Abstract

Background:

The leaf ethanol extract of Harpephyllum caffrum Bernh. has evidenced medicinal value due to its hepatoprotective activity. It demonstrated inhibitory effects on test standard microbes approximated to 40% the potency of ofloxacin and fluconazole. The same extract evidenced in vitro cytotoxicity on human cell lines, liver carcinoma HEPG2, larynx carcinoma HEP2, and colon carcinoma HCT116 cell lines when compared to doxorubicin.

Materials and Methods:

Fractionation of the leaf ethanol extract led to the isolation of the polyphenols, ethyl gallate, and quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside, a hydrocarbon, hendecane, the fatty acid ester, methyl linoleate, and four triterpenoids, betulonic acid, 3-acetyl-methyl betulinate, lupenone and lupeol for the first time, in addition to the previously reported phenol acids and flavonoids, gallic acid, methyl gallate, quercetin, kaempferol, kaempferol-3-O-rhamnoside, kaempferol-3-O-galactoside, apigenin-7-O-glucoside, and quercetin-3-O-arabinoside.

Results:

The ethanol extract of the fruit of the genetically related Rhus coriaria L., known as sumac, afforded protocatechuic acid, isoquercitrin, and myricetin-3-O-α-L-rhamnoside from the fruits for the first time, in addition to the previously reported phenol acids and flavonoids, gallic acid, methyl gallate, kaempferol, and quercetin.

Conclusion:

The leaf ethanol extract of H. caffrum Bernh. exhibited variable anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and antipyretic activities, besides the hepatoprotective, in vitro cytotoxic and anti-microbial activities.

Keywords: Harpephyllum caffrum Bernh., hepatoprotective, polyphenolics, Rhus coriaria L., triterpenoids

INTRODUCTION

With great interest and enthusiasm, many scientific research centers around the world are exploring medicinal plants due to global belief of their efficacy in treatment. Members of the family Anacardiaceae[1] have long reputation in folk medicine for their nutritional value of edible fruits and seeds, and for variable ailments such as treatment of bowel complain, chronic wounds, pimples, boils, jaundice, hepatitis, and inflammatory conditions.[2] As part of on-going study of medicinal herbs, the closely related genera, Harpephyllum caffrum Bernh. and Rhus coriaria L. are subjected to biological testing in order to confirm the claimed herbal benefits of these drugs by different communities.[3–5] The bark of H. caffrum Bernh. is used to treat acne and eczema, and is usually applied in the form of facial saunas and skin washes.[5] Recent reports revealed that the aqueous and ethanol extracts of H. caffrum Bernh. from South Africa exhibited significant antibacterial and antifungal activities against certain microbial strains.[6] H. caffrum Bernh. has been introduced and cultivated in Egypt as an ornamental garden tree while R. coriaria L.(Sumac) fruits are imported and sold in the Egyptian herbal market as a desirable spice in many Arabic food recipes to impart flavor and aroma. The aqueous extract of Iranian R. coriaria L. fruits showed hepatoprotective activity against oxidative stress cytotoxicity[7] and antibacterial activity against Salmonella typhimurium.[8]

Research on evaluation of these plant extracts and their activities necessitates focusing on their crucial phytoconstituents, as well as, their toxicity if any. Previous phytochemical work on H. caffrum indicated a brief note on a tentative identification of afzelin, quercetin-3-O-β-arabinoside, apigenin-7-O-α-glucoside, kaempferol-3-O-β-galactoside, kaempferol, and quercetin.[9] H. caffrum stem bark extract was previously evaluated for the total polyphenol content and antioxidant activity.[10] Phenolic constituents of Sumac were dealt with in previous reports.[11,12] However, nothing could be traced on the phenolic constituents of sumac fruits marketed in Egypt.

There is an extensive body of the literature addressing the escalated distribution of hepatic diseases among the people in Egypt.[13,14] Since the liver is responsible for the breakdown and elimination of most toxic substances, the need for protecting the liver against poisons is a global health problem. Hepatoprotective herbal drugs can offer help by blocking absorption of toxins into liver cells and the formation of inflammatory substances that contribute to liver degeneration. The nutritional support that these plants can offer is indispensable in nowadays life.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant material

Samples of the leaves of H. caffrum Bernh. were obtained from trees growing in El Orman botanical garden, Giza, and identified by the Botany Department, Faculty of Science, Cairo University, Giza, Egypt. Samples of the fruits of Rhus coriaria L. were obtained from a herbalist shop in Cairo and identified as previously mentioned.[15] Samples of both plants are deposited at the Museum of the Pharmacognosy Department, Faculty of Pharmacy, Cairo University.

Material and apparatus for phytochemical study

Reference material: Flavonoids were obtained from E. Merck, Darmst-adt, Germany. solvent systems and spray reagents for chromatographic studies included pre-coated silica plates 60 GF254, cellulose plates (20×20 cm) from Fluka (Sigma-Aldrich chemicals-Germany) for thin layer chromatography (TLC), silica gel 60 for normal phase column chromatography (CC), polyamide (E-Merck Darmstadt, Germany), silica gel H for vacuum liquid chromatography (VLC) (E-Merck Darmstadt, Germany), and silica gel RP-18 (70-230 mesh) for reversed phase column chromatography were obtained from Fluka (Sigma-Aldrich chemicals, Germany). The following solvent systems were used for developing the chromatograms: S1 : n-hexane, S2 : n-hexane- chloroform (5:5) v/v, S3 : n- hexane- chloroform (9:1) v/v, S4 : hexane-ethyl acetate (6: 4) v/v, S5 : n-hexane-chloroform(7:3) v/v, S6 : benzene-ethyl acetate-formic acid (5.5:4.5:0.5) v/v/v, S7 : n-butanol-acetic acid- water(4: 1: 5) v/v/v, S8 : benzene-ethyl acetate-formic acid (5.5:4.5:1) v/v/v, and S9 : ethyl acetate-methanol- formic acid- water (8:2:0.5:1) v/v/v. Spots were visualized by spraying with the following spray reagents: I—p-anisaldehyde-sulfuric acid for triterpenoids, II—1% aluminium chloride spray reagent for flavonoids, III—ferric chloride spray reagent for phenolic compounds.[16]

Ultraviolet lamp (λmax =254 and 330 nm), Shimadzu, a product of Hanovia lamps for localization of spots on chromatograms. UV absorption spectra were determined on a Shimadzu UV-1650PC spectrophotometer in methanol and after addition of different shift reagents.

EI-MS were recorded with a Varian Mat 711, Finnigan mass SSQ 7000 Mass spectrometer, eV 70. IR spectra were observed as KBr discs on Schimadzu IR-435, PU-9712 infrared spectrophotometer.

1H-NMR(300MHz) and 13C-NMR (75 MHz) spectra were recorded on Jeol EX-300 MHz and Bruker AC-300 spectrometer operating at 300 (1H) and 75(13C) MHz in CDOD3 and CDCl3 as a solvent and chemical shifts were given in δ (ppm).

Extraction

The air-dried powdered leaves of H. caffrum (2 kg) were extracted by cold percolation with 95% ethanol (5 × 10 L) till exhaustion. The ethanol extract was evaporated under reduced pressure to give 350 g greenish brown semi-solid residue. 350 grams of the dried residue were suspended in distilled water and successively partitioned between n-hexane, chloroform, ethyl acetate, and n-butanol saturated with water. The solvent in each case was completely evaporated under reduced pressure to yield 11 g, 4 g, 9 g, and 3 g, respectively.

The dried powder (2.5 kg) of the fruits of Rhus coriaria L. were similarly treated to give 245 g. Successive partitioning between different solvents led to preparation of 35.9 g of n-hexane, 28.6 g of chloroform, 90 g of ethyl acetate, and 5.5 g of n-butanol saturated with water extractives.

Fractionation and isolation of the components of the n-hexane extractive of H. caffrum

The n-hexane extract was chosen for isolation of active compounds. 11 g of the n-hexane extract were chromatographed on a VLC column, 210 g silica gel (12.5 × 7 cm) using n-hexane, n-hexane-chloroform and chloroformethyl acetate mixtures. Fractions, 200 ml each, were collected and monitored by TLC. Similar fractions were pooled together to obtain four major fractions (A-D).

Fraction A (1.04 g), eluted with 100% n-hexane, was purified on a silica gel column using n -hexane as an eluent to obtain compound 1 (20 mg).

Fraction B (0.49 g), eluted with 15% chloroform in n-hexane, was purified on silica gel column using n-hexane-chloroform mixtures as an eluent to obtain compound 2 (40 mg).

Fraction C (1.02 g), eluted with 35% chloroform in n-hexane, was purified on silica gel column using n-hexane-chloroform mixtures as an eluent revealed two spots. Further rechromatography on successive silica gel columns using n-hexane-chloroform mixtures yielded two compounds 3 (20 mg)and 4 (40 mg) .

Fraction D (3.81 g), eluted with 60% chloroform in n-hexane, was subjected to chromatography on successive silica gel columns using n-hexane-chloroform mixtures to afford compounds 5 (60 mg) and 6 (50 mg).

Fractionation and isolation of the components of the ethyl acetate extractive of H. caffrum

Based on yield and chromatographic pattern, the ethyl acetate extract was selected for isolation of active compounds. 9 g of the ethyl acetate extract were chromatographed on a CC (100 g polyamide, 50 cm × 3 cm) using water and water-methanol mixtures. Fractions, 100 ml each, were collected and monitored by TLC. Similar fractions were pooled together to obtain four major fractions (I-IV). Fraction I (2 g), eluted with 10%, 20% methanol in water revealed the presence of three major spots.Further rechromatography using sephadex LH 20 and water- methanol in decreasing polarity as eluent led to the isolation of three phenolic compounds, 7 (90 mg), 8 (80 mg)and 9 (40 mg).

Fraction II (1.37 g), eluted with 40%-60% methanol in water, was further subjected to rechromatography on RP 18 silica column using water- methanol as eluent and resulted in separation of five compounds 10 (30 mg), 11 (50 mg), 12 (60 mg), 13 (50 mg), and 14 (30 mg). Fraction III (1.67 g), eluted with 90-100% methanol, was refractionated and repurified to yield compounds 15 (30 mg) and 16 (50 mg).

Fractionation and isolation of the components of the ethyl acetate extractive of R. coriaria

90 g of the ethyl acetate extractive of the fruits of R. coriaria were chromatographed on a VLC column (150 g silica gel, 30 cm × 4 cm) using n-hexane, n-hexane-chloroform, and chloroform-ethyl acetate mixtures. Similar fractions were pooled together to obtain four major fractions (a-d). Rechromatography on different stationary phases including sephadex LH20, and silica gel RP-18 led to isolation of compounds 15, 16 (from fraction a), 7, 8 (from fraction b), 17 (50 mg) (from fraction c), 18 (50 mg), and 19 (60 mg) (from fraction d) in a pure form.

Biological study

Preparation of the extracts

Ten g of the dried ethanol extract previously prepared was dissolved in distilled water containing few drops of Tween 80 to yield a concentration of 5% w/v. The leaf ethanol extract of H. caffrum was tested for its hepatoprotective, anti inflammatory, analgesic, and antipyretic activities.

Chemicals and kits

Carrageenan: Sigma Co.(0.1 ml of 1% solution, to induce inflammation), indomethacin: Epico, A.R.E. (20 mg/kg body weight [b. wt.], standard anti inflammatory), Brewers dry yeast: Rehab food company (1 ml/100 g b. wt. of 40% suspension by intramuscular injection to induce hyperthermia), paracetamol (Paramol): Misr, Mataria, Cairo (20 mg/kg b. wt., standard antipyretic), dipyron-metamizol (Novalgin): Hoechst Orient, Cairo (50 mg/kg b. wt., standard analgesic), carbon tetrachloride (Analar, El-Gomhoreya Co., Cairo, Egypt, for induction of liver damage (5 ml/kg of 25% CCl4 in liquid paraffin, IP), Silymarin (Sedico Pharmaceutical Co., 6 October City, Egypt, standard hepatoprotective drug (25 mg / kg b. wt.), biodiagnostic kits for assessment of serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alkaline phosphatase enzymes (ALP).

Experimental animals

Adult male albino rats (130-150 g) were obtained from the animal-breeding unit of National Research Center, El-Dokki, Giza, Egypt. All animals were fed on a standard laboratory diet under hygienic conditions and water supplied ad lb.

For testing the effect on the liver, 50 adult male albino rats were used and divided into five groups (each of 10). The leaf ethanol extract of H. caffrum of H. caffrum was tested for its hepatoprotective activity using silymarin as a reference drug. The tested extract was administered at a daily dose of 50, 75, and 100 mg/kg b. wt. for 1 month before induction of liver damage.[17] Administration of the tested solution was continued after liver damage for another 1 month.

For testing anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and antipyretic activities, animals, in each case, were divided into three groups, each of ten. The first group was considered as a control, the second was given the appropriate standard drug, and the third was administered 100 mg/kg b. wt of the tested extracts orally. Doses of the drugs were calculated and administered orally by gastric tube.[18]

Determination of median lethal dose (LD50)

LD50 of the ethanol extract was determined according to the reported procedures.[19]

Measurement of aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, and alkaline phosphatase enzymes serum levels

Serum levels of AST, ALT[20] and ALP enzymes[21] were measured in each group at zero time, after 1 month of receiving the tested drug, 72 h after induction of liver damage, and after 1 month of treatment with the tested samples.

Acute anti-inflammatory activity

The acute anti-inflammatory effect was determined according to the published procedures.[22] The percentage of edema inhibition (% of change) was calculated.

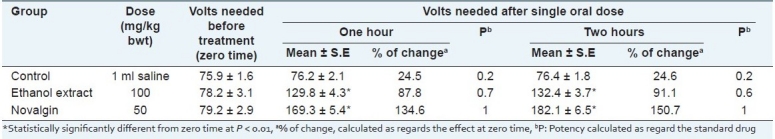

Analgesic effect

The analgesic effect was evaluated according to standard methods[23] by using electric current as a noxious stimulus where electrical stimulation was applied to the rat tail by means of 515 Master shocker (Lafayette Inst. Co.) using alternative current of 50 cycles/s for 0.2 s. The minimum voltage required for the animal to emit a cry was recorded after 1 and 2 h of oral administration of the tested dose. The percentage of change was calculated.

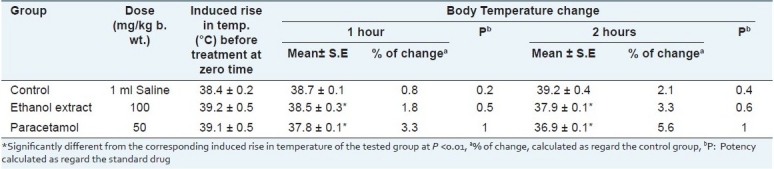

Antipyretic effect

The induced rise of temperature of rats was recorded at zero time and in the treated groups after one and two hours.[24] The percentage of change was calculated and the results are recorded.

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as mean ± SE and the statistical significance was evaluated by the Student's “t” test.[25]

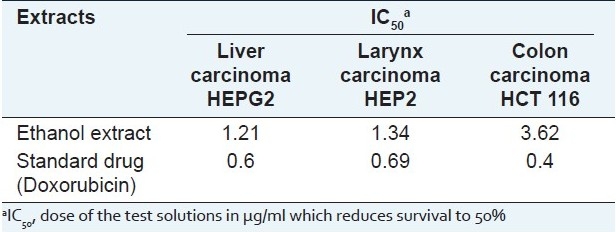

In vitro screening for cytotoxic activity

Human tumor cell lines: liver carcinoma (HEPG2), colon carcinoma (HCT116), and larynx carcinoma (HEP2) cell lines, maintained in the laboratory of Cancer Biology Department of National Cancer Institute, Cairo, Egypt were used. The ethanol extract at different concentrations (0-10 μg/ml) in DMSO were tested for cytotoxicity against the fore mentioned human tumor cell lines adopting sulforhodamine B stain (SRB) assay.[26] The relationship between surviving fractions and the extract concentration was plotted to get the survival curve of each tumor cell line after the application specific concentration. The results were compared to those of the standard cytotoxic drug, Doxorubicin (10 mg Adriamycin hydrochloride, in 5 ml IV injection, Pharmacia, Italy) at the same concentrations. The dose of the test solutions which reduces survival to 50% (IC50) was calculated.

Testing of the antimicrobial activity

The antimicrobial activity was performed against selected bacterial and fungal strains of standard properties. These were maintained in the Micro Analytical Center, Faculty of Science, Cairo University. The tested Gram positive bacteria were [Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6051, Streptococcus faecalis ATCC 19433 and Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 12600]. The Gram negative bacteria included [Escherichia coli ATCC 11775, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 10145 and Neisseria gonorrhea ATCC 19424], and fungi [Candida albicans ATCC 26555 and Aspergillus flavus]. Bacteria were grown on nutrient agar (Oxoid, England) and fungi on Sabouraud's glucose agar (Oxoid, England). The ethanol extract was tested against the selected strains at concentration of 20 mg/ml adopting the disc agar diffusion method.[27] Discs impregnated with Ofloxacin and Fluconazole were used as antibacterial and antifungal standards, respectively. Test solution was prepared by dissolving in DMSO at a concentration of 20 mg/ml; aliquots, 10 μl each were aseptically transferred into sterile discs of Whatman filter paper 8 mm diameter.

RESULTS

Column chromatographic fractionation of the n-hexane fraction of the ethanol leaf extract of H. caffrum allowed the isolation of six compounds (1-6) which were characterized through their physicochemical and spectral data.

Compound 1: Hendecane (20 mg, oily), soluble in hexane, negative test for sterol and/or triterpenes, Rf values 0.47 (S1) and 0.93 (S3). IR υmax KBrspectrum shows absorption peaks: 2920 and 2820 cm-1 (C-H), 1464,1460 cm-1 (-C-CH3) and 730,720 cm-1 for – (CH2)n, EI Mass (70 eV) m/z:156 (M+), 57 (100%). 1H-NMR (300 Hz CDCl3): 0.90 ppm (3H, t, J=6 Hz), terminal CH3 and 1.25 ppm [saturated alkyl chain, (-CH2-)n].

Compound 2: Methyl linoleate (40 mg, yellow oily), negative test for sterol and /or triterpenes. Rf values 0.17 (S1 ) and 0.60 (S3); IRυmax KBrspectrum shows absorption peaks: 2921, 2855 cm-1 (CH), 1742 cm-1 for ester carbonyl (C=O) and 1462, 880 cm-1 (-C=CH2) and (CH2) methylene vibration at 722 cm-1. EI Mass (70 eV) m/z: 294(M+), 263 (M+ -CH3-O), 287, 178, 164, 149, 95, 81, 67, 56, 41. 1H-NMR (300 Hz CDCl3): Showed signals at 0.88 ppm (3H, t, J=6 Hz), terminal Me and 1.26 ppm [complex signal from methylenic groups in fatty acid, [(alkyl chain (CH2)n],1.5 ppm [2H, m, C-3 (βCH2-αCH2-CO)] from methylenic group in β-position with respect to carbonylic group, 2.04 ppm (4H, m, -CH2-C=C-CH2-) allylic methylene [of C-8,C-14], 2.3 ppm, (m, from methylene group in α-position with respect to carbonyl group(αCH2CO)of C-2), 2.8 ppm(2H,m,C-11[-C=C-CH 2 -C=C-)] diallylic methylene, 3.66 ppm (3H, s, OMe) and ~5.35 ppm (m, olefinic protons of fatty acid).

Compound 3: Betulonic acid (20 mg, colorless crystals), m.p. (261-264), positive test for sterol and /or triterpenes. Rf values (0.54 S4 and 0.13 S3);color in p-anisaldehyde /H2 SO4 is violet.IR υmax KBr spectrum: Incorporated absorption bands at (3400-3000) of OH group and 1695 cm-1 for acid(C=O), 1707 cm-1 characteristic for cyclic ketone and 1459,890 cm-1 for (C=CH2).EI Mass (70 eV) m/z; 454 (M+) calculated for C30H46O3 with characteristic fragmentation at 438 (M+ -H2 O), 409 (M+ -COOH), 245, 218, 205 and 189 lupane skeleton. 1H-NMR (300 Hz CDCl3): Exhibited signals due to six tertiary methyl groups at 0.82 (3H, s, C26-CH3),0.97(3H, s, C27-CH3),1.03(3H, s, C24-CH3),1.08 (3H, s, C23-CH3), 1.26(3H, s, C25-CH3) and 1.69(3H, s, C30-CH3) and 4.69(1H, s, C29-Hb),4.54(1H, s, C29-Ha), ~2.3(H, m, C2-CH2).

Compound 4 : 3-acetyl methyl betulinate (40 mg, prisms from methanol/CHCl3), m.p. (201-202), positive test for sterol and /or triterpenes. Rf values 0.96 (S4) and 0.86 (S5); color in p-anisaldehyde /H2SO4 is violet. IR υmax KBr spectrum: Incorporated absorption bands at 1736 cm-1 which is characteristic for acetyl ester group and 1638, 877 cm-1 for (C=CH2). EI Mass (70 eV) m/z 512 (M+) calculated for C33H51O4 with characteristic fragmentation at m/z 468 (M+ -acetyl group),by loss of 44, m/z 453 (M+ -COOCH3) loss of 59, m/z 249 (allocate the acetyl group at C-3), 262 (indicative for the presence of carbomethoxyl group at C-28) , m/z 218, m/z 203 and m/z 189 all in accordance with lupene skeleton. 1 H-NMR (300 Hz CDCl3): Exhibited four tertiary methyl groups at 0.80(6H, s, C23-CH3, and C24-CH3), 0.85 (3H, s, C25-CH3), 0.95 (3H, s, C26-CH3), 1.04 (3H, s, C27-CH3) and 1.69 (3H, s, vinylic methyl ,C30-CH3), 2.05 (3H, s, CH3 CO), and 4.45(1H, dd, J=6 Hz, 10.5 Hz ,C3-H-axial) also at 3.67 (3H, s, COOCH3) and 4.69(1H, s, C29 -Hb), 4.58 (1H, s, C29-Ha).

Compound 5: Lupenone (60 mg, white needle crystals from methanol), m.p. (170°C), positive test for triterpenoid skeleton. Rf value 0.43 (S1); color in p-anisaldehyde/H2SO4 is violet. IR υmax KBrspectrum: Showed characteristic absorption bands at 1707 cm-1 indicate cyclic ketoneand 1641, 1455, 878 cm-1 for (C=CH2). EI Mass (70 eV) m/z showed (M+) at 424 indicating a molecular formula C30H48O. High mass daughter peaks showed loss of methyl at m/z 409 (M+-15), 245, 218, 205 (oxo-group in C-3) and 189 all in accordance with lupene skeleton. 1H-NMR (300 Hz CDCl3) exhibited six methyl signals at 0.80(3H, s, C28-CH3), 0.93 (3H, s, C24-CH3), 0.96 (3H, s, C27-CH3), 1.03 (3H, s, C23-CH3), 1.07 (6H, s, C25-CH3, C26-CH3) and 1.69 (3H, s, vinyl methyl, C30-CH3), 2.38 (2H, m, C-2) and 4.70 (1H, d, J=2.5 Hz, C29-Hb), 4.58 (1H, d, J=2.5 Hz, C29-Ha) 2 vinylic proton showing allylic coupling with C-19 proton.

Compound 6: Lupeol (50 mg, crystallize from methanol as white needle crystals, m.p. (210-212), positive test for triterpenoid skeleton. Rf values 0.77 (S4) and 0.32 (S5); violet color with p-anisaldehyde/H2SO4 spray reagent. IR υmax KBR spectrum: Incorporated absorption bands at 3415 cm-1 (OH), 2945, 2869 cm-1 (CH) and 1642, 880 cm-1 for (C=CH2). EI Mass (70eV) m/z(M+) at 426.7 calculated for C30H50O with characteristic fragment ions at 411(M+-Me), 393 (M+-Me-H2O),365,299,297,245, fragment ions at m/z 220, m/z207(allocate the hydroxyl group at C3 position),m/z 218, m/z 205 and m/z 189 all in accordance with lupene skeleton. 1H-NMR (300 Hz CDCl3):Revealed signals for seven tertiary methyl groups at 0.80 (3H, s, C28-CH3),0.85(3H, s, C23-CH3), 0.86 (3H, s, C24-CH3), 0.87 (3H, s, C25-CH3), 0.95 (3H, s, C27-CH3),1.04(3H, s, C26-CH3) and 1.69 (3H, s, vinylic methyl , C30-CH3), 3.15 (1H, dd, J=6 Hz, 10.5 Hz and 4.69(1H, s, C29-Hb), 4.58 (1H, s, C29-Ha).

The isolated compounds 1-6 were identified by comparison of MS, IR, 1 H-NMR, and 13 C-NMR data to previously reported ones and were identified as hendecane 1,[28] methyl linoleate 2,[29,30] betulonic acid 3,[31] 3-acetyl- methyl betulinate 4,[32] lupenone 5,[31] and lupeol 6.[32,33] It is noteworthy to mention that these compounds are isolated for the first time from the leaves of H. caffrum.

Fractionation of the ethyl acetate fraction of the fractionated ethanol extract of the leaves of H. caffrum afforded ten phenolic compounds 7-16 which were identified as : Gallic acid 7 , methyl gallate 8, ethyl gallate 9 , afezlin 10 (kaempferol-3-O-α-rhamnoside), quercitin-3-O rhamnoside 11, quercetin-3-O-β-arabinoside 12, apigenin-7-O-α-glucoside 13, kaempferol-3-O-β-galactoside 14, kaempferol 15, and quercetin 16. Identification was based on comparison of UV, MS, IR, 1H-NMR, and 13C-NMR data to previously reported ones.[16,34–36] However, the compounds were previously isolated and only tentatively identified based on UV data and TLC characters from the leaves of H. caffrum.[9]

Chromatographic fractionation of the ethyl acetate fraction of the ethanol extract of the fruits of R. coriaria L afforded seven phenolic compounds 7, 8, 14, 15, 17-19.

Compound 17: Protocatchuic acid (50 mg, white to brownish white powder, crystallized from water as colorless needles, soluble in acetone and methanol, m.p. (179-182°C). Rf value 0.81(S9), in visible light brown color with NH3. Dark purple in UV and deep blue color with FeCl3 UVλmax nm 260,295 in MeOH, IR√max KBr spectrum: Shows absorption peaks at 3367 cm-1 (OH), 1693 cm-1 (C=O), and 1626 cm-1 for C=C aromatic, 719, 771, 869 cm-1 (-C-H) aromatic. EI Mass (70 eV)m/z;[M+]=m/z 154(M+),137 [M+ -17 (OH)]110[M+ -44 (CO2)],109[M+ -45(COOH)],81[(109-28(CO)],78 ,62, 53. 1 H-NMR (300 Hz CDOD3): Showed signals at δ 6.79 (1H, d, J=8.1 Hz, H-5)7.52(1H, d, J=2.1 Hz, H-2)7.46 (1H, dd, J=8.1, 2.1 Hz, H--6).

Compound 18: Isoquercitrin (50 mg, yellow powder, sparingly soluble in methanol, m.p. (217-219°C). Rf 0.58 (S7),0.3 (S9). 1H-NMR spectrum showed: Aglycone: 8.5(1H,d,J=1.8Hz,H-2‘),7.77(1H, dd, J=1.8, 8.4 Hz, H-6‘)7.22(1H, d, J=8.4 Hz, H-5‘),6.53(d, J=1.5Hz,H-8), 6.45(d, J =1.5 Hz, H-6). *Sugar : 5.5(d, J=6.8 Hz, H-1‘‘)177.43 (C-4),164.39(C-7),161.26(C-5),156.38(C-9),156.18(C-2),148.52(C-4‘),144.85(C-3‘),133.37(C-3),121.63(C-1‘),121.2(C6‘),116.25(C-5‘),115.26(C-2‘),103.83(C-10),100.94(C-1‘‘),98.71(C-6),93.7(C-8),77.16(C-5‘‘),76.04(C-3‘‘),74.14(C-2‘‘),70.28(C-4‘‘),61.05(C-6‘‘)

Compound 19: Myricetrin (60 mg , yellowish brown powder crystallize twice from ethanol as pale yellow plates (m.p. 199-200 °C). 0.64 (S7) and 0.25 in (S9). 1HNMR spectrum showed * Aglycone: 7.14 (2H, s, H-2‘ and H-6‘),6.56(1H, d, J=2.1 Hz,H-8),6.39(1H,d,J=2.1Hz,H-6).* Sugar :5.51(1H, d, J((H-1‘‘/H-2‘‘)=1.5 Hz, H-1‘‘),4.23(1H,dd,J(H-2‘‘/H-1‘‘)= 1.6; J(H-2‘‘/H-3‘‘)=3.4 Hz, H-2‘‘) ,3.77(dd,J(H-3‘‘/H-2‘‘)=3.4;J(H-3‘‘/H-4‘‘)=9Hz,H-3‘‘),3.47-3.30(m)H-4‘‘,5‘‘and 0.95(3H,d,J((CH3 /H-5‘‘)=5.8, CH3-5‘‘). 13CNMR spectrum showed 177.5 (C-4),164.4(C-7),161.2(C-5),156.5(C-9),156.3(C-2),145.6(C-3‘,C-5‘),136.8(C-4‘),133.9(C-3),119.8(C-1‘)108.5(C-2‘and C-6‘),103.9(C-10),102.0(C-1‘‘), 98.8 (C-6),93.6 (C-8),72.16(C-5‘‘), 72.04 (C-3‘‘),71.93(C-2‘‘), 73.28(C-4‘‘) and 17.65 (C-6‘‘).

Identification of the isolated compounds was based on comparison of UV, MS, IR, 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR data to previously reported ones as three phenol acids, gallic acid 7, ethyl gallate 8, protocatechuic acid 17, and four flavonoid compounds: kaempferol 15, quercetin 16, isoquercetrin 18 and myricetin-3-O-α-L-rhamnoside 19 .[16,34–38]

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on isolation of protocatechuic acid 17, quercetin-3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside (isoquercitrin) 18 and myricetin-3-O-α-L-rhamnopyranoside (myricetrin) 19 from the fruits of Sumac. However, these compounds were previously identified in the leaves[12] but isolated for the first time from the fruits of R. coriaria L.

DISCUSSION

The ethanol extract of H. caffrum leaf did not cause any mortality up to 10 g/kg b. wt. when given to male albino rats and thus considered safe. This high margin of safety is encouraging to continue its use as complementary drug.[2,4,5]

The content and composition of H. caffrum leaf evidenced high proportion of polyphenols (flavonoids and non-flavonoids) and triterpenoids (about 25% and 10.5%, respectively). These polyphenols were documented in the literature to possess free radical quenching,[39] hepatotoprotective,[40] anti-inflammatory,[41] and antimicrobial properties.[39]

The presence of phenolic acids, such as gallic acid, methyl gallate, or protocatechuic acid in R. coriaria support the folkloric use of this plant as spice, food preserving as well as wound cleaning[4] and justifies the previously reported pharmacological results.[15]

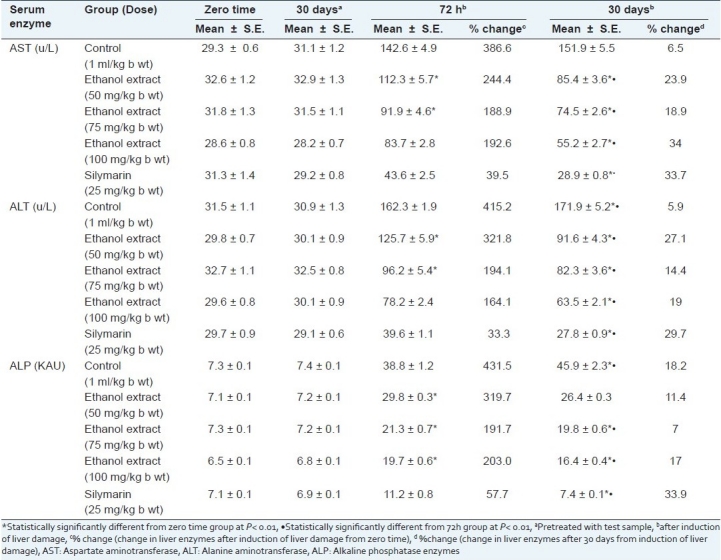

The performed liver function test includes administration of CCl4 to male albino rats to induce functional impairment of the liver. The damage of the liver caused by CCl4 in male albino rats was evident by the alteration in serum transaminases (ALT, AST, and ALP) levels concentration [Table 1]. Compared to the control group, CCl4 caused a significant elevation in serum ALT, AST, and ALP levels. Hepatic protection was evidenced by the ability of H. caffrum leaf extract to normalize the high enzyme parameters in a dose-dependent manner (50, 75, and 100 mg/kg) by 100% for AST, 64% for ALT, and 50% comparable to silymarin.

Table 1.

Effect of the leaf ethanol extract of H. caffrum and silymarin drug in male albino rats (n=10) on serum aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, and alkaline phosphatase enzymes levels

The presence of flavonoids, triterpenes, and phenol acids in H. caffrum in considerable amounts (about 15%, 8.5%, and 10.5%) explain its role in liver protection since flavonoids, triterpenes, and tannins are known to possess hepatoprotective activities.[42–44] Betulonic acid, one of the isolated triterpenes from H. caffrum, is potentially active as antioxidant and antitumor.[45] Certain flavonoids are known as antioxidant agents and may interfere with free radical formation. The results obtained in this study suggest that the ethanol leaf extract of H. caffrum can normalize elevated liver enzymes.

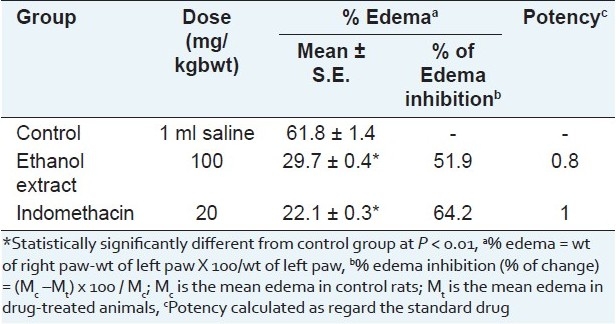

The same extract evidenced anti-inflammatory activity on carrageenan induced hind paw edema in rats. The activity is approximated to be 80% of that of indomethacin at the experimental dose level [Table 2]. This activity could be attributed to the presence of high polyphenol content,[46,47] in addition to its content of triterpenes as lupeol, which has been specifically well recognized for its anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer activities.[45] The demonstrated experimental study [Tables 2–4] supports the use of H. caffrum in folk medicine for the treatment of inflammations and pain.[48]

Table 2.

Effect of the leaf ethanol extract of H. caffrum and indomethacin on carrageenaninduced hind paw edema in male albino rats (n=10)

Table 4.

Effect of leaf ethanol extract of H. caffrum and paracetamol drug in male albino rats on yeastinduced hyperthermia in male albino rats (n=10)

Table 3.

Analgesic activity of leaf ethanol extract of H. caffrum and Novalgin in male albino rats (n=10)

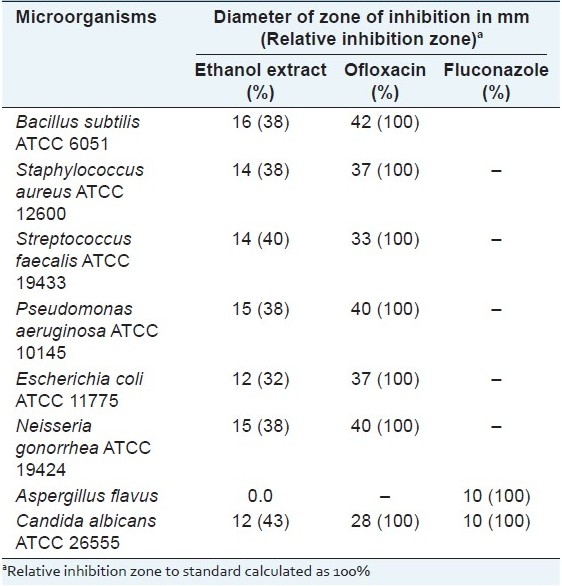

When screened for antimicrobial activity [Table 5] against selected bacterial and fungal strains of standard properties noticeable effect was demonstrated by the leaf extract of H. caffrum which could be attributed to the presence of phenolic acids such as gallic acid and methyl gallate.[39]

Table 5.

Results of the antimicrobial testing of the leaf ethanol extract of H. caffrum

On assessing the cytotoxic activity [Table 6], the leaf ethanol extract of H. caffrum showed in vitro cytotoxic activity against the tested human carcinoma cell lines especially on human liver carcinoma cell line (IC50 1.28 μg/ml) compared to the standard Doxorubicin. Lupeol is reported to exhibit moderate anti-cancer activity and could thus be responsible of the demonstrated in vitro cytotoxic activity along with the other lupane triterpenes.[44]

Table 6.

Results of cytotoxic activity of the leaf ethanol extract of H. caffrum

The biological activity evidenced in this study, namely hepatoprotective, anti-inflammatory, analgesic, antimicrobial, and in vitro cytotoxic activities of H. caffrum are reported for the first time. However, further investigation is needed to ascertain the precise mechanism(s) of these activities.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bailey LH. New York: The Macmillan Company; 1953. The Standard Cyclopedia of HorticultureIII; pp. 2952–4. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abbasi AM, Khan MA, Ahmad M, Zafar M, Jahan S, Sultana S. Ethnopharmacological application of medicinal plants to cure skin diseases and in folk cosmetics among the tribal communities of North-West Frontier Province, Pakistan. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;128:322–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chopra IC, Handa KL, Kapur LD. 2nd ed. Calcutta: U.N. Dhur and Sons Private Limited; 1958. Chopra's Indigenous Drugs of India; p. 337. (407,498,525). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sezik E, Tabata M, Yesilada E, Honda G, Goto K, Ikeshiro Y. Traditional medicine in Turkey I. Folk medicine in Northeast Anatolia. J Ethnopharmacol. 1991;35:191–6. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(91)90072-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Wyk BE, van Oudtshoom B, Gericke N. 2nd ed. Pretoria: Briza Publication; 2002. Medicinal Plants of South Africa; p. 146. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buwa LV, van Staden J. Antibacterial and antifungal activity of traditional medicinal plants used against venereal diseases in South Africa. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;103:139–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pourahmad J, Eskandari MR, Shakibaei R, Kamalinejad M. A search for hepatoprotective activity of aqueous extract of Rhus coriaria L. against oxidative stress cytotoxicity. Food Chem Toxicol. 2010;48:854–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2009.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gunduz GT, Gonul SA, Karapinar M. Efficacy of sumac and oregano in the inactivation of Salmonella typhimurium on tomatoes. Int J Food Microbiol. 2010;141:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El Sherbeiny AE, El Ansari MA. The polyphenolics and flavonoids of Harpephyllum caffrum. Planta Med. 1976;29:129–32. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1097641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moyo M, Ndhlala AR, Finnie JF, Van Staden J. Phenolic composition, antioxidant and acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activities of Sclerocaryabirrea and Harpephyllum caffrum (Anacardiaceae) extracts. S Afr Food Chem. 2010;123:69–76. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mavlyanov SM, IslambekovSh Yu, Karimdzhanov AK, Ismailov AI. Anthocyansand organicacids of the fruits of some species of Sumac. Chem Nat Com. 1997;33:209. [Google Scholar]

- 12.el-Sissi HI, Ishak MS, el-Wahid MS. Polyphenolic components of Rhus coriaria leaves. Planta Med. 1972;21:67–71. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1099524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lehman EM. USA: The University of Michigan; 2008. Dynamics of Liver Disease in Egypt: Shifting Paradigms of a Complex Etiology.Ph D (Epidemiological Science) pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strickland GT, Elhefni H, Salman T, Waked I, Abdel-Hamid M, Mikhail NN, et al. Role of hepatitis C infection in chronic liver disease in Egypt. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;67:436–42. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.67.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shabana MM, El Sayed AlyM, Yousif MF, El Sayed Abeer M, Sleem AA. Phytochemical and biological study of Sumac. Egypt J Pharm Sci. 2008;49:83–101. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mabry JT, Markham KR, Thomas MB. 2nd ed. New York-Berlin-Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 1996. The Systematic Identification of Flavonoids. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klassan CD, Plaa GL. Comparison of the biochemical alteration elicited in liver of rats treated with CCl4 and CHCl3. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1969;18:2019. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paget GE, Barnes JM. New York: Academic Press Inc; 1964. Evaluation of Drug Activities Sited in Laboratory Rats. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karber G. Beitragzurkollektiven Behandlungpharmokologischer Reihenversuche. Arch Exp Pathol Pharmacol. 1931;162:480–3. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thewfweld W. Enzymatic method for determination of serum AST and ALT. Deutsch Med wochen. 1974;99:334–47. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kind PR, King EJ. Estimation of plasma phosphatase by determination of hydrolysed phenol with amino-antipyrine. J Clin Path. 1954;7:322. doi: 10.1136/jcp.7.4.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winter CA, Risley EA, Nuss GW. Carrageenin induced edema in hind paw of the rat as an assay for antiinflammatory drugs. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1962;111:544–7. doi: 10.3181/00379727-111-27849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Charlier R, Prost H, Binon F, Dellous G. Pharmacology of an antitussive, 1 phenethyl-4 (2-propenyl)-4-propinoxypipridine acid fumarate. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1961;134:306–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bush IE, Alexander RW. An improved method for the assay of anti-inflammatory substances in rats. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 1960;35:268–76. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.xxxv0268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Snedecor GW, Cochran WG. 8th ed. Iowa: Iowa State University Press; 1989. Statistical methods. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skehan P, Storeng R, Scudiero D, Monks A, McMahon J, Vistica D. New colorimetric cytotoxicity assay for anticancer-drug screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1990;82:1107–12. doi: 10.1093/jnci/82.13.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lorian V. 3rd ed. Hong Kong- London: Williams and Williams; 1991. Antibiotics in Laboratory Medicine; pp. 134–44. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silverstein RM, Webster FX, Kiemie D. 6th ed. USA: John Wiley Sons Inc; 1998. Spectrometric Identification of Organic Compounds. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Diaz MF, Gavin JA. Characterization by NMR of ozonoid methyl linoleate. J Braz Chem Soc. 2007;18:513–8. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jie MS, Mustafa J. High-resolution nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy-applications to fatty acids and triacylglycerols. Lipids. 1997;32:1019–34. doi: 10.1007/s11745-997-0132-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carpenter RC, Sotheeswaran S, Sultanbawa M, Uvais S, Ternai B. 13C-NMR Studies of some lupane and taraxeranetriterpenes. Org Magn Reson. 1980;14:462–5. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kircher HW. Triterpenes in organ Pipe Cactus. Phytochemistry. 1980;19:2707–12. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dantanrayana AP, Savitri NK, Muthukuda PM, Wazeer MI. A lupane derivative and the 13C-NMR chemical shifts of some lupanols from Pleurostyliaopposita. Phytochemistry. 1982;21:2065–8. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Agrawal PK. New York: Elsevier Publishing Company; 1989. 13C-NMR of Flavonoids; p. 292. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shen CC, Chang YS, HoL K. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Studies of 5, 7-dihydroxyflavonoids. Phytochemistry. 1993;4:843–5. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hussein SA, Hashem AN, Seliem MA, Lindequist U, Nawwar MA. Polyoxygenated flavonoids from Eugenia edulis. Phytochemistry. 2003;64:883–9. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(03)00437-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gutzeit D, Wray V, Winterhalter P, Jerz G. Preparative isolation and purification of flavonoids and protocatechuic acid from sea Buckthorn juice concentrate (Hippophaerhamnoides L. ssp rhamnoides) by high speed counter current chromatography. Chromatographia. 2007;65:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marzouk M. Acylatedflavonol glycosides and hydrolysable tannins from Euphorbia cotinifolia L. leaves. Bull Fac Pharm Cairo Univ. 2008;46:181–91. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Proestos C, Boziaris IS, Kapsokefalou M, Komaitis M. Natural antioxidant constituents from selected aromatic plants and their antimicrobial activity against selected pathogenic microorganisms. Food Technol Biotechnol. 2008;46:151–6. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang J, Li Y, Wang F, Wu JC. Hepatoprotective effects of Apple polyphenols on CCl4 -induced acute liver damage in mice. Agric Food Chem. 2010;58:6525–31. doi: 10.1021/jf903070a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Owoyele V, Oguntoye SO, Dare1 K, Ogunbiyi BA, Aruboula EA, Soladoye AO. Analgesic, anti-inflammatory and antipyretic activities from flavonoid fractions of Chromolaenaodorata Bamidele. J Med Plants Res. 2008;2:219–25. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Babu BH, Shylesh BS, Padikkala J. Antioxidant and hepatoprotective effect of Acanthus ilicifolius. Fitoterapia. 2001;72:272–7. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(00)00300-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sureshkumar SV, Mishra SH. Hepatoprotective activity of extracts from Pergulariadaemia Forsk. against carbon tetrachloride-induced toxicity in rats. Phcog Mag. 2007;3:187–91. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Soliman FM, Shehata AH, Khaleel AE, Ezzat SM, Sleem AA. Caffeoyl derivatives and flavonoids from three Compositae species. Phcog Mag. 2008;4:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saleem M. Lupeol. Anovel anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer dietary triterpene. Cancer Lett. 2009;285:109–15. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dutta S, Das S. A study of the anti-inflammatory effect of the leaves of Psidiumguajava Linn. on experimental animal models. Phcog Res. 2010;2:313–7. doi: 10.4103/0974-8490.72331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gambhire MN, Wankhede SS, Juvekar AR. Anti inflammatory activity of aqueous extract of Barleri acristata leaves. J Young Pharm. 2009;1:220–4. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jager AK, Hutchings A, van Staden J. Screening of Zulu medicinal plants for prostaglandin-synthesisinhibitors. J Ethnopharmacol. 1996;52:95–100. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(96)01395-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]