous year or longer at each time point) and anti-epileptic drug treatment (number of current medications and number of medications failed for lack of efficacy at each time point) was noted. Additionally, epilepsy surgery procedures (resection, vagal nerve stimulator, corpus callosotomy) and use of a ketogenic diet were recorded. Cognitive function was assessed both at the time of seizure onset and last follow-up. Either formal neuropsychological testing (if available) or best clinical judgment by the reviewer, based on developmental milestones and academic achievement recorded in the patient history were used to classify cognitive function as normal (estimated or measured developmental quotient of 80 or higher), mildly to moderately delayed (estimated or measured developmental quotient of 50–79), or severely delayed (estimated or measured developmental quotient of <50).

Table 1.

Data abstracted from medical records

| Demographic | Age at follow-up |

| Sex | |

| Past history | Prenatal complications |

| Gestational age | |

| Perinatal problems (NICU < 7 days, NICU ≥ 7 days) | |

| Postnatal brain injury (head injury, meningitis, encephalitis, ischemic brain injury, other) | |

| Febrile seizures (prolonged, focal, clustering) | |

| Epilepsy Details | Seizure type(s) and number/frequency at diagnosis |

| Age at onset of epilepsy | |

| History of status epilepticus at diagnosis or ever | |

| Family history of epilepsy in first degree relatives | |

| Neurological examination | Normal/abnormal and type of abnormality |

| Neuroimaging findings | Magnetic resonance imaging - type and location |

| Computerized tomography - type and location | |

| EEG findings | Epileptiform and nonepileptiform abnormalities at diagnosis, within the first two years of diagnosis and at final followup |

2.1.4. Epilepsy Classification

For each patient, epilepsy was classified using the new ILAE Commission on Classification and Terminology 2005–2009 Report (Berg et al., 2010). Factors considered in the classification included seizure type(s) based on descriptive semiologies from the medical record, EEG and neuroimaging findings, cognitive function, and for some specific syndromes, age at onset.

According to the new classification scheme, epilepsy was classified based on mode of onset (generalized/bilateral cortical or subcortical, focal/networks limited to one hemisphere, unknown, or spasms) and etiology (genetic, structural/metabolic or unknown). Mode of onset was classified as generalized/bilateral in onset if the patient had generalized seizures and generalized epileptiform discharge on EEG, and as focal if the subject had focal-onset seizures, and either an EEG or neuroimaging showing a focal abnormality or normal studies. Additionally, epilepsy was classified as focal if children had generalized tonic-clonic seizures but focal findings on neurological examination, EEG or neuroimaging. Mode of onset was considered unknown if subjects had generalized tonic-clonic seizures, a normal exam, and unremarkable EEG and neuroimaging studies. The mode of onset for children who presented with spasms, but who later developed other seizure types, was characterized as spasms. However, children who initially presented with either focal or generalized seizures, but who developed spasms later in their epilepsy course were defined based on their presenting seizure type.

Subjects were classified as genetic if they had a known genetic mutation for their epilepsy, or if they had an epilepsy syndrome which is known to have a strong genetic contribution, such as the idiopathic generalized epilepsies or autosomal dominant frontal lobe epilepsy. Based on the recommendation of the Classification Commission, the “idiopathic focal epilepsies” including benign epilepsy of childhood with centrotemporal spikes and benign epilepsy with occipital paroxysms were classified as unknown etiology. Additionally, patients with neurocutaneous syndromes which give rise to structural abnormalities were classified as having a structural etiology, as opposed to a genetic etiology. (Berg et al., 2010).

Subjects were further classified into individual specific syndromes and constellations, if applicable, based on ILAE criteria. Specific syndrome designation was assessed both at initial presentation, based on data available at initial diagnosis, and at final follow-up, based on all clinical data available at final follow-up. The term “constellation” was used for an “entity that was not recognized as an electro-clinical syndrome per se, but which represents a distinctive constellation on the basis of a specific lesion or other cause” (Berg et al., 2010). It was proposed that defining constellations may have implications for clinical treatment, particularly surgery. Two pediatric epileptologists (ECW and KCN) independently reviewed the medical documentation of each incident case and classified the epilepsy and syndrome (if identified) based on the ILAE Commission on Classification and Terminology 2005–2009 Report (Berg et al., 2010). When there was disagreement, a final consensus was reached by joint review of the case.

2.1.5. Data Analysis

Incidence rates were calculated overall, and separately within strata defined by age and sex (1 to 6 months, more than 6 months to age 12 months, more than 12 months to age 60 months, more than 60 months to age 108 months, more than age 108 months to age 156 months and more than 156 months to age 216 months). Incidence rates were also calculated separately for categories of mode of onset and etiology of epilepsy. Because the number of children was small in the groupings by syndrome and constellations, we only report frequencies for these groups. Incidence rates were additionally calculated separately in boys and girls across five calendar year periods (1980–84, 1985–89, 1990–94, 1995–99, and 2000–04). Poisson rate regression was performed to test for significant trends in incidence rates across calendar year. Incidence rates are also reported age- and sex- standardized to the year 2000 total U.S. pediatric population (www.census.gov).

The denominators for all incidence rates were determined using the complete enumeration of the Olmsted County population via the Rochester Epidemiology Project (Melton 1996). Specifically, the number of resident children in each age and sex stratum on July 1 of each of the years 1980 through 2004 was used.

3.1. RESULTS

We identified 359 cases fulfilling criteria for new-onset epilepsy diagnosed over the 25-year period from 1980–2004 in children aged 1 month through 17 years. All children except three were seen on at least one occasion by a child neurologist who confirmed the diagnosis of epilepsy. Of the remaining three, two were diagnosed with epilepsy by a general neurologist, and one by a pediatrician. Prophylactic antiepileptic drug therapy was commenced in 339 patients while 20 were never treated. Forty nine were started on medication after their first afebrile seizure, and of these, 34 had subsequent seizures despite medication. Fifteen had only a single seizure, but had one or more features predicting higher rate of recurrence (specified in Methods) and were commenced on antiepileptic drug therapy without recurrence. One hundred and ninety six (55%) children were male. The median age at epilepsy onset was 63.8 months (minimum 0 months, 25th percentile 26.9 months, 75th percentile 119.9 months, and maximum 215.5 months). Children were followed for a median of 138.1 months after diagnosis of epilepsy (minimum 0 months, 25th percentile 82.7 months, 75th percentile 207.7 months, and maximum 353.8 months).

3.1.1. Classification of Incident cases of epilepsy and epilepsy syndrome

Children were classified based on mode of onset of epilepsy, etiology of epilepsy, and syndrome and constellation characteristics (Table 2). Initial disagreement regarding classification between the two epileptologists reviewing the records was present in 15 (4.2%) cases, but was resolved with further discussion. The predominant mode of onset was focal, which accounted for 244 (68%) of cases. Generalized/bilateral onset was seen in 84 (23%) and spasms in just 10 (3%). Nineteen patients (5%) had an unknown mode of seizure onset. Two children had both focal and generalized onset seizures at presentation, and over time, three more developed seizures with both modes of onset. Not surprisingly, mode of onset was correlated with age. Spasms were seen significantly more frequently with younger age at onset [9/50 (18%) of children with seizure onset before 12 months, 1/254 (0.4%) of those with onset between 12 and 156 months, 0/55 (0%) of those with onset between 156 and 216 months (p<0.001)]. Among the patients with a classifiable mode of onset, generalized/bilateral seizure onset was more common with increasing age at onset [7/47 (15%) of children with onset <12 months, 59/244 (24%) of children with onset 12–156 months, 20/49 (41%) whose seizures began after 156 months (p<0.02)]. The proportion of children with focal onset seizures was significantly higher in children with age at onset 12–156 months (186/244, 76%) than in those with onset <12 months (31/47, 66%) or after 156 months (29/49, 59%) (p<0.02). Sex did not correlate with mode of seizure onset.

Table 2.

Distribution of new-onset epilepsy cases by based on ILAE Commission on Classification and Terminology 2005–2009.

| Boys | Girls | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Mode of Onset | |||||

| i. | Generalized | 42 | 42 | 84 | ||

| ii. | Focal | 139 | 105 | 244 | ||

| iii. | Unknown | 11 | 8 | 19 | ||

| iv. | Spasms | 4 | 6 | 10 | ||

| v. | Both focal and generalized | 0 | 2 | 2 | ||

| 2. | Etiology | |||||

| i. | Genetic | 39 | 40 | 79 | ||

| ii. | Structural/metabolic | 60 | 40 | 100 | ||

| iii. | Unknown | 96 | 83 | 179 | ||

| iv. | Both genetic and structural | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 3. | Electroclinical syndrome at initial diagnosis | |||||

| a. | Neonatal period | |||||

| i. | Benign familial neonatal epilepsy | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| ii. | Early myoclonic encephalopathy | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| iii. | Ohtahara syndrome | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| b. | Infancy | |||||

| i. | Epilepsy of infancy with migrating focal seizures | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| ii. | West syndrome | 4 | 5 | 9 | ||

| iii. | Myoclonic epilepsy in infancy | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| iv. | Benign infantile epilepsy | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| v. | Benign familial infantile epilepsy | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| vi. | Dravet syndrome | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| vii. | Myoclonic encephalopathy in nonprogressive disorders | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| c. | Childhood | |||||

| i. | Febrile seizures plus (FS+) | 4 | 3 | 7 | ||

| ii. | Panayiotopoulos syndrome | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| iii. | Epilepsy with myoclonic atonic seizures | 2 | 0 | 2 | ||

| iv. | Benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes | 14 | 12 | 26 | ||

| v. | Autosomal dominant frontal lobe epilepsy | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| vi. | Late onset childhood occipital epilepsy | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| vii. | Epilepsy with myoclonic absences | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| viii. | Lennox-Gastaut syndrome | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| ix. | Epileptic encephalopathy with CSWS | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| x. | Landau-Kleffner syndrome | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| xi. | Childhood absence epilepsy | 7 | 10 | 17 | ||

| d. | Adolescence/Adult | |||||

| i. | Juvenile absence epilepsy | 4 | 7 | 11 | ||

| ii. | Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy | 2 | 9 | 11 | ||

| iii. | Epilepsy with GTC seizures alone | 5 | 1 | 6 | ||

| iv. | Progressive myoclonic epilepsy | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| v. | Autosomal dominant epilepsy with auditory features | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| vi. | Other familial temporal lobe epilepsies | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| e. | Less specific age relationship | |||||

| i. | Familial focal epilepsy with variable foci | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| ii. | Reflex epilepsies | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 4. | Distinctive constellations | |||||

| i. | Mesial temporal lobe epilepsy with hippocampal sclerosis | 5 | 3 | 8 | ||

| ii. | Rasmussen syndrome | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| iii. | Gelastic seizures with hypothalamic hamartoma | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| iv. | Hemiconvulsion-hemiplegia-epilepsy | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

Approximately half of children had an unknown etiology for their epilepsy, and of the remainder, 79 (22%) were genetic and 100 (28%) were structural/metabolic. Of this latter group, all but 2 cases had a structural etiologies (50 – prior brain injury/perinatal injury, 18-cortical dysplasia, 7-mesial temporal sclerosis, 6-tuberous sclerosis, 6-vascular malformations, 4-dual pathology: mesial temporal sclerosis plus cortical dysplasia, 3-low grade tumor, 1-aquaductal stenosis with hydrocephalus, 1-hypothalamic hamartoma, 1-cortical dysplasia and congenital cytomegalovirus, 1-calcified granuloma). One child had both a genetic and structural etiology (Crouzon syndrome with bifrontal encephalomalacia). Amongst generalized/bilateral onset seizures, etiology was most commonly genetic (79%) with structural/metabolic (6%) and unknown causes (15%) being much less frequent. Amongst focal onset seizures, etiology was most commonly unknown (61%), followed by structural/metabolic (36%). Genetic etiologies were rare causes of focal onset seizures (3%). Of all cases of epilepsy of unknown cause, only 33/179 (18%) met criteria for a specific epileptic syndrome (26 benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes, 2 Panayiotopoulos syndrome, 2 West syndrome, 1 benign infantile epilepsy, 1 Epileptic encephalopathy with CSWS, 1 Lennox-Gastaut syndrome).

Age at onset was significantly correlated with etiology. A structural/metabolic etiology was significantly more likely in children with seizure onset before 12 months of age (27/50, 54%) than those with onset between 12–156 months (64/254, 25%) or after 156 months (8/55, 15%) (p<0.001). Conversely, a genetic etiology was much more likely with older age at onset [21/55 (38%) with onset after 156 months, 51/254 (20%) with onset from 12–156 months, and, 8/50 (16%) with onset before 12 months, p<0.007)]. An unknown etiology was least common in those with onset before 12 months (15/50, 30%) compared to those with onset from 12–156 months (139/254, 55%) or greater than 156 months (26/55, 47%) (p<0.006). Sex was not correlated with etiology.

A specific epilepsy syndrome could be defined at initial diagnosis in 99/359 (28%) children, and at final follow-up in 105/359 (29%). Initial syndrome diagnoses changed over time in only three children, two of whom evolved from Childhood Absence Epilepsy to Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy, and one of whom evolved from Panayiotopoulos Syndrome to Benign Epilepsy with Centrotemporal Spikes. Six children developed a definite epileptic syndrome over follow-up, five of whom developed West syndrome after initial presentation with either focal (N=5) or generalized seizures (N=1), and one of whom developed Benign Epilepsy with Centrotemporal Spikes, after initially presenting with atonic seizures. The ability to identify epilepsy syndrome did not depend on age at onset (p=0.59) but did tend to be more likely in girls (53/163, 33%) than boys (46/196, 23%) (p=0.07).

3.1.2. Incidence of New-Onset Epilepsy

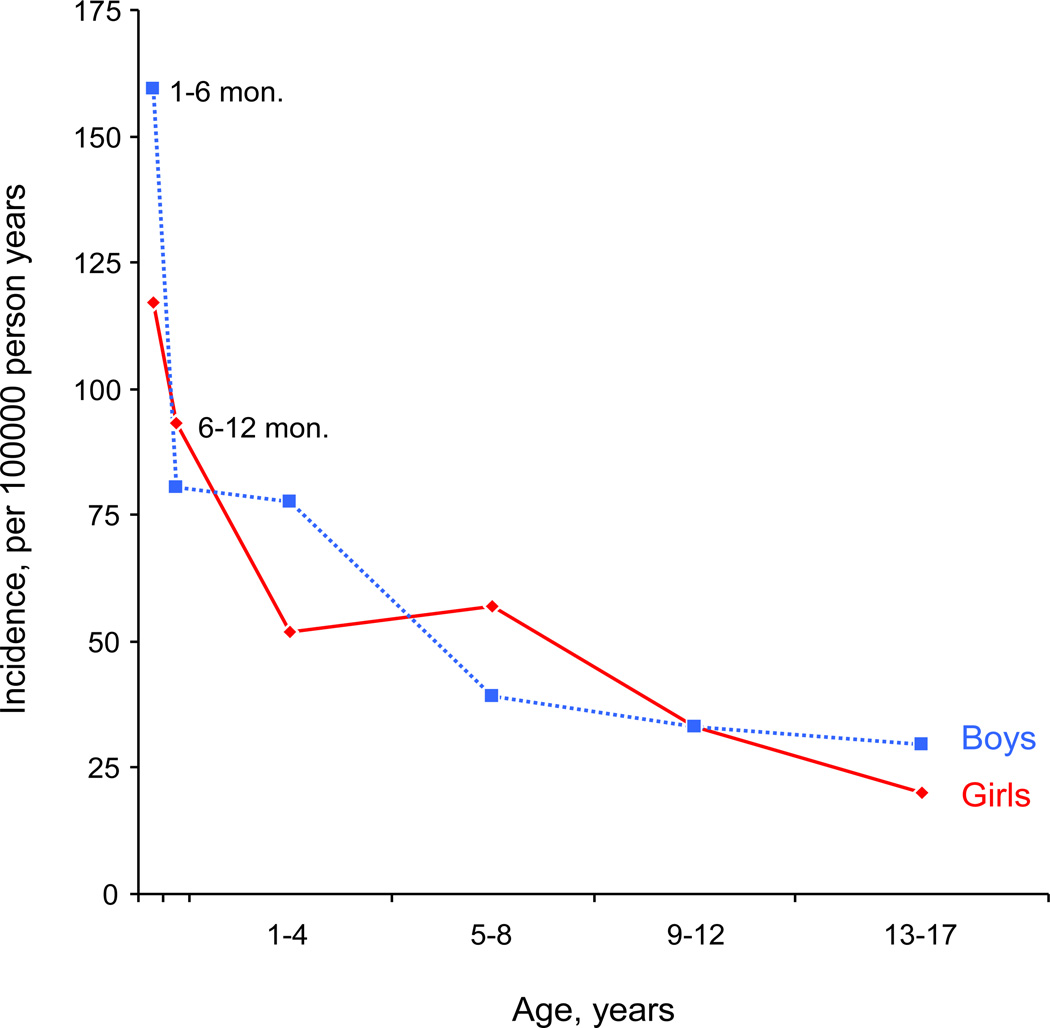

The overall adjusted incidence rate of new-onset epilepsy in children aged one month through age 17 years was 44.5 cases per 100,000 persons per year (Table 2). The rate in boys was slightly higher (46.9 cases per 100,000) than in girls (42.1 cases per 100,000). Incidence rates were higher in the first year of life (particularly between months 1 to 6), and gradually diminished with age (Figure 1). Incidence rates separate by mode of onset and etiology are also reported in Table 2.

Figure 1. Incidence rates separate for boys and girls across age.

Incidence rates for the first year of life are separated into two pieces (1–6 months and 6–12 months). This separation was possible by utilizing the complete enumeration of the Olmsted County population. The incidence rates for 1–6 months were 159.6 for boys, and 117.2 for girls, and 138.8 overall cases per 100,000 persons per year‥ Similarly, the rates for 6–12 months were 80.6 for boys, 93.3 for girls, and 86.8 overall cases per 100,000 persons per year. For comparability with other studies and to allow for age- and sex- adjustment to the U.S. population, the incidence rates for the complete first year of life are reported as one age category in Table 3.

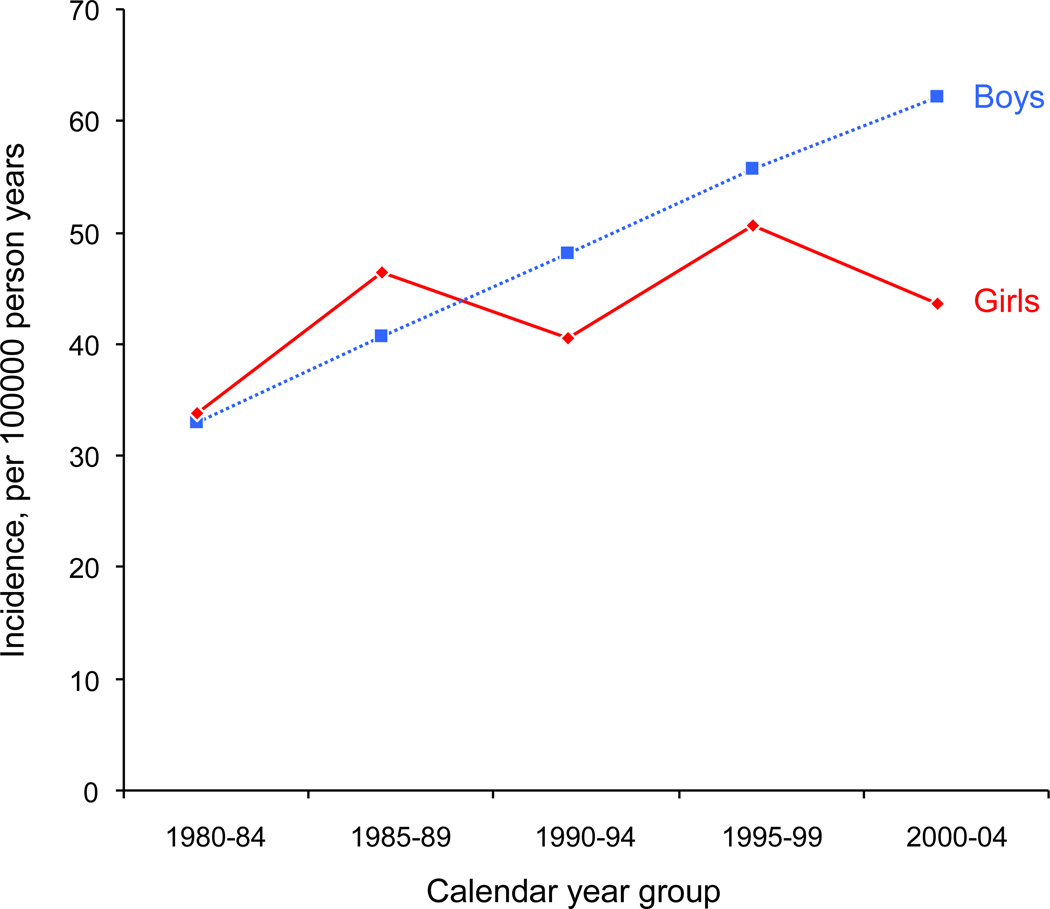

While the incident rates remained relatively stable in girls during the 25-year study period (Poisson rate regression trend over calendar year, p = 0.49), there was a significant increase in incidence rates in boys (Poisson rate regression, p = 0.007; see Table 4 and Figure 2). More patients with first seizures without risk factors suggestive of higher recurrence rate were commenced on prophylactic antiepileptic drugs in the earlier part of the study period. In the 1980s, we found that 5 children were treated after a single seizure without significant risk factors for recurrence. As such, these cases were not defined as incident epilepsy cases in our study. We noted that of the 5 children, 4 were boys. Therefore, we performed additional Poisson rate-regression models adding these 4 boys and 1 girl to the incident case pool. However, the increasing trend in incidence rates across calendar year in boys remained striking (p = 0.02) – no trend was found for girls (p = 0.58). Another factor explaining some of the trend of incidence in boys over calendar year could be that the proportion of epilepsy cases who were graduates from NICU increased over time. Specifically, incident boy cases from 1980–84 were 17.4% NICU graduates, whereas for years 1990–94 this percent was 30.8% and for 2000–04 was 29.1%. However, the trend of increasing proportion of NICU graduates was not significant across the five calendar year periods (p = 0.25). For girls, the proportion of NICU graduates among the cases was relatively constant over time ranging from 16.1% in 1990–94 to 25.0% for 1985–89. Again, the trend was not significant across the five calendar year periods (p = 0.92). In Poisson rate-regression models adjusting for the proportion of cases who were NICU graduates, incidence rates in boys still exhibited an increasing trend across calendar year (p = 0.02) whereas rates in girls did not exhibit a trend (p = 0.49).

Table 4.

Incidence rates per 100,000 persons per year separate for calendar year periods.

| Calendar year group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Description | 1980–84 | 1985–89 | 1990–94 | 1995–99 | 2000–04 | All years |

| All epilepsies | ||||||

| Boys | 32.9 (23) | 40.7 (30) | 48.2 (39) | 55.7 (48) | 62.2 (56) | 48.9 (196) |

| Girls | 33.9 (22) | 46.5 (32) | 40.6 (31) | 50.6 (41) | 43.6 (37) | 43.3 (163) |

| Both | 33.4 (45) | 43.5 (62) | 44.5 (70) | 53.3 (89) | 53.1 (93) | 46.2 (359) |

| Adjusted to the U.S. year 2000 population† | ||||||

| Boys | 32.1 | 39.3 | 45.3 | 54.9 | 59.9 | 46.9 |

| Girls | 32.4 | 43.3 | 39.7 | 49.7 | 43.8 | 42.1 |

| Both | 32.3 | 41.2 | 42.6 | 52.4 | 52.1 | 44.5 |

| Person-years denominators | ||||||

| Boys | 69,915 | 73,740 | 80,947 | 86,161 | 90,102 | 400,865 |

| Girls | 64,992 | 68,876 | 76,375 | 80,972 | 84,895 | 376,110 |

| Both | 134,907 | 142,616 | 157,322 | 167,133 | 174,997 | 776,975 |

Numbers in parentheses indicate the actual number of cases. The rates are calculated by dividing the number of cases by the denominators specified at the bottom of the table and then multiplying by 100,000.

Rates are age- and sex-standardized to the U.S. population from the year 2000 Census (www.census.gov).

Figure 2. Incidence rates separate for boys and girls across calendar year groups.

Observed incidence rates in our study are shown for five calendar year periods. While the incident rates remained relatively stable in girls during the 25-year study period (Poisson rate regression trend over calendar year, p = 0.49), the incidence rates in boys exhibited an increase during the study period (Poisson rate regression, p = 0.007).

4. 1 DISCUSSION

The incidence rate of new-onset epilepsy in our cohort, age- and sex- standardized to the year 2000 U.S. population was 44.5 cases per 100,000 persons per year. This rate is consistent with incidence of epilepsy rates of 33.3 to 82 cases per 100,000 reported in other population-based studies (Adelow et al., 2009, Blom et al., 1978, Camfield et al., 1996, Cavazzuti 1980, Christensen et al., 2007, Doose and Sitepu, 1983, Freitag et al., 2001, Hauser et al., 1993, Larsson and Eeg-Olofsson, 2006, Olafsson et al., 2005). The variation in rates among these studies may be explained by a number of features. Firstly, epilepsy is most common in younger children and decreases in the teen years. Hence, pediatric studies with younger age limits (Freitag et al., 2001) would be expected to have overall higher rates compared to our study, which included children up until their eighteenth birthday. Secondly, epilepsy is defined as “a disorder of the brain characterized by an enduring predisposition to generate epileptic seizures” (Fisher et al., 2005). However, it is often operationally defined as “two or more unprovoked seizures,” as only 40–50% of children having a first seizure will develop a recurrence (Berg and Shinnar, 1991, Hirtz et al., 2003). Despite this, patients are often commenced on antiepileptic medication following their first seizure and inclusion of all patients treated after their first seizure will result in a higher incidence. Conversely, treatment is known to significantly reduce the risk of having a second seizure (Camfield et al., 2002, Leone et al., 2006, Marson et al., 2005). Hence, failure to include individuals treated after their first seizure will result in a lower incidence rate. In our cohort, we included children who were treated with antiepileptic drugs after their first seizure and who then remained seizure-free only if they had features in their history that placed them at high risk of recurrence, including an abnormal neurodevelopmental examination, focal abnormality on brain imaging, initial presentation in status epilepticus or identification of EEG findings suggestive of a higher rate of recurrence (epileptiform discharge, intermittent rhythmic focal delta activity). Thirdly, the neonatal period is a particularly vulnerable time for seizure onset, and inclusion of neonates may result in higher incidence rates. We included subjects with neonatal seizures only if they had recurrent seizures after one month of age.

Similar to other studies, we found the incidence to be markedly higher in the first year of life, and specifically between the first and sixth months (Figure 1). Structural/metabolic etiologies were significantly more likely to present at this age than in older individuals, which likely explains much of the higher incidence. The incidence of epilepsy was also higher in boys than girls across all age groups except in the 5–8 year age range, similar to some (Hauser et al., 1993) but not all (Freitag et al., 2001, Olafsson et al., 2005) prior population-based incidence studies. Possible explanations for this sex difference may include rare X-linked conditions, or higher rates of prior brain injury or perinatal brain injury in males.

The incidence rate of epilepsy in our population remained consistent during the study period in girls, but showed an increased rate over time in boys. The reason for this increased incidence rate over the 25-year study period is not clear however a recent study at our center showed an increased lifetime risk of epilepsy in all ages between 1960 and 1979 (Hesdorffer et al., 2011). In the earlier years of our cohort, there was a greater tendency to initiate treatment after a first unprovoked seizure, even in the absence of other factors which suggest a higher recurrence risk. However, including all patients treated with prophylactic antiepileptic medication after their first seizure did not negate this increased incidence over time. Similarly, the increased rate could not be explained by higher rates of perinatal problems or brain injury over time.

The most common mode of onset in our cohort was focal, accounting for more than two thirds of cases. This finding is similar to prior studies, which noted that 58 to 69% of new onset epilepsy was focal (Freitag et al., 2001, Olafsson et al., 2005, Zarrelli et al., 1999). Nearly half of these cases (49%) were of unknown etiology and did not meet criteria for a specific epilepsy syndrome. Neuroimaging had been obtained in 94% of these cases (69% had an MRI and 25% had a head CT alone) which did not elicit an underlying symptomatic etiology.

Few studies have evaluated how commonly a specific epilepsy syndrome can be defined in new-onset epilepsy, with rates of 10 to 18% in studies including all age ranges (Olafsson et al., 2005, Zarrelli et al., 1999) and 47% in a small study focusing on children younger than 15 years (Freitag et al., 2001). However, in a large prevalence cohort of children with epilepsy, a specific syndrome was identified in only 12% of cases (Akiyama et al., 2006). Using the most recent ILAE Classification, we were able to identify a specific syndrome in 28% of children, based on their initial presentation. The ability to define a specific syndrome is more common in children than adults, and was likely facilitated in our study by availability of clinical data documenting the course of epilepsy over time and by ready access to neurophysiological, neuroimaging and laboratory data. Identification of an epilepsy syndrome provides much clearer information regarding the likelihood of seizure control, remission, and possible associated cognitive effects. The ILAE Classification committee has also defined specific constellations. However, we found these to be rare in our population-based pediatric cohort, with only 9 children (2.5%) meeting the definition for a specific constellation.

Our study is the first to classify a population-based cohort of children using the most recently proposed classification system. We found this system had high inter-rater reliability, as initial disagreement was present between epileptologists in only 4.2% of cases. Accurate classification of epilepsy in large, population-based, incidence cohorts allows improved understanding of the major etiologic patterns, identification of potentially preventable causes and assists in planning for resource allocation. For the individual patient, classification should improve understanding of long-term prognosis for both epilepsy and associated co-morbidities. The new classification system improves classification of mode of onset, by using the term “bilateral” in addition to “generalized”, and by considering “spasms” as a separate entity. Furthermore, there is a specific “genetic” category for etiology, given the significant genetic advances in epilepsy. Finally, the concept of distinctive “constellations” will improve classification of potentially, surgically remediable syndromes.

However, we still have much to learn about epilepsy in children. Almost half of children fall in the “unknown” category for etiology. While a small proportion of this group will meet criteria for a known epilepsy syndrome, our results show that 41% of all childhood epilepsy is of “unknown” cause with no clear syndrome identified. The prognosis for such patients is unclear. While more advanced imaging may ultimately show lesions or malformations of cortical development in a proportion of these cases, further work is needed to define more specific etiologies for this group.

Table 3.

Incidence rates per 100,000 persons per year*

| Age group, y | Adjusted | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Description | First year | 1–4 y | 5–8 y | 9–12 y | 13–17 y | All ages | Rate† |

| All epilepsies | |||||||

| Boys | 107.9 (27) | 77.7 (75) | 39.1 (35) | 33.1 (28) | 29.5 (31) | 48.9 (196) | 46.9 |

| Girls | 96.7 (23) | 52.0 (47) | 56.8 (47) | 33.0 (26) | 19.9 (20) | 43.3 (163) | 42.1 |

| Both | 102.4 (50) | 65.3 (122) | 47.6 (82) | 33.0 (54) | 24.8 (51) | 46.2 (359) | 44.5 |

| Mode of onset ‡ | |||||||

| Generalized | 14.3 (7) | 13.9 (26) | 11.6 (20) | 8.6 (14) | 9.2 (19) | 11.1 (86) | 10.9 |

| Focal | 63.5 (31) | 47.1 (88) | 36.0 (62) | 23.2 (38) | 13.1 (27) | 31.7 (246) | 30.5 |

| Spasms | 18.4 (9) | 0.5 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.3 (10) | 1.1 |

| Unknown | 6.1 (3) | 3.7 (7) | 1.2 (2) | 1.2 (2) | 2.4 (5) | 2.4 (19) | 2.3 |

| Etiology ‡ | |||||||

| Genetic | 16.4 (8) | 9.6 (18) | 11.0 (19) | 9.2 (15) | 9.7 (20) | 10.2 (79) | 10.1 |

| Structural/metabolic | 55.3 (27) | 17.1 (32) | 11.6 (20) | 8.6 (14) | 3.9 (8) | 13.1 (102) | 12.3 |

| Unknown | 30.7 (15) | 38.5 (72) | 25.6 (44) | 15.3 (25) | 11.2 (23) | 23 (179) | 22.2 |

Numbers in parentheses indicate the actual number of cases. The rates are calculated by dividing the number of cases by the denominators specified at the bottom of the table and then multiplying by 100,000.

Rates are age- and sex-standardized to the U.S. population from the year 2000 Census (www.census.gov).

The two children with both focal and generalized mode of onset were included in both categories. The one child with both genetic and structural etiology was included in both categories. See Table 2 for details.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by a CR20 Research award from the Mayo Foundation, and made possible by the Rochester Epidemiology Project (R01 Grant # R01-AG034676 (Dr. WA Rocca PI).

We confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

None of the authors has any conflict of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Elaine C. Wirrell, Professor, Epilepsy and Child and Adolescent Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester MN.

Brandon R. Grossardt, Statistician, Health Sciences Research, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

Lily C.-L. Wong-Kisiel, Fellow, Pediatric Epilepsy, Mayo Clinic, Rochester MN.

Katherine C. Nickels, Assistant Professor, Epilepsy and Child and Adolescent Neurology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester MN.

References

- Adelow C, Andell E, Amark P, Andersson T, Hellebro E, Ahlbom A, Tomson T. Newly diagnosed single unprovoked seizures and epilepsy in Stockholm, Sweden: First report from the Stockholm Incidence Registry of Epilepsy (SIRE) Epilepsia. 2009;50:1094–1101. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama T, Kobayashi K, Ogino T, Yoshinaga H, Oka E, Oka M, Ito M, Ohtsuka Y. A population-based survey of childhood epilepsy in Okayama Prefecture, Japan: reclassification by a newly proposed diagnostic scheme of epilepsies in 2001. Epilepsy Res. 2006;70 Suppl 1:S34–S40. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2005.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beghi E, Carpio A, Forsgren L, Hesdorffer DC, Malmgren K, Sander JW, Tomson T, Hauser WA. Recommendation for a definition of acute symptomatic seizure. Epilepsia. 2010;51:671–675. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg AT, Berkovic SF, Brodie MJ, Buchhalter J, Cross JH, van Emde Boas W, Engel J, French J, Glauser TA, Mathern GW, Moshe SL, Nordli D, Plouin P, Scheffer IE. Revised terminology and concepts for organization of seizures and epilepsies: report of the ILAE Commission on Classification and Terminology, 2005–2009. Epilepsia. 2010;51:676–685. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg AT, Shinnar S. The risk of seizure recurrence following a first unprovoked seizure: a quantitative review. Neurology. 1991;41:965–972. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.7.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom S, Heijbel J, Bergfors PG. Incidence of epilepsy in children: a follow-up study three years after the first seizure. Epilepsia. 1978;19:343–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1978.tb04500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camfield CS, Camfield PR, Gordon K, Wirrell E, Dooley JM. Incidence of epilepsy in childhood and adolescence: a population-based study in Nova Scotia from 1977 to 1985. Epilepsia. 1996;37:19–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1996.tb00506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camfield P, Camfield C. Epilepsy can be diagnosed when the first two seizures occur on the same day. Epilepsia. 2000;41:1230–1233. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb00331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camfield P, Camfield C, Smith S, Dooley J, Smith E. Long-term outcome is unchanged by antiepileptic drug treatment after a first seizure: a 15-year follow-up from a randomized trial in childhood. Epilepsia. 2002;43:662–663. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.03102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavazzuti GB. Epidemiology of different types of epilepsy in school age children of Modena, Italy. Epilepsia. 1980;21:57–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1980.tb04044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen J, Vestergaard M, Pedersen MG, Pedersen CB, Olsen J, Sidenius P. Incidence and prevalence of epilepsy in Denmark. Epilepsy Res. 2007;76:60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doose H, Sitepu B. Childhood epilepsy in a German city. Neuropediatrics. 1983;14:220–224. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1059582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher RS, van Emde Boas W, Blume W, Elger C, Genton P, Lee P, Engel J., Jr Epileptic seizures and epilepsy: definitions proposed by the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) and the International Bureau for Epilepsy (IBE) Epilepsia. 2005;46:470–472. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2005.66104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitag CM, May TW, Pfafflin M, Konig S, Rating D. Incidence of epilepsies and epileptic syndromes in children and adolescents: a population-based prospective study in Germany. Epilepsia. 2001;42:979–985. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.042008979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser WA, Annegers JF, Kurland LT. Incidence of epilepsy and unprovoked seizures in Rochester, Minnesota: 1935–1984. Epilepsia. 1993;34:453–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1993.tb02586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesdorffer DC, Logroscino G, Benn EKT, Katri N, Cascino G, Hauser WA. Estimating risk for developing epilepsy. Neurology. 2011;76:23–27. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318204a36a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirtz D, Berg A, Bettis D, Camfield C, Camfield P, Crumrine P, Gaillard WD, Schneider S, Shinnar S. Practice parameter: treatment of the child with a first unprovoked seizure: Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. Neurology. 2003;60:166–175. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000033622.27961.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson K, Eeg-Olofsson O. A population based study of epilepsy in children from a Swedish county. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2006;10:107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone MA, Solari A, Beghi E. Treatment of the first tonic-clonic seizure does not affect long-term remission of epilepsy. Neurology. 2006;67:2227–2229. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000249309.80510.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loiseau J, Loiseau P, Guyot M, Duche B, Dartigues JF, Aublet B. Survey of seizure disorders in the French southwest. I. Incidence of epileptic syndromes. Epilepsia. 1990;31:391–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1990.tb05493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marson A, Jacoby A, Johnson A, Kim L, Gamble C, Chadwick D. Immediate versus deferred antiepileptic drug treatment for early epilepsy and single seizures: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365:2007–2013. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66694-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melton LJ., 3rd History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71:266–274. doi: 10.4065/71.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olafsson E, Ludvigsson P, Gudmundsson G, Hesdorffer D, Kjartansson O, Hauser WA. Incidence of unprovoked seizures and epilepsy in Iceland and assessment of the epilepsy syndrome classification: a prospective study. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4:627–634. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70172-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher RS, van Emde Boas W, Blume W, Elger C, Genton P, Lee P, Engel J., Jr Epileptic seizures and epilepsy: definitions proposed by the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) and the International Bureau for Epilepsy (IBE) Epilepsia. 2005;46:470–472. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2005.66104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarrelli MM, Beghi E, Rocca WA, Hauser WA. Incidence of epileptic syndromes in Rochester, Minnesota: 1980–1984. Epilepsia. 1999;40:1708–1714. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1999.tb01587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]