Abstract

The last decade has seen the evolution and ongoing refinement of a disease-oriented approach to chronic kidney disease (CKD). Disease-oriented models of care assume a direct causal association between observed signs and symptoms and underlying disease pathophysiology. Treatment plans target underlying disease mechanisms with the goal of improving disease-related outcomes. Because average levels of glomerular filtrate rate (GFR) tend to decrease with age, CKD becomes increasingly prevalent with advancing age, and those who meet criteria for CKD are disproportionately elderly. However, several features of geriatric populations may limit the utility of disease-oriented models of care. In older adults, complex comorbidity and geriatric syndromes are common, signs and symptoms often do not reflect a single underlying pathophysiologic process, there can be substantial heterogeneity in life expectancy, functional status and health priorities, and information on the safety and efficacy of interventions is often lacking. For all these reasons, geriatricians have tended to favor an individualized patient-centered model of care over more traditional disease-based approaches. An individualized approach prioritizes patient preferences and embraces the notion that observed signs and symptoms often do not reflect a single unifying disease process, and instead reflect the complex interplay between many different factors. This approach emphasizes modifiable outcomes that matter to the patient. Prognostic information related to these and other outcomes is generally used to shape rather than dictate treatment decisions. We herein argue that an individualized patient-centered approach to care may have more to offer than a traditional disease-based approach to CKD in many older adults.

Keywords: elderly, disease-oriented, individualized, patient-centered, kidney disease

Introduction

Well-defined disease-oriented models of care exist for a variety of different conditions. These models assume a direct causal relationship between observed signs and symptoms and underlying disease pathophysiology (Table 1).1, 2 Treatment plans target pathophysiologic mechanisms relevant to the disease process with the goal of improving disease-related outcomes. Symptoms and other impairments related to the disease are generally addressed by treatments directed at the underlying disease process. The disease-oriented approach serves as the dominant paradigm underpinning medical education, clinical practice and health policy in this country.2 This approach has the advantage of providing a systematic framework to guide and standardize management, outcome evaluation and performance measurement in patients with clearly defined disease processes. The disease-oriented approach and related practice guidelines are intended to provide a simple “framework” or “model” that can be applied to defined populations rather than to comprehensively address the myriad concerns and situations that can arise in individual patients.3 The tension inherent to the disease-based approach between what is relevant at the population vs. individual levels may be greater for some groups of patients than for others. The appropriateness of the disease-oriented approach has been questioned in particular for patients with limited life-expectancy, functional impairment and complex co-morbidity.2, 4 For such patients, disease-oriented models of care may fail to address those outcomes of foremost concern to the patient, and in so doing may lead to inappropriate treatment strategies with greater potential for harm than benefit. 2, 4

Table 1.

Disease-Oriented Versus Individualized Patient-Centered Approaches

| Disease-oriented | Individualized patient-centered | |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Decision Making* | Focuses on prevention, diagnosis and treatment of individual disease processes. |

Focuses on the priorities and preferences of individual patients. |

| Underlying conceptualization of disease* |

Disease results from an underlying pathophysiologic process. |

Disease reflects the complex relationship between pathology, aging, social, psychological and other factors. |

| Treatment* | Targets underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms causing the disease process. |

Targets modifiable factors impacting outcomes that matter to the patient, whether or not these are related one or more underlying disease processes. |

| Approach to symptoms* | Symptoms related to the disease-process are best treated by interventions targeted at the disease. |

Symptoms can be a target for treatment even if they cannot be tied to a defined disease process. |

| Goals of treatment* | Clinical outcomes are those relevant to the underlying disease process. Survival is often considered to be the most important outcome. |

Clinical outcomes are those that matter most to the patient and can be modified. In many instances, survival may be of less importance than other outcomes such as quality of life, functional status, pain control and independence. |

| Advantages | Provides a systematic framework for standardized evidence-based management of single disease processes. Is readily adapted to outcome assessment and performance measurement. |

Embraces the possibility that older patients may have multiple different co-morbid conditions and that there is heterogeneity in health status, life expectancy, and treatment efficacy and patient preferences among older adults. |

| Disadvantages | Provides little guidance on how to negotiate the conflicting treatment priorities that arise in patients with multiple different co-morbid conditions, limited life expectancy, and distinct treatment preferences. |

Clinicians may be inadequately prepared to identify patient preferences and goals and incorporate these into treatment strategies. There may be little evidence to support treatment decisions if outcomes that matter to the patient have not been studied. Does not lend itself to standardized practices, performance measurement and outcome assessment. |

Adapted from Tinetti and Fried2 with permission of The Association of Professors of Medicine.

Limitations of a Disease-Based Approach

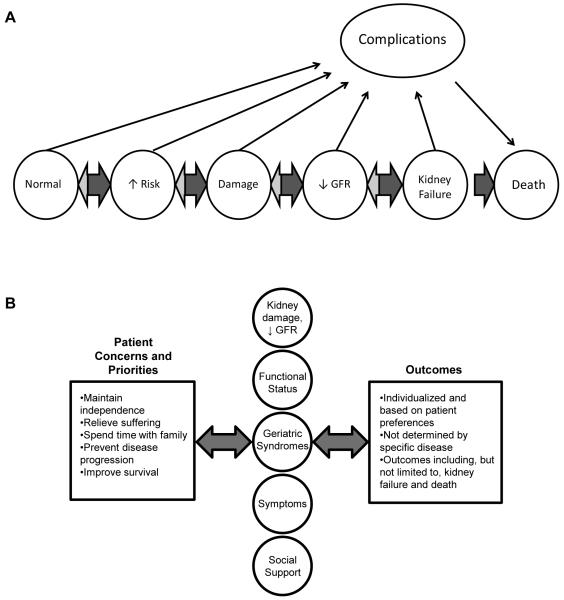

The last decade has seen the evolution of a disease-based approach to chronic kidney disease (CKD) involving the development, dissemination, and refinement of practice guidelines for this condition (Figure 1).1 These guidelines have served a variety of different purposes that include establishment of a working definition of CKD, systematic review of available evidence, and formulation of treatment strategies and potential performance measures based on available evidence.5-7

Figure 1.

Conceptual models for (A) disease-oriented and (B) patient-centered individualized approaches to older adults with CKD.

Panel A modified and reproduced with permission from the National Kidney Foundation.5

Because abnormalities in glomerular filtration rate (GFR), and to a lesser extent urinary protein excretion, become increasingly prevalent with advancing age, patients with CKD defined based on level of GFR and urinary protein excretion are disproportionately elderly.8 The systematic approach to screening, diagnosis and treatment embodied in the disease-oriented approach to CKD can clearly be beneficial in some older adults. Case 1 describes an elderly patient in otherwise good health who developed an ANCA-associated pauci-immune vasculitis and clearly benefitted from disease-based interventions. If left untreated, his underlying glomerulonephritis would almost certainly have resulted in rapid progression to end-stage renal disease and early mortality. However, for elderly patients with more complex comorbidity, more limited life expectancy, and whose clinical presentation may be less directly linked to a defined disease pathology, a disease-oriented approach may be less beneficial and may even confer harm. Case 2 describes a patient in the final stages of dementia with very limited life expectancy. In this patient, worsening delirium and anorexia are unlikely to be the result of her CKD, although uremia may be a contributing factor. It is unlikely that dialysis alone will lead to a resolution of this patient’s presenting symptoms or meaningfully change her prognosis. Moreover, dialysis is an intensive and invasive life-sustaining treatment with potential to aggravate delirium and prolong the dying process in this patient.

While these cases describe extreme examples, several pervasive features of aging that are discussed in more detail below (including a high prevalence of complex comorbidity and heterogeneity in life expectancy, functional status and treatment preferences) serve to highlight the limitations of a disease-oriented approach, and may ultimately restrict the benefits of such an approach in many older adults (Table 2). Because complex co-morbidity, impaired functional status, and limited life expectancy are more common at older ages, a patient’s age may be helpful in identifying those who are less likely to benefit from a disease-oriented approach. However, as illustrated in Cases 1 and 2 (describing patients aged 84 and 72 years, respectively) chronologic age per se may be less important than health status, life expectancy and preferences in determining the value of a disease-oriented approach.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Older Adults That May Limit the Benefits of a Disease-Oriented Approach

| Characteristic | Implications |

|---|---|

| The presence of multiple co-existing co-morbid conditions becomes increasingly common at older ages. |

Interventions targeted at a single co-morbid condition may be discordant with interventions for other conditions present in a given patient, and may have unintended adverse consequences. |

| Signs and symptoms often do not result from a single underlying pathophysiologic process in older adults. |

May limit the benefit of interventions targeted at underlying pathophysiologic processes and may undervalue interventions directed at constellations of symptoms that are not due to a clearly defined underlying pathophysiologic processes. May also not address contextual factors that go beyond the individual patients (eg, social support, caregiver perspective). |

| Life expectancy, functional status and health priorities can vary greatly among patients of similar chronologic age. |

The benefits and harms of recommended interventions and the relevance of disease-based outcomes can be highly variable in older adults. |

| Older adults are often implicitly or explicitly excluded from randomized clinical trials. |

The safety and efficacy of recommended interventions are often unknown in older adults. |

Multi-morbidity, defined as the presence of more than one chronic condition, becomes much more common with age,9 and is particularly common in older adults who meet criteria for CKD.10 The coexistence of multiple chronic conditions often results in atypical clinical presentations, poor diagnostic accuracy of laboratory tests and conflicting treatment priorities.11 In patients with multiple different co-morbid conditions, there may be complex dynamic relationships between individual co-morbid conditions. Some may be concordant and have similar treatments and outcomes, while others will be discordant and call for opposing treatment strategies.12, 13 For example, preventive interventions to improve blood pressure, blood glucose and lipid control in older adults with CKD are often concordant with those of other chronic co-morbid conditions that frequently co-exist in these patients (e.g., diabetes, vascular disease, and hypertension). Other chronic age-associated conditions such as arthritis and cognitive impairment that are also common in patients with CKD may call for discordant interventions. For example, pain medications for arthritis can be nephrotoxic and promote loss of kidney function. Optimal dementia management may call for less complex medication regimens, fewer clinic visits, and fewer invasive procedures and hospital admissions. Individual conditions may show a greater or lesser degree of concordance over time, as for example when contrast administration for coronary angiography is required in a patient with advanced CKD who develops unstable angina. Disease-oriented models of care rarely provide guidance on how to accommodate the competing, conflicting and changing treatment priorities that inevitably arise in patients with more than one treatable co-morbid condition.14

Because most disease-oriented models of care do not account for the presence of more than one co-morbid condition, applying disease-oriented guidelines to patients with multiple chronic medical conditions may have unintended consequences that may be harmful. Boyd et al. considered the impact of applying disease-specific guidelines to a hypothetical case of a 79-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, osteoporosis, osteoarthritis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.14 The approach of applying recommendations from all relevant disease-based guidelines resulted in an onerous pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic treatment regimen with multiple potential drug interactions and competing treatment priorities. On review of the various guidelines pertaining to the care of this hypothetical patient, these authors noted that only one guideline actually acknowledged the possibility that the patient may have more than one chronic condition.

In part because of the high prevalence of complex co-morbidity, signs and symptoms in older adults are often multi-factorial reflecting the complex interplay between one or more chronic predisposing and acute precipitating events. In many instances, a direct relationship between disease manifestations and underlying disease pathophysiology will be lacking. As an example, some older adults who do not have clinically significant dementia have been found to have pathologic changes associated with Alzheimer disease on autopsy.15 Similarly, age-related pathologic changes in the kidney seem to correlate poorly with intra-individual differences in measured kidney function among patients of similar ages.16 By emphasizing discrete diseases based on underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms, a disease-oriented approach may fail to recognize and adequately address constellations of impairments that span multiple different organ systems and functional domains.17, 18 In such situations, efforts to identify and treat one or more underlying disease processes may have less impact than efforts to directly address observed symptoms and functional impairments. Addressing geriatric syndromes in older adults with CKD may be particularly important given the high prevalence of these syndromes in this population. Frailty is common even among younger patients with CKD and the prevalence of frailty, functional impairment, and cognitive impairment is much higher in older adults with abnormalities in kidney function compared to those without.19-24

Increasing heterogeneity in life expectancy and functional status is an important feature of aging that may impact the benefits and harms of recommended interventions and is not easily accommodated within a disease-oriented framework.25, 26 While life expectancy generally decreases with age, it can vary widely across individuals within a given age group. For example, among US patients aged 65-79 years of age at initiation of long-term dialysis, median survival was approximately two years, but with an interquartile range between 8.3 months and more than four years.27 Similarly, while many older adults experience functional decline, this process is far from uniform and patterns of functional status are often dynamic with transitions between independence and disability frequently superimposed on longer-term functional trajectories.28, 29 In part because of variability in life expectancy and functional status, there is also substantial heterogeneity in health priorities among older adults.30 Preferences may be influenced by the burden of treatments, potential outcomes, as well as perceptions about life expectancy. For many patients approaching the end of life, maintaining function, cognition and quality of life becomes relatively more important than maximizing life expectancy.31, 32 Additionally, when considering treatment options, older adults may be influenced more by the risk of side-effects than the potential for risk reduction in disease outcomes associated with treatment.33, 34 Because disease-oriented models of care tend to prioritize disease-related outcomes (e.g., survival, disease progression), these models may fail to address those outcomes that matter most to the patient (e.g., pain control, independence) if these are not directly related to the underlying disease process.

It is important to remember that information on the safety and efficacy of many interventions recommended in disease-based guidelines is often lacking in older adults. In a wide range of different areas, older adults have been implicitly or explicitly excluded from clinical trials, and systematic bias in the characteristics of enrolled participants often further limits the relevance of trial results to older populations.35-37 Not uncommonly, the results of trials that have enrolled older adults conflict with those in younger, lower risk populations.38, 39 While it is also the case that patients with CKD have been underrepresented in randomized controlled trials,40 this is particularly true for older members of this group, for whom evidence may be lacking even for proven CKD-related interventions. In a review of trials used by contemporary guidelines to support the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) for slowing progression of CKD, O’Hare et al. reported that few trials enrolled adults aged 70 or older and most implicitly or explicitly selected for proteinuria.41 Thus the body of evidence supporting the use of these agents to slow progression of CKD (a well proven disease-related intervention) may not be relevant to the substantial number of older adults who meet criteria for CKD, but do not have proteinuria.41 Similar concerns may apply to evidence supporting lower-than-usual blood pressure targets for patients with CKD.42

Individualized Patient-Centered Care

Given the limitations of disease-oriented models of care in older populations, geriatricians often favor a more individualized patient-centered approach. The individualized approach prioritizes patient goals and preferences and embraces the notion that observed signs and symptoms may not be the consequence of a single disease process, but instead reflect the complex interplay between a variety of different factors including pathology, aging, social and psychological factors (Table 1 and Figure 1).2 In contrast with the disease-oriented approach in which relevant outcomes are dictated by the underlying disease process, the individualized approach emphasizes modifiable outcomes that matter to the patient. Signs and symptom may represent legitimate treatment targets in their own right, even if they do not occur as the direct result of a recognized disease process. Importantly, a patient-oriented approach goes beyond the individual patient to incorporate information on social support and family dynamics, highlighting the role of caregivers. Disease-specific diagnosis and management is not abandoned completely, and may be incorporated into individualized treatment plans, depending on the extent to which disease-based recommendations are aligned with the preferences and goals of the patient. Individualized treatment plans are intended to be dynamic and bidirectional in order to accommodate changes in health priorities that may occur over time, as for example with new health events, changes in functional status or social support (e.g., death of a spouse). Because published data to support individualized treatment strategies may be scarce, and because the individualized approach does not necessarily prioritize traditional disease-oriented outcomes studied in clinical trials, this approach may not lend itself to outcome assessment and performance measurement or to formal comparisons with the disease-oriented approach.43

Disease-Oriented Versus Individualized Patient-Centered Care

The majority of older adults with CKD will fall somewhere between the two extreme cases presented earlier. Unlike the patient described in case 1, clinical presentation and treatment options are unlikely to be shaped by a single underlying pathophysiologic process and most will have competing health priorities and unique preferences. Nevertheless, many will derive some benefit from disease-based interventions unlike the patient described in case 2. However, these interventions may be most beneficial if deployed within the broader context of an individualized patient-centered approach to care. Such an approach has potential to generate very different treatment plans for patients with the same disease stage.

For example, a 76 year-old woman with a severe reduction in GFR, moderate proteinuria, hypertension, diabetes and painful arthritis asks whether it would be acceptable to use a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) to ease her joint pain. The disease-oriented approach would prioritize blood pressure control and other efforts to minimize disease progression and cardiovascular risk such as avoiding NSAIDs and use of an ACE inhibitor or ARB. Management of painful arthritis with NSAIDs might lead to worsening kidney function and worse blood pressure control and would thus be largely discordant with a disease-oriented approach to CKD (case 3, Box 1). Nevertheless, if pain relief (and the freedom this may provide to lead a more active life) is a priority, the patient may be willing to make tradeoffs, particularly if her risk of experiencing clinically significant progression of kidney disease is low. In order to optimize pain management, she may be willing to accept the risk of worsening kidney function and higher blood pressure associated with NSAID use. While an ACE inhibitor or ARB would ordinarily be recommended for her hypertension, a different agent might be preferable in the setting of starting an NSAID. Over time, her willingness to tradeoff worsening kidney function for better pain control may change, particularly if her kidney function worsens substantially.

Box 1. Comparing Patient-Centered Individualized Versus Disease-Oriented Approaches in Individual Patients.

Case 3: 76 year old woman with HTN, diabetes and severe osteoarthritis. She is independent in all instrumental and basic activities of living. She has a stable GFR of 25-30 ml/min/1.73 m2 and proteinuria (2+). On exam, her BP is 140/90 mm Hg, she has no edema, and has substantial difficulty rising from the chair at the end of the visit. She has grandchildren who live close by and would love to be more involved in their daily lives, but her arthritis pain limits her mobility outside the home. She asks whether it would be acceptable to take a NSAID because other pain medications are either ineffective or have intolerable side effects.

Table 4.

| Disease-oriented approach | Individualized patient-centered approach | |

|---|---|---|

|

Clinical Decision Making: |

History and Exam: elicit signs and symptoms relevant to CKD (e.g., presence of edema, BP). Work-up: assess severity of kidney function, proteinuria, estimate progression. |

History and Exam: elicit symptoms that are bothersome and treatable, ascertain treatment preferences, estimate life expectancy and other risks (e.g., worsening kidney function). Work-up: tailor evaluation to match patient concerns, e.g., evaluation of mobility and gait (stand from seated position, walk 10 ft and return to chair). |

|

Underlying conceptualization of disease: |

Use of NSAIDs will likely have an adverse effect on kidney function and BP. High BP may result in progression of underlying kidney disease and also confers an increased risk of death and CV events. |

Competing and conflicting treatment priorities may exist in the setting of more than one treatable co-morbid condition. While NSAIDs will likely have an undesirable effect on CKD and HTN, they may represent the best approach toward treating arthritis pain. |

| Treatment: | Advise the patient to minimize or avoid NSAIDs. Recommend addition of an ACEi to lower BP, slow progression of kidney disease, and reduce CV risk in this patient with poorly controlled HTN, diabetes and proteinuria. |

Discuss the benefits and harms of NSAIDs with the patient who may consider trading off worsening kidney function and BP for better pain control. Target symptoms and limitations that matter to the patient, in this case pain management and mobility impairment (e.g., physical therapy, occupational therapy, assistive devices) CKD-based treatment might involve identifying ways to treat BP that do not increase the risk associated with NSAID administration (e.g., use of diltiazem instead of an ACEi) and to monitor the impact of the NSAID on BP and kidney function (e.g., closer monitoring of kidney function, more attention to salt intake, further incremental changes to anti-hypertensive regimen). |

|

Approach to symptoms: |

The patient’s joint pain is unlikely to be related to CKD. | Treatment targeted at what matters most to the patient, recognizing that symptoms may take precedence over disease-based abnormalities even if these cannot be ascribed to an underlying disease process. |

|

Goals of treatment: |

Clinical outcomes include preserving kidney function, decreasing proteinuria, and reducing CV risk. |

Clinical outcomes are those that matter to the patient and can be modified, and may include both traditional disease- and non—disease-based outcomes. Improved pain control might be more important for this patient than preserving kidney function or optimizing BP. |

Case 4: 72 year old man with HTN, diabetes, moderate dementia complicated by an increasing frequency of behavioral symptoms, episodes of urinary incontinence, and recurrent falls. His BP is 190/80 mm Hg and he has lower extremity edema (1-2+). He lives at home with his wife and requires 24 hour supervision. He has a stable GFR of 25-30 ml/min/1.73 m2 and an ACR ratio of 400 mg/g. An ultrasound several years ago showed 12 cm kidneys and no hydronephrosis. His wife asks whether he really needs to keep coming to renal clinic.

Table 5.

| Disease-oriented approach | Individualized patient-centered approach | |

|---|---|---|

|

Clinical Decision Making: |

History and Exam: elicit signs and symptoms relevant to CKD (e.g., presence of edema, BP). Work-up: assess severity of kidney disease, proteinuria, progression, evaluation renal conditions that might contribute to patient’s presentation (e.g., UTI) |

History and Exam: elicit symptoms that are bothersome to the patient and treatable, ascertain patient and family treatment preferences, evaluate caregiver stress. Work-up: evaluation for factors contributing to geriatric syndromes (e.g., evaluation for orthostatic hypotension, UTI, new medications, constipation). |

|

Underlying conceptualization of disease: |

Nephrology referral is recommended for patients with advanced kidney disease in order to optimize management of disease complications and progression, and to prepare for ESRD. Lowering BP will reduce risk of progressive kidney disease, mortality and vascular events, and may also reduce risk of cognitive dysfunction. |

While the patient may benefit from specialized nephrology care, he and his wife are dealing with several competing concerns that may be of higher priority. The patient has worsening functional impairment/geriatric syndromes that should probably be prioritized. The wife may be experiencing caregiver burnout. |

| Treatment: | Recommend continued visits to nephrology and explore whether less frequent visits or phone follow-up might be possible. Recommend addition of an ACEi or ARB to manage HTN in the setting of proteinuria and diabetes. Recommend a diuretic for edema and additional BP control. |

Discuss the benefits and harms of nephrology visits from the point of view of the patient and caregiver, explore alternative approaches to providing care (e.g. co-management with PCP, delayed follow-up after acute issues have resolved). Explore resources available to support the caregiver. Treat underlying precipitants of evolving geriatric syndromes (e.g., UTI, constipation). Remove precipitating factors for falls and incontinence (e.g. avoid rising rapidly from sitting position, treat UTI). Limit effects of predisposing factors for falls and incontinence (e.g., more assistance during high risk activities, use cane or walker). Discontinue or change the dose or dosing schedule of medications that may be contributing to geriatric syndromes and avoid medications that could worsen these with consideration of overall pill burden (e.g., diuretic may worsen incontinence, ACEi will require a follow-up laboratory test, limiting the number of new medications). Some aspects of CKD-based treatment might be appropriate if likely to prevent outcomes that would interfere with patient and family goals. Optimal BP control may prevent further cognitive decline but choice of agents might be tailored to simultaneously address other priorities. |

|

Approach to symptoms: |

The patient does not have symptoms that are clearly due to his underlying CKD. It might be important to rule out a UTI as a cause for his deterioration. |

Symptoms are likely multi-factorial and if modifiable and bothersome to the patient and caregiver, should be targeted using multi-faceted interventions (e.g., identification precipitants, caregiver education, increasing social support and non-pharmocologic approaches.) |

|

Goals of treatment: |

Clinical outcomes include preserving kidney function, decreasing proteinuria, reducing CV risk and identification of possible renal factors that might be contributing to patient’s presentation. |

Clinical outcomes matter to the patient and caregiver and that can be modified. For example, addressing and decreasing caregiver burden, managing geriatric symptoms and ensuring appropriate level of care might be priorities in this patient. |

Abbreviations: ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ACR, albumin-creatinine ratio; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BP, blood pressure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CV, cardiovascular; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; HTN, hypertension; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; PCP, primary care physician; UTI, urinary tract infection.

A 72 year old man also has a severe reduction in GFR and hypertension, but in addition, has moderate dementia that is complicated by behavioral symptoms and episodes of urinary incontinence requiring full-time caregiver support at home (case 4, Box 1). The patient’s wife reports increasing difficulty managing his behavioral symptoms, more frequent episodes of urinary incontinence, and recurrent falls and asks whether her husband needs to continue to come to nephrology clinic. The disease-oriented approach would prioritize nephrology follow-up, blood pressure control along with other interventions to slow and manage progression in this patient with advanced kidney disease and poorly controlled blood pressure. An ACE inhibitor or ARB and possibly a diuretic would likely be considered agents of choice. However, given this patient’s competing health priorities and social situation, frequent nephrology follow-up may not be feasible. Blood pressure control may represent an important goal if optimizing blood pressure will reduce the risk of stroke and help to preserve cognitive function. However, in selecting a treatment regimen, side-effect profile and simplicity of dosing might weigh more heavily than efficacy in lowering blood pressure. For example, use of a diuretic may aggravate symptoms of incontinence and predispose to dehydration, perhaps increasing caregiver burden. A repeat visit for laboratory testing after initiating an ACE inhibitor to recheck serum creatinine and potassium might be too burdensome for the patient and caregiver at this time. These kinds of complex decisions can only be made after first eliciting the concerns and preferences of the patient and/or caregiver. Most importantly, the most pressing issues facing this patient and his caregiver have little to do with his CKD and might be missed under a purely disease-based approach. Addressing the patient’s worsening behavioral symptoms, incontinence and falls is clearly of much greater immediate importance than controlling blood pressure, although these symptoms are unlikely to be related to CKD or to any other single underlying disease process. The wife may be developing caregiver burnout. Exploring the rationale behind her question about nephrology visits might represent an important opportunity to explore this possibility, and one that might easily be missed under a disease-oriented model focused primarily on the patient.

Role of Prognostic Information and Individualized Patient-Centered Care

Although individualized treatment plans are driven by patient preferences and values, accurate prognostic information is often very helpful in crafting these plans. For example, treatment decisions for the patient described in case 3 may depend on her expected risk of progressive loss of kidney function with and without NSAID use. The extent to which the patient described in case 4 and his caregiver prioritize visits to renal clinic may depend on his expected risk of progressing to end-stage renal disease vs. the competing risk of death. The extent to which blood pressure control is prioritized may depend on his risk of stroke and progressive cognitive decline and how this might be expected to vary as a function of blood pressure. Over the last several years, a growing number of studies have evaluated the prognostic significance of eGFR and proteinuria.44-47 As a result of this work, we will likely see refinement of the existing classification system for CKD to incorporate more accurate and detailed information on the independent prognostic significance of eGFR and proteinuria, and perhaps other measures.48, 49While eGFR and proteinuria are both independently associated with key clinical outcomes in older adults (e.g., mortality, progression to ESRD, cardiovascular events), most studies have not provided detailed age-stratified results. Most also do not present information on a broad range of outcomes with potential relevance to older adults such as quality of life, functional status, and independence. Available data suggest that the magnitude of the association of eGFR with some outcomes is modified by age, and that the absolute risk for specific outcomes can vary substantially across age groups, in some cases as a function of other characteristics such as race and gender.50-54 As we learn more about the complex associations between different clinically available renal measures, patient characteristics such as age, gender and race, and a range of different outcomes, we will likely see greater reliance on risk scores and other approaches to conveying complex prognostic information in an easily digestible format.55 As providers, patients and their families strive to make the best decisions possible given their own treatment goals and priorities, ongoing efforts to improve risk stratification based on renal measures may be extremely helpful in developing individualized care plans.45, 46, 49 Specific information on absolute risks for a range of patient-centered outcomes and information on possible modifying factors in older adults will be particularly helpful for supporting individualized treatment plans in this group, as will information on the comparative effectiveness of different clinical interventions in older adults with CKD.

Conclusions

For many older adults who meet criteria for CKD, an individualized patient-centered approach may have more to offer than the traditional disease-oriented approach. An important feature of the individualized approach is that it can always accommodate disease-based treatment strategies if these are aligned with patient goals and preferences. On the other hand, treatment strategies that are informed only by the presence and severity of abnormalities in kidney function (and associated risk information) may carry more potential for harm than benefit if these fail to capture patient goals and preferences and to address heterogeneity in the implications of recommended treatments.

Case Presentation.

Case 1

A healthy 84 year old man with mild hypertension and no other comorbid conditions had a GFR of 70 ml/min/1.73 m2 (1.17 mL/s/1.73 m2) and no proteinuria. Over a several week period, his GFR fell to 20 ml/min/1.73 m2 (0.33 mL/s/1.73 m2) and he was found to have proteinuria (2+) and red blood cell casts on urinalysis. On further testing, he had a protein-creatinine ratio of 2000 mg/g and serologic work up was notable for the presence of a positive anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA). He underwent a kidney biopsy that showed a pauci-immune necrotizing crescentic glomerulonephritis. He was treated with cyclophosphamide and prednisone. His GFR returned to baseline and his proteinuria and hematuria resolved and he was switched to maintenance therapy with azathioprine and prednisone.

Case 2

A 72 year old woman with advanced dementia, diabetes and hypertension, has had a GFR of 15-20 ml/min/1.73 m2 (0.25-0.33 mL/s/1.73 m2) for the last three years. She lives at home with her husband and requires help with bathing, dressing and toileting. Her husband is her primary caregiver and has durable power of attorney for healthcare. She was admitted to the hospital because of worsening disorientation and irritability, urinary incontinence, and anorexia. Her GFR on admission to the hospital had fallen to 10 ml/min/1.73 m2 (0.17 mL/s/1.73 m2). Because her symptoms of worsening confusion and anorexia were felt to possibly be due to uremia, dialysis was initiated. However, these symptoms only worsened after dialysis initiation.

Table 3. Comparing patient-centered individualized vs. disease-oriented approaches in individual patients.

| CASE 3 | ||

|---|---|---|

| 76 year old woman with hypertension, diabetes and severe osteoarthritis. She is independent in all instrumental and basic activities of living. She has a stable GFR of 25-30 ml/min/1.73 m2 and 2+ proteinuria. On exam, her blood pressure is 140/90 mm Hg, she has no edema, and has substantial difficulty rising from the chair at the end of the visit. She has grandchildren who live close by and would love to be more involved in their daily lives, but her arthritis pain limits her mobility outside the home. She asks you whether it would be acceptable to take a non-steroidal agent (NSAID) because other pain medications are either ineffective or have intolerable side effects. |

||

| Disease-oriented approach | Individualized patient-centered approach | |

| Clinical Decision Making |

|

|

| Underlying conceptualization of disease |

|

|

| Treatment |

|

|

| Approach to symptoms |

|

|

| Goals of treatment |

|

|

| CASE 4 | ||

|---|---|---|

| 72 year old man with hypertension, diabetes, moderate dementia complicated by an increasing frequency of behavioral symptoms, episodes of urinary incontinence, and recurrent falls. His blood pressure is elevated at 190/80 mm Hg and he has 1-2+ lower extremity edema. He lives at home with his wife and requires 24 hour supervision. He has a stable GFR of 25-30 ml/min/1.73 m2 and an albumin-to-creatinine ratio of 400 mg/mg. An ultrasound several years ago showed 12 cm kidneys and no hydronephrosis. His wife asks you whether he really needs to keep coming to see you in renal clinic. |

||

| Disease-oriented approach | Individualized patient-centered approach | |

| Clinical Decision Making |

|

|

| Underlying conceptualization of disease |

|

|

| Treatment |

|

|

| Approach to symptoms |

|

|

| Goals of treatment |

|

|

GFR = glomerular filtration rate, CKD = chronic kidney disease, NSAID = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, ACE = angiotensin converting enzyme, UTI = urinary tract infection

Acknowledgements

Support: Support was through a Beeson Career Development Award from the NIA to Dr O’Hare and the Birmingham/Atlanta GRECC Special Fellowship in Advanced Geriatrics and John A. Hartford Foundation/Southeast Center of Excellence in Geriatric Medicine to Dr Bowling.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Coresh J. Conceptual model of CKD: applications and implications. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53(3 Suppl 3):S4–16. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tinetti ME, Fried T. The end of the disease era. Am J Med. 2004;116(3):179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uhlig K, Boyd C. Guidelines for the Older Adult With CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58(2):162–165. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodwin JS. Geriatrics and the limits of modern medicine. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(16):1283–1285. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904223401612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Kidney Foundation K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39(2 Suppl 1):S1–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Kidney Foundation K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for bone metabolism and disease in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42(4 Suppl 3):S1–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Kidney Foundation K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines on hypertension and antihypertensive agents in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43(5 Suppl 1):S1–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA. 2007;298(17):2038–2047. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.17.2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolff JL, Starfield B, Anderson G. Prevalence, expenditures, and complications of multiple chronic conditions in the elderly. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(20):2269–2276. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.20.2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jassal SV, Chiu E, Hladunewich M. Loss of independence in patients starting dialysis at 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(16):1612–1613. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0905289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strauss SE, Tinetti ME. Evaluation, Management, and Decision Making with the Older Patient. In: Halter JBOJ, Tinetti ME, Studenski S, High KP, Asthana S, editors. Hazzard’s Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology. 6e ed. McGraw-Hill; New York, NY: 2009. pp. 133–140. Chapter 10. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piette JD, Kerr EA. The impact of comorbid chronic conditions on diabetes care. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(3):725–731. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.03.06.dc05-2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ritchie C. Health care quality and multimorbidity: the jury is still out. Med Care. 2007;45(6):477–479. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318074d3c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, Fried LP, Boult L, Wu AW. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: implications for pay for performance. JAMA. 2005;294(6):716–724. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.6.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petersen RC, Parisi JE, Dickson DW, et al. Neuropathologic features of amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2006;63(5):665–672. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.5.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rule AD, Amer H, Cornell LD, et al. The association between age and nephrosclerosis on renal biopsy among healthy adults. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(9):561–567. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-9-201005040-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flacker JM. What is a geriatric syndrome anyway? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(4):574–576. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tinetti ME, Inouye SK, Gill TM, Doucette JT. Shared risk factors for falls, incontinence, and functional dependence. Unifying the approach to geriatric syndromes. JAMA. 1995;273(17):1348–1353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bowling CB, Sawyer P, Campbell RC, Ahmed A, Allman RM. Impact of chronic kidney disease on activities of daily living in community-dwelling older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66(6):689–694. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fried LF, Lee JS, Shlipak M, et al. Chronic kidney disease and functional limitation in older people: health, aging and body composition study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(5):750–756. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johansen KL, Chertow GM, Jin C, Kutner NG. Significance of frailty among dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18(11):2960–2967. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007020221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurella Tamura M, Yaffe K. Dementia and cognitive impairment in ESRD: diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. Kidney Int. 2011;79(1):14–22. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shlipak MG, Stehman-Breen C, Fried LF, et al. The presence of frailty in elderly persons with chronic renal insufficiency. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43(5):861–867. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2003.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilhelm-Leen ER, Hall YN, Kurella Tamura M, Chertow GM. Frailty and chronic kidney disease: the Third National Health and Nutrition Evaluation Survey. Am J Med. 2009;122(7):664–671.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walter LC, Covinsky KE. Cancer screening in elderly patients: a framework for individualized decision making. JAMA. 2001;285(21):2750–2756. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.21.2750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walter LC, Davidowitz NP, Heineken PA, Covinsky KE. Pitfalls of converting practice guidelines into quality measures: lessons learned from a VA performance measure. JAMA. 2004;291(20):2466–2470. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.20.2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kurella M, Covinsky KE, Collins AJ, Chertow GM. Octogenarians and nonagenarians starting dialysis in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(3):177–183. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-3-200702060-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gill TM, Allore HG, Hardy SE, Guo Z. The dynamic nature of mobility disability in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(2):248–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gill TM, Gahbauer EA, Han L, Allore HG. Trajectories of disability in the last year of life. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(13):1173–1180. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fried TR, Bradley EH, Towle VR, Allore H. Understanding the treatment preferences of seriously ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(14):1061–1066. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fried TR, Bradley EH. What matters to seriously ill older persons making end-of-life treatment decisions?: A qualitative study. J Palliat Med. 2003;6(2):237–244. doi: 10.1089/109662103764978489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fried TR, Van Ness PH, Byers AL, Towle VR, O’Leary JR, Dubin JA. Changes in preferences for life-sustaining treatment among older persons with advanced illness. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(4):495–501. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0104-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fried TR, Tinetti ME, Towle V, O’Leary JR, Iannone L. Effects of Benefits and Harms on Older Persons’ Willingness to Take Medication for Primary Cardiovascular Prevention. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(10):923–8. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xi W, Harwood L, Diamant MJ, et al. Patient attitudes towards the arteriovenous fistula: a qualitative study on vascular access decision making [published online ahead of print March 15, 2011] Nephrol Dial Transplant. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr055. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heiat A, Gross CP, Krumholz HM. Representation of the elderly, women, and minorities in heart failure clinical trials. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(15):1682–1688. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.15.1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee PY, Alexander KP, Hammill BG, Pasquali SK, Peterson ED. Representation of elderly persons and women in published randomized trials of acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2001;286(6):708–713. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.6.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Spall HG, Toren A, Kiss A, Fowler RA. Eligibility criteria of randomized controlled trials published in high-impact general medical journals: a systematic sampling review. JAMA. 2007;297(11):1233–1240. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.11.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gerstein HC, Miller ME, Byington RP, et al. Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(24):2545–2559. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rahman M, Pressel S, Davis BR, et al. Renal outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients treated with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or a calcium channel blocker vs a diuretic: a report from the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(8):936–946. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.8.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coca SG, Krumholz HM, Garg AX, Parikh CR. Underrepresentation of renal disease in randomized controlled trials of cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2006;296(11):1377–1384. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.11.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O’Hare AM, Kaufman JS, Covinsky KE, Landefeld CS, McFarland LV, Larson EB. Current guidelines for using angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II-receptor antagonists in chronic kidney disease: is the evidence base relevant to older adults? Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(10):717–724. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-10-200905190-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Upadhyay A, Earley A, Haynes SM, Uhlig K. Systematic review: blood pressure target in chronic kidney disease and proteinuria as an effect modifier. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(8):541–548. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-8-201104190-00335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tinetti ME, Studenski SA. Comparative effectiveness research and patients with multiple chronic conditions. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(26):2478–2481. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1100535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1296–1305. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hemmelgarn BR, Manns BJ, Lloyd A, et al. Relation between kidney function, proteinuria, and adverse outcomes. JAMA. 2010;303(5):423–429. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matsushita K, van der Velde M, Astor BC, et al. Association of estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in general population cohorts: a collaborative meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375(9731):2073–2081. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60674-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Culleton B, et al. Chronic kidney disease and mortality risk: a systematic review. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(7):2034–2047. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005101085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Levey AS, de Jong PE, Coresh J, et al. The definition, classification and prognosis of chronic kidney disease: a KDIGO Controversies Conference report. Kidney Int. 2011;80(1):17–28. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tonelli M, Muntner P, Lloyd A, et al. Using proteinuria and estimated glomerular filtration rate to classify risk in patients with chronic kidney disease: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(1):12–21. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-1-201101040-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Conway B, Webster A, Ramsay G, et al. Predicting mortality and uptake of renal replacement therapy in patients with stage 4 chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(6):1930–1937. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.O’Hare AM, Bertenthal D, Covinsky KE, et al. Mortality risk stratification in chronic kidney disease: one size for all ages? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(3):846–853. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005090986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O’Hare AM, Choi AI, Bertenthal D, et al. Age Affects Outcomes in Chronic Kidney Disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18(10):2758–2765. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007040422. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Raymond NT, Zehnder D, Smith SC, Stinson JA, Lehnert H, Higgins RM. Elevated relative mortality risk with mild-to-moderate chronic kidney disease decreases with age. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22(11):3214–3220. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roderick PJ, Atkins RJ, Smeeth L, et al. CKD and mortality risk in older people: a community-based population study in the United Kingdom. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53(6):950–960. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tangri N, Stevens LA, Griffith J, et al. A predictive model for progression of chronic kidney disease to kidney failure. JAMA. 2011;305(15):1553–1559. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]