Abstract

The Hsp90-associated cis-trans peptidyl-prolyl isomerase—FK506 binding protein 51 (FKBP51)—was recently found to co-localize with the microtubule (MT)-associated protein tau in neurons and physically interact with tau in brain tissue from humans who died from Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Tau pathologically aggregates in neurons, a process that is closely linked with cognitive deficits in AD. Tau typically functions to stabilize and bundle MTs. Cellular events like calcium influx destabilize MTs, disengaging tau. This excess tau should be degraded, but sometimes it is stabilized and forms higher-order aggregates, a pathogenic hallmark of tauopathies. FKBP51 was also found to increase in forebrain neurons with age, further supporting a novel role for FKBP51 in tau processing. This, combined with compelling evidence that the prolyl isomerase Pin1 regulates tau stability and phosphorylation dynamics, suggests an emerging role for isomerization in tau pathogenesis.

Rationale for Investigating the Chaperone/Tau Interface

In Alzheimer’s disease, cognitive dysfunction and neuronal loss are critically linked to the intracellular accumulation of the microtubule associated protein tau into filamentous tangles [1–5]. Tau pathology is also found in approximately 15 other neurodegenerative diseases, some caused by mutations in the tau gene [6]. Genome-wide association studies show that tau expression is increased in sporadic Parkinson’s disease (PD) [7].

Abnormal processing and accumulation of tau are necessary for tangle formation. Recent evidence suggests that proteins able to constrain the structural freedom of tau are essential for tau processing and participate in its accumulation [8–22]. Interactions of tau with a specific family of proteins termed cis-trans peptidyl-prolyl isomerases (PPIases) has already revealed the importance of this protein family to regulate tau phosphorylation cycles and its overall stability [19, 23, 24]. There are approximately 30 PPIases in the human proteome that are known and each of these may play a role in regulating tau activity and stability. Our goal is to review that which is already known about tau and PPIases, as well as describe other PPIases that may be implicated in tau pathogenesis in the future.

Cis-Trans Peptidyl-Prolyl Isomerization of Tau

A high percentage of prolines are common to most intrinsically disordered proteins, and tau is no exception [25]. Nearly 10% of full-length tau is composed of proline residues, and more than 20% of the residues between I151 and Q244 are proline. Most of the known functions of tau are mediated through MT binding domains distal to this proline-rich region. However many disease-associated phosphorylation events that seed tau tangle formation occur at proline-directed serine (S) and threonine (T) residues in this proline-rich region (Figure 1). This strongly suggests that important structural changes in the proline rich region of tau are regulating tangle formation. In particular, cis-trans isomerization around these prolines modulates protein phosphatase binding and activity at specific S/T sites. It is well established that peptidyl-prolyl isomerase 1 (Pin1) regulates tau phosphorylation in concert with protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), specifically at T231 and T212 [26]. Recent findings by our group suggest that FKBP51 has a similar activity to Pin1; however, unlike Pin1, FKBP51 coordinates with Hsp90 to isomerize tau. It also cooperates with distinct protein phosphatases that may also be novel participants in tau biology [27]. Thus, prolyl isomerization of tau is a major activity that regulates tau function, but this family of proteins is just beginning to be explored in this capacity.

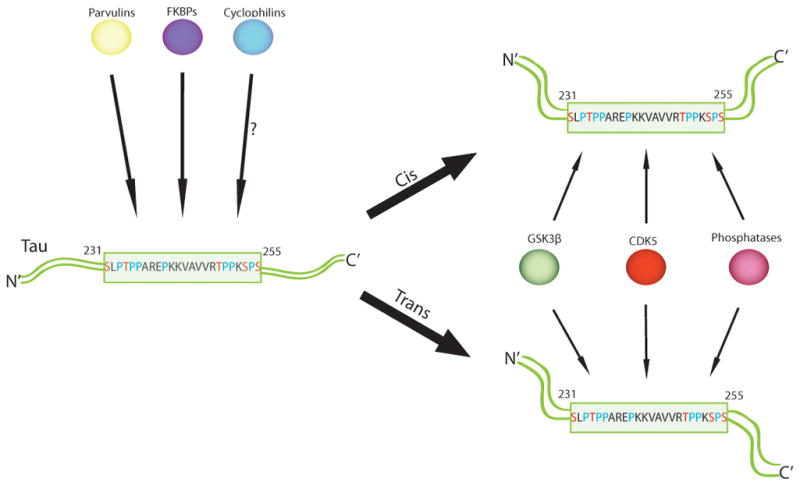

Figure 1. PPIases isomerize tau within its proline-rich region to regulate tau phosphorylation dynamics.

The proline-rich region of tau, which spans amino acids 231 to 255, contains a number of Ser/Thr phosphorylation sites that have been implicated in disease. Both CdK5 and GSK3β phosphorylate tau at proline-directed Ser/Thr sites and phosphatases can also remove these phosphate motifs. Thus, PPIases may play a critical part in regulating phosphorylation dynamics of tau.

Pin1 and Parvulin

Parvulin was the first PPIase discovered in E. coli. The human orthologue of parvulin is Pin1. Like other PPIases, Pin1 catalyzes the isomerization of the peptide bonds between pSer/Thr-Pro in proteins. It has been most tightly coupled to regulation of DNA damage repair mechanisms and cell cycle transitions; however Pin1 co-localizes with phosphorylated tau in AD brains and up-regulation of Pin1 reduces pathogenic tau species (for extensive review of the role of Pin1 in tau biology see [23, 24]). Oxidative modifications to Pin1 that occur in AD brain down-regulate its function. Pin1 belongs to the Parvullin family of proteins and possesses important post-phosphorylation regulatory activity. Pin1 cooperates with proline-directed kinases, including CdK5 and GSK3β, each of which is implicated in tau pathogenesis by promoting hyper-phosphorylation. Pin1 also cooperates with protein phosphatases to regulate tau phosphorylation. Thus, Pin1 alters the conformation of tau, allowing other proteins to dynamically regulate it phosphorylation state. Interestingly, tau that is mutated at residue 301 from proline to leucine, a mutation that is the most common cause of human tauopathy, is actually stabilized by Pin1, while wildtype tau clearance is promoted by Pin1.

FK-506 Binding Proteins (FKBPs) and Immunophilins

The drug FK-506 also known as tacrolimus, is a drug largely known for its role as an immunosuppressant. FK-506 inhibits that production of a number of cytokines that facilitate the adaptive immune response. Much of the immunosuppressive activity of FK-506 is ascribed to its inhibition of a particular immunophilin, the FK-506 binding protein 12 (FKBP12) [28]. FKBP12 is a peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase that is vital for protein transportation and folding, particularly in immune cells. Not only is it abundant in immune cells in the brain, but it is also found in neuronal cell bodies and neurites. FKBP12 granules have been found within neurofibrillary tangles in the hippocampal CA1 subfield, subiculum, entorhinal cortex and angular gyrus of AD patients. Through immunoflourescence, FKBP12 and tau were found concurrently within NFTs. These results suggest that FKBP12 may be involved in neuronal cytoskeletal organization and in the metabolism of tau protein in AD [29]. In fact, treating mice transgenic for human mutant tau with FK-506, reduced tau pathology and cognitive deficits [30]. This rescue was largely attributed to the immunosuppressant activity of FK-506, working through FKBP12. However, there have been molecules identified that can inhibit FKBP12 without the immunosuppressant activity, similar to FK-506; and these molecules have demonstrated positive effects in both neuronal health and calcineurin binding [31, 32].

FKBP52, another member of the FK506-binding protein family, has largely been linked to steroid hormone receptor maturation [33, 34]. FKBP52, together with its counterpart FKBP51, contain tetratricopeptide repeat domains, which uniquely allows each protein to interact with the two major chaperone scaffolds, Hsp90 and Hsp70; neither FKBP12 nor Pin1 possess this property. This relationship of both FKBP51 and 52 with steroid hormone receptors and Hsp90 has lead to a number of studies about their role in sexual development and fertility. However, FKBP52 is also abundantly found in the brain, and it binds specifically to tau when it is hyper-phosphorylated [35]. FKBP52 moves towards neurites and concentrates in terminal axons. Neurite outgrowth is favored by FKBP52 over-expression and impaired by FKBP52 knockdown [36]; also selective ligands can demonstrate neurite effects similar to FKBP52 over-expression [37]. FKBP52 prevents tau from promoting microtubule assembly in vitro [38]. Thus, activating FKBP52 may be a novel therapeutic strategy for tauopathies in the future.

FKBP51, which is 70% similar to FKBP52, has a much less robust role in fertility and sexual development than FKBP52 [39]. In fact, until recently, the role of FKBP51 was largely unknown. It is now thought that FKBP51 is very involved with brain function in adulthood, perhaps antagonizing the effects of FKBP52 that is dominant during pubescence. Interestingly, genetic variance within the FKBP51 gene (FKBP5) is associated with the frequency of depressive episodes [40]. This activity has been linked to glucocorticoid receptor activity. Thus, an important role for FKBP51 in the brain is emerging. Recent work suggests that FKBP51 can prevent tau clearance and has the ability to regulate its phosphorylation [19]. FKBP51 knockdown reduced tau levels, while FKBP52 knockdown preserved tau in cells. FKBP51 enhanced the association of tau with the chaperone protein Hsp90, which is critical for tau triage decisions [19]. FKBP51 also cooperated with tau to stabilize microtubules. Moreover, FKBP51 PPIase activity was shown to be essential for most aspects of tau regulation [19]. FKBP51 also maintained expression levels throughout the neuronal body, while FKBP52 accumulates specifically within terminal axons [36]. Neurite outgrowth is favored by FKBP51 knockdown, but impaired by its overexpression. Thus the balance between levels and distribution of FKBP51 and FKBP52 could be important factors for neuronal mechanisms.

Other FKBPs exist as well. For example, FKBP38 is highly expressed in the brain [41] and has been implicated as necessary for neural tube development [42]. This protein lacks a tetratricopeptide repeat domain, similar to FKBP12, and therefore cannot interact with Hsp90 or Hsp70. Nevertheless, a specific inhibitor of FKBP38 was found to be neuroprotective against ischemia. In fact, inhibition of this protein was actually neurotrophic following ischemia [43]. There a total of 8 FKBP proteins listed on the Online Mendelian Inheritance of Man database (OMIM). Some of these are specific to distinct organelles and tissue types; however it is possible that each of these could affect prolyl isomerization of tau if proximity could be achieved. This family of relatively understudied proteins could be essential drug targets for future development.

Cyclophilins

The final family of peptidyl-prolyl isomerases that we will address here is also the largest family of these enzymes; the cyclophilins. The first cyclophilin, Clyclophilin A, identified was also the original PPIase enzyme identified, as it was a cytosolic binder of the immunosuppressant cyclosporine A [44–47]. Multiple other cyclophilin family members have since been identified. The known and related genes are listed in Table 1. While these proteins have yet to demonstrate a regulatory function for tau, it is highly likely that at least some will influence its isomerization. Cyclophilin A (PPIA), B (PPIB), and D (PPID) are all abundant in the brain making these the most likely to regulate tau structure.

Table 1.

Cyclophilins and related proteins.

| Gene | Protein | Normalized (approx.) Hybridization Intensity of Gene Expression Profile in Human Brain [68, 69] | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| PPIF | Cyclophilin F/Cyp3 | 500 | [62] |

| PPID | Cyclophilin D/Cyp40 | 1000 | [54–58, 70] |

| PPIE | Cyclophilin E/Cyp33 | 100 | [71] |

| PPIA | Cyclophilin A | 6000 | [50, 51, 53] |

| PPIH | Cyclophilin H | 100 | |

| PPIC | Cyclophilin C | 75 | |

| PPIB | Cyclophilin B | 1000 | [59–61] |

| PPIG | Cyclophilin G | 100 | |

| PPIL1 | CYPL1 | 200 | [63] |

| PPIL2 | CYP60 | 50 | [64] |

| PPIL3 | CYPJ | 300 | [72] |

| PPIL4 | --NA-- | 100 | [65] |

| COAS1 | KIAA1245 | ??? | [66] |

| COAS2 | PPIAL4A | ??? | [67] |

| ” | PPIAL4B | ??? | [67] |

| ” | PPIAL4C | ??? | [67] |

| ” | PPIAL4D | ??? | [67] |

| ” | PPIAL4E | ??? | [67] |

| ” | PPIAL4F | ??? | [67] |

| ” | PPIAL4G | ??? | [67] |

+/− indicate relative level above (+) or below (−) median levels. Those marked with (???) indicate no gene expression profile has been conducted.

PPIA has primarily been studied in the context of HIV and other viral factors (reviewed in [48, 49]). It has also been shown to enhance the stress response in a yeast model [50]. Though it has been shown to exist in extremely high levels in the brain, no characterization directly involving tau has been performed. PPIA has been shown to regulate a tau phosphatase, calcineurin (reviewed in [49]). A study showed that even though calcineurin activity was decreased in AD, calineurin levels as well as PPIA levels were no different between AD and normal tissue [51]. Inhibitors of PPIA have been generated [52]. Also, PPIA was found to bind dynein motor complexes and is involved in axonal transport [53].

PPID, one of the cyclophilins abundant in the brain, has been linked to axonal degenerationl; this action was demonstrated to occur through internal destabilization rather than external tau related mechanisms [54]. However, PPID has a TPR domain, linking it to Hsp70 and Hsp90 [55, 56]. Moreover PPID regulates Hsp90 ATPase activity (reviewed in [49, 57, 58]). Thus, manipulations of PPID could likely lead to alterations in tau, but these changes could be through regulation of Hsp90 ATPase activity, rather than tau isomerization. Nevertheless, PPID is an interesting candidate from this family that warrants further characterization.

PPIB was found to bind DnaK from E. coli, the equivalent of mammalian Hsp70 [59]. Thus PPIB may be a potential target for chaperone manipulation leading to changes in tau stability. PPIB is also involved in multiple steps leading to synaptic vesicle release, specifically the isomerization of integral membrane proteins such as synapsin [60, 61]. The prevalence of PPIB in neuronal function again suggests the possibility of a tau interaction, thus making it a potential drug target.

PPIF is strictly mitochondrial [62]. Thus it is not likely to regulate tau interactions. CYPL1 was identified from fetal brain samples suggesting a role in neuronal development [63]. CYP60 was identified to not be a genetic factor in AD. CYPJ was also identified from human fetal brain [64]. PPIL4 was also characterized from human fetal brain; however it lacks a “classical” cyclophilin isomerase motif [65]. COAS1 is found in all cells but at very low levels; however the highest signal for COAS1, as assessed by RT-PCR, came from amygdala [66]. COAS2, PPIAL4A, or PPIase A Like 4A, were each detectable in most tissues with highest levels in the brain [67]. Thus, the cyclophilin family represents a robust pool of new candidates that may regulate tau biology.

Conclusions

Identifying new molecular targets that can remove or repair abnormal tau is essential for developing the next generation of therapeutics for AD, PD and other tauopathies. PPIases are a unique family of targets in that these enzymes can dramatically alter the conformation of proteins without the consumption of energy. Over the past decade, Pin1 has been shown to regulate tau in multiple ways, and strategies to regulate Pin1 activity are in development. We have shown that the Hsp90 co-chaperone FKBP51 may be such a target. FKBP51 co-localizes with tau in neurons and associates with tau from human AD brain. We have defined a novel role for FKBP51 in human neurodegenerative disease that was, in fact, the first description of any functional role for the PPIase activity of FKBP51 in neurobiology. These studies underscore the potentially vast pool of therapeutic candidates for tauopathies that exists within the prolyl isomerase family.

References

- 1.Oddo S, et al. Triple-transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease with plaques and tangles: intracellular Abeta and synaptic dysfunction. Neuron. 2003;39(3):409–21. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00434-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frautschy SA, Baird A, Cole GM. Effects of injected Alzheimer beta-amyloid cores in rat brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88(19):8362–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.19.8362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roberson ED, et al. Amyloid-beta/Fyn-induced synaptic, network, and cognitive impairments depend on tau levels in multiple mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2011;31(2):700–11. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4152-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mukaetova-Ladinska EB, et al. Alpha-synuclein inclusions in Alzheimer and Lewy body diseases. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2000;59(5):408–17. doi: 10.1093/jnen/59.5.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82(4):239–59. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hardy J, et al. Tangle diseases and the tau haplotypes. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20(1):60–2. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000201853.54493.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simon-Sanchez J, et al. Genome-wide association study reveals genetic risk underlying Parkinson’s disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41(12):1308–12. doi: 10.1038/ng.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shimura H, Miura-Shimura Y, Kosik KS. Binding of tau to heat shock protein 27 leads to decreased concentration of hyperphosphorylated tau and enhanced cell survival. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(17):17957–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400351200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shimura H, et al. CHIP-Hsc70 complex ubiquitinates phosphorylated tau and enhances cell survival. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(6):4869–76. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305838200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carrettiero DC, et al. The cochaperone BAG2 sweeps paired helical filament-insoluble tau from the microtubule. J Neurosci. 2009;29(7):2151–61. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4660-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petrucelli L, et al. CHIP and Hsp70 regulate tau ubiquitination, degradation and aggregation. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13(7):703–14. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dickey CA, et al. Pharmacologic reductions of total tau levels; implications for the role of microtubule dynamics in regulating tau expression. Mol Neurodegener. 2006;1:6. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dickey CA, et al. HSP induction mediates selective clearance of tau phosphorylated at proline-directed Ser/Thr sites but not KXGS (MARK) sites. FASEB J. 2006;20(6):753–5. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5343fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dickey CA, et al. Akt and CHIP coregulate tau degradation through coordinated interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(9):3622–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709180105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dickey CA, Petrucelli L. Current strategies for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and other tauopathies. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2006;10(5):665–76. doi: 10.1517/14728222.10.5.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dickey CA, et al. Deletion of the ubiquitin ligase CHIP leads to the accumulation, but not the aggregation, of both endogenous phospho- and caspase-3-cleaved tau species. J Neurosci. 2006;26(26):6985–96. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0746-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dou F, et al. Chaperones increase association of tau protein with microtubules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(2):721–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242720499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luo W, et al. Roles of heat-shock protein 90 in maintaining and facilitating the neurodegenerative phenotype in tauopathies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(22):9511–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701055104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jinwal UK, et al. The Hsp90 cochaperone, FKBP51, increases Tau stability and polymerizes microtubules. J Neurosci. 2010;30(2):591–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4815-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jinwal UK, et al. Hsp70 ATPase Modulators as Therapeutics for Alzheimer’s and other Neurodegenerative Diseases. Mol Cell Pharmacol. 2010;2(2):43–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jinwal UK, et al. Hsc70 rapidly engages tau after microtubule destabilization. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(22):16798–805. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.113753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang CL, Yang HL. Conserved residues in the subunit interface of tau glutathione s-transferase affect catalytic and structural functions. J Integr Plant Biol. 2011;53(1):35–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2010.01005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu KP, Zhou XZ. The prolyl isomerase PIN1: a pivotal new twist in phosphorylation signalling and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8(11):904–16. doi: 10.1038/nrm2261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu PJ, et al. The prolyl isomerase Pin1 restores the function of Alzheimer-associated phosphorylated tau protein. Nature. 1999;399(6738):784–8. doi: 10.1038/21650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Romero PR, et al. Alternative splicing in concert with protein intrinsic disorder enables increased functional diversity in multicellular organisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(22):8390–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507916103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galas MC, et al. The peptidylprolyl cis/trans-isomerase Pin1 modulates stress-induced dephosphorylation of Tau in neurons. Implication in a pathological mechanism related to Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(28):19296–304. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601849200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pei H, et al. FKBP51 affects cancer cell response to chemotherapy by negatively regulating Akt. Cancer Cell. 2009;16(3):259–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harding MW, et al. A receptor for the immunosuppressant FK506 is a cis-trans peptidyl-prolyl isomerase. Nature. 1989;341(6244):758–60. doi: 10.1038/341758a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sugata H, et al. A peptidyl-prolyl isomerase, FKBP12, accumulates in Alzheimer neurofibrillary tangles. Neurosci Lett. 2009;459(2):96–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.04.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoshiyama Y, et al. Synapse loss and microglial activation precede tangles in a P301S tauopathy mouse model. Neuron. 2007;53(3):337–51. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Armistead DM, et al. Design, synthesis and structure of non-macrocyclic inhibitors of FKBP12, the major binding protein for the immunosuppressant FK506. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1995;51(Pt 4):522–8. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994014502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao L, et al. FK506-binding protein ligands: structure-based design, synthesis, and neurotrophic/neuroprotective properties of substituted 5,5-dimethyl-2-(4-thiazolidine)carboxylates. J Med Chem. 2006;49(14):4059–71. doi: 10.1021/jm0502384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davies TH, Ning YM, Sanchez ER. Differential control of glucocorticoid receptor hormone-binding function by tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) proteins and the immunosuppressive ligand FK506. Biochemistry. 2005;44(6):2030–8. doi: 10.1021/bi048503v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davies TH, Sanchez ER. Fkbp52. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;37(1):42–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chambraud B, et al. A role for FKBP52 in Tau protein function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(6):2658–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914957107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quinta HR, et al. Subcellular rearrangement of hsp90-binding immunophilins accompanies neuronal differentiation and neurite outgrowth. J Neurochem. 2010;115(3):716–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06970.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruan B, et al. Binding of rapamycin analogs to calcium channels and FKBP52 contributes to their neuroprotective activities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(1):33–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710424105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chambraud B, et al. The immunophilin FKBP52 specifically binds to tubulin and prevents microtubule formation. FASEB J. 2007;21(11):2787–97. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7667com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yong W, et al. Essential role for Co-chaperone Fkbp52 but not Fkbp51 in androgen receptor-mediated signaling and physiology. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(7):5026–36. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609360200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Binder EB, et al. Association of FKBP5 polymorphisms and childhood abuse with risk of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in adults. JAMA. 2008;299(11):1291–305. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.11.1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nielsen JV, et al. Fkbp8: novel isoforms, genomic organization, and characterization of a forebrain promoter in transgenic mice. Genomics. 2004;83(1):181–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shirane M, et al. Regulation of apoptosis and neurite extension by FKBP38 is required for neural tube formation in the mouse. Genes Cells. 2008;13(6):635–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2008.01194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Edlich F, et al. The specific FKBP38 inhibitor N-(N′,N′-dimethylcarboxamidomethyl)cycloheximide has potent neuroprotective and neurotrophic properties in brain ischemia. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(21):14961–70. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600452200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fischer G, Bang H, Mech C. Determination of enzymatic catalysis for the cis-trans-isomerization of peptide binding in proline-containing peptides. Biomed Biochim Acta. 1984;43(10):1101–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fischer G, et al. Cyclophilin and peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase are probably identical proteins. Nature. 1989;337(6206):476–8. doi: 10.1038/337476a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Handschumacher RE, et al. Cyclophilin: a specific cytosolic binding protein for cyclosporin A. Science. 1984;226(4674):544–7. doi: 10.1126/science.6238408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takahashi N, Hayano T, Suzuki M. Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase is the cyclosporin A-binding protein cyclophilin. Nature. 1989;337(6206):473–5. doi: 10.1038/337473a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ortiz M, et al. Patterns of evolution of host proteins involved in retroviral pathogenesis. Retrovirology. 2006;3:11. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-3-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ke H, Huai Q. Crystal structures of cyclophilin and its partners. Front Biosci. 2004;9:2285–96. doi: 10.2741/1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim IS, et al. A cyclophilin A CPR1 overexpression enhances stress acquisition in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cells. 2011;29(6):567–74. doi: 10.1007/s10059-010-0071-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lian Q, et al. Selective changes of calcineurin (protein phosphatase 2B) activity in Alzheimer’s disease cerebral cortex. Exp Neurol. 2001;167(1):158–65. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Barinaga M. The secret of saltiness. Science. 1991;254(5032):654–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1948045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Galigniana MD, et al. Cyclophilin-A is bound through its peptidylprolyl isomerase domain to the cytoplasmic dynein motor protein complex. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(53):55754–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406259200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Barrientos SA, et al. Axonal degeneration is mediated by the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. J Neurosci. 2011;31(3):966–78. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4065-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pirkl F, Buchner J. Functional analysis of the Hsp90-associated human peptidyl prolyl cis/trans isomerases FKBP51, FKBP52 and Cyp40. J Mol Biol. 2001;308(4):795–806. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li J, Richter K, Buchner J. Mixed Hsp90-cochaperone complexes are important for the progression of the reaction cycle. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18(1):61–6. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ratajczak T, et al. Cyclophilin 40: an Hsp90-cochaperone associated with apo-steroid receptors. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41(8–9):1652–5. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kimmins S, MacRae TH. Maturation of steroid receptors: an example of functional cooperation among molecular chaperones and their associated proteins. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2000;5(2):76–86. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(2000)005<0076:mosrae>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Naylor DJ, Hoogenraad NJ, Hoj PB. Characterisation of several Hsp70 interacting proteins from mammalian organelles. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1431(2):443–50. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(99)00070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lane-Guermonprez L, et al. Synapsin associates with cyclophilin B in an ATP-and cyclosporin A-dependent manner. J Neurochem. 2005;93(6):1401–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Morot-Gaudry-Talarmain Y. Physical and functional interactions of cyclophilin B with neuronal actin and peroxiredoxin-1 are modified by oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47(12):1715–30. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bergsma DJ, et al. The cyclophilin multigene family of peptidyl-prolyl isomerases. Characterization of three separate human isoforms. J Biol Chem. 1991;266(34):23204–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ozaki K, et al. Cloning, expression and chromosomal mapping of a novel cyclophilin-related gene (PPIL1) from human fetal brain. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1996;72(2–3):242–5. doi: 10.1159/000134199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Carson R, et al. Variation in RTN3 and PPIL2 genes does not influence platelet membrane beta-secretase activity or susceptibility to alzheimer’s disease in the northern Irish population. Neuromolecular Med. 2009;11(4):337–44. doi: 10.1007/s12017-009-8080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zeng L, et al. Molecular cloning, structure and expression of a novel nuclear RNA-binding cyclophilin-like gene (PPIL4) from human fetal brain. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 2001;95(1–2):43–7. doi: 10.1159/000057015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nagase T, et al. Prediction of the coding sequences of unidentified human genes. XV. The complete sequences of 100 new cDNA clones from brain which code for large proteins in vitro. DNA Res. 1999;6(5):337–45. doi: 10.1093/dnares/6.5.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Meza-Zepeda LA, et al. Positional cloning identifies a novel cyclophilin as a candidate amplified oncogene in 1q21. Oncogene. 2002;21(14):2261–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shmueli O, et al. GeneNote: whole genome expression profiles in normal human tissues. C R Biol. 2003;326(10–11):1067–72. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2003.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yanai I, et al. Genome-wide midrange transcription profiles reveal expression level relationships in human tissue specification. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(5):650–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chen S, et al. Differential interactions of p23 and the TPR-containing proteins Hop, Cyp40, FKBP52 and FKBP51 with Hsp90 mutants. Cell Stress Chaperones. 1998;3(2):118–29. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(1998)003<0118:diopat>2.3.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mi H, et al. A nuclear RNA-binding cyclophilin in human T cells. FEBS Lett. 1996;398(2–3):201–5. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01248-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhou Z, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel peptidylprolyl isomerase (cyclophilin)-like gene (PPIL3) from human fetal brain. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 2001;92(3–4):231–6. doi: 10.1159/000056909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]