Abstract

Background

We evaluated the in vitro activity of a merochlorin A, a novel compound with a unique carbon skeleton, against a spectrum of clinically relevant bacterial pathogens and against previously characterized clinical and laboratory Staphylococcus aureus isolates with resistance to numerous antibiotics.

Methods

Merochlorin A was isolated and purified from a marine-derived actinomycete strain CNH189. Susceptibility testing for merochlorin A was performed against previously characterized human pathogens using broth microdilution and agar dilution methods. Cytotoxicity was assayed in tissue culture assays at 24 and 72 hours against human HeLa and mouse sarcoma L929 cell lines.

Results

The structure of as new antibiotic, merochlorin A, was assigned by comprehensive spectroscopic analysis. Merochlorin A demonstrated in vitro activity against Gram-positive bacteria, including Clostridium dificile, but not against Gram negative bacteria. In S. aureus, susceptibility was not affected by ribosomal mutations conferring linezolid resistance, mutations in dlt or mprF conferring resistance to daptomycin, accessory gene regulator knockout mutations, or the development of the vancomycin-intermediate resistant phenotype. Merochlorin A demonstrated rapid bactericidal activity against MRSA. Activity was lost in the presence of 20% serum.

Conclusions

The unique meroterpenoid, merochlorin A demonstrated excellent in vitro activity against S. aureus and C. dificile and did not show cross-resistance to contemporary antibiotics against Gram positive organisms. The activity was, however, markedly reduced in 20% human serum. Future directions for this compound may include evaluation for topical use, coating biomedical devices, or the pursuit of chemically modified derivatives of this compound that retain activity in the presence of serum.

Introduction

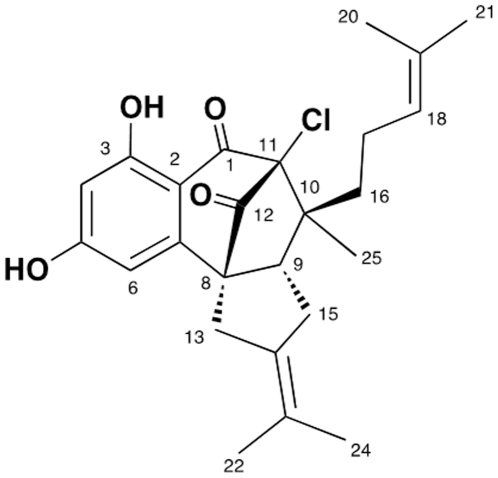

The constant evolution of bacterial pathogens with resistance to clinically available antimicrobial agents drives a continuous demand for the development of novel antimicrobial agents. In the United States, Staphylococcus aureus is the leading cause of hospital-associated and community-associated bacterial infections involving the bloodstream, skin and soft tissue and other sites, with a the majority of these pathogens being methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) [1], [2]. MRSA is endemic in most hospitals, and invasive MRSA infections have been associated with higher mortality rates than comparable infections caused by methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA), even when adjusting for host factors, with mortality estimates of about 20% for bacteremia [3]. Currently, the burden of MRSA infections in the United States is enormous, with almost 100,000 annual cases of invasive infections translating to almost 20,000 deaths, representing a leading cause of infection-related mortality by a single pathogen [4]. In addition, S. aureus has historically demonstrated a propensity to develop resistance to antibiotics quite rapidly after they are introduced clinically, frequently within 1–2 years [5]. In this setting, the development of novel antimicrobial agents against MRSA continues to be in great demand. We have examined the in vitro properties of a novel meroterpenoid, merochlorin A (Figure 1), against MSSA and MRSA with a wide range of resistance determinants against most currently available anti-staphylococcal antibiotics.

Figure 1. Chemical structure of merochlorin A.

Methods

Cultivation and extraction

The actinobacterium (strain CNH-189) was isolated from a near-shore marine sediment collected off Oceanside, California. It was identified as a new Streptomyces sp. based on 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis (accession number HQ214120). The strain was cultured in sixty 2.8 L Fernbach flasks each containing 1 L of A1 production medium (10 g starch, 4 g yeast extract, 2 g peptone, 1 g CaCO3, 40 mg Fe2(SO4)3•4H2O, 100 mg KBr) and shaken at 230 rpm at 27°C. After seven days of cultivation, sterilized XAD-16 resin (20 g/L) was added to adsorb the organic products, and the culture and resin were shaken at 215 rpm for 2 hours. The resin was filtered through cheesecloth, washed with deionized water, and eluted with acetone. The acetone was removed under reduced pressure, and the resulting aqueous layer was extracted with EtOAc (3×500 mL). The EtOAc-soluble fraction was dried in vacuo to yield 4.5 g of crude extract. Note that no specific permits were required for the collection of ocean floor sediment. The location of sediment collection was not privately-owned or protected territories and there was no impingement on endangered or protected species.

Purification and Structure Assignment of Merochlorin A

The crude extract was purified by open column chromatography on silica gel (25 g), eluted with a step gradient of dichloromethane and methanol. The dichloromethane/methanol 100∶1 fraction contained a mixture of metabolites, which were purified by reversed-phase HPLC (Phenomenex Luna C-18 (2), 250×100 mm, 2.0 mL/min, 5 mm, 100 Å, UV = 210 nm) using an isocratic solvent system from 85% CH3CN to afford merochlorin A. The structure of merochlorin A was assigned by comprehensive spectroscopic analysis involving interpretation of HRMS data (assignment of molecular formula), infrared and UV spectroscopy (functional groups and chromophore analyses), and by comprehensive 1D and 2D NMR studies at 500 MHz.

Bacterial strains and in vitro susceptibility testing

Bacterial strains used in this study are described in Tables 1 and 2 [6]–[15]. Many of these strains have been previously well-characterized in cited references in these tables. Susceptibility testing was performed in duplicate using Mueller-Hinton broth (MHB) and Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA) according to CLSI methods. Susceptibility of merochlorin A and vancomycin against MRSA ATCC33591 was also determined in the presence of 20% activated-pooled human serum (obtained from a pool from healthy donor serum) and 80% MHB. Using 96-well tissue culture treated plates (MICROTEST™ 96, Becton-Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ), MICs in the presence and absence of serum were determined through the broth microdilution method. It was noted that in the presence of serum, the endpoints were difficult to read visually or via a spectrophotometer. Thus, the color-change indicator, resazurin (Sigma-Adrich, St. Louis, MO), was used as an endpoint signal for cell growth as previously shown [16], [17]. Resazurin sodium salt powder was solubilized in sterile water to a final concentration of 270 mg/40 mL, filtered using a Costar #8160 Spin-X® Centrifuge Tube Filter by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 10 min, and added to each well of the test plate in a final concentration of 10%. After incubation for 2 hours at 37°C, the plates were visually evaluated for color change from the blue indicator to the pink resorufin, a sign of bacterial growth.

Table 1. In vitro susceptibility against representative strains of clinically relevant bacterial pathogens for merochlorin A.

| Susceptibility Test MIC (mg/L) | ||

| Broth Microdilution | Agar Dilution | |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae (D39) | 2 | ND |

| Streptococcus pyogenes (5448, NZ131) | 4 | ND |

| Streptococcus agalactiae (COH1) | 4 | ND |

| Bacillus cereus | 2 | ND |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis (ATCC12228) | 4 | ND |

| MRSA (ATCC33591) | 2 | 1 |

| MSSA (ATCC29213) | 4 | 2 |

| Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium | 2 | 1 |

| Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis | 1 | 1 |

| Clostridium dificile ATCC 700057 | 0.3 | ND |

| Clostridium dificile (BI) | 0.15 | ND |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | >64 | >64 |

| Escherichia coli ATCC25922 | >64 | >64 |

| Enterobacter cloacae | >64 | >64 |

| Acinetobacter baumanii | >64 | >64 |

| Klebsiella pnemoniae | >64 | >64 |

Table 2. In vitro susceptibility of merochlorin A against multi-drugresistant S. aureus strains, including those resistant to contemporary antibiotics.

| Strain Number | Species | Description | merochlorin A MIC (mg/L) |

| SA7817 | MRSA | Progenitor to 7819 [6] | 2 |

| SA7819 | MRSA | Linezolid resistant, G2756T [6] | 2 |

| 7819erm | MRSA | ermC-transformed 7819 [7] | 2 |

| SA354 | MRSA | Bloodstream. Progenitor to 355 [8] | 2 |

| SA355 | MRSA | Linezolid resistant A2500T [8] | 2 |

| SA853 | MRSA | Progenitor of 853b, VAN MIC 1 mg/L (this study) | 2 |

| SA853b | VISA | In vitro selected VISA, VAN MIC 8 mg/L (this study) | 2 |

| A5937 | MRSA | Bloodstream Endocarditis, mecA+, VAN MIC 2 mg/L [9] | 2 |

| A5940 | VISA | Selected in vivo VISA, mecA+, VAN MIC 4 mg/L [9] | 2 |

| SA6300 | MRSA | VAN MIC 2 mg/L, progenitor to SA6298 [9] | 2 |

| SA6298 | VISA | VAN MIC 4 mg/L, selected in vivo [9] | 2 |

| SA0616 | MSSA | Endocarditis, SA701 Progenitor, DAP MIC 0.25 mg/L [10], [11] | 2 |

| SA0701 | MSSA | DAP MIC 2 mg/L [10], [11] | 2 |

| RN6607 | MSSA | SA502A, tetM, agr group II prototype [12] | 4 |

| RN9120 | MSSA | agr knockout of RN9120 [12] | 4 |

| RN9120b | MSSA | VISA selected in vivo from RN9120, VAN MIC 4 mg/L [12] | 4 |

| HIP5836 | VISA | New Jersey VISA [13] | 2 |

| VRSA MI | VRSA | vanA vancomycin-resistant S. aureus [14] | 2 |

| VRSA PA | VRSA | vanA vancomycin-resistant S. aureus [15] | 2 |

Note: Isolates are grouped together above in cases where they have been isolated from the same patient and/or are the results of manipulations in the laboratory of an original strain and have been confirmed identical to each other by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE).

Kill curve assays

Overnight cultures of test strains in MHB were diluted 1∶1000 in fresh broth (inoculum approximately 5×105 cfu/ml) containing merochlorin A at 4× MIC (8–16 mg/L) and incubated with shaking at 200 RPM at 37°C. Samples at time 0, 4, and 24 hours were serially diluted 100–106, and 10 microliters were plated on TSA plates. Colonies were counted after 20 hours at 37°C to calculate surviving cfu/mL.

Post-antibiotic effect (PAE)

An inoculum of approximately 107 cfu/mL of MRSA ATCC33591 was incubated for 1 hour in MHB containing merochlorin A 2 mg/L (1× MIC) at 37°C with shaking at 200 RPM in a 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube. The bacteria were pelleted by microcentrifugation, washed twice in PBS, and resuspended in an equal volume of fresh antibiotic-free MHB. Samples were obtained at various time points, serially-diluted, and 10 microliters were plated on TSA plates. Colonies were counted at 20 hours to calculate cfu/ml over time. The PAE was calculated according to the Craig and Gudmundsson formula: PAE = T – C. In this formula, T refers to the time it takes the treated culture to recover by one-log10 CFU greater then immediately observed after drug removal (time 0), and C refers to the corresponding recovery time observed for the untreated control [18].

Population analysis

An inoculum of approximately 5×107 cfu/mL of MRSA ATCC33591 was prepared in fresh MHB by transferring several colonies of overnight growth on MHA plates using sterile applicators. Ten microliters of serial 10-fold dilutions (100–107) were plated in triplicate on MHA plates containing 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, and 16 mg/L of merochlorin A. Colonies were counted at 20 hours, and surviving bacteria were enumerated for each concentration.

Cytotoxicity assays

Cytotoxcity was assessed by incubation of HeLa and L929 (American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), Manassas, VA) mammalian cell lines (2×104 cells per well) in sterile 96 well tissue culture-treated plates in the presence of decreasing concentrations of merochlorin A and incubation at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 24 h. Cytotoxicity was assayed by MTS (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2Htetrazolium) using the CellTiter 96® Aqueous non-radioactive cell proliferation assay according to manufacturer's instructions (Promega Madison, WI). This assay measures the reducing potential of viable cells using a colorimetric reaction, which is quantitated spectrophotometrically at 490 nm. Cytotoxicity was defined as the concentration which showed a >50% reduction in absorbance at 490 nm compared to the merochlorin A-free negative control. Etoposide at 10 mg/L was used as the positive cytotoxicity control.

Results

Isolation and structure assignment of merochlorin A

The crude extract (4.5 g) was fractionated by open column chromatography on silica gel (25 g), eluted with a step gradient of dichloromethane and methanol. The dichloromethane/methanol 100∶1 fraction contained a mixture of metabolites, which were purified by reversed-phase HPLC (Phenomenex Luna C-18 (2), 250×100 mm, 2.0 mL/min, 5 mm, 100 Å, UV = 210 nm) using an isocratic solvent system from 85% CH3CN to afford merochlorin A (1, 12.0 mg), as a pale yellow oil. The molecular formula for merochlorin A was deduced as C25H29 35ClO4, based on analysis of HRESIMS data (a pseudomolecular ion peak at m/z 429.1821 [M+H]+) and on interpretation of 13C NMR data. Merochlorin A showed strong UV absorptions at 240, 296, and 330 nm, indicating a conjugated aromatic or phenolic functional group. The IR spectrum showed broad absorptions for multiple hydroxyl groups (3380 cm−1) and characteristic carbonyl groups (1704 cm−1). The 1H NMR spectrum of merochlorin A displayed a pair of meta-coupled aromatic protons [H-4 (δH 6.16), H-6 (δH 6.38)], one olefin proton H-18 (δH 4.92), five methyl singlets H-21 [(δH 1.53), H-20 (δH 1.45), H-24 (δH 1.65), H-22 (δH 1.56), H-25 (δH 0.81)], and an exchangeable proton 3-OH (δH 11.9). The 13C NMR and HSQC spectroscopic data revealed two carbonyl, ten quaternary, four methine, four methyene, and five methyl carbons.

Interpretation of data from 2D NMR experiments allowed three fragments, a 1,2,3,5 tetrasubstituted benzene moiety, the C-10 side chain of the molecule, and a propan-2-ylidenecyclopentane moiety, to be assembled. The first fragment was established from analysis of a 1H-1H coupling constant and 2D NMR spectral data. The meta-coupling of two aromatic protons [H-4 (δH 6.16, d, J = 2.0 Hz), H-6 (δH 6.38, d, J = 2.0 Hz)] indicated a 1,2,3,5 tetrasubstituted benzene moiety. A long range HMBC correlation of the aromatic proton H-4 to carbons C-3 (δC 165.4) and C-5 (δC 166.5) and their carbon chemical shifts suggested the substitution of the two hydroxyl groups at C-3 and C-5, respectively. The presence of two hydroxyl groups was confirmed by the methylation of 5-OH followed by the acetylation of 3-OH. A chelated hydroxyl proton (δH 11.59, 3-OH) strongly suggested the presence of a carbonyl group at C-1, which revealed the ketone group based on the carbon chemical shift of C-1 (dC 193.2). The second fragment, the C-10 side chain of the molecule, was established from COSY crosspeaks and HMBC correlations (Figure 1b). The COSY crosspeaks from the protons H-16 through H-18 [H-16 (δH 1.40, 1.14)- H-17 (δH 2.03, 1.75)- H-18 (δH 4.92)], and the long-range HMBC correlations from an olefinic proton H-18 to carbons C-19 (δC 131.6), C-20 (δC 18.1), C-21 (δC 26.1) permitted the assignment of the side chain of the fragment (C-16 to C-21). The last fragment, a propan-2-ylidenecyclopentane moiety, was assigned by analysis of COSY and HMBC spectroscopic data. The COSY crosspeaks between H-9 and H-15, and long-range HMBC correlations from H-15 to C-8, C-9, C-13, C-14, and C-23: from two dimethyl singlet H-22 to carbons C-14 and C-23: from H-24 to carbons C-14 and C-23 allowed the construction of the propan-2-ylidenecyclopentane moiety.

The three fragments were connected by analysis of HMBC spectroscopic data. The observation of the three bond HMBC correlations from H-6 to C-2, C-4, and C-8 along with two bond HMBC correlations from H-6 to C-5 and C-7 permitted the connection of C-7 to C-8. The connection of C-16 to C-10, of C-10 to C-11, and of C-10 to C-9 was established by the long-range HMBC correlations from H-16 to C-9, C-10, C-11, from H-15 to C-9 and C-10, and from a singlet methyl H-25 to C-9, C-10, C-11, and C-16. The connection of C-12 with C-8 was determined by long-range HMBC correlations from H-13 to C-8 and C-12 and from H-9 to C-8 and C-12. Establishing the connectivity of the remaining part of the molecule was difficult due to the absence of any protons correlating with carbons C-1, C-11, and C-12. Thus, we considered carefully the chemical shifts of C-1 (δC 193.2), C-12 (δC 200.1) and C-11 (δC 91.1): these data led us to place the remaining chlorine atom at C-11 and to connect C-1 to C-11 and C-11 to C-12, thus completing the structure assignment of merochlorin A.

In vitro susceptibility testing using both broth and agar-based CLSI methods against single strain representatives of clinically-relevant Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria revealed activity of compound merochlorin A against MSSA, MRSA, and VRE but no activity against Gram-negatives (Table 1). For bacteria for which activity was present, agar dilution consistently gave a single dilution lower MIC than broth microdilution (Table 1). Of particular interest was the high potency against Clostridium dificile representative strains, including the contemporary virulent BI strain (also known as the NAP1 or ribotype 027 strain).

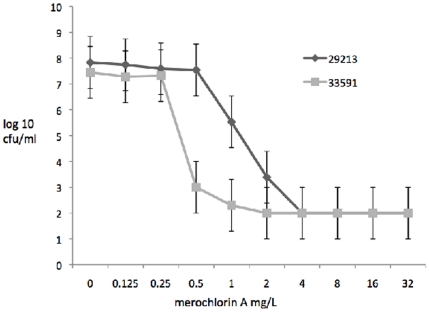

Susceptibility testing using various MRSA and MSSA with resistance to contemporary antibiotics revealed no significant change in MIC to merochlorin A with the acquisition of resistance to vancomycin (both intermediate-level VISA and high–level vanA-mediated VRSA), linezolid, or daptomycin (Table 2). The MIC of all S. aureus strains tested against merochlorin A was 2–4 mg/L. Population analysis of ATCC 29213 (MSSA) and ATCC 33591 (MRSA) showed a slightly heterogeneous type of susceptibility for the MSSA and a homogeneous susceptibility for MRSA (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Merochlorin A population analysis of ATCC 29213 (MSSA) and ATCC 33591 (MRSA).

Significantly higher viable bacteria at 0.5 and 1 mg/L for MSSA compared to MRSA (p<0.01).

Examination of an accessory gene regulator (agr) knockout of MSSA RN9120, derived from strain RN6390b (SA502A) (Table 2) which has previously demonstrated a proclivity towards development of vancomycin intermediate resistant phenotype also did not show a change in merochlorin A MIC. Agar dilution susceptibility testing showed one dilution lower MIC than broth-based methods (data not shown).

Cytotoxicity, defined as a 50% reduction in absorbance at 490 nm measuring the reduced MTS reagent, was noted at 64 mg/L and 2 mg/L in HeLa cells at 24 and 72 hours, respectively, and at 32 mg/L and 4 mg/L in L929 cells at 24 and 72 hours, respectively.

However, merochlorion A susceptibility testing in MHB containing 10% and 20% human serum resulted in complete inactivation of in vitro activity (MIC>64 mg/L) for all strains tested. The post antibiotic effect against MRSA ATCC33591 was determined to be 8 and 9 hours at 2 mg/L (1× MIC) in 2 separate experiments.

Killing assays were performed in Mueller-Hinton broth against linezolid-resistant MRSA and 2 VISA (one mecA+ and one mecA−). For the VISA strains, fully vancomycin-susceptible progenitor parent strains were compared in parallel. For all strains tested, merochlorin A exhibited potent bactericidal activity, achieving the limit of detection at 24 hours (approximately 104 cfu/mL reduction). For both pairs tested, the VISA isolate showed increased killing at 4 hours compared to the vancomycin susceptible parent strain (data not shown).

Discussion

We report a novel natural product, merochlorin A, with in vitro activity against multi-drug resistant Gram-positive organisms, including C. dificile and MRSA. Merochlorin A (Figure 1) possesses a new carbon skeleton unrelated to any antibacterial agents reported to date. This is particularly noteworthy given the paucity of novel antibiotic classes currently in development for clinical use. Resistance to commonly-used MRSA agents, including vancomycin (both intermediate and high-level vanA-mediated), linezolid, and daptomycin did not affect in vitro susceptibility. We evaluated resistant isolates to contemporary anti-staphylococcal antibiotics because future agents must be able to counter resistance to these drugs, which is to be expected in the years ahead with increased utilization. While resistance to linezolid and daptomycin is rare among clinical isolates, we anticipate higher resistance rates in the future. Furthermore, reduced susceptibility across classes that has been determined between the lipopeptide daptomycin and intermediate-level glycopeptides resistance in S. aureus, as well as reduced susceptibility to telavancin mediated by vanA, further heighten concern about the future of antimicrobial resistance in S. aureus. This lack of cross-resistance of merochlorin A to contemporary antibiotics with specific mechanisms of action is consistent with our preliminary mechanism of action studies suggesting global inhibition of DNA, RNA, protein, and cell wall synthesis.

Merochlorin A showed bactericidal activity and had an 8–9 hour post antibiotic effect. Cytotoxicity was favorable in the 24 hour assay but was increased to concentrations close to its antimicrobial range in the 72 hour assay. Population analyses of a representative MRSA and MSSA showed a more heterogeneous susceptibility profile for MSSA and a homogeneous profile for MRSA.

In light of inhibition by serum, several avenues exist for merochlorin A. First would be chemical modification of the compound in order to eliminate serum inactivation while preserving in vitro activity against MRSA. Our laboratories have started to develop derivatives based on merochlorin A structure that are not inhibited by serum and achieve compounds better suited for systemic use. Other strategies may include development and formulation as an enterally administered agent against C. dificile, topical S. aureus decolonization, or the topical therapy of wound infections, particularly in the setting of rising resistance to mupirocin in S. aureus [19]. Note that prolonged treatment of infected devitalized wounds with systemic vancomycin was a feature of some cases in which patients became colonized with vancomycin-resistant S. aureus [14], [15]. Considerations can also be made for using this compound to coat biomedical devices such as central venous catheters that are at risk for becoming colonized and subsequently infected with resistant Gram-positive pathogens such as MRSA and S. epidermidis.

In summary, we present merochlorinA, a novel meroterpenoid compound which may provide a foundation for developing viable antimicrobial compounds against MRSA and Clostridium dificile that are unaffected by resistance to currently utilized antimicrobial classes.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Diane M. Cintron of R.M. Alden Research Laboratories (Culver City, CA) for performing susceptibility testing against Clostridium dificile and to Karen Shaw of Trius Therapeutics (San Diego, CA) for performing the Metlab analysis.

No specific permits were required for the collection of ocean floor sediment. The location of sediment collection was not privately-owned or protected territories and there was no impingement on endangered or protected species.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: This study was funded by National Institutes of Health Grant RO1-GM08555. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Jarvis WR, Schlosser J, Chinn RY, Tweeten S, Jackson M. National prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in inpatients at US health care facilities, 2006. Am J Infect Control. 2007;35:631–637. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klein E, Smith DL, Laxminarayan R. Hospitalizations and deaths caused by methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus, United States, 1999–2005. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1840–1846. doi: 10.3201/eid1312.070629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cosgrove S, Sakoulas G, Perencevich EN, Schwaber MJ, Karchmer AW, et al. Mortality related to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus compared to methicillin-susceptible S. aureus: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:53–59. doi: 10.1086/345476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klevens RM, Morrison MA, Nadle J, Petit S, Gershman K, et al. Invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in the United States. JAMA. 2007;298:1763–1771. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.15.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakoulas G, Moellering RC. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): increasing antibiotic resistance. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(Suppl 5):S360–S367. doi: 10.1086/533592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsiodras S, Gold HS, Sakoulas G, Eliopoulos GM, Wennersten C, et al. Linezolid resistance in a clinical isolate of Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet. 2001;358:207–208. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05410-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sakoulas G, Gold HS, Moellering RC, Ferraro MJ, Eliopoulos GM. Introduction of ermC into a clinical linezolid- and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus does not restore linezolid susceptibility. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;51:1039–1041. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meka VG, Pillai SK, Sakoulas G, Wennersten C, Venkataraman L, et al. Linezolid resistance in sequential Staphylococcus aureus blood culture isolates associated with a T2500A mutation in the 23S rRNA gene and loss of a single copy of this gene. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:311–317. doi: 10.1086/421471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sakoulas G, Eliopoulos GM, Moellering RC, Wennersten C, Venkataraman L, et al. Characterization of the accessory gene regulator (agr) locus in geographically diverse Staphylococcus aureus with reduced susceptibility in vancomycin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:1492–1502. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.5.1492-1502.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakoulas G, Rose W, Rybak MJ, Pillai S, Alder J, et al. Evaluation of methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis developing nonsusceptibility to daptomycin. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:220–224. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00660-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang SJ, Kreiswith BN, Sakoulas G, Yeaman MR, Xiong YQ, et al. Enhanced expression of dltABCD is associated with the development of daptomycin nonsusceptibility in a clinical endocarditis isolate of Staphylococcus aureus. J Infect Dis. 2009;200:1916–1920. doi: 10.1086/648473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sakoulas G, Eliopoulos GM, Moellering RC, Novick RP, Venkataraman L, et al. Accessory gene regulator (agr) group II Staphylococcus aureus: is there a relationship to the development of intermediate-level glycopeptide resistance? J Infect Dis. 2003;187:929–938. doi: 10.1086/368128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: Staphylococcus aureus with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin—United States, 1997. Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 1997;46:813–815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Public Health Dispatch: Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus-Pennsylvania. Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 2002;51:902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Staphylococcus aureus resistant to vancomcyin-United States, 2002. Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 2002;51:565–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarkera SD, Naharb L, Kumarasamyc Y. Microtitre plate-based antibacterial assay incorporating resazurin as an indicator of cell growth, and its application in the in vitro antibacterial screening of phytochemicals. Methods. 2007;42:321–324. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zurenko GE, Yagi BH, Schaadt RD, Allison JW, Kilburn KO, Glickman SE, et al. In vitro activities of U-100592 and U-100766, novel oxazolidinone antibacterial agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:839–45. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.4.839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Craig WA, Gudmundsson S. Postantibiotic effect. In: Lorian V, editor. Antibiotics in laboratory medicine, 4th ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins; 1996. pp. 296–329. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coates T, Bax R, Coates A. Nasal decolonization of Staphylococcus aureus with mupirocin: strengths, weaknesses, and future prospects. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;64:9–15. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]