Abstract

Pancreatic fistula still remains a persistent problem after pancreaticoduodenectomy. We have devised a pancreas-transfixing suture method of pancreaticogastrostomy with duct-to-mucosa anastomosis. This technique is simple and reduces the risk of pancreatic leakage by decreasing the risk of suture injury of the pancreas and by embedding the transected stump into the wall of the stomach. This novel technique of pancreaticogastrostomy is an effective reconstructive procedure following pancreaticoduodenectomy, especially for patients with a soft and fragile pancreas.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00534-011-0469-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Pancreaticogastrostomy, Pancreaticoduodenectomy, Pancreatectomy, Pancreas-transfixing method, Pancreatic duct-to-gastric mucosa anastomosis

Introduction

We have used pancreaticogastrostomy without gastrotomy using a pancreatic duct-to-gastric mucosa anastomosis since 1987 as a reconstruction method following pancreaticoduodenectomy [1]. The pancreaticogastrostomy is not only safe but also good function as well as pancreaticojejunostomy [2–4]. In general, soft pancreatic tissue is one of the risk factors for pancreatic leakage. Therefore, we have devised a pancreaticogastrostomy which is a simple procedure and is safer particularly for a normal soft pancreas [5–9]. In the current study, we demonstrate the technique of pancreas-transfixing pancreaticogastrostomy in combination with duct-to-mucosa anastomosis.

Methods

Procedures of pancreaticogastrostomy

Step 1

The pancreas is transected at the level of the portal vein using an ultrasonically activated scalpel after tunneling the body of the pancreas. The advantages of using the ultrasonically activated scalpel are: (1) simultaneous cutting and hemostasis; and (2) sealing the small branches of the pancreatic duct by denatured proteins [6]. Pressure on the pancreas and closure of the pancreatic stump are not necessary to control bleeding. Next, a pancreatic tube (S.B. Medical, Tokyo, Japan) 60 cm long and 5–7.5 French in diameter is inserted into the main pancreatic duct of the remnant pancreas. At least 1 cm mobilization of the pancreas is necessary for anastomosis.

Step 2

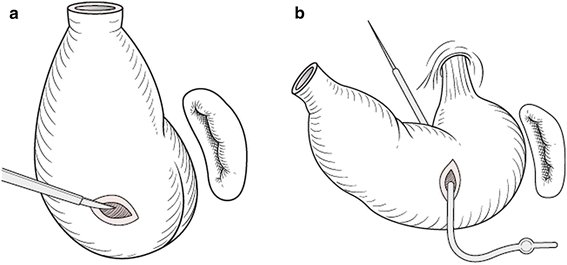

A 2-cm-long seromuscular incision is made in the posterior wall of the stomach (Fig. 1a), followed by a stab incision of 2–3 mm in the gastric mucosa. The needle of the pancreatic tube is then passed through both the anterior and posterior walls of the stomach (Fig. 1b). The advantages of using the pancreatic tube are: (1) it acts as a guide so that the pancreaticogastrostomy can be performed more easily and safely; and (2) it can be used as a lost stent or external tube after the anastomosis.

Fig. 1.

Seromuscular incision in the posterior wall of the stomach and the use of the pancreatic tube. a A 2 cm long seromuscular incision is made in the posterior wall of the stomach exposing the gastric mucosa. b The needle of the pancreatic tube is then passed both anterior and posterior walls of the stomach through the seromuscular stab incision

Step 3: outer layer of sutures (pancreas-transfixing suture)

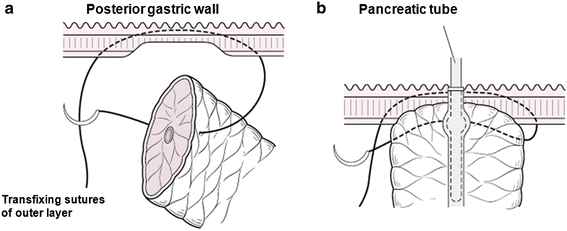

An end-to-side pancreaticogastric anastomosis is made in two layers. The outer layer of sutures consists of 2-0 silk placed by a curved 35-mm-long needle from the posterior inferior wall to the superior wall of the stomach, then passing from the anterior to the posterior surface of the pancreas (Fig. 2a). The sutures on the stomach are placed widely so that the pancreatic stump can be embedded into the wall of the stomach at the seromuscular incision (Fig. 2b). The sutures on the pancreas are placed 1 cm away from the cut edge (Fig. 2a). Six to eight sutures are generally used, although the number depends on the size of the stump of the pancreatic remnant.

Fig. 2.

Transfixing suture between the posterior gastric wall and the remnant pancreas. a The outer sutures (with 2-0 silk) are placed with a curved 35 mm long needle from the posterior inferior wall to the posterior superior wall of the stomach, and then passed through the anterior and posterior surface of the remnant pancreas. The sutures on the stomach are placed widely so that end of the pancreatic stump can be embedded within the seromuscular incision. The sutures on the pancreas are placed 1 cm away from the cut edge. b A vertical section of pancreaticogastrostomy is shown. Any space between the posterior gastric wall and the pancreatic stump is minimized

Step 4: inner layer of sutures (pancreatic duct-to-gastric mucosa anastomosis)

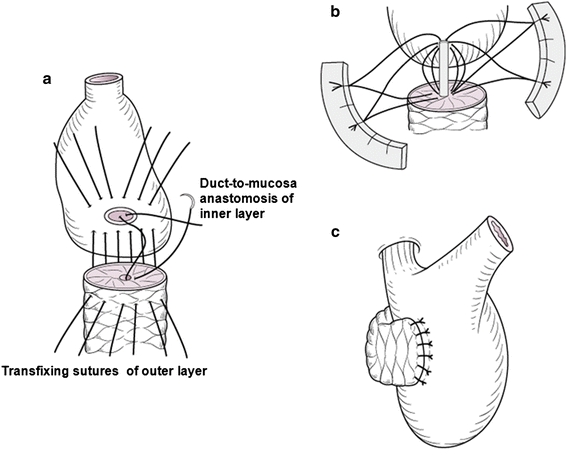

The pancreatic duct is anastomosed to the gastric mucosa with absorbable 4-0 interrupted sutures using four to eight sutures, depending on the diameter of the duct of the pancreatic remnant (Fig. 3a). We use suture holders or mosquito clamps because these make it easier to perform ligation of the duct-to-mucosa anastomosis in an orderly way (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

Procedures of pancreas-transfixing pancreaticogastrostomy. a After the transfixing sutures of the outer layer, the pancreatic duct is anastomosed to the gastric mucosa with absorbable 4-0 interrupted stitch; four to eight sutures are generally used, based on the diameter of the duct. b Suture holders facilitate the ligation of the inner layer sutures. c After the duct-to-mucosa anastomosis, the outer layer sutures are tied and the pancreaticogastrostomy is complete

Step 5: ligations of outer and inner layers of sutures

After the ligations of duct-to-mucosa anastomosis of the inner layer are completed, the pancreas-transfixing sutures of the outer layer are tied. Then, the pancreaticogastric anastomosis is complete (Fig. 3c). Each ligation should be carefully performed because the normal pancreas is soft and fragile.

Step 6: completion of pancreaticogastrostomy

A pancreatic tube of approximately 3 cm in length is cut for use as an internal stent. The anterior wall of the stomach is closed using an absorbable 4-0 interrupted suture and the pancreaticogastric anastomosis is complete. Finally, two silicon closed drains are placed in the foramen of Winslow and Morison’s pouch. In addition, we recommend that these drains should be pulled out in five postoperative days.

Results

A total of 205 consecutive patients underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy with pancreaticogastrostomy. They were 128 males and 77 females, with a mean age of 66 years. Of the 205 study patients, 137 patients (67%) had a soft pancreas, 48 (23%) had pancreatic tissue of intermediate texture and the remaining 20 (10%) had a hard or firm pancreas.

There were no operative or hospital death. Postoperative complications occurred in 38 patients (19%). The most common complication was delayed gastric emptying (Grade B/C) in 15 patients (7%). Pancreatic leak (Grade B/C) occurred in 4 patients (2%) with a soft thin pancreas. These pancreatic leaks were managed nonoperatively by maintaining the closed drains. No pancreatic leak occurred in patients with intermediate texture or hard pancreas.

Discussion

The reconstructive procedures of the remnant pancreas are classified into pancreaticojejunostomy and pancreaticogastrostomy. It is important for surgeons to have multiple options for reconstruction of the remnant pancreas. Although the differences between pancreaticojejunostomy and pancreaticogastrostomy have been discussed for many years, it is now thought that the pancreaticogastrostomy is the safer method for the prevention of pancreatic fistula [10–13].

In the history of pancreaticogastrostomy, Tripodi [14] performed a pancreaticogastrostomy in a dog for the first time in 1934 and reported the long-term secretion of pancreatic juice. Waugh performed the first pancreaticogastrostomy on a human in 1944 [15]. Since this report, Mackie reported 25 pancreaticogastrostomies in 1975 [16], and Flautner [17] reported 37 pancreaticogastrostomies for pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy in 1985. In Japan, Watanabe first reported a case of pancreaticogastrostomy in 1985 [18], Takada [19] performed pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy with pancreaticogastrostomy for the first time in 1987, Miyagawa [10] published the first English-language report of pancreaticogastrostomy in 1992 and Takao [1] reported a modified pancreaticogastrostomy with pancreatic duct-to-gastric mucosa anastomosis in 1993. To date, approximately 3,800 pancreaticogastrostomies have been reported. Importantly, the rate of pancreatic fistula occurrence is 0–14% and the operative mortality rate is 0–4.9%. In our experience, the incidence of pancreatic leaks and the operative mortality were 2 and 0%, respectively.

The merits of a pancreas-transfixing method with duct-to-mucosa anastomosis are: (1) it can be carried out safely on the normal pancreas because it is a simple technique, (2) the stomach is the organ targeted for anastomosis because it is not usually affected by unstable metabolism and/or organ edema by the extended operation, (3) there is no leakage of the gastric juice because there is no incision through all stomach layers, (4) most cases with leakage of pancreatic juice are cured spontaneously in a short time because pancreatic juice mixed with gastric juice has a lower digestive activity than pancreatic juice mixed with intestinal juice. On the other hand, a disadvantage of this method is that the stomach and pancreas are located anatomically such that securing a good field of vision is slightly difficult.

With regard to the long-term pancreatic function of patients who have undergone pancreaticoduodenectomy with pancreaticogastrostomy, we have had no serious complications so far. The cumulative patency rate of pancreato-gastric anastomosis was high and the incidence of postoperative diabetes mellitus was low in our series. These results suggest that the new pancreaticogastrostomy can provide excellent long-term pancreatic function after pancreaticoduodenectomy.

In conclusion, transfixing pancreaticogastrostomy in combination with duct-to-mucosa anastomosis using an internal stent is technically easy to perform and possesses several advantages. Therefore, this method is an effective reconstructive procedure for a soft and fragile pancreas following pancreaticoduodenectomy.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Footnotes

This article is based on studies first reported in Highly Advanced Surgery for Hapato-Biliary–Pancreatic Field (in Japanese). Tokyo: Igaku-Shoin, 2010.

References

- 1.Takao S, Shimazu H, Maenohara S, et al. Modified pancreaticogastrostomy following pancreaticoduodenectomy. Am J Surg. 1993;165:317–321. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(05)80833-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takao S, Shinchi H, Aikou T. Reconstruction of the pancreas following pancreaticoduodenectomy: pancreaticogastrostomy. Surgery. 1998;60:551–4 (in Japanese).

- 3.Shinchi H, Takao S, Aikou T. Gastric pH after pancreaticogastrostomy: comparison with PPPD, SR and PD. Jpn J Bilio Pancreat Physiol. 1999;15:11–3 (in Japanese).

- 4.Shinchi H, Takao S, Maenohara S, et al. Gastric acidity following pancreaticogastrostomy with pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J Surg. 2000;24:86–91. doi: 10.1007/s002689910016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takao S, Shinchi H, Yamamoto S, et al. A novel pancreaticogastrostomy: pancreas-transfixing suture method for normal pancreas. Operation. 2000;54:529–34 (in Japanese).

- 6.Takao S, Shinchi H, Maemura K, et al. Ultrasonically activated scalpel is an effective tool for cutting the pancreas in biliary-pancreatic surgery: experimental and clinical studies. J Hepato Biliary Pancreat Surg. 2000;7:58–62. doi: 10.1007/s005340050155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shinchi H, Takao S, Maemura K, et al. Value of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography with secretin stimulation in the evaluation of pancreatic exocrine function after pancreaticogastrostomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2004;11:50–55. doi: 10.1007/s00534-003-0868-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shinchi H, Takao S, Maemura K, et al. A new technique for pancreaticogastrostomy for the soft pancreas: the transfixing suture method. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2006;13:212–217. doi: 10.1007/s00534-005-1036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shinchi H, Maemura K, Mataki Y, Kurahara H, Natsugoe S, Takao S. Pancreaticogastrostomy for “Zero” of leakage following pancreaticoduodenectomy: technique of the transfixing suture method. Operation. 2009;63:1307–13 (in Japanese).

- 10.Miyagawa S, Makuuchi M, Lygidakis NJ, et al. A retrospective comparative study of reconstructive methods following pancreaticoduodenectomy: pancreaticojejunostomy vs pancreaticogastrostomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 1992;39:381–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takano S, Ito Y, Watanabe Y, et al. Pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy in reconstruction following pancreaticoduodenectomy. Br J Surg. 2000;87:423–427. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohigashi H, Ishikawa O, Eguchi H, et al. A simple and safe anastomosis in pancreaticogastrostomy using mattress sutures. Am J Surg. 2008;196:130–134. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murakami Y, Uemura K, Hayashidani Y, et al. Long-term pancreatic endocrine function following pancreatoduodenectomy with pancreaticogastrostomy. J Surg Oncol. 2008;97:519–522. doi: 10.1002/jso.21004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tripodi AM, Sherwin CF. Experimental transplantation of the pancreas into the stomach. Arch Surg. 1934;28:345. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1934.01170140125008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waugh JM, Clagett OT. Resection of the duodenum and head of the pancreas for carcinoma. Surgery. 1946;20:224–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mackie JA, Rhoads JE, Park CD. Pancreaticogastrostomy: a further evaluation. Ann Surg. 1975;181:541–545. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197505000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flautner L, Tihanyl T, Szecseny A. Pancreaticogastrostomy: an ideal complement to pancreatic head resection with preservation of the pylorus in the treatment of chronic pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 1985;150:608. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(85)90446-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watanabe G, Udagawa H, Suzuki M, et al. Pancreaticogastrostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Clin Surg. 1985;40:621 (in Japanese).

- 19.Takada T, Yasuda H, Uchiyama K, et al. A pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy reconstructed with pancreaticogastrostomy. J Tokyo Women’s Med Coll. 1986;56:533 (in Japanese). [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.