Abstract

Aims: Peroxiredoxin 6 (Prdx6), a bifunctional enzyme with glutathione peroxidase and phospholipase A2 (PLA2) activities, has been demonstrated as playing a critical role in antioxidant defense of the lung. Our aim was to evaluate the relative role of each activity in Prdx6-mediated protection of mouse pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (PMVECs) against the peroxidative stress of treatment with tert-butyl hydroperoxide (tBOOH). Results: PMVEC from Prdx6 null mice showed increased lethality on tBOOH exposure (50–200 μM) compared with wild-type (WT) controls. Treatment with 1-hexadecyl-3-trifluoroethylglycero-sn-2-phosphomethanol (MJ33), a Prdx6 PLA2 activity inhibitor, increased the sensitivity of WT cells to peroxidative stress, but did not further sensitize Prdx6 null cells. Lethality in Prdx6 null PMVEC was “rescued” by transfection with a construct leading to the expression of WT rat Prdx6. Expression of mutant Prdx6 with either peroxidase activity or PLA2 activity alone each partially rescued the survival of Prdx6 null cells, while constructs with both active sites mutated failed to rescue. Co-transfection with two different constructs, each expressing one activity, rescued cells as well as the WT construct. Innovation and Conclusion: Contrary to the general assumption that the peroxidase activity is the main mechanism for Prdx6 antioxidant function, these results indicate that the PLA2 activity also plays a substantial role in protecting cells against oxidant stress caused by an exogenous hydroperoxide. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 16, 440–451.

Introduction

Peroxiredoxins are a relatively novel and widely distributed superfamily of peroxidases that can scavenge H2O2 and other hydroperoxides (38). Members of the peroxiredoxin family are divided into two subgroups: 2-Cys and 1-Cys peroxiredoxins based on the number of conserved cysteines. Peroxiredoxin 6 (Prdx6), the only mammalian 1-Cys member of the peroxiredoxin family, is a bifunctional protein that expresses both phospholipase A2 (PLA2) and peroxidase activities (4, 11) and uses glutathione (GSH) instead of thioredoxin as the physiological reductant (4, 16, 26). Prdx6 has the ability to reduce phospholipid hydroperoxides in addition to H2O2 and other hydroperoxides (16). This peroxidase activity is dependent on the catalytic Cys at position 47 (4). After oxidation, the catalytic Cys is reduced by GSH S-transferase-bound GSH to complete the catalytic cycle (26, 35, 36). Prdx6 is highly expressed in the lung (17, 21) and reports that Prdx6 null lungs and lung epithelial cells are more susceptible to oxidative injury and are protected by overexpression of Prdx6 indicate that it is a critical lung antioxidant enzyme (24, 41–46). A second enzymatic function of Prdx6 is a calcium-independent PLA2 activity. This activity is dependent on a catalytic triad: Ser32, His26, and Asp140 (27), which catalyze the hydrolysis of the acyl group at the sn-2 position of glycerophospholipids (11). The PLA2 activity of Prdx6 has been reported to play a major role in the metabolism of the phospholipids of lung surfactant (15) and to activate NADPH oxidase (3).

Innovation.

The bifunctional antioxidant enzyme, peroxiredoxin 6 (Prdx6), has been shown to protect against damage caused by oxidative stress in both cellular and animal models. The enzyme is capable of both glutathione peroxidase activity and phospholipase A2 (PLA2) activity. A reasonable assumption would be that the antioxidant function of Prdx6 relied on its peroxidase activity. However, in this study, we have shown, both by the use of an inhibitor 1-hexadecyl-3-trifluoroethylglycero-sn-2-phosphomethanol (MJ33) and by rescue experiments in Prdx6 null cells, that full protection requires both activities. The evidence provided by this study that both peroxidase and PLA2 activities are necessary for the full protective effect of Prdx6 has implications for applications seeking to use Prdx6 to protect against oxidative stress as well as for applications seeking to block the protective activity of Prdx6, such as in anticancer therapy.

Although the protein has two activities, a reasonable assumption is that the basis for Prdx6 antioxidant function is related to reduction of short-chain hydroperoxides and/or phospholipid hydroperoxides associated with its peroxidase activity. However, the PLA2 activity of Prdx6 could also participate in its protection against oxidants related to its ability to cleave the sn-2 fatty acyl group of oxidized phospholipids. Since the possibility has not been previously evaluated, we investigated the role of each activity in Prdx6-mediated protection against peroxidative stress in mouse pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (PMVECs) by using inhibitor and rescue strategies. Our results show that both peroxidase and PLA2 activities are necessary for the enzyme to fully protect cells against a hydroperoxide stress.

Results

Peroxiredoxin 6 protects mouse PMVEC against peroxidative damage

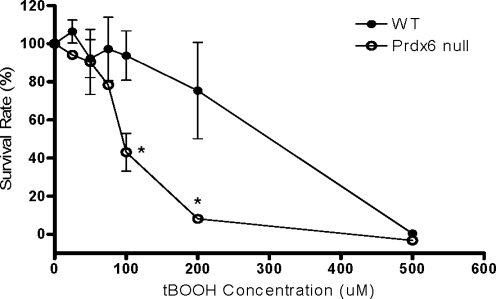

To investigate the role of Prdx6 in peroxidative stress-induced injury, PMVEC from wild-type (WT) and Prdx6 null mice were treated with varying concentrations of tert-butyl hydroperoxide (tBOOH) for 24 h, and the survival rates were determined by 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2.5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. Cell survival rates after tBOOH treatment were decreased in a dose-dependent manner in both WT and Prdx6 null cells; however, Prdx6 null PMVEC were significantly more sensitive than WT cells to peroxidative stress (Fig. 1). The tBOOH dose for 50% lethality (LD50) of WT and Prdx6 null PMVEC was 289±50.0 and 95.8±6.1 μM, respectively.

FIG. 1.

Survival of wild-type (WT) and peroxiredoxin 6 (Prdx6) null pulmonary microvascular endothelial cell (PMVEC) in response to peroxidative stress. The survival rates for WT or Prdx6 null cells after treatment with indicated concentrations of tert-butyl hydroperoxide (tBOOH) for 24 h were measured by 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2.5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay (n=3). Data are expressed as mean±standard error (SE). *p<0.05 compared with the corresponding WT groups.

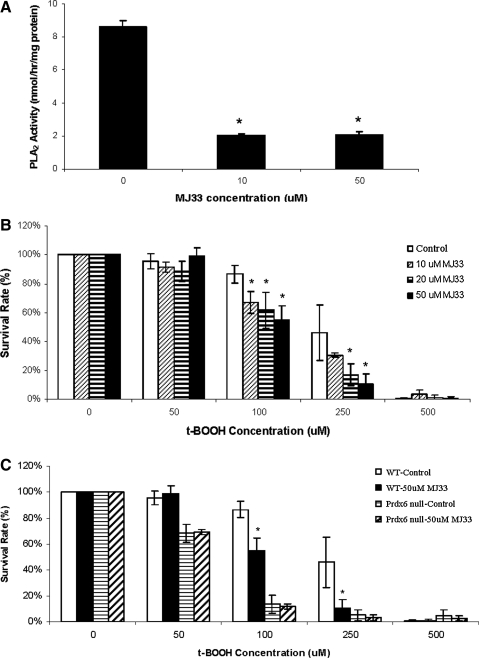

Inhibition of PLA2 activity by MJ33 exacerbated peroxidative stress-induced cell injury in WT PMVEC

A possible role of the PLA2 activity of Prdx6 in its antioxidant function was investigated. PMVEC were treated with 1-hexadecyl-3-trifluoroethylglycero-sn-2-phosphomethanol (MJ33), a competitive inhibitor of Prdx6 PLA2 activity, and cell survival in response to tBOOH was studied. PLA2 activity was inhibited by about 80% by treatment of WT PMVEC with either 10 or 50 μM MJ33 (Fig. 2A). Pre-treatment with 10–50 μM MJ33 significantly decreased the survival rates of WT cells co-treated with 100 or 250 μM tBOOH, although no effects were seen at lower or higher tBOOH concentrations (Fig. 2B). At 50 μM MJ33 and 100 μM tBOOH, cell death was increased by 30%–35% compared with tBOOH treatment alone. These results indicate the increased sensitivity of WT cells to peroxidative stress when Prdx6 PLA2 activity is inhibited. No effect of MJ33 was seen in Prdx6 null PMVEC, indicating that the increased cell death in WT cells was not due to MJ33 toxicity, but to its inhibition of PLA2 activity (Fig. 2C).

FIG. 2.

Effect of inhibition of Prdx6 phospholipase A2 (PLA2) activity by 1-hexadecyl-3-trifluoroethylglycero-sn-2-phosphomethanol (MJ33) on survival of WT and Prdx6 null PMVEC when subjected to peroxidative stress. (A) MJ33 inhibition of PLA2 activity. WT PMVEC were treated with 0, 10, or 50 μM MJ33 for 30 min, and cells were harvested for PLA2 activity assay. (B) MJ33 effect on survival of WT PMVEC. Cells were co-treated with 0, 10, 20, or 50 μM MJ33 and indicated concentrations of tBOOH for 24 h. (C) Comparison of MJ33 effect on WT and Prdx6 null PMVEC. Cells were co-treated with 0 or 50 μM MJ33 at the indicated concentrations of tBOOH for 24 h. The survival rates were measured by MTT assay. Data are expressed as mean±SE (n≥3). *p<0.05 compared with the corresponding control groups.

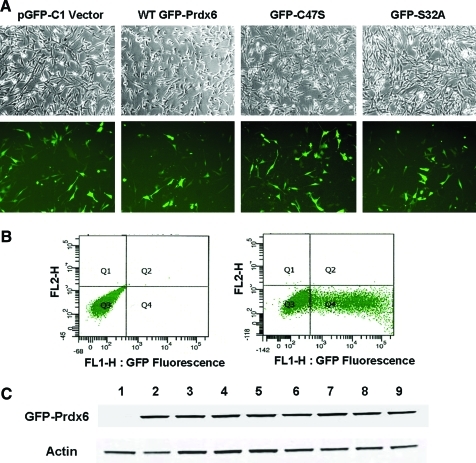

Restoration of the peroxidase and PLA2 activities of Prdx6 null PMVEC

The ability of the PLA2 inhibitor, MJ33, to increase the sensitivity of PMVEC to oxidative stress indicates that the PLA2 activity of Prdx6 may play a role in the antioxidant function of the protein. However, possible nonspecificity of the inhibitor would complicate the analysis of the results. To further evaluate the importance of each activity in Prdx6-mediated protection against peroxidative stress, we generated pGFP-Prdx6 plasmids with mutations in the key amino acids for PLA2 and peroxidase activities (Table 1), and conducted a series of rescue studies using Prdx6 null PMVEC transfected with pGFP-C1 vector or various pGFP-Prdx6 constructs. Green fluorescence from green fluorescent protein (GFP) (Fig. 3A) indicates successfully transfected cells. The transfection efficiency was 46%±1.4% when cells were analyzed by flow cytometry (Fig. 3B) and was 48.3%±4.8% when estimated by epifluorescence microscopy (the number of cells with light to bright green fluorescence divided by the total cell number) (Fig. 3A). The transfection efficiencies were similar among all the groups of cells that were studied. Surviving cells after electroporation showed no apparent cytotoxicity. The successful expression of the GFP-Prdx6 fusion protein was confirmed by Western analysis (Fig. 3C).

Table 1.

Mutants of Peroxiredoxin 6 and Functional Consequences

| |

|

Residual activitya |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prdx6 mutation | Known consequence | PLA2 | H2O2/tBOOH | PCOOH |

| Wild type | None | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| H26A | Disruption of PLA2 catalytic triad and substrate binding site | X | ✔ | ↓↓ |

| D31A | None | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| S32A | Disruption of PLA2 catalytic triad and substrate binding site | X | ✔ | ↓↓ |

| C47S | Loss of peroxidase catalytic site | ✔ | X | X |

| D140A | Disruption of PLA2 catalytic triad | X | ✔ | ✔ |

✔, activity present; X, activity absent;↓, activity reduced. H2O2/tBOOH and PCOOH indicate peroxidase activity with non-lipid peroxide or phospholipid hydroperoxide substrate, respectively.

PCOOH, 1-palmitoyl-2-linoleoyl-sn-glycero-3 phosphocholine hydroperoxide; Prdx6, peroxiredoxin 6; PLA2, phospholipase A2; tBOOH, tert-butyl hydroperoxide.

FIG. 3.

Efficiency of transfection of Prdx6 null PMVEC. (A) Transfection evaluated by green fluorescent protein (GFP) fluorescence. Prdx6 null PMVEC were transfected with pGFP-C1 vector or different pGFP-Prdx6 constructs by electroporation and incubated for 48 h. Upper panel shows phase images. Lower panel shows the green fluorescence from transfected cells. (B) Flow cytometry analysis of GFP fluorescence in transfected Prdx6 null PMVEC. Mock transfected cells (left panel) and WT GFP-Prdx6 transfected cells (right panel) were incubated for 72 h, and were then harvested for flow cytometry analysis. (C) Transfection evaluated by western blot. Prdx6 null cells were transfected with different pGFP-Prdx6 constructs and incubated for 72 h. The expression of GFP-Prdx6 proteins was analyzed by Western blot. Lane 1: Vector; Lane 2: WT Prdx6; Lane 3: S32A; Lane 4: H26A; Lane 5: D140A; Lane 6: C47S; Lane 7: S32A/C47S; Lane 8: D140A/C47S; Lane 9: D31A. All transfections were with a plasmid expressing a fusion protein with GFP. Results are representative of three experiments. (To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article at www.liebertonline.com/ars).

Compared with WT PMVEC, Prdx6 null cells showed little PLA2 activity or 1-palmitoyl-2-linoleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine hydroperoxide (PCOOH) peroxidase activity, while ∼50% of peroxidase activity with H2O2 or tBOOH substrate was preserved (Table 2). This latter activity presumably reflects peroxide reduction by other enzymes in the cells such as the GSH peroxidases. Transfection of Prdx6 null cells with a WT pGFP-Prdx6 construct restored PLA2 activity and peroxidase activities with H2O2, tBOOH, or PCOOH substrates (Table 2). We next evaluated constructs that resulted in proteins expressing one or the other activities of Prdx6 through mutations of C47, the active center for peroxidase activity, and S32, H26, and D140, the PLA2 catalytic triad (4, 27). As predicted, the GFP-C47S mutation restored PLA2 activity but not peroxidase activities. In addition, as expected, the GFP-S32A and GFP-H26A mutations fully restored peroxidase activity with H2O2 or tBOOH, but failed to restore PLA2 activity; peroxidase activity was only modestly increased (<30%) with PCOOH as substrate, presumably reflecting the decreased binding of the oxidized phospholipid substrate to S32 and H26 mutated Prdx6 (27). Transfection with GFP-D140A also failed to restore PLA2 activity but did restore both H2O2 and PCOOH peroxidase activities, as this mutation does not affect phospholipid binding (27). Transfection of Prdx6 null cells with GFP-D31A, a “control” mutation, restored all activities of Prdx6, while transfection with double mutant constructs (GFP-S32A/C47S and GFP-D140A/C47S) did not restore either activity. The plasmids were made in the pGFP-C1 vector with a strong cytomegalovirus promoter that can drive the overexpression of WT or mutated Prdx6 in the transfected cells. The overexpression of Prdx6 protein in the transfected cells can account for the relatively high enzymatic activities in the cell preparations even though the transfection efficiencies were only about 50% (Table 2).

Table 2.

Peroxidase and Phospholipase A2 Activities for Peroxiredoxin 6 Null Pulmonary Microvascular Endothelial Cells Transfected with Various pGFP-Peroxiredoxin 6 Constructs

| Sample | PLA2 activity (nmol/h/mg protein) | Peroxidase activity (nmol/min/mg protein) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. No transfection: | % | H2O2 | % | tBOOH | % | PCOOH | % | |

| Wild type cells | 9.28±0.52 | 100 | 14.8±2.21 | 100 | 12.2±1.94 | 100 | 13.6±1.58 | 100 |

| Prdx6 null cells | 0.14±0.08a | 2 | 7.37±0.95a | 50 | 5.21±1.31a | 43 | 1.21±1.54a | 9 |

| B. Transfected with: | ||||||||

| C1 vector | 0.61±0.33a | 7 | 7.21±0.85a | 49 | ND | 1.02±0.91a | 7 | |

| Wild type | 8.66±0.42 | 93 | 14.6±1.42 | 99 | 12.0±1.09 | 98 | 13.1±1.53 | 96 |

| D31A | 7.96±0.18 | 86 | 12.9±2.47 | 87 | ND | 12.0±1.08 | 88 | |

| S32A | 0.00±0.27a | 0 | 12.2±1.42 | 82 | 10.7±2.19 | 84 | 3.74±1.07a,b | 27 |

| H26A | 0.15±0.07a | 2 | 13.8±3.45 | 93 | ND | 3.98±0.73a,b | 29 | |

| D140A | 0.00±0.31a | 0 | 14.1±1.02 | 93 | ND | 11.6±1.61 | 85 | |

| C47S | 5.99±0.28a,b | 65 | 7.65±0.86a | 52 | ND | 0.61±0.69a | 4 | |

| S32A/C47S | 0.26±0.10a | 3 | 8.29±1.05a | 56 | ND | 1.25±1.27a | 9 | |

| D140A/C47S | 0.25±0.02a | 3 | 7.75±1.04a | 52 | ND | 0.73±0.87a | 5 | |

All transfections were with a plasmid expressing a fusion protein with GFP. Data are expressed as mean±SE (n=3); the % column indicates % of wild type for the mean values.

p<0.05 compared with awild-type cells or bPrdx6 null cells.

GFP, green fluorescent protein; ND, not determined; SE, standard error.

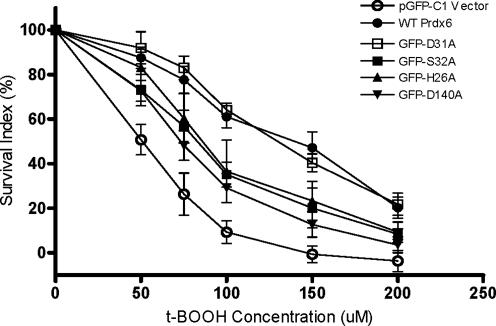

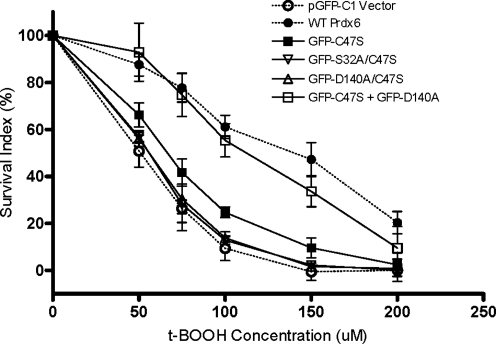

Both peroxidase and PLA2 activities of Prdx6 play a role in its protection against peroxidative stress

To determine the effects of Prdx6 mutants in response to peroxidative stress, transfected Prdx6 null cells were exposed to varying concentrations of tBOOH (50–200 μM), and cell survival was determined. The survival rate for Prdx6 null cells transfected with the WT construct was significantly higher than that of cells transfected with pGFP-C1 empty vector (Fig. 4). The LD50 of tBOOH for the WT pGFP-Prdx6 construct transfected group was ∼2.8-fold higher than the LD50 for the pGFP-C1 (vector only) transfected group (Fig. 4, and Table 3). As another control, transfection of cells with pGFP-D31A, a mutant construct that preserved both activities of Prdx6, also fully rescued cells from peroxidative stress (Fig. 4, Table 3). We then evaluated Prdx6 mutant constructs that expressed peroxidase activity but not PLA2 activity (GFP-S32A, GFP-H26A, and GFP-D140A). Transfection with these constructs increased survival rates in tBOOH-treated Prdx6 null cells compared with pGFP-C1 vector alone, but the rescue was only partial as compared with the WT or D31A construct (Fig. 4, Table 3). There was no significant difference in the ability to rescue cells for these latter three mutants. These mutants expressed the same activity with H2O2 substrate although they differ in their peroxidase activity with PCOOH (Table 2). These results suggest that the ability to reduce the concentration of the stressor, tBOOH, rather than the peroxidized phospholipid has a major role in ameliorating injury in this model of oxidative stress.

FIG. 4.

Rescue of Prdx6 null PMVEC by WT Prdx6, D31A mutant that has normal Prdx6 activities, or mutants expressing peroxidase activity only. Prdx6 null cells were co-transfected with different GFP-Prdx6 mutants and pSEAP2-Control vector for 72 h, and then treated with the indicated concentrations of tBOOH for 24 h. The survival rates were measured by MTT assay. The survival index was calculated as described in Methods section. Data are expressed as mean±SE (n>3).

Table 3.

Dose of Tert-Butyl Hydroperoxide for 50% Lethality of Peroxiredoxin 6 Null Pulmonary Microvascular Endothelial Cells Transfected with Various Peroxiredoxin 6 Constructs

| Transfection with | LD50 (μM) | % increase vs. control (mean) |

|---|---|---|

| C1 vector (control) | 50.1±6.0a | — |

| Wild type Prdx6 | 139±15.5 | 177 |

| D31A | 130±6.7 | 159 |

| S32A | 82.1±7.2a,b | 64 |

| H26A | 87.5±13.6a,b | 75 |

| D140A | 74.3±5.8a,b | 48 |

| C47S | 66.7±5.5a,b | 33 |

| S32A/C47S | 54.8±0.8a | 9 |

| D140A/C47S | 54.2±1.5a | 8 |

| C47S + D140A | 111±13.6 | 122 |

All transfections were performed with a plasmid expressing a fusion protein with GFP. Data are expressed as mean±SE. (n>3).

p<0.05 compared with awild-type Prdx6 or bC1 vector (control) transfected groups.

LD50, lethal dose for 50% of cells.

We next evaluated transfected mouse PMVEC that express the PLA2 activity of Prdx6 but not the peroxidase activity. Transfection with the pGFP-C47S construct significantly increased survival rates in tBOOH-treated Prdx6 null cells compared with pGFP-C1 vector indicating that the PLA2 activity plays an important role in cell survival (Fig. 5, Table 3). The partial increase in survival with the C47S construct was not seen on transfection with double mutants S32A/C47S or D140A/C47S, which do not express either activity of Prdx6 (Fig. 5, Table 3), supporting a role for the PLA2 activity in cytoprotection.

FIG. 5.

Comparison of survival rates for Prdx6 null cells transfected with plasmids to express Prdx6 without peroxidase activity (C47S), Prdx6 without peroxidase and PLA2 activities (S32A/C47S, D140A/C47S), or with two different plasmids, each expressing one of the two activities (C47S plus D140A). Cells were transfected and evaluated for survival as described in Fig. 4. Data are expressed as mean±SE (n>3). The dashed lines indicate the WT and control vector transfection data from Fig. 4.

Restoring both peroxidase and PLA2 activities by co-transfection with pGFP-C47S and pGFP-D140A fully rescued cells from peroxidative stress

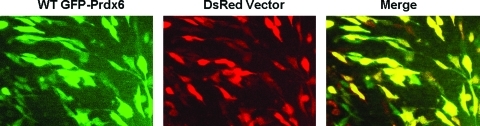

Since the results indicate that both peroxidase and PLA2 activities play a role in the antioxidant function of Prdx6, we questioned whether the two activities are coupled and have to be performed by the same enzyme molecule or whether restoring each function using a different molecule is sufficient. This issue was approached through co-transfection with two constructs, each expressing only one of the two activities. It is generally accepted that incubation with two different plasmids results in both being delivered into those cells that are transfected (48); that is, a cell is either transfected (by both) or not at all. To test this in Prdx6 null PMVEC, cells were co-transfected with WT GFP-Prdx6 and DsRed empty vector and evaluated by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 6). The co-localization (indicated by yellow color) of the two different fluorophores indicates that 89.2%±3.1% of transfected cells received both plasmids. Co-transfection of Prdx6 null cells with the pGFP-D140A construct expressing only the peroxidase activity plus the pGFP-C47S construct expressing only the PLA2 activity rescued cells nearly as well as the WT construct (Fig. 5, Table 2). This result indicates that restoring each function using a different molecule is sufficient for the full protection afforded by Prdx6. Thus, the two enzymatic activities of Prdx6 act independently in protecting cells from peroxidative stress and together account for the protection afforded by the WT construct.

FIG. 6.

Efficiency of co-transfection of Prdx6 null PMVEC. Expression of GFP fluorescence and DsRed fluorescence in Prdx6 null PMVEC co-transfected with WT GFP-Prdx6 and DsRed empty vector. The yellow fluorescence in the merged image shows co-localization of GFP and DsRed indicating co-transfected cells. (To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article at www.liebertonline.com/ars).

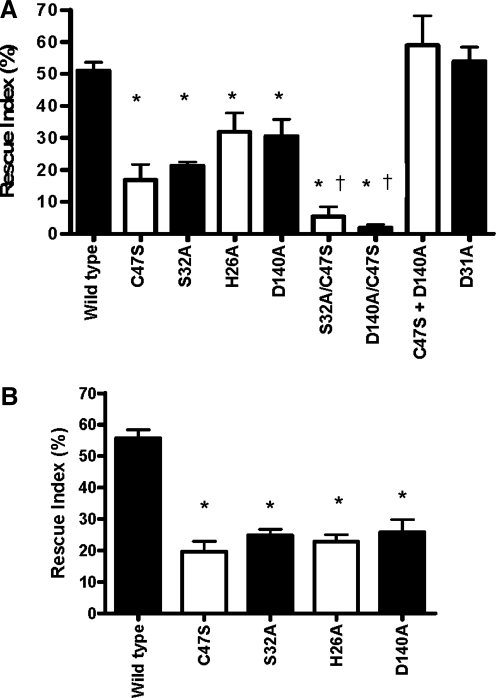

MTT versus neutral red assays for cell survival

The results described so far were obtained with the MTT assay. The basis for this assay is cell metabolism. The neutral red uptake assay that reflects cellular dye uptake and retention was used to confirm that the results of the MTT assay reflect cell survival. The rescue index for cells treated with 100 μM tBOOH after transfection with WT Prdx6 was approximately 50% by both assays (Fig. 7A, B). Likewise, rescue from peroxidative stress by the four single mutant constructs (C47S, S32A, H26A, and D140A) was not significantly different as assessed by the two assays (Fig. 7A, B).

FIG. 7.

Rescue index for pGFP-Prdx6 constructs against 100 μM tBOOH induced peroxidative stress. To calculate rescue index, the survival rate for cells transfected with C1 vector was subtracted from survival rates for the cells transfected with Prdx6 constructs, then normalized to the transfection efficiencies indicated by secreted alkaline phosphatase activities. All transfections were performed with a plasmid expressing a fusion protein with GFP. Data are expressed as mean±SE (n≥3). (A) Rescue index measured by MTT assay (calculated from the experiments shown in Figs. 4 and 5). (B) Rescue index measured by the neutral red uptake assay. *p<0.05 compared with WT Prdx6. †p<0.05 compared with all single mutant constructs.

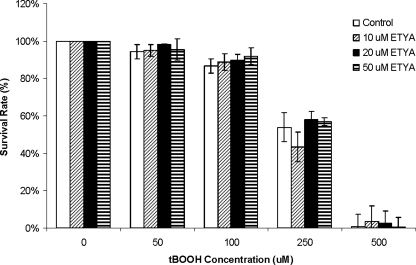

Inhibition of eicosanoid biosynthesis by eicosatetraynoic acid did not affect peroxidative stress-induced cell injury in PMVEC

A possible mechanism for the protective effect of the PLA2 activity of Prdx6 could be through the release of arachidonic acid for eicosanoid synthesis. To investigate this aspect, WT PMVEC were treated with eicosatetraynoic acid (ETYA), a nonspecific inhibitor of cyclooxygenases and lipoxygenases, and cell survival in response to tBOOH was evaluated by MTT assay. Pretreatment with 10–50 μM ETYA did not affect the survival rates of WT cells co-treated with various concentrations of tBOOH (Fig. 8).

FIG. 8.

Effect of treatment with eicosatetraynoic acid (ETYA) on survival of WT PMVEC when subjected to peroxidative stress. WT PMVEC were co-treated with 0, 10, 20, or 50 μM ETYA and indicated concentrations of tBOOH for 24 h. Data are expressed as mean±SE (n=3).

Discussion

Lungs usually manifest the highest concentrations of tissue oxygen of any organ and are particularly at risk for oxidative insults from extrinsic or intrinsic sources (47). Oxidation of cellular DNA, proteins, and lipids associated with oxidative stress may induce apoptosis or necrosis of alveolar epithelial and vascular endothelial cells and may result in damage/destruction of the cellular barrier function, alveolar edema, and intraalveolar hemorrhage that are characteristic of acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome (25, 47). Thus, understanding the mechanisms for oxidative injury and searching for therapeutic strategies to prevent damage to the lung alveolar cells are important.

Prdx6, a unique bifunctional enzyme, has been demonstrated as playing an important antioxidant role in the lung, liver, heart, lens epithelium, human diploid fibroblasts, and during pregnancy (7, 9, 10, 18, 23, 24, 32, 42–46). Prdx6 is a cytosolic protein that is also present in lysosomes in lung epithelial cells and alveolar macrophages, as well as in lung lamellar bodies (11). Prdx6 has been shown as translocating from cytosol to the cell plasma membrane associated with its phosphorylation in mouse PMVEC (3) or after plasma membrane oxidation in A549 cells (28). This behavior in cells reflects the in vitro findings that Prdx6 binds to oxidized phospholipids or after its phosphorylation binds to reduced phospholipids (28). Prdx6 expresses both GSH peroxidase activity catalyzed by Cys47 and PLA2 activity catalyzed by a triad (Ser32–His26–Asp 140), respectively. It has been generally assumed that the peroxidase activity of Prdx6 represents the main mechanism for its antioxidant function through its ability to remove oxidizing hydroperoxides and to repair peroxidized membrane phospholipids. However, data supporting this assumption are lacking. In the present study, we investigated, through the use of rescue strategies, whether the antioxidant effect of Prdx6 in PMVECs was solely dependent on its peroxidase activity, or also required its PLA2 activity.

In agreement with published studies using other cell types (29, 34, 42), our results show that Prdx6 plays an important antioxidant role in PMVEC. Prdx6 null PMVEC were more susceptible to tBOOH-induced peroxidative injury, and the LD50 of tBOOH in WT cells was threefold greater than that in Prdx6 null cells. MJ33, a transition state phospholipid analog, is an active site-directed competitive inhibitor of acidic Ca2+-independent lung PLA2 (aiPLA2, the PLA2 activity of Prdx6) (14, 19). Previous work in our laboratory has shown that MJ33 can inhibit the PLA2 activity of Prdx6 in rat lung homogenates by ∼75% (12), and a similar inhibition of PMVEC was confirmed in the present study. Inhibition of Prdx6 PLA2 activity by MJ33 treatment exacerbated tBOOH-induced cell death in WT PMVEC, but did not further sensitize Prdx6 null cells to peroxidative stress, suggesting a role for PLA2 activity in antioxidant defense by Prdx6. This previously unrecognized role of Prdx6 PLA2 activity was confirmed by rescue studies. With exposure to varying concentrations of tBOOH, the survival rate for Prdx6 null cells transfected with WT pGFP-Prdx6 construct was significantly higher than that of cells transfected with pGFP-C1 vector, and the LD50 was increased about 2.8-fold, similar to the relative LD50 ratio in WT cells compared with untransfected Prdx6 null cells. Prdx6 mutant constructs expressing either peroxidase activity alone (GFP-S32A, GFP-H26A, and GFP-D140A) or PLA2 activity alone (GFP-C47S) each partially rescued the Prdx6 WT phenotype, suggesting that both activities are important for the antioxidant role of the protein. The importance of both activities was confirmed by the ability of the GFP-D31A mutant (expressing both activities) or the combination of constructs (pGFP-D140A/pGFP-C47S) that together express both activities to fully rescue cells from peroxidative stress on transfection. Of note, other members of the mammalian peroxiredoxin family express peroxidase but not PLA2 activity; further, they have not been demonstrated as reducing PCOOH (12). Thus, these other peroxiredoxins may be less effective than Prdx6 in protecting against oxidant stress, although direct comparisons have not yet been reported.

Peroxidation of phospholipids, especially those with an unsaturated fatty acid in the sn-2 position, by reactive oxygen species is a major threat to cellular integrity. Prdx6 is the only known enzyme, other than GSH peroxidase 4 (GPx4), with the ability to reduce phospholipid hydroperoxides by its peroxidase activity (11, 16). GPx4 is expressed at only a low level in the lung, and the ability to reduce PCOOH by lung homogenate is essentially lost by “knock-out” of Prdx6 (24). The ability of the phospholipid hydroperoxide peroxidase activity of Prdx6 to function in the repair of peroxidized membranes during oxidative stress is considered to be a major mechanism for its antioxidant effect (24). However, removal of tBOOH rather than repair of oxidized phospholipids appears to be the major mechanism for antioxidant defense by the peroxidase activity in the present study.

The present results also indicate that loss of PLA2 activity also affected the ability of Prdx6 to perform its antioxidant function. Prdx6 PLA2 activity can catalyze hydrolysis of the peroxidized acyl group at the sn-2 position of glycerophospholipids producing the peroxidized free fatty acid and lyso-phospholipid (1, 11, 28). Although Prdx6 PLA2 activity with reduced phospholipid substrate is low at pH 7, this activity increases dramatically in the presence of oxidized phospholipid (28). Hydrolysis of PCOOH by PLA2 activity can be followed by the reacylation of the lysophospholipid with a fatty acid to regenerate a nonoxidized phospholipid. This mechanism has been suggested as a major pathway for membrane repair (39), although a theoretical analysis indicated that the direct reduction of a peroxidized phospholipid is much more efficient than the deacylation-reacylation pathway (49). Thus, the PLA2 activity of Prdx6 may work together with acyltransferases as a pathway that is alternative to peroxidase activity to reduce peroxidized phospholipids for membrane repair. This alternate pathway may assume greater importance in the absence of a peroxidase activity that can reduce oxidized phospholipids.

Another possibility for the protective effect of the PLA2 activity of Prdx6 may be through the release of arachidonic acid, the substrate for eicosanoid biosynthesis, from membrane phospholipids. It has been shown that prostacyclin (PGI2) analogs have protective functions against endothelial damage, and can increase the expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and nitric oxide formation to protect cells against oxidative stress (20, 30, 33). This mechanism is unlikely in the present study, as the inhibition of eicosanoid synthesis by ETYA did not alter peroxidative stress-induced cell injury. Further, Prdx6-mediated hydrolysis (PLA2 activity) does not exhibit preference for arachidonate-containing phospholipids (1, 22), so this activity is unlikely to result in an increase of cellular PGI2. Thus, eicosanoid synthesis does not play an important role in the cytoprotective effect of Prdx6 with oxidant stress.

Although removal of oxidants and repair of peroxidized membrane phospholipids during oxidative stress appear to be the most likely pathways for the protective effect of Prdx6 in oxidant stress, other mechanisms cannot be excluded. For example, Prdx6 was found to translocate to mitochondria and protect against mitochondrial dysfunction and liver injury in a mouse model of ischemia-reperfusion (9). This effect was possibly due to the interaction of Prdx6 with complex I of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. As another mechanism, Prdx6 interfered with the TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)-induced death-inducing signaling complex formation in TRAIL-resistant metastatic cancer cells, and protected these cells from extrinsic apoptosis (5). This effect was related to Prdx6 binding to caspase 8 and caspase 10. Since oxidative stress mainly stimulates intrinsic apoptosis, this mechanism for Prdx6 function may not be pertinent to the present studies. However, neither of these other mechanisms has been shown to depend on the peroxidase or PLA2 activities of Prdx6, which, based on our mutation studies, account entirely for the antioxidant role of the protein. Thus, it remains unclear whether any of these alternative pathways may contribute to the protective effect of Prdx6 in the tBOOH model of oxidative stress.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and antibodies

1-palmitoyl-2-linoleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (PLPC) was obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc. (Alabaster, AL). MJ33, soybean lipoxidase V, GSH, GSH reductase, NADPH, hydrogen peroxide, tBOOH, MTT (3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide), neutral red solution, and the polyclonal anti-actin antibody were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). ETYA was from Cayman (Ann Arbor, MI). The monoclonal anti-GFP antibody and the pSEAP2, pGFP, and DsRed vectors were from Takara Bio, Clontech Division (Mountain View, CA).

Isolation and culture of mouse PMVECs

PMVEC were isolated from the lungs of WT and Prdx6-null mice as previously described (8, 31). Briefly, freshly harvested mouse lungs were treated with collagenase, followed by isolation of cells through incubation with monoclonal antibody that recognizes platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule (PECAM) (BD Biosciences Pharmingen, Palo Alto, CA) and Dynabeads (Dynal, Oslo, Norway) coated with sheep anti-rat IgG (4). PMVEC were propagated in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, nonessential amino acids, penicillin/streptomycin, and Plasmocin (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA). The endothelial phenotype of the preparation was routinely confirmed by cellular uptake of acetylated low-density lipoprotein labeled with 1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate and by immunostaining for PECAM. Cells at passage 8–13 were used for the studies.

Flow cytometry analysis

Flow cytometry analysis of GFP expression to determine the transfection efficiencies for Prdx6 null MPVEC was performed with the 18-color LSRII system (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) using FACSDiva digital acquisition electronics and software. Cells were gated based on forward and side laser light scatter. GFP fluorescence was analyzed in the FL1 channel.

Preparation of oxidized phospholipid substrate

Phosphatidylcholine hydroperoxide (PCOOH) was prepared by controlled oxidation of PLPC as previously described (16) with minor modification. Briefly, the substrate in 0.2 M borate buffer (pH 9.0) containing 10 mM deoxycholate was incubated with soybean lipoxidase V for 30 min at 37°C. The phospholipids were extracted by the method of Bligh and Dyer (2). The concentration of PCOOH was determined by UV detection at 234 nm for conjugated dienes.

Peroxidase enzymatic activity assay

Peroxidase activity in lysed cells was measured as previously described (16) with minor modification. Briefly, PMVEC were lysed in buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, and 1% NP-40. The activity was assayed using H2O2, tBOOH, or PCOOH as substrate by measuring the consumption of NADPH in the presence of GSH and GSH reductase. The reaction buffer (3 ml) was 50 mM Tris–HC1 (pH 8.0) containing 2 mM NaN3, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.025 mM NADPH, 0.66 mM GSH, and 0.23 units/ml GSH reductase. The cell lysate in buffer was pre-incubated for 5 min with continuous stirring. Fluorescence was continuously recorded at 460 nm (340 nm excitation) using a PTI spectrofluorometer (Photon Technology International, Birmingham, NJ). After a steady baseline had been achieved, the reaction was started by the addition of substrate (either 7.6 μM H2O2, 5.3 μM tBOOH, or 50 μM PCOOH), and the change in fluorescence was recorded for 5–10 min. The PCOOH substrate was dispersed in 0.1% Triton X-100. The rate of reaction was calculated from the linear rate of NADPH oxidation and was corrected for the relatively small baseline nonenzymatic oxidation of NADPH. Enzymatic activity was expressed as nmol NADPH oxidized/min/mg protein.

PLA2 enzymatic activity assay

To measure PLA2 activity, lysed PMVEC were incubated with radiolabeled liposomes as previously described (13, 15). Unilamellar liposomes (∼100 μm in diameter) consisting of 1-palmitoyl, 2-[9, 10 3H]-palmitoyl, sn-glycero-3 phosphocholine ([3H]-DPPC), egg phosphatidyl-choline, phosphatidylglycerol, and cholesterol (0.5, 0.25, 0.1, 0.15 mol fraction, respectively) were prepared by extrusion through a membrane under pressure. Lysates were incubated in a calcium-free buffer (40 mM sodium acetate, 5 mM ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid) at pH 4.0 for 1 h. The radiolabeled free fatty acid product was extracted with hexane-ether 1:1 (v/v), resolved on Whatman LK5 silica gel 105A thin-layer chromatography plates using a hexane-ether-acetic acid solvent system, and analyzed by scintillation counting (12, 14). To measure the effect of MJ33 on PLA2 activity, WT PMVEC were incubated with the inhibitor for 30 min, and the cells were harvested for PLA2 activity assay.

Western blotting

For protein analysis, PMVEC were lysed by lysis buffer (1 M Tris.HCl pH 8.0, 5 M NaCl, and 1% NP-40) and separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Western blot analysis was performed using the two-color Odyssey LI-COR (Lincoln, NE) technique as previously described (31). The secondary antibodies IrDye 680 goat anti-rabbit IgG and IrDye 800 goat anti-mouse IgG (Rockland, Gilbertsville, PA) were used for imaging in the red 700 nm and green 800 nm channels, respectively. Blots were scanned by the Odyssey two color scanner, and the scanned images were converted to grayscale.

DNA constructs and site-directed mutagenesis for mutant Prdx6

The mammalian expression plasmid encoding NH2-terminal GFP-tagged full-length rat Prdx6 (GFP-Prdx6) made in the pGFP-C1 vector (Takara Bio) has been previously described (29, 40). Site-directed mutations were inserted using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, Santa Clara, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol using the indicated primer pairs. Separate constructs were generated for WT Prdx6, for S32, H26, D140, or D31 mutated Prdx6 substituted by alanine, and for C47 substituted by serine. All constructs are based on the sequence for rat Prdx6 (22). The primer sets for S32A and H26A have been previously described (40). The primer sets for C47S, D140A, and D31A were as follows: C47S: 5′-GGGACTTTACCCCAGTGAGCACCA CAGAACTTGGCAGAGC-3′ and 5′-GCTCTGCCAAGTTCT GTGGTGCTCACTGGGGTAAAGTCCC-3′; D140A: 5′-GTG GTATTCATTTTTGGCCCTGCCAAGAAACTAAAACTGTC CATCC-3′ and 5′-GGATGGACAGTTTTAGTTTCTTGGCAG GGCCAAAAATGAATACCAC-3′; D31A: 5′-GCTTCCACG ATTTCCTAGGAGCTTCATGGGGCATTCTCTTTTCC-3′ and 5′-GGAAAAGAGAATGCCCCATGAAGCTCCTAGGAAA TCGTGGAAGC-3′. Mutated Prdx6 sequences were analyzed and confirmed by the DNA sequencing facility at the University of Pennsylvania.

Cell transfection

For transfection experiments, PMVEC from Prdx6 null mice were grown to 70% confluence, and ∼1.8×106 cells were co-transfected with 4 μg pGFP-Prdx6 plasmid and 0.5 μg pSEAP2-Control vector by the Amaxa Nucleofector system using the Basic Endothelial Nucleofector Kit (Lonza Group, Basel, Switzerland) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Approximately 80% of the cells survive this procedure. In some experiments, cells were co-transfected with WT GFP-Prdx6 and DsRed empty vector. After electroporation, cells were cultured for 72 h before experiments.

Secreted alkaline phosphatase reporter gene activity assay

pSEAP2-Control vector that expresses a secreted form of human placental alkaline phosphatase was co-transfected into the Prdx6 null cells together with pGFP-Prdx6 plasmids as an internal control for the determination of transfection efficiency (6). After incubation for 72 h, samples of medium were taken to assay for secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) activity using the Great EscAPe™ SEAP Chemiluminescence kit (Takara Bio) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The SEAP activity levels were used to calculate the relative transfection efficiencies.

MTT assay

MTT was used to assay cell survival. MTT was dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline at 5 mg/ml. PMVEC were incubated with MTT at a final concentration of 0.1 mg/ml in the culture media at 37°C for 3 h. Cells were then solubilized in dimethyl sulfoxide for 30 min, and absorbance was determined at 550 nm. The formation of dark blue formazan products indicates metabolizing (living) cells. Survival rates were calculated by normalization to the corresponding untreated controls. A survival index was calculated as survival rate divided by transfection efficiency. For rescue experiments, a rescue index was calculated by subtracting the survival rate for the cells transfected with the vector alone and normalizing this “corrected” survival rate to the value for transfection efficiency. Survival rate, survival index, and rescue index are expressed as a percentage.

Neutral red uptake assay

The neutral red uptake assay with minor modification was used for cell survival studies (37). PMVEC were incubated with neutral red at a final concentration of 50 μg/ml in the culture media at 37°C for 3 h. Cells were then destained with 50% ethanol solution containing 0.5% glacial acetic acid for 15 min. Neutral red concentration in the lysate indicating uptake by live cells was quantified by the absorbance determined at 550 nm. The survival rate and a rescue index were calculated as described for the MTT assay.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as means±standard error for three or more independent experiments. Significance was determined using analysis of variance with a post hoc multiple comparison Student-Newman-Keuls test or independent Student's t-test, and the level of statistical significance was defined as p<0.05.

Abbreviations Used

- ETYA

eicosatetraynoic acid

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- GSH

glutathione

- LD50

lethal dose for 50%

- MJ33

1-hexadecyl-3-trifluoroethylglycero-sn-2-phosphomethanol

- MTT

3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2.5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- PCOOH

1-palmitoyl-2-linoleoyl-sn-glycero-3 phosphocholine hydroperoxide

- PECAM

platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule

- PGI2

prostacyclin

- PLA2

phospholipase A2

- PLPC

1-palmitoyl-2-linoleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- PMVEC

pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells

- Prdx6

peroxiredoxin 6

- SEAP

secreted alkaline phosphatase

- tBOOH

tert-butyl hydroperoxide

- TRAIL

TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand

- WT

wild-type

Acknowledgments

This work has been presented in part at the Experimental Biology meeting in 2010 (Anaheim, CA) and 2011 (Washington, DC). The authors thank Kris DeBolt for endothelial cell isolation, Elena M. Sorokina for providing several mutant constructs, Tea Shuvaeva for peroxidase activity assays, and Tatyana N. Milovanova and Charles H. Pletcher for assistance with flow cytometry analysis. This work was supported by HL P01-75587 from the National Institutes of Health.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Akiba S. Dodia C. Chen X. Fisher AB. Characterization of acidic Ca(2+)-independent phospholipase A2 of bovine lung. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 1998;120:393–404. doi: 10.1016/s0305-0491(98)10046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bligh EG. Dyer WJ. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chatterjee S. Feinstein SI. Dodia C. Sorokina E. Lien YC. Nguyen S. Debolt K. Speicher D. Fisher AB. Peroxiredoxin 6 phosphorylation and subsequent phospholipase A2 activity are required for agonist-mediated activation of NADPH oxidase in mouse pulmonary microvascular endothelium and alveolar macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:11696–11706. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.206623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen JW. Dodia C. Feinstein SI. Jain MK. Fisher AB. 1-Cys peroxiredoxin, a bifunctional enzyme with glutathione peroxidase and phospholipase A2 activities. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:28421–28427. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005073200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi H. Chang JW. Jung YK. Peroxiredoxin 6 interferes with TRAIL-induced death-inducing signaling complex formation by binding to death effector domain caspase. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:405–414. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chowdhury I. Mo Y. Gao L. Kazi A. Fisher AB. Feinstein SI. Oxidant stress stimulates expression of the human peroxiredoxin 6 gene by a transcriptional mechanism involving an antioxidant response element. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46:146–153. doi: 10.1016/reeradbiomed.2008.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dierick JF. Wenders F. Chainiaux F. Remacle J. Fisher AB. Toussaint O. Retrovirally mediated overexpression of peroxiredoxin VI increases the survival of WI-38 human diploid fibroblasts exposed to cytotoxic doses of tert-butylhydroperoxide and UVB. Biogerontology. 2003;4:125–131. doi: 10.1023/a:1024154024602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dong QG. Bernasconi S. Lostaglio S. De Calmanovici RW. Martin-Padura I. Breviario F. Garlanda C. Ramponi S. Mantovani A. Vecchi A. A general strategy for isolation of endothelial cells from murine tissues. Characterization of two endothelial cell lines from the murine lung and subcutaneous sponge implants. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:1599–1604. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.8.1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eismann T. Huber N. Shin T. Kuboki S. Galloway E. Wyder M. Edwards MJ. Greis KD. Shertzer HG. Fisher AB. Lentsch AB. Peroxiredoxin-6 protects against mitochondrial dysfunction and liver injury during ischemia-reperfusion in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;296:G266–G274. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90583.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fatma N. Kubo E. Sharma P. Beier DR. Singh DP. Impaired homeostasis and phenotypic abnormalities in Prdx6-/-mice lens epithelial cells by reactive oxygen species: increased expression and activation of TGFbeta. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12:734–750. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher AB. Peroxiredoxin 6: A bifunctional enzyme with glutathione peroxidase and phospholipase A2 activities. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15:831–844. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fisher AB. Dodia C. Lysosomal-type PLA2 and turnover of alveolar DPPC. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;280:L748–L754. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.4.L748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisher AB. Dodia C. Role of phospholipase A2 enzymes in degradation of dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine by granular pneumocytes. J Lipid Res. 1996;37:1057–1064. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fisher AB. Dodia C. Chander A. Jain M. A competitive inhibitor of phospholipase A2 decreases surfactant phosphatidylcholine degradation by the rat lung. Biochem J. 1992;288(Pt 2):407–411. doi: 10.1042/bj2880407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fisher AB. Dodia C. Feinstein SI. Ho YS. Altered lung phospholipid metabolism in mice with targeted deletion of lysosomal-type phospholipase A2. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:1248–1256. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400499-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fisher AB. Dodia C. Manevich Y. Chen JW. Feinstein SI. Phospholipid hydroperoxides are substrates for non-selenium glutathione peroxidase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21326–21334. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.30.21326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujii T. Fujii J. Taniguchi N. Augmented expression of peroxiredoxin VI in rat lung and kidney after birth implies an antioxidative role. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:218–225. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2001.01843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirota Y. Acar N. Tranguch S. Burnum KE. Xie H. Kodama A. Osuga Y. Ustunel I. Friedman DB. Caprioli RM. Daikoku T. Dey SK. Uterine FK506-binding protein 52 (FKBP52)-peroxiredoxin-6 (PRDX6) signaling protects pregnancy from overt oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:15577–15582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009324107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jain MK. Tao WJ. Rogers J. Arenson C. Eibl H. Yu BZ. Active-site-directed specific competitive inhibitors of phospholipase A2: novel transition-state analogues. Biochemistry. 1991;30:10256–10268. doi: 10.1021/bi00106a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawabe J. Ushikubi F. Hasebe N. Prostacyclin in vascular diseases. - Recent insights and future perspectives. Circ J. 2010;74:836–843. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-10-0195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim TS. Dodia C. Chen X. Hennigan BB. Jain M. Feinstein SI. Fisher AB. Cloning and expression of rat lung acidic Ca(2+)-independent PLA2 and its organ distribution. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:L750–L761. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.274.5.L750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim TS. Sundaresh CS. Feinstein SI. Dodia C. Skach WR. Jain MK. Nagase T. Seki N. Ishikawa K. Nomura N. Fisher AB. Identification of a human cDNA clone for lysosomal type Ca2+-independent phospholipase A2 and properties of the expressed protein. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:2542–2550. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.4.2542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kubo E. Fatma N. Akagi Y. Beier DR. Singh SP. Singh DP. TAT-mediated PRDX6 protein transduction protects against eye lens epithelial cell death and delays lens opacity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;294:C842–C855. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00540.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu G. Feinstein SI. Wang Y. Dodia C. Fisher D. Yu K. Ho YS. Fisher AB. Comparison of glutathione peroxidase 1 and peroxiredoxin 6 in protection against oxidative stress in the mouse lung. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;49:1172–1181. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lucas R. Verin AD. Black SM. Catravas JD. Regulators of endothelial and epithelial barrier integrity and function in acute lung injury. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;77:1763–1772. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manevich Y. Feinstein SI. Fisher AB. Activation of the antioxidant enzyme 1-CYS peroxiredoxin requires glutathionylation mediated by heterodimerization with pi GST. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3780–3785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400181101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manevich Y. Reddy KS. Shuvaeva T. Feinstein SI. Fisher AB. Structure and phospholipase function of peroxiredoxin 6: identification of the catalytic triad and its role in phospholipid substrate binding. J Lipid Res. 2007;48:2306–2318. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700299-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manevich Y. Shuvaeva T. Dodia C. Kazi A. Feinstein SI. Fisher AB. Binding of peroxiredoxin 6 to substrate determines differential phospholipid hydroperoxide peroxidase and phospholipase A(2) activities. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2009;485:139–149. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manevich Y. Sweitzer T. Pak JH. Feinstein SI. Muzykantov V. Fisher AB. 1-Cys peroxiredoxin overexpression protects cells against phospholipid peroxidation-mediated membrane damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:11599–11604. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182384499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsumoto K. Morishita R. Tomita N. Moriguchi A. Yamasaki K. Aoki M. Nakamura T. Higaki J. Ogihara T. Impaired endothelial dysfunction in diabetes mellitus rats was restored by oral administration of prostaglandin I2 analogue. J Endocrinol. 2002;175:217–223. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1750217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Milovanova T. Chatterjee S. Manevich Y. Kotelnikova I. Debolt K. Madesh M. Moore JS. Fisher AB. Lung endothelial cell proliferation with decreased shear stress is mediated by reactive oxygen species. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;290:C66–C76. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00094.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagy N. Malik G. Fisher AB. Das DK. Targeted disruption of peroxiredoxin 6 gene renders the heart vulnerable to ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H2636–H2640. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00399.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Niwano K. Arai M. Tomaru K. Uchiyama T. Ohyama Y. Kurabayashi M. Transcriptional stimulation of the eNOS gene by the stable prostacyclin analogue beraprost is mediated through cAMP-responsive element in vascular endothelial cells: close link between PGI2 signal and NO pathways. Circ Res. 2003;93:523–530. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000091336.55487.F7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pak JH. Manevich Y. Kim HS. Feinstein SI. Fisher AB. An antisense oligonucleotide to 1-cys peroxiredoxin causes lipid peroxidation and apoptosis in lung epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:49927–49934. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204222200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ralat LA. Manevich Y. Fisher AB. Colman RF. Direct evidence for the formation of a complex between 1-cysteine peroxiredoxin and glutathione S-transferase pi with activity changes in both enzymes. Biochemistry. 2006;45:360–372. doi: 10.1021/bi0520737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ralat LA. Misquitta SA. Manevich Y. Fisher AB. Colman RF. Characterization of the complex of glutathione S-transferase pi and 1-cysteine peroxiredoxin. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2008;474:109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Repetto G. del Peso A. Zurita JL. Neutral red uptake assay for the estimation of cell viability/cytotoxicity. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1125–1131. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rhee SG. Kang SW. Chang TS. Jeong W. Kim K. Peroxiredoxin, a novel family of peroxidases. IUBMB Life. 2001;52:35–41. doi: 10.1080/15216540252774748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sevanian A. Muakkassah-Kelly SF. Montestruque S. The influence of phospholipase A2 and glutathione peroxidase on the elimination of membrane lipid peroxides. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1983;223:441–452. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(83)90608-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sorokina EM. Feinstein SI. Milovanova TN. Fisher AB. Identification of the amino acid sequence that targets peroxiredoxin 6 to lysosome-like structures of lung epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;297:L871–L880. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00052.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang X. Phelan SA. Forsman-Semb K. Taylor EF. Petros C. Brown A. Lerner CP. Paigen B. Mice with targeted mutation of peroxiredoxin 6 develop normally but are susceptible to oxidative stress. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:25179–25190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302706200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang Y. Feinstein SI. Fisher AB. Peroxiredoxin 6 as an antioxidant enzyme: protection of lung alveolar epithelial type II cells from H2O2-induced oxidative stress. J Cell Biochem. 2008;104:1274–1285. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Y. Feinstein SI. Manevich Y. Ho YS. Fisher AB. Lung injury and mortality with hyperoxia are increased in peroxiredoxin 6 gene-targeted mice. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37:1736–1743. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang Y. Feinstein SI. Manevich Y. Ho YS. Fisher AB. Peroxiredoxin 6 gene-targeted mice show increased lung injury with paraquat-induced oxidative stress. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:229–237. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Y. Manevich Y. Feinstein SI. Fisher AB. Adenovirus-mediated transfer of the 1-cys peroxiredoxin gene to mouse lung protects against hyperoxic injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L1188–L1193. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00288.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Y. Phelan SA. Manevich Y. Feinstein SI. Fisher AB. Transgenic mice overexpressing peroxiredoxin 6 show increased resistance to lung injury in hyperoxia. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;34:481–486. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0333OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ward PA. Oxidative stress: acute and progressive lung injury. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1203:53–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xie ZL. Shao SL. Lv JW. Wang CH. Yuan CZ. Zhang WW. Xu XJ. Co-transfection and tandem transfection of HEK293A cells for overexpression and RNAi experiments. Cell Biol Int. 2011;35:187–192. doi: 10.1042/CBI20100470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhao L. Wang HP. Zhang HJ. Weydert CJ. Domann FE. Oberley LW. Buettner GR. L-PhGPx expression can be suppressed by antisense oligodeoxynucleotides. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2003;417:212–218. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(03)00342-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]