Abstract

Background

Clopidogrel use following drug eluting coronary artery stent (DES) implant is essential for prevention of early in-stent thrombosis, but clopidogrel use among older DES recipients has not been widely studied. We sought to identify characteristics associated with failure to fill a clopidogrel prescription and to examine the relationship between a clopidogrel prescription fill and hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction (AMI) or death.

Methods and Results

Retrospective analysis of administrative data (20% sample) for 15,996 Medicare Part D enrollees receiving a DES 2006–2007. We modeled the adjusted probability and odds of clopidogrel prescription fill within 7 and 90 days of discharge and its association with AMI hospitalization or death. 19.7% of individuals did not fill a clopidogrel prescription within 7 days of discharge, falling to 13.3% by day 90. The adjusted probability of filling a clopidogrel prescription within 7 or 90 days of discharge was lower for patient with dementia (20.2% less likely, 95% CI 10.4–30.1%), depression (10.7% less likely, 95% CI 6.9–14.5%), age >84 compared to age 65–69 (10.6% less likely, 95% CI 8.6–12.7%), black race (6.6% less likely, 95% CI 4.2–9.0%), intermediate levels of medication cost-share (5.2% less likely, 95% CI 2.9–7.6%), and female sex (3.3% less likely, 95% CI 2.1–4.5%). It was higher for patients initially hospitalized for an AMI (12.5% more likely, 95% CI 11.3–13.6%). Failure to fill a clopidogrel prescription within 7 days of discharge was associated with a higher adjusted odds ratio of death during days 8–90 (OR 2.44, 95% CI 1.76–3.38) but was not associated with an increased risk of hospitalization for AMI.

Conclusions

One in five patients failed to fill a prescription for clopidogrel following DES at 7 days and one in seven failed by 3 months. Individual characteristics available at the time of hospital discharge were associated with a clopidogrel prescription fill. Those mostly strongly associated with nonadherence, including age >84, not having an AMI, depression, and dementia, may guide clinicians and health systems seeking to target this high-risk population and improve health outcomes following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Keywords: stents, coronary disease, medication adherence

Introduction

Drug-eluting coronary artery stents (DES) are the second most commonly implanted medical devices among older Americans.1 Unlike most implanted medical devices, the safety of a drug-eluting stent depends on adherence to a potent oral anti-platelet agent such as clopidogrel, a thienopyridine platelet aggregation inhibitor, taken daily for at least 3–12 months following stent placement. Premature discontinuation of clopidogrel following DES has been associated with a 30-fold increase in the risk of in-stent thrombosis and a 10-fold increase in the risk of death.2–8 Because older Americans are at high risk for medication nonadherence, use of a DES in this population may carry additional risk. 9

Almost all prior studies examining very early discontinuation of clopidogrel focus on patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI). These studies include patients younger on average than most Medicare enrollees. 10–13 The availability of Medicare Part D prescription data now permits an analysis of clopidogrel prescription fill patterns in a national sample of older DES recipients, with or without an AMI, treated outside of clinical trials.

We analyzed a large sample of Medicare Part D beneficiaries receiving a DES during an acute care hospitalization to identify characteristics associated with failure to fill a clopidogrel prescription within 7 and 90 days of discharge. We then examined the relationship between a clopidogrel fill and the health outcomes of hospitalization for AMI or death. We hypothesized that factors known at the time of hospital discharge such as age, sex, race, income, comorbidities and prescription cost-share would be associated with a lower likelihood of prescription fill and could identify individuals at risk of non-adherence. Based on previous literature, we also hypothesized that failure to fill a clopidogrel prescription would be associated with increased risk of cardiovascular events and death.14

Methods

Data

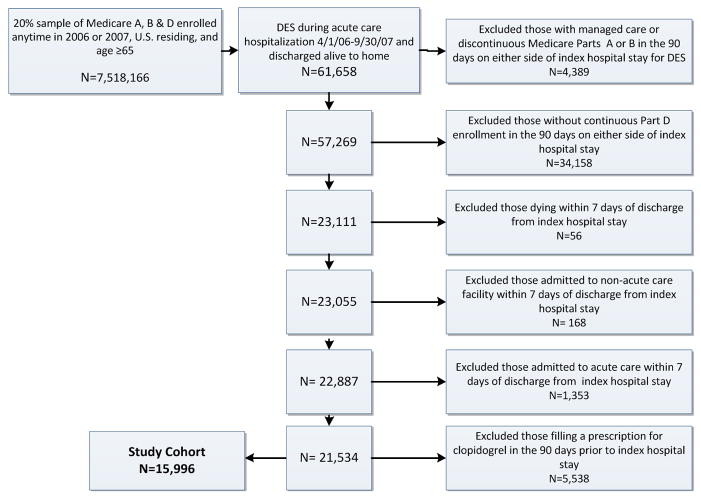

From a 20% sample of Medicare beneficiaries, we used Medicare Denominator and Inpatient Files to create a principal cohort of individuals age 65 or older, enrolled in fee-for-service Parts A, B and D, residing in the U. S., hospitalized in an acute care facility and discharged to home between April 1, 2006 and September 30, 2007, with a discharge billing code indicative of receiving a DES (ICD-9 36.07, DRG 526, 527, 246, 247). We excluded patients with any managed care enrollment or discontinuous Part D enrollment in the 90 days before or after index hospitalization. Because we sought to assess outpatient prescription fills, we excluded individuals who died or were admitted to an acute or non-acute care facility (e.g. nursing home) in the first 7 days after hospital discharge. To account for individuals who did not fill a prescription for clopidogrel because they had been using it prior to their index hospitalization and thus may have had a supply at home, we excluded individuals who filled a prescription for clopidogrel in the 90 days preceding index admission. A cohort creation flow chart is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Cohort Creation Flow Chart

Prescription Fill Measures and Health Outcomes

We used the Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Event (PDE) file to create dichotomous variables indicating if a patient filled at least one prescription for clopidogrel in the first seven and the first ninety days after the day of discharge from the index hospitalization. Hospital readmission for AMI in the 90 days following index DES discharge was determined by identifying acute care admissions with a diagnosis of AMI in the first or second claims position.15 The supplemental data table lists all ICD9 and diagnosis codes used in our analysis. Date of death was obtained from the Denominator Files.

Covariates

Our analysis also included covariates which we hypothesized could influence filling a clopidogrel prescription. We determined age at time of index admission and race (classified as Black or nonblack) from the Denominator File. We followed a modified version of Iezonni’s methods to identify up to 13 comorbidities for each patient based on ICD-9 diagnoses present on index DES hospitalization discharge claims. 16–18 We similarly identified significant hemorrhage following the methods of Buresly, defined as: intracranial, gastrointestinal, or intra-ocular hemorrhages, aortic rupture, aortic dissection, hematuria, hemoptysis, epistaxis or hemorrhage NOS.19 From PDE files we identified prescriptions fills for warfarin because its use might impact the decision to prescribe clopidogrel. We also identified other medications commonly prescribed after DES in order to compare fill rates, including: β-blockers, HMG CoA reductase inhibitors (statins), and proton pump inhibitors. Residential ZIP code was used to assign each patient an estimated race-specific, household income and a proportion of the population living in poverty based on 2000 Census data.20 We ascertained Part D low-income subsidy status through the Denominator file and categorized it dichotomously. This resource-tested subsidy is offered to enrollees with an annual income below 150% of the federal poverty level.21 Hospitals were categorized as academic medical centers (AMC) using the American Association of Medical Colleges definition.22, 23 We recorded calendar year of index hospitalization as well (2006 or 2007) because of reported temporal trends in the selection criteria for DES.24

Patient prescription expenditures were measured in two ways: as a patient payment per pill and as a co-insurance or cost-share rate (patient payment/total prescription cost). Patient payment allows an assessment of the absolute cost paid by an individual for clopidogrel but is unavailable for those individuals who did not fill a prescription. To study the impact of cost exposure for all individuals, we calculated an individual-level, mean co-insurance rate using all of each patient’s Part D prescription fills (both clopidogrel and non-clopidogrel medications). This co-insurance rate reflects the patient’s comprehensive prescription cost-share experience. For patients with no prescription drug fills (2.0 % of the cohort), we followed the methods of Goldman et al. in setting co-insurance rates equal to the mean of other cohort members of the same race, race-specific median household income quartile, Part D subsidy status, and state.25 Cost share was categorized based on natural data breaks as <10%, 10–19%, 20–40% and > 40%.

Statistical Analysis

Prescription Fill Models Using Restricted Cohort

To assess characteristics associated with a clopidogrel prescription being filled by individuals residing in the community, we created a restricted cohort by excluding from the main cohort patients who died in the 90 days following hospital discharge and those who spent more than 20% of the first 90 post-discharge days institutionalized (e.g. in acute care facility, or skilled nursing home). We hypothesized that the remaining individuals would have sufficient opportunity to fill prescriptions at an outpatient pharmacy. We assessed clopidogrel fill within seven and 90 days of index discharge using logistic models with random facility-level effects. In order to build a model that would be useful to hospital providers, we used only those covariates that would be available at the time of hospital discharge. Because odds ratios do not approximate relative risk for these common outcomes, we used these logistic models to calculate the adjusted probability of fill associated with each variable using the STATA 11.0 Margin (dydx) function. This derivative function provides the adjusted probability associated with each variable, assuming all other variables remain unchanged.26 Results are also provided in the form of odds ratios in appendix C.

Health Outcomes Models Using Unrestricted Cohort

To determine the association between clopidogrel fill within 7 days of hospital discharge and risk of death, we included all members of the original cohort in logistic models for which the dependent variables were death, hospitalization for AMI, and a combined endpoint of both death and AMI in days 8 to 90 following index hospitalization. We used the same covariates as in the prescription fill model, except that co-insurance rate was replaced by receipt of the low-income subsidy, which we hypothesized to be a more likely determinant of health outcomes.

All analyses were conducted using SAS v9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) and STATA v11.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). All statistical tests were two-sided with statistical significance defined as p <0.05. To account for multiple comparisons, we also report p<0.01 and <0.001. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Dartmouth College.

Results

Cohort Characteristics

For the principal cohort, we identified 15,996 U.S. residing patients, age 65 or older, who received a DES during acute hospitalization, were discharged to home alive, did not die or get admitted to an acute or non-acute care facility in the first 7 days after hospitalization and did not fill a clopidogrel prescription in the 90- days preceding this hospitalization (Figure 1). Table 1 shows characteristics of the main study cohort, stratified by whether or not they filled a prescription for Clopidogrel in the first 7 days following discharge from index hospitalization. Mean cohort age was 74.5 years; 50.2% were female; 6.9% were black. Only a minority of DES placements (26.1%) occurred during an admission with a primary diagnosis of AMI. Comorbidities were common, with diabetes, chronic pulmonary disease, and congestive heart failure diagnosed in 30.4%, 13.2%, and 16.9% of individuals, respectively. Diagnoses associated with hemorrhage were rare (1.3%).

Table 1.

Cohort Characteristics

| Total | No Clopidogrel Fill in Day 0–7, % | Any Clopidogrel Fill in Day 0–7 % | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 15,996 | 3,159 (19.7) | 12,837 (80.3) | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, years; mean (SD) | 74.5 (6.5) | 75.6 (7.1) | 74.2 (6.3) | <0.001 |

| Female | 50.2 | 55.7 | 48.9 | <0.001 |

| Black race | 6.9 | 10.8 | 6 | <0.001 |

| Low income subsidy | 33.9 | 37.3 | 33.1 | <0.001 |

| Income by zip code, $; mean (SD) | 41,687 (17,644) | 41,561 (18,188) | 41,718 (17,508) | 0.66 |

| Poverty rate by zip code | 10.7 | 11.3 | 10.6 | <0.001 |

| Prescription Cost-share; mean % | 28.5 | 27.8 | 28.7 | 0.03 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| AMI, index hospitalization | 26.1 | 14.0 | 29.1 | <0.001 |

| STEMI | 10.5 | 5.3 | 11.7 | <0.001 |

| NSTEMI | 15.6 | 8.6 | 17.3 | <0.001 |

| Unstable Angina | 37.7 | 27.3 | 40.3 | <0.001 |

| Depression | 3.5 | 5.2 | 3.1 | <0.001 |

| Heart Failure | 16.9 | 17.4 | 16.7 | 0.33 |

| Renal disease | 7.6 | 9 | 7.2 | 0.0009 |

| Cancer | 3.9 | 4.8 | 3.7 | 0.0044 |

| Hemorrhage | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 0.87 |

| Liver disease | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.32 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 30.4 | 32.3 | 29.9 | 0.01 |

| Dementia | 0.7 | 1.7 | 0.5 | <0.001 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.42 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 2.8 | 3.2 | 2.7 | 0.12 |

| Pulmonary disease | 13.2 | 13.2 | 13.2 | 0.98 |

| Hospitalization | ||||

| Year 2007 vs. 2006 | 44.8 | 44.9 | 44.8 | 0.91 |

| Academic medical center | 8.4 | 7.6 | 8.6 | 0.06 |

| Length of Stay, mean days (SD) | 2.8 (2.7) | 2.7 (2.5) | 2.8 (2.7) | 0.54 |

| Follow-up Care during Days 0–90 | ||||

| Cardiology Outpatient Visit | 74.1 | 54.1 | 79 | <0.001 |

| Primary Care Outpatient Visit | 74.3 | 73.1 | 74.6 | 0.08 |

| Proton pump inhibitor fill | 29 | 23.3 | 30.4 | <0.001 |

| Statin fill | 71.1 | 43.7 | 77.8 | <0.001 |

| Beta blocker | 69.2 | 47.7 | 74.4 | <0.001 |

| Warfarin fill | 9.9 | 11.3 | 9.5 | 0.0025 |

| Outcomes during Days 8–90 | ||||

| Acute Care Days; mean (SD) | 1.5 (6.0) | 2.4 (8.4) | 1.3 (5.3) | <0.001 |

| Revascularization | 6.2 | 4.2 | 6.7 | <0.001 |

| PCI | 5.9 | 4 | 6.4 | <0.001 |

| CABG | 0.3 | NR | NR | 0.74 |

| AMI | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.7158 |

| Deaths | 1.1 | 2.2 | 0.8 | <0.001 |

| Myocardial Infarction and Death | 1.9 | 3.0 | 1.7 | <0.001 |

AMI type and comorbidities are based on diagnoses from index admission. AMI outcomes were based on the diagnosis code for AMI found in any position in the administrative data. Residential ZIP code was used to assign each patient an estimated race-specific, household income and a proportion of the population living in poverty based on 2000 Census data. Chi squared and t-tests were used assess statistical difference across the two clopidogrel fill strata/groups. NR= not reported due to Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services restrictions on reporting cell counts <11. Statin = HMG CoA Reductase Inhibitor.

Cost

The Medicare Part D low-income subsidy was common (33.9%) and had a significant impact on out-of-pocket expense for clopidogrel (median cost $0.98 per pill without the subsidy and $0.10 per pill with the subsidy) (Table 2). The mean co-insurance or cost-share rate that individuals faced for all of their prescriptions was 28.5%.

Table 2.

Clopidogrel Prescription Fill Characteristics

| Filled in day 0–7 (%) | 80.3 |

| Filled in day 0–90 (%) | 86.7 |

| Time to fill, mean days (SD) | 2.8 (10.3) |

| Patient out-of-pocket cost per pill, median $ | 0.67 |

| Without low income subsidy, median $ | 0.98 |

| With low income subsidy, median $ | 0.10 |

Prescription Fills

For the restricted cohort of those surviving 90 days after discharge, we identified 15,542 individuals; 19.7% of these individuals did not fill a clopidogrel prescription within 7 days of discharge, falling to 13.3% by day 90 (Table 2). The mean time to prescription fill was 2.8 days (standard deviation 10.3 days) with a median time of 0 days. This group differed significantly from those who did fill a prescription in terms of race, gender, economic status, and comorbidities (Table 1). They were less likely to see a cardiologist over the subsequent 3 months (54.1% vs. 79.0%, p <0.001); there was no difference in primary care follow up visits. Table 3 shows the adjusted probability of filling a clopidogrel prescription associated with each covariate. The strongest independent predictors of failing to fill a prescription for clopidogrel at both 7 and 90 days were: age >84 (compared to 65–69), black race (compared to non-black), female sex, prescription co-insurance of 10–19% compared with <10%, and diagnosis of depression or dementia. Dementia was the strongest predictor of not filling a clopidogrel prescription after discharge (22.0% less likely (95% CI 11.9–32.2) by 7 days and 20.2% less likely (95% CI 10.4–30.1) by 90 days). Diagnosis of AMI was the strongest predictor of successfully filling a prescription (13.2% more likely (95% CI 11.8–14.6) by 7 days and 12.5% more likely (95% CI 11.3–13.6) by 90 days).

Table 3.

Adjusted Probabilities of a Clopidogrel Prescription Fill in the First 7 and First 90 Days Following Hospitalization with Receipt of a Drug Eluting Coronary Artery Stent

| Clopidogrel Fill days 0 to 7 | 95% CI | Clopidogrel Fill days 0 to 90 | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age 70 to 74 | −0.016 | [−.034,.002] | −0.008 | [−.024,.008] |

| Age 75 to 79 | −0.016 | [−.035,.003] | −0.01 | [−.027,.007] |

| Age 80 to 84 | −.029** | [−.050,−.008] | −.024* | [−.043,−.006] |

| Age >84 | −.102** | [−.126,−.077] | −.106** | [−.127,−.086] |

| Black | −.084** | [−.112,−.057] | −.066** | [−.090,−.042] |

| Female | −.032** | [−.046,−.019] | −.033** | [−.045,−.021] |

| Income 2nd Quartile | 0.007 | [−.013,.027] | 0.003 | [−.015,.021] |

| Income 3rd Quartile | −0.016 | [−.038,.005] | −0.01 | [−.029,.009] |

| Income Top Quartile | −0.011 | [−.035,.012] | −0.012 | [−.033,.009] |

| Poverty | −0.081 | [−.190,.028] | −0.079 | [−.174,.016] |

| Co-insurance 10%–19% | −.069** | [−.097,−.041] | −.052** | [−.076,−.029] |

| Co-insurance 20%–40% | −.030** | [−.048,−.013] | −.017* | [−.033,−.002] |

| Co-insurance > 40% | 0.002 | [−.016,.020] | .020* | [.004,.036] |

| Stent in 2007 vs. 2006 | 0.002 | [−.011,.015] | −0.004 | [−.016,.007] |

| Length Of Stay > Median | −.026** | [−.042,−.011] | −.031** | [−.045,−.017] |

| AMI | .132** | [.118,.146] | .125** | [.113,.136] |

| Peptic Ulcer | 0.01 | [−.070,.090] | −0.015 | [−.090,.060] |

| Liver Disease | −0.068 | [−.207,.072] | −0.12 | [−.260,.020] |

| Cerebrovascular Disease | −0.017 | [−.057,.023] | 0.002 | [−.031,.035] |

| Renal Disease | −.036* | [−.063,−.008] | −.033** | [−.057,−.008] |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 0 | [−.018,.018] | 0.008 | [−.008,.023] |

| Hemorrhage | −0.005 | [−.066,.055] | 0.021 | [−.027,.069] |

| Depression | −.090** | [−.129,−.050] | −.107** | [−.145,−.069] |

| Diabetes Mellitus | −.015* | [−.029,−.000] | −0.002 | [−.015,.010] |

| Dementia | −.220** | [−.322,−.119] | −.202** | [−.301,−.104] |

| Pulmonary Disease | −0.001 | [−.021,.019] | −0.006 | [−.024,.011] |

| Cancer | −.046* | [−.084,−.009] | −.067** | [−.103,−.030] |

| Warfarin Prescription | −.024* | [−.047,−.001] | −.031** | [−.052,−.010] |

| Academic Medical Center | .040* | [.008,.072] | .051** | [.019,.083] |

Estimates are the adjusted probabilities obtained using the margin dydx function in STATA 11.0, following logistic regression modeling with random facility level effects.

p<0.05,

p<0.01 Age is compared with age 65–69. Black race is compared to non-black. Income is compared with first quartile. Co-insurance is compared with <10%. Residential ZIP code was used to assign each patient an estimated race-specific, household income and a proportion of the population living in poverty based on 2000 Census data. Coinsurance rate is the mean individual level coinsurance for all Part D events; reference rate is <10%.

Health Outcomes

In the 90 days following index hospitalizations, those who did not fill a prescription for clopidogrel in the 7 days following discharge spent more days hospitalized (2.4 vs. 1.3 days, p<0.001) and were more likely to die (2.2% vs. 0.8%, p<0.001) but underwent less PCI (4.0% vs. 6.4%, p<0.001) compared with those who did fill a prescription (table 1). Rates of bypass surgery and hospitalization for AMI in the 90 days after index hospitalization did not differ between groups. Failure to fill a clopidogrel prescription in the first 7 days after discharge carried an adjusted odds ratio of 2.44 for death during days 8–90 (CI 1.76, 3.38). (Table 4)

Table 4.

Adjusted Odds of Death and Acute Myocardial Infarction in the 8 to 90 Days Following Discharge from Hospitalization with Receipt of Drug Eluting Coronary Artery Stent

| Death Days 8 to 90 | 95% CI | AMI days 8 to 90 | 95% CI | AMI or Death days 8 to 90 | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Clopidogrel Prescription | 2.44** | [1.76,3.38] | 1.16 | [0.78,1.74] | 1.83** | [1.42,2.37] |

| Fill Within 7 days of discharge | ||||||

| Age 70 to 74 vs. 65–70 | 1.17 | [0.73,1.86] | 1.11 | [0.72,1.71] | 1.08 | [0.78,1.49] |

| Age 75 to 79 vs. 65–70 | 1.24 | [0.77,2.00] | 1.07 | [0.68,1.70] | 1.06 | [0.76,1.49] |

| Age 80 to 84 vs. 65–70 | 1.57 | [0.96,2.58] | 0.87 | [0.50,1.50] | 1.07 | [0.74,1.56] |

| Age >84 vs. 65–70 | 2.50** | [1.47,4.27] | 0.97 | [0.50,1.88] | 1.63* | [1.08,2.45] |

| Black | 0.72 | [0.39,1.32] | 0.82 | [0.40,1.68] | 0.82 | [0.51,1.31] |

| Female | 0.85 | [0.62,1.18] | 1 | [0.72,1.40] | 0.92 | [0.72,1.17] |

| Income 2nd Quartile vs. 1st | 0.82 | [0.52,1.28] | 1.33 | [0.83,2.14] | 1 | [0.72,1.39] |

| Income 3rd Quartile vs. 1st | 0.87 | [0.55,1.39] | 0.98 | [0.58,1.67] | 0.85 | [0.59,1.22] |

| Income Top Quartile vs. 1st | 0.78 | [0.46,1.31] | 1.28 | [0.73,2.22] | 0.98 | [0.66,1.44] |

| Poverty | 2.5 | [0.27,23.67 | 0.45 | [0.03,6.42] | 1.35 | [0.24,7.69] |

| Low Income Subsidy | 1.48* | [1.06,2.08] ] | 1.84** | [1.30,2.60] | 1.55** | [1.21,1.98] |

| Stent in 2007 vs. 2006 | 0.86 | [0.63,1.18] | 1.2 | [0.87,1.65] | 0.98 | [0.78,1.23] |

| Length of Stay > Median | 1.92** | [1.36,2.70] | 1.21 | [0.84,1.74] | 1.56** | [1.21,2.01] |

| AMI | 0.93 | [0.65,1.35] | 1.84** | [1.28,2.63] | 1.38* | [1.06,1.79] |

| Peptic Ulcer Disease | 0 | [0.00,.] | 1.73 | [0.42,7.20] | 0.94 | [0.23,3.88] |

| Liver Disease | 1.71 | [0.22,13.07 | 1.61 | [0.22,11.99 | 1.76 | [0.41,7.50] |

| Cerebrovascular Disease | 2.03* | [1.01,4.06] ] | 0.98 | [0.36,2.68] ] | 1.6 | [0.91,2.84] |

| Renal Disease | 2.73** | [1.86,4.01] | 2.00** | [1.29,3.11] | 2.40** | [1.78,3.23] |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 1.81** | [1.29,2.55] | 1.54* | [1.06,2.24] | 1.65** | [1.27,2.14] |

| Hemorrhage | 0.5 | [0.12,2.10] | 1.13 | [0.35,3.62] | 0.8 | [0.32,1.98] |

| Depression | 0.8 | [0.32,1.99] | 1.5 | [0.73,3.11] | 1.09 | [0.60,1.97] |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 1.13 | [0.81,1.58] | 1.24 | [0.88,1.74] | 1.11 | [0.87,1.42] |

| Dementia | 1.33 | [0.40,4.44] | 1.81 | [0.43,7.59] | 1.66 | [0.65,4.20] |

| Pulmonary Disease | 2.02** | [1.42,2.89] | 1.67** | [1.14,2.46] | 1.84** | [1.40,2.41] |

| Cancer | 4.51** | [2.85,7.14] | 0.92 | [0.37,2.27] | 2.78** | [1.85,4.17] |

| Warfarin Prescription | 1.31 | [0.86,2.00] | 1.21 | [0.74,1.96] | 1.26 | [0.90,1.75] |

| Academic Medical Center | 1.09 | [0.64,1.85] | 1.26 | [0.76,2.11] | 1.14 | [0.78,1.67] |

Death and AMI measured in the 8 to 90 days after index hospitalization. Odds ratios are from logistic regression modeling with random facility level effects.

p<0.05,

p<0.01 Black race is compared to non-black Residential ZIP code was used to assign each patient an estimated race-specific, household income and a proportion of the population living in poverty based on 2000 Census data

Sensitivity Analyses

We performed sensitivity analyses to assess the underlying assumptions of our models. We repeated our analysis on a larger cohort that included individuals who had filled a prescription for clopidogrel in the 90 days prior to index hospitalization. We also used a Poisson regression to model predictors of prescription fills. These approaches attenuated the strength but not the direction of associations. Predictors of prescription fills did not differ significantly. To further investigate the relationship between early prescription fill and AMI, we excluded individuals who died in the first 30 and 90 days post-discharge. To investigate survival bias, we repeated our analysis of prescription fills using the unrestricted cohort that included individuals dying during days 8–90 after discharge (Appendix B). We also included covariates for beta-blocker, statin and proton pump inhibitor prescription fills. These alternate analyses produced estimates very similar to the original models.

Discussion

We found a fifth of individuals in this national cohort of Part D enrolled, older DES recipients failed to fill a prescription for clopidogrel within a week of hospital discharge, and one in seven had not filled a prescription by 90 days. Patients who were Black, over the age of 80, had not had an AMI, or were diagnosed with depression or dementia were significantly less likely to fill a prescription for clopidogrel. This is particularly concerning given that failure to fill a prescription was associated with a significant increase in the adjusted risk of death. Overall, these findings suggest that expanded prescription coverage via the Medicare Part D benefit is not, by itself, sufficient to address barriers in effectively delivering clopidogrel to those who need it after PCI. Medication adherence is an issue of growing concern for those working to improve health system performance and offers a rare opportunity to simultaneously improve health outcomes while reducing costs.27 Professional societies have recognized the problem of clopidogrel nonadherence in particular with the publication of a joint statement in 2007 recommending broad collaboration between healthcare industry, insurers, government, and the pharmaceutical industry to eliminate barriers to appropriate clopidogrel therapy.28

Unfortunately, nonadherence remains both common and difficult to detect.29 Our results offer one possible approach for stakeholders addressing this issue – identification of those at high risk for medication nonadherence prior to hospital discharge. Using patient characteristics associated with failure to fill a prescription, providers can identify individuals less likely to receive appropriate clopidogrel therapy after leaving the hospital. This may appeal to hospitals as they seek to improve quality of care at the time of hospital discharge.

For example, patients coded as having dementia during their index hospitalization were 20.5% less likely to fill any prescriptions for clopidogrel over the ensuing 90 days. Inadvertent medication nonadherence has been associated with dementia among elderly patients.30 Cognitive function among older patients appears inversely related to ability to manage medications.31 This may explain why depression was also significantly associated with failure to fill a prescription. Hospitals and physicians should consider additional efforts to improve adherence to clopidogrel therapy when a DES is placed in an older individual with depression or dementia. Another possible explanation for nonadherence to clopidogrel following DES may be found in the design of the low-income subsidy of the Medicare Part D benefit. The low-income subsidy is, by definition, related to a patient’s financial resources and determines a patient’s co-insurance or cost-share. The low-income subsidy had a profound impact on the median cost to the patient of a clopidogrel tablet, lowering it from $0.98 to $0.10 per pill. We found those who paid 10–19% of the total cost of all their prescriptions were significantly less likely to fill their clopidogrel prescription than patients who paid 0–9% of the cost. This association was not as clear for individuals responsible for larger proportions of their medication costs, perhaps because patients become less cost-sensitive as their income rises. This sensitivity to the cost of clopidogrel has been shown previously with elderly Medicare beneficiaries increasing their use of clopidogrel by 11% over a single year after transitioning from no prescription insurance to Medicare Part D coverage.32 These results suggest that bundling a low-cost-share clopidogrel benefit with DES procedures might improve early delivery of this essential medication and decrease health disparities.

While we found Black race predicted a lower probability of filling a prescription for clopidogrel, it remains unclear why this is the case. One possibility is that clopidogrel is underprescribed for these patients. In the CRUSADE registry tracking individuals with non-ST elevation AMI, black patients were significantly less likely to receive a prescription for clopidogrel at the time of hospital discharge.33 It has been suggested that difference between Black and non-Black health outcomes after AMI are due to variations in practice patterns that occur at the hospital, rather than individual, level.34 Racial differences in both prescribing practices and medication adherence after placement of a DES should remain a focus of investigation and quality improvement efforts.

We found that patients who received a DES outside the setting of an AMI were significantly less likely to fill a prescription for clopidogrel by 90 days, an association also found in the use of statin therapy following a recent cardiac event.35 For patients who do not experience a recent AMI, we cannot determine whether failure to use clopidogrel is due to the patient’s own perception of risk or a consistent difference in how health care is delivered during and after hospital discharge.36,37 The importance of this latter factor is suggested by our finding that patients who failed to fill their clopidogrel prescription were significantly less likely to see a cardiologist in the following 90 days even though they were no less likely to see a primary care provider. For individuals with AMI, both inpatient care by a cardiologist and predischarge medication counseling have been shown to predict improved medication adherence.13 We observed a clopidogrel prescription fill rate of 86.7% by 90 days, which is similar to rates reported for other cohorts both in Canada and in the United States. Using a registry of PCI performed in Ontario, Canada, Jackevicius et al reported clopidogrel prescription fill after stent placement of 64% at time of hospital discharge, 88% within 30 days of discharge, and 91% within 90 days of discharge.11 Spertus et al, using the PREMIER multicenter AMI registry, found that, 30 days after discharge, 86.4% of patients self-reported clopidogrel use.12 It is notable that they found not completing high school to be the only independent predictor of premature discontinuation of clopidogrel, possibly due to lack of statistical power. Ho et al, in a study of 7402 individuals who received a DES through large managed care organizations in California, Colorado, and Minnesota, found that 83.7% filled a prescription for clopidogrel on the day of discharge.38 Ferreira-Gonzalez et al, in a prospective study of Spanish patients, found that only 3% of individuals had discontinued clopidogrel by 3 months of follow-up, rising to 14.4% by 12 months.39

Taken together, these studies support our finding of a large and persistent subpopulation who does not receive guideline-recommended antiplatelet therapy following implantation of a coronary artery DES. In our study, these individuals were significantly less likely to receive their DES during an AMI, visit a cardiologist, or receive repeat revascularization during the following 3 months even though they were equally likely to follow up with their primary care provider. In light of this, it is remarkable that they experienced the same risk of hospitalization for AMI as those who did fill a prescription for clopidogrel. One possible explanation is that lack of clopidogrel in this particular subpopulation leads to in-stent restenosis and stable angina more often than in-stent thrombosis and recurrent AMI. Another possibility is that they are less likely to be re-hospitalized for AMI because they do not survive to admission. Finally, it is possible that Medicare Part D enrollees who receive stents electively have, overall, less severe coronary artery disease but worse overall health.

Limitations

Our study has limitations common to claims-based analyses. The coding of comorbidities we rely on may reflect regional variation in diagnostic or billing practices rather than actual disease prevalence.40 Claims data do not reflect severity of each disease. For example, repeat revascularization may represent PCI for stable angina among individuals who are more likely to follow-up with, and be treated more aggressively by, a cardiologist. Alternately, it may represent a group with more severe coronary artery disease that is associated with recurrent and symptomatic obstructive coronary disease. Despite this, previous studies have shown that models built on Medicare claims data capture cardiovascular disease patterns well.41 The associations we report may be biased by unobserved confounders. For example, sicker patients or patients known to be dying may be less likely to obtain outpatient prescriptions. Furthermore, our analysis excludes those who do not survive 7 days from hospital discharge. These results may not be generalizable outside the population of fee-for-service Medicare Part D beneficiaries. We rely on prescription fill records as a measure of prescription use. We have no data on prescriptions written and not filled. Fill records may overestimate true adherence to medications. A prescription fill is an essential early step in prescription drug adherence, and, in studies of other medications, prescription fill has been shown to correlate with prescription use and clinical outcomes.42–45 Numerous provider and patient factors have been identified as causes of failure to fill prescriptions.46

Strengths

Our study is the first to assess clopidogrel use among a broad cross-section of older Americans, a group that commonly reports nonadherence to medications.47 Patients without employer-sponsored prescription insurance and dual-eligible (Medicare and Medicaid) individuals are disproportionately represented in the Medicare Part D program, and while this limits generalizability, our cohort reflects the general population of seniors enrolled in Part D program in terms of sex, race and income.48

We avoid indication bias, seen when illness severity is associated with the likelihood of receiving the treatment, by restricting our study to a population in which almost every individual should receive the treatment of interest, regardless of illness severity. 49 Restriction of this sort has proven particularly useful when analyzing administrative data, as was recently shown in an analysis of stress testing prior to PCI.50

Disagreement remains regarding the optimal length of therapy with clopidogrel after receiving a DES. Guidelines have moved in the direction of longer therapy and, while at least 12 months is now recommended after PCI with DES, stent package inserts still recommend only 3–6 months.51 Our cohort data are from a time period between the release of the 2005 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/Society for ardiac ngiography and Intervention practice guidelines for post-PCI care and the release of their 2007 update. During this period, clopidogrel therapy was recommended for at least 3 months after placement of all DES (3 months for sirolimus-coated and 6 months for paclitaxel-coated stents).

Conclusion

A significant portion of older adults enrolled in Medicare Part D fail to fill a prescription for clopidogrel in the 90 days following PCI with DES. This is worrisome in light of the association we and others have found between failure to fill a prescription for clopidogrel and the adjusted risk of death. Individual characteristics available at the time of hospital discharge, including sex, age, race, the diagnoses of dementia or depression, and the absence of AMI identify patients at highest risk of failing to initiate this essential therapy. Clinicians should identify patients at high risk of nonadherence with clopidogrel. Health systems should develop quality improvement initiatives that target this high-risk population in order to improve health outcomes following PCI.

Supplementary Material

What is Known

Premature discontinuation of clopidogrel after receiving a drug-eluting stent (DES) increases the risk of in-stent thrombosis and death after percutaneous coronary intervention.

Prior studies report prescription fill rates between 86–88% by 30 days after discharge.

The Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit was designed to improve access to medications for older Americans but the current rates for filling a prescription for clopidogrel after DES are unknown.

What this Article Adds

Almost 1 in 5 patients treated with DES between 2006–7 did not fill a prescription for clopidogrel within a week of hospital discharge, and one in seven had not filled one within 90 days.

Patient characteristics associated with not filling a prescription for clopidogrel included a diagnoses of dementia or depression, age >84, black race, female sex, and intermediate levels of medication copay.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: NIH/National Institute on Aging grant P01 AG019783 (Skinner & Morden)

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None

References

- 1.CMS Dashboard. www.cms.gov/dashboard.

- 2.Iakovou I, Schmidt T, Bonizzoni E, Ge L, Sangiorgi GM, Stankovic G, Airoldi F, Chieffo A, Montorfano M, Carlino M, Michev I, Corvaja N, Briguori C, Gerckens U, Grube E, Colombo A. Incidence, predictors, and outcome of thrombosis after successful implantation of drug-eluting stents. JAMA. 2005;293:2126–2130. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.17.2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petersen JL, Barron JJ, Hammill BG, Cziraky MJ, Anstrom KJ, Wahl PM, Eisenstein EL, Krucoff MW, Califf RM, Schulman KA, Curtis LH. Clopidogrel use and clinical events after drug-eluting stent implantation: Findings from the healthcore integrated research database. Am Heart J. 2010;159:462–470.e461. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eisenstein EL, Anstrom KJ, Kong DF, Shaw LK, Tuttle RH, Mark DB, Kramer JM, Harrington RA, Matchar DB, Kandzari DE, Peterson ED, Schulman KA, Califf RM. Clopidogrel use and long-term clinical outcomes after drug-eluting stent implantation. JAMA. 2007;297:159–168. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.2.joc60179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schulz S, Schuster T, Mehilli J, Byrne RA, Ellert J, Massberg S, Goedel J, Bruskina O, Ulm K, Schömig A, Kastrati A. Stent thrombosis after drug-eluting stent implantation: Incidence, timing, and relation to discontinuation of clopidogrel therapy over a 4-year period. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2714–2721. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Werkum JW, Heestermans AA, Zomer AC, Kelder JC, Suttorp M-J, Rensing BJ, Koolen JJ, Brueren BRG, Dambrink J-HE, Hautvast RW, Verheugt FW, ten Berg JM. Predictors of coronary stent thrombosis: The dutch stent thrombosis registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1399–1409. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park D-W, Yun S-C, Lee S-W, Kim Y-H, Lee CW, Hong M-K, Cheong S-S, Kim J-J, Park S-W, Park S-J. Stent thrombosis, clinical events, and influence of prolonged clopidogrel use after placement of drug-eluting stent: Data from an observational cohort study of drug-eluting versus bare-metal stents. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;1:494–503. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brar SS, Kim J, Brar SK, Zadegan R, Ree M, Liu I-LA, Mansukhani P, Aharonian V, Hyett R, Shen AY-J. Long-term outcomes by clopidogrel duration and stent type in a diabetic population with de novo coronary artery lesions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:2220–2227. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vik SA, Maxwell CJ, Hogan DB. Measurement, correlates, and health outcomes of medication adherence among seniors. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:303–312. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pallares MJ, Powers ER, Zwerner PL, Fowler A, Reeves R, Nappi JM. Barriers to clopidogrel adherence following placement of drug-eluting stents. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43:259–267. doi: 10.1345/aph.1l286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jackevicius CA, Tu JV, Demers V, Melo M, Cox J, Rinfret S, Kalavrouziotis D, Johansen H, Behlouli H, Newman A, Pilote L. Cardiovascular outcomes after a change in prescription policy for clopidogrel. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1802–1810. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0803410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spertus JA, Kettelkamp R, Vance C, Decker C, Jones PG, Rumsfeld JS, Messenger JC, Khanal S, Peterson ED, Bach RG. Prevalence, predictors, and outcomes of premature discontinuation of thienopyridine therapy after drug-eluting stent placement: Results from the premier registry. Circulation. 2006;113:2803. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.618066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jackevicius CA, Li P, Tu JV. Prevalence, predictors, and outcomes of primary nonadherence after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2008;117:1028–1036. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.706820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ho PM, Tsai TT, Wang TY, Shetterly SM, Clarke CL, Go AS, Sedrakyan A, Rumsfeld JS, Peterson ED, Magid DJ. Adverse events after stopping clopidogrel in post-acute coronary syndrome patients: Insights from a large integrated healthcare delivery system. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:303–308. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.890707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kiyota Y, Schneeweiss S, Glynn RJ, Cannuscio CC, Avorn J, Solomon DH. Accuracy of medicare claims-based diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction: Estimating positive predictive value on the basis of review of hospital records. Am Heart J. 2004;148:99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iezzoni LI, Heeren T, Foley SM, Daley J, Hughes J, Coffman GA. Chronic conditions and risk of in-hospital death. Health Serv Res. 1994;29:435–460. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wennberg JE, Skinner J, Goodman DC, Fisher E. Tracking the care of patients with chronic illness: The dartmouth atlas of health care 2008. Lebanon, NH: The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinberg BA, French WJ, Peterson E, Frederick PD, Cannon CP. Is coding for myocardial infarction more accurate now that coding descriptions have been clarified to distinguish st-elevation myocardial infarction from non-st elevation myocardial infarction? Am J Cardiol. 2008;102:513–517. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buresly K, Eisenberg MJ, Zhang X, Pilote L. Bleeding complications associated with combinations of aspirin, thienopyridine derivatives, and warfarin in elderly patients following acute myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:784–789. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.7.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.U.S. Census Bureau. [Accessed December 3, 2007];Census 2000, Summary File, American Fact Finder. http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/DTGeoSearchByListServlet?ds_name=DEC_2000_SF3_U&_lang=en&_ts=283785721496.

- 21.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS Manual System Pub. 100–18. [Accessed June, 1, 2010];Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit Manual. 2010 February 5; http://www.cms.gov/transmittals/downloads/R9PDB.pdf.

- 22.Association of American Medical Colleges. [Accessed December 12, 2009];Council of Teach Hospitals and Health Systems (COTH)

- 23.Goodman DC, Stukel TA, Chang CH, Wennberg JE. End-of-life care at academic medical centers: Implications for future workforce requirements. Health Aff (Millwood) 2006;25:521–531. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.2.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roe MT, Chen AY, Cannon CP, Rao S, Rumsfeld J, Magid DJ, Brindis R, Klein LW, Gibler WB, Ohman EM, Peterson ED on behalf of the CaA-GRP. Temporal changes in the use of drug-eluting stents for patients with non-st-segment-elevation myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention from 2006 to 2008: Results from the can rapid risk stratification of unstable angina patients supress adverse outcomes with early implementation of the acc/aha guidelines (crusade) and acute coronary treatment and intervention outcomes network-get with the guidelines (action-gwtg) registries. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2:414–420. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.850248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldman DP, Joyce GF, Escarce J, Pace JE, Solomon MD, Laouri M, Landsman PB, Teutsch SM. Pharmacy benefits and the use of drugs by the chronically ill. JAMA. 2004;129:2344–2350. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.19.2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guadagnoli E, Landrum MB, Peterson EA, Gahart MT, Ryan TJ, McNeil BJ. Appropriateness of coronary angiography after myocardial infarction among medicare beneficiaries. Managed care versus fee for service. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1460–1466. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011163432006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cutler DM, Everett W. Thinking outside the pillbox -- medication adherence as a priority for health care reform. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1553–1555. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1002305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grines CL, Bonow RO, Casey DE, Jr, Gardner TJ, Lockhart PB, Moliterno DJ, O’Gara P, Whitlow P. Prevention of premature discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery stents: A science advisory from the american heart association, american college of cardiology, society for cardiovascular angiography and interventions, american college of surgeons, and american dental association, with representation from the american college of physicians. Circulation. 2007;115:813–818. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.180944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:487–497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ganguli M, Du Y, Rodriguez E, Mulsant B, McMichael K, Vander Bilt J, Stoehr G, Dodge H. Discrepancies in information provided to primary care physicians by patients with and without dementia: The steel valley seniors survey. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:446–455. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000199340.17808.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stoehr G, Lu S, Lavery L, Bilt J, Saxton J, Chang C, Ganguli M. Factors associated with adherence to medication regimens in older primary care patients: The steel valley seniors survey. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2008;6:255–263. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schneeweiss S, Patrick AR, Pedan A, Varasteh L, Levin R, Liu N, Shrank WH. The effect of medicare part d coverage on drug use and cost sharing among seniors without prior drug benefits. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:w305–316. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.2.w305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sonel AF, Good CB, Mulgund J, Roe MT, Gibler WB, Smith SC, Jr, Cohen MG, Pollack CV, Jr, Ohman EM, Peterson ED for the CRUSADE Investigators. Racial variations in treatment and outcomes of black and white patients with high-risk non-st-elevation acute coronary syndromes: Insights from crusade (can rapid risk stratification of unstable angina patients suppress adverse outcomes with early implementation of the acc/aha guidelines?) Circulation. 2005;111:1225–1232. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000157732.03358.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Skinner J, Chandra A, Staiger D, Lee J, McClellan M. Mortality after acute myocardial infarction in hospitals that disproportionately treat black patients. Circulation. 2005;112:2634–2641. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.543231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jackevicius CA, Mamdani M, Tu JV. Adherence with statin therapy in elderly patients with and without acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2002;288:462–467. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.4.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Janz NK, Becker MH. The health belief model: A decade later. Health education quarterly. 1984;11:1. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ho PM, Bryson CL, Rumsfeld JS. Medication adherence. Circulation. 2009;119:3028–3035. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.768986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ho PM, Tsai TT, Maddox TM, Powers JD, Carroll NM, Jackevicius C, Go AS, Margolis KL, DeFor TA, Rumsfeld JS, Magid DJ. Delays in filling clopidogrel prescription after hospital discharge and adverse outcomes after drug-eluting stent implantation. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:261–266. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.902031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferreira-Gonzalez I, Marsal JR, Ribera A, Permanyer-Miralda G, Garcia-Del Blanco B, Marti G, Cascant P, Martin-Yuste V, Brugaletta S, Sabate M, Alfonso F, Capote ML, De La Torre JM, Ruiz-Lera M, Sanmiguel D, Cardenas M, Pujol B, Baz JA, Iniguez A, Trillo R, Gonzalez-Bejar O, Casanova J, Sanchez-Gila J, Garcia-Dorado D. Background, incidence, and predictors of antiplatelet therapy discontinuation during the first year after drug-eluting stent implantation. Circulation. 2010;122:1017–1025. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.938290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Song Y, Skinner J, Bynum J, Sutherland J, Wennberg JE, Fisher ES. Regional variations in diagnostic practices. N Eng J Med. 2010;363:45–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0910881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krumholz HM, Wang Y, Mattera JA, Wang Y, Han LF, Ingber MJ, Roman S, Normand S-LT. An administrative claims model suitable for profiling hospital performance based on 30-day mortality rates among patients with an acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2006;113:1683–1692. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.611186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tamblyn R, Lavoie G, Petrella L, Monette J. The use of prescription claims databases in pharmacoepidemiological research: The accuracy and comprehensiveness of the prescription claims database in quebec. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 1995;48:999–1009. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)00234-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grossberg R, Zhang Y, Gross R. A time-to-prescription-refill measure of antiretroviral adherence predicted changes in viral load in hiv. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2004;57:1107–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lau HS, de Boer A, Beuning KS, Porsius A. Validation of pharmacy records in drug exposure assessment. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:619–625. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00040-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weiden PJ, Kozma C, Grogg A, Locklear J. Partial compliance and risk of rehospitalization among california medicaid patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55:886–891. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.8.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baroletti S, Dell’Orfano H. Medication adherence in cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2010;121:1455–1458. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.904003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Neuman P, Strollo MK, Guterman S, Rogers WH, Li A, Rodday AMC, Safran DG. Medicare prescription drug benefit progress report: Findings from a 2006 national survey of seniors. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26:w630–643. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.5.w630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Part D Program Analysis. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Psaty BM, Siscovick DS. Minimizing bias due to confounding by indication in comparative effectiveness research: The importance of restriction. JAMA. 2010;304:897–898.125. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lin GA, Dudley RA, Lucas FL, Malenka DJ, Vittinghoff E, Redberg RF. Frequency of stress testing to document ischemia prior to elective percutaneous coronary intervention. JAMA. 2008;300:1765–1773. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.15.1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.King SB, III, Smith SC, Jr, Hirshfeld JW, Jr, Jacobs AK, Morrison DA, Williams DO, Feldman MTE, Kern MJ, O’Neill WW, Schaff HV, Whitlow PL, Adams CD, Anderson JL, Buller CE, Creager MA, Ettinger SM, Halperin JL, Hunt SA, Krumholz HM, Kushner FG, Lytle BW, Nishimura R, Page RL, Riegel B, Tarkington LG, Yancy CW Writing Committee. 2007 focused update of the acc/aha/scai 2005 guideline update for percutaneous coronary intervention: A report of the american college of cardiology/american heart association task force on practice guidelines: 2007 writing group to review new evidence and update the acc/aha/scai 2005 guideline update for percutaneous coronary intervention, writing on behalf of the 2005 writing committee. Circulation. 2008;117:261–295. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.188208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.