Summary

Microbial eukaryotes (nematodes, protists, fungi, etc., loosely referred to as meiofauna) are ubiquitous in marine sediments and likely play pivotal roles in maintaining ecosystem function. Although the deep-sea benthos represents one of the world’s largest habitats, we lack a firm understanding of the biodiversity and community interactions amongst meiobenthic organisms in this ecosystem. Within this vast environment key questions concerning the historical genetic structure of species remain a mystery, yet have profound implications for our understanding of global biodiversity and how we perceive and mitigate the impact of environmental change and anthropogenic disturbance. Using a metagenetic approach, we present an assessment of microbial eukaryote communities across depth (shallow water to abyssal) and ocean basins (deep-sea Pacific and Atlantic). Within the 12 sites examined, our results suggest that some taxa can maintain eurybathic ranges and cosmopolitan deep-sea distributions, but the majority of species appear to be regionally restricted. For OCTUs reporting wide distributions, there appears to be a taxonomic bias towards a small subset of taxa in most phyla; such bias may be driven by specific life history traits amongst these organisms. In addition, low genetic divergence between geographically disparate deep-sea sites suggests either a shorter coalescence time between deep-sea regions or slower rates of evolution across this vast oceanic ecosystem. While high-throughput studies allow for broad assessment of genetic patterns across microbial eukaryote communities, intragenomic variation in rRNA gene copies and the patchy coverage of reference databases currently present substantial challenges for robust taxonomic interpretations of eukaryotic datasets.

Keywords: microbial eukaryotes, meiofauna, deep-sea, cosmopolitan species, 18S rRNA, phylogeography, 454 sequencing

Introduction

The deep-sea benthos harbors vast numbers of eukaryotic meiofauna (organisms 38μm-1mm in size, such as nematodes, protists, fungi, etc.). Yet, there exists a well-recognized gap in the taxonomic understanding of their biodiversity. As a consequence, while we know that there are large numbers of individuals (50,000–5 million individuals per square meter (Vanhove et al. 1995; Danovaro et al. 2000)) from many different phyla (generally >15) in deep ocean sediments, we do not understand the general patterns of species-level distribution (cosmopolitan vs. local) for these communities. Knowledge of biogeographic patterns for these microscopic taxa directly impacts our understanding of global biotic diversity, and of the evolutionary mechanisms that shape their distribution. In addition, meiofaunal communities perform key ecosystem roles such as nutrient cycling and sediment stability in benthic marine habitats. Our continuing ignorance of species distributions and community structure in microbial eukaryote taxa currently precludes any informed mitigation and remediation of marine habitats in the wake of anthropogenic disturbance (e.g. oil spills).

The Baas-Becking hypothesis ‘everything is everywhere, but the environment selects’ (E is E) is among the most broadly discussed hypotheses for the biodiversity of small organisms (<2 mm) (Beijerinck 1918; Baas-Becking 1934; Finlay 2002; Fenchel and Finlay 2004; Kellogg and Griffin 2006). In this hypothesis small creatures with the potential for dispersal will have cosmopolitan distributions and will be found in common habitats with little or no evidence of historical constraints. Although this generalization has been challenged for some organismal groups (Lachance 2004; Foissner 2006; Telford et al. 2006; O’Malley 2007) it remains to be tested broadly across large numbers of meiofaunal taxa. Much of the argument pits traditional taxonomic assessment against molecular methods, where traditional approaches are viewed as ineffective at distinguishing closely related species, resulting in large-scale distributions of morphospecies (Todaro et al. 1996; Westheide and Schmidt 2003). The inherent nature of the E is E question requires intensive examination of phyla with severely underdeveloped taxonomies and an undescribed diversity so great that it would be unfathomable to surmount using traditional methods alone. Thus, molecular studies become the most viable option for assessing truly global patterns amongst meiofaunal communities. Limited genetic evidence has so far suggested contrasting patterns for meiofaunal phyla; some taxa appear to maintain broad, or even global species ranges (bdelloid rotifers, nematodes (Fontaneto et al. 2006; Derycke et al. 2008; Fontaneto et al. 2008)), while other evidence implies that geographic speciation may restrict microbial eukaryotes to specific regions or habitats (tardigrades, rotifers (Mills et al. 2007; Guil et al. 2009; Robeson et al. 2011)) However, the limited taxonomy of these small bodied, diverse phyla has limited traditional approaches and hindered large-scale assessments of their biogeographic patterns.

To address these questions we have applied a metagenetic approach (Sogin et al. 2006; Creer et al. 2010) to characterize the biodiversity of microbial eukaryote communities (typically, organisms that are retained on a 25–64μm sieve but pass through a 0.5mm mesh) across bathymetric gradients and oceanic basins. Here, we distinguish between the terms ‘meiofauna’ and ‘microbial eukaryotes’. Although sediment extraction protocols are typically biased towards the recovery of metazoan species (Creer et al. 2010), metagenetic studies additionally recover eukaryotic groups (fungi, protists, algae) not traditionally classified as meiofaunal taxa. This terminology thus reflects the broadened taxonomic coverage of high-throughput sequencing approaches. Two regions of the 18S rRNA gene (~400bps each) were independently sequenced from 12 environmental samples representing five deep-sea Pacific sites, five deep-sea Atlantic sties, and two shallow water sites: one in the Gulf of California and another in the Gulf of Mexico (Supp. Table S1).

Materials and Methods

Sample sites

A total of 12 samples were utilised in this study (Figure S2, Table S1B), representing ten deep-sea cores (5 Pacific sites and 5 Atlantic sites). Deep-sea samples were collected using a multicore; the top 0–5cm section was taken from one core tube of a multicorer deployment at each location. An approximately equal volume of sediment was collected from intertidal sample sites using a plexiglass coring tube. All sediment was immediately frozen upon collection. The meiofauna fraction of all samples was subsequently extracted according to standard protocols (Somerfield et al. 2005) for decantation and flotation in Ludox™ using a 45μm sieve.

DNA Extraction, PCR amplification and Sequencing

Per sample, environmental DNA was extracted from 200μl of sediment via bead beating using a Disruptor Genie (Zymo Research, Orange, CA). Two diagnostic regions of the 18S gene were amplified from environmental extracts using MID-tagged fusion primers SSU_F04/SSU_R22 (Blaxter et al. 1998) and NF1/18Sr2b (Porazinska et al. 2009). All reactions were carried out using 2μl of environmental genomic templates and the DyNAzyme EXT PCR kit (New England Biolabs) under the following reaction conditions: 95°C for 2 min followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 1 min, annealing at 50°C for 45 sec, extension at 72°C for 3 min, with a final extension of 72°C for 10 min. All PCR products were visualized on a 1.5% agarose gel containing Ethidium Bromide. Amplicons were purified using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (QIAGEN), and equimolar concentrations of all samples were submitted for sequencing. Sequencing was carried out on the GS FLX Titanium platform, returning a total of 1,316,988 sequence reads that averaged 350–450 bps in length; raw data has been deposited in Dryad (http://dryad.org) for public download.

Processing of Raw Pyrosequencing Reads

Raw sequence reads were processed and clustered using both the OCTUPUS pipeline (Fonseca et al. 2010; available at http://octupus.sourceforge.net/), and UCLUST within the QIIME toolkit (Caporaso et al. 2010). In each workflow, short reads (<200 bp) were eliminated and sequences were de-multiplexed and trimmed for quality; quality checks were carried using Lucy-trim (Chou and Holmes 2001) in OCTUPUS and split_libraries.py in QIIME, returning 1,258,077 and 969,343 processed sequence reads, respectively, across the 12 marine sites (Table S1A); Reads were subsequently separated into two datasets reflecting sequencing direction (forward-primer and reverse-primer datasets) containing both 18S gene regions. Forward and reverse sequence reads were independently seeded and clustered into Operational Clustered Taxonomic Units (OCTUs) using MegaBLAST (Zhang et al. 2000) in OCTUPUS and UCLUST in QIIME with a defined pairwise sequence identity cutoff value (95–99%). In OCTUPUS, MUSCLE alignments (Edgar 2004) were used to generate consensus sequences from each OCTU; in UCLUST, a representative sequence read was chosen to represent each clustered OCTU. Taxonomic assignments were generated for the final list of OCTU consensus/representative sequences, using MegaBLAST to retrieve the top scoring hit existing in GenBank as of May 2011. OCTU sequences that did not return any significant hits (<90% sequence identity) were labelled as ‘no match’. Chimeric OCTUs were identified using the chimera.pl script in OCTUPUS, and the Blast Fragments approach (identify_chimeric_seqs.py in QIIME) for UCLUST data.

Statistical Analyses of OCTUs

Base error rates for OCTU clustering in OCTUPUS were calculated according to the proportion of OCTUs containing obviously mis-assigned MID-tag reads; estimates were very low, ranging from 0.015–0.026% of total sequence reads. Baseline error rates were further used as a cutoff to eliminate OCTUs with potentially erroneous MID-tag assignments and eliminate incorrect geographic inferences in OCTUPUS; the number of OCTUs falling below baseline error estimates ranged from 0.07–1.94% of total OCTUs per dataset. OCTUs that showed a high identity to human DNA or common lab contaminants were eliminated from datasets. Putatively chimeric sequences were both removed and included in analyses in order to assess biodiversity patterns under varying degrees of stringency; removal of chimeras did not effect the inferred biogeographic patterns in sequence datasets. Taxonomic proportions were calculated using forward sequence reads, excluding all flagged chimeras; proportional changes across datasets were assessed using a two-tailed Z-test for proportion (n=2). Phylogeographic comparisons were conducted using ‘well-sampled’ OCTUs, defined as those which contained a minimum number of sequence reads per cluster (with a cutoff set at 3 Standard Deviations below the mean); for 95% clustered datasets, this ‘well-sampled’ cutoff was defined as OCTUs containing ≥47reads in OCTUPUS data and ≥40 reads in UCLUST data, while for 99% clustered datasets the defined cutoff was OCTUs containing ≥2 reads in OCTUPUS and ≥4 reads in UCLUST. This subset of OCTUs was used as a statistically defined estimate of regionally restricted versus putatively cosmopolitan taxa (Table 2) amongst marine eukaryotes.

Table 2. Distribution of OCTUs across depth gradients and ocean basins using both relaxed (95%) and stringent (99%) pairwise sequence identity cutoffs.

Proportions calculated from a subset of ‘well-sampled’ OCTUs (statistically defined; see materials and methods) representing forward sequence reads from both 18S gene regions. Eurybathic taxa are defined as those OCTUs spanning large depth gradients (deep-sea to intertidal habitats), while cosmopolitan deep-sea taxa represent OCTUs present in both Pacific and Atlantic ocean basins.

| Intertidal and Deep-sea OCTUs | Deep-sea OCTUs | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stenobathic taxa | Eurybathic taxa | Restricted Taxa | Cosmopolitan Taxa | |||||

| OCTU clustering | UCLUST | OCTUPUS | UCLUST | OCTUPUS | UCLUST | OCTUPUS | UCLUST | OCTUPUS |

| 95% identity | 80.12% | 62.21% | 19.88% | 37.79% | 54.24% | 24.71% | 45.76% | 75.29% |

| 99% identity | 98.6% | 98.5% | 1.4% | 1.5% | 88.67% | 90.92% | 11.33% | 9.08% |

Phylogenetic and Diversity Analyses

Phylogenetic community analyses were conducted using the Fast UniFrac online toolkit (http://bmf2.colorado.edu/fastunifrac)(Hamady et al. 2010). Consensus OCTU sequences (representing both diagnostic regions of the 18S gene) were aligned to curated 18S structural alignments using the SINA aligner available on the SILVA rRNA database (http://www.arb-silva.de). Relaxed Neighbor-Joining trees were subsequently constructed using the ARB software suite (Ludwig et al. 2004) and Clearcut program available within the Xplor program (Frank 2008). Principle Coordinate Analyses and Jackknifed cluster analyses were run using both weighted (using normalized abundance values for sequences reads per OCTU) and unweighted (no abundance information) datasets; default sequence counts and a range of bootstrap permutations (100–1000) were used to calculate Jackknife replicates. Observed biogeographic patterns were concordant across all UniFrac tools and parameters. A subset of OCTUs (those containing >10 sequence reads) whose assigned taxonomy was denoted as “Environmental” or “No Match” was manually examined in NJ tree topologies; the phylogenetic placement of these sequences was as a basis for subsequent taxonomic inferences.

Rarefaction curves were estimated using the parallel_multiple_rarefaction.py script in the QIIME pipeline. Prior to calculation of alpha diversity, high quality, trimmed sequence reads were clustered via UCLUST (99% similarity cutoff), with no separation of forward and reverse sequence reads. Rarefaction curves were calculated by subsampling the resulting OCTUs, with pseudoreplicate datasets containing between 10 and 20682 OTU sequences (in steps of 2067) with 10 repetitions performed per pseudoreplicate.

Results

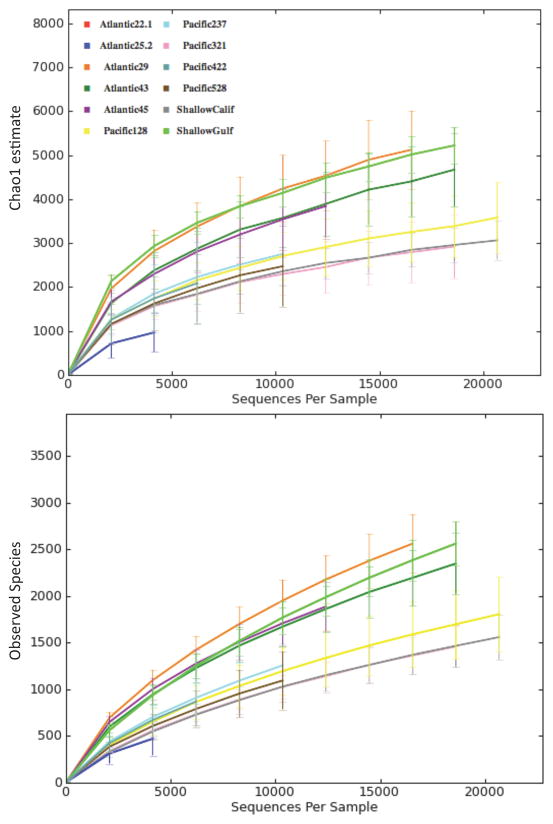

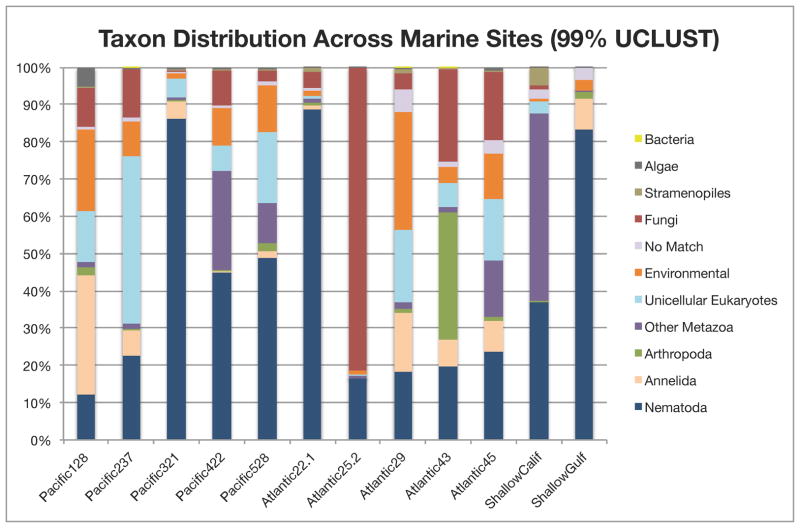

Environmental amplicons from 12 marine sites were pooled and sequenced on a full plate run of the GS FLX Titanium platform (Roche), returning ~1.3 million raw sequence reads. The highest quality reads were assigned to operationally clustered taxonomic units (OCTUs) using pairwise distance-based clustering in multiple computational pipelines (UCLUST and OCTUPUS); in each toolkit, clustering was repeatedly carried out under a range of sequence identity values (95–99%). A subset of reads (the F04/R22 locus from Atlantic sties 22#1 and 25#2) were subjected to stringent denoising in AmpliconNoise followed by Perseus (Quince et al. 2011); denoising pipelines were found to be too computationally intensive to run on the full 454 dataset. Empirical evidence suggests that 95% clustering tends to lump closely related biological species and genera, while 99% clustering effectively splits species into multiple OCTUs representing dominant and minor 18S variant sequences within individual species (Porazinska et al. 2010); thus, we focused on investigating biological patterns using these two parameters (‘relaxed’ clustering at 95% and ‘stringent’ clustering at 99%) as representing extreme ends of the clustering spectrum. Taxonomic assignments for each OCTU were derived from the top-scoring BLAST match (exhibiting >90% pairwise identity) recovered in public sequence databases. All analyses, including denoised datasets, recovered a diversity of eukaryotic taxa and suggested high levels of species richness across the marine samples analyzed. Denoising dramatically reduced the number of OCTUs (Table 1) but did not impact taxonomic inferences for the subset of sites analysed; the identities of abundant taxa were consistent irrespective of denoising. Similar taxonomic information was recovered from independently sequenced 18S gene regions (Table S2), illustrating the broad taxonomic coverage obtainable with conserved metazoan 18S primers. Our protocols were able to recover a substantial number of unicellular eukaryotes and 25 metazoan phyla (Table S2), including two of the most recently discovered and enigmatic lineages: Gnathostomulida and Loricifera (Littlewood et al. 1998; Sorensen et al. 2008). Despite this seemingly comprehensive coverage, it is likely that experimental biases (loss of taxa during sediment processing, failed primer binding) inherently prevented the recovery of all eukaryotic taxa present in marine samples. Rarefaction curves (Chao1 and Observed Species metrics, Figure 1) indicate that eukaryotic diversity was not exhaustively characterized, despite a deep sequencing effort across sample locations. Taxonomic proportions recovered at each sample site (Figure 2) further reveal a high variability in eukaryotic community assemblages, regardless of habitat; this variability is also supported by denoised data (Figure S1)

Table 1. Effect of denoising on OTU number.

Denoising raw reads in AmpliconNoise followed by Perseus (Quince et al. 2011) caused a dramatic reduction in OTU number from similar numbers of starting reads. Data collated from non-chimeric reads clustered at 99% in respective pipelines; OTU count derived from clusters containing reads originating from the indicated primer.

| SSU_F04 | SSU_R22 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AmpNoise | UCLUST | OCTUPUS | AmpNoise | UCLUST | OCTUPUS | ||

| Atlantic22#1 | OTUs | 128 | 293 | 573 | 97 | 135 | 542 |

| Reads | 1403 | 1371 | 2077 | 688 | 601 | 2407 | |

| Atlantic25#2 | OTUs | 219 | 1257 | 2778 | 229 | 814 | 1821 |

| Reads | 10502 | 12969 | 15177 | 11253 | 11851 | 14789 | |

Figure 1. Rarefaction Curves compiled using Chao1 estimation (top) and observed species counts (bottom).

All high-quality sequence reads (>200bps) clustered with UCLUST (99% similarity cutoff) prior to calculation of alpha diversity.

Figure 2. Eukaryotic community assemblages present across marine sites.

Taxonomic assemblages inferred from non-chimeric OCTUs recovered from UCLUST analysis at a 99% pairwise similarity cutoff; similar proportions were reported for all sites under relaxed 95% clustering.

A notable portion of OCTUs (~10%) recovered no significant match (sequence identity <90%) to known ribosomal sequences. Although these taxa potentially represent novel eukaryotic lineages, the failure to recover a close sequence match likely reflects taxonomic gaps in public databases (Berney et al. 2004). To explore this phenomenon further, we manually investigated the phylogenetic placement of ‘Environmental’ and ‘No Match’ OCTUs (containing >10 raw sequence reads in forward-read datasets clustered at 99% identity) within Neighbour-Joining tree topologies. All examined sequences display similarity to taxa within known eukaryotic groups, although our focused analysis suggests that many of these OCTUs represent deep lineages in known phyla. Out of 986 unknown OCTUs examined, the majority (67.8%) represented unicellular eukaryotes, while the remaining OCTUs were assigned as nematodes (12.2%), algae (7.8%), stramenopiles (6.8%), fungi (3.7%), or other metazoa (1.7%). Very few unknown OCTUs grouped within the Arthropoda (0.5%), or Annelida (0.1%), suggesting that 18S data for these groups is relatively robust compared to other taxa.

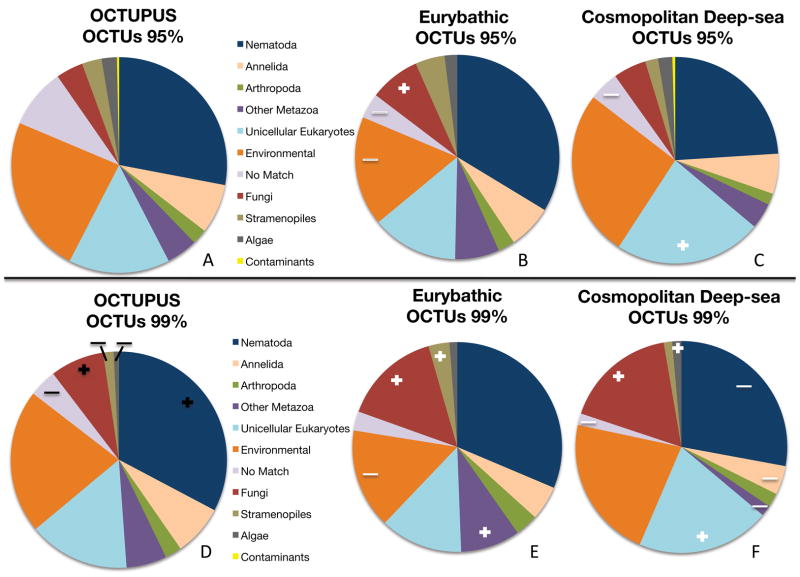

Statistically-defined cutoffs (see materials and methods) were used to extract ‘well-sampled’ OCTUs and infer patterns of species distributions. At both stringent (99%) and relaxed (95%) clustering values, a subset of OCTUs appear to have cosmopolitan distributions spanning disparate geographic locales (present in both deep-sea Pacific and Atlantic sites, Table 2) or large depth gradients (present in intertidal and deep-sea sediments, Table 2). The proportion of these putatively cosmopolitan and eurybathic taxa drops dramatically with increasing clustering stringency; under relaxed clustering (95% sequence identity) in the OCTUPUS pipeline 75% of OCTUs were recovered as cosmopolitan and 37% appeared eurybathic, while these proportions drop to 9.08% and 1.5%, respectively, in stringently clustered datasets (Table 2). Similar patterns were evident after independent OTU clustering in UCLUST (Table 2). These results confirm cosmopolitan distributions amongst meiofaunal eukaryotes, although it appears to be the exception rather than the rule for marine taxa. Under the most stringent clustering parameters, the number of putatively eurybathic OCTUs is six to eight-fold lower than cosmopolitan deep-sea OCTUs; this distinct separation of deep-sea and shallow water taxa may reflect the significant physical differences between these two habitats—most taxa probably lack the physiological adaptations required to surmount large bathymetric gradients. Conversely, the deep-sea environment is largely stable, perhaps allowing increased survival rates and encouraging long-distance dispersal across a physically homogenous habitat.

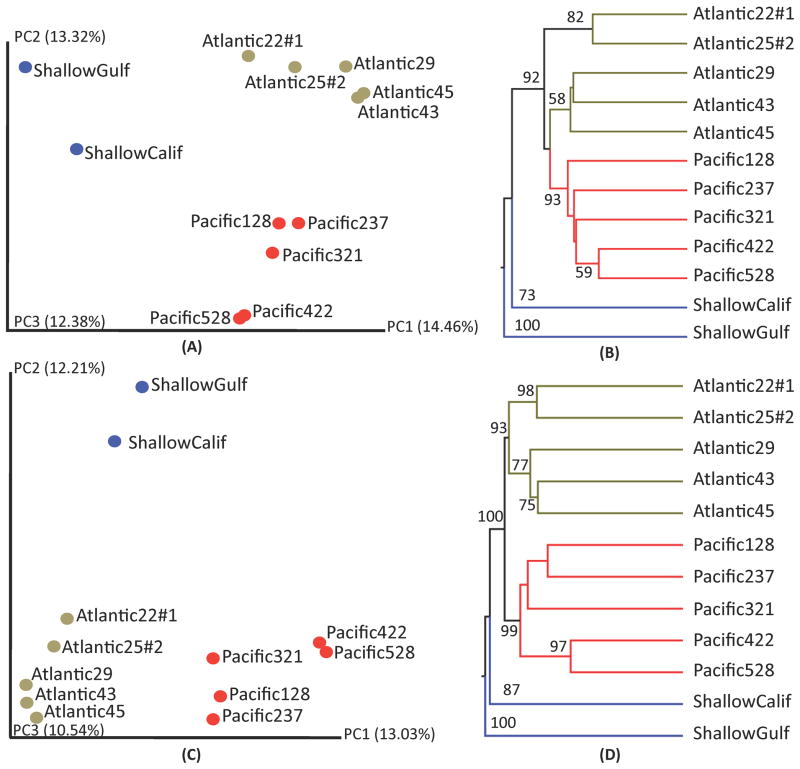

In a phylogenetic analysis of community structure, Principle Coordinate Analyses (Figure 3A, 3C) and Jackknifed Clustering Analyses (Figure 3B, 3D) further supported a distinction between intertidal and deep-water sample sites as well as a notable separation of deep-sea Pacific and Atlantic sites; the same patterns were observed for OCTUs clustered using both stringent (99%) and relaxed (95%) pairwise identity cutoffs. In phylogenetic diversity analyses, deep-sea sites showed a higher degree of similarity in eukaryotic community structure, although there is an overall separation between Atlantic and Pacific Ocean basins. Since the present study included a limited number of intertidal sampling sites (2 locations), we further incorporated an expanded dataset including Fonseca et al.’s (2010) SSU pyrosequencing data (homologous to Region 1 in this study) from nine additional intertidal sites along the UK coastline. In this independent analysis, the observed geographic patterns remained consistent and we additionally recovered the same clustering patterns amongst UK sites as reported in the Fonseca et al. study (Figure S2).

Figure 3. Results of phylogenetic community analyses using the Fast Unifrac toolkit (Hamady et al. 2010).

Data represents forward sequencing reads from Region 1 of the 18S gene. Principle Coordinate analysis of OCTUs clustered using a 95% (A) and 99% (C) pairwise identity cutoff in the OCTUPUS pipeline. Jackknifed Cluster Analysis of OCTUs clustered at 95% (B) and 99% (D); colors represent geographic origin, and support values >50% are reported.

Discussion

Biogeographic patterns in benthic marine eukaryotes

Although the literature is peppered with attempts to address “Everything is Everywhere”, the hypothesis itself remains virtually untestable. The globally exhaustive sampling strategy and concurrent sampling depth required to determine if E is E for microbial eukaryotes is fundamentally prohibitive. Nevertheless, the explosion of high-throughput sequencing methods now enables us—for the first time—to test broad scale patterns of species distributions and community assemblages for these understudied taxa. In marine habitats, there is ample evidence to suggest that depth gradients limit species distributions (Howell et al. 2002; Aldea et al. 2008) seemingly far more than geographic distance (Pawlowski et al. 2007). Although our sample set was limited to 12 sites, our phylogenetically-informative analyses overwhelmingly supported a distinct separation of shallow water and deep-sea communities; despite the additional inclusion of relatively proximate shallow water sites (Littlehampton and Prestwick, UK), eukaryotic communities at deep-sea Atlantic sites strongly cluster with deep-sea Pacific sites located ~9000 kilometers away (95% bootstrap, Figure S3). Furthermore, geographic proximity did not always correlate with similar deep-sea community structures. Pacific sites 422 and 528 had similar community assemblages (Figure 2) and exhibited a close association in Jackknife cluster analyses (>99.9% support in Figure 3D) despite being separated by ~400km and 1000m in depth; Pacific site 321 and 422 are physically closer (only ~36km apart), yet show different taxon abundances (Figure 2) and are distinctly separated in both Jackknife cluster analysis and PCoA. These observations were concordant across both 18S gene regions, and suggest a complex pattern of species distributions at smaller scales in the deep-sea.

The assigned taxonomic identities of OCTUs suggest an inherent bias amongst microbial eukaryotes displaying cosmopolitan and eurybathic distributions. Such bias was evident regardless of clustering methods applied to raw data, although clustering method appeared to have some effect on the reported taxonomies of eurybathic and cosmopolitan deep-sea OTU subsets. In OCTUPUS and UCLUST, fungal OCTUs consistently account for a significantly larger proportion of putatively eurybathic and cosmopolitan deep-sea OCTUs (Figure 4 and Figure S4; Z-test, p < 0.003 in all datasets), implying that fungal species may be particularly adept at dispersing in marine environments. In UCLUST, unicellular eukaryotes always represented a smaller proportion of ubiquitous taxa (Z-test, p < 0.005 in all datasets) compared to the full environmental dataset (Figure S4B, S4E), although these taxa appeared to show increased dominance amongst cosmopolitan deep-sea OCTUs (Z-test, p < 0.000 amongst cosmopolitan taxa at 95% and 99%). These observations may reflect differences in the two computational approaches; the process of OTU clustering is not well understood for eukaryote taxa with pervasive intragenomic rRNA variation, and thus our biological interpretations of high-throughput data may be easily skewed without extensive investigation of such dubious patterns (e.g. by tracking OTU membership via raw sequence reads). Overall proportions OCTUs from UCLUST datasets generally corresponded to the taxonomic distributions observed in OCTUPUS data at both 95% and 99% clustering cutoff (Figure 4A, 4D and Figure S4A, S4D). Amongst cosmopolitan taxa, a striking taxonomic bias was observed within the Phylum Nematoda (Figure S5) where the order Enoplida was the sole group to show a significant proportional increase under both stringent and relaxed clustering in OCTUPUS (Z-tests, p=0.008 at 95%, p=0.000 at 99%), constituting 85% of cosmopolitan nematode OCTUs under the most stringent parameters (99% clustering). These observed taxonomic biases amongst cosmopolitan taxa may reflect specific life history traits; many unicellular eukaryotes are known to produce dispersive propagule stages (Alve and Goldstein 2003), and recent evidence suggests mechanisms for long-distance dispersal in Enoplid nematodes (Bik et al. 2010).

Figure 4. Proportions of eukaryotic taxa recovered under relaxed (95%) and stringent (99%) clustering in the OCTUPUS pipeline.

Proportions calculated from non-chimeric OCTUs representing forward sequencing reads from both 18S gene regions. Only significant proportional increases (+) and decreases (−) are outlined across datasets; Black symbols represent changes observed between differential clustering of non-chimeric sequence reads at 95% (A) versus 99% (D) cutoffs. White symbols represent proportional changes between all non-chimeric OCTUs and subsets of OCTUs with observed eurybathic (B, E) and cosmopolitan (C, F) distributions.

Exploring OCTU clustering in the context of geography offers substantial insight into the relationship between shallow and deepwater eukaryote communities. In comparisons of datasets clustered under different parameters (stringent vs. relaxed pairwise cutoffs), deep-sea species inhabiting Pacific and Atlantic sites show lower overall genetic divergence, versus taxa found across depth gradients (shallow to deep) where genetic divergence appears more pronounced. Half to three-quarters of deep-sea OCTUs are recovered as ‘cosmopolitan’ taxa using a relaxed 95% cutoff, whereby OCTUs contain sequences representing both Pacific and Atlantic locations; however, under stringent clustering parameters, the majority of OCTUs (88–90%) contain sequence reads from only one ocean basin (Table 2). This implies that within phyla, many closely related (but geographically isolated) deep-sea taxa show less than 5% divergence in rRNA genes. Increasing the maximum pairwise identity cutoff to 99% during OCTU clustering discourages lumping of reads and returns many regionally restricted OCTUs that may reflect a more accurate picture of biological species distributions. In contrast, a significant genetic divergence is apparent across bathymetric gradients; the number of ‘eurybathic’ taxa (OCTUs containing raw reads isolated from both shallow water and deep-sea sites) is low even under relaxed parameters (19–37% of OCTUs clustered at 95% identity) and drops to a minute subset of taxa (~1.5%) under stringent clustering parameters (Table 2). These patterns suggest that sister taxa in shallow water habitats exhibit a larger divergence in rRNA loci (>5%), and this reduces lumping of OCTUs under relaxed clustering. The lower pairwise distance amongst deep-sea OCTUs is further supported by full-length 18S sequence data from Enoplid nematodes (Bik et al. 2010); while nematodes exhibited consistent, deep divergences between shallow water and deep-sea clades, the internal structure of deep-sea groups showed no correlation with geography. These observations support an overall lower genetic divergence across deep-sea communities. These patterns may be indicative of a relatively recent geographic isolation between many microbial eukaryote taxa, with a shorter coalescence time between closely related deep-sea species compared to their shallow water counterparts. The extreme conditions and static nature of deep-sea habitats could also plausibly lead to slower rates of evolution in meiofaunal rRNA genes—a scenario that could provide an alternative explanation for the observed results.

Linking community patterns to habitat

Metagenetic methods offer much promise for gaining deep insight into diverse (and historically understudied) benthic communities in marine environments. In addition to piecing together global biogeographic patterns for microbial eukaryote species, the relative abundance of taxa can offer powerful insight. Although the average proportions of taxa were consistent when all samples were pooled (e.g. total OCTUs in OCTUPUS and UCLUST clustering, Figures 4 and S4), a fine-scale resolution becomes apparent when the eukaryotic community structure is examined at individual sample sites. In taxonomic studies, nematodes are often cited as the most abundant members of sediment communities (Lambshead 2004), but our deep sequencing results suggest an equal or more dominant role for other taxonomic groups at some sites. Recent high-throughput studies have uncovered similar hidden abundances (Platyhelmithes, (Fonseca et al. 2010) ), likely reflecting historical artefacts from traditional preservation methods. In our results, many sites exhibited lower relative abundances of nematodes and specific dominance of other taxonomic groups (e.g. Unicellular Eukaryotes at Pacific237, Platyhelminthes at the Shallow California site; Figure 2). It is presently unclear whether these patterns represent stochastic variation, or correlate with biological assemblages or specific habitat characteristics. Deep-sea Atlantic samples were collected from submarine canyon ecosystems off the Iberian margin; previous evidence suggests that continual disturbance in canyons results in lower species richness in nematodes, with dominance of predatory and scavenging genera (Ingels et al. 2009). Our results from canyon sediments reported a lower number of sequence reads equating to fewer OCTUs (Atlantic 22.1 and 25.2; Figure 2, Table S1A), an increased dominance of fungal taxa (Atlantic sites 25.2, 43, 45; Figure 2), and many predatory nematode taxa amongst the most abundant OCTUs at Atlantic sites. These observations may be indicative of increased physical disturbance in these canyon habitats compared to Pacific deep-sea locations, although further work is needed to fully characterize these preliminary insights.

Regardless of habitat, microbial eukaryote communities appear to be extremely complex and diverse across marine habitats. Rarefaction curves did not reach asymptote at any site (despite our deep sampling effort), suggesting a substantial amount of undiscovered biodiversity. Understanding ecological interactions through taxon presence/absence, relative abundance data, and phylogenetic lineages is the ultimate goal of high-throughput studies. However, there currently no robust bioinformatic pipelines for teasing out subtle associations between habitat metadata and high-throughput sequence data. Developing tools to provide more detailed taxonomic insight and a deeper exploration of community diversity analysis (e.g. within QIIME (Caporaso et al. 2010)) is an active, and exciting, area of research. Future high-throughput studies will additionally need to adopt a more detailed sampling regime (e.g. intensive assessment at multiple spatial scales) to clarify the scale and extent of community variation across marine ecosystems.

Deriving accurate taxonomy

Assigning accurate taxonomy to eukaryotic OCTUs is inherently more difficult than popular approaches utilized in bacterial studies. While there are a number of alignment-based tools in existence which utilize secondary structure information for classification (Greengenes and RDP classifier, both implemented in QIIME (Caporaso et al. 2010)), these are currently restricted to bacterial and archaeal taxa; thus, utilizing pairwise identity scores (via BLAST) is currently the most informatically feasible option for large eukaryotic rRNA datasets. For eukaryotes, BLAST-derived taxonomy can provide a robust overview of communities at higher taxonomic levels, but such assignments data should generally be treated with caution. Our approach required a minimum pairwise identity score >90% for OCTUs to receive a taxonomic assignment from BLAST searches. The relative paucity of eukaryotic sequence data in public databases (versus known taxonomic diversity) results in many OCTUs displaying no significant hit, or the recovery of top BLAST matches with very low sequence identity (often below 95%); thus, many OCTU assignments can only be trusted down to phylum level, at best. “Environmental” OCTUs or those with no sufficient BLAST match represented nearly a quarter of clusters at under both stringent and relaxed clustering parameters (Figures 4 and S4). Aligning these sequences and manually importing them into a SILVA reference phylogeny can confirm the biological reality and taxonomic identity of these OCTUs; however, interpreting OCTU data in such an evolutionary context is labor intensive, with no automated approaches currently in existence for high-throughput eukaryotic data. Database modifications can also significantly impact analyses—for example, the increase in ‘environmental’ hits in denoised datasets (Figure S1, versus prior UCLUST analysis in Figure 2) likely stems from new depositions in GenBank, and adds a frustrating layer of ambiguity when attempting subsequent comparisons. Furthermore, even if OCTUs exhibit high BLAST scores to classified sequences, the hierarchical NCBI taxonomy and user-submitted annotation cannot always be trusted as accurate. Manual examination of BLAST results and subsequent phylogenetic examination of OCTUs reveals the presence of Acoela and Nemertodermatida (two groups of early-branching bilaterians) in our marine dataset. Accepting the assigned phylum-level NCBI taxonomy currently lumps these flat worms into the Platyhelminthes and ignores their distinct evolutionary origins (Hejnol et al. 2009; Mwinyi et al. 2010; Philippe et al. 2011), potentially hindering ecological inferences from high-throughput datasets. Because of these persistent issues, interpreting taxonomy within a phylogenetic framework will be critical for future studies.

Conclusions

Although our sampling scheme was biased and not globally intensive, the included variables have produced exciting insight into global distributions of microbial eukaryotes. OCTUs cannot necessarily be reconciled with biological species; lower cutoffs are known to lump taxonomic genera or even orders together, while the most stringent cutoffs (e.g. 99%) can substantially oversplit well-established species (Porazinska et al. 2010). Despite this proviso, a subset of eurybathic and cosmopolitan taxa were consistently recovered across a range of OCTU clustering parameters (95–99% identity in UCLUST and OCTUPUS) and these patterns withstood stringent, statistically-determined filtering measures. Although each OTU may not represent a separate species, the surprising consistency of biogeographic patterns must correlate (at least to some degree) with true biological species. High-throughput environmental datasets are often plagued by sequence chimeras (PCR artefacts) generated during initial gene amplification; in clustered metagenetic datasets, it is thought that these chimeras tend to appear as sample-specific OCTUs (e.g. restricted to single PCR reactions) containing relatively low numbers of sequence reads. This fact, coupled with our stringent pruning of putatively chimeric OTU sequences, means that chimeras cannot be used to discount the cosmopolitan and eurybathic distributions we observed in a subset of meiofaunal taxa. In addition, the cladogram of marine sites (Figure 3B,3D) was inferred on the basis of phylogenetic lineages shared between geographic locations (thus, non-chimeric OCTUs); these striking patterns would not be recovered if PCR artefacts were substantially impacting our analyses. These results strongly support cosmopolitan distributions for some microbial eukaryotes in marine habitats.

Finally, we acknowledge the taxonomic bias which may have been imposed during our extraction protocols; although the use of a 45um sieve is established practice for meiofauna studies, mesh pores are still relatively wide and may favor the recovery of larger species or life stages, particularly in finer deep-sea sediments. Despite this methodological bias, our interpretation of cosmopolitanism is not obviously skewed—organisms with both small and large body sizes were recovered within our subsets of cosmopolitan and eurybathic taxa (Figure 4). High-throughput studies are only now scratching the surface of global eukaryotic biodiversity; biogeographic patterns recovered in this study are essentially preliminary insights into an emerging field of research. As more locations are scrutinized and sequencing effort becomes increasingly deeper with newer technology, a focus on metadata and sophisticated computational tools will allow us to develop an organic understanding of marine ecosystems.

Supplementary Material

Table S1: Sample metadata and distribution of sequence reads across 12 marine sites. Table S1A: Number of raw reads obtained after independent quality checks and filtering in the QIIME and OCTUPUS pipelines. Table S1B: Corresponding metadata for each marine site analysed, including sediment type, collection date, GPS coordinates and depth information.

Table S2: Taxonomic Breakdown of all OCTUs recovered at 95% and 99% sequence identity cutoffs in the OCTUPUS pipeline, based on top-scoring BLAST matches obtained from two 18S gene regions. Comparable taxonomic diversities were observed in both independently analyzed gene regions. OCTUs denoted as ‘no match’ did not recover any significant BLAST hits (exhibiting <90% pairwise sequence identity to sequences in public databases); contaminant OTUs (Human and common lab contaminants) removed from dataset.

Figure S1: Eukaryotic community assemblages at Atlantic sites 22#1 and 25#2 following noise removal. Taxonomic assemblages inferred from raw pyrosequencing data denoised in AmpliconNoise followed by Perseus (Quince et al. 2011); proportions calculated from non-chimeric OCTUs recovered after clustering in OCTUPUS analysis at a 99% pairwise similarity cutoff.

Figure S2: Map displaying sample sites utilized in this study, representing Pacific (blue) and Atlantic (red) locations. Solid circles represent deep-sea sites, while torus shapes reflect shallow-water locations.

Figure S3: Jackknife Cluster Analysis using an expanded SSU pyrosequencing dataset. OCTUs represent Region 1 of SSU gene, clustered at 95% in the OCTUPUS pipeline. OCTU dataset was compiled using pooled raw data (forward and reverse reads) from the present study and published data obtained from Fonseca et al. (Fonseca et al. 2010).

Figure S4: Proportions of eukaryotic taxa recovered under relaxed (95%) and stringent (99%) clustering with UCLUST. Proportions calculated from non-chimeric OCTUs representing forward sequencing reads from both 18S gene regions. Only significant proportional increases (+) and decreases (−) are outlined across datasets; Black symbols represent changes observed between differential clustering of non-chimeric sequence reads at 95% (A) versus 99% (D) cutoffs. White symbols represent proportional changes between all non-chimeric OCTUs and subsets of OCTUs with observed eurybathic (B, E) and cosmopolitan (C, F) distributions.

Figure S5: Proportional changes observed for non-chimeric nematode OCTUs (BLAST-derived taxonomy) representing forward sequencing reads from both 18S loci. Significant proportional increases (+) and decreases (−) are denoted. Black symbols represent changes in taxonomic membership observed between clustering of non-chimeric sequence reads at 95% (A) versus 99% (D) cutoffs. Brown symbols represent proportional changes between all non-chimeric nematode OCTUs and subsets of nematode OCTUs with observed eurybathic (B, E) and cosmopolitan (C, F) distributions.

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Thistle (NSF grant OCE-0727243), V. Huvenne, T.J. Pereira and L. Hyde for collecting sediment cores. This work was supported by NSF (DEB 0228962 and DEB 0315829) and NIH (NIH-1P20RR030360-01)

Footnotes

Data Accessibility

Raw 454 reads and processed OTU data: DRYAD entry doi:10.5061/dryad.qm8f3

References

- Aldea C, Olabarria C, Troncoso JSS. Bathymetric zonation and diversity gradient of gastropods and bivalves in West Antarctica from the South Shetland Islands to the Bellingshausen Sea. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers. 2008;55(3):350–368. [Google Scholar]

- Alve E, Goldstein ST. Propagule transport as a key method of dispersal in benthic foraminifera (Protista) Limnology and Oceanography. 2003;48:2163–2170. [Google Scholar]

- Baas-Becking LGM. Geobiologie of inleiding tot de milieukunde. The Hague, The Netherlands: W.P. van Stockum and Zoon; 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Beijerinck M. De Infusies en de ontdekking der Backterien. Muller, Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Jaarboek van de Koninklijke Akademie v. Wetenschappen; 1918. [Google Scholar]

- Berney C, Fahrni J, Pawlowski J. How many novel eukaryotic ‘kingdoms’? Pitfalls and limitations of environmental DNA surveys. BMC Biology. 2004;2:13. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-2-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bik HM, Thomas WK, Lunt DH, Lambshead PJD. Low endemism, continued deep-shallow interchanges, and evidence for cosmopolitan distributions in free-living marine nematodes (order Enoplida) BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2010;10:389. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-10-389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaxter ML, De Ley P, Garey JR, Liu LX, Scheldeman P, et al. A molecular evolutionary framework for the phylum Nematoda. Nature. 1998;392:71–75. doi: 10.1038/32160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nature Methods. 2010;7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou H, Holmes M. DNA sequence quality trimming and vector removal. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:1092–1104. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.12.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creer S, Fonseca VG, Porazinska DL, Giblin-Davidson G, Sung W, et al. Ultra sequencing of the meiofaunal biosphere: Practice, pitfalls and promises. Molecular Ecology. 2010;19(Suppl 1):4–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danovaro R, Tselepides A, Otegui A, Della Croce N. Dynamics of meiofaunal assemblages on the continental shelf and deep-sea sediments of the Cretan Sea (NE Mediterranean): relationships with seasonal changes in food supply. Progress in Oceanography. 2000;46:367–400. [Google Scholar]

- Derycke S, Remerie T, Backeljau T, Vierstraete A, Vanfleteren J, et al. Phylogeography of the Rhabditis (Pellioditis) marina species complex: evidence for long-distance dispersal, and for range expansions and restricted gene flow in the northeast Atlantic. Molecular Ecology. 2008;17:3306–3322. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Research. 2004;32(5):1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenchel T, Finlay BJ. The ubiquity of small species: patterns of local and global diversity. BioScience. 2004;54:777–784. [Google Scholar]

- Finlay BJ. Global diversity of free-living microbial eukaryote species. Science. 2002;296:1061–1063. doi: 10.1126/science.1070710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foissner W. Biogeography and dispersal of microorganisms: a review emphasizing protists. Acta Protozoologica. 2006;45:111–136. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca VG, Carvalho GR, Sung W, Johnson HF, Power DM, et al. Second-generation environmental sequencing unmasks marine metazoan biodiversity. Nature Communications. 2010;1(98) doi: 10.1038/ncomms1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontaneto D, Barraclough TG, Chen K, Ricci C, Herniou EA. Molecular evidence for broad-scale distributions in bdelloid rotifers: everything is not everywhere but most things are widespread. Molecular Ecology. 2008;17:3136–3146. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontaneto D, Ficetola GF, Ambrosini R, Ricci C. Patterns of diversity in microscopic animals: are they comparable to those in protists or larger animals? Global Ecology and Biogeography. 2006;15:153–162. [Google Scholar]

- Frank DN. XplorSeq: A software environment for integrated management and phylogenetic analysis of metagenomic sequence data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:420. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guil N, Sánchez-Moreno S, Machordom A. Local biodiversity patterns in micrometazoans: Are tardigrades everywhere? Systematics and Biodiversity. 2009;7(3):259–268. [Google Scholar]

- Hamady M, Lozupone C, Knight R. Fast UniFrac: facilitating high-throughput phylogenetic analyses of microbial communities including analysis of pyrosequening and PhyloChip data. The ISME Journal. 2010;4:17–27. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2009.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hejnol A, Obst M, Stamatakis A, Ott M, Rouse GW, et al. Assessing the root of bilaterian animals with scalable phylogenomic methods. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B. 2009;276(1677):4261–4270. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.0896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell KL, Billet DSM, Tyler PA. Depth-related distribution and abundance of seastars (Echinodermata: Asteroidea) in the Porcupine Seabight and Porcupine Abyssal Plain, N.E. Atlantic. Deep-sea Research I. 2002;49:1901–1920. [Google Scholar]

- Ingels J, Kiriakoulakis K, Wolff GA, Vanreusel A. Nematode diversity and its relation to the quanitity and quality of sedimentary organic matter in the deep Nazare Canyon, Western Iberian Margin. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers. 2009;56:1529–1539. [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg CA, Griffin DW. Aerobiology and the global transport of desert dust. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 2006;21:638–644. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachance M-A. Here and there or everywhere? Bioscience. 2004;54(10):884–885. [Google Scholar]

- Lambshead PJD. In: Marine Nematode Biodiversity. Nematology: Advances and Perspectives. Chen ZX, Chen SY, Dickson DW, editors. Vol. 1. Wallingford: CABI Publishing; 2004. pp. 439–468. [Google Scholar]

- Littlewood DTJ, Telford MJ, Clough KA, Rohde K. Gnathostomulida--An enigmatic metazoan phylum from both morphological and molecuar perspectives. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 1998;9(1):72–79. doi: 10.1006/mpev.1997.0448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig W, Strunk O, Westram R, Richter L, Meier H, et al. ARB: a software environment for sequence data. Nucleic Acids Research. 2004;32(4):1363–1371. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills S, Lunt DH, Gomez A. Global isolation by distance despite strong regional phylogeography in a small metazoan. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2007;7:225. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mwinyi A, Bailly X, Bourlat SJ, Jondelius U, Littlewood DTJ, et al. The phylogenetic position of Acoela as revealed by the complete mitochondrial genome of Symsagittifera roscoffensis. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2010;10:309. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-10-309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley MA. The nineteenth century roots of ‘everything is everywhere’. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2007;5:647–651. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlowski J, Fahrni J, Lecroq B, Longet D, Cornelius N, et al. Bipolar gene flow in deep-sea benthic foraminifera. Molecular Ecology. 2007;16:4089–4096. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippe H, Brinkmann H, Copley RR, Moroz LL, Nakano H, et al. Acoelomorph flatworms are deuterostomes related to Xenoturbella. Nature. 2011;470(7333):255–258. doi: 10.1038/nature09676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porazinska DL, Giblin-Davis RM, Faller L, Farmerie W, Kanzaki N, et al. Evaulating high-throughput sequencing as a method for metagenomic analysis of nematode diversity. Molecular Ecology Resources. 2009;9(6):1439–1450. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2009.02611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porazinska DL, Giblin-Davis RM, Sung W, Thomas WK. Linking operational clustered taxonomic units (OCTUs) from parallel ultra sequencing (PUS) to nematode species. Zootaxa. 2010;2427:55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Quince C, Lanzen A, Davenport RJ, Turnbaugh PJ. Removing noise from pyrosequenced amplicons. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:38. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robeson MS, King AJ, Freeman KR, Birky CW, Jr, Martin AP, et al. Soil rotifer communities are extremely diverse globally but spatially autocorrelated locally. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science USA. 2011;108(11):4406–4410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012678108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sogin ML, Morrison HG, Huber JA, Welch DM, Huse SM, et al. Microbial diversity in the deep sea and the unexplored “rare biosphere”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science USA. 2006;103(32):12115–12120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605127103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somerfield PJ, Warwick RM, Moens M. In: Meiofauna Techniques. Methods for the Study of Marine Benthos. 3. Eleftheriou A, McIntyre A, editors. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2005. pp. 229–272. [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen MV, Hebsgaard MB, Heiner I, Glenner H, Willerslev E, et al. New data from an enigmatic phylum: evidence from molecular sequence data supports a sister-group relationship between Loricifera and Nematomorpha. Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research. 2008;46(3):231–239. [Google Scholar]

- Telford RJ, Vandvik V, Birks HJB. Dispersal limitations matter for microbial morphospecies. Science. 2006;312:1015. doi: 10.1126/science.1125669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todaro MA, Fleeger JW, Hu YP, Hrincevich AW, Foltz DW. Are meiofaunal species cosmopolitan? Morphological and molecular evidence of Xenotrichula intermedia (Gastrotricha: Chaetonotida) Marine Biology. 1996;125:735–742. [Google Scholar]

- Vanhove S, Wittoeck J, Desmet G, Van den Berghe B, Herman RL, et al. Deep-sea meiofauna communities in Antarctica: structural analysis and relation with the environment. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 1995;127:65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Westheide W, Schmidt H. Cosmopolitan versus cryptic meiofaunal polychaete species: an approach to molecular taxonomy. Helgoland Marine Research. 2003;57:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZN, Schwartz S, Wagner L, Miller W. A greedy algorithm for aligning DNA sequences. Journal of Computational Biology. 2000;7(1–2):203–214. doi: 10.1089/10665270050081478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1: Sample metadata and distribution of sequence reads across 12 marine sites. Table S1A: Number of raw reads obtained after independent quality checks and filtering in the QIIME and OCTUPUS pipelines. Table S1B: Corresponding metadata for each marine site analysed, including sediment type, collection date, GPS coordinates and depth information.

Table S2: Taxonomic Breakdown of all OCTUs recovered at 95% and 99% sequence identity cutoffs in the OCTUPUS pipeline, based on top-scoring BLAST matches obtained from two 18S gene regions. Comparable taxonomic diversities were observed in both independently analyzed gene regions. OCTUs denoted as ‘no match’ did not recover any significant BLAST hits (exhibiting <90% pairwise sequence identity to sequences in public databases); contaminant OTUs (Human and common lab contaminants) removed from dataset.

Figure S1: Eukaryotic community assemblages at Atlantic sites 22#1 and 25#2 following noise removal. Taxonomic assemblages inferred from raw pyrosequencing data denoised in AmpliconNoise followed by Perseus (Quince et al. 2011); proportions calculated from non-chimeric OCTUs recovered after clustering in OCTUPUS analysis at a 99% pairwise similarity cutoff.

Figure S2: Map displaying sample sites utilized in this study, representing Pacific (blue) and Atlantic (red) locations. Solid circles represent deep-sea sites, while torus shapes reflect shallow-water locations.

Figure S3: Jackknife Cluster Analysis using an expanded SSU pyrosequencing dataset. OCTUs represent Region 1 of SSU gene, clustered at 95% in the OCTUPUS pipeline. OCTU dataset was compiled using pooled raw data (forward and reverse reads) from the present study and published data obtained from Fonseca et al. (Fonseca et al. 2010).

Figure S4: Proportions of eukaryotic taxa recovered under relaxed (95%) and stringent (99%) clustering with UCLUST. Proportions calculated from non-chimeric OCTUs representing forward sequencing reads from both 18S gene regions. Only significant proportional increases (+) and decreases (−) are outlined across datasets; Black symbols represent changes observed between differential clustering of non-chimeric sequence reads at 95% (A) versus 99% (D) cutoffs. White symbols represent proportional changes between all non-chimeric OCTUs and subsets of OCTUs with observed eurybathic (B, E) and cosmopolitan (C, F) distributions.

Figure S5: Proportional changes observed for non-chimeric nematode OCTUs (BLAST-derived taxonomy) representing forward sequencing reads from both 18S loci. Significant proportional increases (+) and decreases (−) are denoted. Black symbols represent changes in taxonomic membership observed between clustering of non-chimeric sequence reads at 95% (A) versus 99% (D) cutoffs. Brown symbols represent proportional changes between all non-chimeric nematode OCTUs and subsets of nematode OCTUs with observed eurybathic (B, E) and cosmopolitan (C, F) distributions.