Abstract

Mannitol plays a central role in brown algal physiology since it represents an important pathway used to store photoassimilate. Several specific enzymes are directly involved in the synthesis and recycling of mannitol, altogether forming the mannitol cycle. The recent analysis of algal genomes has allowed tracing back the origin of this cycle in brown seaweeds to a horizontal gene transfer from bacteria, and furthermore suggested a subsequent transfer to the green micro-alga Micromonas. Interestingly, genes of the mannitol cycle were not found in any of the currently sequenced diatoms, but were recently discovered in pelagophytes and dictyochophytes. In this study, we quantified the mannitol content in a number of ochrophytes (autotrophic stramenopiles) from different classes, as well as in Micromonas. Our results show that, in accordance with recent observations from EST libraries and genome analyses, this polyol is produced by most ochrophytes, as well as the green alga tested, although it was found at a wide range of concentrations. Thus, the mannitol cycle was probably acquired by a common ancestor of most ochrophytes, possibly after the separation from diatoms, and may play different physiological roles in different classes.

Key words: algae, stramenopiles, mannitol cycle, primary metabolism, osmotic stress, evolution

Brown algae produce mannitol directly from the photoassimilate fructose-6-phosphate. Its metabolism occurs through the mannitol cycle, which involves four enzymatic reactions: (1) the reduction of fructose-6-phosphate (F6P) to mannitol-1-phosphate (M1P) via the activity of an M1P dehydrogenase (M1PDH); (2) the production of mannitol from M1P via an M1P phosphatase (M1Pase); (3) the oxidation of mannitol via the activity of a mannitol-2-dehydrogenase (M2DH) yielding fructose; and (4) the phosphorylation of fructose yielding F6P and involving a hexokinase (HK).1,2 The first completed draft of a brown algal genome enabled the identification of candidate genes for each of these steps.3 As these genes were not found in the genomes of the diatoms Thalassiosira pseudonana and Phaeodactylum tricornutum, mannitol metabolism in stramenopiles was considered a trait typical for brown algae. The corresponding genes were thought to have been acquired horizontally from bacteria and subsequently transferred to some green algae.4 Recently, however, homologs of several genes of the cycle were also found in the genome of the pelagophyte Aureococcus anophagefferens5 and an EST library produced for the dictyochophyte Pseudochattonella farcimen (Dittami et al. personal communication). These observations prompted us to examine the presence of mannitol in a range of strains covering different classes of autotrophic stramenopiles (ochrophytes). In addition, because of the identification of genes encoding enzymes for the production of mannitol through the mannitol cycle in the green alga Micromonas, one strain of this genus was also included in our analysis.

Mannitol is Present in a Wide Range of Ochrophytes

All the examined algal strains (3 replicates each) were grown in 700 ml glass flasks, under a 12:12 h light:dark cycle at a photon flux density of 40 µmol photons m−2 s−1, and at 16−19°C (Table 1). The algal media used were IMR/2,6 ES,7 or K/28 at salinity of 25 psu (Table 1). All cultures were harvested in the exponential growth phase by centrifugation (30 min at 4,000 g) 2 h after the start of the light phase. Pellets were freeze-dried, weighed (1−10 mg), and extracted with boiling water in order to obtain all water soluble material from the algae. Gas chromatography analysis of all samples was carried out after methanolysis and TMS derivatization,9,10 and GC-MS analysis of alditol acetates obtained after hydrolysis, reduction, and acetylation11,12 was used to confirm the identity of the peak with the expected retention time of mannitol.

Table 1.

Strains examined in this study

| Class | Species | Strain | Temp. | Medium |

| Bacillariophyceae | Ditylum brightwellii | UIO227 | 19°C | IMR/2 |

| Dictyochophyceae | Pseudochattonella farcimen | UIO109 | 16°C | ES |

| Dictyochophyceae | Florenciella parvula | UIO235 | 16°C | ES |

| Eustigmatophyceae | Nannochloropsis salina | SAG40.85 | 19°C | ES |

| Raphidophyceae | Heterosigma akashiwo | UIO202 | 19°C | ES |

| Schizocladiophyceae | Schizocladia ischiensis | CCMP2287 | 19°C | ES |

| Prasinophyceae | Micromonas pusilla | UIO4 | 16°C | ES |

| Chrysophycaeae | Ochromonas minima | UIO97 | 19°C | K/2 |

UIO, University of Oslo Culture Collection of Algae; SAG, Sammulung von Algenkulturen, Göttingen; CCM P, Provasoli-Guillard National Center of CCM, Provasoli-Guillard National Center of Culture of Marine Phytoplankton.

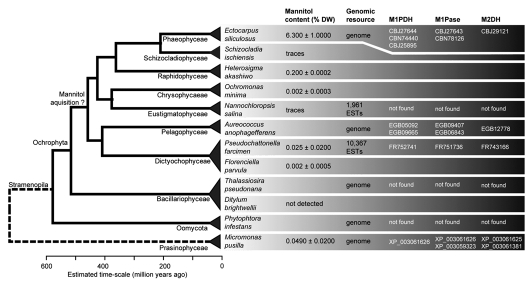

Our results are presented in Figure 1, in the context of a recent molecular phylogeny of stramenopiles,13 and complemented by genomic analyses. No mannitol was detected in the diatom strain tested, and levels in Schizocladia and Nannochloropsis were too low for reliable quantification, although traces <0.001% dry weight (DW) were present. In addition, for Nannochloropsis, no genes encoding enzymes of the mannitol cycle were found in the limited available EST resources.14 All other strains contained various quantifiable amounts of mannitol. Furthermore, although no pelagophytes were tested for mannitol content, the analysis of the Aureococcus anophagefferens genome5 revealed the presence of at least one M1PDH, and we also detected genes likely to code for M1Pases and M2DH. Interestingly, the two best candidates M1Pases are not related to those found in the other examined stramenopiles and Micromonas (e-values >1), but rather close to an M1Pase characterized in the mannitol-producing apicomplexan parasite Eimeria tenella15 (e-values ≤2e-41 and sequence identity ≥40%). Additional DNA sequences exhibiting low similarity with putative Ectocarpus M1Pases have also been identified in the Aureococcus genome, but are not mentioned in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Mannitol content and genes of the mannitol cycle in selected stramenopiles and Micromonas, in the context of a dated molecular phylogeny.13 The mannitol content is given as a mean ± SD in % dry weight. Values for E. siliculosus were taken from Gravot et al.21 All three genes were also absent from the genomes of the diatoms Phaeodactylum and Fragilariopsis, as well as of the other oomycetes Phytophtora ramorum and Phytophtora sojae. Genes identified in Micromonas pusilla CCMP1545 were also found in the genome of Micromonas sp. RCC299. Genomic resources or mannitol measurements were not available for all listed species. Hexokinases were not included in this figure as they are present in most organisms and their specificity is difficult to infer merely from sequence information.

From an evolutionary point of view, our findings suggest that genes involved in mannitol metabolism in ochrophytes may have been acquired from bacteria far earlier than initially suspected by Michel et al.4 Given the wide distribution of this compound and related genes, the most plausible explanation would be for such a horizontal gene transfer to have taken place in a ancestral ochrophyte, most likely during the Paleozoic era, and after the separation of diatoms from most other ochrophytes as early as 390–710 million years ago. However, the possible independent origin of two putative M1Pases in Aureococcus also indicates that the situation is potentially more complex, and that additional gene exchanges or losses may have taken place.

The Role of Mannitol in Marine Microalgae

An interesting observation is the wide range of mannitol concentrations measured in the different species. While in some, mannitol was hardly detectable (<0.001% DW), others accumulated substantial amounts of this compound. Although these findings may be biased by differences in growth conditions, all species were incubated at conditions resulting in good growth for each strain. Among the unicellular organisms tested, we observed highest mannitol levels in the raphidophyte Heterosigma akashiwo. This harmful bloom-forming species is known for its tolerance to a wide range of salinities,16 while mannitol has been described as a compatible osmolyte17 or probable osmoprotectant18 in Ectocarpus. High basal levels of mannitol may enhance the ability to adapt to osmotic changes, thus possibly providing an explanation why Heterosigma dominates blooms particularly in times when (nutrient-rich) freshwater runoff is high and salinities are variable and low.19,20

Another interesting comparison can be drawn with the multicellular brown alga Ectocarpus, where mannitol is involved in short-term carbon storage, and levels under standard conditions are as high as 6% DW. In contrast, the closely related multicellular alga Schizocladia ischiensis contains levels <0.001% DW. This clearly demonstrates that basal mannitol levels are not a function of phylogenetic position, and suggests that this compound might have evolved to serve different purposes in different algae, and/or its metabolism may be regulated by different factors. Additional experiments are required to further explore these aspects.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Charles G. Trick for helpful comments on the physiology of Heterosigma.

References

- 1.Iwamoto K, Shiraiwa Y. Salt-regulated mannitol metabolism in algae. Mar Biotechnol. 2005;7:407–415. doi: 10.1007/s10126-005-0029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rousvoal S, Groisillier A, Dittami SM, Michel G, Boyen C, Tonon T. Mannitol-1-phosphate dehydrogenase activity in Ectocarpus siliculosus, a key role for mannitol synthesis in brown algae. Planta. 2011;233:261–273. doi: 10.1007/s00425-010-1295-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cock JM, Sterck L, Rouzé P, Scornet D, Allen AE, Amoutzias G, et al. The Ectocarpus genome and the independent evolution of multicellularity in brown algae. Nature. 2010;465:617–621. doi: 10.1038/nature09016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Michel G, Tonon T, Scornet D, Cock JM, Kloareg B. Central and storage carbon metabolism of the brown alga Ectocarpus siliculosus: insights into the origin and evolution of storage carbohydrates in Eukaryotes. New Phytol. 2010;188:67–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gobler CJ, Berry DL, Dyhrman ST, Wilhelm SW, Salamov A, Lobanov AV, et al. Niche of harmful alga Aureococcus anophagefferens revealed through ecogenomics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:4352–4357. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016106108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eppley RW, Holmes RW, Strickland JDH. Sinking rates of marine phytoplankton measured with a fluorometer. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 1967;1:191–208. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Throndsen J. Flagellates of Norwegian coastal waters. Nytt Mag Bot. 1969;16:161–216. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keller MD, Guillard RRL. Factors significant to marine dinoflagellate culture. In: Anderson DM, White AW, Baden DG, editors. Toxic Dinoflagellates; Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Toxic Dinoflagellates; New York: Elsevier; 1985. pp. 113–116. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chambers RE, Clamp JR. An assessment of methanolysis and other factors used in the analysis of carbohydrate-containing materials. J Biochem. 1971;125:1009–1018. doi: 10.1042/bj1251009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barsett H, Paulsen BS, Habte Y. Further characterization of polysaccharides in seeds from Ulmus glabra Huds. Carbohydr Polym. 1992;18:125–130. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim JB, Carpita NC. Changes in esterification of the uronic acid groups of cell wall polysaccharides during elongation of maize coleoptiles. Plant Physiol. 1992;98:646–653. doi: 10.1104/pp.98.2.646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inngjerdingen KT, Debes SC, Inngjerdingen M, Hokputsa S, Harding SE, Rolstad B, et al. Bioactive pectic polysaccharides from Glinus oppositifolius (L.) Aug DC, a Malian medicinal plant, isolation and partial characterization. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;101:204–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown JW, Sorhannus U. A molecular genetic timescale for the diversification of autotrophic stramenopiles (Ochrophyta): substantive underestimation of putative fossil ages. PloS One. 2010;5:12759. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi J, Pan K, Yu J, Zhu1 B, Yang G, Yu W, et al. Analysis of expressed sequence tags from the marine microalga Nannochloropsis oculata (Eustigmatophyceae) J Phycol. 2008;44:99–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2007.00444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liberator P, Anderson J, Feiglin M, Sardana M, Griffin P, Schmatz D, et al. Molecular cloning and functional expression of mannitol-1-phosphatase from the apicomplexan parasite Eimeria tenella. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:4237–4244. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.7.4237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hosaka M. Growth characteristics of a strain of Heterosigma akashiwo (Hada) Hada isolated from Tokyo bay, Japan. Bull Plankton Soc Jpn. 1992;39:49–58. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davison IR, Reed RH. The physiological significance of mannitol accumulation in brown algae: the role of mannitol as a compatible solute. Phycologia. 1985;24:449–457. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dittami SM, Gravot A, Renault D, Goulitquer S, Eggert A, Bouchereau A, et al. Integrative analysis of metabolite and transcript abundance during the short-term response to saline and oxidative stress in the brown alga Ectocarpus siliculosus. Plant Cell Environ. 2011;34:629–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2010.02268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor FJR, Haigh R. The ecology of fish-killing blooms of the chloromonad flagellate Heterosigma in the Strait of Georgia and adjacent waters. In: Smayda TJ, Shimizu Y, editors. Toxic Phytoplankton Blooms in the Sea. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1993. pp. 705–710. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horner RA, Garrison DL, Plumley FG. Harmful Algal Blooms and Red Tide Problems on the US West Coast. Limnol Oceanogr. 1997;42:1076–1088. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gravot A, Dittami SM, Rousvoal S, Lugan R, Eggert A, Collén J, et al. Diurnal oscillations of metabolite abundances and gene analysis provide new insights into central metabolic processes of the brown alga Ectocarpus siliculosus. New Phytol. 2010;188:98–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]