Abstract

Progression of activated EGF receptor (EGFR) through the endocytic pathway regulates EGFR signaling. Here we show that a non-ubiquitinated EGFR mutant, unable to bind the endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) component, Hrs, is not efficiently targeted onto intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) of multivesicular endosomes/bodies (MVBs). Moreover, ubiquitination and ESCRT engagement of activated EGFR is required for EGF-stimulated ILV formation. Non-ubiquitinated EGFRs enter clathrin-coated tubules emanating from MVBs and show enhanced recycling to the plasma membrane, compared to wild type EGFR.

Keywords: EGF receptor, multivesicular bodies, intralumenal vesicles, recycling, ubiquitination

INTRODUCTION

Stimulation of the EGFR with EGF promotes receptor dimerization, autophosphorylation and protein tyrosine kinase activity. Activated EGFRs provide sites for recruitment of signaling proteins, triggering signal cascades involved in diverse cellular processes including proliferation, migration and survival (1). Activated EGFRs undergo rapid clathrin-mediated endocytosis; the EGFR kinase remains active following internalization, indeed endocytosis is required for full activation of some signaling molecules (2). Internalised receptors are sorted onto recycling or degradative pathways. Recycling receptors, such as the transferrin receptor, are retained on the limiting membrane of the MVB and returned to the plasma membrane (3). Lysosomally targeted receptors, like activated EGFR, are sorted onto the ILVs of MVBs for subsequent lysosomal degradation (4). We have shown that EGF stimulation drives sorting of EGFR onto ILVs, but also promotes ILV formation by a mechanism that depends on EGF-stimulated phosphorylation of annexin 1 (5). Sequestration of activated EGFRs onto ILVs, renders the active EGFR kinase inaccessible to cytoplasmic substrates, thereby attenuating signal transduction (6). EGFR progression through the endocytic pathway is therefore critical for the maintenance of tightly regulated receptor kinase signaling, disregulation of which has been implicated in tumour development (7).

Progression of EGFR through the endocytic pathway is regulated by phosphorylation/dephosphorylation and ubiquitination/deubiquitination of both the EGFR itself and sorting machinery constituents. Ubiquitination of activated EGFR by the E3 ubiquitin ligase, Cbl (8), allows the receptor to engage the ESCRT machinery. ESCRT 0-III protein complexes are thought to function sequentially in both the targeting of membrane proteins onto, and the formation of, MVB ILVs (9). The role of the ESCRT machinery in ILV formation has been considerably elucidated through in vitro studies using purified ESCRT components (9, 10), but the role of the ESCRT machinery in EGF-stimulated ILV formation has been more difficult to establish. Depletion of components of the ESCRT machinery, whilst inhibiting EGF-stimulated ILV formation, also profoundly affects the morphology and function of the endocytic pathway (11, 12), and indeed has effects not directly related to endosomal sorting. Mutation of lysine residues that function as ubiquitin conjugation sites in the EGFR kinase domain results in a mutant EGFR (15KR) that is negligibly ubiquitinated (13). Expression of 15KR-EGFR enables the role of EGFR-ubiquitination, and thereby ESCRT engagement by EGFR, to be determined whilst leaving both the ESCRT machinery and EGFR signaling intact. Furthermore this mutant EGFR allows the role of ubiquitination of the EGFR it self to be distinguished from that of ubiquitination of sorting machinery components. EGFR ubiquitination is not required for its internalization, since 15KR EGFR was internalized at a similar rate to that of wild-type receptor (wtEGFR), but is important for its efficient lysosomal targeting since 15KR-EGFR degradation is severely impaired (13). Here we examine the fate of internalized 15KR EGFR and the role of EGFR ubiquitination in its sorting onto ILVs, and in EGF-stimulated ILV formation.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

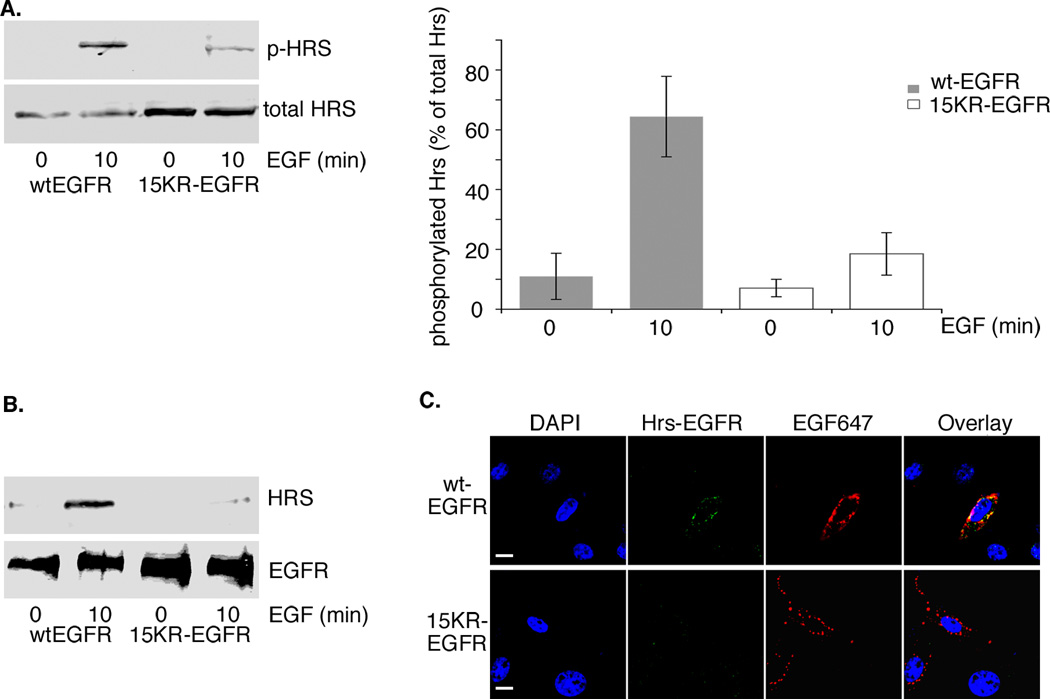

Disrupted engagement of the ESCRT machinery by 15KR-EGFR

Ubiquitinated EGFR interacts with the ubiquitin binding domains of the ESCRT0 complex Hrs/STAM, which canals obephosphorylated by the EGFR. To determine whether EGFR ubiquitination is required for efficient Hrs phosphorylation we examined phosphorylation of Hrs, by activated human wild-type and 15KR-EGFR stably expressed in porcine aortic endothelial (PAE) cells, that lack endogenous EGFR. Little or no phosphorylated Hrs could be detected in serum-starved wild-type or 15KR-EGFR cells (Figure 1A). On stimulation with EGF, there was a marked increase in phosphorylated Hrs in wtEGFR cells and a much smaller increase (>3 fold less) in 15KR-EGFR cells (Figure 1a). It is possible that Hrs can be phosphorylated to a minor extent by EGFR with out stable interaction with the ESCRT machinery, so to measure ESCRT engagement more directly we examined the ability of 15KR-EGFR to interact with Hrs, by co-immunoprecipitation. Little or no Hrs was detected in EGFR immunoprecipitates from serum-starved wild-type or 15KR-EGFR cells or from EGF-stimulated 15KR-EGFR cells (Figure 1B). Indeed less Hrs, as a percentage of EGFR, was immunoprecipitated from EGF-stimulated 15KR-EGFR cells than from serum-starved wtEGFR cells (less than 2% and 5% respectively). In contrast, more than 20 fold more Hrs was present in EGFR immunoprecipitates from EGF-stimulated wtEGFR cells (Figure 1B). Moreover, using a fluorescence-based proximity ligation immunoassay to detect protein-protein interactions in cells stimulated with fluorescent EGF to mark EGFR expression, we observed strong fluorescence signal indicating an interaction between EGFR and Hrs, in wtEGFR cells, and only background fluorescence, comparable with that in non-expressing cells, in 15KR-EGFR cells (Figure 1C). Taken together these data indicate that the interaction between 15KR-EGFR and Hrs is severely impaired and suggest a much reduced ability of the 15KR-EGFR to engage the ESCRT machinery. The low level of EGF-stimulated Hrs phosphorylation in cells expressing 15KR-EGFR (approximately four-fold less than wtEGFR) may be due to the proximity of activated internalised 15KR-EGFR to Hrs on early endosomes, or to phosphorylation by another EGF-stimulated kinase.

Figure 1.

15KR-EGFR fails to engage the ESCRT machinery. wtEGFR or 15KR-EGFR cells were stimulated with EGF as indicated.

A. Cell extracts were immunoblotted with anti-Hrs antibody (total Hrs) or with antibody specifically recognizing Hrs phosphorylated at tyrosine 334 (p-Hrs). Phosphorylated Hrs expressed as a percentage of total Hrs is shown as means ± s.d. for 3 experiments.

B. EGFR immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted with anti-Hrs or anti-EGFR antibodies. C. Cells stably expressing wtEGFR or 15KR-EGFR were stimulated for 10 min at 37°C with fluorescent-EGF (red) and stained for EGFR-Hrs interaction (green) using the DuolinkII assay. Fluorescent signal indicating an interaction (green) was clearly visible in cells expressing wtEGFR (red) and largely colocalised with EGF (yellow) but was absent from cells expressing 15KR-EGFR (red). Scale bars, 10µm. Activated wtEGFR phosphorylates Hrs much more efficiently than 15KR-EGFR and Hrs co-immunoprecipitates with activated wild-type but not 15KR-EGFR.

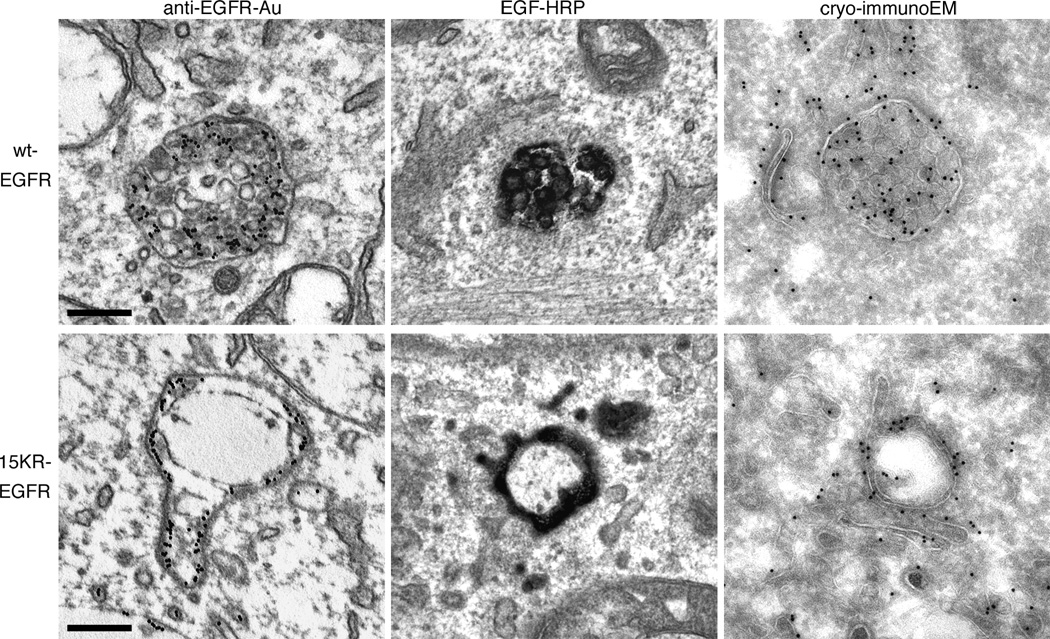

15KR EGFR is not efficiently targeted to ILVs and is unable to promote EGF-stimulated ILV formation

Progress through the endocytic pathway of human wild-type and 15KR-EGFR was followed by electron microscopy (EM). EGFR was visualized by internalised anti-EGFR-gold (30 min) or EGF-HRP (3h), or by cryoimmuno-EM on ultrathin frozen sections of cells stimulated with EGF (1h). At each time point, wtEGFR was efficiently targeted to the ILVs of MVBs (Figure 2). In contrast, even after prolonged incubation with EGF, 15KR-EGFR present within MVBs localized primarily to the limiting membrane (Figure 2). Thus, in the presence of unperturbed ESCRT machinery, EGFR ubiquitination is required for EGFR to accumulate on ILVs. This could be because ubiquitination of EGFR is required for its targeting to ILVs or is required to promote the formation of ILVs, a process we have previously shown to be stimulated by EGF.

Figure 2. 15KR-EGFR is not efficiently targeted to the ILVs of MVBs.

wtEGFR or 15KR-EGFR cells were stimulated with EGF in the presence of anti-EGFR antibody-gold conjugate for 1h at 37°C (anti-EGFR-Au), or EGF-HRP for 3h at 37°C. Cells prepared for cryo-immunoEM were stimulated with EGF for 30 min at 37°C and ultrathin frozen sections were labeled for EGFR. Scale bar, 200 nm. EGFR is efficiently targeted to the ILVs of MVBs in cells expressing wt-EGFR but is localised to the limiting membrane of MVBs in cells expressing 15KR-EGFR.

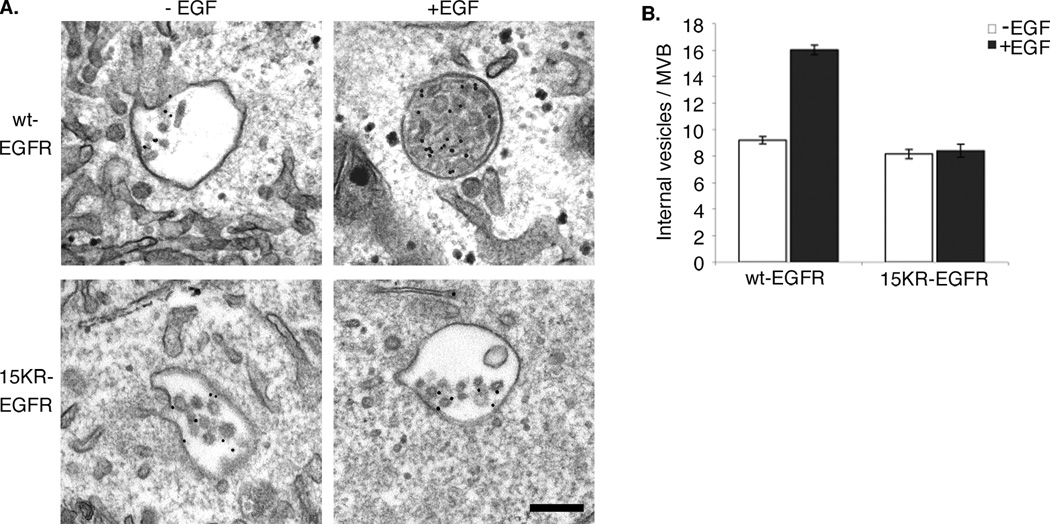

To determine whether 15KR-EGFR can support EGF-stimulated ILV formation, the cells were incubated with BSA-gold in the presence or absence of EGF. In serum-starved cells, ILV numbers were similar in wild-type and 15KR-expressing cells, but on stimulation with EGF for 1h, ILV numbers almost doubled in cells expressing wtEGFR, but remained virtually unchanged in the 15KR-EGFR cells (Figure 3). These data reveal a critical role for EGFR ubiquitination in EGF-stimulated ILV formation. We have previously shown that, in addition to the ESCRT machinery(11), this process requires tyrosine phosphorylation of annexin 1(5) and the activity of the protein tyrosine phosphatase, PTP1B(14), which dephosphorylates both the EGFR and ESCRT components. Taken together with the demonstration here of the role of EGFR ubiquitination in this process, these data suggest that EGFR ubiquitination and subsequent engagement of ESCRTs, in combination with phosphorylation/dephosphorylation of non-ESCRT and ESCRT components act to upregulate ILV formation in EGF-stimulated cells. The data in Figs. 2 and 3 also suggest that cargo-ESCRT interactions and formation of ILVs are two functionally and mechanistically coupled processes.

Figure 3. 15KR-EGFR is unable to promote EGF-stimulated inward vesiculation.

A. wtEGFR or 15KR-EGFR cells were incubated with BSA-gold conjugate in the absence (−EGF) or presence (+EGF) of EGF for 1h at 37°C. Scale bar, 200nm.

B. The number of ILVs per BSA-gold containing MVB was counted; results are means ±s.d. for three experiments. ILV numbers almost double on stimulation with EGF in cells expressing wild type EGFR but remain unchanged in cells expressing 15KR-EGFR.

Small numbers of 15KR-EGFRs were observed on ILVs in the current study. This could occur due to residual ubiquitination of the 15KR mutant that is not detectable by western blotting and mass-spectrometry, via ubiquitin- and ESCRT-independent mechanisms(15–17) or could be the result of constitutive (basal) incorporation of transmembrane cargo present at the perimeter membrane of the MVB, into ILVs.

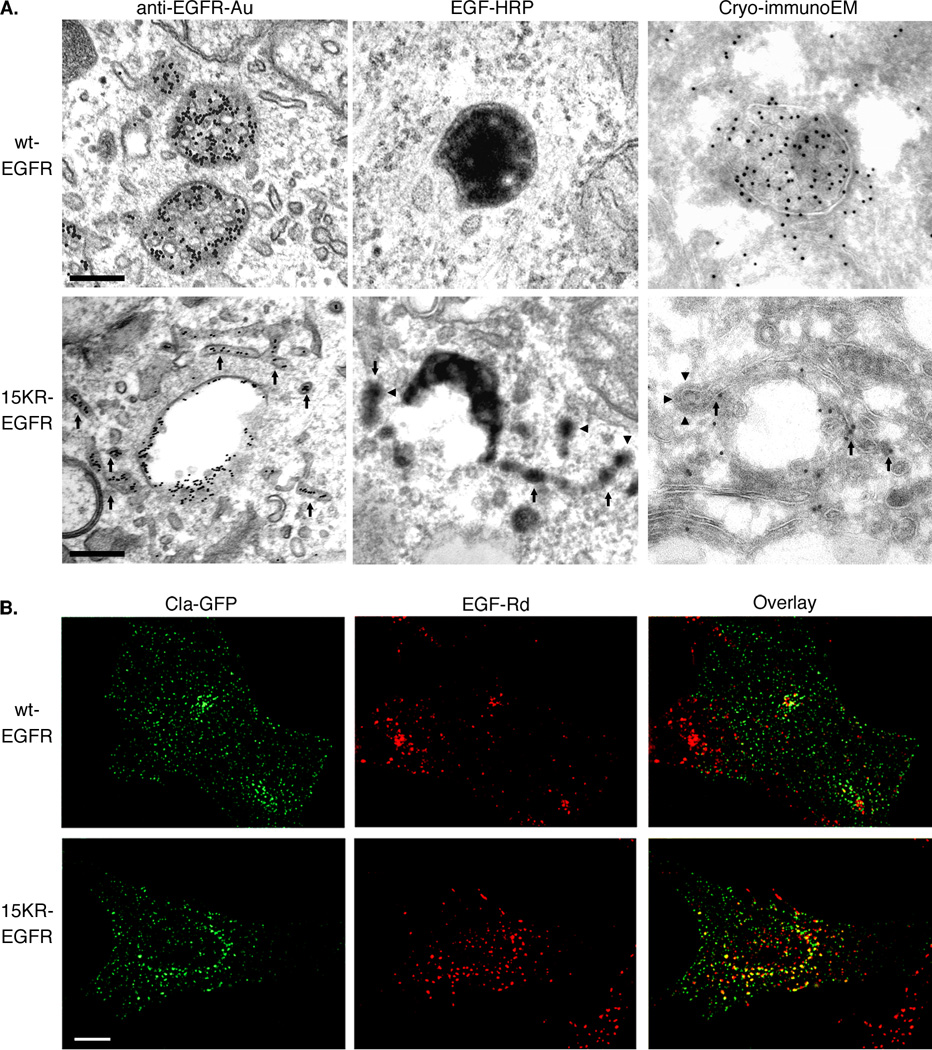

15KR EGFR recycling from endosomes to the plasma membrane is enhanced

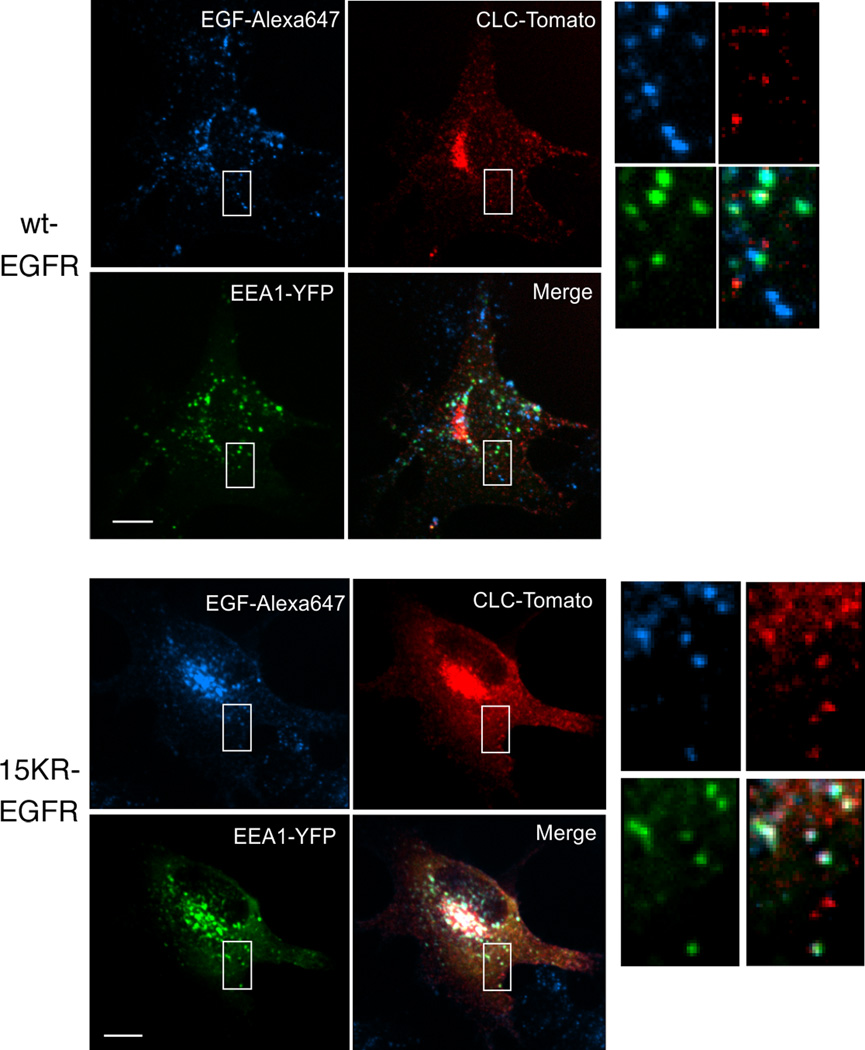

We next analyzed the fate of the 15KR EGFR that failed to be sorted onto ILVs to determine whether it is retained on the perimeter membrane of the MVB or recycled. Receptor recycling occurs either rapidly direct to the plasma membrane from sorting endosomes (18) or via a less rapid pericentriolar tubulovesicular recycling compartment (19). Two pathways of recycling that differ in rate have also been described for the EGFR (20). Ultrastructural localization of EGFR revealed that whereas the vast majority of wtEGFR staining decorated the ILVs of MVBs, 15KR-EGFR localized not only to the perimeter membrane of MVBs but also to tubular extensions of MVBs, many of which bear buds that appeared to be coated with clathrin (Figure 4A). A recycling pathway to the plasma membrane via clathrin-coated vesicles that bud from endosomes has been described for transferrin (21–23). To further examine the presence of clathrin on 15KR-EGFR-positive structures, cells expressing wild-type or 15KR-EGFR were transfected with clathrin light chain conjugated to GFP (Cla-GFP) and incubated with EGF-Rhodamine conjugate (EGF-Rh) for 1 hr. While very little colocalisation between EGF and clathrin in endosomal compartments was observed in cells expressing wtEGFR, this was markedly increased in cells expressing 15KR-EGFR (Figure 4B). More detailed analysis of EGFR- and clathrin-containing endosomes using co-expression of clathrin tagged with Tomato fluorescent protein and YFP-labeled Rab11, EEA.1 or Rab7 revealed significant co-localization of EGF-Alexa647 and Cla-Tomato only with EEA.1 in cells expressing 15KR-EGFR (Figure 5), suggesting that these are early endosomes. Significantly larger pool of EGF-Alexa647 remained in early endosomes after 1 hr of continuous endocytosis in 15KR-EGFR expressing cells (42% ± 5% of total cell-associated EGF-Alexa647) than in wtEGFR expressing cells (25% ± 4%).

Figure 4. 15KR-EGFR is found on tubular extensions and colocalises with clathrin.

A. wtEGFR or 15KR-EGFR cells were stimulated with EGF in the presence of anti-EGFR antibody-gold conjugate (anti-EGFR-Au) for 1h at 37°C or EGF-HRP for 3h at 37°C. Cells prepared for cryo-immunoEM were stimulated with EGF for 30 min at 37°C and ultrathin frozen sections were labelled for EGFR. Arrows indicate staining on tubular extensions which in some areas appear clathrin coated (arrowheads). Scale bar, 200nm.

B. Cells expressing wtEGFR or 15KR-EGFR were transfected with Clathrin-GFP (Cla-GFP) and incubated with EGF-Rhodamine (EGF-Rd) for 1h at 37°C. Individual optical sections through the middle of the cells of representative deconvoluted 3-D images are shown. Colocalisation (yellow) between clathrin (green) and EGF (red) is increased in cells expressing 15KR-EGFR compared with wtEGFR. Scale bars, 10µm.

Figure 5. 15KR-EGFR colocalises with clathrin and EEA.1.

Cells expressing wtEGFR or 15KR-EGFR were transfected with clathrin light chain-Tomato fluorescent protein (Cla-Tomato) and YFP-tagged EEA.1. After 2 days the cells are incubated with EGF-Alexa647 conjugate (20ng/ml) for 1h at 37°C. Individual confocal sections through the middle of the cells of representative 3-D images are shown. Insets show high magnification images of the regions indicated by white rectangles. Colocalisation (white) between clathrin (red), EEA.1(green) and EGF (blue) is increased in cells expressing 15KR-EGFR compared with wtEGFR. Also, note a significantly lesser co-localization of EGF-Alexa 647 and EEA. 1 in wtEGFR (25%±4%; S.E.M) than K15R expressing cells (42%±5%; S.E.M.), due to a faster sorting of wtEGFR to late endosomes. No significant co-localization of Cla-Tomato with YFP-Rab7 and YFP-Rab11 was observed (data not shown). Scale bars, 10µm.

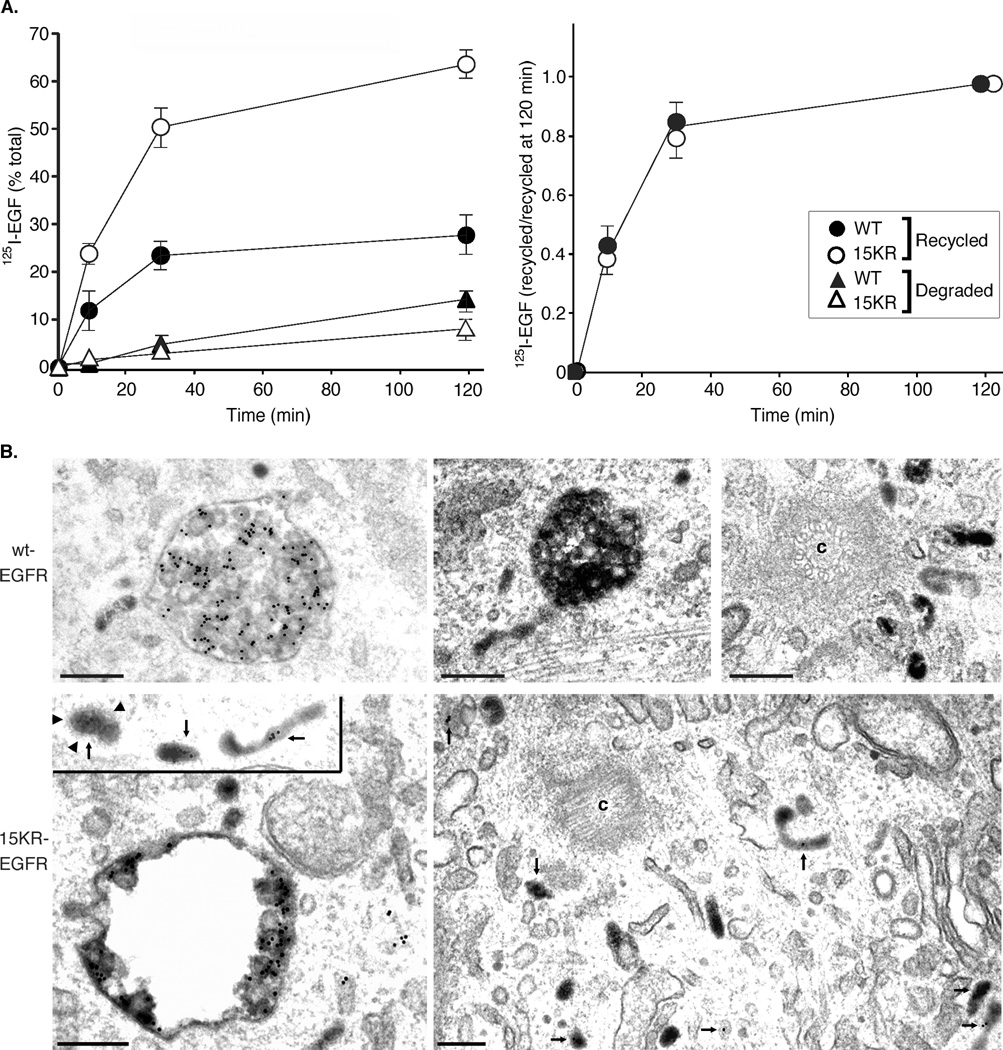

15KR-EGFR’s localization to tubular structures associated with MVBs and its intracellular colocalisation with clathrin suggests that, rather than being retained on the perimeter membrane of the MVB, 15KR-EGFR enters recycling tubules. We therefore compared the recycling rates of radiolabelled EGF in cells expressing wild-type or 15KR-EGFR by monitoring the release of intact 125I-EGF into the medium of cells loaded with 125I-EGF at time points from 0–120 min of a 37°C chase. The amount of internalized 125I-EGF recycled to the cell surface and detected in the medium by 15KR-EGFR was double that of wtEGFR, reaching approximately 60% by 30 min compared with less than 30% at the same time point in wtEGFR cells (Figure 6A). Conversely, the amount of degraded 125I-EGF was lower in 15KR-EGFR cells, although 125I-EGF degradation to low molecular weight products is slow in PAE cells as the majority of 125I-EGF remains partially degraded in lysosomes in these cells; the two-fold difference in 125I-EGF degradation between wild-type and 15KR-EGFR cells only became apparent after long chase incubations (Figure 6A). EGF receptor degradation occurs rapidly within a 2hr chase in wtEGFR cells but is severely impaired in 15KR cells (Huang et al, 2007 and Figure 7). Interestingly, the rate of EGF-receptor complex recycling (expressed as the amount of recycled 125I-EGF normalized to the maximal amount of recycled 125I-EGF) was similar for wtEGFR and 15KR (Figure 6A), suggesting that the difference between these two cell lines is in the relative size of the pool of internalized EGFRs capable of recycling rather than in the mechanisms/pathways of recycling. These data show that the 15KR EGFR is not efficiently retained in MVBs but is recycled and contrasts with the fate of the G-protein-coupled δ-opioid receptor which, in the absence of receptor ubiquitination, shows reduced accumulation on ILVs but is still removed from the recycling pathway by retention in MVBs and delivered to lysosomes (24).

Figure 6. Increased recycling of 15KR-EGFR: EGF complexes.

A. 125I-EGF recycling and degradation was measured in wtEGFR or 15KR-EGFR cells and presented as percent of total radioactivity associated with cells and medium at each time point (left chart), or as the ratio of recycled 125I-EGF at each time point to the maximum amount of recycled 125I-EGF at time point “120 min” (right chart). Results are means ±s.d. from 3 experiments.

B. wtEGFR or 15KR-EGFR cells were stimulated with EGF in the presence of Tf-HRP and anti-EGFR antibody-gold conjugate for 1h at 37°C. Arrows indicate transferrin and EGFR co-staining on tubules, sometimes near the centriole (c) and sometimes clathrin coated (arrowheads). Scale bar, 200nm.

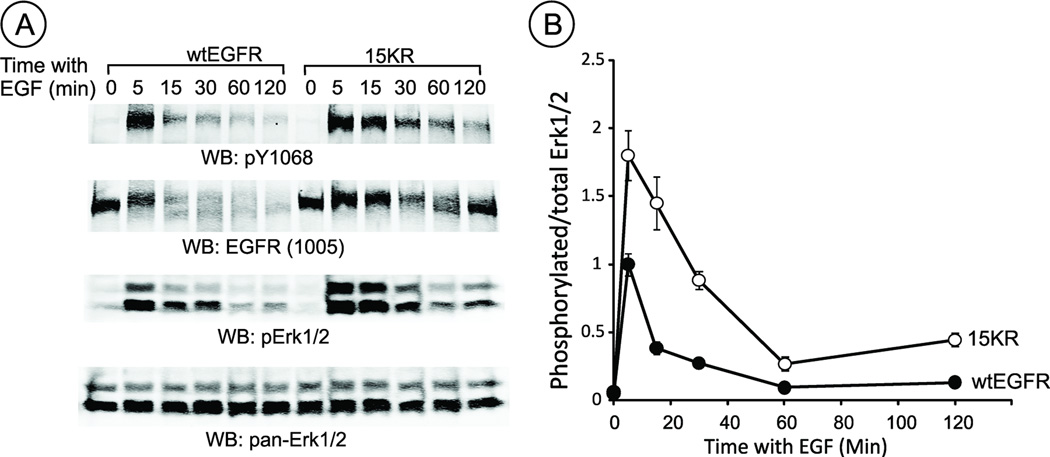

Figure 7. Prolonged Erk1/2 activity in cells expressing 15KR EGFR mutant.

Serum-starved cells expressing wtEGFR or 15KR mutant were stimulated with EGF (100 ng/ml) for indicated times and lysed. The lysates were probed by western blotting with antibodies to phosphorylated tyrosine 1068 of EGFR (pY1068), total EGFR, phosphorylated Erk1/2 and total Erk1/2. A, representative blots; B, Quantification of the amount of pErk1/2 normalized to the amount of total Erk1/2 using LI-COR imager (arbitrary units).

Incubation with transferrin-HRP (Tf-HRP) and anti-EGFR-gold revealed that while transferrin and EGFR are largely in separate compartments in wtEGFR cells, the majority of 15KR-EGFR co-localised with transferrin around the limiting membrane of MVBs, on tubular extensions, and in the pericentriolar recycling compartment (Figure 6B). Thus 15KR-EGFRs appear to traffic to the cell surface via the same endocytic recycling pathways as transferrin. Our demonstration here that in the presence of intact ESCRT machinery 15KR-EGFR fails to be retained in the MVB and is recycled via the same pathway as a non-ubiquitinated constitutively recycling receptor suggests that EGFR ubiquitination is required for ESCRT-mediated sequestration of the activated EGFR on the perimeter membrane of MVBs, as well as for EGF-stimulated ILV formation.

Mechanisms regulating recycling of EGF : EGFR complexes have received comparatively little attention, despite the potential importance of this fraction of receptor in prolonged signaling and tumorigenesis. Indeed, consistent with previous observations in cells expressing the 5KR EGFR mutant (25), activity of mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular-growth-factor-regulated kinase (Erk1/2) was increased and prolonged in cells expressing 15KR-EGFR as compared to wtEGFR-expressing cells (Figure 7). EGFR recycling is also increased in cells depleted of Hrs (11, 26); together these data indicate the importance of EGFR ubiquitination and recruitment of ESCRT protein complexes for trafficking-mediated downregulation of receptor tyrosine kinase activity.

In summary, we have identified EGFR ubiquitination as a key regulator of the endocytic pathway. In the presence of intact ESCRT machinery and normal ubiquitin ligase and EGFR kinase activity, non-ubiquitinated EGFRs, that do not efficiently engage the ESCRT machinery, failed to promote ILV formation, were not efficiently targeted to ILVs, and recycled to the plasma membrane via recycling tubules containing transferrin receptor.

METHODS

Cell culture

PAE cells stably expressing wild-type or 15KR EGFR (13) were cultured in Hams F-12 (Lonza) containing 10% fetal calf serum. Prior to stimulation with EGF (Sigma) at 100ng/ml in serum-free culture medium for indicated times, cells were serum-starved for 90 min at 37°C.

Antibodies

Rabbit anti-Hrs and anti-pY344-Hrs used in Western blotting (both 1 in 2000) were a gift from S. Urbe. The 108hEGFR antibody used for EGFR immunoprecipitation and in conventional EM was isolated from the Mab 108 hybridoma (ATCC). Sheep anti-EGFR antibody (Fitzgerald Industries International) was used for Western blotting EGFR immunoprecipitates (1 in 2000) and in cryoimmuno-EM (1 in 200) with rabbit anti-goat intermediate antibody (Autogen Bioclear).

Western blotting

Cell lysates prepared as previously described (14) were fractioned by SDS–PAGE under reducing conditions and immunoblotted on nitrocellulose membranes. Following incubation with infrared-fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies, membranes were scanned in an Odyssey SA scanner (LICOR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) and band intensities were quantified using Image J software.

Immunoprecipitation

Following crosslinking for 30 min at RT in DSP crosslinking solution (1mM DSP, 10mM Triethanolamine, 0.25M sucrose, 2mM CaCl2, pH 7.4) and blocking for 30 min at RT in blocking solution (10mM Triethanolamine, 0.25M sucrose, 2mM CaCl2, 50mM Ethanolamine, pH 7.4), EGFR was immunoprecipitated with 108hEGFR antibody. Immunoprecipitates were fractioned, immunoblotted and scanned as described for Western blotting.

Electron microscopy

Colloidal gold (10nm) solutions were prepared and coupled to BSA or anti-EGFR (Ab108) as described (27). EGF-HRP was prepared by mixing 5 µg of streptavidin-HRP (Invitrogen) and 0.3 µg of biotinylated EGF (Invitrogen) in 300 µl of PBS overnight at 4°C. Tf-HRP was prepared by cross-linking 2mg human iron-saturated transferrin to 5mg HRP using SPDP (Pierce) according to the manufacturer’s instructions; Conventional EM was as described (28) and the DAB reaction was as described (22). For cryo-immuno-EM, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.1% gluteraldehyde in 0.1M phosphate buffer at pH7.4, infused with 2.3M sucrose and supported in 12% gelatin. Sections (70nm) were cut at −120°C and collected in 1 : 1 2.3M sucrose:2% methylcellulose. Sections were incubated with sheep anti-EGFR antibody, rabbit anti-goat intermediate antibody and 10nm protein A gold as described (27). For quantification of ILV numbers by conventional EM, ILVs were counted in 100 MVBs per cell type over three separate experiments. MCSs, at which the perimiter membrane of the MVB and the ER were within 20nm, were counted in 20 MVBs per cell type, in cells stimulated with EGF-HRP for 1h and measured using ImageJ.

Fluorescence microscopy

48 h after transfection with GFP, YFP or Tomato tagged clathrin light chain or endosomal markers, cells were stimulated with EGF-Rh or EGF-Alexa647 (Molecular Probes) for 1 hr at 37°C, fixed and three-dimensional image acquisition was performed through Cy3, YFP and CFP filter channels using an epifluorescence Mariannas microscope system or spinning disk laser confocal microscope (Intelligent-Imaging Innovations, Inc.) as described (25). Constrained iterative deconvolution of epifluorescence images was performed using SlideBoook software. Quantification of co-localization of EGF-Alexa647 with YFP-EEA.1 was performed as described (25).

Duolink assay

Cells grown on coverslips were serum-starved for 90 min prior to 10 min stimulation with Alexa 647-conjugated EGF (200 ng/ml) in serum-free medium. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 20 min, permeabilized with 0.05% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min and blocked with 2% BSA for 30 min. Following labelling with 108anti-EGFR (1 in 200) and rabbit anti-Hrs (1 in 200) for 1 h at RT, the Duolink (Olink Bioscience) assay was performed in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Coverslips were mounted in Prolong Gold antifade reagent with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI ; Invitrogen) and images were acquired with a Leica DM-IRE2 microscope and TCS SP2 AOBS confocal system with a 63 ×/1.4 numerical aperture oil-immersion objective (Leica). Images were processed with Adobe Photoshop CS2 software (Adobe Systems).

125I-EGF recycling/degradation assay

Cells were incubated with 5 ng/ml 125I-EGF for 7 min at 37°C and washed in cold DMEM. Uninternalized 125I-EGF was removed from the cell surface by a 2.5-min acid wash (0.2 M sodium acetate, 0.5 M NaCl, pH 4.5). Cells were then chased in fresh binding medium containing 100 ng/ml unlabeled EGF at 37°C for 0–120 min. Intact and degraded 125I-EGF in the medium was measured by precipitation with trichloracetic acid/phosphotungstic acid (TCA/PPT; 3%/1%). Cells were incubated for five minutes with 0.2 M acetic acid (pH 2.8) containing 0.5 M NaCl at 4°C to determine the amount of surface-bound 125I-EGF and were solubilized in 1N NaOH to measure intracellular 125I-EGF. Recycled 125I-EGF, the sum of surface-bound and TCA/PPT-precipitated radioactivity in the medium, and degraded 125I-EGF, the TCA/PPT-soluble radioactivity in the medium, was expressed as the percent of the total 125I-EGF associated with cells and medium at each time point. Additionally, recycled 125I-EGF was plotted as percent of total recycled 125I-EGF at time “120 min”.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the Institute of Ophthalmology EM unit members for technical help and advice and Dr. L. Traub (University of Pittsburgh) for the clathrin-Tomato construct. This work was funded by CRUK (C20675), t h e M R C (G0801878) and the Wellcome Trust (078304) (to C. F. and E. E.) and NIH grants CA089151 and CA112219 (to A.S. and F.H.).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lemmon MA, Schlessinger J. Cell signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell. 2010;141(7):1117–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sorkin A, von Zastrow M. Endocytosis and signalling: intertwining molecular networks. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10(9):609–622. doi: 10.1038/nrm2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maxfield FR, McGraw TE. Endocytic recycling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5(2):121–132. doi: 10.1038/nrm1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gruenberg J, Stenmark H. The biogenesis of multivesicular endosomes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5(4):317–323. doi: 10.1038/nrm1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.White IJ, Bailey LM, Aghakhani MR, Moss SE, Futter CE. EGF stimulates annexin 1-dependent inward vesiculation in a multivesicular endosome subpopulation. Embo J. 2006;25(1):1–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Futter CE, Collinson LM, Backer JM, Hopkins CR. Human VPS34 is required for internal vesicle formation within multivesicular endosomes. J Cell Biol. 2001;155(7):1251–1264. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200108152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mosesson Y, Mills GB, Yarden Y. Derailed endocytosis: an emerging feature of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(11):835–850. doi: 10.1038/nrc2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levkowitz G, Waterman H, Zamir E, Kam Z, Oved S, Langdon WY, Beguinot L, Geiger B, Yarden Y. c-Cbl/Sli-1 regulates endocytic sorting and ubiquitination of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Genes Dev. 1998;12(23):3663–3674. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.23.3663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wollert T, Hurley JH. Molecular mechanism of multivesicular body biogenesis by ESCRT complexes. Nature. 2010;464(7290):864–869. doi: 10.1038/nature08849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saksena S, Wahlman J, Teis D, Johnson AE, Emr SD. Functional reconstitution of ESCRT-III assembly and disassembly. Cell. 2009;136(1):97–109. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Razi M, Futter CE. Distinct roles for Tsg101 and Hrs in multivesicular body formation and inward vesiculation. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17(8):3469–3483. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-11-1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doyotte A, Russell MR, Hopkins CR, Woodman PG. Depletion of TSG101 forms a mammalian "Class E" compartment: a multicisternal early endosome with multiple sorting defects. J Cell Sci. 2005;118(Pt 14):3003–3017. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang F, Goh LK, Sorkin A. EGF receptor ubiquitination is not necessary for its internalization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(43):16904–16909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707416104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eden ER, White IJ, Tsapara A, Futter CE. Membrane contacts between endosomes and ER provide sites for PTP1B-epidermal growth factor receptor interaction. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12(3):267–272. doi: 10.1038/ncb2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Theos AC, Truschel ST, Tenza D, Hurbain I, Harper DC, Berson JF, Thomas PC, Raposo G, Marks MS. A lumenal domain-dependent pathway for sorting to intralumenal vesicles of multivesicular endosomes involved in organelle morphogenesis. Dev Cell. 2006;10(3):343–354. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trajkovic K, Hsu C, Chiantia S, Rajendran L, Wenzel D, Wieland F, Schwille P, Brugger B, Simons M. Ceramide triggers budding of exosome vesicles into multivesicular endosomes. Science. 2008;319(5867):1244–1247. doi: 10.1126/science.1153124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chairoungdua A, Smith DL, Pochard P, Hull M, Caplan MJ. Exosome release of beta-catenin: a novel mechanism that antagonizes Wnt signaling. J Cell Biol. 2010;190(6):1079–1091. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201002049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mellman I. Endocytosis and molecular sorting. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1996;12:575–625. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gruenberg J, Maxfield FR. Membrane transport in the endocytic pathway. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1995;7(4):552–563. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sorkin A, Krolenko S, Kudrjavtceva N, Lazebnik J, Teslenko L, Soderquist AM, Nikolsky N. Recycling of epidermal growth factor-receptor complexes in A431 cells: identification of dual pathways. J Cell Biol. 1991;112(1):55–63. doi: 10.1083/jcb.112.1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Dam EM, Stoorvogel W. Dynamin-dependent transferrin receptor recycling by endosome-derived clathrin-coated vesicles. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13(1):169–182. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-07-0380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stoorvogel W, Oorschot V, Geuze HJ. A novel class of clathrin-coated vesicles budding from endosomes. J Cell Biol. 1996;132(1–2):21–33. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Futter CE, Gibson A, Allchin EH, Maxwell S, Ruddock LJ, Odorizzi G, Domingo D, Trowbridge IS, Hopkins CR. In polarized MDCK cells basolateral vesicles arise from clathrin-gamma-adaptin-coated domains on endosomal tubules. J Cell Biol. 1998;141(3):611–623. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.3.611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hislop JN, Henry AG, von Zastrow M. Ubiquitination in the first cytoplasmic loop of {micro}-opioid receptors reveals a hierarchical mechanism of lysosomal downregulation. J Biol Chem. 2011 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.288555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang F, Kirkpatrick D, Jiang X, Gygi S, Sorkin A. Differential regulation of EGF receptor internalization and degradation by multiubiquitination within the kinase domain. Mol Cell. 2006;21(6):737–748. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raiborg C, Malerod L, Pedersen NM, Stenmark H. Differential functions of Hrs and ESCRT proteins in endocytic membrane trafficking. Exp Cell Res. 2008;314(4):801–813. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Slot JW, Geuze HJ. A new method of preparing gold probes for multiple-labeling cytochemistry. Eur J Cell Biol. 1985;38(1):87–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tomas A, Futter C, Moss SE. Annexin 11 is required for midbody formation and completion of the terminal phase of cytokinesis. J Cell Biol. 2004;165(6):813–822. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200311054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]