Abstract

Purpose

To determine if tumor regression following treatment with gefitinib correlates with the presence of sensitizing mutations in EGFR.

Patients and Methods

Patients with resectable stage I and II non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) enriched for the likelihood of EGFR mutation (≤ 15 pack year cigarette smoking history and/or a component of bronchioloalveolar carcinoma) received preoperative gefitinib for 21 days. Tumor specimens were analyzed for EGFR and KRAS mutations and EGFR protein expression and amplification. Patients with ≥ 25% reduction in tumor size measured bidimensionally at 3 weeks and/or patients with an EGFR mutation received adjuvant gefitinib for 2 years post-operatively.

Results

50 patients with stage I/II NSCLC were treated. After 21 days of preoperative gefitinib a response of ≥ 25% was observed in 21/50 (42%) patients. 17/21 patients with a response had an EGFR mutation and 4/21 patients with a response did not (p=0.0001). 25/50 patients were eligible to receive adjuvant gefitinib. With a median follow-up of 44.1 months, 2-year disease free survival for EGFR mutant patients and for those who received adjuvant gefitinib was not statistically different than those who were EGFR wild-type and those who did not receive adjuvant gefitinib. The median disease free and overall survivals have not been reached.

Conclusions

The presence of sensitizing EGFR mutations correlates with radiographic response. A short course of preoperative treatment serves a platform for evaluating activity of new agents and assures sufficient tumor availability for correlative analyses.

Introduction

Initial clinical trials testing the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) gefitinib and erlotinib demonstrated dramatic but sporadic responses in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (1, 2). Although these agents were developed to inhibit wild-type EGFR, the true mechanism of this impressive activity in patients was not initially known. Retrospective reviews showed that the majority of responders were patients who were never smokers or whose tumors were adenocarcinomas with bronchioloalveolar features (3). In 2004, molecular analyses of the tumors from these responders demonstrated somatic mutations in the tyrosine kinase domain of EGFR (4–6). This discovery led us to embark upon this prospective trial to correlate radiographic response to gefitinib with the presence of a sensitizing mutation in EGFR.

When this study was conceived, the EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors were only being tested in advanced disease, a situation in which often only limited diagnostic material was available. As a result, due to the complexity of testing for EGFR mutations at that time, the initial exploratory analyses of EGFR mutation status were performed only in subgroup analyses conducted in a minority of individuals in each trial (7, 8). While many of these initial limitations have been rectified in more recent studies, we employed this research strategy to provide an in vivo assessment of gefitinib sensitivity prior to a definitive surgery to ensure sufficient tissue for EGFR mutation analysis in all patients.

We tested the hypothesis that mutations in the protein-tyrosine kinase domain of the EGF receptor gene (exon regions 18–24 of the EGFR gene) correlate with response to gefitinib. By evaluating patients with Stage I and II NSCLC with clinical features that predict for gefitinib response (never or minimal smokers and/or features of BAC) we hoped to enrich for response to gefitinib and the likelihood of finding EGFR sensitizing mutations. We were also able to obtain adequate tissue post-treatment at surgery. Using CT scans to measure primary lung lesions we precisely identified the responders and non-responders preoperatively. In addition, we also explored the feasibility of using preoperative response to gefitinib as a means to select patients for gefitinib treatment post-operatively. We postulated that adjuvant therapy selection based on in vivo sensitivity testing or mutation status may be better than the current standard of empiric assignments of post-operative therapies, although this study was not powered to detect a survival benefit from adjuvant gefitinib.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Eligibility

Eligible patients had pathologically confirmed clinical stage I or II NSCLC (T1-2N0-1M0 or T3N0M0) and were determined to be both operable and resectable by the treating thoracic surgeon. Patients must have been a never smoker (<100 cigarettes lifetime) or have a history of smoking ≤ 15 pack years and/or have tumor specimens containing adenocarcinoma with bronchioloalveolar features at the time of diagnostic biopsy(9, 10).

Initially, the study required that all patients undergo a core needle biopsy for mutation testing pretreatment. This requirement was removed after the first 18 patients as we observed 100% concordance of results of mutation testing in pretreatment core biopsies and resection specimens. This finding has been previously reported.(11)

Treatment Plan

The protocol and informed consent documents were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC). Patients received gefitinib 250 mg orally daily for at least 21 days before surgery and stopped gefitinib 2 days before their operation. Patients underwent a helical CT scan of the chest pre-gefitinib and after 21 days of gefitinib. Standard response endpoints are evaluated at least 6–8 weeks after therapy is initiated; given the short time interval between initiation of gefitinib and response assessment we chose a minor response by WHO criteria as our response endpoint. (12)

At surgery, the tumor was snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. For patients that demonstrated a radiographic response to gefitinib preoperatively and/or patients with mutations in the protein-tyrosine kinase domain of the EGFR, gefitinib was recommended for 2 additional years.

Patients receiving gefitinib post-operatively resumed treatment at least 7 days after surgery. Patients were allowed to receive adjuvant chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy if appropriate for their pathologic disease stage. In these individuals, post-operative gefitinib was started after chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy was completed.

Molecular Profiling

All tissues obtained during the study were stored at −80 degrees. Representative areas of these specimens were embedded in O.C.T., 5µm frozen sections were prepared cut and placed on Superfrost/Plus slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and reviewed by a pathologist to confirm the diagnosis and the presence of tumor in the specimen. Genomic DNA was analyzed for known EGFR mutations (exons 19 deletions and L858R) and KRAS mutations. Tissues were also analyzed for EGFR protein expression by IHC (immunohistochemistry) and EGFR gene copy number by CISH (chromogenic in situ hybridization). If no mutations were found in KRAS, EGFR exons 18 – 24 were sequenced by dideoxynucleotide sequencing. Patients without an identified mutation were further characterized by mass spectrometry based genotyping (Sequenom® platform) for the presence of mutations in KRAS, EGFR, HER2, BRAF, PIK3CA, AKT, NRAS, and MEK. The methods for the above tests were as previously described (4, 13–15).

Statistical Plan

The primary objective was to correlate the radiographic response to gefitinib (≥ 25% decrease in bidimensional measurements at 21 days) with the presence of mutations in the protein-tyrosine kinase domain of EGFR. Each patient provided two binary variables: presence/absence of mutation and responder/non-responder. The association between the two was tested using the Fisher's exact test for the resulting 2×2 table. In this enriched study population the expected response rate was 25%. We proposed to accrue 50 patients to the protocol. This sample size enabled us to detect a difference of 55% in the mutation rates among the responders and non-responders with at least 89% power. If 75% of the responders have a mutation and 20% of the non-responders do, this study would have 89% power.

Results

Patient Characteristics

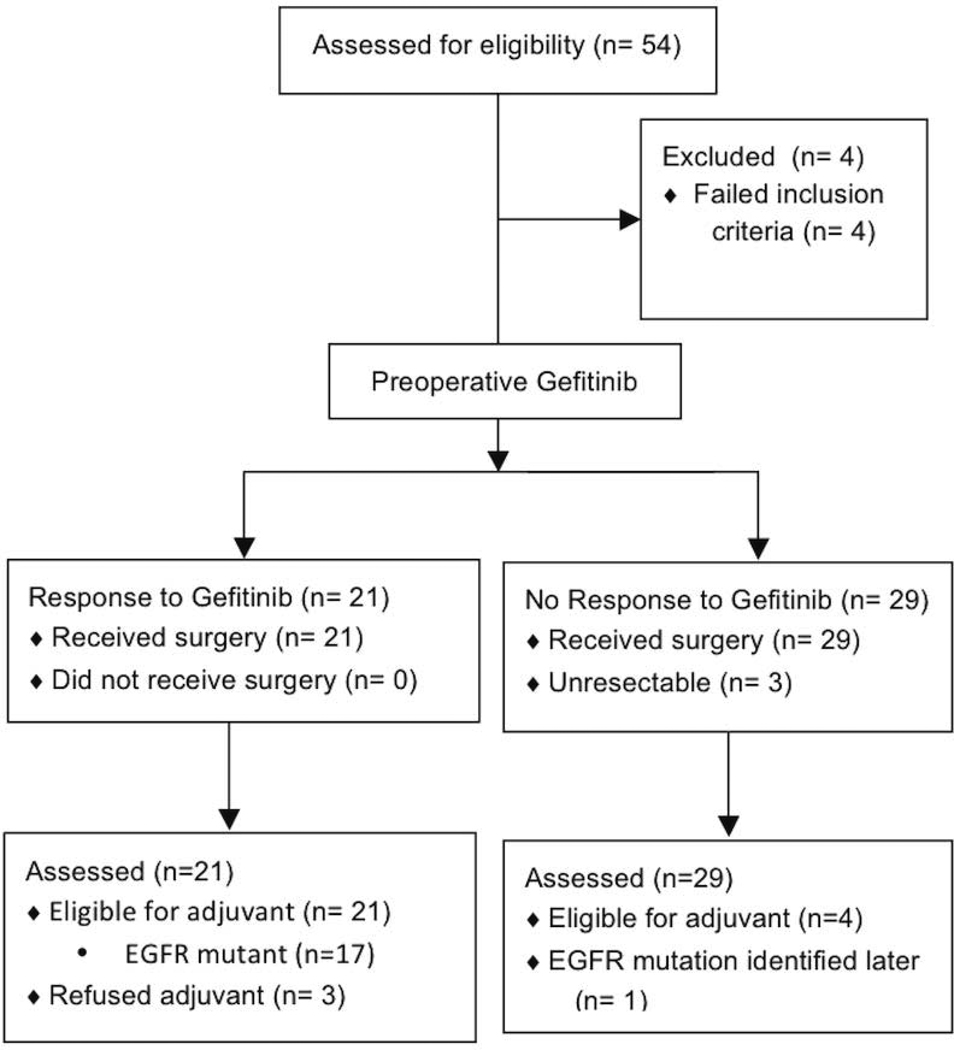

Between July 2004 and March 2008, 54 patients were screened and 50 patients were treated. Pre-treatment tumor specimens were procured from the initial 18 patients by core needle biopsy as well as post-treatment at the time of surgical resection. The subsequent 32 patients had tumor procured only at the time of surgery.

Patient characteristics are listed in Table 1. There were 39 women and 11 men. 49/50 patients were either clinical stage IA (28) or stage IB (21); there was 1 patient who was clinical stage IIB. The majority of patients were either never smokers (18/50) or ≤ 15 pack year smokers (23/50). There were 9/50 patients eligible based on the diagnosis of adenocarcinoma with bronchioloalveolar features alone.

Table 1.

Pretreatment patient characteristics.

| Resection dates: 8/19/04 – 4/25/08 | 50 |

| Men / Women | 11 / 39 |

| Clinical Stage | |

| IA | 28 |

| IB | 21 |

| IIA | 0 |

| IIB | 1 |

| Median Karnofsky Performance Status | 90 |

| Median Age [range] | 67 [36 – 84] |

| Never-smokers | 18 |

| ≤ 15 pack year | 23 |

| > 15 pack year | 9 |

| Bronchioloalveolar Features | 25 |

Surgical Results

All 50 patients underwent surgery without complications attributable to preoperative gefitinib. Post-operative complications included pneumonitis (2), atrial fibrillation (2), supraventricular arrhythmia (1), air leak (3), and intraoperative injury to right main pulmonary artery (1). There were no surgery related deaths. 41/50 patients underwent a lobectomy. Of the 50 patients that underwent surgery, 3 were deemed unresectable (1 with unresectable stage III disease and 2 with stage IV disease). 3 patients underwent wedge resection; 2 patients underwent bilobectomy and 1 patient underwent pneumonectomy. The majority of patients stage did not change (34/50); 9/50 patients were upstaged at surgery and 7/50 patients were downstaged.

Response rate and molecular results

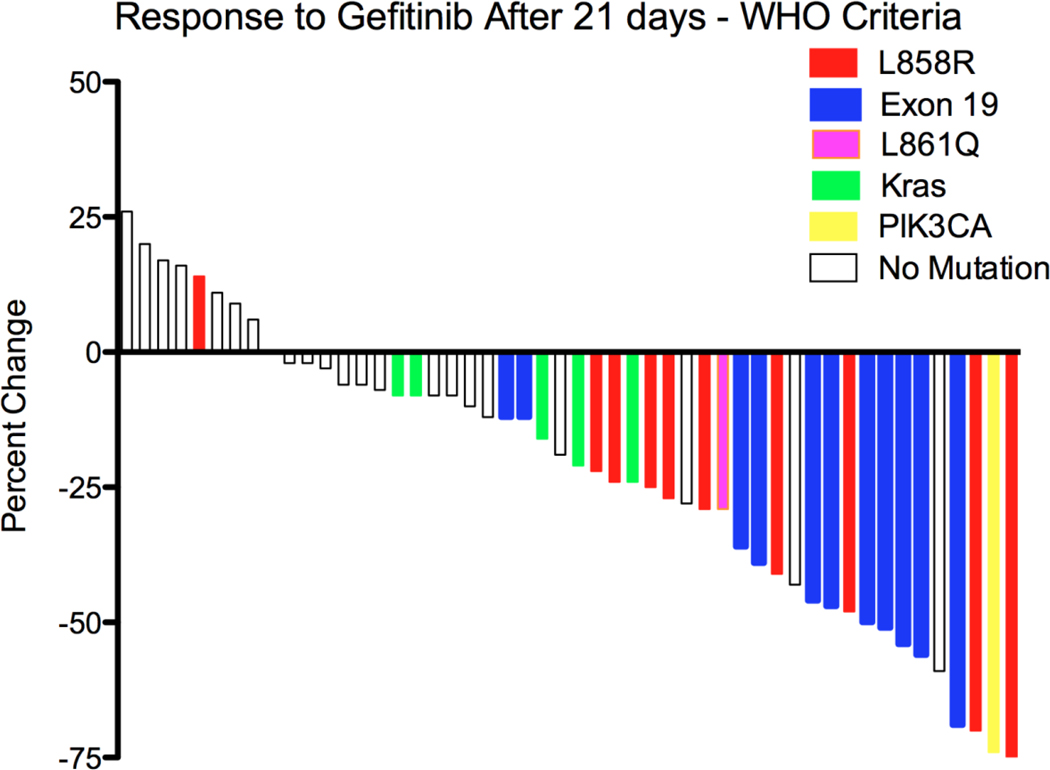

After 21 days of preoperative gefitinib, a bidimensional response of ≥ 25% was observed in 21/50 (42%) patients. The mutations identified and the percent change in tumor size is shown in Table 2 and the waterfall response plot for all patients is shown in Figure 2. Seventeen of 21 patients with a response had an EGFR mutation and 4/21 patients with a response did not (p=0.0001) (Table 2). Three of the 4 with an EGFR mutation who did not meet the criteria for response had lesion size changes of −12%, −22% and 24%, respectively. One patient with an EGFR mutation had progression of disease based on size criteria, though the tumor did demonstrate a decrease in central density or near disappearance of the tumor despite a measurable remnant that was larger, a phenomenon previously described in treatment of lung cancer sensitive to an EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor(16).

Table 2.

Correlation of Radiographic Response With EGFR Mutation Status

| Observed results | EGFR exon 19 or 21 mutation | No EGFR mutation in exons 18–24 |

|---|---|---|

| Response (n=21) | 17 | 4 |

| No response (n=29) | 4 | 25 |

Figure 2.

Waterfall response plot after 21 days of gefitinib

There were 10 exon 19 deletions and 10 exon 21 mutations (9 L858R and 1 L861Q mutation), one of these exon 21 mutations was not detected during initial testing but found on subsequent molecular analysis. In addition there 1 was one exon 18 3 base pair deletion. Five tumors were found to have a KRAS mutation (3 with G12C and 2 with G12D), none of these harbored mutations in EGFR exons 18–24. None of the tumors with KRAS mutations met the criteria for response. A tumor that regressed by 74% was found to have mutations in PIK3CA (E542K) and BRAF (V600E). We found no correlation between EGFR protein expression or amplification with response. All five tumors demonstrating EGFR gene amplification harbored EGFR sensitizing mutations. Molecular data and responses are shown Table 3.

Table 3.

Response (Bidimensional & RECIST), mutation status, amplification by CISH, and EGFR protein status by immunohistochemistry and adjuvant gefitinib for each patient

| Mutation | Bi-dimensional | RECIST | CISH | IHC | Adjuvant Gefitinib |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L858R | −75% | −38% | 2.1 | 3 | Yes |

| L858R | −70% | −26% | 2.1 | 0 | Yes |

| L858R | −48% | −27% | 3.4 | 1 | Yes |

| L858R | −41% | −28% | >10 | 3 | Refused |

| L858R | −27% | −9% | 6.8 | 3 | Yes |

| L858R | −25% | −6% | 2.6 | 2 | No |

| L858R | −24% | −6% | 2.2 | 0 | Yes |

| L858R | − 22% | − 0% | 3.9 | 3 | Yes |

| L858R | +14% | +9% | 2.1 | 2 | Yes |

| Exon 19 | −69% | −48% | 5.4 | 1 | Yes |

| Exon 19 | −56% | −32% | 3.2 | 2 | Yes |

| Exon 19 | −54% | −25% | 5.2 | 0 | Yes |

| Exon 19 | −51% | −26% | 2.2 | 2 | Yes |

| Exon 19 | −50% | −25% | 2.4 | 2 | Yes |

| Exon 19 | −47% | −21% | 4.5 | 1 | Yes |

| Exon 19 | −46% | −25% | 2.1 | 1 | Yes |

| Exon 19 | −36% | −29% | 8.1 | 3 | Refused |

| Exon 19 | −39% | −9% | 2.2 | 2 | Yes |

| Exon 19 | −29% | −13% | 2.6 | 2 | Yes |

| Exon 19 | −12% | −0% | 2.2 | 2 | Yes |

| L861Q | −29% | −14% | 2.7 | 2 | Yes |

| Exon 18 – 3 base pair deletion | −10% | −3% | 2.5 | 1 | No |

| PIK3CA (E542K) and BRAF (V600E) | −74% | −63% | 3.8 | 2 | Yes |

| KRAS | −21% | −5% | 2.2 | 0 | No |

| KRAS | −16% | −6% | 2.2 | 0 | 0 |

| KRAS | −8% | −4% | 2.2 | 1 | No |

| KRAS | −8% | −18% | 2.6 | 1 | No |

| KRAS | −24% | −6% | 2.8 | 1 | No |

| Negative | −59% | −39% | 2.1 | 3 | Yes |

| Negative | −43% | −35% | 2.1 | 1 | Yes |

| Negative | −28 | −8% | 2.0 | 1 | Refused |

| Negative | −19% | −19% | 2.5 | 0 | No |

| Negative | −13% | 0% | 2.4 | 2 | No |

| Negative | −12% | +5% | 4.1 | 1 | No |

| Negative | −8% | −3% | 3.8 | 2 | No |

| Negative | −8% | 0% | 2.5 | 1 | No |

| Negative | −7% | −7% | 3.1 | 0 | No |

| Negative | −6% | +13% | 3.1 | 2 | No |

| Negative | −6% | −3% | 2.4 | 0 | No |

| Negative | −3% | −7% | 4.8 | 1 | No |

| Negative | −2% | −2% | Failure | 2 | No |

| Negative | −2% | −2% | 2.2 | 2 | No |

| Negative | 0% | 0% | 2.1 | 0 | No |

| Negative | +6% | 0% | 2.4 | 2 | No |

| Negative | +9% | +3% | 4.7 | 2 | No |

| Negative | +11% | +4% | 3.1 | 2 | No |

| Negative | +16% | +16% | 2.2 | 2 | No |

| Negative | +17% | +9% | 2.3 | 1 | No |

| Negative | +20% | +20% | 2.1 | 2 | No |

| Negative | +26% | +12% | 2.2 | 2 | No |

Follow-up and Survival

The median follow-up was 44.1 months, range 6.9 – 74.8 months. To date, the median progression free survival is not determined in either treatment arm, nor by presence or absence of an EGFR mutation. There are no statistically significant differences between treatment arms. Based on Kaplan-Meier survival proportions, the 2-year disease free survival was 95% (95% CI 70–99%) in the arm that received adjuvant gefitinib versus 78% (95% CI 58–89), in the patients who did not. The 2-year disease free survival for patients with an EGFR mutation was 90% (95% CI 55–87%) versus 75% (95% CI 66–97%) in patients without a mutation. To date, there have only been 2 deaths in the patients with an EGFR mutation and 6 deaths in the patients without a mutation.

Post-operative therapy and gefitinib toxicity

Six of the 50 patients received adjuvant chemotherapy and 1 patient (unresectable) received concurrent chemotherapy and radiation. Disease has progressed in 11 patients and 8 patients have died. Based on the response and mutation data, 25/50 patients were eligible to receive adjuvant gefitinib. 3 patients declined and 1 was determined to have an EGFR mutation on mass spectrometry testing but was not known to be mutant in the postoperative period, therefore 21 were treated. 7 patients later withdrew from study due to minor skin or GI toxicity; 1 withdrew due to cough (n=−1); and one patient due to transaminase elevation (n=1). 2 patients were removed from study due to progressive disease occurring on adjuvant gefitinib. 10 patients have completed the full 2 years of adjuvant gefitinib. Preoperative and postoperative toxicities are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Side effects of pre- and post-operative gefitinib.

| Preoperative Toxicity | Postoperative Toxicity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | |

| Diarrhea | 24/50 | 2/50 | 7/21 | 2/21 | ||

| Rash | 15/50 | 1/50 | 17/21 | 1/21 | ||

| Fatigue | 13/50 | 6/21 | 1/21 | |||

| Mucositis | 3/50 | 3/21 | 1/21 | |||

| Nausea | 1/50 | 1/21 | ||||

| Transaminitis | 1/21 | |||||

During preoperative treatment, toxicities that were at least possibly related to gefitinib included grade 1 rash (24/50) and grade 2 rash (2/50); grade 1 diarrhea (15/50), grade 3 diarrhea (1/50); grade 1 fatigue (13/50); grade 1 nausea (3/50); and grade 1 mucositis (1/50) (Table 5). Only 1 patient did not complete the prescribed preoperative gefitinib course and discontinued treatment due to grade 2 rash.

During adjuvant gefitinib, toxicities included grade 1 rash (17/21); grade 1 diarrhea (7/21), grade 2 diarrhea (2/21); grade 1 fatigue (6/21) and grade 2 fatigue (1/21); and grade 1 mucositis (3/21) and grade 2 mucositis (1/21). One patient had grade 2 transaminase elevation and 1 patient had grade 1 nausea (Table 6). Four of 20 patients were dose reduced to every other day gefitinib due to toxicity: 1 patient with grade 2 mucositis, grade 1 rash, nausea and fatigue who subsequently withdrew consent to continue; one patient with grade 1 rash; 1 patient with grade 1 rash, fatigue and nausea; 1 patient with grade 1 fatigue rash and diarrhea and 1 patient with grade 1 rash and grade 1 mucositis. One patient with grade 3 diarrhea preoperatively was dosed every other day post-operatively and subsequently withdrew consent due to grade 2 transaminase elevation.

Discussion

Within days of the first publications describing the presence of EGFR mutations in patients with tumors sensitive to gefitinib, we designed this phase II trial to prospectively correlate radiographic response rate to gefitinib with the presence of sensitizing EGFR mutations. While technology has since improved and we are now able to test for EGFR mutations with minimal tumor tissue and with increasingly sensitive assays (17), this trial demonstrates feasibility of the concept of enrolling early stage NSCLC patients in a preoperative treatment program that can simultaneously help select treatment for each individual and provide important information about a drug under investigation.

There are two published manuscripts on the use of preoperative gefitinib in a clinical trial setting. Haura, et al. published a series in unselected patients evaluating tumor concentration of gefitinib and effect on signaling pathways downstream of EGFR(18). Lara-Guerra, et al. recently published a trial evaluating preoperative gefitinib in an unselected patient population clinical Stage I NSCLC in which only 6 patients (17%) had EGFR mutations. Of these 6, all had evidence of tumor response to gefitinib but only 3 met criteria for a RECIST partial response after 28 days of therapy(19). Our trial is unique in both its selection of patients with clinical characteristics that correlate with the presence of an EGFR mutation and its use of a modified bi-dimensional response criteria given the short treatment interval.

The first 18 patients enrolled underwent pretreatment tissue sampling for mutation testing by core needle biopsy. Sixteen (89%) had sufficient material for EGFR and KRAS mutations testing. As previously reported, in testing both pre- and post- treatment specimen the concordance was 100%(11). Given these findings, we amended the protocol to perform mutation testing only in the resected specimen. The 100% correlation of EGFR mutation status observed between samples obtained preoperatively by core biopsy with the surgical sample supports the use of core biopsy as a diagnostic tool for EGFR mutation testing in patients with more advanced stage NSCLC where additional surgical material is not likely to be available.

We chose to study patients with Stage I and II NSCLC who were planned to undergo surgical resection, ensuring sufficient tissue for molecular testing. We enriched for likelihood of harboring an EGFR mutation based primarily on smoking history as 41/50 patients enrolled had a ≤ 15 pack year smoking history. The other 9 patients were eligible based on having a component of bronchioloalveolar histology(9, 10). Based on published data we expected 16 mutations in these 41 patients (20). Using our enrichment strategy, 21/50 patients had an EGFR mutation. This supports the need for definitive molecular documentation of a genetic abnormality prior to prescribing a targeted therapy. Despite the use of an enrichment strategy with multiple clinical factors predictive of EGFR mutation to design this trial, our mutation rate was well under 50%, a frequency that would not accurately reflect the activity of a targeted therapy in a therapeutic trial.

We chose prospectively to define response as at least a 25% reduction in bidimensional measurement as response assessment was made after 21 days rather than traditional time point for tumor measurement (2 cycles or 6 to 8 weeks) by RECIST(12, 21). This short “window of opportunity” was based on earlier observations of rapid tumor shrinkages with gefitinib and our desire to proceed to resection as quickly as possible in these patients who were all candidates for curative surgery. The primary statistical endpoint of this study was the difference in the incidence of EGFR mutations in patients with and without response following gefitinib. This study was also used as a platform to evaluate volumetric tumor measurements as has been previously reported in this journal(22).

Using our modified bidimensional response criteria, 81% of patients with an EGFR mutation had a response, whereas only 14% of patients without mutations had a response (p=0.0001). Furthermore, only 14% of patients with an EGFR mutation met criteria for a unidimensional partial response per RECIST 1.0 criteria(21), confirming our suspicion that with a single lesion to assess response, standard response criteria would fail to capture responders. One of these individuals with a response but no EGFR mutation harbors mutations in both PI3K and BRAF, neither of which has been previously associated with gefitinib sensitivity and for which we have no clear explanation. Of the 4 patients with an EGFR mutation and without a response to preoperative gefitinib, only 1 with strict criteria for disease progression had dramatic treatment response in the central part of the primary tumor. The patient did not have evidence of a T790M mutation.

This study assigned adjuvant gefitinib therapy only to the patients who would theoretically benefit from it, namely, those who had radiologic evidence of sensitivity to gefitinib or a known sensitizing mutation, but it was underpowered to detect a survival benefit. As many patients tolerate gefitinib or erlotinib as with or without chemotherapy for years, it was surprising that <50% of patients were able to complete the planned 2-year period of adjuvant therapy. This does bring into question the duration of planned therapy for future adjuvant studies. Preliminary data from the first reported study of adjuvant gefitinib has failed to show a benefit, though the final results are pending(23).

This induction therapy setting in persons with resectable NSCLC provides a unique opportunity for investigation and to help make treatment decisions for individual patients in both the induction and adjuvant settings. Given the 5 year survival is only 61% in patients with clinical Stage 1A and 38% with clinical Stage 1B NSCLC, this approach to identify individuals with objective benefit to neoadjuvant therapy merits consideration for further investigation as a treatment approach for early stage NSCLC patients.

Figure 1.

Flow of patients

Acknowledgments

Supported by NCI R21 CA113653-01 (PI: N. Rizvi) and PO1 CA -05836 (PI: G. Bosl) and an anonymous donor. Gefitinib was provided by AstraZeneca.

References

- 1.Kris M, Natale RB, Herbst R, Lynch T, Jr., Prager D, Belani CP, et al. Efficacy of gefitinib, an inhibitor of the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase, in symptomatic patients with non-small cell lung cancer. JAMA. 2003;290:2149–2158. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.16.2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perez-Soler R, Chachoua A, Huberman M, Karp D, Rigas J, Hammond L, et al. Final results from a phase II study of erlotinib (TarcevaTM) monotherapy in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer following failure of platinum-based chemotherapy. Lung Cancer. 2003;41 Suppl. 2:s246. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller VA, Patel J, Shah N, Kris MG, Tyson L, Pizzo B, et al. The epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor erlotinib (OSI-774) shows promising activity in patients with bronchioalveloar cell carcinoma (BAC): preliminary results of a phase II trial. Proc Amer Soc Clin Onc. 2003 Abstract 2491. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pao W, Miller V, Zakowski M, Doherty J, Politi K, Sarkaria I, et al. EGF receptor gene mutations are common in lung cancers from "never smokers" and are associated with sensitivity of tumors to gefitinib and erlotinib. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:13306–13311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405220101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, Gurubhagavatula S, Okimoto RA, Brannigan BW, et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2129–2139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paez JG, Janne PA, Lee JC, Tracy S, Greulich H, Gabriel S, et al. EGFR Mutations in Lung Cancer: Correlation with Clinical Response to Gefitinib Therapy. Science. 2004;304:1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.1099314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gatzemeier U, Pluzanska A, Szczesna A, Kaukel E, Roubec J, De Rosa F, et al. Phase III study of erlotinib in combination with cisplatin and gemcitabine in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: the Tarceva Lung Cancer Investigation Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1545–1552. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bell DW, Lynch TJ, Haserlat SM, Harris PL, Okimoto RA, Brannigan BW, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations and gene amplification in non-small-cell lung cancer: molecular analysis of the IDEAL/INTACT gefitinib trials. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8081–8092. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.7078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Travis WD, Garg K, Franklin WA, Wistuba II, Sabloff B, Noguchi M, et al. Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma and lung adenocarcinoma: the clinical importance and research relevance of the 2004 World Health Organization pathologic criteria. J Thorac Oncol. 2006;1:S13–S19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller VA, Kris MG, Shah N, Patel J, Azzoli C, Gomez J, et al. Bronchioloalveolar pathologic subtype and smoking history predict sensitivity to gefitinib in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1103–1109. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Solomon SB, Zakowski MF, Pao W, Thornton RH, Ladanyi M, Kris MG, et al. Core needle lung biopsy specimens: adequacy for EGFR and KRAS mutational analysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194:266–269. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.2858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller AB, Hoogstraten B, Staquet M, Winkler A. Reporting results of cancer treatment. Cancer. 1981;47:207–214. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810101)47:1<207::aid-cncr2820470134>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pan Q, Pao W, Ladanyi M. Rapid PCR-based detection of epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations in lung adenocarcinomas. J Mol Diagn. 2005 doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60569-7. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li AR, Chitale D, Riely GJ, Pao W, Miller VA, Zakowski MF, et al. EGFR mutations in lung adenocarcinomas: clinical testing experience and relationship to EGFR gene copy number and immunohistochemical expression. J Mol Diagn. 2008;10:242–248. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2008.070178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas RK, Baker AC, Debiasi RM, Winckler W, Laframboise T, Lin WM, et al. High-throughput oncogene mutation profiling in human cancer. Nat Genet. 2007;39:347–351. doi: 10.1038/ng1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shah NT, Kris MG, Pao W, Tyson LB, Pizzo BM, Heinemann MH, et al. Practical management of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer treated with gefitinib. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:165–174. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smouse JH, Cibas ES, Janne PA, Joshi VA, Zou KH, Lindeman NI. EGFR mutations are detected comparably in cytologic and surgical pathology specimens of nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer Cytopathol. 2009;117:67–72. doi: 10.1002/cncy.20011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haura EB, Sommers E, Song L, Chiappori A, Becker A. A pilot study of preoperative gefitinib for early-stage lung cancer to assess intratumor drug concentration and pathways mediating primary resistance. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:1806–1814. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181f38f70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lara-Guerra H, Waddell TK, Salvarrey MA, Joshua AM, Chung CT, Paul N, et al. Phase II study of preoperative gefitinib in clinical stage I non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6229–6236. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.3370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pham D, Kris MG, Riely GJ, Sarkaria IS, McDonough T, Chuai S, et al. Use of cigarette-smoking history to estimate the likelihood of mutations in epidermal growth factor receptor gene exons 19 and 21 in lung adenocarcinomas. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1700–1704. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.3224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao B, Oxnard GR, Moskowitz CS, Kris MG, Pao W, Guo P, et al. A pilot study of volume measurement as a method of tumor response evaluation to aid biomarker development. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:4647–4653. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goss GD, Lorimer I, Tsao MS, O'Callaghan CJ, Ding K, Masters GA, et al. A phase III randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor gefitinb in completely resected stage IB-IIIA non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): NCIC CTG BR.19. J Clin Oncol (Meeting Abstracts) 2010;28 LBA7005-. [Google Scholar]