Abstract

This article is based on a consensus conference, which took place in Certosa di Pontignano, Siena (Italy) on March 7–9, 2008, intended to update the previous safety guidelines for the application of transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) in research and clinical settings.

Over the past decade the scientific and medical community has had the opportunity to evaluate the safety record of research studies and clinical applications of TMS and repetitive TMS (rTMS). In these years the number of applications of conventional TMS has grown impressively, new paradigms of stimulation have been developed (e.g., patterned repetitive TMS) and technical advances have led to new device designs and to the real-time integration of TMS with electroencephalography (EEG), positron emission tomography (PET) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Thousands of healthy subjects and patients with various neurological and psychiatric diseases have undergone TMS allowing a better assessment of relative risks. The occurrence of seizures (i.e., the most serious TMS-related acute adverse effect) has been extremely rare, with most of the few new cases receiving rTMS exceeding previous guidelines, often in patients under treatment with drugs which potentially lower the seizure threshold.

The present updated guidelines review issues of risk and safety of conventional TMS protocols, address the undesired effects and risks of emerging TMS interventions, the applications of TMS in patients with implanted electrodes in the central nervous system, and safety aspects of TMS in neuroimaging environments. We cover recommended limits of stimulation parameters and other important precautions, monitoring of subjects, expertise of the rTMS team, and ethical issues. While all the recommendations here are expert based, they utilize published data to the extent possible.

Keywords: Transcranial magnetic stimulation, TMS, rTMS, Safety

1. Introduction

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is a neurostimulation and neuromodulation technique, based on the principle of electromagnetic induction of an electric field in the brain. This field can be of sufficient magnitude and density to depolarize neurons, and when TMS pulses are applied repetitively they can modulate cortical excitability, decreasing or increasing it, depending on the parameters of stimulation, even beyond the duration of the train of stimulation. This has behavioral consequences and therapeutic potential.

The last decade has seen a rapid increase in the applications of TMS to study cognition, brain-behavior relations and the pathophysiology of various neurologic and psychiatric disorders (Wassermannn and Lisanby, 2001; Kobayashi and Pascual-Leone, 2003; Gershon et al., 2003; Tassinari et al., 2003; Rossi and Rossini, 2004; Leafaucheur, 2004; Hoffman et al., 2005; Couturier, 2005; Fregni et al., 2005a,b; Hallett, 2007; George et al., 2007; Málly and Stone, 2007; Rossini and Rossi, 2007; Devlin and Watkins, 2007; Ridding and Rothwell, 2007). In addition, evidence has accumulated that demonstrates that TMS provides a valuable tool for interventional neurophysiology applications, modulating brain activity in a specific, distributed, cortico-subcortical network so as to induce controlled and controllable manipulations in behavior.

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) has been found to be a promising noninvasive treatment for a variety of neuropsychiatric conditions (Devlin and Watkins, 2007; George et al., 2007; Aleman et al., 2007; Fregni and Pascual-Leone, 2007), and the number of applications continues to increase with a large number of ongoing clinical trials in a variety of diseases. Therapeutic utility of TMS has been claimed in the literature for psychiatric disorders, such as depression, acute mania, bipolar disorders, panic, hallucinations, obsessions/compulsions, schizophrenia, catatonia, post-traumatic stress disorder, or drug craving; neurologic diseases such as Parkinson's disease, dystonia, tics, stuttering, tinnitus, spasticity, or epilepsy; rehabilitation of aphasia or of hand function after stroke; and pain syndromes, such as neuropathic pain, visceral pain or migraine. A large industry-sponsored trial (O'Reardon et al., 2007) and a multi-center trial in Germany (Herwig et al., 2007) of rTMS in medication of refractory depression have been completed, and other appropriately controlled and sufficiently powered clinical trials of TMS are ongoing.

Most claims of therapeutic utility of TMS across conditions need further support and evidence-based clinical trial data, but the potential clinical significance is huge, affecting a large number of patients with debilitating conditions. A number of clinics have been set up worldwide offering TMS for treatment of various diseases, and rTMS is already approved by some countries for treatment of medication-refractory depression (i.e., Canada and Israel). In October 2008, a specific rTMS device was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in the United States for the treatment of patients with medication-refractory unipolar depression who have failed one good (but not more than one) pharmacological trial. It is reasonable to expect that the use of rTMS and its penetrance in the medical community will continue to increase across different medical specialties.

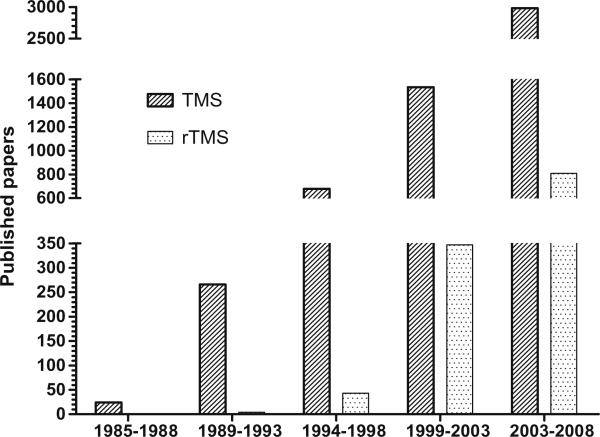

The number of laboratories using TMS for therapeutic or neuroscientific purposes, and consequently the number of healthy individuals and patients with various neurological or psychiatric diseases studied worldwide, has been increasing yearly for the past 20 years (Fig. 1). A further increase in the wide-spread use of TMS in medical therapeutic applications and research is expected. This makes the need for clear and updated safety guidelines and recommendations of proper practice of application critical.

Fig. 1.

Number of published papers per/year on Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation. Medline search updated to December 2008. Key words used are “Transcranial magnetic stimulation” (left bars) and “repetitive TMS” (right bars).

Current safety precautions and practice recommendations remain guided by the consensus conference held at the National Institutes of Health in June 1996 and summarized in Clinical Neurophysiology (Wassermannn, 1998). These recommendations were adopted with minor modifications by the International Federation for Clinical Neurophysiology (Hallett et al., 1999). Ethical considerations on the application of TMS to health and disease were initially dealt with by Green et al. (1997) during the early stages of rTMS testing, and more recently have been addressed by several publications (Wolpe, 2002; Mashour et al., 2005; Illes et al., 2006; Steven and Pascual-Leone, 2006). However, as previously mentioned, the use of TMS has grown dramatically in the past decade, new protocols of TMS have been developed, changes in the devices have been implemented, TMS is being increasingly combined with other brain imaging and neurophysiologic techniques including fMRI and EEG, and a growing number of subjects and patients are being studied with expanding numbers of longer stimulation sessions.

The safety of TMS continues to be supported by recent metaanalyses of the published literature (see Machii et al., 2006; Loo et al., 2008; Janicak et al., 2008), yet there is a clear need to revisit the safety guidelines, update the recommendations of practice, and improve the discussion of ethical aspect to be reflective of the expanding uses of these powerful and promising techniques. Towards this end, a consensus conference took place in Certosa di Pontignano, Siena (Italy) on March 7–9, 2008. As in the 1996 NIH Consensus Conference, the 2008 meeting brought together some of the leading researchers in the fields of neurophysiology, neurology, cognitive neuroscience and psychiatry who are currently using TMS for research and clinical applications. In addition, representatives of all TMS equipment manufacturers were invited and those of Magstim, Nexstim, and Neuronetics were present, along with representatives from various regulatory agencies and several basic and applied scientists, including physicists, and clinicians whose work has bearing on decisions regarding the safe and ethical use of rTMS. The present article represents a summary of the issues discussed and the consensus reached. It follows the outline of the 1998 consensus statement, addressing all issues raised previously to provide corrections or updates where necessary, and including various new topics needed given technological advances.

2. Principles of TMS

2.1. Nomenclature

TMS can be applied one stimulus at a time, single-pulse TMS, in pairs of stimuli separated by a variable interval, paired-pulse TMS, or in trains, repetitive TMS. Single-pulse TMS can be used, for example, for mapping motor cortical outputs, studying central motor conduction time, and studying causal chronometry in brain-behavior relations. In paired pulse techniques TMS stimulation can be delivered to a single cortical target using the same coil or to two different brain regions using two different coils. Paired pulse techniques can provide measures of intracortical facilitation and inhibition, as well as study cortico–cortical interactions. Pairing can also be with a peripheral stimulus and a single TMS stimulus, paired associative stimulation (PAS).

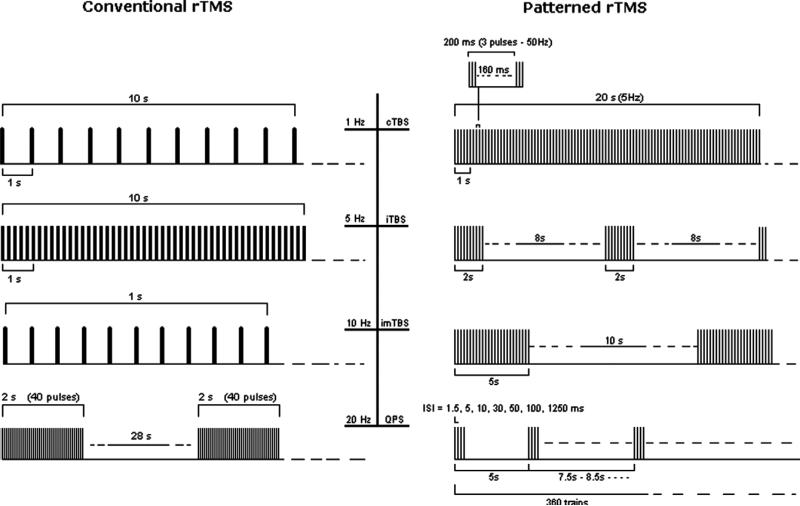

When multiple stimuli of TMS are delivered in trains, one can differentiate “conventional” and “patterned” protocols of repetitive stimulation. For conventional protocols (Fig. 2), there is universal agreement that the term ‘repetitive TMS’ (rTMS) has replaced earlier uses of the terms ‘rapid TMS’ and ‘rapid-rate TMS’ and should be used to refer to the application of regularly repeated single TMS pulses. The term ‘fast’ or ‘high-frequency’ rTMS should be used to refer to stimulus rates of more than 1 Hz, and the term ‘slow’ or ‘low-frequency’ rTMS should be used to refer to stimulus rates of 1 Hz or less. Such a classification is based on the different physiological effects and degrees of risk associated with low- and high-frequency stimulation.

Fig. 2.

Left panel (Conventional rTMS). From the top: examples of 10 s of rTMS at 1 Hz (first trace) and at 5 Hz (second trace); 1 s of rTMS at 10 Hz and a typical exampleof 20 Hz application for therapeutic purposes (trains of 2 s interleaved by a pause of 28 s). Right panel (Patterned rTMS). From the top: 20 s of continuous theta burst (first trace); intermittent theta burst (second trace) and intermediate theta burst (third trace). The fourth trace represents protocols of quadripulse stimulations (QPS).

Patterned rTMS refers to repetitive application of short rTMS bursts at a high inner frequency interleaved by short pauses of no stimulation. Most used to date are the different theta burst (TBS) protocols in which short bursts of 50 Hz rTMS are repeated at a rate in the theta range (5 Hz) as a continuous (cTBS), or intermittent (iTBS) train (Huang et al., 2005; Di Lazzaro et al., 2008) (Fig. 2).

Lasting inhibitory aftereffects of 1 Hz rTMS and cTBS and facilitatory after-effects following high-frequency rTMS and iTBS were found on motor corticospinal output in healthy subjects, with a neurophysiologic substrate that remains unclear. Various mechanisms are worth considering, including synaptic changes resembling experimental long term depression (LTD) and long term potentiation (LTP) mechanisms, as well as shifts in network excitability, activation of feedback loops, activity-dependent metaplasticity (Gentner et al., 2008; Iezzi et al., 2008) etc. In the context of the present manuscript, a few issues are worth pointing out as they are relevant for the safety of TMS.

Regarding rhythmic, conventional repetitive, rTMS it is noteworthy, that in order to comply with present safety guidelines, protocols of slow rTMS (≤1 Hz stimulation frequency) generally apply all pulses in a continuous train, whereas protocols of fast rTMS (e.g., ≥5 Hz stimulation frequency) apply shorter periods of rTMS separated by periods of no stimulation (e.g., 1200 pulses at 20 Hz and subthreshold stimulation intensity might be delivered as 30 trains of 40 pulses (2 s duration) separated by 28 s intertrain intervals (Fig. 2). There is only limited safety information on the effect of inserting pauses (intertrain intervals) into rTMS protocols (Chen et al., 1997). However, considering metaplasticity arguments (Abraham and Bear, 1996; Bear, 2003), it is likely that such pauses also have a significant impact on the effect of rTMS, both in terms of efficacy and safety. Therefore, further investigations are needed.

Regarding patterned rTMS, most TBS protocols employed to date replicate the original ones explored by Huang et al. (2005): for cTBS 3 pulses at 50 Hz are applied at 5 Hz for 20 s (300 total stimuli) or 40 s (600 stimuli). For iTBS twenty 2 s periods of cTBS each separated from the following by 8 s are applied (Fig. 2). Obviously, there are an infinite variety of combinations of such protocols, and it is important to emphasize that the effects and safety of the different protocols may differ, and that small changes, may have profound impact.

Recently, quadripulse stimulation (QPS) (Hamada et al., 2008) has been added to patterned rTMS procedures able to induce long-term changes of cortical excitability (see Fig. 2). Repeated trains of four monophasic pulses separated by interstimulus intervals of 1.5–1250 ms produced facilitation (at short intervals) or inhibition (at longer intervals), probably through a modulatory action on intracortical excitatory circuitry (Hamada et al., 2008).

The combination of repeated sub-motor threshold 5 Hz repetitive electrical stimulation of the right median nerve synchronized with sub-motor threshold 5 Hz rTMS of the left M1 at a constant interval for 2 min, or paired associated stimulation (PAS), is another protocol to temporally enhance rTMS effects at cortical level on the basis of a previously demonstrated interaction of the conditioning and test stimuli at the cortical level (Mariorenzi et al., 1991), perhaps through (meta)-plasticity mechanisms (Quartarone et al., 2006).

Repetitive paired-pulse stimulation (not included in Fig. 2) has be performed at ICF periodicity (Sommer et al., 2001) or i-wave periodicity (Di Lazzaro et al., 2007) [(also termed iTMS (Thickbroom et al., 2006) or rTMS (Hamada et al., 2007)]. Although higher excitability increases could be observed in comparison to single-pulse rTMS no seizures have been reported so far with this technique.

In all studies introducing new TMS protocols, safety should be addressed by including careful monitoring of motor, sensory and cognitive functions before, during, and after the intervention.

2.2. Interaction of magnetic field with tissue

In TMS, electric charge stored in a capacitor is discharged through a stimulation coil, producing a current pulse in the circuit that generates a magnetic field pulse in the vicinity of the coil. According to Faraday's law of electromagnetic induction, this time-varying magnetic field induces an electric field whose magnitude is proportional to the time rate of change of the magnetic field, which in the case of TMS is determined by the rate of change of the current in the coil. If the coil is held over a subject's head, the magnetic field penetrates scalp and skull, and induces an electric field in the brain. The induced electric field causes ions to flow in the brain, without the need for current to flow across the skull and without charged particles being injected into the scalp. In contrast, in transcranial electric stimulation (TES) charge is injected into the scalp at the electrodes and current must flow through the skull. Due to the low conductivity of the skull, in TES a large potential difference must be applied between the electrodes in order to achieve a current density in the brain high enough to stimulate neurons, and this leads to a much higher current density in the scalp. Thus, the ratio of the maximum current density in the scalp to the maximum current density in the brain is much lower in TMS than for TES, allowing TMS to stimulate cortical neurons without the pain associated with TES.

The flow of ions brought about by the electric field induced in the brain alters the electric charge stored on both sides of cell membranes, depolarizing or hyperpolarizing neurons. The existence of passive ion channels renders the membrane permeable to these ions: an increased membrane conductance decreases the amplitude of the change in membrane potential due to the induced electric field and decreases the time constant that characterizes the leakage of the induced charge. Experimental evidence (Amassian et al., 1992; Maccabee et al., 1993) and theoretical calculations (Nagarajan et al., 1993) indicate that stimulation occurs at a lower threshold where axons terminate, or bend sharply, in the relatively uniform electric field induced by the TMS stimulation coil. Accordingly, stimulation should occur where the electric field is strongest and points along the direction of an axon that terminates, for example at a synapse, or bends sharply. Axons with larger length constants, and hence larger diameters, are expected to be stimulated at lower stimulus intensity.

The stimulators and coils currently in production develop about 1.5–2.0 Tesla (T) at the face of the coil, produce currents changing at rates up to 170 A/μs (Thielscher and Kammer, 2002) and induce electric fields in the cortex of up to about 150 V/m. They are thought, depending by the stimulation intensity, to be able to activate cortical neurons at a depth of 1.5–3.0 cm beneath the scalp using standard Figure 8, circular or double-cone coils. The Figure 8 coil produces a more focal and shallower stimulation, whereas the double-cone coil was especially designed for stimulation of deeper cortical targets. When using intensities below 120% of motor threshold, the stimulation can not induce direct activation at depth of more than 2 cm beneath the scalp (Roth et al., 2002, 2007; Zangen et al., 2005; Roth et al.,).

Stimulus waveform and current direction have a significant impact on stimulation threshold. Shorter stimulus duration requires larger pulse amplitude but lower pulse energy to achieve stimulation (Barker, 1991; Hsu et al., 2003; Peterchev et al., 2008). For monophasic pulses over the motor cortex, a lower threshold is observed when the induced current flows in the brain in posterior-anterior direction. For biphasic pulses, the threshold is lowest when the induced current flows in the posterior-anterior direction in the second phase, and hence in the opposite direction from the first phase (Kammer et al., 2001). This effect can be explained in terms of the delayed (capacitive) response of the membrane (Davey and Epstein, 2000; Corthout et al., 2001). Stimulation threshold is lower for biphasic stimuli than for monophasic stimuli only if compared in terms of the energy stored in the stimulator's capacitors. In practice, the relative value of these two thresholds may be different for different stimulators (Kammer et al., 2001), which might have relevance in terms of safety.

Several simulation models have been developed to provide a view of the electromagnetic field distributions generated in biological tissue during TMS (Wagner et al., 2007). The simplified geometries of early models argued for the absence of currents normal to the superficial cortex and limited effects of surrounding tissues or altered anatomies, but more realistic head models indicate that such conclusions are inaccurate. For example, the conjecture that radial currents are absent during TMS, has influenced the interpretation of clinical studies related to the generation of indirect (I) and direct (D) waves and justified the claim that inter-neurons tangential to the cortical surface are preferentially stimulated. However, such clinical interpretations need to be reevaluated in light of recent modeling work (Nadeem et al., 2003; Miranda et al., 2003; Wagner et al., 2004; De Lucia et al., 2007) that clearly demonstrate the importance of accounting for the actual head model geometry, tissue compartmentalization, tissue conductivity, permittivity, heterogeneity and anisotropy when calculating the induced electric field and current density. From a safety point of view, it is important to note that changes in the tissue anatomy and electromagnetic properties have been shown to alter the TMS induced stimulating currents in both phantom and modeling studies. Wagner et al. (2006, 2008) compared the TMS field distributions in the healthy head models with those in the presence of a stroke, atrophy or tumor. For each of these pathologies, the TMS induced currents were significantly altered for stimulation proximal to the pathological tissue alterations. The current density distributions were modified in magnitude and direction, potentially altering the population of stimulated neural elements. The main reason for this perturbation is that altered brain tissue can modify the conductivities and effectively provide paths of altered resistance along which the stimulating currents flow. Given these findings, modeling of induced electric field and current density in each patient with brain pathologies using a realistic head model, would be desirable to maximize precision. However, it is important to emphasize, that even in the absence of individualized modeling of induced currents, studies of TMS in a variety of patient populations over the past decades have proven remarkably safe if appropriate guidelines are followed.

2.3. Types of coils

The most commonly used coil shape in TMS studies consists of two adjacent wings, and is termed the Figure 8. This shape allows relatively focal stimulation of superficial cortical regions, underneath the central segment of the Figure 8 coil. Neuronal fibers within this region with the highest probability for being stimulated are those which are oriented parallel to the central segment of the coil (Basser and Roth, 1991; Roth and Basser, 1990; Chen et al., 2003).

The relative angle between the wings affects the efficiency and focality of the coil. Coil elements which are non-tangential to the scalp induce accumulation of surface charge, which reduces coil efficiency (Tofts, 1990; Branston and Tofts, 1991; Eaton, 1992). Hence, when the angle is smaller than 180°, the wings are more tangential to the scalp, and the efficiency increases (Thielscher and Kammer, 2004). Yet, a one-plane design (180° head angle) is the most convenient form for fine localization over the head; hence it is the most commonly used.

Many studies are performed with circular coils of various sizes. Larger diameters allow direct stimulation of deeper brain regions, but are less focal. While no comparative studies have been performed to analyze the safety of circular vs. Figure 8 coils, there is no evidence for large differences in the safety parameters.

The double cone coil is formed of two large adjacent circular wings at an angle of 95°. This large coil induces a stronger and less focal electric field relative to a Figure 8 coil (Lontis et al., 2006), and allows direct stimulation of deeper brain regions. Because of its deep penetration, this coil allows for activation of the pelvic floor and lower limbs motor representation at the interhemispheric fissure. It is also used for cerebellar stimulation. It may induce some discomfort when higher intensities are required for stimulation of deep brain regions.

A more recent development allowing considerable reduction in power consumption and heat generation during operation, makes use of ferromagnetic cores (Epstein and Davey, 2002). The safety of such iron-core coils, using a relatively high intensity (120% of MT) and frequency (10 Hz, 4 s trains), was recently demonstrated in a large multi-center study evaluating its antidepressant effects (O'Reardon et al., 2007).

Overheating of coils during rTMS poses severe limitations on effective and safe operation, and requires an adequate cooling method. Weyh et al. (2005) introduced a Figure 8 coil with a reduced-resistance design to achieve significantly improved thermal characteristics. In addition to having increased electrical efficiency, iron-core coils offer advantages in this regard as well, as the ferromagnetic core serves as a heat sink. Water-, oil- and forced-air cooling methods have been implemented by various manufacturers.

Coil designs for stimulation of deeper brain areas, termed H-coils, have been tested ex vivo and in human subjects (Roth et al., 2002, 2007; Zangen et al., 2005), Other theoretical designs for deep brain TMS have been evaluated with computer simulations, such as stretched C-core coil (Davey and Riehl, 2006; Deng et al., 2008) and circular crown coil (Deng et al., 2008). Coils for deep brain stimulation have larger dimensions than conventional coils, and provide a significantly slower decay rate of the electric field with distance, at the expense of reduced focality. Due to their reduced attenuation of the electric field in depth, these coils could be suitable for relatively non-focal stimulation of deeper brain structures. However, it is important to remember that as in all TMS coils, the stimulation intensity is always maximal at the surface of the brain. The safety and cognitive effects of some H-coils at relatively high intensity (120% MT) and frequency (20 Hz) have been assessed (Levkovitz et al., 2007), and these coils have received regulatory approval for human use in Europe.

3. Safety concerns

3.1. Heating

Tissue heating of the brain by a single-pulse TMS itself is very small and is estimated to be definitely less than 0.1 °C(Ruohonen and Ilmoniemi, 2002). It appears to be even smaller in areas with low perfusion such as cysts or strokes (R. Ilmoniemi, personal communication). However, high brain blood perfusion ensures a safety range (Brix et al., 2002). For comparison, heating in the immediate surround of deep brain stimulation electrodes is estimated to be at maximum 0.8 °C (Elwassif et al., 2006).

Eddy currents induced in conductive surface electrodes and implants can cause them to heat up (Roth et al., 1992; Rotenberg et al., 2007). The temperature increase depends on the shape, size, orientation, conductivity, and surrounding tissue properties of the electrode or implant as well as the TMS coil type, position, and stimulation parameters. Silver and gold electrodes are highly conductive and can heat excessively, potentially causing skin burns. Temperature of 50 °C for 100 s or 55 °C for 10 s can produce skin burns (Roth et al., 1992). The use of low-conductivity plastic electrodes can reduce heating. Radial notching of electrodes and skull plates can also reduce heating by interrupting the eddy current path. Skull plates made of titanium tend to have low heating, due to the low conductivity of titanium and radial notching (Rotenberg et al., 2007). Brain implants such as aneurysm clips and stimulation electrodes can heat as well. Brain tissue heating above 43 °C can result in irreversible damage (Matsumi et al., 1994). If TMS is to be applied near electrodes or implants, it is advisable to first measure the heating ex vivo with the parameters specified in the planned TMS protocol. The results of such testing should be reported for the benefit of the scientific community.

3.2. Forces and magnetization

The magnetic field pulse generated by the TMS coil exerts attractive forces on ferromagnetic objects and repulsive forces on non-ferromagnetic conductors. Therefore, TMS can result in forces on some head implants that could potentially displace them. The forces on ferromagnetic objects tend to be larger than those on non-ferromagnetic conductors. Titanium skull plates are non-ferromagnetic and low-conductivity, and may have radial notches which reduce the induced force. Some titanium skull plates may be safe for TMS (Rotenberg et al., 2007).

The net energy imparted to stainless steel aneurysm clips is measured to be typically less than 10–10 J, equivalent to the clip being moved vertically by less than 0.0003 mm, which is unlikely to produce a clinical problem (Barker, 1991). Cochlear implants incorporate a magnet under the scalp that could be moved or demagnetized by the TMS pulse. Analogously to the evaluation of heating, it is advisable to first measure the forces ex vivo with the parameters specified in the planned TMS protocol. Jewelry, glasses, watches and other potentially conducting or magnetic objects worn on the head should be removed during TMS to prevent interactions with the magnetic field.

3.3. Induced voltages

The strong magnetic field pulse emitted by the TMS coil can induce large voltages in nearby wires and electronic devices. The wires connecting to scalp electrodes should be kept free of loops and should be twisted together to reduce magnetically-induced voltages. Active brain implants, such as deep brain stimulation (DBS) systems, epidural electrode arrays for cortical stimulation, and cochlear implants contain intracranial electrodes connected to subcutaneous wires in the scalp. TMS can induce voltages in the electrode wires whether the implant is turned ON or OFF, and this can result in unintended stimulation in the brain. TMS pulses can also damage the internal circuitry of electronic implants near the coil, causing them to malfunction.

More in detail, three ex vivo studies have specifically dealt with the issue of safety (Kumar et al., 1999; Kühn et al., 2004; Schrader et al., 2005). Kumar et al. (1999) investigated the safety of TMS applied to non-implanted deep brain electrodes embedded in a conducting gel with impedance similar to the impedances found when the electrodes are in the brain. They found that the induced currents in the leads are 20 times smaller than those normally produced by the stimulator when it is used in patients, and concluded that magnetic stimulation over the coiled scalp leads does not deliver damaging stimuli to the patient's brain (Kumar et al., 1999). As a part of a study of modulation of motor cortex excitability by DBS, Kühn et al. (2004) tested the voltages induced in DBS leads in a phantom skull with methods similar to Kumar et al. (1999). They reported voltages up to 0.7 V induced in the electrode wires, and concluded that these are safe levels, since they are below the voltages generated by DBS. Schrader et al. (2005) assessed the effects of single-pulse TMS on a vagal nerve stimulation (VNS) device in regard to any current induced in VNS leads during TMS. They concluded that single-pulse TMS can be safely applied to individuals who have an implanted VNS device.

A significant limitation of the ex vivo safety studies (Kumar et al., 1999; Kühn et al., 2004; Schrader et al., 2005) is that only the induced voltages between pairs of contacts on the electrode lead were tested, whereas the induced voltages between the electrode contacts and the contact formed by the implanted pulse generator (IPG) case were not measured. The circuit formed by the wires connecting pairs of electrode contacts constitutes a conductive loop with a relatively small area, thus electromagnetic induction produces low voltages. On the other hand, the circuit formed by the wires connecting to the electrode contacts and the IPG case constitutes a conductive loop with a significantly larger area, and therefore electromagnetic induction can produce relatively high voltages. Thus, the induced voltages and currents reported in existing ex vivo safety studies could be significantly underestimating the magnitudes induced in vivo.

In addition to voltages and currents induced in the stimulation leads, the electromagnetic pulse generated by TMS can cause malfunction or even damage in the internal circuitry of electronic implants near the TMS coil. TMS pulses delivered ex vivo at a distance of 2–10 cm from the TMS coil to DBS IPG caused the IPG to malfunction, and for distances of less than 2 cm, the IPG was permanently damaged (Kumar et al., 1999; Kühn et al., 2004). A similar study of the effect of TMS pulses on a VNS IPG did not detect signs of malfunction or damage to the IPG by the TMS pulse (Schrader et al., 2005).

Cochlear implants consist of a loop antenna, a permanent magnet, an electronic chip implanted under the scalp, and an electrode implanted in the cochlea. There is no safety data on TMS in subjects with cochlear implants, but basic physics considerations suggest that it is likely unsafe. The TMS pulse can induce high voltages in the loop antenna, can move or demagnetize the permanent magnet, and can cause malfunction or damage to the electronic chip. Further, cochlear implants are not MRI compatible. Therefore, TMS should not be performed in subjects with cochlear implants, unless a detailed safety evaluation proves there are no adverse effects.

3.4. TMS in patients with implanted stimulating/recording electrodes

A large number of TMS studies have been performed in patients with electrodes implanted both in central and peripheral nervous system. Most employed single-pulse TMS, some used paired pulse TMS and a few studies used repetitive TMS (see Supplemental material, Table S1). The main aims of such studies have been:

Evaluation of the effects of TMS on the central nervous system activity either by recording the responses evoked by TMS or by evaluating the changes of the ongoing spontaneous electrophysiological activity after TMS through the implanted electrodes;

Evaluation of the effects of stimulation of nervous system structures by the implanted electrodes, as revealed by TMS evoked responses.

The first in vivo study with spinal cord stimulators was performed by Kofler et al. (1991) in four patients, and they reported that TMS was safely applied with the devices turned OFF and ON, with no apparent adverse effect (Kofler et al., 1991). Since then, studies performed in patients with implanted electrodes (see Supplemental material, Table S1) have used mainly three types of electrodes: (1) epidural electrodes (implanted over the cerebral cortex or spinal cord); (2) deep brain electrodes; or (3) peripheral or cranial nerve stimulating electrodes (e.g., vagus nerve (VN) electrodes). Some of the studies were performed in the few days following implantation, whilst the electrode leads were externalized before connection to a subcutaneous stimulus generator, while other studies were performed in patients with the leads connected to implanted stimulators. Two of the latter studies (Kühn et al., 2002; Hidding et al. 2006) showed that TMS-induced lead currents can produce motor responses in vivo, suggesting that the magnitude of these currents was higher than the negligible levels measured ex vivo. This phenomenon could be explained by currents induced between the electrode contacts and the IPG case, which were not measured in the ex vivo tests (see Section 3.3). Kühn et al. (2002) performed TMS in 5 dystonic patients with implanted electrodes in globus pallidus internus. These authors suggested that TMS can induce currents in the subcutaneous wire loops in patients with implanted DBS electrodes which are sufficient to activate corticospinal fibres subcortically and to elicit pseudo-ipsilateral hand motor responses (Kühn et al., 2002). Similar findings were reported in 8 parkinsonian patients with subthalamic nucleus (STN) electrodes and leads connected to an implanted stimulator (Hidding et al., 2006). The mean onset latencies of motor responses recorded in the relaxed first dorsal interosseous muscle were significantly shorter after electrode implantation compared to the preoperative state. The authors ascribed the shortening of the corticomotor conduction time to inadvertent stimulation of fast-conducting descending neural elements in the vicinity of the STN through current induction in subcutaneous scalp leads underneath the TMS coil connecting the external stimulator with STN electrodes, thereby producing submotor threshold descending volleys. Importantly though, no adverse effects were reported by Kühn et al. (2002) and by Hidding et al. (2006).

In summary, based on ex vivo and in vivo studies, it appears that TMS can be safely applied to patients who have implanted stimulators of the central and peripheral nervous system when the TMS coil is not in close proximity to the internal pulse generator (IPG) system. However, we lack detailed information as to what constitutes a safe distance between the TMS coil and the implanted stimulator, and how coil shape, coil angulation, etc. influence this relation. Therefore, TMS should only be done in patients with implanted stimulators if there are scientifically or medically compelling reasons justifying it. TMS procedures need to strictly follow a pre-specified experimental protocol and setting, with appropriate oversight by the Institutional Review Board or Ethic Committee. In such instances, to prevent accidental firing of the TMS coil near electronic implants, the subjects could wear a lifejacket or a similar arrangement which provides about 10 cm of padding around the electronic implant (Schrader et al., 2005).

TMS is considered safe in individuals with VNS systems (Schrader et al., 2005), cardiac pacemakers, and spinal cord stimulators as long as the TMS coil is not activated near the components located in the neck or chest. If a TMS coil is discharged close to the implanted wires connecting the electrodes to the IPG, potentially significant voltages and currents could be induced between the electrode leads and the IPG, which could cause unintended neural stimulation and may present a safety risk. This scenario can occur in DBS and cortical stimulation with epidural electrodes. Additional safety studies should be conducted to evaluate the magnitude of the voltages and currents induced in implanted stimulation systems. Finally, TMS in subjects with cochlear implants should not be performed, due to multiple possibly unsafe interactions between the TMS pulse and the implant.

3.5. Magnetic field exposure for subjects/patients

Single sessions of TMS or rTMS do not carry the risk of significant magnetic field exposure since the total time is too short. However, a typical treatment course of rTMS for a psychiatric application (e.g., 10 Hz, trains of 20 pulses, 5× s, 20 sessions) yields about 5 s of total exposure (Loo et al., 2008). Theoretically, this kind of exposure would fall into radiofrequency range (i.e., from 3 kHz to 300 GHz), assuming a continuous stimulation with each pulse lasting about 250 μs (Barker, 1991).

In a current TMS depression trial, the researchers (M. George, personal communication) are delivering 6000 stimuli in a day (120% of MT, 10 Hz, 5 s on-10 off, for 30 min each day), in an open-ended dynamically adaptive design where they treat to remission as long as there is continued improvement. There is a maintenance phase and patients can be retreated if they relapse. One 28-year old patient has now received 70 sessions over 12 months, or 420.000 pulses, with no side effects. Several patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis have also received a very prolonged treatment using cTBS. One 75-year old patient has received 130 sessions over 26 months with a total number of 156,000 stimuli, while 7 patients received 60 sessions over 12 months with a total number of 72,000 stimuli (Di Lazzaro et al., 2009).

As pointed out (Loo et al., 2008), it is unclear whether the high intensity, pulsed stimulation of TMS has the same long-term effects of continuous, low-intensity, occupational exposure. It is even less clear whether effects of long-term exposure to rTMS might be changed by concurrent medications. Prospective studies in this sense would be desirable. Nonetheless, it is worth noting that chronic exposure to electro-magnetic fields appears safe at levels even greater than those possible with TMS (Gandhi, 2002; Martens, 2007).

3.6. Magnetic field exposure for operators

Safety issues are rarely addressed for operators who are exposed to magnetic field several hours every day for years by performing TMS. Guidelines for occupational levels of exposure to electromagnetic fields have been proposed by the International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection (see ICNIRP, 2003) and by a Directive from the European Parliament [directive 2004/40/EC (Riches et al., 2007a)]. This directive introduces Exposure Limit Values for workers and also Action Values (magnitude of electromagnetic field which is directly measurable). In contrast, long term effects have been excluded from the scope of the directive. This directive has been operational from 30 April 2008 in all countries of the European Union (now postponed to April 30, 2012). Occupational exposure to magnetic fields has been measured for MRI units (Riches et al., 2007a). Exposure values are 100 times below the recommended exposure limits (Bradley et al., 2007), except in case of interventional procedures (Hill et al., 2005; Riches et al., 2007b).

Regarding TMS/rTMS, only one study has been performed using the MagPro machine (Medtronic), MC-B70 Figure 8 coil, 5 Hz frequency, and stimulus intensity of 60–80% stimulator output (Karlström et al., 2006). In these conditions, worker's exposure limits for the magnetic field pulses are transgressed at a distances of about 0.7 m from the surface of the coil. This single observation makes necessary further research to confirm it and to determine the limiting distance to the coil according to the type of TMS machine, the type of coil, the frequency/intensity of stimulation and the total exposure time.

The potential risk of long-term adverse event for rTMS operators due to daily close exposure (even to weak electromagnetic fields), repeated for years, is an open issue that should be addressed in the future.

4. Side effects

All the known side effects linked with TMS use are summarized in Table 1. It is apparent that data on theta burst stimulation (TBS) are still not sufficient to claim or deny safety hazards. This implies that future therapeutic and research studies employing TBS and other forms of patterned repetitive TMS should explicitly address this issue, which has been neglected up to now. Below, the most significant, potential side effects of conventional TMS are commented on in further detail, including potentially hazardous TMS-related activity (see points 3.1–3.8):

Table 1.

Potential side effects of TMS. Consensus has been reached for this table.

| Side effect | Single-pulse TMS | Paired-pulse TMS | Low frequency rTMS | High frequency rTMS | Theta burst |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seizure induction | Rare | Not reported | Rare (usually protective effect) | Possible (1.4% crude risk estimate in epileptic patients; less than 1% in normals) | Possible (one seizure in a normal subject during cTBS) (see para 3.3.3) |

| Transient acute hypomania induction | No | No | Rare | Possible following left prefrontal stimulation | Not reported |

| Syncope | Possible as epiphenomenon (i.e., not related to direct brain effect) | Possible | |||

| Transient headache, local pain, neck pain, toothache, paresthesia | Possible | Likely possible, but not reported/addressed | Frequent (see para. 3.3) | Frequent (see para. 3.3) | Possible |

| Transient hearing changes | Possible | Likely possible, but not reported | Possible | Possible | Not reported |

| Transient cognitive/neuropsychologial changes | Not reported | No reported | Overall negligible (see Section 4.6) | Overall negligible (see Section 4.6) | Transient impairment of working memory |

| Burns from scalp electrodes | No | No | Not reported | Occasionally reported | Not reported, but likely possible |

| Induced currents in electrical circuits | Theoretically possible, but described malfunction only if TMS is delivered in close proximity with the electric device (pace-makers, brain stimulators, pumps, intracardiac lines, cochlear implants) | ||||

| Structural brain changes | Not reported | Nor reported | Inconsistent | Inconsistent | Not reported |

| Histotoxicity | No | No | Inconsistent | Inconsistent | Not reported |

| Other biological transient effects | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Transient hormone (TSH), and blood lactate levels changes | Not reported |

4.1. Hearing

Rapid mechanical deformation of the TMS stimulating coil when it is energized produces an intense, broadband acoustic artifact that may exceed 140 dB of sound pressure level (Counter and Borg, 1992). This exceeds the recommended safety levels for the auditory system (OSHA). Before using a given coil/stimulator, the operator may consult the manufacturer's Instructions for use or technical specifications to check the specified sound pressure levels.

After exposure to the TMS stimulus, a small proportion of adult humans have experienced transient increases in auditory thresholds (Pascual-Leone et al., 1992; Loo et al., 2001). Permanent threshold shift has been observed in a single individual who did not have ear plugs and was being stimulated with an H-coil (Zangen et al., 2005). The majority of studies in which hearing protection was used report no change in hearing after TMS (Pascual-Leone et al., 1991; Levkovitz et al., 2007; Folmer et al., 2006; Rossi et al., 2007a; Janicak et al., 2008). The single publication regarding hearing safety in pediatric cases reports no change in hearing in a group of 18 children without hearing protection (Collado-Corona et al., 2001). This is encouraging; however, the sample size is too small to ensure hearing safety for pediatric cases. Young children are of particular concern because their canal resonance is different from adults, their smaller head size results in the TMS coil being closer to the ear, and appropriate hearing protection devices for children are not available.

Therefore, it is recommended that:

Hearing safety concerns for adults be addressed by: (i) use of approved hearing protection (earplugs or ear muffs) by individuals trained in placement of these devices; (ii) prompt referral for auditory assessment of all individuals who complain of hearing loss, tinnitus, or aural fullness following completion of TMS; (iii) those with known pre-existing noise induced hearing loss or concurrent treatment with ototoxic medications (Aminoglycosides, Cisplatine) should receive TMS only in cases of a favorable risk/benefit ratio, as when rTMS is used for treatment of tinnitus.

Individuals with cochlear implants should not receive TMS (see also paragraphs 2.2 and 2.3).

The acoustic output of newly developed coils should be evaluated and hearing safety studies should be conducted as indicated by these measures.

Hearing safety concerns for children have not been sufficiently addressed in published literature (see also paragraph 4.5) to justify participation by pediatric healthy volunteers in TMS studies until more safety data are available. Application of rTMS in pediatric patient populations with therapeutic intent may be reasonable if the potential benefits outweigh the theoretical risks of hearing problems.

4.2. EEG aftereffects

Recording of electroencephalographic (EEG) activity immediately before, during, and after TMS is possible provided that certain technical challenges are addressed and few precautions taken (Ilmoniemi et al., 1997; Bonato et al., 2006; Thut et al., 2005; Ives et al., 2006; Morbidi et al., 2007). Problems related to the saturation of the EEG recording amplifiers from the TMS pulse have been overcome via artifact subtraction, pin-and-hold circuits, the use of modified electrodes which do not transiently change their shape due to the stimulus impact, and altering the slew rate of the preamplifiers.

There is a considerable number of publications of combined TMS-EEG to date (85 studies on more than 1000 volunteers over the last 19 years). The studies that quantified aftereffects on EEG activity induced by conventional or patterned rTMS are listed in Table S2 (supplemantal material) and discussed in this section. The studies on EEG-aftereffects in the form of potential TMS-induced epileptiform EEG-abnormalities are listed in Table 2 and discussed in Section 4.3.5. Single-pulse studies are not included in either table since safety concerns did not arise. However, in Table 2, special emphasis is placed on patient populations who might be more vulnerable to TMS due to several factors (i.e., brain damage, drug treatment or discontinuation of treatment for the purpose of a study).

Table 2.

Inspection of EEG for epileptiform abnormalities during or after repetitive TMS in patients and healthy subjects. Consensus has been reached for this table.

| Authors | Subjects | TMS-parameters | EEG-measures | Timing of EEG | Findings with potential safety concern | Duration of after-effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loo et al., 2001 | N = 18 Depression | 10 days of 10 Hz/30 × 5 s train: 25 s ITI DLPFC/110%MT | visual inspection waking EEG | before and after TMS | Yes: Minor, potentially epileptiform abnormalities in 1 patient (in the absence of seizure) | not assessed |

| Boutros et al., 2001 | N = 5 Depression | max 10 days of 5–20 Hz/max 20 × 2 s: 58 s ITI DLPFC/80–100%MT | visual inspection waking EEG | before and during TMS | No: despite EEG-abnormalities at baseline: no change | |

| Boutros et al. (2000) | N = 14 Depression | 10 days of 20 Hz/20 × 2 s train: 58 s ITI DLPFC/80%MT | visual inspection waking EEG | before, during and after TMS | Yes: 1 case with rare slow-wave transients online to TMS | no after-effects |

| N = 7 Schizophrenia | 4 sessions of 1 Hz/4:6:12:16 min temporal cortex | visual inspection waking EEG | before, during and after tTMS | No (no change) | no after-effects | |

| N = 5 OCD | 5 days of 20 Hz/30 × 2 s train: 58 s ITI DLPFC/80%MT | visual inspection waking EEG | before, during and after TMS | Yes: 1 case with increased theta activity during TMS | no after-effects | |

| Fregni et al., 2006 | N = 15 Stroke | 5 days of 1 Hz/20 min Unaffected hemisphere/100%MT | visual inspection waking EEG | online and 2 h after treatment | No (no change) | no after-effects |

| Cantello et al., 2007 | N = 43 Epilepsy | 5 days of 0.3 Hz/55.5 min vertex/100%rMT | visual inspection waking EEG Semi-quantitative | before and after TMS | No: decrease in interictal spikes in 1/3 of patients | |

| Joo et al., 2007 | N = 35 Epilepsy | 5 days of 0.5 Hz/50-100 min focus or vertex/100%rMT | visual inspection waking EEG | before and after treatment | No: decrease in interictal spikes | not assessed |

| Conte et al., 2007 | N = 1 Epilepsy | different sessions of 5 Hz/2 s trains vertex/120%MT | duration of spike and waves | online to TMS | No: decrease in duration of discharges | no after-effect |

| Fregni et al., 2006 | N = 21 Epilepsy | 5 days of 1 Hz/20 min foucs/70% max | visual inspection waking EEG | before and after TMS | No: decrease in epileptiform discharges | up to 30 days washed out at 60 days |

| Fregni et al., 2005 | N = 8 Epilepsy | 1 session of 0.5 Hz/20 min Focus/65% max | visual inspection waking EEG | before and after treatment | No: decrease in epileptiform discharges | at least 30 days |

| Misawa et al., 2005 | N = 1 Epilepsy | 1 session of 0.5 Hz/3.3 min focus/90%MT | visual inspection waking EEG | during TMS | No: significant change in EEG with epilepsy abolishment | 2 month |

| Rossi et al., 2004 | N = 1 Epilepsy | 1 session of 1 Hz/10 min focus/90%rMT | Spike averaging | before and after TMS | No: reduction in spike amplitude | not assessed |

| Menkes and Gruenthal, 2000 | N = 1 Epilepsy | 4 × 2 days of 0.5 Hz/3.3 min focus/95%MT | visual inspection waking EEG | before and after TMS | No: reduction in interictal spikes | not assessed |

| Schulze-Bonhage et al., 1999 | N = 21 Epilepsy | 4 stimuli at 20/50//100/500 Hz M1/120–150%MT | visual inspection waking EEG | during TMS | No: no case of after-discharges clearly assignable to TMS/interictal activity unchanged | no after-effects |

| Jennum et al., 1994 | N = 10 Epilepsy | 1 session of 30 Hz/8 × 1 s trains: 60 s ITI temporal and frontal/120%MT 50 Hz/2 × 1 s train: 60 s ITI frontal/120%MT | visual inspection waking EEG | before, during and after tTMS |

No: less epileptiform activity during TMS No: less epileptiform activity during TMS |

recovery after 10 min Recovery after 10 min |

| Steinhoff et al., 1993 | N = 19 Epilepsy | 0.3–0.1 Hz | visual inspection waking EEG | No: reduction of epileptic activity in some cases | ||

| Hufnagel and Elger (1991) | N = 48 Epilepsy | single or low frequency (<0.3 Hz) | visual inspection subdural electrodes | Yes/no: enhancement and suppression of epileptiform activity | na | |

| Dhuna et al., 1991 | N = 8 Epilepsy | 1 session of 8–25 Hz Various sites/intensities | visual inspection waking EEG |

No: 7 patients: no EEG changes Yes: 1 patient: seizure induction with 100% output intensity |

no after-effects | |

| Kanno et al., 2001 | N = 1 Patient | 1 session 0.25 Hz/2 × 3.3 min train DLPFC/110%MT | visual inspection waking EEG | during TMS | Yes: Potential epileptiform activity (focal slow-wave, no seizure) | no after-effects |

| Huber et al., 2007 | N = 10 healthy | 5 session of 5 Hz/6 × 10 s train: 5 s ITI M1/90%rMT | visual inspection waking EEG | during TMS | No (no abnormalities) | no after-effects |

| Jahanshahi et al., 1997 | N = 6 healthy | 2 sessions of 20 Hz/50 × 0.2 s: 3 s ITI M1/105–110%aMT | visual inspection waking EEG | before and after TMS | No (no abnormalities) | no after-effects |

| Wassermannn et al., 1996 | N = 10 healthy | 1 session of 1 Hz/max 5 min 6 scalp positions/125%rMT | visual inspection waking EEG | before and after TMS | No (no abnormalities) | no after-effects |

| N = 10 healthy | 1 session of 20 Hz/10 × 2 s train: 58 s ITI | visual inspection waking EEG | before and after TMS | No (no abnormalities) | no after-effects |

Thirty-seven studies have quantified the aftereffects on functional EEG-activity due to TMS pulse repetition (Supplemental material, Table S2). Published from 1998 to 2008, most of these studies used conventional rTMS protocols (pulse repetition frequencies of 0.9–25 Hz) which followed the 1998-safety guidelines. A few studies explored EEG aftereffects after TBS (Katayama and Rothwell, 2007, Ishikawa et al., 2007), or PAS (Tsuji and Rothwell, 2002; Wolters et al., 2005). Aftereffects have been observed on a variety of EEG/EP-measures including oscillatory activity over motor and prefrontal areas (e.g., Strens et al., 2002 and Schutter et al., 2003) as well as somatosensory (e.g., Katayama and Rothwell, 2007; Ishikawa et al., 2007; Restuccia et al., 2007), visual (Schutter et al., 2003), cognitive (Evers et al., 2001a, b; Hansenne et al., 2004; Jing et al., 2001) and movement-related cortical potentials (Rossi et al., 2000; Lu et al., 2009), in accordance with the site of TMS. With three exceptions (Evers et al., 2001a, 2001b; Satow et al., 2003; Hansenne et al., 2004), all published studies reported significant aftereffects. For the studies using conventional rTMS protocols (low frequency: 0.9 and 1 Hz, high frequency: 5–25 Hz), the direction of the aftereffect (when present) was as expected, with facilitation prevailing over suppression after high frequency TMS (n = 12 vs. n = 6), and suppression prevailing over facilitation after low frequency TMS (n = 13 vs. n = 2). Note that alpha-band increase/decrease is taken as sign for inhibition/facilitation. TBS and PAS tended to induce facilitation rather than inhibition (small n of 4, see Supplemental material, Table S2).

There is evidence for such aftereffects to persist in the absence of behavioral effects (e.g., Rossi et al., 2000; Hansenne et al., 2004; Holler et al., 2006). This parallels previous findings on lasting changes in neurophysiological measures after rTMS over motor areas (MEP-amplitude) without parallel changes in amplitude or velocity of voluntary finger movements (e.g., Muellbacher et al., 2000).

Absolute duration of EEG aftereffects has been assessed in a total of 11 studies recording EEG/EPs until recovery. Duration ranged from 20 min (Tsuji and Rothwell, 2002; Thut et al., 2003a, 2003b) to 70 min (Enomoto et al., 2001) post-TMS (mean: 38.6 min; see Supplemental material, Table S2). There was no consistency in one type of protocol inducing longer-lasting effects than another (1 Hz = 38 min: mean of n = 5; 5 Hz = 28 min: mean of n = 2; TBS = 60 min: n = 1; PAS = 40: mean of n = 2), but this is preliminary given the small number of studies and the cross-study confounds of variations in number of pulses and intensity. The 20–70 min duration is in line with the duration of aftereffects on motor cortex excitability as measured through a variety of single and paired-pulse TMS protocols (e.g., Gerschlager et al., 2001; Münchau et al., 2002; Peinemann et al., 2004). This strongly suggests that aftereffect-duration can be extrapolated from motor to non-motor sites, and vice versa.

None of the reviewed TMS-EEG studies has investigated the time-course of the electrophysiological changes relative to behavioral effects. Based on what is known from behavioral TMS studies, aftereffects of a 1 Hz protocol would be estimated to last approximately as long as the duration of stimulation (Robertson et al., 2003). This would have resulted in an estimated 13.6 min vs. a measured 38 min of aftereffects in the 1 Hz TMS-EEG studies in which the EEG/EP-aftereffects were assessed (n = 5, Supplemental material, Table S2). Although speculative at this point, it is probably safe to conclude that the time of potential aftereffects would be slightly, but not dramatically, underestimated if equated to the duration of observable behavioral effects (using safe parameters).

Less is known for TBS stimulation. Yet, with the previously employed parameters (as compared to standard protocols: similar number of pulses but considerable shorter duration and lower intensity of stimulation), the duration of the effects on EEG activity (measured so far using SEP-amplitude after sensorimotor stimulation) (Katayama and Rothwell, 2007; Ishikawa et al., 2007) seems to be comparable to those after standard repetitive TMS protocols. Recently, 24 healthy volunteers participated in 2 randomized, placebo-controlled, cross-over experiments and underwent continuous TBS (cTBS), intermittent TBS (iTBS), and shamTBS either over the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (n = 12, Figure 8 coil) or the medial prefrontal cortices (n = 12, double-cone coil) (Grossheinrich et al., 2009): the only EEG aftereffects were current density changes in the alpha2 band after iTBS of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, which remained detectable up to 50 min after stimulation. However, more is needed in terms of localized (i.e., coherence, synchronization likelihood) or generalized EEG modifications induced by TBS and other patterned rTMS protocols.

In summary, it seems clear that TMS has a robust neurophysioloical effect on EEG/EPs, and that aftereffects can be demonstrated even in the absence of any behavioral effects. The duration of such aftereffects is estimated to be approximately 1 h following a single session of TMS using current protocols. This should be taken into consideration when planning experiments and when to dismiss the participants. In comparison to the previous guidelines, there is no new EEG result calling for more caution with conventional repetitive protocols (0.3–20 Hz), neither in healthy participants nor psychiatric or epilepsy patients. Further EEG studies are needed to collect more data on TBS and repeated PAS, as well as in non-psychiatric or non-epilepsy patients, given the incomplete picture we have for these protocols and patient groups (e.g., stroke). Until then, we urge caution regarding potentially long-lasting aftereffects. It should be noted as well, that this conclusion refers only to a single rTMS intervention. Repeated interventions, for example as employed in therapeutic trials of rTMS, may give rise to effects of different duration, but this is largely unknown, and in need of study.

4.3. Seizures

Induction of seizures is the most severe acute adverse effect for rTMS. Several cases of accidental seizures induced by rTMS have been reported to date, most in the early days prior to the definition of safety limits. Considering the large number of subjects and patients who have undergone rTMS studies since 1998 (see Fig. 1) and the small number of seizures, we can assert that the risk of rTMS to induce seizures is certainly very low.

Seizures are caused by hypersynchronized discharges of groups of neurons in the gray matter, mainly due to an imbalance between inhibitory and excitatory synaptic activity in favor of the latter. Seizures can be induced by rTMS when pulses are applied with relatively high-frequencies and short interval periods between trains of stimulation. rTMS might theoretically induce seizures during two different periods associated with stimulation: (1) during or immediately after trains of rTMS and, (2) during the aftereffects due to the modulation of cortical excitability (i.e., kindling effect, see Wassermannn, 1998). Although the first has been seen, there is no evidence that the latter has ever occurred. Indeed, there is no solid evidence for kindling in humans in any situation.

Here we review the cases of accidental seizures during TMS. This is critical to identify predictors associated with induction of seizures, and in turn to analyze the impact of the previous safety guidelines (Wassermannn, 1998) for prevention of seizures. We do not take into account seizures induced during “magnetic seizure therapy”, an alternative way to use rTMS to treat pharmaco-resistant depression (Lisanby, 2002) in which special stimulation devices are employed with the aim of inducing a seizure under controlled conditions and with the patient protected by muscle relaxants and anesthestics.

We conducted a systematic review up to December 2008 in which we used as keywords “seizure”, “seizures”, “transcranial magnetic stimulation”, and “TMS”. In addition we searched review papers on TMS safety and collected experience from experts in the field. We initially identified 143 articles, which were reviewed, and if a seizure was reported, we collected information on the parameters of stimulation and baseline clinical and demographic characteristics. A total of 16 cases were identified. Seven of these cases were included in the previous 1998 safety guidelines and 9 of them were reported in the following years. We created a framework in which cases were classified based on whether seizures were induced by stimulation outside or within the recommended parameters according to the previous safety guidelines (intensity, frequency and train duration). We then discussed potential factors that may have contributed to the seizures. It should be kept in mind that the 1998 safety guidelines (Wassermannn, 1998) define a combination of rTMS parameters such as frequency, intensity and duration of trains based on a study in healthy controls that used the outcomes of after-discharges and spread of excitation (Pascual-Leone et al., 1993).

Flitman et al. reported an episode of a generalized tonic clonic seizure in a healthy subject using parameters of 120% of MT, 15 Hz, train duration of 0.75 s, and with variable intervals between trials. This was a study to determine whether linguistic processing can be selectively disrupted with rTMS (Flitman et al., 1998). The very short interval (0.25 s) between trains was thought to have contributed to this episode, triggering a detailed study on the impact of duration of inter-train intervals on the risk of seizure induction. The findings resulted in the revision of prior guidelines to include interval between trains as another relevant parameter (Chen et al., 1997).

4.3.1. Seizures that have occurred with rTMS parameters considered safe according to the 1998 safety guidelines

Four of the new seizures (two following single-pulse and two following rTMS) induced by TMS since publication of the prior guidelines appear to have been induced by “safe” stimulation parameters.

Figiel et al. reported a case of a patient with major depression who developed left focal motor seizures that followed at least 6 h after the end of stimulation (100% of MT, 10 Hz, and train duration of 5 s). The use of antidepressant medications might have increased the risk of seizures. In any case, because neurological exam and EEG were normal and this episode was not responsive to anti-epileptic drugs, pseudoseizure was also considered (Figiel et al., 1998). Given the delay between the stimulation and the event, the relationship is also uncertain. This case emphasizes the critical need of careful documentation, monitoring, and evaluation by a trained clinician.

Nowak et al. (2006) reported a case of a generalized tonic clonic seizure in a patient with tinnitus receiving rTMS with parameters of 90% of MT, 1 Hz and 580 pulses (Nowak et al., 2006). There were no identifiable factors that may have contributed to this episode of seizure. However, because of clinical features, it has been questioned whether this episode actually was a convulsive syncope rather than a seizure (Epstein, 2006).

Additional to seizures occurring during rTMS, two cases of a generalized tonic clonic seizure following single-pulse TMS have been reported. One, in a patient with multiple sclerosis (66% of TMS output) in a study investigating cortical excitability has been reported. In this case, the brain lesions associated with multiple sclerosis and the use of olanzapine might have increased the risk of seizures (Haupts et al., 2004).

Tharayil et al. (2005) reported a generalized tonic clonic seizure in a patient with bipolar depression using single-pulse TMS during motor threshold (MT) assessment. The use of chlorpromazine and lithium, and also family hisory of epilepsy might have increased the risk of seizures (Tharayil et al., 2005).

In summary, three of these four instances of seizures occurred in patients taking pro-epileptogenic medications, and two of the four cases may represent non-epileptic events.

4.3.2. Seizures that have occurred with rTMS parameters outside 1998 safety guidelines

Since 1998 there have been four cases of accidental seizures in studies using parameters outside the previous safety guidelines.

Conca et al. (2000) reported a seizure in a patient with major depression in whom rTMS (110% of MT, 20 Hz, train duration 5 s) was being used as an add-on treatment (Conca et al., 2000). The extremely brief loss of consciousness in this patient (8 s) suggests syncope rather than a seizure (see Epstein, 2006).

Bernabeu et al. (2004) reported a seizure in a healthy volunteer (who was using fluoxetine 20 mg) in a study to investigate the effects of traumatic brain injury on cortical excitability as measured by a variety of TMS protocols (Bernabeu et al., 2004). The parameters in this case were 110% of MT using 20 Hz and train duration of 2 s. In addition to these rTMS parameters, fluoxetine itself is known to be potentially pro-convulsant.

Rosa et al. (2004) reported a generalized tonic clonic seizure in a patient with chronic pain using parameters of 100% of MT, 10 Hz and train duration of 10 s.

Prikryl and Kucerova (2005) reported a case of generalized tonic clonic seizure during rTMS treatment for major depression. The parameters of stimulation were 110% of MT using 15 Hz and train duration of 10s. There was also a history of sleep deprivation in this patient.

In summary, three of these four instances of seizures occurred in patients taking pro-epileptogenic medications or following sleep-deprivation, and one of the four cases may represent a non-epileptic event.

4.3.3. Seizures induced by patterned rTMS

Since the introduction of theta burst stimulation (TBS) by Huang et al. (2004, 2005) a review of the literature reveals 49 publications using TBS in normal participants or patients with tinnitus, stroke, movement disorders, or chronic pain. Overall, a total of 741 participants have undergone either continuous or intermittent TBS. A single seizure has occurred (Obermann and Pascual-Leone, 2009) in a 33-year old man healthy control without any risk factors for epilepsy and not taking any medications. Two days prior to the event the subject had an overseas flight from London to Boston, and his sleep pattern may have still been altered, though he reported restful nights and no signs of jetlag. TBS was being applied to the left motor cortex with a MagPro X100 stimulator delivering biphasic pulses via a Figure 8 coil (Model MCF-B65) with each wing measuring 8.5 cm. Stimulation intensity was set at 100% of resting motor threshold. Continuous TBS was applied as 3 pulses at 50 Hz with 200 ms intertrain interval for 50 trains (total of 150 pulses). The event, a partial, secondarily generalized tonic-clonic seizure occurred approximately 5–10 s after the completion of the final train of stimulation and lasted for 40 s with a post-ictal confusion lasting for approximately 25 min. Physical exam, detailed neurologic exam and mental status exam were normal starting 45 min after the event and remained normal later. Vital signs were stable, and all tests done were unremarkable. CTBS is traditionally thought to suppress cortical activity. However, it is possible that in some individuals cTBS may lead to facilitatory effects. Such paradoxical modulations have been reported for some subjects undergoing slow rTMS as well. Furthermore, since in this case resting motor threshold (rather than active motor threshold) was used to define the cTBS intensity, the subject was at rest prior to the stimulation, and it is possible that in such circumstances cTBS may have increased the subject's cortical excitability rather than decreasing it (Gentner et al., 2008). It should also be noted that most of the published reports of TBS use an intensity of 80% of Active Motor Threshold while the seizure occurred in a study applying an intensity of 100% of Resting Motor Threshold (which is approximately equal to 120% of Active Motor Threshold). This event also highlights the need for an intensity-dosing study with TBS protocols to assess the seizure risk.

4.3.4. Risk of seizures in epileptic patients and other patient populations

There were no TMS-linked seizures among 152 patients with epilepsy who underwent weekly rTMS applications at ≤1 Hz in the context of the largest trials designed to investigate the potential of inhibitory low-frequency rTMS to reduce seizure frequency (Theodore et al., 2002; Tergau et al., 2003; Fregni et al., 2006a, 2006b; Cantello et al., 2007; Joo et al., 2007; Santiago-Rodríguez et al., 2008).

Furthermore, the use of high frequency/high intensity rTMS was unsuccessful as a non-invasive procedure to activate epileptogenic foci (see Tassinari et al., 2003, for a review) with the exception of a minority of patients with progressive myoclonic epilepsy, who are particularly susceptible to external stimuli.

Two patients with epilepsia partialis continua received high-frequency rTMS with parameters exceeding previous guidelines, without adverse effects: in the former, 100 Hz rTMS (15 trains at 90% of maximal output at successively increasing durations ranging from 0.05 to 1.25 s.); in the latter, trains at 100% of maximal output, 20 Hz for 4 s were applied (Rotenberg et al., 2009).

A recent review on the safety of rTMS in epilepsy (Bae et al., 2007) indicated a 1.4% crude per-subject risk to develop a seizure (4 out of 280 patients) and no cases of status epilepticus. Such a low risk in epileptic patients may be due to use antiepileptic drugs, which might have a protective effect against TMS-induced seizure. In some epilepsy patients, a seizure has occurred during rTMS, but this could not unequivocally be assigned to TMS in many cases or occurred at high TMS intensity beyond safety guidelines (Dhuna et al., 1991). Of course, other factors that may increase the likelihood of inducing seizures such as history of seizures, medications that decrease seizure threshold (see later on), or other diseases potentially affecting cortical excitability (e.g., stroke or autism), need to be considered when assessing safety of rTMS treatment. In chronic stroke patients rTMS application for treatment of associated depressive symptoms was safe (Jorge et al., 2004), but rTMS trains which are usually safe for healthy volunteers (at rates of 20–25 Hz, 110–130% of MT are able to induce peripheral manifestations indexing spread of activation at cortical level, thereby potentially increasing the risk of seizures (Lomarev et al., 2007). Therefore, for patients with additional risk, rigorous monitoring is still critical. In such instances, the recommendations made in 1998 for electroencephalographic monitoring and electromyographic monitoring for spread of excitation should be entirely endorsed, along with video recording (if available) of the TMS session to be able to analyze in detail the characteristics of a spell. The involvement of a physician with expertise in the recognition and acute treatment of seizures is still strongly recommended for such instances.

4.3.5. Sub-clinical EEG abnormalities due to TMS

Table 2 summarizes those studies in which EEG recordings have been scrutinized for epileptiform activity (mainly spikes and slow-waves) before, during or after repetitive TMS. TMS-induced sub-clinical EEG abnormalities have been detected on rare occasions in patients but not in healthy volunteers. Of 49 patients suffering from psychiatric disorders and undergoing TMS treatment (many of them for up to 10 days), three cases showed minor transient epileptiform activity during or after TMS. All these patients were stimulated with high-frequency TMS (10 or 20 Hz), and stimulation was continued despite the epileptiform EEG activity and no seizure was induced (Boutros et al., 2000).

In 31 epilepsy patients in whom high frequency TMS was employed (5–100 Hz), no changes in frequency of spikes (Schulze-Bonhage et al., 1999) or even a reduction in frequency or duration was reported (Jennum et al., 1994; Conte et al., 2007). Low frequency TMS (n = 177 epilepsy patients, 0.3–1 Hz) has been shown to significantly reduce interictal spike frequency or amplitude (Hufnagel and Elger, 1991; Steinhoff et al., 1993; Misawa et al., 2005; Menkes and Gruenthal, 2000; Rossi et al., 2004a,b; Fregni et al., 2005a,b, 2006a,b; Cantello et al., 2007; Joo et al., 2007) and enhancement has been noted only rarely (Hufnagel and Elger, 1991). Even in patients who are withdrawn from antiepileptic medication, changes in interictal spike pattern and seizure induction during TMS seem to be infrequent and in rare cases only not to be coincidental (Schulze-Bonhage et al., 1999; see also Schrader et al., 2004 for review of single-pulse TMS and epilepsy). While there are many studies in psychiatry and epilepsy research, less is known in regards to TMS-induced EEG abnormalities in other patient groups (e.g., stroke: Fregni et al., 2006a,b).

In healthy participants, rTMS studies have yielded negative results as to TMS-induced EEG abnormalities (45 volunteers in 5 publications). Moreover, in one healthy participant in whom a seizure was induced while EEG was recorded, no abnormal pre-seizure EEG activity was observed (Pascual-Leone et al., 1993).

There is one observation of potentially epileptiform activity online to TMS over central leads in a patient that raises concern (Kanno et al., 2001). This is because the transient epileptiform activity occurred during rTMS at very low frequency (0.25 Hz) and early into the train (4th stimulus) so that it could not be assigned to cumulative pulse effects and seemed to be driven by only a few single pulses. In addition, this activity was likely to be TMS-induced, because it was reproduced during a second TMS session on another day (Kanno et al., 2001). Because this patient suffered from uncontrolled movements of trunk and limb, it is plausible that this patient's motor cortex might have been extremely hyperexcitable as compared to other populations (Kanno et al., 2001). Aside from this observation, however, there is no report of epileptiform activity in the many publications (n > 25) that recorded EEG online to single-pulse TMS with a methodological or fundamental neuroscientific perspective (Bridgers and Delaney, 1989; Kujirai et al., 1993; Nikouline et al., 1999; Tiitinen et al., 1999; Paus et al., 2001; Schürmann et al., 2001; Kähkönen et al., 2001, 2004, 2005; Komssi et al., 2002, 2004; Kübler et al., 2002; Thut et al., 2003a,b; Thut et al., 2005; Massimini et al., 2005, 2007; Price, 2004; Fuggetta et al., 2005, 2006; Bonato et al., 2006; Van Der Werf et al., 2006; Van Der Werf and Paus, 2006; Morbidi et al., 2007; Litvak et al., 2007; Julkunen et al., 2008; Romei et al., 2008a,b).

Therefore, it seems that subclinical epileptiform EEG activity during conventional rTMS is overall very rare, and that EEG monitoring before and during rTMS cannot effectively prevent accidental seizures induction.

4.4. Syncope

Vasodepressor (neurocardiogenic) syncope is a common reaction to anxiety and psycho-physical discomfort. It is a common experience that may occur more often than epileptic seizures during TMS testing and treatment, including TBS (Grossheinrich et al., 2009), as along with many other medical procedures (Lin et al., 1982).

Diagnostic problems arise in subjects who manifest positive phenomena during a syncopal episode. These may include behaviors considered typical of seizures: tonic stiffening, jerking, vocalizations, oral and motor automatisms, brief head or eye version, incontinence, hallucinations, and injuries from falling. Such episodes can be difficult to distinguish from epileptic events, although tongue biting and loss of urine are often lacking. Clinically, the cardinal feature that distinguishes syncope from seizure is rapid recovery of consciousness within seconds and not minutes (Lin et al., 1982). The premonitory complaint that “I need to lie down”, or “I need air”, narrowing and blacking out of the visual field, sensations of heat, bradycardia, and loss of peripheral pulses also favor circulatory collapse. Visceral distress, nausea, dizziness, pallor, and diaphoresis are frequent symptoms (Adams and Victor, 1977). Gastrointestinal symptoms occur in partial epilepsies as well, but their incidence in seizures provoked by TMS is unclear. Upward eye deviation is common in circulatory syncope, but rare in partial seizures unless they progress to generalized convulsions.