Abstract

Progestogens [progesterone (P4) and its products] play fundamental roles in the development and/or function of the central nervous system during pregnancy. We, and others, have investigated the role of pregnane neurosteroids for a plethora of functional effects beyond their pro-gestational processes. Emerging findings regarding the effects, mechanisms, and sources of neurosteroids have challenged traditional dogma about steroid action. How the P4 metabolite and neurosteroid, 3α-hydroxy-5α-pregnan-20-one (3α,5α-THP), influences cellular functions and behavioral processes involved in emotion/affect, motivation, and reward, is the focus of the present review. To further understand these processes, we have utilized an animal model assessing the effects, mechanisms, and sources of 3α,5α-THP. In the ventral tegmental area (VTA), 3α,5α-THP has actions to facilitate affective, and motivated, social behaviors through non-traditional targets, such as GABA, glutamate, and dopamine receptors. 3α,5α-THP levels in the midbrain VTA both facilitate, and/or are enhanced by, affective and social behavior. The pregnane xenobiotic receptor (PXR) mediates the production of, and/or metabolism to, various neurobiological factors. PXR is localized to the midbrain VTA of rats. The role of PXR to influence 3α,5α-THP production from central biosynthesis, and/or metabolism of peripheral P4, in the VTA, as well as its role to facilitate, or be increased by, affective/social behaviors is under investigation. Investigating novel behavioral functions of 3α,5α-THP extends our knowledge of the neurobiology of progestogens, relevant for affective/social behaviors, and their connections to systems that regulate affect and motivated processes, such as those important for stress regulation and neuropsychiatric disorders (anxiety, depression, schizophrenia, drug dependence). Thus, further understanding of 3α,5α-THP’s role and mechanisms to enhance affective and motivated processes is essential.

Keywords: allopregnanolone, anxiety, lordosis, paced mating, progesterone, sex differences, stress, ventral tegmental area

Introduction

Steroids play fundamental roles in the development and/or function of the central nervous system (CNS) and exert both organizational and activational effects. During pregnancy, levels of progestogens [i.e., progesterone (P4) and its metabolites] are high and have well-known effects to maintain pregnancy and may alter brain development of the gestating offspring. We, and others, have investigated the role of pregnane neurosteroids for a plethora of functional effects beyond their pro-gestational processes in adulthood. Some of these effects are those involved in emotion/affect, motivation, and reward, which will be the focus of this review.

Emerging findings regarding the effects, mechanisms, and sources of steroids have challenged traditional dogma and revealed non-traditional actions of hormones to influence cellular functions and behavioral processes. First, some of the most salient effects of steroids are to change the threshold for a biological or behavioral response to appropriate stimuli. We now know that steroid levels can change in response to environmental and/or behavioral situations and, thereby, influence the likelihood of subsequent steroid-mediated processes occurring. There is now a greater understanding of subtle, and dynamic changes in steroids to mediate homeostatic processes [e.g., hypothalamic-pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis function], which may exert proximate and discrete effects on physiological and/or behavioral processes. Second, the classic mechanisms of steroids are considered to involve their binding to cognate, intracellular steroid receptors, which are present throughout the brain in hypothalamic and limbic regions (Shughrue et al., 1997; Osterlund et al., 2000), and modulate transcription and translation (Pfaff et al., 1976), a process which takes 10 min to days. Steroids can also act in the CNS via membrane targets or rapid-signaling actions, which occur within seconds to minutes. Neuro(active) steroids produce rapid effects on neuronal excitability and synaptic function that involve direct or indirect modulation of ion-gated or other neurotransmitter receptors and transporters, rather than classic nuclear hormone receptors. Third, steroids are typically thought to be secreted from peripheral endocrine glands into circulation, whereupon they can exert effects at target sites in the body and brain that are distant from the endocrine gland source. However, the brain, like the gonads, adrenals, and placenta, can be considered an endocrine organ. That is, the brain requires coordinated actions of steroidogenic enzymes in neurons and glia to metabolize peripheral steroids to products that act in the brain (“neuroactive steroids”), or to produce steroids de novo in the brain independent of peripheral gland secretion (“neurosteroids”). In this view, steroids exert intracrine effects to mediate intracellular events, and paracrine, or neurotransmitter-like, effects to induce biological responses in adjacent cells. This review will focus its discussion on the effects, mechanisms, and sources of the P4 metabolite and neurosteroid, 5α-pregnan-3α-ol-20-one (3α,5α-THP, a.k.a. allopregnanolone), for affective, motivated, and reward processes. As discussed as follows, we examine effects, sources, and mechanisms of progestogens in rats, which have demonstrated similar effects and patterns of progestogen secretion as is seen in people (Holzbauer, 1975, 1976; Holzbauer et al., 1985; Frye and Bayon, 1999), and, thus, can provide insight into progestogens’ role in these processes.

Model System to Investigate Progestogens’ Effects, Mechanisms, and Sources for Affective and Motivated Behaviors

We have utilized an animal model to elucidate the effects, mechanisms, and sources of progestogens to influence affective and motivated behaviors of rodents. Progestogens may have a role in the etiology, expression, and/or therapeutic treatment of anxiety, stress, and/or mood (dys)regulation, as discussed below. Mating is a sexually dimorphic and progestogen-mediated behavior. To be able to determine necessary mechanisms for this behavior, we have utilized lordosis (the posture that female rodents assume to enable mating to occur, which can be considered a consummatory aspect of mating for the female) as an ethologically relevant bioassay for progestogens’ actions. In this regard, we have examined progestogens’ physiological and ethological role to mediate lordosis, as well as neuroendocrine and behavioral processes relevant for social interactions and/or affect, which can be considered appetitive aspects of mating. In this model, lordosis is both a sensitive measure of progestogens’ effects as well as an experiential factor in the rodent’s life that can be manipulated to alter subsequent neuroendocrine and behavioral responses. As such, the directionality of the effects of progestogen production and affective and motivated responding can be examined. Thus, investigating behaviors commonly disrupted in neuropsychiatric disorders (affect, social, and reproductive endocrine function), using an ethologically relevant model of rodent behavior, can elucidate the functional role of progestogens, such as 3α,5α-THP, for mental health.

In this model system, we have focused to date on actions of progestogens in the midbrain ventral tegmental area (VTA). The VTA is a target of interest for several reasons including its role in the mesolimbic dopamine system. Natural fluctuations in progestogens, and administration of progestogens to the VTA, produce robust behavioral effects, such as enhancing affect and facilitating reproductive and other motivated behaviors (Frye et al., 2006a; Frye, 2009). For example, central infusions of 3α,5α-THP to VTA (but not to nearby regions, such as central gray, raphe nucleus, substantia nigra) of non-sexually receptive rats significantly enhances affective and social behavior to levels commensurate with those observed in sexually receptive rats (Frye and Rhodes, 2006a, 2007a,b, 2008). The VTA is largely devoid of P4’s traditional cognate steroid receptor targets, progestin receptors (PRs). 3α,5α-THP has lower affinity for PRs than it does for γ-aminobutyric acid (GABAA), glutamatergic, and dopaminergic receptor targets, which are highly expressed in the VTA (Frye and Walf, 2008a). As well, blocking 3α,5α-THP targets, such as GABAA receptors, in the VTA attenuates anti-anxiety and social behavior among sexually receptive females (Frye et al., 2006b,c; Frye and Paris, 2009). This is not observed when blockers are administered to nearby missed sites, such as the substantia nigra or central gray (Frye and Paris, 2009). As such, actions of 3α,5α-THP in the VTA to enhance anti-anxiety and pro-social motivated behaviors may be specific to the VTA and its connections. Enzymes, such as 5α-reductase and 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3α-HSD), that are necessary for the metabolism of P4 to 3α,5α-THP, and de novo synthesis of 3α,5α-THP, are highly expressed in the VTA (Li et al., 1997; Frye, 2001a,b), suggesting that this is a region to investigate to further understand the sources of progestogens. Indeed, P4, from central or peripheral sources, is readily metabolized to 5α-pregnane-3,20-dione-dihydroprogesterone (DHP), by actions of 5α-reductase, and 3α,5α-THP, by actions of 3α-HSD, in the VTA. Blocking P4’s metabolism to 3α,5α-THP in the VTA, or blocking de novo production, or neurosteroidogenesis, of 3α,5α-THP in the VTA, attenuates affective and social behavior among sexually receptive rats (Frye and Petralia, 2003a,b; Frye et al., 2008b). Reinstating 3α,5α-THP concentrations via enhancement of neurosteroidogenesis, or 3α,5α-THP add-back, reinstates these behaviors (Petralia et al., 2005; Frye et al., 2009). Thus, we can use behavioral endpoints of female rodents to ascertain the sources, effects, and mechanisms of progestogens in the midbrain VTA, and determine the extent to which these actions are relevant in other brain regions and systems. What follows is a discussion of findings from our laboratory, and others, regarding the effects, mechanisms, and sources of 3α,5α-THP for affect, motivation, and reward processes.

Effects of 3α,5α-THP

Gender differences for affective and motivated processes

Depression and anxiety are serious and wide-spread disorders, with effects on emotion as well as motivation- and reward-related processes. Incidence and expression of these disorders are greater among women compared to men, and may be related to fluctuations in P4 and 3α,5α-THP. Over their lifetime, mature women experience greater variations in, and higher levels of, progestogens than do men, and they are more susceptible to depression and/or anxiety disorders (Weissman and Klerman, 1977; Kessler et al., 1994; Seeman, 1997; Wittchen and Hoyer, 2001). During the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle, circulating progestogen levels of women are low (similar to men); however, luteal phase circulating levels are two to fourfold higher (2–4 nmol/l) than follicular phase levels (∼1 nmol/l; Genazzani et al., 1998; Purdy et al., 1990; Sundström and Bäckström, 1998a,b; Wang et al., 1996). During pregnancy, circulating levels of progestogens rapidly increase to peak in the third trimester (50–160 nmol/l), and reach nadir within a day post-parturition (Sundström et al., 1999; Luisi et al., 2000; Herbison, 2001). The onset and/or expression of depression and/or anxiety can be mediated by some of these changes in progestogen levels over natural cycles. In support, premenstrual syndrome, premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD), post-partum depression, and menopause, are associated with negative affect/mood, and occur when progestogen levels are low (Glick and Bennett, 1981; Angold et al., 1999; Endicott et al., 1999; Chaudron et al., 2001; Girdler et al., 2001; Soares and Cohen, 2001; Freeman et al., 2002, 2004; Rapkin et al., 2002; Bäckström et al., 2003; Markou et al., 2005; Pearlstein et al., 2005). Moreover, substance abuse disorder is often co-morbid with depression and anxiety (Regier et al., 1990), especially among women compared to men (Brady and Randall, 1999). Natural fluctuations in progestogens across the menstrual cycle alter responses to drugs of abuse, such as alcohol, cocaine, and nicotine (Sofuoglu et al., 1999; Pomerleau et al., 2000; Nyberg et al., 2004). Understanding the effects, mechanisms, and sources of neurosteroids, such as 3α,5α-THP, may provide insight into gender/sex differences, etiology, expression, progression, and/or treatment of some mental health disorders.

In addition to gender/sex differences for affective and motivated processes as discussed above, there may are gender/sex differences in normal stress responding of males and females. Males may be more likely to cope by mounting a “fight-or-flight” type response toward stressors, whereas females may cope better with a “tend-and-befriend” response (Taylor et al., 2000). Although many neurobiological factors clearly differ between males and females, and likely contribute to these differences in pathophysiological and normative responding, the focus of this review is on how 3α,5α-THP has such actions. Thus, findings of 3α,5α-THP’s role in stress, affect, and motivated processes follow.

3α,5α-THP alters the HPA axis

3α,5α-THP has agonist-like actions at inhibitory GABA receptors and can dampen stress-induced HPA activity, which may mitigate parasympathetic tone. 3α,5α-THP’s anesthetic properties have been recognized for some time (Selye, 1941), related to its potency at enhancing GABA function (Majewska et al., 1986). Administration of 3α,5α-THP reduces adrenocorticotropin secretion in response to acute stress, and blocks adrenalectomy (ADX)-induced increases in corticotrophin releasing factor mRNA (Patchev et al., 1994, 1996). When 3α,5α-THP levels are elevated, during proestrus or pregnancy, or when ovariectomized (OVX) rats are administered 3α,5α-THP, there are robust anti-anxiety and anti-stress effects (Harrison and Simmonds, 1984; Majewska et al., 1986; Lambert et al., 2003; Belelli and Lambert, 2005; Martín-García and Pallarès, 2005; Frye et al., 2006a; Frye, 2009). Blocking formation of 3α,5α-THP, or its actions at GABAA receptors, prevents anti-anxiety and anti-depressant behavior, as well as glucocorticoid secretion following stressor exposure (Rhodes and Frye, 2001; Reddy, 2002; Verleye et al., 2005; Walf et al., 2006; Frye, 2009). Thus, 3α,5α-THP may have homeostatic effects by restoring parasympathetic tone following stressor exposure.

Stress alters 3α,5α-THP

Stressor exposure has salient effects to alter 3α,5α-THP throughout the lifespan. Brain levels of 3α,5α-THP are measurable as early as embryonic day 14 in rats (Kellogg and Frye, 1999). By postnatal day 6, 3α,5α-THP increases in the brain of rats in response to maternal separation stress (Kehoe et al., 2000; McCormick et al., 2002). In adult rodents, 3α,5α-THP increases in response to a variety of acute stressors (cold-water swim, restraint, foot-shock, loud noise, carbon dioxide inhalation, ether exposure, or administration of anxiogenic drugs) occur in intact, gonadectomized (GDX), and/or ADX rodents (Erskine and Kornberg, 1992; Paul and Purdy, 1992; Barbaccia et al., 1996, 1997; Frye, 2001a,b; Serra et al., 2002). Stimuli that can be considered more subtle than these aforementioned acute stressors, such as social challenge and/or mating, alters production of 3α,5α-THP (as described in further detail below; Frye, 2001a,b; Miczek et al., 2003; Frye and Rhodes, 2006a). Increases in 3α,5α-THP produced by such experiences are conserved across species, enhance GABA function, increase anxiolysis, and reduce HPA responses (Paul and Purdy, 1992; Patchev and Almeida, 1996; Barbaccia et al., 2001; Frye, 2001a,b, 2009; Reddy, 2003). Thus, 3α,5α-THP is expressed early in development and can be altered by stress at this time and during adulthood.

Sex/progestogen effects on stress

There are sex differences in the 3α,5α-THP response to stressors. Maternal separation stress produces greater increases in brain 3α,5α-THP levels of male, compared to female, pups between postnatal day 7 and 10 (Kehoe et al., 2000; McCormick et al., 2002). In male rats, non-stress, basal 3α,5α-THP levels are higher at an early juvenile age (postnatal day 14), whereas in females, basal 3α,5α-THP levels are higher at postpubertal ages (42 and 60 days). Although it is currently unclear what role higher 3α,5α-THP levels in males at early juvenile ages, or in females at late adolescent/early adult ages, may have in adults, evidence indicates that progestogens modify stress responses. Post-partum women, who have increased estradiol (E2), but decreased progestogens, have greater HPA response to stressors (Altemus et al., 2001). Stress responses of women may be increased when progestogens are decreased postmenopause (De Leo et al., 1998). In premenopausal women, oral contraceptives, or progestogens, decrease cortisol levels (Hellman et al., 1976; Jacobs et al., 1989). Thus, there are gender/sex differences in stress responding, and stress responses can be modulated by progestogens.

3α,5α-THP and depression

Neurosteroids, such as 3α,5α-THP, may play a role in depression. Stressful life events can precipitate depression (Brown et al., 1994). Individuals with depression often have difficulties in coping with stress. Increased levels of corticotrophin releasing factor and cortisol, and/or impaired glucocorticoid feedback to dexamethasone, are observed in depression (Carroll et al., 1976, 1981; Halbreich et al., 1985; Rubin et al., 1987; Nemeroff et al., 1988; Young et al., 2000). Depression is a common side-effect of treatment of alopecia or benign prostate hyperplasia with finasteride, a 5α-reductase inhibitor, which decreases neurosteroids, such as 3α,5α-THP and its androgen equivalent, androstanediol (Altomare and Capella, 2002; Clifford and Farmer, 2002; Townsend and Marlowe, 2004). Thus, 3α,5α-THP inhibition can precipitate depression among some individuals.

Findings from animal models also support a role of progestogens in depressive behaviors. For example, when rodents are in the proestrous phase of the estrous cycle and have high levels of progestogens, they show less depressive behavior compared to rodents that are in low progestogen phases of the estrous cycle (Becker and Cha, 1989; Bitran et al., 1991; Frye et al., 2000b; Frye and Walf, 2002; Gulinello et al., 2003). Pregnant rats, which have sustained, higher levels of progestogens, show less depressive behavior in the forced swim test than do post-parturient rats, with lower levels of progestogens (Frye and Walf, 2004; Walf and Frye, 2006). Ovariectomy, removal of the primary source of endogenous progestogens, increases depressive behavior among female rats in the forced swim test (Frye and Wawrzycki, 2003; Walf et al., 2006). Administration of P4 and/or 3α,5α-THP can reverse these effects (Frye and Walf, 2002; Hirani et al., 2002; Frye et al., 2004a). The anti-depressant effects of P4 are reduced when drugs that block conversion of P4 to 3α,5α-THP, such as finasteride, are co-administered (Frye and Walf, 2002; Hirani et al., 2002; Walf et al., 2006). Similarly, the anti-depressive effects of P4 in the forced swim test are attenuated among 5α-reductase knockout mice that cannot readily convert P4 to 3α,5α-THP (Frye et al., 2004a). In another animal model of depression, social isolation of mice, lower levels of 3α,5α-THP have been reported (Dong et al., 2001; Guidotti et al., 2001). Thus, some of progestogens’ anti-depressive effects in rodents may be due to actions of 3α,5α-THP.

3α,5α-THP and anxiety

3α,5α-THP’s role in various anxiety disorders have been investigated. Baseline plasma levels of 3α,5α-THP are normal in patients with generalized anxiety disorders and social phobia (Le Mellédo and Baker, 2002). However, 3α,5α-THP levels are higher than normal among people with panic disorder (Brambilla et al., 2003; Ströhle et al., 2003), and are reduced by infusions of sodium lactate or cholecystokinin tetrapeptide, which can induce panic attacks (Ströhle et al., 2003). In people without a history of panic attacks, levels of neurosteroids are either not affected, or greater, following administration of panic-inducing agents (Tait et al., 2002; Zwanzger et al., 2004; Eser et al., 2005). In women with panic disorder, perimenstrual, but not midluteal, 3α,5α-THP levels were significantly higher than controls, and correlated with their panic–phobic symptoms (Brambilla et al., 2003). With Dr. John Casada, we found that among men with post-traumatic stress disorder, those with higher 3α,5α-THP levels have lower state anxiety following exposure to trauma-related stimuli (Frye, 2009). Thus, there is some evidence for differences in 3α,5α-THP among those with anxiety disorders.

Animal models also support a role of progestogens in anxiety behavior (Guidotti and Costa, 1998; Bitran et al., 2000; Jain et al., 2005). When P4 and 3α,5α-THP levels are high, such as during proestrus and pregnancy, anxiety behavior is lower among female rodents compared to when levels are declining or are low (Becker and Cha, 1989; Bitran et al., 1991; Frye et al., 2000b; Gulinello et al., 2003; Walf and Frye, 2006). Ovariectomy increases anxiety behavior of female rodents (Frye and Walf, 2002; Walf et al., 2006) and P4 or 3α,5α-THP reverses this (Frye and Walf, 2004; Frye et al., 2004a; Walf et al., 2006), unless 3α,5α-THP formation is compromised or 3α,5α-THP withdrawal occurs (Rhodes and Frye, 2001; Frye and Walf, 2002, 2004). Thus, some of progestogens’ effects for anxiety-related behaviors may be due to 3α,5α-THP.

3α,5α-THP and mood dysregulation

An example of a disorder in which mood changes may be altered by 3α,5α-THP is PMDD. PMDD is characterized by both debilitating physical symptoms and negative mood state, which occurs when E2 and progestogen levels fluctuate during the luteal phase (Bäckström et al., 1983; Sanders et al., 1983; Hammarbäck et al., 1989, 1991; Ramcharan et al., 1992; Endicott et al., 1999; Sveindóttir and Bäckström, 2000). Some women with PMDD report greater positive, and negative, mood with ovarian suppression and administration of E2 and/or P4, respectively (Schmidt et al., 1998). Among women with PMDD, there are also conflicting reports that mood is more negative (Hammarbäck et al., 1989; Seippel and Bäckström, 1998), or improved (Wang et al., 1996; Girdler et al., 2001), when hormone levels are greater during the luteal phase. There is greater consensus that there are few differences among absolute levels of E2, P4, and/or 3α,5α-THP of women with PMDD and those that do not have PMDD (Rubinow et al., 1988; Halbreich et al., 1993; Schmidt et al., 1994; Wang et al., 1996, 2001; Sundström and Bäckström, 1998a; Epperson et al., 2002). However, lower (Rapkin et al., 1997; Bicikova et al., 1998; Monteleone et al., 2000), and higher (Girdler et al., 2001), concentrations of 3α,5α-THP have been reported among women with PMDD. There is evidence for differences in 3α,5α-THP among women with PMDD treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI). In support, there is clinical improvement among those with stabilized 3α,5α-THP levels following SSRI treatment (Freeman et al., 2002; Gracia et al., 2009). One explanation for some of the heterogeneity in these findings is that there may be bimodal responses associated with differences in sensitivity of GABA receptors (Sundström et al., 1997a,b, 1998). Together, these data suggest that 3α,5α-THP may underlie some effects on mood processes among women.

3α,5α-THP and schizophrenia

3α,5α-THP may play a role in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia, which is characterized by deficits in social, affective, and cognitive functioning (Shirayama et al., 2002). Additionally, schizophrenia is characterized by dysregulation of the HPA axis (Lukoff et al., 1984; Malla et al., 1990; Norman and Malla, 1993; Myin-Germeys et al., 2001; Read et al., 2001) and psychosis can be precipitated by stress (Read et al., 2001). Those with schizophrenia may have altered stress-induced 3α,5α-THP production, which is supported by a novel polymorphism in the gene sequence encoding for enzymes involved in 3α,5α-THP biosynthesis and may create a predisposition to over-sensitivity to stress (Kurumaji et al., 2000; Myin-Germeys et al., 2001; Read et al., 2001). Moreover, women have higher levels of 3α,5α-THP and are more likely to have later onset schizophrenia, better prognosis, and therapeutic response to lower dosages of anti-psychotics than do men (Usall et al., 2007; Abel et al., 2010). When 3α,5α-THP levels are low perimenstrually, greater psychotic episodes and more negative schizophrenia symptoms are reported (Hallonquist et al., 1993; Hendrick et al., 1996; Huber et al., 2001). Thus, schizophrenia may involve a reduced capacity to synthesize 3α,5α-THP in the brain, which may increase sensitivity to stress and, thereby, vulnerability to psychosis in this population.

3α,5α-THP and actions of therapeutics

3α,5α-THP may underlie some of the effects of therapeutics for stress-related, neuropsychiatric disorders. Anxiolytic effects of etifoxine, correspond with increased levels of 3α,5α-THP in sham-operated and GDX/ADX rats (Verleye et al., 2005). An atypical anti-psychotic drug, olanzapine, enhances social functioning and increases 3α,5α-THP levels (Marx et al., 2000, 2003; Frye and Seliga, 2003a,b). Fluoxetine increases the affinity of 3α-HSD for DHP, which elevates 3α,5α-THP (Griffin and Mellon, 1999). Some patients with depression have reduced plasma concentrations and/or cerebrospinal fluid levels of 3α,5α-THP (Romeo et al., 1998; Uzunova et al., 1998). Anti-depressants, such as fluoxetine or fluvoxamine, normalize decreased 3α,5α-THP levels concomitant with reducing depressive symptomology (Uzunova et al., 2004, 2006; Dubrovsky, 2006). Other treatments of depression, such as sleep deprivation (Schüle et al., 2003), electroconvulsive therapy (Baghai et al., 2005), and transcranial magnetic stimulation (Padberg et al., 2002), modestly alter neurosteroids. Common features of these therapeutic treatments include changes in steroid biosynthesis and HPA function that may mitigate core symptoms of these neuropsychiatric disorders described above (Dubrovsky, 2006). Thus, 3α,5α-THP may underlie some actions of therapeutics.

3α,5α-THP and drug abuse

Recent investigations assessing the mechanisms of reward associated with drugs of abuse have revealed a role for progestogens. There is evidence for menstrual cycle effects for measures related to drug abuse, such as subjective feelings and craving and withdrawal following abstinence. In support, women in the luteal phase report lower rating for feeling high following smoking of cocaine than did women in the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle (Sofuoglu et al., 1999). Among cocaine-dependent women, circulating levels of progesterone were associated with cocaine craving, such that those with high progesterone had lower stress- and cocaine cue-induced cravings for cocaine and reported less anxiety (Sinha et al., 2007). Among women, there are menstrual cycle-related differences in craving and withdrawal symptoms with nicotine abstinence, which may be particularly strong among women with severe menstrual symptomatology and/or co-morbid neuropsychiatric disorders (Pomerleau et al., 2000; Carpenter et al., 2006). There are also effects of progestogen administration. For example, oral P4 to women reduces self-reported pleasurable effects of cocaine (Sofuoglu et al., 2002, 2004). Animal models show support for a role of progestogens in drug reward. There are sex and estrous cycle differences in behavioral effects and metabolism of P4 to 3α,5α-THP following cocaine administration to rats (Frye, 2007; Quiñones-Jenab et al., 2008; Kohtz et al., 2010). Moreover, systemic P4 administration to female rats blocks the rewarding effects of cocaine (Russo et al., 2008) and administration of 3α,5α-THP reduces cocaine self-administration (Anker et al., 2010). As well, administration of 3α,5α-THP, and to a lesser extent P4, reduced cocaine reinstatement following abstinence among female, but not male rats (Anker et al., 2009). Effects of P4 were attenuated with co-administration of the 5α-reductase inhibitor, finasteride, which blocks P4’s metabolism to 3α,5α-THP (Anker et al., 2009). Together, these data suggest a role of progestogens for drug reward.

Mechanisms of 3α,5α-THP for Affect and Motivated Behaviors

Neurosteroids, such as 3α,5α-THP, can have more immediate, rapid-signaling effects through ion channel-associated membrane receptors within milliseconds to seconds than steroids secreted by peripheral glands that act through classic nuclear steroid receptors. The most extensively investigated actions of neurosteroids are those at synaptic and extrasynaptic GABAA receptors, as described below. 3α,5α-THP can also have actions through other non-steroidal, ligand-gated, ion channels, and/or G-protein-coupled receptors. Those that we have focused our investigations on to date for affect, motivation, and reward are glutamate, dopamine, and membrane PRs (Rupprecht and Holsboer, 1999; Zhu et al., 2003; Frye and Walf, 2008a; Frye, 2011). A brief description of some of progestogens’ actions at these non-traditional targets is described as follows. For further discussion, the reader is referred to other recent reviews (e.g., see others in this special issue; Frye, 2009, 2011).

P4 has non-PR actions in the VTA

Among rodents, E2 and P4 initiate the facilitation of lordosis, in part, through actions to increase PR expression in the ventromedial nucleus (Schwartz-Giblin and Pfaff, 1986). In the VTA, P4 mediates the duration and intensity of lordosis. Receptor binding and immunocytochemistry experiments conducted in our lab, and others, demonstrated that there are very few intracellular PRs in the VTA of adult rodents (Warembourg, 1978; MacLusky and McEwen, 1980; Blaustein et al., 1994; Frye and Vongher, 1999). Further, the few PRs that exist in the VTA are not inducible by E2, and reducing PR expression via infusion of antisense ODNs to the VTA does not affect lordosis, as is the case with infusions to the ventromedial nucleus (Frye and Vongher, 1999; Frye et al., 2000a; Frye, 2001a). Intravenous or intra-VTA infusions of P4 to hamsters or rats enhance firing of VTA neurons within 60 s (Rose, 1990; Frye et al., 2000b) and facilitates lordosis (Pleim et al., 1991; DeBold and Frye, 1994). This effect occurs even when P4’s actions are relegated to cell membranes because it has been bound to a macromolecule like bovine serum albumin and is too large to enter the cell (Frye et al., 1992; Frye and Gardiner, 1996). These data suggest that progestogens’ actions in the VTA for lordosis do not require traditional actions at PRs. Of interest is that E2-stimulated neurosteroidogenesis of progesterone, via membrane E2 signaling, was required in OVX/ADX for proceptive, rather than receptive, behavior (Micevych et al., 2008; Micevych and Dewing, 2011). Together, these studies suggest that there are non-genomic, or non-traditional, targets of neurosteroids, like 3α,5α-THP for some of its functional effects. Some of these targets are described as follows.

3α,5α-THP acts at GABAA receptors

In nanomolar concentrations, 3α,5α-THP directly activates GABAA and is a positive, allosteric modulator. 3α,5α-THP increases chloride channel currents and lowers neuronal excitability with 20- and 200-fold higher efficacy than benzodiazepines or barbiturates, respectively (Morrow et al., 1987; Gee et al., 1995; Brot et al., 1997; Lambert et al., 2003; Reddy, 2004; Weir et al., 2004; Belelli and Lambert, 2005). In the VTA, 3α,5α-THP facilitates lordosis in part through its agonist-like actions at GABAA receptors. Pharmacological blockade of GABAA receptors attenuates lordosis of proestrous hamsters (or rats) over vehicle when administered to the VTA, but not other regions outside the VTA, such as the ventromedial hypothalamus, central gray, or substantia nigra (Frye et al., 1993; Frye and Vongher, 1999; Frye, 2001a,b; Frye and Paris, 2009, 2011a). Conversely, muscimol, which has agonist-like actions at GABAA receptors, enhances P4-facilitated lordosis of hamsters or rats, when infused to the VTA (Frye and DeBold, 1992; Frye and Gardiner, 1996). Thus, 3α,5α-THP has actions in the midbrain VTA in part through its agonist-like actions at GABAA receptors.

3α,5α-THP acts at N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors

Many of the GABAergic neurons that exist in this region also express N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors (NMDARs; Steffensen et al., 1998). Autoradiography studies indicate OVX rats administered P4 and/or E2 have reduced NMDAR binding in cortex (Wu et al., 1991; Cyr et al., 2000). Neurosteroids, such as 3α,5α-THP, have actions involving NMDARs (Korinek et al., 2011). Antagonizing NMDARs via intra-VTA infusions of MK-801, a non-competitive NMDAR antagonist, enhances P4-facilitated lordosis (Frye, 2001a,b; Petralia et al., 2007; Frye et al., 2008a; Frye and Paris, 2011b). Thus, 3α,5α-THP in the midbrain VTA may act in part through its antagonist-like actions at NMDARs.

3α,5α-THP’s actions through dopamine signaling

The VTA is also a site of dopaminergic activity, and actions of 3α,5α-THP for socially relevant behavior. In support, dopamine agonists can facilitate lordosis of rodents via phosphorylation of PRs (Mani, 2003). We have investigated the role of D1 receptors in the VTA for progestogen-facilitated lordosis. D1 receptors are localized to the VTA (Boyson et al., 1986). As well, in the VTA, where there are few PRs, infusions of D1 agonists and antagonists enhance and inhibit lordosis of E2- and progestogen-primed rodents, respectively (Frye et al., 2004b, 2006b,c,d; Petralia and Frye, 2004, 2006a,b; Sumida et al., 2005). Thus, it may be that D1 activation downstream of GABAA receptors in the VTA (Laviolette and van der Kooy, 2001; Laviolette et al., 2004; Frye et al., 2006a) underlies some of the rewarding effects of social responding among rodents.

Rapid actions of 3α,5α-THP via GABA, NMDA, and D1 receptors require activation of signal transduction cascades

Progestogens’ actions in the VTA involve activation of signal transduction pathways. In brief, infusions of adenylyl cyclase, G-proteins, protein kinase A (PKA), phospholipase C (PLC), or protein kinase C (PKC) inhibitors to the VTA attenuates the enhancing effects of GABAA or D1 agonists for 3α,5α-THP-facilitated lordosis (Fáncsik et al., 2000; Frye et al., 2004b, 2006b,d; Petralia and Frye, 2004, 2006a,b; Sumida et al., 2005; Frye and Walf, 2007, 2008a,b,c). Moreover, increased progestogen levels of rodents are associated with increases in levels of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) in the cortex (Frye, 2001a,b; Frye and Walf, 2008a). Thus, progestogens’ actions in the VTA require activation of these signal transduction molecules.

Sources of 3α,5α-THP

Beyond an understanding of the various effects of 3α,5α-THP and the mechanisms for such effects, a critical question is the sources of 3α,5α-THP for these effects. Progestogen concentrations in brain may be due to gonadal, adrenal, and central sources. One of the rate-limiting factors in understanding more about the functional significance of steroids lies in the challenge of parsing out the relative contributions of central versus peripheral endocrine glands. Neurosteroids are synthesized in the CNS and/or peripheral nervous system (PNS), rather than the gonads, adrenals, and/or placenta (Baulieu, 1980, 1991). Levels of neurosteroids are typically greater in the CNS and PNS than in circulation. Enzymes involved in peripheral gland steroidogenesis have been identified in the CNS and PNS (Li et al., 1997; Furukawa et al., 1998; Compagnone and Mellon, 2000). As well, high CNS and PNS levels of neurosteroids persist after extirpation of peripheral glands (i.e., GDX and/or ADX; Baulieu, 1980, 1991; Majewska, 1992; Paul and Purdy, 1992; Mellon, 1994). Of continued interest are the factors that are involved in neurosteroid formation.

The translocator protein (18 kDa TSPO; formally known as the peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor/recognition site) binds cholesterol in nanomolar affinities and is essential for neurosteroidogenesis. In 1977, the TSPO was first identified as the binding site for diazepam in peripheral tissues. The most extensively investigated functions of TSPOs are their role in biosynthesis of steroids. The TSPO is a high affinity cholesterol binding protein that imports cholesterol into the mitochondria (Papadopoulos et al., 2006). The steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR) protein is also involved in the importing of cholesterol, but it is unclear if TSPO and StAR work together (King et al., 2004). After its importation into the mitochondria, cholesterol is then oxidized to pregnenolone by the cytochrome P450-dependent side chain cleavage enzyme (P450scc; Mellon and Deschepper, 1993). Pregnenolone, the precursor of all neurosteroids, is metabolized to P4 by the 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3β-HSD), which can then be metabolized to form DHP and 3α,5α-THP (Mellon and Deschepper, 1993). The CNS expresses all of these enzymes that initiates steroidogenesis and can be considered rate-limiting steps in 3α,5α-THP biosynthesis (Braestrup and Squires, 1977; Benavides et al., 1983; Li et al., 1997; Furukawa et al., 1998; Gavish et al., 1999; Compagnone and Mellon, 2000; Chen and Guilarte, 2008). Some of the regions with the highest expression of StAR, 3β-HSD, 5α-reductase, and 3α-HSD, all enzymes required for 3α,5α-THP formation, are midbrain, cortical, and limbic regions and the cerebellum (Li et al., 1997; Furukawa et al., 1998; Compagnone and Mellon, 2000), which are involved in the affective and motivated processes of focus in this review. Indeed, the reader is referred to other interesting and recent reviews on the role of neurosteroidogenesis for functional processes (this volume; Rupprecht et al., 2010; Luchetti et al., 2011; Papadopoulos, 2011; Schüle et al., 2011).

P4’s effects in the VTA require formation of 3α,5α-THP

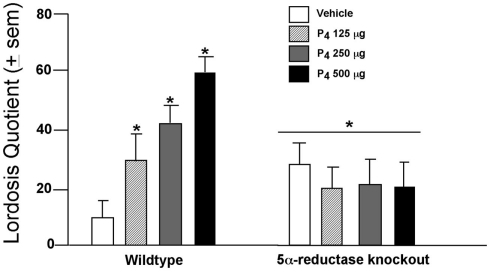

In the VTA, P4 facilitates lordosis subsequent to formation of 3α,5α-THP. Mating in rodents coincides with ovulation, when circulating and midbrain levels of P4 and 3α,5α-THP are elevated. The frequency of lordosis is greater among rats that have higher 3α,5α-THP in the midbrain, such as those in proestrus or OVX rats administered subcutaneous injections of E2 with P4 or 3α,5α-THP, compared to those in diestrus, older 12- to 14-month-old rats, or OVX rats administered vehicle or E2 + P4 and an inhibitor of 3α,5α-THP formation (Frye and Leadbetter, 1994; Frye and Gardiner, 1996; Frye and Vongher, 1999; Frye, 2001a,b; Frye and Walf, 2004; Frye et al., 2004b; Petralia et al., 2005; Walf et al., 2011). Moreover, findings from a mutant mouse model support these data. Female wild-type, or 5α-reductase knockout mice, which have perturbed function of the type II isoform of the 5α-reductase enzyme, were OVX, E2-primed, and administered P4 (125, 250, or 500 μg, SC) or vehicle oil and assessed for social responding. P4 dose-dependently enhanced lordosis among wild-type, but not 5α-reductase knockout, mice (Figure 1). A similar effect was observed for anxiety behavior among proestrous mice or those that were hormone-primed (Koonce et al., 2012). These data support the notion that P4’s metabolism to 3α,5α-THP is critical for normative affective and motivated behaviors among female rodents.

Figure 1.

Lordosis is enhanced dose-dependently when progesterone (P4) is administered (SC) to wild-type mice but not those deficient in 5α-reductase (KO). * Indicates p < 0.05 differences from wild-type mice administered vehicle.

3α,5α-THP, independent of E2, is necessary and sufficient in the VTA to mediate affective and motivated behaviors

To address whether actions of 3α,5α-THP in the midbrain VTA can influence exploratory, affective, and social behavior of rats, proestrous, or diestrous rats were infused with a physiological regimen of 3α,5α-THP (100 ng/μl) or β-cyclodextrin vehicle to the VTA (or nearby missed sites, the substantia nigra, and central gray) and were assessed in a test battery. Additionally, the role of E2, given that E2 typically co-varies with progestogens and can enhance 3α,5α-THP biosynthesis (Cheng and Karavolas, 1973), was assessed among OVX rats that were E2-primed or not before infusions and assessment in the test battery. The test battery consisted of rats being assessed in the open field and elevated plus maze for anxiety-like behavior, the social interaction and social choice tasks for social behavior, and paced mating for reproductive behavior. Infusions of 3α,5α-THP to the VTA of diestrous rats enhanced exploratory, anti-anxiety, social, and lordosis akin to that of proestrous rats infused with vehicle (Frye and Rhodes, 2008). 3α,5α-THP infusions to the VTA of OVX rats enhanced exploratory, anti-anxiety, and social behavior, independent of E2, whereas lordosis required E2-priming for its full expression (Frye et al., 2006a, 2008b; Frye and Rhodes, 2007a). Interestingly, infusions of 3α,5α-THP to the VTA resulted in higher levels of 3α,5α-THP in the midbrain VTA, as well as the hippocampus, cortex, and striatum. Infusions of 3α,5α-THP to nearby sites (substantia nigra, central gray) neither significantly altered behaviors, nor 3α,5α-THP levels, in these other regions. Thus, manipulating 3α,5α-THP in the midbrain VTA enhances exploratory, anxiety, and social responding, and elicits progestogen biosynthesis in other areas which may modulate some of these functional changes, independent of E2.

Dynamic consequences of affective and social responding on endogenous 3α,5α-THP

Beyond being necessary to alter affective and motivated responses, 3α,5α-THP levels in the midbrain are particularly dynamic and increase with challenges, such as social responding. In support, following mating, midbrain 3α,5α-THP levels are increased over those of non-mated, naturally receptive, or E2 + P4-primed rodents (Frye, 2001a,b). The rapidity of this increase in midbrain 3α,5α-THP, and independence of secretion from the ovaries and/or adrenals, suggests that biosynthesis and, subsequent, metabolism, of central, rather than peripheral, progestogens underlie these increases that we have observed among rats, mice, and hamsters (Frye, 2001a,b). Increases in midbrain 3α,5α-THP with E2, P4, and/or social responding suggest that 3α,5α-THP in varying concentrations, or when derived from peripheral versus central prohormones, may influence sexually dimorphic processes, such as affective behavior, as well as social and sexual behavior.

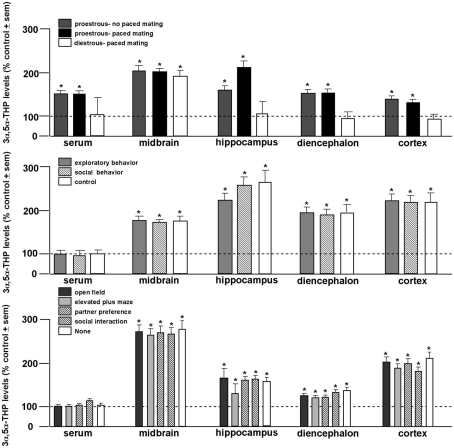

Establishment of whether paced mating underlies enhancement of 3α,5α-THP in the brain

In order to elucidate the role of behavioral processes on central levels of 3α,5α-THP, proestrous, or diestrous rats were allowed to behave in the entire battery of tasks with or without engaging in paced mating. This experiment revealed the dynamic role 3α,5α-THP plays in the midbrain. While proestrous rats had greater 3α,5α-THP levels in serum and all brain regions studied than diestrous rats, irrespective of mating condition, only diestrous rats that engaged in paced mating had enhanced 3α,5α-THP levels in midbrain compared to non-mated diestrous rats (Figure 2, top; Frye and Rhodes, 2006b). In follow-up experiments, proestrous rats were allowed to engage in portions of the battery (exploratory/anxiety tasks only or social tasks only or no tasks), or engaged in only one task in the battery, with or without paced mating. Irrespective of portion (Figure 2, middle), or individual task engaged in (Figure 2, bottom), only paced mating was associated with 3α,5α-THP enhancement in every brain region (but not serum) examined (Frye et al., 2007). As such, these experiments revealed that engaging in paced mating uniquely produces progestogen biosynthesis in midbrain and hippocampus, and to a lesser extent the striatum and cortex (Frye and Rhodes, 2007b). This complements findings that exposure to early life stressors can alter neurosteroid formation in hippocampus and stress responses mediated by the hippocampus (Frye et al., 2006e). Thus, engaging in motivated, social responding can dynamically alter progestogen synthesis in brain.

Figure 2.

3α,5α-THP levels are greater among proestrous rats in serum, midbrain, hippocampus, diencephalon, and cortex than diestrous rats irrespective of mating condition (top). 3α,5α-THP levels are enhanced in all brain regions examined among proestrous rats that engage in paced mating irrespective of exposure to exploratory (open field and elevated plus maze) or social (partner preference and social interaction) tasks compared to non-mated proestrous rats (middle). Among all tasks, only paced mating enhances 3α,5α-THP levels of proestrous rats compared to non-mated proestrous rats. Line indicates performance of non-mated diestrous (top) or proestrous (middle, bottom) control. * Indicates p < 0.05.

3α,5α-THP formation and reward processes

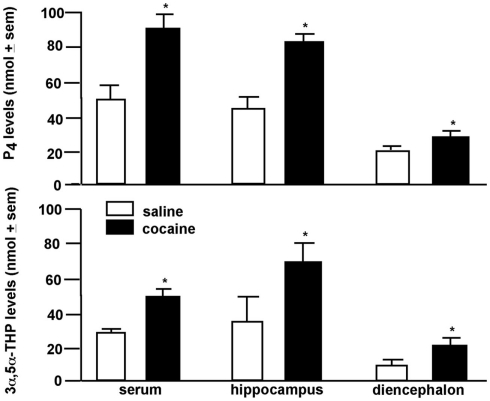

Central biosynthesis of 3α,5α-THP in response to environmental stimuli may be a function of HPA regulation. 3α,5α-THP can act as an endogenous modulator of the stress axis. 3α,5α-THP increases in response to extreme stressors, such as foot-shock, ether exposure, or cold-water swim (Purdy et al., 1991; Barbaccia et al., 1996). 3α,5α-THP has central actions to dampen HPA para/sympathetic physiological responses, in addition to its anxiolytic psychological effects (Patchev et al., 1994, 1996). Our data suggest that central 3α,5α-THP can be enhanced in response to a much more moderate stressor, such as paced mating. Paced mating in particular is rewarding and can be utilized to condition a place preference among female rats (Frye et al., 1998; Martínez and Paredes, 2001). 3α,5α-THP has likewise been found to have hedonic effects. For instance, rats will preferentially self-administer 3α,5α-THP over water (Sinnott et al., 2002). To further explore 3α,5α-THP’s effects associated with rewarding processes, we assessed effects of cocaine on progestogen concentrations in brain. We found that a single injection (5 mg/kg intraperitoneal-IP) of cocaine to female rats increased P4 and 3α,5α-THP concentrations in hippocampus, striatum, and circulation (Figure 3; Frye, 2007; Quiñones-Jenab et al., 2008). These data support the notion that HPA-activating stimuli may have rewarding effects associated with 3α,5α-THP enhancement in brain.

Figure 3.

Progesterone (P4; top) and 3α,5α-THP (bottom) levels are increased in serum, hippocampus, or diencephalon of female rats administered cocaine (5 mg/kg, IP) compared to saline. * Indicates p < 0.05.

3α,5α-THP biosynthesis in VTA is essential for enhanced affective and motivated behavior

Whether enhanced 3α,5α-THP in the VTA was due to central biosynthesis, or dependent on ovarian sources, was of interest. Proestrous rats were infused with inhibitors of 3α,5α-THP formation to the VTA. Rats received VTA infusions of PK11195 (400 ng/μl), which inhibits 3α,5α-THP formation from cholesterol, or were infused with indomethacin (10 μg/μl), which blocks DHP metabolism to 3α,5α-THP, or received both inhibitors, or were infused with β-cyclodextrin vehicle and behaviorally assessed in the affective and social responding battery. Infusions of any combination of inhibitor significantly attenuated midbrain 3α,5α-THP levels of proestrous rats concomitant with reductions in exploratory, anti-anxiety, social, and reproductive behavior (Frye et al., 2008a). In order to assess whether central 3α,5α-THP is necessary and sufficient for these effects, proestrous rats were infused with all combinations of inhibitors described, or vehicle, and were subsequently infused with a physiological dosage of 3α,5α-THP (100 ng/μl) to the VTA. Proestrous rats that were infused with 3α,5α-THP subsequent to inhibitor infusions had a reinstatement of exploratory, anti-anxiety, and social behavior that was commensurate to that of vehicle-infused controls (Frye and Paris, 2009). In a follow-up study, effects of infusion of a neurosteroid enhancer (FGIN 1,27; 5 μg/μl) following TSPO (PK11195, 400 ng/μl) or 3α-HSD (indomethacin, 10 μg/μl) inhibitor infusion was assessed and revealed that enhancement of central biosynthesis via TSPO could overcome effects of 3α,5α-THP inhibitors on these behaviors, as well as midbrain 3α,5α-THP levels (Frye et al., 2009). In this study, it may be that FGIN 1,27 outcompeted PK11195 at the TSPO in the VTA to overcome its inhibition and increase 3α,5α-THP levels. A question is whether FGIN 1,27 may have had greater effects on DHP, compared to 3α,5α-THP, following indomethacin administration levels given cross-reactivity of these steroids in the radioimmunoassay utilized. Despite these considerations that need to be addressed, these data suggest that central biosynthesis of 3α,5α-THP in VTA is necessary and sufficient to enhance expression of affective/motivated responding in proestrous rats.

Changes in gene expression with mating

Pharmacological studies discussed above are corroborated by experiments examining differences in gene expression in the midbrain of naturally receptive rats that underwent paced mating or did not have this social experience. Among mated rats, genes that were upregulated in the midbrain were primarily related to those substrates that our past pharmacological studies have elucidated as targets for progestogens’ to influence lordosis. First, of the approximately 40 genes that were upregulated in mated rats, many are relevant to downstream intracellular signaling pathways involved in non-genomic action (Paris et al., 2011). For example, there was upregulation of three genes (Calb3- increased 32.0-fold, Ascl1- increased 7.3-fold, DRd2- increased 2.0-fold) involved in regulating dopamine activity in midbrain. Ascl1 encodes for a protein that mediates neurogenesis and differentiation of tyrosine hydroxylase-containing neurons during development. Calb3 encodes for calbindin 3 and, calbindin can modulate depolarization of dopamine cells. Drd2 encodes the dopamine type 2 receptor, which is a known autoreceptor that may modulate activity of dopamine cell bodies in the VTA. There was increased expression of genes that have implications for G-protein activity (i.e., guanosine-5′-diphosphate (GDP) and guanosine-5′-triphosphate (GTP)- associated proteins), which substantiates that G-protein activity in the VTA is involved in progestogens’ actions. Expression of two forms of ram, which encode for GTP binding proteins, were increased 2.3- and 2.0-fold and expression of RAB3d, which encodes the GDP/GTP exchange protein, was 2.5 times greater in mated versus non-mated rats. Second, mating induces 3α,5α-THP biosynthesis and many genes that were upregulated were those involved in steroid metabolism (e.g., Fshb, Lhb, and Giot1). Third, genes involved in cell proliferation and cell death were upregulated in the midbrain VTA of mated versus non-mated rats. These findings support a great deal of our prior research that has demonstrated a role of steroid biosynthesis and actions at GABAergic, glutamatergic, dopaminergic substrates, and/or downstream signaling factors. Thus, mating alters expression of genes associated with steroid biosynthesis and non-traditional steroid actions in rat midbrain.

PXR, an endogenous target of 3α,5α-THP, may underlie biosynthesis in response to mating

The data discussed to this point suggest that 3α,5α-THP plays a causal role in mediating expression of affective and motivated behaviors. Further, paced mating is one behavioral stimulus that underlies 3α,5α-THP biosynthesis in brain regions, such as the midbrain VTA, cortex, hippocampus, and striatum, that are relevant for these behaviors. Other factors that remain to be elucidated in this regulatory circuit within the midbrain VTA to modulate affective and motivated behaviors are of great scientific and clinical interest. The data that support involvement of a novel pregnane mechanism, the pregnane xenobiotic receptor (PXR), that has actions to modulate steroid synthesis within the brain are discussed as follows.

3α,5α-THP is an endogenous positive activator of PXR. The PXR receptor is a nuclear receptor that acts as a transcription factor, and facilitates the expression of several major families of genes. Genes of particular relevance are the cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes (involved in steroid and neurosteroid biosynthesis, as well as metabolism of a broad array of drugs), and of ATP-binding cassette transporters, which also have broad functions in several sites, including the blood–brain barrier. The rodent PXR is analogous to the steroid and xenobiotic receptor in humans, a.k.a. the human-PXR (Xie and Evans, 2002). Enhancing gestational levels of 3α,5α-THP can increase whole brain expression of PXR mRNA in offspring (Mellon et al., 2008). While PXR is most often studied in the liver owing to its integral role in metabolism, PXR has been found using real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) and Western Blotting in the rabbit cortex, midbrain, and cerebellum (Marini et al., 2007), rat brain capillaries (Bauer et al., 2004), and various regions of the human brain (Lamba et al., 2004). Moreover, we have found that PXR is expressed in the midbrain of rats, as described as follows.

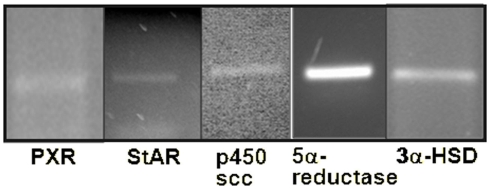

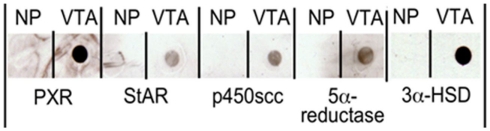

We have recently conducted microarray analyses on flash frozen midbrain tissue of rats that were paced mated or not mated. mRNA was isolated from midbrain tissues, reverse transcribed into labeled cDNAs, hybridized, and used to probe the Affymetrix GeneChip Rat 230 2.0 arrays per Affymetrix protocol. Analysis showed the presence of PXR gene in rat midbrain VTA (Table 1). We have gone on to confirm this microarray data and taken it a step further to investigate whether PXR RNA and protein, as well as the protein and RNA from downstream metabolism enzymes involved in 3α5α-THP formation that may be regulated by PXR, are present in the VTA. We have used qPCR to confirm the presence of PXR, StAR, P450scc, 3α-HSD, and 5α-reductase seen in our microarray studies. We isolated total RNA from flash frozen rat midbrain tissue using Tri-Reagent (Ambion). We then used the Ambion MicroPoly(A)Pure™ (Ambion) and the iScript Select RT (reverse transcriptase) kit (Bio-Rad) to generate cDNAs from mRNA. Primers for PCR were designed to differentiate between cDNAs and genomic contamination (we observed no contamination). We found that PXR as well as StAR, P450scc, 3α-HSD, and 5α-reductase mRNAs are all present in the rat midbrain VTA (Figure 4; Table 1).

Table 1.

Expression confirmed in midbrain VTA of proestrous rats for pregnane xenobiotic receptor (PXR) and biosynthesis and metabolism proteins/enzymes required for 3α,5α-THP formation [steroid acute regulatory protein (StAR), P450 side chain cleavage enzyme (P450scc), 5α-reductase, and 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3α-HSD)].

| PXR | StAR | P450scc | 5α-Reductase | 3α-HSD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA on microarray | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| mRNA confirmed with qPCR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Protein on westerns | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Figure 4.

Agarose gels to visualize bands from qPCR confirming that mRNAs for pregnane xenobiotic receptor (PXR) and its possible downstream effectors, steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR), P450 side chain cleavage enzyme (P450scc), 5α-reductase (5α-red), and 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3α-HSD) are expressed in the rat midbrain. Note: gels depicted are those run separately for each of these targets.

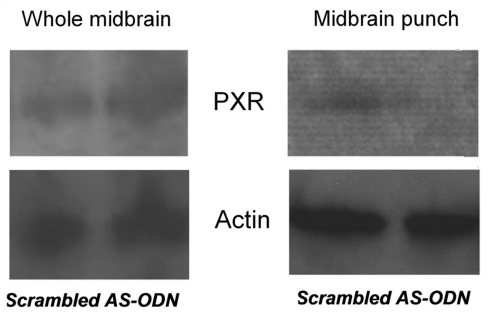

To see if these mRNAs are translated into protein, we used dot blots and antibody staining to look for protein expression in the rat midbrain VTA. For these studies, we homogenized flash frozen rat midbrain VTA tissue in NuPAGE® sample buffer (1X; Invitrogen), at a concentration of 1 mg tissue/100 μl buffer. Samples were then dot blotted onto nitrocellulose by pipetting 2 μl of homogenized sample in sample buffer onto the membrane. We then probed the blots with different concentrations (1:1000–1:5000) of 1° antibodies to PXR, StAR, P450scc, or 5α-reductase (all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and 3α-HSD, then appropriate species-specific biotinylated 2° antibodies to determine the ideal concentration of antibodies. Blots were incubated in Vector Duolux Reagent (Vector Labs), which binds to the secondary antibodies to produce a chemiluminescent peroxidase reaction that was observed following exposure to film. The representative results of these dot blots are depicted in Figure 5; Table 1.

Figure 5.

Dot blots demonstrating the presence of pregnane xenobiotic receptor (PXR), steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR), P450 side chain cleavage enzymes (P450scc), 5α-reductase, and 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3α-HSD) in the rat midbrain VTA. NP indicates no protein.

We observed expression of PXR, StAR, P450scc, 5α-reductase, and 3α-HSD protein in the midbrain. We have more recently investigated whether there are differences in expression of PXR in diestrous and proestrous rats (Frye et al., 2010). These experiments have shown that rats in proestrus have higher mRNA and protein expression of PXR in the midbrain than do diestrous rats (Frye et al., 2010). Indeed, mRNA and/or protein for PXR, StAR, P450scc, 3β-HSD, 5α-reductase, and 3α-HSD are present in the rat midbrain, and PXR expression is altered by hormonal status.

Manipulating PXR in the midbrain alters affective and motivated behaviors

We have begun to assess the functional effects of PXR in the VTA for affective and motivated behaviors. In one study, we compared the effects of PXR ligands to the VTA of OVX rats. In this study, OVX, E2-primed rats were stereotaxically implanted with bilateral guide cannulae aimed at the VTA. Rats were infused with β-cyclodextrin vehicle or a positive modulator of PXR (3α,5α-THP, 3α,5β-THP, 3β,5α-THP, or RU-486) and then tested in the paced mating task 10 min later. Infusions of the PXR-positive modulators, compared to vehicle, increased lordosis responding (Frye, 2011).

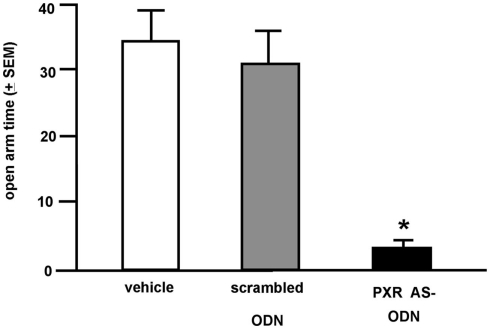

Although the data above imply that activating PXR in the midbrain VTA may facilitate lordosis, the effects of knocking down PXR in the VTA are of interest. To further assess the role of PXR in the VTA for affective and motivated behavior, we infused OVX, E2-primed (10 μg) rats with either a PXR antisense oligodeoxynucleotides (ODN; 5′ CTTGCGGAAGGGGCACCTCA 3′; 250 ng) or a scrambled mis-sense ODN (5′ CTCCGAAACGGACATCTGA 3′; 250 ng), or saline vehicle, bilaterally to the VTA. ODNs were infused 44, 24, and 0 h prior to testing in the elevated plus maze and paced mating tasks. The site-specificity for the effects of these manipulations was determined. Brains of OVX, E2-primed rats that had scrambled ODNs or PXR antisense ODNs infused to the VTA were immediately collected after behavioral testing, flash frozen on dry ice, and stored at −80°C until prepared for western blotting analyses. Tissues have only been analyzed to date for those with confirmed infusions to the VTA. Briefly, tissues were dissected by one of two methods. First, the block of midbrain tissue (inclusive of red nucleus, interpeduncular nucleus, substantia nigra) was grossly dissected (typical weight 25–30 mg). Second, brains were sectioned anterior and posterior to the infusion site and midbrain VTA was “punched out” (typical weight 2–3 mg of tissue). PXR expression was determined in midbrain or VTA tissue via western blotting using the same general techniques described above for tissue preparation, antibody incubation, blocking, and visualization. Specific to this experiment, to optimize concentrations of primary and secondary antibodies for PXR, dot blot analyses on positive control tissues (liver) were conducted first. These blots were blocked in 5% milk PBS-10% tween and then incubated in PXR mouse 1° (1:1000–1:5000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and HRP conjugated goat anti-mouse 2° (1:5000–1:20000; Bio-Rad) antibodies. This experiment determined that the ideal concentration for 1° PXR antibody was 1:3000 and 2° was 1:5000. These concentrations were then used to determine PXR protein concentrations in midbrain tissue samples with typical gel electrophoresis separation and transfer to nitrocellulose (as described in Frye, 2011). VTA punches, but not gross midbrain dissections, demonstrated that PXR expression was reduced following infusions of the PXR antisense ODNs compared to scrambled control infusions (Figure 6). These data support the notion that VTA is a central area within the midbrain underlying neurosteroidogenesis of 3α,5α-THP and that PXR’s effects on associated behaviors are site-specific and relegated to the VTA. These findings are congruous with the hypothesis that PXR is critical for 3α,5α-THP formation in this region.

Figure 6.

Western blots of pregnane xenobiotic receptor (PXR) expression (top) and β-actin control (bottom) in the whole midbrain (left) and punch VTA infusion site (right) of rats administered scrambled control or PXR antisense oligodeoxynucleotides (ODNs).

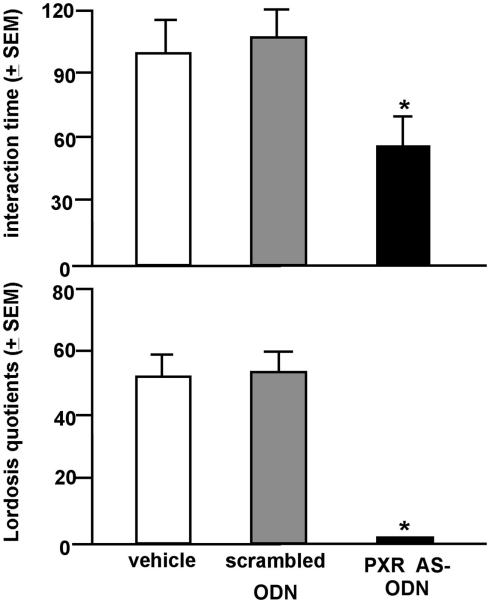

Rats infused with the antisense ODN spent significantly less time on the open arms of the elevated plus maze, indicating less anti-anxiety behavior compared to controls (Figure 7). Additionally, rats infused with PXR antisense ODN to the VTA spent less time in social interaction with a conspecific and demonstrated less lordosis compared to controls, indicating less pro-social and motivated, and reproductive behavior among these rats (Figure 8). Infusions outside the VTA did not produce the same effects (Table 2). Together with the western blotting data, these findings demonstrate that PXR knock-down can be achieved locally in the VTA and that reduction of PXR protein in this area is sufficient to attenuate 3α,5α-THP-dependent anti-anxiety and social behavior.

Figure 7.

Affective behavior in the elevated plus maze of E2-primed rats administered scrambled control or pregnane xenobiotic receptor (PXR) antisense oligodeoxynucleotides (ODNs) to the midbrain VTA. * Indicates different from all groups, p < 0.05.

Figure 8.

Social behavior (top: social interaction; bottom: lordosis) of E2-primed rats administered scrambled control or pregnane xenobiotic receptor (PXR) antisense oligodeoxynucleotides (ODNs) to the midbrain VTA. * Indicates different from all groups, p < 0.05.

Table 2.

Data from missed-site controls do not demonstrate reliable difference between rats infused with scrambled oligodeoxynucleotides (ODN) versus antisense ODN in elevated plus maze (open arm time), social interaction (interaction time), or paced mating (lordosis frequency).

| Behavioral measure | Missed-site infusate |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle | Scrambled ODN | PXR ASODN | |

| Time on open arm (s ± SEM) | 31 ± 7 | 26 ± 13 | 41 ± 2 |

| Interaction time (s ± SEM) | 115 ± 10 | 101 ± 20 | 99 ± 5 |

| Lordosis frequency (mean ± SEM) | 30 ± 18 | 33 ± 13 | 27 ± 12 |

To further assess the importance of PXR in neurosteroid-enhanced lordosis, an experiment was conducted in diestrous and proestrous rats infused with PXR antisense or control conditions to the VTA, using the methods described above. In this experiment, proestrous rats infused with antisense oligonucleotides against PXR had reduced anti-anxiety and pro-social behavior, compared to rats infused with control conditions (Frye et al., 2010). PXR antisense oligonucleotides to the VTA of diestrous rats did not alter these behavioral endpoints. Western blot analyses and qPCR demonstrated that these infusions to the VTA of PXR antisense oligonucleotides were effective in knocking down PXR protein and mRNA expression in the VTA (Frye et al., 2010). Moreover, PXR antisense oligonucleotides to the VTA of proestrous rats significantly reduced 3α,5α-THP levels in the midbrain coincident with these behavioral changes. Thus, PXR may be necessary for 3α,5α-THP formation in the VTA, and its subsequent effects on affective and motivated behaviors.

Together, these preliminary findings demonstrate that antisense ODNs infused to the midbrain VTA knock-down PXR expression locally in the VTA and that this local PXR attenuation is necessary for expression of anti-anxiety and motivated, social behavior among OVX E-primed rats. Of continued interest in the laboratory is the precise role of PXR. PXR expression studies suggest that there may be positive feedback from gonadal hormones and/or 3α,5α-THP on PXR in the midbrain, which in turn regulates downstream enzymes required for 3α,5α-THP formation. Interestingly, these results suggest that there may be some genomic signaling in the midbrain for non-traditional actions of 3α,5α-THP, but that these occur through PXR, rather than PRs (as discussed in see Mechanisms of 3α,5α-THP for Affect and Motivated Behaviors). The extent to which these effects are mediated by 3α,5α-THP, and the functional role of PXR in this system, are currently being investigated further in our laboratory.

Summary

To summarize, the neurosteroid, 3α,5α-THP, has myriad effects, mechanisms, and sources beyond the typically described actions of progestogens. The VTA is a central target of progestogens for their effects and mechanisms related to affective, motivated, and reward processes. A compelling question is the source of progestogens in the VTA for these processes. A focus has been on the role of PXR in the midbrain VTA. The midbrain VTA expresses RNA and proteins for PXR and downstream metabolism enzymes that are rate-limiting factors for 3α,5α-THP production. Infusions of positive modulators of PXR to the VTA facilitate sexual behavior. Infusions of antisense ODNs targeted against PXR to the VTA inhibit anti-anxiety and sexual behavior of rats. Together, these data support the idea that PXR is expressed in the midbrain VTA and that it may have a functionally relevant role in the affective and social behaviors examined to date. Indeed, PXR may be a powerful mechanism involved in the modulation of neurosteroid effects, which may mediate diverse human behaviors and clinical conditions (e.g., anxiety, depression, drug abuse). The previous studies by our lab have elucidated a critical role of 3α,5α-THP in the VTA in mediating a number of affective and social behaviors in rats. The ongoing focus of our lab is the conditions under which biosynthesis of 3α,5α-THP is initiated, and how these processes result from environmental stimuli, behaviors and/or drugs, and involve PXR.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH0676980; RMH067698B). Assistance provided by Dr. Sridar Chittur, Alima DeVerteuil, Amy Kohtz, Carolyn Koonce, and Jennifer Torgersen is appreciated.

References

- Abel K. M., Drake R., Goldstein J. M. (2010). Sex differences in schizophrenia. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 22, 417–428 10.3109/09540261.2010.515205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altemus M., Redwine L. S., Leong Y. M., Frye C. A., Porges S. W., Carter C. S. (2001). Responses to laboratory psychosocial stress in postpartum women. Psychosom. Med. 63, 814–821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altomare G., Capella G. L. (2002). Depression circumstantially related to the administration of finasteride for androgenetic alopecia. J. Dermatol. 29, 665–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angold A., Costello E. J., Erkanli A., Worthman C. M. (1999). Pubertal changes in hormone levels and depression in girls. Psychol. Med. 29, 1043–1053 10.1017/S0033291799008946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anker J. J., Holtz N. A., Zlebnik N., Carroll M. E. (2009). Effects of allopregnanolone on the reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in male and female rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 203, 63–72 10.1007/s00213-008-1371-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anker J. J., Zlebnik N. E., Carroll M. E. (2010). Differential effects of allopregnanolone on the escalation of cocaine self-administration and sucrose intake in female rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 212, 419–429 10.1007/s00213-010-1968-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bäckström T., Andersson A., Andreé L., Birzniece V., Bixo M., Björn I., Haage D., Isaksson M., Johansson I. M., Lindblad C., Lundgren P., Nyberg S., Odmark I. S., Strömberg J., Sundström-Poromaa I., Turkmen S., Wahlström G., Wang M., Wihlbäck A. C., Zhu D., Zingmark E. (2003). Pathogenesis in menstrual cycle-linked CNS disorders. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1007, 42–53 10.1196/annals.1286.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bäckström T., Sanders D., Leask R., Davidson D., Warner P., Bancroft J. (1983). Mood, sexuality, hormones, and the menstrual cycle. II. Hormone levels and their relationship to the premenstrual syndrome. Psychosom. Med. 45, 503–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baghai T. C., di Michele F., Schüle C., Eser D., Zwanzger P., Pasini A., Romeo E., Rupprecht R. (2005). Plasma concentrations of neuroactive steroids before and after electroconvulsive therapy in major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 30, 1181–1186 10.1038/sj.npp.1300684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbaccia M. L., Roscetti G., Trabucchi M., Mostallino M. C., Concas A., Purdy R. H., Biggio G. (1996). Time-dependent changes in rat brain neuroactive steroid concentrations and GABAA receptor function after acute stress. Neuroendocrinology 63, 166–172 10.1159/000126953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbaccia M. L., Roscetti G., Trabucchi M., Purdy R. H., Mostallino M. C., Concas A., Biggio G. (1997). The effects of inhibitors of GABAergic transmission and stress on brain and plasma allopregnanolone concentrations. Br. J. Pharmacol. 120, 1582–15288 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbaccia M. L., Serra M., Purdy R. H., Biggio G. (2001). Stress and neuroactive steroids. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 46, 243–272 10.1016/S0074-7742(01)46065-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer B., Hartz A. M., Fricker G., Miller D. S. (2004). Pregnane X receptor up-regulation of P-glycoprotein expression and transport function at the blood-brain barrier. Mol. Pharmacol. 66, 413–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baulieu E. E. (1991). Neurosteroids: a new function in the brain. Biol. Cell 71, 3–10 10.1016/0248-4900(91)90045-O [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baulieu E. E. (1980). Steroid hormone receptors. Expos. Annu. Biochim. Med. 34, 1–25 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker J. B., Cha J. H. (1989). Estrous cycle-dependent variation in amphetamine-induced behaviors and striatal dopamine release assessed with microdialysis. Behav. Brain Res. 35, 117–125 10.1016/S0166-4328(89)80112-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belelli D., Lambert J. J. (2005). Neurosteroids: endogenous regulators of the GABAA receptor. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6, 565–575 10.1038/nrn1703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benavides J., Quarteronet D., Imbault F., Malgouris C., Uzan A., Renault C., Dubroeucq M. C., Gueremy C., Le Fur G. (1983). Labelling of “peripheral-type” benzodiazepine binding sites in the rat brain by using [3H]PK 11195, an isoquinoline carboxamide derivative: kinetic studies and autoradiographic localization. J. Neurochem. 41, 1744–1750 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1983.tb00888.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bicikova M., Putz Z., Hill M., Hampl R., Diebbelt L., Tallova J., Starka L. (1998). Serum levels of neurosteroid allopregnanolone in patients with premenstrual syndrome and patients after thyroidectomy. Endocr. Regul. 32, 87–92 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitran D., Foley M., Audette D., Leslie N., Frye C. A. (2000). Activation of peripheral mitochondrial benzodiazepine receptors in the hippocampus stimulates allopregnanolone synthesis and produces anxiolytic-like effects in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 151, 64–71 10.1007/s002130000472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitran D., Hilvers R. J., Kellogg C. K. (1991). Anxiolytic effects of 3α-hydroxy-5α[β]-pregnan-20-one: endogenous metabolites of progesterone that are active at the GABAA receptor. Brain Res. 561, 157–161 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90761-J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaustein J. D., Tetel M. J., Ricciardi K. H., Delville Y., Turcotte J. C. (1994). Hypothalamic ovarian steroid hormone-sensitive neurons involved in female sexual behavior. Psychoneuroendocrinology 19, 505–516 10.1016/0306-4530(94)90036-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyson S. J., McGonigle P., Molinoff P. B. (1986). Quantitative autoradiographic localization of the D1 and D2 subtypes of dopamine receptors in rat brain. J. Neurosci. 6, 3177–3188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady K. T., Randall C. L. (1999). Gender differences in substance use disorders. Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 22, 241–252 10.1016/S0193-953X(05)70074-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braestrup C., Squires R. F. (1977). Specific benzodiazepine receptors in rat brain characterized by high-affinity [3H]diazepam binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 74, 3805–3809 10.1073/pnas.74.9.3805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brambilla F., Biggio G., Pisu M. G., Bellodi L., Perna G., Bogdanovich-Djukic V., Purdy R. H., Serra M. (2003). Neurosteroid secretion in panic disorder. Psychiatry Res. 118, 107–116 10.1016/S0165-1781(03)00074-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brot M. D., Akwa Y., Purdy R. H., Koob G. F., Britton K. T. (1997). The anxiolytic-like effects of the neurosteroid allopregnanolone: interactions with GABA(A) receptors. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 325, 1–7 10.1016/S0014-2999(97)00096-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown G. W., Harris T. O., Hepworth C. (1994). Life events and endogenous depression. A puzzle reexamined. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 51, 525–534 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950070017006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter M. J., Upadhyaya H. P., LaRowe S. D., Saladin M. E., Brady K. T. (2006). Menstrual cycle phase effects on nicotine withdrawal and cigarette craving: a review. Nicotine Tob. Res. 8, 627–638 10.1080/14622200600910793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll B. J., Curtis G. C., Mendels J. (1976). Neuroendocrine regulation in depression. II. Discrimination of depressed from nondepressed patients. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 33, 1051–1058 10.1001/archpsyc.1976.01770090041003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll B. J., Greden J. F., Feinberg M., Lohr N., James N. M., Steiner M., Haskett R. F., Albala A. A., DeVigne J. P., Tarika J. (1981). Neuroendocrine evaluation of depression in borderline patients. Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 4, 89–99 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudron L. H., Klein M. H., Remington P., Palta M., Allen C., Essex M. J. (2001). Predictors, prodromes and incidence of postpartum depression. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 22, 103–112 10.3109/01674820109049960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M. K., Guilarte T. R. (2008). Translocator protein 18 kDa (TSPO): molecular sensor of brain injury, and repair. Pharmacol. Ther. 118, 1–17 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y. J., Karavolas H. J. (1973). Conversion of progesterone to 5α-pregnane-3,20-dione and 3α-hydroxy-5α-pregnan-20-one by rat medical basal hypothalami and the effects of estradiol and stage of estrous cycle on the conversion. Endocrinology 93, 1157–1162 10.1210/endo-93-5-1157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford G. M., Farmer R. D. (2002). Drug or symptom-induced depression in men treated with α1-blockers for benign prostatic hyperplasia? A nested case-control study. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 11, 55–61 10.1002/pds.671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compagnone N. A., Mellon S. H. (2000). Neurosteroids: biosynthesis and function of these novel neuromodulators. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 21, 1–56 10.1006/frne.1999.0188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyr M., Ghribi O., Di Paolo T. (2000). Regional and selective effects of oestradiol and progesterone on NMDA and AMPA receptors in the rat brain. J. Neuroendocrinol. 12, 445–452 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2000.00471.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Leo V., la Marca A., Talluri B., D’Antona D., Morgante G. (1998). Hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis and adrenal function before and after ovariectomy in premenopausal women. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 138, 430–435 10.1530/eje.0.1380430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBold J. F., Frye C. A. (1994). Genomic and non-genomic actions of progesterone in the control of female hamster sexual behavior. Horm. Behav. 28, 445–453 10.1006/hbeh.1994.1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong E., Matsumoto K., Uzunova V., Sugaya I., Takahata H., Nomura H., Watanabe H., Costa E., Guidotti A. (2001). Brain 5α-dihydroprogesterone and allopregnanolone synthesis in a mouse model of protracted social isolation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 2849–2854 10.1073/pnas.051628598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubrovsky B. (2006). Neurosteroids, neuroactive steroids, and symptoms of affective disorders. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 84, 644–655 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J., Amsterdam J., Eriksson E., Frank E., Freeman E., Hirschfeld R., Ling F., Parry B., Pearlstein T., Rosenbaum J., Rubinow D., Schmidt P., Severino S., Steiner M., Stewart D. E., Thys-Jacobs S. (1999). Is premenstrual dysphoric disorder a distinct clinical entity? J. Womens Health Gend. Based Med. 8, 663–679 10.1089/jwh.1.1999.8.663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epperson C. N., Haga K., Mason G. F., Sellers E., Gueorguieva R., Zhang W., Weiss E., Rothman D. L., Krystal J. H. (2002). Cortical gamma-aminobutyric acid levels across the menstrual cycle in healthy women and those with premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 59, 851–858 10.1001/archpsyc.59.9.851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erskine M. S., Kornberg E. (1992). Stress and ACTH increase circulating concentrations of 3α-androstanediol in female rats. Life Sci. 51, 2065–2071 10.1016/0024-3205(92)90157-K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eser D., di Michele F., Zwanzger P., Pasini A., Baghai T. C., Schüle C., Rupprecht R., Romeo E. (2005). Panic induction with cholecystokinin-tetrapeptide (CCK-4) Increases plasma concentrations of the neuroactive steroid 3α,5α-tetrahydrodeoxycorticosterone (3α,5α-THDOC) in healthy volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology 30, 192–195 10.1038/sj.npp.1300572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]