Abstract

Tumor hypoxia is a known adverse prognostic factor, and the hypoxic dermal microenvironment participates in melanomagenesis. High levels of hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) expression in melanoma cells, particularly HIF-2α, is associated with poor prognosis. The mechanism underlying the effect of hypoxia on melanoma progression, however, is not fully understood. We report evidence that the effects of hypoxia on melanoma cells are mediated through activation of Snail1. Hypoxia increased melanoma cell migration and drug resistance, and these changes were accompanied by increased Snail1 and decreased E-cadherin expression. Snail1 expression was regulated by HIF-2α in melanoma. Snail1 overexpression led to more aggressive tumor phenotypes and features associated with stem-like melanoma cells in vitro and increased metastatic capacity in vivo. In addition, we found that knockdown of endogenous Snail1 reduced melanoma proliferation and migratory capacity. Snail1 knockdown also prevented melanoma metastasis in vivo. In summary, hypoxia up-regulates Snail1 expression and leads to increased metastatic capacity and drug resistance in melanoma cells. Our findings support that the effects of hypoxia on melanoma are mediated through Snail1 gene activation and suggest that Snail1 is a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of melanoma.

The incidence of melanoma is increasing significantly faster than that of any other cancer in the United States.1, 2, 3 Malignant melanoma is known for its aggressive clinical behavior, propensity for lethal metastasis, and therapeutic resistance. Hypoxia promotes tumor progression and resistance to chemotherapy and radiation.4, 5, 6, 7 A number of studies have shown a link between tumor metastasis and lactate concentration in cancers,4, 5, 6, 8, 9 including melanoma.10, 11 High levels of lactate are indicative of extensive anaerobic metabolism and poor oxygenation in tumor tissues.12 Tumor hypoxia typically occurs very early in tumor development, the result of poor vascular formation in tumors.8 Patients with hypoxic tumors have a poorer prognosis than patients with well-oxygenated counterparts.13

The hypoxic dermal microenvironment is a host factor that promotes melanomagenesis.10 The effects of hypoxia are mediated through hypoxia inducible factors (HIFs). HIF-1α and HIF-2α are transcription factors that have common transcriptional targets, including genes involved in angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis. However, they also regulate distinct subsets of genes during hypoxia. For example, HIF-1α activates genes involved in glycolysis and apoptosis,14, 15, 16, 17 whereas HIF-2α induces a different subset of genes, including the stem cell factor OCT418 and ABCG2.19 In melanoma patients, high levels of HIF expression, particularly HIF-2α, are associated with poorer prognosis.20 Nevertheless, the underlying mechanism by which HIF-2α promotes melanoma metastasis and drug resistance is not fully understood.

The initial steps in tumor metastasis involve a decrease in E-cadherin levels and a corresponding increase in N-cadherin levels.21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26 The switch from E-cadherin to N-cadherin expression converts cells with a nonmotile phenotype to migratory cells that are more prone to invade other tissues.27 Several reports have shown an inverse correlation between E-cadherin and Snail1 expression in a number of cancers, including melanoma.28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34 Snail1 expression is regulated by a number of molecules involved in tumor progression, such as ERK, Akt, and NF-κB,35 and the Snail1 promoter contains two potential hypoxia response elements (HREs). However, HIF interaction with Snail1 appears to be species specific36 and may depend on other co-factors, such as Notch.37 In this report we demonstrate that hypoxia promotes melanoma metastasis and drug resistance through Snail1 activation via HIF-2α. In addition, Snail1 activation in melanoma also leads to melanoma cells acquiring cancer stem cell-like features.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines, Reagents, and Plasmids

Cisplatin was purchased from Ben Venue Laboratories (Bedford, OH); temozolomide from TOCRIS Biosciences (Bristol, UK); monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) or BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). pWZL-Blast-Snail-ER plasmids (plasmid 18798) were obtained from Addgene Inc (Cambridge, MA); pGIPZ-Snail1 was purchased from Thermo Scientific; tamoxifen was purchased from Sigma (Selma, CA). Human melanoma cell lines (WM35, WM793, WM115A, WM3523A, and 1205Lu) were kind gifts from Meenhard Herlyn (The Wistar Institute, Philadelphia, PA), pCDNA3-HIF-1α was kindly provided by Frank Lee (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA), and pGFP-HIF2α plasmid was a kind gift from Volker Haase (Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN). Si-snail1 was purchased from Qiagen (Valencia, CA). Si-HIF1α and Si-HIF2α were purchased from BD Biosciences.

Cell Culture

Human melanoma cell lines were maintained in 2% MCDB medium.11 Mouse embryonic fibroblast cells were cultured in DMEM with high glucose and L-Glutamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 10% mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF)-specific fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Invitrogen), 1% nonessential amino acids, and L-glutamine (200 mmol/L/L) (Invitrogen). 293T cells were maintained in high glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% FBS, penicillin/streptomycin (100 units/mL and 100 mg/mL) (Invitrogen). Phoenix-Ampho cells were cultured in high glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% FBS, 4 mmol/L L-glutamine, and penicillin/streptomycin.

Virus Production and Infection

Lentiviral vectors containing short hairpin RNA (shRNA) of Snail1 in pGIPZ vector or non-silencing control shRNA in pGIPZ (Thermo Scientific, Huntsville, AL) was co-transfected into 293T cells with packing vector (pCMV-dR8.2-dupr and pCMV-VSV). Viral supernatants were collected 48 and 72 hours post-transfection, and were used to infect melanoma cells as previously described.38 After a 48-hour period, cells were cultured in puromycin (1 μg/mL) selection medium. The pWZL-Blast-Snail-ER plasmids were co-transfected into Phoenix Ampho packaging cells, and viral supernatants were collected 48 and 72 hours post-transfection to infect melanoma cells. After a 48-hour period, cells were cultured in blasticidin (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA) (5 μg/mL) selection medium for 5 days. Infected melanoma cells were then cultured in MCDB media with 2% FBS and 20 nmol/L tamoxifen.

Transfection

Si-Snail1, Si-HIF1α, and Si-HIF2α and the irrelevant Si-control (negative control) were used as instructed by the manufacturer. Briefly, on the day of transfection, 5 × 104 melanoma cells were plated per well in 2 mL 2% FBS MCDB tumor media. Cells were then incubated with siPORT NeoFX Transfectin Agent (Ambion Inc., Austin, TX) (10 μL in 200 μL OPTI-MEM I medium (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA) without serum) for 5 minutes. Then 10 μmol/L Si-Snail1, Si-HIF1α, or Si-HIF2α were added and cells were incubated for 10 minutes at room temperature to allow the formation transfection complexes. The next day, the medium was replaced with 2% MCDB tumor medium, and after 48 hours, cells were harvested and analyzed.

Hypoxia Treatment

The 1 × 104 melanoma cells with pWZL-Blast-Snail-ER (inducible Snail1), pGIPZ-Snail1 (Sh-Snail1), or control vectors were seeded in triplicate in 24 well plates and incubated at 37°C in a regular CO2 incubator for 24 hours. The next day, the media was replaced with 2% MCDB media and the cells were incubated in with 1% O2 conditions at 37°C for 8, 16, and 24 hours. At the end of this period, we counted the viable cells in each well by trypan blue exclusion assays. For cell migration assay, pWZL-Blast-Snail-ER, pGIPZ-Snail1, or control vector infected melanoma cells were grown to confluence and wounded by dragging a 1-mL pipette tip through the monolayer. Cells were washed to remove cellular debris and were allowed to migrate for 20 hours. Images were taken after wounding at various time points under a DMI6000 inverted microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany).

Drug Resistance Studies

Melanoma cells with pWZL-Blast-Snail-ER, pGIPZ-Snail1 or control vectors, as well as hypoxia-treated melanoma cells were washed with PBS and 1 × 105 cells were plated in 6 well plates. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 hours and cultured with serum free MCDB medium for another 24 hours in a humidified CO2 incubator. The culture medium was aspirated and 2% tumor media containing different concentrations of cisplatin or temozolomide (1–100 μmol/L) was added to each well. Drug treated and control cells were incubated another 24 hours at 37°C in a humidified CO2 incubator. After 24 hours, the cells were washed with 2% tumor media and allowed to grow another 24 hours before counting viable cells. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Isolation of RNA and Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was isolated using RNeasy Kit (Qiagen) followed by cDNA synthesis using SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen). Quantitative PCR was performed using iQ SYBR green supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) with specific primers listed as follows. cDNA corresponding to 1 μg RNA was added to the iQsyber green supermix and analyzed with icycler (Bio-rad Laboratories), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The thermal profiles were 95°C for 30s and 56°C for 30s. Melting curve analysis was done for each PCR reaction to confirm the specificity of amplification. At the end of each phase, florescence was measured and used for quantitative purpose. Primer sequences are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers Used for Real-Time PCR

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| E-Cadherin (CDH1) | 5′-TTCCCTGCGTATACCCTGGT-3′ | 5′-GCGAAGATACCGGGGGACACTCATGAG-3′ |

| N-Cadherin (CDH2) | 5′-CACTGCTCAGGACCCAGAT-3′ | 5′-TAAGCCGAGTGATGGTCC-3′ |

| Sox10 | 5′-CTTCGGCAACGTGGACATT-3′ | 5′-TCAGCCACATCAAAGGTCTCC-3′ |

| α-SMA (ACTA2) | 5′-ACTGGGACGACATGGAAAAG-3′ | 5′-TAGATGGGGACATTGTGGGT-3′ |

| Snail1 | 5′-GACTAGAGTCTGAGATGCCC-3′ | 5′-CAGACATTGTTAAATTGGCCG-3′ |

| HIF1α | 5′-CATAAAGTCTGCAACATGGAAGGT-3′ | 5′-ATTTGATGGGTGAGGAATGGGTT-3′ |

| HIF2α | 5′-CACTGCTTCAGTGCCATGACA-3′ | 5′-TGTCCAGGAGGAAGGGACTGT-3′ |

| Twist | 5′-TGTCCGCGTCCCACTAGC-3′ | 5′-TGTCCATTTTCTCCTTCTCTGGA-3′ |

| JARID1B | 5′-CGATAAACTTCATTTCACCCCG-3′ | 5′-ACCCACCTTCTTCTGCGACTAAC-3′ |

| p75NGFR | 5′-TTCAAGGGCTTACACGTGGAGGAA-3′ | 5′-TGTGTGTAAGTTTCAGGAGGGCCA-3′ |

| β-Actin (ACTB) | 5′-TGACTGACTACCTCATGAAGATCC-3′ | 5′-GCCATCTCTTGCTCGAAGTCC-3′ |

HIF, hypoxia inducible factor; SMA, smooth muscle actin.

Immunocytochemistry

Normoxia- or hypoxia-treated melanoma cells, or melanoma cells with pWZL-Blast-Snail-ER or pGIPZ-Snail1 vectors were seeded on fibronectin pretreated chamber slides. Cells were fixed with glutaraldehyde for 20 minutes at room temperature and then washed three times with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 5 minutes. Cells were then permeabilized and blocked by 0.3% Triton X-100, 1% BSA, and 10% normal donkey serum in PBS at room temperature for 45 minutes. The cells were then stained with Snail1, E-cadherin, and N-cadherin primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Stained cells were then washed three times with PBS containing 1% BSA and incubated with the appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Dana Point, CA). Cells were imaged with a Leica Inverted fluorescence microscope with a Leica camera. The images were processed and analyzed using Adobe Photoshop software. We performed Western blot as previously described.39

Cell Proliferation Assay

Melanoma cells were seeded in 24-well plates at densities of 5 × 104 cells per well, grown for 24 hours, treated with 1% O2 for 16 hours, normoxia cells were used as the control, and then WST-1 cell proliferation assay (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) was used to quantify proliferative cells. The absorbance at 450 nm was measured using an lQuant Universal Microplate Spectrophotometer (Bio-tek Instruments, Winooski, VT).

Cell Cycle Analysis

1 × 106 melanoma cells with Snail1 knockdown or control cells were harvested, rinsed twice with PBS, and fixed with 70% ethanol overnight at 4°C. Fixed cells were then washed 2 times with PBS and stained with 20 μg/mL propidium iodide (PI). Analysis was performed on a FACS Calibur using CellQuest Pro software. Cell cycle analysis was performed using ModFit software (Verity Software House, Topsham, ME).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assay

The chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay was conducted by using a Chip assay kit, according to the manufacturer's instruction (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA), and rabbit antibody against human HIF-1α and HIF-2α protein (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). The immunoprecipitated chromatin was analyzed in triplicate by PCR using the primers (5′-ATCCCTGGAAGCTGCTCTCT-3′ forward and 5′-TCTGGTCCAGTGAGGGAG-3′) for human Snail1 promoter.37

Limiting Dilution Assay

Melanoma cells over-expressing Snail1 or control cells were trypsinized, washed, and re-suspended at a concentration of 100 cells/mL in HECM4 media.40 10 μL of the cell suspension was dispensed into wells of 96-well plates, containing 90 μL of 2% MCDB media. All plates were examined to ensure that that one cell was delivered to each well. The cells were incubated for another 7 days, with media changes every other day. Colonies were counted in single cell seeded wells.

Soft Agar Colony Formation Assay

The 1 × 104 control or tamoxifen-induced Snail1 infected WM115A cells were re-suspended in 3 mL of 1.8% (w/v) Bacto-Agar solution containing MCDB with 20% FBS. The mixtures were overlaid onto a 3.3% (w/v) BactoAgar solution in 6-well plates. On the following day, 0.5 mL of MCDB supplemented with 2.0% FBS was added. Colonies were counted under a microscope after 15 days. Colony forming efficiency was calculated by the number of colonies times 100, divided by the number of cells plated.

Sphere Formation Assay

Melanoma cells with over-expressing Snail1 or control vectors were washed with PBS, trypsinized, and then re-washed with PBS, and re-suspended in HECM4 media. The 5 × 104 cells were aliquoted into an ultra-low attachment 6-well plate containing 2 mL of HECM4 media. The cells were incubated for another 7 days, and 0.5 mL of new media was added every other day. The number of colonies formed was counted using an inverted microscope.

Xenograft Tumor Model

Four- to five-week-old male athymic nu/nu mice were used in this study. The control, pWZL-Blast-Snail1-ER, or pGIPZ-Snail1-infected WM115A cells (2 × 106 cells/animal) were injected subcutaneously into nude mice (10 mice per group). The mice that received pWZL-Blast-Snail1-ER cells continued to receive tamoxifen to maintain Snail1 expression. After 35 days, we sacrificed the mice and performed necropsy for further analysis.

Statistical Analysis

The data represent mean ± SEM values. The effect of treatments and differences among experimental groups were assessed using analysis of variance and the appropriate post hoc test. The differences between the two experimental groups were determined using the Student's t-test. A two-tailed value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All of the analyses were performed using the GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA).

Results

Hypoxia Induces Phenotypic Changes in Vitro

We first studied the effects of hypoxia on melanoma cells in vitro. WM115A, 1205Lu and 451Lu cells were incubated under hypoxic (1% O2) or normoxic conditions for 8, 16, or 24 hours. Hypoxia significantly inhibited tumor cell proliferation, and only 50% of the WM115A cells survived after 16 or 24 hours of treatment (Figure 1A). We chose 16-hour hypoxic treatment for further studies because there was no significant difference between the cells treated for 16 or 24 hours. To examine drug resistance in hypoxia-treated melanoma cells, we treated the cells that survived hypoxia treatment with various doses of cisplatin and temozolomide. In the absence of hypoxia treatment, cisplatin and temozolomide-induced cell death in a dose-dependent manner, killing most of the melanoma cells at 25 μmol/L cisplatin (Figure 1B). However, tumor cells survived hypoxia treatment showed dramatically increased resistance to cisplatin and temozolomide, with 29.8 ± 3% or 44 ± 5.0% of the cells still alive after exposure to 25 μmol/L cisplatin or temozolomide (Figure 1B). Cell motility (measured by the wound healing assay) was significantly increased after hypoxic treatment (Figure 1C). When hypoxia-treated cells were used in soft agar assays, the resultant colonies were significantly larger and more abundant when compared to control cells (Figure 1D), which suggests that the tumor cells that survived hypoxia treatment had high migratory and proliferation capacity. The results from 1205Lu and 451Lu cells were similar to WM115A cells (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Hypoxia enhances melanoma drug resistance and migration. A: Effect of hypoxia on melanoma cells. WM115A cells were incubated under 1.0% or 21% O2 for 8, 16, 24 hours (n = 3 replicate experiments, *P < 0.05 compared with control). B: Effect of cisplatin and temozolomide on melanoma cells. Normoxia and hypoxia-treated WM115A cells were incubated with 1, 10, or 25 μmol/L of cisplatin and temozolomide (n = 3 replicate experiments; *P < 0.05 compared with control). C: Cell migration assay. Wound healing of normoxia- or hypoxia-treated WM115A cells at 0 and 20 hours after scratch formation. Shown are representative images from three experiments. D: Soft agar assay. Normoxia- or hypoxia-treated WM115A were incubated in soft agar. The clones were counted using a microscope at 100× power. The values (colony number) are expressed as mean ± SD (SD) from three separate measurements (*P < 0.05 compared with normoxia-treated cells).

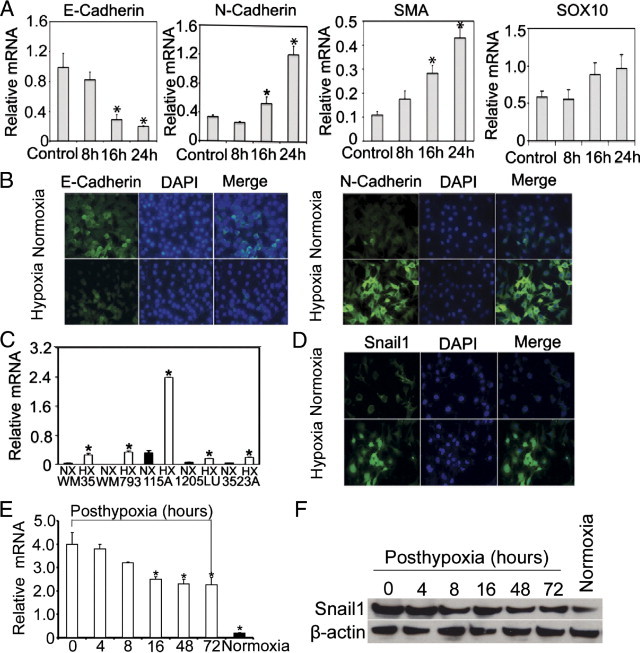

Hypoxia Induces the Decreased Expression of E-Cadherin

We cultured WM115A cells under hypoxic or normoxic conditions for 8, 16, or 24 hours and measured gene expression in these cells. E-cadherin levels were significantly decreased under hypoxia, which was accompanied by increased expression of N-cadherin and smooth muscle actin levels. In contrast, Sox10 levels did not significantly change. Similarly, E-cadherin protein levels were reduced after hypoxia treatment, whereas the N-cadherin expression levels were significantly increased (Figure 2B). Snail1 gene expression levels were significantly elevated in all five melanoma cell lines (WM35, WM793, WM115A, 1205Lu, and WM3523A) examined after hypoxic treatment (Figure 2C), and similar change was seen in Snail1 protein expression level (Figure 2D). To examine whether exposure to hypoxia has lasting effect on Snail1 expression, we exposed WM115A cells to 8 hours of hypoxia and then incubated the cells under normoxia. We found that Snail1 gene and protein expression were still elevated 72 hours post-hypoxic treatment (Figure 2, E and F).

Figure 2.

Hypoxia induces Snail1 up-regulation and E-cadherin down-regulation. A: Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of E-cadherin, N-cadherin, smooth muscle actin (SMA), and SOX10 expression after hypoxia treatment. WM115A cells were cultured under 1.0% or 21% O2 for 8, 16, 24 hours (n = 3 replicate experiments; *P < 0.05 compared with control). B: Expression of E-cadherin or N-cadherin after hypoxia treatment. Immunocytochemical stain of E-cadherin and N-cadherin in WM115A after hypoxia treatment. C: Snail1 gene expression after hypoxia treatment. Snail1 expression in WM35, WM793, WM115A, 1205LU, and WM3523A was assessed by quantitative RT-PCR (n = 3 replicate experiments; *P < 0.01 compared with control). D: Expression of Snail1 by immunocytochemistry (n = 3 replicate experiments). E: Snail1 gene expression in WM115A cells (post-hypoxia 0, 4, 8, 16, 48, and 72 hours) was assessed by quantitative RT-PCR (n = 3 replicate experiments; *P < 0.01 compared with control). F: Expression of Snail1 by Western blot. Cell lysates from WM115A (post-hypoxia 0, 4, 8, 16, 48, and 72 hours) were used for Western blot analyses with anti-Snail1 antibody. β-actin was used as loading controls.

HIF-2α Regulates Snail1 Expression

To examine how HIFs regulate Snail1 expression, we transfected WM115A cells with vectors containing HIF1α or HIF2α. Overexpression of HIF-1α (Figure 3A, left panel) or HIF2α (Figure 3A, right panel) in these cells was confirmed by quantitative RT-PCR. Up-regulation of Snail1 gene expression was seen in melanoma cells transfected with HIF2α, but not HIF1α (Figure 3B). These findings were confirmed by Western blot analysis (Figure 3C). To further study the interaction, we transfected the melanoma cells with siRNAs to HIF1α or HIF2α. Down-regulation of HIF1α (Figure 3D, left panel) or HIF2α (Figure 3D, right panel) in these cells was confirmed by quantitative RT-PCR. Down-regulation of Snail1 gene expression was seen in melanoma cells transfected with HIF2α, but not HIF1α (Figure 3E). These findings were also confirmed by Western blot analysis (Figure 3F). Next, we tested whether the HIF proteins were bound directly to the Snail1 promoter using a ChIP assay. However, we did not observe evidence of direct binding of HIF-1α or HIF-2α to the Snail1 promoter in melanoma cells (data not shown).

Figure 3.

HIF-2α up-regulates Snail1. A: Quantitative RT-PCR assay for HIF-1α and HIF-2α expression in WM115A cells transfected with plasmids containing HIF-1α or HIF-2α (n = 3 replicate experiments; *P < 0.01 compared with control). B: Quantitative RT-PCR assay for Snail1 expression in WM115A cells transfected with plasmids containing HIF-1α or HIF-2α (n = 3 replicate experiments; *P < 0.01 compared with control). C: Western blot analysis for Snail1 expression in WM115A cells transfected with plasmids containing HIF-1α or HIF-2α (n = 3 replicate experiments). D: Quantitative RT-PCR assay for HIF-1α and HIF-2α expression in WM115A cells transfected with plasmids containing Si-HIF-1α or Si-HIF-2α (n = 3 replicate experiments; *P < 0.01 compared with control). E: Quantitative RT-PCR assay for Snail1 expression in WM115A cells transfected with plasmids containing Si-HIF-1α or Si-HIF-2α (n = 3 replicate experiments; *P < 0.01 compared with control). F: Western blot analysis for Snail1 expression in WM115A cells transfected with plasmids containing Si-HIF-1α or Si-HIF-2α (n = 3 replicate experiments).

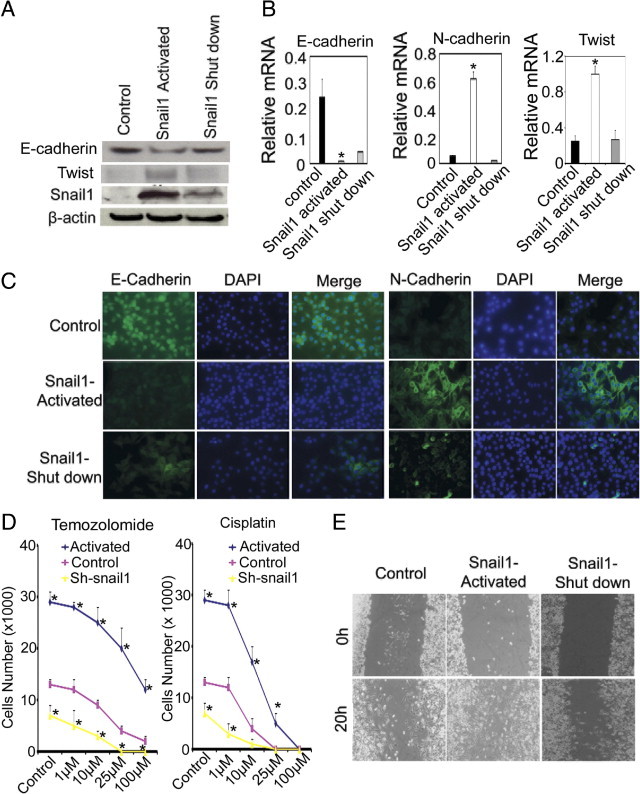

Effects of Snail1 Activation

To study the function of Snail1 in melanoma cells, we infected WM115A, WM35, WM3523A, and 1205Lu cells with an inducible Snail1 retroviral vector, pWZL-Blast-ER-Snail1.41 In this system, Snail1 overexpression can be controlled by adding or removing tamoxifen to the culture medium. We found that when tamoxifen was added to the culture medium, there was a significant increase of Snail1 protein expression (Figure 4A; see also Supplemental Figure S1A at http://ajp.amjpathol.org), and the effect can last up to 6 days (see Supplemental Figure S2B at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Activation of Snail was accompanied by increased N-cadherin expression (Figure 4B) and a corresponding decrease in E-cadherin expression gene and protein expression (Figure 4, A and B; see also Supplemental Figure S1A at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Because Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)-associated E-box factors can act in a coordinated manner42 and Twist1 expression is associated with a poor prognosis in melanoma,43 we test whether Snail1 may regulate Twist. Indeed, Twist expression was correlated with Snail1 expression (Figure 4, A and B). When we removed tamoxifen from the medium, there was a decrease in Snail1 expression (Figure 4A), which was accompanied by elevated levels of E-cadherin (Figure 4, A and B), decreased levels of N-cadherin (Figure 4B), and Twist (Figure 4, A and B). The effect of Snail1 expression on E-cadherin and N-cadherin was further confirmed by immunocytochemistry (Figure 4C). To study Snail1 expression and drug resistance, we infected melanoma cells with pWZL-Blast-ER-Snail1 or pGIPZ-shRNA-Snail1, and these cells were incubated with various concentrations of temozolamide and cisplatin (0, 1, 10, 25, or 100 μmol/L) for 24 hours in the absence or presence of tamoxifen. Snail1 activation resulted in a significant increase of cell proliferation (Figure 4D; see also Supplemental Figure S1B at http://ajp.amjpathol.org) and these cells maintained higher proliferation rate than control cells in the presence of various doses of temozolamide and cisplatin (Figure 4D). On the contrary, Snail1 knockdown resulted in significantly reduced cell proliferation (Figure 4D; see also Supplemental Figure S1B at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Snail activation also resulted in increased cell motility (Figure 4E; see also Supplemental Figure S2A at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). These data suggest that Snail1 activation induces phenotypic changes similar to those seen in melanoma cells that have survived hypoxia treatment.

Figure 4.

Effects of Snail1 activation. A: Snail1, E-cadherin, and Twist expression in WM115A cells (n = 3 replicate experiments). Tumor cells were infected with pWZL-Blast-ER-Snail1 and incubated in the medium with absence, presence, or after withdraw of tamoxifen (shutdown of exogenous Snail1 expression). B: Quantitative RT-PCR for E-cadherin, N-cadherin, and Twist expression in WM115A cells with pWZL-Blast-ER-Snail1 (n = 3 replicate experiments; *P < 0.01 compared with control). C: Immunocytochemical stain for E-cadherin and N-cadherin in WM115A cells with pWZL-Blast-ER-Snail1. D: Resistance to temozolamide and cisplatin. The same number of WM115 cells control and WM115 cells with pWZL-Blast-ER-Snail1 or pGIPZ-Snail1 were incubated in medium containing 0, 1, 10, 25, or 100 μmol/L temozolamide or cisplatin for 24 hours (n = 3 replicate experiments; *P < 0.01 compared with control). E: Cell migration assay. Wound healing assay using WM115A with pWZL-Blast-ER-Snail1 at 0 and 20 hours after scratch forming (n = 3 replicate experiments).

Effects of Knockdown-Mediated Reduced Snail1 Expression

To further study the effect of Snail1 in melanoma, we knocked down endogenous Snail1 expression using SiRNA and lentiviral vectors containing shRNA to Snail1 in WM115A, WM35, WM3525A, and 1205Lu cells. Snail1 knockdown was confirmed by quantitative PCR (Figure 5A) and Western blot (Figure 5C; see also Supplemental Figure S1A at http://ajp.amjpathol.org) and these cells showed increased E-cadherin levels and decreased N-cadherin expression levels by immunocytochemistry and Western blot analysis (Figure 5, B and C; see also Supplemental Figure S1A at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). The tumor cells in the G2/S phase were decreased after Snail1 knockdown cells (Figure 5D). Snail1 knockdown cells showed a significant decrease of cell survival following hypoxia treatment (Figure 5E; see also Supplemental Figure S1C at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). The migratory activity of melanoma cells as measured by wound healing time in both normoxic and hypoxic condition was also significantly decreased after Snail1 knockdown (Figure 5F; see also Supplemental Figure S2A at http://ajp.amjpathol.org).

Figure 5.

Effects of Snail1 knockdown. A: Expression of Snail1. Quantitative RT-PCR for Snail1 expression after Snail1 knockdown using shRNA (sh-snail1) or siRNA (Si-snail1). Experiments were performed under normoxia. (*P < 0.05 compared to control; n = 3 replicate experiments). B: Expression of E-cadherin and N-cadherin after Snail1 knockdown. Immunocytochemical stain for E-cadherin and N-cadherin in Snail1 knockdown and control cells. Experiments were performed under normoxia. C: Western blot analysis for Snail1, E-cadherin, and N-cadherin expression in WM115A cells transfected with Si-Snail1 or Sh-snail1 (n = 3 replicate experiments). Experiments were performed under normoxia. D: Cell cycle analysis. Cells in G2-M and S phases were analyzed by FACS analysis (n = 3 replicate experiments). Experiments were performed under normoxia. E: Cell survival under normoxia and hypoxia. Snail1 knockdown WM115A cells and control cells were cultured under 1% O2 or room O2 for 16 hours (n = 3 replicate experiments; *P < 0.01 compared with control). F: Cell migration assay under normoxia and hypoxia. Wound healing assay using WM115A with Snail1 knockdown (n = 3 replicate experiments).

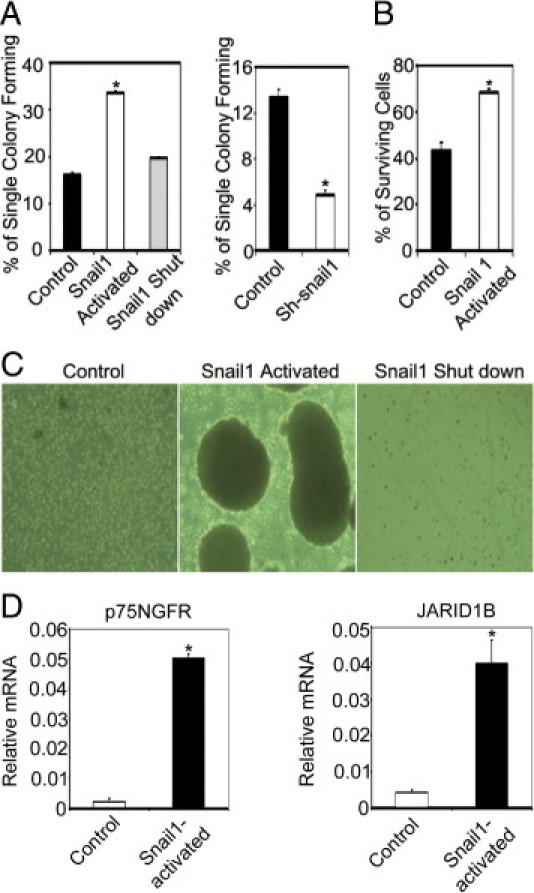

Snail1 and Cancer Stem-Like Cell Phenotypes

Because Snail1 is a neural crest stem cell transcription factor,44 we studied whether Snail1 overexpression can induce stem-like melanoma cell phenotypes. To examine this, we performed limiting dilution assays and showed that the cell proliferation capacity of melanoma cells was correlated to Snail1 expression. When we turned on Snail1 expression in WM115A, WM35, WM3523A, and 1205Lu cells, the colony formation capacity from single melanoma cells was significantly increased (Figure 6A; see also Supplemental Figure 1B at http://ajp.amjpathol.org); when we decreased Snail1 expression by eliminating tamoxifen from the culture medium (Figure 6A, left panel; see also Supplemental Figure S1B at http://ajp.amjpathol.org) or knocking down endogenous Snail1 expression (Figure 6A, right panel; see also Supplemental Figure S1B at http://ajp.amjpathol.org), the colony formation capacity decreased significantly. Stem cells are known to be more resistant to hypoxic insult,45 and we tested whether snail1 expression is associated with resistance to hypoxia. Snail1 over-expressing cells were significantly more resistant to hypoxic insult than control cells (Figure 6B; see also Supplemental Figure S1C at http://ajp.amjpathol.org), whereas knockdown of Snail1 resulted in decreased tolerance to hypoxic insult (see Supplemental Figure S1C at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). We have previously shown that melanoma stem-like cells may form spheroids when cultured in human embryonic stem cell culture medium.46 When Snail1 over-expressing melanoma cells were cultured in human embryonic stem cell medium, they acquired the ability to form spheroids, whereas control or Snail1 knockdown cells could not grow as spheroids under the same culture conditions (Figure 6C). p75NGFR and JARID1B have been used as markers for stem-like subpopulation of melanoma cells,47, 48 and we examined their expression in the sphere-forming cells and found that both p75NGFR and JARID1B expression levels were significantly increased compared to the controls (Figure 6D).

Figure 6.

Snail1 activation induces cancer stem-like cell phenotypes. A: Cell proliferation capacity. Limiting dilution assay was performed and single cells were followed for 14 days using control and WM115A cells with pWZL-Blast-ER-Snail1 (left panel) or control and tumor cells with pGIPZ-Snail1 (right panel). The number of colonies formed was counted and averaged in 3 replicate experiments. (*P < 0.01 comparing to control). B: Hypoxia tolerance assay. Same number of control and WM115A cells with pWZL-Blast-ER-Snail1 were seeded and cultured under 1% O2 for 16 hours (n = 3 replicate experiments). (*P < 0.05 comparing to control). Survival cells were counted. C: Spheroid formation. WM115A cells with pWZL-Blast-ER-Snail1 were cultured in the hESMC4 medium in ultra-low attachment plates. After 2 weeks, photographs were taken of the spheroids at 100× magnification. D: Expression of p75NGFR and JARID1B. Quantitative RT-PCR for p75NGFR and JARID1B expression in sphere-forming cells with pWZL-Blast-ER-Snail1. (*P < 0.05 compared to control; n = 3 replicate experiments).

Effects of Snail1 Expression in Vivo

We then tested the effects of Snail1 on melanoma tumor growth and metastasis in vivo. Tumor cells with pWZL-Blast-ER-Snail1, pGIPZ-shRNA-Snail1, and respective controls were injected into flanks of nude mice, and these mice were sacrificed after 5 weeks. Necropsies were performed and metastasis was defined by tumor cells in any organs, which was documented by histology. Activation of inducible Snail1 in melanoma cells resulted in significantly larger xenografts with more metastasis compared to control cells (Figure 7, A and B). Melanoma cells in which Snail1 was knocked down formed significantly smaller xenografts and none of the mice that received these xenografts developed metastasis (Figure 7, A and B). In addition, we harvested tumor tissue from the xenografts and confirmed Snail1 expression in the tissues. E-cadherin, N-cadherin, and Twist expression levels correlated well with Snail1 expression levels in these xenografts (Figure 7, C and D).

Figure 7.

Snail1 increases melanoma growth and metastasis in vivo. A: Subcutaneous xenografts; 2 × 106 of control, WM115A with pWZL-Blast-ER-Snail1, WM115A with pGIPZ-Snail1 were injected subcutaneously in the flanks of nude mice (n = 10), and these mice were followed for 5 weeks. Representative primary xenografts are shown on the left panel and average tumor weights are shown on the right panel (*P < 0.05 compared with control). B: Internal organ metastasis rate (*P < 0.01 compared with control). C:Snail1, E-cadherin, N-cadherin, and Twist gene expression in xenografts. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed to measure gene expression. D: N-cadherin, Snail1, E-cadherin, and Twist protein expression in the xenografts was assayed using Western blots (representative blot from three experiments).

Discussion

Hypoxia is known to contribute to tumor metastasis and poor patient outcome in many different types of cancer.4, 5, 6, 10 In this study, we demonstrated that Snail1 promotes melanoma drug resistance and progression. Increased Snail1 expression results in acquisition of cancer stem cell-like features and increased metastatic capacity. On the other hand, knockdown of Snail1 expression decreases cell proliferation and metastasis. Snail1 expression is regulated by hypoxia through HIF-2α in melanoma cells. These data suggest that Snail1 is a crucial transcription factor mediating the effects of hypoxia on melanoma cells.

Snail1 is a major transcription factor governing E-cadherin expression, which is known to be involved in melanoma progression. Decreased E-cadherin levels in melanoma tissues are associated with tumor metastasis and recurrence.31 Our results show that the effect of hypoxia on E-cadherin expression is mediated through Snail1 in melanoma. Elevated Snail1 expression enhances melanoma migratory capacity and resistance to chemotherapeutic agents, whereas knockdown of Snail1 expression significantly reduces melanoma resistance to chemotherapeutic reagents and their metastatic capability. Recent findings suggest that Snail1 may accelerate melanoma metastasis through induction of immunosuppression by (thrombospondin-1 (TSP1)-mediated dendritic cell inhibition.49 These data suggest that Snail1 may have multiple roles during melanoma progression.

Snail1 is a transcription factor involved in neural crest stem cell self-renewal.44 It has been shown that Aldehyde dehydrogenase-1 (ALDH1)+-lineage cells in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC) that possess features of cancer stem-like cells also expressed Snail1.50 This work also showed that a knockdown of Snail1 expression significantly inhibited cancer stem-like properties and sensitivity to chemoradiotherapy for ALDH1+ cells was improved with Snail1 knockdown.50 We have previously shown that melanoma cancer stem-like cells can form spheroids when cultured in human embryonic stem cell culture medium and these cells are highly tumorigenic.46 In this study, we expand on these findings to show that Snail1 overexpression also induces cancer stem-like cell phenotypes in melanoma cells and these cells became more resistant to chemotherapeutic agents. To our knowledge, our study is the first to show that Snail1 overexpression may result in acquisition of cancer stem cell-like features. Thus, Snail1 may contribute to melanoma progression through induction of cancer stem-like cells in melanoma.

Hypoxia is well known to induce tumor progression and treatment resistance.51 We showed that tumor cells that survived hypoxic treatment are more resistant to cytotoxic drugs, such as cisplatin and temozolomide, and these cells have higher proliferative and migratory capacity. The phenotype changes are correlated well with Snail1 expression levels in melanoma cells. Two potential HREs have been identified within the Snail1 promoter. Both HIF-1α and HIF-2α can potentially bind to the HREs and activate Snail1 transcription in mouse endothelial cells.36 However, HIF interaction with Snail1 appears to be more complicated in human Snail1 expression in epithelial cancer cells is clearly increased after hypoxic treatment.52, 53 Our results support the finding and suggest that Snail1 expression is regulated by HIF-2α but not HIF-1α in melanoma cells. However, our ChIP assay failed to detect direct binding of HIF-1α or HIF-2α to the promoter region, suggesting that HIF-2α may interact with HREs in other regions or the interaction may be mediated through other pathways. Indeed, a 3′ enhancer controlling Snail expression has been discovered in melanoma cells and this enhance is specific in melanoma because it is not present in melanocytes and keratinocytes.54 In addition, it has been shown that Notch intracellular domain can recruit HIF-1α and bind to the CSL-binding motif (−847 to −839 bp upstream of the transcription start site) in snail1 promoter in SKOV-3 cells.37 We are currently investigating on how HIF-2α regulates Snail1 in melanoma cells, in detail.

Taken together, our data indicates that Snail1 is a crucial transcription factor governing the effects of hypoxia on melanoma cells. Our findings support a critical role for Snail1 in melanoma progression through the regulation of metastasis and resistance to chemotherapeutic agents. Our results suggest that Snail1 is a relevant therapeutic target for melanoma.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Meenhard Herlyn (Wistar Institute) for providing the melanoma cell lines used in the studies, Dr. Frank Lee (University of Pennsylvania) for the pCDNA3-HIF-1α plasmid, and Dr. Volker Haase (Vanderbilt University Medical Center) for the pGFP-HIF2α plasmid. We thank Dr. Kristen Huang for preparation of this manuscript, and Xinjiang Wu for helping with the immunocytochemistry pictures.

Footnotes

Supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (CA-116103, CA-093372 and AR-054593 to X.X.).

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://ajp.amjapthol.org or at doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.08.038.

Supplementary data

A: Western blot analysis for Snail1 and E-cadherin expression in WM35, 3523A and 1205Lu control, snail1 activated, snail1 shut down and sh-snail1 cells (n = 3 replicate experiments).B: Colony formation capacity. Limiting dilution assay was performed and single cells were followed for 14 days using control and WM35, 3523A and 1205Lu cells with inducible Snail1 or snail1 shutdown and Snail1 knockdown cells. The number of colonies formed was counted and averaged in 3 replicate experiments (* indicates p < 0.01 comparing to control). C: Cell survival under hypoxia. Control, snail1 activated, snail1 shut down and sh-snail1 WM35, 3523A and 1205Lu cells were cultured under 1% O2 for 16 hours (n = 3 replicate experiments, *p < 0.01 compared with control).

A: Graphical representation of triplicate experiments of wound closure times in 3 other different melanoma cell lines (WM35, 3523A, 1205Lu) infected with control, snail1 activated, snail1 shut down and sh-snail1 as described above (n = 3 replicate experiments).B: Western blot analysis for Snail1 expression in WM115A control, snail1 activated and after removed the tamoxifen from the culture 1, 3, 6 days (n = 3 replicate experiments).

References

- 1.Greenlee R.T., Murray T., Bolden S., Wingo P.A. Cancer statistics, 2000. CA Cancer J Clin. 2000;50:7–33. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.50.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wingo P.A., Ries L.A., Giovino G.A., Miller D.S., Rosenberg H.M., Shopland D.R., Thun M.J., Edwards B.K. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1973–1996, with a special section on lung cancer and tobacco smoking. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:675–690. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.8.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rigel D.S., Carucci J.A. Malignant melanoma: prevention, early detection, and treatment in the 21st century. CA Cancer J Clin. 2000;50:215–236. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.50.4.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; quiz 237–240

- 4.Brizel D.M., Scully S.P., Harrelson J.M., Layfield L.J., Bean J.M., Prosnitz L.R., Dewhirst M.W. Tumor oxygenation predicts for the likelihood of distant metastases in human soft tissue sarcoma. Cancer Res. 1996;56:941–943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sundfor K., Lyng H., Rofstad E.K. Tumour hypoxia and vascular density as predictors of metastasis in squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Br J Cancer. 1998;78:822–827. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walenta S., Salameh A., Lyng H., Evensen J.F., Mitze M., Rofstad E.K., Mueller-Klieser W. Correlation of high lactate levels in head and neck tumors with incidence of metastasis. Am J Pathol. 1997;150:409–415. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Imtiyaz H.Z., Williams E.P., Hickey M.M., Patel S.A., Durham A.C., Yuan L.J., Hammond R., Gimotty P.A., Keith B., Simon M.C. Hypoxia-inducible factor 2alpha regulates macrophage function in mouse models of acute and tumor inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:2699–2714. doi: 10.1172/JCI39506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwickert G., Walenta S., Sundfor K., Rofstad E.K., Mueller-Klieser W. Correlation of high lactate levels in human cervical cancer with incidence of metastasis. Cancer Res. 1995;55:4757–4759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hockel M., Schlenger K., Aral B., Mitze M., Schaffer U., Vaupel P. Association between tumor hypoxia and malignant progression in advanced cancer of the uterine cervix. Cancer Res. 1996;56:4509–4515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rofstad E.K., Danielsen T. Hypoxia-induced metastasis of human melanoma cells: involvement of vascular endothelial growth factor-mediated angiogenesis. Br J Cancer. 1999;80:1697–1707. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar S.M., Yu H., Edwards R., Chen L., Kazianis S., Brafford P., Acs G., Herlyn M., Xu X. Mutant V600E BRAF increases hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha expression in melanoma. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3177–3184. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaupel P., Kallinowski F., Okunieff P. Blood flow, oxygen and nutrient supply, and metabolic microenvironment of human tumors: a review. Cancer Res. 1989;49:6449–6465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang M.H., Wu K.J. TWIST activation by hypoxia inducible factor-1 (HIF-1): implications in metastasis and development. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:2090–2096. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.14.6324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valencak J., Kittler H., Schmid K., Schreiber M., Raderer M., Gonzalez-Inchaurraga M., Birner P., Pehamberger H. Prognostic relevance of hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha expression in patients with melanoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e962–e964. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jawahir M., Nicholas S.A., Coughlan K., Sumbayev V.V. Apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) and HIF-1alpha protein are essential factors for nitric oxide-dependent accumulation of p53 in THP-1 human myeloid macrophages. Apoptosis. 2008;13:1410–1416. doi: 10.1007/s10495-008-0267-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiavarina B., Whitaker-Menezes D., Migneco G., Martinez-Outschoorn U.E., Pavlides S., Howell A., Tanowitz H.B., Casimiro M.C., Wang C., Pestell R.G., Grieshaber P., Caro J., Sotgia F., Lisanti M.P. HIF1-alpha functions as a tumor promoter in cancer associated fibroblasts, and as a tumor suppressor in breast cancer cells: autophagy drives compartment-specific oncogenesis. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:3534–3551. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.17.12908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kakinuma Y., Miyauchi T., Suzuki T., Yuki K., Murakoshi N., Goto K., Yamaguchi I. Enhancement of glycolysis in cardiomyocytes elevates endothelin-1 expression through the transcriptional factor hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha. Clin Sci (Lond) 2002;103(Suppl 48):210S–214S. doi: 10.1042/CS103S210S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Covello K.L., Kehler J., Yu H., Gordan J.D., Arsham A.M., Hu C.J., Labosky P.A., Simon M.C., Keith B. HIF-2alpha regulates Oct-4: effects of hypoxia on stem cell function, embryonic development, and tumor growth. Genes Dev. 2006;20:557–570. doi: 10.1101/gad.1399906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin C.M., Ferdous A., Gallardo T., Humphries C., Sadek H., Caprioli A., Garcia J.A., Szweda L.I., Garry M.G., Garry D.J. Hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha transactivates Abcg2 and promotes cytoprotection in cardiac side population cells. Circ Res. 2008;102:1075–1081. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.161729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giatromanolaki A., Arvanitidou V., Hatzimichael A., Simopoulos C., Sivridis E. The HIF-2alpha/VEGF pathway activation in cutaneous capillary haemangiomas. Pathology. 2005;37:149–151. doi: 10.1080/00313020400025011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee J.M., Dedhar S., Kalluri R., Thompson E.W. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition: new insights in signaling, development, and disease. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:973–981. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200601018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christofori G. New signals from the invasive front. Nature. 2006;441:444–450. doi: 10.1038/nature04872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mak P., Leav I., Pursell B., Bae D., Yang X., Taglienti C.A., Gouvin L.M., Sharma V.M., Mercurio A.M. ERbeta impedes prostate cancer EMT by destabilizing HIF-1alpha and inhibiting VEGF-mediated snail nuclear localization: implications for Gleason grading. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:319–332. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beltran M., Puig I., Pena C., Garcia J.M., Alvarez A.B., Pena R., Bonilla F., de Herreros A.G. A natural antisense transcript regulates Zeb2/Sip1 gene expression during Snail1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Genes Dev. 2008;22:756–769. doi: 10.1101/gad.455708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu M., Smolen G.A., Zhang J., Wittner B., Schott B.J., Brachtel E., Ramaswamy S., Maheswaran S., Haber D.A. A developmentally regulated inducer of EMT: LBX1 contributes to breast cancer progression. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1737–1742. doi: 10.1101/gad.1809309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ding W., You H., Dang H., LeBlanc F., Galicia V., Lu S.C., Stiles B., Rountree C.B. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of murine liver tumor cells promotes invasion. Hepatology. 2010;52:945–953. doi: 10.1002/hep.23748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huber M.A., Kraut N., Beug H. Molecular requirements for epithelial-mesenchymal transition during tumor progression. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:548–558. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cano A., Perez-Moreno M.A., Rodrigo I., Locascio A., Blanco M.J., del Barrio M.G., Portillo F., Nieto M.A. The transcription factor snail controls epithelial-mesenchymal transitions by repressing E-cadherin expression. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:76–83. doi: 10.1038/35000025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiao W., Miyazaki K., Kitajima Y. Inverse correlation between E-cadherin and Snail expression in hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines in vitro and in vivo. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:98–101. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yokoyama K., Kamata N., Hayashi E., Hoteiya T., Ueda N., Fujimoto R., Nagayama M. Reverse correlation of E-cadherin and snail expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma cells in vitro. Oral Oncol. 2001;37:65–71. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(00)00059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poser I., Dominguez D., de Herreros A.G., Varnai A., Buettner R., Bosserhoff A.K. Loss of E-cadherin expression in melanoma cells involves up-regulation of the transcriptional repressor Snail. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:24661–24666. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011224200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Massoumi R., Kuphal S., Hellerbrand C., Haas B., Wild P., Spruss T., Pfeifer A., Fassler R., Bosserhoff A.K. Down-regulation of CYLD expression by Snail promotes tumor progression in malignant melanoma. J Exp Med. 2009;206:221–232. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yook J.I., Li X.Y., Ota I., Hu C., Kim H.S., Kim N.H., Cha S.Y., Ryu J.K., Choi Y.J., Kim J., Fearon E.R., Weiss S.J. A Wnt-Axin2-GSK3beta cascade regulates Snail1 activity in breast cancer cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1398–1406. doi: 10.1038/ncb1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vincent T., Neve E.P., Johnson J.R., Kukalev A., Rojo F., Albanell J., Pietras K., Virtanen I., Philipson L., Leopold P.L., Crystal R.G., de Herreros A.G., Moustakas A., Pettersson R.F., Fuxe J. A SNAIL1-SMAD3/4 transcriptional repressor complex promotes TGF-beta mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:943–950. doi: 10.1038/ncb1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barbera M.J., Puig I., Dominguez D., Julien-Grille S., Guaita-Esteruelas S., Peiro S., Baulida J., Franci C., Dedhar S., Larue L., Garcia de Herreros A. Regulation of Snail transcription during epithelial to mesenchymal transition of tumor cells. Oncogene. 2004;23:7345–7354. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luo D., Wang J., Li J., Post M. Mouse snail is a target gene for HIF. Mol Cancer Res. 2011;9:234–245. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-10-0214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sahlgren C., Gustafsson M.V., Jin S., Poellinger L., Lendahl U. Notch signaling mediates hypoxia-induced tumor cell migration and invasion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:6392–6397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802047105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu H., McDaid R., Lee J., Possik P., Li L., Kumar S.M., Elder D.E., Van Belle P., Gimotty P., Guerra M., Hammond R., Nathanson K.L., Dalla Palma M., Herlyn M., Xu X. The role of BRAF mutation and p53 inactivation during transformation of a subpopulation of primary human melanocytes. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:2367–2377. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.081057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu S., Yu M., He Y., Xiao L., Wang F., Song C., Sun S., Ling C., Xu Z. Melittin prevents liver cancer cell metastasis through inhibition of the Rac1-dependent pathway. Hepatology. 2008;47:1964–1973. doi: 10.1002/hep.22240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu H., Fang D., Kumar S.M., Li L., Nguyen T.K., Acs G., Herlyn M., Xu X. Isolation of a novel population of multipotent adult stem cells from human hair follicles. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:1879–1888. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Evdokimova V., Tognon C., Ng T., Ruzanov P., Melnyk N., Fink D., Sorokin A., Ovchinnikov L.P., Davicioni E., Triche T.J., Sorensen P.H. Translational activation of snail1 and other developmentally regulated transcription factors by YB-1 promotes an epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:402–415. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Casal C., Torres-Collado A.X., Plaza-Calonge Mdel C., Martino-Echarri E., Ramon Y.C.S., Rojo F., Griffioen A.W., Rodriguez-Manzaneque J.C. ADAMTS1 contributes to the acquisition of an endothelial-like phenotype in plastic tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70:4676–4686. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoek K., Rimm D.L., Williams K.R., Zhao H., Ariyan S., Lin A., Kluger H.M., Berger A.J., Cheng E., Trombetta E.S., Wu T., Niinobe M., Yoshikawa K., Hannigan G.E., Halaban R. Expression profiling reveals novel pathways in the transformation of melanocytes to melanomas. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5270–5282. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sailer M.H., Hazel T.G., Panchision D.M., Hoeppner D.J., Schwab M.E., McKay R.D. BMP2 and FGF2 cooperate to induce neural-crest-like fates from fetal and adult CNS stem cells. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:5849–5860. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heddleston J.M., Li Z., Lathia J.D., Bao S., Hjelmeland A.B., Rich J.N. Hypoxia inducible factors in cancer stem cells. Br J Cancer. 2010;102:789–795. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fang D., Nguyen T.K., Leishear K., Finko R., Kulp A.N., Hotz S., Van Belle P.A., Xu X., Elder D.E., Herlyn M. A tumorigenic subpopulation with stem cell properties in melanomas. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9328–9337. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wissmann C., Detmar M. Pathways targeting tumor lymphangiogenesis. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:6865–6868. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zabierowski S.E., Herlyn M. Melanoma stem cells: the dark seed of melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2890–2894. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.5465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kudo-Saito C., Shirako H., Takeuchi T., Kawakami Y. Cancer metastasis is accelerated through immunosuppression during Snail-induced EMT of cancer cells. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yu C.C., Lo W.L., Chen Y.W., Huang P.I., Hsu H.S., Tseng L.M., Hung S.C., Kao S.Y., Chang C.J., Chiou S.H. Bmi-1 Regulates Snail Expression and Promotes Metastasis Ability in Head and Neck Squamous Cancer-Derived ALDH1 Positive Cells. J Oncol. 2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/609259. 2011. pii: 609259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hockel M., Vaupel P. Tumor hypoxia: definitions and current clinical, biologic, and molecular aspects. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:266–276. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.4.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lundgren K., Nordenskjold B., Landberg G. Hypoxia: Snail and incomplete epithelial-mesenchymal transition in breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:1769–1781. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kato Y., Yashiro M., Noda S., Tendo M., Kashiwagi S., Doi Y., Nishii T., Matsuoka J., Fuyuhiro Y., Shinto O., Sawada T., Ohira M., Hirakawa K. Establishment and characterization of a new hypoxia-resistant cancer cell line: OCUM-12/Hypo, derived from a scirrhous gastric carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2010;102:898–907. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Palmer M.B., Majumder P., Green M.R., Wade P.A., Boss J.M. A 3′ enhancer controls snail expression in melanoma cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6113–6120. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A: Western blot analysis for Snail1 and E-cadherin expression in WM35, 3523A and 1205Lu control, snail1 activated, snail1 shut down and sh-snail1 cells (n = 3 replicate experiments).B: Colony formation capacity. Limiting dilution assay was performed and single cells were followed for 14 days using control and WM35, 3523A and 1205Lu cells with inducible Snail1 or snail1 shutdown and Snail1 knockdown cells. The number of colonies formed was counted and averaged in 3 replicate experiments (* indicates p < 0.01 comparing to control). C: Cell survival under hypoxia. Control, snail1 activated, snail1 shut down and sh-snail1 WM35, 3523A and 1205Lu cells were cultured under 1% O2 for 16 hours (n = 3 replicate experiments, *p < 0.01 compared with control).

A: Graphical representation of triplicate experiments of wound closure times in 3 other different melanoma cell lines (WM35, 3523A, 1205Lu) infected with control, snail1 activated, snail1 shut down and sh-snail1 as described above (n = 3 replicate experiments).B: Western blot analysis for Snail1 expression in WM115A control, snail1 activated and after removed the tamoxifen from the culture 1, 3, 6 days (n = 3 replicate experiments).