Abstract

Voluntary wheel running (WR) is a form of physical activity in rodents that influences ingestive behavior. The present report describes an anorexic behavior triggered by the simultaneous introduction of a novel diet and WR. This study examined the sequential, compared with the simultaneous, introduction of a novel high-fat (HF) diet and voluntary WR in rats of three different ages and revealed a surprising finding; the simultaneous introduction of HF food and voluntary WR induced a behavior in which the animals chose not to eat although food was available at all times. This phenomenon was apparently not due to an aversion to the novel HF diet because introduction of the running wheels plus the HF diet, while continuing the availability of the normal chow diet did not prevent the anorexia. Moreover, the anorexia was prevented with prior exposure to the HF diet. In addition, the anorexia was not related to extent of WR but dependent on the act of WR. The introduction a HF diet and locked running wheels did not induce the anorexia. This voluntary anorexia was accompanied by substantial weight loss, and the anorexia was rapidly reversed by removal of the running wheels. Moreover, the HF/WR-induced anorexia is preserved across the age span despite the intrinsic decrease in WR activity and increased consumption of HF food with advancing age. The described phenomenon provides a new model to investigate anorexia behavior in rodents.

Keywords: anorexia, voluntary wheel running, high-fat feeding

1. Introduction

Activity-based anorexia is an animal model of anorexia, in which scheduled feeding, together with voluntary access to a running wheel, results in increased WR activity, hypophagia, and body weight loss [1]. As the feeding schedule becomes more restrictive, the WR activity increases, suggesting an inverse relationship between WR activity and food consumption [1]. Accumulating evidence suggests that both food consumption and voluntary WR share some neuro-behavioral characteristics of rewarding behavior. High-fat, sugar containing (HF) diets in particular have strong sensory appeals with reinforcing values, and hence are naturally rewarding [2]. When allowed to choose between HF diet and ordinary rat chow, rodents prefer HF diets and will consume a greater amount of calories when provided such diets [3,4]. Voluntary WR constitutes an activity behavior in rodents that affects ingestive behavior. The reinforcement value of food was reduced in rats with prior WR, while the reinforcing worth of running increased with food deprivation [5]. In our recent study, voluntary WR eliminated the dominant preference for HF food over chow diet, and the HF preference was restored when WR ceased. Moreover, elimination of the HF dietary preference was not correlated with the degree of WR, indicating the obliteration of HF preference was more related to the behavioral aspect of wheel running rather than the physical activity aspect. Thus, WR activity appears to be both naturally rewarding and reinforcing [4–6].

Activity based anorexia requires the simultaneous presence of two conditions; restricted access to food and free access to running wheels [7]. Considering the strong influence of WR on rat behavior, we hypothesized that access to WR may be more critical than restricted access to food for the induction of anorectic-type behavior. For example, other manipulations of the diet, such as switching to a novel diet, rather than scheduled feeding, may also induce activity based anorexia. To this end, we examined if the simultaneous introduction of a novel HF diet along with running wheels alters food consumption in a different way than the separate or sequential introduction of the HF diet and WR. We further investigated differences between rats of three ages, ranging from young to aged.

2. Material and methods

2.1 Experimental animals

Male F344 x Brown Norway (F344xBN) rats aged 3 (young), 16 (adult), or 21 (aged) months old were obtained from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN). Upon arrival, rats were examined and remained in quarantine for one week. Animals were cared for in accordance with the principles of the Guide to the Care and Use of Experimental Animals and protocols approved by the University of Florida IACUC committee. Rats were housed individually with a 12:12 h light:dark cycle (07:00 to 19:00 h). During the experimental period, rats were fed either a standard rodent chow (17% kcal from fat, 58% kcal from carbohydrate, 25% kcal from protein, 3.1 kcal/g, diet 7012, Harlan Teklad; Madison, WI) or a HF diet (60% kcal from fat, 20% kcal from carbohydrate (including 7% of the total kcal as sucrose), 20% of kcal from protein, 5.24 kcal/g, D12492, Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ) or provided with both diets. All diets were provided ad libitum.

2.2 Experimental design

This study consisted of four experiments. The first experiment comprised adult rats (n=12) accustomed to normal chow food and then provided running wheels for three days. At this point, the diet was switched from chow to HF, and half the rats allowed continued access to the running wheels and the other half denied access (sedentary).

The second experiment was similar to the first in that the adult animals (n=12) were accustomed to normal chow, but then half the rats were simultaneously introduced to HF and provided running wheels; whereas the other half were introduced to HF and remained sedentary for 4 days. Separately, a third group (n=20) was accustomed to the HF diet for one month and then half of the rats introduced to running wheels for 4 days and the other half remained sedentary.

In the third experiment, young and aged rats (n=6/group) were accustomed to normal chow and then simultaneously introduced to the HF diet (chow food removed) and provided access to running wheels for 3 days. At this point, the diet was switched back to chow while access to running wheels continued for one week. The experiment was repeated with only young rats (n=5–6/group), however, all rats were first introduced to the HF diet for one day, two days prior to the simultaneous introduction of the HF diet and running wheels or just the HF diet.

The fourth experiment was similar to the third in that a separate group of young and aged rats (n=6/group) were accustomed to normal chow and then simultaneously introduced to the HF diet and provided access to running wheels. However, in this experiment, chow food remained available throughout.

Body weight, food intake, and the extent of WR were recorded daily throughout the experiments. When the rats were provided access to both standard chow and the HF diet, consumption of both diets was determined separately by weight of food consumed. The position of the food trays containing the chow and HF food was alternated daily. Spillage of food was accounted for when calculating food consumption.

2.5 Wheel running

Rats were housed in cages equipped with Nalgene Activity Wheels (1.081 meters circumference, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) and allowed free access to the wheel. Each wheel was equipped with a magnetic switch and counter. The number of revolutions was recorded daily and meters (m)/day calculated.

2.8 Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by Student’s t-test or one-way or two-way ANOVA. When the main effect was significant (p <0.05), a Bonferroni post-hoc test was applied to determine individual differences between means. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

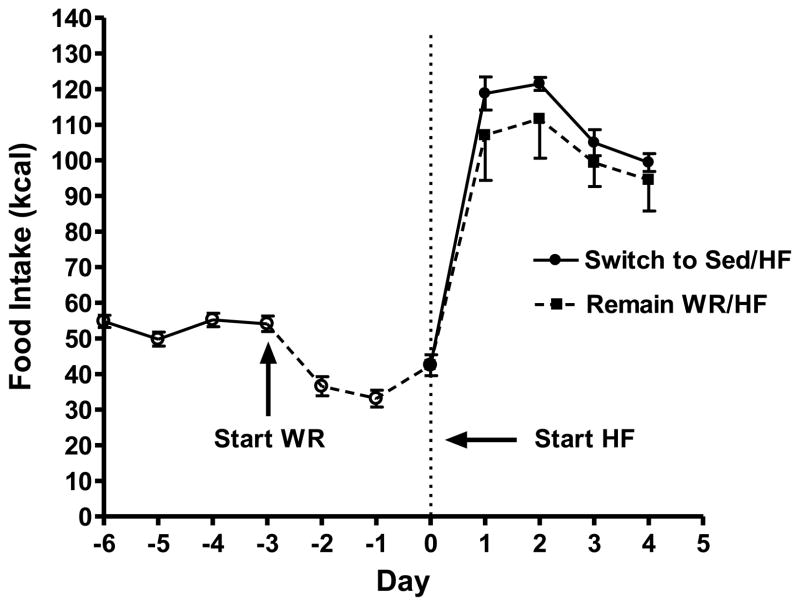

3.1 Experiment 1: Sequential introduction of WR and HF Diet does not result in anorexia

Rats consumed a steady amount of chow, approximately 54.1 ± 2.2 kcal/day (17.5 ± 0.7 g/day), prior to introduction of the running wheels (Fig. 1). During the WR phase on the chow diet, there was an expected decrease in food consumption of approximately 30% (Fig. 1). Wheel running during this period was 202 ± 21 m/day, an expected amount for this rat strain and age [8]. When the HF diet (60% kcal from fat, 7% sucrose, 5.24 kcal/g) was introduced, there was an immediate hyperphagia in both rats with continued access to running wheels and those switched back to sedentary as measured by kcal consumption (Fig. 1) or gram consumption (22.5 ± 0.9 g/day, Sedentary; 20.4 ± 2.3 g/day, WR).

Fig. 1.

Daily food consumption in kcal during three phases of Experiment 1; pre-experimental chow consumption (open circles); introduction of running wheels with continuation of the chow feeding (open circles, dashed line); and replacement of chow with the HF diet. At the initiation of the latter phase, the rats are divided into two groups, those in which the running wheels are removed (Switch to Sed/HF, closed circles, solid line) and those with continued access to WR (Remain WR/HF, closed squares, dashed line). Values represent the mean ± SE of 6 rats per group. For Remain WR/HF group, only lower standard error is shown.

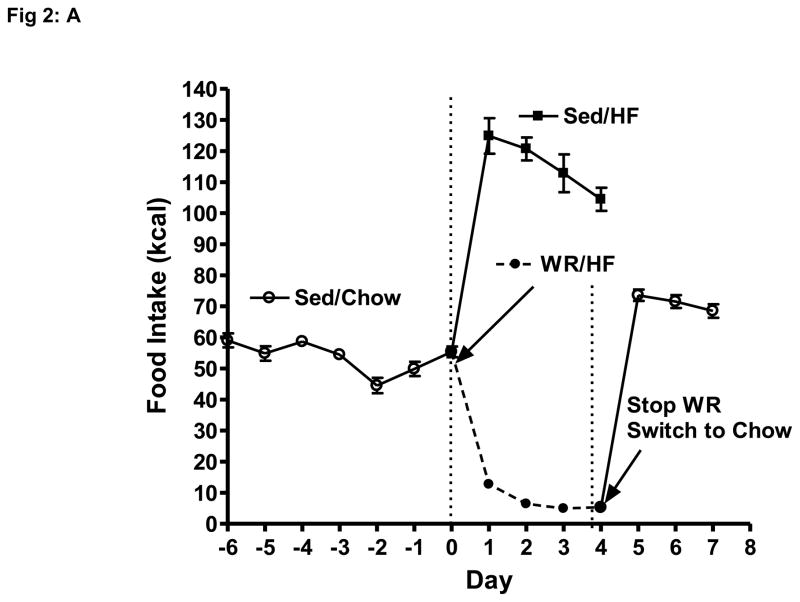

3.2 Experiment 2: Simultaneous introduction of WR and HF Diet results in anorexia

In experiment two, instead of sequential introduction of HF followed by WR, chow accustomed rats were simultaneously switched from chow to HF and allowed access to running wheels or switched to the HF diet and remained sedentary. With the latter, when the HF diet is introduced in the absence of WR, there is the expected hyperphagia (Fig. 2A, Sed/HF). Surprisingly, the rats simultaneously provided HF and running wheels immediately became anorexic, eating only a nominal amount of food (Fig. 2A, WR/HF). The HF-fed rats provided running wheels ran 190 ± 24 m/day, an amount similar to the wheel running in Experiment 1 (Table 1). This experiment was terminated after 4 days to prevent excessive weight loss. When the running wheels were removed and the diet switched to chow, the rats immediately resumed eating at a level higher than the normal amount of chow diet (Fig. 2A, days 5 to 7, 72.8 ± 1.3 kcal/day vs. days minus 3 to 0, 51.0 ± 1.8 kcal/day, p <0.001). This study was repeated in a separate set of virgin rats, in which the running wheels and HF diet were introduced simultaneously; however, in half the rats, the running wheel were locked to prevent WR. In this case, anorexia was observed in those rats that could run and not in the rats with access to only locked wheels. The latter ate the expected amount of HF diet (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

A. Daily food consumption in kcal during the three phases of Experiment 2; pre-experimental chow consumption (open circles); introduction of the HF diet with and without running wheels, and removal of HF diet and running wheels. At the initiation of the second phase, the rats are divided into two groups, those which remain sedentary (Sed/HF, closed squares, solid line) and those provided access to WR (WR/HF, closed circles, dashed line). In the final phase, the running wheels and HF is removed and chow diet provided to the latter group (day 5, open circles, solid line). Values represent the mean ± SE of 6 rats per group.

B: Change in body weight during phases two and three of the experiment described in Fig. 2A. The HF diet was introduced without (closed squares) and with (closed circles, dashed line) running wheels. At day 4, in the latter group, the running wheels were removed and the diet switched to chow (closed circles, solid line). Body weights at day zero were 484 ± 20 g (closed squares) and 484 ± 13 g (closed circles). Values represent the mean ± SE of 6 rats per group.

C: Daily food consumption in kcal in HF diet accustomed rats. At day zero, the rats are divided into two groups, those remaining sedentary (closed circles) and those provided running wheels (open squares). Values represent mean ± SE of 10 rats per group.

Table 1.

Wheel running during normal chow feeding and anorectic periods.

| AGE | Normal Feeding Period Only Chow Available (m/day) | Anorectic Period with Only HF Available (m/day) | Anorectic Period with HF and Chow Available (m/day) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 months | 1017 ± 108* | 821 ± 114* | 790 ± 56* |

| 16 months | 202 ± 21 | 190 ± 24 | No entry |

| 21 months | 245 ± 27 | 168 ± 20 | 201 ± 19 |

Data represents mean of meters/day ± SE of 6 rats.

P<0.0001 for difference with age by two-way ANOVA for 3 and 21 month old rats. P <0.001 for difference between 3 month group and either 16 month or 21 month in each feeding period by post-hoc analysis.

Body weight during the different phases of the experiment followed the pattern of total caloric consumption. Those rats switched to the HF diet without access to running wheels, as expected, steadily gained weight, whereas those with the simultaneous addition of running wheels lost 40 g of body weight during the anorexic period (Fig. 2B). After removal of the running wheels, these rats regained some of the lost weight, however body weight remained lower at 10 days after wheel removal compared with the HF-fed sedentary rats (453± 14 vs. 544 ± 24 g, p =0.009).

We further examined the consequences of WR on rats that were accustomed to the HF diet, that is, after the hyperphagic phase partially attenuated and HF consumption was stable. In this case, the introduction of WR reduced HF kcal consumption by approximately 44% (Fig. 2C), an amount greater than the reduction observed in Experiment 1 when WR was initiated in chow fed rats but considerably less than the near complete anorexia observed with the simultaneous introduction of HF and WR (Fig. 2A). This WR-induced reduction in HF consumption was similar to our previous report where we evaluated the consequences of WR in young F344xBN rats accustomed to the HF diet. In those studies, WR reduced food consumption by approximately 50% (85.9 ± 2.2 to 47.2 ± 2.8 kcal/day [4]).

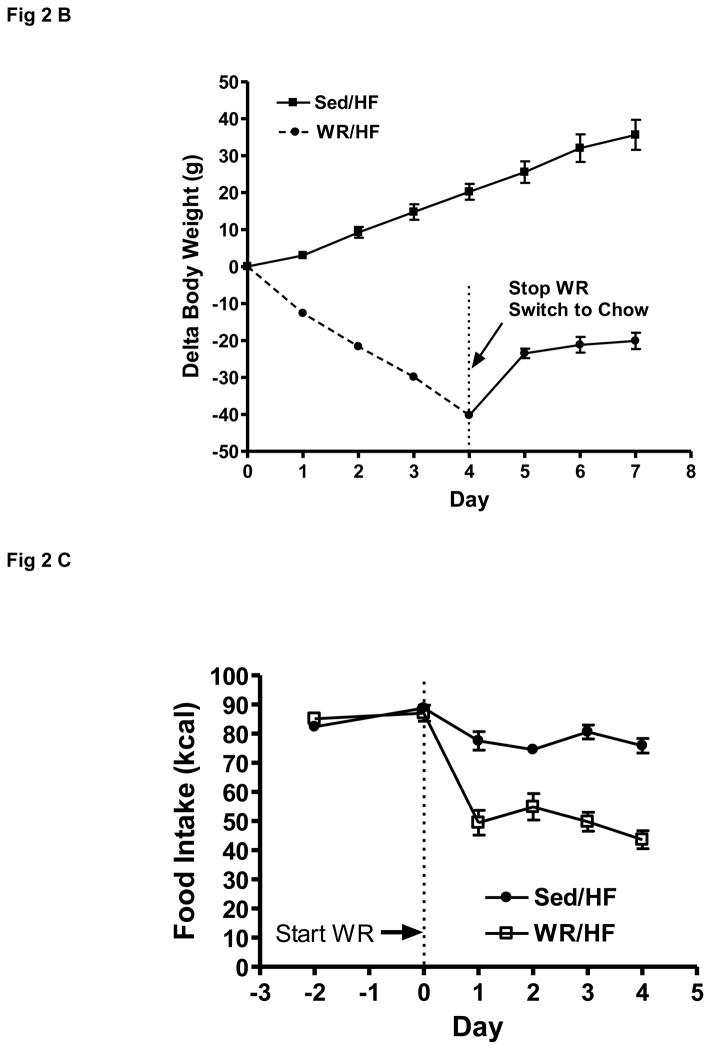

3.3 Experiment 3: Simultaneous introduction of WR and HF diet in young and aged rats results in anorexia

Body weight increases with age in F344xBN rats [9]. Two other characteristics of these aged rats is a reduced level of voluntary WR (Table 1 and [8]) as well as an increased hyperphagia following introduction of a HF diet [8]. Thus, we hypothesized that the heightened HF food consumption, coupled with the reluctance to WR, would dampen the HF/WR-induced anorexia in aged compared with young rats. To examine this possibility, we duplicated the initial part of Experiment 2 in 3 and 21 month old rats accustomed to chow followed by simultaneous introduction of HF and running wheels. Surprisingly, the behavior of the young and aged rats was nearly identical, with a near complete anorexia (Fig. 3A). This was despite that the aged rats run only 20% of the distance observed in young rats (Table 1, 2nd data column). Similar to the adult rats, when the running wheels were removed and the HF diet switched to chow, the rats ate normally (Fig. 3A, day 6).

Fig. 3.

A. Daily food consumption in kcal during the three phases of experiment 3 with young (closed circles) and aged (open squares) rats; pre-experimental chow consumption; introduction of a HF diet simultaneously with running wheels (dotted line); and switching from the HF to the chow diet at end of day 3. The value indicated at day 6 represents the average of the three day consumption from days 4 to 6. Error bars in some cases are less than size of symbol.

B: Daily food consumption in kcal during the three phases of an experiment when the HF food is introduced for one day prior to the start of experiment (day 0) using only young rats. During the pre-experimental chow consumption (open circles), the HF diet is introduced for 1 day (closed circle), followed by a return to the chow diet. At day 0, the HF diet is provided without (closed circles) and simultaneously with (closed squares) running wheels. At day 4, the running wheels are removed and diet switched to the chow diet (open circles). Values represent the mean ± SE of 11 rats (pre-experimental) and 5–6 rats per group starting at day 0. Error bars in some cases are less than size of symbol.

Body weight paralleled the changes in food consumption, with a 26 g decrease in the young rats and 45 g decrease in the aged (Table 2). Interestingly, after removal of the running wheels along with returning to the chow diet (day 3), the young rats fully recovered the lost body weight by day 10, whereas the aged rats remained at a significantly lower body weight (Table 2).

Table 2.

Body weight of young and aged rats before and after wheel running in Experiment 3.

| AGE | Pre-Wheel Running Day 0 (g) | End of WR Period Day 3 (g) | End of Recovery Period Day 10 (g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 months | 264 ± 9.3 | 238 ± 10* | 274 ± 10** |

| 21 months | 552 ± 16 | 507 ± 17* | 521 ± 17** |

Data represents mean ± SE of 6 rats.

P<0.0001 for difference with WR from pre-WR by paired t-test.

P <0.0001 for difference with recovery from pre-WR value by paired t-test.

3.4 Pre-exposure to HF diet prevents the anorexia

To examine if the novelty of the HF diet is critical to induce the anorexia, exposure to the HF diet was provided for one day prior to starting the experiment. That is, young rats were provided the HF diet for one day, returned to normal chow for the next two days, and then the HF diet and WR introduced simultaneously to half the rats whereas the other half received the HF diet but remained sedentary. This prior exposure to the HF diet prevented the anorexia associated with the novel introduction of the HF diet and WR (Fig. 3B). As expected, food consumption was diminished in the WR/HF group compared with the sedentary HF fed rats by the same degree as when the HF diet and WR are introduced sequentially (compare Fig. 2C (44% decrease) to Fig. 3B (46% decrease at day 4). When the WR ceased and the chow diet was provided, food consumption returned to pre-experimental values (Fig. 3B).

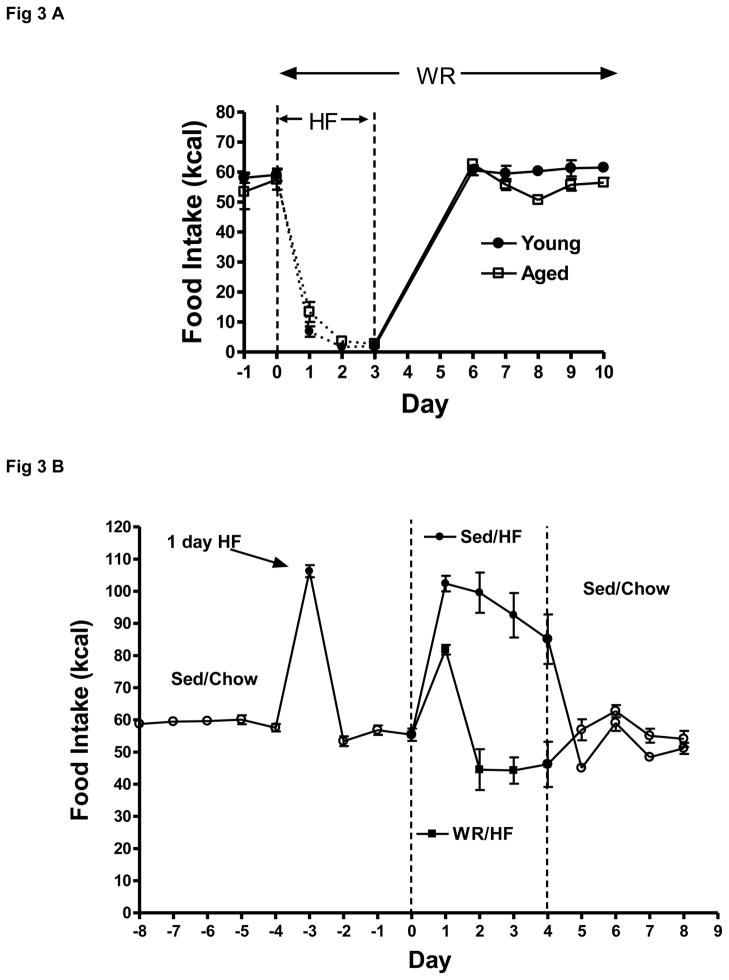

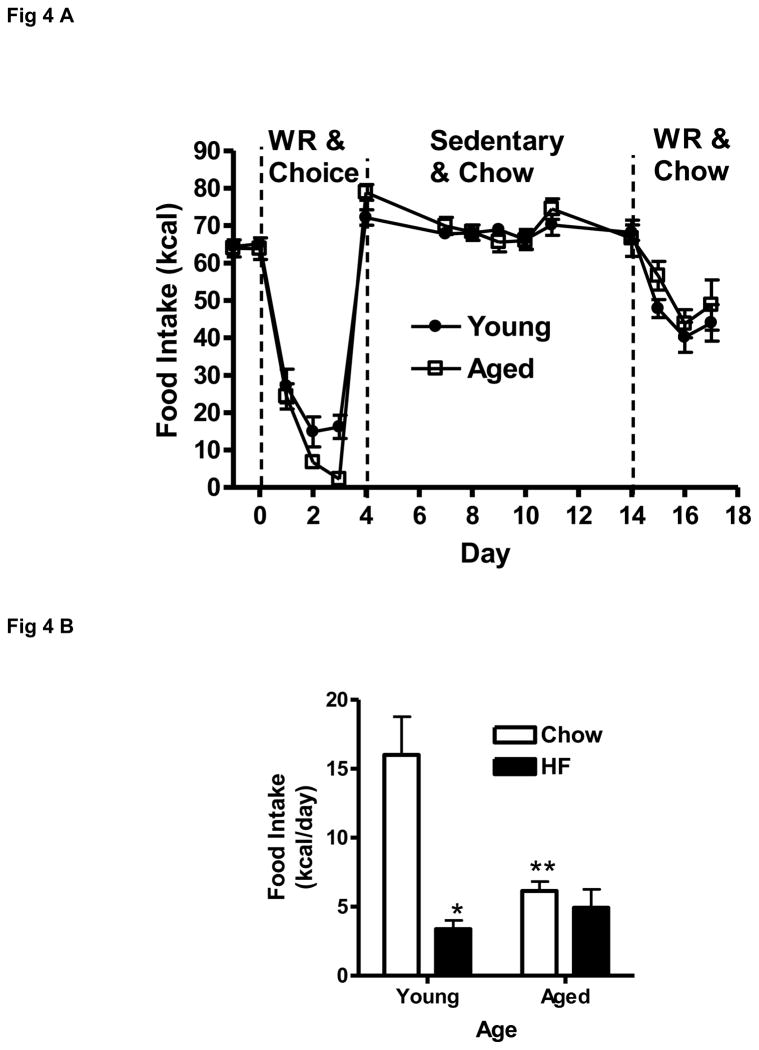

3.5 Experiment 4: Simultaneous introduction of WR and HF diet without removal of the chow diet results in anorexia

To examine whether the simultaneous introduction of running wheels and a novel HF diet induced a true anorexia, or an aversion to the novel diet, we repeated the experiment described in Fig. 3A with virgin rats, but did not remove the chow diet when the HF diet and running wheels were introduced. Young and old rats accustomed to chow were introduced to running wheels and provided equal access to both the original chow diet and the novel HF diet. The pattern of food consumption after addition of WR and the HF diet was qualitatively the same as when the chow diet was removed (Fig. 4A). The aged rats consumed almost no food, almost identical to what was observed with the introduction of HF diet and running wheels in the absence of chow (Fig. 3A). The young rats, however, ate a small but significantly greater amount of food than the older rats (Fig 4B) and ate a greater amount than the rats in the experiment described in Fig. 3A in the absence of chow (16.0 ± 2.8 vs. 3.4 ± 1.0 kcal/day, p =0.002). Moreover, the food consumption during the choice period by these young rats was predominately chow (Fig. 4B). This daily average consumption of chow though was considerably less than would be expected with just the introduction of running wheels (16.0 ± 2.8 vs. 37.3 ± 2.3 kcal/day, p <0.001; compare Fig. 4A to Fig. 1).

Fig. 4.

A. Daily food consumption in kcal during the four phases of experiment 4 with young (closed circles) and aged (open squares) rats; pre-experimental chow consumption (Days -1 to 0); introduction of a HF diet simultaneously with running wheels with continued availability of chow (Days 1 to 3); removal of HF diet and running wheels with continuation of chow (Days 4 to 14); and reintroduction of the running wheels (Days 15–17). During the second phase of the experiment with a choice between consumption of chow or HF diet, the data represent the sum of the chow and HF consumption. Values represent the mean ± SE of 6 rats per group.

B: Chow (open bars) and HF (solid bars) daily food consumption during the phase two (Days 1–3) of the experiment described in Fig. 4 Top. Values represent the mean ± SE of 6 rats per group. p=0.017 for difference with age and p=0.0003 for difference with diet by two-way ANOVA. *p <0.001 for difference with diet in Young group by Bonferroni post-hoc analysis. **p <0.01 for difference with age in chow consumption by Bonferroni pos-hoc analysis.

When the running wheels were removed and only the chow provided, the rats resumed eating at level greater than the pre-experimental chow consumption (Fig. 4A, day 4 vs day 0; Young: 72.1 ± 2.1 vs. 65.1 ± 1.5 kcal/day, p <0.02; Aged: 78.9 ± 2.1 vs. 63.8 ± 2.8 kcal/day, p <0.002). After a two week period of only chow consumption, these rats were again provided running wheels with the chow diet continued uninterrupted. The rats demonstrated the expected decline in chow consumption, but no severe anorexia (Fig. 4A, day 15).

3.6 Wheel running is altered by age but not the period of anorexia

Wheel running in the two groups of older rats was significantly less compared with the young rats under normal chow feeding (Table 1). Similarly, WR was diminished with age during the anorectic period when only the HF diet was available and in the period with both HF and chow available (Table 1). However, within each age group, wheel running during the periods of normal chow consumption and the two different types of anorectic periods was not significantly different (Table 1). Thus, overall there was an age-dependent change in WR but this was not the case across periods of feeding or anorexia.

4. Discussion

This report describes a new anorexic behavior, one in which the animals chose not to eat although food is available at all times. The present study examined the sequential, compared with the simultaneous, introduction of a novel HF diet and voluntary WR in rats of three different ages and revealed a salient and surprising finding; the simultaneous introduction of HF food and voluntary WR induced a behavior in which the rats chose not to consume food. This anorexia was not related to the extent of WR but dependent on the act of WR. Moreover, this phenomenon was apparently not due to an aversion to the novel HF diet because introduction of the running wheels simultaneously with the HF diet, while continuing the availability of the normal chow diet, did not prevent the anorexia. Furthermore, a brief prior exposure to the HF diet prevented the anorexic behavior. The 4 day period of anorexia was accompanied by substantial weight loss, followed by a partial regain of the lost weight after removal of the running wheels.

Another animal model demonstrating anorexic behavior is the activity-based anorexia model. In this model, rats or mice put on a restricted feeding schedule with access to a running wheel demonstrate excessive WR, weight loss, and ultimately death [1]. Maximal WR activity occurs when the access to food is limited to single time per day [1]. Without access to the running wheels, the rats compensate by consuming a greater amount of food during the restricted feeding periods [1], suggestive that the interaction between the two conditions, access to running wheels and scheduled feeding is causative.

Similarly, in the present study, the conditions that trigger the anorexia are the introduction of the novel diet and the simultaneous access to WR. These rats voluntarily choose not to eat, despite the continual availability of HF food. The HF food is a favored diet, and this strain of rats will consume only the HF when given the choice between HF and chow [4]. Moreover, when both the running wheels and the HF diet are sequentially introduced (in any order), the rats robustly consume the HF food, suggesting there is no adverse interaction between these two activities that would lead to food aversion. Furthermore, in the variation of the above experimental protocol when HF food and running wheels were simultaneously introduced, but chow food was retained, a similar anorexia was observed. Moreover, if the HF diet is briefly introduced for one day, the rats returned to normal chow food and then simultaneously provided the HF diet and running wheels, the rats consume food normally. This suggests the phenomenon may not be related to the specific diet, but possibly related to a complex behavioral response to the introduction of a novel diet and WR activity.

The anorexia is apparently dependent on the act of WR and not just the presence of running wheel in the cages. Introduction of locked running wheels simultaneously with the HF diet did not induce anorexia. Moreover, the extent of WR does not appear to be critical. The WR/HF induced anorexia was observed in rats of three different ages, young, adult and aged. F344xBN rats demonstrate a gradual increase in body weight until early senescence (24 months) followed by decline in late life similar to the pattern of weight gain and decline in humans [9]. Two characteristics of aging in these rats are a reduced level of voluntary WR [8] and an increased hyperphagia and exacerbated weight gain following introduction of a HF diet [8]. Thus, with both the physiological response to HF food and the extent of WR inherently different with age, it would predict that introduction of both WR and HF simultaneously across ages would result in distinct responses. The observation of a nearly identical anorexia across ages with the simultaneous introduction the WR/HF diet suggests induction of a complex behavioral response beyond that of the physical aspects of wheel running or the reward-associated palatability of the typical high-fat, sucrose containing diet. Moreover, the 4-fold greater degree of WR in the young compared with the older rats, in conjunction with a similar anorexia response across ages indicates that the observed phenomenon is not related to the extent of WR, but suggestive that the anorectic response is related to the act of WR. When running wheels were available; the rats ran the expected distance for this rat strain and ages. F344xBN rats do not run to the same extent as Sprague Dawley rats, and there is dramatic decrease in voluntary WR with increasing age [8]. There is also an effect of diet on the extent of wheel running in this strain. HF-fed rats run to lesser degree, however this effect of diet diminishes with increasing age [8]. In the present study, under ad libitum chow consumption, the extent of WR was diminished in the two older groups compared with the young rats. During both anorectic periods, i.e., HF available (but not eaten) and both chow and HF available (very little eaten, mostly chow); WR activity was similar to that during normal chow feeding.

When the anorexia was terminated by removal of the running wheel and rats returned to the normal chow diet, there was increased consumption compared with chow consumption during the pre-experimental control period. This is the typical over-consumption response in rats that have been food restricted. In this case, food was not restricted; however, the food restriction-like over-consumption response is consistent with the concept that the rats were under nourished.

One difference observed with age was the extent of anorexia in Experiment 3 versus Experiment 4. In Experiment 3, the running wheels were introduced along with the HF diet and the chow diet removed, while in Experiment 4 the running wheels were introduced along with the HF diet and the chow diet retained. The young and aged rats behaved in a nearly identical manner in Experiment 3, displaying a severe anorexia. The aged rats also demonstrated a similar anorexia in Experiment 4. However, the younger rats ate a small amount of chow food in Experiment 4. The aged rats lost a greater amount body weight during the anorexia than the young rats and, as opposed to the young, did not fully regain the body weight after the running wheels were removed (Table 2). This impaired ability to regain lost body weight following food restriction is typical of aged rats [10]. It is possible the different metabolic states in young versus aged rats contributed to amount of food consumed in paradigm used in Experiment 4.

Wheel running is a rewarding behavior that substitutes for some of the rewarding aspects of a HF diet. We previously demonstrated that WR obliterated the preference for HF food in an HF/chow choice paradigm [4]. When facing such a choice in the absence of running wheels, rodents scarcely consumed the nutritiously adequate, low-fat chow food. On the contrary, rats with free access to running wheels consumed equal gram amounts of both chow and the highly palatable HF diet. Moreover, the WR-mediated elimination of the preference for HF food was associated with enhanced leptin-mediated phosphorylated-STAT3 signaling specifically in the VTA region of the brain and not in other hypothalamic or extra-hypothalamic brain regions examined [11].

Leptin function has also been implicated in the activity-based anorexia rat model where it is proposed that reduced leptin function may be related to the hyperactivity [7]. Leptin treatment reduces WR activity of activity-based anorectic rats but not in control counterparts [7]. In contrast, we reported that in the F344xBN rat strain, hypothalamic leptin overexpression increases WR activity whereas overexpression of a dominant-negative antagonist reduces WR [12]. Considering the importance of leptin in energy balance and the positive-relationship between WR activity and enhanced leptin signaling, it is likely that leptin function plays a role in the HF/WR induced anorexia observed herein. However, it is even more likely that a cadre of neuropeptides are involved [13]. The role of leptin however, and the exact mechanisms underlying the HF/WR induced anorexia remain unknown at the present time.

In summary, this report describes a new animal model demonstrating anorexic behavior. This syndrome was induced by the simultaneous introduction of both a novel HF diet and voluntary wheel running. This voluntary anorexia is independent of whether the original chow food is retained or removed. Moreover, the anorexia is prevented by a prior exposure to the HF diet. The HF/WR-induced anorexia is preserved across the age span despite intrinsic decreases in WR activity and increased consumption of HF food with increasing age. The anorexia is rapidly reversed by removal of the running wheel and appears to be related to the act of WR rather than the extent of WR. This phenomenon provides a new model to investigate anorexia behavior in rodents.

Highlights.

Concurrent introduction of running wheels and a high-fat diet induced anorexia.

The anorexia did not occur if the rats were pre-exposed to the high-fat diet.

The anorexia was not due to an aversion to the high-fat diet.

Aged and young rats that run to different extents displayed the same anorexia.

This may represent a new model to investigate anorexia behavior in rodents.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Institute on Aging Grant AG-26159, University of Florida Institute on Aging and the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center NIH P30 AG028740, and the Medical Research Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Casper R, Sullivan E, Tecott L. Relevance of animal models to human eating disorders and obesity. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;199:313–29. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cota D, Barrera JG, Seeley RJ. Leptin in energy balance and reward: two faces of the same coin? Neuron. 2006;51(6):678–680. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prats E, Monfar M, Castella J, Iglesias R, Alemany M. Energy intake of rats fed a cafeteria diet. Physiol Behav. 1989;45(2):263–272. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(89)90128-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scarpace PJ, Matheny M, Zhang Y. Wheel running eliminates high-fat preference and enhances leptin signaling in the ventral tegmental area. Physiol Behav. 2010;100:173–9. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pierce WD, Epling WF, Boer DP. Deprivation and satiation: The interrelations between food and wheel running. J Exp Anal Behav. 1986;46(2):199–210. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1986.46-199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Visser L, van den Bos R, Stoker AK, Kas MJ, Spruijt BM. Effects of genetic background and environmental novelty on wheel running as a rewarding behaviour in mice. Behav Brain Res. 2007;177(2):290–297. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hillebrand JJG, Kas MJH, van Elburg AA, Hoek HW, Adan RAH. Leptin’s effect on hyperactivity: Potential downstream effector mechanisms. Physiol Behav. 2008;94:689–95. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Judge MK, Zhang J, Tumer N, Carter C, Daniels MJ, Scarpace PJ. Prolonged hyperphagia with high-fat feeding contributes to exacerbated weight gain in rats with adult-onset obesity. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;295(3):R773–780. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00727.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwartz RS. Obesity in the elderly. In: Bray BC, James WPT, editors. Handbook of obesity. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1998. pp. 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolden-Hanson T, Marck BT, Matsumoto AM. Blunted hypothalamic neuropeptide gene expression in response to fasting, but preservation of feeding responses to AgRP in aging male Brown Norway rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;287(1):R138–46. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00465.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matheny M, Shapiro A, Tümer N, Scarpace PJ. Region-specific diet-induced and leptin-induced cellular leptin resistance includes the ventral tegmental area in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60:480–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matheny M, Zhang Y, Shapiro A, Tümer N, Scarpace PJ. Central overexpression of leptin antagonist reduces wheel running and underscores importance of endogenous leptin receptor activity in energy homeostasis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;297:R1254–61. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90449.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adan RAH, Hillebrand JJG, Danner UN, Cano SC, Kas MJH, Verhagen LAW. Neurobiology driving hyperactivity in activity-based anorexia. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2011;6:229–50. doi: 10.1007/7854_2010_77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]