Abstract

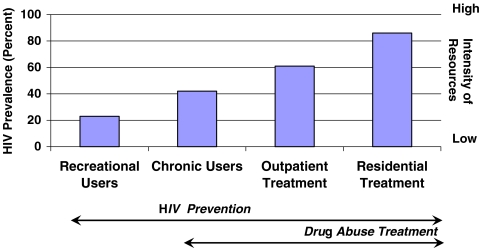

Among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Los Angeles County, methamphetamine use is associated with high rates of HIV prevalence and sexual risk behaviors. In four separate samples of MSM who differed in the range of their intensity of methamphetamine use, from levels of recreational use to chronic use to those for MSM seeking drug abuse treatment, the association between methamphetamine use and HIV infection increased as the intensity of use increased. The lowest HIV prevalence rate (23%) was observed among MSM contacted through street outreach who mentioned recent methamphetamine use, followed by MSM who used at least once a month for six months (42%), followed by MSM seeking intensive outpatient treatment (61%). The highest rate (86%) was observed among MSM seeking residential treatment for methamphetamine dependence. The interleaving nature of these epidemics calls for comprehensive strategies that address methamphetamine use and concomitant sexual behaviors that increase risk of HIV transmission in this group already at high risk. These and other data suggest that MSM who infrequently use methamphetamine may respond to lower intensity/lower cost prevention and early intervention programs while those who use the drug at dependence levels may benefit from high intensity treatment to achieve goals of reduced drug use and HIV-risk sexual behaviors.

Keywords: Methamphetamine, HIV, MSM.

Methamphetamine Abuse as a Public Health Problem

Methamphetamine is the prominent drug of choice for men who have sex with men living in the West Coast metropolitan areas of the United States. In a probability-based survey of gay men, 11% of those in Los Angeles and 13% in San Francisco acknowledged methamphetamine use in the previous six months.1 In a probability sample of MSM aged 15–22 conducted between 1994 and 1998 in seven U.S. cities, high rates of methamphetamine use in the previous 6 months (20.1% of the total sample) were also reported with prevalence being highest for Los Angeles (32.0%), San Francisco, (28.5%), and Seattle (28.2%).2 Among MSM who use methamphetamine, as with other populations of drug users, levels of use vary both by the frequency and the amount of drug used, with degrees of use that range from occasional (or “recreational”) through chronic, heavy use (abuse and dependence).

Studies have shown that methamphetamine-using MSM have an increased likelihood of being HIV-infected or having a sexually transmitted infection,1,4–10 an increased likelihood of having hepatitis A, B, or C,11,12 and reduced rates of adherence with HIV medications.13 Methamphetamine abuse compromises income earning and leads to increased criminality and incarceration in men.14 Additionally, methamphetamine abuse is linked to psychological consequences that include psychosis, depression, suicidal ideation, violence, family and social disruptions, and criminal activity.3

Among MSM who abuse methamphetamine, a serious public health problem emerged and has escalated in every dimension: high prevalence of HIV infection. The problem of methamphetamine-related HIV infection has many facets, including potential for contributing to development and transmission of HIV strains that are resistant to the current armamentarium,15 impairment of immune functioning,16 and potential for high rates of unsafe sexual behaviors,17 thereby worsening the HIV epidemic and potentially complicating treatment of HIV.15 Yet to be determined is the extent to which methamphetamine has direct effects on immune functioning that may facilitate HIV transmission, the extent to which behavioral effects of methamphetamine may interfere with HIV medication adherence, and the extent to which these factors may combine to interact with the rate of HIV disease progression.

A Time-to-Event Association

Data collected from four projects over the past decade in Los Angeles County indicate that among MSM, as the level of intensity of methamphetamine use increases, HIV prevalence rates also are seen to increase (see Figure 1). This characteristic, which resembles a “time-to-event” association, likely reflects the accumulated impact of repeated episodes of drug-associated HIV-sexual risk behaviors and distinguishes methamphetamine from other drugs of abuse among gay men. Data reported here were compiled from four projects that provided services and/or conducted research with methamphetamine-using MSM within a 7-mile radius that includes the Hollywood and West Hollywood areas, which are the areas with the highest concentration of HIV cases in Los Angeles County.18

Figure 1.

Studies include purposeful samples (outreach and clinic-based). HIV prevalence is lower in samples of MSM seeking prevention or non-intervention projects, with very high prevalence observed in the treatment samples. This apparent “time-to-response” association has implications for guiding interventions, with lower-intensity prevention likely sufficient to help recreational and chronic users reach drug and sexual risk-behavior goals and high-intensity treatments likely necessary for MSM with dependence to reach drug and sexual risk-behavior goals.

Reports from HIV prevention street outreach activities conducted over a two-year period indicate that 23% of MSM who report at least one episode of methamphetamine use in the previous 30 days also report HIV infection.19 Outreach activities were conducted in areas where MSM were known to congregate such as bars, bathhouses, sex clubs, cruising areas, and particular street corners. In a smaller qualitative study,20 a higher percentage of HIV infection (42%) was observed in MSM who were not interested in drug abuse treatment and who used methamphetamine at least once per month for the previous six months and at least once in the 30 days prior to the interview. In a report on 162 MSM who use methamphetamine at levels that are consistent with DSM-IV diagnoses of dependence and who appeared for outpatient drug abuse treatment, 61% report HIV-infection.9 Finally, among MSM who report methamphetamine dependence and who requested a 90-day residential treatment program due to severe dependence-related problems, fully 86% were HIV infected.21

Findings from these four convenience samples consistently show that as methamphetamine-using participants select programs of increasing intensity (from prevention services to residential treatment), the more problematic levels of methamphetamine use are concomitant with higher prevalence of HIV.

While the apparent correspondence between higher levels of methamphetamine use and higher HIV prevalence among MSM in Los Angeles County does not establish a causal connection between these factors, it does indicate the role of methamphetamine use in concomitant behaviors that increase risk of HIV transmission, particularly unprotected anal intercourse with partners of unknown or discordant serostatus, which is the sexual behavior with the highest risk for HIV transmission. Studies have consistently demonstrated that methamphetamine use is strongly associated with sexual risk behaviors,10,22–25 with users of the drug reporting an increased number of sexual partners,26 decreased use of condoms,26,27 multiple-partner sexual activities,5 engaging in sex with casual and anonymous partners,1 and engaging in unprotected receptive and insertive anal sex with casual partners.27 Research has also noted that methamphetamine users engage in higher risk sexual activities not typically practiced when not using the drug.20,22,25

The conclusion from these local projects and the research literature is consistent. The step-wise, ordered association between level of methamphetamine use and prevalence of HIV infection strongly indicates that the more intensively methamphetamine is used by MSM, (with one measure of intensity being the ability to successfully respond to low-intensity HIV-prevention efforts versus responding only to high-intensity treatment modalities), the more likely the individual is to report being HIV infected.

Implications for HIV Prevention and Substance Abuse Interventions

Evidence from a randomized controlled trial of behavioral treatment for methamphetamine dependence now shows that interventions that reduce methamphetamine use also result in reduced high-risk sexual behaviors among treatment-seeking gay men.9,22,28 Using outpatient behavioral treatments for methamphetamine dependence, immediate and sustained reductions in both methamphetamine use and unprotected anal intercourse are observed for up to one year after treatment entry.9 Findings from this trial indicated that the mechanism for these sexual risk reductions did not involve increased condom use. Instead, participants made different choices about their sexual behaviors as a result of not being under the influence of methamphetamine and consequently reduced the number of episodes of unprotected anal intercourse with partners other than primary partners.22

Information on the correspondence between the intensity of methamphetamine use, high rates of HIV-related risk behaviors, and high prevalence of HIV infection can be used to guide a comprehensive HIV-prevention strategy that addresses methamphetamine use and concomitant HIV-related sexual risk behaviors among MSM. Interventions that have the goal of educating the greater communities of MSM about methamphetamine use and high-risk sexual behaviors are low-cost methods for reducing methamphetamine use and associated HIV-transmission behaviors among those in whom use is not already entrenched. While such an approach may prevent some individuals from initiating use of methamphetamine, they might have little impact on those who already are frequent and chronic users of methamphetamine. For example, providing enhanced HIV prevention interventions in Project EXPLORE to MSM caused short-term (up to 18 months) reductions in sexual risk behaviors and seroincidence.29 Yet even in this sample, methamphetamine use independently correlated significantly with commission of HIV-related sexual risk behaviors.24 These findings indicate that prevention messages that address either methamphetamine use or HIV prevention may be helpful on a population level to reduce HIV risk behaviors. Among active and persistent drug users, these messages are likely inadequate to change behaviors either for HIV-risk or for drug use.

An alternative to reducing HIV risk behaviors using prevention interventions among methamphetamine-using MSM is to address drug-related issues as a way of reducing associated HIV-related sexual transmission behaviors. Across the population, it may be appropriate to adapt early interventions (e.g., motivational interviewing, drop-in discussion groups) that combine elements of both prevention and treatment, that require moderate levels of resources, and that encourage methamphetamine users to consider reducing or ceasing methamphetamine use.30 While these lower intensity interventions may help most gay men to reduce or eliminate methamphetamine use, a substantial group will require intensive interventions, such as behavioral drug abuse treatment. As of this writing, there are no medications that are approved for use in treating methamphetamine abuse, while behavioral therapies have shown efficacy in assisting individuals with methamphetamine dependence in discontinuing their drug use and concomitant sexual risk behaviors.9 Treatment is necessary for methamphetamine users who cannot successfully reduce or eliminate their drug use. While treatment yields a large signal for reducing methamphetamine use and sexual risk behaviors, intensive treatment approaches needed by a smaller segment of MSM are costly and likely require skilled clinicians and specialty clinic settings. These limitations are offset, however, by the capacity to significantly reduce sexual risk behaviors in a group with extremely high HIV-prevalence; thereby, methamphetamine abuse treatment functions as HIV prevention both for HIV infected and uninfected men. HIV prevention is achieved by reducing sexual risk behaviors through methamphetamine abuse treatment.

Conclusion

Despite the limitation that these projects were implemented with separate aims and with separate groups of MSM in the Hollywood and West Hollywood areas of Los Angeles County, findings from these data and those from other projects in the literature are consistent in describing step-wise associations between methamphetamine use, HIV-related sexual risk behaviors, and HIV prevalence in MSM. The overlapping nature of the epidemics of methamphetamine abuse and HIV infection within some communities of gay men in the United States31 necessitates the development of a considered and comprehensive plan for response. This need becomes more critical with newly reported methamphetamine-associated HIV strains that are resistant to multi-class antiretroviral drugs.16 HIV prevention programs may be an important and cost-efficient method for providing health education and risk reduction interventions (such as advocating for MSM to avoid or reduce methamphetamine use). Drug abuse treatment can be an efficient tool for leveraging sexual risk reductions in a high-prevalence group. Due to critical and perhaps causal behavioral linkages between methamphetamine use and sexual behaviors that increase risk of HIV transmission among methamphetamine-using MSM, a comprehensive prevention strategy should include elements of both.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Los Angeles Department of Public Health, Office of AIDS Programs and Policy (contract number H 211853), the City of Los Angeles AIDS Coordinator's Office (contract number 93427), NIDA grant 1 R01 DA11031 and the Van Ness Recovery House in conducting these programs.

Footnotes

Shoptaw is with the Department of Family Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA; Shoptaw and Reback are with the Integrated Substance Abuse Programs (ISAP), Los Angeles, CA, USA; Shoptaw and Reback are with the Friends Research Institute, Inc., Los Angeles, CA, USA; Shoptaw and Reback are with the Center for HIV Identification, Prevention and Treatment Services (CHIPTS), University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA; Reback is with the Van Ness Recovery House, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

References

- 1.Stall R, Paul JP, Greenwood G, Pollack LM, Bein E, Crosby GM, Mills TC, Binson D, Coates TJ, Catania JA, et al. Alcohol use, drug use and alcohol-related problems among men who have sex with men: the Urban Men?s Health Study. Addiction. 2001;96:1589–1601. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961115896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thiede H, Valleroy LA, MacKellar DA, Celentano DD, Ford WL, Hagan H, Koblin BA, LaLota M, McFarland W, Shehan DA, Torian LV, et al. Young Men?s Survey Study Group. Regional patterns and correlates of substance use among young men who have sex with men in 7 US urban areas. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1915–1921. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.11.1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peck JA, Shoptaw S, Rotheram-Fuller E, Reback CJ, Bierman B. HIV-associated medical, behavioral, and psychiatric characteristics of treatment-seeking, methamphetamine-dependent men who have sex with men. J Addict Dis. 2005;24:115–132. doi: 10.1300/J069v24n03_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chesney MA, Barrett DC, Stall R. Histories of substance use and risk behavior: precursors to HIV seroconversion in homosexual men. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:113–116. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.1.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenwood GL, White E, Page-Shafer K, Bein E, Paul J, Osmond D, Stall RD, et al. Correlates of heavy substance use among young gay and bisexual men: The San Francisco Young Men?s Health Study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;61:105–112. doi: 10.1016/S0376-8716(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirshfield S, Remien RH, Walavalkar I, Chiasson MA. Crystal methamphetamine use predicts incident STD infection among men who have sex with men recruited online: a nested case?control study. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2004;6:41. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6.4.e41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Molitor F, Truax SR, Ruiz JD, Sun RK. Association of methamphetamine use during sex with risky sexual behaviors and HIV infection among non-injection drug users. West J Med. 1998;168:93–97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shoptaw S, Peck J, Reback CJ, Rotheram-Fuller E. Psychiatric and substance dependence comorbidities, sexually transmitted diseases, and risk behaviors among methamphetamine-dependent gay and bisexual men seeking outpatient drug abuse treatment. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35(suppl 1):161–168. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2003.10400511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shoptaw S, Reback CJ, Peck JA, Yang X, Rotheram-Fuller E, Larkins S, Veniegas RC, Hucks-Ortiz C, et al. Behavioral treatment approaches for methamphetamine dependence and HIV-related sexual risk behaviors among urban gay and bisexual men. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;78:125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong W, Chaw JK, Kent CK, Klausner JD. Risk factors for early syphilis among gay and bisexual men seen in an STD clinic: San Francisco, 2002–2003. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32:458–463. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000168280.34424.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hutin YJ, Sabin KM, Hutwagner LC, Schaben L, Shipp GM, Lord DM, Conner JS, Quinlisk MP, Shapiro CN, Bell BP, et al. Multiple modes of hepatitis A virus transmission among methamphetamine users. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:186–192. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.2.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Semple SJ, Patterson TL, Grant I. A comparison of injection and non-injection methamphetamine-using HIV positive men who have sex with men. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;76:203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reback CJ, Larkins S, Shoptaw S. Methamphetamine abuse as a barrier to HIV medication adherence among gay and bisexual men. AIDS Care. 2003;15:775–785. doi: 10.1080/09540120310001618621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hser YI, Gelberg L, Hoffman V, Grella CE, McCarthy W, Anglin MD. Health conditions among aging narcotics addicts: medical examination results. J Behav Med. 2004;27:607–622. doi: 10.1007/s10865-004-0005-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Urbina A, Jones K. Crystal methamphetamine, its analogues, and HIV infection: medical and psychiatric aspects of a new epidemic. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:890–894. doi: 10.1086/381975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Markowitz M, Mohri H, Mehandru S, Shet A, Berry L, Kalyanaraman R, Kim A, Chung C, Jean-Pierre P, Horowitz A, Mar M, Wrin T, Parkin N, Poles M, Petropoulos C, Mullen M, Boden D, Ho DD, et al. Infection with multidrug resistant, dual-tropic HIV-1 and rapid progression to AIDS: a case report. Lancet. 2005;365:1031–1038. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71139-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Purcell DW, Mizuno Y, Metsch LR, Garfein R, Tobin K, Knight K, Latka MH, et al. Unprotected sexual behavior among heterosexual HIV-positive injection drug using men: associations by partner type and partner serostatus. J Urban Health. 2006;83:656–668. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9066-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Los Angeles County Department of Health Services, HIV Epidemiology Program. HIV/AIDS Semi-annual Surveillance Summary. Los Angeles, California: January 2006.

- 19.Reiner A. HIV risk behaviors among gay and bisexual males who use methamphetamine only, club drugs only or both. Paper presented at: the HIV Research: The Next Generation Annual Conference sponsored by CHIPTS, April 13, 2004; Los Angeles, CA.

- 20.Reback, CJ. The social construction of a gay drug: methamphetamine use among gay and bisexual males in Los Angeles, 1997 Available at: http://www.uclaisap.org/documents/final-report_cjr_1-15-04.pdf. Accessed on June 16, 2006.

- 21.Personal communication with Kathleen Watt, Executive Director, Van Ness Recovery House, Los Angeles, California, 2004. Accessed on February 7, 2006.

- 22.Reback CJ, Larkins S, Shoptaw S. Changes in the meaning of sexual risk behaviors among gay and bisexual male methamphetamine abusers before and after drug treatment. AIDS Behav. 2004;8:87–98. doi: 10.1023/B:AIBE.0000017528.39338.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Celentano DD, Valleroy LA, Sifakis F, MacKellar DA, Hylton J, Thiede H, McFarland W, Shehan DA, Stoyanoff SR, LaLota M, Koblin BA, Katz MH, Torian LV, et al. Associations between substance use and sexual risk among very young men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33:265–271. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000187207.10992.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Colfax G, Coates TJ, Husnik MJ, Huang Y, Buchbinder S, Koblin B, Chesney M, Vittinghoff E, et al. Longitudinal patterns of methamphetamine, popper (amyl nitrite), and cocaine use and high-risk sexual behavior among a cohort of San Francisco men who have sex with men. J Urban Health. 2005;82(1 suppl 1):i62–i70. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Halkitis PN, Shrem MT, Martin FW. Sexual behavior patterns of methamphetamine-using gay and bisexual men. Subst Use Misuse. 2005;40:703–719. doi: 10.1081/JA-200055393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Molitor F, Traux SR, Ruiz JD, Sun RK. Association of methamphetamine use during sex with risky sexual behaviors and HIV infection among non-injection drug users. West J Med. 2004;168:93–97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Purcell DW, Parsons JT, Halkitis PN, Mizuno Y, Woods WJ. Substance use and sexual transmission risk behavior of HIV-positive men who have sex with men. J Subst Abuse. 2001;13:185–200. doi: 10.1016/S0899-3289(01)00072-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stall RD, Paul JP, Barrett DC, Crosby GM, Bein E. An outcome evaluation to measure changes in sexual risk-taking among gay men undergoing substance use disorder treatment. J Stud Alcohol. 1999;60:837–845. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koblin B, Chesney M, Coates T, EXPLORE Study Team Effects of a behavioural intervention to reduce acquisition of HIV infection among men who have sex with men: the EXPLORE randomised controlled study. Lancet. 2004;364:41–50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16588-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kanouse DE, Bluthenthal RN, Bogart L, Iguchi MY, Perry S, Sand K, Shoptaw S, et al. Recruiting drug-using men who have sex with men into behavioral interventions: a two-stage approach. J Urban Health. 2005;82(1 Suppl 1):i109–i119. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stall R, Mills TC, Williamson J, Hart T, Greenwood G, Paul J, Pollack L, Binson D, Osmond D, Catania JA, et al. Association of co-occurring psychosocial health problems and increased vulnerability to HIV/AIDS among urban men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:939–942. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.6.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]