Abstract

Purpose

Most researchers who are conducting physical activity trials face difficulties in recruiting participants who are representative of the population or from specific population groups. Participants who are often the hardest to recruit are often those who stand to benefit most (the least active, from ethnic and other minority groups, from neighbourhoods with high levels of deprivation, or have poor health). The aim of our study was to conduct a systematic review of published literature of walking interventions, in order to identify the impact, characteristics, and differential effects of recruitment strategies among particular population groups.

Methods

We conducted standard searches for studies from four sources, (i) electronic literature databases and websites, (ii) grey literature from internet sources, (iii) contact with experts to identify additional "grey" and other literature, and (iv) snowballing from reference lists of retrieved articles. Included studies were randomised controlled trials, controlled before-and-after experimental or observational qualitative studies, examining the effects of an intervention to encourage people to walk independently or in a group setting, and detailing methods of recruitment.

Results

Forty seven studies met the inclusion criteria. The overall quality of the descriptions of recruitment in the studies was poor with little detail reported on who undertook recruitment, or how long was spent planning/preparing and implementing the recruitment phase. Recruitment was conducted at locations that either matched where the intervention was delivered, or where the potential participants were asked to attend for the screening and signing up process. We identified a lack of conceptual clarity about the recruitment process and no standard metric to evaluate the effectiveness of recruitment.

Conclusion

Recruitment concepts, methods, and reporting in walking intervention trials are poorly developed, adding to other limitations in the literature, such as limited generalisability. The lack of understanding of optimal and equitable recruitment strategies evident from this review limits the impact of interventions to promote walking to particular social groups. To improve the delivery of walking interventions to groups which can benefit most, specific attention to developing and evaluating targeted recruitment approaches is recommended.

Keywords: Recruitment, walking, physical activity, health promotion

Introduction

It is over a decade since Professors Jerry Morris and Adrienne Hardman described walking as the 'nearest activity to perfect exercise' (Hardman & Morris, p328, 1997) [1]. The epidemiological research underpinning their statement has rapidly increased, so that the promotion of walking is now a central pillar in many international physical activity strategies and national plans, e.g. 2010 Toronto Charter for Physical Activity [2]. Regular walking, independent of other physical activity, can reduce the risk of overall mortality, of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and improve risk factors for CVD, including diastolic blood pressure and lipid profiles [3-5]. Regular walking is associated with a reduction in body mass index and body weight, with reduced risk of type 2 diabetes [6] and is suggested to improve self esteem, relieve symptoms of depression and anxiety, and improve mood [7,8]. From a public health perspective, enabling an increase in overall population levels of physical activity through walking will produce an effective reduction in risk of all cause mortality [9].

A systematic review of the effectiveness of walking interventions found evidence for a range of approaches [10]. These included brief advice to individuals, remote support to individuals, group-based approaches, active travel and community level approaches. Recent reviews have provided evidence to support environmental and school based travel interventions [10-12]. Despite the evidence for the benefits of walking for health, population rates of walking and overall physical activity remain low and below recommended levels [13-15]. Population surveys report that walking behaviour is socially patterned by gender, age, socio-economic status (SES) and by the purpose of walking i.e. for leisure or transport. For example, in the UK long brisk paced walks are more common among affluent groups, whereas walking for transport is more common among less affluent groups [14,16].

One criticism of the evidence base for walking interventions is a failure to recruit specific groups of the population and further studies are needed to broaden the reach of walking interventions [10-12]. Intervention reach, or recruiting specific population sub-groups, is only partially reflected in public health and clinical research. For example the RE-AIM framework is designed to guide the implementation of behaviour change interventions [17]. It recommends assessing both an intervention's effectiveness and ability to reach a targeted group. Similarly, recent CONSORT (2010) guidelines [18] recommend clearly displaying the flow of participants throughout a study. Despite identifying recruitment as part of their framework, the guidelines do not define the actions needed to identify and recruit potential populations of participants. There is an absence of conceptual frameworks for recruitment to intervention studies and also a lack of procedural models and systems for recruitment. There is a need to identify what factors are effective in engaging participation at the recruitment phase [19-21].

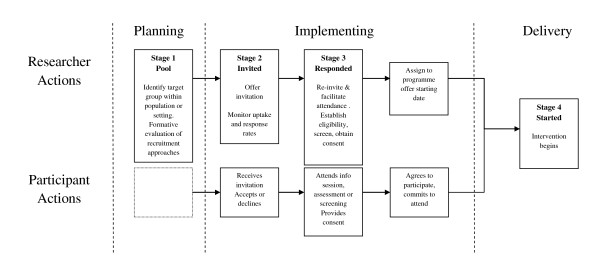

Research examining recruitment practice has focused on drug or medical interventions rather than public health interventions [22]. Little is known about recruitment to physical activity interventions. A Cochrane review identified three stages of recruitment (invitation, screening, intervention starting) for potential participants into physical activity randomised control trials (RCTs). The authors noted a considerable loss of participants across each stage limiting the effectiveness of interventions [23]. The CONSORT (2010) guidelines, suggest that studies report the number of eligible participants prior to randomisation but do not insist on the need to report the original overall number of responders invited to participate (prior to eligibility) [18].

Clearly the effectiveness of a walking programme is limited by not only its efficacy of dose (how well the intervention works on its participants) but also by its recruitment (maximising the numbers who will participate and receive the intervention dose). In response to frequent research calls to evaluate effective approaches to the recruitment of individuals to walking studies, the Scottish Physical Activity Research Collaboration http://www.sparcoll.org.uk undertook a series of studies to examine recruitment strategies for research and community based programmes of walking promotion. We defined recruitment for such walking studies or programmes as the process of inviting participation to a formal activity including the invitation, informing and facilitation of interested parties to take part in an organised study, activity or event. This paper reports the results of a systematic review to examine the reported recruitment procedures of walking studies, in order to identify the characteristics of effective recruitment, and the impact and differential effects of recruitment strategies among particular population groups.

Method

Identification of studies

We used The Quality of Reporting of Meta-analysis statement (QUOROM) to provide the structure for our review [24]. We identified four possible sources of potential studies, (i) electronic literature databases and websites, (ii) grey literature from internet sources, (iii) contact with experts to identify additional "grey" and other literature, and (iv) snowballing from reference lists of retrieved articles. In the first stage of the literature search, titles and abstracts of identified articles were checked for relevance. In the second stage, full-text articles were retrieved and considered for inclusion. In the final stage, the reference lists of retrieved full-text articles were searched and additional articles known to the authors were assessed for possible inclusion. We conducted a systematic search of electronic databases including OVID MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsychINFO, PubMed, Scopus, SIGLE and SPORTDiscus. We searched a number of web based databases including National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), Effective Public Health Project (EPHP Hamilton), Health Evidence Canada, and the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (EPPI)). We conducted searches of internet sites of key international walking promotion agencies including Walk England, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organisation (WHO).

Studies published from the end of 2000 up to and including the search date (05/2009) were considered for inclusion. Individualized search strategies for the different databases included combinations of the following key words: (walk*) AND (recruit* OR participat* OR market*). Articles published or accepted for publication in refereed journals were considered for the review. Articles reported in UK grey and web based literature including any evidence of types of recruitment approaches and strategies, any evidence of effectiveness, economic costs, and evidence of any differential response to recruitment approaches were also considered in the review. Conference proceedings and abstracts were included if further searching of the databases or contact with the author was able to retrieve a full article from the study presented in the original piece of literature. We sent emails to international experts, identified in a previous systematic review on walking promotion [10].

Criteria for study inclusion/exclusion

Titles, abstracts and reports were independently assessed (by AM, CF and GB) for inclusion. Studies were considered to be eligible for inclusion according to the following criteria: (i) participants were of any age and were not trained athletes or sports students, (ii) studies of any type including randomised controlled trials, controlled before-and-after experimental or observational studies, (iii) studies that examined the effects of an intervention to encourage people to walk independently or in a group setting, (iv) interventions of any kind and in any field, whether targeted on individuals, communities, settings, groups or whole populations, (v) details of methods of recruitment were reported or were retrievable through correspondence with the authors, (vi) qualitative studies that examined the experiences of the participants during recruitment and which aimed to assess the effectiveness of the recruitment methods used, and (vii) studies published in English.

Included studies were categorised by study design using standardised criteria for quantitative experimental or observational studies (e.g. RCT, non-Randomised Control Trials (NRCT), before-and-after, cross-sectional), or qualitative studies (e.g. focus groups) [25].

Criteria for assessment of study quality in relation to recruitment

Two authors (GB and CF) independently assessed the quality of the studies in relation to recruitment description that met the inclusion criteria. The criteria for assessing the recruitment reporting quality of each study were adapted from Jadad (1998) [26], and in consultation with experts. A formal quality score for each study was completed on a 5-point scale by assigning a value of 0 (absent or inadequately described) or 1 (explicitly described and present) to each of the following questions listed: (i) did the study report where the population was recruited? (ii) did the study report who conducted the recruitment? (iii) did the study report the time spent planning/preparing the recruitment? (iv) did the study report the time spent conducting the recruitment? (v) did the study target a specific population? Studies that scored 4-5 were considered as high quality studies while studies that scored 1-3 were considered low quality.

Criteria for assessing efficiency and effectiveness

Where possible we calculated recruitment rates and efficiency ratios for each study, based on a previous systematic review of interventions to promote physical activity [23]. We defined four terms, (i) "pool"-the total number of potential participants who could be eligible for study, (ii) "invited"-the total number of potential participants invited to participate in the study, (iii) "responded"-the total number of potential participants who responded to the invitation, (iv) "started"-the number of participants who were assessed as eligible to participate and began the programme. If data were reported we calculated ratios for each stage, e.g. started/pool-by dividing the number of participants who started into the study by the total reported in the pool, and expressed as proportions. If possible we attempted to calculate a weekly rate of recruitment for those studies on the number of weeks/months spent recruiting per participant.

Results

Study Characteristics

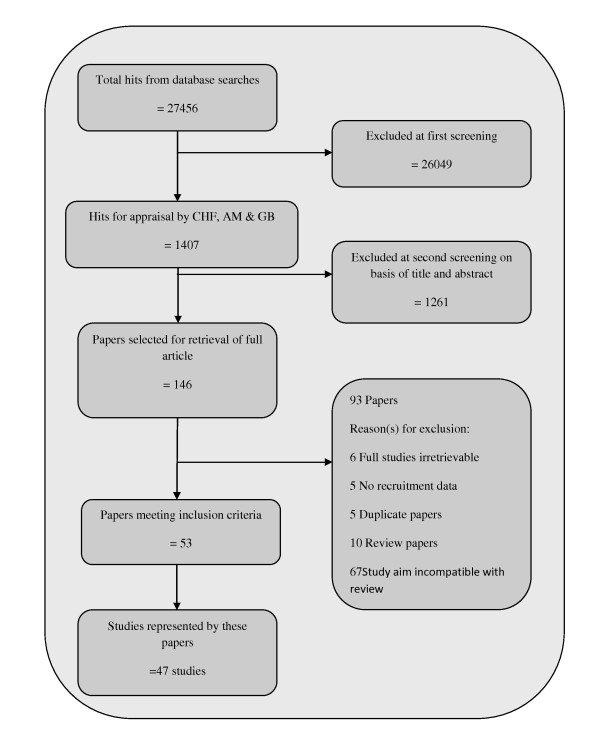

Fifty three papers representing 47 studies met our inclusion criteria. Duplicate studies were excluded and the journal article reporting the most recruitment data was analysed. The flow of studies through the review process is reported in Figure 1. Characteristics of included studies are presented in Table 1, ranked by quality score. Each included paper is referenced in the results and discussion sections in superscript, using their Study Number presented in Table 1. Full references for included papers are listed in additional file 1 and are presented in this paper in superscript form. Studies were located in the USA (24) [27-50], Australia (11) [51-61], UK (7) [62-68], Canada (3) [69-71], and one each from New Zealand [72] and Belgium [73]. Nearly all the studies were quantitative experimental studies in design, with twenty six randomised controlled trials, [4,27,28,32-34,36-38,42,43,46,47,49,52,54,56,58,62-67,70] two studies reporting methods only [28,35], three non-randomised controlled trials [31,41,73] and seventeen before-and-after studies [27,29,30,39,40,44,45,48,50,51,53,55,59-61,68,71] (two reporting methods only) [27,30]. We found only two qualitative studies reporting on recruitment approaches [57,69], with one paper reporting qualitative data as part of an RCT study [64]. No studies were located from grey literature sources.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study selection.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Study Number, Author and Pub. Year | Country | Study Type | Study aim | Target Population | Quality Metric Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Watson et al, 2005 | Australia | Before-and-after study | Evaluate the effect of pram walking groups on self-reported PA, mental health and social indicators. | Post-natal mothers | 5 |

| 2. Banks-Wallace et al, 2004 | USA | Before-and-after study Methods paper |

Examine the effect of pre-intervention meetings as a strategy for recruitment of African American women to a walking programme. | African American women in a local community (Minority group) | 4 |

| 3. Kolt et al, 2006 | New Zealand | RCT | To investigate the effectiveness of a telephone-based counselling intervention aimed to increase physical activity in sedentary older adults. | Older sedentary adults (> 65) | 4 |

| 4. Nguyen et al, 2002 | Canada | Qualitative | To evaluate the experience of delivering a walking club (qualitative method) | General community | 4 |

| 5. Prestwich et al, 2010 | UK | RCT | To test the effect of implementation intentions and text messages on the promotion of brisk walking. | University students | 4 |

| 6. Rowland et al, 2004 | USA | RCT Methods paper |

To report on the recruitment of sedentary adults to the SHAPE programme | Sedentary older adults | 4 |

| 7. Sherman et al, 2006 | USA | Before-and-after study | Effect of a brief primary care based walking intervention in rural women | Rural women | 4 |

| 8. Wilbur et al, 2006 | USA | Before-and-after study Methods paper |

To identify strategies successful in the recruitment of African American women to a home-based walking programme and to examine the factors that contribute to attrition, eligibility, and ineligibility during the recruitment screening protocol. | African American Women | 4 |

| 9. Baker et al, 2008b | UK | RCT | Effectiveness of pedometer based community walking intervention on PA and health | Community members in areas of high deprivation (> 15% SIMD) | 3 |

| 10. Brownson et al 2005 | USA | NRCT | To evaluate the impact of community based walking approaches | Rural community members | 3 |

| 11. Cox et al, 2008 | Australia | RCT | Examine the effects of exercise mode and a behavioural intervention on short and long-term retention and adherence. | Previously sedentary older women | 3 |

| 12. Dinger et al, 2007 | USA | RCT | Compare the effectiveness of two email delivered, pedometer based interventions designed to increase walking and TTM constructs among insufficiently active women. | Insufficiently active women (University staff and local community members) | 3 |

| 13. Dubbert et al, 2002 | USA | RCT | Effect of nurse counselling on walking for exercise in elderly patients (10 months study) | Elderly primary care patients | 3 |

| 14. Dubbert et al, 2008 | USA | RCT | To evaluate the effects of counselling linked with PHC visits on walking and strength exercise in aging veterans | Elderly veterans | 3 |

| 15. Gilson et al, 2008 | UK | RCT, Qualitative | To compare two walking interventions and measure their effect on daily step counts in a work-place environment | Work-place employees | 3 |

| 16. Jancey et al, 2008 | Australia | Before-and-after study | To mobilise older adults into a neighbourhood-based walking programme | Older adults | 3 |

| 17. Lamb et al, 2002 | UK | RCT | To compare lead walks vs. advice only on PA (walking) | Middle aged adults | 3 |

| 18. Lee et al, 1997 | USA | RCT Methods paper |

To compare the efficacy of a mail versus phone based behavioural intervention to promote walking for US adults | Sedentary ethnic minority women | 3 |

| 19. Matthews et al, 2007 | USA | RCT | To evaluate the effects of a 12-week home-based walking intervention among breast cancer survivors | Breast cancer survivors | 3 |

| 20. Merom et al, 2007 | Australia | RCT | Efficacy of pedometers to act as a motivational tool in place of face to face contact as part of a self-help package to increase PA through walking. | Inactive adults | 3 |

| 21. Ornes and Ransdell, 2007 | USA | RCT | To evaluate the impact of a web-based intervention for women | Women | 3 |

| 22. Richardson et al, 2007 | USA | RCT | To compare the effects of structured and lifestyle goals in an internet-mediated walking programme for adults with type 2 diabetes | Adults with type 2 diabetes | 3 |

| 23. Rosenberg et al, 2009 | USA | Before-and-after study | Feasibility and acceptability of a novel multilevel walking intervention for older adults in a continuing care retirement community (CCRC). | Older adults | 3 |

| 24. Whitt-Glover et al, 2008 | USA | Before-and-after study | Feasibility and acceptability of implementing a physical activity program for sedentary black adults in churches. (Information sessions and lead walks) | Black adult, church attendees | 3 |

| 25. Arbour & Ginis, 2009 | Canada | RCT | Evaluate the effectiveness of implementation intentions on walking behaviour | Women in the workplace | 2 |

| 26. Culos-Reed et al, 2008 | Canada | Before-and-after study | To assess the feasibility and health benefits of a mall walking programme. | NS | 2 |

| 27. Currie and Develin, 2001 | Australia | Before-and-after study | To evaluate the impact of a community based pram walking programme-organised pram walks. | Mothers and young children | 2 |

| 28. Darker et al, 2010 | UK | RCT | To examine whether altering perceived behavioural control (PBC) affects walking (6/7 weeks). | NS | 2 |

| 29. De Cocker et al 2007 | Belgium | NRCT | Describe the effectiveness of the '10,000 steps Ghent' project. | 'General population' adults in a local community | 2 |

| 30. Dinger et al, 2005 | USA | NRCT | Examine the impact of a 6 week minimal contact intervention on walking behaviour, TTM and self efficacy among women. | Female employees or spouses of university employees | 2 |

| 31. Engel and Lindner, 2006 | Australia | RCT | To evaluate the effect of a pedometer intervention on adults with type 2 diabetes | Adults with type 2 diabetes | 2 |

| 32. Foreman et al, 2001 | Australia | Qualitative | To increase the community's participation in physical activity through group walking | Community members | 2 |

| 33. Humpel et al, 2004 | Australia | RCT | Examine the effectiveness of self-help print materials and phone counselling in a study aimed specifically at promoting walking for specific purposes | Over 40 year old community members | 2 |

| 34. Nies et al, 2006 | USA | RCT | To increase walking activity in sedentary women (Video education, brief telephone calls without counselling, brief telephone calls with counselling) | European American and African America women. | 2 |

| 35. Purath et al, 2004 | USA | RCT | To determine if a brief, tailored counselling intervention is effective for increasing physical activity in sedentary women, in the workplace | Women in the workplace | 2 |

| 36. Shaw et al, 2007 | Australia | Before-and-after study | To evaluate a workplace pedometer intervention | Men and women in the workplace | 2 |

| 37. Sidman et al, 2004 | USA | Before-and-after study | Promote physical activity through walking | Sedentary women | 2 |

| 38. Thomas and Williams, 2006 | Australia | Before-and-after study | Increase activity through wearing a pedometer and encouraging participants to aim for 10,000 steps per day. | Workplace staff (Excluding hospital and community services staff) | 2 |

| 39. Tudor-Locke et al, 2002 | USA | Before-and-after study | Feasibility study of a community walking intervention | Sedentary diabetes sufferers | 2 |

| 40. Baker et al, 2008a | UK | RCT | Examine the effectiveness of pedometers to motivate walking. | NS | 1 |

| 41. Hultquist et al, 2005 | USA | RCT | To compare the impact of two walking promotion messages | NS | 1 |

| 42. Lomabrd et al, 1995 | USA | RCT | To evaluate the effects of low v high prompting for walking | NS | 1 |

| 43. DNSWH, 2002 | Australia | Before-and-after study | To evaluate the impact of park modification, promotion of park use and establishment of walking groups on physical activity (including walking) | NS | 1 |

| 44. Rovniak, 2005 | USA | Before-and-after study | Examine the extent to which theoretical fidelity influenced the effectiveness of two walking programmes based on SCT. | NS | 1 |

| 45. Rowley et al, 2007 | UK | Before-and-after study | To examine the development of two walking programmes by a health visiting team to encourage undertaking of more exercise. | Parents and children | 1 |

| 46. Talbot et al, 2003 | USA | RCT | To evaluate the effects of a home based walking programme with arthritis self-management education | Older adults | 1 |

| 47. Wyatt et al, 2004 | USA | Before-and-after study | Increasing lifestyle physical activity (i.e. walking) for weight gain prevention | State wide residents of the community | 1 |

Overview of study quality in relation to recruitment

Eight studies were classified as "high" quality [27-30,51,62,69,72] and the remaining thirty nine classified as "low" quality in relation to recruitment description (Table 2-Assessment of study quality). Forty five studies reported a setting where the recruitment of participants took place [27-49,51-67,69-73] but only twenty two reported who conducted the recruitment [27-31,33,35-40,45,51-54,62,64,65,69,72]. Eleven studies reported the time spent conducting their recruitment [27-30,32,51,62,63,66,70,72] three studies reported the time spent planning/preparing recruitment [34,51,69]. Forty studies reported a target population [27-45,48,50-60,62-65,68-70,72,73].

Table 2.

Assessment of study quality

| Study Author (Year) | Did the study report where the population was recruited? | Did the study report who conducted the recruitment? | Did the study report the time spent planning/preparing the recruitment? | Did the study report the time spent conducting the recruitment? | Did the study target a specific population? | Quality Metric score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| l. Watson et al, 2005 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 5 |

| 2. Banks-Wallace et al, 2004 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 4 |

| 3. Kolt et al, 2006 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 4 |

| 4. Nguyen et al, 2002 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 4 |

| 5. Prestwich et al, 2010 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 4 |

| 6. Rowland et al, 2004 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 4 |

| 7. Sherman et al, 2006 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 4 |

| 8. Wilbur et al, 2006 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 4 |

| 9. Baker et al, 2008b | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | 3 |

| 10. Brownson et al 2005 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | 3 |

| 11. Cox et al, 2008 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | 3 |

| 12. Dinger et al, 2007 | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | 3 |

| 13. Dubbert et al, 2002 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | 3 |

| 14. Dubbert et al, 2008 | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | 3 |

| 15. Gilson et al, 2008 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | 3 |

| 16. Jancey et al, 2008 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | 3 |

| 17. Lamb et al, 2002 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | 3 |

| 18. Lee et al, 1997 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | 3 |

| 19. Matthews et al, 2007 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | 3 |

| 20. Merom et al, 2007 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | 3 |

| 21. Ornes and Ransdell, 2007 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | 3 |

| 22. Richardson et al, 2007 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | 3 |

| 23. Rosenberg et al, 2009 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | 3 |

| 24. Whitt-Glover et al, 2008 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | 3 |

| 25. Arbour & Ginis, 2009 | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | 2 |

| 26. Culos-Reed et al, 2008 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | 2 |

| 27. Currie and Develin, 2001 | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | 2 |

| 28. Darker et al, 2010 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | 2 |

| 29. De Cocker et al 2007 | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | 2 |

| 30. Dinger et al, 2005 | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | 2 |

| 31. Engel and Lindner, 2006 | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | 2 |

| 32. Humpel et al, 2004 | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | 2 |

| 33. Nies et al, 2006 | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | 2 |

| 34. Purath et al, 2004 | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | 2 |

| 35. Shaw et al, 2007 | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | 2 |

| 36. Sidman et al, 2004 | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | 2 |

| 37. Thomas and Williams, 2006 | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | 2 |

| 38. Tudor-Locke et al, 2002 | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | 2 |

| 39. Foreman et al, 2001 | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | 2 |

| 40. Baker et al, 2008a | Yes | No | No | No | No | 1 |

| 41. Hultquist et al, 2005 | Yes | No | No | No | No | 1 |

| 42. Lomabrd et al, 1995 | Yes | No | No | No | No | 1 |

| 43. DNSWH, 2002 | Yes | No | No | No | No | 1 |

| 44. Rovniak, 2005 | Yes | No | No | No | No | 1 |

| 45. Rowley et al, 2007 | No | No | No | No | Yes | 1 |

| 46. Talbot et al, 2003 | Yes | No | No | No | No | 1 |

| 47. Wyatt et al, 2004 | No | No | No | No | Yes | 1 |

| Totals | 45 Yes 2 No | 22 Yes 25 No | 3 Yes 44 No | 11 Yes 36 No | 40 Yes 7 No |

Characteristics of the participants

Thirty seven studies reported participant ages [28-30,32-47,49,51-54,56,58,59,62-67,70-73] with a mean age of 50.6 years, (SD ± 8.1 years), and a range of 18 to 92 years (Table 3-Characteristics of participants). Sixteen out of forty two studies that reported gender data focused on recruiting female only participants [27,29,30,32,35-37,41-44,46,51,52,55,68,70], with one study recruiting men only [34]. From the remaining twenty five studies that did not recruit sex specific groups, 70% (SD ± 20.8) of participants were female. Twenty two studies reported data on nationality and ethnicity, of which seventeen reported descriptive statistics for ethnicity or race [27-38,40-42,46,49,51,54,58,68,70,71]. Three studies reported targeting one specific ethnic group, African-Americans [27,30,40]. Of the remaining studies, twelve reported other ethnicity data; 87% of these participants were white Caucasian [28,31-34,36,38,41,43,49,70,71]. Additional socio-demographic data (SES or income groups, education, urban/rural living and relationship status) were reported but not consistently across all studies. Seven studies reported data on participant's income level data, which tended to be higher than average [28,30,31,38,42,49,68]. Sample sizes of the studies ranged from 9 to 1674 participants.

Table 3.

Characteristics of participants

| Study Number, Author and Pub. Year | Mean age, SD or Range | Gender (%Female) | Ethnicity | SES/Income | Education | Quality Metric Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| l. Watson et al, 2005 | 29.4 | 100 | NS (20% Not Australian born) | 96% married, 80% Australian born. Competent at filling in a questionnaire in English | 39.2% third level education | 5 |

| 2. Banks-Wallace et al, 2004 | 18+ | 100 | African American | NS | NS | 4 |

| 3. Kolt et al, 2006 | 74 (SD 6) | 66 | NS | Urban, Patients from three GP lists. Phone lines at home. | NS | 4 |

| 4. Nguyen et al, 2002 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | 4 |

| 5. Prestwich et al, 2010 | 23.44 | 64 | NS | Students | Undergraduate | 4 |

| 6. Rowland et al, 2004 | 74 (SD 6.2) | 69 | White (Non-Hispanic) 89% | Income > 35 K US 26%, Married, 57.5%. | Edu. > High school diploma 45% | 4 |

| 7. Sherman et al, 2006 | 42.5 (Range 22-64) | 100 | Caucasian | Rural, 42% Medicare, 43% private insurance, 15% self pay or unknown insurance details, mean BMI 30.6 (78% overweight or obese), 90% with one or more risk factors for CV disease, | NS | 4 |

| 8. Wilbur et al, 2006 | 48.6 (Range 40-65) | 100 | African American | Urban, 60% unmarried, 88% mothers (2.1 children ave.), 70% full time employed, 61% earning > $30 K annually, 57% reporting no 'hardhsips'. | 87% some or full third level education | 4 |

| 9. Baker et al, 2008b | 49 (SD 9) | 78 | NS | NS | NS | 3 |

| 10. Brownson et al 2005 | 18+ | 79.7 | 95% white | 31.3% 35 K+ pa | 45% some or full third level Edu. | 3 |

| 11. Cox et al, 2008 | 55 (Range 50-70) | 100 | NS | Urban, English Speakers, married (76%), employed (56.5%), children (2.83). Non-smokers. | Educated (13 years ave.) | 3 |

| 12. Dinger et al, 2007 | 41.5 years (Range 25-54 years) | 100 | 86% White | Urban, BMI > 30 (57%), access to email | 68% 3rd Level Edu. | 3 |

| 13. Dubbert et al, 2002 | 68.7 yrs (60-80 range) | 1 (99% Male) | 28% Non-white | 56.4% rural, 79.6% married/cohabiting, 12.7% tobacco users, 8.8% in financial hardship, 7.4 hrs per week employment, 20% used alcohol, 3.8 co-morbid medical conditions. | 51.9% high school or more | 3 |

| 14. Dubbert et al, 2008 | Mean 72 (Range 60 to 85 years) | 0 (100% Male) | 14% African-American, 86% White | Urban | Majority high school Educated | 3 |

| 15. Gilson et al, 2008 | 41.4 (SD 10.4) | 91% | NS | All employees at a University | NS | 3 |

| 16. Jancey et al, 2008 | 69 (65-74) | 67 | NS | 67% Australian born, Urban ('Metropolitan Perth'), 66% had a partner | NS | 3 |

| 17. Lamb et al, 2002 | 50.8 (Range 40-70) | 52 | NS | NS | NS | 3 |

| 18. Lee et al, 1997 | 36.5 (Range 23-54) | 100 | Latino, African-American, Asian, Pacific Islanders, other (ns) | "Middle class, well educated, English speaking" | "Well educated" | 3 |

| 19. Matthews et al, 2007 | 53 | 100 | 84% White. 16% African-American/Other | NS | NS | 3 |

| 20. Merom et al, 2007 | 49.1 (Range 30-65) | 85 | NS | Rural and Urban, 74% married, 92.9 English speakers (primarily), 57.7 employed, 72.2% BMI > 25, 90% non-smokers, 81% self rated health good or more. | 45.5% university degree | 3 |

| 21. Ornes and Ransdell, 2007 | 20 (SD 2.6) | 100 | "Mostly Caucasian volunteers" | Students | Undergraduate | 3 |

| 22. Richardson et al, 2007 | 52 (SD 10.5) | 65 | 76% white, 13% black, 10% other | 64% high income > $70,000 | NS | 3 |

| 23. Rosenberg et al, 2009 | 83 (Range 74-92) | 50% | NS | NS | NS | 3 |

| 24. Whitt-Glover et al, 2008 | 52 (Range 20-83) | 89 | Black Americans | Urban, average BMI 34.7, married (49%), 85% had at least one chronic health condition. | 96% high school education or higher | 3 |

| 25. Arbour & Ginis, 2009 | 48.7 (SD 9.61) | 100 | 90% White | 90% Employed | 86% Some or full 3rd Level edu. | 2 |

| 26. Culos-Reed et al, 2008 | 66 (Range 46-83) | 81 | 96% White | 76% retired, 70% higher education, urban | NS | 2 |

| 27. Currie and Develin, 2001 | NS | 100 | NS | NS | NS | 2 |

| 28. Darker et al, 2010 | 40.6 (Range 16-65) | 71 | NS | NS | NS | 2 |

| 29. De Cocker et al 2007 | 48.7 (Range 25-75) | 52.8 | NS | Urban, 68.1% employed, 63.7% reporting good or better than good health | 60% with third level degrees | 2 |

| 30. Dinger et al, 2005 | 41.7 (SD 6.8) (Range 25-54) | 100 | 89% White | Employees or spouses of university employees, Overweight or obese (77.7%), not FT students, not pregnant | University degree (69%) | 2 |

| 31. Engel and Lindner, 2006 | 62 | 46 | NS | NS | NS | 2 |

| 32. Foreman et al, 2001 | NS | Male and Female | NS | NS | NS | 2 |

| 33. Humpel et al, 2004 | 60 (SD 11) | 57% | NS | NS | 46.9% < 12 yrs edu., 32.1% had a trade edu., 21% Uni. | 2 |

| 34. Nies et al, 2006 | 45 (Range 35-60) | 100 | European-American and African-American | 41% > 50 K (US) household income, 49% married, 33% southern American | 74% college edu. or higher | 2 |

| 35. Purath et al, 2004 | 43.9 | 100 | 81.5% White | 100% employed at a university (62% in admin/professional), 92% non-smokers, BMI 30.5, 68% married | 14.25 years edu. (mean) | 2 |

| 36. Shaw et al, 2007 | 40 | 99 | NS | Employed in an urban workplace | NS | 2 |

| 37. Sidman et al, 2004 | 43.2 | 100 | NS | NS | NS | 2 |

| 38. Thomas and Williams, 2006 | 18-50+ | 75.5 | NS | Employed, Both Urban and Rural locations. 'wide variety of professions, ages, incomes, education standards and levels of health and fitness not considered, disadvantaged in terms of the social determinants of health' 'almost all could be described as sedentary' | NS | 2 |

| 39. Tudor-Locke et al, 2002 | 53 (SD 6) | 66 | NS | NS | NS | 2 |

| 40. Baker et al, 2008a | 40 (SD 8.6) | 86 | NS | NS | NS | 1 |

| 41. Hultquist et al, 2005 | 45 (SD 6 yrs) | 100 | 3 non-white among completers | NS | NS | 1 |

| 42. Lomabrd et al, 1995 | 40 (SD 9) | 98 | NS | University staff | NS | 1 |

| 43. DNSWH, 2002 | (Range 25-65) | NS | NS | Suburban | NS | 1 |

| 44. Rovniak, 2005 | Men (Range 20-44) Women (Range 20-54) | 93.5 | NS | Urban, at least access to email, sedentary, no more than one health risk factor, BMI < 39.9, no metabolic, pulmonary or CV disease, no bone joint or foot problems, not pregnant. | NS | 1 |

| 45. Rowley et al, 2007 | Children 0-4 Adults not reported |

100 (Adults) Children not reported | 'There were no children or babies from ethnic minority groups'. | Affluent' | NS | 1 |

| 46. Talbot et al, 2003 | 69 (SD 6) | 76 | 17% Non-White | 60% > $30 K pa | NS | 1 |

| 47. Wyatt et al, 2004 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | 1 |

Recruitment data reported

Two studies reported all data for all components of recruitment, i.e. where recruitment took place; who conducted the recruitment; the time taken to conduct the planning/preparing and delivery stages [27,51]. Thirty nine studies did report a specified target group (Table 4-Recruitment planning/preparing and implementation). Forty four studies provide some details of where recruitment was conducted [27-49,51-56,58-67,69-73] but the recruitment location was often given vague descriptions, for example "in the community". Most popular were medical/care settings (n = 12) [29-31,33,34,36,38,43,49,51,55,63] or universities (n = 9) [37,40,41,43,44,46,47,62,70]. Other community settings included for example, places of worship [67], hair salons [29], food establishments [29,71] or specific events within such settings, for example meetings for new mothers [51].

Table 4.

Recruitment planning and implementation (Quality Metric categories)

| Study Author (Year) | Where did the Recruitment take place? | Who did the Recruitment? | Time spent Planning/Preparing recruitment | Time spent Executing recruitment (Weeks) | Population Targeted (Yes/No)? | Quality Metric score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| l. Watson et al, 2005 | Home, health centre visits, at mothers group meetings | Nurses trained in recruitment and research staff | 1 month including all training of nurses and intervention by researchers to help with recruitment difficulties. | 6 weeks | Yes | 5 |

| 2. Banks-Wallace et al, 2004 | In the community at venues typically used for hosting African American community events | Recruitment Protocol Specialist | NS | 21.6 weeks | Yes | 4 |

| 3. Kolt et al, 2006 | By mail and a follow up home visit | Researchers | NS | 39 weeks | Yes | 4 |

| 4. Nguyen et al, 2002 | Mainly passively in the community but also used press conferences and info/taster sessions | Public health official | 3 years (Rolling development) | NS | Yes | 4 |

| 5. Prestwich et al, 2010 | University | Researchers | NS | 2.5 weeks | Yes | 4 |

| 6. Rowland et al, 2004 | Via telephone, direct mail and then at multiple locations and media in the community | Research team members | NS | 43.3 weeks | Yes | 4 |

| 7. Sherman et al, 2006 | In a clinic, hair salons-and food establishments | Nurses | NS | 0.28 weeks | Yes | 4 |

| 8. Wilbur et al, 2006 | Two federally qualified community health centres serving poor and working class urban populations. Screening and data collection was carried out here to reduce power differences (perceived) and increase trust. Concentrated on an area within a 3-mile radius of the data collection sites. Also interacted in the community at health fairs and presentations. | Team specifically set up to deliver the recruitment made up of AA female nurses, either living in the community or who had family ties to the community. | NS | 121.3 weeks | Yes | 4 |

| 9. Baker et al, 2008b | Local community, GP surgeries, shops, community stalls | NS | NS | 21.6 months | Yes | 3 |

| 10. Brownson et al 2005 | Through media, at physicians practices, at community centres, on walking routes, in the community active and passively | Community organisation staff, research staff, physicians | NS | NS | Yes | 3 |

| 11. Cox et al, 2008 | Ads delivered in the community. Screening took place at the community centre | Research assistants | NS | NS | Yes | 3 |

| 12. Dinger et al, 2007 | Local media and electronically | NS | NS | 4.3 weeks | Yes | 3 |

| 13. Dubbert et al, 2002 | By mail, phone and at the clinic | Researchers and Research Nurse | NS | NS | Yes | 3 |

| 14. Dubbert et al, 2008 | Primary care medical centre as part of routine care | NS | 2 to 3 years | NS | Yes | 3 |

| 15. Gilson et al, 2008 | Via work email | Researchers | NS | NS | Yes | 3 |

| 16. Jancey et al, 2008 | Over the phone to home phone numbers | Researchers | NS | NS | Yes | 3 |

| 17. Lamb et al, 2002 | Via post, phone and info sessions at primary care setting | Researchers, via GP, and staff nurse | NS | NS | Yes | 3 |

| 18. Lee et al, 1997 | Directly and indirectly in the community | Female students trained in recruitment methods | NS | NS | Yes | 3 |

| 19. Matthews et al, 2007 | Clinic | Clinical staff | NS | NS | Yes | 3 |

| 20. Merom et al, 2007 | Passively in the community and actively by phone via another study | Researchers in the NSW Health survey (recruitment by proxy) and researchers on this study | NS | NS | Yes | 3 |

| 21. Ornes and Ransdell, 2007 | University campus | Researchers | NS | NS | Yes | 3 |

| 22. Richardson et al, 2007 | Medical centre | Physicians | NS | NS | Yes | 3 |

| 23. Rosenberg et al, 2009 | Care community | Researchers | NS | NS | Yes | 3 |

| 24. Arbour & Ginis, 2009 | University and Local Community | NS | NS | NS | Yes | 2 |

| 25. Baker et al, 2008a | University campus | NS | NS | NS | NS | 2 |

| 26. Culos-Reed et al, 2008 | In the community and at the malls | NS | NS | 2 weeks | No | 2 |

| 27. Currie and Develin, 2001 | Places where pre and post natal mums engage with health care, shopping and school | NS | NS | NS | Yes | 2 |

| 28. Darker et al, 2010 | In the local media (Passive) | NS | NS | 30.3 weeks | No | 2 |

| 29. De Cocker et al 2007 | By mail or phone to participants homes. Indirect but active | NS | NS | NS | Yes | 2 |

| 30. Dinger et al, 2005 | University | NS | NS | NS | Yes | 2 |

| 31. Engel and Lindner, 2006 | In community via newspapers | NS | NS | NS | Yes | 2 |

| 32. Foreman et al, 2001 | NS | Walk leaders and organisers | NS | NS | Yes | 2 |

| 33. Humpel et al, 2004 | Via post. No face to face | NS | NS | NS | Yes | 2 |

| 34. Nies et al, 2006 | Through media and fliers in the community | NS | NS | NS | Yes | 2 |

| 35. Purath et al, 2004 | Health screening day within a university | NS | NS | NS | Yes | 2 |

| 36. Shaw et al, 2007 | Workplace (Health centre) | NS | NS | NS | Yes | 2 |

| 37. Sidman et al, 2004 | Two University campuses | NS | NS | NS | Yes | 2 |

| 38. Thomas and Williams, 2006 | Workplace (Electronically) | NS | NS | NS | Yes | 2 |

| 39. Tudor-Locke et al, 2002 | Diabetes Centre | NS | NS | NS | Yes | 2 |

| 40. Whitt-Glover et al, 2008 | At churches | Church pastors and researchers | NS | NS | Yes | 2 |

| 41. Hultquist et al, 2005 | University | NS | NS | NS | No | 1 |

| 42. Lomabrd et al, 1995 | University campus | NS | NS | NS | No | 1 |

| 43. DNSWH, 2002 | In local area via media and advertising and information | NS | NS | NS | No | 1 |

| 44. Rovniak, 2005 | At multiple locations in the community. Mainly passive. | NS | NS | NS | No | 1 |

| 45. Rowley et al, 2007 | NS | NS | NS | NS | Yes | 1 |

| 46. Talbot et al, 2003 | Senior centres, ads in local newspapers | NS | NS | NS | NS | 1 |

| 47. Wyatt et al, 2004 | NS | NS | NS | NS | Yes | 1 |

Twenty one studies reported who conducted the study recruitment. Most popular recruiters were research staff [28,31,33,34,37,39,51,52,54,62,64,67,72], often with assistance from health professionals like doctors or nurses [29,33,51,65]. Five studies reported using a dedicated "recruitment specialist" [27,30,35,51,69]. Only three studies reported the time spent planning/preparing their recruitment phases [34,51,69]. Eleven studies reported the time spent on implementing recruitment [27-30,32,51,62,63,71,72] and this averaged as 35 weeks, with a range of 2 days to 56 weeks.

Recruitment procedures and approaches

The reporting of recruitment methods was often sparse and unstructured (Table 5-Number of methods and types of recruitment procedures). Forty five studies provided data on the number of recruitment methods used (mean 2.7, SD 1.97). Sixteen studies relied on one method of recruitment only [33,34,43-45,50-53,56,58,60,62,64,65,72], and 26 studies used between two and four methods [27-32,35-41,54,55,63,66,69-71,73]. We identified two types of recruitment approaches, (i) active approaches; a recruitment method that requires those conducting the study to make the first contact with a participant (e.g. phone calls, face to face invitation, word of mouth, referrals), (ii) passive approaches; a recruitment method that requires a potential participant makes the first contact with the study (e.g. posters, leaflets drops, newspaper advertisements, mail outs). We did not observe any relationship between the quality of recruitment reporting and the number of recruitment strategies used. We did however observe that a number of studies used only passive techniques (n = 21) [32,34,38,41,42,44,46-48,52,54,56,58-62,64,66,67,70], some used a mixture of active and passive techniques (n = 22) [27-31,33,35-37,39,40,49,53,55,57,63,65,68,69,71-73] and a small number used solely active only methods (n = 4) [43,45,50,51].

Table 5.

Recruitment planning and implementation (Quality Metric categories)

| Study Author (Year) | No. Of Methods Used | Procedures including who conducted the recruitment, where it took place and what was done | Active, passive or a mixture of approaches | Quality Metric Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| l. Watson et al, 2005 | 1 | Nurse conducted face to face recruitment at clinics, mothers' group meetings and home visits. | Active | 5 |

| 2. Banks-Wallace et al, 2004 | 4 | Researchers placed flyers in church bulletins and the community, health practitioner referrals were generated, word of mouth was used and structured pre-intervention meetings took place. | Passive/Active | 4 |

| 3. Kolt et al, 2006 | 1 | A three phased and sequenced approach was conducted by the researchers, the GP and staff nurse. An invitation letter was sent from the GP surgery a pre-paid response card for those expressing interest. Follow up screening calls then follow up visits to provide info and gain consent. | Passive/Active | 4 |

| 4. Nguyen et al, 2002 | 3 | A public health official co-ordinated the recruitment and used the local media, network construction and face to face recruitment of volunteer walk leaders. Press conferences and promotional materials were sent to local media outlets, community health centres, libraries, senior's club networks to promote the club. Leaflets on local community settings, ads in free newspapers, promotional messages placed on light panels around the city, community TV ads and features, press releases for local media, newsletters, press conference, celebration events. Comments elsewhere stated that face to face recruitment was the most successful for this study, but this was only used to recruit walk leaders. | Passive/Active | 4 |

| 5. Prestwich et al, 2010 | 1 | Researchers sent emails to the current students at their university. Course credit or cash were used as an incentive. | Passive | 4 |

| 6. Rowland et al, 2004 | 11 | Computer assisted telephone interviews (CATI) was initially conducted by researchers. A database of potential participants was screened for telephone numbers. If this was not successful in recruiting the sample size needed the direct mailing was used. Finally, to complete the sample size quota canvassing in the local community (including face to face, door to door, posters and flyers at churches and senior housing units, snowballing, utilising 'community brokers', and newspapers) was conducted. Recruitment was systematic, purposeful and carried out in the order described but was somewhat inequitable as the first screening criterion was the availability of a phone number. It also required significant community assistance to reach those harder to engage. | Active/Passive | 4 |

| 7. Sherman et al, 2006 | 2 | Active recruitment by a nurse at a health clinic, advertisements in hair salons and food establishments. The paper states that the 'main source of recruitment came from advertisements in the community and word of mouth'. | Active/Passive | 4 |

| 8. Wilbur et al, 2006 | 3 | Researchers designed a flyer with community input and received advice on where to place it. Emails and newspaper announcements were also used. Recruitment staff distributed print material at specified schools, churches, grocery shops, libraries, clinics, community agencies and community fairs and at 10 presentations in community agencies, clinics, and churches. Email announcement at local medical centre workplaces and an announcement in the community newspaper were used. A good aim of matching the invitation to the invitee and finding the best place to distribute it was a positive here. Unfortunately word of mouth wasn't actively used or reported and only the research team recruitment staff acted as recruiters for face to face recruitment. | Passive/Active | 4 |

| 9. Baker et al, 2008b | 4 | Mail drops were carried out and adverts were placed in local papers and posters in GP surgeries and shops. Manned community stalls were also set up. This approach was modified and expanded throughout the recruitment phase as the researchers identified their lack of impact on the target group. However, the methods were mainly passive and not altered to be more engaging or mediating with the target group. It is not specifically stated who conducted the recruitment. | Passive/Active | 3 |

| 10. Brownson et al 2005 | 8 | Recruitment was initially by proxy during a baseline survey for another piece of work (no details or what survey was). Awareness of the walking group was also promoted at community events, by physician recommendation, trail signage advertising and word or mouth. Recruitment methods were not explicitly reported but intervention communities used participatory approaches to develop their intervention options. Taster events, one off walks, clean up trail days, and 5 media events were held. | Passive/Active | 3 |

| 11. Cox et al, 2008 | 1 | Research assistants placed advertisements in the local community. | Passive | 3 |

| 12. Dinger et al, 2007 | 3 | Flyers were placed in the community, emails were sent to university staff and a television advertisement was broadcast. It is not specifically stated who conducted the recruitment. | Passive | 3 |

| 13. Dubbert et al, 2002 | 1 | A three phased sequenced approach was used. Researchers and a research nurse reviewed medical records. Potential participants were sent a letter and recruited during their scheduled visits with the primary health care providers or following an expression of interest. Nurses conducted a pre screening and financial compensation to offset costs of visits to the centre was provided. | Active/Passive | 3 |

| 14. Dubbert et al, 2008 | 1 | Participants were recruited via referral by primary care providers, but which specific type of care provider was not reported. It is not specifically stated who conducted the recruitment. | Passive | 3 |

| 15. Gilson et al, 2008 | 1 | Researchers recruited participants via workplace email. | Passive | 3 |

| 16. Jancey et al, 2008 | 1 | A two phased sequenced approach was used. Researchers marched electoral roll lists against telephone directory lists to identify potential participants who owned phones. A preceding postcard informing the recruit about the study and the likelihood of a phone call to follow. Phone calls were then made by members of the research team and approximately 9 calls were required to recruit one participant. | Passive/Active | 3 |

| 17. Lamb et al, 2002 | 1 | A three phased sequenced approach was used. Researchers, assisted by staff nurses sent an eligibility questionnaire to a randomly selected group from a GP client list (GP letters included). This was followed by a letter explaining the study to those expressing an interest and then a phone call to the responders to arrange which info session they could attend. | Passive/Active | 3 |

| 18. Lee et al, 1997 | 4 | Researchers and trained female students conducted telephone calls, face to face approaches at supermarkets, direct mailing and flyers. | Passive/Active | 3 |

| 19. Matthews et al, 2007 | 3 | Clinical staff recruited women by letter and phone follow up in two health centres. The paper also states that in another centre clinical populations were recruited, but this is not clearly explained. Women who were also past participants in a case control study and had agreed to take part in future research. | Active/Passive | 3 |

| 20. Merom et al, 2007 | 3 | Invitation by proxy during the NSW phone Health Survey. Researchers in this study then produced a community based newspaper and sent intranet messages in the area health services (it is not clear what they meant by that). | Passive | 3 |

| 21. Ornes and Ransdell, 2007 | 4 | Researchers placed newspaper ads and posters on a university campus. Researcher also visited classes on college campus and conducted face to face recruitment on campus. | Passive/Active | 3 |

| 22. Richardson et al, 2007 | 3 | Researchers placed adverts in a local newspaper and flyers at local hospital, clinics, and other public locations. A listing was placed on a medical research recruitment site. Information and water bottles were given to potential participants and doctors to raise the profile of the study and encourage referrals from doctors. | Passive | 3 |

| 23. Rosenberg et al, 2009 | 2 | Researchers used flyers and information meetings. | Passive/Active | 3 |

| 24. Whitt-Glover et al, 2008 | 5 | Pastors who attended luncheons regarding health promotion and disease prevention strategies among African Americans were recruited to help introduce the intervention and aid recruitment of participants. Following this, researchers placed flyers in churches, bulletins in newsletters, announcements at Sunday services and held information meetings. | Active/Passive | 3 |

| 25. Arbour & Ginis, 2009 | 2 | Posters and internet ads were sent as part of an employee health programme. It is not specifically stated who conducted the recruitment. | Passive | 2 |

| 26. Culos-Reed et al, 2008 | 4 | Posters, cards on food hall tables and two community newspapers were used to circulate information. Three presentations were held at local health programme meetings. It is not stated who conducted the recruitment. | Passive/Active | 2 |

| 27. Currie and Develin, 2001 | 4 | Flyers were placed at the local maternity wards, doctors' surgeries, early childhood centres, day care centres, immunization clinics, baby product stores and playgrounds. Adverts placed in school bulletins; local newspapers and also paid adverts in newspapers. Information sessions were conducted for new mothers in childhood centres. It is not specifically stated who conducted the recruitment. | Passive/Active | 2 |

| 28. Darker et al, 2010 | 2 | Adverts were placed in local newspapers. Radio interviews were conducted. It is not specifically stated who conducted the recruitment. | Passive | 2 |

| 29. De Cocker et al 2007 | 3 | Telephone calls and postal mail invites to 2500 randomly selected members of the registered population. A multi-media campaign was carried out to raise awareness of the programme. It is not specifically stated who conducted the recruitment. | Active/Passive | 2 |

| 30. Dinger et al, 2005 | 2 | Emails were sent to university staff and adverts were placed on the University television station. It is not specifically stated who conducted the recruitment. | Passive | 2 |

| 31. Engel and Lindner, 2006 | 1 | A 'local Media campaign' was conducted. It is not specifically stated who conducted the recruitment. | Passive | 2 |

| 32. Foreman et al, 2001 | 2 | This qualitative paper did not clearly describe the processes behind their recruitment approach. It emphasises the need for the walk leaders and organisers to become actively engaged in the process and how interpersonal approaches are highly necessary and more effective in engaging a broader range of participants or specific target groups. | Active/Passive | 2 |

| 33. Humpel et al, 2004 | 1 | Letters were sent to individuals listed in an insurance company client list, with follow up letters to non-responders. It is not specifically stated who conducted the recruitment. | Passive | 2 |

| 34. Nies et al, 2006 | 2 | Flyers were placed in the local community and the programme was promoted on the radio. It is not specifically stated who conducted the recruitment. | Passive | 2 |

| 35. Purath et al, 2004 | 1 | Participants were recruited at annual workplace health screenings. May have been pre-notified but this isn't stated. It is not specifically stated who conducted the recruitment. | Active | 2 |

| 36. Shaw et al, 2007 | 4 | The study was promoted via workplace intranet, staff newsletter and flyers. Emails were sent to managers of departments to be forwarded to staff. It is not specifically stated who conducted the recruitment. | Passive | 2 |

| 37. Sidman et al, 2004 | 1 | Flyers were posted on two University campuses. It is not specifically stated who conducted the recruitment. | Passive | 2 |

| 38. Thomas and Williams, 2006 | 1 | Emails were distributed in the workplace. It is not specifically stated who conducted the recruitment. | Passive | 2 |

| 39. Tudor-Locke et al, 2002 | 1 | Recruited at/after an diabetes education session. Convenience sample, first come first serve. It is not specifically stated who conducted the recruitment. | Active | 2 |

| 40. Baker et al, 2008a | 3 | Posters and newsletters were placed on a University campus. Emails were sent to University staff. It is not specifically stated who conducted the recruitment. | Passive | 1 |

| 41. Hultquist et al, 2005 | 2 | Flyers were placed on a University campus and in the surrounding area. The study was publicised in a local newsletter. It is not specifically stated who conducted the recruitment. | Passive | 1 |

| 42. Lomabrd et al, 1995 | 2 | Newspaper advertisements and flyers were posted on campus at a University. It is not specifically stated who conducted the recruitment. | Passive | 1 |

| 43. DNSWH, 2002 | 4 | Flyers distributed via letter box drop. Use of a 'feature' newspaper article. Information sent to local community groups (e.g. Rotary and Lions), schools, preschools, playgroups, community nurses, doctors' surgeries, local rugby club, and local business (e.g. chemists' shops, real estate agents, car dealerships). Poster and flyers placed in parks, at bus stops, local streets, shops, libraries and other public facilities. It is not specifically stated who conducted the recruitment. | Passive | 1 |

| 44. Rovniak, 2005 | 5 | The methods are reported as: the use of local list-servs for direct mailing; churches; a news brief on a local radio and television station, a university newspaper article, and flyers. It is not specifically stated who conducted the recruitment. | Passive | 1 |

| 45. Rowley et al, 2007 | Unclear | The paper reports only the following details regarding recruitment: 'There was an enthusiastic response from invited mothers and many requests to join from other who had heard about the programme through local publicity and word of mouth'. It is not specifically stated who conducted the recruitment. | Passive/Active | 1 |

| 46. Talbot et al, 2003 | 2 | Participants were recruited through senior centres and advertisements in local newspapers. It is not specifically stated who conducted the recruitment. | Passive/Active | 1 |

| 47. Wyatt et al, 2004 | 1 | Word of mouth at a 'kick start' session. It is not specifically stated who conducted the recruitment. | Active | 1 |

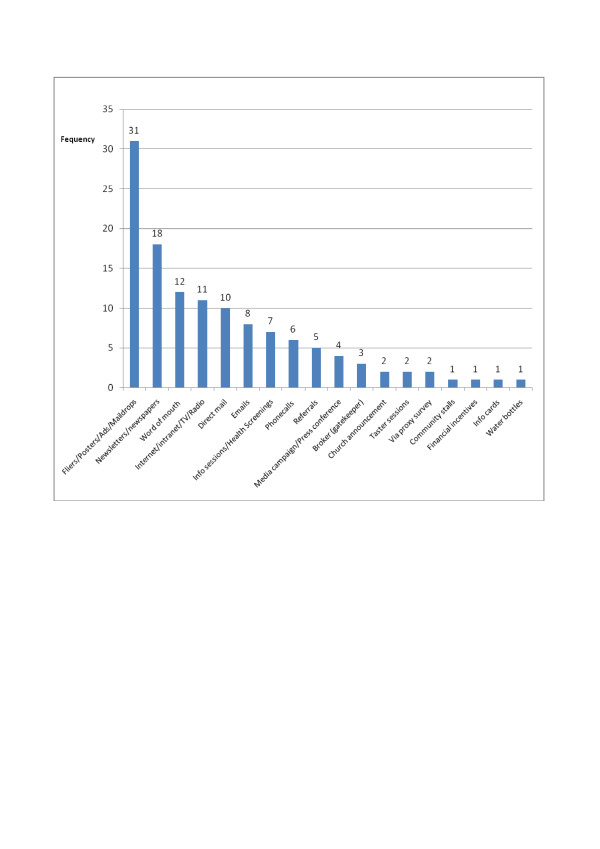

Passive recruitment methods, which require no interaction with the potential participants, were popular (Figure 2). Flyers/posters/advertisements/mail drops were the most cited approach used, appearing in 31 studies. This was almost twice as prevalent as the second most popular approach, newsletters/newspaper articles (n = 18) and was nearly three times more frequently used than word of mouth. Word of mouth appeared in 12 studies, but we were unable to identify whether this was a proactive recruitment strategy or a reactive strategy, responding to low recruitment numbers. Less popular methods included medical and health insurance referral, invitations derived from clinical or employment data, study information sessions, resident listings, announcements at group meetings or community events and information stands.

Figure 2.

Methods of recruitment and frequency of use from all included studies (n = 47).

Locations for recruitment, interventions and target populations

Table 6 presents data on the setting and location of recruitment and the study. We observed some studies that "matched" where the recruitment was conducted with where the intervention was delivered. Culos-Reed et al, 2008 reported recruiting participants for a mall walking study at the mall where the intervention was going to be delivered [71]. Other studies did not match in this way, and recruited in many different locations, often relying on print material alone, and requiring potential participants to attend a location which may not be easily accessible to them. Studies reported that they were "community-based" (n = 25) [27-31,35,36,42,48-52,54-58,61,63,68,69,71-73] but asked community members to travel into a research setting to begin the process of participation; for example medical centres or universities (n = 20) [29,30,33-38,41,43,46,47,49,56,62-67]. These interventions used a mixture of recruitment approaches including media events and led walking groups, face to face interventions (e.g. counselling, pedometers) or mediated interventions, such as internet, e-health and mobile phone technology [74].

Table 6.

Settings and Locations of recruitment, study and populations

| Study Author (Year) | Stated Study setting | Target population | Where did the Recruitment take place? | Intervention delivery site | Where Participants came from | Quality Metric Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| l. Watson et al, 2005 | Community | Post-natal mothers | Home, health centre visits, at mothers group meetings | Community via lead walks | Mothers using community health centres or early childhood health centres or mothers visited by local childcare nurses | 5 |

| 2. Banks-Wallace et al, 2004 | Community Setting: African American (AA) | African American women in a local community (Minority group) | In the community at venues typically used for hosting African American community events | Local community venue used for hosting AA community events | African American Community | 4 |

| 3. Kolt et al, 2006 | Community | Older sedentary adults (> 65) | By mail and a follow up home visit | By phone and a home visit at screening (Community) | GP Patient lists | 4 |

| 4. Nguyen et al, 2002 | Community | General community | Mainly passively in the community but also used press conferences and info/taster sessions | Community | 4 | |

| 5. Prestwich et al, 2010 | University | University students | University | University | University students | 4 |

| 6. Rowland et al, 2004 | Community | Sedentary older adults | Via telephone, direct mail and then at multiple locations and media in the community | At home | Community members identified through a commercial database of household data | 4 |

| 7. Sherman et al, 2006 | Community (Rural) | Rural women | In a clinic, hair salons-and food establishments | Clinical centre | Residents in the local community | 4 |

| 8. Wilbur et al, 2006 | Community and Home | African American Women | Two federally qualified community health centres serving poor and working class urban populations. Screening and data collection was carried out here to reduce power differences (perceived) and increase trust. Concentrated on an area within a 3-mile radius of the data collection sites. Also interacted in the community at health fairs and presentations. | Community health centres. Purposely chosen to reduce power differences and increase trust. Within three miles of the participants residential area | Predominantly African American women within a 3-mile radius of the intervention centre | 4 |

| 9. Baker et al, 2008b | Community | Community members in areas of high deprivation (> 15% SIMD) | Local community, GP surgeries, shops, community stalls | University campus | Residents within a surrounding area of West Glasgow university (1.5 km)-defined as a suitable walking distance from intervention site | 3 |

| 10. Brownson et al 2005 | Community (Rural USA) | Rural community members | Through media, at physicians practices, at community centres, on walking routes, in the community active and passively | Community | Within targeted community | 3 |

| 11. Cox et al, 2008 | Community | Previously sedentary older women | Ads delivered in the community. Screening took place at the community centre | Community centre | Recruited from the community' | 3 |

| 12. Dinger et al, 2007 | University | Insufficiently active women (University staff and local community members) | Local media and electronically | Intervention delivered by email (Virtual) | University staff and local community | 3 |

| 13. Dubbert et al, 2002 | Care setting (Veterans Affairs Medical Centre) | Elderly primary care patients | By mail, phone and at the clinic | Medical centre | Attendees at a Veterans Affairs Medical centre | 3 |

| 14. Dubbert et al, 2008 | Care setting | Elderly veterans | Primary care medical centre as part of routine care | Primary care clinic | Primary care clinics for veterans | 3 |

| 15. Gilson et al, 2008 | Workplace (University) | Work-place employees | Via work email | University | University employees | 3 |

| 16. Jancey et al, 2008 | Community | Older adults | Over the phone to home phone numbers | Selected green space areas within the neighbourhood local to the recruited participants | Urban areas of Perth, identified through electoral roll | 3 |

| 17. Lamb et al, 2002 | Care (Primary care) | Middle aged adults | Via post, phone and info sessions at primary care setting | Primary care facilities | Primary care client list | 3 |

| 18. Lee et al, 1997 | Community | Sedentary ethnic minority women | Directly and indirectly in the community | Baseline screening at a University, then indirectly delivered to participants homes | Members of women, children and infant groups, local area San Diego | 3 |

| 19. Matthews et al, 2007 | Care: Clinical and Home (Community) setting | Breast cancer survivors | Clinic | Clinical centres | Former or existing clinical populations | 3 |

| 20. Merom et al, 2007 | Community | Inactive adults | Passively in the community and actively by phone via another study | This was a passively delivered intervention and participants received intervention material and equipment entirely by post. | Non-clinical sample of individuals in the community | 3 |

| 21. Ornes and Ransdell, 2007 | University | Women | University campus | University | University | 3 |

| 22. Richardson et al, 2007 | Care: Clinical | Adults with type 2 diabetes | Medical centre | Clinical centre | Adults with diabetes living in the community | 3 |

| 23. Rosenberg et al, 2009 | Care setting (Retirement community) | Older adults | Care community | Continuing care retirement community | Residential care facility | 3 |

| 24. Whitt-Glover et al, 2008 | Churches | Black adult, church attendees | University and Local Community | Church meeting rooms | Church groups | 3 |

| 25. Arbour & Ginis, 2009 | Workplace | Women in the workplace | University campus | Workplace (University) | University | 2 |

| 26. Culos-Reed et al, 2008 | Community: Malls | NS | In the community and at the malls | Mall | Mall users from the local community | 2 |

| 27. Currie and Develin, 2001 | Community | Mothers and young children | Places where pre and post natal mums engage with health care, shopping and school | Community | NS | 2 |

| 28. Darker et al, 2010 | Clinical lab setting | NS | In the local media (Passive) | Laboratory | NS | 2 |

| 29. De Cocker et al 2007 | Community | 'General population' adults in a local community | By mail or phone to participants homes. Indirect but active | In the community with contact via phone and mail for pedometer packs | General population members as listed on the population register | 2 |

| 30. Dinger et al, 2005 | University | Female employees or spouses of university employees | University | University campus | University staff and spouses | 2 |

| 31. Engel and Lindner, 2006 | Community | Adults with type 2 diabetes | In community via newspapers | At research institute or at home | Local Community | 2 |

| 32. Foreman et al, 2001 | Community | Community members | NS | NS | NS | 2 |

| 33. Humpel et al, 2004 | Community | Over 40 year old community members | Via post. No face to face | No face to face contact, but participants encouraged to walk in their local area | Insurance company client list | 2 |

| 34. Nies et al, 2006 | Community | European American and African America women. | Through media and fliers in the community | NS | NS | 2 |

| 35. Purath et al, 2004 | Workplace (University) | Women in the workplace | Health screening day within a university | University | Staff attending a voluntary university provided health screening as part of a wellness programme | 2 |

| 36. Shaw et al, 2007 | Workplace (Health Centre staff) | Men and women in the workplace | Workplace (Health centre) | Workplace (Urban workplace) | Health Centre staff | 2 |

| 37. Sidman et al, 2004 | University (Seems Uni) | Sedentary women | Two University campuses | NS | NS (Recruited on Uni campus) | 2 |

| 38. Thomas and Williams, 2006 | Workplace | Workplace staff (Excluding hospital and community services staff) | Workplace (Electronically) | NS | Workplace staff (Dept. of Human Services staff) | 2 |

| 39. Tudor-Locke et al, 2002 | Health centre | Sedentary diabetes sufferers | Diabetes Centre | Diabetes care centre | Diabetes care centre | 2 |

| 40. Baker et al, 2008a | University | NS | At churches | University campus | University campus | 1 |

| 41. Hultquist et al, 2005 | University | NS | University | University | University campus | 1 |

| 42. Lomabrd et al, 1995 | University | NS | University campus | University | University staff | 1 |

| 43. DNSWH, 2002 | Community | NS | In local area via media and advertising and information | Community | Residents of local community | 1 |

| 44. Rovniak, 2005 | Community | NS | At multiple locations in the community. Mainly passive. | NS | NS (Seems community) | 1 |

| 45. Rowley et al, 2007 | Community | Parents and children | NS | In the community along planned walking routes in and out of parks/green spaces | Affluent community in semi-rural England' | 1 |

| 46. Talbot et al, 2003 | Community (Home) | Older adults | Senior centres, ads in local newspapers | University clinic | Local Community | 1 |

| 47. Wyatt et al, 2004 | Community | State wide residents of the community | NS | Worksite and Church via a starter kit | Workplaces and church | 1 |

Recruitment rates and efficiencies

We originally planned to calculate recruitment rates and efficiency ratios for each study but we were unable to do so due to missing data (Table 7-Recruitment rates and efficiency ratios). Only three studies provided all the data points [33,36,65]. We were able to calculate a weekly recruitment rate using the final numbers of participants divided by the time spent recruiting in weeks for eleven studies (mean 38 participants per week, range 1 to 268 participants per week). We were not able to see any pattern between recruitment approaches and weekly rates. Two studies reported some data on the efforts needed to undertake recruitment. Jancey et al (2008) reported that after potential participants had received invitation cards it took approximately 9 calls to recruit one participant [53].

Table 7.

Recruitment rates and efficiency ratios

| Study Author (Year) | Pool | Invited | Responded | Started | Efficiency A (%) (Started/Pool) | Efficiency B (%) (Started/Invited) | Efficiency C (%) (Started/Responded) | Efficiency D (N) (Started only) |

Weekly Recruitment Rate | Quality Metric Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| l. Watson et al, 2005 | NS | NS | NS | 139 | - | - | 139.0 | 23.17 | 5 | |

| 2. Banks-Wallace et al, 2004 | NS | NS | 38 | 21 | - | - | 55.3 | 21.0 | 0.97 | 4 |

| 3. Kolt et al, 2006 | NS | NS | NS | 186 | - | - | - | 186.0 | 4.77 | 4 |

| 4. Nguyen et al, 2002 | NS | NS | NS | NS | - | - | - | NS | 4 | |

| 5. Prestwich et al, 2010 | NS | NS | 173 | 149 | - | - | 86.1 | 149.0 | 59.60 | 4 |

| 6. Rowland et al, 2004 | 73828 | NS | NS | 582 | 0.8 | - | - | 582.0 | 13.44 | 4 |

| 7. Sherman et al, 2006 | 1700 | NS | 75 | 75 | 4.4 | - | 100.0 | 75.0 | 267.86 | 4 |

| 8. Wilbur et al, 2006 | NS | NS | NS | 281 | - | - | - | 281.0 | 2.32 | 4 |

| 9. Baker et al, 2008b | NS | NS | 169 | 80 | - | - | 47.3 | 80.0 | 3.70 | 3 |

| 10. Brownson et al 2005 | NS | NS | NS | NS | - | - | - | - | 3 | |

| 11. Cox et al, 2008 | NS | NS | 1312 | 124 | - | - | 9.5 | 124.0 | 3 | |

| 12. Dinger et al, 2007 | NS | NS | 87 | 74 | - | - | 85.1 | 74.0 | 17.21 | 3 |

| 13. Dubbert et al, 2002 | 576 | 576 | 253 | 212 | 36.8 | 36.8 | 83.8 | 212.0 | 3 | |

| 14. Dubbert et al, 2008 | 572 | 572 | NS | 224 | 39.2 | 39.2 | - | 224.0 | 3 | |

| 15. Gilson et al, 2008 | NS | NS | 102 | 70 | - | - | 68.6 | 70.0 | 3 | |

| 16. Jancey et al, 2008 | NS | 7378 | NS | 260 | - | 3.5 | - | 260.0 | 3 | |

| 17. Lamb et al, 2002 | 26500 | 2000 | 960 | 260 | 1.0 | 13.0 | 27.1 | 260.0 | 3 | |

| 18. Lee et al, 1997 | NS | NS | 387 | 128 | - | - | 33.1 | 128.0 | 3 | |

| 19. Matthews et al, 2007 | 117 | 117 | 102 | 36 | 30.8 | 30.8 | 35.3 | 36.0 | 3 | |

| 20. Merom et al, 2007 | NS | NS | 692 | 369 | - | - | 53.3 | 369.0 | 3 | |

| 21. Ornes and Ransdell, 2007 | NS | NS | 210 | 121 | - | - | 57.6 | 121.0 | 3 | |

| 22. Richardson et al, 2007 | NS | NS | 76 | 35 | - | - | 46.1 | 35.0 | 3 | |

| 23. Rosenberg et al, 2009 | 400 | 400 | NS | 22 | 5.5 | 5.5 | - | 22.0 | 3 | |

| 24. Whitt-Glover et al, 2008 | NS | NS | NS | 87 | - | - | - | 87.0 | 3 | |

| 25. Arbour & Ginis, 2009 | NS | NS | 129 | 75 | - | - | 58.1 | 75.0 | 2 | |

| 26. Culos-Reed et al, 2008 | NS | NS | 87 | 52 | - | - | 59.8 | 52.0 | 26.00 | 2 |

| 27. Currie and Develin, 2001 | NS | NS | 110 | NS | - | - | - | NS | 2 | |

| 28. Darker et al, 2010 | NS | NS | 176 | 132 | - | - | 75.0 | 132.0 | 4.36 | 2 |

| 29. De Cocker et al 2007 | 5000 | 4065 | NS | 1674 | 33.5 | 41.2 | - | 1674.0 | 2 | |

| 30. Dinger et al, 2005 | NS | NS | 43 | 36 | - | - | 83.7 | 36.0 | 2 | |

| 31. Engel and Lindner, 2006 | NS | NS | NS | 57 | - | - | - | 57.0 | 2 | |

| 32. Foreman et al, 2001 | NS | NS | NS | NS | - | - | - | NS | 2 | |

| 33. Humpel et al, 2004 | NS | 982 | 429 | 399 | - | 40.6 | 93.0 | 399.0 | 2 | |

| 34. Nies et al, 2006 | NS | NS | 313 | 253 | - | - | 80.8 | 253.0 | 2 | |

| 35. Purath et al, 2004 | NS | NS | NS | 287 | - | - | - | 287.0 | 2 | |

| 36. Shaw et al, 2007 | NS | NS | NS | 35 | - | - | - | 35.0 | 2 | |

| 37. Sidman et al, 2004 | NS | NS | NS | 114 | - | - | - | 114.0 | 2 | |

| 38. Thomas and Williams, 2006 | 3500 | NS | 1195 | 1195 | 34.1 | - | 100.0 | 1195.0 | 2 | |

| 39. Tudor-Locke et al, 2002 | NS | 9 | 9 | 9 | - | 100.0 | 100.0 | 9.0 | 2 | |

| 40. Baker et al, 2008a | NS | NS | 61 | 52 | - | - | 85.2 | 52.0 | 1 | |

| 41. Hultquist et al, 2005 | NS | NS | 73 | 58 | - | - | 79.5 | 58.0 | 1 | |

| 42. Lomabrd et al, 1995 | 5000 | NS | NS | 135 | 2.7 | - | - | 135.0 | 1 | |

| 43. DNSWH, 2002 | NS | NS | NS | NS | - | - | - | NS | 1 | |

| 44. Rovniak, 2005 | NS | NS | 235 | 65 | - | - | 27.7 | 65.0 | 1 | |

| 45. Rowley et al, 2007 | NS | NS | NS | 165 | - | - | - | 165.0 | 1 | |

| 46. Talbot et al, 2003 | NS | NS | 64 | 40 | - | - | 62.5 | 40.0 | 1 | |

| 47. Wyatt et al, 2004 | NS | NS | 735 | 735 | - | - | 100.0 | 735.0 | 1 |

Developing Recruitment Approaches

We identified factors that may have helped or hindered recruitment from qualitative [57,64,69] and protocol [27,28,30,35] papers. These factors emerged as possible principles of recruitment and were related to training, engaging possible participants in the recruitment process and allowing sufficient time to pilot-test approaches. Watson et al (2009) used trained post-natal health care staff to actively recruit participants during their first home and health centres visits, and at group meetings for new mothers [51]. Recruitment approaches used by Banks-Wallace et al (2004) were based on a 5 month needs assessment study of the concerns and priorities of their target group [27]. The authors reported this process established trust between the research team and participants and ensured active participation in the study and in fact over-recruited from this population. Nguyen et al (2002) reported promoting participation via word of mouth, e.g. one participant tells/recruits another participant [69]. These appeared to have more impact on recruitment than passive approaches like posters or media stories [69]. These data suggest that developing recruitment approaches is a time and resource intensive activity, requiring skilled research and recruitment staff.

Discussion

We conducted a systematic review to examine the reported recruitment procedures of walking studies, in order to identify the characteristics of effective recruitment and the impact and differential effects of recruitment strategies among particular population groups. We identified the need for a common understanding of the recruitment process for walking studies in terms of conceptual definition, defining effectiveness and more detailed reporting. Due to the heterogeneity of studies we were not able to identify what specific recruitment approaches were most successful with particular population groups.

We identified eighteen recruitment strategies from 47 studies but did not see any relationship between one particular strategy or group of strategies and recruitment rates. Many studies blended different recruitment approaches and strategies, adopting an almost "trial and error" approach. Only two studies reported the effectiveness of their approaches to recruitment [28,35]. We were able to distinguish active and passive recruitment approaches. Further research is needed to directly compare specific recruitment strategies.