Abstract

Plants have evolved efficient strategies for utilizing nutrients in the soil in order to survive, grow and reproduce. Inorganic phosphate (Pi) is a major macroelement source for plant growth; however, the availability and distribution of Pi are varying widely across locations. Thus, plants in many areas experience Pi deficiency. To maintain cellular Pi homeostasis, plants have developed a series of adaptive responses to facilitate external Pi acquisition, limit Pi consumption and adjust Pi recycling internally under Pi starvation conditions. This review focuses on the molecular regulators that modulate Pi starvation-induced root architectural changes.

Key words: auxin, phosphate deficiency, root system architecture modulation

Introduction

Although a sufficient supply of inorganic phosphate (Pi) is vital to plants, plants often experience fluctuations in Pi availability or even chronic Pi limitation.1,2 Pi is important for the production of nucleic acids, phospholipids, proteins and small molecules.3 Because plants are sessile organisms, they have evolved an array of adaptive responses to adjust their growth, development and metabolic activities. These adjustments include the following: (1) enhanced top soil foraging by modulating root architecture components, such as increasing the growth of lateral roots and number of root hairs to increase the absorption surface area, and by establishing a symbiotic association with mycorrhizal fungi; (2) improved Pi uptake by activating Pi transporters and increased Pi recycling and scavenging for phosphate from intra- and extracellular organic sources by secreting organic acid, ribonuclease and acid phosphatases; and (3) optimization of Pi use by a wide range of metabolic alterations.4 It is presumed that the primary root tip senses low Pi availability and initiates a signaling cascade.

The application of phosphorus (P) fertilizer can compensate for low Pi availability, but the global resource of P from rock is not renewable and may be depleted in 50–100 years.5 Although P is exogenously fertilized, most P is integrated with Ca, Fe or Al salts and formed as organic molecules, whereas only orthophosphate, mainly H2PO4− and HPO42-, is available for plants. For a typical plant, Pi are accumulated in concentration of about 1 µM in the soil, 10,000 µM in the cells and 400 µM in the xylem. To understand the strategies used by plants to acquire and utilize Pi efficiently is essential for the rational breeding and engineering of crop plants with greater capacity to acquire, store and recycle soil Pi. This review is focused on recent advances in our understanding of the mechanism of root architecture remodeling under Pi deficiency.

Regulators Involved in Pi Starvation-Induced Root System Architecture Modulation

When a primary or lateral root encounters low Pi levels, its growth is restrained. This inhibition results from reduced cell elongation6 and meristem activity.7–11 This response requires physical contact between the root tip and the low-Pi medium.9,12 CycB1;1::GUS seedlings, which identifies dividing cells at the G2/M transition, demonstrates that cells in the root tips ceased dividing when the root tips encountered the low-Pi medium.9 Thus, it is presumed that a local Pi sensing mechanism exists in the roots, whereas alterations in the development of lateral roots are regulated by systemic Pi status.13 Auxin is believed to play a central role in root architecture modulation during Pi starvation because a change in auxin distribution was observed during Pi starvation,11,14,15 auxin-accumulating YUCCA1-overexpressing plants16 exhibited hyperresponsivenesss to Pi starvation,11 and both TIR1 (transport inhibitor response 1)- and ARF19 (auxin response factor 19)-dependent auxin signaling are implicated in the regulation of lateral root development under Pi deficiency.17 Exogenous auxin treatment in plants grown in low Pi conditions drastically prevents the growth of primary roots and induces the formation of lateral roots.11,18 Furthermore, mutations in BIG, which encodes a large calossin-like protein that is required for normal polar auxin transport,19 reduced lateral root formation in low Pi conditions.15 Auxin transport and BIG function have fundamental roles in pericycle cell activation, which stimulates lateral root primordia formation and promotes root hair elongation.15

Several mutants have been isolated and studied to understand Pi starvation-induced root architecture modulation. The EMS-induced Arabidopsis pdr2 (phosphate deficiency response 2) mutant, which has impaired ER-localized P5-type ATPase function,20 exhibited reduced primary root growth and root cell division and elongation under Pi deficiency.21,22 The pdr2 mutant was not affected by the P concentration within the root tip or by Pi uptake rates, excluding a defect in high-affinity Pi acquisition, suggesting that the pdr2 mutant phenotype is caused by a defect in sensing the local external Pi concentration.22 PDR2 regulates stem cell differentiation and meristem activity through SCR and SHR,20 which are GRAS family members and key regulators of radial root patterning.23,24

Genetic data suggest an interaction between PDR2 and LPR1/LPR2 (low phosphate root1/2), which encode multi-copper oxidase,9 in an ER-resident pathway;20 however, LPR1 and PDR2 could have opposing functions in regulating the root growth response to Pi starvation.25 Quantitative trait loci analyses revealed that LPR loci were detected in a recombinant inbred line population derived from a cross between the Pi starvation-insensitive accession Bay-0 (Bayreuth) and the Pi starvation-sensitive accession Sha (Shahdara) in Arabidopsis.9 LPR1 is expressed in the root tip, including the meristem and root cap. Mutations in LPR1 and LPR2 strongly reduced the Pi-induced inhibition of primary root growth,9,25 suggesting that LPRs modify or activate a compound in the root tip that inhibits meristematic growth. The function of LPR1 is genetically independent on SIZ1 (SAP and Miz1) in response to Pi starvation.25

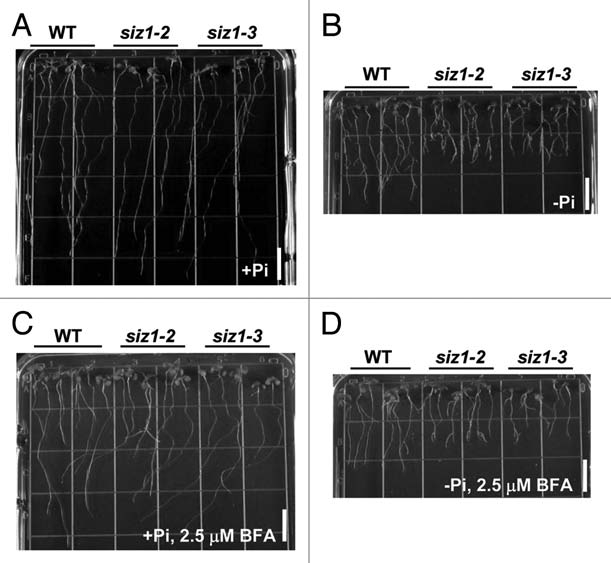

SIZ1 is a SUMO (small ubiquitin-related modifier) E3 ligase that is involved in Pi starvation responses26 as well as several stress responses27–33 and flowering.34 The siz1 mutation exaggerates prototypical Pi starvation responses; including cessation of primary root growth, extensive lateral root development and root hair development.26 Root architecture modulation is likely caused by the regulation of auxin patterning in response to Pi limitation.11 Application of 1-N-naphthylphthalamic acid, an inhibitor of auxin efflux activity, reduced the Pi starvation-induced lateral root elongation effects of siz1. Treatment with brefeldin A, an inhibitor of vesicle trafficking, also reduced the lateral root formation induced by siz1 in response to Pi limitation (Fig. 1). Brefeldin A disrupts the polarization of the auxin transporter PIN1, resulting in PIN1 being equally distributed along the entire cell surface and reduced auxin efflux activity.35 SIZ1 negatively regulates root architecture modulation under low Pi by controlling auxin patterning.

Figure 1.

The siz1 mutants exhibited exaggerated prototypical Pi starvation responses, including cessation of primary root elongation and extensive lateral root development (B), although no obvious difference between wild-type and siz1 seedlings under Pi sufficient condition (A). Treatment with brefeldin A (BFA) suppressed lateral root formation in low Pi (D) of wild-type and siz1 seedlings, compared to that in high Pi condition (C). Bars indicate 1 cm length.

Microarray analyses demonstrated that genes encoding EXP17 (expansin 17), GH1 (glycosyl hydrolase 1), embryo-abundant, dehydrin xero 2, UGT73B4 (UDP-glycosyltransferase73B4) and PGIP (polygalacturonase inhibiting protein) as well as GST (glutathione transferase) were induced by phosphate deficiency, auxin treatment and the siz1 mutation.11 UGT73B4, PGIP and GST are known to be involved in disease resistance. Cell wall remodeling enzymes, such as pectate lyase, polygalacturonase, xyloglucan:xyloglucosyl transferases, expansins and GHs, are expressed in root cells adjacent to new lateral root primordia, presumably to promote the emergence of LR elongation.17,36 For cell growth, the cell wall must be loosened. Expansins are plant cell wall-loosening proteins involved in cell enlargement and cell modification.37 GHs have large families and diverse functions.38 GH family 1 includes β-mannosidase, β-glucosidase, thioglucosidase and glycosyltransferases. β-Glucosidase hydrolyses the exo-cellulase product into individual monosaccharides. The precise biological function of these proteins is unknown, but it is possible that some of these products are involved in cell wall loosening, resulting in elongation of the lateral root.

Three transcription factors, WRKY75, Cys2/His2 zinc-finger transcription factor ZAT6 and MYB62, have been identified39–41 on the basis of microarray data.42 WRKY75 RNAi-lines exhibit increased growth of lateral roots and the number of root hairs. WRKY75 expression was induced by Pi limitation. Because WRKY75 is also involved in disease resistance,43 a relationship may exist between nutrient deficiency and defense mechanisms. ZAT6 was induced during Pi starvation and became localized to the nucleus.40 Because the RNAi suppression of ZAT6 was lethal, the gene is vital for plants. Overexpression of ZAT6 resulted in a constitutive exaggerated Pi starvation-induced root architecture modulation with a significant decrease of primary root length and the number of lateral roots, but with a strong increased lateral root length.40 The target genes for ZAT6 are not yet known, but ZAT6 may function as a transcriptional repressor to repress primary root growth during Pi deficiency. Pi starvation also induced MYB62 in the leaves.41,42 MYB62-overexpressing plants exhibited shorter lateral roots, diminished shoot growth rate, decreased Pi accumulation in the shoot and attenuated regulation of Pi starvation-induced genes.41 Interestingly, the growth retardation induced by MYB62 overexpression was reversed by the application of gibberellic acid, suggesting that MYB62 also regulates GA biosynthesis. Other microarray data demonstrated that the expression of bHLH32 (basic helix-loop-helix) transcription factor was induced after 48 h of Pi starvation.44 The bhlh32 mutant exhibited increased Pi accumulation, higher anthocyanin levels and increased numbers of root hairs in Pi-sufficient conditions and also higher activity of PPCK, a protein kinase that activates PEP carboxylase,45 suggesting that bHLH32 is a repressor of the Pi deficiency response. Because WRKY75, bHLH32 and MYB62, which appear to be negative regulators of the Pi starvation response, were induced by Pi deficiency, these factors may be involved in feedback mechanisms that attenuate the response in certain tissues.

The mutation in RPD (phosphate root development), which encodes an AINTEGUMENTA-like protein, repressed the development of primary and lateral roots under Pi starvation.46 Because Pi influx and Pi starvation-inducible gene expression were similar in wild-type and the prd plants in response to Pi starvation, it is suggested that PRD is not a checkpoint gene for Pi starvation responses but acts as a regulator of root architectural responses to Pi starvation.46

The nuclear actin-related protein ARP6 is required for the SWR1 chromatin-remodeling complex, which regulates transcription via deposition of the H2A.Z histone variant into chromatin. Mutation of ARP6 decreased H2A.Z abundance in a number of Pi starvation-responsive genes, resulting in increases in gene transcription and correlating with Pi starvation-related phenotypes, such as shortened primary roots and increases in the number and length of root hairs.47 These results suggest that SWR1-dependent H2A.Z deposition is required for the modulation of root system architecture as well as the regulation of Pi starvation-induced gene expression.

Several mutant genes remain unidentified. The lpi (low phosphorus-insensitive) mutants, representing four different genetic loci, were isolated from an EMS-mutagenized population due to their ability to maintain primary root growth, leading to a long primary root, during Pi deficiency.7 These mutants exhibited reduced induction in the expression of several Pi starvation-induced genes. Gene expression profiling with the lpi4 mutant demonstrated that the large number of genes related to oxidative stress were downregulated in the root tip of lpi4 plants.48 Dramatic decrease in H2O2 levels occur during the meristem exhaustion process in the primary root tip of the wild-type plants grown in low Pi conditions, whereas in lpi4 plants, H2O2 accumulation was observed even under Pi deficiency, suggesting that Pi starvation triggers alterations in redox status, leading to the loss of root elongation and meristem maintenance.48 Thus, an appropriate redox status may be required for primary root meristem maintenance.

Several lines of evidence suggest that signaling mechanisms for Pi accumulation in the shoot and root architecture modulation may not be linked because the pho1 and pho2 mutants, which accumulate less and more Pi, respectively,49,50 exhibited a similar root phenotype as wild-type seedlings. miRNA399 overexpression, which targets PHO2 encoding the ubiquitin E2 conjugate enzyme UBC24 and results in increased accumulation of Pi,51,52 did not result in a hyperresponsive root architecture phenotype in plants.51 miRNA399-PHO2 signaling is regulated by the MYB-type transcription factor PHR1.53 The phr1 mutant accumulated less Pi but exhibited a similar phenotype of root architecture as wild-type plants.7,54 Thus, it is plausible that the PHR1-miRNA399-PHO2 pathway controls Pi accumulation in shoots but is not involved in the regulation of root architecture modulation.

Phytohormones and Modulation of Root Architecture in Pi Deficiency

Auxin and the associated polar auxin transport mechanism are known to be essential for lateral root formation55,56 and play an important role in modulation of root architecture in response to Pi starvation as described above.

Additional phytohormones are also involved in the regulation of root architecture modulation. In addition to the decrease in cytokinin levels upon Pi starvation,57 the exogenous application of cytokinin reduced the expression of several Pi starvation-responsive genes,58 as well as inhibited lateral root formation,59 suggesting a role for cytokinins in the negative regulation of Pi starvation responses. Cytokinin modulated the level of meristem cell cycle, which influences the expression of Pi starvation-responsive genes.10

Ethylene is also involved in primary root elongation and root hair formation in seedlings grown in Pi-limited medium.60,61 However, analysis of the root architecture of ethylene-signaling mutants and plants treated with the ethylene precursor 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid demonstrated that ethylene did not promote the formation of lateral roots under Pi starvation.18 Ethylene, in combination with jasmonic acid, may be involved in the meristem exhaustion process triggered by Pi starvation.48

Gibberellin plays an important role in regulating plant growth and development.62 The binding of bioactive gibberellin to the receptors GID1 (gibberellin-insensitive dwarf 1) proteins promotes interaction between these gibberellin receptors and DELLAs.63 The DELLAs are subsequently polyubiquitylated by the SCFSLY1/SLY2 E3 ubiquitin ligase and thus degraded by 26S proteasome.64,65 The gibberellin-DELLA growth regulatory system contributes to plant growth responses to Pi starvation.66 Exogenous gibberellin application overcomes several characteristic growth responses to Pi starvation, including the recovery of primary root inhibition and decrease in lateral root density. DELLA-deficient mutants did not exhibit Pi starvation growth responses, whereas the mutations that enhance DELLA function promote Pi starvation responses.66 Pi starvation promoted the accumulation of DELLA in root cell nuclei.66 These results suggest that gibberellin-DELLA-dependent signaling contributes to root architecture modulation in response to Pi starvation but not to Pi uptake and the regulation of Pi starvation-responsive gene expression. Bioactive gibberellin levels were also reduced in low Pi conditions.66

Conclusion and Perspectives

Much progress has been made in research on Pi deficiency-induced root architecture remodeling and several reports suggest that the root tip is a site for locally sensing the status of Pi deficiency. The functional analyses of the different root tissues of the root tip are required to identify the early steps of Pi starvation responses. Several phytohormones, particularly auxin, are involved in the modulation of root architecture adaptation.

The roots of more than 80% of the vascular flowering plants, excluding Arabidopsis, can be colonized by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Symbiosis improves plant mineral, essentially Pi, acquisition. Lateral root branching is stimulated by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi symbiosis.67 Precise mechanisms of root branching and fungi symbiosis may lead to a better understanding and may help to improve crop growth under Pi starvation.

Acknowledgments

Work in the laboratories was supported by grants from, in part, Special Coordination Funds for Promoting Science and Technology and Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B, No. 21770032) from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology.

References

- 1.Raghothama KG. Phosphate acquisition. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1999;50:665–693. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vence CP, Uhde-Stone C, Allan DL. Phosphorus acquisition and use: critical adaptations by plants for securing a nonrenewable resource. New Phytol. 2003;157:423–447. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berndt T, Kumar R. Phosphatonins and the regulation of phosphate homeostasis. Annu Rev Physiol. 2007;69:341–359. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.040705.141729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nielsson L, Müller R, Nielsen TH. Dissecting the plant transcriptome and the regulatory responses to phosphate deprivation. Physiol Plant. 2010;139:129–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2010.01356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cordell D, Drangert JO, White S. The story of phosphorus: global food security and food for thought. Global Environ Change. 2009;19:292–305. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reymond M, Svistoonoff S, Loudet O, Nussaume L, Desnos T. Identification of QTL controlling root growth response to phosphate starvation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Environ. 2006;29:115–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sánchez-Calderón L, López-Bucio J, Chacón-López A, Gutiérrez-Ortega A, Hernαndez-Abreu E, Herrera-Estrella L. Characterization of low phosphorus insensitive mutants reveals a crosstalk between low phosphorus-induced determinate root development and the activation of genes involved in the adaptation of Arabidopsis to phosphorus deficiency. Plant Physiol. 2006;140:879–889. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.073825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jain A, Poling MD, Karthikeyan AS, Blakeslee JJ, Peer WA, Titapiwatanakun B, et al. Differntial effects of sucrose and auxin on localized phosphate deficiency-induced modulation of different traits of root system architecture in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2007;144:232–247. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.092130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Svistoonoff S, Creff A, Reymond M, Sigoillot-Claude C, Ricaud L, Blanchet A, et al. Root tip contact with low-phosphate media reprograms plant root architecture. Nat Genet. 2007;39:792–796. doi: 10.1038/ng2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lai F, Thacker J, Li Y, Doerner P. Cell division activity determines the magnitude of phosphate starvation responses in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2007;50:545–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miura K, Lee J, Gong Q, Ma S, Jin JB, Yoo CY, et al. SIZ1 regulation of phosphate starvation-induced root architecture remodeling involves the control of auxin accumulation. Plant Physiol. 2011;155:1000–1012. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.165191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linkohr BI, Williamson LC, Fitter AH, Leyser HMO. Nitrate and phosphate availability and distribution have different effects on root system architecture of Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2002;29:751–760. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2002.01251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franco-Zorrilla JM, Martin AC, Solano R, Rubio V, Leyva A, Paz-Ares J. Mutations at CRE1 impair cytokinin-induced repression of phosphate starvation responses in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2002;32:353–360. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2002.01431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nacry P, Canivenc G, Muller B, Azmi A, Van Onckelen H, Rossignol M, et al. A role for auxin redistribution in the responses of the root system architecture to phosphate starvation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2005;138:2061–2074. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.060061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.López-Bucio J, Hernández-Abreu E, Sánchez-Calderón L, Pérez-Torres A, Rampey RA, Bartel B, et al. An auxin transport independent pathway is involved in phosphate stress-induced root architectural alterations in Arabidopsis: identification of BIG as a mediator of auxin in pericycle cell activation. Plant Physiol. 2005;137:681–691. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.049577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng Y, Dai X, Zhao Y. Auxin biosynthesis by the YUCCA flavin monooxygenases controls the formation of floral organs and vascular tissues in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1790–1799. doi: 10.1101/gad.1415106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Péret B, De Rybel B, Casimiro I, Benková E, Swarup R, Laplaze L, et al. Arabidopsis lateral root development: an emerging story. Trends Plant Sci. 2009;14:399–408. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.López-Bucio J, Hernández-Abreu E, Sánchez-Calderón L, Nieto-Jacobo MF, Simpson J, Herrera-Estrella L. Phosphate availability alters architecture and causes changes in hormone sensitivity in the Arabidopsis root system. Plant Physiol. 2002;129:244–256. doi: 10.1104/pp.010934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gil P, Dewey E, Friml J, Zhao Y, Snowden KC, Putterill J, et al. BIG: a calossin-like protein required for polar auxin transport in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1985–1997. doi: 10.1101/gad.905201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ticconi CA, Lucero RD, Sakhonwasee S, Adamson AW, Creff A, Nussaume L, et al. ER-resident proteins PDR2 and LPR1 mediate the developmental response of root meristems to phosphate availability. Proc Natl Acd Sci USA. 2009;106:14174–14179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901778106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen DL, Delatorre CA, Bakker A, Abel S. Conditional identification of phosphate-starvation-response mutants in Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta. 2000;211:13–22. doi: 10.1007/s004250000271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ticconi CA, Delatorre CA, Lahner B, Salt DE, Abel S. Arabidopsis pdr2 reveals a phosphate-sensitive checkpoint in root development. Plant J. 2004;37:801–814. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313x.2004.02005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Di Laurenzio L, Wysocka-Diller J, Malamy JE, Pysh L, Helariutta Y, Freshour G, et al. The SCARECROW gene regulates an asymmetric cell division that is essential for generating the radial organization of the Arabidopsis root. Cell. 1996;86:423–433. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80115-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gallagher KL, Benfey PN. Both the conserved GRAS domain and nuclear localization are required for SHORT-ROOT movement. Plant J. 2009;57:785–797. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03735.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang X, Du G, Wang X, Meng Y, Li Y, Wu P, Yi K. The function of LPR1 is controlled by an element in the promoter and is independent of SUMO E3 ligase SIZ1 in response to low Pi stress in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2010;51:380–394. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcq004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miura K, Rus A, Sharkhuu A, Yokoi S, Karthikeyan AS, Raghothama KG, et al. The Arabidopsis SUMO E3 ligase SIZ1 controls phosphate deficiency responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:7760–7765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500778102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miura K, Jin JB, Lee J, Yoo CY, Stirm V, Miura T, et al. SIZ1-mediated sumoylation of ICE1 controls CBF3/DREB1A expression and freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19:1403–1414. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.048397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miura K, Jin JB, Hasegawa PM. Sumoylation, a post-translational regulatory process in plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2007;10:495–502. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miura K, Lee J, Jin JB, Yoo CY, Miura T, Hasegawa PM. Sumoylation of ABI5 by the Arabidopsis SUMO E3 ligase SIZ1 negatively regulates abscisic acid signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:5418–5423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811088106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miura K, Lee J, Miura T, Hasegawa PM. SIZ1 controls cell growth and plant development in Arabidopsis through salicylic acid. Plant Cell Physiol. 2010;51:103–113. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcp171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miura K, Hasegawa PM. Regulation of cold signaling by sumoylation of ICE1. Plant Signal Behav. 2008;3:52–53. doi: 10.4161/psb.3.1.4865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miura K, Hasegawa PM. Sumoylation and abscisic acid signaling. Plant Signal Behav. 2009;4:1176–1178. doi: 10.4161/psb.4.12.10044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miura K, Hasegawa PM. Sumoylation and other ubiquitin-like post-translational modifications in plants. Trends Cell Biol. 2010:223–232. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jin JB, Jin YH, Lee J, Miura K, Yoo CY, Kim WY, et al. The SUMO E3 ligase, AtSIZ1, regulates flowering by controlling a salicylic acid-mediated floral promotion pathway and through affects on FLC chromatin structure. Plant J. 2008;53:530–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03359.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steinmann T, Geldner N, Grebe M, Mangold S, Jackson CL, Paris S, et al. Coordinated polar localization of auxin efflux carrier PIN1 by GNOM ARF GEF. Science. 1999;286:316–318. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5438.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laskowski M, Biller S, Stanley K, Kajstura T, Prusty R. Expression profiling of auxin-treated Arabidopsis roots: toward a molecular analysis of lateral root emergence. Plant Cell Physiol. 2006;47:788–792. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcj043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sampedro J, Cosgrove DJ. The expansin superfamily. Genome Biol. 2005;6:242. doi: 10.1186/gb-2005-6-12-242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lopez-Casado G, Urbanowicz BR, Damasceno CM, Rose JK. Plant glycosyl hydrolases and biofuels: a natural marriage. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2008;11:329–337. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Devaiah BN, Karthikeyan AS, Raghothama KG. WRKY75 transcription factor is modulator of phosphate acquisition and root development in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2007;143:1789–1801. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.093971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Devaiah BN, Nagarajan VK, Raghothama KG. Phosphate homeostasis and root development in Arabidopsis are synchronized by the zinc finger transcription factor ZAT6. Plant Physiol. 2007;145:147–159. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.101691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Devaiah BN, Madhuvanthi R, Karthikeyan AS, Raghothama KG. Phosphate starvation responses and gibberellic acid biosynthesis are regulated by the MYB62 transcription factor in Arabidopsis. Mol Plant. 2009;2:43–58. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssn081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Misson J, Raghothama KG, Jain A, Jouhet J, Block MA, Bligny R, et al. A genome-wide transcriptional analysis using Arabidopsis thaliana Affymetrix gene chips determined plant responses to phosphate deprivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:11934–11939. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505266102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Encinas-Villarejo S, Maldonado AM, Amil-Ruiz F, de los Santos B, Romero F, Pliego-Alfaro F, et al. Evidence for a positive regulatory role of strawberry (Fragaria x ananassa) Fa WRKY1 and Arabidopsis At WRKY75 proteins in resistance. J Exp Bot. 2009;60:3043–3065. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu P, Ma L, Hou X, Wang M, Wu Y, Liu F, et al. Phosphate starvation triggers distinct alterations of genome expression in Arabidopsis roots and leaves. Plant Physiol. 2003;132:1260–1271. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.021022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen ZH, Nimmo GA, Jenkins GI, Nimmo HG. BHLH32 modulates several biochemical and morphological processes that respond to Pi starvation in Arabidopsis. Biochem J. 2007;405:191–198. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Camacho-Cristóbal JJ, Rexach J, Conéjéro G, Al-Ghazi Y, Nacry P, Doumas P. PRD, an Arabidopsis AINTEGUMENTA-like gene, is involved in root architectural changes in response to phosphate starvation. Planta. 2008;228:511–522. doi: 10.1007/s00425-008-0754-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith AP, Jain A, Deal RB, Nagarajan VK, Poling MD, Raghothama KG, et al. Histone H2A.Z regulates the expression of several classes of phosphate starvation response genes but not as a transcriptional activator. Plant Physiol. 2010;152:217–225. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.145532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chacón-López A, Ibarra-Laclette E, Sánchez-Calderón L, Gutiérrez-Alanís D, Herrera-Estrella L. Global expression pattern comparison between low phosphorus insensitive 4 and WT Arabidopsis reveals an important role of reactive oxygen species and jasmonic acid in the root tip response to phosphate starvation. Plant Signal Behav. 2011;6:382–392. doi: 10.4161/psb.6.3.14160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Poirier Y, Thoma S, Somerville C, Schiefelbein J. Mutant of Arabidopsis deficient in xylem loading of phosphate. Plant Physiol. 1991;97:1087–1093. doi: 10.1104/pp.97.3.1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Delhaize E, Randall PJ. Characterization of a phosphate-accumulator mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 1995;107:207–213. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fujii H, Chiou TJ, Lin SI, Aung K, Zhu JK. A miRNA involved in phosphate-starvation response in Arabidopsis. Curr Biol. 2005;15:2038–2043. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aung K, Lin SI, Wu CC, Huang YT, Su CL, Chiou TJ. pho2, a phosphate overaccumulator, is caused by a nonsense mutation in a microRNA399 target gene. Plant Physiol. 2006;141:1000–1011. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.078063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bari R, Datt Pant B, Stitt M, Scheible WR. PHO2, microRNA399 and PHR1 define a phosphate-signaling pathway in plants. Plant Physiol. 2006;141:989–999. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.079707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rubio V, Linhares F, Solano R, Martín AC, Iglesias J, Leyva A, et al. A conserved MYB transcription factor involved in phosphate starvation signaling both in vascular plants and in unicellular algae. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2122–2133. doi: 10.1101/gad.204401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Casimiro I, Marchant A, Bhalerao RP, Beeckman T, Dhooge S, Swarup R, et al. Auxin transport promotes Arabidopsis lateral root initiation. Plant Cell. 2001;13:843–852. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.4.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vanneste S, Friml J. Auxin: a trigger for change in plant development. Cell. 2009;136:1005–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Horgan JM, Wareing PF. Cytokinins and the growth responses of seedlings of Betula pendula Roth. And Acer pseudoplatanus L. to nitrogen and phosphorus deficiency. J Exp Bot. 1980;31:525–532. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martín AC, del Pozo JC, Iglesias J, Rubio V, Solano R, de La Peña A, et al. Influence of cytokinins on the expression of phosphate starvation responsive genes in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2000;24:559–567. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Franco-Zorrilla JM, González E, Bustos R, Linhares F, Leyva A, Paz-Ares J. The transcriptional control of plant responses to phosphate limitation. J Exp Bot. 2004;55:285–293. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erh009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ma Z, Baskin TI, Brown KM, Lynch JP. Regulation of root elongation under phosphorus stress involves changes in ethylene responsiveness. Plant Physiol. 2003;131:1381–1390. doi: 10.1104/pp.012161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.He Z, Ma Z, Brown KM, Lynch JP. Assessment of inequality of root hair density in Arabidopsis thaliana using the Gini coefficient: a close look at the effect of phosphorus and its interaction with ethylene. Ann Bot. 2005;95:287–293. doi: 10.1093/aob/mci024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Richards DE, King KE, Ait-ali T, Harberd NP. How gibberellin regulates plant growth and development: a molecular genetic analysis of gibberellin signaling. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 2001;52:67–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.52.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nakajima M, Shimada A, Takashi Y, Kim YC, Park SH, Ueguchi-Tanaka M, et al. Identification and characterization of Arabidopsis gibberellin receptors. Plant J. 2006;46:880–889. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fu X, Richards DE, Fleck B, Xie D, Burton N, Harberd NP. The Arabidopsis mutant sleepy1gar2-1 protein promotes plant growth by increasing the affinity of the SCFSLY1 E3 ubiquitin ligase for DELLA protein substrates. Plant Cell. 2004;16:1406–1418. doi: 10.1105/tpc.021386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Griffiths J, Murase K, Rieu I, Zentella R, Zhang ZL, Powers SJ, et al. Genetic characterization and functional analysis of the GID1 gibberellin receptors in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2006;18:3399–3414. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.047415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jiang C, Gao X, Liao L, Harberd NP, Fu X. Phosphate starvation root architecture and anthocyanin accumulation responses are modulated by the gibberellin-DELLA signaling pathway in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2007;145:1460–1470. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.103788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Harrison MJ. Signaling in the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2005;59:19–42. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]