Abstract

Metamorphically competent larvae of the marine tubeworm Hydroides elegans can be induced to metamorphose by biofilms of the bacterium Pseudoalteromonas luteoviolacea strain HI1. Mutational analysis was used to identify four genes that are necessary for metamorphic induction and encode functions that may be related to cell adhesion and bacterial secretion systems. No major differences in biofilm characteristics, such as biofilm cell density, thickness, biomass and EPS biomass, were seen between biofilms composed of P. luteoviolacea (HI1) and mutants lacking one of the four genes. The analysis indicates that factors other than those relating to physical characteristics of biofilms are critical to the inductive capacity of P. luteoviolacea (HI1), and that essential inductive molecular components are missing in the non-inductive deletion-mutant strains.

Introduction

Communities of benthic marine animals are established and maintained by recruitment of larvae of their member species, and larvae of most marine invertebrates recognize appropriate sites for settlement and metamorphosis by chemical cues from conspecific individuals or other associated species1. Bacteria in marine biofilms play an important role in the recruitment of many marine invertebrate species by producing cues to settlement for invertebrate larvae2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. When invertebrate larvae select a surface on which to settle, they can differentiate between characteristics of a biofilm such as age10,11, bacterial density12,13, biochemical signals14,15,16,17,18,19,20, and the overall community composition7.

Hadfield and Paul1 reviewed a large literature on the topic of "settlement in response to biofilms," citing data on the role of biofilms in settlement of larvae from 10 phyla, but finding virtually no identification of inducing substances. Subsequently, interest in the role of biofilms in recruitment of benthic marine invertebrates has been intense; a recent review of literature on the topic of marine biofilms yielded more than 1,000 references in the last 10 years. Despite this interest, there have been very few molecular components of biofilms identified as inducers of larval settlement. Studies implicating soluble substances from microbial components (e.g., amino acids, acyl homoserine lactones) of biofilms have mostly been discounted8. Two studies have identified probable bacterial products as settlement inducers for diverse invertebrates: histamine (either from an alga or bacteria on it) induces settlement and metamorphosis in larvae of the sea urchin Holopneustes purpurascens21; and tetrabromopyrrole secreted by strains of Pseudoalteromonas isolated from the surfaces of coralline algae induces metamorphosis, but not settlement, in planula larvae of the coral Acropora millepora22. Related literature on possible bacterial sources of settlement inducers was recently reviewed by Hadfield8. To our knowledge, there have been no previous studies on the molecular genetic basis of bacterial induction of larval settlement.

Hydroides elegans is a common fouling polychaete in tropical and subtropical seas23. In the laboratory, the planktotrophic larvae of H. elegans become competent to settle and metamorphose in approximately 5 days24. Competent larvae are induced to settle and rapidly metamorphose by the presence of a well-developed biofilm5. Although the degree of settlement induced by some monospecific strains is rarely as great as with natural, multispecies films5,25, one Gram-negative bacterial strain, Pseudoalteromonas luteoviolacea (HI1), induces metamorphosis of larvae of H. elegans as strongly as natural, multispecies biofilms12. Huang and Hadfield demonstrated that the inductive capacity of bacterial species is restricted to the biofilm phase and, while characteristic of only a fraction of biofilm bacterial species, is not phylogenetically constrained12. Further investigation is required to elucidate the molecular and cellular differences underlying the larval settlement-inducing capacity of bacteria that occur in biofilms.

Although the relationship between bacteria and induction of settlement in H. elegans has been the subject of many investigations8, the particular molecular cues and molecular mechanisms by which P. luteoviolacea (HI1) induces metamorphosis of H. elegans remain unknown. This study uses a classical genetic approach to identify genes from P. luteoviolacea (HI1) whose products are necessary to induce settlement and metamorphosis in those larvae. Establishing genetic markers that can be used to evaluate the inductive capacity of a wide spectrum of bacteria is a crucial step for understanding the role of biofilms in larval settlement and metamorphosis for many species that in turn may aid antifouling strategies.

Results

Screening for mutants of P. luteoviolacea (HI1) incapable of inducing larval settlement

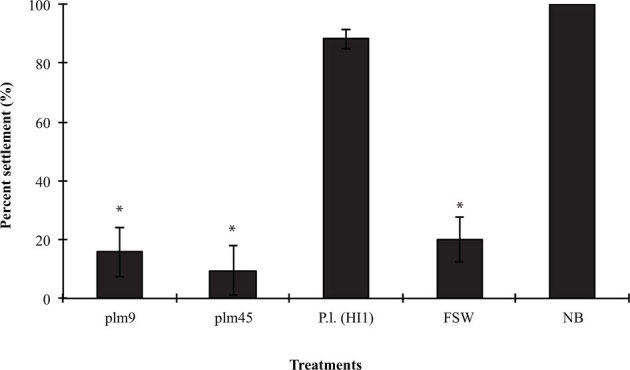

Approximately 500 kanamycin-resistant transposon-Tn10 mutants of P. luteoviolacea (HI1) were screened for their capacity to induce settlement and metamorphosis of competent larvae of H. elegans. Two mutants that produced non-inductive biofilms, designated Plm9 and Plm45, were identified for further investigation (Fig. 1). When larvae were exposed to biofilms made by either of these two transposon mutants, their behavior was no different from that of larvae in autoclaved FSW and clean dishes (i.e., negative controls). The larvae continued to swim actively during the entire 24hr period. Larvae that were exposed to a biofilm of wild-type P. luteoviolacea (HI1) immediately slowed swimming and started to crawl along the bottom of the dish. After 24hours, 85100% of the larvae settled and metamorphosed when they were exposed to a biofilm of wild-type P. luteoviolacea (HI1) or a natural biofilm. However, fewer than 20% of larvae settled and metamorphosed when presented with biofilms made of either of the transposon mutants, which was significantly less than the positive control (p<0.0001) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Settlement (%) of H. elegans on biofilms made by transposon mutants Plm9, Plm45, and wild type (P.l.) of P. luteoviolacea (HI1).

Dishes coated by natural biofilm (NB) served as positive controls; untreated Petri dishes filled with autoclaved filtered seawater (FSW) were negative controls. Bars represent mean percentages of larvae that settled in 24h +/ SD (n = 5). * denotes significant differences compared with the positive control (Kruskal-Wallis test, p<0.0001).

Identification of genes disrupted by the transposon

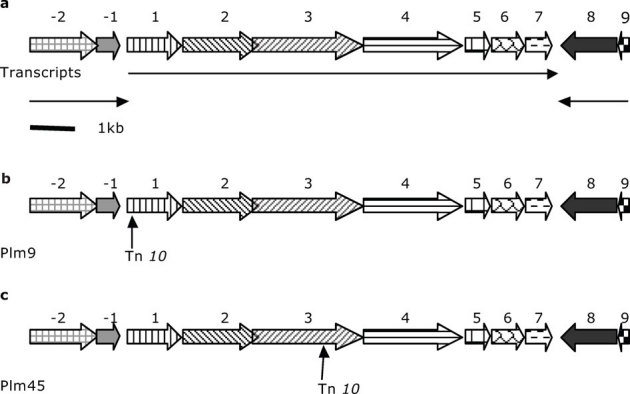

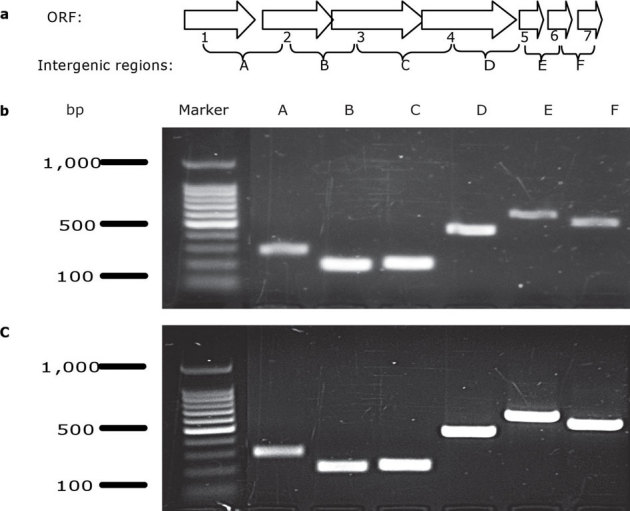

DNA sequencing of PCR products representing the regions flanking the Tn10 inserts in mutants Plm9 and Plm45 yielded a 21,517bp nucleotide region of DNA comprised of 11 open reading frames (Fig. 2). The transposon in mutant Plm9 was inserted in open-reading frame 1 (ORF1) and in ORF3 for mutant Plm45. These two ORFs appear to be part of a seven-gene operon. The seven genes are in the same orientation, and intergenic regions range in length from 3 to +100 nucleotides. Moreover, bands of appropriate sizes were obtained in reverse-transcription PCR for sets of primers flanking the individual intergenic regions of adjacent genes in the putative operon (Fig. 3) (No bands were present in all negative controls). Promoter-prediction analysis revealed a potential transcription start site around 22bp upstream of the ORF1 start codon (sequence of 10 element AGGTATGCT and sequence of 35 element TTGACC). Two potential transcription-factor (cAMP receptor protein and CynR, a LysR family member) binding sites were also predicted at 58bp and 12bp upstream of the start codon. ORF8 is oriented in the opposite direction of ORFs 1 to 7, indicating that ORF8 is part of a different transcript. This analysis suggests that ORFs 1 to 7 are in the same operon (Fig. 2). The nucleotide-sequence data for these 7 ORFs of P. luteoviolacea (HI1) were deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers JQ217134, JQ217135, JQ217136, JQ217137, JQ217138, JQ217139, JQ217140.

Figure 2. Predicted operon in P. luteoviolacea (HI1) showing sites of transposon insertions:

a, schematic diagram of putative transcription units with numbers 17 indicating putative open reading frames (ORFs) within the operon, 1 and 2 ORFs upstream of the operon; and No.8 and No.9 ORFs downstream from the operon; b, transposon insertion site in transposon mutant Plm9; c, transposon insertion site in transposon mutant Plm45. The scale bar represents approximately 1Kb. Horizontal arrows represent the direction of transcription and the approximate lengths of transcript units.

Figure 3. Intergenic regions of adjacent genes in the putative operon were checked by Rt-PCR.

a, diagrammatic representation of the operon with open reading frames 1 7 and their intersections indicated with A F; b, amplicons with primers connecting intersections of the neighboring ORFs on cDNA; and c, amplicons with primers connecting intersections of the neighboring ORFs on chromosomal DNA positive control. No bands appeared in negative controls which employed cDNA amplified without reverse transcriptase in reactions.

Four ORFs required for inductive capacity

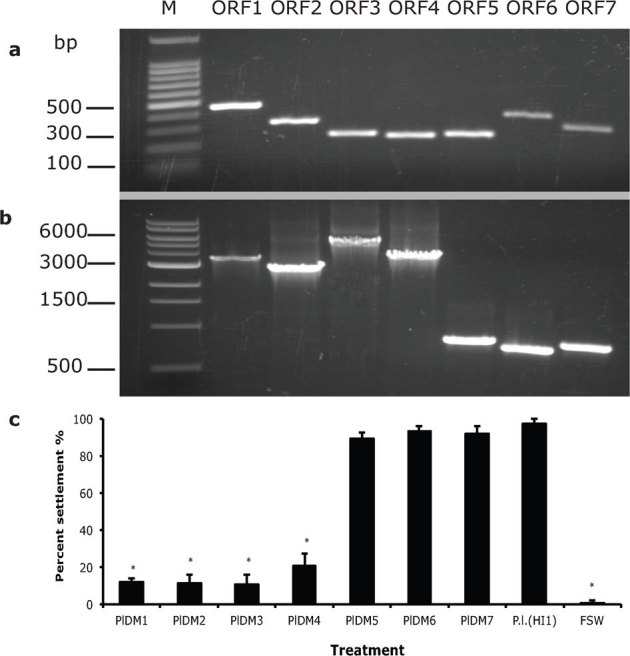

Deletion mutants were generated to confirm that the genes disrupted by transposon insertion were responsible for the lack of induction of metamorphosis of H. elegans by each mutant strain and to identify additional genes in the operon that may be necessary for the inductive capacity of the bacterium. Seven unmarked, in-frame deletion mutants corresponding to each of the seven ORFs were generated by allelic replacement. Depending on which open reading frame was deleted, the deletion mutants were designated PlDM1 through PlDM7. For each of the deletion-mutant strains, most of the targeted ORF was removed and the remaining 5 and 3 ends (51bp) were fused in frame to avoid polar effects of the mutations. Deletions were confirmed by comparing the sizes of PCR products corresponding to each of the ORFs from wild type of P. luteoviolacea (HI1) and the deletion mutants PlDM1 through PlDM7 (Fig. 4a and 4b).

Figure 4. Deletion mutants of P. luteoviolacea (HI1) and analysis of their inductive capacity.

a, amplicons with primers complementary to flanking regions of each ORF from deletion mutants PlDM1 to PlDM7 (M: DNA Marker); b, amplicons with the same primer sets from wild type P. luteoviolacea (P.l. (HI1)); c, settlement (%) of H. elegans on biofilms made from deletion mutants PlDM1, PlDM2, PlDM3, PlDM4, PlDM5, PlDM6, PlDM7 and wild type P. luteoviolacea (HI1). Clean Petri dishes filled with FSW were negative controls. Bars represent mean percentages of larvae that settled in 24h +/ SD (n = 5). * denotes significant difference compared with P. luteoviolacea (HI1) (Kruskal-Wallis test, p<0.01).

Of the 7 deletion mutants, the first four, PlDM1, PlDM2, PlDM3, and PlDM4, lost the capacity to induce settlement and metamorphosis for larvae of H. elegans (Fig. 4c, p<0.0001); percent settlement in response to PlDM5, PlDM6, and PlDM7 was not significantly different from that of wild-type P. luteoviolacea (HI1) (Fig. 4c, P = 0.06730.1038). Deletion analysis indicated that ORFs 1, 2, 3 and 4 were required for the inductive capacity of P. luteoviolacea (HI1).

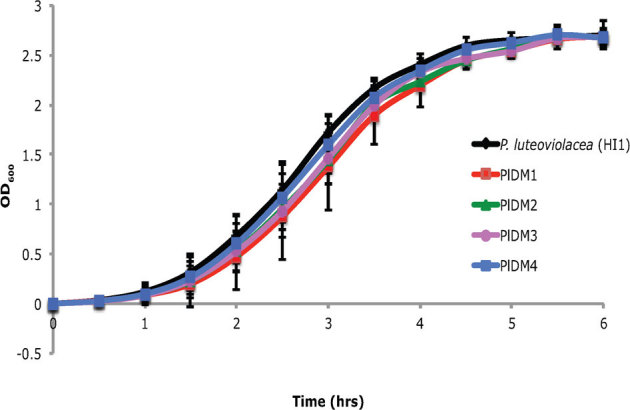

Comparison of the growth rate of wild-type P. luteoviolacea (HI1) and the deletion mutants

Figure 5 depicts the growth curves of wild-type P. luteoviolacea (HI1) and its non-inductive deletion mutants (PlDM1- PlDM4) in liquid SWT medium. Deletion mutants PlDM1- PlDM4 exhibited growth patterns similar to that of wild type P. luteoviolacea (HI1), which indicates the lack of inductive capacity in deletion mutants (PlDM1-PlDM4) was not attributable to simple differences in growth rates.

Figure 5. Growth of wild type of P. luteoviolacea (HI1) and 4 deletion mutants for four open reading frames, PlDM1, PlDM2, PlDM4 and PlDM4.

Y-axis represents optical density of bacterial broth at 600nm.

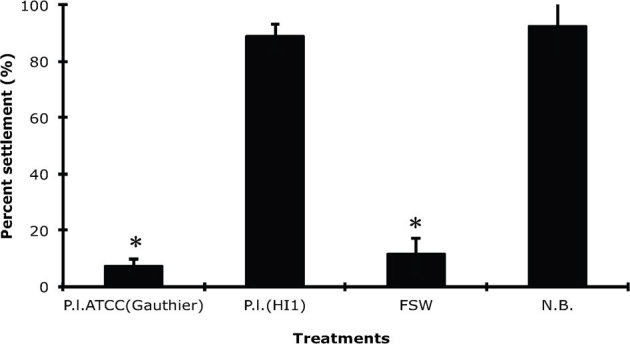

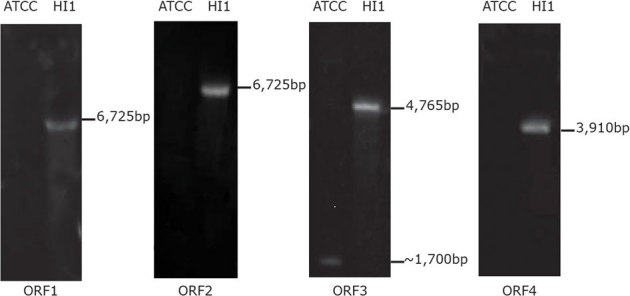

Correlation between inductive capacity and induction genes

The sequences of the 16S rRNA genes from the Hawaiian strain of Pseudoalteromonas luteoviolacea (HI1) and the strain of this bacterium held by the American Type Culture Collection (P. luteoviolacea ATCC334926) are 99.9% identical, suggesting that the two strains are very similar. However, larval settlement and metamorphosis in response to these two strains are significantly different (p = 0.0004). Larval settlement on a biofilm of P. luteoviolacea ATCC334926 was less than 10% and not significantly different from that in a sterile dish filled with autoclaved, filtered seawater (negative control) (p = 1.00) (Fig. 6). Conversely, settlement on both a biofilm of P. luteoviolacea (HI1) and a natural biofilm (N.B.) was above 80%, significantly greater than the negative control (p = 0.0045 and p = 0.0004) (Fig. 6). Probes to each of the four induction genes from strain HI1 were developed and used in Southern blot analysis to determine if there are corresponding genes in P. luteoviolacea ATCC334926 with significant sequence similarity. As seen in figure 7, no bands appeared in digests of the P. luteoviolacea ATCC334926 with probes to ORF1, ORF2 and ORF4, although one light and much smaller fragment for ORF3 was present. This evidence indicates that this area of the genome of P. luteoviolacea ATCC334926 is very different from that of strain HI1, perhaps even missing, which may account for the difference in metamorphic induction capability of the two strains.

Figure 6. Comparison of settlement (%) of larvae of H. elegans on biofilms made by P. luteoviolacea ATCC334926 and P. luteoviolacea (HI1).

A, dishes coated by a natural biofilm (N.B.) were positive controls; untreated Petri dishes filled with autoclaved filtered seawater (FSW) were negative controls. Bars represent mean percent of larvae that settled in 24h +/ SD (n = 5). * denotes significant difference compared with positive control (Kruskal-Wallis test, p<0.01).

Figure 7. Southern blot analysis to determine the presence of inductive genes in P. luteoviolacea ATCC334926.

Probes designed from ORFs 14 were hybridized with genomic DNA of P. luteoviolacea (HI1) and P. luteoviolacea ATCC334926 that had been digested with restriction enzymes and run in parallel lanes on a gel.

Prediction of putative gene functions

Putative protein functions were determined by BLAST analysis of the translated nucleotide sequences of ORFs 1 7 with NCBI's protein data bank; a cut-off e-value of 0.001 was used. Proteins corresponding to both ORFs 1 and 2 contain the conserved domain TIGR02243, which is a large, conserved hypothetical phage-tail-like protein that is similar to components of Type VI secretion systems27,28. ORF2 encodes a multi-domain protein. In addition to the TIGR02243 domain, the protein encoded by ORF 2 belongs to superfamily CL09931, NADB_Rossmann superfamily, which is found in numerous dehydrogenases of metabolic pathways such as glycolysis, and many other redox enzymes29.

ORF3 encodes a putative protein that may function in cell adhesion or aggregation; it has similarity to YadA domain-containing proteins or adhesion-like proteins. YadA domain has been shown to be a major adhesin and is necessary for virulence of some strains of Yersinia30. However, ORF3 does not appear to contain the YadA domain itself. The translated ORF4 sequence lacked recognizable domains and is similar to only hypothetical proteins of unknown function.

Comparison of biofilm characteristics between wild type P. luteoviolacea (HI1) and the deletion mutants

The putative functions of the ORFs shown to be required for induction of morphogenesis suggested that they might be involved in biofilm production. Accordingly, cell density, biofilm thickness, biofilm cell biomass and EPS biomass of biofilms composed of wild type P. luteoviolacea (HI1) were compared with those of the 7 deletion mutants (Table 1). Cell densities in biofilms from mutant strains PlDM3 and PlDM5 (> 18 103 cells mm2) were significantly greater than in the wild type (p = 0.0003 and p = 0.0014), while those from the other deletion mutant strains were not shown to be significantly different from that of the wild type (p = 0.1279 1.00). Mean biofilm thicknesses of the strains were similar, and none of the deletion-mutant strains was significantly different from the wild type P. luteoviolacea (HI1) (p = 0.2703). Mutant strain PlDM3 was the only strain among seven deletion mutants whose total biomass and EPS biomass were significantly greater than those of wild type of P. luteoviolacea (HI1) (p = 0.0082 and p = 0.0097) (Table 1). These results indicate that ORF3 appears to negatively regulate with thickness and density of biofilm.

Table 1. Biofilm characteristics of wild type P. luteoviolacea (HI1) and its deletion mutants.

| Bacterial strains | Biofilm cell density (X103 cellsmm2) | Biofilm thickness (m) | Biofilm cell biomass (m3m2) | EPS biomass (m3m2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. luteoviolacea (HI1) | 1.610.81 | 0.400.36 | 0.170.11 | 0.090.07 |

| PlDM1 | 6.334.13 | 0.390.17 | 0.180.07 | 0.140.06 |

| PlDM2 | 3.623.95 | 0.100.10 | 0.090.05 | 0.050.04 |

| PlDM3 | 27.5518.30* | 0.620.26 | 0.500.18* | 0.330.14* |

| PlDM4 | 5.836.58 | 0.560.28 | 0.250.09 | 0.210.07 |

| PlDM5 | 18.347.79* | 0.450.31 | 0.280.15 | 0.190.11 |

| PlDM6 | 8.116.12 | 0.710.47 | 0.310.13 | 0.250.11 |

| PlDM7 | 7.054.62 | 0.440.30 | 0.200.11 | 0.170.11 |

Comparisons were made between characteristics of wild type P. luteoviolacea (HI1) and its deletion mutants: PlDM1-7. Means of biofilm cell density were compared with a Kruskal-Wallis chi-square test, followed by Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Biofilm thickness, biofilm cell biomass and EPS biomass were compared with a One-Way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons also. Data listed in the table represent mean value SD (n = 35).

*denotes significant difference compared with P. luteoviolacea (HI1) (p<0.01).

Discussion

Ubiquitous components of shallow water marine biofilms, Pseudoalteromonas species have been found to provide cues for larval settlement and metamorphosis for a variety of marine invertebrate species6,8,21,31,32,33. However, the inductive capacity of the bacteria varies both between species of a single genus12 and between strains of single species, such as those of P. luteoviolacea evaluated here (Fig. 6). Variation in inductive capacity between these strains suggests that small genetic changes can result in disparate inductive capacities.

In the present study, two mutant strains, Plm9 (ORF1 disrupted) and Plm45 (ORF3 disrupted), created by random transposon insertion were found to have lost the capacity to induce larval settlement in the tubeworm. Although it was possible that these genes are essential for induction, it was also possible that the insertion of the transposon disrupted the functions of genes downstream from those with the inserted transposon. To examine this possibility, deletion mutants were generated that were non-polar and thus would be less likely to affect transcription and translation of downstream genes. Deletion mutants lacking one of the first four open-reading frames in a single putative operon lost the capacity to induce settlement of H. elegans, and deletion mutants of the remaining three downstream open-reading frames remained inductive (Fig. 4c). The growth curves of deletion-mutant strains for the first 4 open-reading frames and for wild type P. luteoviolacea (HI1) reveal that all these strains reach stationary phase after 4hrs in broth culture (Fig. 5), strongly suggesting that the loss of inductive activity in the deletion mutants is not due simply to differences in either growth stage or density of the bacteria in cultures (our biofilms are made from overnight bacterial broth cultures). This evidence suggests that the products of these genes are required in a more fundamental manner for the settlement process of H. elegans. Significantly, ORF1, ORF2 and ORF4 identified in P. luteoviolacea (HI1) are absent in the non-inductive strain P. luteoviolacea ATCC334926. These results provide strong evidence that the region of the genome identified in the study contains important genes whose products are necessary for inducing the settlement and metamorphosis of H. elegans and perhaps larvae of other invertebrate species. It will be of great interest to learn if products of the same genes are involved in metamorphic induction of an Australian sea urchin whose larvae are known to respond to P. luteoviolacea6 and the coral Pocillopora damicornis33. We have very preliminary data (not shown) suggesting that the mutants of P. luteoviolacea (Plm9 and Plm45) created in the current study fail to induce larval settlement of P. damicornis.

The physical and chemical attributes of bacterial biofilms are known to affect the settlement and metamorphosis of marine invertebrates7,9,10,11,34,35,36. Thus, the biofilm phenotypes of wild type P. luteoviolacea (HI1) and the deletion mutants were compared to examine the possibility that the products of the corresponding genes are involved in the physical structure of the biofilms. However, biofilm characteristics, including cell density, average biofilm thickness, biofilm biomass, and EPS biomass (evaluated from specific carbohydrates) of the 7 deletion mutants were not significantly lower than those of wild type P. luteoviolacea (HI1), indicating that it is not simply the gross physical characteristics of the biofilms that make P. luteoviolacea (HI1) inductive for settlement and morphogenesis of larval H. elegans. Therefore, it is most likely a missing or altered specific molecular component in the biofilm that results in loss of inductive action in the deletion mutants of P. luteoviolacea (HI1).

ORF1 and ORF2 both contain the conserved domain TIGR02243, encoding hypothetical phage-tail or phage-baseplate proteins, which have been found in at least in 6 bacterial genomes. Pell, et al.27 and Leiman, et al.28 reported a remarkable level of structural and presumed functional similarity between phage tail and baseplate proteins and components of type VI secretion systems. Type VI secretion systems mediate contact dependent transfer of effector molecules from the bacterium to the cytoplasm of other prokaryotic or eukaryotic cells37. Interestingly, the N-terminal deduced amino acid sequence of ORF7, which appears to be in the same operon as ORFs 1 and 2, has homology with VgrG proteins from Vibrio mimicus (VM603), a group of proteins proposed to be extracellular appendages in the bacterial type VI secretion system with shared structural features of phage-tail spike proteins38. This suggests that the TIGR02243 domain may be associated with secretion pathways that transport specific molecules into the biofilm matrix or directly into larval cells, and that loss of inductivity in mutants with disrupted or deleted ORFs 1 and 2 might be due to interruption of transport of necessary compounds from the bacterium to the tubeworm. This question will be pursued in our future studies.

In conclusion, this study has identified the first bacterial genes required for induction of settlement and metamorphosis of a marine invertebrate animal. Four of the seven open reading frames in the identified operon were necessary for induction. In addition, sequences corresponding to three of the four ORFs necessary for induction of metamorphosis were not found in the non-inductive strain P. luteoviolacea ATCC334926. However, other bacterial species are known to induce settlement and metamorphosis in H. elegans5,12, and it remains to be learned if their genomes include this same inductive operon. The gene-function analysis of four essential genes suggests that the operon may be involved in the formation of a secretion system or biofilm formation, either of which may be important in inducing larval settlement and metamorphosis in H. elegans. The exact mechanism of induction remains an open and interesting question, but may be difficult to determine. Finally, investigation of the importance of the identified gene cluster in inducing settlement of larvae from many different phyla known to be induced by biofilms will yield very interesting phylogenetic implications.

Methods

Spawning, larval culture and larval settlement bioassay

Specimens of Hydroides elegans were spawned and larvae were cultured as previously described23,25. Wild type and mutant strains of Pseudoalteromonas luteoviolacea were subjected to a larval settlement bioassay as described by Huang and Hadfield12.

Bacterial stains, plasmids, media and growth conditions

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Table 2. The Hawaii strain, P. luteoviolacea (HI1), was previously isolated from a seawater table at Kewalo Marine Laboratory (KML), Honolulu, HI12. A spontaneously occurring streptomycin-resistant mutant of P. luteoviolacea (P. luteoviolacea (HI1, StrR)) was experimentally selected from the Hawaii strain for mutagenesis experiments; a larval settlement assay showed that it maintained the capacity to induce settlement and metamorphosis in larvae of H. elegans. Another strain, P. luteoviolacea ATCC334926, obtained from the American Type Culture Collection, is 99.99% identical with P. luteoviolacea (HI1) in the 16S rDNA gene sequence.

Table 2. Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Bacterial strain | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| CC118 (pir) | (ara-leu) araD lacX74 galE galK phoA20 thi-l rpsE rpoB argE(Am) recAl pir | 48 |

| SM10 (pir) | thi-l thr leu tonA lacY supE recA::RP4-2-Tcr::Mu, Kmr, pir | 48 |

| P. luteoviolacea | ||

| HI1 | Wild-type isolate | 12 |

| ATCC3349 | Isolated from seawater, France, ATCC number: 33492 | 26 |

| HI1, Strr | Spontaneous streptomycin-resistant, mutant of Hawaii strain | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pLOF/Km | Ampr (Tn10-based delivery plasmid, Kmr) | 48 |

| pCVD442 | Apr; Sucroses, 1.2-kb SacB gene inserted into pGP704 at cloning site PstI | 41 |

| pCVD443 | Apr, Kmr, Sucroses, pCVD442 with Kmr gene inserted at SmaI site | This study |

| pDM 1 | Apr, Kmr, Sucroses, pCVD443 with 1.6kb of DNA flanking ORF1 | This study |

| pDM2 | Apr, Kmr, Sucroses, pCVD443 with 1.6kb of DNA flanking ORF2 | This study |

| pDM3 | Apr, Kmr, Sucroses, pCVD443 with 1.6kb of DNA flanking ORF3 | This study |

| pDM4 | Apr, Kmr, Sucroses, pCVD443 with 1.6kb of DNA flanking ORF4 | This study |

| pDM5 | Apr, Kmr, Sucroses, pCVD443 with 1.6kb of DNA flanking ORF5 | This study |

| pDM6 | Apr, Kmr, Sucroses, pCVD443 with 1.6kb of DNA flanking ORF6 | This study |

| pDM7 | Apr, Kmr, Sucroses, pCVD443 with 1.6kb of DNA flanking ORF7 | This study |

All strains of P. luteoviolacea were maintained on agar or in liquid seawater media containing 0.25% tryptone (W/V), 0.15% yeast extract (W/V) and 0.15% glycerol (V/V) (1/2 SWT), at room temperature (25C). Luria-Bertani (LB) medium was routinely used to grow strains of E. coli on agar plates or in liquid culture at 37C. When required, the final concentrations of antibiotics in growth media were as follows: kanamycin, 50g ml1 (for E. coli strains) and 200g ml1 (for P. luteoviolacea strains); ampicillin, 100g ml1; and streptomycin, 200g ml1.

Transposon mutagenesis

Overnight cultures of the donor strain, SM10 pir containing pLOF/Km, and the recipient strain, P. luteoviolacea (HI1, Smr), were washed in LB or SWT liquid media, respectively, to eliminate antibiotics. Plasmids were transferred from the E. coli strain into P. luteoviolacea by conjugation as described by Egan, et al.39. Colonies that arose were screened in larval settlement assays.

DNA manipulation and sequencing

The primers and DNA oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Table 3. Genomic DNA of each candidate mutant was extracted with a MoBio UltracleanTM Microbial DNA kit following the manufacturer's instructions. For transposon mutants, the region of DNA flanking the transposon insertion site was isolated by successive rounds of panhandle PCR40. Two primers, Tn10D and Tn10C, that were complementary to the 5 and 3 ends of the mini-Tn10 transposon39, were used individually in .PCR reactions with the Adaptor 1 primer in the first round of PCR. Subsequent rounds of panhandle PCR for genome walking were conducted using genome-specific primers, which were designed in the transposon flanking regions elucidated with earlier rounds of PCR, and Adaptor primer 1 as primer pairs to obtain the upstream and downstream regions. The steps above were repeated until the sequence of the entire region was obtained. PCR products were examined on 1% agarose ethidium bromide gels and purified with a MinElute Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Purified PCR products were sent to the Advanced Studies in Genomics, Proteomics and Bioinformatics (ASGPB) facility at University of Hawaii for sequencing.

Table 3. Sequences of oligonucleotides used in genome walking.

| Adaptor 1 | 5-CTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCTCGAGCGGCCGCCCGGGCA GGT-3 |

| Adaptor 2 | 3-H2N-CCCGTCCA-P-5 |

| Adaptor 1 primer | 5-GATCCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGC-3 |

| Adaptor 1 nested primer | 5-A ATA GGG CTC GAG CGG C- 3 |

| Tn10C | 5-GCTGACTTGACGGGACGGCG-3 |

| Tn10D | 5-CCTCGAGCAAGACGTTTCCCG-3 |

DNA sequence analysis

Homology searches and sequence comparisons were performed in GenBank, National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) using the BLAST-search algorithm. Open reading frames (ORFs) were determined by the ORF Finder program through the NCBI website. Promoter prediction was performed using the BPROM program, which predicts bacterial promoters and is available through the Softberry website (http://linux1.softberry.com/berry.phtml?topic=index&group=program&subgroup=promoter).

Gene deletions

The plasmid pCVD443 is a suicide plasmid derived from pCVD44241, which encodes the sacB counter-selectable marker, by adding the 977bp kanamycin-resistance gene cassette from plasmid pLOF/Km in the SmaI site. This plasmid was used to facilitate deletion of the majority of the DNA corresponding to each of the seven ORFs individually. To create the plasmids for deletion mutants pDM1 pDM7, chromosomal DNA upstream and downstream of each ORF was amplified by PCR, joined by overlap extension PCR (Table 4), and cloned into pCVD443 as a SalI SphI fragment. Each deletion fragment consisted of approximately 750bp of DNA upstream of the targeted ORF plus 51bp of the 5 end joined in-frame to the last 51bp of the ORF followed by approximately 750bp of downstream DNA. Plasmids pDM1 - 7 were transferred into E. coli SM10 (pir) to serve as donor strain and conjugated with P. luteoviolacea (HI1, Smr). Single recombinants were selected on SWT agar plates supplemented with kanamycin (200g/ml) and streptomycin (200g/ml). After checking the success of the first recombination, one colony was inoculated into SWT broth medium without antibiotics and incubated at room temperature (25C) overnight. The bacterial broth was diluted 10 fold, spread onto SWT agar plates with 5% sucrose (W/V), and incubated at room temperature overnight. The resulting colonies were screened for kanamycin sensitivity and sucrose resistance. PCR was applied to confirm that the ORFs were deleted in selected strains. Primers were designed to complement the flanking region of each of the ORFs of interest (Table 5). The sizes of amplified DNA fragments were compared using chromosomal DNA of wild type P. luteoviolacea (HI1) and chromosomal DNA of the deletion mutants as templates.

Table 4. Sequences of oligonucleotides used in overlapping extension PCR to generate plasmids pDM 1-7.

| ORF1 | ||

| Pldm1-1L | 5-TTTGTCGACCAATCTCGTTAGGCGAAAGC-3 | |

| Pldm1-1R | 3-CAATCCCTTCGTCGACCCCTTTACCGTTGC CAGAGAT-5 | |

| Pldm1-2L | 5-CGGTAAAGGGGTCGACGAAGGGATTGGAA AATGGA-3 | |

| Pldm1-2R | 3-TTTGCATGCACGGGTTAAATTAGGCGATA-5 | |

| ORF2 | ||

| Pldm2-1L | 5-TTTGTCGACGTCGCTTATATCGGCGTGTC-3 | |

| Pldm2-1R | 3-CGATAAATTTCCCAGGGTTTAGCACAGCATC-5 | |

| Pldm2-2L | 5-AAACCCTGGGAAATTTATCGTGGCGACCAG-3 | |

| Pldm2-2R | 3-TTTGCATGCACCTAACATCGGCGCTTCTA-5 | |

| ORF3 | ||

| Pldm3-1L | 5-TTTGTCGACAGCGATCTACTGGGGAATGA-3 | |

| Pldm3-1R | 3-GCGCATGCCATTGGTCACATTCGACTAACACTT-5 | |

| Pldm3-2L | 5-ATGTGACCAATGGCATGCGCTGTATTTAG-3 | |

| Pldm3-2R | 3-TTTGTCGACGAAAACTCTGGCTGCGCTAC-5 | |

| ORF4 | ||

| Pldm4-1L | 5-GTCGACCATCGCCAGGTTTCTAGAGC-3 | |

| Pldm4-1R | 3-CTAACCAAGGGTGTGCAGGGGCTTCTAATT-5 | |

| Pldm4-2L | 5-CCCTGCACACCCTTGGTTAGACACCGATCTT-3 | |

| Pldm4-2R | GTCGACCCAAGACGTGTATTTGACCTTT-5 | |

| ORF5 | Pldm5-1L | 5-GTCGACGTCGGGTCGAACGTATTTCT-3 |

| Pldm5-1R | 3-GAAAATCCGAATAATTGGTTTTGGGCGTTG-5 | |

| Pldm5-2L | 5-AACCAATTATTCGGATTTTCTAAGCCTGGTT-3 | |

| Pldm5-2R | GTCGACTTTGAGCTGCGATGTTTGAG-5 | |

| ORF6 | ||

| Pldm6-1L | 5-GCATGCACGCCCAAAACCAATTATCA-3 | |

| Pldm6-1R | 3-TTTCAATTCTCGCATATTGAAATGCCTCTTG-5 | |

| Pldm6-2L | 5-TCAATATGCGCTCATTGAAAATAGGCGATTA-3 | |

| Pldm6-2R | 3-GTCGACTGGTCACTTTTTGCATACTTTCA-5 | |

| ORF7 | Pldm7-1L | 5-TTTGTCGACTGCAGTTTCCACATCTACCC-3 |

| Pldm7-1R | 3-TTGGCACTGTTTGCCCTTCTTGTTCAAAGG-5 | |

| Pldm7-2L | 5-AGAAGGGCAAACAGTGCCAAGTGAACGATTT-3 | |

| Pldm7-2R | 3-TTTGCATGCTAACACCATTTGGGCGATTT-5 |

Table 5. Sequences of oligonucleotides to check the presence of 7 ORFs.

| ORF1 | |

| 5-CGCACCGCTTATCCTTTTAC-3 | |

| 3-TTTGGCGTCGCTTTAAATGT-5 | |

| ORF2 | |

| 5-GAAGGGATTGGAAAATGGA-3 | |

| 3-TTGGTCACATTCGACTAACACTT-5 | |

| ORF3 | |

| 5-AAATTTATCGTGGCGACCAG-3 | |

| 3-GTGTGCAGGGGCTTCTAATT-5 | |

| ORF4 | |

| 5-GGCGTAACGACCACGTTTA-3 | |

| 3-ATAATTGGTTTTGGGCGTTG-5 | |

| ORF5 | |

| 5-CCTTGGTTAGACACCGATCTT-3 | |

| 3-CCAAGACGTGTATTTGACCTTT-5 | |

| ORF6 | |

| 5-TCGGATTTTCTAAGCCTGGTT-3 | |

| 3-TTGCCCTTCTTGTTCAAAGG-5 | |

| ORF7 | |

| 5-TGAAGGTTTTCCCAGTCCAC-3 | |

| 3-TGGTCACTTTTTGCATACTTTCA-5 |

Southern blot

Genomic DNA of wild type P. luteoviolacea (HI1) and P. luteoviolacea ATCC334926 was extracted with a MoBio UltracleanTM Microbial DNA kit following the manufacturer's instructions. One microgram of genomic DNA of both strains of bacteria was digested with restriction enzyme Hind III or Kpn I at 37C overnight. Hybridization probes were designed from ORFs 14 (Probe primers are listed in table 6), amplified by PCR, and biotinylated with NEBLOT Phototope kit (NEB) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Southern blot was performed with standard technique42,43,44. Blots were detected with a LightShift Chemiluminescent RNA EMSA Kit (Thermo Scientific) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Table 6. Sequences of oligonucleotides to generate probes for southern blot.

| ORF1 | |

| 5-CAACCTGGCACTCAGTTTGA-3 | |

| 3-CAGCTGAGGGGTAAAACCAA-5 | |

| ORF2 | |

| 5-CGCGCATTTGCTGGCACGTTTTG-3 | |

| 3-TCTTCGCTAAACCCATCAGG-5 | |

| ORF3 | |

| 5-GGTGATAGCGAAATGCAGGT-3 | |

| 3-GACAGCTTGCCGTTGACATA-5 | |

| ORF4 | |

| 5-CACCAGCCAGCGTTATTTTT-3 | |

| 3-CAATTCACCGGCAGTAACAT-5 |

Reverse transcription PCR

Total RNA isolation from overnight cultures of P. luteoviolacea (HI1) was performed in TRI REAGENT according to the manufacturer's instructions. Contaminating chromosomal DNA in RNA samples was digested with DNase I for 3 times. First strand complementary DNA was synthesized from DNase I-treated total RNA using gene specific primers that complement the sequence of each targeted open reading frame (Table 7). Two g of total RNA were mixed with 40M gene specific primers and 2.5mM dNTP, incubated at 65C for 5 minutes, and placed promptly on ice for 2 minutes. 200 units of M-MuLV reverse transcriptase, 10X RT buffer, and 1l of RNase inhibitor were added to the tube and incubated at 42C for one hour. Another set of reactions replaced reverse transcriptase with H20 and served as negative controls.

Table 7. Sequences of the primers used for cDNA synthesis and PCR.

| Amplified region | Nucleotide sequence (5 -3) | |

|---|---|---|

| Primers for cDNA synthesis | ||

| Upstream of ORF2 | AATACATTGTGGTCGCTCCA | |

| Upstream of ORF3 | CCAGAGACGCGTAAAACCTC | |

| Upstream of ORF4 | GCTGCTCAACCGCAGTATAA | |

| Upstream of ORF5 | CCAAGACGTGTATTTGACCTTT | |

| Upstream of ORF6 | TTGCCCTTCTTGTTCAAAGG | |

| Upstream of ORF7 | TGGTCACTTTTTGCATACTTTCA | |

| Primer pairs for PCR | ||

| Intergenic region between ORF1 and ORF2 | TTAGTTCCGACACGCAATCA | |

| CTGTGCTCGCAAACCATCTA | ||

| Intergenic region between ORF2 and ORF3 | AAATTTATCGTGGCGACCAG | |

| TTCAAAATCATCCCCTGTCG | ||

| Intergenic region between ORF3 and ORF4 | TTAGAAGCCCCTGCACACTT | |

| AACGCATTTAGGTCAATATCTGG | ||

| Intergenic region between ORF4 and ORF5 | GCCCATCGATGCATTTAGAC | |

| TCCGCAACTTGATACTGCTG | ||

| Intergenic region between ORF5 and ORF6 | CCGACTGCGGATATGCAGTTTCCA | |

| TGAGCCACTCGATGAGTTTG | ||

| Intergenic region between ORF6 and ORF7 | TGATTCTTGCTGCTAAAACTTGA | |

| TGAAGGTTTTCCCAGTCCAC | ||

To determine the organization of the gene cluster between ORF1 to ORF7, primer pairs were designed to complement the 3-end of one ORF and 5-end of the succeeding ORF (Table 7). cDNAs synthesized with each gene specific primer were used as templates. Chromosomal DNA was used as a template in the same PCR as a positive control.

Growth rate determination

One colony of wild type P. luteoviolacea (HI1) and each of the 4 deletion mutant strains (PlDM 14) were inoculated into 2ml of SWT broth medium and incubated overnight. 100l of overnight culture of each strain was then inoculated into 10ml of SWT broth. Three replicates were prepared for each strain. The optical density at 600nm was recorded every half hour for 6hours. At each time point, the OD values were read 3 times, and the mean value was recorded.

Biofilm preparation and biofilm staining or labeling

Biofilms of P. luteoviolacea (HI1) and the 7 deletion mutants were formed on coverslips as described by Huang and Hadfield12. Biofilms on the coverslips were fixed in 3% formaldehyde in FSW for at least 10 minutes. Bacterial cells were stained by 100ng/ml of 4, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, dihydrochloride (DAPI, Sigma). EPS in the biofilms were labeled by 10g/ml of lectins conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) as describe by Strathmann et al.45. Lectins used were concanavalin A (Con A, Sigma) (10g/ml) and wheat germ agglutinin (WGA, Sigma).

Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) and image analysis

All microscopic observations and image acquisition were performed on a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal laser scanning microscope (Zeiss, NY, USA). Three to five replicate biofilms were examined for each strain of bacteria. Ten non-overlapping fields of view of each biofilm were chosen randomly for imaging and analysis. Each field of view had an area of 220m220m. 1620 image stacks of varying thicknesses were generated to determine the full thickness of the biofilm in each field of view. Bacterial densities were counted using Image J software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/). Other biofilm parameters were quantified using COMSTAT software46.

Statistical analysis

The data were arcsine-transformed according to the needed and tested for normality and homogeneity of variance by using Shapiro-Wilk's test and Cochran's C-test. If the assumptions for a parametric test were met, then means were compared among strains using ANOVA; if not, a nonparametric Wilcoxon analysis was performed using a Kruskal-Wallis chi-square approximation to indicate the significance of differences using the untransformed data47.

Author Contributions

YH carried out all laboratory procedures under the guidance of SC and MGH. All authors contributed to writing the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. E. G. Ruby and S. Egan for supplying plasmids important for carrying out this research. Advice from E. G. Ruby was also important. The research was supported by Office of Naval Research Grants nos. N00014-08-0413 and N00014-11-0533 and U.S. National Science Foundation grant no. IOS-0842681 to MGH.

References

- Hadfield M. G. & Paul V. J. in Marine Chemical Ecology (eds J. B. McClintock & W. Baker ) 431–461. (CRC Press, 2001). [Google Scholar]

- Woollacott R. M., Hadfield M. G. Induction of metamorphosis in a larvae of a sponge. Inv. biol. 115, 257–262. (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Leitz T. Induction of metamorphosis the marine hydrozoan Hydractinia echinata Fleming, 1828. Biofouling 12, 173–187. (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Kirchman D., Graham S., Reish D. & Mitchell R. Bacteria induce settlement and metamorphosis of Janua (Dexiospira) brasiliensis Grube (Polychaete: Spirorbidae) J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 56, 153–163. (1982). [Google Scholar]

- Unabia C. R. C. & Hadfield M. G. Role of bacteria in larval settlement and metamorphosis of the polychaete Hydroides elegans. Mar. Biol. 133, 55–64. (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Huggett M. J., Williamson J. E., Nys R., Kjelleberg S. & Steinberg P. D. Larval settlement of the common Australian sea urchin Heliocidaris erythrogramma in response to bacteria from the surface of coralline algae. Oecologia 149, 604–619. (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster N. S. et al. Metamorphosis of a scleractinian coral in response to microbial biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 1213–1221. (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadfield M. G. Biofilms and marine invertebrate larvae: What bacteria produce that larvae use to choose settlement sites. Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci. 3, 453–470. (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieczorek S. K. & Todd C. D. Inhibition and facilitation of bryozoan and ascidian settlement by natural multi-species biofilms: effects of film age and the roles of active and passive larval attachment. Mar. Biol. 128, 463–473. (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Keough M. J. & Raimondi P. T. Responses of settling invertebrate larvae to bioorganic films: effects of different types of films. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 185, 235–253. (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Wieczorek S. K., Clare A. S. & Todd C. D. Inhibitory and facilitatory effects of microbial films on settlement of Balanus amphitrite amphitrite larvae. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 119, 221–228. (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Huang S., Hadfield M. G. Composition and density of bacterial biofilms determine larval settlement of the polychaete Hydroides elegans. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 260, 161–172. (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Maki J. S., Rittschof D., Costlow J. D. & Mitchell R. Inhibition of attachment of larval barnacles, Balanus amphitrite, by bacterial surface films. Mar. Biol. 97, 199–206. (1988). [Google Scholar]

- Kirchman D., Graham S., Reish D. & Mitchell R. Lectins may mediate in the settlement and metamorphosis of Janua (Dexiospira) brasiliensis Grube (Polychaeta:Spirobidae). Mar. Biol. lett. 3, 131–142. (1982). [Google Scholar]

- Khandeparker L., Anil A. C. & Raghukumar S. Barnacle larval destination: piloting possibilitiies by bacteria and lectin interaction. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 289, 1–13. (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Szewzyk U. et al. Relevance of the exopolysaccharide of marine Pseudomonas sp. Strain S9 for the attachment of Ciona intestinalis larvae. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 75, 259–265. (1991). [Google Scholar]

- Leitz T. Induction of settlement and metamorphosis of Cnidarian larvae: signals and signal transduction. Inv. Reprod. Dev. 31, 109–122. (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann D. K. & Brand U. Induction of Metamorphosis in the Symbiotic Scyphozoan Cassiopea andromeda: Role of Marine Bacteria and of Biochemicals. Symbiosis 4, 99–116. (1987). [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer-Faust R. K. & Tamburri M. N. Chemical identity and ecological implications of a waterborne, larval settlement cue. Limnol. Oceanogr. 39, 1075–1087. (1994). [Google Scholar]

- Hung O. S. et al. Characterization of cues from natural multi-species biofilms that induce larval attachment of the polychaete Hydroides elegans. Aquat. Biol. 4, 253–262. (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Swanson R. L. et al. Induction of Settlement of Larvae of the Sea Urchin Holopenustes purpuracens by Histamine From a Host Alga. Bioligical Bulletin 206, 161–172. (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tebben J. et al. Induction of larval metamorphosis of the coral Acropora millepora by tetrabromopyrrole Isolated from a Pseudoalteromonas Bacterium. PloS one 6, 1–8. (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedved B. T. & Hadfield M. G. in Marine and Industrial Biofouling (eds H. C. Flemming, R. Venkatesan, S. P. Murthy, & K. Cooksey) (Springer, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- Carpizo-Ituarte E. & Hadfield M. G. Stimulation of metamorphosis in the polychaete Hydroides elegans Haswell (Serpulidae). Biol. Bull. 194, 14–24. (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadfield M. G., Unabia C. C., Smith C. M. & Michael T. M. in Recent Developments in Biofouling Control (eds M. F. Thompson, R. Nagabhushanam, R. Sarojini, M. Fingerman) 65–74. (Oxford and IBH Publishing Co., 1994). [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier G., Gauthier M. & Christen R. Phylogenetic analysis of the genera Alteromonas, shewanella, and Moritella using genes coding for small-subunit rRNA sequences and division of the genus Alteromonas into two genera, Alteromonas (Emended) and Pseudoalteromonas gen. nov., and proposal of twelve new species combinations. .Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 45, 755–761. (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pell L. G., Kanelis V., Donaldson L. W., Lynne Howell P. & Davidson A. R. The phage major tail protein structure reveals a common evolution for long-tailed phages and the type VI bacterial secretion system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 4160–4165. (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiman P. G. et al. From the Cover: Type VI secretion apparatus and phage tail-associated protein complexes share a common evolutionary origin. Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. 106, 4154–4159. (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter N., Breicha K., Hummel W. & Niefind K. The three-dimensional structure of AKR11B4, a glycerol dehydrogenase from Gluconobacter oxydans, reveals a tryptophan residue as an accelerator of reaction turnover J. Mol. Biol. 404, 353–362. (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Tahir Y. & Skurnik M. YadA, the multifaceted Yersinia adhesin. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 291, 209–218. (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmstrom C. & Kjelleberg S. Marine Pseudoalteromonas species are associated with higher organisms and produce biologically active extracellular agents. FEMS Microbiology Immunology 30, 285–293. (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skovhus T. L., Holmstroem C., Kjelleberg S. & Dahllof I. Molecular investigation of the distribution, abundance and diversity of the genus Pseudoalteromonas in marine samples. Fems Microbiology Ecology 61, 348–361. (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran C. & Hadfield M. G. Settlement and metamorphosis of the larvae of Pocillopora damicornis (Anthozoa) in response to surface-biofilm bacteria. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 433 8596 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Maki J. S., Rittschof D., Schmidt A. R., Snyder A. C. & Mitchell R. Factors controlling attachment of bryozoan larvae: A comparison of bacterial films and unfilmed surfaces. Biol. Bull. 177, 295–302. (1989). [Google Scholar]

- Qian P. Y., Thiyagarajan V., Lau S. C. K. & Cheung S. C. K. Relationship between bacterial community profile in biofilm and attachment of the acorn barnacle Balanus amphitrite. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 33, 225–237. (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Dobretsov S. & Qian P. Y. Facilitation and inhibition of larval attachment of the bryozoan Bugula neritina in association with mono-species and multi-species biofilms. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 333, 263–274. (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Hayes C. S., Aoki S. K., and Low D. A. Bacterial contact-dependent delivery systems. annual Review of Genetics 44, 71–90. (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pukatzki S., Ma A. T., Revel A. T., Sturtevant D. & Mekalanos J. J. Type VI secretion system translocates a phage tail spike-like protein into target cells where it cross-links actin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 15508–15513. (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan S., James S. & Kjelleberg S. Identification and characterization of a putative transcriptional regulator controlling the expression of fouling inhibitors in Pseudoalteromonas tunicata. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68, 372–378. (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siebert P. D., Chenchik A., Kellogg D. E., Lukyanov' K. A. & Lukyanov' S. A. An improved PCR method for walking in uncloned genomic DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 23, 1087–1088. (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnenberg M. S. & Kaper J. B. Construction of an eae deletion mutant of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli by using a positive-selection suicide vector. Infec. Immun. 59, 4310–4317. (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausubel F. M. et al. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1989). [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J., Fritsch E. F. & Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 1989). [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J. & Russell D. W. Molecular cloning: A laboratory manual (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 2001). [Google Scholar]

- Strathmann M., Wingender J. & Flemming H. C. Application of fluorescently labelled lectins for the visualization and biochemical characterization of polysaccharides in biofilms of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Microbiol. Methods 50, 237–248. (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heydorn A. et al. Quantification of biofilm structure by the novel computer program COMSTAT. Microbiology 146, 2395–2407. (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokal R. R. & Rohlf F. J. Biometry:the principles and practice of statistics in biological research. 2nd edn, 859 (W. H. Freeman and Company, 1981). [Google Scholar]

- Herrero M., Lorenzo V. d. & Timmis, K. N. Transposon Vectors Containing Non-Antibiotic Resistance Selection Markers for Cloning and Stable Chromosomal Insertion of Foreign Genes in Gram-Negative Bacteria. Journal of Bacteriology 172, 6557–6567. (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]