Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate Fishbein’s Integrative Model in predicting young adults’ skin protection, sun exposure, and indoor tanning intentions.

Methods

212 participants completed an online survey.

Results

Damage distress, self-efficacy, and perceived control accounted for 34% of the variance in skin protection intentions. Outcome beliefs and low self-efficacy for sun avoidance accounted for 25% of the variance in sun exposure intentions. Perceived damage, outcome evaluation, norms, and indoor tanning prototype accounted for 32% of the variance in indoor tanning intentions.

Conclusions

Future research should investigate whether these variables predict exposure and protection behaviors and whether intervening can reduce young adults’ skin cancer risk behaviors.

Keywords: skin cancer prevention, Integrative Model, young adults

Introduction

Skin cancer is the most common form of cancer in the United States. The incidence of this disease is rising faster than the incidence of any other type of cancer.1 In the past 75 years, the lifetime risk for an American to develop melanoma, the most deadly form of skin cancer, has increased approximately 2000%.1 While most skin cancers are not fatal, they are common, costly, and can result in devastating effects on health and appearance.

Ultraviolet (UV) radiation is a key causal factor in the development of non-melanoma skin cancer in both humans and animal models.1 It is generally accepted that exposure to UV remains the single most significant modifiable risk factor in the prevention of melanoma.1 Recommended protective practices to prevent skin cancer include sunscreen use, protective apparel, and limiting UV exposure, whether natural or artificial.

Young adults are at risk for skin cancer, due in part to their own risky behaviors. Skin cancer rates have doubled among young women in the last 30 years.2 In fact, melanoma is now the second most common cancer among women in their twenties.1 Recent studies and literature reviews have found that knowledge about UV radiation, skin cancer, and protection is high among the general population and has increased greatly in the past 2 decades. Unfortunately, despite such awareness, American adolescents and young adults have the lowest skin protection rates of all age groups, receive large amounts of intentional and unintentional exposure to UV either from the sun or indoor tanning,3–5 and increase their exposure to both natural and artificial UV radiation as they progress into adulthood.6

Engagement in these behaviors despite awareness of their risks suggests that there are strong motivations for such exposure and/or significant barriers to engaging in protective behaviors among adolescents and young adults. Most of the literature suggests that the effect of tanning on appearance, and the association of tanned appearance with beauty and success, is the primary motivation for sunbathing and indoor tanning. A recent study by Robinson and colleagues7 indicated a significant increase (12%) over the past several decades in the number of young adults who believe a person looks better with a tan. However, appearance motivations may not account for the entirety of these risk behaviors, and while interventions focusing on appearance have been helpful in reducing these behaviors, there could be additional factors that account for the higher rates of UV exposure and lower engagement in skin protection among adolescents and young adults.

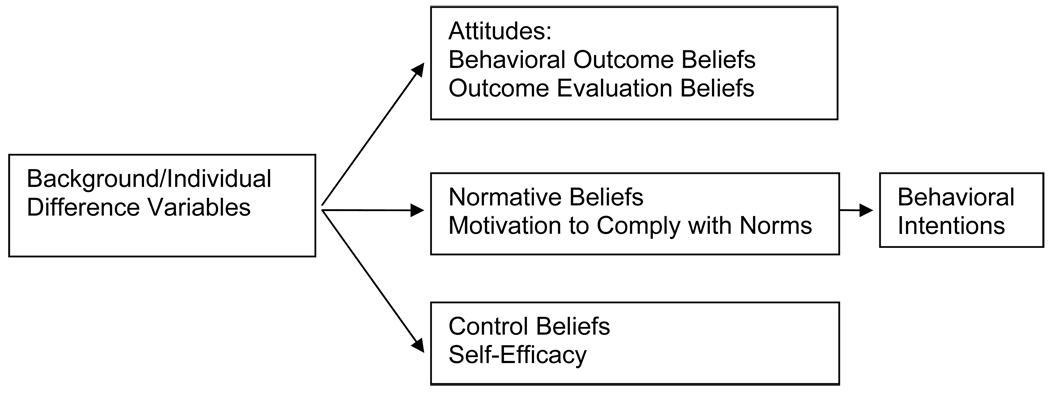

Fishbein’s Integrative Model (IM) 8 provides a comprehensive theoretical framework to describe the relationships among variables predicting young adults’ skin protection and UV exposure intentions and behavior. The IM is a compilation of several major theories and constructs (e.g., attitudes, norms, and self-efficacy) with considerable empirical support (e.g., Theory of Reasoned Action, Theory of Planned Behavior) and salience to the understanding, prediction, and modification of health behavior. Several studies provide support for the utility of the IM in explaining cancer prevention and other health intentions and behaviors as well as the development of successful behavioral health interventions. The IM includes several categories of variables. The first category includes attitudes: behavioral outcome beliefs, defined as beliefs about the consequences of performing the behavior, and outcome evaluations, defined as subjective evaluations or favorability of these consequences (e.g., decisional balance or pros versus cons of the behavior). The second category is normative beliefs in the form of quantitative norms such as how many associates engage in the behavior and subjective norms or prototypes (evaluation of the typical person who engages in the behavior) as well as motivation to comply with these norms. The third category is control beliefs and self-efficacy such as perceived control over the behavior and self-efficacy to perform the behavior (Figure 1). The model also allows for additional background/individual difference variables known to be associated with health behaviors (e.g., demographics, risk assessment). Background/individual difference variables are thought to influence behavior indirectly through their influence on attitudes, beliefs, and self-efficacy. There is evidence for the application of the IM to skin cancer risk reduction behaviors. UV exposure and protective behaviors have been found to be influenced by specific background/individual difference variables, UV-specific attitudes, normative beliefs, and self-efficacy.

Figure 1.

Adapted from Fishbein’s Integrative Model

Sun Exposure

IM variables are associated with sun exposure. Greater perceived risk for skin damage is related to lower sun exposure behavior.9 Sun exposure is associated with the behavioral outcome belief that individuals will tan with minimal burning if exposed to UV radiation and the outcome evaluation belief that being tan is attractive.10–12 Normative beliefs about the sunbathing practices of friends and family members have been shown to be positively associated with sunbathing intentions and behaviors among both adolescents and adults.13 In other words, individuals who perceive that their close friends and family members sunbathe tend to engage in this behavior as well. Studies have also shown that normative beliefs based on current standards set by high status celebrities and models of paleness or tanning in the media influence the tanning behavior of teens and adults who are motivated to comply with the norms set by high status celebrities.14 Additionally, individuals may have low control beliefs, feeling compelled to tan for appearance and/or mood management reasons. Several studies have found that some adolescents and young adults report a perceived lack of control over tanning behavior including difficulty stopping tanning and even withdrawal-like symptoms upon stopping.15–19 Self-efficacy for limiting sun exposure has not been studied previously.

Skin Protection

Greater perceived skin cancer risk has been found to be related to sun protection behavior,9, 20–22 and interventions that increase perceived skin damage and concerns about skin damage increase sun protection intentions and behavior among adolescents and young adults.23, 24 Less favorable attitudes toward a tanned appearance, behavioral outcome beliefs that skin protection will be effective, and outcome evaluation beliefs that protected skin is desirable are associated with skin protection behavior.9, 25–27 Normative beliefs about the sunscreen use of friends and family members have been shown to be positively associated with these intentions and behaviors among both adolescents and adults.13 In other words, individuals who perceive that their close friends and family members protect their skin tend to engage in these behaviors as well. Studies have also shown that normative beliefs based on current standards set by high status celebrities and models of paleness or tanning in the media influence the sun protection behavior of teens and adults who are motivated to comply with the norms set by high status celebrities.14 One of the variables found to be most strongly associated with skin cancer protection is self-efficacy.28–33 People have varying levels of self-efficacy about being able to do all the behaviors necessary to protect their skin (i.e., apply broad-spectrum high-SPF sunscreen thickly and regularly several times a day). Perceived behavioral control is also associated with skin protection.21

Indoor Tanning

Background/individual difference variables are important for indoor tanning as well. For example, perceived susceptibility to skin damage mediated the outcome effects of an intervention to reduce indoor tanning behavior among young adults.34 Attitudinal factors have also been found to contribute to indoor tanning behavior. Indoor tanning is highly associated with the attractiveness outcome evaluation belief.26, 35, 36 Research has also shown that normative beliefs influence the tanning behavior of teens and adults.14 Several studies have found that some adolescents and young adults report a perceived lack of control over tanning behavior.15–19 Self-efficacy for limiting indoor tanning has not been studied previously.

While the theories (i.e., the Theory of Reasoned Action, the Theory of Planned Behavior) and some individual IM constructs have been examined in skin cancer prevention studies, the Integrative Model has not been investigated in this context. The purpose of the current study was to determine the importance of each of the IM constructs for UV exposure and skin protection intentions among a cross section of young adults. Elucidating the factors contributing to intentions and behavior can help identify which variables to target most intensively in prevention interventions. Based on prior research, we expected that background/individual differences, attitude, normative, and self-efficacy variables would all contribute to skin protection, sun exposure, and indoor tanning intentions. However, we were interested in gaining a deeper understanding of how each of the variables might independently account for different amounts of variance among each of the specific outcomes. Most prior studies focus on one outcome and do not compare across all 3 related outcomes. First, we hypothesized that similar attitudes and beliefs would be associated with both indoor and outdoor exposure. Second, we hypothesized that similar attitudes and beliefs would be associated with skin protection and exposure but that the associations among the predictors and the outcomes would be in opposite directions. Given the severity of some skin cancers and the increasing prevalence of the disease among young adults, we believe it is important to specify variables most closely associated with each unique skin protection and UV exposure behavior in order to inform future intervention efforts.

METHODS

Recruitment, Study Procedures, and Participants

This study was approved by the appropriate institutional review boards. Participants were recruited via a university psychology student participant pool, as well as announcements, flyers, emails, and advertisements in academic departments and around campuses from 3 universities in the Philadelphia area during the 2007 and 2008 spring semesters. Spring recruitment was chosen in order to assess participants at a time of high risk for UV exposure (e.g., spring and summer breaks). Students contacted the study by email or telephone and were screened by telephone and in some cases on-line. Participants were eligible if they were of traditional college age between 18 and 24 years old, planned to be available for in-person follow ups one year later (e.g., not graduating seniors), and had at least one of several possible behavioral or family skin cancer risk factors (sunbathing, indoor tanning, low sunscreen use, or family history of skin cancer). Eligible students were provided with a website URL and password to complete an electronic consent form and a self-report survey on-line. Students then attended an in-person session in which prevention interventions were administered. Baseline online survey data were used for this study. Some students could earn extra credit for their classes for research participation. All participants received $5 for completion of the baseline survey.

A total of 512 potential participants contacted research staff initially, and 317 (62%) followed through with eligibility screening. During the screening process, 39 (12% of those screened) were provided with additional information about the study and decided they were no longer interested in participating. Thirty-one individuals (10%) screened ineligible for the study including: 19 because they would be moving out of the area during the study timeframe, 11 for being older than 24 years, and one for having no relevant risk factors. Thirty-five individuals (11%) screened eligible for the study but did not complete the baseline survey. Two hundred twelve participants (41% of those who contacted the study initially and 67% of those who followed through with screening) completed all measures included in the baseline session. See Table 1 for sample demographic characteristics. The mean age of the sample was 20.49 years (SD=1.58).

Table 1.

Sample Demographic Characteristics

| Variable | Percent | N |

|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 81 | 172 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| • Caucasian | 75 | 159 |

| • Asian-American | 13 | 27 |

| • African-American | 6 | 12 |

| • Hispanic/Latino | 3 | 6 |

| • Other | 4 | 8 |

| Year in school | ||

| • Freshman | 20 | 43 |

| • Sophomore | 22 | 47 |

| • Junior | 27 | 58 |

| • Senior | 21 | 45 |

| • Other | 9 | 19 |

| Eligibility risk factors | ||

| • Sunbathe 4+ hrs/wk in summer | 95 | 201 |

| • History of 2+ bad sunburns | 82 | 174 |

| • Wear sunscreen < 50% of the time in summer | 67 | 142 |

| • Have tanned indoors | 41 | 87 |

| • Family history of skin cancer | 37 | 78 |

Measures

The 64 items included for the current study were part of a larger survey. All items were rated on Likert-type scales unless otherwise noted. While similar items are used in many skin cancer prevention studies and have demonstrated construct and criterion validity, few standardized scales exist. We adapted existing scales by utilizing the combination of items that would produce the highest internal reliability for each scale within our population. Scores were calculated by adding the responses to the individual items unless otherwise noted. Higher scores indicate greater levels of the construct of interest unless otherwise noted. Internal reliabilities are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for Each Scale and Construct

| Possible Range |

Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD | Scale Alpha |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Background | ||||||

| Perceived damage | 3–21 | 3.00 | 20.00 | 10.34 | 3.53 | 0.82 |

| Damage distress | 5–25 | 5.00 | 25.00 | 14.77 | 4.02 | 0.85 |

| Attitudes | ||||||

| Behavioral beliefs protection | 0–30 | 0.00 | 25.00 | 18.25 | 6.93 | 0.88 |

| Behavioral beliefs exposure | 1–10 | 1.00 | 10.00 | 5.92 | 2.58 | 0.93 |

| Outcome evaluation protection |

0.20–5.00 | 0.27 | 4.33 | 1.53 | 0.72 | NA |

| Outcome evaluation exposure (pros/cons) |

0.20–5.00 | 0.20 | 5.00 | 1.46 | 0.93 | NA |

| Norms | ||||||

| Norms protection | 0–15 | 0.00 | 15.00 | 8.29 | 3.08 | 0.70 |

| Norms exposure | 0–10 | 0.00 | 10.00 | 6.34 | 2.54 | 0.84 |

| Prototype sunscreen user | 5–35 | 11.00 | 35.00 | 23.68 | 4.95 | 0.71 |

| Prototype sunbather | 5–35 | 5.00 | 31.00 | 17.13 | 4.95 | 0.68 |

| Prototype indoor tanner | 5–35 | 5.00 | 31.00 | 14.85 | 4.88 | 0.63 |

| Self-efficacy/control | ||||||

| Self-efficacy protection | 1–5 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.60 | 1.20 | one item |

| Self-efficacy exposure avoidance |

2–10 | 2.00 | 10.00 | 4.01 | 1.74 | one item |

| Control protection | 5–24 | 5.00 | 24.00 | 12.82 | 3.92 | 0.74 |

| Lack of control exposure | Yes, No | NA | NA | NA | NA | one item |

| Intentions | ||||||

| Intention to protect | 5–35 | 5.00 | 35.00 | 20.63 | 5.54 | 0.70 |

| Intention to sun expose | 1–7 | 1.00 | 7.00 | 3.84 | 1.79 | one item |

| Intention to indoor tan | 1–7 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.61 | 1.68 | one item |

Background/Individual Difference Variables

Perceived skin damage was assessed with 3 items asking participants to rate how much skin damage they have (1 = none, 7 = a lot), how likely they are to get skin cancer, and how likely it is that their skin will age prematurely compared to other people their age (1 = much less likely, 7 = much more likely).37,38 Distress about skin damage was assessed with 5 items (1 = never, 5 = all the time) asking about how often one worries about skin cancer, is bothered by seeing someone whose skin has been damaged by the sun, is upset by seeing someone aged by too much tanning, thinks about the damage to appearance that will result from too much sun, and worries that too much sun will make the skin look bad.39

Attitudes

Behavioral outcome beliefs about sunscreen was assessed with 6 items inquiring about reasons to wear sunscreen (e.g., “to reduce my skin cancer risk”). Higher scores (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) indicate greater beliefs in the effectiveness of sunscreen. Outcome evaluations for skin protection were assessed using a decisional balance scale calculated by dividing the average response to items on a pros of skin protection scale by the average response to items on a cons of skin protection scale (1 = not very important, 5 = extremely important).25, 39, 40 A sample pros item is “Using sunscreens allows me to enjoy the outdoors with less worry.” A sample cons item is “Sunscreen is more trouble than it’s worth.”

Behavioral outcome beliefs about UV exposure was assessed with 2 Fitzpatrick-type41 items asking about burning and tanning (“What would happen to your back if you were to go out for an hour in the midday sun in a bathing suit or without your shirt?”). Higher scores (1 = low, 5 = high) indicate a greater belief in one’s ability to tan without burning. Outcome evaluations for UV exposure was assessed using a decisional balance scale calculated by dividing the average response to items on a pros of UV exposure scale by the average response to items on a cons of UV exposure scale (1 = not very important, 5 = extremely important).25, 39, 40 A sample pros item is “I look better when I have a tan.” A sample cons item is “Having a tan is unhealthy.”

Norms

Normative beliefs for protection were assessed using 2 items (“My friends use sunscreen” and “Natural skin color is fashionable,” 1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Higher scores indicate greater perceived popularity of skin protection. We also assessed sunscreen user prototype, with higher scores indicating greater perceived favorability of one’s image of a prototypical sunscreen user. This variable was assessed by having participants rate the extent to which their image of a prototypical sunscreen user possesses 5 positive and negative attributes (e.g., attractive, careless; 1 = not at all, 7 = extremely, a = .77).37

Normative beliefs for UV exposure were assessed using 2 items (“Being tan is fashionable” and “My friends think I look better with a tan,” 1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Higher scores indicate greater perceived popularity of tanning. We also assessed tanner prototypes with higher scores indicating greater perceived favorability of one’s image of a prototypical sunbather or indoor tanner. These variables were assessed by having participants rate the extent to which their image of a prototypical sunbather or indoor tanner possesses 5 positive and negative attributes (e.g., attractive, careless; 1 = not at all, 7 = extremely, a = .77).37

Self-Efficacy/Control

Self-efficacy for skin protection was assessed using one item (“How confident are you that you could use sunscreen whenever you are out in the summer for more than 15 minutes?” 1 = not at all, 5 = extremely).38, 42, 43 Three items assessed perception of being in control of skin protection behaviors such as use of sunscreen and protective clothing despite barriers such as feeling hot or unattractive (1 = not at all, 5 = extremely).38, 42, 43

Self-efficacy to avoid UV exposure was assessed with one item asking participants about their confidence in their ability to avoid UV exposure (1 = not at all, 5 = extremely).38, 42, 43 UV exposure control was assessed with one item asking participants to respond yes or no when asked whether they usually spend more time exposing themselves to UV than they had planned.18 Responses were coded 1 for yes and 2 for no.

Intentions

Skin protection intention was assessed with 5 items asking about plans to use sunscreen, protective clothing, and shade as well as check skin for skin cancer and receive professional skin exams (1 = definitely not, 7 = definitely yes).40 Intention to sun expose was assessed using one item asking about willingness to spend the day outside with friends on a hot sunny day (1 = not at all, 5 = very).37 Intention to indoor tan was assessed by asking participants how willing they would be to use a gift certificate for free indoor tanning (1 = not at all, 5 = very).37

Analyses

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations among variables were performed (See Tables 1–3). Three hierarchical regressions were conducted predicting skin protection, sun exposure, and indoor tanning intentions. Hierarchical regression permits entering one subset of variables at a time to identify how each contributes to explaining the variance of the target variable. The order of entry of the variables is determined by the researcher based on theory rather than a statistical program, in contrast to stepwise regression.44 Another approach that has been used previously in the psychological literature is to conduct multivariable regressions based on the results of bivariate correlational analyses. However, this can lead to model over-fitting and thus results may not generalize to other samples.45 The following subsets of variables were entered into the models predicting intentions in the order described by the IM: background variables, attitudes, norms, and self-efficacy/behavioral control. Thus, a hierarchical regression for each intention outcome was performed. Step 1 included the background/individual difference variables: perceived skin damage and skin damage distress. Step 2 included behavioral outcome beliefs for protection or exposure and outcome evaluations for protection or exposure. Step 3 included norms for protection or exposure and protection or exposure prototypes. Step 4 included self-efficacy for protection or exposure and perceived control over protection or exposure. While we could have entered the variables into the regressions in an order based on the variables’ relative importance to each model from the literature, we wanted to remain consistent across the outcomes so that we could compare among them.

Table 3.

Correlations among Variables of Interest

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PROTECTION | |||||||||

| 1. Perceived Damage | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 2. Damage Distress | 0.28* | 1.00 | |||||||

| 3.Behavioral Beliefs | 0.05 | 0.33** | 1.00 | ||||||

| 4.Outcome Evaluation | 0.01 | .032** | 0.29** | 1.00 | |||||

| 5. Norms | −0.01 | 0.15* | 0.43** | 0.02 | 1.00 | ||||

| 6.Prototypes | −0.07 | 0.34** | 0.26** | 0.30** | 0.20** | 1.00 | |||

| 7. Self-efficacy | 0.04 | 0.21** | 0.24** | 0.47** | 0.18* | 0.29** | 1.00 | ||

| 8. Control | −0.04 | 0.13 | 0.15* | 0.24** | 0.22* | 0.15* | 0.41** | 1.00 | |

| 9. Intentions | 0.06 | 0.39** | 0.28** | 0.39** | 0.19** | 0.29** | 0.42** | 0.34** | 1.00 |

| SUNBATHING | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. |

| 1. Perceived Damage | 1 | ||||||||

| 2. Damage Distress | 0.28* | 1 | |||||||

| 3.Behavioral Beliefs | −0.27** | −0.18* | 1 | ||||||

| 4.Outcome Evaluation | 0.12 | − 0.21** |

0.11 | 1 | |||||

| 5. Norms | 0.24** | 0.05 | −0.05 | 0.50** | 1 | ||||

| 6.Prototypes | 0.10 | − 0.21** |

0.03 | 0.42** | 0.32** | 1 | |||

| 7. Self-efficacy to avoid UV |

−0.14* | 0.05 | −0.08 | − 0.25** |

− 0.27** |

−0.10 | 1 | ||

| 8. Lack of control | −0.10 | −0.07 | 0.11 | 0.00 | −0.10 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 1 | |

| 9. Intentions | 0.05 | −0.14* | 0.24** | 0.27** | 0.21** | 0.17* | −0.40** | −0.04 | 1 |

|

INDOOR TANNING |

1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. |

| 1. Perceived Damage | 1 | ||||||||

| 2. Damage Distress | 0.28* | 1 | |||||||

| 3.Behavioral Beliefs | −0.27** | −0.18* | 1 | ||||||

| 4.Outcome Evaluation | 0.12 | − 0.21** |

0.11 | 1 | |||||

| 5. Norms | 0.24** | 0.05 | −0.05 | 0.50** | 1 | ||||

| 6.Prototypes | 0.07 | − 0.33** |

−0.09 | −0.09 | 0.28** | 1 | |||

| 7. Self-efficacy to avoid UV |

−0.14* | 0.05 | −0.08 | −0.25** | −0.27** | −0.10 | 1 | ||

| 8. Lack of control | −0.10 | −0.07 | 0.11 | 0.00 | −0.10 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 1 | |

| 9. Intentions | 0.28** | 0.03 | −0.13 | 0.44** | 0.42** | 0.31** | −0.20** | −0.09 | 1 |

P < .05,

P < .01

RESULTS

Descriptive characteristics of the variables included in the regression analyses are provided in Table 2. Mean reported skin protection and sun exposure intentions were in the middle of the range of possible responses. However, mean intentions to tan indoors were lower, and no participants selected the 2 highest possible ratings. Additionally, there was less variability in intentions to protect one’s skin relative to the 2 exposure intentions variables. Interestingly, 43% of the sample indicated a lack of perceived behavioral control over UV exposure, reporting that they usually spend more time exposing themselves to UV than they had planned.

Table 3 is a correlation matrix of the variables included in the regression analyses. For ease of presentation, the correlation table is divided by outcome variable since the correlations of the variables within, rather than between, each model are most relevant for the regression analyses. With regard to multicollinearity, none of the variables in the same model had Pearson’s correlations with one another greater than 0.50, which is well below the general rule of thumb of 0.95 46. The correlations among the outcome variables were −0.34 for protection and sun exposure intentions, −0.35 for protection and indoor tanning intentions, and 0.20 for sun exposure and indoor tanning intentions (all Ps < 0.01).

Skin protection intention

According to the first hierarchical regression, the variables that were found to independently contribute to variability in skin protection intention were skin damage distress, self-efficacy for skin protection, and perceived control over skin protection, with the model accounting for 34% (P<.001) of the variance in skin protection intention overall (Table 4).

Table 4.

Hierarchical Regression Results Describing Variables Contributing to Intentions

| Protection (n=195) | Sunbathing (n=191) | Indoor Tanning (n=189) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | R2 | R2 change |

Beta | t | Sig. | R2 | R2 change |

Beta | t | Sig. | R2 | R2 change |

Beta | t | Sig |

| Step 1. Background | .172 | .172 | .000 | .026 | .026 | .085 | .075 | .075 | .001 | ||||||

| Perceived damage | −.008 | −.125 | .901 | .023 | .322 | .748 | .139 | 2.075 | .039 | ||||||

| Damage distress | .270 | 3.88 | .000 | −.084 | −1.194 | .234 | .077 | 1.084 | .280 | ||||||

| Step 2. Attitudes | .267 | .094 | .000 | .136 | .110 | .000 | .252 | .177 | .000 | ||||||

| Outcome beliefs | .106 | 1.50 | .135 | .217 | 3.220 | .0[0]2 | −.098 | −1.501 | .135 | ||||||

| Outcome evaluation | .131 | 1.77 | .079 | .089 | 1.088 | .278 | .273 | 3.570 | .000 | ||||||

| Step 3. Norms | .274 | .007 | .408 | .149 | .013 | .254 | .317 | .065 | .000 | ||||||

| Prototype | .017 | .249 | .803 | .029 | .408 | .683 | .142 | 2.026 | .044 | ||||||

| Norms | .020 | .286 | .803 | .062 | .778 | .438 | .223 | 2.920 | .004 | ||||||

|

Step 4. Efficacy/ Control |

.343 | .069 | .000 | .254 | .105 | .000 | .319 | .002 | .780 | ||||||

| Control | .191 | 2.63 | .009 | −.049 | −.745 | .457 | −.000 | −.000 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Self-efficacy | .167 | 2.55 | .012 | −.341 | −5.029 | .000 | −.046 | −.705 | .482 | ||||||

Sun exposure intention

In the second hierarchical regression, the variables that were found to independently contribute to sun exposure intention were UV exposure outcome beliefs and sun exposure avoidance self-efficacy (an expected inverse relationship), with the model accounting for 25% (P<.001) of the variance in sun exposure intention overall (Table 4).

Intention to indoor tan

In the third hierarchical regression, the variables that were found to independently contribute to intention to indoor tan were perceived skin damage, outcome evaluations, indoor tanner prototype, and norms for exposure, with the model accounting for 32% (P<.001) of the variance in indoor tanning intention (Table 4). Unlike in the previous models, self-efficacy/control did not contribute independently to the model.

We do not report models including demographic variables because we were interested in focusing on variables that could be modified through intervention. However, when we included demographic variables as the first step of the regressions, they did not modify the nature of the findings. The demographic variables included were sex, race, and family history of skin cancer. The only demographic variable that was a significant independent predictor of intentions was having a family history of skin cancer, which was significantly associated with lower intentions to sun expose.

Discussion

The development of successful interventions to alter health behaviors such as UV protection and exposure is largely dependent upon understanding the attitudes and beliefs that predict specific behaviors and behavioral intentions. The current study provides evidence for attitudes and beliefs that are closely related to UV protection and exposure intentions among young adults. In the discussion that follows, we summarize the study results, compare our results with the existing literature, and discuss the implications of these findings for descriptive and intervention research.

As hypothesized, the key IM constructs – background/individual variables, attitudes, beliefs, norms, and self-efficacy - played a role in predicting skin protection, sun exposure, and indoor tanning intentions. With regard to skin protection, distress about skin damage (a background/individual construct), sunscreen self-efficacy (a self-efficacy construct), and perceived behavioral control over skin protection (a self-efficacy construct) contributed independently to intentions, with the overall model accounting for 34% of the variance. With regard to sun exposure, behavioral outcome beliefs about one’s ability to tan without burning (a beliefs construct) and low self-efficacy for sun avoidance (a self-efficacy construct) contributed independently to intentions, with the overall model accounting for 25% of the variance. Finally, with regard to indoor tanning, perceived skin damage (a background/individual construct), tanning outcome evaluation (a beliefs construct), tanning norms (a norms construct), and favorability of one’s image of a prototypical indoor tanner (a norms construct) contributed independently to intentions, with the overall model accounting for 32% of the variance. Thus, IM variables accounted for a significant amount of variance in each of the models of skin protection and UV exposure intentions.

We originally predicted that similar attitudes and beliefs would be associated with both indoor and outdoor exposure intentions and that skin protection and exposure intentions would be associated with similar variables but that these relationships would be in opposite directions of one another. However, skin protection, indoor exposure, and outdoor exposure intentions were associated with both common and unique attitudes and beliefs, but not always in the ways we hypothesized.

The only correlate that was common to 2 behavioral intentions was self-efficacy, providing some support of our hypothesis that self-efficacy would be associated with all the behavioral intentions. Consistent with previous work, self-efficacy was found to be an important common correlate in both skin protection and sun exposure intentions models. However, self-efficacy was not associated with indoor tanning in the current study. While one might consider skin protection behaviors to be relatively simple health behaviors compared to others (e.g., quitting smoking, weight loss), the degree of self-efficacy for skin protection varies across individuals. Some individuals may intend to protect their skin in general, but may have low self-efficacy for sustaining skin protection behaviors as is required to reduce risk for skin cancer. Interventions designed to reduce sun exposure and increase skin protection could be strengthened by focusing on enhancing self-efficacy to maintain long-term protective habits despite potential social and situational barriers.

In addition to self-efficacy, we hypothesized that the remaining IM constructs would also be associated with more than one of the behavioral intentions. However, contrary to these predictions, the other 7 independent correlates identified were unique to only one of the 3 behavioral intentions. Correlates associated with only one outcome included background, attitude, and norms variables. For example, norms only contributed to indoor tanning intentions. It is particularly surprising that normative beliefs were not significant in the sun exposure model since sunbathing is often a social activity. However, it makes sense that normative beliefs would be more important for indoor tanning since the reinforcing properties of sunbathing are broader or more generalized (e.g., vacation, the outdoors/nature, socializing) than those of indoor tanning, which is more narrowly limited to UV exposure for attractiveness reasons. Interventions to reduce indoor tanning should include attempts to alter normative perceptions of indoor tanning among others. Together these differences suggest that outdoor and indoor tanning have unique behavioral correlates. Thus, interventions within the overarching domain of skin cancer risk reduction may need to be targeted specifically for each type of exposure behavior. This finding is consistent with a prior study that also reported on the distinctiveness of sun exposure and protection behavior.47 However, in that study, self-efficacy predicted sun protection but not intention to limit sun exposure.47

These data provide evidence for which IM beliefs are most closely related to which behavioral intentions among young adults. According to Hornik and Woolf,48 successful behavioral interventions should target beliefs that are related to the behavior and are changeable and individuals who do not already hold the belief. Future trials could target individuals who do not hold the beliefs and tailor intervention components to focus on the specific beliefs of each individual. For example, one of the strongest IM correlates identified was outcome evaluation beliefs for intentions to indoor tan. Thus, a successful intervention to reduce indoor tanning should focus on minimizing beliefs about indoor tanning’s positive effects such as attractiveness of a tanned appearance and maximizing beliefs about negative effects such as burning, dry skin, fake appearance, cost, and time. Indeed, several trials that have taken such an approach have produced significant reductions in indoor tanning.

IM interventions focusing on the self-efficacy construct could be useful for both increasing skin protection as well as reducing sun exposure. There are a number of potential thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that may contribute to these behaviors. For example, there are several ways to protect one’s skin including wearing various types of clothing and accessories and applying broad-spectrum high-SPF sunscreen thickly and regularly several times a day. Interventions designed to increase sustained self-efficacy would need to help participants to be aware of the specifics of how to protect the skin, obtain the appropriate items, plan ahead, remember the items, motivate him or herself to use the items, potentially handle criticism from others (e.g., “You look so pale.”). In a prior study, self-efficacy for skin self-examination was also found to be a significant mediator of a skin self-examination intervention among individuals at high risk for melanoma.29 However, it is unknown which aspect of self-efficacy is most important for initiating and maintaining behavior. Of course, this would also likely vary from behavior to behavior and/or population to population.

The Integrative Model has not previously been investigated in the domain of skin cancer risk reduction, and most prior skin cancer prevention studies have focused on one prevention outcome and have not compared across 3 related outcomes within a single study and participant sample. Thus it has been difficult to discern whether differences in study findings can be accounted for by variations across behaviors, samples, or procedures. The current study demonstrated that the IM components relevant to each particular health behavior varied in importance across behaviors, even behaviors within the same domain (e.g., skin cancer risk reduction behaviors), as was proposed by Fishbein and Cappella.8 Strengths of the current study include the interpretation of associations among 3 unique but related behavioral intentions within the IM theoretical framework which allows for additional hypothesis generation to guide future research and prevention intervention development in this area. These findings offer the potential for improving the impact of behavioral interventions on reducing skin cancer incidence.

Limitations include the cross-sectional nature of the data and the assessment of intentions rather than behaviors. Additionally, a convenience sample of primarily Caucasian female college students was used; thus, participants may have been more interested in skin cancer prevention than non-participants. Skin cancer-related belief measures are not standardized, and there was quite a bit of variability in responses to some of the scales. Finally, 5 variables were assessed with one item.

Future prospective research should investigate whether the variables identified here predict actual behaviors in addition to being associated with intentions, which we will be able to do as our intervention trial concludes. It is well-known that intentions are not perfectly correlated with behaviors. For example, one study of parents found intentions to be the most important predictor of sunscreen use,49 whereas another study of fifth graders found that intentions were not significantly associated with sunscreen use.50 Most studies focus on one population, but future research should investigate differences in behavioral correlates by population such as children, young adults, and older adults.

In summary, the current study identified several background, attitudinal, normative, and self-efficacy variables that were independently associated with skin protection, sun exposure, and indoor tanning intentions among young adults. The behavior significantly associated with both sun protection and exposure intentions was self-efficacy. We identified a number of unique correlates of these 3 behavioral intentions. The current findings suggest targeting these unique correlates of each behavioral intention in order to obtain optimal intervention outcomes. Research into future intervention efforts should evaluate whether these variables predict actual behavior over time.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by K07CA108685 (Heckman), K05CA109008 (Manne), and CA006927 (FCCC Center Grant). The authors would like to thank Makary Hoffman, Sara Filseth, Lauren Daniel, and Jeanne Pomenti for their assistance with data collection and manuscript preparation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ibrahim SF, Brown MD. Tanning and cutaneous malignancy. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34(4):460–474. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.34092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christenson LJ, Borrowman TA, Vachon CM, et al. Incidence of basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas in a population younger than 40 years. JAMA. 2005;294(6):681–690. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.6.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baron ED, Kirkland EB, Domingo DS. Advances in photoprotection. Dermatol Nurs. 2008;20(4):265–272. quiz 273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coups EJ, Manne SL, Heckman CJ. Multiple skin cancer risk behaviors in the U.S population. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(2):87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heckman CJ, Coups EJ, Manne SL. Prevalence and correlates of indoor tanning among US adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(5):769–780. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacNeal RJ, Dinulos JG. Update on sun protection and tanning in children. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2007;19(4):425–429. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e3282294936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robinson NG, White KM, Young RM, et al. Young people and sun safety: the role of attitudes, norms and control factors. Health Promot J Austr. 2008;19(1):45–51. doi: 10.1071/he08045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fishbein M, Cappella JN. The role of theory in developing effective health communications. J Commun. 2006;56:S1–S17. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jackson KM, Aiken LS. Evaluation of a multicomponent appearance-based sun-protective intervention for young women: uncovering the mechanisms of program efficacy. Health Psychol. 2006;25(1):34–46. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hillhouse JJ, Stair AW, 3rd, Adler CM. Predictors of sunbathing and sunscreen use in college undergraduates. J Behav Med. 1996;19(6):543–561. doi: 10.1007/BF01904903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thieden E, Philipsen PA, Sandby-Moller J, Wulf HC. Sunscreen use related to UV exposure, age, sex, and occupation based on personal dosimeter readings and sun-exposure behavior diaries. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141(8):967–973. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.8.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wichstrom L. Predictors of Norwegian adolescents' sunbathing and use of sunscreen. Health Psychol. 1994;13(5):412–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arthey S, Clarke VA. Suntanning and sun protection: a review of the psychological literature. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40(2):265–274. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)e0063-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borland R, Hill DN, Noy S. Being sunsmart: changes in community awareness and reported behaviour following a primary prevention program for skin cancer control. Behaviour Change. 1990;7(3):126–135. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heckman CJ, Egleston BL, Wilson DB, Ingersoll KS. A preliminary investigation of the predictors of tanning dependence. Am J Health Behav. 2008;32(5):451–464. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2008.32.5.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaur M, Liguori A, Lang W, et al. Induction of withdrawal-like symptoms in a small randomized, controlled trial of opioid blockade in frequent tanners. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(4):709–711. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.11.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poorsattar SP, Hornung RL. UV light abuse and high-risk tanning behavior among undergraduate college students. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(3):375–379. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.08.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Warthan MM, Uchida T, Wagner RF., Jr UV light tanning as a type of substance-related disorder. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141(8):963–966. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.8.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeller S, Lazovich D, Forster J, Widome R. Do adolescent indoor tanners exhibit dependency? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(4):589–596. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Azzarello LM, Dessureault S, Jacobsen PB. Sun-protective behavior among individuals with a family history of melanoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(1):142–145. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Branstrom R, Ullen H, Brandberg Y. Attitudes, subjective norms and perception of behavioural control as predictors of sun-related behaviour in Swedish adults. Prev Med. 2004;39(5):992–999. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hammond V, Reeder AI, Gray AR, Bell ML. Are workers or their workplaces the key to occupational sun protection? Health Promot J Austr. 2008;19(2):97–101. doi: 10.1071/he08097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahler HI, Kulik JA, Butler HA, et al. Social norms information enhances the efficacy of an appearance-based sun protection intervention. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(2):321–329. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olson AL, Gaffney CA, Starr P, Dietrich AJ. The impact of an appearance-based educational intervention on adolescent intention to use sunscreen. Health Educ Res. 2008;23(5):763–769. doi: 10.1093/her/cym005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adams MA, Norman GJ, Hovell MF, et al. Reconceptualizing decisional balance in an adolescent sun protection intervention: mediating effects and theoretical interpretations. Health Psychol. 2009;28(2):217–225. doi: 10.1037/a0012989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cafri G, Thompson JK, Roehrig M, et al. An investigation of appearance motives for tanning: The development and evaluation of the Physical Appearance Reasons For Tanning Scale (PARTS) and its relation to sunbathing and indoor tanning intentions. Body Image. 2006;3(3):199–209. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manne S, Lessin S. Prevalence and correlates of sun protection and skin self-examination practices among cutaneous malignant melanoma survivors. J Behav Med. 2006;29(5):419–434. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gritz ER, Tripp MK, de Moor CA, et al. Skin cancer prevention counseling and clinical practices of pediatricians. Pediatr Dermatol. 2003;20(1):16–24. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2003.03004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hay JL, Oliveria SA, Dusza SW, et al. Psychosocial mediators of a nurse intervention to increase skin self-examination in patients at high risk for melanoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(6):1212–1216. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hillhouse JJ, Adler CM, Drinnon J, Turrisi R. Application of Azjen's theory of planned behavior to predict sunbathing, tanning salon use, and sunscreen use intentions and behaviors. J Behav Med. 1997;20(4):365–378. doi: 10.1023/a:1025517130513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.James AS, Tripp MK, Parcel GS, et al. Psychosocial correlates of sun-protective practices of preschool staff toward their students. Health Educ Res. 2002;17(3):305–314. doi: 10.1093/her/17.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Myers LB, Horswill MS. Social cognitive predictors of sun protection intention and behavior. Behav Med. 2006;32(2):57–63. doi: 10.3200/BMED.32.2.57-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stryker JE, Lazovich D, Forster JL, et al. Maternal/female caregiver influences on adolescent indoor tanning. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35(6):e521–e529. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.02.014. 528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hillhouse J, Turrisi R, Stapleton J, Robinson J. A randomized controlled trial of an appearance-focused intervention to prevent skin cancer. Cancer. 2008;113(11):3257–3266. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Danoff-Burg S, Mosher CE. Predictors of tanning salon use: behavioral alternatives for enhancing appearance, relaxing and socializing. J Health Psychol. 2006;11(3):511–518. doi: 10.1177/1359105306063325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hillhouse JJ, Turrisi R, Kastner M. Modeling tanning salon behavioral tendencies using appearance motivation, self-monitoring and the theory of planned behavior. Health Educ Res. 2000;15(4):405–414. doi: 10.1093/her/15.4.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Lane DJ, et al. Using UV photography to reduce use of tanning booths: a test of cognitive mediation. Health Psychol. 2005;24(4):358–363. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.4.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mahler HI, Fitzpatrick B, Parker P, Lapin A. The relative effects of a health-based versus an appearance-based intervention designed to increase sunscreen use. Am J Health Promot. 1997;11(6):426–429. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-11.6.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson K, Davy L, Boyett T, et al. Sun protection practices for children: knowledge, attitudes, and parent behaviors. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(8):891–896. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.8.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mahler HI, Kulik JA, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX. Long-term effects of appearance-based interventions on sun protection behaviors. Health Psychol. 2007;26(3):350–360. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.3.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fitzpatrick TB. The validity and practicality of sun-reactive skin types I through VI. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124(6):869–871. doi: 10.1001/archderm.124.6.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rossi JS, Blais LM, Redding CA, et al. Preventing skin cancer through behavior change. Implications for interventions. Dermatol Clin. 1995;13(3):613–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rossi JS, Blais LM, Weinstock MA. The Rhode Island Sun Smart Project: skin cancer prevention reaches the beaches. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(4):672–674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garson G. [Accessed June 16, 2009];Multiple Regression. Available at: http://faculty.chass.ncsu.edu/garson/PA765/regress.htm.

- 45.Babyak MA. What you see may not be what you get: a brief, nontechnical introduction to overfitting in regression-type models. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(3):411–421. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000127692.23278.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kutner MH, Nachtsheim C, Neter J. Applied Linear Regression Models. McGraw-Hill Irwin; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jackson KM, Aiken LS. A psychosocial model of sun protection and sunbathing in young women: the impact of health beliefs, attitudes, norms, and self-efficacy for sun protection. Health Psychol. 2000;19(5):469–478. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.5.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hornik R, Woolf KD. Using cross-sectional surveys to plan message strategies. Social Marketing Quarterly. 1999;5:34–41. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Van Osch L, Reubsaet A, Lechner L, et al. Predicting parental sunscreen use: Disentangling the role of action planning in the intention-behavior relationship. Psychology & Health. 2008;23(7):829–847. doi: 10.1080/08870440701596577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kubar WL, Rodrigue JR, Hoffmann RGI. Children and exposure to the sun: Relationships among attitudes, knowledge, intentions, and behavior. Psychol Rep. 1995;77(3, Pt 2):1136–1138. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1995.77.3f.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]