Abstract

Few of the limited randomized controlled trails (RCTs) for adolescent anorexia nervosa (AN) have explored the effects of moderators and mediators on outcome. This study aimed to identify treatment moderators and mediators of remission at end of treatment (EOT) and 6- and 12-month follow-up (FU) for adolescents with AN (N=121) who participated in a multi-center RCT of family-based treatment (FBT) and individual adolescent focused therapy (AFT). Mixed effects modeling were utilized and included all available outcome data at all time points. Remission was defined as ≥95% IBW plus within 1SD of the Eating Disorder Examination (EDE) norms. Eating related obsessionality (Yale-Brown-Cornell Eating Disorder Total Scale) and eating disorder specific psychopathology (EDE-Global) emerged as moderators at EOT. Subjects with higher baseline scores on these measures benefited more from FBT than AFT. AN type emerged as a moderator at FU with binge-eating/purging type responding less well than restricting type. No mediators of treatment outcome were identified. Prior hospitalization, older age and duration of illness were identified as non-specific predictors of outcome. Taken together, these results indicate that patients with more severe eating related psychopathology have better outcomes in a behaviorally targeted family treatment (FBT) than an individually focused approach (AFT).

INTRODUCTION

There are six published randomized clinical trials (RCTs) examining treatments for adolescent anorexia nervosa (AN); however, few of these have examined the effects of moderators and mediators on outcome. In the most recent published RCT for this patient population, the relative efficacy of family-based treatment (FBT) was compared to individual adolescent focused therapy (AFT) (Lock, Le Grange, Agras, Moye, Bryson & Jo, 2010). In this RCT, adolescents with AN were randomly assigned to receive FBT or AFT over a 12-month treatment period and assessed at the end of treatment (EOT) and at 6-months and 12-months after treatment was completed. This study demonstrated that FBT was superior to AFT in terms of weight change, as assessed using body mass index (BMI) percentile (Hebebrand, Himmelman, Hesecker, Schaefer & Remschmidt, 1996) and change on the Eating Disorder Examination (EDE) (Cooper, Cooper & Fairburn, 1989), at EOT. FBT was also superior to AFT in terms of full remission rates at 6 and 12-month follow-up.

While RCTs provide an evaluation of the relative efficacy of treatments, clinical practice can be informed and our understanding of how treatments work can be enhanced by an examination of predictors/moderators and mediators of outcome (Kraemer, Wilson, Fairburn & Agras, 2002). Non-specific predictors are fixed (e.g., sex) or variable factors (e.g., weight) that precede treatment outcome, are unrelated to the treatment received, and have a main effect on outcome (i.e., a non-specific predictor has the same effect on the outcome regardless of the treatment status). Moderators are fixed or variable pre-randomization characteristics that modify the effect of treatment on outcome (i.e., interaction effect) and identify for whom treatments may work (i.e., a moderator has a different effect on the outcome depending on the treatment status). Mediators of outcome are variables that act after treatment has begun but before treatment changes occur and indicate the mechanisms through which a treatment might achieve its aims (Kraemer, Frank & Kupfer, 2006; Kraemer, Kierman, Essex & Kupfer, 2008; Kraemer, Wilson, Fairburn & Agras, 2002; Wilson, Fairburn, Agras, Walsh & Kraemer, 2002). When moderators are identified, different factors may mediate treatment outcome in subgroups defined by the moderators. Identifying moderators and mediators serves a dual purpose because it informs clinical practice, that is, which treatment is best for which patient, whereas mediators may suggest ways to enhance the effectiveness of treatments.

Not surprisingly, given the few RCTs that have examined treatment for adolescent AN, data about moderators and mediators of treatment outcome are exceedingly limited. In the only RCT to embark on a preliminary exploration of moderators of treatment outcome for this patient population, receiving either short or long term FBT (Lock, Agras, Bryson & Kraemer, 2005), two possible moderators were observed. For weight change, patients with high levels of eating related obsessionality, using the Yale-Brown-Cornell-Eating Disorder Scales (YBC-ED) (Mazure, Halmi, Sunday, Romano & Einhorn, 1994), did significantly better with a longer rather than a shorter course of FBT. Similarly, non-intact families (single parent, divorced) did better with longer treatment in terms of improvements in eating disorder specific psychopathology as measured by the EDE (Cooper et al., 1989). Exploring predictors of dropout and remission, the same group (Lock, Couturier, Bryson & Agras, 2006) found co-morbid psychiatric disorder and longer treatment to predict dropout, while co-morbid psychiatric disorder, being older, and problematic family behaviors were associated with lower rates of remission.

Earlier studies imply that parental criticism, as measured by Expressed Emotion (EE), may play a role in moderating treatment outcome (Eisler, Dare, Hodes, Russell, Dodge & Le Grange, 2000; Le Grange, Eisler, Dare & Russell, 1992). Families with higher levels of parental criticism toward the affected offspring did better in separated FBT (patient and parents seen separately) than in conjoint FBT. Moreover, it has been shown that high levels of parental criticism is a predictor of dropout in FBT (Szmukler, Eisler, Russell & Dare, 1985), while more recently it is argued that parental warmth may be associated with good treatment outcome in FBT (Le Grange, Reinecke-Hoste, Lock & Bryson, 2011).

An examination of treatment response in the broader eating disorder literature is equally limited and has yielded inconsistent findings. While outcome predictors for cognitive behavioral treatment for adults with bulimia nervosa (BN) have been examined (Agras, Crow, Halmi, Mitchell, Wilson & Kraemer, 2000; Fairburn, Agras, Walsh, Wilson & Stice, 2004), only one study explored moderators and mediators of outcome in FBT for adolescents with BN (Le Grange, Crosby & Lock, 2008; Lock, Le Grange & Crosby, 2008). Contrary to the examination of FBT for adolescent AN, participants with less severe eating disorder psychopathology (EDE global score), receiving FBT for BN, were more likely than those receiving individual supportive psychotherapy to be partially remitted at follow-up.

In the present study we examine moderators, mediators and predictors of remission for participants in the RCT of FBT vs. AFT that was described above. Based on prior findings in the adolescent AN literature we advanced two hypotheses at the exploratory level. First, patients with high levels of eating related obsessionality, as measured by the YBC-ED, will have better outcomes in FBT rather than AFT. Second, families with higher levels of parental criticism, as measured by EE, will fare better in AFT as opposed to FBT. For the remainder though, we chose to investigate several variables as possible moderators and the procedure was therefore an exploratory analysis and findings should be regarded as hypothesis generating.

METHOD

Design

This two-site study (The University of Chicago and Stanford University) describes a RCT to explore moderators, mediators and predictors of outcome. The main outcome findings comparing FBT with AFT for adolescents with AN were published elsewhere (Lock, Le Grange, Agras, et al., 2010). Randomization was performed separately for each site by a biostatistician in the Data Coordinating Center (DCC) at Stanford University. One-hundred twenty-one participants were randomly assigned to either FBT (n=61) or AFT (n=60). After a complete description of the study to the participants and their parents was provided, written informed consent was obtained. The Institutional Review Boards of the two clinical sites approved this study.

Recruitment for this RCT occurred from October 2004 through March 2007. Participants were 12 – 18 years of age and eligible if they met DSM-IV criteria for AN (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), including binge eating/purging type, but excluding the amenorrhea criterion (Bravender, Bryant-Waugh, Herzog, et al., 2007), lived with parents or legal guardians, and were medically stable for outpatient treatment (Golden, Katzman, Kreipe, et al., 2003). Participants were weight eligible if between 75–85% of Ideal Body Weight (IBW), with IBW defined as 50th percentile weight for height calculated using Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) weight charts (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2002). Adolescents prescribed a stable dose of antidepressant or anxiolytic medications for a period of two months, and otherwise eligible for randomization, were allowed to enter the study. Participants were excluded from randomization if they presented with a current psychotic disorder, dependent on drugs or alcohol, had a physical condition known to influence eating or weight (e.g. diabetes mellitus, pregnancy), or had previous FBT or AFT. Sixty-nine percent (N=121) of eligible participants (N=175) were randomized.

Treatments

The two manualized treatments and their implementation are described in detail elsewhere (Fitzpatrick, Moye, Hoste, Le Grange & Lock, 2010; Lock, Le Grange, Agras & Dare, 2001). Briefly, Family-Based Treatment (FBT) focuses on encouraging parental control of eating related behaviors in their child and is conducted over three phases. In the first phase, therapy is characterized by attempts to absolve the parents from the responsibility of causing the disorder. Consequently, the therapist will compliment the parents on the positive aspects of their parenting. Parents are encouraged to take steps that will work for their family to help restore the weight of their child with AN thereby improving their sense of efficacy in this arena. In Phase 2, the therapist will support the parents to transition eating and weight control back to the adolescent in an age appropriate manner. The third phase focuses on establishing a healthy adolescent relationship with the parents where the eating disorder is not the idiom of communication. Twenty-four one-hour sessions were provided over the one-year period.

Adolescent-Focused Therapy (AFT) is individually based and focuses on ameliorating eating symptoms in the context of examining common themes in adolescent development. It was originally described by Robin and colleagues (1999) as Ego-Oriented Individual Therapy and posits that individuals with AN manifest ego deficits and confuse self-control with biological needs. Patients learn to identify their emotions, and later with increased self-efficacy, learn to tolerate affective states rather than numbing themselves with starvation. AFT also progresses through three phases. In Phase 1, the therapist establishes rapport, assesses motivation and formulates the patient’s psychological concerns. The therapist actively encourages the patient to refrain from dieting by setting clear goals for weight gain. The importance of weight gain is discussed and actively encouraged throughout treatment until the patient is weight restored. The therapist interprets behavior, emotions, and motives, and helps the patient distinguishes emotional states from bodily needs. In addition, the therapist supports the patient to accept responsibility for food related issues as opposed to relinquishing authority to others (e.g. parents). Phase 2 focuses on encouraging separation and individuation and increasing the ability to tolerate negative affect. Phase 3 focuses on termination of treatment.

AFT sessions were 45 minutes in duration for a total of 32 sessions over the treatment year (24 contact hours). Collateral meetings were held with parents to assess their functioning, advocate for the patient’s developmental needs, and update parents on treatment progress. Up to eight sessions were used for this purpose.

Assessments

Independent assessors not involved in treatment delivery conducted all assessments. Seventeen baseline variables, all thought to be key clinically markers, were examined as moderators of treatment effect on outcome: 1) baseline weight (percentile BMI using CDC norms for age and gender) (CDC, 2002); 2) eating disorder psychopathology (EDE-Global score) (Cooper et al., 1989); 3) prior hospitalization for an eating disorder; 4) obsessive compulsive features of eating symptoms and behaviors (YBC-ED) (Mazure et al., 1994); 5) self-esteem (Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale: RSES) (Rosenberg, 1979); 6) self-efficacy (General Self-Efficacy Scale: GSES) (Sukmak, Sirisoonthon & Meena, 2001); 7) use of psychiatric medications; 8) gender; 9) duration of AN; 10) AN type (restricting or binge-eating/purging); 11) co-morbid psychiatric disorder (Schedule for Affective Disorder and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children: K-SADS) (Kaufman, Birmhaher, Brent et al., 1997); 12) depressive symptoms (Beck Depression Inventory: BDI) (Beck, Steer & Brown, 1996); 13) functional status (Work and Social Adjustment Scale: WSAS) (Mundt, Shear & Greist, 2002); 14) family status (2 parent intact family of origin or not); 15) parental education level (years of education); 16) expressed emotion (Standardized Clinical Family Interview: SCFI) (Kinston & Loader, 1984); and 17) parental self-efficacy (Parents versus Anorexia Scale: PVAS) (Rhodes, Baillie, Brown & Madden, 2005).

Six potential mediators of treatment effect on outcome were examined using change scores from baseline to 4 weeks after treatment started for the following variables: 1) change in weight (percentile BMI using CDC norms for age and gender) (CDC, 2002); 2) self-esteem (RSES) (Rosenberg, 1979); 3) depressive symptoms (BDI) (Beck et al., 1996); 4) self-efficacy (GSES) (Sukmak et al., 2001); 5) restraint over eating (EDE restraint subscale) (Cooper et al., 1989); and 6) parental self-efficacy (PVAS) (Rhodes et al., 2005).

Treatment outcome

In line with the main outcome report (Lock et al., 2010), we used full remission (defined a priori as the percent of patients achieving a threshold comprised of a minimum IBW of 95% and an EDE-Global score within one standard deviation of published norms) as the dichotomous (categorical) variable for statistical analyses. Specifically, we examined moderators and mediators of treatment effect (FBT vs. AFT) on our primary outcome, i.e., the change (slope) in full remission status from baseline to EOT. Since no participant was fully remitted at baseline, this change would be simply remission status at EOT. We also examined moderators and mediators of treatment effect on change in remission status during the maintenance period (from EOT through 6-month to 12-month follow-up) as secondary analyses.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analysis for this study was performed by the DCC at Stanford University. For consistency with our main report, we used mixed effects modeling (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) with remission status (yes/no) at EOT and the follow-up time points as repeatedly measured outcome. The two key dependent variables in each mixed effects model are i) remission status at EOT, and ii) the change (slope) in remission status during the maintenance period (EOT to 12-month follow-up). We incorporated the MacArthur framework for moderator/mediator analysis (Kraemer et al., 2002; Kraemer et al., 2008) in this longitudinal modeling framework to effectively assess moderator and mediator effects utilizing longitudinal outcome information. Each possible moderator was tested separately using the nominal 5% significance level. As this is an exploratory study, p-values should not be interpreted as would in a hypothesis-testing study. Instead, significant findings we present here should be taken only as guidelines for further attention. After moderators were identified, each possible mediator was tested separately in the moderator subgroups (dichotomized at the median unless moderators were categorical variables). In the analysis used to detect moderators, mediators and non-specific predictors were characterized by continuous measures where possible in order to maximize the power to detect these associations. Dichotomization was done post hoc only to provide a quantitative sense of the effects of the moderator detected.

The mixed effects analyses were conducted including all available data in the sample treating remission status (0 = no; 1 = yes) at three assessment points as binary repeated measures. The baseline (pre-randomization) measure was not included in the analysis since it contains no information (i.e., no one was remitted). All individuals were included in the analyses as long as they provided data at least one of the three outcome time points. For the moderator analysis, we included 105 out of the total 121 cases. In the mediation analysis, 100 out of 121 cases were included (a few additional cases were excluded due to missing mediator information). Unmeasured outcomes due to missing assessments were handled as missing data under the assumption that data are missing at random conditional on observed information (Little & Rubin, 2002).

In mixed effects modeling treating these repeated measures as categorical, we assumed linear trends over the log-transformed time (i.e., ln(actual time + 1)). As predictors of longitudinal trends of remission, represented by random effects (i.e., random intercepts and random slopes), we used treatment assignment status (FBT = 0.5; AFT = −0.5), one potential moderator or mediator (continuous moderators centered at their means, dichotomous moderators coded as 0.5 and −0.5, and mediators centered at zero) (Kraemer & Blassey, 2004), and treatment by moderator or treatment by mediator interaction (i.e., treatment × moderator, or treatment × mediator). We used maximum likelihood estimation implemented in Mplus, which is a widely used program for statistical modeling with latent variables or random effects (Muthen & Muthen (2009).

RESULTS

Detailed descriptions of participant baseline characteristics were published elsewhere (Lock et al., 2010). To summarize, participants had a mean age of 14.4 (SD 1.6) years, 82% IBW, and BMI of 16.1 (SD 1.1). Ninety-one percent of the sample was female and most had AN for less than one year (mean = 11.3 months, SD 8.6). A quarter (26%; N=31) of participants had a co-morbid psychiatric disorder with 17% of the total sample (N=20) taking psychotropic medications for these conditions at baseline, and most (79%; N=95) were from intact families.

Moderators of Change in Remission Status from Baseline to EOT

Among the 17 pre-randomization variables examined as potential moderators, baseline eating related obsessionality (YBC-ED-Total) and eating disorder specific psychopathology (EDE-Global) were identified as treatment effect moderators.

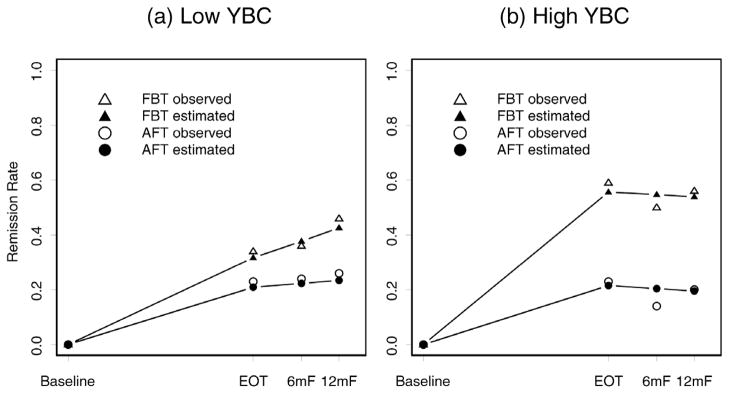

The baseline YBC-ED-Total was a significant moderator of treatment on change in remission status from baseline to EOT. The effect of receiving FBT (instead of AFT) was significantly larger for subjects with higher scores on YBC-ED-Total (see Figure 1). The results reported in Figure 1 are based on the median split (bottom 50% as low and top 50% as high YBC groups) to show the difference in treatment effects depending on the level of YBC-ED-Total. In Panels (a) and (b), the distance between the estimated curves for FBT and AFT can be interpreted as estimated treatment effects. Specifically, we used difference in remission rates between FBT and AFT as the effect size (SRD) (Kraemer & Frank, 2010). The difference between the treatment effects for the low and high YBC groups (i.e., the difference between the two SRDs) can be interpreted as the effect of moderation (i.e., interaction effect). Figure 1 shows a considerable difference in treatment effect between the high and low YBC groups. At EOT, for the high YBC group, the estimated remission rate is 0.556 for FBT and 0.215 for AFT (see Panel b), and therefore, the effect size (SRD) is 0.341. For the low YBC group, the estimated remission rate is 0.317 for FBT and 0.209 for AFT (see Panel (a)), and therefore, the effect size (SRD) is 0.108. The difference (i.e., 0.341 – 0.108) between the two treatment effects is 0.233 (p-value = 0.026, based on the analysis with continuous YBC-ED-Total), indicating that YBC-ED-Total is a possible treatment effect moderator.

FIGURE 1. Remission rates over time for individuals with low and high baseline YBC Total Score.

Note: The total sample was split based on the median YBC score into (a) 13 or less (N=56) and (b) 14 or more (N=49). In the time axis, EOT = end of treatment (12 months from the baseline), 6mF = follow-up at six months from EOT, and 12mF = follow-up at twelve months from EOT. We used a log transformation using ln(actual time + 1). In mixed effects modeling using three repeated measures of cure status (EOT, 6mF, 12mF), we assumed linear trends over this log-transformed time. Note that no one was remitted at baseline.

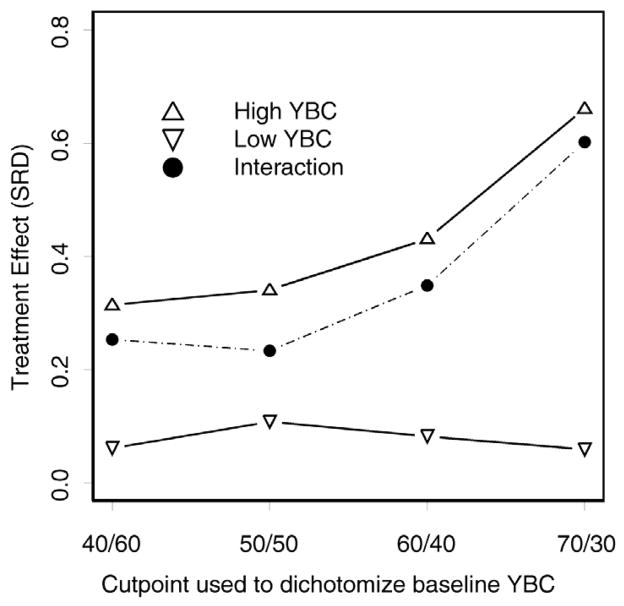

Figure 2 shows how the moderating effect of baseline YBC changes when the total sample was split into low and high baseline YBC groups based on different cut-points. As discussed above with Figure 1, based on the median split of YBC (bottom 50% as low and top 50% as high YBC groups), treatment effect (SRD) is 0.341 for the high YBC group (see the top curve), and 0.108 for the low YBC group (see the bottom curve), and the difference between the two effects (interaction effect) is 0.233 (see the dashed middle curve). Note, splitting the sample at the median provides the maximum number of participants in each subsample, which is important in these exploratory analyses where detecting significant interaction effect is extremely difficult with a limited total sample size. For that reason, the median is often used as a customary cut-point.

FIGURE 2. Baseline YBC as a moderator of treatment effect on change in remission status from baseline to EOT.

Note: The total sample was split into low and high baseline YBC groups based on different cutpoints. The results reported in Figure 1 are based on the median split (bottom 50% as the low and top 50% as the high YBC groups). The top and bottom curves show the treatment effects in terms of success rate difference (SRD), where SRD is defined as remission rate under FBT minus remission rate under AFT. The middle dashed curve shows the interaction effect, which is the difference between the SRD of the top curve (high YBC) and the SRD of the bottom curve (low YBC). N=44/61 at 40/60%, N=56/49 at 50/50%, N=65/40 at 60/40%, N=75/30 at 70/30%.

However, as shown in the additional analyses in Figure 2, using different cut-points may help identify individuals who would benefit the most from treatment. As we allocate more people to the low YBC group by moving the cut-point towards higher YBC values, the interaction effect is increased. For example, if we choose the 70%/30% cut-point, treatment effect is very large (0.661) for the high YBC group, and almost non-existent (0.059) for the low YBC group, and the difference between the two effects (interaction effect) is 0.602, which is much larger than the interaction effect we see with the median split (i.e., 0.233). The clinical implication of this finding is that participants with the most severe obsessive-compulsive features associated with AN, benefit most from FBT.

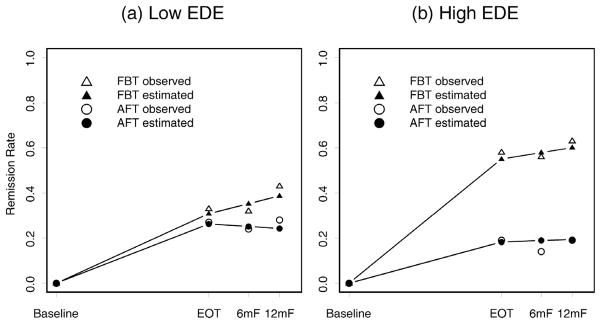

Baseline EDE-Global Score was also a significant moderator of treatment effect on change in remission status from baseline to EOT. The effect of receiving FBT (instead of AFT) was significantly larger for participants with higher scores on the EDE-Global. Figure 3 shows the effect of treatment assignment moderated by EDE-Global based on the median split (bottom 50% as low and top 50% as high EDE groups) and shows a considerable difference in treatment effect between the high and low EDE groups. At EOT, for the high EDE group, the estimated remission rate is 0.550 for FBT and 0.182 for AFT (see Panel (b)), and therefore the effect size (SRD) is 0.367. For the low EDE group, the estimated remission rate is 0.308 for FBT and 0.262 for AFT (see Panel (a)), and therefore the effect size (SRD) is 0.046. The difference (i.e., 0.367 – 0.046) between the two treatment effects is 0.321 (p-value = 0.027, based on the analysis with continuous EDE-Global score), indicating that EDE-Global is a possible treatment effect moderator. The results shown in Figure 3 are similar to those in Figure 1, which is probably due to the considerable correlation between YBC-ED-Total and EDE-Global (Spearman rho = 0.79).

FIGURE 3. Remission rates over time for individuals with low and high baseline EDE Global Score.

Note: The total sample was split based on the median EDE global score of (a) 1.41 or less (N=53) and (b) greater than 1.41 (N=52). In the time axis, EOT = end of treatment (12 months from the baseline), 6mF = follow-up at six months from EOT, and 12mF = follow-up at twelve months from EOT. We used a log transformation using ln(actual time + 1). In mixed effects modeling using three repeated measures of remission status (EOT, 6mF, 12mF), we assumed linear trends over this log-transformed time. Note that no one was remitted at baseline.

We also examined how the moderating effect of the baseline EDE changes when the total sample was split into low and high baseline EDE groups based on different cut-points as we did with the YBC-ED-Total. The results were similar to those displayed in Figure 2 as might be expected given the high correlation between YBC-ED-Total and EDE-Global, and suggest that the effect size of this interaction increases as symptoms on the EDE-Global increase (figure with these results not shown). Given the high correlation between these two variables, either might be used to identify patients who would best be treated using FBT rather than AFT.

Moderators of Treatment Effect on long-term outcome

Neither YBC-ED nor EDE-Global remained as significant treatment effect moderators during the maintenance period (i.e., EOT to 6- to 12-month follow-up). However, AN binge-eating/purging type (ANBP) emerged as a moderator during the maintenance period. This result may be clinically noteworthy, although tentative given analyses were based on a low frequency (15/105 cases were ANBP). The results showed that the effect of receiving FBT (instead of AFT) was significantly larger on change in remission status during this period for ANBP participants at baseline (p=0.009) (figure not shown).

Descriptive statistics providing clinical profiles of subsamples categorized based on each moderator (based on the median split for YBC-ED and EDE-Global, and YES/NO for ANBP) can be found in Table 1. These data suggest substantial overlap in the clinical profiles of sub-categories of individuals across YBC-ED, EDE-Global, and ANBP, indicating that there is likely similarity in the clinical populations associated with these moderators.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of subsamples at baseline categorized by moderator variables

| Yale Brown Cornell Eating Disorder Obsessive Compulsive Scale (YBC-ED) | Eating Disorder Examination (EDE Global Score) | AN Subtype | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <=13 n=56 |

>13 n=49 |

<=1.41 n=53 |

>1.41 n=52 |

Restrictor n=90 |

Binge/Purge n=15 |

|

| Age (years)* | 14.21 (1.67) | 14.58 (1.55) | 14.29 (1.68) | 14.48 (1.56) | 14.29 (1.63) | 14.93 (1.49) |

| Beck Depression Inventory | 9.86 (7.88) | 19.56 (9.27)3 | 9.25 (7.26) | 19.42 (9.40)3 | 13.27 (9.47) | 21.21 (.36)2 |

| Percentile Body Mass Index | 5.82 (7.37) | 6.68 (7.42) | 6.42 (7.80) | 6.02 (7.00) | 5.64 (6.58) | 9.67 (1.06)1 |

| Duration of illness (months) | 11.16 (8.76) | 12.50 (15.08) | 11.79 (8.74) | 11.79 (14.73) | 11.99 (12.7) | 10.63 (7.90) |

| Parental Empowerment | 19.97 (2.75) | 19.31 (3.65) | 19.89 (2.79) | 19.43 (3.56) | 19.88 (3.10) | 18.37 (3.59) |

| Parental Education (Years) | 17.89 (2.15) | 15.82 (3.08)3 | 17.73 (2.14) | 16.13 (3.16)2 | 17.10 (2.75) | 15.87 (3.04) |

| Rosenberg Self Esteem | 19.77 (6.53) | 26.52 (5.54)3 | 19.69 (6.28) | 26.08 (6.10)3 | 22.34 (7.05) | 26.36 (5.14)1 |

| Work and Social Adjustment Scale | 8.4 (7.24) | 17.21 (9.20)3 | 8.44 (7.34) | 16.52 (9.31)3 | 10.99 (8.59) | 22.07 (7.85)3 |

| Family Adjustment Devise (BC) | 1.84 (.41) | 2.07 (3.73)2 | 1.89 (.37) | 2.00 (.44) | 1.91 (.49) | 2.15 (.36)1 |

| Family Adjustment Devise (GF) | 1.92 (.53) | 2.12 (.55) | 1.89 (.49) | 2.12 (.59)1 | 1.94 (.51) | 2.46 (.57)3 |

| EDE Eating Concerns subscale | .50 (.86) | 1.99 (1.46) | NA | NA | .94 (1.24) | 2.75 (.81)3 |

| EDE Restraint subscale | 1.06 (1.43) | 3.33 (1.29)3 | NA | NA | 1.86 (1.72) | 3.72 (1.17)3 |

| EDE Shape Concerns Subscale | .85 (1.00) | 3.26 (1.55)3 | NA | NA | 1.70 (1.69) | 3.60 (1.29)3 |

| EDE Weight Concerns Subscale | .73 (1.01) | 2.61 (1.49)3 | NA | NA | 1.27 (1.36) | 3.64 (1.10)3 |

| YBC (Preoccupations) | NA | NA | 3.25 (3.90) | 9.08 (3.17)3 | 5.52 (4.54) | 10.20 (2.31)3 |

| YBC (Rituals) | NA | NA | 2.83 (3.48) | 8.57 (3.17)3 | 5.20 (4.43) | 8.87 (2.50)2 |

| Comorbid Psychiatric Disorder, n (%) | 8 (14.3) | 16 (32.7)1 | 7 (13.5) | 17 (32.1)1 | .19 (21.1) | 5 (33.3) |

| Intact Family, n (%) | 42 (75.0) | 40 (81.6) | 38 (73.1) | 44 (83.0) | 69 (76.7) | 13 (86.7) |

| Minority status, n (%) | 8 (14.3) | 16 (32.7)1 | 9 (17.3) | 15 (28.3) | 18 (20) | 6 (40) |

| Prior hospitalization, n (%) | 22 (39.3) | 23 (46.9) | 23 (44.2) | 22 (41.5) | 40 (44.4) | 5 (33.3) |

| Male, n (%) | 4 (7.1) | 6 (12.2) | 5 (9.6) | 5 (9.4) | 9 (10) | 1 (7) |

| Binge/Purge subtype, n (%) | 1 (1.8) | 14 (18.6)3 | 0 (0) | 15 (100)3 | NA | NA |

Note: Individuals were categorized into subsamples at the median for YBC-ED and EDE-G, and categorized into Yes/No for ANBP. Two sample t-tests were conducted to compare the subsamples in terms of various background variables (p-values corresponding to these tests are summarized as follow:

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001).

Value presented as Mean (SD), unless otherwise specified.

Mediators of Treatment Effect

Mediator analyses were conducted after dividing the entire sample into two groups based on baseline YBC-ED median score, which was identified as a moderator. We determined that splitting the sample on this single variable was reasonable because of the overlap among the identified moderators (supported by high correlations among them and by similar subsample profiles based on these variables). We examined early changes (from baseline to week 4) on the BDI, RSES, GSES, PVAS, and BMI percentile as potential mediators. None of these variables, however, were qualified as mediators in either of the subgroups (split at the median YBC-ED) in line with the McArthur approach (Kraemer et al., 2002; 2006; 2008) at the 5% significance level either at EOT or during the follow-up period.

Non-specific Predictors of Change in Remission Status from Baseline to EOT

Several baseline variables were non-specific predictors of change (i.e., not differing by treatment), in remission status from baseline to EOT, although they failed to meet criteria for treatment effect moderators. Prior hospitalization was a significant non-specific predictor of change in remission status. Individuals with prior hospitalization were less likely to reach remission status by EOT (p=.041). Age was also a significant non-specific predictor of change in remission status with older participants less likely to reach remission status by EOT (p=.024). Duration of illness also had a negative impact on change in remission status from baseline to EOT. Individuals with a longer duration of illness (p=.043) were less likely to reach remission status by EOT.

Non-specific Predictors of Change in Remission Status for the Maintenance Period

Several baseline variables were found to be non-specific predictors of change in remission status during the maintenance period (EOT to 6-month to 12-month follow-up). Prior hospitalization was a significant non-specific predictor of change in remission status during this period. Individuals with prior hospitalization improved their remission status at a higher rate than those without prior hospitalization (p=.017). Age was a significant non-specific predictor of change in remission status. Older participants’ remission status increased less during this period than that of the younger participants (p=.020). Baseline weight was also negatively related to change in remission status. Individuals starting with relatively higher weight were less likely to change remission status during the follow-up period, perhaps because they had less room for further improvement after EOT (p=.034).

DISCUSSION

We examined moderators and mediators of remission in a sample of 121 adolescents with AN who participated in an RCT comparing FBT and AFT. Among 17 pre-randomization variables examined, eating related obsessionality (YBC-ED-Total), and eating disorder specific psychopathology (EDE-Global) emerged as moderators of remission at EOT. These results underscore that eating related obsessionality moderates treatment outcome in AN, as has been suggested previously albeit in a more modest study (Lock et al., 2005). These findings also highlight our earlier cautious suggestion that weight gain often precedes cognitive changes in adolescents treated with FBT (Couturier & Lock, 2006). As FBT emphasizes behavioral change and weight gain rather than focusing on cognitions, we would cautiously argue that the impact of disrupting maintaining behaviors is central to initiating cognitive change for patients treated using this approach. In addition, but more tentatively, ANBP was a moderator of outcome at 12-month follow-up with this AN type doing better in FBT. All three moderators are closely related and may be measuring similar aspects of AN, namely associated eating disordered and general psychopathology. Together these findings show that patients in our study with higher levels of psychopathology benefit more from a targeted behavioral focus in FBT compared to patients with similar levels of psychopathology but allocated to the general adolescent developmental focus in individual therapy.

It is of interest that the one factor we anticipated might moderate outcome in favor of AFT did not do so. Based on data from previous studies, we thought that family processes associated with relatively high levels of EE, such as parental criticism toward their offspring, might favor AFT because the patient would not experience this critical environment during therapy (Eisler et al., 2000; Le Grange et al., 1992). However, seeing the adolescent separately from parents in AFT did not seem to confer this benefit. Perhaps AFT does not present the benefit that is presumably provided by separated FBT. In the latter, the therapist works closely with the parents to limit any criticism toward the adolescent. In AFT, on the other hand, the focus of the limited parental involvement is to promote adolescent autonomy. We also expected that older subjects, due to a more mature cognitive capacity and therefore greater ability to use self-directed insight oriented psychological interventions such as those employed in AFT, might do better in this treatment. However, this was not the case as age did not moderate outcome. It is possible that the relatively restricted age range in the study limited our ability to examine this possibility. As a result, this study did not distinguish a subgroup for which AFT works better. It would have been useful to know that AFT can be recommended for patients other than those who have no families available or whose families refuse FBT. Requiring that all participants have families willing to participate in FBT is a limitation in this regard.

We did not identify any mediators of treatment effect. It should be noted that after splitting the sample on the YBC-ED moderating variable, the sample size was likely too small to detect mediators even if they were present. Limited sample size will likely continue to make identifying mediators challenging in studies of AN.

Several baseline variables were non-specific predictors of change at EOT and for the maintenance period. The clearest narrative emerged for the three probably highly correlated variables that predicted outcome at EOT. That is, remission status was negatively impacted by the presence of prior hospitalization, age (older), and duration of illness (longer). Our finding echoes earlier work that identified illness duration as a predictor of treatment outcome (Dare, Eisler, Russell, Treasure & Dodge, 2001; Halmi et al., 2005; Russell et al, 1987). For the most, though, prior attempts to identify predictors of outcome have generated inconsistent findings (Fairburn et al., 2004).

Limitations

There are important limitations to this study. All adolescents and their families were treatment seeking, randomized to one of two study therapies, and medically stable for outpatient treatment (at or above 75% IBW at baseline) with low levels of comorbidity (25%), all of which restrict the generalizability of our findings. Investigators and centers known for work using family treatment for eating disorders conducted the study and we cannot rule out that this may have lead to biased expectations among participants. However, as noted elsewhere (Lock et al., 2010), treatment take up, drop out, and completion, as well as assessment completion, did not differ between randomized groups in this study, suggesting that families who received AFT did not experience a significant difference in their care. In addition, there is no consensus definition of remission for AN, though the one used here employs key elements (normalized weight and normalized eating psychopathology) consistent with recommendations in the literature (Couturier & Lock, 2006; Kordy, Kramer, Palmer et al., 2002; Strober, Freeman & Morrell, 1997). The use of these categorical outcomes in our analysis may have reduced power to detect moderators and mediators (Kraemer & Thienemann, 1987). However, the clinical relevance of the threshold set for this study in terms of remission makes the findings likely to be meaningful to clinicians and families seeking treatment (Frank, Prien, Jarrett, et al., 1991).

Conclusions

This study identified two important clinical features of AN, i.e., eating related obsessionality and eating disorder specific psychopathology, as moderators at EOT. Given the high correlation between these two indictors of eating disorder psychopathology, we consider this to be essentially one moderator at EOT. While YBC-Total and EDE-Global did not continue to moderate outcome at follow-up, should not mean that moderation does not exist. Larger sample sizes and more sensitive outcome measures, for instance, would increase power and provide a better opportunity to detect such moderation in future studies. From a clinical viewpoint this study suggests that for patients with higher levels of eating psychopathology FBT is clearly indicated. For adolescents with low levels of psychopathology both FBT and AFT appear useful psychotherapies. Clinicians could potentially use scores from either the EDE-Global or the YBC-ED to identify patients in these subgroups to help guide clinical decision-making. Although the findings of this study are exploratory in nature, they provide an important rationale for testing specific hypotheses related to moderation and mediation effects in future studies. Such studies, if feasible, could specifically examine heterogeneous treatment effects on outcome for patients with different levels of eating related psychopathology.

Highlights.

Eating related obsessionality and eating disorder specific psychopathology are moderators of treatment outcome.

FBT is indicated when levels of eating psychopathology are high, while FBT or AFT seem useful when levels are low.

Scores from the EDE-Global or YBC-ED can be utilized to identify patients in high vs. low eating psychopathology groups.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health grants R01-MH-070620 (Dr Le Grange) and R01-MH-070621, K24 MH-074467 (Dr. Lock). Drs. Le Grange and Lock receive royalties from Guilford Press and consultant fees from the Training Institute for Child and Adolescent Eating Disorders, LLC. Drs. Lock and Agras receive Royalties from Oxford University Press.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agras WS, Crow SJ, Halmi KA, Mitchell JE, Wilson GT, Kraemer HC. Outcome predictors for the cognitive behavior treatment of bulimia nervosa: data from a multisite study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:1302–1308. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.8.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington: American Psychiatric Association Press; 2000. Text Revision. [Google Scholar]

- Beck A, Steer R, Brown G. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bravender T, Bryant-Waugh R, Herzog D, et al. Classification of child and adolescent eating disturbances. Workgroup for Classification of Eating Disorders in Children and Adolescents (WCEDCA) International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40:S117–S22. doi: 10.1002/eat.20458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Growth Charts for the United States: Development and Methods. Atlanta: Center for Disease Control; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper Z, Cooper PJ, Fairburn CG. The validity of the eating disorder examination and its subscales. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1989;154:807–812. doi: 10.1192/bjp.154.6.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couturier J, Lock J. What constitutes remission in adolescent anorexia nervosa: a review of various conceptualizations and a quantitative analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2006;39:175–183. doi: 10.1002/eat.20224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dare C, Eisler I, Russell GFM, Treasure J, Dodge L. Psychological therapies for adults with anorexia nervosa: Randomized controlled trial of out-patient treatments. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;178:216–221. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.3.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisler I, Dare C, Hodes M, Russell G, Dodge E, Le Grange D. Family therapy for adolescent anorexia nervosa: the results of a controlled comparison of two family interventions. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2000;41:727–736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Agras WS, Walsh BT, Wilson GT, Stice E. Prediction of outcome in bulimia nervosa by early change in treatment. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:2322–2324. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick K, Moye A, Hoste R, Le Grange D, Lock J. Adolescent Focused Therapy for Adolescent Anorexia Nervosa. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy. 2010;40:31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Frank E, Prien RF, Jarrett RB, et al. Conceptualization and rationale for consensus definitions of terms in major depressive disorder: Remission, recovery, relapse, and recurrence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1991;48:851–855. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810330075011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden NH, Katzman DK, Kreipe RE, et al. Eating disorders in adolescents: position paper of the society for adolescent medicine. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;33:496–503. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00326-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halmi K, Agras W, Crow S, Mitchell J, Wilson T, Bryson S, Kraemer H. Predictors of treatment acceptance and completion in anorexia nervosa: Implications for future study designs. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:776–781. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.7.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebebrand J, Himmelmann G, Hesecker H, Schaefer H, Remschmidt H. The use of percentiles for the body mass index in anorexia nervosa: diagnostic, epidemiological, and therapeutic considerations. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1996;19:359–369. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199605)19:4<359::AID-EAT4>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmhaher B, Brent D, et al. Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children--present and lifetime version (KSADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinston W, Loader P. Eliciting whole-family interaction with a standardized interview. Journal of Family Therapy. 1984;6:347–363. [Google Scholar]

- Kordy H, Kramer B, Palmer RL, Papezova H, Pellet J, Richard M, Treasure J. Remission, recovery, relapse, and recurrence in eating disorders: conceptualization and illustration of a validation strategy. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2002;58:833. doi: 10.1002/jclp.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer H, Blassey C. Centering in regression analyses: a strategy to prevent errors in statistical inference. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:141–151. doi: 10.1002/mpr.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer H, Frank E. Evaluation of comparative treatment trials assessing clinical benefits and risks for patients, rather than statistical effects on measures. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;304:683–684. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer H, Frank E, Kupfer D. Moderators of treatment outcomes: clinical, research, and policy importance. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;296:1286–1289. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.10.1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer H, Kierman M, Essex M, Kupfer D. How and why criteria defining moderators and mediators differ between the Baron & Kenny and MacArthur Approaches. Health Psychology. 2008;27:S101–S108. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2(Suppl.).S101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer H, Thienemann S. Statistical Power Analysis in Research. Sage Publications, Inc; 1987. How Many Subjects? [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer H, Wilson GT, Fairburn CG, Agras WS. Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:877–884. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Grange D, Crosby R, Lock J. Predictors and moderators of outcome in family- based treatment for adolescent bulimia nervosa. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47:464–470. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181640816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Grange D, Eisler I, Dare C, Russell G. Evaluation of family treatments in adolescent anorexia nervosa: a pilot study. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1992;12:347–357. [Google Scholar]

- Le Grange D, Reinecke-Hoste R, Lock J, Bryson SW. Parental Expressed Emotion of Adolescents with Anorexia Nervosa: Outcome in Family-Based Treatment. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2011;44:731–734. doi: 10.1002/eat.20877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little R, Rubin D. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lock J, Agras WS, Bryson S, Kraemer H. A comparison of short- and long-term family therapy for adolescent anorexia nervosa. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44:632–639. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000161647.82775.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lock J, Couturier J, Bryson SW, Agras WS. Comparison of long term outcomes in adolescents with anorexia nervosa treated with family therapy. American Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45:666–672. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000215152.61400.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lock J, Le Grange D, Agras WS, Dare C. Treatment manual for anorexia nervosa: A family-based approach. New York: Guilford Publications, Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lock J, Le Grange D, Agras WS, Moye A, Bryson S, Jo B. A randomized clinical trial comparing family based treatment to adolescent focused individual therapy for adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67:1025–1032. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lock J, Le Grange D, Crosby R. Exploring possible mechanisms of change in family-based treatment for adolescent bulimia nervosa. Journal of Family Therapy. 2008;30:260–271. [Google Scholar]

- Mazure S, Halmi CA, Sunday S, Romano S, Einhorn A. The Yale-Brown-Cornell Eating Disorder Scales: Development, use, reliability, and validity. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1994;28:425–445. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(94)90002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundt JM, Shear I, Greist J. The Work and Social Adjustment Scale: a simple measure of impairment in functioning. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;180:461–464. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.5.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 5. Muthén & Muthén; 2009. pp. 1998–2009. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush S, Bryk A. Hierarchical linear models: applications and data analysis methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes P, Baillie A, Brown J, Madden S. Parental efficacy in the family-based treatment of anorexia: preliminary development of the Parents Versus Anorexia Scale (PVA) European Eating Disorders Review. 2005;13:399–405. [Google Scholar]

- Robin A, Siegal P, Moye A, et al. A controlled comparison of family versus individual therapy for adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Journal of the American Academy for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:1482–1489. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199912000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Conceiving the Self. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Russell GFM, Szmukler GI, Dare C, Eisler I. An evaluation of family therapy in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1987;44:1047–1056. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800240021004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strober M, Freeman R, Morrell W. The long-term course of severe anorexia nervosa in adolescents: survival analysis of recovery, relapse, and outcome predictors over 10–15 years in a prospective study. International journal of Eating Disorders. 1997;22:339. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199712)22:4<339::aid-eat1>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukmak V, Sirisoonthon A, Meena P. The validity of the general perceived self-efficacy scale. Journal of the Psychiatric Association of Thailand. 2001;47:31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Szmukler GI, Eisler I, Russell GFM, Dare C. Parental “Expressed Emotion”, anorexia nervosa and dropping out of treatment. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1985;147:265–271. doi: 10.1192/bjp.147.3.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT, Fairburn CG, Agras WS, Walsh BT, Kraemer H. Cognitive behavior therapy for bulimia nervosa: time course and mechanism of change. Journal of Clinical and Consulting Psychology. 2002;70:267–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]