Abstract

Proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR) thwarts the repair of rhegmatogenous retinal detachments. Currently, there is no effective prevention for PVR. Platelet-derived growth factor receptor α (PDGFRα) is associated with PVR in humans and strongly promotes experimental PVR driven by multiple vitreal growth factors outside the PDGF family. We sought to identify vitreal factors required for experimental PVR and to establish a potential approach to prevent PVR. Vitreous was obtained from normal rabbits or those in which PVR was either developing or stabilized. Normal vitreous contained substantial levels of growth factors and cytokines, which changed quantitatively and/or qualitatively as PVR progressed and stabilized. Neutralizing a subset of these agents in rabbit vitreous eliminated their ability to induce PVR-relevant signaling and cellular responses. A single intravitreal injection of neutralizing reagents for this subset prevented experimental PVR. To identify growth factors and cytokines likely driving PVR in humans, we subjected vitreous from patients with or without PVR to a similar series of analyses. This analysis accurately identified those agents required for vitreous-induced contraction of cells from a patient PVR membrane. We conclude that combination therapy encompassing a subset of vitreal growth factors and cytokines is a potential approach to prevent PVR.

Proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR) remains the most serious sight-threatening complication in patients recovering from surgery to repair retinal detachment.1, 2, 3 Although the incidence of PVR after primary reattachment repair is 5% to 10%, this number rises to 25% in patients whose retinal detachment occurred after severe ocular trauma.4, 5 The need for a pharmacological treatment to prevent PVR and thus improve the success of long-term recovery is paramount. Repeated retinal reattachment surgery is currently the only treatment option for individuals afflicted with PVR. Consequentially, almost half of patients suffering PVR after primary reattachment surgery will experience recurring PVR and near or total vision loss.6, 7

Although the etiology of PVR is not completely understood, the dislocation of cells to vitreous during retinal detachment is widely believed to be a contributing factor. Cells found in the epiretinal membrane (ERM) are retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells, fibroblasts, fibroblast-like cells (which may be dedifferentiated RPEs), glial cells, and to a much lesser extent, macrophages.8, 9, 10, 11, 12 Substantial evidence indicates that PVR is driven by growth factors and cytokines present in the vitreous (see Supplemental Table S1 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org), which promote cellular responses intrinsic to PVR such as cell survival, proliferation, and migration.8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 These growth factors and cytokines are also capable of inducing production of extracellular matrix proteins that are a major component of ERMs. Finally, growth factors and cytokines drive contraction of the retina-associated ERM, which generates traction that can open treated retinal breaks and/or create new ones and thereby compromise vision.

The most common of the 26 animal models of PVR involves intravitreal injection of fibroblasts29 that organize into an ERM, which contracts and thereby detaches the retina. In the context of this model, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) receptor α (PDGFRα), expressed by the injected fibroblasts, is a key determinant of PVR.30, 31, 32 PDGFRα is expressed and activated in ERMs from human donors, indicating an association of PDGFRα with clinical PVR.27, 31, 33

Although PDGF isoforms that activate PDGFRα abound in both human and rabbit PVR vitreous, they do not appear to be responsible for activating PDGFRα.26, 34 An indirect mechanism predominates in which vitreal growth factors outside of the PDGF family promote an intracellular route to activate PDGFRα.35 This indirect mode results in chronic activation of PDGFRα because it circumvents receptor internalization and degradation.36 Importantly, indirectly activated PDGFRα engages a characteristic set of signaling events and cellular responses that are tightly associated with PVR.36 The goal of this study was to identify the subset of vitreal growth factors and cytokines that was required for experimental PVR, and to develop potential therapeutic approaches to protect patients from developing PVR.

Materials and Methods

Growth Factors, Antibodies, and Neutralization Reagents

Recombinant human growth factors were either used directly to treat cells or as standards to quantify vitreal growth factors by Western immunoblot analysis. All antibodies and neutralizing reagents used in this study are detailed in Table 1. Recombinant human PDGF-A, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), interleukin (IL)-8, tumor growth factor-α (TGF-α), TGF-β1, interferon (IFN)-γ, and connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) were purchased from Peprotech (Rocky Hill, NJ), whereas recombinant human epidermal growth factor (EGF), fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-2, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-A were from the National Cancer Institute.

Table 1.

Antibodies and Neutralizing Reagents Used in This Study

| Reagent | Source/specificity | Type⁎ | Effective dose in vitro/in vivo† | Producer | Additional notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRAP | h/h,m,rb | sRfrg | 5/250 μg/mL | ZymoGenetics (Seattle, WA) | PDGFRα(ecd)/IgG-Fc chimera (Wong et al37) |

| sEGFR | h/h,m,rb | sRfrg | 4/200 μg/mL | R&D Systems | EGFR(ecd)/IgG-Fc chimera (traps EGF and TGF-α) |

| α-HGF | g/h,rb | nAb | Manu./50× | R&D Systems | Also used for quantification by IB |

| α-FGF-2 | m/h,rb | nAb | Manu./50× | Millipore | Neutralizes FGF-2 (basic FGF) isoform |

| α-TGF-β | rb/h,rb | nAb | Manu./50× | R&D Systems | Detects all isoforms (TGF-β1, -β2, and -β3) |

| α-IGF-1 | m/h,rb | nAb | Manu./50× | Millipore | Also used for quantification by IB |

| α-IFNγ | m/h,rb | nAb | Manu./50× | Millipore | |

| α-VEGF-A | m/h,rb | nAb | Manu./50× | R&D Systems | |

| α-IL-8 | m/h,rb | nAb | Manu./50× | Millipore | |

| α-IL-6 | m/h,rb | nAb | Manu./50× | Millipore | |

| α-G-CSF | rb/h,rb | nAb | Manu./50× | Millipore | |

| α-PDGF-C | h/h,rb | IB-Ab | 1:2000 (serum) | ZymoGenetics | α-PDGF core, used for IB quantification26 |

| α-PDGFRα | rb/h,m,rb | IB-Ab | 1:1000 (serum) | See Lei et al,26 Wong et al37 | Designated “27P” |

| α-pPDGFRα | rb/h,m,rb | IB-Ab | 200 ng/mL | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Recognizes pY720 |

| α-pPDGFRα | rb/h,m,rb | IB-Ab | 1:2000 (serum) | See Robbins et al33 | Recognizes pY742 |

| α-Akt | rb/h,m | IB-Ab | 100 ng/mL | Cell Signaling | |

| α-pAkt | rb/h,m | IB-Ab | 200 ng/mL | Cell Signaling | |

| α-p53 | m/h,m | IB-Ab | 200 ng/mL | See Lei et al,26 Robbins et al,33 Wong et al37 | |

| α-RasGAP | rb/h,m | IB-Ab | 1:2000 (serum) | Kazlauskas lab | |

| α-CTGF | g/h,m,rb | IB-Ab | 200 ng/mL | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Recognizes both N- and C-terminal CTGF (fragments) |

| HRP-α-m-IgG | g/m | 2nd | Manu. | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | See footnote‡ |

| HRP-α-rb-IgG | g/rb | 2nd | Manu. | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | See footnote‡ |

| isotype IgGs | m,rb,g/con | con | NA | Santa Cruz Biotechnology |

50x, 50-fold higher than recommended (manu.) dose; Ab, antibody; con, non-immune isotype control IgGs; ecd, extracellular domain of receptor; g, goat; h, human; IB, immunoblot; m, mouse; Manu., set according to manufacturer's instructions; NA, not applicable; nAb, neutralizing antibody; pY, phosphotyrosine; rb, rabbit; serum, serum antibody; sRfrg, soluble receptor fragment.

2nd indicates the secondary antibody for Western blot analysis.

The first (or only) value shown is the concentration used in cell-based experiments; the second value is concentration present in rabbit eyes initially following injection.

Enhanced chemiluminescent substrate for horseradish peroxidase detection is from Pierce (Rockford, IL).

Quantifying Growth Factors and Cytokines in Vitreous

A panel of 24 growth factors and cytokines were quantified in individual vitreous samples from rabbits and humans with or without PVR. Multiplex assays were performed to measure 20 of 24 of the growth factors/cytokines, whereas quantitative Western immunoblot analysis was performed to measure the remaining 4.

Multiplex Assay and Analysis

Multiplex bead analysis was performed using two different immunoassay kits obtained from Millipore (Billerica, MA). One, the Milliplex MAP customized 17-Plex Human Cytokine/Chemokine assay was used to measure the vitreal levels of EGF, FGF-2, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), IFNγ, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), TGF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), TNF-β, VEGF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), PDGF-A, PDGF-AB, and PDGF-B. Two, the Milliplex MAP pan-TGF-β1, -2, -3 (3-Plex) assay measured the vitreal levels of activated TGF-β1, TGF-β2, and TGF-β3. Immunoassays were performed based on the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, vitreous samples were added in triplicate wells on a 96-well plate and incubated overnight with a mixture of monoclonal antibody-coated capture beads. Beads were then washed and incubated with biotin-labeled polyclonal anti-human growth factor/cytokine antibodies for 1 hour, after which streptavidin-phycoerythrin was added for 30 minutes. Fluorescent emissions distinct to each growth factor or cytokine were simultaneously measured using the BioPlex Detection System and analyzed using BioPlex software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Growth factor/cytokine concentrations were determined based on a series of standards run in parallel. Results from individual samples (n = 10 for rabbits, n = 5 for humans) belonging to the same group were compiled and statistically analyzed.

Quantitative Western Immunoblot and Analysis

Quantitative Western immunoblot analysis was performed to measure the vitreal levels of HGF, IGF-1, CTGF, and PDGF-C since the multiplex platform is not yet available to measure these factors. An aliquot of the same samples that were subjected to multiplex analysis was used for quantitative Western immunoblot analysis. Vitreous was run on an 8% to 12% SDS-PAGE gel alongside recombinant human growth factor/cytokine standards. Proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes and blotted with α-HGF, α-IGF-1, α-CTGF, or α-PDGF-C detection antibodies (Table 1). Signal intensity was determined by densitometry using Quantity One (Bio-Rad) and growth factor/cytokine concentrations determined based on the known concentrations of standards run on the same gel. In some cases, membranes were stripped and re-probed to quantify multiple growth factors and cytokines from a single gel.

Cell Culture

Primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were obtained at third passage from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Retinal pigment epithelial cells from human PVR membranes (RPEM cells) were derived from a surgically removed membrane of a PVR patient33; these cells were used at passage 4 or 5. Primary rabbit conjunctiva fibroblasts were isolated as described previously.38

MEFs and rabbit conjunctiva fibroblasts were maintained in high glucose-containing Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (hg-DMEM; Gibco BRL/Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). RPE cells were maintained in a 1:1 mixture of hg-DMEM and Ham's F12 medium (Gibco BRL/Invitrogen). All cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere, and cultured in medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 500 U/mL penicillin, and 500 μg/mL streptomycin.

Cell Treatment

For in vitro experiments, near-confluent cultures of cells were starved of serum overnight and treated the next morning. Vitreous used in cell treatments was always an equal-volume mix of several individual samples. For treatment, vitreous was added directly to cells after removal of media. For vitreous treatments involving neutralizations, neutralizing agents were preincubated with vitreous for 30 minutes at room temperature before addition to cells.

Western Blot Analysis

After treatment, cells were washed twice using ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and then lysed by addition of sample buffer [50 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 10% glycerol, 2% SDS, 1% β-mercaptoethanol, 10 mmol/L EDTA, and 0.02% bromophenol blue]. Lysates were incubated on ice for 15 minutes, heated to 95°C for 5 minutes, then clarified by centrifugation at 13,000 × g, 4°C, for 15 minutes. The supernatant was run on an 8% to 12% SDS-PAGE gel. Data presented for all immunoblots in this study are representative of three independent experiments unless otherwise noted. Signal intensity was determined by densitometry using Quantity One (Bio-Rad), standardized to the background and then normalized for loading.

Growth Factor/Cytokine Neutralization

All neutralizing antibodies and ligand traps used in this study are detailed in Table 1.

In Vitro Neutralization Assays

A 2- to 25-fold excess of neutralization reagent was used, based on the concentration of its intended growth factor/cytokine target in the vitreous. An equivalent amount of isotype-matched IgG was used as a control.

Neutralization of Growth Factors/Cytokines in Rabbit Eyes

In rabbits, a 50-fold molar excess over the amount used in vitro was used for each neutralization reagent making up the neutralizing reagent solution rNb. A 14-fold excess of neutralization antibody and a 21-fold excess of ligand Trap persists in vitreous at 1.5 weeks when a 50-fold excess of these molecules are initially injected.34 Control treatments were isotype-matched with equal amounts of IgG.

Cell Contraction Assay

This assay relates to the ability of cells in the ERM to exert traction on the retina (which causes detachment) and is one way to assess the effects of various treatments on the contractility of cells. The assay was performed as previously described.39, 40 Briefly, a cell suspension was prepared containing 1.5 mg/mL of neutralized collagen I at pH 7.2 (INAMED, Fremont, CA) and 1 × 106 cells/mL, and transferred to a 24-well plate pre-incubated with PBS plus 5 μg/μL bovine serum albumin (BSA) for at least 6 hours. Collagen gels were solidified by incubating them at 37°C for 90 minutes. Solidified gels were overlaid with 0.5 mL of DMEM or DMEM plus whatever treatment was used. Medium containing the desired treatment was changed daily. The gel diameter was measured on days 0, 1, 2, and 3. At day 0, the diameter of the gel equals the diameter of the well. Triplicates were performed in each experiment. For each assay, no less that two independent experiments were performed.

Rabbit PVR Model

Adult female (3 to 6 month) Dutch-belted rabbits were purchased from Covance (Denver, PA). PVR was induced in the right eye of rabbits as previously described.30, 38 Briefly, after 1 week of acclimatization, gas vitrectomies were performed in rabbits by injecting 0.1 mL of perfluoropropane (C3F8) (Alcon, Fort Worth, TX) into the vitreous cavity 3 mm posterior to the corneal limbus. A week later, each rabbit was injected with 0.1 mL of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and 0.1 mL DMEM containing 2 × 105 rabbit conjunctival fibroblasts. PRP was included to enhance the severity and consistency of the response to injected cells.30 We also injected 0.1 mL of balanced saline solution containing either the neutralizing reagents (“rNb”), or isotype-matched control immunoglobulin (“IgGs”).

Intraocular pressure was monitored, and retinal status evaluated using an indirect ophthalmoscope and a +30-D fundus lens at days 1, 3, 5, 7, 14, 21, and 28 after injection. PVR was graded across five stages according to the Fastenberg scale of classification41: stage 0, no disease; stage 1, epiretinal membrane formation; stage 2, vitreoretinal traction without retinal detachment; stage 3, localized retinal detachment (of one to two quadrants); stage 4, extensive retinal detachment (of two to four quadrants without complete detachment); stage 5, complete retinal detachment. Signs of toxicity, including intraocular inflammation and retinal hemorrhages, were assessed during each fundus examination. Animals were sacrificed at day 7 or day 28; eyes were enucleated and frozen at −80°C. All surgeries were performed aseptically and in conformance with the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. The Schepens Animal Care and Use Committee approved the protocol used for these animal experiments.

Preparation of Rabbit Vitreous

Rabbit vitreous was extracted from frozen eyes, thawed at room temperature, and centrifuged at 4°C for 5 minutes at 10,000 × g. The resulting clarified supernatants were used for all subsequent analyses.

Patient Vitreous

All patients underwent a standard three-port vitrectomy, with removal of vitreous before pars plana infusion.42 A total of 24 human vitreous samples (12 non-PVR and 12 PVR) were obtained, with individual sample volumes ranging from 0.6 to 1.3 mL. Samples came from two independent sources: 12 (6 PVR and 6 non-PVR) from patient donors at the Ocular Angiogenesis Group, Department of Ophthalmology Academic Medical Center in Meibergdreef, Amsterdam; and 12 (6 PVR and 6 non-PVR) from patient donors at the Vancouver Hospital in association with the University of British Columbia. “Non-PVR” vitreous was obtained from patients with either macular holes or macular puckers (ie, retinal/ocular conditions unrelated to PVR). In all cases, informed written consent was first obtained from patient donors. Institutional review board approval to perform these studies (protocol S-226-0212, “Vitreal Factors in Proliferative Vitreoretinopathy”) was obtained before conducting any experiments. Research involving human specimens adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using either the unpaired t-test, or Mann-Whitney analysis; P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Quantification of Growth Factors in Experimental PVR Vitreous

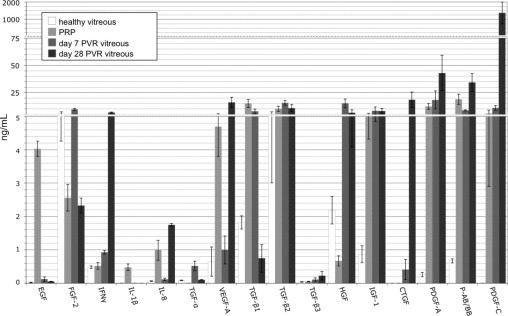

To ascertain which growth factors and cytokines were important contributors to PVR development, multiplex and Western blot analyses were used to quantify the levels of 24 growth factors and cytokines implicated in experimental or clinical PVR (see Supplemental Table S1 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Figure 1 illustrates the growth factors and cytokines present in healthy rabbit vitreous and in platelet-rich plasma (PRP); the sum of these agents represents what injected cells are initially exposed to in our model. Presumably, these are the factors that contribute to initiation of PVR via survival, proliferation, and production of extracellular matrix proteins.43 Furthermore, those factors present at the highest levels likely make the greatest contribution.

Figure 1.

The level of growth factors and cytokines in rabbit vitreous with or without PVR. Vitreous or platelet-rich plasma (PRP) was isolated from rabbits and subjected to either multiplex or Western blot analysis to quantify the level of 24 growth factors or cytokines. Healthy vitreous indicates vitreous isolated from uninjected eyes; PVR vitreous designates vitreous isolated from rabbits that were subjected to the PVR protocol and developed a PVR score of stage 3 or higher. The levels of G-CSF, IL-6, IL-10, MCP-1, TNF-α, TNF-β, and GM-CSF were all below detection (ie, <0.1 ng/mL) and not shown in the graph. Only the active forms of the three TGF-β isoforms were quantified. The bars represent the mean, whereas error bars indicate SD. Vitreous from 10 to 11 rabbits was used in this analysis; within each group, 5 or 6 were used for multiplex analysis and the remainder for Western blot analysis. PRP from three rabbits was used for multiplex analysis and from a second group of three rabbits for Western blot analysis. Three scales, contiguously aligned, were used along the y axis to span the entire range of concentrations measured.

As PVR developed, the profile of growth factors/cytokines in the vitreous changed (Figure 1). Some of the growth factors/cytokines (such as EGF) that were exclusive to PRP were scarcely detectable at day 7. This is consistent with our previous observation that the level of proteins as large as antibodies declined by over 95% from the starting level within 1 week.34 Other growth factors/cytokines (eg, HGF) increased, suggesting that the injected cells and/or the host boosted their production. The level of many growth factors/cytokines (FGF-2, TGF-βs, PDGFs) changed little. The growth factors and cytokines present/abundant in day 7 PVR vitreous represent those most likely to be contributing to the early/progressive stage of PVR.

As PVR ran its course and stabilized, there were further changes to the profile of growth factors and cytokines (Figure 1). At day 28, IFNγ, IL-8, CTGF, and VEGF were at their highest level. These agents may contribute to maintenance/stability of the PVR membrane.

These observations demonstrate that the profile of vitreal growth factors and cytokines changes as PVR develops. Healthy vitreous contains many growth factors and cytokines that contribute to PVR (eg, FGF-2, TGF-βs, HGF).11, 13, 23, 34, 35, 40 As PVR develops, the levels of these agents persist or increase, and additional growth factors and cytokines appear. Based on our profiling experiments, we identify a “set of 9” non-PDGFs that are most abundant during initiation, progression, or maintenance of PVR. This set of 9 consists of EGF, FGF-2, IFNγ, IL-8, TGF-α, VEGF, TGF-β, HGF, and IGF-1.

Vitreal Growth Factors Induced PVR-Relevant Signaling Events

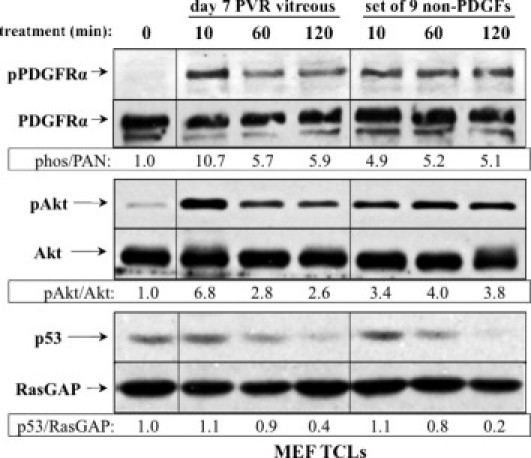

We investigated the ability of the set of 9 to induce signaling events that are associated with experimental PVR, including prolonged activation of PDGFRα and Akt, and suppression of p53 levels.36 For these studies, we used primary fibroblasts because their p53 pathway is intact. Both PVR vitreous and the set of 9 (at a concentration that corresponded to the maximal levels observed in PVR vitreous) activated PDGFRα and triggered prolonged activation of Akt (Figure 2). The greater activation of PDGFRα and Akt by vitreous at the 10-minute time point can be attributed to the PDGFs that are present in PVR vitreous (Figure 1) and activate PDGFRα more strongly at early time points than do non-PDGFs.36

Figure 2.

Signaling events induced by PVR vitreous or the set of 9 non-PDGFs. Serum-starved MEFs were treated for the indicated times with either day 7 rabbit PVR vitreous, or the set of 9 non-PDGFs. Each agent in this set was used at the concentration measured in day 7 rabbit vitreous: FGF-2 (9.5 ng/mL), IGF-1 (8.3 ng/mL), TGF-β1 (7.7 ng/mL), TFG-α (0.5 ng/mL), EGF (0.12 ng/mL), IFN-γ (1.0 ng/mL), IL-8 (0.12 ng/mL), VEGF (1.0 ng/mL), and HGF (15.0 ng/mL). Cells were lysed and subjected to Western blot analysis using the indicated antibodies. Ratios representing normalized band intensities are shown under each pair of immunoblots. The data shown are representative of three independent experiments. TCL, total cell lysate.

Both types of agonists reproducibly induced a >50% decline in the level of p53 at the 120-minute time point (Figure 2). Individual members of the set of 9 provoked only modest activation of PDGFRα when used at a concentration corresponding to their peak level in PVR vitreous (data not shown). At higher concentrations, some of the non-PDGFs (FGF-2, TGF-α, EGF, and HGF) stimulated phosphorylation of PDGFRα to the level attained using the set of 9 (data not shown). These studies indicate that multiple members of the set of 9 are capable of activating PDGFRα and engaging the characteristic signaling events of PVR. Furthermore, their collective efforts are necessary to induce the full response.

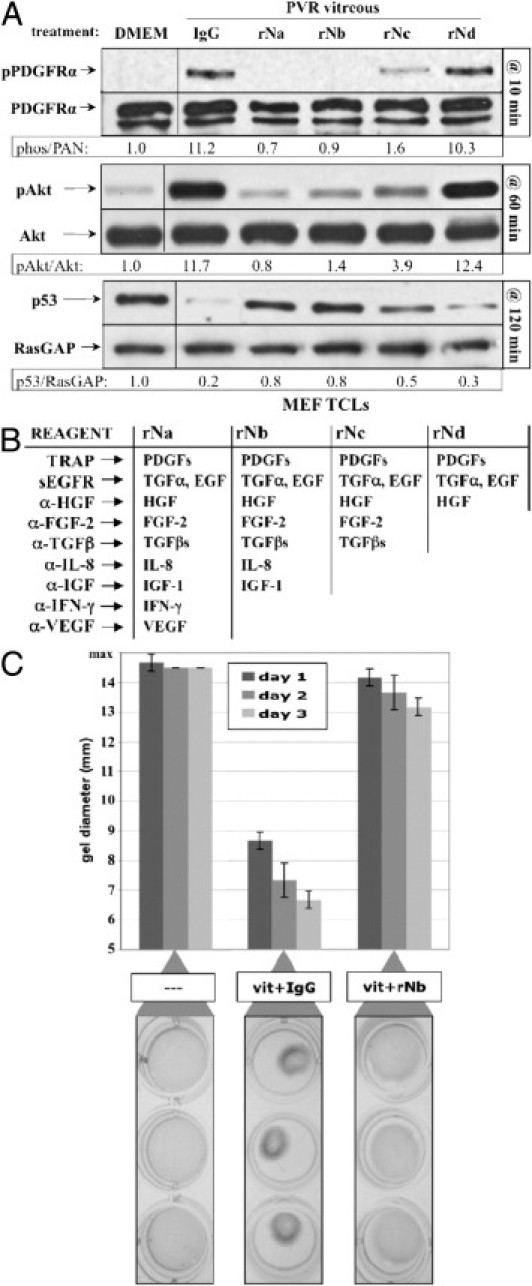

Neutralizing Non-PDGFs Prevented Vitreous-Dependent Signaling Events and Cellular Responses

To determine whether the growth factors and cytokines under investigation encompassed all agents that contributed to vitreous-dependent signaling, we tested whether a cocktail of reagents that neutralized them could completely inhibit PVR vitreous from inducing PVR-relevant signaling events. The minimal neutralizing set that most effectively blocked PVR-relevant signaling events (denoted “rNb”) contained reagents that neutralized EGF, TGF-α, FGF-2, IL-8, TGF-βs, HGF, IGF-1, and PDGFs (Figure 3, A and B). These results indicate that we identified all vitreal agents contributing to stimulation of PVR-relevant signaling events in cells. One of the cellular responses associated with PVR is contraction, which can be modeled in an in vitro setting, and is potently driven by PVR vitreous.40, 44 As shown in Figure 3C, rNb effectively blocked contraction induced by PVR vitreous. The results from these experiments identify the vitreal agents responsible for driving both PVR-relevant signaling events and cellular responses.

Figure 3.

Neutralizing growth factors and cytokines inhibited PVR vitreous–induced signaling events and gel contraction. A: rNb prevented PVR vitreous–induced signaling. Serum-starved MEFs were treated for the indicated duration at 37°C with DMEM alone, day 7 PVR vitreous supplemented with either isotype-control IgG, or one of the four neutralization mixtures (rNa, rNb, rNc, or rNd) listed in B. Cells were harvested, and the resulting samples processed as described in Figure 2. All immunoblots shown are representative of three independent experiments. TCL, total cell lysate. B: Table of neutralization components (left column) and their respective growth factor/cytokine targets (right columns). C: rNb prevented PVR vitreous–induced contraction of collagen gels. MEFs were subjected to the collagen gel contraction assay (Materials and Methods) in the presence of either DMEM (—), or day 7 PVR vitreous (vit) supplemented with IgG or rNb. Gel diameter was measured manually, and data presented are a mean of three independent experiments ± SD (shown as error bars). Images of triplicate wells from a single representative experiment at day 2 are shown below the graph.

In this series of experiments, we routinely included agents to neutralize PDGFs. Although we observed only a minor contribution of vitreal PDGFs to signaling events or cellular responses using vitreous alone,34 we neutralized PDGFs because it is possible that manipulating vitreous could unleash their bioactivity.

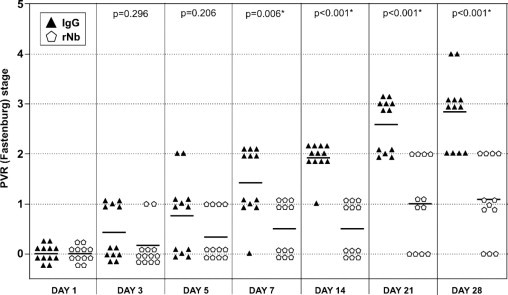

Blocking a Subset of Vitreal Growth Factors and Cytokines Prevented Experimental PVR

The in vitro studies presented in Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 predict that rNb should prevent or at least attenuate experimental PVR. To test this idea, we treated rabbits with a single injection of either rNb or nonimmune IgG at the time that PVR was initiated. Rabbits were monitored over 28 days from initial injection and scored for PVR stage at various times within this interval (Figure 4). The control group (treated with nonimmune IgG) developed PVR with the expected kinetics and frequency: at day 28, 67% of rabbits had retinal detachments (stage 3 PVR or higher). The remaining 33% developed stage 2 PVR that appeared poised to advance to retinal detachment. In contrast, none of the experimental group (treated with rNb) developed retinal detachments. One quarter of the rabbits had no discernable pathology whatsoever, and 42% developed only an epiretinal membrane. Although 33% of the rNb-treated rabbits advanced to stage 2, none of them appeared to be on the brink of retinal detachment, as was the case with stage 2 rabbits from the control group. Neutralization of multiple growth factors and cytokines by the injection of rNb did not result in intraocular inflammation (as visaged by the absence of vitreal and anterior-chamber inflammatory cells), retinal hemorrhages, or degeneration. Furthermore, histological analysis of a retina isolated from an rNb-treated rabbit (PVR stage 0) revealed no observable retinal damage when compared to the retina from the noninjected eye of the same rabbit (see Supplemental Figure S1 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). We conclude that the rNb cocktail completely prevented retinal detachment, and this treatment is well tolerated in rabbits. Furthermore, our in vitro approach to characterize and neutralize vitreal bioactivity accurately predicted the efficacy of an in vivo therapy.

Figure 4.

Neutralizing a subset of vitreal growth factors and cytokines prevented retinal detachment in rabbits. One week after a gas vitrectomy, rabbits received three separate 0.1-mL injections of primary rabbit conjunctival fibroblasts, platelet-rich plasma, and either a 50-fold molecular excess of rNb neutralization mixture (12 rabbits, pentagons), or the equivalent amount of isotype control IgG (12 rabbits, triangles). Rabbits were examined and scored for PVR at the indicated times. Horizontal bars represent the mean of each group. Statistically significant differences between the two groups at each time point were determined by Mann-Whitney analysis (P values are indicated above each time point). Fundus photographs were not recorded because the morphology for a given stage was essentially the same as previously reported.44

Quantification of Growth Factors and Cytokines Present in Human PVR Vitreous

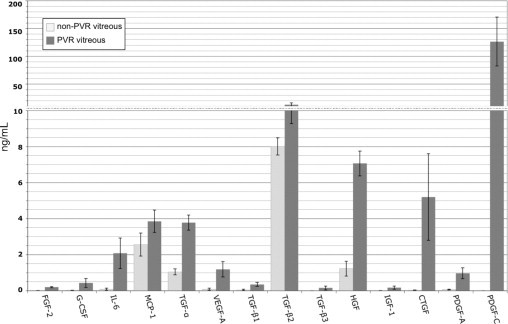

We used multiplex and Western blot analysis to quantify the level of growth factors and cytokines in vitreous from patient donors that either had PVR, or a non-PVR retinal condition (either a macular hole or pucker). We observed that 14 of the 24 agents quantified were present at a concentration greater than 0.1 ng/mL (Figure 5). Our subsequent efforts focused on a large subset of vitreal growth factors/cytokines that were detected in PVR vitreous; these included FGF-2, G-CSF, IL-6, TGF-α, VEGF, TGF-βs, HGF, IGF-1, and PDGFs.

Figure 5.

The level of growth factors and cytokines in vitreous of patients with or without PVR. Same as Figure 1 except that the analysis was performed on vitreous from patient donors. Non-PVR ocular pathologies included macular holes or macular puckers. Both the non-PVR and PVR groups consisted of 12 patients; data represent the mean values for each group, whereas error bars show SD. The levels of EGF, IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-10, TNF-α, TNF-β, GM-CSF, and PDGF-AB/BB were all below detection (ie, <0.1 ng/mL) in all samples and thus omitted from the graph. Only the active forms of the three TGF-β isoforms were quantified. Statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) existed between non-PVR and PVR vitreal levels for the following growth factors/cytokines: FGF-2, G-CSF, IL-6, TGF-α, VEGF, CTGF, TGF-βs, HGF, IGF-1, and PDGFs. Two scales were used along the y axis to adequately span the entire range of concentrations.

Neutralizing a Subset of Vitreal Agents Present in PVR Patients Quenched Vitreous-Mediated Promotion of PVR-Relevant Signaling Events and Cellular Responses

A cocktail containing reagents to neutralize the majority of growth factors and cytokines present in PVR vitreous prevented PVR vitreous–induced activation of PDGFRα, prolonged activation of Akt, and the decline in the level of p53 (see Supplemental Figure S1, A and B, at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Neutralizing just seven of the nine was equally effective, whereas only a partial block was observed when five of the nine were neutralized (see Supplemental Figure S2, A and B, at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Furthermore, the minimal cocktail that completely blocked PVR vitreous–induced signaling in primary fibroblasts, denoted “hNb,” also suppressed the contraction of these cells in collagen (see Supplemental Figure S2C at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). These results identified the vitreal agents that were required for human vitreous to trigger signaling events and cellular responses relevant to PVR.

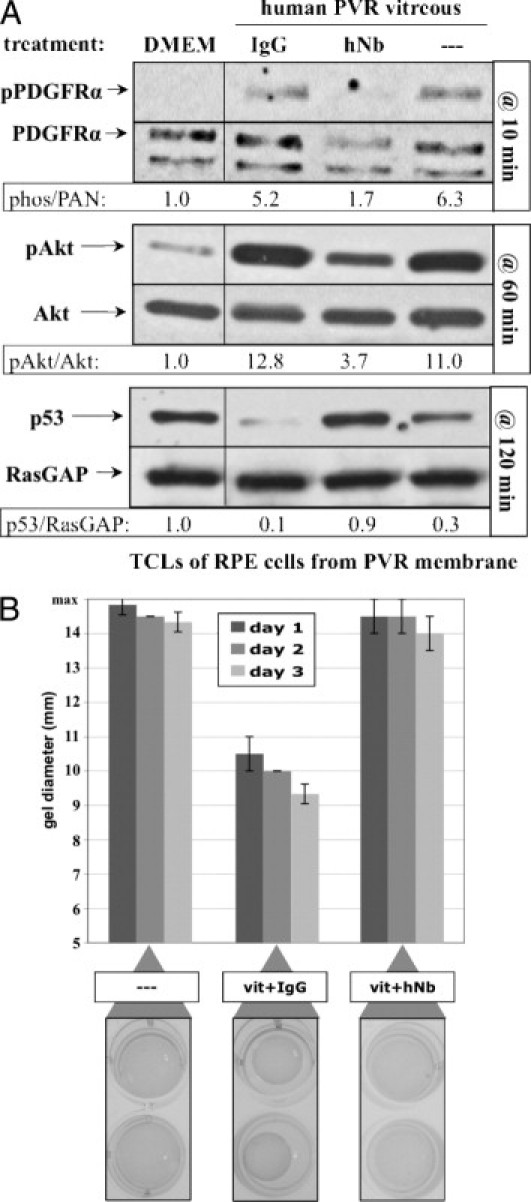

To move one step closer to the clinical setting, we tested the ability of hNb to block PVR vitreous–induced signaling and gel contraction using retinal pigment epithelial cells derived from a RPEM. Addition of hNb to human PVR vitreous effectively blocked PVR-relevant signaling events in RPEMs (Figure 6A). Furthermore, contraction of RPEMs in collagen gels was inhibited when incubated with human PVR vitreous containing hNb, compared to vitreous containing control IgGs (Figure 6B). Thus, the same neutralizing cocktail selected using fibroblasts also works to neutralize PVR relevant signaling in RPE cells derived from a PVR membrane. Taken together, these findings identify the growth factors and cytokines that are required for PVR pathogenic activity in human vitreous, and suggest that neutralizing this relatively small set of agents is a novel prophylactic option to reduce the incidence of PVR among patients undergoing surgery to repair a detached retina.

Figure 6.

A neutralizing cocktail inhibited human PVR vitreous–induced signaling events and gel contraction. A: Neutralization of a subset of vitreal growth factors and cytokines prevented PVR vitreous–induced signaling. Subconfluent cultures of human RPE cells isolated from a PVR membrane were serum starved overnight and then treated for the indicated time at 37°C with either DMEM, or human PVR vitreous supplemented with nothing (—), nonimmune IgG, or hNb (composition described in Supplemental Figure S2B available at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). After stimulation, cells were lysed, and the resulting samples were processed as described in Figure 2. All immunoblots shown are representative of three independent experiments. TCL, total cell lysate. B: hNb prevented PVR vitreous–induced contraction of collagen gels. Human RPE cells isolated from a PVR membrane were subjected to the collagen gel contraction assay (Materials and Methods) in the presence of either DMEM (—), or vitreous (vit) from a PVR patient donor supplemented with IgG or hNb. Gel diameter was measured manually and data presented are a mean of three independent experiments ± SD (shown as error bars). Images of duplicate wells from a single representative experiment at day 2 are shown below the graph. Human vitreous used in this experiment was taken from the same pool used in Supplemental Figure S2 (available at http://ajp.amjpathol.org).

Discussion

In this study, we identified a subset of vitreal growth factors and cytokines that were essential for driving experimental PVR. In rabbit vitreous, the combination of eight classes of growth factors/cytokines was required for eliciting PVR-relevant outcomes in cells: TFG-α, EGF, HGF, FGF-2, TGF-βs, IL-8, IGF-1, and PDGFs (Figure 3). Neutralizing this set of factors effectively protected rabbits from developing retinal detachment (Figure 4). We therefore established a series of in vitro assays that accurately predict therapeutic efficacy in an animal model, and developed a new therapy to prevent experimental PVR. In humans, we found that the combination of seven classes of growth factors and cytokines was essential for PVR-relevant outcomes in cells: TFG-α, HGF, FGF-2, TGF-βs, IL-6, IGF-1, and PDGFs (see Supplemental Figure S2 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Furthermore, neutralizing them prevented PVR-relevant signaling and contraction of collagen gels containing human epithelial cells derived from a PVR membrane (Figure 6). Therefore, the same neutralization strategy that prevented PVR in rabbits also prevented human PVR vitreous from inducing PVR-relevant responses.

Although neutralizing a subset was sufficient to prevent retinal detachment, it did not cause overt retinal toxicity, and the vast majority of the rabbits developed membranes (Figure 4 and data not shown). This suggests that vitreous contained additional growth factors and cytokines. Indeed, vitreous-driven proliferation of fibroblasts was unimpeded by the rNb cocktail (see Supplemental Figure S3 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org; and data not shown). These findings suggest that there are more growth factors and cytokines in vitreous than the 24 we considered in this study, and that targeting those that are required for retinal detachment does not completely negate the bioactivity of vitreous. Finally, the existence of functional relationships between growth factors (eg, TGF-β promotes expression of CTGF45, 46) leaves open the possibility that the growth factors targeted in this study do not encompass all vitreal agents that promote PVR.

The two major proliferative vitreoretinal disorders—PVR and proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR)—are both characterized by an increased vitreal level of pathological mediators, which are important in driving disease progression.8 In experimental PVR, multiple growth factors and cytokines need to be targeted to effectively protect rabbits from developing disease, and the same is likely true for humans (Figure 4, Figure 6).3, 4, 5 In PDR, retinal ischemia induces the production and release of potent vasoproliferative factors into the vitreous such as VEGF and erythropoietin.47, 48, 49 Treatment for PDR has focused on neutralization of VEGF alone, which is effective in only a subset of PDR patients.50 Perhaps combinatorial therapy with additional neutralization would benefit a wider spectrum of PDR patients.

The success of a neutralization-based therapy depends on the efficacy of the reagents injected, their biological duration, and any potential toxicity arising from these reagents. In rabbits, a single injection (of rNb) at day 0 prevented retinal detachment in all animals (n = 12) over the course of 1 month (Figure 4). Although the outlook is encouraging, it would be useful to test the effectiveness of this treatment on alternate models of retinal detachment.29 It is also worth considering a combinatorial approach to therapy. The antioxidant N-acetylcysteine (NAC) prevents retinal detachment in rabbits by blocking the intracellular processes by which non-PDGFs lead to PDGFRα activation.44 A combined therapy involving the neutralization approach presented in this work and NAC treatment would doubly target PVR-driving mechanisms at both the extracellular and intracellular levels.

In as complex a biological environment as vitreous, precise determination of the growth factors and cytokines essential for PVR necessitate both profiling methods (Figure 1, Figure 5) and in vitro neutralization bioassays (Figure 3, Figure 6, and Supplemental Figure S2 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Although profiling is an important first step to identify what factors are present and their quantities, use of the neutralization bioassays allows us to focus on the relevant contributors by systematically eliminating nonessential factors. The use of bioassays also addresses the difficult question of whether factors not being profiled are contributing to disease. Using a combination of profiling and bioassays is thus a powerful strategy to effectively identify the relevant agents present in complex biological samples.

The dispensability of vitreal PDGFs in PVR remains an enigma. Although functional PDGFRαs are essential to disease, PDGF does not appear to mediate receptor activation, despite the abundance of PDGFRα-activating isoforms of PDGF in both rabbit and human PVR vitreous.26, 34 The preference for the indirect route of PDGFRα activation suggests that vitreous contains inhibitors that sequester PDGF or block its interaction with PDGFRα. Further investigation will be essential to elucidate the reason why vitreal PDGFs appear to be underperforming.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Rob van Geest of the Ocular Angiogenesis Group and patient donors from the Academic Medical Center in Meibergdreef, Amsterdam. We also thank Jing Cui and Dr. Joanne Matsubara (University of British Columbia) and patient donors from Vancouver Hospital for generously providing us with clinical vitreous specimens. We also thank our peers at Schepens Eye Research Institute: Jessica Lanzim and Marie Ortega for assistance with the animal experiments and Hetian Lei, Ruta Motiejunaite, and Daniel Lorenzana for reviewing the manuscript and providing constructive input.

Footnotes

Supported by grants from the Department of Defense (WB1XWH-10-1-0392) and National Institutes of Health (EY012509) to A.K., M.-A.R. is an Allergan Horizon Grant in Retina 2011 Fellow. S.M. is supported in part by gifts to the Mukai Fund of the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://ajp.amjpathol.org or at doi:10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.08.043.

Supplementary data

Treatment with rNb did not cause retinal toxicity. Eyes enucleated from a rabbit with stage 0 PVR (at day 28) were fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in methacrylate, sections were prepared and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. A representative region of the section is shown for the non-injected left eye (A) and the rNb-treated right eye (B). Both eyes were from the same rabbit. These data indicate that rNb did not adversely impact the retina. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Identification of a neutralizing cocktail capable of inhibiting human PVR vitreous-induced signaling events and gel contraction. (A) Comparison of different neutralization cocktails for their ability to prevent human PVR vitreous-induced signaling. Serum-starved MEFs were treated for the indicated times at 37°C with DMEM alone (—), PVR vitreous from patient donors supplemented with either isotype-control IgG, or one of the four neutralization cocktails listed in B. Cells were stimulated, harvested, and the resulting lysates processed as described in Figure 2. All immunoblots shown are representative of two independent experiments. (B) Composition of the neutralization cocktails and their respective targets. (C) hNb prevented PVR vitreous-induced contraction of collagen gels. MEFs were subjected to the collagen gel contraction assay (see Materials and Methods) in the presence of either DMEM (—), or vitreous from a PVR patient donor supplemented with IgG or hNb. Gel diameter was measured manually and data presented are a mean of two independent experiments ± SD (shown as error bars). Images of triplicate wells from a single representative experiment at day 2 are shown below the graph. Human vitreous used in this experiment was pooled from 5 patient donors for each group.

Proliferation of rabbit conjunctival fibroblasts was not affected by rNb. Rabbit conjunctival fibroblasts were seeded at 50,000 cells per plate and supplemented with DMEM alone, 10% fetal bovine serum in DMEM, RV-PVR + 10% PRP, RV-PVR + 10% PRP + rNb, or RV-PVR + 10% PRP + IgG. The amount of rNb and IgG was the same as used in the experiment shown in Figure 4. At the time points indicated, cells from each treatment were counted by hemocytometry. The graph presents data from two independent experiments showing mean fold increase in cell number ± SD normalized to the number of cells initially seeded. There were no significant differences between the groups of stimulated cells at any time point (P > 0.05, using a paired t-test). Preliminary studies indicate that RV-PVR effectively promoted the proliferation of fibroblasts in the absence of PRP, and that rNb was unable to reduce its mitogenic potency (data not shown).

References

- 1.Han D. In: Albert D., JW M., DT A., BA B., editors. Elsevier Saunders; Philadelphia, PA: 2008. Proliferative vitreoretinopathy; pp. 2315–2324. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pastor J.C. Proliferative vitreoretinopathy: an overview. Surv Ophthalmol. 1998;43:3–18. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(98)00023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michels R.G., Wilkinson C.P., Rice A. Mosby; St. Louis, MO: 1990. Proliferative retinopathy. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glaser B.M., Cardin A., Biscoe B. Proliferative vitreoretinopathy: The mechanism of development of vitreoretinal traction. Ophthalmology. 1987;94:327–332. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(87)33443-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campochiaro P.A. Mechanisms in ophthalmic disease: pathogenic mechanisms in proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115:237–241. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1997.01100150239014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laqua H., achemer R. Glial cell proliferation in retinal detachment (massive periretinal proliferation) Am J Ophthalmol. 1975;80:602–618. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(75)90390-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryan S.J. Traction retinal detachment: XLIX Edward Jackson Memorial Lecture. Am J Ophthalmol. 1993;115:1–20. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)73518-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banerjee S., Savant V., Scott R.A., Curnow S.J., Wallace G.R., Murray P.I. Multiplex bead analysis of vitreous humor of patients with vitreoretinal disorders. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:2203–2207. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asaria R.H., Kon C.H., Bunce C., Sethi C.S., Limb G.A., Khaw P.T., Aylward G.W., Charteris D.G. Silicone oil concentrates fibrogenic growth factors in the retro-oil fluid. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88:1439–1442. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2003.040402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baudouin C., Fredj-Reygrobellet D., Brignole F., Negre F., Lapalus P., Gastaud P. Growth factors in vitreous and subretinal fluid cells from patients with proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Ophthalmic Res. 1993;25:52–59. doi: 10.1159/000267221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campochiaro P.A., Hackett S.F., Vinores S.A. Growth factors in the retina and retinal pigmented epithelium. Prog Ret Eye Res. 1996;15:547–567. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Canataroglu H., Varinli I., Ozcan A.A., Canataroglu A., Doran F., Varinli S. Interleukin (IL)-6, interleukin (IL)-8 levels and cellular composition of the vitreous humor in proliferative diabetic retinopathy, proliferative vitreoretinopathy, and traumatic proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2005;13:375–381. doi: 10.1080/09273940490518900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harada C., Mitamura Y., Harada T. The role of cytokines and trophic factors in epiretinal membranes: involvement of signal transduction in glial cells. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2006;25:149–164. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.La Heij E.C., van de Waarenburg M.P., Blaauwgeers H.G., Kessels A.G., Liem A.T., Theunissen C., Steinbusch H., Hendrikse F. Basic fibroblast growth factor, glutamine synthetase, and interleukin-6 in vitreous fluid from eyes with retinal detachment complicated by proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;134:367–375. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)01536-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El-Ghrably I.A., Dua H.S., Orr G.M., Fischer D., Tighe P.J. Intravitreal invading cells contribute to vitreal cytokine milieu in proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:461–470. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.4.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choudhury P., Chen W., Hunt R.C. Production of platelet-derived growth factor by interleukin-1 beta and transforming growth factor-beta-stimulated retinal pigment epithelial cells leads to contraction of collagen gels. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997;38:824–833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liou G.I., Pakalnis V.A., Matragoon S., Samuel S., Behzadian M.A., Baker J., Khalil I.E., Roon P., Caldwell R.B., Hunt R.C., Marcus D.M. HGF regulation of RPE proliferation in an IL-1beta/retinal hole-induced rabbit model of PVR. Mol Vis. 2002;8:494–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elner S.G., Elner V.M., Jaffe G.J., Stuart A., Kunkel S.L., Strieter R.M. Cytokines in proliferative diabetic retinopathy and proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Curr Eye Res. 1995;14:1045–1053. doi: 10.3109/02713689508998529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charteris D.G. Growth factors in proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998;82:106. doi: 10.1136/bjo.82.2.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dieudonne S.C., La Heij E.C., Diederen R., Kessels A.G., Liem A.T., Kijlstra A., Hendrikse F. High TGF-beta2 levels during primary retinal detachment may protect against proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:4113–4118. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oshima Y., Sakamoto T., Hisatomi T., Tsutsumi C., Ueno H., Ishibashi T. Gene transfer of soluble TGF-beta type II receptor inhibits experimental proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Gene Ther. 2002;9:1214–1220. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hinton D.R., He S., Jin M.L., Barron E., Ryan S.J. Novel growth factors involved in the pathogenesis of proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Eye (Lond) 2002;16:422–428. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lashkari K., Rahimi N., Kazlauskas A. Hepatocyte growth factor receptor in human RPE cells: implications in proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:149–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mukherjee S., Guidry C. The insulin-like growth factor system modulates retinal pigment epithelial cell tractional force generation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:1892–1899. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kita T., Hata Y., Miura M., Kawahara S., Nakao S., Ishibashi T. Functional characteristics of connective tissue growth factor on vitreoretinal cells. Diabetes. 2007;56:1421–1428. doi: 10.2337/db06-1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lei H., Hovland P., Velez G., Haran A., Gilbertson D., Hirose T., Kazlauskas A. A potential role for PDGF-C in experimental and clinical proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:2335–2342. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cui J.Z., Chiu A., Maberley D., Ma P., Samad A., Matsubara J.A. Stage specificity of novel growth factor expression during development of proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Eye (Lond) 2007;21:200–208. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kon C.H., Occleston N.L., Aylward G.W., Khaw P.T. Expression of vitreous cytokines in proliferative vitreoretinopathy: a prospective study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:705–712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agrawal R.N., He S., Spee C., Cui J.Z., Ryan S.J., Hinton D.R. In vivo models of proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:67–77. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andrews A., Balciunaite E., Leong F.L., Tallquist M., Soriano P., Refojo M., Kazlauskas A. Platelet-derived growth factor plays a key role in proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:2683–2689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cui J., Lei H., Samad A., Basavanthappa S., Maberley D., Matsubara J., Kazlauskas A. PDGF receptors are activated in human epiretinal membranes. Exp Eye Res. 2009;88:438–444. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ikuno Y., Leong F.L., Kazlauskas A. Attenuation of experimental proliferative vitreoretinopathy by inhibiting the platelet-derived growth factor receptor. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:3107–3116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wong C.A., Potter M.J., Cui J.Z., Chang T.S., Ma P., Maberley A.L., Ross W.H., White V.A., Samad A., Jia W., Hornan D., Matsubara J.A. Induction of proliferative vitreoretinopathy by a unique line of human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Can J Ophthalmol. 2002;37:211–220. doi: 10.1016/s0008-4182(02)80112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lei H., Velez G., Hovland P., Hirose T., Gilbertson D., Kazlauskas A. Growth factors outside the PDGF family drive experimental PVR. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:3394–3403. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lei H., Kazlauskas A. Growth factors outside of the platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) family employ reactive oxygen species/Src family kinases to activate PDGF receptor alpha and thereby promote proliferation and survival of cells. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:6329–6336. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808426200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lei H., Velez G., Kazlauskas A. Pathological signaling via platelet-derived growth factor {alpha} involves chronic activation of Akt and suppression of p53. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:1788–1799. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01321-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robbins S.G., Mixon R.N., Wilson D.J., Hart C.E., Robertson J.E., Westra I., Planck S.R., Rosenbaum J.T. Platelet-derived growth factor ligands and receptors immunolocalized in proliferative retinal diseases. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994;35:3649–3663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakagawa M., Refojo M.F., Marin J.F., Doi M., Tolentino F.I. Retinoic acid in silicone and silicone-fluorosilicone copolymer oils in a rabbit model of proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995;36:2388–2395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grinnell F., Ho C.H., Lin Y.C., Skuta G. Differences in the regulation of fibroblast contraction of floating versus stressed collagen matrices. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:918–923. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.2.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ikuno Y., Kazlauskas A. TGFbeta1-dependent contraction of fibroblasts is mediated by the PDGFalpha receptor. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:41–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fastenberg D.M., Diddie K.R., Sorgente N., Ryan S.J. A comparison of different cellular inocula in an experimental model of massive periretinal proliferation. Am J Ophthalmol. 1982;93:559–564. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)77369-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maberley D., Cui J.Z., Matsubara J.A. Vitreous leptin levels in retinal disease. Eye (Lond) 2006;20:801–804. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lei H., Rheaume M.A., Kazlauskas A. Recent developments in our understanding of how platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and its receptors contribute to proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Exp Eye Res. 2010;90:376–381. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lei H., Velez G., Cui J., Samad A., Maberley D., Matsubara J., Kazlauskas A. N-acetylcysteine suppresses retinal detachment in an experimental model of proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:132–140. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grotendorst G.R., Okochi H., Hayashi N. A novel transforming growth factor beta response element controls the expression of the connective tissue growth factor gene. Cell Growth Differ. 1996;7:469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Igarashi A., Okochi H., Bradham D.M., Grotendorst G.R. Regulation of connective tissue growth factor gene expression in human skin fibroblasts and during wound repair. Mol Biol Cell. 1993;4:637–645. doi: 10.1091/mbc.4.6.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aiello L.P., Pierce E.A., Foley E.D., Takagi H., Chen H., Riddle L., Ferrara N., King G.L., Smith L.E. Suppression of retinal neovascularization in vivo by inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) using soluble VEGF-receptor chimeric proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:10457–10461. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee I.G., Chae S.L., Kim J.C. Involvement of circulating endothelial progenitor cells and vasculogenic factors in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. Eye. 2006;20:546–552. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Watanabe D., Suzuma K., Matsui S., Kurimoto M., Kiryu J., Kita M., Suzuma I., Ohashi H., Ojima T., Murakami T., Kobayashi T., Masuda S., Nagao M., Yoshimura N., Takagi H. Erythropoietin as a retinal angiogenic factor in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:782–792. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arevalo J.F., Sanchez J.G., Lasave A.F., Wu L., Maia M., Bonafonte S., Brito M., Alezzandrini A.A., Restrepo N., Berrocal M.H., Saravia M., Farah M.E., Fromow-Guerra J., Morales-Canton V. Intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin®) for diabetic retinopathy at 24-months: the 2008 Juan Verdaguer-Planas Lecture. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2010;6:313–322. doi: 10.2174/157339910793360842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Treatment with rNb did not cause retinal toxicity. Eyes enucleated from a rabbit with stage 0 PVR (at day 28) were fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in methacrylate, sections were prepared and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. A representative region of the section is shown for the non-injected left eye (A) and the rNb-treated right eye (B). Both eyes were from the same rabbit. These data indicate that rNb did not adversely impact the retina. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Identification of a neutralizing cocktail capable of inhibiting human PVR vitreous-induced signaling events and gel contraction. (A) Comparison of different neutralization cocktails for their ability to prevent human PVR vitreous-induced signaling. Serum-starved MEFs were treated for the indicated times at 37°C with DMEM alone (—), PVR vitreous from patient donors supplemented with either isotype-control IgG, or one of the four neutralization cocktails listed in B. Cells were stimulated, harvested, and the resulting lysates processed as described in Figure 2. All immunoblots shown are representative of two independent experiments. (B) Composition of the neutralization cocktails and their respective targets. (C) hNb prevented PVR vitreous-induced contraction of collagen gels. MEFs were subjected to the collagen gel contraction assay (see Materials and Methods) in the presence of either DMEM (—), or vitreous from a PVR patient donor supplemented with IgG or hNb. Gel diameter was measured manually and data presented are a mean of two independent experiments ± SD (shown as error bars). Images of triplicate wells from a single representative experiment at day 2 are shown below the graph. Human vitreous used in this experiment was pooled from 5 patient donors for each group.

Proliferation of rabbit conjunctival fibroblasts was not affected by rNb. Rabbit conjunctival fibroblasts were seeded at 50,000 cells per plate and supplemented with DMEM alone, 10% fetal bovine serum in DMEM, RV-PVR + 10% PRP, RV-PVR + 10% PRP + rNb, or RV-PVR + 10% PRP + IgG. The amount of rNb and IgG was the same as used in the experiment shown in Figure 4. At the time points indicated, cells from each treatment were counted by hemocytometry. The graph presents data from two independent experiments showing mean fold increase in cell number ± SD normalized to the number of cells initially seeded. There were no significant differences between the groups of stimulated cells at any time point (P > 0.05, using a paired t-test). Preliminary studies indicate that RV-PVR effectively promoted the proliferation of fibroblasts in the absence of PRP, and that rNb was unable to reduce its mitogenic potency (data not shown).