Abstract

Objective

To determine whether the Mexico City Policy, a United States government policy that prohibits funding to nongovernmental organizations performing or promoting abortion, was associated with the induced abortion rate in sub-Saharan Africa.

Methods

Women in 20 African countries who had induced abortions between 1994 and 2008 were identified in Demographic and Health Surveys. A country’s exposure to the Mexico City Policy was considered high (or low) if its per capita assistance from the United States for family planning and reproductive health was above (or below) the median among study countries before the policy’s reinstatement in 2001. Using logistic regression and a difference-in-difference design, the authors estimated the differential change in the odds of having an induced abortion among women in high exposure countries relative to low exposure countries when the policy was reinstated.

Findings

The study included 261 116 women aged 15 to 44 years. A comparison of 1994–2000 with 2001–2008 revealed an adjusted odds ratio for induced abortion of 2.55 for high-exposure countries versus low-exposure countries under the policy (95% confidence interval, CI: 1.76–3.71). There was a relative decline in the use of modern contraceptives in the high-exposure countries over the same time period.

Conclusion

The induced abortion rate in sub-Saharan Africa rose in high-exposure countries relative to low-exposure countries when the Mexico City Policy was reintroduced. Reduced financial support for family planning may have led women to substitute abortion for contraception. Regardless of one’s views about abortion, the findings may have important implications for public policies governing abortion.

Résumé

Objectif

Déterminer si la politique de Mexico City, une politique du gouvernement des États-Unis d’Amérique interdisant le financement d’organisations non gouvernementales pratiquant ou encourageant l’avortement, était associée au taux d’interruptions volontaires de grossesse en Afrique subsaharienne.

Méthodes

Les femmes de 20 pays africains qui avaient subi des IVG entre 1994 et 2008 ont été identifiées dans des études démographiques et sanitaires. L’exposition d’un pays à la politique de Mexico City a été définie comme élevée (ou faible) si l’assistance reçue des États-Unis d’Amérique par habitant pour la planification familiale et la santé génésique était supérieure (ou inférieure) à la moyenne dans les pays étudiés avant le rétablissement de la politique en 2001. Utilisant la régression logistique et une approche différence en différence, les auteurs ont estimé le différentiel des probabilités d’IVG chez les femmes vivant dans les pays hautement exposés par rapport à celles vivant dans des pays faiblement exposés lorsque ladite politique a été réinstituée.

Résultats

L’étude concernait 261 116 femmes âgées de 15 à 44 ans. Une comparaison de la période 1994–2000 avec la période 2001–2008 a révélé un rapport des cotes ajusté pour l’IVG de 2,55 pour les pays fortement exposés par rapport aux pays faiblement exposés à cette politique (intervalle de confiance de 95%, IC: 1,76–3,71). Sur la même période, une baisse relative du recours à des contraceptifs modernes a été notée dans les pays fortement exposés.

Conclusion

Le taux d’interruptions volontaires de grossesse en Afrique subsaharienne a augmenté dans les pays fortement exposés comparativement aux pays faiblement exposés lorsque la politique de Mexico City a été réintroduite. La réduction du soutien financier à la planification familiale peut avoir incité les femmes à remplacer l’avortement par la contraception. Quels que soient les points de vue sur l’avortement, les résultats peuvent avoir des implications importantes pour les politiques publiques en matière d’avortement.

Resumen

Objetivo

Determinar si la Mexico City Policy, política gubernamental estadounidense que prohíbe la financiación a las organizaciones no gubernamentales que realizan o promueven el aborto, estuvo asociada a la tasa de abortos inducidos en África Subsahariana.

Métodos

En Demographic and Health Surveys se identificaron a mujeres en 20 países africanos, que tuvieron abortos inducidos entre 1994 y 2008. La exposición del país a la Mexico City Policy fue considerada alta (o baja) si la asistencia per cápita recibida de los Estados Unidos para planificación familiar y salud reproductiva estuvo por encima (o debajo) de la media entre los países en estudio antes del restablecimiento de la política en 2001. Mediante regresión logística y un diseño de diferencia en diferencias, los autores calcularon el cambio diferencial en las probabilidades de tener un aborto inducido entre mujeres de países con alta exposición respecto a los países con baja exposición, con el restablecimiento de la política.

Resultados

El estudio incluyó a 261116 mujeres de entre 15 y 44 años de edad. Una comparación de 1994-2000 con 2001-2008 reveló una proporción de probabilidades ajustadas de aborto inducido de 2,55 en los países con alta exposición frente a los países con baja exposición, durante la vigencia de la política (95% de intervalo de confianza, IC: 1,76-3,71). Hubo una reducción relativa en el uso de anticonceptivos modernos en los países con alta exposición en el mismo período.

Conclusión

La tasa de abortos inducidos en África Subsahariana se incrementó en los países con alta exposición en comparación con los países con baja exposición, cuando se reintrodujo la Mexico City Policy. La menor asistencia financiera para planificación familiar puede haber llevado a las mujeres a sustituir la anticoncepción con el aborto. Independientemente de la propia opinión sobre el aborto, los hallazgos pueden tener implicaciones importantes para las políticas públicas que rigen el aborto.

ملخص

الغرض

التعرف على ما إذا كانت سياسات مدينة مكسيكو، وسياسات حكومة الأمم المتحدة التي تحظر تمويل المنظمات غير الحكومية التي تمارس الإجهاض وتروج له، ترتبط بمعدل الإجهاض المحرض عليها في البلدان الواقعة جنوب الصحراء الأفريقية.

الطريقة

تم تحديد النساء اللاتي أجرين إجهاضاً محرضاً عليه في 20 بلداً أفريقيا بين عامي 1994 و 2008 في المسوحات الديموغرافية والصحية. وكان يعد تعرض البلد لسياسات مدينة مكسيكو مرتفعاً (أو منخفضاً) إذا كان نصيب الفرد من معونة الولايات المتحدة لتنظيم الأسرة والصحة الإنجابية أكثر من (أو أقل من) الوسيط الإحصائي للبلدان المدرجة في الدراسة قبل إعادة تفعيل السياسات في عام 2001. وباستخدام التحوف اللوجستي وتصميم الاختلاف ضن الاختلاف، قدّر الباحثون تغيراً تفريقياً في أرجحية إجراء الإجهاض المحرض عليه بين النساء في البلدان ذات التعرض المرتفع مقارنة بالبلدان ذات التعرض المنخفض عند إعادة تفعيل السياسات.

النتائج

اشتملت الدراسة على 261116 امرأة في عمر 15 إلى 44 سنة. وقد أظهرت المقارنة بين الفترتين 1994-2000 و 2001-2008 نسبة أرجحية مصححة للإجهاض المحرض عليها قدرها 2.55 للبلدان ذات التعرض المرتفع مقارنة بالبلدان ذات التعرض المنخفض الخاضعين لتطبيق السياسات (فاصلة الثقة 95%: 1.76 – 3.71). وكان هناك انخفاض نسبي في استخدام موانع الحمل الحديثة في البلدان ذات التعرض المرتفع عبر نفس الفترة الزمنية.

الاستنتاج

ارتفع معدل الإجهاض المحرض عليها جنوب الصحراء الأفريقية في البلدان ذات التعرض المرتفع للسياسات مقارنة بالبلدان ذات التعرض المنخفض للسياسات، عندما أعيد تفعيل سياسات مدينة مكسيكو. ومن الممكن أن خفض الدعم المالي المخصص لتنظيم الأسرة قد أدى بالنساء إلى استبدال الإجهاض محل استخدام موانع الحمل. وبغض النظر حول الرأي الشخصي تجاه الإجهاض، فإن النتائج يمكن أن يكون لها تأثيرات هامة على السياسات العمومية التي تتعلق بالإجهاض.

摘要

目的

旨在确定墨西哥城市政策(指美国政府禁止资助那些开展或提倡堕胎的非政府组织)是否与撒哈拉以南非洲地区的人工流产率相关。

方法

根据“人口和健康调查”确定了1994-2008年间20个非洲国家中进行过人工流产的女性。如果从美国获得的人均计划生育和生殖健康援助高于2001年政策恢复前所研究国家的中值,则认为该国受墨西哥城市政策影响的水平高;反之,如果低于所述中值,则认为该国受墨西哥城市政策影响的水平低。本文作者运用逻辑回归和倍差设计来估计政策恢复时相对于政策影响水平低的国家而言,政策影响水平高的国家女性人工流产率的差别变化。

结果

本研究包括了年龄介于15到44岁之间的261,116名女性。1994-2000年与2001-2008年间人工流产率比较发现,政策影响水平高的国家与政策影响水平低的国家之间人工流产的调整比值比为2.55(95%置信区间,1.76-3.71)。同一时期,政策影响水平高的国家中现代避孕用品的使用呈相对下降趋势。

结论

当墨西哥城市政策重新引入时,在撒哈拉以南非洲国家中,相对于政策影响水平低的国家而言,政策影响水平高的国家人工流产率上升。计划生育方面的财政资助减少可能导致女性以堕胎替代避孕。无论人们对堕胎持何种看法,本文的研究结果可能对管理堕胎的公共政策有重要启示。

Резюме

Цель

Установить, существует ли статистическая корреляция между «Политикой Мехико» – запретом правительства США на финансирование неправительственных организаций, которые производят или пропагандируют аборты, и количеством искусственных абортов в странах Африки к югу от Сахары.

Методы

Женщины, искусственно прерывавшие беременность в период с 1994 по 2008 год в 20 африканских странах, выявлялись по данным Докладов о состоянии народонаселения и здравоохранения. Воздействие «Политики Мехико» на страну считалось значительным (или незначительным), если до возобновления данной политики в 2001 году объем помощи США этой стране в области репродуктивного здоровья и планирования семьи был выше (или ниже) медианы по обследуемым странам. Используя логистическую регрессию и метод «разность разностей», авторы оценили дифференциальное изменение шансов искусственного прерывания беременности среди женщин в странах со значительным воздействием по сравнению со странами с незначительным воздействием после возобновления политики.

Результаты

Исследованием были охвачены 261 116 женщин в возрасте от 15 до 44 лет. При сравнении периода 1994–2000 годов с периодом 2001–2008 годов было выявлено скорректированное отношение шансов искусственного прерывания беременности, равное 2,55, для стран со значительным воздействием, по сравнению со странами с незначительным воздействием, в период осуществления политики (95% доверительный интервал, ДИ: 1,76–3,71). В тот же период времени в странах со значительным воздействием происходило относительное снижение использования современных противозачаточных средств.

Вывод

После возобновления «Политики Мехико» число искусственных абортов в Африке к югу от Сахары выросло в странах со значительным воздействием, по сравнению со странами с незначительным воздействием. Сокращение финансовой поддержки планирования семьи могло вынудить женщин заменить аборт контрацепцией. Независимо от взглядов на аборт, результаты нашего исследования могут иметь большое значение для государственной политики управления абортами.

Introduction

Public policies governing abortion are contentious and highly partisan in the United States of America.1 New presidential administrations typically make a critical decision concerning abortion during their first week in office: whether or not to adopt the Mexico City Policy. First announced in Mexico City in 1984 by President Reagan’s administration, the policy requires all nongovernmental organizations operating abroad to refrain from performing, advising on or endorsing abortion as a method of family planning if they wish to receive federal funding. To date, support for the Mexico City Policy has been strictly partisan: it was rescinded by Democratic President Bill Clinton on 22 January 1993, restored by Republican President George W Bush on 22 January 2001 and rescinded again by Democratic President Barack Obama on 23 January 2009.2–4

The Mexico City Policy is motivated by the conviction that taxpayer dollars should not be used to pay for abortion or abortion-related services (such as counselling, education or training).2 The net impact of such a policy on abortion rates is likely to be complex and potentially fraught with unintended consequences. For example, if the Mexico City Policy leads to reductions in support for family planning organizations, and family planning services and abortion are substitute approaches for preventing unwanted births (moral considerations notwithstanding), 5 then the policy could in principle increase the abortion rate. When the policy is in force, family planning organizations that ordinarily provide (or promote) abortion face a stark choice between receiving United States government funding and conducting abortion-related activities. In practice, several prominent family planning organizations, including the International Planned Parenthood Federation and Marie Stopes International, have chosen to forego United States federal funding under the policy.6–8

The primary aim of this study was to determine whether a relationship exists between the reinstatement of the Mexico City Policy and the probability that a sub-Saharan African woman will have an induced abortion. Specifically, we examined the association between a country’s exposure to the Mexico City Policy and changes in its induced abortion rate when the policy was reinstated. Exposure was defined as the amount of foreign assistance provided to the country for family planning and reproductive health by the United States during years when the policy was not being applied. This approach enabled us to control for a variety of potential confounding factors, including fixed effects related to the country and the year of reporting, the women’s place of residence and educational level, the use of modern contraceptives, and the receipt of funding for family planning activities from sources outside the United States. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first quantitative study of the association between the Mexico City Policy and abortion and the first to investigate the possibility of unintended consequences. Regardless of one’s views on abortion, this lack of evidence is a critical impediment to the design of effective foreign policy and has implications for maternal mortality in places where abortion is unsafe.

Methods

We investigated the association between a country’s exposure to the Mexico City Policy and the odds of abortion among women of reproductive age between 1994 and 2008 using the reinstatement of the Mexico City Policy in 2001 as a natural experiment.

Induced abortion data

We used longitudinal, individual data on terminated pregnancies collected by Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) to estimate induced abortion rates. These standardized surveys, designed and implemented by ICF Macro, United States, in collaboration with in-country and international partners, are nationally representative surveys of women aged 15 to 49 years and are conducted approximately every six years in low- and middle-income countries.

We used every available survey with individual data on pregnancy outcomes: 30 surveys in 20 African countries. We examined data from sub-Saharan Africa because health programmes in the region receive substantial foreign assistance. In each survey, women retrospectively reported their pregnancies and pregnancy outcomes (i.e. live births and terminations) for each month during the 5 or 6 years preceding the DHS interview.

To distinguish induced from spontaneous abortions, we adopted an algorithm that uses information about the length of gestation at the time of termination, contraceptive use before the pregnancy, the desirability of the pregnancy, and maternal age and marital status at the time of the pregnancy.9 A termination was classified as induced if either: (i) it occurred following contraceptive failure; or (ii) the terminated pregnancy was unwanted (i.e. the pregnancy occurred after a live birth that was reported as unwanted or would have resulted in the number of children being more than desired); or (iii) the woman was aged under 25 years and was not married or in a union. In addition, the termination was not classified as induced if either: (iv) it occurred in the third trimester; or (v) the woman indicated that contraception had been discontinued to allow pregnancy; or (vi) the woman was married or in a union and had no children. The algorithm was tested using a DHS survey that compared the information used in the algorithm with direct questions about induced abortions (Appendix A, available at: http://bendavid.stanford.edu/research/publications.html). This approach differed from other methods to quantifying induced abortion because it provides individual-level estimates that can be used to make comparisons across countries and over time.10–15The resulting data were used for our statistical analysis and to describe the longitudinal trend in the abortion rate. The abortion rate was expressed as the number of induced abortions among women aged 15 to 44 years per 10 000 woman–years.

Exposure to the Mexico City Policy

For each woman–year of observation we assigned a measure of exposure to the Mexico City Policy. First, we obtained data from the Creditor Reporting System of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) on the financial assistance provided by the United States to the country where the woman lived for family planning and reproductive health services.16,17 Then, we quantified each country’s level of exposure to the Mexico City Policy using the mean value of financial assistance provided per capita by the United States for family planning and reproductive health between 1995 and 2000, when the policy was inactive (data for the period before 1995 were not available). We used this measure to create a dichotomous indicator variable that classified women as living in countries that receive financial assistance for family planning and reproductive health either above or below the median level. Our assumption was that women in countries that received a higher level of financial assistance from the United States for family planning and reproductive health between 1995 and 2000 were more exposed to the effects of a reinstatement of the Mexico City Policy.

We created another index of exposure to the Mexico City Policy using similar data on development assistance for family planning and reproductive health from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). USAID is the main sponsor of nongovernmental organizations funded by the United States and oversees financial assistance directed towards family planning and reproductive health outside the country. We obtained information on USAID disbursements from 1996–2000 in the study countries and created an exposure intensity index similar to the index from the OECD data (termed “USAID” below). The entire analysis, repeated using USAID data, is presented as a sensitivity analysis below and in greater detail in Appendix A.

Statistical analysis

We used logistic regression and a difference-in-difference study design to estimate how the odds of having an induced abortion changed under the Mexico City Policy.18,19 Our approach analysed differential changes in the odds of abortion between women living in high and low exposure countries as the Mexico City Policy was reinstated in 2001. Our main dependent variable was an indicator denoting whether or not a woman had had an induced abortion in a given year. The key independent variable was the interaction between two dummy variables: whether or not the Mexico City Policy was active and whether or not a woman was living in a highly exposed country when the abortion took place. A positive regression coefficient would suggest that the odds that women living in a highly-exposed country had had an induced abortion after the Mexico City Policy was reinstated were higher than the odds of induced abortion both during the earlier period and among women in less exposed countries over the entire study period. We accounted for the interaction between the two dummy variables when calculating the odds ratio (OR) for exposure versus non-exposure.20 We also calculated marginal probabilities, which represent the differential increase in the probability of abortion among women living in highly exposed countries while the policy was in effect. Marginal probabilities were calculated at the means of the independent variables.

We controlled for country and year fixed effects, which account both for unobserved differences across countries that are stable over time and for changes in induced abortions over time that are common to all countries. All confidence intervals (CIs) are calculated using robust standard errors (SEs) clustered by country. This process incorporates the assumption that variation within countries over time is not independent when calculating SEs.21

We also investigated underlying mechanisms that could explain the study findings. In particular, we used data from the United Nations World Contraceptive Use database to determine whether changes in the abortion rate with reinstatement of the Mexico City Policy could be linked to changes in modern contraceptive use.22

Adjusted analyses controlled for both the women’s personal characteristics, such as age, marital status, place of residence (i.e. urban or rural) and educational level, and the characteristics of the country in which she was living, such as life expectancy,23 modern contraceptive use22 and the legality of abortion.24,25 To take into account the possibility that other donors compensated for restrictions imposed by the Mexico City Policy, we also adjusted for annual per capita donations for family planning and reproductive health services from all other OECD countries.16

In addition to our adjusted analyses, we also conducted several sensitivity tests. First, we reanalysed our data leaving out one survey at a time to see if our results were sensitive to a particular survey’s inclusion. We repeated this procedure for each country and for each year as well. Second, we repeated our analyses using different measures of Mexico City Policy exposure, namely a continuous measure of United States assistance per capita for family planning and reproductive health and a comparable measure of exposure based on data obtained from USAID. Finally, we repeated the analyses with shorter recall windows that restricted the information we used from the DHS pregnancy calendars. These analyses are presented in Appendix A. All statistical analyses were performed with Stata 11.2 (Stata Corp, Texas, USA). The study was exempted from human subjects review by the Stanford Institutional Review Board.

Results

Our study included data from 30 DHS surveys conducted in 20 countries between 1994 and 2008 in a total of 261 116 women (1.38 million woman–years). Table 1 (available at: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/89/12/11-091660) shows the study countries and the years for which data were available; Table 2 provides descriptive statistics for our study sample and compares exposure countries and the study population with sub-Saharan Africa. The sample represented 49% of all women of reproductive age in sub-Saharan Africa. Table 2 compares the characteristics of our study sample with equivalent data for the population of sub-Saharan Africa as a whole23: there was no significant difference between the two in life expectancy at birth, mean country population, the proportion of the population living in an urban setting and country mean per capita gross domestic product.

Table 1. Induced abortions in 20 sub-Saharan African countries and exposure to the Mexico City Policy, 1994–2008.

| Country | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | Year of DHS | Exposure to Mexico City Policya |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benin | 2006 | High | |||||||||||||||

| Abortions, no. | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 | NA | NA | ||

| Observation period, woman–years | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2 473 | 6 224 | 9 213 | 10 393 | 11 401 | 11 447 | 11 320 | NA | NA | ||

| Burkina Faso | 2003 | Low | |||||||||||||||

| Abortions, no. | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Observation period, woman–years | NA | NA | NA | 1 922 | 4 421 | 6 495 | 7 246 | 7 840 | 7 840 | 7 709 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Ethiopia | 2005 | Low | |||||||||||||||

| Abortions, no. | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 6 | 9 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 23 | 11 | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Observation period, woman–years | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 10 200 | 10 879 | 11 302 | 11 929 | 12 355 | 12 716 | 12 901 | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Ghana | 2003, 2008 | High | |||||||||||||||

| Abortions, no. | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 12 | 21 | 23 | ||

| Observation period, woman–years | NA | NA | NA | 738 | 1 668 | 2 411 | 2 776 | 3 086 | 3 110 | 6 942 | 4 012 | 4 161 | 4 287 | 4 383 | 4 446 | ||

| Guinea | 2005 | High | |||||||||||||||

| Abortions, no. | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Observation period, woman–years | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2 179 | 3 164 | 3 929 | 4 426 | 4 800 | 4 799 | 4 745 | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Kenya | 1998, 2003, 2008 | Low | |||||||||||||||

| Abortions, no. | 7 | 13 | 13 | 15 | 10 | 15 | 16 | 19 | 25 | 16 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 26 | 43 | ||

| Observation period, woman–years | 6 433 | 6 701 | 6 930 | 7 193 | 13 755 | 6 790 | 7 058 | 7 321 | 7 525 | 14 169 | 6 827 | 7 066 | 7 279 | 7 536 | 7 695 | ||

| Madagascar | 2003–2004, 2008 | High | |||||||||||||||

| Abortions, no. | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 21 | 22 | 32 | 46 | 53 | ||

| Observation period, woman–years | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2 487 | 3 103 | 3 641 | 4 146 | 4 318 | 17 470 | 16 489 | 14 192 | 14 739 | 15 304 | 15 756 | ||

| Malawi | 2000, 2005 | High | |||||||||||||||

| Abortions, no. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 7 | 21 | 14 | 14 | 17 | 24 | 59 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Observation period, woman–years | 1 640 | 4 262 | 6 453 | 7 529 | 8 448 | 17 769 | 18 118 | 10 001 | 10 293 | 10 586 | 10 848 | 2 639 | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Mali | 2001, 2006 | High | |||||||||||||||

| Abortions, no. | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | NA | NA | ||

| Observation period, woman–years | 1 229 | 3 075 | 6 125 | 7 443 | 8 290 | 9 181 | 10 967 | 14 207 | 7 740 | 8 716 | 9 496 | 9 567 | 9 528 | NA | NA | ||

| Mozambique | 2003–2004 | High | |||||||||||||||

| Abortions, no. | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Observation period, woman–years | NA | NA | NA | 1 442 | 3 828 | 5 870 | 6 786 | 7 613 | 7 767 | 7 750 | 73 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Niger | 2006 | Low | |||||||||||||||

| Abortions, no. | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | NA | NA | ||

| Observation period, woman–years | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2 939 | 4 279 | 5 215 | 5 807 | 6 137 | 6 098 | 6 050 | NA | NA | ||

| Nigeria | 2008 | Low | |||||||||||||||

| Abortions, no. | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 9 | 21 | 31 | 50 | 48 | 35 | ||

| Observation period, woman–years | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 26 808 | 27 317 | 28 276 | 29 052 | 29 850 | 30 347 | ||

| Rwanda | 2000, 2005 | Low | |||||||||||||||

| Abortions, no. | 0 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 10 | 12 | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Observation period, woman–years | 1 282 | 3 143 | 4 454 | 4 905 | 6 126 | 7 043 | 9 124 | 4 859 | 5 342 | 5 635 | 5 572 | 5 477 | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Senegal | 2005 | High | |||||||||||||||

| Abortions, no. | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Observation period, woman–years | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 3 510 | 5 047 | 6 395 | 7 222 | 7 775 | 7 767 | 7 685 | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Sierra Leone | 2008 | Low | |||||||||||||||

| Abortions, no. | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 12 | 5 | ||

| Observation period, woman–years | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 6 174 | 6 335 | 6 585 | 6 705 | 6 828 | 6 819 | ||

| Swaziland | 2006–2007 | Low | |||||||||||||||

| Abortions, no. | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 14 | 0 | NA | ||

| Observation period, woman–years | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 3 720 | 3 918 | 4 086 | 4 260 | 4 416 | 4 566 | 1 074 | NA | ||

| Uganda | 2000–2001, 2006 | Low | |||||||||||||||

| Abortions, no. | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 9 | 16 | 12 | 9 | 12 | 14 | 30 | 36 | 29 | NA | NA | ||

| Observation period, woman–years | 652 | 2 165 | 3 546 | 4 110 | 4 528 | 4 652 | 4 628 | 8 997 | 6 839 | 7 125 | 7 342 | 7 624 | 7 886 | NA | NA | ||

| United Republic of Tanzania | 2004–5 | High | |||||||||||||||

| Abortions, no. | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 8 | 19 | 13 | 27 | 43 | 74 | 3 | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Observation period, woman–years | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 7 978 | 8 253 | 8 608 | 8 889 | 9 255 | 9 450 | 2 959 | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Zambia | 2007 | High | |||||||||||||||

| Abortions, no. | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 3 | 9 | 9 | 18 | 21 | 14 | NA | ||

| Observation period, woman–years | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 5 603 | 5 817 | 6 035 | 6 222 | 6 482 | 6 624 | NA | ||

| Zimbabwe | 1994,b 1999, 2005–2006 | Low | |||||||||||||||

| Abortions, no. | 15 | 14 | 11 | 21 | 20 | 31 | 10 | 18 | 18 | 19 | 34 | 23 | 6 | NA | NA | ||

| Observation period, woman–years | 10 119 | 4 657 | 4 878 | 5 098 | 5 340 | 5 476 | 6 778 | 7 094 | 7 433 | 768 | 8 011 | 8 226 | 1 906 | NA | NA |

DHS, Demographic and Health Survey; NA, not available.

a Exposure to the Mexico City Policy was classified as high or low according to whether the level of per capita financial assistance provided to the country for family planning and reproductive health by the United States was above or below the median for the period 1995 to 2000. Data on financial assistance were obtained from the Creditor Reporting System of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

b Only data for 1994 from this survey were used in the primary analysis.

Table 2. Characteristics of the 20 countries included in a study of abortion rates and exposure to the Mexico City Policy, compared with all sub-Saharan Africa, 1994–2008.

| Country characteristics | Countries, by level of exposure to the Mexico City Policya |

P for difference by exposurec | All sub-Saharan African countriesd | P for difference by country groupe | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allb | Low | High | ||||

| Mean life expectancy, years | 52.0 | 50.6 | 53.4 | 0.26 | 52.8 | 0.69 |

| Mean population in an urban environment, % | 29.6 | 30.1 | 28.1 | 0.62 | 36.9 | 0.07 |

| Mean country population, millions | 20.0 | 26.7 | 13.3 | 0.25 | 19.0 | 0.86 |

| Total population in all countries in 2008, millions | 400 | 267 | 133 | NA | 816 | NA |

| Per capita gross domestic product, US dollarsf | 1353 | 1462 | 1245 | 0.61 | 2964 | 0.21 |

| Women using modern contraceptives, % | ||||||

| 1994 | 11.9 | 14.7 | 9.0 | 0.28 | NA | NA |

| 2008 | 18.9 | 22.2 | 15.6 | 0.34 | NA | NA |

NA, not available; US; United States.

a Exposure to the Mexico City Policy was classified as high or low according to whether the level of per capita financial assistance provided to the country for family planning and reproductive health by the United States was above or below the median for the period 1995 to 2000.

b Includes data for all women reported in 30 Demographic and Health Surveys carried out in 20 sub-Saharan African countries between 1994 and 2008.

c P-value for two-sided t-test of the difference in descriptive parameters between countries with low and high levels of exposure.

d Data for all sub-Saharan African countries, including the study countries.

e P-value for the difference in descriptive parameters between all study countries and all sub-Saharan African countries.

f The per capita gross domestic product is corrected for purchasing power parity in 2011.

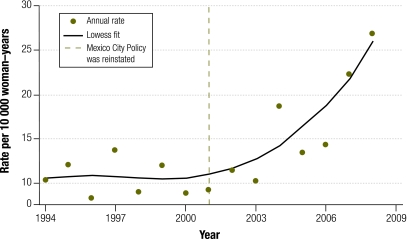

The estimated annual induced abortion rate in the 20 study countries between 1994 and 2008 is illustrated in Fig. 1. The mean annual rate was 13 abortions per 10 000 woman–years and ranged from 8 per 10 000 in 1996 to 27 per 10 000 in 2007. The lowess (locally weighted scatterplot smoothing) curve indicates that the rate was stable between 1994 and 2001 and then rose steadily from 2002 to 2008. Overall, the induced abortion rate increased significantly from 10.4 per 10 000 woman–years for the period from 1994 to 2001 to 14.5 per 10 000 woman–years for the period from 2001 to 2008 (P = 0.01). Although the trend changed gradually, the timing of the rise is consistent with the reinstatement of the Mexico City Policy in early 2001.

Fig. 1.

Induced abortion rate in 20 sub-Saharan African countries, 1994–2008a

a The curve was generated from observational data using the locally weighted scatterplot smoothing (lowess) method.

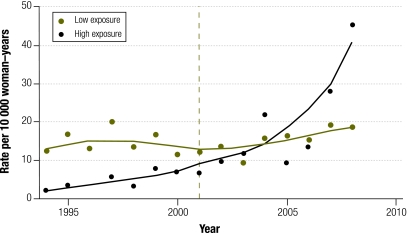

Fig. 2 then shows trends in the abortion rate separately for countries with high and low levels of exposure to the Mexico City Policy. The figure suggests that the annual induced abortion rate remained stable between 1994 and 2008 in countries with low exposure to the policy, at about 10–20 induced abortions per 10 000 woman–years, whereas it rose sharply after 2001 in countries with high exposure.

Fig. 2.

Induced abortion rates in 20 sub-Saharan African countries, by exposure to the Mexico City Policy,a 1994–2008b,c

a Exposure to the Mexico City Policy was classified as high or low according to whether the level of per capita financial assistance provided to the country for family planning and reproductive health by the United States was above or below the median for the period from 1995 to 2000.

b The dashed vertical line indicates the year the Mexico City Policy was reinstated.

c The two curves were generated from observational data using the locally weighted scatterplot smoothing (lowess) method.

Table 3 presents our primary statistical results. The first row shows the differential increase in odds of abortion for women living in a highly-exposed country when the Mexico City Policy was reinstated. Each column shows a different model specification. Women living in highly exposed countries had 2.73 (95% CI: 1.95–3.82) times the odds of having an induced abortion after the policy's reinstatement than during the period from 1994 to 2000 or than women living in less exposed countries. After adjustments for place of residence, educational attainment, use of contraceptives and funding for family planning and reproductive health from sources other than the United States, the estimated OR dropped to 2.55 (95% CI: 1.76–3.71). Using a marginal probability calculation at the mean of the independent variables, we estimated that the probability of having an induced abortion exceeded the predicted odds of abortion in the absence of the policy by 9.9 per 10 000 woman-years (P < 0.001). A likelihood ratio test of the principal model compared with a model of women living in less exposed countries suggested a significant difference in odds between the less exposed and the highly exposed populations (P < 0.001): the OR of an abortion using USAID data for determining country exposure was 1.82 (95% CI: 1.09–3.02). Additional results using USAID data for country exposure are available in Appendix A.

Table 3. Unadjusted and adjusted estimates of abortion risk associated with the Mexico City Policy.

| Parameter | Unadjusteda |

Adjusted for woman characteristicsb |

Adjusted for woman and country characteristicsc |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |||

| Risk of abortion when the policy was active in highly exposed countriesd | 2.73 | 1.95–3.82 | 2.70 | 1.91–3.82 | 2.55 | 1.76–3.71 | ||

| Living in urban setting | – | – | 0.75 | 0.64–0.88 | 0.74 | 0.63–0.87 | ||

| Ever attended school | – | – | 1.95 | 1.30–2.92 | 1.94 | 1.29–2.91 | ||

| Woman’s age (per additional year) | – | – | 1.02 | 1.00–1.04 | 1.02 | 1.00–1.04 | ||

| Married at time of abortion | – | – | 1.82 | 1.28–2.60 | 1.80 | 1.27–2.56 | ||

| Use of modern contraceptives (per additional 1% in country–year) | – | – | – | – | 0.95 | 0.90–0.99 | ||

| Funding for family planning and reproductive health from non-US OECD countries (per each additional US dollar per person) | – | – | – | – | 0.97 | 0.82–1.15 | ||

CI, confidence interval; OECD, Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development; OR, odds ratio; US, United States.

a Includes country and year fixed effects only.

b Includes controls for age, marital status at the time of observation, place of residence and educational attainment in addition to country and year fixed effects.

c Includes controls for prevalence of modern contraceptive use in country and non-US support for family planning and reproductive health in addition to woman characteristics and country and year fixed effects only.

d Odds ratio of having an induced abortion among women living in highly exposed countries when the Mexico City Policy was active compared with the previous period and with abortion odds among women living in less exposed countries during the entire period.

We also examined whether the number of years during which the Mexico City Policy was in force was associated with the rate of induced abortion. We estimated that, for each additional year under the Mexico City Policy, the odds of having an induced abortion were 1.21 times higher among women living in a country with a high level of exposure between 2001 and 2008 than among women in the reference groups (OR: 1.21; 95% CI: 1.10–1.37).

We repeated our analysis using a continuous measure of exposure to the policy: the mean per capita assistance for family planning and reproductive health provided to each country by the United States between 1995 and 2000. We found a positive but nonsignificant association between each additional United States dollar of per capita assistance and the odds of an induced abortion (OR: 1.07: 95% CI: 0.91–130).

We investigated whether our findings were influenced by the recall period, i.e. the time between the pregnancy outcome and the date of the DHS in which it was recorded. The reliability of recall may decrease with time. We found that the length of recall window used to construct our sample did affect the study’s power but did not result in substantial bias (Appendix A, Fig. A).

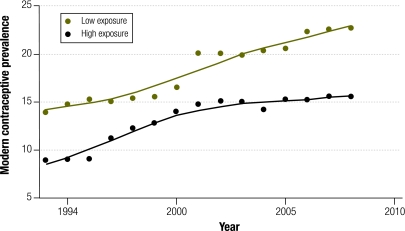

Finally, to explore underlying behavioural responses that could explain our main results, we investigated whether exposure to the Mexico City Policy was associated with modern contraceptive use. The variation in contraceptive use between 1994 and 2008 in countries with high or low levels of exposure to the policy is shown in Fig. 3. The increase in contraceptive use proceeded at a slower pace after 2002 in countries with a high level of exposure, whereas in countries with a low exposure the increase continued at the same pace. We repeated our main regression analysis using the prevalence of modern contraceptive use as the dependent variable and found this to be 1.8% lower (95% CI: 0.1–3.4) under the Mexico City Policy than expected in the light of trends in low exposure countries.

Fig. 3.

Prevalence of modern contraceptive use in 20 sub-Saharan African countries, by exposure to the Mexico City Policy,a 1994–2008b

a Exposure to the Mexico City Policy was classified as high or low according to whether the level of per capita financial assistance provided to the country for family planning and reproductive health by the United States was above or below the median for the period from 1995 to 2000.

b The two curves were generated from observed data using the locally weighted scatterplot smoothing (lowess) method.

Discussion

Some American presidential administrations care deeply about curtailing access to abortion, whereas others seek to promote it. Regardless of one’s views, an understanding of the relationship between the Mexico City Policy and abortion rates in developing countries is important for foreign policy decisions. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first quantitative analysis of the policy’s possible implications for women living in countries that depend heavily on development assistance for family planning and reproductive health services.

Our study found robust empirical patterns suggesting that the Mexico City Policy is associated with increases in abortion rates in sub-Saharan African countries. Although we are unable to draw definitive conclusions about the underlying cause of this increase, the complex interrelationships between family planning services and abortion may be involved. In particular, if women consider abortion as a way to prevent unwanted births, then policies curtailing the activities of organizations that provide modern contraceptives may inadvertently lead to an increase in the abortion rate.

Several observations strengthen this conclusion. First, the association is strong: the odds of having an abortion in highly exposed countries were more than twice the odds observed in the reference groups. Second, there is broad agreement among our aggregate graphical analysis and both unadjusted and adjusted statistical analyses, and our main findings are robust across a variety of sensitivity analyses. Third, the timing of divergence between high and low exposure countries is coincident with the policy’s reinstatement: in high exposure countries, abortion rates began to rise noticeably only after the Mexico City Policy was reinstated in 2001 and the increase became more pronounced from 2002 onward. Finally, our findings are consistent with those of previous studies on the relationship between family planning activities and abortion.5

Given the potential implications of our study, its limitations deserve careful attention. First, our abortion rate estimates are lower, on average, than rates reported elsewhere,26,27 most of which used a multiplier to correct for underreporting. However, if the level of underreporting is not related to the level of exposure to the Mexico City Policy or to the timing of the policy’s implementation, then our approach to estimating changes associated with the policy is acceptable given our statistical model, since we were interested in changes over time rather than the absolute abortion rate. Second, our results may depend on the specific countries included in the study and may not be generalizable to other countries receiving financial assistance from the United States. Nonetheless, our results were not affected by the omission of any single DHS or country, nor were they influenced by using an alternative data source to define countries with a high or low level of exposure to the Mexico City Policy (Appendix A). Third, changes in presidential administration often bring changes in foreign relations, and a country that received a high level of aid from the United States for family planning before 2001 may have become a less-favoured nation and received less aid under the subsequent administration. Although we cannot rule out this possibility, this mechanism would support our premise that funding for family planning services has a paradoxical effect on abortion outcomes. Fourth, the observed rise in abortion rates may be a result of an ideational change in favour of smaller families that took place in countries with a high level of exposure to the Mexico City Policy when it was reinstated.28,29 However, this change is not likely to have occurred over such a short period of time. Finally, the pregnancy calendars we used to estimate abortion rates are a relatively new component of the DHSs and further research is needed to fully establish their reliability. Continued monitoring of the trend in abortion rates since the policy was last rescinded will provide more data on its impact.

We conclude by noting that beyond the scope of this study, the relationship between the Mexico City Policy and reproductive health deserves attention. With growing international emphasis on reducing maternal mortality, in keeping with Millennium Development Goal 5, our findings suggest that this United States policy may have unrecognized – and unintended – health consequences.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Paul Blumenthal at Stanford University, Kristin Wilson at Harvard Business School and Manisha Shah at the University of California in Irvine.

Funding:

Eran Bendavid is supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (K01-AI084582) and by the George Rosenkranz Prize for Health Care Research in Developing Countries. Grant Miller receives support from the National Institute of Child Health and Development and the National Institute of Aging. Both receive support from the Center on the Demography and Economics of Health and Aging (P30-AG17253). The funding agencies played no part in the study or its analysis and reporting.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Annas GJ. Abortion politics and health insurance reform. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2589–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0911513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.United States Agency for International Development [Internet]. Restoration of the Mexico City Policy concerning family planning. Washington: USAID; 2011. Available from: http://www.usaid.gov/bush_pro_new.html [accessed 14 Sept 2011].

- 3.The White House [Internet]. Mexico City Policy – voluntary population planning: memorandum for the Secretary of State and the Administrator of the United States Agency for International Development. Washington: The White House; 2009. Available from: http://www.whitehouse.gov/the_press_office/MexicoCityPolicy-VoluntaryPopulationPlanning/ [accessed 31 August 2011].

- 4.AID Family Planning Grants/Mexico City Policy. Washington: The White House; 1993. Available from: http://clinton6.nara.gov/1993/01/1993-01-22-aid-family-planning-grants-mexico-city-policy.html [accessed 31 August 2011].

- 5.Bongaarts J, Westoff CF. The potential role of contraception in reducing abortion. Stud Fam Plann. 2000;31:193–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2000.00193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boseley S. Condom supply to Africa hit by US abortion policy. The Guardian 2003 25 September. Available from: http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2003/sep/25/aids.usa [accessed 22 August 2011].

- 7.Crossette B. Implacable force for family planning. The New York Times. 2002 30 July. Available from: http://www.nytimes.com/2002/07/30/health/implacable-force-for-family-planning.html [accessed 22 August 2011].

- 8.AIDS and abortion policy. Pregnant pause: how one policy undermines another. The Economist. 2003 25 September. Available from: http://www.economist.com/node/2091350 [accessed 22 August 2011]. [PubMed]

- 9.Magnani RJ, Rutenberg N, McCann H. Detecting induced abortions from reports of pregnancy terminations in DHS calendar data. Stud Fam Plann. 1996;27:36–43. doi: 10.2307/2138076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henshaw S, Singh S, Oye-Adeniran B, Adewole I, Iwere N, Cuca Y. The incidence of induced abortion in Nigeria. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 1998;24:156–64. doi: 10.2307/2991973. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huntington D, Mensch B, Toubia N. A new approach to eliciting information about induced abortion. Stud Fam Plann. 1993;24:120–4. doi: 10.2307/2939205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Houzard S, Bajos N, Warszwawski J, de Guibert-Lantoine C, Kaminski M, Leridon H, et al. Analysis of the underestimation of induced abortions in a survey of the general population in France. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2000;5:52–60. doi: 10.1080/13625180008500370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmed M, Rahman M, Van Ginneken J. Induced abortion in Matlab, Bangladesh: trends and determinants. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 1998;24:128–32. doi: 10.2307/3038209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stover J. Revising the proximate determinants of fertility framework: What have we learned in the past 20 years? Stud Fam Plann. 1998;29:255–67. doi: 10.2307/172272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rossier C. Estimating induced abortion rates: a review. Stud Fam Plann. 2003;34:87–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2003.00087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.OECD.StatExtracts [Internet]. Creditor Reporting System, full. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development; 2010. Available from: http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DatasetCode=CRSNEW [accessed 23 September 2011].

- 17.Ravishankar N, Gubbins P, Cooley RJ, Leach-Kemon K, Michaud CM, Jamison DT, et al. Financing of global health: tracking development assistance for health from 1990 to 2007. Lancet. 2009;373:2113–24. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60881-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shadish W, Cook T, Campbell D. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meyer BD. Natural and quasi-experiments in economics. J Bus Econ Stat. 1995;13:151–61. doi: 10.2307/1392369. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ai C, Norton EC. Interaction terms in logit and probit models. Econ Lett. 2003;80:123–9. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1765(03)00032-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bertrand M, Duflo E, Mullainthan S. How much should we trust differences-in-differences estimates? Q J Econ. 2004;119:249–75. doi: 10.1162/003355304772839588. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World contraceptive use 2009 New York: United Nations Population Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs; 2009.

- 23.World Development Indicators Online (WDI) Washington: The World Bank; 2011. Available from: databank.worldbank.org/ [accessed 14 Sept 2011].

- 24.Bloom D, Canning D, Fink G, Finlay J. Fertility, female labor force participation, and the demographic dividend. J Econ Growth. 2009;14:79–101. doi: 10.1007/s10887-009-9039-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abortion policies: a global review New York: United Nations, Population Division; 2002. Available from: http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/abortion/index.htm [accessed 31 August 2011].

- 26.Henshaw SK, Singh S, Haas T. The incidence of abortion worldwide. Int Fam Plann Persp. 1999;25:S30–8. doi: 10.2307/2991869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sedgh G, Henshaw S, Singh S, Åhman E, Shah I. Induced abortion: estimated rates and trends worldwide. Lancet. 2007;370:1338–45. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61575-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Henshaw SK, Singh S, Haas T. Recent trends in abortion rates worldwide. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 1999;25:44–8. doi: 10.2307/2991902. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rahman M, DaVanzo J, Razzaque A. Do better family planning services reduce abortion in Bangladesh? Lancet. 2001;358:1051–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06182-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]