Abstract

Objective

Little is known about genetic contributors to higher than usual warfarin dose requirements, particularly for African Americans. This study tested the hypothesis that the γ-glutamyl carboxylase (GGCX) genotype contributes to warfarin dose requirements >7.5 mg/day in an African American population.

Methods

A total of 338 African Americans on a stable dose of warfarin were enrolled. The GGCX rs10654848 (CAA)n, rs12714145 (G>A), and rs699664 (p.R325Q); VKORC1 c.-1639G>A and rs61162043; and CYP2C9*2, *3, *5, *8, *11, and rs7089580 genotypes tested for their association with dose requirements >7.5 mg/day alone and in the context of other variables known to influence dose variability.

Results

The GGCX rs10654848 (CAA) 16 or 17 repeat occurred at a frequency of 2.6% in African Americans and was overrepresented among patients requiring >7.5mg/day versus those who required lower doses (12% vs 3%, p=0.003; odds ratio 4.0, 95% CI, 1.5–10.5). The GGCX rs10654848 genotype remained associated with high dose requirements on regression analysis including age, body size, and VKORC1 genotype. On linear regression, the GGCX rs10654848 genotype explained 2% of the overall variability in warfarin dose in African Americans. An examination of the GGCX rs10654848 genotype in warfarin-treated Caucasians revealed a (CAA)16 repeat allele frequency of only 0.27% (p=0.008 compared to African Americans).

Conclusion

These data support the GGCX rs10654848 genotype as a predictor of higher than usual warfarin doses in African Americans, who have a 10-fold higher frequency of the (CAA)16/17 repeat compared to Caucasians.

Keywords: African American, GGCX, warfarin

Introduction

Warfarin is the most widely prescribed oral agent for the prophylaxis of thromboembolic events. Subtherapeutic warfarin dosing increases the risk for thromboembolism, particularly during the initial months of therapy [1, 2]. Thus, obtaining therapeutic anticoagulation in a timely manner is a priority for clinicians managing warfarin.

Clinical factors are well known to influence the dose of warfarin required to produce therapeutic anticoagulation, with higher doses often necessary in those who are young, obese, taking medications that induce warfarin metabolism, or consuming large amounts of vitamin K-containing foods [3, 4]. More recently, the genotypes for cytochrome P450 2C9 (CYP2C9) and vitamin K epoxide reductase complex 1 (VKORC1) have been shown to affect warfarin pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, respectively[5, 6]. The CYP2C9 enzyme metabolizes the more potent S-enantiomer of warfarin, while VKORC1 is the protein target of warfarin. Common CYP2C9 and VKORC1 variants have been associated with warfarin dose requirements across populations [7–12]. In particular, the CYP2C9*2, CYP2C9*3, and VKORC1 -1639G>A variants were identified as major contributors to warfarin dose requirements within the usual range of 0.5 mg to 7.5 mg per day, especially in Caucasian and Asian populations [13–15].

In 2010, the United States Food and Drug Administration approved revision of the warfarin labeling to include dosing recommendations based on the CYP2C9*2, CYP2C9*3, and VKORC1 -1639G>A variants, with recommended doses falling within the range of 0.5 to 7 mg/day [16]. Many patients require warfarin doses higher than 7 mg/day; yet, little is known about variants that contribute to higher than usual warfarin doses. This is particularly true in African Americans, who generally require higher doses than those of other racial groups.[4, 17]

The gene encoding γ-glutamyl carboxylase (GGCX) is an additional candidate for influencing warfarin pharmacodynamics. The GGCX enzyme catalyzes the biosynthesis of vitamin K-dependent clotting factors by carboxylating protein-bound glutamate residues. Warfarin exerts its anticoagulant effects by inhibiting the regeneration of a reduced form of vitamin K, which is essential for γ-carboxylation and activation of clotting factors II, VII, IX, and X. Rare GGCX mutations cause deficiencies in vitamin K-dependent clotting factors.[18] There are also data that more common GGCX variants influence warfarin dose variability in the general population [19–21]. Specifically, the rs699664 (p.R325Q) single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in exon 8, rs12714145 SNP in intron 2, and rs10654848 microsatellite in intron 6 have been associated with higher warfarin dose requirements in Caucasians and Asians [19–21]. We tested the hypothesis that the GGCX rs699664, rs12714145, and rs10654848 variants contribute to higher than usual warfarin dose requirements in African Americans. The GGCX rs11676382 SNP was recently associated with reduced warfarin dose requirements in European Caucasians [22]. However, it is reported to occur in less than 3% of African Americans, and thus was not included in our analysis [22, 23].

Methods

African American population and procedures

The patient population and procedures have been previously described [9, 24]. Briefly, 338 African Americans ≥18 years of age, on stable warfarin therapy, defined as the same warfarin dose for ≥3 consecutive clinic visits, were recruited from the anticoagulation clinics at the University of Illinois Medical Center at Chicago (n=241) and the University of Chicago (n=97). Race was determined based on self-report, and none of the subjects reported mixed ethnicity. One patient required a warfarin dose of 215 mg/week and was excluded from further analysis because such high dose requirements are often due to rare mutations associated with warfarin resistance rather than common variants associated with higher than usual doses in the general population [25]. After obtaining written informed consent, a buccal cell or whole blood sample was obtained for genetic analysis, and clinical data were collected. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each location.

Genotyping

African Americans were genotyped for the CYP2C9 rs1799853 (p.R144C, *2), rs1057910 (p.I359L, *3), rs28371686 (p.D360E, *5), rs7900194 (p.R150H, *8), and rs28371685 (p.R335W, *11) alleles; VKORC1 rs9923231 (c.-1639G>A) variant, and recently described CYP2C9 rs7089580 and VKORC1 rs61162043 variants, using previously published methods.[24, 26, 27]. The GGCX rs12714145 (G>A) and rs699664 (p.R325Q) variants were determined by PCR and pyrosequencing, using published methods except with an annealing temperature of 58°C and primers shown in Table 1[26, 27]. The GGCX rs10654848 (CAA)n genotype was determined by fragment analysis because of the difficulty with detecting heterozygous genotypes with sequencing. Thermocycling consisted of denaturation for 15 minutes at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 45 seconds, annealing at 55°C for 45 seconds, and extension at 72°C for 1 minute, with a final extension of 72°C for 10 minutes. The fragment analysis was performed using PCR product combined with GeneScan™ 1200 LIZ® Size Standard (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies Corp, Carlsbad, CA) and Hi-Di™ Formamide (Applied Biosystems) on an ABI 3730x1 DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). The results were analyzed using GeneMapper® v3.7 (Applied Biosystems). The number of GGCX CAA repeats was determined by capillary sequencing of at least one sample of each fragment size. Because of their high minor allele frequencies (>0.40), the determination of the GGCX rs12714145 and rs699664 SNPs was restricted to African Americans enrolled from UIC. Given the large number of CAA repeats, with some having relatively low frequencies, we determined the GGCX (CAA) genotype in African Americans enrolled from both sites.

Table 1.

PCR and sequencing primers for GGCX variants

| Variant | Primers (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|

| GGCX rs12714145 (G>A) | PCR Forward: TAGGGAGTCACAGCCAAAAGGTA |

| PCR Reverse: Biotin-TTGCCCAGAAGACTCAGAGAAA | |

| Sequencing: CTGTGGCCCCCTGCT | |

| GGCX rs10654848 (CAA)n | PCR Forward: FAM-ACTCCCAAACAATGCCTCTG |

| PCR Reverse: AGGAGATCTGCCCTTGCTTA | |

| Sequencing: ACTCCCAAACAATGCCTCTG | |

| GGCX rs699664 (p.R325Q) | PCR Forward: Biotin-AGTGGCCTCGGAAGCTGGT |

| PCR Reverse: ACACAGGAAACACTGGGCTGAG | |

| Sequencing: ACAGTTGTTGCAACCT |

Swedish population

A total of 183 Swedish warfarin-treated patients were enrolled from Uppsala University Hospital anticoagulation clinic and genotyped for the GGCX rs10654848 (CAA)n repeat in order to compare frequencies of the CAA repeat between African Americans and European Caucasians. Patient characteristics, sample collection, and genotyping have been previously described [20, 28].

Data analysis

Median weekly warfarin dose requirements were compared between GGCX genotype groups among African Americans by the Mann Whitney U test. Warfarin doses were initially compared among GGCX rs10654848 (CAA)n alleles to determine which alleles produced similar effects on dose and could be combined for comparisons between high and usual dose groups. Clinical factors and genotype frequencies were then compared between African Americans requiring ≤7.5 mg/day (usual dose group) and >7.5 mg/day (high dose group) of warfarin to maintain therapeutic anticoagulation by χ2 analysis or the Fischer’s Exact test, as appropriate for nominal data, or the Student’s unpaired t-test for continuous data. The 7.5 mg/day cutoff was chosen because the CYP2C9 and VKORC1 variants predict doses up to 7.5 mg/day,[8, 11] but little is known about genetic variable predicting doses >7.5 mg/day. Factors potentially associated with dose requirements >7.5 mg/day on univariate analysis (p<0.10) were entered into a logistic regression model to determine joint contributions to warfarin dose requirements >7.5 mg/day. The regression model was tested in a stepwise non-automated manner. Genotypes were entered into the model first, with the presence or absence of a variant allele coded as “1” and “0,” respectively. Each clinical variable was then entered into the model one at a time. Variables significantly associated with dose (p<0.05) were retained in the model.

Finally, a stepwise linear regression model was used to determine the contribution of the GGCX genotype to warfarin dose requirements in the African American population. Genotypes were coded as “1” or “0” for CYP2C9 and VKORC1, as described above, based on the presence or absence of a variant allele. Genotype for GGCX rs10654848 was coded as 0 for the 10/(8–10) genotype, 2 for genotypes containing the 16 or 17 repeat, and 1 for all other genotypes (11–15/8–15). Warfarin dose was non-normally distributed (p<0.01 by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test) and was thus log transformed for this analysis. The adjusted R2 after entry of each genotype provides an indication of the genotypes’s relative contribution to warfarin dose requirements.

Results

The mean age of the African American population was 58 ± 16 years, and 71% were female. The mean warfarin dose was 6.4 ± 2.6 mg/day [median (range) 6.0 (1.6 to 15.7) mg/day]. Eighty-six (25%) patients required a warfarin dose >7.5 mg/day to maintain an INR within the target range.

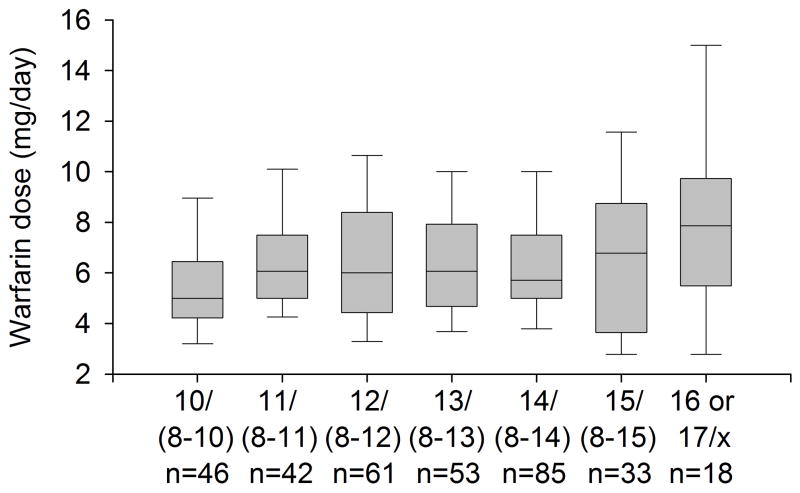

Allele frequencies in the African American cohort are shown in Table 2. For the GGCX rs10654848(CAA) genotype, we detected 8 to 17 CAA repeats. Similar to other populations, the (CAA)10 repeat was most common [20, 29, 30]. However, the (CAA) 14, 15, and 16 repeat occurred at higher frequencies than previously reported in other populations [30, 31]. Eighteen patients (5%) carried a 16 or 17 repeat; 17 were heterozygous for the 16 repeat, and one was heterozygous for the 17 repeat (14/17 genotype). Genotype frequencies are shown in supplementary table 1. As shown in figure 1 and table 3, dose requirements varied by the number of CAA repeats, with higher requirements with genotypes containing the 16 or 17 repeat and lower doses with the 10/(8–10) genotype compared to other genotypes. There was no association between the GGCX rs699664 or rs12714145 genotype and warfarin maintenance dose.

Table 2.

Minor allele frequencies for CYP2C9, VKORC1, and GGCX variants in African Americans

| Allele | No. | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| CYP2C9*2 | 15/676 | 0.022 |

| CYP2C9*3 | 5/676 | 0.007 |

| CYP2C9*5 | 5/676 | 0.007 |

| CYP2C9*8 | 49/674 | 0.072 |

| CYP2C9*11 | 13/674 | 0.019 |

| CYP2C9 rs7089580 | 96/468 | 0.205 |

| VKORC1 -1639 A | 66/676 | 0.098 |

| VKORC1 rs61162043 | 233/482 | 0.483 |

| GGCX rs699664 G (325R) | 184/416 | 0.442 |

| GGCX rs12714145 A | 173/422 | 0.410 |

| GGCX rs10654848 (CAA)n | ||

| 8 | 14/676 | 0.021 |

| 9 | 1/676 | 0.001 |

| 10 | 224/676 | 0.331 |

| 11 | 94/676 | 0.139 |

| 12 | 119/676 | 0.176 |

| 13 | 80/676 | 0.118 |

| 14 | 92/676 | 0.136 |

| 15 | 34/676 | 0.050 |

| 16 | 17/676 | 0.025 |

| 17 | 1/676 | 0.001 |

Figure 1. Warfarin dose requirements according to the GGCX rs10654848 (CAA)n genotype.

Lines within boxes represent medians. The lower and upper boundaries of the boxes mark the 25th and 75th percentiles, and the whiskers below and above the boxes indicated the 10th and 90th percentiles.

Table 3.

Therapeutic warfarin dose by GGCX genotype

| Genotype | n | Median (IQR) dose (mg/day) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| GGCX rs699664 R325Q | |||

| RR | 46 | 5.6 (4.9–7.4) | |

| RQ | 92 | 5.8 (4.8–7.5) | 0.911 |

| 70 | 6.0 (4.3–8.5) | ||

| GGCX rs12714145 G>A | |||

| GG | 71 | 5.7 (4.6–7.5) | |

| AG | 107 | 5.7 (4.4–7.9) | 0.954 |

| AA | 33 | 5.9 (4.3–7.5) | |

| GCX rs10654848 (CAA)n | |||

| ≤10 repeats* | 46 | 5.0 (4.3–6.4) | |

| 11–15 repeats† | 274 | 6.0 (4.6–7.5) | 0.022 |

| 16–17 repeats | 18 | 7.9 (6.1–9.5) | |

Refers for patients with no more than 10 repeats for either allele (8/10 or 10/10 genotypes)

Refers to patients with 11 to 15 repeats for at least one allele (8/11 through 15/15 genotypes)

Characteristics of African Americans requiring usual and high warfarin doses are shown in Table 4. As expected, patients taking higher doses were younger and of larger body size. Of the genotypes tested, the VKORC1 -1639GG genotype, VKORC1 rs66162043 G allele, and GGCX (CAA)16/17 repeat were significantly overrepresented in the high dose group. The odds ratio for the association between the GGCX (CAA)16/17 repeat and dose requirements >7.5 mg/day was 4.0 (95% confidence interval 1.5–10.5). On logistic regression, age, body surface area (BSA), VKORC1 rs66162043 genotype, and GGCX (CAA)n genotype remained associated with doses >7.5 mg/day, while the association with the VKORC1 -1639GG genotype no longer reached statistical significance (Table 5).

Table 4.

Characteristics of African Americans requiring ≤7.5 mg/day and >7.5 mg/day of warfarin

| Characteristic | Dose no higher than 7.5 mg/day (n=252) | Dose greater than 7.5 mg/day (n=86) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 61 ± 15 | 49 ± 14 | <0.001 |

| BSA, m2 | 2.0 ± 0.3 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | <0.001 |

| Amiodarone use | 8 (3) | 1 (1) | 0.458 |

| CYP2C9 inducer use* | 4 (2) | 4 (5) | 0.211 |

| CYP2C9*2, *3, *5, *8, or *11 allele | 62 (25) | 14 (16) | 0.110 |

| CYP2C9 rs7089580 AT or TT† | 90 (37) | 36 (42) | 0.358 |

| VKORC1 -1639GG genotype | 198 (79) | 77 (90) | 0.024 |

| VKORC1 rs61162043 GA or GG‡ | 183 (73) | 71 (84) | 0.044 |

| GGCX rs10654848 (CAA) 16 or 17 | 8 (3) | 10 (12) | 0.005 |

| GGCX rs12714145δ | |||

| GG | 54 (34) | 17 (31) | |

| GA | 78 (50) | 29 (54) | 0.878 |

| AA | 25 (16) | 8 (15) | |

| GGCX rs699664|| | |||

| RR | 36 (23) | 10 (19) | |

| RQ | 71 (46) | 21 (40.5) | 0.490 |

| 49 (31) | 21 (40.5) | ||

BSA, body surface area;

CYP2C9 inducer use was only available for University of Illinois at Chicago cohort.

CYP2C9 rs7089580 genotype available for 330 patients

VKORC1 rs61162043 genotype available for 337 patients

GGCX rs12714145 genotype was available for 211 patients.

GGCX rs699664 was available for 208 patients.

Table 5.

Parameter estimates for factors associated with warfarin dose requirements >7.5 mg/day on logistic regression

| Variables | P | Estimate | Standard error | Odds ratio | 95% Confidence interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <0.001 | −0.051 | 0.010 | — | — |

| BSA | <0.001 | 1.610 | 0.453 | — | — |

| GGCX (CAA)16/17 repeat | 0.017 | 1.399 | 0.586 | 4.05 | 1.28–12.82 |

| VKORC1 -1639 GG | 0.133 | 0.671 | 0.447 | 1.96 | 0.81–4.69 |

| VKORC1 rs61162043 | 0.041 | 0.774 | 0.379 | 2.17 | 1.03–4.56 |

BSA, body surface area

For the linear regression model of genetic factors associated with log warfarin dose in African Americans, the GGCX (CAA)n genotype was the first variable entered in order to capture the variability explained by this variant alone (Table 6). The GGCX (CAA)n microsatellite explained 2% of the variability in warfarin dose in the study population (adjusted R2). Next, we tested whether the GGCX (CAA)n genotype contributed to warfarin dose variability beyond that of SNPs included in the warfarin labeling. The addition of the CYP2C9*2 or *3 and VKORC1 -1639G>A genotypes increased the genetic contribution to warfarin dose variability to 10%. Consideration of the CYP2C9*5, *8, and *11 alleles increased the contribution to dose variability explained by genetic factors to 14%, with GGCX (CAA)n remaining a significant contributor (p=0.047). The GGCX (CAA)n genotype also remained associated with warfarin dose variability when accounting for the novel VKORC1 rs61162043 and CYP2C9 rs7089580 variants (data not shown).

Table 6.

Linear regression model of genetic factors jointly associated with log warfarin dose requirements in African Americans

| Entry into model | Variable | Adjusted R2 after entry | Standardized Coefficient | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | GGCX (CAA) genotype* | 0.018 | 0.102 | 0.022 |

| 2 | VKORC1 -1639 G>A | 0.090 | 0.269 | <0.001 |

| 3 | CYP2C9 *2 or *3 variant | 0.099 | −0.109 | 0.038 |

GGCX genotypes were coded as 0 for 10/(8–10) genotype, 2 for 16 or 17 repeat, and 1 for all other genotypes (11–15/8–15).

Similar to African Americans, the (CAA)10 repeat was the most common allele in the Swedish population (frequency 0.511, supplementary table 2). The (CAA)11, 13, 14, and 15 repeat frequencies were 0.145, 0.246, 0.093, and 0.003, respectively. The (CAA)9, 12, and 17 repeats were not observed. The (CAA)16 repeat was significantly less common in Swedish compared to African American patients (p=0.008); a single Caucasian male had the 10/16 genotype (frequency 0.003). Interestingly, this patient had a warfarin maintenance dose of 76.5 mg/week despite having the CYP2C9*1/*2 genotype and taking amiodarone, both of which are expected to lower the dose.

Discussion

Rare mutations in the VKORC1 gene have been associated with the warfarin resistance phenotype, where doses of 20 mg/day or higher are necessary to achieve therapeutic anticoagulation [32]. More recently, the ABCB1 3435C>T variant was associated with warfarin resistance in a Brazilian population [33]. In contrast, common VKORC1 as well as CYP2C9 SNPs correlate with the usual warfarin dose variability that occurs in the general population. In particular, the VKORC1 -1639G>A, CYP2C9*2 and CYP2C9*3 SNPs explain much of the variability (approximately 30% in Caucasians and 10% in African Americans) in warfarin dose within the range of 0.5 mg/day to 7.5 mg/day [8, 10, 11, 34]. African Americans generally require higher warfarin doses than those of other racial groups, and a significant portion of African Americans (25% in the current study) require doses >7.5 mg/day [10]. Lower frequencies of the CYP2C9*2, CYP2C9*3 and VKORC1 -1639A alleles among African Americans compared to Caucasians contribute to the higher warfarin doses generally required in the former racial group [10]. In addition, the CYP2C9 rs7089580 and VKORC1 rs61162043 variants were recently found to occur frequently in African Americans and contribute to higher dose requirements in this population[24]. However, as demonstrated in the current study, the CYP2C9 and VKORC1 -1639A genotypes do not explain warfarin dose requirements above the usual dose range after accounting for other factors associated with high dose requirements. In the absence of mutations contributing to warfarin resistance, little is known about genetic contributors to higher than usual warfarin doses.

We found a significant association between the GGCX rs10654848 (CAA)n polymorphism and warfarin dose requirements >7.5 mg/day. In particular, 4 times as many patients requiring >7.5 mg/day of warfarin possessed a (CAA) 16 or 17 repeat compared to those requiring lower doses. While only 5% of our patients had a (CAA) 16 or 17 repeat, this was significantly higher than in the Swedish comparative cohort in our study. The higher prevalence of these alleles among African Americans may explain, in part, higher dose requirements observed in the African American population. The GGCX (CAA)n genotype was also associated with warfarin dose variability across our entire study population, but explained only a small portion of the total variability, likely because of its relatively low frequency.

While candidate gene studies in European Caucasian and Japanese patients have also implicated the GGCX (CAA)n repeat as a contributor to warfarin dose requirements, the data are inconsistent. Specifically, only the (CAA)10, 11, and 13 repeats were detected in an initial study in a Japanese population [29]. Three patients carried the (CAA)13 repeat and required significantly higher doses compared to those without this repeat. A more recent study revealed that the (CAA)8, 12, 14, and 15 (but not 16 or 17) repeats also occur in the Japanese population, but at low frequencies (<0.02) [31]. That study failed to replicate the previously observed association between the (CAA)13 repeat and warfarin dose. Dose requirements by the (CAA)n repeat were previously described in the Swedish population included in this study. Patients who were either homozygous for 13 repeats or carried at least one 14 to 16 repeat required higher dose requirements [20]. Another group of investigators also reported a correlation between number of CAA repeats and warfarin dose requirements; however, results were only significant in CYP2C9*1 allele homozygotes [35]. In the most recent study in Caucasians, only the (CAA)10, 11, 13, and 14 repeats were described [30]. In contrast to previous data, a higher number of repeats was associated with a lower warfarin dose in this population. None of the genome-wide association studies conducted to date identified the GGCX genotype as a major contributor to warfarin dose variability.[13–15] However, these studies were limited to Caucasian and Japanese patients, in whom the (CAA)16 and 17 repeats are rare to absent.

Neither the GGCX rs699664 nor rs12714145 variant was associated with higher warfarin dose requirements in our study. While the rs699664 SNP was correlated with warfarin dose in a Japanese population [19], it was not associated with dose requirements in several different cohorts of European Caucasians [21, 30, 35–37]. Thus our negative finding with the rs699664 variant is consistent with the majority of previous data. Data with the rs12714145 variant have been inconsistent. However, in most studies, the rs12714145 SNP either explained only a small portion of the variability in warfarin dose or had no effect at all [21, 22, 30, 38].

The mechanism by which the GGCX (CAA) repeat influences warfarin dose requirements has not been elucidated. Based on higher dose requirements with the 16 or 17 repeat, it seems plausible that higher repeats may enhance enzyme activity leading to greater carboxylation of clotting factors, which would presumably increase warfarin dose requirements. However, this remains to be determined. Also, the inconsistencies in the data regarding the GGCX (CAA) repeat association with warfarin dose in other populations remain to be resolved, but could be secondary to near absence of the (CAA) 16 or 17 repeat in non-African populations.

In summary, we found that the GGCX rs10654848 (CAA) 16 or 17 repeat is significantly more common in African Americans compared to Caucasians and is associated warfarin dose requirements >7.5 mg/day. Current guidelines for anticoagulation management recommend warfarin starting doses of 5 mg/day for most patients, with lower doses in the elderly or those taking medications that reduce warfarin metabolism [3, 39]. The warfarin labeling suggests further dose adjustments based on the CYP2C9 and VKORC1 genotypes [16]. However, recommended doses fall within the range of 0.5 mg/day to 7 mg/day. Our data suggest that limiting starting doses within this range may result in under-dosing approximately 5% of African Americans who carry a (CAA) 16 or 17 repeat, thus potentially delaying their time to achieve therapeutic anticoagulation. Rather, our data suggest that, while the GGCX (CAA) repeat provides only a modest (2%) overall contribution to warfarin dose variability, it may be useful in identifying select African Americans who will require higher than usual doses. African Americans are at particularly high risk for poor outcomes as a result of sub-therapeutic anticoagulation, with greater stroke-related disability and higher mortality rates from stroke and pulmonary embolism compared to Caucasians [40–42]. Thus, achieving therapeutic anticoagulation efficiently is especially important for persons of African American race.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest and Source of Funding: This work was supported by grants from the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy New Investigator Award and the University of Illinois at Chicago College of Pharmacy Hans Vahlteich Research Award (L.H.C.); the National Institutes of Health (grant K23 HL089808-01A2, M.P.); the Swedish Research Council, Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation, and Clinical Research Support (ALF) at Uppsala University (M.W); and the Wellcome Trust (P.D.). None of the authors declare any competing conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Hylek EM, Go AS, Chang Y, Jensvold NG, Henault LE, Selby JV, et al. Effect of intensity of oral anticoagulation on stroke severity and mortality in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1019–1026. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Monreal M, Roncales FJ, Ruiz J, Muchart J, Fraile M, Costa J, et al. Secondary prevention of venous thromboembolism: A role for low-molecular-weight heparin. Haemostasis. 1998;28:236–243. doi: 10.1159/000022437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ansell J, Hirsh J, Hylek E, Jacobson A, Crowther M, Palareti G. Pharmacology and management of the vitamin K antagonists: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition) Chest. 2008;133:160S–198S. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Absher RK, Moore ME, Parker MH. Patient-specific factors predictive of warfarin dosage requirements. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36:1512–1517. doi: 10.1345/aph.1C025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scordo MG, Pengo V, Spina E, Dahl ML, Gusella M, Padrini R. Influence of CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 genetic polymorphisms on warfarin maintenance dose and metabolic clearance. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2002;72:702–710. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2002.129321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang D, Chen H, Momary KM, Cavallari LH, Johnson JA, Sadee W. Regulatory polymorphism in vitamin K epoxide reductase complex subunit 1 (VKORC1) affects gene expression and warfarin dose requirement. Blood. 2008;112:1013–1021. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-144899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Higashi MK, Veenstra DL, Kondo LM, Wittkowsky AK, Srinouanprachanh SL, Farin FM, et al. Association between CYP2C9 genetic variants and anticoagulation-related outcomes during warfarin therapy. JAMA. 2002;287:1690–1698. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.13.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rieder MJ, Reiner AP, Gage BF, Nickerson DA, Eby CS, McLeod HL, et al. Effect of VKORC1 haplotypes on transcriptional regulation and warfarin dose. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2285–2293. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cavallari LH, Langaee TY, Momary KM, Shapiro NL, Nutescu EA, Coty WA, et al. Genetic and clinical predictors of warfarin dose requirements in African Americans. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;87:459–464. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Limdi NA, Wadelius M, Cavallari L, Eriksson N, Crawford DC, Lee MT, et al. Warfarin pharmacogenetics: a single VKORC1 polymorphism is predictive of dose across 3 racial groups. Blood. 2010;115:3827–3834. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-255992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klein TE, Altman RB, Eriksson N, Gage BF, Kimmel SE, Lee MT, et al. Estimation of the warfarin dose with clinical and pharmacogenetic data. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:753–764. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wadelius M, Chen LY, Lindh JD, Eriksson N, Ghori MJ, Bumpstead S, et al. The largest prospective warfarin-treated cohort supports genetic forecasting. Blood. 2009;113:784–792. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-149070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooper GM, Johnson JA, Langaee TY, Feng H, Stanaway IB, Schwarz UI, et al. A genome-wide scan for common genetic variants with a large influence on warfarin maintenance dose. Blood. 2008;112:1022–1027. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-134247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takeuchi F, McGinnis R, Bourgeois S, Barnes C, Eriksson N, Soranzo N, et al. A genome-wide association study confirms VKORC1, CYP2C9, and CYP4F2 as principal genetic determinants of warfarin dose. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000433. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cha PC, Mushiroda T, Takahashi A, Kubo M, Minami S, Kamatani N, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies genetic determinants of warfarin responsiveness for Japanese. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;19:4735–4744. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coumadin (warfarin sodium) package insert. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb; 2010. Jan, [Google Scholar]

- 17.Limdi NA, Beasley TM, Crowley MR, Goldstein JA, Rieder MJ, Flockhart DA, et al. VKORC1 polymorphisms, haplotypes and haplotype groups on warfarin dose among African-Americans and European-Americans. Pharmacogenomics. 2008;9:1445–1458. doi: 10.2217/14622416.9.10.1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rost S, Fregin A, Koch D, Compes M, Muller CR, Oldenburg J. Compound heterozygous mutations in the gamma-glutamyl carboxylase gene cause combined deficiency of all vitamin K-dependent blood coagulation factors. Br J Haematol. 2004;126:546–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimura R, Miyashita K, Kokubo Y, Akaiwa Y, Otsubo R, Nagatsuka K, et al. Genotypes of vitamin K epoxide reductase, gamma-glutamyl carboxylase, and cytochrome P450 2C9 as determinants of daily warfarin dose in Japanese patients. Thromb Res. 2007;120:181–186. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen LY, Eriksson N, Gwilliam R, Bentley D, Deloukas P, Wadelius M. Gamma-glutamyl carboxylase (GGCX) microsatellite and warfarin dosing. Blood. 2005;106:3673–3674. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wadelius M, Chen LY, Downes K, Ghori J, Hunt S, Eriksson N, et al. Common VKORC1 and GGCX polymorphisms associated with warfarin dose. Pharmacogenomics J. 2005;5:262–270. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.King CR, Deych E, Milligan P, Eby C, Lenzini P, Grice G, et al. Gamma-glutamyl carboxylase and its influence on warfarin dose. Thromb Haemost. 2010;104:750–754. doi: 10.1160/TH09-11-0763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Database of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (dbSNP) Bethesda (MD): National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine; dbSNP accession: ss147640006, ss52069384 (dbSNP Build ID:132). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/ [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perera MA, Gamazon E, Cavallari LH, Patel SR, Poindexter S, Kittles RA, et al. The missing association: sequencing-based discovery of novel SNPs in VKORC1 and CYP2C9 that affect warfarin dose in African Americans. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89:408–415. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rost S, Fregin A, Ivaskevicius V, Conzelmann E, Hortnagel K, Pelz HJ, et al. Mutations in VKORC1 cause warfarin resistance and multiple coagulation factor deficiency type 2. Nature. 2004;427:537–541. doi: 10.1038/nature02214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hruska MW, Frye RF, Langaee TY. Pyrosequencing method for genotyping cytochrome P450 CYP2C8 and CYP2C9 enzymes. Clin Chem. 2004;50:2392–2395. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.040071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cavallari LH, Butler C, Langaee TY, Wardak N, Patel SR, Viana MAG, et al. Association of apolipoprotein E genotype with duration of time to achieve a stable warfarin dose in African-American patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2011;31:785–792. doi: 10.1592/phco.31.8.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wadelius M, Sorlin K, Wallerman O, Karlsson J, Yue QY, Magnusson PK, et al. Warfarin sensitivity related to CYP2C9, CYP3A5, ABCB1 (MDR1) and other factors. Pharmacogenomics J. 2004;4:40–48. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shikata E, Ieiri I, Ishiguro S, Aono H, Inoue K, Koide T, et al. Association of pharmacokinetic (CYP2C9) and pharmacodynamic (factors II, VII, IX, and X; proteins S and C; and gamma-glutamyl carboxylase) gene variants with warfarin sensitivity. Blood. 2004;103:2630–2635. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rieder MJ, Reiner AP, Rettie AE. Gamma-glutamyl carboxylase (GGCX) tagSNPs have limited utility for predicting warfarin maintenance dose. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:2227–2234. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cha PC, Mushiroda T, Takahashi A, Saito S, Shimomura H, Suzuki T, et al. High-resolution SNP and haplotype maps of the human gamma-glutamyl carboxylase gene (GGCX) and association study between polymorphisms in GGCX and the warfarin maintenance dose requirement of the Japanese population. J Hum Genet. 2007;52:856–864. doi: 10.1007/s10038-007-0183-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harrington DJ, Gorska R, Wheeler R, Davidson S, Murden S, Morse C, et al. Pharmacodynamic resistance to warfarin is associated with nucleotide substitutions in VKORC1. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6:1663–1670. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Oliveira Almeida VC, De Souza Ferreira AC, Ribeiro DD, Gomes Borges KB, Salles Moura Fernandes AP, Brunialti Godard AL. Association of the C3435T polymorphism of the MDR1 gene and therapeutic doses of warfarin in thrombophilic patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:2120–2122. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Limdi NA, Arnett DK, Goldstein JA, Beasley TM, McGwin G, Adler BK, et al. Influence of CYP2C9 and VKORC1 on warfarin dose, anticoagulation attainment and maintenance among European-Americans and African-Americans. Pharmacogenomics. 2008;9:511–526. doi: 10.2217/14622416.9.5.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herman D, Peternel P, Stegnar M, Breskvar K, Dolzan V. The influence of sequence variations in factor VII, gamma-glutamyl carboxylase and vitamin K epoxide reductase complex genes on warfarin dose requirement. Thromb Haemost. 2006;95:782–787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Loebstein R, Vecsler M, Kurnik D, Austerweil N, Gak E, Halkin H, et al. Common genetic variants of microsomal epoxide hydrolase affect warfarin dose requirements beyond the effect of cytochrome P450 2C9. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005;77:365–372. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vecsler M, Loebstein R, Almog S, Kurnik D, Goldman B, Halkin H, et al. Combined genetic profiles of components and regulators of the vitamin K-dependent gamma-carboxylation system affect individual sensitivity to warfarin. Thromb Haemost. 2006;95:205–211. doi: 10.1160/TH05-06-0446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang SW, Xiang DK, Huang L, Chen BL, An BQ, Li GF, et al. Influence of GGCX genotype on warfarin dose requirements in Chinese patients. Thromb Res. 2011;127:131–134. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2010.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hirsh J, Fuster V, Ansell J, Halperin JL. American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Foundation guide to warfarin therapy. Circulation. 2003;107:1692–1711. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000063575.17904.4E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, Carnethon M, Dai S, De Simone G, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121:e46–e215. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.White RH, Dager WE, Zhou H, Murin S. Racial and gender differences in the incidence of recurrent venous thromboembolism. Thromb Haemost. 2006;96:267–273. doi: 10.1160/TH06-07-0365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schneider D, Lilienfeld DE, Im W. The epidemiology of pulmonary embolism: racial contrasts in incidence and in-hospital case fatality. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98:1967–1972. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.