Abstract

Objective

To measure within-country wealth-related inequality in the health service coverage gap of maternal and child health indicators in sub-Saharan Africa and quantify its contribution to the national health service coverage gap.

Methods

Coverage data for child and maternal health services in 28 sub-Saharan African countries were obtained from the 2000–2008 Demographic Health Survey. For each country, the national coverage gap was determined for an overall health service coverage index and select individual health service indicators. The data were then additively broken down into the coverage gap in the wealthiest quintile (i.e. the proportion of the quintile lacking a required health service) and the population attributable risk (an absolute measure of within-country wealth-related inequality).

Findings

In 26 countries, within-country wealth-related inequality accounted for more than one quarter of the national overall coverage gap. Reducing such inequality could lower this gap by 16% to 56%, depending on the country. Regarding select individual health service indicators, wealth-related inequality was more common in services such as skilled birth attendance and antenatal care, and less so in family planning, measles immunization, receipt of a third dose of vaccine against diphtheria, pertussis and tetanus and treatment of acute respiratory infections in children under 5 years of age.

Conclusion

The contribution of wealth-related inequality to the child and maternal health service coverage gap differs by country and type of health service, warranting case-specific interventions. Targeted policies are most appropriate where high within-country wealth-related inequality exists, and whole-population approaches, where the health-service coverage gap is high in all quintiles.

الملخص

الغرض

قياس تأثير تباين الثروة داخل البلد على الفجوة الموجودة في التغطية بالخدمات الصحية المتعلقة بمؤشرات صحة الأمومة والطفولة في جنوب الصحراء الأفريقية، وتحديد مقدار مسؤوليتها في فجوة التغطية بالخدمات الصحية الوطنية.

الطريقة

جمعت معطيات تغطية خدمات صحة الطفولة والأمومة في 28 بلداً واقعة جنوب الصحراء الأفريقية من المسح الصحي الديموغرافي للأعوام 2000-2008. وجرى لكل بلد تحديد مؤشر إجمالي التغطية الصحية الوطنية واختيار مؤشرات الخدمة الصحية الفردية. ثم جرى تقسيم المعطيات جمعياً بحسب فجوة التغطية في أغنى شريحة ربعية (أي نسبة الشريحة الربعية التي لا يوجد لديها الخدمة الصحية المطلوبة) والخطر المعزو بين السكان (وهو قياس مطلق لتباين الثروة داخل البلد).

النتائج

في 26 بلداً، تسبب تباين الثروة داخل البلد في حدوث أكثر من ربع إجمالي فجوة التغطية الوطنية. ويمكن لخفض هذا التباين في الثروة خفض الفجوة الموجودة بمقدار يصل من 16% إلى 56%، بحسب كل بلد. وفي ما يتعلق باختيار مؤشرات الخدمات الصحية الفردية، كان تباين الثروة داخل البلد أكثر حدوثاً في خدمات مثل الولادة تحت إشراف قابلات ماهرات والرعاية السابقة للولادة، وكان التباين أقل في تنظيم الأسرة، والتحصين ضد الحصبة، وتلقي الجرعة الثالثة من اللقاح المضاد للخناق والسعال الديكي والكزاز، ومعالجة العدوى التنفسية الحادة في الأطفال أقل من عمر 5 سنوات.

الاستنتاج

تختلف مسؤولية تباين الثروة عن فجوة التغطية بخدمات صحة الأطفال والأمهات بحسب كل بلد وبحسب نوع الخدمة الصحية، مما يستدعي تدخلات نوعية للحالات. أما السياسات المستهدفة فستكون أكثر مناسبة عندما يكون هناك تباين عالٍ في الثروة داخل البلد، وعندما تستهدف الأساليب كل السكان، وعندما تكون فجوة تغطية الخدمات الصحية مرتفعة في جميع الشرائع الربعية.

Resumen

Objetivo

Medir la desigualdad en cuanto a la riqueza de cada país con respecto a las carencias en la cobertura del servicio sanitario de los indicadores de salud materno-infantil en el África subsahariana y cuantificar su contribución a las carencias de cobertura en los servicios sanitarios nacionales.

Métodos

A través de la Encuesta sobre Salud y Demografía de 2000–2008 se obtuvieron los datos de cobertura de los servicios sanitarios materno-infantiles en 28 países del África subsahariana. Para cada uno de los países se determinaron las carencias de cobertura nacional para un índice de cobertura global de servicios sanitarios y para indicadores de servicios sanitarios individuales. Los datos se separaron además en las carencias de cobertura para el quintil más rico (por ejemplo, la proporción del quintil que carecía del servicio sanitario necesario) y el riesgo atribuible a la población (una medida absoluta de la desigualdad en cuanto a riqueza de cada país).

Resultado

En 26 países, la desigualdad nacional en cuanto a la riqueza, constituyó más de un cuarto de las carencias de cobertura total del país. Si se redujera dicha desigualdad, estas carencias disminuirían entre un 16% y un 56%, dependiendo del país. En cuanto a los indicadores de servicios sanitarios individuales, la desigualdad en cuanto a riqueza fue más palpable en servicios como la asistencia profesional al parto y la asistencia prenatal, y menos destacada en la planificación familiar, la vacunación contra el sarampión, la recepción de una tercera dosis de la vacuna contra la difteria, la tos ferina y el tétano y en el tratamiento de infecciones respiratorias agudas en niños menores de 5 años.

Conclusión

La contribución de la desigualdad en cuanto a riqueza en las carencias de cobertura de servicios sanitarios materno-infantiles varía en cada país y según el servicio sanitario, por lo que necesita intervenciones específicas para cada caso. Las normativas específicas son las más adecuadas cuando se producen casos de marcada desigualdad en cuanto a riqueza dentro de un país, y los enfoques globales, para aquellos países con unas carencias de cobertura de servicios elevadas en todos los quintiles de población.

Résumé

Objectif

Mesurer l'inégalité intra-nationale liée à la richesse dans l'écart de couverture sanitaire d'indicateurs de santé maternelle et infantile en Afrique sub-saharienne et quantifier sa contribution à l'écart national de couverture sanitaire.

Méthodes

Les données de couverture sanitaire maternelle et infantile dans 28 pays d'Afrique sub-saharienne ont été tirées de l'Enquête démographique et sanitaire de 2000-2008. Pour chaque pays, l'écart national de couverture a été déterminé pour un indice de couverture sanitaire globale et pour des indicateurs sanitaires spécifiques. Les données ont ensuite été ventilées de manière additive dans l'écart de couverture dans le quintile le plus riche (soit la proportion du quintile sans service sanitaire requis) et le risque imputable à la population (une mesure absolue de l'inégalité intra-nationale liée à la richesse).

Résultats

Dans 26 pays, l'inégalité intra-nationale de richesse explique plus d'un quart de l'écart national de couverture globale. Réduire cette inégalité pourrait réduire cet écart de 16% à 56%, selon les pays. Pour les indicateurs sanitaires spécifiques, l'inégalité liée à la richesse était plus fréquente dans des services comme les services d'accouchement et de soins prénatals qualifiés, et moins fréquente pour la planification familiale, la vaccination contre la rougeole, l'administration de la troisième dose de vaccin contre la diphtérie, la coqueluche et le tétanos et le traitement des infections respiratoires aiguës chez les enfants de moins de 5 ans.

Conclusion

L'impact de l'inégalité de richesse sur l'écart de couverture sanitaire maternelle et infantile diffère selon les pays et le type de service sanitaire, justifiant des interventions au cas par cas. Des politiques ciblées sont plus appropriées quand l'inégalité de richesse intra-nationale est élevée, et des approches visant l'ensemble de la population quand l'écart de couverture sanitaire est élevé dans tous les quintiles.

Резюме

Цель

Измерить связанное с материальным благосостоянием внутристрановое неравенство в отношении разрыва в охвате медико-санитарными услугами в области охраны здоровья матери и ребенка в странах Африки к югу от Сахары и определить его количественную долю в общестрановом показателе разрыва в охвате медико-санитарными услугами.

Метод

Данные об охвате услугами в области охраны здоровья матери и ребенка по 28 странам Африки к югу от Сахары были взяты из материалов Обследования в области народонаселения и здравоохранения за 2000–2008 годы. Для каждой страны общенациональный разрыв в охвате определялся для совокупного индекса охвата медико-санитарными услугами и избранных индикаторов по конкретным медико-санитарным услугам. После этого в данных были дополнительно выделены разрыв в охвате в богатейшем квинтиле (т. е. доля квинтиля, не получающего требуемой медико-санитарной услуги) и добавочный популяционный риск (абсолютная мера связанного с материальным благосостоянием внутристранового неравенства).

Результат

В 26 странах на долю связанного с материальным благосостоянием внутристранового неравенства приходилось более ¼ совокупного общенационального разрыва в охвате. Снижение этого неравенства позволило бы сократить разрыв на 16–56%, в зависимости от страны. Среди избранных показателей по конкретным медико-санитарным услугам неравенство, связанное с материальным благосостоянием, было более широко распространено в таких услугах, как квалифицированные родовспоможение и дородовой уход, и менее широко – в таких как планирование семьи, иммунизация против кори, прием третьей дозы вакцины против коклюша, дифтерии и столбняка, и лечение острых респираторных инфекций у детей в возрасте до 5 лет.

Вывод

Вклад неравенства, связанного с материальным благосостоянием, в показатель разрыва в охвате медико-санитарными услугами по охране здоровья матери и ребенка различается в зависимости от страны и вида медико-санитарной услуги, что требует применения конкретных мер вмешательства. Адресные политические меры наиболее применимы в тех случаях, когда имеет место высокий уровень связанного с материальным благосостоянием внутристранового неравенства, а популяционные подходы – когда разрыв в охвате медико-санитарными услугами значителен во всех квинтилях.

摘要

目的

旨在衡量撒哈拉以南非洲地区妇幼保健指标的医疗服务覆盖缺口中国家内部与财富相关的不平等现象,并量化该不平等现象对国民医疗服务覆盖缺口的影响。

方法

撒哈拉以南28个非洲国家的妇幼保健服务覆盖情况的数据从2000-2008年间的“人口健康调查”获得。对于每个国家,国民医疗服务覆盖缺口确定为整体医疗服务覆盖指数和选定的个别医疗服务指标。然后分析数据得出最富有的五分位组的覆盖缺口(即缺乏所要求的医疗服务的五分位组的比例)和人口归因危险度(国家内部与财富相关的不平等的绝对度量)。

结果

26个国家中,国家内部与财富相关的不平等占国民整体覆盖缺口的25%以上。依各国情况而定,减少这种不平等可降低16%-56%的覆盖缺口。就选定的个别医疗服务指标而言,与财富相关的不平等现象在熟练接生和产前护理等服务方面更加普遍,而在计划生育、麻疹疫苗接种、接受三联预防白喉、百日咳和破伤风疫苗和5岁以下儿童急性呼吸道感染治疗方面则不那么普遍。

结论

与财富相关的不平等现象对妇幼保健服务覆盖缺口的作用还受国家和医疗服务类型的影响,因而有必要根据具体情况采取特定干预措施。针对性政策在国家内部与财富相关的不平等水平相对高的国家尤为适用,而全人群方法则对所有五分位组中医疗服务覆盖缺口高的国家都适用。

Introduction

Established in 2000, the eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) represent a global commitment to eliminating poverty. MDG 4 and MDG 5 are devoted to child and maternal health, with 2015 targets of a two-thirds reduction in the 1990 mortality rate for children under 5 years of age, a three-quarters reduction in the 1990 maternal mortality rate and universal access to reproductive health services.1,2

Although some promising gains have been made worldwide, in 2008, about 358 000 mothers3 and 8.8 million children under 5 years of age4 lost their lives, many from preventable or treatable causes.3–5

The African Region of the World Health Organization (WHO) is falling behind on MDG child and maternal health targets. In many countries these are advancing too slowly, stagnating or deteriorating.1,3–9 Between 1990 and 2008, the worldwide mortality rate for children under 5 years of age dropped by 27%;8 however, in 2008 more than half of these deaths occurred in sub-Saharan Africa.5,8 The maternal mortality ratio in the African Region is 900 maternal deaths per 100 000 live births – at least double that of any other WHO region.8 Access to services such as antenatal care and skilled birth attendance in the African Region are among the lowest in the world.1,3–6,8

Improving child and maternal health requires health systems to be strengthened through both long-range investments (e.g. development of health facility infrastructure and programmes to train health workers) and initiatives that can be rapidly deployed (e.g. community immunization days, vitamin A campaigns and distribution of insecticide-treated bednets).4,10,11 In 2010, the Countdown to 2015 decade report made a special appeal for improving the child and maternal health situation in sub-Saharan Africa, calling for renewed and accelerated political and financial commitment to MDG 4 and MDG 5 in this region.4

Achieving the child and maternal health MDGs will require policy and programme planners to identify and reach those who are most in need of health services.2,5,9 To maximize and improve progress towards the MDG targets in Africa, it is important to have strong national and regional monitoring systems12 that can identify which populations are benefiting from programmes and initiatives, and which are not.13 Progress on MDG 4 and MDG 5 has been variable across sub-Saharan African countries; also, national indicators may mask inequalities between subgroups of the population, 4,6,8 and improvements at a country level may occur alongside a widening inequality gap.14 Addressing inequalities and their root causes is an important step towards improving health outcomes.5

Measurements of service coverage capture both provision and use of services and interventions, since they express the percentage of people receiving a specified service or intervention among those requiring that service.13 The health service coverage gap represents an estimate of the increase in coverage needed to achieve universal coverage for a given service.15 The ability of a programme or initiative to reduce the health service coverage gap is an important indicator of success; comparing the gap across populations can help to target action to reduce disparities.13,15

Previous monitoring of health service coverage and the health service coverage gap for several child and maternal health services revealed between-country inequality and varying patterns of within-country wealth-related inequality.15,16 Further delineation of the coverage gap within countries is needed to more accurately define the current reach of child and maternal health services and to inform programme and policy direction.17–19 Thus, our objective was to measure the magnitude of within-country wealth-related inequality in the health service coverage gap of maternal and child health indicators and to quantify the contribution of this inequality to the national coverage gap within sub-Saharan African countries.

Methods

Coverage data for child and maternal health services were obtained from the 28 sub-Saharan African countries that participated in the Demographic Health Survey (DHS) between 2000 and 2008.4 This sample included 13 of the 15 African countries with the highest number of neonatal deaths.9 The DHS is a large-scale, nationally representative survey that conducts standardized face-to-face interviews with women aged 15–49 years.20 Where countries had multiple DHS data sets for the 2000–2008 period, we selected the most recent set for analysis.

We used an index of several health services to display an overview of the child and maternal health service coverage gap within each study country. The index – referred to as the overall coverage gap – captured the coverage gap in four areas of intervention with different delivery strategies: maternal and neonatal care, immunization, treatment of sick children and family planning. Each of the four interventional areas comprised a small number of indicators for which reliable long-term and comparable data were available. The validity of the index has been discussed previously; it performed well in comparison to several alternative measures.13 To further illustrate select components of each of the four areas of intervention included in the index, we calculated coverage gaps separately for the following health service indicators: skilled birth attendance; one or more antenatal care visits; measles immunization; receipt of a third dose of vaccine against diphtheria, pertussis and tetanus (DPT3); treatment of acute respiratory infection in children under 5 years of age; and family planning. These interventions represent diverse types of child and maternal health services and interventions, and are associated with a range of aspects of health system delivery.13

For each country, the national coverage gaps were calculated and additively broken down into two parts: the coverage gap in the wealthiest quintile (i.e. the proportion of this quintile that did not receive a required health service) and the population attributable risk (an absolute measure of within-country wealth-related inequality that summarizes the differences between the richest quintile and each of the four other wealth quintiles). Thus, population attributable risk, PAR, shows the improvement possible if the total population had the same health service coverage as the wealthiest quintile. PAR can be expressed as follows:

| PAR = CGpop − CGref |

where CGpop is the average coverage gap across all wealth quintiles (the population), representing the national coverage gap, and CGref is the coverage gap in the wealthiest quintile (the reference group).18,21,22 The relative version of population attributable risk – population attributable risk percentage – is calculated by dividing population attributable risk by the national coverage gap. It indicates the proportional reduction in national coverage gap that would be achieved if the total population had the same health service coverage gap as the wealthiest quintile.

Results

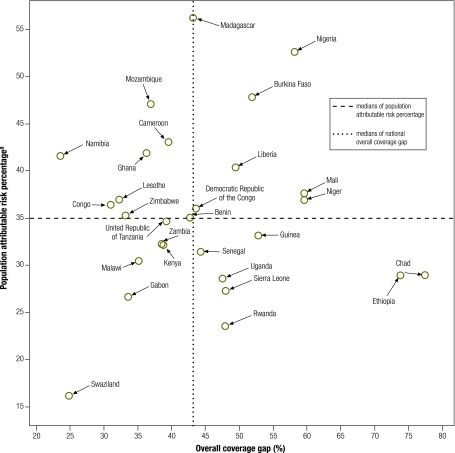

The national overall coverage gap ranged from 24% (Namibia) to 77% (Chad), with a median of 43% (Fig. 1). In 26 of the 28 countries, within-country wealth-related inequality constituted at least one quarter of the national overall coverage gap (Table 1). In four countries – Burkina Faso, Madagascar, Mozambique and Nigeria – within-country wealth-related inequality accounted for about 50% of the national overall coverage gap. The lowering of wealth-related inequality had the potential to decrease the national overall coverage gap by levels of between 16% (Swaziland) and 56% (Madagascar).

Fig. 1.

National overall health service coverage gap versus within-country relative inequality in 28 sub-Saharan African countries, 2000–2008

a Relative inequality, calculated by dividing population attributable risk by the national health service coverage gap.

Table 1. Overall health service coverage gap – national average versus within-country inequality in 28 sub-Saharan African countries, 2000–2008.

| Country | Year | Coverage gap (%) |

PARa (percentage points) | PAR%b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National | In richest quintile | ||||

| Benin | 2006 | 43 | 28 | 15 | 35 |

| Burkina Faso | 2003 | 52 | 27 | 25 | 48 |

| Cameroon | 2004 | 39 | 22 | 17 | 43 |

| Chad | 2004 | 77 | 55 | 22 | 29 |

| Congo | 2005 | 31 | 20 | 11 | 36 |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 2007 | 44 | 28 | 16 | 36 |

| Ethiopia | 2005 | 74 | 52 | 21 | 29 |

| Gabon | 2000 | 34 | 25 | 9 | 27 |

| Ghana | 2008 | 36 | 21 | 15 | 42 |

| Guinea | 2005 | 53 | 35 | 17 | 33 |

| Kenya | 2003 | 39 | 26 | 12 | 32 |

| Lesotho | 2004 | 32 | 20 | 12 | 37 |

| Liberia | 2007 | 49 | 30 | 20 | 40 |

| Madagascar | 2003–2004 | 43 | 19 | 24 | 56 |

| Malawi | 2004 | 35 | 24 | 11 | 30 |

| Mali | 2006 | 60 | 37 | 22 | 38 |

| Mozambique | 2003 | 37 | 19 | 17 | 47 |

| Namibia | 2006–2007 | 24 | 14 | 10 | 42 |

| Niger | 2006 | 60 | 38 | 22 | 37 |

| Nigeria | 2008 | 58 | 28 | 31 | 53 |

| Rwanda | 2005 | 48 | 37 | 11 | 24 |

| Senegal | 2005 | 44 | 30 | 14 | 31 |

| Sierra Leone | 2008 | 48 | 35 | 13 | 27 |

| Swaziland | 2006–2007 | 25 | 21 | 4 | 16 |

| United Republic of Tanzania | 2004–2005 | 39 | 26 | 14 | 35 |

| Uganda | 2006 | 48 | 34 | 14 | 29 |

| Zambia | 2007 | 39 | 26 | 12 | 32 |

| Zimbabwe | 2005–2006 | 33 | 22 | 12 | 35 |

| Median | 2000–2008 | 43 | 27 | 14 | 35 |

| 95% CI of the median | 2000–2008 | 37–48 | 23–30 | 12–17 | 32–37 |

CI, confidence interval; PAR, population attributable risk.

a Absolute inequality.

b Relative inequality, calculated by dividing population attributable risk by the national health service coverage gap.

Note: Figures may be affected by rounding.

Fig. 1 demonstrates the national overall coverage gap against the wealth-related relative inequality in overall coverage gap observed within each of the 28 study countries. There was no relation between the two parameters (ρ: 0.03; P-value: 0.88).

The relationship between wealth and coverage gaps for specific indicators varied, depending on the type of health service. Breakdown of the national health service-specific coverage gaps revealed that within-country wealth-related inequality was particularly important for some components of the overall coverage gap (e.g. skilled birth attendance and one or more antenatal care visits) (Table 2). The coverage gap in skilled birth attendance generally showed a high proportion of within-country wealth-related inequality. Depending on the country, the coverage gap in skilled birth attendance could be reduced by 22% to 93% if no wealth-related inequality existed. For 25 of the 28 countries in the study, eliminating the wealth-related inequality would at least halve the coverage gap for skilled birth attendance. Similarly, within-country wealth-related inequality in one or more antenatal care visits accounted for at least 50% of the coverage gap in 21 countries.

Table 2. Health service coverage gap of skilled birth attendance and one or more antenatal care visits – national average versus within-country inequality in 28 sub-Saharan African countries, 2000–2008.

| Country | Skilled birth attendance |

One or more antenatal care visits |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coverage gap (%) |

PARa (percentage points) | PAR%b | Coverage gap (%) |

PARa (percentage points) | PAR%b | ||||

| National | In richest quintile | National | In richest quintile | ||||||

| Benin | 22 | 2 | 20 | 90 | 12 | 1 | 11 | 92 | |

| Burkina Faso | 62 | 16 | 47 | 75 | 27 | 4 | 23 | 85 | |

| Cameroon | 38 | 5 | 33 | 86 | 17 | 3 | 14 | 82 | |

| Chad | 84 | 49 | 35 | 42 | 58 | 23 | 35 | 60 | |

| Congo | 16 | 2 | 14 | 88 | 13 | 2 | 11 | 85 | |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 25 | 2 | 23 | 93 | 14 | 4 | 10 | 72 | |

| Ethiopia | 94 | 73 | 21 | 22 | 72 | 42 | 30 | 42 | |

| Gabon | 13 | 3 | 10 | 80 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 55 | |

| Ghana | 41 | 5 | 36 | 87 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 100 | |

| Guinea | 62 | 12 | 50 | 80 | 19 | 2 | 17 | 89 | |

| Kenya | 58 | 25 | 34 | 58 | 12 | 6 | 6 | 49 | |

| Lesotho | 44 | 16 | 28 | 64 | 10 | 4 | 6 | 58 | |

| Liberia | 53 | 18 | 35 | 67 | 20 | 4 | 16 | 80 | |

| Madagascar | 54 | 8 | 46 | 85 | 20 | 3 | 17 | 85 | |

| Malawi | 43 | 15 | 27 | 64 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 56 | |

| Mali | 73 | 24 | 49 | 67 | 63 | 20 | 43 | 68 | |

| Mozambique | 52 | 11 | 41 | 79 | 15 | 1 | 14 | 94 | |

| Namibia | 18 | 2 | 16 | 88 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 40 | |

| Niger | 82 | 41 | 42 | 51 | 54 | 17 | 37 | 68 | |

| Nigeria | 61 | 14 | 47 | 77 | 45 | 6 | 39 | 87 | |

| Rwanda | 71 | 40 | 31 | 43 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 12 | |

| Senegal | 48 | 10 | 37 | 78 | 12 | 2 | 10 | 84 | |

| Sierra Leone | 58 | 29 | 29 | 50 | 13 | 3 | 10 | 77 | |

| Swaziland | 26 | 8 | 18 | 70 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 65 | |

| United Republic of Tanzania | 54 | 13 | 41 | 76 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 47 | |

| Uganda | 57 | 23 | 35 | 60 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 49 | |

| Zambia | 53 | 8 | 45 | 84 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 84 | |

| Zimbabwe | 31 | 5 | 27 | 85 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 47 | |

| Median | 53 | 13 | 34 | 76 | 13 | 3 | 10 | 70 | |

| 95% CI of the median | 42–58 | 8–17 | 28–40 | 65–83 | 6–18 | 2–4 | 5–16 | 57–84 | |

CI, confidence interval; PAR, population attributable risk.

a Absolute inequality.

b Relative inequality, calculated by dividing population attributable risk by the national health service coverage gap.

Note: Figures may be affected by rounding.

For some health services, the role of within-country wealth-related inequality was less pronounced. For example, such inequality accounted for a smaller proportion of the national coverage gap in measles immunization, DPT3, care seeking for suspected pneumonia, and family planning (Table 3), with some notable variations. The national DPT3 coverage gap was 64% in both Nigeria and the United Republic of Tanzania; however, within-country inequality accounted for only 3% of the coverage gap in the United Republic of Tanzania but 63% of the gap in Nigeria. Both Cameroon and Zimbabwe had a 34% national coverage gap in measles immunization but differed widely in terms of within-country inequality contribution to the national coverage gap (53% in Cameroon and 24% in Zimbabwe).

Table 3. Health service coverage gap for measles immunization, DPT3 immunization, treatment of acute respiratory infection in children under 5 years of age and family planning services, national average versus within-country inequality in 28 sub-Saharan African countries, 2000–2008.

| Country | Measles immunization |

DPT3 immunization |

Treatment of acute respiratory infection in children under 5 years of age |

Family planning services |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coverage gap (%) |

PARa (percentage points) | PAR%b | Coverage gap (%) |

PARa (percentage points) | PAR%b | Coverage gap (%) |

PARa (percentage points) | PAR%b | Coverage gap (%) |

PARa (percentage points) | PAR%b | ||||||||

| National | In richest quintile | National | In richest quintile | National | In richest quintile | National | In richest quintile | ||||||||||||

| Benin | 38 | 23 | 15 | 40 | 33 | 13 | 20 | 60 | 64 | 52 | 13 | 20 | 64 | 44 | 20 | 31 | |||

| Burkina Faso | 43 | 29 | 15 | 34 | 43 | 28 | 15 | 35 | 64 | 27 | 37 | 58 | 68 | 41 | 27 | 40 | |||

| Cameroon | 34 | 16 | 18 | 53 | 34 | 21 | 13 | 38 | 59 | 48 | 12 | 20 | 44 | 26 | 18 | 40 | |||

| Chad | 77 | 61 | 16 | 21 | 80 | 58 | 22 | 27 | 80 | 61 | 19 | 24 | 88 | 70 | 18 | 20 | |||

| Congo | 33 | 15 | 18 | 55 | 31 | 9 | 22 | 70 | 53 | 43 | 10 | 19 | 27 | 20 | 7 | 27 | |||

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 36 | 14 | 22 | 62 | 54 | 26 | 28 | 51 | 58 | 46 | 12 | 21 | 54 | 38 | 16 | 30 | |||

| Ethiopia | 63 | 46 | 17 | 27 | 68 | 51 | 16 | 24 | 81 | 67 | 14 | 18 | 69 | 39 | 30 | 44 | |||

| Gabon | 44 | 27 | 18 | 40 | 64 | 50 | 14 | 22 | 39 | 32 | 7 | 17 | 46 | 35 | 11 | 25 | |||

| Ghana | 10 | 5 | 5 | 46 | 11 | 7 | 4 | 40 | 51 | 24 | 27 | 54 | 60 | 44 | 17 | 28 | |||

| Guinea | 48 | 39 | 9 | 19 | 48 | 37 | 12 | 24 | 57 | 39 | 18 | 31 | 70 | 57 | 13 | 18 | |||

| Kenya | 27 | 12 | 15 | 56 | 27 | 27 | 1 | 3 | 51 | 36 | 15 | 29 | 37 | 24 | 13 | 35 | |||

| Lesotho | 15 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 10 | 7 | 41 | 40 | 27 | 13 | 33 | 45 | 26 | 19 | 42 | |||

| Liberia | 36 | 13 | 24 | 65 | 49 | 26 | 23 | 47 | 40 | 12 | 28 | 69 | 76 | 61 | 15 | 20 | |||

| Madagascar | 41 | 16 | 25 | 61 | 38 | 9 | 29 | 76 | 52 | 34 | 18 | 35 | 47 | 25 | 22 | 47 | |||

| Malawi | 21 | 12 | 9 | 43 | 18 | 10 | 8 | 45 | 63 | 54 | 9 | 14 | 45 | 34 | 11 | 24 | |||

| Mali | 30 | 20 | 10 | 33 | 31 | 21 | 10 | 32 | 62 | 40 | 22 | 36 | 79 | 64 | 15 | 19 | |||

| Mozambique | 23 | 4 | 20 | 84 | 28 | 3 | 25 | 88 | 45 | 38 | 7 | 16 | 42 | 31 | 11 | 26 | |||

| Namibia | 15 | 5 | 11 | 70 | 16 | 6 | 10 | 64 | 33 | 17 | 16 | 50 | 27 | 13 | 14 | 51 | |||

| Niger | 52 | 26 | 26 | 51 | 60 | 37 | 23 | 38 | 53 | 34 | 19 | 36 | 58 | 50 | 9 | 15 | |||

| Nigeria | 58 | 25 | 33 | 58 | 64 | 24 | 40 | 63 | 50 | 31 | 19 | 38 | 58 | 34 | 24 | 41 | |||

| Rwanda | 14 | 12 | 2 | 16 | 12 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 72 | 56 | 16 | 22 | 69 | 52 | 17 | 25 | |||

| Senegal | 26 | 19 | 7 | 28 | 21 | 16 | 6 | 28 | 53 | 39 | 14 | 26 | 73 | 54 | 19 | 26 | |||

| Sierra Leone | 39 | 32 | 8 | 20 | 39 | 27 | 11 | 29 | 49 | 45 | 4 | 8 | 77 | 57 | 20 | 26 | |||

| Swaziland | 8 | 7 | 1 | 14 | 8 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 43 | 41 | 2 | 4 | 32 | 22 | 10 | 33 | |||

| United Republic of Tanzania | 20 | 9 | 11 | 54 | 64 | 62 | 2 | 3 | 40 | 33 | 7 | 19 | 44 | 25 | 19 | 44 | |||

| Uganda | 32 | 27 | 5 | 16 | 83 | 81 | 3 | 3 | 26 | 19 | 8 | 29 | 63 | 36 | 28 | 44 | |||

| Zambia | 15 | 6 | 10 | 63 | 79 | 69 | 10 | 13 | 35 | 39 | 0 | 0 | 39 | 26 | 13 | 34 | |||

| Zimbabwe | 34 | 26 | 8 | 24 | 38 | 31 | 7 | 18 | 74 | 52 | 22 | 30 | 17 | 10 | 8 | 45 | |||

| Median | 33 | 16 | 13 | 42 | 38 | 25 | 11 | 33 | 52 | 39 | 14 | 25 | 56 | 35 | 16 | 30 | |||

| 95% CI of the median | 24–39 | 12–25 | 9–18 | 27–55 | 29–52 | 12–30 | 7–19 | 24–44 | 46–59 | 33–45 | 10–18 | 19–33 | 44–67 | 26–44 | 13–19 | 26–40 | |||

CI, confidence interval; DPT3, three doses of vaccine against diphtheria, pertussis and tetanus; PAR, population attributable risk.

a Absolute inequality.

b Relative inequality, calculated by dividing population attributable risk by the national health service coverage gap.

Note: Figures may be affected by rounding.

The 28 countries had different magnitudes and patterns of wealth-related inequality. Ethiopia had one of the highest coverage gaps for every indicator in the study, yet the contribution of within-country inequality tended to be proportionally low. Nigeria had high within-country wealth-related relative inequality for many indicators. In many other countries the situation was mixed. For example, in Mali, within-country wealth-related inequality constituted at least two thirds of the national coverage gap in both skilled birth attendance and one or more antenatal care visits, but only about one third of the national coverage gap in measles immunization.

Discussion

This study of 28 sub-Saharan African countries concurs with other reports in finding that health services in developing countries are not equally accessible to all populations.4,9,12,14,18,23–25 By breaking down the health service coverage gap, we showed that the role of wealth-related inequality differs between countries and types of health service. Even within the same region, countries experience many unique factors that affect health service coverage both directly and indirectly, ranging from health-care financing priorities and political agendas to cultural practices and conflict situations.12,24

Health services require variable amounts of funding, resources and infrastructure, and this may account for some of the differences in the role of wealth-related inequality.4,23 In line with other studies, we found that within-country wealth-related inequality contributed less to the services delivered at the community level (e.g. family planning and immunizations) than to services that require trained health professionals or health facilities (e.g. one or more antenatal care visits and skilled birth attendance).4 An understanding of the complexity and magnitude of wealth-related inequality will improve interventions that aim to increase the coverage of child and maternal health services in developing countries.

Planning interventions

Planning interventions that take into account wealth-related inequality may play a significant role in reducing the health service coverage gap. Where the contribution of within-country wealth-related inequality is high, an approach targeted at populations in lower wealth quintiles is justified. This type of approach would be appropriate in countries such as Madagascar and Nigeria, where the relative inequality (PAR%) is high. The use of poverty maps and the prioritization of poor, remote communities in the design of health service delivery have helped countries such as Bangladesh, Brazil and Peru to tackle health service coverage inequality.26,27

In many of the study countries, a targeted approach may be appropriate for interventions in skilled birth attendance or one or more antenatal care visits. Such an approach could include providing free or reduced-fee health services to those in lower wealth quintiles, creating incentives for health workers to practice in underserved communities, offering skill development sessions to build the capacity of health-care providers serving poor communities, or establishing conditional cash-transfer programmes that pay mothers for using services.18 Task-shifting – the deployment of community health workers outside of health facilities – is another low-cost way to increase access to basic health services.14,28

A whole-population approach may work well in situations in which the national coverage gap is high, as is the case for Chad and Ethiopia. Given the widespread coverage gap in all quintiles (including the richest), there is great potential for these countries to benefit from a whole-population approach. In situations where the health system can reach the entire population, this type of approach can provide health-care services with consistent quality and benefit.13 Certain types of health services, such as immunization campaigns and family planning initiatives, may be best delivered using a whole-population approach. The main risk with this approach is that if implementation ends up being partial, inequalities may be exacerbated; that is, the rich may benefit early in the programme and, if the programme is interrupted (e.g. for lack of funds), the poor are yet to be reached.29

In some situations, a combination of targeted and whole-population approaches may help to decrease the health service coverage gap. Mali, for example, may benefit from a targeted approach for skilled birth attendance and one or more antenatal care visits, and from a whole-population approach to reduce the coverage gap in measles immunization. In Nigeria, action to increase coverage of DPT3 may benefit from a strong targeted approach, whereas in the United Republic of Tanzania, a whole-population approach may be more appropriate. Box 1 provides examples of countries adopting different approaches.

Box 1. Country examples of interventions to reduce the health service coverage gap.

A. In Kenya, the Kisumu Medical and Educational Trust programme (KMET), based in the city of Kisumu, aims to increase access to reproductive health services by the poor.30 KMET is strengthening the capacity of health-care providers and facilities in poor, rural areas by providing training sessions, basic equipment and small loans. Taking a targeted approach, the programme has been successful in reaching the poorest populations by enrolling mid-level health-care providers (e.g. nurses and clinical officers) in rural areas.

B. In Ghana, the distribution of insecticide-treated bednets (ITNs) was paired with whole-population measles immunization campaigns.31 Before the campaign, ITN ownership in the Lawra district of Ghana was less than 10% in all wealth quintiles. After the campaign, the coverage rate of ITN ownership increased to over 90% in all wealth quintiles. This community-level intervention was a cost-efficient method of distributing ITNs to a large population.

C. Brazil is on track to achieving MDG 4 and has made good progress towards MDG 5 thanks to a combination of whole-population and targeted approaches to increasing health coverage.32 A unified health system provides comprehensive health care at the whole-population level. Targeted approaches include the Family Health Strategy, which reorganized primary health care by sending teams of health workers to underserved areas. Since its inception, the programme has been scaled up to reach over 50% of the population, and has contributed to declining infant mortality rates.

D. In Egypt, an immunization campaign contained elements of both whole-population and targeted approaches.25 The campaign achieved widespread geographical coverage, with financial and training support from the central government. Health units used disaggregated data to target resources to populations with lower coverage, and non-physician health workers were empowered to assume greater responsibilities.

Limitations and extension

The overall coverage gap was used to obtain a summary measure of coverage gap for a set of maternal and child interventions with different delivery strategies, based on a set of robust indicators. Although there may be correlations between the variables that are used in the index, this does not obviate the need for a cross-cutting coverage measure. By using four intervention areas with different delivery strategies, we obtained a broad index of service delivery. For example, although there was a moderate correlation between the treatment of acute respiratory infection in children under 5 years of age and measles vaccination coverage (ρ: 0.48), no correlation was seen between the former indicator and DPT3 vaccination coverage (ρ: −0.04).

The population attributable risk calculation of wealth-related inequality assumed that the wealthiest quintile (the reference population) experienced the lowest coverage gap. In a few instances in our study this was not the case; the health-service-specific coverage gap of the wealthiest quintile was reported to be higher than that of at least one of the other quintiles. For example, the coverage gap of specific health interventions in the richest wealth quintile was slightly higher (0.1–3.6%) than the national coverage gap for the treatment of acute respiratory infections in children under 5 years of age (Zambia), DPT3 immunization (Rwanda and Swaziland) and measles immunization (Lesotho). This was not the case with the overall coverage gap. A possible explanation could be that the sample size of the population at risk in the wealthiest quintile (denominator) is too small to generate a meaningful representation of the coverage gap of a specialized service. For instance, the wealthiest quintile of some countries had only a small number of sick children requiring treatment for acute respiratory infection. Alternatively, data may reflect an unknown and consistent pattern of under- or over-reporting during survey interviews. It is also possible that the data reflect the true situation and that the richest quintile did not experience the lowest health service coverage gap.

Reporting bias tends to attenuate the association between wealth quintile and coverage rates. Although over-reporting of child morbidity in the wealthier quintiles is documented,33 the extent to which it affects the reporting of health service use is less clear.

We defined inequality based on asset-determined wealth quintiles – a common tool for measuring disparity within populations.34 This frame of reference, however, presents certain limitations.13,35,36 The assets chosen to represent wealth must be culturally specific, timely and applicable to all members of a specified population. Wealth quintiles represent only relative wealth differences and may align closely with other forms of disparity (e.g. urban or rural). In certain contexts, other factors (e.g. education, gender or geography) may be more important in determining disparity in health service access.19,35

While breakdown of the coverage gap may be a useful tool to assess the role of within-country inequality, the strength of the measurement relies on the accuracy and availability of data. The lack of high-quality statistical data from developing countries presents challenges for the creation of informed policies,17,18,37 a limitation that is exacerbated when attempting inter-country comparisons.21 By focusing on within-country comparisons, this data analysis reduced the importance of attaining regionally consistent data. As the quality of data and methods of analysis and monitoring improve, African countries will be better able to use this information to improve health service initiatives.6,12 Because coverage gap served as a proxy for health service provision and use, alternative analyses might segregate these components or expand them to include other types of service indicators.

Our methods may easily be used to break down the health service coverage gap by other forms of inequality, such as education, gender or geography. Population attributable risk takes into account both the situation of all social groups (not only the extremes) and the group population size. Hence, it overcomes the limitations of simple range measures of inequality such as differences or ratios. This study focused on wealth-related inequality in sub-Saharan African countries at a recent time point and did not explore trends in health equity situations; the latter may provide more in-depth evidence for equity-focused interventions. In future studies, our methods could be useful for monitoring inequalities over time and assessing the impact of interventions on reducing inequality.

Conclusion

Overall, a comprehensive monitoring programme may help countries to identify relevant forms of inequality and allow for health service initiatives to be targeted accordingly, where appropriate.19,25,38,39 Coverage gap data were presented for select components of the overall coverage gap (one or more antenatal care visits and skilled birth attendance, measles and DPT3 immunization, treatment of acute respiratory infection in children under 5 years of age and family planning); these components correspond to diverse types of child and maternal health indicators. This allowed for within-country comparison, highlighting the variable role of wealth-related inequality within the national coverage gap.

Given the lack of association between the level of national overall coverage gap and the magnitude of relative inequality, policies and programmes that aim to reduce the service coverage gap may not necessarily be effective in tackling within-country inequalities. This finding also reinforces the notion that the determinants of health are not necessarily the same as the determinants of inequalities in health.40

Between 1990 and 2006, patterns of inequality in developing countries remained largely unchanged.13 This trend has been cited as a major contributor to the lack of progress on the child and maternal health MDGs.1,13,35,37,41 Our study demonstrated the contribution of wealth-related inequality to child and maternal health service coverage gap in 28 sub-Saharan African countries and highlighted the implications for health policy approaches. As the deadline for the MDGs approaches, attention is increasingly turning to child and maternal health. Now, more than ever, is the time for strong policies and for interventions that will maximize their impact.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Millennium Development Goals report 2010 New York: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs; 2010.

- 2.United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki-moon. Global strategy for women's and children's health New York: United Nations; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2008 Geneva: World Health Organization, United Nations Children's Fund, United Nations Population Fund & The World Bank; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Countdown to 2015 Group. Countdown to 2015 decade report (2000–2010): taking stock of maternal, newborn and child survival New York: World Health Organization & United Nations Children’s Fund; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Progress for children: achieving the MDGs with equity New York: United Nations Children's Fund; 2010.

- 6.The health of the people: the African regional health report Brazzaville: World Health Organization, Regional Office for Africa; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Millennium Development Goals. 2010 progress chart. New York: United Nations Statistics Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations; 2010. Available from: http://mdgs.un.org/unsd/mdg/Resources/Static/Products/Progress2010/MDG_Report_2010_Progress_Chart_En.pdf [accessed 25 August 2011]. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World health statistics 2010 Geneva: World Health Organization, Department of Health Statistics and Informatics; 2010. Available from: http://www.who.int/whosis/whostat/EN_WHS10_Full.pdf [accessed 25 August 2011].

- 9.Opportunities for Africa's newborns: practical data, policy and programmatic support for newborn care in Africa Geneva: World Health Organization on behalf of The Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health; 2006. Available from: http://www.who.int/pmnch/media/publications/oanfullreport.pdf [accessed 25 August 2011].

- 10.Monitoring of the achievement of the health-related Millennium Development Goals: report by the Secretariat (WHA A62/10). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. Available from: http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/A62/A62_10-en.pdf [accessed 25 August 2011].

- 11.Fawzi H. Maternal mortality reduction: What is the evidence? Sudan J Public Health. 2006;1:309–14. [Google Scholar]

- 12.MDG Africa Steering Group. Achieving the millennium development goals in Africa: recommenations of the MDG Africa Steering Group, June 2008 New York: United Nations Department of Public Information; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boerma JT, Bryce J, Kinfu Y, Axelson H, Victora CG, Countdown 2008 Equity Analysis Group Mind the gap: equity and trends in coverage of maternal, newborn, and child health services in 54 Countdown countries. Lancet. 2008;371:1259–67. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60560-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Narrowing the gaps to meet the goals New York: United Nations Children’s Fund; 2010. Available from: http://www.unicef.pt/docs/Narrowing_the_Gaps_to_Meet_the_Goals_090310_2a.pdf [accessed 25 August 2011].

- 15.Bhutta ZA, Chopra M, Axelson H, Berman P, Boerma T, Bryce J, et al. Countdown to 2015 decade report (2000-10): taking stock of maternal, newborn, and child survival. Lancet. 2010;375:2032–44. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60678-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Victora CG, Fenn B, Bryce J, Kirkwood BR. Co-coverage of preventive interventions and implications for child-survival strategies: evidence from national surveys. Lancet. 2005;366:1460–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67599-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barros F, Victora C, Scherpbier R, Gwatkin D. Health and nutrition of children: equity and social determinants. In: Blas E, Kurup A, editors. Equity, social determinants and public health programmes Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. pp. 49-76. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Victora CG, Wagstaff A, Schellenberg JA, Gwatkin D, Claeson M, Habicht JP. Applying an equity lens to child health and mortality: more of the same is not enough. Lancet. 2003;362:233–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13917-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mulholland E, Smith L, Carneiro I, Becher H, Lehmann D. Equity and child-survival strategies. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:399–407. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.044545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Demographic and Health Surveys [Internet]. Calverton: MACRO International; 2010. Available from: http://www.measuredhs.com/ [accessed 25 August 2011]

- 21.Mackenbach JP, Kunst AE. Measuring the magnitude of socio-economic inequalities in health: an overview of available measures illustrated with two examples from Europe. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:757–71. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harper S, Lynch J. Measuring inequalities in health. In: Oakes J, Kaufman J, editors. Methods in social epidemiology San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gwatkin DR, Bhuiya A, Victora CG. Making health systems more equitable. Lancet. 2004;364:1273–80. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17145-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marmot M. Achieving health equity: from root causes to fair outcomes. Lancet. 2007;370:1153–63. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61385-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delamonica E, Minujin A, Gulaid J. Monitoring equity in immunization coverage. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:384–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barros AJ, Victora CG, Cesar JA, Neumann NA, Bertoldi AD. Brazil: are health and nutrition programs reaching the neediest? In: Gwatkin D, Wagstaff A, Yazbeck A, editors. Reaching the poor: with health, nutrition, and population services: what works, what doesn't, and why? Washington: The World Bank; 2005. pp. 281-306. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ministerial Resolution 307-2005/MINS. Lima: Ministry of Health, Peru; 2005. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lim SS, Dandona L, Hoisington JA, James SL, Hogan MC, Gakidou E. India's Janani Suraksha Yojana, a conditional cash transfer programme to increase births in health facilities: an impact evaluation. Lancet. 2010;375:2009–23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60744-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gwatkin DR, Ergo A. Universal health coverage: friend or foe of health equity? Lancet. 2011;377:2160–1. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montagu D, Prata N, Campbell M, Walsh J, Orero S. Kenya: reaching the poor through the private sector — a network model for expanding access to reproductive health services. In: Gwatkin D, Wagstaff A, Yazbeck A, editors. Reaching the poor with health, nutrition, and population services: what works, what doesn't, and why Washington: The World Bank; 2005. pp. 81-96. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grabowsky M, Farrell N. Chimumbwa J, Nobiya T, Wolkon A, Selanikio J. Ghana and Zambia: achieving equity in the distribution of insecticide-treated bednets through links with measles vaccination campaigns. In: Gwatkin D, Wagstaff A, Yazbeck A, editors. Reaching the poor with health, nutrition, and population services: what works, what doesn't, and why Washington: The World Bank; 2005. pp. 65-80. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barros FC, Matijasevich A, Requejo JH, Giugliani E, Maranhão AG, Monteiro CA, et al. Recent trends in maternal, newborn, and child health in Brazil: progress toward Millennium Development Goals 4 and 5. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1877–89. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.196816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manesh AO, Sheldon TA, Pickett KE, Carr-Hill R. Accuracy of child morbidity data in demographic and health surveys. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37:194–200. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rutstein SO, Johnson K. The DHS wealth Index (DHS Comparative Reports No. 6). Calverton: ORC Macro; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Waage J, Banerji R, Campbell O, Chirwa E, Collender G, Dieltiens V, et al. The Millennium Development Goals: a cross-sectoral analysis and principles for goal setting after 2015. Lancet. 2010;376:991–1023. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61196-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sahn D, Stifel D. Poverty comparisons over time and across countries in Africa. World Dev. 2000;28:2123–55. doi: 10.1016/S0305-750X(00)00075-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Monitoring and evaluation of health systems strengthening: an operational framework Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Braveman P, Starfield B, Geiger HJ. World Health Report 2000: how it removes equity from the agenda for public health monitoring and policy. BMJ. 2001;323:678–81. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7314.678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wirth M, Sacks E, Delamonica E, Storeygard A, Minujin A, Balk D. “Delivering” on the MDGs?: equity and maternal health in Ghana, Ethiopia and Kenya. East Afr J Public Health. 2008;5:133–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Graham H, Kelly M. Health inequalities: concepts, frameworks and policy London: NHS Health Development Agency; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Equity as a shared vision for health and development. Lancet. 2010;376:929. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61431-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]