Abstract

Dendritic cells (DCs) have been successfully induced in vitro from chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) cells, which may provide a promising immunotherapeutic protocol for CML. To facilitate the optimization of DCs-based vaccination protocols, we investigated the efficiency of in vitro generation of DCs from bone marrow mononuclear cells of CML patients by clinical reagents of GM-CSF and IFN-α. Bone marrow mononuclear cells were isolated from eight CML patients and CML-DCs were generated in the presence of different cytokines (Group A: GM-CSF for research and IL-4 for research; Group B: GM-CSF for injection and IFN-α for injection) in RMPI-1640 medium containing 10% human AB serum. After 8 days, the morphologic features of CML-DCs were observed and their immunophenotypes were analyzed by flow cytometry. The activity of CML-DCs was determined by evaluating their ability to stimulate allogeneic mixed lymphocyte reaction (allo-MLR) and anti-leukemic cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs). The culture protocols were successful in generating functional CML-DCs from all the CML patients as evidenced by the significant upregulation of CD80, CD86, CD83 HLA-DR and CD1a compared to pre-cultured (p < 0.05), and increased allogeneic T cell stimulating proliferation capacity (p < 0.05). CML-DCs could stimulate a specific anti-leukemia response. In summary, we demonstrate that the combination of clinical reagents GM-CSF and IFN-α induced the generation of DCs that have the ability to stimulate a specific anti-leukemia CTLs response in vitro, indicating their feasibility for clinical vaccination protocols for CML patients.

Keywords: Chronic myeloid leukemia, Dendritic cells, Clinical reagents

Introduction

Dendritic cells are regarded as the most potent and versatile antigen-presenting cells in the immune system (Trombetta et al. 2005). They possess attributes that allow them to effectively fulfill the requirements for priming/activating T cells and mediating tumor-specific immune responses (Whiteside and Odoux 2004). In recent years, it has become increasingly clear that defects in DCs contribute to non-responsiveness of tumors (Gabrilovich 2004). Recent studies have shown that interferon-α (IFN-α) plays an important role in the induction of antitumor immunity by exerting a variety of effects on DCs (Belardelli et al. 2002; Belardelli and Ferrantini 2002). Type I interferons potently enhance humoral immunity and promote isotype switching by stimulating DCs in vivo (Le Bon et al. 2001). DCs generated in the presence of IFN-α exhibit high expression of major histocompatibility and co-stimulatory molecules as well as a potent ability to stimulate CD8+ T-cell responses (Carbonneil et al. 2004; Dauer et al. 2006; Lapenta et al. 2006).

DCs are mainly derived from hematopoietic progenitors that migrate to lymphoid organs where they mature and present processed antigen to T lymphocytes. DCs occur rarely in the blood but can be derived from peripheral blood monocytes by culturing them in interleukin-4 (IL-4) and granulocytemacrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (Kiertscher and Roth 1996). Interestingly, this culture method has been employed to prepare DCs from peripheral blood or bone marrow cells of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) patients which could present CML-specific antigens to cytotoxic T lymphocytes (Wang et al. 1999). Up to now, ex vivo generated CML DCs have been successfully applied to the immunotherapy of CML in preliminary clinical trials (Lim et al. 1998).

However, it is not known whether bone marrow mononuclear cells of CML patients cultured in the presence of clinical reagents can be driven into immune-competent CML-DCs. The purpose of the present study is to develop a protocol to induce DCs from bone marrow mononuclear cells which may be used clinically. Therefore, we selected eight CML patients in the chronic stage for our study and demonstrated that clinical reagents of GM-CSF plus IFN-α induced functional CML-DCs. These CML-DCs had similar properties to classical DCs generated with GM-CSF plus IL-4 and had the capacity to stimulate T cell proliferation and induce specific anti-leukemia response in vitro.

Materials and methods

Patient samples

CML diagnosis was performed according to standard morphologic, cytochemical, immunophenotypic and cytogenetic criteria. Eight CML patients in chronic stage without treatment by IFN-α were included in this study, including 5 women and 3 men aged 26–73 years old. All patients were positive for the Philatelphia (Ph) chromosome. All the subjects gave informed consent and the study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Soochow University.

Isolation of bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMMNCs)

Bone marrow mononuclear cells were obtained from 8 mL heparinized bone marrow of CML patients by Ficoll-hypaque (density of 1.077 g/mL) density gradient centrifugation (Gabriele et al. 2004). The mononuclear cell fraction was washed 5 times with RMPI-1640 medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad/CA, USA).

Culture of CML-DCs

DCs was generated from BMMNCs using the method previously described for the generation of CML-DCs (Wang et al. 1999). Briefly, BMMNCs were resuspended in RPMI1640 medium supplemented with 10% human AB serum and seeded in 24-well plates at 3–5 × 106 cells/well and cultured at 37 °C in 5% CO2 incubator for 2 h. Then the non-adherent cells were decanted and the adherent cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with either GM-CSF (800 U/mL; PeproTech, London, UK) plus IL-4 (500 U/mL; PeproTech, London, UK) (Group A: represented by GM-CSF/IL-4) or GM-CSF (600 ng/mL; North China Pharmaceutical Group, Shijiazhuang, China) plus IFN-α (200 U/mL; Livzon Group, Suzhou Xinbao Pharmaceutical Factory, China) (Group B: represented by GM-CSF/IFN-α). The medium was exchanged every 3 days with fresh cytokine-supplemented medium. After 8 days in culture, the DCs were harvested for subsequent experiments.

Immunophenotypic analysis

Freshly isolated and cultured cells of each group were washed and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated with a series of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) (10 μL per mAbs), conjugated with either fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) or phycoerythrin (PE) for 30 min at 4 °C. The following mAbs were used: anti CD80, CD86, HLA-DR, CD83, and CD1a (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). The samples were washed twice in PBS, and then resuspended with 0.2 mL PBS. The samples were analyzed using a FACScabilur flow cytometer and CellQuest software (Becton–Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA). Cells were electronically gated according to light scatter properties to exclude cell debris and contaminating lymphocytes. At least 1 × 104 cells of each sample were analyzed.

Concentration of IL-12 in culture supernatants of DCs

The supernatants of DCs were harvested through a period of 5 and 8 days of culture for measurement of IL-12p40 and IL-12p70 concentration by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Biosource International, Camarillo, CA, USA). Samples of each group were set to triple wells and analyzed following the instructions of the ELISA kit.

Allogeneic mixed lymphocyte reaction (Allo-MLR)

The non-adherent peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy volunteers were used as responder cells (R). Responder cells were counted and seeded into 96-well round-bottomed microplates at 2 × 105 cells/well. DCs in both groups were pretreated with 25 μg/mL mitomycin for 30 min to prevent proliferation, washed 3 times with RPMI1640 medium and then used as stimulator cells (S). Pretreated DCs were added to the responder cells at varying ratios (R:S: 1:10, 1:20 or 1:50) in triplicate wells. The final volume of each well was adjusted to 200 μL. Triplicate wells of T cells and RPMI1640 medium alone were used as the responder cells control and blank control, respectively. After 96 h in culture, 15 μL MTT was added to each well and incubated for an additional 4–6 h. The absorbance value of each well was measured using BIO-RAD Model 550 microplate reader (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) at 570 nm. Stimulation index (SI) was calculated according to the formula: SI = (AE − AB)/(AC − AB) (AE: the mean absorbance value of the triplicate experiment wells, AC: the mean absorbance value of the responder control wells, AB: the mean absorbance value of the blank control.)

Generation of leukemia-specific CTLs and cytotoxicity assay

Leukemia-specific CTLs were activated from the non-adherent PBMNCs of HLA-matched healthy volunteers. The non-adherent PBMNCs of 2.5 × 106/well of a 24-well plate were co-cultured with DCs (generated as described above) of 2.5 × 105/well for 5 days. The final volume of each well was adjusted to 1.25 mL RPMI1640 medium supplemented with 10% human AB serum and 100 U/mL IL-2. After 5 days of co-culture, cytotoxicity assay was performed in vitro using MTT assay. Target cells were co-cultured with T cells using effector:target ratios of 25:1 for 48 h in 96-well plates. Target cells included auto-BMMNCs, K562 cell strain and healthy donor PBMNCs. The effector cells, target cells and RPMI1640 alone were used as control, respectively. Results were expressed as a percentage of specific lysis according to the following formula: (AT + AE-AEx-AR)/(AT-AR) (AEx: the mean absorbance value of the experiment wells, AE: the mean absorbance value of effectors, AT: the mean absorbance value of targets, AR: the mean absorbance value of RMPI1640.)

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS version 13.0 Software for Windows. The data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and analyzed by Student-t tests or one-way ANOVA.

Results

Morphology of CML-DCs

With both cytokine cocktails, the adherent cells consistently displayed different levels of increase in the cell size and changed into non-adherent dispersed cells or in clusters with cytoplasmic protrusions. After 8 days, non-adherent cells with large cell bodies and long dendritic cytoplasmic protrusions were the predominant population. Wright–Giemsa staining showed the typical DC morphology displaying large cell bodies, bi-nucleus and distinct dendritic cytoplasmic protrusions in both Group A and B (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Morphology of BMMNCs cultured at different time durations of the entire culture period. a BMMNCs before the culture. b CML-DCs cultured in the presence of GM-CSF/IL-4 for 8 days. c CML-DCs cultured in the presence of GM-CSF/IFN-α for 8 days. d Wright–Giemsa staining of CML-DCs cultured in the presence of GM-CSF/IL-4 for 8 days. e Wright–Giemsa staining of CML-DCs cultured in the presence of GM-CSF/IFN-α for 8 days. a–c Amplification ×200. d, e amplification ×1,000

Immunophenotype analysis of DCs

We performed immunophenotype analysis of adherent bone marrow mononuclear cells cultured in the presence of the different cytokines at the different time points. After 5 or 8 days, the immunophenotypes in both groups showed significant up-regulation of CD80, CD86, CD83 HLA-DR and CD1a compared to those in the pre-culture (p < 0.01). On day 5, there was significantly higher expression of CD83 in the Group B (p < 0.05). But on day 8, there was not significant distinction in the immunophenotypes between both groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparasion of immunophenotypes of DCs derived from CML treated with GM-CSF/IL-4 and GM-CSF/IFN-α

| Culture time | Percentage of cells positive for the specific markers | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD80 | CD86 | HLA-DR | CD83 | CD1a | ||

| A | Pre-culture | 1.96 ± 0.59 | 1.76 ± 0.84 | 14.65 ± 3.51 | 0.52 ± 0.33 | 1.47 ± 2.21 |

| Culture 5 days | 10.71 ± 2.78 | 21.71 ± 4.39 | 44.26 ± 8.16 | 7.28 ± 2.95 | 16.06 ± 5.70 | |

| Culture 7–9 days | 37.21 ± 18.83 | 41.56 ± 14.05 | 80.33 ± 20.58 | 17.18 ± 7.40 | 44.36 ± 23.05 | |

| B | Pre-culture | 1.96 ± 0.59 | 1.76 ± 0.84 | 14.65 ± 3.51 | 0.52 ± 0.33 | 1.47 ± 2.21 |

| Culture 5 days | 12.86 ± 4.68 | 21.99 ± 6.44 | 43.99 ± 7.03 | 10.51 ± 4.65* | 14.81 ± 3.35 | |

| Culture 7–9 days | 24.89 ± 12.91 | 31.24 ± 8.95 | 76.44 ± 20.13 | 16.49 ± 6.59 | 21.82 ± 11.51 | |

Group A: GM-CSF/IL-4 treatment; Group B: GM-CSF/IFN-α treatment. Data were expressed as mean ± SD (n = 8)

* μ p < 0.05 percentage of cells positive for CD83 for DCs in Group B versus Group A after 5 days of culture

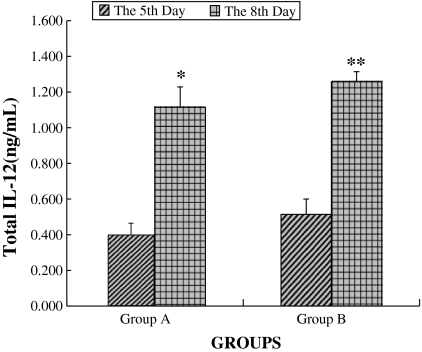

Concentration of IL-12 in culture supernatants of DCs

Production of immuoregulatory cytokines by DCs is a critical factor for T cell activation (Dauer et al. 2003). Therefore, we detected the secretion of IL-12 by CML-DCs. As shown in Fig. 2, the concentration of IL-12 in culture supernatants of DCs at the same time-point for GM-CSF/IFN-α and GM-CSF/IL-4 was not significantly different (p > 0.05). But the concentration of total IL-12 on the 8th day was significantly higher than that on the 5th day (p < 0.05). These results indicate that CML-DCs may activate CTL responses by promoting the secretion of IL-12.

Fig. 2.

Concentration of IL-12 in culture supernatants of CML-DCs from Group A and Group B. The concentration of IL-12 was detected by ELISA and is presented as mean ± SD (n = 8). *p < 0.05 versus the 5th day in Group A, **p < 0.05 versus the 5th day in Group B. Group A: CML-DCs cultured in the presence of GM-CSF/IL-4; Group B: CML-DCs cultured in the presence of GM-CSF/IFN-α

Functional properties of CML-DCs

The immunostimulatory capacity of the CML-DCs generated by both cytokine cocktails was assessed by allogeneic MLR assays. The results showed that CML-DCs showed a consistent increase of the allo-immunostimulatory capacity with the increase of stimulator-to-responder ratios (Fig. 3). Furthermore, the DCs generated with GM-CSF/IFN-α showed significantly stronger immunostimulatory capacity to T cells than DCs generated with GM-CSF/IL-4 at a R:S ratio of 1:10 (p < 0.05, Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Stimulation of T cell proliferation by CML-DCs from Group A and Group B. The data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 8). *p < 0.05, versus Group A. Group A: CML-DCs cultured in the presence of GM-CSF/IL-4; Group B: CML-DCs cultured in the presence of GM-CSF/IFN-α

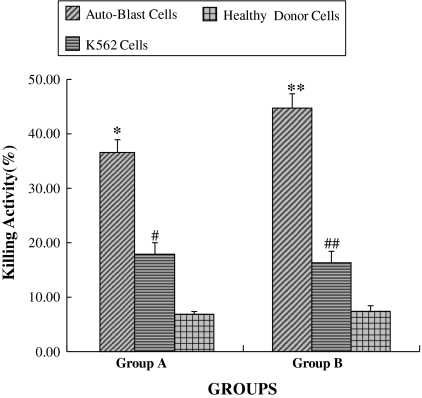

Cytotoxicity of leukemia-specific CTLs

Leukemia-specific CTLs generated by CML-DCs from culture containing GM-CSF/IFN-α or GM-CSF/IL-4 specifically and equally recognized auto-leukemia cells in six from eight CML patients and showed minimal reactivity against healthy donor PBMNCs at an effector:target ratio of 25:1 (Fig. 4). In addition, they also partly recognized K562 cell strain at the same effector:target ratio (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Leukemia-specific and anti-leukemia characteristics of CTLs generated by CML-DCs from Group A and Group B. The effector:target ratio was set to 25/1. The data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 8). *p < 0.05 versus K562 cells, #p < 0.05 versus healthy donor cells in Group A. **p < 0.05 versus K562 cells, ##p < 0.05, versus healthy donor cells in Group B. Group A: CML-DCs cultured in the presence of GM-CSF/IL-4; Group B: CML-DCs cultured in the presence of GM-CSF/IFN-α

Discussion

In the present study, we showed that non-adherent BMMNCs from eight CML patients, when cultured in GM-CSF/IFN-α containing medium, could be differentiated into DCs, as demonstrated by cell morphology, immunophenotypic profile and functional activity. The morphologic characteristics of CML-DCs generated by GM-CSF/IFN-α were similar to those generated by GM-CSF/IL-4.

DCs are responsible for the initiation of immune responses (Banchereau and Palucka 2005). However, the generation of effective DC subsets in vivo may be affected by leukemogenesis and may contribute to leukemia escape from immune control (Mohty et al. 2001). In this study, we compared the allogeneic immunostimulatory capacity of both groups of DCs generated in vitro and found that DCs generated with GM-CSF/IFN-α stimulated T cells significantly better than DCs generated with GM-CSF/IL-4 at a R:S ratio of 1:10, suggesting that GM-CSF/IFN-α DCs are more effective than GM-CSF/IL-4 DCs.

Furthermore, we demonstrate that leukemia-specific CTLs could be generated via either GM-CSF/IFN-α DCs or GM-CSF/IL-4 DCs. CTLs recognized auto-BMMNCs but not healthy donor PBMNCs, which proved that CTLs generated by CML-DCs display leukemia-specific and anti-leukemia characteristics. Interesting, we found that the generated CTLs also partially recognized the K562 cell strain. Korthals et al. reported that DCs generated by IFN-α acquired both mature dendritic and natural killer cell properties (Korthals et al. 2007). Given that natural killer cells have a cytolytic activity against K562 cells, we speculate that this may explain the partial lytic activity against the K562 cell strain we observed.

The BMMNCs of CML cultured in the presence of IFN-α/GM-SCF/IL-4 have been shown to be induced into DCs with morphologic and immunophenotypic characteristics of mature DCs and enhanced MLR (Wang et al. 1999; Wu et al. 2005). However, all of these inducers were used only for research purpose but not for clinical injection. In the present study, we successfully used clinical grade reagents which induced BMMNCs from CML patients into DCs with characteristic morphology, immnostimulation and specific anti-leukemia function. These data suggest that GM-CSF/IFN-α DCs may be suitable for a protocol of clinical vaccination trials for CML patients. In fact, an earlier study has demonstrated that GM-CSF improved the response obtained with IFN-α therapy in CML patients (Cortes et al. 1998). Our present results indicate that the synergistic effects of GM-CSF and IFN-α against CML in the clinic may be partially due to the stimulation of mature DCs by these two reagents.

In summary, our data show conclusively that the combination of GM-CSF/IFN-α induced the generation of fully functional DCs that closely resemble classical DCs and have the ability to stimulate a specific anti-leukemia CTLs response in vitro. However, further studies are needed to characterize the malignancy potential of these generated DCs and their in vivo activity in order to pave the way for their clinical application as effective vaccines for CML treatment.

References

- Banchereau J, Palucka AK. Dendritic cells as therapeutic vaccines against cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:296–306. doi: 10.1038/nri1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belardelli F, Ferrantini M. Cytokines as a link between innate and adaptive antitumor immunity. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:201–208. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4906(02)02195-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belardelli F, Ferrantini M, Proietti E, Kirkwood JM. Interferon-alpha in tumor immunity and immunotherapy. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2002;13:119–134. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6101(01)00022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbonneil C, Saidi H, Donkova-Petrini V, Weiss L. Dendritic cells generated in the presence of interferon-alpha stimulate allogeneic CD4 + T-cell proliferation: modulation by autocrine IL-10, enhanced T-cell apoptosis and T regulatory type 1 cells. Int Immunol. 2004;16:1037–1052. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes J, Kantarjian H, O’Brien S, Kurzroch R, Keating M, Talpaz M. GM-CSF can improve the cytogenetic response obtained with interferon-alpha therapy in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia. Leukemia. 1998;12:860–864. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauer M, Obermaier B, Herten J, Haerle C, Pohl K, Rothenfusser S, Schnurr M, Endres S, Eigler A. Mature dendritic cells derived from human monocytes within 48 hours: a novel strategy for dendritic cell differentiation from blood precursors. J Immunol. 2003;170:4069–4076. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.8.4069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauer M, Schad K, Junkmann J, Bauer C, Herten J, Kiefl R, Schnurr M, Endres S, Eigler A. IFN-alpha promotes definitive maturation of dendritic cells generated by short-term culture of monocytes with GM-CSF and IL-4. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80:278–286. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1005592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriele L, Borghi P, Rozera C, Sestili P, Andreotti M, Guarini A, Montefusco E, Foà R, Belardelli F. IFN-alpha promotes the rapid differentiation of monocytes from patients with chronic myeloid leukemia into activated dendritic cells tuned to undergo full maturation after LPS treatment. Blood. 2004;103:980–987. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrilovich D. Mechanisms and functional significance of tumour-induced dendritic-cell defects. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:941–952. doi: 10.1038/nri1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiertscher SM, Roth MD. Human CD14 + leukocytes acquire the phenotype and function of antigen-presenting dendritic cells when cultured in GM-CSF and IL-4. J Leukoc Biol. 1996;59:208–218. doi: 10.1002/jlb.59.2.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korthals M, Safaian N, Kronenwett R, Maihöfer D, Schott M, Papewalis C, Diaz Blanco E, Winter M, Czibere A, Haas R, Kobbe G, Fenk R. Monocyte derived dendritic cells generated by IFN-alpha acquire mature dendritic and natural killer cell properties as shown by gene expression analysis. J Transl Med. 2007;5:46. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-5-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapenta C, Santini SM, Spada M, Donati S, Urbani F, Accapezzato D, Franceschini D, Andreotti M, Barnaba V, Belardelli F. IFN-alpha-conditioned dendritic cells are highly efficient in inducing cross-priming CD8(+) T cells against exogenous viral antigens. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:2046–2060. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bon A, Schiavoni G, D’Agostino G, Gresser I, Belardelli F, Tough DF. Type i interferons potently enhance humoral immunity and can promote isotype switching by stimulating dendritic cells in vivo. Immunity. 2001;14:461–470. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(01)00126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim SH, Coleman S, Bailey-Wood R. In vitro cytokine-primed leukaemia cells induce in vivo T cell responsiveness in chronic myeloid leukaemia. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1998;22:1185–1190. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohty M, Jarrossay D, Lafage-Pochitaloff M, Zandotti C, Brière F, Lamballeri XN, Isnardon D, Sainty D, Olive D, Gaugler B. Circulating blood dendritic cells from myeloid leukemia patients display quantitative and cytogenetic abnormalities as well as functional impairment. Blood. 2001;98:3750–3756. doi: 10.1182/blood.V98.13.3750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trombetta ES, Mellman I. Cell biology of antigen processing in vitro and in vivo. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:975–1028. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Al-Omar HM, Radvanyi L, Banerjee A, Bouman D, Squire J, Messner HA. Clonal heterogeneity of dendritic cells derived from patients with chronic myeloid leukemia and enhancement of their T-cells stimulatory activity by IFN-alpha. Exp Hematol. 1999;27:1176–1184. doi: 10.1016/S0301-472X(99)00055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside TL, Odoux C. Dendritic cell biology and cancer therapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2004;53:240–248. doi: 10.1007/s00262-003-0468-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CY, Zhang LS, Zhang YF, Chai Y, Yi LC, Song FX. In vitro inducing differentiation of bone marrow mononuclear cells of chronic myeloid leukemia. Ai Zheng. 2005;24:425–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]