Abstract

Aims

To construct AA attendance, sponsorship, and abstinence latent class trajectories to test the added benefit of having a sponsor above the benefits of attendance in predicting abstinence over time.

Design

Prospective with 1-, 3-, 5-, and 7-year follow-ups.

Setting and participants

Alcoholic-dependent individuals from two probability samples, one from representative public and private treatment programs and another from the general population (n=495).

Findings

Individuals in the low attendance class (4 classes identified) were less likely than those in the high, descending, and medium attendance classes to be in high (vs. low) abstinence class (3 classes identified). No differences were found between the other attendance classes as related to abstinence class membership. Overall, being in the high sponsor class (3 classes identified) predicted better abstinence outcomes than being in either of two other classes (descending and low), independent of attendance class effects. Though declining sponsor involvement was associated with greater likelihood of high abstinence than low sponsor involvement, being in the descending sponsor class also increased the odds of being in the descending abstinence class.

Conclusions

Any pattern of AA attendance, even if it declines or is never high for a particular 12-month period, is better than little or no attendance in terms of abstinence. Greater initial attendance carries added value. There is a benefit for maintaining a sponsor over time above that found for attendance.

Keywords: AA sponsor, AA meetings, longitudinal outcomes, trajectories analysis, latent classes

INTRODUCTION

In countries like the USA, the last decade has seen a nascent discourse encouraging a shift from acute care to a chronic-care model that acknowledges the relapsing nature of addiction and hence a need for ongoing care.1,2 Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and other 12-step groups represent a critical component of this model, as they offer the only universally available source of continued support. The benefits of AA involvement for treatment seeking problem drinkers has been well established 3-7 and, as well, evidence has shown that facilitating AA attendance (and other AA behaviors) improves abstinence outcomes.8,9 Data from Project MATCH is an example of one such study that provided early experimental evidence suggesting the effectiveness of treatments that facilitate AA involvement.10,11 Unfortunately the literature offers limited guidance regarding what type of specific 12-step activities clinicians should recommend to their clients.,9,12,13 We look specifically at one such activity, having an AA sponsor, and test its relationship to patterns of meeting attendance over time.

Most studies of AA have focused on attendance or have used scales14-17 that reflect a count of prescribed activities such as reading the literature, considering oneself a member, having an AA sponsor, working the steps, and doing service in AA. This body of work has found, in general, that more attendance4,6,18-24 and greater overall involvement16,25-29 are associated with higher abstinence rates, but with some debate about which behavior(s) might be more predictive.16,25 Only a few studies have looked at particular activities as predictors of abstinence.3,16,30-35 For example, having a sponsor following treatment is a significant predictor of during-treatment36 and 6-month37-39 and 12-month abstinence.31,38,40-42 Being a sponsor is even more important, with sustained sponsorship the best predictor of 10-year abstinence in severe individuals43 (also see44-46). Aside from attendance,19,47,48 few longitudinal studies have looked at the influence of particular AA activities on more distal abstinence outcomes.49,50

This paper adds to that literature using latent class growth analysis (LCGA), a longitudinal statistical technique, to classify alcoholic-dependent individuals into distinct groups based on their response patterns over time. As applied here, LCGA allows us to empirically construct trajectories that identify naturally-occurring prototypical patterns of attendance, of having a sponsor, and of abstinence over a 7-year period. We then are able to study how well these patterns (or “classes”) of attendance, and of having a sponsor, predict the dominant patterns of abstinence (and its converse, drinking) across parallel timeframes. We consider attendance because it is the most basic aspect of AA participation and it has been associated with positive outcomes in several studies.8 We chose having a sponsor over being a sponsor, a stronger predictor of abstinence, because having sponsor usually precedes being a sponsor (i.e., one learns how to be a sponsor by having had the experience of being sponsored). We also know from prior work with these data that only a small percentage of attendees reported being a sponsor at follow-up interviews.30 Finally, we study abstinence (rather than, say, drinking less) because 12-step groups are abstinence oriented.

In prior work with these data, LCGA was used to study patterns of meeting attendance over 5 years49 and 7 years,50 finding evidence for four attendance patterns: low, medium, descending, and high. Individuals in the high attendance class reported the highest average rates of prior 30-day abstinence at each interview, followed very closely by those in the descending class. Abstinence rates were lower on average for individuals in the medium attendance class, and lowest for the low class. Although these comparisons of point estimates of abstinence (within class averages at each follow-up) for the various attendance classes are informative, this prior work could not distinguish whether prototypical patterns of AA attendance were related to prototypical patterns of abstinence over time. This requires constructing trajectories of abstinence, as we do here. Further, the common patterns for being sponsored over time (and their relative value, in terms of abstinence) are yet unknown, and are also considered here. Thus we can see, for example, whether individuals in the high attendance class (or high sponsor class) populate the high abstinence class.

As with our earlier trajectories work studying AA attendance with this sample,49,50 we hypothesize (1) a pattern of high abstinence over time even among those whose attendance may decline from initial high levels. This is supported by research suggesting that steady lifelong attendance may not be necessary, but that initial high levels of attendance are essential.48,51 The same may well be true for having a sponsor, although there is little prior work upon which to build our hypotheses. Highlighting the importance of timing and analytic approach, longitudinal lagged analyses by Tonigan39 found that having a sponsor at 3 months predicted 6-month, but not 12-month, abstinence, but also found effects for concurrently having a sponsor and abstinence at 12 months. We hypothesize (2) that individuals who maintain a sponsor over time will maintain a high abstinence pattern over time, regardless of their attendance patterns. Since initial support from a sponsor might be paramount (e.g., by helping individuals feel like they belong, helping them work the steps, etc.), we further hypothesize (3) that those who only maintain contact with a sponsor early-on (years 1and 3) will have better abstinence patterns than those with continually low sponsor involvement, regardless of their pattern of attendance. Finally, we hypothesize (4) that those who have little or no sponsor involvement, or who have low meeting attendance at all follow-ups, will have the lowest abstinence patterns.

METHODS

Sample and recruitment

Data come from a study conducted in a Northern California County comprised of a socially and culturally diverse population (approximately 900,000). The county has a mix of rural and urban areas and reflects national patterns in the relationship of substance use to other health and social problems. This county served as the US site for the World Health Organization’s study of community response to alcohol and drug problems.52-54 Study participants included a probability sample of 926 dependent and problem users recruited when they sought specialized treatment at representative public, private, and health maintenance organization programs; and a probability sample of 672 untreated problem drinkers from the general population recruited in the same county.

More detail on recruitment and study methodology can be found in earlier papers.52,55 Briefly, the treatment sample was recruited from consecutive new admissions from ten county-wide programs (80% recruitment rate). Participants were interviewed in-person. The general population sample was generated using random digit dialing, screened for problem drinking and for not having had treatment in the past year, and then interviewed in-person (70% recruitment rate). Problem drinking was defined as meeting at least two of the following criteria for the prior 12-month period: 1) drank five or more drinks on an occasion at least once a month for men: three or more drinks a week for women, 2) experienced one or more alcohol-related social consequences (out of 8 total), and 3) reported one or more alcohol dependence symptoms (out of 9 total).

Participants were re-interviewed by telephone 1, 3, 5 and 7 years later, using the same follow-up instrument (respective response rates 84%, 82%, 79%, and 75%). Because of our focus on AA over time, and because AA is primarily a resource intended for alcoholics, this paper uses only individuals with a baseline DSM-IV alcohol-dependence diagnosis (n=590) and whose data on AA utilization and abstinence were available at one or more follow-up interviews (n=88 individuals had no follow-up data and n=7 had missing attendance data). Among the n=495 in the retained sample, 70% were interviewed at all four follow-ups (84% at three or more follow-ups). Those excluded because they were not alcohol dependent were either problem drinkers and/or drug dependent.

Measures

The Diagnostic Interview Schedule was used to determine baseline DSM-IV substance dependence.56-58 To be alcohol dependent, a participant had to exhibit at least 3 of 7 symptoms.59 Other baseline measures known to be associated with formal and informal help-seeking and outcomes60,61 were also used as candidate predictor variables: age, religiosity (from the Religious Background and Behaviors scale 62), and alcohol problem severity (using the Addiction Severity Index 63-65). At each interview, AA questions assessed the number of meetings attended in the past year, and currently having a sponsor. Abstinence at each interview was based on having reported zero drinking days in the past 30 days (from the ASI 64).

Statistical analysis

Three sets of latent class growth analyses (LCGA) were used to respectively identify latent class trajectories for AA attendance, having a sponsor, and abstinence. Block-entry (2 blocks) multinomial regression next tested whether our latent class sponsor trajectories were predictive of particular abstinence trajectories, after controlling for the effects of attendance trajectories. LCGA analyses were conducted in Mplus, Version 5.1,66 which incorporates a Full Information Maximum Likelihood estimation, under the assumption that the data are missing at random.67,68 In theory this method provides the same result as multiple imputation and it means that no bias is introduced by using only cases with data at every interview.

We followed a recommended procedure to build models,69 determining the best number of classes based on theoretical justification, parsimony, interpretability, and the a priori decision that no single class would be comprised of less than 5% of the total sample. Model fit was based on the Baysian information criteria,70 posterior probabilities, and entropy (a measure of classification uncertainly, with values approaching 1.00 indicating a more precise class assignment66).

RESULTS

Sample

This alcohol-dependent sample was 39% female, 38 years old on average, 27% unmarried/partnered, 60% white and 25% black, and educated twelve (48%) or more years (33%). Most self-identified as religious or spiritual (80%). The treatment sample had higher ASI alcohol severity (.597 vs. .347) and a co-occurring drug dependence disorder (42% vs. 20%) than the general population sample: the general population sample was younger (34 vs. 40 years) and fewer were non-white (36% vs. 41%). A higher proportion of females, individuals with lower ASI alcohol severity, and individuals from the general population sample were interviewed at all follow-ups. Being interviewed at all follow-ups (vs. not), however, was not associated with having reported AA attendance or having a sponsor at any follow-up.

AA attendance trajectories

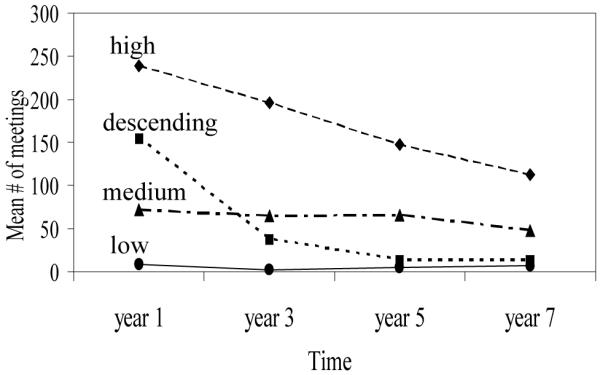

The 4-class solution provided more distinct and interpretable classes than alternative solutions, with an entropy value of .67 (suggesting moderate distinction) and posterior probabilities of 1.0, .99, .94 and .70 (see Table 1, diagonal values). Refer to Table 2 for the parameter estimates, standard errors, and tests of significance for this model (as well as the sponsor and abstinence models). Attendance trajectories (Figure 1) include 1) a low group (n=308) whose attendance was minimal at every follow-up (5-6 meetings a year on average), 2) a medium group (n=69) whose attendance averaged about 60 meetings a year (or about 1 meeting per week on average) at each interview, 3) a descending group (n=81) whose high attendance at year 1 decreased steeply at year 3 (from about 3 meetings a week to <1 meeting a week on average) and then mostly leveled to near that of the low group at years 5 and 7, and 4) a high AA group (n=37) whose high attendance declined steadily from year 1 to year 7 (from about 5 meetings a week to 2 meetings a week on average). From Table 1, we see that individuals in the low class also had a 12% probability of membership in the descending class, the same probability of membership in the medium class, and a 6% probability of being in the high class.

Table 1.

Mean latent class posterior probabilitiesa for most likely latent class membership.

| Class assignment | ||||

| AA attendance | high | medium | descending | Low |

| high (n=37) | 1.0 | .00 | .00 | .00 |

| medium (n=69) | .00 | 0.99 | .00 | >.01 |

| descending (n=81) | .01 | .02 | .94 | .03 |

| low (n=308) | .06 | .12 | .12 | .70 |

|

| ||||

| AA sponsor | High | descending | low | |

| high (n=75) | .88 | .08 | .04 | |

| Descending (n=71) | .11 | .77 | .12 | |

| low (n=349) | .01 | .07 | .92 | |

|

| ||||

| Abstinence | High | descending | low | |

| high (n=202) | .90 | .02 | .07 | |

| Descending (n=35) | .32 | .60 | .08 | |

| low (n=256) | .06 | .01 | .93 | |

Posterior probabilities classify observations during the estimation of model parameters, as well as after the estimation when observations are assigned to the most likely class.

Table 2.

Summary of latent class analysis model parameters for initial AA attendance, sponsor, and abstinence levels (intercept), time (linear and quadratic) and respective baseline variables in each class.

| Class (% of sample) | Parameter | Estimate | (se) | p-val. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a AA attendance | ||||

| High (7%) | Intercept | 5.63 | (<.00) | <.001 |

| Linear | .01 | (<.00) | <.001 | |

| Quadratic | −.01 | (<.00) | <.001 | |

| Medium (14%) | Intercept | 4.14 | (0.01) | <.001 |

| Linear | .25 | (<.00) | <.001 | |

| Quadratic | −.03 | (<.00) | <.001 | |

| Descending (16%) | Intercept | 6.12 | (<.00) | <.001 |

| Linear | −.90 | (<.00) | <.001 | |

| Quadratic | .07 | (<.00) | <.001 | |

| Low (62%) | Intercept | 3.37 | (0.01) | <.001 |

| Linear | −.41 | (<.01) | <.001 | |

| Quadratic | .06 | (<.00) | <.001 | |

| High vs. low | Attendance d | .01 | (<.00) | .004 |

| Medium vs. low | Attendance d | .01 | (<.00) | (.087) |

| Descending vs. low | Attendance d | .01 | (<.00) | <.001 |

|

| ||||

| b AA sponsor | ||||

| High (15%) | Intercept | 4.33 | (7.74) | |

| Linear | .41 | (0.40) | ||

| Quadratic | −.05 | (0.05) | ||

| Descending (14%) | Intercept | 5.25 | (5.76) | |

| Linear | −.80 | (0.91) | ||

| Quadratic | <.00 | (0.12) | ||

| Low (70%) | Intercept | .00 | (<.00) | |

| Linear | −.09 | (2.60) | ||

| Quadratic | .03 | (0.22) | ||

| High vs. low | Sponsor d | 2.69 | (0.93) | .004 |

| Descending vs. low | Sponsor d | 2.21 | (0.72) | .002 |

|

| ||||

| c Abstinence | ||||

| High (40%) | Intercept | .00 | <.00 | |

| Linear | .14 | .08 | (.074) | |

| Descending (7%) | Intercept | 52.44 | .78 | <.001 |

| Linear | −10.83 | <.00 | ||

| Low (53%) | Intercept | −3.20 | .41 | <.001 |

| Linear | −.01 | .06 | ||

| High vs. low | Abstinence d | 1.73 | .83 | .037 |

| Descending vs. low | Abstinence d | −173.41 | .83 | <.001 |

LCA with: count outcome using a zero-inflated Poisson model, with a quadratic term for time;

binary outcome, with a quadratic term for time;

count outcome, without a quadratic term for time.

Respective baseline values with ‘low’ as reference group.

Figure 1.

AA meeting attendance by latent class and time

Sponsor trajectories

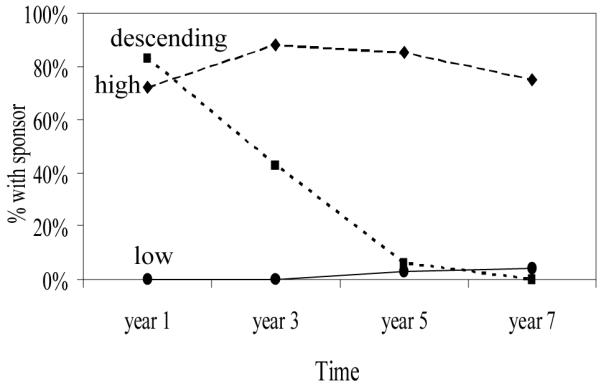

The 3-class solution provided distinct classes, with entropy being 0.72 (suggesting a moderate-to-high distinction) and posterior probabilities of 0.88, 0.77, and 0.92. The sponsor trajectories (Figure 2) include 1) a low group (n=352) whose likelihood of having a sponsor stayed steady, increasing slightly at year 3 (ranging on average from 0% to 4% ), 2) a descending group (n=72) whose likelihood of having a sponsor was high at year 1 (72%) and then declined sharply by year 5 when it leveled to almost no one having a sponsor, and 3) a high group (n=77) whose likelihood of having a sponsor rose slightly from year 1 to year 3 (from 72% to 88%) and then declined to 75% at year 7. The off-diagonal probabilities (Table 1) show that individuals assigned to the descending class had a 12% probability of membership in the low class and 11% probability of membership in the high class.

Figure 2.

Have an AA sponsor by latent class and time

Alcohol abstinence trajectories

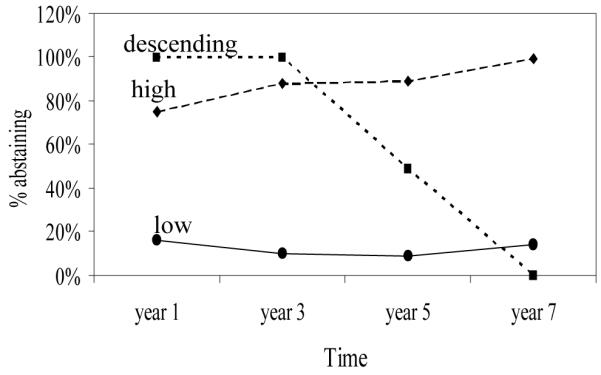

A simple 3-class solution provided the best overall fit and interpretability, with entropy being .79 and posterior probabilities 0.90, 0.60, and 0.93. In addition, its descending class (though small) has high face validity (i.e., we would expect some persons might do well at first and then later relapse). The abstinence trajectories (Figure 3) include 1) a low group (n=263) whose likelihood of abstinence averaged about 12% across the four follow-ups, 2) a descending group (n=35) whose rate of attendance was high years 1 and 3 (all 35 individuals were abstinent) and then declined from about half abstinent at year 5 to none abstinent at year 7, and 5) a high group (n=202) whose likelihood of abstinence rose slightly after year 1 (from 75% to nearly 100% on average at year 7). Those assigned to the descending class had a 32% chance of membership in the high class, suggesting some instability in the parameter.

Figure 3.

30-day abstinence by latent class and time

Bivariate relationships between attendance, sponsor and abstinence classes

To describe the degree of commonality among the classes, we next looked at how well the attendance classes and sponsor classes overlaid with the abstinence classes (Table 3). Correspondingly high percentages of individuals in the high, descending and medium attendance classes were in the high abstinence class (76%, 63% & 56% respectively), while only about a quarter (28%) from the low attendance class were in that high abstinence class. A similar (gradient) relationship was found between the sponsor and abstinence classes. Three-quarters of those in the high sponsor class (75%) followed by over half (56%) in the descending sponsor class were in the high abstinence class. Conversely, two-thirds (66%) of those in the low abstinence class were in the low attendance and low sponsor classes.

Table 3.

Proportions of individuals within the sponsor classes and attendance classes by abstinence class membership, and sponsor class by attendance class membership.

| Sponsor class (%) |

Attendance class (%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Descend | Low | High | Descend | Medium | Low | |

| Abstinence class (%) | |||||||

| High | 75 | 56 | 30 | 76 | 63 | 56 | 28 |

| Descending | 12 | 15 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 12 | 6 |

| Low | 13 | 29 | 66 | 16 | 30 | 32 | 66 |

| Attendance class (%) | |||||||

| High | 26 | 11 | 3 | ||||

| Descending | 29 | 39 | 8 | ||||

| Medium | 29 | 25 | 8 | ||||

| Low | 16 | 24 | 81 | ||||

We also looked the relationships between sponsor classes and attendance classes. Most individuals in the low sponsor class were also in the low attendance class (81%), and about two-fifths (39%) of the descending sponsor class also were in the descending attendance class. However, the high sponsor class was not dominated by those from the high attendance class, but instead included similar proportions from the high, descending, and medium attendance classes (26%, 29% & 29% respectively).

The relationship between having sponsor and abstinence, controlling for AA attendance

In the block-entry multinomial regression model, fit statistics indicated that sponsorship class has a significant added predictive value above that of attendance class (Chi-Square=35.8, p<.001). Table 4 summarizes the results of the final model with all variables entered simultaneously. Most significant results were found in contrasting the high abstinence (vs. low abstinence) classes. Specifically, individuals in the high attendance, descending attendance and medium attendance classes (vs. low attendance) all had higher odds of being in the high abstinence class (vs. low abstinence; OR’s respectively 3.9, 2.3 & 2.0). Similarly, individuals in the high sponsor and descending sponsor classes (vs. low sponsor) had higher odds of being in the high abstinence class (vs. low abstinence class; OR’s respectively 7.0 & 3.3). Finally, individuals in the high sponsor class (vs. descending sponsor) were at higher odds of being in the high abstinence class (vs. low abstinence; OR=3.3). Fewer differences were found when comparing the descending abstinence and low abstinence classes: those in the high sponsor and the descending sponsor classes (vs. low sponsor) were at higher odds of being in the descending abstinence class (vs. low abstinence; OR’s = 12.0 & 6.3).

Table 4.

Summary of multinomial regression block-entry a results testing the independent influence of meeting attendance class membership and sponsor class membership on abstinence class membership.

| High (vs. low) abstinence | Descending (vs. low) abstinence |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | (se) | OR | p-val | β | (se) | OR | p-val | |

| High (vs. low) attendance | 1.36 | (0.53) | 3.9 | .010 | .23 | (0.84) | 1.3 | .787 |

| Descend. (vs. low) attendance | .85 | (0.32) | 2.3 | .008 | −.17 | (0.59) | 0.9 | .782 |

| Medium (vs. low) attendance | .71 | (0.36) | 2.0 | .035 | .32 | (0.56) | 1.4 | .569 |

| Descend. (vs. high) attendance | −.52 | (0.56) | 0.2 | .360 | −.39 | (0.89) | 0.6 | .662 |

| Medium (vs. high) attendance | −.66 | (0.57) | 0.2 | .250 | .09 | (0.86) | .52 | .918 |

| High (vs. low) sponsor | 1.95 | (0.43) | 7.0 | <.001 | 2.48 | (0.63) | 12.0 | <.001 |

| Descend. (vs. low) sponsor | .68 | (0.34) | 2.0 | .042 | 1.83 | (0.54) | 6.3 | .001 |

| High (vs. descend) sponsor | 1.27 | (0.48) | 3.3 | .009 | .65 | (0.63) | 1.9 | .303 |

| Age | .02 | (0.01) | >1.0 | .041 | .01 | (0.03) | 1.0 | .805 |

| Male (vs. female) | .36 | (0.23) | 1.4 | .113 | .90 | (0.39) | 2.5 | .020 |

| Agnostic/atheist/other vs. religious | −.63 | (0.32) | 0.5 | .047 | −.26 | (0.55) | 0.8 | .639 |

| Spiritual (vs. religious) | .03 | (0.24) | 1.0 | .910 | .03 | (0.43) | 1.0 | .937 |

| Gen. pop. sample (vs. treated) | −1.09 | (0.31) | 0.3 | .001 | −1.03 | (0.67) | 0.4 | .122 |

High and the descending abstinence classes are contrasted to the low abstinence class (see table headings), that is, the low abstinence class was designated as the comparison group (coded 0) in the multinomial regression model. Contrasts between attendance classes within each abstinence contrast are noted in the rows. The same is true for the sponsor contrasts. Reference categories for the attendance and sponsor classes were changed to establish the various contracts displayed above; this has no bearing on p-values nor does it increase Type I errors. β=beta coefficient; se=standard error; OR=odds ratio.

Block-1 (BIC=818; −2 log likelihood=706) and block-2 (BIC= 807; −2 log likelihood=671; Chi-Square=35.8, p<.001).

Like prior AA outcomes research,61 covariates associated with being in the high abstinence class (vs. low) included being older, self-identifying as religious, and being in the treatment sample (i.e., those reporting greater baseline severity): males were more likely to in the descending (vs. low) class. ASI alcohol severity was dropped from the final multivariate model because it added nothing significant.

DISCUSSION

Our trajectories analysis, which statistically compared the direct relationships between attendance class membership and abstinence class membership, is in part an extension of earlier work with these data.50 That work, which also constructed attendance trajectories (similar to ours) simply plotted the mean abstinence rates for each class at each data point rather than constructing abstinence trajectories and then testing relationships. Overall the simpler bivariate point-prevalence estimates looked much like our results generated from a more sophisticated analysis strategy: individuals reporting low attendance at all follow-ups had a lower pattern of abstinence across time than those in the high, descending and medium attendance classes. These results suggest that any pattern of AA attendance, even if it declines over time (supporting hypothesis 1) or is never that high for a particular 12-month period, is better than little or no attendance in terms of abstinence over time.

As for the added value of sponsorship, our results show a benefit for having a sponsor independent of attendance. After controlling for the influence of meeting attendance, being in the high sponsor class still predicted better abstinence outcomes than being in either of the two other sponsor classes (supporting hypothesis 2), and even being in the descending sponsor class carried a benefit above the low sponsor class (supporting hypothesis 3). Taken together, AA involvement is beneficial in facilitating abstinence: importantly, having a sponsor has an added effect above the positive effect of attendance in increasing the odds of maintaining abstinence over time (supporting hypothesis 4). In building classes for attendance, sponsorship, and abstention, we were able to take the earlier trajectories work50 a step forward and empirically test relationships among these variables in a single regression model. It is clear from the odds ratios that as levels of attendance and levels of sponsorship involvement increased, so did the odds of abstinence.

Looking more closely at patterns of AA involvement and abstinence

More than half the individuals who reduced their sponsor involvement and their attendance were in the high abstinence class, signifying that some persons may reduce their AA involvement over time and continue to maintain abstinence. Note that persons in this abstinence class started out high on both our AA measures, suggesting that perhaps initially high doses of AA involvement may sufficiently instill an abstemious lifestyle for some alcohol-dependent persons. To test this conclusion, we conducted post-hoc analyses and found that 82% of those in both the descending attendance and descending sponsor classes reported past 30-day abstinence at the 7-year follow-up. This compares closely to 94% for those in both the high attendance and high sponsor classes who reported abstinence at 7 years. Overall, our attendance results are consistent with the Moos findings wherein those who affiliated with AA quickly and stayed involved longer had better alcohol-related outcomes.47,48

The majority of those with a low abstinence pattern at all follow-ups also reported the lowest pattern of attendance and sponsorship. Still, more than a quarter of these individuals were in the high abstinence class. Because the low attendance and low sponsor classes were the most populated groups (62% and 71% of the sample respectively), this suggests a good number of alcohol-dependent individuals fare well with little or no AA involvement. This lends support to a re-emerging literature suggesting that some dependent persons can stop drinking without specialty treatment or 12-step involvement.71-74 Understanding what differentiates individuals who maintain abstinence without treatment or AA involvement from those who manage better in a structured recovery network of like-minded persons who offer social support, role-modeling, and guidance, is an important area of future longitudinal research.

Limitations

Our conclusions are limited by how the data were collected. Because follow-ups occurred at 1, 3, 5, and 7 years and maximally queried prior 12-month events; we lack data for years 2, 4, and 6. It is possible that the trajectories we constructed would not replicate with contiguous 7-year data collected via timeline follow-back techniques. Consistent with other studies of AA attendance (especially those that use telephone follow-up interviews), we used past 30-day abstinence.51,75,76 One justification for this timeframe is that a more causal relationship can be approximated using past 12-month AA variables to predict past 30-day abstention (with only a one-month overlap). The Kaskutas50 (2009) trajectories paper found similar results obtained when 12-month abstinence was also tested. As well, our sponsorship variable only asked about ‘current’ sponsorship (with interpretation left to the individual) and it did not assess the quality or intensity of the relationship. We acknowledge that there may be advantage to capturing identical timeframes: we know that attendance often ebbs and flows77 (sponsorship may vary too based on need and where one is in their recovery process), so a 30-day window could likely over or under estimate one’s involvement. Also, these data relied on self report and, thus, are open to reporting error. No information was gathered from collaterals to corroborate the drinking data. Lastly, like much prior AA research, our findings on how AA profiles relate to abstention profiles are still more correlational than causal.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest heterogeneity in patterns of AA attendance and sponsorship over time. Understanding how alcohol-dependent persons involve themselves in AA and how this relates to change should help health providers and clients become more effective in setting realistic long-term treatment goals and expectations. This notion is consistent with newer paradigms that are encouraging a model of care focused on long-term recovery management.78,79 Further, though we have evidence supporting twelve-step facilitation practices, AA may not be necessary for everyone, and especially for individuals like some in our low attendance class who appeared to maintain abstinence with little or no AA involvement. More work is needed to understand the mechanisms of change for this group. Last, our findings align with research cited in a recent review, concluding that providers should “encourage participation in AA while avoiding indiscriminant and generalized prescription.”80

Acknowledgments

This manuscript is funded through a grant from National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (P30 AA05595).

REFERENCES

- 1.McLellan AT. Have we evaluated addiction treatment correctly? Implications from a chronic care perspective. Addiction. 2002 March;97(3):249–252. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00127.x. [Editorial] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McLellan AT, Meyers K. Contemporary addiction treatment: a review of systems problems for adults and adolescents. Biological Psychiatry. 2004 November;56(10):764–770. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Emrick CD, Tonigan JS, Montgomery HA, Little L. Alcoholics Anonymous: what is currently known? In: McCrady BS, Miller WR, editors. Research on Alcoholics Anonymous: Opportunities and alternatives. Rutgers Center of Alcohol Studies; New Brunswick, NJ: 1993. pp. 41–78. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tonigan JS, Toscova R, Miller WR. Meta-analysis of the literature on Alcoholics Anonymous: sample and study characteristics moderate findings. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1996 January;57(1):65–72. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Timko C, Billow R, DeBenedetti A. Determinants of 12-step group affiliation and moderators of the affiliation-abstinence relationship. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006 June;83(2):111–121. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelly JF, Stout R, Zywiak WH, Schneider R. A 3-year study of addiction mutual-help group participation following intensive outpatient treatment. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2006;30(8):1381–1392. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Humphreys K, Moos RH. Encouraging posttreatment self-help group involvement to reduce demand for continuing care services: two-year clinical and utilization outcomes. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2007 January;31(1):64–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tonigan JS. Alcoholics Anonymous outcomes and benefits. In: Galanter M, Kaskutas LA, editors. Recent Developments in Alcoholism: Research on Alcoholics Anonymous and spirituality in addiction recovery. Vol 18. Springer; New York: 2008. pp. 357–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donovan DM, Floyd AS. Facilitating involvement in 12-step programs. In: Galanter M, Kaskutas LA, editors. Recent Developments in Alcoholism: Research on Alcoholics Anonymous and Spirituality in Addiction Recovery. Vol 18. Springer; New York: 2008. pp. 303–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Project MATCH Research Group Matching alcoholism treatment to client heterogeneity: Project MATCH posttreatment drinking outcomes. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1997;58(1):7–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Project MATCH Research Group Matching alcoholism treatments to client heterogeneity: project MATCH three-year drinking outcomes. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1998;22(6):1300–1311. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Majer JM, Jason LA, Ferrari JR, Miller SA. 12-Step involvement among a U.S. national sample of Oxford House residents. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.01.010. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelly JF, McCrady BS. Twelve-step facilitation in non-specialty settings. In: Galanter M, Kaskutas LA, editors. Alcoholics Anonymous and Spirituality in Addiction Recovery. Vol 18. Springer; New York: 2008. pp. 321–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Humphreys K, Kaskutas LA, Weisner C. The Alcoholics Anonymous Affiliation Scale: development, reliability, and norms for diverse treated and untreated populations. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1998;22(5):974–978. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaskutas LA, Weisner C, Lee M, Humphreys K. Alcoholics Anonymous affiliation at treatment intake among white and black Americans. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1999 November;60(6):810–816. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cloud RN, Ziegler CH, Blondell RD. What is Alcoholics Anonymous affiliation? Subst. Use Misuse. 2004 June;39(7):1117–1136. doi: 10.1081/ja-120038032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tonigan JS, Connors GJ, Miller WR. The Alcoholics Anonymous Involvement scale (AAI): reliability and norms. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 1996;10(2):75–80. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tonigan JS, Connors GJ, Miller WR. Participation and involvement in Alcoholics Anonymous. In: Babor TF, del Boca FK, editors. Treatment Matching in Alcoholism. Cambridge University Press; New York, NY: 2003. pp. 184–204. [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKay JR, Weiss RV. Review of temporal effects and outcome predictors in substance abuse treatment studies with long-term follow-ups: preliminary results and methodological issues. Eval. Rev. 2001;25(2):113–161. doi: 10.1177/0193841X0102500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moos R, Schaefer J, Andrassy J, Moos B. Outpatient mental health care, self-help groups, and patients’ one-year treatment outcomes. J. Clin. Psychol. 2001;57(3):273–287. doi: 10.1002/jclp.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ouimette PC, Moos RH, Finney JW. Influence of outpatient treatment and 12-step group involvement on one-year substance abuse treatment outcomes. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1998 September;59(5):513–522. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moos RH, Moos BS. Paths of entry into Alcoholics Anonymous: consequences for participation and remission. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2005;29(10):1858–1868. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000183006.76551.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McKay JR, Foltz C, Stephens RC, Leahy PJ, Crowley EM, Kissin W. Predictors of alcohol and crack cocaine use outcomes over a 3-year follow-up in treatment seekers. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2005 March;28(Suppl. 1):S73–S82. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gossop M, Stewart D, Marsden J. Attendence at Narcotics Anonymous and Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, frequency of attendence and substance use outcomes after residential treatment for drug dependence: a 5 year follow-up study. Addiction. 2008 January;103(1):119–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montgomery HA, Miller WR, Tonigan JS. Does Alcoholics Anonymous involvement predict treatment outcome? J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 1995 July-August;12(4):241–246. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(95)00018-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaskutas LA, Ammon LN, Weisner C. A naturalistic analysis comparing outcomes at substance abuse treatment programs with differing philosophies: social and clinical model perspectives. International Journal of Self Help and Self Care. 2004;2(2):111–133. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Connors GJ, Tonigan JS, Miller WR. A longitudinal model of intake symptomatology, AA participation, and outcome: retrospective study of the Project MATCH outpatient and aftercare samples. J. Stud. Alcohol. 2001 November;62(6):817–825. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McKellar J, Stewart E, Humphreys K. Alcoholics Anonymous involvement and positive alcohol-related outcomes: cause, consequence, or just a correlate? A prospective 2-year study of 2,319 alcohol-dependent men. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2003 April;71(2):302–308. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weiss RD, Griffin ML, Gallop RJ, et al. The effect of 12-step self-help group attendance and participation on drug use outcomes among cocaine-dependent patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005 February;77(2):177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Witbrodt J, Delucchi K. Do women differ from men on Alcoholics Anonymous participation and abstinence? A multi-wave analysis of treatment seekers. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01573.x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toumbourou JW, Hamilton M, U’Ren A, Steven-Jones P, Storey G. Narcotics Anonymous participation and changes in substance use and social support. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2002 July;23(1):61–66. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00243-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sheeren M. The relationship between relapse and involvement in Alcoholics Anonymous. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1988 January;49(1):104–106. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1988.49.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Emrick CD. Alcoholics Anonymous: affiliation processes and effectiveness as treatment. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1987 October;11(5):416–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1987.tb01915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pagano ME, Phillips KA, Stout RL, Menard W, Piliavin JA. Impact of helping behaviors on the course of substance-use disorders in individuals with body dysmorphic disorder. J. Stud. Alcohol. 2007 March;68(2):291–295. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Magura S, Laudet AB, Mahmood D, Rosenblum A, Vogel HS, Knight EL. Role of self-help processes in achieving abstinence among dually diagnosed persons. Addict. Behav. 2003 April;28(3):399–413. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00278-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caldwell PE, Cutter HSG. Alcoholics Anonymous affiliation during early recovery. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 1998 May-June;15(3):221–228. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(97)00191-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morgenstern J, Bux DA, Jr., Labouvie E, Morgan T, Blanchard KA, Muench F. Examining mechanisms of action in 12-Step community outpatient treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003 December;72(3):237–247. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Timko C, Debenedetti A. A randomized controlled trial of intensive referral to12-step self-help groups: one-year outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007 October;90(2-3):270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tonigan JS, Rice SL. Is it beneficial to have an Alcoholics Anonymous sponsor? Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2010 September;24(3):397–403. doi: 10.1037/a0019013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Isenhart CE. Pretreatment readiness for change in male alcohol dependent subjects: predictors of one-year follow-up status. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1997 July;58(4):351–357. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Witbrodt J, Kaskutas LA. Does diagnosis matter? Differential effects of 12-step participation and social networks on abstinence. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2005;31(4):685–707. doi: 10.1081/ada-68486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Subbaraman MS, Kaskutas LA, Zemore SE. Sponsorship and service as mediators of the effects of Making Alcoholics Anonymous Easier (MAAEZ), a 12-step facilitation intervention. Drug Alcohol Depend. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.12.008. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cross GM, Morgan CM, Mooney AJ. Alcoholism treatment: a ten-year follow-up study. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1990;14(2):169–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1990.tb00465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pagano ME, Friend KB, Tonigan JS, Stout RL. Helping other alcoholics in Alcoholics Anonymous and drinking outcomes: findings from Project Match. J. Stud. Alcohol. 2004 November;65(6):766–773. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zemore SE, Kaskutas LA. Helping, spirituality, and Alcoholics Anonymous in recovery. J. Stud. Alcohol. 2004;65(3):383–391. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Crape BL, Latkin CA, Laris AS, Knowlton AR. The effects of sponsorship in 12-step treatment of injection drug users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002 February;65(3):291–301. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(01)00175-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moos RH, Moos BS. Participation in treatment and Alcoholics Anonymous: a 16-year follow-up of initially untreated individuals. J. Clin. Psychol. 2006;62(6):735–750. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moos RH, Moos BS. Long-term influence of duration and frequency of participation in Alcoholics Anonymous on individuals with alcohol use disorders. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2004;72(1):81–90. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kaskutas LA, Ammon LN, Delucchi K, Room R, Bond J, Weisner C. Alcoholics Anonymous careers: patterns of AA involvement five years after treatment entry. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2005;29(11):1983–1990. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000187156.88588.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kaskutas LA, Bond J, Avalos L Ammon. 7-year trajectories of Alcoholics Anonymous attendance and associations with treatment. Addict. Behav. 2009 December;34(12):1029–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morgenstern J, Kahler CW, Frey RM, Labouvie E. Modeling therapeutic response to 12-step treatment: optimal responders, nonresponders, and partial responders. J. Subst. Abuse. 1996;8(1):45–59. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(96)90079-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weisner C, Schmidt L. The Community Epidemiology Laboratory: studying alcohol problems in community- and agency-based populations. Addiction. 1995;90(3):329–342. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.9033293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schmidt L. Women and Alcohol Problems: Developing an Agenda for Health Services Research. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Rockville, MD: Nov 4-5, 1998. The impact of welfare reform on alcohol treatment for women. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weisner C, Matzger H. A prospective study of the factors influencing entry to alcohol and drug treatment. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 2002 May;29(2):126–137. doi: 10.1007/BF02287699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kaskutas LA, Russell G, Dinis M. Technical Report on the Alcohol Treatment Utilization Study in Public and Private Sectors. Alcohol Research Group; Berkeley, CA: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Regier DA, Myers JK, Kramer M, et al. The NIMH Epidemiological Catchment Area Program: historical context, major objectives and study population characteristics. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1984 October;41(10):934–941. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1984.01790210016003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Erdman HP, Klein MH, Greist JH, et al. A comparisonof two computer-administered versions of NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1992;26(1):85–95. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(92)90019-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Robins LN, Cuttler L, Keating S. NIMH diagnostic interview schedule. version III, revised. National Institute of Mental Health; Rockville, MD: Sep 4, 1991. 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 59.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-IV-TR. 4th ed American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; Washington, D.C.: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Adamson SJ, Sellman JD, Frampton CMA. Patient predictors of alcohol treatment outcome: a systematic review. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2009 January;36(1):75–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bogenschutz MP. Individual and contextual factors that influence AA affiliation and outcomes. In: Galanter M, Kaskutas LA, editors. Recent Developments in Alcoholism: Research on Alcoholics Anonymous and spirituality in addiction recovery. Vol 18. Springer; New York: 2008. pp. 413–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Connors GJ, Tonigan JS, Miller WR. A measure of religious background and behavior for use in behavior change research. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 1996;10(2):90–96. [Google Scholar]

- 63.McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Cacciola JS, Griffith J. Guide to the addiction severity index: background, administration, and field testing results. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute on Drug Abuse; Rockville, MD: 1985. No. (ADM) 85-1419. [Google Scholar]

- 64.McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, et al. The Fifth Edition of the Addiction Severity Index. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 1992 Summer;9(3):199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McLellan AT. Addiction Severity Index (ASI) In: Rush AJ Jr., Pincus HA, First MB, et al., editors. Handbook of Psychiatric Measures. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2000. pp. 472–474. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mplus. version 5.1. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 2008. [computer program] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. 2nd. ed John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Muthén B, Shedden K. Finite mixture modeling with mixture outcomes using the EM algorithm. Biometrics. 1999 June;55(2):463–469. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jung T, Wickrama KAS. An introduction to latent class growth analysis and growth mixture modeling. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2008 January;2(1):302–317. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nylund KL, Muthén BO, Asparouhov T. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis: a Monte Carol simulation study. Department of Advanced Quantitative Methods, Graduate School of Education and Information Studies, UCLA; Los Angeles, CA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sobell LC, Ellingstad TP, Sobell MB. Natural recovery from alcohol and drug problems: methodological review of the research with suggestions for future directions. Addiction. 2000;95(5):749–764. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.95574911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sobell LC, Cunningham JA, Sobell MB. Recovery from alcohol problems with and without treatment: prevalence in two population surveys. Am. J. Public Health. 1996 July;86(7):966–972. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.7.966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Humphreys K, Moos RH, Finney JW. Two pathways out of problem drinking problems without professional treatment. Addict. Behav. 1995;20(4):427–441. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00005-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cohen E, Feinn R, Arias A, Kranzler HR. Alcohol treatment utilization: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007 January;86(2-3):214–221. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Moos RH, Moos BS. Rates and predictors of relapse after natural and treated remission from alcohol use disorders. Addiction. 2006;101(2):212–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01310.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Weisner C, Ray GT, Mertens J, Satre DD, Moore C. Short-term alcohol and drug treatment outcomes predict long-term outcome. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003 September;71(3):281–294. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00167-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Moos RH, Moos BS. The interplay between help-seeking and alcohol-related outcomes: divergent processes for professional treatment and self-help groups. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004 August;75(2):155–164. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.White WL, Boyle M, Loveland D. Alcoholism/addiction as a chronic disease: from rhetoric to clinical reality. Alcohol. Treat. Quart. 2002 June;20(3&4):107–129. [Google Scholar]

- 79.White WL, Kurtz E, Sanders M, editors. Recovery Management. Great Lakes Addiction Technology Transfer Center (ATTC) Network; Chicago, IL: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cloud RN, Kingree JB. Concerns about dose and underutilization of twelve-step programs: models, scales, and theory that inform treatment planning. In: Galanter M, Kaskutas LA, editors. Recent Developments in Alcoholism: Research on Alcoholics Anonymous and Spirituality in Addiction Recovery. Vol 18. Springer; New York: 2008. pp. 283–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]