Abstract

Background

Understanding of adolescent-onset asthma remains limited. We sought to characterise this state and identify associated factors within a longitudinal birth cohort study.

Methods

The Isle of Wight Whole Population Birth Cohort was recruited in 1989 (N=1456) and characterised at 1, 2, 4, 10 and 18-years. “Adolescent-onset asthma” was defined as asthma at age 18 without prior history of asthma, “persistent-adolescent asthma” as asthma at both 10 and 18 and “never-asthma” as those without asthma at any assessment.

Results

Adolescent-onset asthma accounted for 28.3% of asthma at 18-years and was of similar severity to persistent-adolescent asthma. Adolescent-onset asthmatics showed elevated bronchial hyper-responsiveness (BHR) and atopy at 10 and 18-years. BHR in this group at 10 was intermediate to that of never-asthmatics and persistent-adolescent asthma. By 18 their BHR, bronchodilator reversibility and sputum eosinophilia was greater than never-asthmatics and comparable to persistent-adolescent asthma. At 10, males who later developed adolescent-onset asthma had reduced FEV1 and FEF25–75, while females had normal lung function but then developed impaired FEV1 and FEF25–75 in parallel with adolescent asthma. Factors independently associated with adolescent-onset asthma included atopy at 10 (OR = 2.35; 95% CI = 1.08–5.09), BHR at 10 (3.42; 1.55–7.59), rhinitis at 10 (2.35; 1.11–5.01) and paracetamol use at 18-years (1.10; 1.01–1.19).

Conclusions

Adolescent-onset asthma is associated with significant morbidity. Predisposing factors are atopy, rhinitis and BHR at age 10 while adolescent paracetamol use is also associated with this state. Awareness of potentially modifiable influences may offer avenues for mitigating this disease state.

Keywords: Adolescence, Asthma, Atopy, Bronchial Hyper-responsiveness, Rhinitis, Paracetamol, Lung Function

Introduction

Several longitudinal cohort studies have investigated the natural history of asthma from birth into adulthood. A consensus has arisen from such work that most adult asthma originally develops in childhood 1–3. However, adult asthma is now recognised to be a heterogeneous collection of diverse phenotypes4. In turn, awareness has grown that some adult asthma first appears in adolescence or early adulthood 5. Understanding of adolescent or early adult-onset asthma is still evolving and characterisation of such disease remains incomplete. Associations with female predominance and non-atopic status have been described 6–8. Potentially relevant early life risk factors for adolescent onset asthma are emerging. Pre-existing rhinitis has been implicated as a risk factor for subsequent childhood9, adolescent10 and adult 10–11 wheeze/asthma. Rhinitis is a risk factor for bronchial hyper-responsiveness (BHR). A substantial proportion of children have been demonstrated to have asymptomatic BHR 12. Asymptomatic BHR may be another risk factor for subsequent asthma development 5,13,14 as may lower childhood lung function5.

Adolescence is a period of dynamic physiological changes that may influence development of new-onset asthma. So too might behavioural changes that lead to harmful exposures during adolescence. Thus tobacco smoke 15,16 and other less obvious exposures like paracetamol may be important 17. Here we characterised adolescent-onset asthma in the Isle of Wight Birth Cohort, identifying relevant risk factors for its development.

Methods

An unselected whole population birth cohort (n=1456) was established in 1989 on the Isle of Wight, UK to study the natural history of asthma with subsequent assessment at 1, 2, 4, 10 and 18-years. Methodology for the first decade of follow-up has been published previously 18–20.

The Local Research Ethics Committee (06/Q1701/34) approved follow-up at 18-years. Both study-specific and International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) 21 questionnaires were used to obtain information on disease plus relevant associated factors such as domestic pet exposure, reported passive and personal tobacco exposures, and family history of disease. Details of key questions are provided under Definitions with further important questions listed in the online supplement. Self-rated health status was recorded by Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) from the European Quality of Life 5-Dimensional tool (EQ-5D) 22. Participation was in person, by telephone or by post; the proportions followed through each modality are given in Table 1. Participants attending in person underwent spirometry, fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) measurement, bronchodilator reversibility (BDR) to 600 micrograms inhaled salbutamol, methacholine challenge test and skin prick test (SPT). Identical methods, published previously 20, were used for spirometry and challenge testing at 10- and 18-years. FeNO (Niox mino,® Aerocrine AB, Solna, Sweden) and SPT to common food/aeroallergens (ALK-Abello, Horsholm, Denmark) were performed as reported previously 23. Brief details of testing methodology are provided in the online supplement. At 18-years a subgroup of asthmatics and controls (without asthma) attended separately for sputum induction using a standard protocol 24. If Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 second (FEV1) was ≥ 60% predicted, participants received serial nebulisation of hypertonic saline (4.5%) for 5 minutes at a time to a maximum of 20 minutes. Samples were immediately placed on ice and processed within 2 hours for cytology. Total and differential cell counts were recorded. A 3% eosinophil count cut-off defined significant eosinophilia.

Table 1.

Mode of Participation in 18-year Study Follow-up

| How visit/questionnaire took place |

Overall % (n) * |

Male % (n) * |

Female % (n) * |

p-value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In person | 66(864) | 63(410) | 69(454) | 0.04 |

| By telephone | 32(421) | 35(231) | 29(190) | 0.006 |

| By post | 2(28) | 2(12) | 2(16) | 0.42 |

| Total (N) | 100(1313) | 100(653) | 100(660) | 0.82 |

n = number of participants in each group with (%) = percentage given for each group total represented by N

Chi-square test for difference between males and females with significance at p < 0.05

Definitions

Asthma was defined as “yes” to “have you ever had asthma?” and either of “have you had wheezing in the last 12 months”? or “have you had asthma treatment in the last 12 months?”. “Adolescent-onset asthma” was defined as having asthma at age 18 but no prior history of asthma, “persistent-adolescent asthma” as having asthma at both 10 and 18 with “neverasthma” applied to those not reporting asthma at any study assessment. A small group (N=17) was identified with “recurrence of childhood asthma” who had asthma in the first 4-years of life, not at 10 but had it again at 18-years. Rhinitis was defined by “yes” to “have you ever had a problem with sneezing, runny or blocked nose in the absence of cold or flu?” plus “have you had symptoms in the last 12 months?” Atopy was defined by positive SPT (mean wheal diameter 3mm greater than negative control) to at least one allergen.

Statistical methods

Data were entered onto SPSS (version 17). Categorical variables were assessed by Chi-square tests. For normally distributed continuous measures, independent samples t-tests were applied. For multiple comparisons, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni correction was used. For non-normally distributed data, Mann-Whitney U test and Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA were applied. General Linear Models were used to compare height adjusted lung function differences.

Bronchial hyper-responsiveness (BHR) was determined by methacholine concentration causing a 20% fall in FEV1 from the post-saline value, expressed as PC20 with a positive test defined by PC20< 8 mg/ml. A continuous dose-response slope (DRS) measure of BHR was also estimated by least-square regression of percentage change in FEV1 upon cumulative methacholine dose for each child. The DRS obtained was transformed as Log10 (DRS+10), to satisfy normality and homoscedasticity. Higher values inferred greater BHR.

At 18-years, study participants reported average monthly use of paracetamol and NSAID (non steroidal anti-inflammatory drug) during the past year. Since consumption of these drugs was not normally distributed in our population, data are presented as median values with 25th to 75th centiles.

To identify risk factors for adolescent-onset asthma, univariate risk analysis was performed against non-wheezers. Factors demonstrating trends for univariate significance (p<0.1) were entered en-bloc into logistic regression models to identify independently significant risk factors.

Results

High cohort follow-up was maintained at 10-years (94.3%; 1373/1456) and 18-years (90.2%; 1313). Those attending the Centre for full data collection at 18-years (N=864) did not differ in key characteristics from the overall study population at 18-years, although attendees were significantly more likely to be in fulltime education (Table E1; Online Supplement).

Asthma prevalence rose from 14.7% (201/1368) at 10-years to 17.9% (234/1306) at 18-years. Of asthmatics at 18-years who also had data at 10-yrs, 63.1% (125/198) had persistent-adolescent asthma, 28.3% (56/198) had adolescent-onset asthma and 8.6% (17/198) recurrence of earlier childhood asthma. In terms of incidence, adolescent-onset asthma arose in 9.2% (56/611) of those without asthma at 10-years, with non-significant trends to female predominance (male = 6.9% v female = 11.7%; p = 0.06).

At 18-years, adolescent-onset asthma was comparable to persistent-adolescent asthma in current disease severity and secondary healthcare use (Table 2). However, self-rated health status was significantly greater in adolescent-onset asthmatics (80.27 v 74.37; mean difference = 5.90; p =0.035; where lower scores infer lower health status). Prescription of anti-asthma treatment was also greater in adolescent-onset than persistent-adolescent asthma.

Table 2.

Symptoms, Treatment, Healthcare Utilisation and Quality of Life in Adolescent-onset and Persistent-adolescent Asthma at 18-years

| Symptoms | Adolescent onset asthma % (n/N) |

Persistent asthma % (n/N) |

Odds Ratio |

95% Confidence Interval |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheeze frequency >4 episodes/year | 30 (17/56) | 34 (42/124) | 0.85 | 0.43 – 1.67 | 0.64 |

| Exercise induced wheeze | 64 (36/56) | 77 (96/124) | 0.53 | 0.27 – 1.04 | 0.07 |

| Sleep disturbed by wheeze in past year | 45 (25/56) | 50 (60/120) | 0.81 | 0.43 – 1.52 | 0.51 |

| Sleep disturbed >1 time per week | 13 (7/56) | 17 (20/120) | 0.71 | 0.29 – 1.77 | 0.48 |

| Speech disturbed by asthma in past year | 14 (8/56) | 18 (22/120) | 0.74 | 0.31 – 1.76 | 0.51 |

| Nocturnal cough in past year | 32 (18/56) | 45 (55/123) | 0.59 | 0.30 – 1.13 | 0.11 |

| Current asthma treatment | 80 (45/56) | 66 (79/120) | 2.12 | 1.00 – 4.48 | 0.05 |

| Ever attended A&E with asthma | 11 (5/44) | 17 (14/79) | 0.60 | 0.21 – 1.72 | 0.44 |

| Ever Hospitalised with asthma | 7 (3/44) | 14 (11/79) | 0.45 | 0.13 – 1.61 | 0.38 |

Comparisons in this table were made using Chi-square test, with significance at p <0.05

% (n/N) = percentage, where n= number of participants with condition, N = total number of participants that responded in that group.

A&E = Accident and Emergency or Casualty Department.

Significant differences were observed for height and weight by gender in the 10 to 18-year period. At 10-years, females were heavier than (36 versus 34 kg; p<0.0001), but of comparable height (139 versus 139 cm; p=0.97) to males. By 18-years males were significantly taller (178 versus 165 cm; p <0.001) and heavier (71 versus 65 kg; p<0.001) than females. When differences in height, weight and Body Mass Index were compared between adolescent-onset and never-asthmatics, no significant differences were observed at 10 or 18-years (Table E2; Online Supplement). Since males and females showed differential somatic growth over adolescence, analysis of differences in lung function between adolescent-onset and never-asthmatics at 10 and 18-years were stratified by gender (Table 3a and Table 3b). At 10, male adolescent-onset asthmatics had significantly greater airflow obstruction (lower FEV1, FEF25–75% and FEV1/FVC ratio) than male never-asthmatics (Table 3a). No significant difference between male adolescent-onset and never-asthmatics was seen for gain in lung function from 10 to 18-years. By 18, significant differences in lung function among males had disappeared. Lung function analysis in females (Table 3b) showed no significant difference between adolescent-onset and never-asthmatics at 10-years. Female adolescent-onset asthmatics demonstrated lower gain in FEV1 than never-asthmatics between 10 and 18-years. At 18, female adolescent-onset asthmatics had significantly lower FEV1 and FEF25–75% than female never-asthmatics.

Table 3.

| a: Comparison of Pulmonary Function at age 10 and 18-years between Adolescent-onset and Never-asthmatic Males | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescent onset asthma (n=15) |

Never asthma (n=171) |

β | 95% Confidence Interval |

p-value | |

| Spirometry at 18 years* | |||||

| FEV1 (L) (S.E.) | 4.55 (0.14) | 4.70 (0.04) | − 0.16 | − 0.46 to 0.14 | 0.29 |

| FVC (L) (S.E.) | 5.41 (0.15) | 5.37 (0.05) | 0.04 | − 0.28 to 0.36 | 0.80 |

| FEV1/FVC (S.E.) | 0.84 (0.02) | 0.88 (0.005) | − 0.03 | − 0.002 to 0.001 | 0.07 |

| FEF25–75% (L/s) (S.E.) | 4.69 (0.28) | 5.18 (0.08) | − 0.49 | −1.06 to 0.09 | 0.10 |

| Spirometry at 10 years* | |||||

| FEV1 (L) (S.E.) | 1.97 (0.06) | 2.11 (0.02) | − 0.14 | − 0.26 to − 0.02 | 0.03 |

| FVC (L) (S.E.) | 2.36 (0.06) | 2.39 (0.02) | − 0.03 | − 0.15 to 0.10 | 0.70 |

| FEV1/FVC (S.E.) | 0.83 (1.40) | 0.89 (0.42) | − 0.05 | − 0.08 to − 0.02 | 0.001 |

| FEF25–75% (L/s) (S.E.) | 2.10 (0.14) | 2.49 (0.04) | − 0.40 | − 0.68 to − 0.11 | 0.006 |

| Gain in spirometry from 10 to 18 years* | |||||

| FEV1 (L) (S.E.) | 2.54 (0.12) | 2.60 (0.03) | − 0.51 | − 0.29 to 0.19 | 0.67 |

| FVC (L) (S.E.) | 3.01 (0.13) | 2.98 (0.04) | 0.03 | − 0.23 to 0.30 | 0.81 |

| FEV1/FVC (S.E.) | 0.008 (0.02) | −0.009 (0.005) | 0.02 | − 0.01 to 0.05 | 0.27 |

| FEF25–75% (L/s) (S.E.) | 2.43 (0.21) | 2.69 (0.06) | − 0.26 | − 0.70 to 0.18 | 0.25 |

| b: Comparison of Pulmonary Function at age 10 and 18-years between Adolescent-onset and Never-asthmatic Females | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescent onset asthma (n=19) |

Never asthma (n = 213) |

β | 95% Confidence Interval |

p-value | |

| Spirometry at 18 years* | |||||

| FEV1 (L) (S.E.) | 3.33 (0.09) | 3.53 (0.03) | − 0.20 | − 0.38 to −0.02 | 0.03 |

| FVC (L) (S.E.) | 3.85 (0.10) | 3.99 (0.03) | − 0.014 | − 0.35 to 0.07 | 0.19 |

| FEV1/FVC (S.E.) | 0.86 (0.02) | 0.89 (0.004) | − 0.026 | − 0.06 to 0.005 | 0.10 |

| FEF25–75% (L/s) (S.E.) | 3.69 (0.20) | 4.09 (0.06) | − 0.42 | − 0.82 to − 0.02 | 0.04 |

| Spirometry at 10 years* | |||||

| FEV1 (L) (S.E.) | 1.96 (0.05) | 2.02 (0.01) | − 0.06 | −0.15 to 0.04 | 0.25 |

| FVC (L) (S.E.) | 2.20 (0.05) | 2.25 (0.01) | − 0.05 | − 0.15 to 0.05 | 0.34 |

| FEV1/FVC (S.E.) | 0.89 (1.25) | 0.90 (0.37) | − 0.35 | − 0.02 to 0.02 | 0.79 |

| FEF25–75% (L/s) (S.E.) | 2.41 (0.12) | 2.54 (0.04) | − 0.13 | − 0.38 to 0.12 | 0.30 |

| Gain in spirometry from 10 to 18 years* | |||||

| FEV1 (L) (S.E.) | 1.36 (0.07) | 1.52 (0.02) | 0.16 | − 0.31 to − 0.006 | 0.04 |

| FVC (L) (S.E.) | 1.62 (0.09) | 1.74 (0.03) | 0.13 | − 0.31 to 0.05 | 0.16 |

| FEV1/FVC (S.E.) | − 0.03 (0.02) | − 0.01 (0.01) | 0.02 | − 0.05 to 0.01 | 0.26 |

| FEF25–75% (L/s) (S.E.) | 1.27 (0.16) | 1.55 (0.05) | 0.2 | − 0.61 to 0.05 | 0.10 |

General Linear Model (GLM) for the difference (β) between adolescent-onset asthma to never-asthma group determined at alpha level of p<0.05 with 95% confidence intervals. Estimated marginal means used for determination of height adjusted lung function means.

(n) represents number of participants that provided information.

FEV1 = Forced expiratory volume in first second in litres (L) with standard error (S.E.).

FVC = Forced vital capacity in litres (L) with standard error (S.E.)

FEV1/FVC = ratio of FEV1 to FVC.

FEF25–75% = Forced expiratory flow 25–75% in litres per second (L/s) with standard error (S.E.).

Atopy did not differ significantly between the adolescent-onset and never-asthmatics at 4-years but was significantly higher in adolescent-onset asthmatics at 10 and 18-years (Table 4). Significant allergen sensitivities in this regard were grass (16% v 9%; p=0.02) plus tree pollen (6% v 1%; p = 0.04) at 10-years and house dust mite (49% v 21%; p<0.001), dog (21% v 6%; p =0.001), cat (15% v 7%; p =0.04) and tree pollen (13% v 4%; p =0.02) at 18. BHR was greater in adolescent-onset asthma than never-asthma (p<0.001) at 10 and 18-years (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of Atopy, BHR, BDR and FeNO between Adolescent-onset and Never-asthma

| Adolescent onset asthma |

Never Asthma |

Odds Ratio |

95% Confidence Interval |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atopy at 4 % (n/N) | 19 (9/48) | 13 (67/519) | 1.56 | 0.72 – 3.36 | 0.26 |

| Atopy at 10 % (n/N) | 42 (21/50) | 18 (89/505) | 3.39 | 1.85 – 6.21 | <0.001 |

| Atopy at 18 % (n/N) | 64 (25/39) | 34 (153/452) | 3.49 | 1.76 – 6.91 | <0.001 |

| BHR* at 10 % (n/N) | 52 (22/42) | 20 (65/332) | 4.52 | 2.33 – 8.77 | <0.001 |

| BHR Slope† at 10 (S.E.) | 1.66 (0.08) | 1.34 (0.02) | 5.41 | 2.68 – 10.93 | <0.001 |

| BHR* at 18 % (n/N) | 25 (7/28) | 2 (7/312) | 14.52 | 4.66 – 45.28 | <0.001 |

| BHR Slope at 18† (n) (S.E.) | 1.32 (28) (0.08) | 1.06 (312) (0.01) | 8.48 | 2.84 – 25.27 | <0.001 |

| BDR at 18 ‡ % (n)(S.E.) | 7.80 (35) (1.20) | 4.05 (427) (0.24) | 1.12 | 1.05 – 1.18 | <0.001 |

| Geometric Mean FeNO§ At 18 (n) (S.E.) | 29 (25) (1.15) | 19 (292) (1.05) | 7.37 | 2.08 – 26.12 | <0.002 |

Odds ratio of adolescent onset asthma to never asthma at univariate level determined by logistic regression with significance at p<0.05.

BHR % = Proportion with PC20 less than 8mg/ml (n/N).

BHR Slope = A high value represents increased bronchial reactivity; obtained by log10 (DRS+10) transformation of dose response slope (DRS).

BDR % = Relative percent FEV1 bronchodilator reversibility response following administration of 600 meg of salbutamol.

Geometric mean FeNO value (ppb or parts per billion).

S.E = Standard Error of Mean.

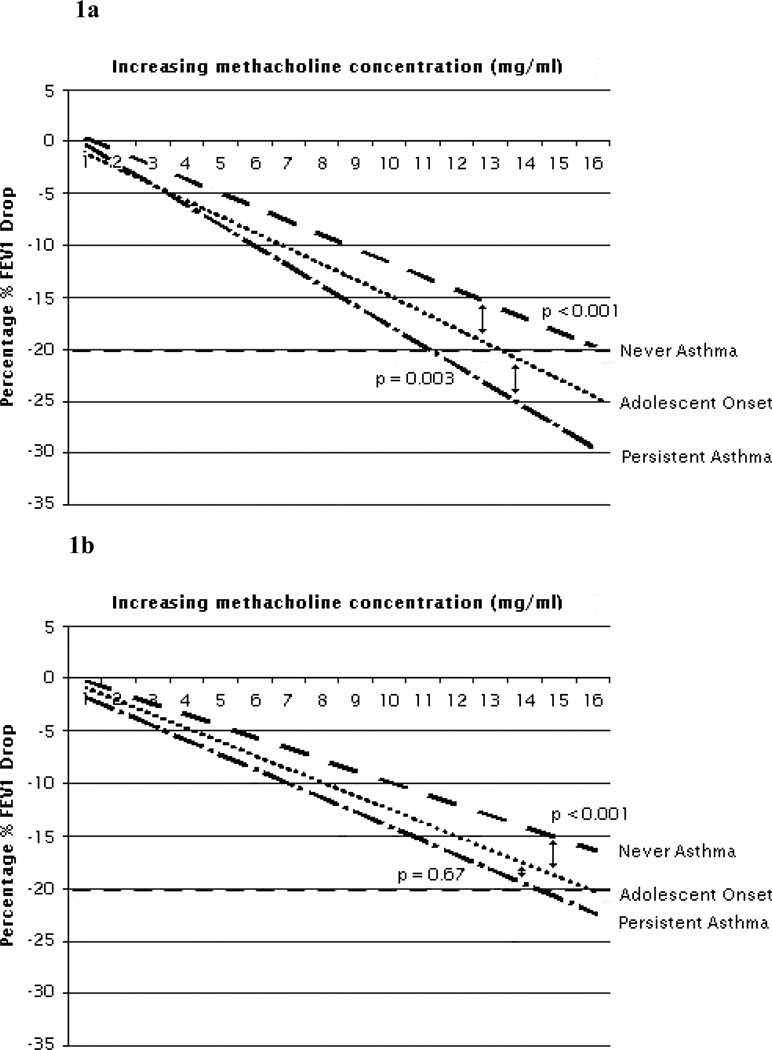

At 10-years, analysis of DRS showed that adolescent-onset asthmatics had intermediate BHR, significantly less than for persistent-adolescent asthma but significantly greater than for never –asthma (Figure 1a). Intermediate BHR DRS was retained at 18-years though by then there was no significant difference in DRS between adolescent-onset and persistent-adolescent asthma (Figure 1b). At 18-years adolescent-onset asthmatics had significantly greater BDR and FeNO than never-asthmatics. Among those undergoing sputum induction, 11 of 12 (92%) adolescent-onset asthmatics were atopic, while only 12 of 30 never-asthmatics were atopic at 18-years (p = 0.002). Adolescent-onset asthmatics had higher sputum eosinophil counts than never-asthmatics and greater prevalence of significant (> 3%) sputum eosinophilia (Table 5).

Figure 1.

a) Bronchial Reactivity (Dose-Response Slope) at 10 Years in Adolescent Asthma Groups

P-values calculated by comparison of Log10 (Dose-Response Slope +10), using ANOVA with post-hoc Bonferroni correction. Never asthma = 331, Adolescent onset = 42, Persistent asthma = 105.

b) Bronchial Reactivity (Dose-Response Slope) at 18 Years in Adolescent Asthma Groups

P-values calculated by comparison of Log10 (Dose-Response Slope +10), using ANOVA with post-hoc Bonferroni correction. Never asthma = 312, Adolescent onset = 28, Persistent asthma = 67.

Table 5.

Sputum characteristics of Adolescent-onset and Never-asthmatics at 18-years

| Induced Sputum | Adolescent onset asthma* (N=12) |

Never asthma (N = 30) |

Odds Ratio |

95% Confidence Interval |

p -value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eosinophils† (%), median (IQR) | 2.4 (5.8) | 0.3 (1.3) | 1.35 | 1.02 – 1.78 | 0.02 |

| Eosinophils > 3% % (n/N) | 50 (6/12) | 13 (4/30) | 6.50 | 1.46 – 29.05 | 0.01 |

| Neutrophils † (%), median (IQR) | 11 (22) | 12 (35) | 0.98 | 0.95 – 1.01 | 0.22 |

| Epithelial cells† (%), median (IQR) | 6 (13) | 4.5 (9) | 1.01 | 0.95 – 1.08 | 0.34 |

Odds ratio of adolescent onset asthma to never asthma at univariate level determined by logistic regression with significance at p<0.05.

Median values of percent cells reported for eosinophil, neutrophil and epithelial cells with (IQR) inter-quartile range.

Univariate analysis of potential associated factors (Table E3; Online data supplement) identified atopy at 10 and 18-years, rhinitis at 10 and 18-years, BHR at 10 and 18-years, maternal history of asthma, and paracetamol use at 18 as having significant association with adolescent-onset asthma. A backward stepwise multiple logistic regression model created using all factors with univariate trends for significance (p<0.1) found independently significant association for adolescent-onset asthma with atopy, rhinitis and BHR at age 10-years plus paracetamol consumption at 18 (Table 6).

Table 6.

Multivariate Analysis of Factors Associated with Adolescent Onset Asthma

| Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence | Interval | p - value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paracetamol at 18 | 1.10 | 1.01 | 1.19 | 0.027 |

| Atopic at 10 year | 2.35 | 1.08 | 5.09 | 0.031 |

| Rhinitis at 10 year | 2.35 | 1.11 | 5.01 | 0.027 |

| Bronchial reactivity at 10 | 3.42 | 1.55 | 7.59 | 0.002 |

Odds ratio for adolescent onset asthma to never asthma determined by backward stepwise multivariate logistic regression with significance at p<0.05. All factors showing univariate trends for significance (p<0.1) were included in the regression model along with gender. The factors included in the model were; gender, atopy at 10, rhinitis at 10, maternal asthma, social class I-III at birth, paracetamol use at 18, and proportion with BHR at 10.

Discussion

Adolescent-onset asthma developed in 9% of those without asthma at 10-years. It constituted over 25% of asthma at 18-years when it showed similar phenotypic characteristics, disease severity and morbidity to persistent-adolescent asthma that commenced in the first decade of life. Atopy, rhinitis and presence of BHR at 10-years predicted subsequent development of adolescent-onset asthma. Among the environmental factors, only paracetamol use at age 18-years showed independently significant association with adolescent-onset asthma.

The early-adult newly diagnosed asthma characterised in the Tucson cohort5 bears some similarity to the adolescent-onset asthma identified in the present study. Our prevalence of adolescent-onset asthma (28%) is comparable to that of early-adult newly diagnosed asthma in the Tucson cohort (27%). However, they found a significant female predominance (71%) for incident asthma in early adulthood. That is consistent with significant female predominance of new-onset adolescent asthma in studies from New Zealand 6, Norway 7, and Germany 8. Recent findings from the Netherlands 25, while showing no significant gender difference in asthma prevalence at 16 years, showed greater adolescent incident asthma and less adolescent asthma remission in females. Although we found higher female prevalence of adolescent-onset asthma (60.7%), that did not reach statistical significance. Another notable distinction is that we found significant association of adolescent-onset asthma with atopy at 10 and 18-years whereas prior studies 6–8 mainly identified a non-atopic state.

We recently reported a considerable rise in rhinitis prevalence over adolescence (from 22.6% at 10-years to 35.8% at 18-years) in our cohort with predominant incident atopic rhinitis in males and non-atopic rhinitis in females during this period 26. Rhinitis at 10-years emerged as independently significant for adolescent-onset asthma in the present study. Prior studies have highlighted rhinitis as a risk factor for subsequent wheeze/asthma. Rochat 9 reported a Relative Risk [RR] of 3.82 for preschool rhinitis with regard to developing wheeze between 5–13-years while Burgess10 found that childhood rhinitis increased adolescent asthma risk 4-fold and that of adult asthma 2-fold. These relationships have been demonstrated in adult populations too. Shaaban 11 reported RR of 3.53 for adult rhinitis in relation to later asthma. Rhinitis has also been identified as a risk factor for subsequent BHR27. Such results support the “one airway, one disease” concept linking upper and lower airways diseases 28.

We previously reported 12 substantial asymptomatic BHR at 10-years, which we now show is a significant risk factor for adolescent-onset asthma. While BHR declined across all groupings during adolescence in our study, the BHR dose-response slope for adolescent-onset asthmatics shifted during adolescence towards the greater levels of persistent-adolescent asthmatics. Asymptomatic BHR has been linked to enhanced airway inflammation and remodelling13, accelerated decline in FEV1 14 and subsequent asthma29. Laprise 13 demonstrated that airway changes in subjects with asymptomatic BHR became more exaggerated once symptoms develop. We found significant sputum eosinophilia and raised FeNO in our adolescent-onset asthmatics at 18-years, indicating that symptoms, BHR and airway inflammation go hand in hand in this group. Stern et al 5 demonstrated associations in the Tucson cohort between newly diagnosed adult asthma at 22-years and BHR/impaired lung function at 6-years. We found that at 10-years, male adolescent-onset asthmatics had evidence of impaired lung function while pre-symptomatic. This may reflect more pronounced effects of subclinical disease on lung function in males at that age on account of naturally smaller relative airway calibre in preadolescent males who have yet to enter their growth spurt. By contrast, we detected reduced lung function in female (but not male) adolescent-onset asthmatics at 18-years. These findings need to be interpreted with caution given the small sample sizes involved. However, if replicated elsewhere, the cause of such gender differences are worthy of speculation. Females have a shorter period of adolescent growth that stops at menarche while male growth continues longer30. Thus, continuing adolescent male growth might allow male lung function to “outpace” effects of disease. Female lung function could be more vulnerable to impairment by adolescent-onset asthma as they attain maximal growth earlier and their lung function cannot “escape” the impact of ongoing disease.

The only adolescent factor significantly associated with adolescent-onset asthma was paracetamol use at 18. The role of paracetamol as a risk factor for asthma via enhanced oxidative airway damage is gaining increasing scrutiny 17, 31. However it is worth noting that we did not detect any association of other potent oxidative effects such as tobacco smoke with adolescent-onset asthma which may cast doubt over that mechanism as an explanation for any relationship with paracetamol. We did not adopt categorical cut-offs to define paracetamol consumption as there is no clear evidence of clinically relevant cut-offs in that context. A limitation of our study is lack of precise data on dosage and indication for use of paracetamol. Therefore these findings should be viewed as demonstrating an association rather than causative relationship. Confounding by indication cannot be excluded and reverse causation remains a potential explanation of our reported association of paracetamol exposure with adolescent-onset asthma.

We did not identify evidence of early-life environment predisposing to adolescent-onset asthma. By contrast tobacco exposures, in early life and adolescence, have previously been implicated as risk factors for incident airways disease 15,16,32. However smoking-related incident disease may reflect various wheezing phenotypes not all of which receive an asthma diagnosis. We also did not find associations between adolescent-onset asthma and other previously frequently reported asthma risk factors such as family history of asthma/allergy. This may reflect that heredity is more significant for some asthma phenotypes than others.

Our study has several strengths. The prospective nature of our work enables better accuracy in assessing temporal relationships and risk factors. Recall bias maybe problematic in longitudinal studies of disease development. However, the high rate of cohort follow-up strengthens the reliability of our findings. We used standardised study materials including ISAAC questionnaires, validated in diverse populations, to ensure comparability with other populations. Although asthma definitions were based on questionnaire responses, we further obtained a range of objective measurements including SPT, spirometry, BDR, FeNO, induced sputum and BHR to validate those. We defined adolescent-onset asthma as that absent at 10-years but present at 18-years. One potential concern is whether this overestimated adolescent-onset asthma by including asthma that had existed in earlier childhood but wasn’t present at age 10. To counter this we excluded 17 cases of recurrent childhood asthma in adolescence. The remaining 56 cases of adolescent-onset asthma had no evidence of earlier childhood asthma from prospectively collected data. We did not exclude 17 cases with isolated episodes of wheezing in the first few years of life, as early life wheezing may not represent asthma. It is impossible to exclude a few cases of disease recurrence amongst incident asthma in our study, though as cited by the Tucson group in a similar study 5 we can be confident that all our incident asthma cases represent first expression of disease severe enough to obtain an asthma diagnosis. Another potential limitation of our study is the fact that few subjects had “complete” data that included all supporting objective tests. Against that criticism though, subjects on which major conclusions are based, all had “core” questionnaire data.

An important implication of our characterisation of adolescent-onset asthma is that we identified potentially modifiable risk factors, present at a pre-symptomatic stage. Treatment of childhood rhinitis, with anti-inflammatory drugs or allergen specific immunotherapy might offer an avenue to reduce adolescent-onset asthma. Evidence to support that notion is limited but one observational study27 noted remission of asymptomatic BHR when rhinitis was treated with nasal steroids. Immunotherapy has been shown to reduce asthma in children with allergic rhinitis33 and may prove beneficial in reducing adolescent-onset asthma risk in such children.

In conclusion, adolescent-onset asthma is associated with pre-existing atopy, rhinitis and asymptomatic BHR plus adolescent behaviour such as paracetamol use. Awareness of potentially modifiable influences may reduce the impact of this disease state and should stimulate future work.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the cooperation of the children and parents who have participated in this study. We also thank Brian Yuen, Professor Wilfried Karmaus, Hongmei Zhang, Roger Twiselton, Monica Fenn, Linda Terry, Stephen Potter and Rosemary Lisseter for their considerable assistance with many aspects of the 18-year follow-up of this study. Finally we would like to highlight the role of the late Dr David Hide in starting this study.

Funding:

The 18-year follow-up of this study was funded by the National Institutes of Health USA

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Online Data Supplement:

This article has an online data supplement (Appendix I).

Contributors:

RJK contributed to study design, conduct, data analysis, and manuscript preparation.

AR contributed to study conduct, data analysis, and manuscript preparation.

MS contributed to study conduct and manuscript preparation.

PW contributed to study conduct and manuscript preparation.

SE contributed to study design and manuscript preparation.

SM contributed to study conduct and manuscript preparation.

GR contributed to study design, data analysis, and manuscript preparation.

SHA contributed to study design, data analysis, manuscript preparation and acts as guarantor for the study.

All authors had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Competing Interest Declaration

“All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coidisclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare that (1) RJK, AR, MS, PW, SE, SM GR, and SHA have no support from any company for the submitted work; (2) RJK, AR, MS, PW, SE, SM GR, and SHA have no relationship to any company that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; (3) their spouses, partners, or children have no specified financial relationships that may be relevant to the submitted work; and (4) RJK, AR, MS, PW, SE, SM GR, and SHA have no non-financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work”.

Contributor Information

Ramesh J Kurukulaaratchy, Email: Ramesh.Kurukulaaratchy@suht.swest.nhs.uk.

Abid Raza, Email: abidraz@yahoo.com.

Martha Scott, Email: marthasvin@hotmail.com.

Paula Williams, Email: paula.williams@iow.nhs.uk.

Susan Ewart, Email: ewart@cvm.msu.edu.

Sharon Matthews, Email: sharon.matthews@iow.nhs.uk.

Graham Roberts, Email: g.c.roberts@soton.ac.uk.

S Hasan Arshad, Email: sha@soton.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Sears MR, Greene JM, Willan AR, et al. A longitudinal, population-based, cohort study of childhood asthma followed to adulthood. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(15):1414–1422. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Phelan PD, Robertson CF, Olinsky A. The Melbourne Asthma Study 1964–1999. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:189–194. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.120951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morgan WJ, Stern DA, Sherrill DL, et al. Outcomes of asthma and wheezing in the first 6-years of life. Follow-up through adolescence. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:1253–1258. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200504-525OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haldar P, Pavord ID, Shaw DE, et al. Cluster analysis and clinical asthma phenotypes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178(3):218–224. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200711-1754OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stern DA, Morgan WJ, Halonen M, Wright AL, Martinez FD. Wheezing and bronchial hyper-responsiveness in early childhood as predictors of newly diagnosed asthma in early adulthood: a longitudinal birth-cohort study. Lancet. 2008;372:1058–1064. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61447-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mandhane PJ, Greene JM, Cowan JO, Taylor R, Sears MR. Sex differences in factors associated with childhood- and adolescent-onset wheeze. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:45–54. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200412-1738OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tollefsen E, Langhammer A, Romundstad P, Bjermer L, Johnsen R, Holmen TL. Female gender is associated with higher incidence and more stable respiratory symptoms during adolescence. Respiratory Med. 2007;101:896–902. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nicolai T, Pereszlenyiova-Bliznakova L, Illi S, Reinhardt D, von Mutius E. Longitudinal follow-up of the changing gender ratio in asthma from childhood to adulthood: role of delayed manifestation in girls. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2003;14:280–283. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3038.2003.00047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rochat MK, Illi S, Ege MJ, et al. the Multicentre Allergy Study (MAS) group. Allergic rhinitis as a predictor for wheezing onset in school-aged children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:1170–1175. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burgess JA, Walters EH, Byrnes GB, et al. Childhood allergic rhinitis predicts asthma incidence and persistence to middle age: a longitudinal study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:863–869. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaaban R, Zureik M, Soussan D, et al. Rhinitis and onset of asthma: a longitudinal population-based study. Lancet. 2008;372:1049–1057. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61446-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurukulaaratchy RJ, Arshad SH, Matthews S, Waterhouse LM. Factors influencing symptom expression in children with bronchial hyper-responsiveness at 10-years. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112(2):311–316. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laprise C, Laviolette M, Boutet M, Boulet LP. Asymptomatic airway hyperresponsiveness: relationships with airway inflammation and remodelling. Eur Respir J. 1999;14:63–73. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14a12.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brutsche MH, Downs SH, Schindler C for the SAPALDIA Team. Bronchial hyperresponsiveness and the development of asthma and COPD in asymptomatic individuals: SAPALDIA cohort study. Thorax. 2006;61:671–677. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.052241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Genuneit J, Weinmayr G, Radon K, et al. Smoking and the incidence of asthma during adolescence: results of a large cohort study in Germany. Thorax. 2006;61:572–578. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.051227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Svanes C, Sunyer J, Plana E, Dharmage S, et al. Early life origins of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2010;65:14–20. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.112136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beasley RW, Clayton TO, Crane J, et al. ISAAC Phase Three Study Group. Acetaminophen use and risk of asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis and eczema in adolescents: International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood: Phase. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(2):171–178. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201005-0757OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arshad SH, Hide DW. Effect of environmental factors on the development of allergic disorders in infancy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1992 Aug;90(2):235–241. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(92)90077-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tariq SM, Matthews SM, Hakim EA, Stevens M, Arshad SH, Hide DW. The prevalence of and risk factors for atopy in early childhood: a whole population birth cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;101:587–593. doi: 10.1016/S0091-6749(98)70164-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurukulaaratchy RJ, Fenn M, Twiselton R, Matthews S, Arshad SH. The prevalence of asthma and wheezing illnesses amongst 10-year-old schoolchildren. Respir Med. 2002 Mar;96(3):163–169. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2001.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asher MI, Keil U, Anderson HR, et al. International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC): rationale and methods. Eur Respir J. 1995 Mar;8(3):483–491. doi: 10.1183/09031936.95.08030483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.EuroQol--a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. The EuroQol Group. Health Policy. 1990 Dec;16(3):199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scott M, Raza A, Karmaus W, et al. Influence of atopy and asthma on exhaled nitric oxide in an unselected birth cohort. Thorax. 2010;65:258–262. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.125443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paggiaro PL, Chanez P, Holz O, et al. Sputum induction. Eur Respir J Suppl. 2002 Sep;37:3s–8s. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00000302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vink NM, Postma DS, Schouten JP, Rosmalen JGM, Boezen HM. Gender differences in asthma development and remission during transition through puberty: The TRacking Adolescents’ Individual Lives Survey (TRAILS) study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:498–504. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kurukulaaratchy RJ, Karmaus W, Raza A, Matthews S, Roberts G, Arshad SH. The influence of gender and atopy on the natural history of rhinitis in the first 18 years of life. Clin Exp Allergy. 2011 Jun;41(6):851–859. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaaban R, Zureik M, Soussan D, et al. Allergic rhinitis and onset of bronchial hyperresponsiveness. A population based study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:659–666. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200703-427OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Demoly P, Bousquet J. The Relationship between asthma and allergic rhinitis. Lancet. 2006;368(9357):711–713. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69263-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rasmussen F, Taylor DR, Flannery EM, et al. Outcome in adulthood of asymptomatic airway hyperresponsiveness in childhood: a longitudinal population study. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2002;34:164–171. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neve V, Girard F, Flahault A, Boule M. Lung and thorax development during adolescence: relationship with pubertal status. Eur Respir J. 2002;20:1292–1298. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00208102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Etminan M, Sadatsafavi M, Jafari S, Doyle-Waters M, Aminzadeh K, Fitzgerald JM. Acetaminophen use and the risk of asthma in children and adults: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Chest. 2009;136:1316–1323. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Butland BK, Strachan DP. Asthma onset and relapse in adult life: the British 1958 birth cohort study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;98:337–343. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60879-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Passalacqua G, Durham SR in cooperation with the Global Allergy and Asthma European Network (GA2LEN) Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma update: Allergen immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:881–891. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.