Abstract

Background

The immune modulatory effect of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) on T cells resulted in an unexpected low incidence of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) in allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation (allo-PBSCT). Recent data indicated that gamma delta+ T cells might participate in mediating graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effect after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. However, whether G-CSF could influence the T cell receptors (TCR) of gamma delta+ T cells (TRGV and TRDV repertoire) remains unclear. To further characterize this feature, we compared the distribution and clonality of TRGV and TRDV repertoire of T cells before and after G-CSF mobilization and investigated the association between the changes of TCR repertoire and GVHD in patients undergoing G-CSF mobilized allo-PBSCT.

Methods

The complementarity-determining region 3 (CDR3) sizes of three TRGV and eight TRDV subfamily genes were analyzed in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from 20 donors before and after G-CSF mobilization, using RT-PCR and genescan technique. To determine the expression levels of TRGV subfamily genes, we performed quantitative analysis of TRGVI~III subfamilies by real-time PCR.

Results

The expression levels of three TRGV subfamilies were significantly decreased after G-CSF mobilization (P = 0.015, 0.009 and 0.006, respectively). The pattern of TRGV subfamily expression levels was TRGVII >TRGV I >TRGV III before mobilization, and changed to TRGV I >TRGV II >TRGV III after G-CSF mobilization. The expression frequencies of TRGV and TRDV subfamilies changed at different levels after G-CSF mobilization. Most TRGV and TRDV subfamilies revealed polyclonality from pre-G-CSF-mobilized and G-CSF-mobilized samples. Oligoclonality was detected in TRGV and TRDV subfamilies in 3 donors before mobilization and in another 4 donors after G-CSF mobilization, distributed in TRGVII, TRDV1, TRDV3 and TRDV6, respectively. Significant positive association was observed between the invariable clonality of TRDV1 gene repertoire after G-CSF mobilization and low incidence of GVHD in recipients (P = 0.015, OR = 0.047).

Conclusions

G-CSF mobilization not only influences the distribution and expression levels of TRGV and TRDV repertoire, but also changes the clonality of gamma delta+ T cells. This alteration of TRGV and TRDV repertoire might play a role in mediating GVHD in G-CSF mobilized allo-PBSCT.

Background

Recently, the peripheral blood stem cells (PBSCs) obtained from granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) mobilized donors has been used more frequently than bone marrow stem cells as the source of stem cells in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT). The clinical advantages of G-CSF-mobilized peripheral blood stem cell transplantation (G-PBSCT) accelerate engraftment and shorten the neutropenic period compared with bone marrow transplantation (BMT)[1,2]. In G-CSF mobilized allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation (allo-PBSCT), despite the presence of a more than 10-fold higher number of mature T cells in the graft, the incidence or severity of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), especially acute GVHD, is not elevated compared with BMT [2,3]. Some studies suggested that the protective effects of G-CSF against GVHD might result from the immune modulatory effect of G-CSF on T cells, including that G-CSF directly modulated via its receptor on T cells or indirectly modulated T cell immune responses via effector cells and cytokines [4-8].

T cells recognize specific ligands by specific T cell receptors (TCR), which are heterodimers comprising either α/β or γ/δ chains. Genes encoding the variable domains of the TCR γ and δ heterodimer chains are TRG (γ chain) and TRD (δ chain), which are assembled by somatic recombination from variable (V), diversity (D, only for TRD), and joining (J) segments [9-11]. The TRG gene contains at least 14 functional variable (TRGV) segments belonging to four subgroups (TRGVI to IV), and the TRD contains at least 8 functional TRDV segments, which are subdivided into 8 TRDV subfamilies (TRDV1 toTRDV8)[12-14]. The functional capacities of γδ+ T cells include cytokine production and potent cytotoxic effector activity [15-17]. Recently, it was reported that γδ+ T cells might participate in regulation of autoimmune diseases and GVHD [16,18-21]. However, it is still unclear whether G-CSF mobilization could influence γδ+ T cells and thereby mediate GVHD. In the present study, to further investigate the immune modulatory effect of G-CSF on T cells, we characterized the distribution and clonality of TRGV and TRDV subfamilies of donor T cells before and after G-CSF mobilization.

Methods

Samples

Peripheral blood was obtained from 20 healthy stem cell donors (9 female, 11 male; median age 30 years, range 14-56 years) before mobilization and on fifth day of mobilization with G-CSF (Filgrastim, subcutaneous injection of 5 μg/kg/d; Kirin Brewery Co, Tokyo, Japan). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from peripheral blood samples by Ficoll-Hypaque gradient centrifugation. The twenty healthy stem cell donors were willing to accept the trial after being informed, and all samples were obtained with consent from them. All the procedures were conducted according to the guidelines of the local ethical review boards before study initiation.

RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis

RNA was extracted from the PBMCs of donors before and after G-CSF mobilization according to the manufacturer's protocol (Trizol, Invitrogen, USA). The quality of RNA was analyzed in 0.8% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. Two μg RNA was reversely transcribed into the first single-stranded cDNA with random hexamer primers, using reverse transcriptase of the Superscript II Kit (Gibco, USA). The quality of cDNA was confirmed by RT-PCR for β2 microglubin (β2M) gene amplification.

RT-PCR for TRGV and TRDV subfamily amplification

As TRGVIV is a pseudogene [16], the analysis of TRGV repertoire was acquired in three TRGV subfamilies in the present study. Three sense TRGV primers and a single TRGC reverse primer, or 8 TRDV sense primers and a single TRDC primer were used in unlabeled PCR for amplification of the TRGV and TRDV subfamilies respectively. Subsequently, a runoff PCR was performed with fluorescent primers labeled at 5'end with the FAM fluorophore (Cγ-FAM or Cδ-FAM). Aliquots of the cDNA (1 μl) were amplified in 20 μl mixture with one of the 3 Vγ primers and a Cγ primer or one of 8 Vδ primers and a Cδ primer. The final mixture contained 0.5 μM sense primer and antisense primer, 0.1 mM dNTP, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 × PCR buffer and 1.25 U Taq polymerase (Promega, USA). The amplification was performed on a DNA thermal cycler (BioMetra, Germany) with 3 min denaturation at 94°C and 40 PCR cycles. Each cycle consisted of 94°C for 1 min, 60°C for 1 min and 72°C for 1 min respectively, and a final 7 min elongation at 72°C. All PCR products were stored at 4°C and ready for genescan analysis [16,22].

Genescan analysis for TRGV and TRDV subfamily clonality

Aliquots of the unlabeled PCR products (2.5 μl) were separately added to a final 10 μl reaction system containing 0.1 μM Cγ-FAM or Cδ-FAM primer, 0.2 mM dNTP, 3 mM MgCl2, PCR buffer and 0.25 U Taq polymerase (Promega, USA). After a 3 min denaturation at 94°C, 35 cycles of amplification were carried out (1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 66°C and 1 min at 72°C and a final 6 min elongation at 72°C). The labeled runoff PCR products (2.5 μl) were heat denatured at 94°C for 4 min with 9.5 μl formamide (Hi-Di Formamide, ABI, USA) and 0.5 μl of Size Standards (GENESCAN™-500-LIZ™ Perkin Elmer, ABI). The samples were then loaded on 3100 POP-4™ gel (Performance Optimized Polymer-4, ABI, USA) and resolved by electrophoresis in 3100 DNA sequencer (ABI, Perkin Elmer) for size and fluorescance intensity analysis using Genescan software [16,22].

Real-time quantitative PCR (RQ-PCR) for TRGV gene

Real-time PCR with SYBR Green I technique was used to examine TRGVI-III subfamily gene expression level in cDNA of PBMCs from 20 peripheral blood samples, the β2-microglobulin gene was used as an internal reference, the folds of change of TRGVI-III gene expression level were used by the 2-ΔCt method. Briefly, PCR in 20 μl total volume was performed with approximately 1 μl cDNA, 0.5 μM of each primer (one of the three Vγ I-III sense primer and the antisense primer Cγ for TRGVI-III amplification, β2M-for and β2M-back primers for β2-microglobulin gene amplification) and 2.5 × RealMasterMix 9 μl (Tiangen, China). After the initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 min, 45 cycles consisting of 95°C 15 s, 60°C 60 s and 82°C 1 s for plate reading were performed using MJ Research DNA Engine Opticon 2 PCR cycler (BIO-RAD, USA). The relative mRNA expression level of TRGVI-III gene in each sample was calculated according to the comparative cycle time (Ct) method. Briefly, the target PCR Ct value, that is, the cycle number at which emitted fluorescence exceeds the 10 × SD of baseline emissions, is normalized by subtracting the β2M Ct value from the target PCR Ct value, which gives the ΔCt value. From this ΔCt value, the relative expression level to β2M for each target PCR can be calculated using the following equation: relative mRNA expression = 2-ΔCt × 100% (ΔCt = Ct(TRGV) - Ct(β2M)) [16,22].

Statistical analysis

Univariate analyses were performed using the Wilcoxon matched pair test to compare medians of TRGV or TRDV subfamilies between pre-G-CSF-mobilized and G-CSF-mobilized groups. McNemar's test was used for comparison of the expression frequencies of TRGV or TRDV subfamilies between two groups. Differences in mRNA expression of TRGVI-III between two groups were analyzed using the Wilcoxon matched pair test. Kruskal-Wallis Test was used for comparison of different gene expression levels from three TRGV subfamilies before or after G-CSF mobilization, and bonferroni correction was used for pairwise comparisons. Binary logistic regression analysis was used to estimate the association between GVHD in recipients and the alteration of each TRGV and TRDV repertoire after G-CSF mobilization. GVHD was considered as the dichotomous dependent variable and the changes of all TRGV and TRDV repertoires after G-CSF mobilization were considered as the covariates. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant (P < 0.0167 was considered as statistically significant in bonferroni correction).

Results

The expression pattern and levels of TRGV repertoire before and after G-CSF mobilization

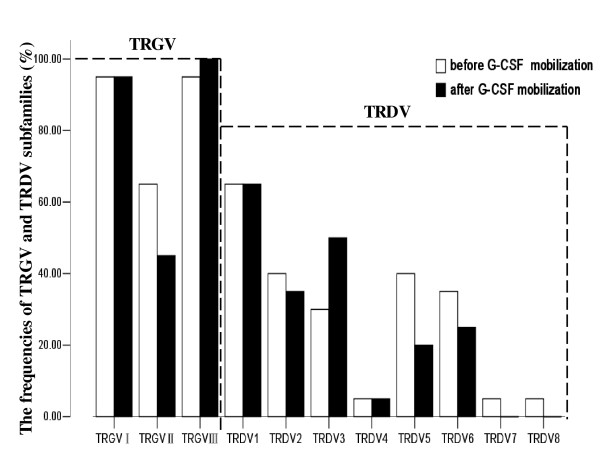

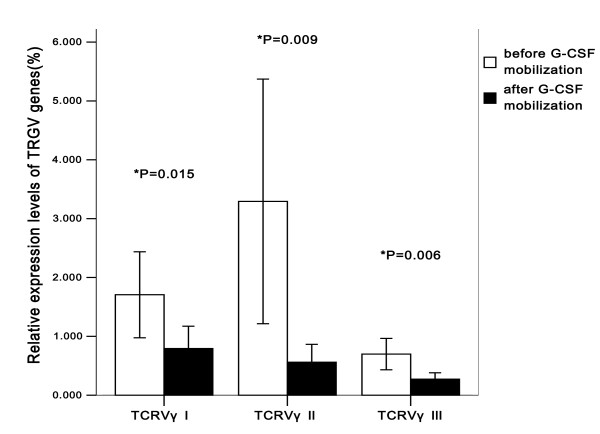

The CDR3 sizes and expression levels of three TRGV subfamily genes in T cells were respectively analyzed by RT-PCR in 20 donors before and after G-CSF mobilization. The results showed that the expression frequencies of TRGVI, TRGVII and TRGVIII before mobilization were 95% (19/20), 65% (13/20) and 95% (19/20), respectively. After G-CSF mobilization, similar expression frequencies were found in TRGVI (95%, 19/20), TRGVII (45%, 9/20) and TRGVIII (100%, 20/20) (P > 0.05) (Figure 1). Although the expression frequency of TRGVII decreased 20% after G-CSF mobilization, McNemar's test showed that there was no significant difference in expression frequency of TRGVII between pre-G-CSF and post-G-CSF group (P = 0.344). In addition, the expression levels of TRGVI, TRGVII and TRGVIII genes after G-CSF mobilization were significantly lower than that before mobilization (P = 0.015, 0.009 and 0.006, respectively), quantified by 2-ΔCt method (Figure 2). The pattern of TRGV expression levels before mobilization revealed as TRGVII >TRGVI >TRGVIII, and there was a significant difference among the expression levels of three TRGV subgroups (χ2 = 8.528, P = 0.014, Kruskal-Wallis test). However, after G-CSF mobilization, it revealed the TRGV I >TRGV II >TRGV III pattern and there was also a significant difference among three TRGV subfamily groups (χ2 = 6.933, P = 0.031, Kruskal-Wallis test) (Figure 2). Bonferroni correction was applied to further compare the difference in each group, there were significant differences between TRGVI and TRGVIII before and after G-CSF mobilization (P = 0.004, 0.007, respectively), but there were no significant difference between TRGVII and TRGVIII (P = 0.031, 0.163, respectively), TRGVI and TRGVII (P = 0.582, 0.301, respectively) before and after G-CSF mobilization.

Figure 1.

The expression frequencies of TRGV and TRDV subfamilies in PBMCs from 20 donors before and after G-CSF mobilization.

Figure 2.

The pattern of TRGV I-III expression levels in PBMCs from 20 donors before and after G-CSF mobilization.

The expression pattern of TRDV repertoire before and after G-CSF mobilization

In TRDV subfamilies, the number of detectable subfamilies ranged from 0 to 6 (median 2.12) before mobilization, which was higher than that after mobilization (ranged from 0 to 4, median 1.94, P > 0.05). The frequently expressed members were TRDV1 (65%, 13/20), TRDV2 and TRDV5 (40%, 8/20), TRDV6 (35%, 7/20) and TRDV3 (30%, 6/20) before G-CSF mobilization, while TRDV1 (65%, 13/20), TRDV3 (50%, 10/20), TRDV2 (35%, 7/20), TRDV6 (25%, 5/20) and TRDV5(20%, 4/20) after G-CSF mobilization. TRDV7 and TRDV8 were detected only in one case before mobilization, and were not identified in all samples after G-CSF mobilization (Figure 1). It could be seen from Figure 1 that the alteration in the expression frequencies between two groups was mainly embodied in TRDV3 (20%, 4/20) and TRDV5 (20%, 4/20), TRDV6 (10%, 2/20). However, there was no significant difference between pre-G-CSF and post-G-CSF expression frequencies of TRDV3, TRDV5 and TRDV6 (P = 0.344, P = 0.219, P = 0.688, respectively).

The clonality of TRGV and TRDV subfamily T cells before and after G-CSF mobilization

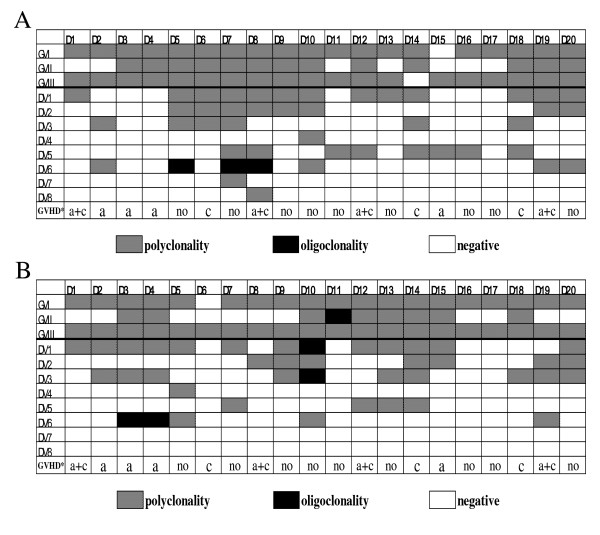

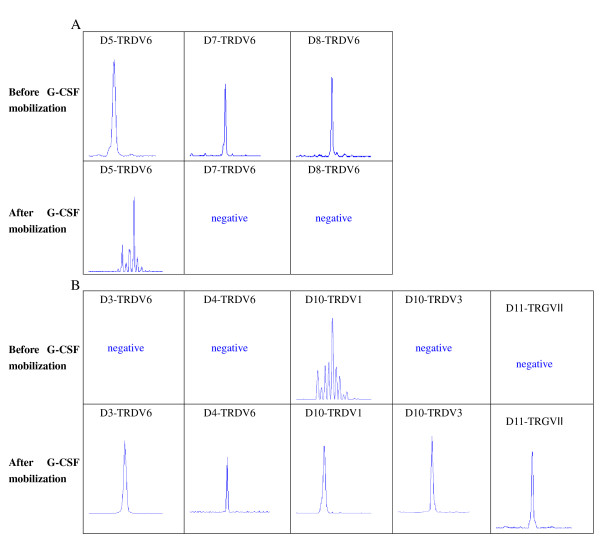

To compare the differences in TRGV and TRDV gene repertoire diversity before and after G-CSF mobilization, three TRGV and eight TRDV gene transcripts and profiles were examined using genescan analysis. Most PCR products of TRGV and TRDV subfamilies displayed a Gaussian distribution of CDR3 lengths (multi-peaks) before and after G-CSF mobilization, which corresponded to polyclonal rearrangement pattern, whereas three PCR products in TRDV6 subfamily from 20 samples displayed oligoclonality before mobilization (Figure 3A). Clonal expansion was identified in another four cases after G-CSF mobilization, distributed in TRGVII, TRDV6, TRDV1 and TRDV3 (Figure 3B). The three oligoclonal expanded TRDV6 T cells which were identified before mobilization underwent alterations after G-CSF mobilization, in which two cases changed to negative and another one changed to polyclonality. Meanwhile, two cases with TRDV6 absence and one case with TRGVII absence before mobilization all changed to oligoclonality after G-CSF mobilization. Moreover, one case without TRDV3 expression changed to oligoclonality, and its polyclonal expansion in TRDV1 changed to oligoclonality after G-CSF mobilization (Figure 4). The alteration of clonality of TRGV and TRDV subfamilies between two groups was mainly reflected in TRGVII (50%, 10/20), TRDV3 (50%, 10/20), TRDV1 (45%, 9/20), TRDV6 (35%, 7/20), TRDV5 (30%, 6/20), and TRDV2 (25%, 5/20) (Figure 3A and 3B).

Figure 3.

Distribution and clonality of TRGV and TRDV subfamilies in PBMCs from 20 donors (D1-D20). (A) before G-CSF mobilization; (B) after G-CSF mobilization. GVHD*: the status of graft-versus-host disease of the corresponding recipients after allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation; a: acute graft-versus-host disease; c: chronic graft-versus-host disease.

Figure 4.

Changes of clonality of TRGV and TRDV subfamilies in PBMCs from 7 donors (D5, D7, D8, D3, D4, D10 and D11) before and after G-CSF mobilization. (A) Oligoclonal expansion changed to polyclonality or negative after mobilization; (B) Polyclonal or negative expansion changed to oligoclonality after mobilization.

Outcome in recipients undergoing allo-PBSCT

From March 2010 to October 2010, 20 patients received G-CSF-mobilized allo-PBSCT from HLA-identical sibling donors. In total, 11 recipients experienced GVHD after transplantation, including 8 recipients with acute GVHD (grade I in 3 and gradeII in 5) and 7 recipients with chronic GVHD (3 extensive and 4 local). Thereinto, 4 cases with chronic GVHD experienced acute GVHD. We analyzed the association between GVHD and the alteration of clonality of each TRGV and TRDV repertoire after G-CSF mobilization. Simple effect analysis of binary logistic regression showed that the invariable clonality of TRDV1 gene repertoire after G-CSF mobilization was associated with low incidence of GVHD (r = 0.616, P = 0.004), and the alteration of other TRDV or TRGV subfamilies had no significant association with GVHD. Multivariate analysis also showed that the invariable clonality of TRDV1 gene repertoire after G-CSF mobilization indicated low incidence of GVHD (P = 0.015, odds ratio (OR) = 0.047, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.004-0.552), and it was no significant association between GVHD and the alteration of expression levels of three TRGV subgroups after G-CSF mobilization (P = 0.806, P = 0.458, P = 0.719, respectively). Meanwhile, it could be seen from Figure 3 that the incidence of GVHD was 8/11 (27.2%) in the TRDV1 clonality invariable group, whereas the incidence of GVHD reached 8/9 (88.9%) in the TRDV1 clonality variable group. In addition, the alteration of expression pattern of TRGV repertoire also was not significantly associated with GVHD (P = 0.120).

Discussion

The immune modulatory effect of G-CSF on T cells resulted in an unexpected low incidence of GVHD in G-CSF mobilized allo-PBSCT. However, the underlying mechanism for the reduced reactivity or alloreactivity of T cells after G-CSF mobilization was not fully understood [23,24]. A growing body of experimental evidence suggests that G-CSF might interact with the immune system by altering T cell reactivity [23,25]. Some studies suggested that G-CSF could directly modulate T-cell immune responses via its receptor, which could be detected on T cells [24,26]. However, whether the unactivated T cells could express G-CSF receptor (G-CSFR) remains unclear. Franzke's study showed that the expression of G-CSFR was undetected in the unactivated T cells, but both CD4+ and CD8+ T cell could express the G-CSFR at the mRNA level after G-CSF stimulation in vivo or vitro [24]. Morikawa et al. also observed that the unactivated T cells from peripheral blood did not bind to the biotinylated G-CSF, but the active T cells after Con A stimulation could bind to the biotinylated G-CSF [26]. These studies suggested that the unactivated T cells could express G-CSFR by stimulation [23,24,26]. However, whether G-CSF directly modulates T-cell immune responses via G-CSFR on T cells or T cell receptor needs further investigation.

T cells are comprised of two major subpopulations, identified by their expression of either the αβ or γδ TCR heterodimer. αβ+ T cells are the predominant circulating population and can be subdivided into cells that express CD4+ or CD8+ antigens. γδ+ T cells, which represent approximately 5-10% of peripheral T cells and are predominantly CD3+ CD4- CD8- T cells [16,27], recognize specific antigen without MHC-restriction and are considered as linkage between innate and adaptive immune response [28,29]. As a group of innate immune cells, γδ+ T cells respond rapidly and expand efficiently when stimulated by antigens or cytokines and may be a good target for modulation of immune responses in human diseases. Recently, the role of γδ+ T cells in mediating GVHD raised certain attention [30-36], but whether γδ+ T cells promoted or inhibited the occurrence of GVHD was still controversial. Several studies showed that γδ+ T cells might contribute to GVHD [32-34], while others demonstrated that γδ+ T cells could inhibit GVHD [35,36]. The generation and maintenance of a diverse T-cell repertoire is a critical element in immune competence. Therefore, it might be interesting to further clarify whether G-CSF could influence the distribution and clonality of TRGV and TRDV repertoire of γδ+ T cells, thereby influencing the alloreactivity of T cells and mediating GVHD in G-CSF mobilized allo-PBSCT.

In the present study, we investigated the feature of distribution and clonality of TRGV and TRDV repertoire from healthy donors before and after G-CSF mobilization. The results showed that G-CSF mobilization could influence the distribution and clonality of TRGV and TRDV repertoire of γδ+ T cells. The expression levels of three TRGV subfamilies were significantly decreased after G-CSF mobilization. In addition, the pattern of TRGV expression levels also changed after G-CSF mobilization, suggesting that G-CSF might influence the expression pattern of TRGV subfamilies. The expression frequencies of TRGV and TRDV subfamilies changed at different levels after G-CSF mobilization; however, there were no significant differences in the expression frequencies of all TRGV and TRDV subfamilies between pre-G-CSF and post-G-CSF group. Most TRGV and TRDV subfamilies revealed polyclonality from pre-G-CSF-mobilized and G-CSF-mobilized samples. Oligoclonality was detected in TRGV and TRDV subfamilies in 3 donors before mobilization and in another 4 donors after G-CSF mobilization, distributed in TRGVII, TRDV1, TRDV3 and TRDV6, respectively. Recent studies suggested that some clonal T cells might be a reaction to host alloantigen and related with GVHD activity [37]. Meanwhile, it is recognized that the persistent oligoclonal T cell expansion could be incurred due to many factors affecting the overall regulation of clone size in response to chronic antigens [16,38]. Our studies revealed that the two oligoclonal expanded TRDV6 T cells appeared in two patients with aGVHD, while the expansion of the TRGVII T cells, as well as the expansion of the TRDV1 and TRDV3 T cells appeared in two patients without GVHD. Consequently, whether the change of clonality was due to the effect of G-CSF or it was related with GVHD needs further study. However, it was a pity that the donors were not followed up, as it took a long time to get the results.

Recently, researchers revealed that γδ+ T cells produced a series of cytokines in pathology and played an indispensable role in pathogen elimination, immune regulation and autoimmunity [39,40]. γδ+ T cells modulated immune responses mainly by secreting cytokines and by regulating the function of other immune cells, such as αβ+ T cells, macrophages, NK cells and CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Treg)and so on [41-44]. Despite the variety of characteristics attributed to γδ+ T cells, their exact role in mediating GVHD remained unclear. Drobyski et al. postulated that transplantation with γδ+ T cells protected mice from GVHD [36], whereas Blazar et al. showed that the infusion of donor γδ+ T cells induced lethal GVHD in mice [34]. However, Anderson et al did not find any correlation between host γδ+ T cells and GVHD in mice [45]. Similarly in human studies, Pabst et.al showed that it was a significant association between an increased donor γδ+ T cells dose and the cumulative incidence estimates of aGVHD [46], whereas Godder et al. observed that patients with increased γδ+ T cells recovery did not have an increased incidence of GVHD compared to those with normal or decreased numbers [20].

Different from most studies which analyzed from angle of quantity of γδ+ T cells, we studied from the perspective of different repertoire of γδ+ T cells (TRGV and TRDV repertoire), which was thought to have different functions for immune response. Positive association was observed between the invariable clonality of TRDV1 gene repertoire after G-CSF mobilization and low incidence of GVHD, and the invariable clonality of TRDV1 gene repertoire after G-CSF mobilization indicated low incidence of GVHD (OR = 0.047). Due to the small sample size, the association between GVHD and other TRDV and TRGV subfamilies needs further study. These results suggested that compared with other TRDV and TRGV repertoire, some donors' TRDV1 repertoire might be more sensitive to GVHD-associated antigens after G-CSF mobilization, causing the occurrence of GVHD; whereas TRDV1 repertoire of most donors maintained stability after G-CSF mobilization, resulting in low incidence of GVHD. Therefore, TRDV1 repertoire might be used as an observation index for GVHD in the future. In short, our studies observed that some repertoire of γδ+ T cells changed after G-CSF mobilization. Accordingly, the antigens recognized by them might change, thereby altering the immune responses of γδ+ T cells and mediating the occurrence of GVHD. However, the mechanisms are still not well understood and need further study.

Conclusions

We characterized the distribution and clonality of TRGV and TRDV subfamilies of donor T cells before and after G-CSF mobilization. The results show that G-CSF mobilization not only influences the distribution and expression levels of TRGV and TRDV repertoire, but also changes the clonality of γδ+ T cells. This alteration of TRGV and TRDV repertoire might play a role in mediating GVHD in G-CSF mobilized allo-PBSCT.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

LX and XLW performed research, analyzed data and wrote the paper; YZ, ZPF and FH analyzed data; YWL, FHZ and XZ performed research; QFL designed research and wrote the paper. The authors reported no potential conflicts of interest. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Li Xuan, Email: 356135708@qq.com.

Xiuli Wu, Email: siulier@163.com.

Yu Zhang, Email: scidzy@gmail.com.

Zhiping Fan, Email: fanzp@fimmu.com.

Yiwen Ling, Email: 924314232@qq.com.

Fen Huang, Email: zhangyihuangfen@yahoo.com.cn.

Fuhua Zhang, Email: zhangfh99@hotmail.com.

Xiao Zhai, Email: 315560270@qq.com.

Qifa Liu, Email: liuqifa628@163.com.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Yangqiu Li of Jinan University for careful guidance of experimental technique and providing relevant primers. The study was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.30971300), Guangdong Natural Science Foundation (No.10451051501005778), Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province of China (No.2009A030200007) and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No.200902332, No.20080440776).

References

- Pan L, Bressler S, Cooke KR, Krenger W, Karandikar M, Ferrara JL. Long-term engraftment, graft-vs.-host disease, and immunologic reconstitution after experimental transplantation of allogeneic peripheral blood cells from G-CSF-treated donors. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 1996;2:126–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderlini P. Effects and safety of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in healthy volunteers. Curr Opin Hematol. 2009;16:35–40. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e328319913c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korbling M, Anderlini P. Peripheral blood stem cell versus bone marrow allotransplantation: does the source of hematopoietic stem cells matter? Blood. 2001;98:2900–2908. doi: 10.1182/blood.V98.10.2900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arpinati M, Green CL, Heimfeld S, Heuser JE, Anasetti C. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor mobilizes T helper 2-inducing dendritic cells. Blood. 2000;95:2484–2490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mielcarek M, Martin PJ, Torok-Storb B. Suppression of alloantigen-induced T-cell proliferation by CD14+ cells derived from granulocyte colony-stimulating factor-mobilized peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Blood. 1997;89:1629–1634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng D, Dejbakhsh-Jones S, Strober S. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor reduces the capacity of blood mononuclear cells to induce graft-versus-host disease: impact on blood progenitor cell transplantation. Blood. 1997;90:453–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mielcarek M, Graf L, Johnson G, B T-S. Production of interleukin-10 by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor-mobilized blood products: a mechanism for monocyte-mediated suppression of T-cell proliferation. Blood. 1998;92:215–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan L, Delmonte J Jr, Jalonen CK, JL F. Pretreatment of donor mice with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor polarizes donor T lymphocytes toward type-2 cytokine production and reduces severity of experimental graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 1995;86:4422–4429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groh V, Porcelli S, Fabbi M, Lanier LL, Picker LJ, Anderson T, Warnke RA, Bhan AK, Strominger JL, Brenner MB. Human lymphocytes bearing T cell receptor gamma/delta are phenotypically diverse and evenly distributed throughout the lymphoid system. J Exp Med. 1989;169:1277–1294. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.4.1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takihara Y, Tkachuk D, Michalopoulos E, Champagne E, Reimann J, Minden M, Mak TW. Sequence and organization of the diversity, joining, and constant region genes of the human T-cell delta-chain locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:6097–6101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.16.6097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster A, Huck S, Ghanem N, Lefranc MP, Rabbitts TH. New subgroups in the human T cell rearranging V gamma gene locus. Embo J. 1987;6:1945–1950. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02456.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefranc MP, Forster A, Rabbitts TH. Genetic polymorphism and exon changes of the constant regions of the human T-cell rearranging gene gamma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:9596–9600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.24.9596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raulet DH, Garman RD, Saito H, Tonegawa S. Developmental regulation of T-cell receptor gene expression. Nature. 1985;314:103–107. doi: 10.1038/314103a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabbitts TH, Lefranc MP, Stinson MA, Sims JE, Schroder J, Steinmetz M, Spurr NL, Solomon E, Goodfellow PN. The chromosomal location of T-cell receptor genes and a T cell rearranging gene: possible correlation with specific translocations in human T cell leukaemia. Embo J. 1985;4:1461–1465. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03803.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabelitz D, Wesch D, Pitters E, Zoller M. Potential of human gammadelta T lymphocytes for immunotherapy of cancer. Int J Cancer. 2004;112:727–732. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Chen S, Yang L, Li B, Chan JY, Cai D. TRGV and TRDV repertoire distribution and clonality of T cells from umbilical cord blood. Transpl Immunol. 2009;20:155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosenko V, Goldenberg DI. [The role of gamma-delta T-lymphocyte subtypes in normal and pathologic conditions] Fiziol Zh. 2001;47:71–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao J, Wu X, Xia S, Li Z, Wen T, Zhao N, Wu Z, Wang P, Zhao L, Yin Z. Current progress in gammadelta T-cell biology. Cell Mol Immunol. 2010;7:409–413. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2010.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujishima N, Hirokawa M, Fujishima M, Yamashita J, Saitoh H, Ichikawa Y, Horiuchi T, Kawabata Y, Sawada KI. Skewed T cell receptor repertoire of Vdelta1(+) gammadelta T lymphocytes after human allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation and the potential role for Epstein-Barr virus-infected B cells in clonal restriction. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;149:70–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03388.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godder KT, Henslee-Downey PJ, Mehta J, Park BS, Chiang KY, Abhyankar S, Lamb LS. Long term disease-free survival in acute leukemia patients recovering with increased gammadelta T cells after partially mismatched related donor bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;39:751–757. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carding SR, Egan PJ. Gammadelta T cells: functional plasticity and heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:336–345. doi: 10.1038/nri797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Chen S, Yang L, Li B, Zhu K, Li Y. The feature of TRGV and TRDV repertoire distribution and clonality in patients with immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Hematology. 2009;14:237–244. doi: 10.1179/102453309X439755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutella S, Zavala F, Danese S, Kared H, Leone G. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor: a novel mediator of T cell tolerance. J Immunol. 2005;175:7085–7091. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzke A, Piao W, Lauber J, Gatzlaff P, Konecke C, Hansen W, Schmitt-Thomsen A, Hertenstein B, Buer J, Ganser A. G-CSF as immune regulator in T cells expressing the G-CSF receptor: implications for transplantation and autoimmune diseases. Blood. 2003;102:734–739. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutella S, Rumi C, Sica S, Leone G. Recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (rHuG-CSF): effects on lymphocyte phenotype and function. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1999;19:989–994. doi: 10.1089/107999099313181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morikawa K, Morikawa S, Nakamura M, Miyawaki T. Characterization of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor receptor expressed on human lymphocytes. Br J Haematol. 2002;118:296–304. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Cramer DE, Ray MB, Chilton PM, Que X, Ildstad ST. The role of alphabeta- and gammadelta-T cells in allogenic donor marrow on engraftment, chimerism, and graft-versus-host disease. Transplantation. 2001;72:1907–1914. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200112270-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita CT, Mariuzza RA, Brenner MB. Antigen recognition by human gamma delta T cells: pattern recognition by the adaptive immune system. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 2000;22:191–217. doi: 10.1007/s002810000042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberl M, Hintz M, Reichenberg A, Kollas AK, Wiesner J, Jomaa H. Microbial isoprenoid biosynthesis and human gammadelta T cell activation. FEBS Lett. 2003;544:4–10. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(03)00483-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda Y, Reddy P, Lowler KP, Liu C, Bishop DK, Ferrara JL. Critical role of host gammadelta T cells in experimental acute graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2005;106:749–755. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-4087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vodanovic-Jankovic S, Drobyski WR. Gammadelta T cells do not require fully functional cytotoxic pathways or the ability to recognize recipient alloantigens to prevent graft rejection. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12:1125–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji S, Char D, Bucy RP, Simonsen M, Chen CH, Cooper MD. Gamma delta T cells are secondary participants in acute graft-versus-host reactions initiated by CD4+ alpha beta T cells. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:420–427. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CA, MacDonald GC, Rector ES, Gartner JG. Gamma delta T cells in the pathobiology of murine acute graft-versus-host disease. Evidence that gamma delta T cells mediate natural killer-like cytotoxicity in the host and that elimination of these cells from donors significantly reduces mortality. J Immunol. 1995;155:4189–4198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazar BR, Taylor PA, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Barrett TA, Bluestone JA, Vallera DA. Lethal murine graft-versus-host disease induced by donor gamma/delta expressing T cells with specificity for host nonclassical major histocompatibility complex class Ib antigens. Blood. 1996;87:827–837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiohara T, Moriya N, Hayakawa J, Itohara S, Ishikawa H. Resistance to cutaneous graft-vs.-host disease is not induced in T cell receptor delta gene-mutant mice. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1483–1489. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drobyski WR, Vodanovic-Jankovic S, Klein J. Adoptively transferred gamma delta T cells indirectly regulate murine graft-versus-host reactivity following donor leukocyte infusion therapy in mice. J Immunol. 2000;165:1634–1640. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.3.1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorochov G, Debre P, Leblond V, Sadat-Sowti B, Sigaux F, Autran B. Oligoclonal expansion of CD8+ CD57+ T cells with restricted T-cell receptor beta chain variability after bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 1994;83:587–595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirokawa M, Horiuchi T, Kawabata Y, Kitabayashi A, Miura AB. Reconstitution of gammadelta T cell repertoire diversity after human allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation and the role of peripheral expansion of mature T cell population in the graft. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2000;26:177–185. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrick DA, Schrenzel MD, Mulvania T, Hsieh B, Ferlin WG, Lepper H. Differential production of interferon-gamma and interleukin-4 in response to Th1- and Th2-stimulating pathogens by gamma delta T cells in vivo. Nature. 1995;373:255–257. doi: 10.1038/373255a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skeen MJ, Ziegler HK. Activation of gamma delta T cells for production of IFN-gamma is mediated by bacteria via macrophage-derived cytokines IL-1 and IL-12. J Immunol. 1995;154:5832–5841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano Y, Kim HT, Matsuoka KI, Bascug G, McDonough S, Ho VT, Cutler C, Koreth J, Alyea EP, Antin JH, Soiffer RJ, Ritz J. Low telomerase activity in CD4+ regulatory T cells in patients with severe chronic GVHD after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2011;118:5021–5030. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-362137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladel CH, Blum C, Kaufmann SH. Control of natural killer cell-mediated innate resistance against the intracellular pathogen Listeria monocytogenes by gamma/delta T lymphocytes. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1744–1749. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.5.1744-1749.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurchenko E, Levings MK, Piccirillo CA. CD4(+) Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells suppress gamma delta T-cell effector functions in a model of T cell-induced mucosal inflammation. Eur J Immunol. 2011. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141814. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nishimura H, Emoto M, Hiromatsu K, Yamamoto S, Matsuura K, Gomi H, Ikeda T, Itohara S, Yoshikai Y. The role of gamma delta T cells in priming macrophages to produce tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:1465–1468. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson BE, McNiff JM, Matte C, Athanasiadis I, Shlomchik WD, Shlomchik MJ. Recipient CD4+ T cells that survive irradiation regulate chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2004;104:1565–1573. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pabst C, Schirutschke H, Ehninger G, Bornhauser M, Platzbecker U. The graft content of donor T cells expressing gamma delta TCR+ and CD4+foxp3+ predicts the risk of acute graft versus host disease after transplantation of allogeneic peripheral blood stem cells from unrelated donors. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2916–2922. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]