Abstract

Adaptability and emergent properties are the dominant characteristics of complex systems, whether naturally occurring or engineered. Structurally, a complex system might be made up of a large number of simpler components, or it might be formed from hierarchies of smaller numbers of interacting subsystems and work together to produce a defined function. The nucleus of a cell has all of these features, many of which may become disrupted in cancer and other disease states. The general view is that cancer progresses gradually over time; cells become premalignant, then increasingly abnormal before they become cancerous. However, recent work by Stephens et al. (2011) has revealed that cancer can emerge much more rapidly. Based on DNA sequences from multiple cancer samples of various types, they show that cancer can arise suddenly from a single catastrophic event that causes massive genomic rearrangement.

Keywords: cancer, chromosome shattering, replication timing, differentiation

Chromosome Shattering and Repair

Stephens et al. (2011) describe a novel mechanism for the development of genomic instability and tumorigenesis. The phenomenon is characterized by shattering of specific chromosomes in tumor genomes. Several key features define this shattering event. Shattered regions are non-random, suggesting some intrinsic feature that confers a certain vulnerability to this event, and conjoined segments in the reassembled chromosome are composed of regions that are normally distant spatially. Copy number variation occurs, but in most cases only one or two copies of a region are found within the repaired chromosome. The authors claim that the rearrangements are acquired early in tumor formation. For example, analysis of samples collected from one patient at initial diagnosis and then again after a relapse revealed no difference in rearrangements on the affected chromosome. However, in this particular case, it is not clear how far the cancer had progressed at time of detection. Finally, “shattering” is found in 2–3% of all cancers, based on analysis of 746 cancer cell lines, but about 25% of bone cancers, estimated from a sample of 20 patients.1–3

Chromosome shattering in this context is a novel observation, and reveals a previously unknown source of pathological disruption of DNA in cancer cells. Rather than a gradual transition from initial to advanced stages, chromosome shattering could cause sudden switching in a single, catastrophic event.4 The authors suggest ionizing radiation as a possible physical insult that could pulverize a chromosome in a localized fashion. They also implicate telomere attrition, since it is known that telomere loss can cause end to end chromosome fusion, resulting in the presence of two centromeres. If kinetochores from opposite spindles attach to the two centromeres during anaphase, a bridge would be formed that must be broken for the cell to complete division.5 The authors suggest that localized catastrophic shattering could occur at subtelomeric or other genomic regions near the bridge through the physical strain associated with breaking of the bridge. Another conjecture is that premature chromosome condensation might result in chromosome shattering, as cell fusion experiments indicate that nuclei in S phase that receive condensation signals from adjacent nuclei in mitosis can cause partially replicated chromosomes to shatter.6

Other Possible Mechanisms

A delay in both chromosome replication timing and mitotic chromosome condensation may also account for a catastrophic shattering event. Replication is a dynamically coordinated process and relates to the genome's spatial configuration in early interphase.7 Early replication occurs at more transcriptionally active sites, mostly in the central part of the nucleus, whereas late replication tends to occur at inactive sites mainly in the periphery. Since chromosomes are composed of unique configurations of both active and inactive domains, any disruption of spatial configuration may change replication timing. This might change stability of chromosome condensation and therefore lead to catastrophic transitions in genomic organization. In a series of elegant experiments involving engineering chromosomes with delayed replication, Thayer and colleagues8–10 demonstrated the presence of cis-acting loci that regulate replication timing, and showed that disruption of these loci resulted in genomic instability and complex rearrangements. While the mechanism underlying chromosome shattering remains unknown, an attractive possibility is an insult during replication itself, resulting from a combination of altered replication timing due to accumulated mutations or previous rearrangements and stalling or breakage at replication forks.11,12 Subsequent repair processes would generate the aberrantly stitched chromosome, possibly incorporating an additional copy of one or more regions during repair if the chromosome is incompletely replicated.

Dynamics of Order

Many dynamical systems have at least one meta-stable state from which two inevitable paths emerge upon disturbance of its equilibrium state, a phenomenon known as bifurcation. This system attribute may be used to describe the progression of an abnormal cell from a mildly perturbed state to one with the hallmarks of cancer.

We can think of normal embryonic stem (ES) cell differentiation as transitioning through this meta-stable state and, then given appropriate cues, cells withdraw from the cell cycle and reach a more specialized state. The meta-stable state is less ordered (higher entropy) than the initial ES cell state, and is a necessary phase transition for advancement to a more highly ordered (lower entropy) state that characterizes normal specialization.13 However, specific acquired mutations could interfere with this process and direct cells down an alternative pathway once a perturbation occurs in the meta-stable state. This alternative pathway might lead to accumulation of further mutations, loss of control over the cell cycle, and even sudden catastrophic genomic changes.

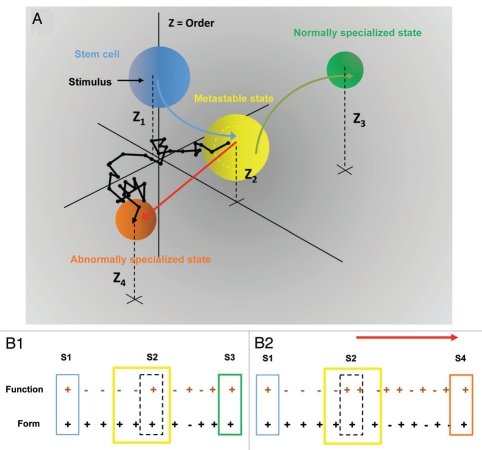

Two possible models are compatible with this scheme: form precedes function (FPF) and form follows function (FFF), where each describes the relationship between spatial (form) and transcriptional (function) networks over time during differentiation.14 For the sake of argument here we follow the FPF model. As illustrated in Figure 1, in the undifferentiated state the spatial and transcriptional networks are changing and mutually influence each other. After the initial stimulus in normal cells, the spatial network evolves until it reaches the meta-stable state. In the meta-stable state, once the spatial network has reached a particular configuration, the transcriptional network begins to change, and again they become mutually related or “align.” At this point, the cells exit the cell cycle and the system fine tunes, or feedback between the networks leads to the optimum configuration for terminal differentiation (B1).

Figure 1.

(A) Dynamics of order during cell specialization. For specific stimuli normal embryonic stem (ES) cells (blue sphere) transition to the meta-stable state (yellow sphere) and bifurcation takes place, where two possible paths emerge. One option is for cells to withdraw from the cell cycle and reach a normally specialized state (green sphere). The other option is a path to an abnormally specialized state (orange sphere), either gradually through a random path or with a catastrophic jump (red line). The meta-stable state is less ordered—higher entropy—than the initial ES cell state. The normally specialized state is more highly ordered—lower entropy—than both the ES cell state and the meta-stable state. The abnormal state also acquires a certain order—lower entropy—but it may not be ordered similarly to the normally specialized state. If the order of any state is defined by the Z axis, it follows that Z2 < Z1 < Z3 < Z4. (B1 and B2) The form precedes function (FPF) model, representing the relationship between spatial (form) and transcriptional (function) networks over time during cell specialization. (B1) schematic diagram representing normal cell specialization and (B2) abnormal cell specialization. (S1–S4) are critical states and the solid boxes represent nuclear organization as determined by the interaction between the networks for stem cell state, meta-stable state, normally specialized state and abnormally specialized state, respectively. Plus and minus symbols show changing or unchanging dynamics within each network. In the (S1) state the transcription and space networks are changing and mutually influence each other. After a stimulus only the space network changes over time until transitioning to the (S2) state. For (B1) at (S2), when the space network has reached a particular configuration, the transcription network begins to change, and again they become mutually related or they “align” and the system exits the cell cycle and fine tunes to reach an optimum configuration for terminal differentiation at (S3). For (B2), two networks never achieve an aligned state, and eventually arrive at the bifurcation, which leads to (S4), the abnormally specialized state. For some initial configurations of the spatial network the cell can undergo a catastrophic transition to (S4).

In abnormal cells the spatial and transcriptional networks may never align, though they may continue to co-evolve (B2). This divergence from the aligned state may eventually lead to an alternative quasi-stable, or less random, ordered state (the abnormal specialized state). Borrowing from the engineering field, systems that are transitioning from a less ordered state to a highly ordered state are losing controllability, i.e., the capacity to respond to specific manipulations decreases.15 A highly ordered system is much less controllable than a disordered one. Therefore, the meta-stable state is the most controllable state and more easily manipulated by external stimuli. In this context, the meta-stable state is likely to be a state that is sensitive to therapeutic interventions. Finally, while both normal and abnormal cells might share the same characteristics in early stages of differentiation before the meta-stable state is reached, the time a normal cell exists in this state is likely to be quite different from an abnormal cell. The rationale for this is as follows. For normal specialization, in response to initial stimuli, a cell will acquire a specific initial state that will result in a particular fate. As discussed above, in the normal meta-stable state, the spatial and transcriptional networks align, driving cell cycle exit and the transition to the normally specialized state. For abnormal specialization, the cell will acquire a specific initial state in response to initial stimuli (internal or external). However, in the abnormal specialization such stimuli do not result in progression to a particular cell fate. In the meta-stable state, the spatial and transcriptional networks will not align as in the normal case, but continue to evolve. During this time, the cell is more vulnerable to additional perturbations that might propel it even further from the aligned state. As a result a bifurcation takes place, initiating the transition into the abnormally specialized state. Thus, for the abnormal cell, more complex dynamics occur in the meta-stable state than for the normal cell, and therefore the time a normal cell resides in this meta-stable state is likely to be quite different from an abnormal cell.

One of the signatures of non-linear dynamical systems is that long-term behavior is sensitive to initial conditions.16 Subtle changes in certain parameters can result in catastrophic bifurcations that disrupt normal dynamics. In this context, chromosome shattering is not a genome-wide phenomenon, but involves one or two chromosomes. This might be related to the chromosome position in the interphase nucleus, which can be influenced by previously accumulated abnormalities. Thus we can argue that chromosome shattering might be the consequence of disrupted chromosome architecture. For an abnormal cell in the meta-stable state that inappropriately processes an initial stimulus, during negotiation of the mutual relationship between the spatial and transcriptional networks, the spatial network may reach a configuration—bifurcation point—that triggers the catastrophic event (see Supplement for description of how a bifurcation takes place in a dynamical system).

Outlook

Many questions remain unanswered in these studies. It is unknown for example, given the localized break points of the chromosomes, whether specific sequences are responsible for the shattering event. Also it is unclear how the chromosome fragments are reassembled and whether the process is completely random or patterned in a definable way. The hope would be that this type of study might lead to discovery of a useful clinical diagnostic marker for early detection, establish a relationship between a catastrophic event and clinical outcome, or provide further clues regarding possible interventions. Answering these questions may not be simple, and it will require a combination of appropriate sample collection in relevant patients, complex systems theory and mathematics. An important approach will be to capture the dynamic events of the nucleus during a catastrophic event. This will facilitate a deeper understanding of how disruptions in genomic organization lead to global abnormalities. Studying engineered balanced translocations may provide a more controlled external perturbation for nuclear organization that will allow further investigation of the mechanisms by which disruptions in the early stages of cancer might lead to advancement of the cancer phenotype.

One final issue is the term derived from the Greek that the authors use for the catastrophic event: chromothripsis. If their Greek root is thrypto, then the correct derivation is chromothrypsis. If it is tribo, then chromotripsis is desired. The second and third possible mechanisms the authors describe for the catastrophic event do not require external forces, but imply a mismanagement of existing forces (activities). Thus “chromosome endothrypsis” might be a more precise phrase to include specific reference to an internal (endo) and not an external (exo) force.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lindsey Muir, Rupesh Amin and Michael Morrison for discussion and critical reading of the manuscript. Special thanks to Dr. Lawrence Bliquez, Classics and Art History, University of Washington for discussion of the Greek roots of the word chromothripsis. I.R. is supported by the Mentored Quantitative Research Career Development Award (K25) from National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant 1K25DK082791-01A109 and M.G. by NIH grants R37 DK44746 and RO1 HL65440.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Stephens PJ, Greenman CD, Fu B, Yang F, Bignell GR, Mudie LJ, et al. Massive genomic rearrangement acquired in a single catastrophic event during cancer development. Cell. 2011;144:27–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meyerson M, Pellman D. Cancer genomes evolve by pulverizing single chromosomes. Cell. 2011;144:9–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Camps J, Ried T. F1000com/7848958. 2011.

- 4.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hartwell L, Hood L, Goldberg M, Reynolds N, Silver L, Veres R. Genetics: from genes to genomes. Columbus: McGraw-Hill; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao PN, Johnson RT. Mammalian cell fusion: studies on the regulation of DNA synthesis and mitosis. Nature. 1970;225:159–164. doi: 10.1038/225159a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dimitrova DS, Gilbert DM. The spatial position and replication timing of chromosomal domains are both established in early G1 phase. Molecular Cell. 1999;4:983–993. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80227-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith L, Plug A, Thayer M. Delayed replication timing leads to delayed mitotic chromosome condensation and chromosomal instability of chromosome translocations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:13300–13305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241355098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Breger KS, Smith L, Thayer MJ. Engineering translocations with delayed replication: evidence for cis control of chromosome replication timing. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:2813–2827. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stoffregen EP, Donley N, Stauffer D, Smith L, Thayer MJ. An autosomal locus that controls chromosome-wide replication timing and mono-allelic expression. Hum Mol Genet. 2011 doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hastings PJ, Ira G, Lupski JR. A microhomology-mediated break-induced replication model for the origin of human copy number variation. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:1000327. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang F, Carvalho CMB, Lupski JR. Complex human chromosomal and genomic rearrangements. Trends Genet. 2009;25:298–307. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rajapakse I, Perlman MD, Scalzo D, Kooperberg C, Groudine M, Kosak ST. The emergence of lineage-specific chromosomal topologies from coordinate gene regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:6679–6684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900986106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rajapakse I, Groudine M. On emerging nuclear order. J Cell Biol. 2011;192:711–721. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201010129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rahmani A, Ji M, Mesbahi M, Egerstedt M. Controllability of multi-agent systems from a graph-theoretic perspective. SIAM J Control Optim. 2009;48:162–186. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strogatz SH. Nonlinear dynamics and chaos—with applications to physics, biology, chemistry and engineering. Macmillan Publishers Limited. 1994:248–254. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strogatz S. Nonlinear dynamics and chaos: with applications to physics, biology, chemistry and engineering. Cambridge: Perseus Books; 1994. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.