Abstract

Objective

Primary cilia are present in almost every cell type including chondrocytes. Studies have shown that defects in primary cilia result in skeletal dysplasia. The purpose of this study was to understand how loss of primary cilia affects articular cartilage.

Design

Ift88 encodes a protein that is required for intraflagellar transport and formation of primary cilia. In this study, we used Col2aCre;Ift88fl/fl transgenic mice in which primary cilia were deleted in chondrocytes. Col2aCre;Ift88fl/fl articular cartilage was characterized by histological staining, real time RT-PCR, and microindentation. Hedgehog (Hh) signaling was measured by expression of Ptch1 and Gli1 mRNA. The levels of Gli3 proteins were determined by western blot.

Results

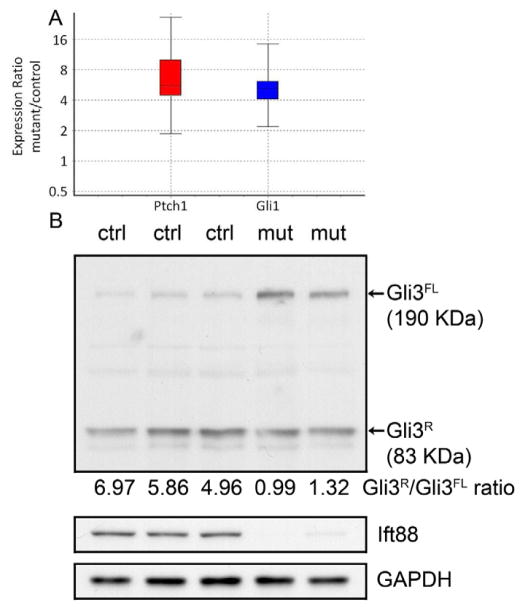

Col2aCre;Ift88fl/fl articular cartilage was thicker and had increased cell density, likely due to decreased apoptosis during cartilage remodeling. Mutant articular cartilage also showed increased expression of osteoarthritis (OA) markers including Mmp13, Adamts5, ColX, and Runx2. OA was also evident by reduced stiffness in mutant cartilage as measured by microindentation. Up-regulation of Hh signaling, which has been associated with OA, was present in mutant articular cartilage as measured by expression of Ptch1 and Gli1. Col2aCre;Ift88fl/fl cartilage also demonstrated reduced Gli3 repressor to activator ratio.

Conclusion

Our results indicate that primary cilia are required for normal development and maintenance of articular cartilage. It was shown that primary cilia are required for processing full length Gli3 to the truncated repressor form. We propose that OA symptoms in Col2aCre;Ift88fl/fl cartilage are due to reduced Hh signal repression by Gli3.

Keywords: primary cilia, Hedgehog signaling, Gli3, osteoarthritis, cartilage, chondrocyte

Introduction

Once thought to be a vestige of evolution, primary cilia are now considered as an important organelle regulating many cellular functions. Primary cilia are formed from centrioles. Unlike motile cilia, primary cilia are generally immotile and comprised of a (9+0) microtubule doublet arrangement [1, 2]. Formation and maintenance of primary cilia are carried out by a process called intraflagellar transport (IFT). IFT proteins associate with motors, kinesin or dynein, to carry cargos into or out of cilia, respectively. Deletion of IFT or motor proteins from a cell results in depletion of primary cilia. Primary cilia serve as cellular antenna to transduce signals for Hedgehog (Hh), canonical/noncanonical Wnt, Platelet Derived Growth Factor, and fluid flow [3, 4]. In humans, defects in primary cilia are associated with genetic disorders called ciliopathies [5, 6]. The clinical symptoms include polycystic kidneys, brain malformation, situs inversus, retinal degeneration, obesity and skeletal dysplasia, reflecting the diverse functions of primary cilia.

The role of primary cilia in different aspects of skeletal development has been shown in several studies using mouse models [7, 8]. Primary cilia are important for embryonic skeletal development including limb patterning and endochondral bone formation [9]. Postnatally, primary cilia are important for growth plate organization [10]. In articular cartilage, the orientation of primary cilia has been shown and it has been suggested, based on interaction of the cilium with the matrix, that primary cilia on chondrocytes play a role in sensing mechanical signals [11–13]. Nevertheless, the role of primary cilia in development and maintenance of articular cartilage is still unclear.

Among the signaling pathways that can be regulated by primary cilia, Hedgehog (Hh) signaling is the most studied. The signaling events start from binding of Hh ligand to the receptor, Patched (Ptch), which abrogates inhibition of another membrane protein called Smoothened (Smo). Smo transduces signals to Gli transcription factors, which enter the nucleus and regulate target genes (reviewed in [8]. It has been shown that components of Hh signaling such as Smo [14], Suppressor of fused (Sufu), and Gli proteins are enriched in primary cilia [15]. Translocation of Smo to the primary cilia is required to activate Hh signaling in response to ligand (Reviewed in [8]). Moreover, primary cilia are required for proteolytic cleavage of the full length Gli3 activator to a repressors form in the absence of Hh ligand. [15, 16]. In the absence of primary cilia, both the ligand-mediated activation of Gli and ligand-independent processing of the Gli3 repressor are abrogated [15–17]. Since cilia are required for both ligand-mediated activation of the pathway and Gli3-mediated repression of target gene expression, depletion of cilia has varying effects depending on whether activator or repressor functions are dominant [8, 15, 16].

Hh signaling is important for maintenance of postnatal cartilage. A recent study reported that activation of Hh signaling is associated with human OA cartilage and surgically induced OA in mice [18]. Furthermore, OA symptoms in the latter were alleviated by a Hh signaling antagonist [18], suggesting a strong correlation between up-regulation of Hh signaling and OA progression. Potential mechanisms for the up-regulation of Hh signaling in OA were not discussed.

Here we report that depletion of primary cilia in mouse chondroyctes via Cre-Lox recombination of the Ift88 gene results not only in disorganization and eventual loss of growth plate [10], but also abnormal development and maintenance of articular cartilage. Mutant articular cartilage showed signs of early OA, including up-regulation of Mmp13, Adamts5, ColX, and Runx2 mRNA, reduced stiffness, and up-regulation of Hh signaling. We also demonstrate an accumulation of Gli3 in the full-length activator form in mutant cartilage. We propose that the altered Gli3 repressor to activator ratio in mutant cartilage results in high Hh signaling subsequently leading to OA symptoms.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Ift88fl/fl mice were obtained from Dr. Bradley K Yoder, University of Alabama at Birmingham [9]. Mice expressing Cre recombinase under the control of Type II Collagen promoter (Col2aCre) [19] were obtained from Jackson labs (stock No. 003554). Experimental crosses were set up as Col2aCre;Ift88fl/wt X Ift88fl/fl. No haploinsufficiency was observed on the level of protein expression (data not shown); therefore, Col2aCre;Ift88fl/wt or Ift88fl/fl littermates were used as controls to compare with Col2aCre;Ift88fl/fl mutants.

Histology and immunostaining

Hind limbs from mice at varying ages were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and placed in decalcification buffer (100mM Tris, pH 7.5, 0.1% DEPC, 10% EDTA-4 Na, and 7.5% polyvinyl pyrolidione (PVP)) on a shaker at 4°C for 21 days followed by (100mM Tris, pH 7.5, 5% sucrose, and 10% PVP) for another 7 days before embedding in OCT. Sections were cut at a thickness of 10μm (20μm for primary cilia staining) and mounted on Superfrost Plus slides (Fischer). For histological analysis, sections were stained with Hematoxylin/Eosin, Sirius Red, Safranin O and Toluidine Blue as described (http://www.ihcworld.com/). For immunofluorescent staining, mouse anti-γ-tubulin antibody (Sigma, T6557), rabbit anti-Arl13b ([20]; from Dr. Tamara Caspary, Emory University), rabbit anti-Aggrecan antibody (Chemicon AB1031), rabbit anti-Collagen type X (from Dr. Danny Chan, University of Hong Kong) and mouse anti-Collagen type II antibody (clone 2B1.5, Thermo Scientific MS-235) were used. Biotinylated anti-mouse IgG or biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG were used as secondary antibody. Cy3 or Alexa488 conjugated streptavidin was used as fluorophore. Avidin/Biotin blocking kit (Vector Labs) was used when performing double staining. YOPRO®-3 iodide (612/631) (Invitrogen) and DAPI were used for nuclear counter staining. For Runx2 staining, mouse anti-Runx2 antibody (clone 8G5, MBL International D130-3), biotinylated anti-mouse IgG, Vectastain ABC systems (Vector Laboratories), and DAB substrate were used. Methyl green was used for counter staining. The pictures of primary cilia were taken by confocal microscope (Nikon Eclipse TE 2000U, with a Perkin Elmer Ultraview spinning disc confocal head). Labeling of fragmented DNA in apoptotic cells was done by using TACS®2 TdT apoptosis detection kit (Trevigen).

Indentation test

Mice were sacrificed at 2 month of age and tibiae were extracted from right hindlimbs and stored at 4°C in PBS until tested. Mechanical testing was done within 48 hours. Articular cartilage was tested by indentation on a computer controlled electromechanical test system (Bose LM1 electroforce test bench, Eden Prairie, MN) fitted with a 250g load cell (Sensotec, Columbus, OH). The tibiae were embedded in bone cement, mounted in a custom-made specimen chamber and immersed in phosphate buffered saline maintained at room temperature. The specimen chamber was fixed on a custom made X-Y stage with micrometer control and a 360° rotating arm. A stress relaxation test was performed using a cylindrical, impervious, plane-ended indenter (178μm diameter; custom made) positioned perpendicular to the cartilage surface using a stereomicroscope. Initially, a tare load of 0.05g was applied and the cartilage was allowed to come to equilibrium for 200 seconds. The cartilage surface was displaced by 20μm in four steps of 5μm each with a relaxation time of 200 seconds incorporated in between every step. Load values measured instantaneously after every displacement step and at the end of every 200 seconds equilibrium were converted to stress values while strain values were calculated using the displacement steps and cartilage thickness. Stress-strain curve were plotted separately for both instantaneous and equilibrium values and the stiffness was determined as the slope of the respective curves. Stiffness from instantaneous and equilibrium values were called instantaneous and equilibrium stiffness respectively [21, 22]. After stress relaxation, the indenter was replaced with a sharp tungsten needle (1μm tip radius) and pushed through the cartilage surface. Articular cartilage thickness was determined by changes noted in the load-displacement curve at the surface and tidemark.

RNA extraction and real time RT-PCR analysis

Articular cartilage from knee joints of 2 month old animals was dissected and used for RNA extraction. Briefly, the cartilage from distal femur and proximal tibia was sliced from subchondral bone using a surgical blade. Needle and syringe were used to flush out the bone marrow. The cartilage pieces were digested in DMEM/F12 (Gibco) with 3mg/mL Collagenase D (Roche) at 37°C for 3 hours. The chondrocytes were collected by centrifuging the medium at 500g for 5 minutes, and resuspended in Trizol® reagent (Invitrogen). RNA was extracted according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and treated with DNaseI before real time RT-PCR analysis. All the primers for real time RT-PCR were designed so that the product would cross intron boundaries (Table 1).

Table 1.

Primer sequences for real time RT-PCR.

| Bcl2 forward | TTGTGGCCTTCTTTGAGTTCGGTG |

| Bcl2 reverse | AATCAAACAGAGGTCGCATGCTGG |

| Mmp13 forward | CTTCTTCTTGTTGAGCTGGACTC |

| Mmp13 reverse | CTGTGGAGGTCACTGTAGACT |

| Adamts5 forward | TGTGAGAACTGGATGTGACG |

| Adamts5 reverse | ACTGTCGGACTTTTATGTGGG |

| ColX forward | ACCAAACGCCCACAGGCATAAA |

| ColX reverse | ACCAGGAATGCCTTGTTCTCCT |

| Runx2 forward | CACTGCCACCTCTGACTTC |

| Runx2 reverse | ATTCGTGGGTTGGAGAAGC |

| Nckx3 forward | TCGTCCCATCCTTGGAAAAG |

| Nckx3 reverse | AACTCCCACATCACCCTTTG |

| Ptch1 forward | AAAGAACTGCGGCAAGTTTTTG |

| Ptch1 reverse | CTTCTCCTATCTTCTGACGGGT |

| Gli1 forward | CCAAGCCAACTTTATGTCAGGG |

| Gli1 reverse | AGCCCGCTTCTTTGTTAATTTGA |

| beta-2 microglobulin (β2m) forward | TTCTGGTGCTTGTCTCACTGA |

| β2m reverse | CAGTATGTTCGGCTTCCCATTC |

QuantiFast® SYBR Green RT-PCR kit (Qiagen) and LightCycler® 480 (Roche) were used to perform real time RT-PCR. RNA samples from 3 controls and 3 mutants were analyzed in tripicate. Data analysis was done using REST 2009 software (Qiagen; [23]), which allows statistical comparison of gene expression in groups of controls and mutants. All the genes were normalized to the expression of β2m. Data were presented by whisker-box plots. Top and bottom whiskers represented the maximum and minimum observations, respectively, and the box represented the middle 50% of observations. Median was shown by a dotted line.

Western blotting

The epiphyseal cartilage was isolated from postnatal 7 day-old mice and used for protein extraction. Limbs were dissected and digested in DEME/F12 with 2mg/mL pronase (Roche) and 2mg/mL Collagenase D at 37°C for 1 hour. Epiphyseal cartilage was removed and digested in DMEM/F12 with 3mg/mL Collagenase D at 37°C for another 3 hours. Cells were collected by passing the digesting medium through 40μm cell strainer and centrifuge at 500g for 5 minutes. Cell pellet was resuspended in RIPA buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors, and sonicated for 10 seconds. After centrifuge at 12000g, 4°C for 10 minutes, the supernatant was collected and 100μg protein from each sample was used for western blotting. Goat polyclonal anti-Gli3 antibody (R&D) was used to detect both Gli3 full length and processed repressor forms. The ratio of Gli3 repressor to Gli3 full length was quantified using Kodak Molecular Imaging software.

Statistical Methods

For measurements of primary cilia frequency, cell number, cell size, cartilage stiffness, and cartilage thickness, statistical analysis was performed by Student’s T-test. A p-value of less than 0.05 was determined to be significant.

Combined real time RT-PCR data from the three biological replicates (each done with three technical replicates) was analyzed using REST software, which normalizes results and calculates the relative fold difference in gene expression, confidence intervals and statistical significance across experiments using an integrated randomization and bootstrapping algorithm [23]. REST software enables statistical comparison of different genes between multiple groups. Instead of a parametric test, REST software performs radomisation tests (at least 2000 randomisations) on group-wise data and calculates expression ratio of target genes as compared to a reference gene along with the p-values. Differences were considered significant for p-value <0.05.

Result

Depletion of primary cilia on chondrocytes results in abnormal articular cartilage

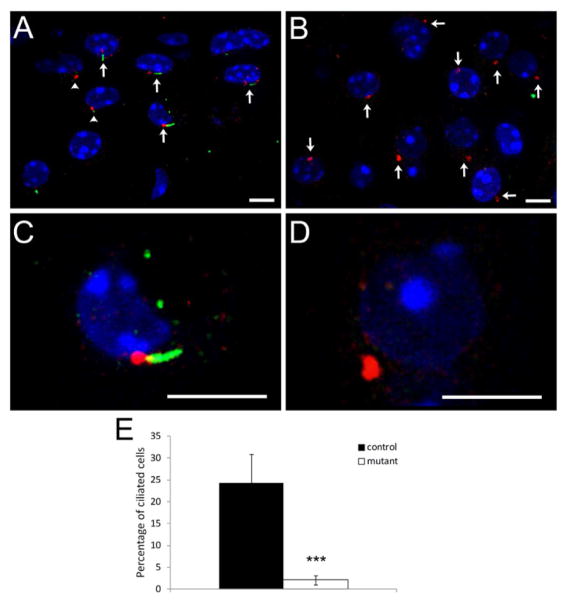

Depletion of primary cilia in articular cartilage was confirmed by immunofluorescent staining on knee joints from 2 month-old mice. Primary cilia were seen as either green short lines or concentrated spots, and cilia basal bodies were seen as red spots of γ-tubulin (Figs. 1A, C). In Col2aCre;Ift88fl/fl articular cartilage, primary cilia were absent, but cilia basal bodies were still intact (Figs. 1B, D). Depletion of primary cilia in mutants was also demonstrated by calculating the percentage of cells with cilia in tissue sections (Fig. 1E). In control, cilia were present on 24.1 ± 7.5% cells, whereas in mutant, 2.1± 1.1% of the cells had visible cilia, indicating that most primary cilia were deleted in mutant cartilage (t-test, p=0.0002).

Figure 1. Primary cilium was deleted in Col2aCre;Ift88fl/fl articular cartilage.

Sections from 2 month old control or Col2aCre;Ift88fl/fl mutant mice were used for immunostaining of primary cilia (A–D). Primary cilia were stained with anti-Arl13b antibody (green), and the basal bodies were stained with anti-γ-tubulin antibody (red). The nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Primary cilia were seen as either green dots (arrowheads) or short green lines (arrows) next to the red basal bodies in control articular cartilage. In mutant (B), primary cilia were deleted; however, the basal bodies were still intact (arrows). (C) Close view of primary cilium, which is absent in mutant (D). (Scale bar in A–D: 5μm). (E) Percentage of ciliated cells in control and mutant articular cartilage. Five microscopic fields were randomly chosen along tibial cartilage, and there were least 40 cells in each field. In control, 24.1 ± 7.5% cells were ciliated, whereas in mutant, there were only 2.1± 1.1% ciliated cells, indicating that most primary cilia were deleted in mutant cartilage (t-test, p=0.0002).

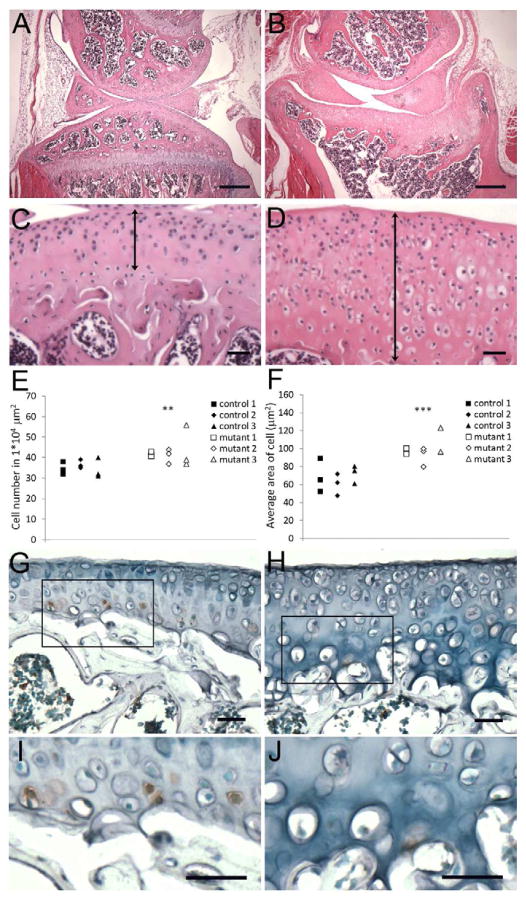

Tissue morphology was compared between control and mutant mice using Hematoxylin/Eosin staining (Figs. 2A–D). At postnatal 7 days, mutant mice demonstrated alterations in growth plate architecture [10]. We also noticed delayed formation of the secondary ossification center (SOC) and increased hypertrophic area within SOC in 2 week-old mice, likely due to failure to remove hypertrophic cells (data not shown). At 2 months of age, articular cartilage was fully developed in both control and mutant mice (Figs. 2A, B). However, the shape of joints in mutants was altered. The femoral head in mutants did not show a smooth round surface as observed in control mice, and the tibial head was bowl shape instead of a plateau (Fig. 2B). The mutant articular cartilage also showed increased thickness (Figs. 2C, D, double arrows, and Fig. 3G), cell density (Fig. 2E) and cell size (Fig. 2F). The increased thickness of the articular cartilage was likely due to reduced apoptosis, as measured by TUNEL staining (Figs. 2G–J). In control cartilage, apoptosis was detected in cells in the deep calcified layer (Figs. 2G, I), whereas TUNEL staining was not detected in mutant cartilage (Figs. 2H, J). Real time RT-PCR indicated an increase in expression of the anti-apoptotic protein, Bcl-2, (1.6 fold, p= 0.012) further suggesting apoptosis was inhibited in the mutants. We did not observe changes in proliferation at any age tested (data not shown).

Figure 2. Deletion of primary cilia in chondrocytes results in abnormal articular cartilage.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining of sections from 2 month old control (A, C) and mutant (B, D) articular cartilage. The proximal tibia of mutant mice showed abnormal shape (B) and thicker cartilage (D, double arrow), compared to control mice (A, C). (E, F) Cell number and cell size were increased in mutant articular cartilage. The cell density (E) of articular cartilage from proximal tibia was compared in 3 controls and 3 mutants. The cell number was counted in three microscopic fields (one field = 1*104 μm2), which spanned the articular surface to the deep zone. Data is presented as individual points from each field from each mouse. An increase in cell density was observed in mutant articular cartilage (**t-test, p=0.005). (F) Cell size was measured using Olympus imaging software (cellSens® standard). Each data point represents the average cell size in each field counted in (E). The result indicated that cell size was increased (***t-test, p=0.0001) in mutant articular cartilage. Apoptotic cells were measured using the TUNEL assay on sections from control (G, I) and Col2aCre;Ift88fl/fl (H, J) knee joints. I and J are high magnification images from the boxed area in G and H, respectively. Apoptosis was seen in hypertrophic cells within the calcified zone in control articular cartilage; however, no apoptosis was detected in the corresponding area in mutants. (Scale bar in A and B: 200 μm; in C, D, and G–J: 20 μm).

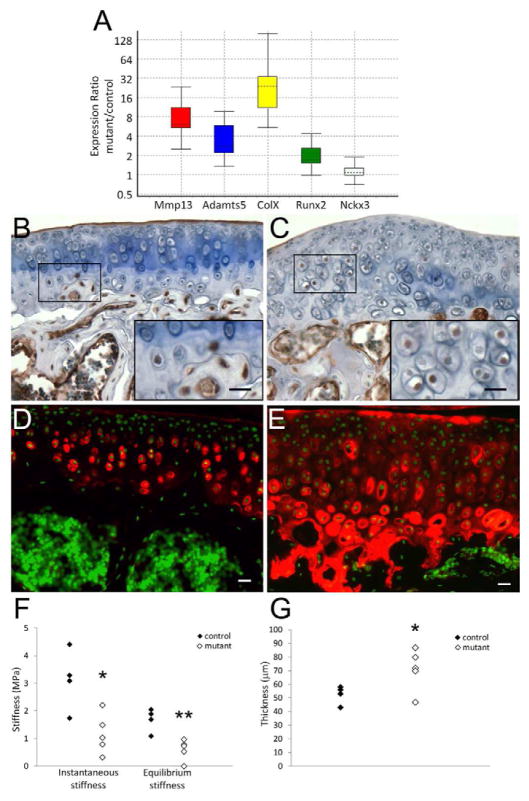

Figure 3. Markers of osteoarthritis are increased in Col2aCre;Ift88fl/fl articular cartilage.

(A) RNA was isolated from articular cartilage of 2 month old mice and markers of osteoarthritis Mmp13, Adamts5, ColX and Runx2 were determined by real time RT-PCR. The markers were all increased in mutant articular cartilage (n=3 separate mice). The expression of Nckx3 (sodium/potassium/calcium exchanger 3) was used as a control gene and was not altered in mutants. Data are presented by whisker-box plots. Top and bottom whiskers represent the maximum and minimum observations, respectively, and the box represents the middle 50% of observations. Median is shown by a dotted line. Runx2 (B, C) and type X Collagen (D, E) expression were visualized by immunostaining. In control articular cartilage, Runx2 was expressed in chondrocytes in the calcified region (B, bottom right: magnified box area), and type X Collagen was expressed in hypertrophic area (D). In mutant articular cartilage, Runx2 expression was seen in cells in the midzone (C, bottom right: magnified box area), and type X Collagen was seen throughout the cartilage (E). (Scale bar in B–E: 10 μm). (F, G) Mechanical properties were altered in Col2aCre;Ift88fl/fl articular cartilage compared to controls. Mechanical properties were tested on articular cartilage of tibiae from 2 month old mice. Individual data points from 4 controls and 5 mutants are presented. Instantaneous and equilibrium stiffness were significantly lower in mutant cartilage (F) (t-test, *p=0.032 and **p=0.004, respectively). The thickness was also measured (G), showing an increase in mutants (*t-test, p=0.028).

Col2aCre;Ift88fl/fl mice show OA symptoms

The histological changes observed in mutant articular cartilage suggested that the cartilage may acquire an osteoarthritis-like phenotype. Expression of markers for OA was measured by real time RT-PCR. Data showed that the expressions of Mmp13, Adamts5, Col10, and Runx2 were all increased in mutant articular cartilage (Fig. 3A). Runx2 and Collagen Type X were also localized by immunostaining (Figs. 3B–E). In control mice, Runx2 was only localized to cells in the calcified region of the cartilage as well as in the subchondral bone; Collagen Type X was found in the deep layers of the cartilage and was predominantly pericellular. In mutant mice, Runx2 and Collagen Type X were localized in cells spanning the thickness of the articular cartilage. In addition, Collagen Type X was localized to the cartilage matrix in between the cells. The up-regulation of Collagen Type X suggested inappropriate hypertrophic differentiation in the cartilage consistent with the observation of increased cell size. Articular cartilage is normally maintained in a prehypertrophic state and hypertrophy is one of the signs of OA. We also performed an indentation test to measure the mechanical properties of the articular cartilage. The instantaneous and equilibrium stiffness were measured by a micro-indenter with four-step displacement. The result showed that both instantaneous and equilibrium stiffness were significantly decreased in mutant articular cartilage relative to controls (Fig. 3F, G).

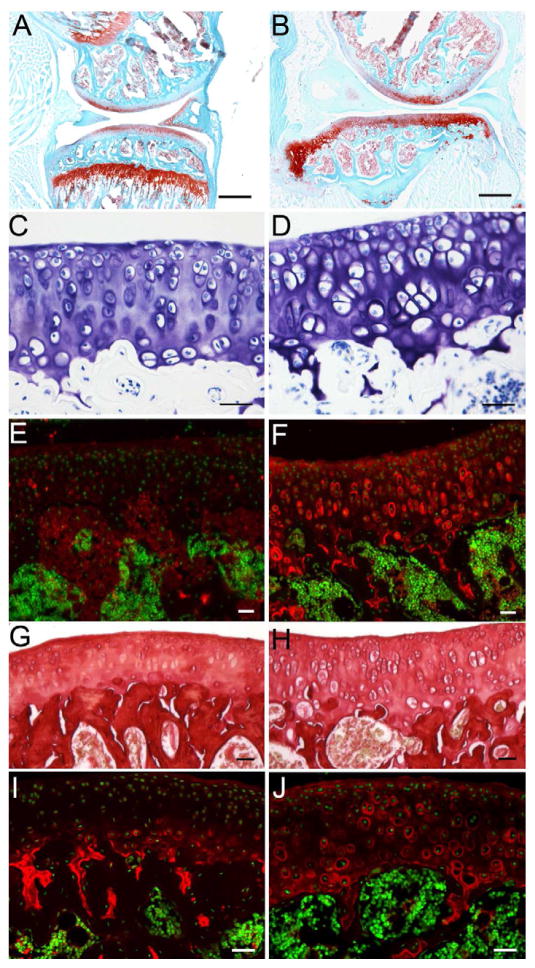

Increased cellular anabolic rate is a feature of early OA and represents an attempt by chondrocytes to repair cartilage [24–26]. Proteoglycans and Collagens were stained by Safranine O, Toluidine Blue, and Sirius Red (Fig. 4A, B, C, D G, H). Safranine O and Toluidine Blue showed increased staining in mutant articular cartilage suggesting and increase in proteoglycan content (Fig 4A–D). Likewise, immunostaining for Aggrecan demonstrated increased pericelluar and interterritorial staining throughout the mutant cartilage. (Fig. 4E, F). The overall Sirius Red staining appeared similar between control and mutant articular cartilage (Fig. 4G, H). However, immunoflourescent staining using an antibody to Collagen Type II indicated an increase in pericellular Collagen staining (Fig. 4I, J). With the use of the above staining, we determined the OA status in mutant mice using the grading system developed by [27]. Mutant cartilage at 2 months (Figures 3 and 4) demonstrated intact articular surface, increased proteoglycan staining, increased hypertrophic cells, and > 50% involvement. According to the grading system, cartilage from 2 month old mutants was classified at Grade 1; Stage 4 (Mankin score = 4).

Figure 4. Expressions of matrix proteins are increased in Col2aCre;Ift88fl/fl articular cartilage.

The expression of matrix proteins was examined by histochemistry and immunostaining. Proteoglycans were examined by Safranine O (A, B) and Toluidine Blue staining (C, D). The staining showed an increase in pericellular and interterritorial proteoglycan content, which may due to increased expression of Aggrecan protein, as shown in (E, F). The pericellular staining of Aggrecan was also increased in mutant, compared to control. (G, H) Collagens were stained with Sirius Red. The staining showed more pericellular staining in the mutant articular cartilage, compared to control. (I, J) Immunostaining of Type II Collagen indicates that the increase in pericelluar collagen content may due to the increased expression of Type II Collagen. Scale bars in A, B equal 200 μm. Scale bars in C–J equal 20 μm.

Hh signaling is up-regulated in articular cartilage of Col2aCre;Ift88fl/fl mice

Primary cilia can regulate both the ligand-mediated activation and ligand-independent repression of Hh signaling depending on the cell context (Reviewed in [8]. It was recently shown that up-regulation of Hh signaling is associated with inappropriate hypertrophic differentiation and OA [18]. Therefore, we compared the level of Hh signaling in articular cartilage from control and Col2aCre;Ift88fl/fl mice. Expressions of downstream targets and markers of Hh signaling, Ptch1 and Gli1, were examined by real time RT-PCR (Fig. 5A). Both Ptch1 and Gli1 were increased in mutant cartilage suggesting over-active Hh signaling in the absence of primary cilia.

Figure 5. Hedgehog signaling is up-regulated Col2aCre;Ift88fl/fl articular cartilage.

(A) The expression of downstream targets of Hedgehog signaling, Ptch1 and Gli1, were determined in RNA samples from articular cartilage. The result indicated that hedgehog signaling was up-regulated in mutant articular cartilage relative to controls. Data are presented by whisker-box plots. Top and bottom whiskers represent the maximum and minimum observations, respectively, and the box represents the middle 50% of observations. Median is shown by a dotted line. (B) Gli3 full length and processed repressor forms were determined in postnatal 7 days epiphyseal cartilage from 3 control and 2 mutant mice using western blot. The data showed an accumulation of the full length Gli3 form, resulting in alterations in the ratio of the full length to repressor forms in the absence of primary cilia. Western blot also confirmed reduced expression of Ift88 in the mutant cells. GAPDH was used as a loading control.

The Gli3 repressor is a key regulator of Hh signaling in the skeleton [28, 29]. Moreover, mice with genetic ablation of Gli3 showed high frequency of synovial chondromatosis [30], in which expressions of Ptch1 and Gli1 were elevated in metaplastic cartilage nodules. Therefore, we compared the levels of Gli3 protein in control and cilia mutant cartilage. In epiphyseal cartilage of postnatal 7 day Col2aCre;Ift88fl/fl mice, there was an accumulation of full length Gli3 (Fig. 5B), which resulted in a reduced ratio of Gli3 repressor to Gli3 activator relative to controls. We propose that primary cilia are required for maintaining a proper ratio of Gli3 repressor to activator in cartilage, and that OA-related symptoms are at least in part due to defective Gli3 processing and inappropriate activation of Hh signaling.

Discussion

The formation of articular cartilage occurs in the postnatal stage of long bone development when the secondary ossification center forms in the epiphyseal cartilage and articular cartilage is separated from the growth plate. The growth plate is a transient cartilage that is responsible for longitudinal growth of long bones. Articular cartilage is a permanent cartilage that serves as a cushion within the joints. While many studies have focused on the degeneration of articular cartilage, little is known about its development. In this study, we show that primary cilia are depleted in the articular cartilage of Col2aCre;Ift88fl/fl mice, which results in abnormal development of articular cartilage. The shape of the knee joint is altered. The thickness and cell density within the cartilage layer are both increased in mutants, likely due to reduced apoptosis. Mutant articular cartilage also shows symptoms of inappropriate hypertrophic differentiation and OA, including reduced matrix stiffness and increased expressions of markers of hypertrophic differentiation: Mmp13, Adamts5, ColX, and Runx2. OA was recently associated with increased Hh signaling [18] and Col2aCre;Ift88fl/fl mice demonstrate increased Hh signaling and reduced Gli3 repressor to activator ratio. We propose that OA symptoms in Col2aCre;Ift88fl/fl mice are due to the reduced ratio of Gli3 repressor over the full-length Gli3 activator resulting in increased Hh signaling.

Unlike growth plate cartilage, which stops activity after adolescence, articular cartilage is a permanent cartilage functioning throughout the postnatal life. Homeostasis of articular cartilage is highly regulated to ensure cartilage integrity. In normal articular cartilage, the rates of cell differentiation and matrix turnover are extremely low compared to that of a metabolically active growth plate. During progression of OA, however, chondrocytes acquire phenotypes of growth plate chondrocytes including an increase in both anabolic and catabolic agents, and inappropriate hypertrophic differentiation [24–26]. The early stages of OA are often associated with increased expression of ECM proteins like Aggrecan and Collagen Type II, representing an attempt by chondrocytes to repair their environment. Here we show increased staining for Collagen Type II and Aggrecan in mutant cartilage at two months of age. We also show an increase in catabolic agents, MMP13 and Adamts5, as well as markers of hypertrophic differentiation including Type X Collagen and Runx2 in Col2aCre;Ift88fl/fl articular cartilage. Increased expression of the anti-apoptotic factor Bcl-2, as a result of chondrocyte activation, is also featured in early stage of OA [31, 32] and there was less apoptotic activity and increased expression of Bcl-2 cilia mutants. Together the results suggest that Col2aCre;Ift88fl/fl mice develop an early OA-like condition.

Alterations in mechanical properties of cartilage have been observed in animal models of OA [33]. In the present study, stress relaxation tests performed with an impervious indenter revealed a decrease in the stiffness of Col2aCre;Ift88fl/fl cartilage. Though immunostaining showed an increase in Aggrecan and Collagen Type II, we do not know how the collagen fibril orientation or the collagen-proteoglycan network, which can influence the mechanical integrity of the tissue, was affected [21, 33, 34]. Changes in chondrocyte size or shape and cartilage thickness, as observed by histology and needle method respectively, could also have an impact on mechanical properties. Additional studies are required to delineate which of these factors directly affected the mechanical properties of articular cartilage in the Col2aCre;Ift88fl/fl mutants.

Col2aCre;Ift88fl/fl mice show alterations in cartilage morphology around postnatal day 7 when they start to walk and receive significant loading on joints. Therefore, it is possible that the cartilage phenotype observed is a result of alterations in the transmission of mechanical signals through primary cilia. A role for chondrocyte primary cilia in sensing mechanical signals has been proposed by observations of cilia orientation and projection within the cartilage matrix [13, 35–38]. In articular cartilage, primary cilia in the superficial layer point away from the articular surface while primary cilia on chondrocytes in the mid or deep zone of load bearing joints can be pointed towards the articular surface or towards the subchondral bone [37]. Orientation is not consistent in non-load bearing cartilages. Furthermore, mechanical loading in vitro was shown to result in alterations in the length of primary cilia [39]. Disruptions to primary cilia function have been shown to result in abnormalities in weight bearing cartilage [10, 38, 40]. A recent study indicated that the incidence and length of primary cilia are increased in OA tissue but the function of the primary cilia in OA progression was not addressed [11]. The question of whether chondrocyte primary cilia sense mechanical signals and the consequences of loss of such signals for OA are still unclear.

Excess Hh signaling and inappropriate hypertrophic differentiation can lead to OA, as recently shown [18]. In embryonic growth plate, Hh inhibits hypertrophic differentiation though regulation of PTHrP expression. In contrast, in post-natal cartilage, a PTHrP-independent pathway becomes dominant and Hh signaling promotes chondrocyte hypertrophy [41]. One way to maintain a low level of Hh signaling is with a high ratio of Gli3 repressor to activator. Gli3 has been shown to repress Ptc1 and Gli1 and other down stream targets of Hh in several model systems [15, 28, 29, 42]. Mice carrying mutation of Gli3xt/xt have reduced expression of Gli3 and a phenotype resembling overactive Hh signaling [43]. Gli3xt/xt mice also develop synovial chondromatosis, in which Gli1 and Ptch1 expressions are elevated in metaplastic cartilage nodules [30]. Together the studies suggest that a high ratio of Gli3 repressor to activator activity could help to prevent osteoarthritis. Consistent with this hypothesis, we show that loss of primary cilia in articular cartilage leads to low Gli3 repressor/activator ratio, increased Hh signaling, and predisposition to OA related symptoms. A direct test of the role of Gli3 repressor in mediating the consequences of cilia depletion would be to misexpress a constitutive Gli3 repressor in Col2aCre;Ift88fl/fl cartilage and see if development of OA-like symptoms is blocked.

Indian Hedgehog (Ihh) ligand is a marker of cells that have been committed to hypertrophy. It is likely that Ihh expression is increased in Col2aCre;Ift88fl/fl cartilage as a consequence of the increased hypertrophic differentiation observed. This increase in ligand could cause an indirect increase in Hh signaling; however, it is unlikely that the mutant chondrocytes, which lack cilia, would respond to an increase in Hh ligand. In the presence of Hh ligand, ligand binds to its receptor Ptc on the cell surface. This allows derepression of Smo, which moves into the primary cilia and releases Glis from the inhibitor, Suppressor of fused [44]. In addition to loss of the Gli3 repressor, in the absence of primary cilia, ligand-dependent Hh signaling cannot be activated (Reviewed in [8]. For example, cilia depleted limb mesenchyme does not respond to exogenous Shh treatment [15]. It is not clear what happens to full length Gli3 activator in the absence of the cilium. There are two possibilities for increased Ptc1 and Gli1 expression in Col2aCre;Ift88fl/fl cartilage: 1- The full length Gli3 can go to the nucleus and activate transcription or 2- The absence of the repressor is enough to derepress (thereby increase) expression of Ptc1 and Gli1 similar to what occurs in chondromatomas in Gli3xt/xt mice.

In summary, our study shows that primary cilia are important for development and maintenance of the articular cartilage and regulation of Hh signaling. We propose that Gli3 repressor is a key regulator of Hh signaling in articular cartilage and the proper ratio of Gli3 repressor/activator depends on the function of primary cilia. The results suggest that depletion of primary cilia results in a reduced ratio of Gli3 repressor/activator, which at least in part contributes to OA symptoms in Col2aCre;Ift88fl/fl mice.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Bradley Yoder, Department of Cell Biology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, for providing the Ift88fl/fl mice. We thank Zak Kosan, Department of Cell Biology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, for help with the confocal microscope. We thank Dr. Alan Eberhardt, Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Alabama at Birmingham for help setting up the microindentation protocol.

Funding Source.

Funding for this study was through NIH grants AR055110 and AR053860 to RS. The funding agency was not involved in design, interpretation, or writing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing Interests.

None of the authors have any conflicts to report.

Author Contributions.

C-F. C. contributed to design of the study, acquisition and analysis of the data as well as drafting the manuscript.

G.R. contributed to design of the study, acquisition and analysis of the data as well as drafting the manuscript.

R.S. contributed to the conception and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of the data, critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content, as well as obtaining funding.

All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pedersen LB, Rosenbaum JL. Intraflagellar transport (IFT) role in ciliary assembly, resorption and signalling. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2008;85:23–61. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(08)00802-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ishikawa H, Marshall WF. Ciliogenesis: building the cell’s antenna. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:222–234. doi: 10.1038/nrm3085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berbari NF, O’Connor AK, Haycraft CJ, Yoder BK. The primary cilium as a complex signaling center. Curr Biol. 2009;19:R526–535. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goetz SC, Anderson KV. The primary cilium: a signalling centre during vertebrate development. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:331–344. doi: 10.1038/nrg2774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma N, Berbari NF, Yoder BK. Ciliary dysfunction in developmental abnormalities and diseases. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2008;85:371–427. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(08)00813-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tobin JL, Beales PL. The nonmotile ciliopathies. Genet Med. 2009;11:386–402. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181a02882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Serra R. Role of intraflagellar transport and primary cilia in skeletal development. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2008;291:1049–1061. doi: 10.1002/ar.20634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haycraft CJ, Serra R. Cilia involvement in patterning and maintenance of the skeleton. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2008;85:303–332. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(08)00811-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haycraft CJ, Zhang Q, Song B, Jackson WS, Detloff PJ, Serra R, et al. Intraflagellar transport is essential for endochondral bone formation. Development. 2007;134:307–316. doi: 10.1242/dev.02732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song B, Haycraft CJ, Seo HS, Yoder BK, Serra R. Development of the post-natal growth plate requires intraflagellar transport proteins. Dev Biol. 2007;305:202–216. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGlashan SR, Cluett EC, Jensen CG, Poole CA. Primary cilia in osteoarthritic chondrocytes: from chondrons to clusters. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:2013–2020. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poole CA, Jensen CG, Snyder JA, Gray CG, Hermanutz VL, Wheatley DN. Confocal analysis of primary cilia structure and colocalization with the Golgi apparatus in chondrocytes and aortic smooth muscle cells. Cell Biol Int. 1997;21:483–494. doi: 10.1006/cbir.1997.0177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jensen CG, Poole CA, McGlashan SR, Marko M, Issa ZI, Vujcich KV, et al. Ultrastructural, tomographic and confocal imaging of the chondrocyte primary cilium in situ. Cell Biol Int. 2004;28:101–110. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corbit KC, Aanstad P, Singla V, Norman AR, Stainier DY, Reiter JF. Vertebrate Smoothened functions at the primary cilium. Nature. 2005;437:1018–1021. doi: 10.1038/nature04117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haycraft CJ, Banizs B, Aydin-Son Y, Zhang Q, Michaud EJ, Yoder BK. Gli2 and Gli3 localize to cilia and require the intraflagellar transport protein polaris for processing and function. PLoS Genet. 2005;1:e53. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu A, Wang B, Niswander LA. Mouse intraflagellar transport proteins regulate both the activator and repressor functions of Gli transcription factors. Development. 2005;132:3103–3111. doi: 10.1242/dev.01894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huangfu D, Anderson KV. Signaling from Smo to Ci/Gli: conservation and divergence of Hedgehog pathways from Drosophila to vertebrates. Development. 2006;133:3–14. doi: 10.1242/dev.02169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin AC, Seeto BL, Bartoszko JM, Khoury MA, Whetstone H, Ho L, et al. Modulating hedgehog signaling can attenuate the severity of osteoarthritis. Nat Med. 2009;15:1421–1425. doi: 10.1038/nm.2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ovchinnikov DA, Deng JM, Ogunrinu G, Behringer RR. Col2a1-directed expression of Cre recombinase in differentiating chondrocytes in transgenic mice. Genesis. 2000;26:145–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caspary T, Larkins CE, Anderson KV. The graded response to Sonic Hedgehog depends on cilia architecture. Dev Cell. 2007;12:767–778. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hyttinen MM, Toyras J, Lapvetelainen T, Lindblom J, Prockop DJ, Li SW, et al. Inactivation of one allele of the type II collagen gene alters the collagen network in murine articular cartilage and makes cartilage softer. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:262–268. doi: 10.1136/ard.60.3.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alexopoulos LG, Youn I, Bonaldo P, Guilak F. Developmental and osteoarthritic changes in Col6a1-knockout mice: biomechanics of type VI collagen in the cartilage pericellular matrix. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:771–779. doi: 10.1002/art.24293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pfaffl MW, Horgan GW, Dempfle L. Relative expression software tool (REST) for group-wise comparison and statistical analysis of relative expression results in real-time PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e36. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.9.e36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aigner T, Soder S, Gebhard PM, McAlinden A, Haag J. Mechanisms of disease: role of chondrocytes in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis--structure, chaos and senescence. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2007;3:391–399. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heinegard D, Saxne T. The role of the cartilage matrix in osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;7:50–56. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dreier R. Hypertrophic differentiation of chondrocytes in osteoarthritis: the developmental aspect of degenerative joint disorders. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:216. doi: 10.1186/ar3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pritzker KP, Gay S, Jimenez SA, Ostergaard K, Pelletier JP, Revell PA, et al. Osteoarthritis cartilage histopathology: grading and staging. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14:13–29. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hilton MJ, Tu X, Cook J, Hu H, Long F. Ihh controls cartilage development by antagonizing Gli3, but requires additional effectors to regulate osteoblast and vascular development. Development. 2005;132:4339–4351. doi: 10.1242/dev.02025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koziel L, Wuelling M, Schneider S, Vortkamp A. Gli3 acts as a repressor downstream of Ihh in regulating two distinct steps of chondrocyte differentiation. Development. 2005;132:5249–5260. doi: 10.1242/dev.02097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hopyan S, Nadesan P, Yu C, Wunder J, Alman BA. Dysregulation of hedgehog signalling predisposes to synovial chondromatosis. J Pathol. 2005;206:143–150. doi: 10.1002/path.1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iannone F, De Bari C, Scioscia C, Patella V, Lapadula G. Increased Bcl-2/p53 ratio in human osteoarthritic cartilage: a possible role in regulation of chondrocyte metabolism. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:217–221. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.022590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson EO, Charchandi A, Babis GC, Soucacos PN. Apoptosis in osteoarthritis: morphology, mechanisms, and potential means for therapeutic intervention. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2008;17:147–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knecht S, Vanwanseele B, Stussi E. A review on the mechanical quality of articular cartilage - implications for the diagnosis of osteoarthritis. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2006;21:999–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldring MB, Goldring SR. Osteoarthritis. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:626–634. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Poole CA, Flint MH, Beaumont BW. Analysis of the morphology and function of primary cilia in connective tissues: a cellular cybernetic probe? Cell Motil. 1985;5:175–193. doi: 10.1002/cm.970050302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Poole CA, Zhang ZJ, Ross JM. The differential distribution of acetylated and detyrosinated alpha-tubulin in the microtubular cytoskeleton and primary cilia of hyaline cartilage chondrocytes. J Anat. 2001;199:393–405. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2001.19940393.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Farnum CE, Wilsman NJ. Orientation of primary cilia of articular chondrocytes in three-dimensional space. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2011;294:533–549. doi: 10.1002/ar.21330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McGlashan SR, Haycraft CJ, Jensen CG, Yoder BK, Poole CA. Articular cartilage and growth plate defects are associated with chondrocyte cytoskeletal abnormalities in Tg737orpk mice lacking the primary cilia protein polaris. Matrix Biol. 2007;26:234–246. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McGlashan SR, Knight MM, Chowdhury TT, Joshi P, Jensen CG, Kennedy S, et al. Mechanical loading modulates chondrocyte primary cilia incidence and length. Cell Biol Int. 2010;34:441–446. doi: 10.1042/CBI20090094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaushik AP, Martin JA, Zhang Q, Sheffield VC, Morcuende JA. Cartilage abnormalities associated with defects of chondrocytic primary cilia in Bardet-Biedl syndrome mutant mice. J Orthop Res. 2009;27:1093–1099. doi: 10.1002/jor.20855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mak KK, Kronenberg HM, Chuang PT, Mackem S, Yang Y. Indian hedgehog signals independently of PTHrP to promote chondrocyte hypertrophy. Development. 2008;135:1947–1956. doi: 10.1242/dev.018044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hu MC, Mo R, Bhella S, Wilson CW, Chuang PT, Hui CC, et al. GLI3-dependent transcriptional repression of Gli1, Gli2 and kidney patterning genes disrupts renal morphogenesis. Development. 2006;133:569–578. doi: 10.1242/dev.02220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hui CC, Joyner AL. A mouse model of greig cephalopolysyndactyly syndrome: the extra-toesJ mutation contains an intragenic deletion of the Gli3 gene. Nat Genet. 1993;3:241–246. doi: 10.1038/ng0393-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zeng H, Jia J, Liu A. Coordinated translocation of mammalian Gli proteins and suppressor of fused to the primary cilium. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15900. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]