Abstract

The assembly of clathrin-coated vesicles is important for numerous cellular processes, including nutrient uptake and membrane organization. Important contributors to clathrin assembly are four tetrameric Assembly Proteins, also called Adaptor Proteins (AP’s), each of which contains a beta subunit. We identified a single beta subunit, named β1/2, that contributes to both the AP1 and AP2 complexes of Dictyostelium. Disruption of the gene encoding β1/2 resulted in severe defects in growth, cytokinesis, and development. Additionally, cells lacking β1/2 displayed profound osmoregulatory defects including the absence of contractile vacuoles and mislocalization of contractile vacuole markers. The phenotypes of β1/2 were most similar to previously described phenotypes of clathrin and AP1 mutants, supporting a particularly important contribution of AP1 to clathrin pathways in Dictyostelium cells. The absence of β1/2 in cells led to significant reductions in the protein amounts of the medium-sized subunits of the AP1 and AP2 complexes, establishing a role for the beta subunit in the stability of the medium subunits. Dictyostelium β1/2 could resemble a common ancestor of the more specialized β1 and β2 subunits of the vertebrate AP complexes. Our results support the essential contribution a single beta subunit to the stability and function AP1 and AP2 in a simple eukaryote.

Keywords: Clathrin, adaptor, endocytosis, AP1, AP2, beta subunit, coated vesicles

INTRODUCTION

Clathrin coated vesicles are found in all eukaryotic cells and form when clathrin and accessory proteins assemble on the cytoplasmic surface of membranes, promoting the membrane to invaginate and subsequently detach into a spherical coated vesicle. Collectively, clathrin and accessory proteins function to mechanically shape the emerging spherical vesicle and also to select specific membrane proteins as cargo for the forming vesicles. Clathrin coated vesicles function in diverse cellular processes that include the uptake of nutrients and hormones from the extracellular milieu, the removal of signaling receptors from the plasma membrane, and directing lysosomal enzymes toward lysosomal compartments. Clathrin triskelia, the basic subunits of clathrin coats, have no intrinsic membrane-associating capability. Therefore, they rely on a host on clathrin adaptors to tether clathrin to the cytoplasmic leaflet of the vesicular membrane (1–3).

The archetypal clathrin accessory proteins are the multimeric Assembly Proteins (AP’s), which link clathrin triskelions to the membrane and recruit specific membrane cargo into the coated vesicle. Four AP complexes exist in mammals and each plays a unique role in trafficking. The contribution of AP1 to cellular function is currently debated, with evidence supporting both anterograde and retrograde trafficking between the trans-Golgi and endosomal compartments (4–7). AP2 participates in clathrin-mediated endocytosis at the plasma membrane. AP-3 and AP-4 pathways are less clearly defined, but both are proposed to function in endolysosomal trafficking (8–10).

AP complexes have been studied mostly in vertebrates where each AP complex is composed of four different subunits, consisting of two different large subunits (~105 kDa each), a medium subunit (~50 kDa) and a small subunit (~20 kDa, Figure 1A) (11, 12). Within each of the four AP complexes, one of the structural features with other beta subunits. All AP beta subunits contain an N-terminal trunk domain that forms the core of the brick-shaped AP complex (13, 14). Key residues within the trunk domain of the β2 subunit regulate the ability of the mu2 subunit to interact with specific membrane lipids (15). Binding of the β2 subunit to phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PtdIns4,5P2) influences the association of mu2 with surrounding PtdIns4,5P2. Subsequent large conformational changes in the mu2 subunit and movement of the β2 subunit uncover binding sites on mu2 for endocytic motifs on transmembrane cargo (16). This suggests coordinated roles for the β and mu2 subunits in regulating the binding of AP2 to PtdIns4,5P2 and to cargo destined for clathrin coated vesicles (15, 17, 18). Extending from the core domain of the beta subunit is a largely unstructured flexible hinge domain that is attached to a globular C-terminal appendage domain. Supporting their ability to serve as adaptors, the hinge regions of the AP1 and AP2 beta adaptins contain a canonical clathrin-binding box that allows these beta subunits to recruit and bind clathrin (19, 20). The C-terminal appendage domain of beta subunits interacts with other clathrin adaptors, promoting a cooperative recruitment of clathrin accessory proteins (14).

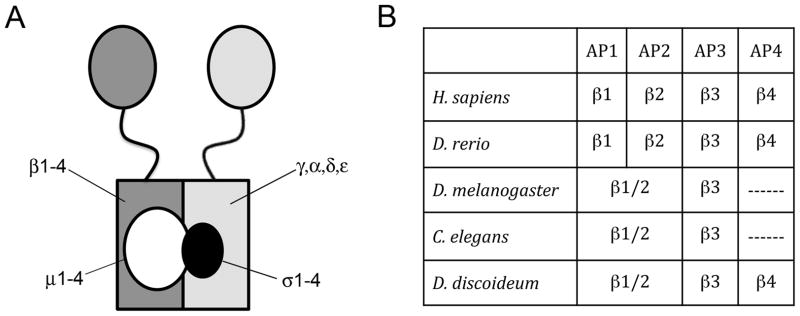

Figure 1. AP complex composition.

A. Each of the four vertebrate tetrameric AP complexes consists of two large subunits, one medium subunit and one small subunit. B. Vertebrate AP complexes contain four unique β subunits. D. melanogaster, C. elegans and D. discoideum contain only three with a single β subunit that could contribute to AP1 and AP2. See Supplemental Figure 1 for list of accession numbers for genes/gene products.

In vertebrates, each of the four beta subunits is specific to its respective AP complex and is not interchangeable with the analogous subunit from another complex (Figure 1B). This suggests that each subunit serves a unique function within the four AP complexes. However, analysis of the genomes of several invertebrates such as Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster and plants such as Arabadopsis thaliana have identified only a single gene for the beta subunit that could be shared between the AP1 and AP2 complexes (supplemental figure S1) (21, 22). These sequence analyses, as well as other functional studies, suggest that a single beta subunit could serve in both the AP1 and AP2 complexes in some organisms (23–25). This contrasts sharply with the widespread invariance of distinct beta subunits for AP3 and AP4, which have been shown to have strict specificity for their respective complexes (26, 27).

In the course of analyzing clathrin adaptors in Dictyostelium we identified a single beta adaptin subunit, β1/2, with amino acid sequence homology for the beta subunits of both AP1 and AP2. Our results demonstrate that this single beta subunit is shared between AP1 and AP2 and that β1/2 has a vital contribution to both the stability and the function of the AP1 and AP2 complexes. Taken together with previous phylogenetic studies, our study suggests that the β1/2 subunit of Dictyostelium resembles a common ancestor of the more specialized β1 and β2 subunits of the vertebrate AP complexes.

RESULTS

Identification of a single beta adaptin for the AP1 and AP2 complexes of Dictyostelium

To investigate tetrameric adaptor protein (AP) complexes in Dictyostelium we searched the sequenced genome for genes that could encode the subunits for the four AP complexes, AP1-AP4. The Dictyostelium genome sequence database contained four medium subunits (mu1-4) characterized previously that could contribute to the four tetrameric assembly proteins, AP1-AP4 (28, 29). We also identified four small subunits (sigma 1–4) that could contribute to AP1-4.

The presence of four unique medium and four unique small subunits suggested that Dictyostelium cells contained four tetrameric AP complexes. However, when we searched the Dictyostelium genome for large subunits, we identified only seven different subunits, instead of eight as would be expected if the four complexes each contained two unique large subunits. Of the seven large subunits that we identified, four shared sequence homology that corresponded to AP2 alpha (30), AP1 gamma (28), AP3 delta and AP4 epsilon. Two other large subunits in the database shared homology with AP3 beta and AP4 beta. However only a single beta subunit was found that could correspond to either the AP1 beta subunit or the AP2 beta subunit. Since this gene, ap1b1, shared sequence homology that was intermediate between AP1 beta and AP2 beta, we named the predicted protein β1/2.

The gene encoding β1/2 protein predicted a protein with 942 amino acids and a molecular weight of 107 kDa. Sequence analysis of β1/2 revealed structural features typical of beta adaptins, including the presence of an N-terminal trunk domain and a C-terminal beta adaptin appendage domain (13, 14) (Supplemental figure S2). These two conserved domains were joined by an unstructured flexible linker containing a clathrin-binding motif LIDLD, which conformed to the canonical clathrin-binding motif L(L,I)(D,E,N)(L,F)(D,E) (19). Taken together, our analysis of the Dictyostelium genome suggested that Dictyostelium cells contained four heterotetrameric AP proteins, AP1-AP4, and that a single beta subunit, could function in both the AP1 and AP2 complexes.

Loss of β1/2 leads to reduced amounts of mu1 and mu2 protein

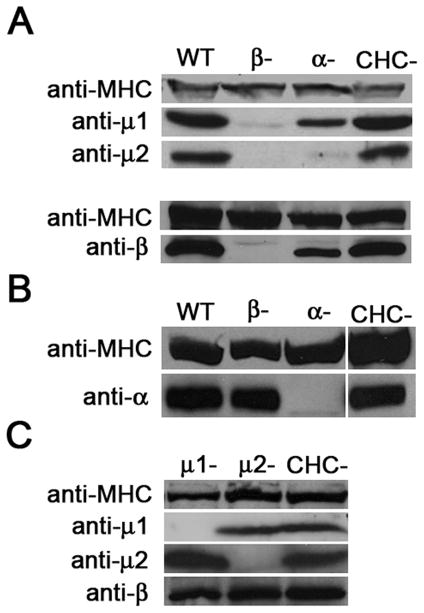

To determine the functional contribution of the single β subunit identified by sequence analysis, we cloned the single gene that encoded β1/2, used homologous recombination to delete the gene in Dictyostelium cells, and examined the phenotype of the null mutants. We first determined how the absence of the β1/2 protein influenced the stability of the remaining subunits of the AP1 and AP2 complexes. Western blot analysis revealed that β1/2 null cells contained only trace amounts of the medium subunits for AP1 (mu1) and AP2 (mu2), (Figure 2A) but relatively normal amounts of the large AP2α subunit (Figure 2B). This indicated that the absence of Dictyostelium β1/2 affected the stability of the medium subunits in both AP1 and AP2. To determine whether the other large subunit of AP2 could also affect medium subunits, we examined how the absence of AP2α influenced steady state levels of the remaining subunits. The AP2α null cells contained only trace amounts of the mu2 subunit, the medium subunit for AP2 (Figure 2A). In contrast, AP2α null cells contained levels of the mu1 subunit that were similar to wild-type cells, suggesting that the large AP2α subunits specifically stabilizes the medium subunit of the AP2 complex. To determine if the stabilization was unique for the medium subunits, we also analyzed the protein levels of one large subunit in cells lacking the other large subunit of the complex. AP2α levels appeared unaffected by the loss of β1/2, and, in the reciprocal experiment, the levels of β1/2 in AP2α null cells were also close to wild-type levels. These data suggest a major role for the large subunits of the AP1 and AP2 complexes in stabilizing the medium-sized subunits of their respective complexes.

Figure 2. The large subunits contribute to stability of the AP1 and AP2 complexes.

Western blots of whole cell lysates blotted with antibodies against the μ1, μ2, β subunits of the AP1 and AP2 complexes. (A–C) Western blots of whole cell lysates of wild-type cells (WT) and null mutants for AP1, AP2 subunits and clathrin heavy chain (CHC) were blotted with antibodies against the indicated AP subunits. Anti-myosin heavy chain (MHC) served as a loading control.

We next examined whether the absence of the medium subunits of AP1 and AP2 influenced the stability of the large beta subunit. Western blots showed that mu1 and mu2 null cells contained normal amounts of the β1/2 proteins (Figure 2C). Thus the absence of the large subunits impacted the stability of the medium subunits much more than the absence of the medium subunits impacted the large subunits. In addition, the influence of the large subunits on the stability of other subunits within the AP complex was not common to other coated pit proteins, as clathrin null cells showed normal levels of the large and medium subunits of AP1 and AP2.

The association of clathrin and AP2 with the plasma membrane is reduced in the absence of β1/2

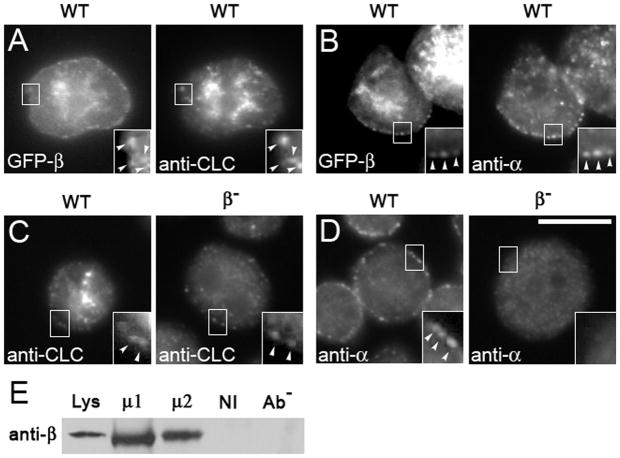

To determine the intracellular distribution of the β1/2 protein, we expressed a GFP-tagged version of the protein in wild-type cells. In wild-type cells, GFP-β1/2 distributed within punctae on the plasma membrane and concentrated in a dense cluster of fluorescence in the middle of the cell (Figure 3A). These locations were consistent with the incorporation of GFP-β1/2 into plasma-membrane-associated AP2 complexes and Golgi-associated AP1 complexes. Wild-type cells expressing GFP-tagged β1/2 and stained with anti-clathrin antibodies (31) revealed that clathrin co-localized with some of the punctae on the plasma membrane and co-localized extensively with the central cluster of fluorescence.

Figure 3. APβ1/2 co-localizes with and influences the localization of clathrin and alpha adaptin.

Cells transformed with GFP-tagged β1/2 (GFP-β) were immunostained. (A–B) GFP-β co-localizes with clathrin (A) and with punctae of AP2α at the cell periphery (B). (C–D) Gene disruption of APβ1/2 (β-) leads to the loss of clathrin (C) and loss of AP2α (D) at the cell periphery. Scale bar, 10μm. Cell lysates from wild-type cells were immunoprecipitated with either anti-μ1 (μ1) or anti-μ2 (μ2) and, as controls, non-immune serum (NI) and no antibody (Ab−). (E) Immunoprecipitates were assessed on Western blots probed with anti-APβ1/2 (anti-β) to detect co-immunoprecipitation of APβ1/2. APβ1/2 co-immunoprecipitates specifically with both μ1 and μ2.

We also stained cells that expressed GFP-β1/2 with an antibody against the AP2α (Figure 3B). Punctae on the membrane that contained the GFP-β1/2 stained brightly with the antibody against the alpha subunit, demonstrating that the punctae on the plasma membrane corresponded to AP2 complexes. The bright fluorescence in the center of the cell contained only GFP-β1/2, and not AP2α, consistent with the known localization of the Dictyostelium AP1 complex, which associates with clathrin structures near the nucleus (28).

We next examined how the absence of the β1/2 protein gene impacted the distribution of clathrin. Wild-type cells and β1/2 deficient cells were stained with anti-clathrin antibodies and examined by immunofluorescence microscopy (Figure 3C). Whereas wild-type cells showed punctae of clathrin on the plasma membrane and within the center of the cell, β1/2 null cells were lacking the bright cluster of fluorescent clathrin in the center of the cell, but continued to display fluorescent punctae on the plasma membrane. Besides clathrin, the absence of the β1/2 protein influenced the distribution of AP2α. Staining wild-type cells with anti-AP2α showed prominent staining of punctae on the plasma membrane (Figure 3D), the distribution typical for AP2α (30). However, β1/2 null cells showed an absence of AP2α on the plasma membrane. Taken together, these data suggest that β1/2 is critical for the distribution of clathrin within central cellular stores and for the plasma membrane localization of AP2, but is less important for the distribution of clathrin on the plasma membrane.

β1/2 associates with subunits of the AP1 and AP2 complexes

The previous studies provided visual evidence supporting a role for β1/2 in the AP1 and in the AP2 complexes. To further substantiate this role, we employed a biochemical approach to directly test for the association of Dictyostelium β1/2 with AP1 and A P 2 complexes. In co-immunoprecipitation experiments, we found that β1/2 co-immunoprecipitated in lysates precipitated with antibodies specific for either mu1 or for mu2 (Figure 3E). This association is specific, as experiments using non-immune serum or protein-A beads alone (no serum) were unable to pull down β1/2. These biochemical results, coupled with the localization data, provide strong evidence for a dual role for β1/2 in both the AP1 and AP2 complexes.

β1/2 null cells display defects in cytokinesis

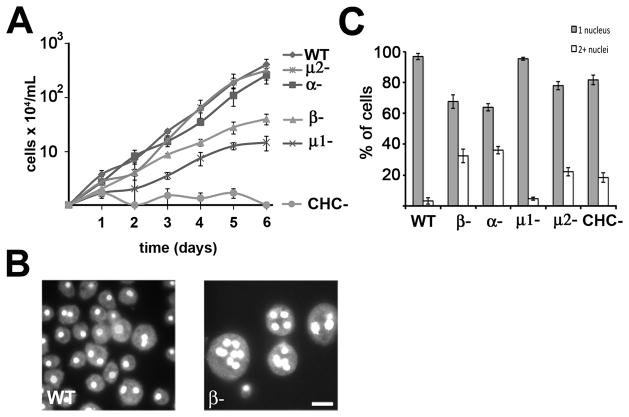

To examine the cellular contribution of β1/2, we examined the β1/2 null cells for phenotypic deficiencies typical of clathrin null cells. Previous studies of Dictyostelium clathrin heavy chain mutants (CHC-) have revealed that the clathrin heavy chain is required for cytokinesis in suspension cultures, as exhibited by an inability of CHC- cells to grow in suspension (33, 34). We compared the ability of various mutants to grow in suspension culture (Figure 4A). Wild-type cells grew well in suspension cultures, exhibiting a doubling time of 16.1 hours. In contrast,β1/2 null cells exhibited a significant growth defect with a longer doubling time (25.2 hours). To determine whether the growth defect was associated with a failure in cytokinesis, we stained wild-type andβ1/2 null cells with the DNA-binding dye DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) after they had grown in suspension for four days and looked for multinucleated cells. (Figure 4B). Whereas the majority of wild-type cells contained a single nucleus, the majority of β1/2 null cells contained multiple nuclei, consistent with a defect in cytokinesis. In agreement with previous studies, CHC- cells also displayed a severe defect in cell growth and failed to grow in suspension. The observed growth defect in CHC null cells was significantly more severe than the defect in beta null cells.

Figure 4. Gene disruption of APβ1/2 results in severe growth and cytokinesis defects.

(A) Cells at an initial concentration of 104 cells/mL were grown in suspension and counted every 24 hours. β1/2 null cells (β-) display a significant decrease in growth when compared to wild-type cells and cells deficient in subunits of AP2 (n=3 independent experiments, error bars = S.E.M.) (B) Cells from suspension culture were flattened, fixed and stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). β1/2 null cells (β-) display a cytokinesis defect as seen by large multinucleate cells. Scale = 10μm. (C) Nuclei stained with DAPI counted in cells grown in adherent cultures. Loss of APβ1/2 results in an increased number of multinucleate cells relative to wild-type cells and cells deficient in the mu1 subunit of AP1 (N=308–487 cells, 3–4 independent experiments).

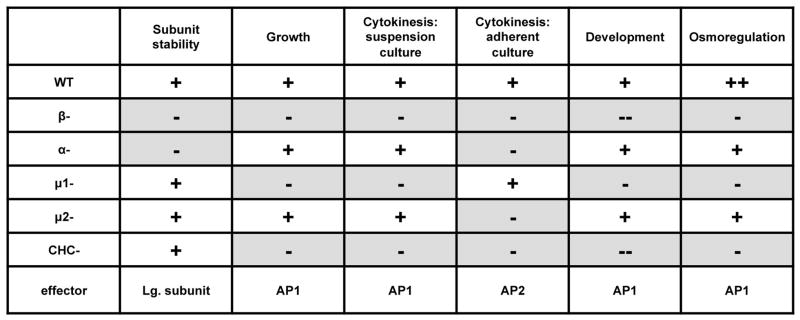

To evaluate the contribution of the other subunits of AP1 and AP2 to cytokinesis in suspension culture, we compared β1/2 null cells null cells with mutant cells carrying deletions in genes for other subunits of the AP1 and AP2 complexes. Similar to CHC- cells andβ1/2 null cells, mutants deficient in the AP1 medium subunit, mu1, displayed a significantly longer doubling time (34.2 hours). In contrast, mutants in two other subunits of the AP2 complex displayed growth rates similar to wild-type cells (alpha null cells = 18.2 hours; mu2 null cells = 16.2 hours). Thus, mutants in subunits of the AP1 complex (β1/2 and mu1) displayed cytokinesis defects when grown in suspension. These defects were similar to those of clathrin mutants, whereas mutants in subunits specific to the AP2 complex (alpha and mu2) grew similarly to wild-type cells.

Dictyostelium cells are known to use different modes of cytokinesis when grown in suspension and adherent cultures (35–37). To explore this, we investigated the ability of the various null cell lines to undergo cytokinesis in adherent culture by staining cells with DAPI and counting the number of nuclei in each cell (Figure 4C). In cultures of cells lacking subunits for the AP2 complex (AP2α, β1/2 or mu2), a large percentage of cells contained multiple nuclei (18–40%), indicating a significant cytokinesis defect in adherent culture. In contrast, cultures of cells lacking a subunit for AP1 (mu1) contained fewer than 4% multinucleated cells, a value more similar to the number of multinucleated cells in wild-type cells. Taken together these results suggested different phenotypes for AP1 and AP2, with subunits of AP1 (mu1, β1/2) required for cytokinesis in suspension cultures and subunits of AP2 (mu2, β1/2, alpha) in adherent culture.

β1/2 is required for osmoregulation

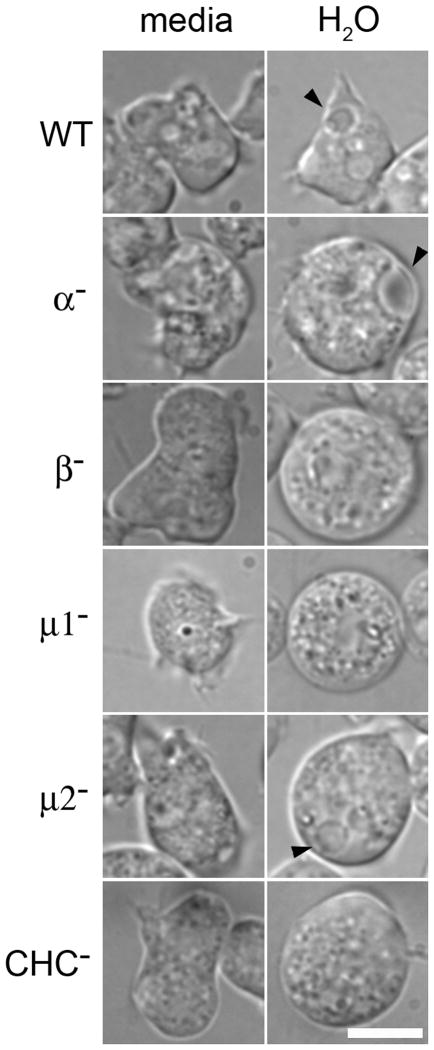

An additional clathrin-specific phenotype exhibited by Dictyostelium is a defect in osmoregulation (30, 31, 38–40). Dictyostelium cells are capable of surviving in hypo-osmotic environments due to osmoregulatory activity of the contractile vacuole. This membranous network of interconnected bladders and tubules fills with water and rapidly contracts, discharging water from the cell (38, 41, 42). To test a possible requirement for the β1/2 protein, we challenged β1/2 null cells null cells by transferring cells from isotonic media to water (Figure 5). When in media, wild-type cells contained numerous vacuoles. After the cells were immersed in water, many of these vacuoles expanded and then merged with the plasma membrane to discharge their contents. In contrast, even in media, β1/2 null cells had a smooth morphology, and lacked the large vacuoles characteristic of contractile vacuoles. When immersed in water, β1/2 null cells rapidly swelled, but remained smooth in appearance and without the engorged vacuoles typical of swollen contractile vacuoles. This phenotype was completely penetrant, as 100% (n=110 cells, 3 independent experiments) of observed cells lacked visible dajumin-GFP-labeled contractile vacuoles. The absence of swollen vacuoles in media and water was similar to the phenotype characteristic of mu1- and CHC- cells, which also did not contain large vacuoles when immersed in either water or media, but differed from mu2- cells, which contained swollen vacuoles.

Figure 5. Osmoregulation defects of APβ1/2 null cells.

Dictyostelium cells were photographed after incubation in water. Contractile vacuoles (arrows) were observed in wild-type, AP2aα null, andm2 null cells. APβ1/2β-, mu1 and clathrin heavy chain (CHC) null cells rapidly swelled and lacked large vacuoles. Scale bar, 5mm.

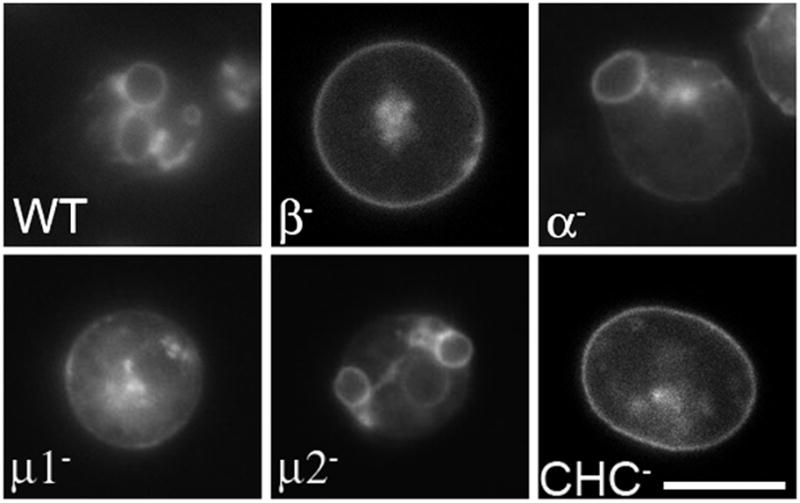

The preceding experiment established that osmoregulatory activity was compromised in β1/2 null cells. To investigate whether this deficiency was associated with altered contractile vacuole structure, we examined the distribution of dajumin-GFP, a known contractile vacuole membrane marker (38), in β1/2 null cells and other mutant backgrounds (Figure 6). In wild-type cells, dajumin-GFP localization was limited to the tubules and bladders of the contractile vacuole network. In mutants deficient for subunits specific to the AP2 complex (alpha and mu2), dajumin-GFP similarly labeled both the tubules and bladders of the contractile vacuole network. In mutants deficient in for subunits of AP1 (mu1), dajumin labeled patches of the plasma membrane and small vesicles inside. In β1/2 null cells, the labyrinth-like network of the contractile vacuole was missing. Instead dajumin-GFP uniformly and prominently labeled the plasma membrane as well as small vesicles clustered in the cell interior. The complete absence of a contractile vacuole and the redistribution of dajumin-GFP was observed in every β1/2 null cell examined (n=110, 3 independent experiments). An identical distribution of dajumin-GFP uniformly on the plasma membrane and within small vesicles was observed in CHC- cells. Thus the distribution of the contractile marker in β1/2 null cells was distinct from mutants in other AP subunits but was identical with the contractile vacuole marker distribution in the clathrin heavy chain mutant.

Figure 6. Loss of APβ1/2 leads to disruption of the contractile vacuole network.

Cells transformed with the contractile vacuole marker Dajumin-GFP were incubated in water and examined by fluorescence microscopy. Dajumin-labeled contractile vacuoles are seen in wild-type cells and cells deficient in the alpha (α) and medium (mu2) subunits of the AP2 complex. No contractile vacuoles were detected in 100% (n=110, 3 independent experiments) of cells deficient in APβ1/2 (β-), similar to μ1 or clathrin heavy chain mutants. Scale bar, 10μm.

Developmental defects in β1/2 null cells

Clathrin null cells display defects in development (43). In the unique Dictyostelium developmental cycle, ~105 cells aggregate and eventually form a multicellular fruiting body. The developmental cycle is triggered when nutrients are depleted, which stimulates individual amoeba to secrete pulses of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) from individual cells. Cells use these cAMP waves to migrate along the cAMP gradient towards an aggregation center. The culmination of development is the formation of a fruiting body, consisting of a stalk and a spore-filled sorus.

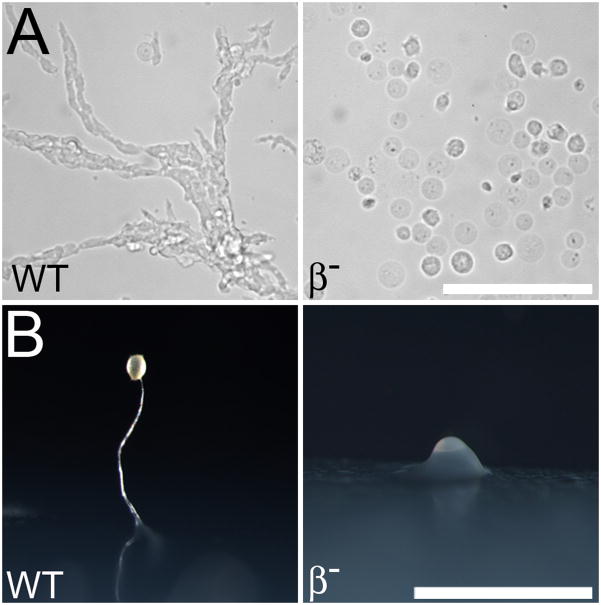

To test for a role of β1/2 in development, we inoculated wild-type and β1/2 null cells into starvation buffer. After twenty hours, the majority of wild-type cells had adopted an elongated morphology and collected into streams of cells (Figure 7A). In contrast, the majority of β1/2 cells were round and failed to aggregate. When plated on starvation plates, β1/2 cells also failed to aggregate (Figure 7B). Occasionally, a mound of β1/2- cells was observed, but never a fully differentiated fruiting body typical of wild-type cells. Thus the developmental phenotype of β1/2 - cells displayed was a severe disruption of their ability to construct a fruiting body, similar to the phenotype described for CHC- cells, and in contrast with the capacity of other AP subunits and clathrin adaptors, which are able to make fruiting bodies (28, 39, 40, 44, 45).

Figure 7. APβ1/2 null cells are defective in development and chemotaxis.

Cells were collected, washed and placed in chambers or on plates devoid of nutrients to induce chemotaxis and development. (A) Wild-type cells were observed undergoing chemotactic streaming, while beta null (β-) cells remained as individual cells. Scale bar, 100μm. (B) After incubation on starvation plates, wild-type cells developed into fruiting bodies and beta null cells failed to develop, progressing only to the tipped aggregate stage of development. Scale bar, 1mm.

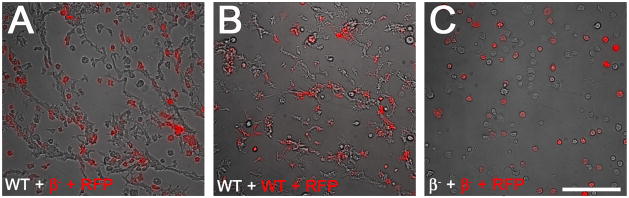

The developmental phenotype of β1/2- cells could be explained by either an inability to sense the chemotactic signal cAMP or by a defect in secreting cAMP. In order to distinguish between these possibilities, we mixed a smaller number β1/2- cells marked by RFP expression with a larger number of wild-type cells and allowed them to develop in starvation buffer (Figure 8). The RFP-labeled β1/2-cells readily integrated into chemotactic streams formed by the wild-type cells. This observation suggested that, if provided with appropriate cues, β1/2- cells can sense and respond to cAMP signals secreted by neighboring wild-type cells.

Figure 8. APβ1/2 null cells can sense cAMP.

Unlabeled Dictyostelium cells (70%) were mixed with RFP-expressing cells (30%) in starvation buffer and incubated for 17 hours to induce chemotactic aggregation. When mixed with unlabeled wild-type cells, RFP-expressing β1/2- cells migrated in streams (A), similar to mixed populations of labeled and unlabeled wild-type cells (B). Mixed populations of labeled and unlabeled β1/2- cells did not aggregate in response to starvation conditions (C). Scale bar, 100μm.

DISCUSSION

While mammalian cells have four distinct subunits for AP1, AP2, AP3 and AP4, we found that Dictyostelium cells have a single beta subunit, β1/2 that contributes to both AP1 and AP2. The presence of a hybrid beta subunit in Dictyostelium is not an anomaly among organisms: examination of sequence databases has revealed a single beta subunit for AP1 and AP2 in both Drosophila and C. elegans (21). Immunofluorescence experiments also have demonstrated that the single beta subunit found in Drosophila can associate with AP2 and AP1 when expressed in mammalian tissue culture cells (32). Sequence analysis of beta subunits in different organisms has led to the suggestion that, in contrast with the beta subunits for AP3 and AP4, two different beta subunits for AP1 and AP2 evolved through gene duplication relatively late in eukaryotic cells and independent of the AP1 and AP2 complexes (22). Surprisingly, S. cerevisiae contain 4 unique beta subunits, suggesting that yeast beta adaptins underwent a divergent evolution that was different from betas of higher eukaryotes. Our functional analysis of a single hybrid beta subunit for AP1 and AP2 extends the comparative analysis of gene sequences to determine the functional consequences of a single hybrid beta subunit.

Large AP subunits are required for medium subunit stability

By assessing the amounts of the remaining subunits in β1/2 null cells, we determined that the beta subunit is critical for stabilizing the medium subunits for both AP1 and AP2 in Dictyostelium. Our analysis of AP2α null cells indicates that this second large subunit in AP2 also stabilizes the mu2 subunit, as shown by the dramatic decrease in mu2 protein levels in AP2α null cells. Structural studies of the AP2 complex have revealed extensive intermolecular interactions between different subunits of the AP2 complex. While each of the subunits of the tetrameric complex interact with each other to some extent, major hydrophobic interactions are shared between the large beta subunit and the mu subunit and between the large alpha subunit and the smaller sigma subunit (17). Additionally, previous studies have demonstrated that deletion of AP large subunits destabilizes the smaller subunits (26, 46). In contrast, when the medium subunit mu1 is deleted in Dictyostelium, the large gamma subunit continues to assemble with the remaining AP1 subunits (28). However, these results are highly variable among several species. For example, loss of the large beta3 or delta subunits of the yeast AP3 complex has no effect on the stability of the mu3 subunit (47). Additionally, loss of the mu1A subunit of the AP1 complex in mice leads to decreased levels of gamma and sigma1 (48). Our results, combined with results from previous studies highlight the variable stability of the AP complexes across various model systems.

Functional redundancy of AP2, but not AP1, for clathrin distribution

β1/2 null cells exhibited severe deficiencies similar to those described previously for clathrin mutants and AP1 mutants (28, 40). These similar phenotypes could be explained by the different contributions of AP1 and AP2 to clathrin localization. The AP1 complex colocalizes with central stores of clathrin, and participates in processes such as contractile vacuole biogenesis and Golgi trafficking (28). In contrast, the AP2 complex localizes to the plasma membrane (30). We found that β1/2 mutants lost the normal distribution of clathrin within the center of the cell, but continued to assemble punctae of clathrin on their plasma membranes. The continued localization of clathrin on the plasma membrane could be explained by the presence of redundant clathrin adaptors at the cell periphery, which, in Dictyostelium include the clathrin-associated proteins epsin, AP180, and Hip1r (39, 44, 45). Conceivably, these clathrin adaptors could substitute for AP2, promote clathrin assembly and tether clathrin to the membrane in the absence of AP2. In contrast, AP1 is the sole clathrin adaptor in Dictyostelium cells known to associate with central stores of clathrin. Our results suggest that AP1 is much less functionally redundant with clathrin adaptors on internal stores of clathrin.

Distinct Roles for AP1 and AP2 in cytokinesis and osmoregulation

Comparison of mutant phenotypes can also be used to pinpoint intracellular pathways for AP1 and AP2 (Figure 9). Similar to clathrin mutants (34), β1/2 null cells display severe defects in cytokinesis. In Dictyostelium cells, cytokinesis occurs by two distinct pathways that depend on growth conditions. When cells are grown in suspension, cytokinesis occurs through myosin II-dependent constriction of the contractile ring (cytokinesis A). When cells are grown attached to a substrate, actin-driven radial polar extensions drive cytokinesis (cytokinesis B) (35). With this in mind, our data suggest distinct roles for the AP1 and AP2 complexes in cytokinesis A and B. Cells missing AP1 subunits (β1/2 and mu1) displayed severe cytokinesis defects in suspension cultures, suggesting a role for AP1 in cytokinesis A. Conversely, cells missing AP2 subunits (AP2α, β1/2 and mu2) displayed cytokinesis defects in adherent culture, suggesting a role for the AP2 complex in cytokinesis B. The cytokinesis defect of β1/2 null cells in both suspension and adherent cultures support functional contributions for β1/2 to both the AP1 and AP2 complexes.

Figure 9. Phenotypic comparisons of AP subunit mutants.

Shaded boxes represent phenotypic defects. Wild-type phenotypes are represented with a “+”. Defects are represented with a “−“. Deficiencies in AP1 subunits (β1/2 and μ1) closely resemble the phenotype of clathrin heavy chain mutants, suggesting a strong requirement for AP1 in clathrin-related processes.

Separate roles for AP1 and AP2 are also suggested by the distinct contractile vacuole phenotypes displayed by different mutants. The Dictyostelium contractile vacuole network is completely disrupted in cells lacking either the clathrin heavy chain or the AP1 subunit mu1 (28, 40). Similarly, we found that loss of β1/2 resulted in a severe disruption of the contractile vacuole network as revealed by the relocation of the contractile vacuole marker dajumin-GFP from an exclusive location of the contractile vacuole to a uniform distribution on the plasma membrane. Mu1 nulls expressing dajumin-GFP displayed a mislocalization of the contractile vacuole network. However, unlike beta null cells, mu1 nulls accumulated Dajumin-GFP in small internal vesicles.

In β1/2 null cells both AP1 and AP2 are disrupted, which could impact both contractile vacuole biogenesis (by the Golgi-associated AP1) and endocytosis of mis-sorted contractile vacuole resident proteins from the plasma membrane (by the plasma membrane-associated AP2). Consequently, β1/2 null cells display a uniform accumulation of the contractile vacuole marker along the plasma membrane. In contrast, disruption of the mu1 subunit affects only the AP1 complex, resulting in failure of only contractile vacuole biogenesis. This defect would result in mis-sorted contractile vacuole-associated proteins and accumulation of these proteins at the plasma membrane. Internal clusters of contractile vacuole membrane could be seen in mu1 cells. Unlike β1/2 null cells, where AP2 is disrupted, some of this mis-sorted Dajumin-GFP in mu1 null cells could be retrieved to internal compartments via the AP2 complex, resulting in both a punctuate plasma membrane distribution and the presence of labeled internal structures.

Based on our results and previous studies, we propose the following functions for clathrin, AP1 and AP2. Together with clathrin, AP1 participates in vesicular trafficking of internal stores of clathrin. These internal pools of clathrin vesicles could participate in an uncharacterized yet critical pathway for cytokinesis A, in development into robust fruiting bodies, and in a pathway required for contractile vacuole biogenesis such as the trafficking of important proteins from the TGN to the contractile vacuole. Together with clathrin, AP2 functions in plasma membrane events, many of which are functionally redundant with other plasma membrane adaptors. The phenotypes displayed by mutants deficient in AP2 subunits are less severe than AP1 mutants, yet also reveal non-redundant contributions of AP2 in recycling contractile vacuole proteins from the plasma membrane and a contribution to cytokinesis B. Taken together the phenotypes of β1/2 null cells emphasize the numerous and important roles for AP1 and AP2 in cell function and highlight the critical contribution of the β subunit to these complexes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and Cell Culture

Dictyostelium discoideum wild-type strain Ax2 was grown axenically at 20°C in HL-5 nutrient media supplemented with 0.6% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco-BRL, Gaithersburg, MD). Strains included AP2α knockouts (6A5) (30), and mu1 (28) and mu2 knockout (gift from Francois Letourneur). The AP2α and β1/2- knockouts were derived from the Ax2 parental strain as described below. Mu1 and mu2 mutants were derived from DH1-10 wild-type cells. These mutant strains were grown in HL-5 media supplemented with 5 μg/mL blasticidin (A.G. Scientific, Inc., San Diego, CA) and 0.6% penicillin-streptomycin. Cells transformed with GFP expression plasmids were grown in media supplemented with 10 μg/mL G418 (geneticin, Gibco-BRL, Invitrogen, Inc., Carlsbad, CA) and 0.6% penicillin-streptomycin.

Cloning of Ap1b1

The ap1b1 and apm2 genes encoding the AP1/AP2 beta adaptin and mu2 gene products were identified by using BLAST searches of the Dictyostelium genome database (dictybase.org). Predicted proteins were analyzed and aligned with beta adaptins or mu2s from other species using the Megalign program (DNAStar, Madison, WI). The ap1b1 coding region was amplified from Dictyostelium cDNA in two fragments using the primers 5′-CGCGGATCCATGTCTGACTCAAAGTATTTTC-3′ and 5′-CATCGAGATGACTAGTCGTATCAGTAATG-3′ (5′ end of ap1b1) and 5′-ACTGATACCAC AGTCATCTCGATG-3′ and 5′-AGGCCCGGGATTTAAATTTGATTATTAATTAATAA A-3′ (3′ end). Each PCR product was cloned into the pCR-2.1 vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The apm2 coding region was amplified using the primers 5′-CGCGGATCCATGATTAGTGCATTATTCTTAATG-3′ and 5′-TCCCCCGGGTTTTAAATACGATTTTGATAGGTACC AG-3′. The resulting ~450 bp piece was subcloned into pCR2.1

Generation of polyclonal antibodies

cDNA’s encoding the ap1b1 or the apm2 gene products were cloned into the glutathione-S-transferase bacterial expression vector pGEX-2T. The resulting plasmids were transformed into Escherichia coli BL-21 cells, and the GST-β fusion protein or GST-mu2 proteins were purified as previously described (49). The purified proteins were used to generate both rabbit and guinea pig polyclonal antibodies (Cocalico Biologicals, Reamstown, PA). For western blots, the guinea pig antibody against GST-β was used at 1:1000; the rabbit polyclonal antibodies against GST-mu2 protein were used at 1:1000.

Gene Disruption of Ap1b1

PCR was used to amplify the 5′ and 3′ regions flanking the ap1b1 gene. The 5′ upstream region was amplified using 5 ′-AAGCTTATTTATTGGTAGTGTCAACCCATTTCATTGTTTTTCC-3′ and 5′-CTTTTTATTTGTTTTCATTCGGGGGTGTG-3′. The 3′ downstream region of ap1b1 was amplified using 5′-GAAAAAGCAATAGCAATGATAAAGGATAGAGA-3′ and 5′-GGATCCATGCATCTTCTAAAACTTTAATTGTATCAGTTCTACC-3′. Each PCR product was cloned into pCR2.1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and subsequently subcloned into pSP72-Bsr (50), which carries a blasticidin-resistance gene. This knockout construct was linearized using XhoI and EcoRV. 10ug linearized construct was transformed by electroporation into Dictyostelium discoideum Ax2 cells, and recombinants were selected in HL-5 media supplemented with 5ug/mL blasticidin. Clones were screened by PCR and western blotting with anti-β antibodies for the deletion of the gene and the absence of the β1/2 protein.

Co-Immunoprecipitation

Dictyostelium cells were harvested, resuspended to 5 × 107 cells/mL in lysis buffer (20mM TES (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 1mM EGTA) with protease inhibitors diluted to the manufacturer’s instructions (Fungal Protease Inhibitor cocktail, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and lysed by passing through two polycarbonate membrane’s (5μm, GE Osmonics, Trevose, PA) in a Gelman Luer-Lock-style filter (Gelman Sciences, Ann Arbor, MI). Lysates were cleared by centrifugation (13K rpm, 5 min, 4°C). Cleared lysate supernatant samples were taken and added to SDS-PAGE sample buffer for Western Blot analysis. One mL of the cleared lysate supernatant was added to 400μl of polyclonal serum (goat-anti-μ1, goat-anti-μ2, or pre-immune serum) and incubated overnight at 4°C with rocking. 100μL of Protein A agarose beads (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) were added to the serum-lysate mixture and incubated overnight at 4°C with rocking. Beads were collected by centrifugation and washed five times with 1mL TBS-Plus Buffer (1.5M NaCl, 0.5M NaCl, 0.5M Tris-HCl, 0.5% Triton-X100, 0.1% SDS, 1% NP-40, pH 7.5), and unbound lysate was collected for Western blot analysis. To elute bound proteins from the protein A beads, the beads were resuspended in 50μL 0.1M Glycine buffer (pH 3.0) and incubated at room temperature for 3 min. Beads were collected by centrifugation and eluate samples were collected. Elution was repeated by addition of 50μL Glycine buffer, centrifugation and collection. Neutralization of samples was achieved by addition of 10μL of 1M Tris-HCl to elutions. SDS-PAGE sample buffer was added to both the elutions and beads for Western Blot analysis.

Western Blotting

Dictyostelium cells were harvested, resuspended in SDS-containing sample buffer, loaded at a concentration of 106 cells per well, run on 7.5% polyacrylamide gel, and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. After blocking with 5% milk in Tris-buffered saline (TBS), membranes were incubated with primary antibodies, washed with TBS, and incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL). Membranes were developed using Pierce ECL Western Blotting Substrate (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL)

Measurement of Growth Rate

Cells were inoculated into HL-5 media at an initial concentration of 104 cells/mL and grown in shaking culture at 20°C. Concentrations were measured every 24 hours for a period of 10 days.

Development Assays

To induce development, 108 cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed with starvation buffer (20 mM MES pH 6.8, 0.2 mM CaCl2, 2 mM MgSO4), plated at 107 cells/mL on 10cm starvation plates (starvation buffer, 1% Noble Agar (BD, Sparks, MD)) and incubated at 20°C. Images of the developing plates were taken using a Leica MZ16F (Leica Microsystems, Bannockburn, IL) dissection microscope using a Leica DFC480 camera and associated Leica imaging software. For mixed population chemotaxis assays, 106 cells (30% expressing pTX-RFP) were collected by centrifugation, washed with starvation buffer, plated in 2-well borosilicate chambers and incubated for 17 hours. Differential interference contrast and fluorescence images were taken using a 20 × 0.50 NA PanFluor objective as described below.

Microscopy

Cells expressing GFP fusion proteins were harvested, allowed to attach to coverslips for 30 minutes and incubated in low-fluorescence media (51) for 30 minutes before live visualization. Similarly, DAPI-stained cells were allowed to attach to coverslips and fixed in a cold solution of 1% formaldehyde in methanol for 5 minutes. Cells were washed in PDF (2 mM KCl, 1.1 mM K2HPO4, 13.2 mM KH2PO4) and stained in 0.1 ug/mL (286nM) DAPI for 10 minutes. Stained cells were washed with PDF before mounting.

Differential interference contrast and fluorescence images were taken on an inverted Nikon Eclipse TE 200 microscope (Nikon Instruments, Dallas, TX) using a 100 × 1.4 NA PlanFluor objective or a 20 × 0.50 NA PanFluor objective and Quantix 57 camera (Roper Scientific, AZ) controlled by Metamorph imaging software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Accession numbers for the proteins and gene products of β adaptins from Homo sapiens, Danio rerio, Drosophila melanogaster, Caenorhabditis elegans and Dictyostelium discoideum.

Figure S2. Amino acid sequence of Dictyostelium discoideum β1/2. Solid underline represents the N-terminal trunk domain, shaded box represent the clathrin binding motif, and the dashed underline represents the C-terminal appendage domain.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the O’Halloran lab and Arturo De Lozanne for critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank Francois Letourneur for his generous gift of mu1 and mu2 mutant cells and anti-mu1 antibodies. This work is supported by NIH R01 GM048625 and R01 GM089896 to T.J.O.

References

- 1.Bonifacino JS, Lippincott-Schwartz J. Coat proteins: shaping membrane transport. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4(5):409–414. doi: 10.1038/nrm1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brodsky FM, Chen CY, Knuehl C, Towler MC, Wakeham DE. Biological basket weaving: formation and function of clathrin-coated vesicles. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2001;17:517–568. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmid EM, McMahon HT. Integrating molecular and network biology to decode endocytosis. Nature. 2007;448(7156):883–888. doi: 10.1038/nature06031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robinson MS, Sahlender DA, Foster SD. Rapid inactivation of proteins by rapamycin-induced rerouting to mitochondria. Dev Cell. 2010;18(2):324–331. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foote C, Nothwehr SF. The clathrin adaptor complex 1 directly binds to a sorting signal in Ste13p to reduce the rate of its trafficking to the late endosome of yeast. J Cell Biol. 2006;173(4):615–626. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200510161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonifacino JS, Rojas R. Retrograde transport from endosomes to the trans-Golgi network. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7(8):568–579. doi: 10.1038/nrm1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robinson MS. Adaptable adaptors for coated vesicles. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14(4):167–174. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakatsu F, Ohno H. Adaptor protein complexes as the key regulators of protein sorting in the post-Golgi network. Cell Struct Funct. 2003;28(5):419–429. doi: 10.1247/csf.28.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charette SJ, Mercanti V, Letourneur F, Bennett N, Cosson P. A role for adaptor protein-3 complex in the organization of the endocytic pathway in Dictyostelium. Traffic. 2006;7(11):1528–1538. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirchhausen T. Clathrin. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:699–727. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Traub LM. Clathrin-associated adaptor proteins - putting it all together. Trends Cell Biol. 1997;7(2):43–46. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(96)20042-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirst J, Robinson MS. Clathrin and adaptors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1404(1–2):173–193. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(98)00056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirchhausen T, Nathanson KL, Matsui W, Vaisberg A, Chow EP, Burne C, Keen JH, Davis AE. Structural and functional division into two domains of the large (100- to 115-kDa) chains of the clathrin-associated protein complex AP-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86(8):2612–2616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.8.2612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Owen DJ, Vallis Y, Pearse BM, McMahon HT, Evans PR. The structure and function of the beta 2-adaptin appendage domain. EMBO J. 2000;19(16):4216–4227. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.16.4216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Owen DJ, Evans PR. A structural explanation for the recognition of tyrosine-based endocytotic signals. Science. 1998;282(5392):1327–1332. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5392.1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson LP, Kelly BT, McCoy AJ, Gaffry T, James LC, Collins BM, Honing S, Evans PR, Owen DJ. A large-scale conformational change couples membrane recruitment to cargo binding in the AP2 clathrin adaptor complex. Cell. 2010;141(7):1220–1229. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Owen DJ, Collins BM, Evans PR. Adaptors for clathrin coats: structure and function. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:153–191. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.104543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collins BM, McCoy AJ, Kent HM, Evans PR, Owen DJ. Molecular architecture and functional model of the endocytic AP2 complex. Cell. 2002;109(4):523–535. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00735-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dell’Angelica EC, Klumperman J, Stoorvogel W, Bonifacino JS. Association of the AP-3 adaptor complex with clathrin. Science. 1998;280(5362):431–434. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5362.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shih W, Gallusser A, Kirchhausen T. A clathrin-binding site in the hinge of the beta 2 chain of mammalian AP-2 complexes. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(52):31083–31090. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.52.31083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boehm M, Bonifacino JS. Adaptins: the final recount. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12(10):2907–2920. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.10.2907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dacks JB, Poon PP, Field MC. Phylogeny of endocytic components yields insight into the process of nonendosymbiotic organelle evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(2):588–593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707318105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Page LJ, Robinson MS. Targeting signals and subunit interactions in coated vesicle adaptor complexes. J Cell Biol. 1995;131(3):619–630. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.3.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keyel PA, Thieman JR, Roth R, Erkan E, Everett ET, Watkins SC, Heuser JE, Traub LM. The AP-2 adaptor beta2 appendage scaffolds alternate cargo endocytosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19(12):5309–5326. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-07-0712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li W, Puertollano R, Bonifacino JS, Overbeek PA, Everett ET. EDITOR’S CHOICE: Disruption of the Murine Ap2beta1 Gene Causes Nonsyndromic Cleft Palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2010;47(6):566–573. doi: 10.1597/09-145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peden AA, Rudge RE, Lui WW, Robinson MS. Assembly and function of AP-3 complexes in cells expressing mutant subunits. J Cell Biol. 2002;156(2):327–336. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200107140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirst J, Bright NA, Rous B, Robinson MS. Characterization of a fourth adaptor-related protein complex. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10(8):2787–2802. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.8.2787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lefkir Y, de Chassey B, Dubois A, Bogdanovic A, Brady RJ, Destaing O, Bruckert F, O’Halloran TJ, Cosson P, Letourneur F. The AP-1 clathrin-adaptor is required for lysosomal enzymes sorting and biogenesis of the contractile vacuole complex in Dictyostelium cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14(5):1835–1851. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-10-0627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Chassey B, Dubois A, Lefkir Y, Letourneur F. Identification of clathrin-adaptor medium chains in Dictyostelium discoideum: differential expression during development. Gene. 2001;262(1–2):115–122. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00545-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wen Y, Stavrou I, Bersuker K, Brady RJ, De Lozanne A, O’Halloran TJ. AP180-mediated trafficking of Vamp7B limits homotypic fusion of Dictyostelium contractile vacuoles. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20(20):4278–4288. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-03-0243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang J, Virta VC, Riddelle-Spencer K, O’Halloran TJ. Compromise of clathrin function and membrane association by clathrin light chain deletion. Traffic. 2003;4(12):891–901. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-0854.2003.00144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Camidge DR, Pearse BM. Cloning of Drosophila beta-adaptin and its localization on expression in mammalian cells. J Cell Sci. 1994;107 ( Pt 3):709–718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gerald NJ, Damer CK, O’Halloran TJ, De Lozanne A. Cytokinesis failure in clathrin-minus cells is caused by cleavage furrow instability. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2001;48(3):213–223. doi: 10.1002/1097-0169(200103)48:3<213::AID-CM1010>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niswonger ML, O’Halloran TJ. A novel role for clathrin in cytokinesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(16):8575–8578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nagasaki A, Hibi M, Asano Y, Uyeda TQ. Genetic approaches to dissect the mechanisms of two distinct pathways of cell cycle-coupled cytokinesis in Dictyostelium. Cell Struct Funct. 2001;26(6):585–591. doi: 10.1247/csf.26.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagasaki A, de Hostos EL, Uyeda TQ. Genetic and morphological evidence for two parallel pathways of cell-cycle-coupled cytokinesis in Dictyostelium. J Cell Sci. 2002;115(Pt 10):2241–2251. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.10.2241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Uyeda TQ, Kitayama C, Yumura S. Myosin II-independent cytokinesis in Dictyostelium: its mechanism and implications. Cell Struct Funct. 2000;25(1):1–10. doi: 10.1247/csf.25.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gabriel D, Hacker U, Kohler J, Muller-Taubenberger A, Schwartz JM, Westphal M, Gerisch G. The contractile vacuole network of Dictyostelium as a distinct organelle: its dynamics visualized by a GFP marker protein. J Cell Sci. 1999;112 ( Pt 22):3995–4005. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.22.3995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stavrou I, O’Halloran TJ. The monomeric clathrin assembly protein, AP180, regulates contractile vacuole size in Dictyostelium discoideum. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17(12):5381–5389. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-06-0531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Halloran TJ, Anderson RG. Clathrin heavy chain is required for pinocytosis, the presence of large vacuoles, and development in Dictyostelium. J Cell Biol. 1992;118(6):1371–1377. doi: 10.1083/jcb.118.6.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heuser J, Zhu Q, Clarke M. Proton pumps populate the contractile vacuoles of Dictyostelium amoebae. J Cell Biol. 1993;121(6):1311–1327. doi: 10.1083/jcb.121.6.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gerisch G, Heuser J, Clarke M. Tubular-vesicular transformation in the contractile vacuole system of Dictyostelium. Cell Biol Int. 2002;26(10):845–852. doi: 10.1006/cbir.2002.0938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Niswonger ML, O’Halloran TJ. Clathrin heavy chain is required for spore cell but not stalk cell differentiation in Dictyostelium discoideum. Development. 1997;124(2):443–451. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.2.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Repass SL, Brady RJ, O’Halloran TJ. Dictyostelium Hip1r contributes to spore shape and requires epsin for phosphorylation and localization. J Cell Sci. 2007;120(Pt 22):3977–3988. doi: 10.1242/jcs.011213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brady RJ, Wen Y, O’Halloran TJ. The ENTH and C-terminal domains of Dictyostelium epsin cooperate to regulate the dynamic interaction with clathrin-coated pits. J Cell Sci. 2008;121(Pt 20):3433–3444. doi: 10.1242/jcs.032573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yeung BG, Phan HL, Payne GS. Adaptor complex-independent clathrin function in yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10(11):3643–3659. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.11.3643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Panek HR, Stepp JD, Engle HM, Marks KM, Tan PK, Lemmon SK, Robinson LC. Suppressors of YCK-encoded yeast casein kinase 1 deficiency define the four subunits of a novel clathrin AP-like complex. EMBO J. 1997;16(14):4194–4204. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.14.4194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meyer C, Zizioli D, Lausmann S, Eskelinen EL, Hamann J, Saftig P, von Figura K, Schu P. mu1A-adaptin-deficient mice: lethality, loss of AP-1 binding and rerouting of mannose 6-phosphate receptors. EMBO J. 2000;19(10):2193–2203. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.10.2193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vithalani KK, Parent CA, Thorn EM, Penn M, Larochelle DA, Devreotes PN, De Lozanne A. Identification of darlin, a Dictyostelium protein with Armadillo-like repeats that binds to small GTPases and is important for the proper aggregation of developing cells. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9(11):3095–3106. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.11.3095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang N, Wu WI, De Lozanne A. BEACH family of proteins: phylogenetic and functional analysis of six Dictyostelium BEACH proteins. J Cell Biochem. 2002;86(3):561–570. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu T, Mirschberger C, Chooback L, Arana Q, Dal Sacco Z, MacWilliams H, Clarke M. Altered expression of the 100 kDa subunit of the Dictyostelium vacuolar proton pump impairs enzyme assembly, endocytic function and cytosolic pH regulation. J Cell Sci. 2002;115(Pt 9):1907–1918. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.9.1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Accession numbers for the proteins and gene products of β adaptins from Homo sapiens, Danio rerio, Drosophila melanogaster, Caenorhabditis elegans and Dictyostelium discoideum.

Figure S2. Amino acid sequence of Dictyostelium discoideum β1/2. Solid underline represents the N-terminal trunk domain, shaded box represent the clathrin binding motif, and the dashed underline represents the C-terminal appendage domain.