Abstract

The study aim was to test whether the metabolic syndrome or its components predicted cognitive decline among persons aged 80 years and older (mean 85.0 years). Participants were members of the “Keys to Optimal Cognitive Aging Project,” a prospective cohort study in Okinawa, Japan. Metabolic syndrome was assessed at baseline. Cognitive functions were assessed annually for up to 3 years. One hundred and forty-eight participants completed at least one follow-up with 101 participating in all three assessments and 47 participating in two of the three assessments. The mean and median duration of follow-up were 1.8 and 2 years, respectively. Metabolic syndrome and four components were not associated with decline in global and executive cognitive functions. However, high glycosylated hemoglobin was associated with decline in memory function at the second follow-up. Our study supports accumulating evidence that the positive association between metabolic syndrome and cognitive function might not hold for the oldest old.

Keywords: Metabolic syndrome, Cognitive decline, Oldest old, Longitudinal study, Okinawa

The number of older adults with cognitive impairment or dementia is expected to rise dramatically due to an aging population (1). It is critical, therefore, to identify modifiable risk factors for cognitive decline. It is widely acknowledged that risk factors for cardiovascular disease play a role in the development of dementia, both Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and vascular dementia (VaD) (2–12). Although several studies reported that metabolic syndrome, defined as a cluster of cardiovascular disease risk factors, including abdominal obesity (7,11), hypertriglyceridemia (6), low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) level (6), hypertension (2–5,8), and hyperglycemia (4,8,11), has been associated with increased risk of cognitive impairment, the association appears to depend on age. Metabolic syndrome usually increases risk of cognitive decline among younger old adults (ages 65–74 years), but as the age of study participants increases further, the association begins to diminish (6,10,11). Among those in their mid-80s and beyond, often referred to as the oldest old, the association can disappear or reverse (13,14).

Similarly, several components used to define metabolic syndrome have paradoxical effects in the oldest old. For example, at middle age, obesity is generally associated with increased risk of later life dementia (7), yet in the oldest old, both abdominal obesity and higher body mass index (BMI) have been associated with a reduced risk of later life dementia (15,16). Hyperlipidemia is associated with cognitive impairment among younger to mid-older persons (9). In the oldest old, however, at least one study did not support this association (17). Hypertension at middle age is also a risk factor for cognitive decline and dementia in later life (3–5,8). On the other hand, among the oldest old, low blood pressure rather than high blood pressure is found to be a risk factor for the development of dementia (18,19). In sum, the protective effects of lower triglycerides, blood pressure, and BMI in midlife to early old age against later life cognitive decline appear to be less robust or even reverse in the oldest old populations. The reasons are unclear. The paradoxical change in metabolic syndrome’s association with several age-related diseases and, in some studies, with overall mortality has been referred to as “reverse metabolic syndrome” and has been hypothesized to represent an evolutionary adaptation to prolong human life after reproduction (20). Interestingly, little is known about these relations in long-lived Japanese populations who have traditionally had more VaD and less Alzheimer’s dementia than Western populations (21) and thus might be more susceptible to metabolic syndrome-related cognitive effects.

Therefore, the aim of the current study was to prospectively explore the association between the metabolic syndrome (and its components) and later life cognitive decline among functionally independent community-dwelling older adults aged 80 years and older and free from cognitive impairment at baseline in Japan’s Okinawa prefecture—a population known for their longevity (22). The Okinawans are of particular interest because their cardiometabolic risk factors have risen at the fastest pace in Japan over the past few decades (23) yet little is known about the effects of this on cognitive function.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were members of the Keys to Optimal Cognitive Aging Project (KOCOA), a prospective pilot cohort study of community-dwelling older people aged 80 years or older living in Ginowan City in Okinawa, Japan. The study was conducted annually between November 2007 and March 2010 and consisted of three time points (baseline and two follow-ups). A detailed description of the recruitment process has been presented elsewhere (24). Briefly, researchers visited 22 senior centers, explained the study protocol, and asked them to participate in the study. Senior centers, funded by the municipal government, offer various activities to the local seniors, which include handicrafts, games, traditional dance, and occasional lectures on topics of interest to the seniors. A request to join the study was made at the conclusion of each presentation. There were 196 volunteers, aged 80 years and older (mean age: 85.2 years, range: 80–98 years), who participated in the KOCOA study. The participants underwent a clinical examination at baseline and a face-to-face interview either in their local senior center or in their home at baseline and follow-up.

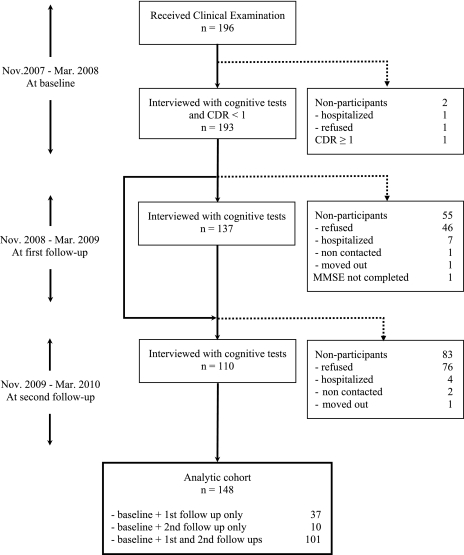

In the current study, we excluded those with frank dementia defined as Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR) (25) greater than or equal to 1.0 at baseline. Attrition rates were 29.0% from baseline to the first follow-up and 19.7% from the first to the second follow-up (Figure 1). Of 193 nondemented participants, 148 completed at least one follow-up and were featured in the current analysis. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of University of the Ryukyus, the Institutional Review Board at the Oregon Health & Science University, and informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the enrollment in the study.

Figure 1.

Flow of participants.

Metabolic Syndrome

Presence of the metabolic syndrome at baseline was determined according to a minimally modified version of the National Cholesterol Education Program Third Adult Treatment Panel guidelines (26) as having three or more of the following conditions: BMI 25 kg/m2 or more, triglyceride level 150 mg/dL or more, HDL-C level less than 40 mg/dL in men and less than 50 mg/dL in women, systolic blood pressure 130 mmHg or more and diastolic blood pressure 85 mmHg or more or currently taking antihypertensive medication, and glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level 5.4% or more or currently taking diabetes medication.

For the current study, BMI was used instead of waist circumference, which was not measured, with a cutoff value of 25 kg/m2 or more according to guidelines published by the Japan Society for the Study of Obesity (27). Because fasting blood glucose level was not available, HbA1c level of 5.4% or more was used instead of fasting plasma glucose level 110 mg/dL or more (28,29).

Cognitive Tests

Cognitive function was assessed by a trained interviewer at baseline and at the follow-up examinations using the Japanese version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (JMMSE) (30,31), the Verbal Fluency Initial Letter (VFL), and the Scenery Picture Memory Test (SPMT) (32). The JMMSE is a measure of global cognitive function and ranges from 0 to 30 points, with higher scores representing better cognitive function. Because the distribution of JMMSE was not normal, we transformed using the square root of the number of errors. The VFL (33) was used to measure executive function. This test requires the participant to generate words beginning with letter “Ka” (in Japanese) in 60 seconds and has been used widely in Japan as an equivalent test to Initial Letter Fluency by Lezak (33). The SPMT is a measure of memory function and has been described in detail elsewhere (32).

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons of baseline characteristics of those with and without the metabolic syndrome were performed using t test for continuous variables and Pearson chi-square test for categorical variables. We used mixed-effects models to examine the association between the metabolic syndrome, its components, and cognitive test scores (outcome variables) over time. Mixed-effects models account for within-subject correlations among repeated cognitive measurements and accommodate missing data without removing the individual from the analysis (34). The mixed-effects model consists of two parts: fixed effects and random effects. Fixed effects describe the population average of baseline or trajectories, and random effects describe the participant-specific heterogeneity in those measures. The trajectory of the cognitive test scores over time may be nonlinear because of the stress of the test situation at baseline and/or the learning effect over time. Therefore, the models included two dummy variables representing follow-up time periods (first follow-up, second follow-up, with baseline as a reference) instead of continuous time as random effects. The interaction of the time dummies (treated as random effects) with the metabolic syndrome or its components status was included to represent the additional impact of the metabolic syndrome or its components status on the cognitive test scores at each time point. The detailed statistical model appears in the Appendix 1. We ran separate models for each of the three cognitive test scores (as an outcome) and six metabolic syndrome states, that is, metabolic syndrome itself and five components (as predictors) and their interactions with time. Statistical significance was set as p < .0083, the Bonferroni multiple comparisons–adjusted p value. For the JMMSE, we used the square root of the number of errors, as expressed by (30 − JMMSE)1/2, to normalize the distribution (35,36). Thus, an increase in this transformed variable with time indicated cognitive decline (ie, increased numbers of errors). The normality of the transformed JMMSE score and other two test scores was confirmed by visual inspection of the distributions and Q-Q plots. All models were adjusted for age, gender, and years of education. All analyses were conducted with SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

We compared the participants followed (n = 148) and not followed (n = 45). The two groups did not differ in demographic characteristics (age: p = .155, years of education: p = .332 based on Student’s t test, and gender: p = .669 based on Pearson chi-square test), the metabolic syndrome and its components (metabolic syndrome: p = .596, BMI: p = .845, triglycerides: p = .863, HDL-C: p = .849, blood pressure: p = .296, HbA1c: p = .253 based on Pearson chi-square test), and the score of CDR (0 vs 0.5) and SPMT (CDR: p = .2318 based on Pearson chi-square test, SPMT: p = .153 based on Student’s t test). Those not followed had lower baseline scores of JMMSE and VFL (JMMSE: p < .001, VFL: p = .018).

The mean (SD) age of the participants at baseline was 85.0 (3.2), and 74.3% were women. A total of 49 participants (33.1%) met the metabolic syndrome criteria of whom 33 participants (67.3%) had 3, 11 participants (22.5%) had 4, and 5 participants (10.2%) met 5 of the criteria used to define metabolic syndrome. High blood pressure and high HbA1c were very common. Baseline JMMSE error score was similar between the two groups (those with and without metabolic syndrome), but baseline VFL score differed between the groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Analytic Cohort (n = 148)

| Metabolic Syndrome | ||||

| Variables | Total, n = 148 | Without, n = 99 | With, n = 49 | p Value* |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, M ± SD | 85.0 ± 3.2 | 85.0 ± 3.1 | 84.9 ± 3.4 | .927 |

| Women, n (%) | 110 (74.3) | 73 (73.7) | 37 (75.5) | .816 |

| Years of education, M ± SD | 7.4 ± 2.3 | 7.3 ± 2.2 | 7.4 ± 2.4 | .834 |

| Individual criterion used for metabolic syndrome, n (%)† | ||||

| High BMI | 55 (37.2) | 18 (18.2) | 37 (75.5) | <.001 |

| High triglycerides | 28 (18.9) | 4 (4.0) | 24 (49.0) | <.001 |

| Low HDL-C | 18 (12.2) | 2 (2.0) | 16 (32.7) | <.001 |

| High blood pressure | 95 (64.2) | 50 (50.5) | 45 (91.8) | <.001 |

| High HbA1c | 93 (62.8) | 47 (47.5) | 46 (93.9) | <.001 |

| Cognitive test | ||||

| JMMSE, M ± SD | 23.9 ± 3.8 | 23.8 ± 3.2 | 24.1 ± 3.6 | .683 |

| VFL, M ± SD | 6.4 ± 2.9 | 6.7 ± 2.6 | 5.7 ± 2.1 | .035 |

| SPMT, M ± SD | 7.2 ± 2.8 | 7.4 ± 2.9 | 6.8 ± 2.5 | .257 |

Notes: BMI = body mass index; HbA1c = glycosylated hemoglobin; HDL-C = high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; JMMSE = Japanese version of Mini-Mental State Examination; SPMT = Scenery Picture Memory Test; VFL = Verbal Fluency Initial Letter.

Pearson chi-square test for categorical variables and Student’s t test for continuous variables.

High BMI is defined as BMI 25 kg/m2 or more, high triglycerides as triglycerides level 150 mg/dL or more, low HDL-C as HDL-C level less than 40 mg/dL in men and less than 50 mg/dL in women, high blood pressure as systolic blood pressure 130 mmHg or more and diastolic blood pressure 85 mmHg or more or taking an antihypertensive medication, and high HbA1c as glycosylated hemoglobin level 5.4% or more or taking an antidiabetic medication.

Global Cognitive Function (JMMSE)

The participants generally showed fewer errors in JMMSE at the second follow-up, but the interaction of the time (first and second follow-up) and metabolic syndrome or each component of metabolic syndrome was all insignificant, suggesting that there was no difference in changes in number of errors of JMMSE between the two groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Association Between the Metabolic Syndrome and the Square Root of the Number of Errors in the JMMSE*

| Model Terms† | Estimate | SE | p Value‡ |

| Metabolic syndrome | |||

| Metabolic syndrome | −0.061 | 0.128 | .632 |

| Time1 (first follow-up) | −0.175 | 0.082 | .035 |

| Time2 (second follow-up) | −0.208 | 0.081 | .011 |

| Metabolic syndrome × Time1 | 0.111 | 0.144 | .443 |

| Metabolic syndrome × Time2 | 0.142 | 0.139 | .310 |

| BMI | |||

| High BMI | −0.018 | 0.126 | .889 |

| Time1 (first follow-up) | −0.090 | 0.085 | .294 |

| Time2 (second follow-up) | −0.228 | 0.082 | .006 |

| High BMI × Time1 | −0.131 | 0.140 | .350 |

| High BMI × Time2 | 0.190 | 0.136 | .165 |

| Triglycerides level | |||

| High triglycerides | 0.150 | 0.154 | .330 |

| Time1 (first follow-up) | −0.148 | 0.075 | .050 |

| Time2 (second follow-up) | −0.196 | 0.074 | .009 |

| High triglycerides × Time1 | 0.053 | 0.175 | .762 |

| High triglycerides × Time2 | 0.163 | 0.161 | .315 |

| HDL-C level | |||

| Low HDL-C | 0.026 | 0.188 | .889 |

| Time1 (first follow-up) | −0.136 | 0.072 | .060 |

| Time2 (second follow-up) | −0.146 | 0.071 | .043 |

| Low HDL-C × Time1 | −0.015 | 0.214 | .943 |

| Low HDL-C × Time2 | −0.100 | 0.191 | .600 |

| Blood pressure | |||

| High blood pressure | 0.047 | 0.127 | .709 |

| Time1 (first follow-up) | −0.118 | 0.112 | .294 |

| Time2 (second follow-up) | −0.086 | 0.112 | .446 |

| High blood pressure × Time1 | −0.032 | 0.140 | .819 |

| High blood pressure × Time2 | −0.114 | 0.139 | .413 |

| HbA1c level | |||

| High HbA1c | −0.016 | 0.125 | .900 |

| Time1 (first follow-up) | −0.240 | 0.111 | .033 |

| Time2 (second follow-up) | −0.190 | 0.105 | .071 |

| High HbA1c × Time1 | 0.159 | 0.140 | .257 |

| High HbA1c × Time2 | 0.047 | 0.135 | .726 |

Notes: BMI = body mass index; HbA1c = glycosylated hemoglobin; HDL-C = high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; JMMSE = Japanese version of Mini-Mental State Examination.

An increase in the square root of the number of errors in the JMMSE with time indicates cognitive decline.

Separate mixed-effects models for the metabolic syndrome or each component controlling for age, gender, and years of education.

Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons of six metabolic syndrome states (metabolic syndrome itself and five components) sets significant level at p < .0083.

Executive Cognitive Function (VFL)

The metabolic syndrome and its components were not associated with baseline and changes in VFL score, the latter indicated by nonsignificant interaction terms with first and second follow-up (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association Between the Metabolic Syndrome and the Verbal Fluency Initial Letter

| Model Terms* | Estimate | SE | p Value† |

| Metabolic syndrome | |||

| Metabolic syndrome | −1.098 | 0.443 | .014 |

| Time1 (first follow-up) | −0.073 | 0.258 | .777 |

| Time2 (second follow-up) | 0.132 | 0.320 | .680 |

| Metabolic syndrome × Time1 | −0.129 | 0.454 | .777 |

| Metabolic syndrome × Time2 | −0.399 | 0.552 | .471 |

| BMI | |||

| High BMI | −0.805 | 0.439 | .069 |

| Time1 (first follow-up) | −0.095 | 0.268 | .724 |

| Time2 (second follow-up) | −0.004 | 0.326 | .991 |

| High BMI × Time1 | −0.042 | 0.440 | .924 |

| High BMI × Time2 | −0.018 | 0.547 | .973 |

| Triglycerides level | |||

| High triglycerides | −0.527 | 0.544 | .335 |

| Time1 (first follow-up) | −0.040 | 0.235 | .866 |

| Time2 (second follow-up) | 0.091 | 0.294 | .758 |

| High Triglycerides × Time1 | −0.389 | 0.548 | .479 |

| High triglycerides × Time2 | −0.441 | 0.645 | .495 |

| HDL-C level | |||

| Low HDL-C | −0.813 | 0.658 | .219 |

| Time1 (first follow-up) | −0.183 | 0.225 | .417 |

| Time2 (second follow-up) | 0.053 | 0.283 | .851 |

| Low HDL-C × Time1 | 0.637 | 0.673 | .345 |

| Low HDL-C × Time2 | −0.341 | 0.747 | .649 |

| Blood pressure | |||

| High blood pressure | −0.839 | 0.443 | .060 |

| Time1 (first follow-up) | −0.146 | 0.350 | .677 |

| Time2 (second follow-up) | 0.399 | 0.441 | .367 |

| High blood pressure × Time1 | 0.050 | 0.441 | .909 |

| High blood pressure × Time2 | −0.614 | 0.545 | .263 |

| HbA1c level | |||

| High HbA1c | −0.561 | 0.439 | .203 |

| Time1 (first follow-up) | 0.004 | 0.351 | .991 |

| Time2 (second follow-up) | −0.074 | 0.411 | .857 |

| High HbA1c × Time1 | −0.177 | 0.441 | .689 |

| High HbA1c × Time2 | 0.106 | 0.534 | .843 |

Notes: BMI = body mass index; HbA1c = glycosylated hemoglobin; HDL-C = high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Separate mixed-effects models for the metabolic syndrome or each component controlling for age, gender, and years of education.

Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons of six metabolic syndrome states (metabolic syndrome itself and five components) sets significant level at p < .0083.

Memory Function (SPMT)

Only high HbA1c was associated with change in SPMT score indicated by significant interaction term with second follow-up (Table 4).

Table 4.

Association Between the Metabolic Syndrome and the Scenery Picture Memory Test

| Model Terms* | Estimate | SE | p Value† |

| Metabolic syndrome | |||

| Metabolic syndrome | −0.649 | 0.444 | 0.146 |

| Time1 (first follow-up) | 0.047 | 0.227 | 0.838 |

| Time2 (second follow-up) | −0.029 | 0.280 | 0.918 |

| Metabolic syndrome × Time1 | −0.035 | 0.401 | 0.931 |

| Metabolic syndrome × Time2 | −0.089 | 0.484 | 0.855 |

| BMI | |||

| High BMI | −0.536 | 0.438 | 0.222 |

| Time1 (first follow-up) | 0.066 | 0.236 | 0.780 |

| Time2 (second follow-up) | −0.204 | 0.284 | 0.474 |

| High BMI × Time1 | −0.080 | 0.387 | 0.837 |

| High BMI × Time2 | 0.399 | 0.475 | 0.403 |

| Triglycerides level | |||

| High triglycerides | −1.089 | 0.534 | 0.043 |

| Time1 (first follow-up) | 0.035 | 0.206 | 0.866 |

| Time2 (second follow-up) | −0.036 | 0.256 | 0.888 |

| High triglycerides × Time1 | 0.004 | 0.493 | 0.994 |

| High triglycerides × Time2 | −0.079 | 0.568 | 0.890 |

| HDL-C level | |||

| Low HDL-C | −0.039 | 0.653 | 0.952 |

| Time1 (first follow-up) | 0.005 | 0.199 | 0.980 |

| Time2 (second follow-up) | −0.047 | 0.246 | 0.851 |

| Low HDL-C × Time1 | 0.268 | 0.590 | 0.651 |

| Low HDL-C × Time2 | −0.081 | 0.660 | 0.902 |

| Blood pressure | |||

| High blood pressure | −0.264 | 0.441 | 0.551 |

| Time1 (first follow-up) | 0.081 | 0.309 | 0.794 |

| Time2 (second follow-up) | −0.027 | 0.387 | 0.945 |

| High blood pressure × Time1 | −0.073 | 0.388 | 0.851 |

| High blood pressure × Time2 | −0.052 | 0.479 | 0.914 |

| HbA1c level | |||

| High HbA1c | −0.095 | 0.435 | 0.828 |

| Time1 (first follow-up) | 0.023 | 0.306 | 0.939 |

| Time2 (second follow-up) | 0.654 | 0.349 | 0.064 |

| High HbA1c × Time1 | 0.015 | 0.386 | 0.968 |

| High HbA1c × Time2 | −1.201 | 0.451 | 0.008‡ |

Notes: BMI = body mass index; HbA1c = glycosylated hemoglobin; HDL-C = high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Separate mixed-effects models for the metabolic syndrome or each component controlling for age, gender, and years of education

Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons of six metabolic syndrome states (metabolic syndrome itself and five components) sets significant level at p < .0083.

p Value significant after Bonferroni adjustment.

DISCUSSION

Metabolic syndrome in midlife increases risk for later life age-related diseases (12), physical decline (37), and cognitive decline (38)—essential factors for healthy aging (39). On the contrary, the results of the current study of older adults aged 80 years and older (mean age of 85.0 years at baseline) suggest that the metabolic syndrome is not associated with cognitive decline, although we cannot conclude definitely from this study due to the relatively small sample size. During the 3 years of follow-up, we did not find differences in declines between those with and without metabolic syndrome in all three cognitive outcomes (i.e., global cognitive function as measured by JMMSE, executive function measured by the VFL, and memory function measured by the SPMT). This lack of association was observed for four of the five components of the metabolic syndrome with the exception of HbA1c. High HbA1c (defined as ≥ 5.4%) was associated with decline in memory function after 2 years.

Several studies have examined the association between the metabolic syndrome (and/or the components used to define the metabolic syndrome) and cognitive impairment, cognitive decline, or dementia in old age. The study results tend to differ depending on the age of the study population: Longitudinal studies have shown consistently that midlife obesity (7), hypertension (3,8,40), elevated total cholesterol (3,8,41), and diabetes mellitus (4,8,42) are associated with reduced cognitive function in later life. It is now well established that prevalence of these components of the metabolic syndrome in middle age increases the risk of late-life cognitive decline and dementia—including both AD and VaD.

On the other hand, there are no consistent findings to date to indicate that prevalence of the metabolic syndrome (or most of its key components) in later old age (ie, in those aged 80 plus years) is associated with subsequent cognitive decline or dementia. Some studies showed an increased risk of dementia or cognitive impairment for adults in early old age with the metabolic syndrome compared with those without (6,11). However, consistent with our findings, two previous prospective studies with large numbers of oldest old failed to show a significant association between the metabolic syndrome and cognitive decline or dementia. One study was of individuals aged 85 years or older (14), and another was a multiethnic cohort with an average age of more than 75 years (13). Two additional studies of the old–old, one with individuals aged 80 plus years (43) and another with a mean age of 76.2 years (44), respectively, reported that cognitive decline was not independently linked to hypertension, a key component of the metabolic syndrome, but only with hypertension coexisting with diabetes.

Some studies have shown an “inverse” association between several components of the metabolic syndrome and dementia or cognitive decline. For example, studies have reported (a) a higher risk of dementia with low blood pressure (rather than high blood pressure) among adults aged 75 plus years (19), (b) a reduced risk of dementia with higher total cholesterol among adults aged 70 plus years (17,45), (c) a reduced risk for dementia with higher BMI among adults with mean age of 71.8 years (16), and a reduced risk of dementia for abdominal obesity among adults aged 75 plus years (15). The latter study also reported that adults aged 75 plus with the metabolic syndrome may be at lower risk for AD in addition to overall dementia (15).

An important question is why the association of metabolic syndrome and cognitive decline is attenuated at older ages. Regarding one component of the metabolic syndrome that changes direction with age, hypertension, one of the possible mechanisms for the null (or reverse) association between hypertension and cognitive performance among the oldest old may include changes in cerebral blood flow tied with cognitive performance (46). Cerebral blood flow decreases with advancing age (47–49), and demented older adults have lower cerebral blood flow than those with optimal cognitive function (49). Although reduced cerebral blood flow is a normal aging process and brain atrophy begins in relatively early adulthood (50,51), exaggerated reduction in cerebral blood flow may accelerate the atrophy. Hypertension effects on brain function, possibly accounting for reduced regional cerebral blood flow, have been shown to be cumulative, and the association between hypertension and regional cerebral blood flow has been further strengthened by duration of hypertension (52). On the other hand, in the oldest old, higher blood pressure may be required to maintain adequate cerebral blood pressure and to preserve cognitive functions (49,53).

Regarding another component of the metabolic syndrome that changes direction with age, cholesterol, experimental studies suggest that high cholesterol accelerates production of beta-amyloid (54,55), which is the putative causative agent for AD. However, cholesterol is required for the formation of synapses (56), and synaptic loss correlates with cognitive impairment in AD (57). Cholesterol is also essential to maintain the myelin sheath, which surrounds and insulates the nerve cells, is rich in cholesterol, and is used to build synapses. The myelin function declines with age after middle age, and AD is associated with more severe myelin breakdown (58). Therefore, low cholesterol levels may make the myelin more vulnerable to malfunction as age progresses to the upper limits.

On the other hand, one consistent component of the metabolic syndrome across ages is the link of hyperinsulinemia and diabetes to an increased risk of dementia in late life. This relation appears to be consistent regardless of the ages at which the measurements were taken in middle or old age. One explanation is that insulin can act directly on the brain. Peripheral insulin crosses the blood–brain barrier via a receptor-mediated active transport process (59), and insulin receptors have been found in the hippocampus (60), a brain area that is crucial to memory function and is damaged by AD. Moreover, high insulin levels in the brain may interfere with the metabolism of amyloid beta by insulin-degrading enzyme, which regulates the metabolism of insulin and the deposition of beta amyloid (61). Consistent with the deleterious effect of hyperinsulinemia and diabetes on brain function, we found that elevated HbA1c is associated with cognitive decline over a 3-year period, even in the oldest old. HbA1c is one common measure of glycosylated hemoglobin, which measures average blood glucose levels over the preceding 1–3 months and, as such, is a better marker of long-term glucose levels than a one-time fasting glucose measurement. Our finding lends support to previous work linking glucose to cognitive decline (62) and suggests a more focused effort on biological mechanisms linked to blood sugar and insulin, such as the insulin signaling pathway. This pathway influences multiple phenotypes associated with healthy aging (63), including cognitive health (64).

There are other potential explanations for our findings. One such explanation might be selection bias. The participants might represent a group of healthy survivors who are less susceptible to the adverse effects of the metabolic syndrome. Another possible explanation is reverse causation. The reduced risk of having metabolic syndrome may be a consequence rather than a cause of dementia or cognitive impairment. For example, BMI, total cholesterol, and blood pressure are shown to decrease several years preceding the onset of dementia (65,66). Weight loss may result from eating difficulty (67) or impaired olfaction (68) due to cognitive impairment, and/or sarcopenia and low blood pressure preceding onset of dementia may be secondary to the underlying dementia pathology (13,45,65). Finally, recent studies have led to the hypothesis that metabolic syndrome in the oldest old might even be an adaptive mechanism to protect against deleterious effects of aging (20).

This study has several limitations. First, our cohort consisted of older people who were relatively healthy at baseline and was limited to Japanese participants from Okinawa. Therefore, caution should be used when generalizing to other populations. Second, we may have an insufficient sample size and follow-up period to detect a meaningful association between the metabolic syndrome and cognitive decline, although the participants are aged 80 years or older (averaging 85 years and ranging up to 98 years) and are at higher risk of developing cognitive impairment or dementia. Using the estimated coefficients, standard errors, and the current sample size, we performed power analyses for the interaction terms between the metabolic syndrome or its components and time, which indicate the additional change in cognitive test scores from the baseline examination among the participants with the metabolic syndrome or its components. For all interactions, the power was below 30% except for the interaction between HbA1c and time 2 (power = 75.9%). However, despite the small sample size and short duration of follow-up, we still found a significant association between high HbA1c (defined as ≥ 5.4%) and decline in memory function after 2 years. Third, there is a lack of information on how long the participants had the metabolic syndrome before the study. Finally, we substituted BMI for waist circumference and glycosylated hemoglobin level for fasting glucose level, which may influence the overall results, even though these substitutions have been validated in other studies (27,69,70).

In conclusion, our results showed that during the 3 years of follow-up, those with or without metabolic syndrome or its components did not differ with regards to change in cognitive test scores, with the exception of HbA1c and memory decline. The bulk of evidence accumulated thus far in the oldest old suggests attenuated, null, or possibly even reversal risk of the metabolic syndrome and some of its components on cognitive function. Our study supports these past findings and also lends weight to the relevance of glucose, even in the oldest old, as a persistent risk factor for incident cognitive decline in the Okinawan population. A longer study with larger sample size is required to confirm our findings and to assess the utility of the metabolic syndrome (and its components) as a predictor for cognitive decline in the oldest old. Clinical trials will ultimately be needed to assess the efficacy of treating metabolic syndrome and its individual components as more and more individuals join the ranks of the oldest old (71).

FUNDING

This study was supported by the National Institute on Aging (K01AG023014, R01AG033581, P30AG008017; Dodge and R01 AG027060-01; Willcox), Linus Pauling Institute Research Grant (Dodge), and Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) (20790442; Katsumata).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All the authors have no conflicts of interest as regards this study.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere appreciation to Ms. Takiko Hokama, Ms. Satsuki Ishikawa, Ms. Masayo Iha, and Mr. Daisuke Higa, who acted as study coordinators for the KOCOA project. Faculty and staff from the University of the Ryukyus Hospital were also instrumental in the successful completion of the project. Finally, this study would not have been possible without the cooperation and support of the municipalities, public officials, families, and most importantly, the participants in our studies.

Author contributions: Y.K.: content, concept, and design; obtaining funding; acquisition of participants and data; analysis and interpretation of data; and drafting of the manuscript. H.T.: content, concept, and design; acquisition of participants and data; and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Y.H.: acquisition of data and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. S.Y.: content, concept, and design and acquisition of participants and data. D.C.W.: content, concept, and design; acquisition of participants and data; and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Y.O.: content, concept, and design and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. B.J.W.: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. H.H.D.: content, concept, and design; obtaining funding; interpretation of data; and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Sponsor’s role: None.

APPENDIX I.

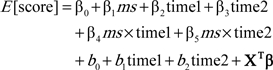

The separate mixed-effects model for the metabolic syndrome and each component controlling for age, gender, and educational levels is described below:

|

β0 is the population average intercept.

ms is the dummy variable for the metabolic syndrome or its components status (coded ms = 1 for the presence and coded ms = 0 for the absence); β1 indicates the cross-sectional population effect on cognitive test score at baseline.

time1 and time2 are the dummy variables for time (coded time1 = 0 and time2 = 0 for the baseline and time1 = 1 and time2 = 0 for the first follow-up and time1 = 0 and time2 = 1 for the second follow-up); β2 and β3 are their associated fixed-effect coefficients and indicate 1-year and 2-year population change in cognitive test scores from the baseline examination among the participants WITHOUT the metabolic syndrome or its components, respectively.

β4 and β5 are the fixed-effect coefficients for interactions between the metabolic syndrome or its components status and time and indicate the additional 1-year and 2-year population change in cognitive test scores from the baseline examination among the participants WITH the metabolic syndrome or its components, respectively.

b0 is the individual random intercept and b1 and b2 indicates 1-year and 2-year random change in cognitive test score from baseline examination, respectively.

X is the vector of covariates to control age, gender, and years of education, and β is the vector representing their fixed-effect coefficients.

References

- 1.Brookmeyer R, Gray S. Methods for projecting the incidence and prevalence of chronic diseases in aging populations: application to Alzheimer's disease. Stat Med. 2000;19:1481–1493. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(20000615/30)19:11/12<1481::aid-sim440>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fujishima M, Kiyohara Y. Incidence and risk factors of dementia in a defined elderly Japanese population: the Hisayama study. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;977:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kivipelto M, Helkala EL, Laakso MP, et al. Midlife vascular risk factors and Alzheimer's disease in later life: longitudinal, population based study. BMJ. 2001;322:1447–1451. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7300.1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knopman D, Boland LL, Mosley T, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors and cognitive decline in middle-aged adults. Neurology. 2001;56:42–48. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Launer LJ, Masaki K, Petrovitch H, Foley D, Havlik RJ. The association between midlife blood pressure levels and late-life cognitive function. The Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. JAMA. 1995;274:1846–1851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vanhanen M, Koivisto K, Moilanen L, et al. Association of metabolic syndrome with Alzheimer disease: a population-based study. Neurology. 2006;67:843–847. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000234037.91185.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whitmer RA, Gunderson EP, Barrett-Connor E, Quesenberry CP, Jr, Yaffe K. Obesity in middle age and future risk of dementia: a 27 year longitudinal population based study. BMJ. 2005;330:1360. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38446.466238.E0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whitmer RA, Sidney S, Selby J, Johnston SC, Yaffe K. Midlife cardiovascular risk factors and risk of dementia in late life. Neurology. 2005;64:277–281. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000149519.47454.F2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yaffe K, Barrett-Connor E, Lin F, Grady D. Serum lipoprotein levels, statin use, and cognitive function in older women. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:378–384. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.3.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yaffe K, Kanaya A, Lindquist K, et al. The metabolic syndrome, inflammation, and risk of cognitive decline. JAMA. 2004;292:2237–2242. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.18.2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yaffe K, Weston AL, Blackwell T, Krueger KA. The metabolic syndrome and development of cognitive impairment among older women. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:324–328. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2008.566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morley JE. The metabolic syndrome and aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59:139–142. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.2.m139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muller M, Tang MX, Schupf N, Manly JJ, Mayeux R, Luchsinger JA. Metabolic syndrome and dementia risk in a multiethnic elderly cohort. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;24:185–192. doi: 10.1159/000105927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van den Berg E, Biessels GJ, de Craen AJ, Gussekloo J, Westendorp RG. The metabolic syndrome is associated with decelerated cognitive decline in the oldest old. Neurology. 2007;69:979–985. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000271381.30143.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forti P, Pisacane N, Rietti E, et al. Metabolic syndrome and risk of dementia in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:487–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hughes TF, Borenstein AR, Schofield E, Wu Y, Larson EB. Association between late-life body mass index and dementia: the Kame Project. Neurology. 2009;72:1741–1746. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a60a58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Piguet O, Grayson DA, Creasey H, et al. Vascular risk factors, cognition and dementia incidence over 6 years in the Sydney Older Persons Study. Neuroepidemiology. 2003;22:165–171. doi: 10.1159/000069886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hestad K, Kveberg B, Engedal K. Low blood pressure is a better predictor of cognitive deficits than the apolipoprotein e4 allele in the oldest old. Acta Neurol Scand. 2005;111:323–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2005.00397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verghese J, Lipton RB, Hall CB, Kuslansky G, Katz MJ. Low blood pressure and the risk of dementia in very old individuals. Neurology. 2003;61:1667–1672. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000098934.18300.be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Le Couteur DG, Simpson SJ. Adaptive senectitude: the prolongevity effects of aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66:179–182. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sekita A, Ninomiya T, Tanizaki Y, et al. Trends in prevalence of Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia in a Japanese community: the Hisayama Study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;122:319–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Willcox DC, Willcox BJ, He Q, Wang NC, Suzuki M. They really are that old: a validation study of centenarian prevalence in Okinawa. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63:338–349. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.4.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Todoriki H, Willcox D, Willcox B. The effects of post-war dietary change on longevity and health in Okinawa. Okinawan J Am Studies. 2004;1:52–61. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dodge HH, Katsumata Y, Todoriki H, et al. Comparisons of plasma/serum micronutrients between Okinawan and Oregonian elders: a pilot study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65:1060–1067. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.The Examination Committee of Criteria for `Obesity Disease’ in Japan/Japan Society for the Study of Obesity. New criteria for ‘obesity disease’ in Japan. Circ J. 2002;66:987–992. doi: 10.1253/circj.66.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sung KC, Rhee EJ. Glycated haemoglobin as a predictor for metabolic syndrome in non-diabetic Korean adults. Diabet Med. 2007;24:848–854. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02146.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nathan DM, Kuenen J, Borg R, Zheng H, Schoenfeld D, Heine RJ. Translating the A1C assay into estimated average glucose values. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1473–1478. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dodge HH, Meguro K, Ishii H, Yamaguchi S, Saxton JA, Ganguli M. Cross-cultural comparisons of the Mini-mental State Examination between Japanese and U.S. cohorts. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21:113–122. doi: 10.1017/S1041610208007886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takechi H, Dodge HH. Scenery Picture Memory Test: a new type of quick and effective screening test to detect early stage Alzheimer's disease patients. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2010;10:183–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2009.00576.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lezak MD. Neuropsychological Assessment. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Littell RC, Milliken GA, Stroup WW, et al. SAS for Mixed Models. 2nd ed. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feart C, Samieri C, Rondeau V, et al. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet, cognitive decline, and risk of dementia. JAMA. 2009;302:638–648. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jacqmin-Gadda H, Fabrigoule C, Commenges D, Dartigues JF. A 5-year longitudinal study of the Mini-Mental State Examination in normal aging. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145:498–506. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Penninx BW, Nicklas BJ, Newman AB, et al. Metabolic syndrome and physical decline in older persons: results from the Health, Aging And Body Composition Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:96–102. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gln005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rasgon N, Jarvik L. Insulin resistance, affective disorders, and Alzheimer's disease: review and hypothesis. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59:178–183. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.2.m178. discussion 184–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Willcox BJ, Willcox DC, Ferrucci L. Secrets of healthy aging and longevity from exceptional survivors around the globe: lessons from octogenarians to supercentenarians. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63:1181–1185. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.11.1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamada M, Kasagi F, Sasaki H, Masunari N, Mimori Y, Suzuki G. Association between dementia and midlife risk factors: the Radiation Effects Research Foundation Adult Health Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:410–414. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kivipelto M, Helkala EL, Hanninen T, et al. Midlife vascular risk factors and late-life mild cognitive impairment: a population-based study. Neurology. 2001;56:1683–1689. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.12.1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schnaider Beeri M, Goldbourt U, Silverman JM, et al. Diabetes mellitus in midlife and the risk of dementia three decades later. Neurology. 2004;63:1902–1907. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000144278.79488.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hassing LB, Hofer SM, Nilsson SE, et al. Comorbid type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension exacerbates cognitive decline: evidence from a longitudinal study. Age Ageing. 2004;33:355–361. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afh100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luchsinger JA, Reitz C, Honig LS, Tang MX, Shea S, Mayeux R. Aggregation of vascular risk factors and risk of incident Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2005;65:545–551. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000172914.08967.dc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mielke MM, Zandi PP, Sjogren M, et al. High total cholesterol levels in late life associated with a reduced risk of dementia. Neurology. 2005;64:1689–1695. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000161870.78572.A5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meyer JS, Rogers RL, Judd BW, Mortel KF, Sims P. Cognition and cerebral blood flow fluctuate together in multi-infarct dementia. Stroke. 1988;19:163–169. doi: 10.1161/01.str.19.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dandona P, James IM, Newbury PA, Woollard ML, Beckett AG. Cerebral blood flow in diabetes mellitus: evidence of abnormal cerebrovascular reactivity. Br Med J. 1978;2:325–326. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6133.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Melamed E, Lavy S, Bentin S, Cooper G, Rinot Y. Reduction in regional cerebral blood flow during normal aging in man. Stroke. 1980;11:31–35. doi: 10.1161/01.str.11.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Spilt A, Weverling-Rijnsburger AW, Middelkoop HA, et al. Late-onset dementia: structural brain damage and total cerebral blood flow. Radiology. 2005;236:990–995. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2363041454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Launer LJ. The epidemiologic study of dementia: a life-long quest? Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26:335–340. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Salthouse TA. When does age-related cognitive decline begin? Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30:507–514. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beason-Held LL, Moghekar A, Zonderman AB, Kraut MA, Resnick SM. Longitudinal changes in cerebral blood flow in the older hypertensive brain. Stroke. 2007;38:1766–1773. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.477109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ruitenberg A, den Heijer T, Bakker SL, et al. Cerebral hypoperfusion and clinical onset of dementia: the Rotterdam Study. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:789–794. doi: 10.1002/ana.20493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fassbender K, Simons M, Bergmann C, et al. Simvastatin strongly reduces levels of Alzheimer's disease beta-amyloid peptides Abeta 42 and Abeta 40 in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:5856–5861. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081620098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Simons M, Keller P, De Strooper B, Beyreuther K, Dotti CG, Simons K. Cholesterol depletion inhibits the generation of beta-amyloid in hippocampal neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:6460–6464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mauch DH, Nagler K, Schumacher S, et al. CNS synaptogenesis promoted by glia-derived cholesterol. Science. 2001;294:1354–1357. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5545.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer's disease is a synaptic failure. Science. 2002;298:789–791. doi: 10.1126/science.1074069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bartzokis G, Cummings JL, Sultzer D, Henderson VW, Nuechterlein KH, Mintz J. White matter structural integrity in healthy aging adults and patients with Alzheimer disease: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:393–398. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.3.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Banks WA. The source of cerebral insulin. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;490:5–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Park CR. Cognitive effects of insulin in the central nervous system. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2001;25:311–323. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(01)00016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Farris W, Mansourian S, Chang Y, et al. Insulin-degrading enzyme regulates the levels of insulin, amyloid beta-protein, and the beta-amyloid precursor protein intracellular domain in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:4162–4167. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0230450100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dahle CL, Jacobs BS, Raz N. Aging, vascular risk, and cognition: blood glucose, pulse pressure, and cognitive performance in healthy adults. Psychol Aging. 2009;24:154–162. doi: 10.1037/a0014283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Willcox BJ, Donlon TA, He Q, et al. FOXO3A genotype is strongly associated with human longevity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:13987–13992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801030105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liao FF, Xu H. Insulin signaling in sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Sci Signal. 2009;2:pe36. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.274pe36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Skoog I, Lernfelt B, Landahl S, et al. 15-year longitudinal study of blood pressure and dementia. Lancet. 1996;347:1141–1145. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90608-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stewart R, Masaki K, Xue QL, et al. A 32-year prospective study of change in body weight and incident dementia: the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:55–60. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chang CC, Roberts BL. Feeding difficulty in older adults with dementia. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17:2266–2274. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.02275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Djordjevic J, Jones-Gotman M, De Sousa K, Chertkow H. Olfaction in patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2008;29:693–706. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ferreira I, Henry RM, Twisk JW, van Mechelen W, Kemper HC, Stehouwer CD. The metabolic syndrome, cardiopulmonary fitness, and subcutaneous trunk fat as independent determinants of arterial stiffness: the Amsterdam Growth and Health Longitudinal Study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:875–882. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.8.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Grant T, Soriano Y, Marantz PR, et al. Community-based screening for cardiovascular disease and diabetes using HbA1c. Am J Prev Med. 2004;26:271–275. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yassine HN, Marchetti CM, Krishnan RK, Vrobel TR, Gonzalez F, Kirwan JP. Effects of exercise and caloric restriction on insulin resistance and cardiometabolic risk factors in older obese adults—a randomized clinical trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:90–95. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gln032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]