Abstract

Many models of trauma-hemorrhagic shock (T/HS) involve the reinfusion of anticoagulated shed blood. Our recent observation that the anticoagulant heparin induces increased mesenteric lymph lipase activity and consequent in vitro endothelial cell cytotoxicity prompted us to investigate the effect of heparin-induced lipase activity on organ injury in vivo as well as the effects of other anticoagulants on mesenteric lymph bioactivity in vitro and in vivo. To investigate this issue, rats subjected to trauma-hemorrhage had their shed blood anticoagulated with heparin, the synthetic anticoagulant arixtra or citrate. Arixtra, in contrast to heparin, did not increased lymph lipase activity or result in high levels of endothelial cytotoxicity. Yet, the arixtra-treated rats subjected to T/HS still manifested lung injury, neutrophil priming and RBC dysfunction, which was totally abrogated by lymph duct ligation. Furthermore, the injection of T/HS mesenteric lymph, but not sham-shock lymph, collected from the arixtra rats into control mice recreated the pattern of lung injury, PMN priming and RBC dysfunction observed after actual shock. Consistent with these observations, citrate anticoagulated rats subjected to T/HS developed lung injury and the injection of mesenteric lymph from the citrate-anticoagulated T/HS rats into control mice also resulted in lung injury. Based on these results, several conclusions can be drawn. First, heparin-induced increased mesenteric lymph lipase activity is not responsible for the in vivo effects of T/HS mesenteric lymph. Secondly, heparin should be avoided as an anticoagulant when studying the biology or composition of mesenteric lymph due to its ability to cause increases in lymph lipase activity that increase the in vitro cytotoxicity of these lymph samples.

Keywords: Mesenteric lymph, shock, hemorrhage, ARDS, MODS

INTRODUCTION

In spite of advances in the care of trauma patients, the development of the multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) after major trauma remains a major cause of mortality and morbidity (1). Our investigations of the pathogenesis of early acute MODS over the last decade has resulted in the hypothesis that mesenteric lymph is a key component linking gut injury to the development of acute MODS after major trauma and shock as well as burn injury (2). This gut lymph hypothesis of acute MODS is supported by 3 major lines of evidence: first, ligation of the main lymph duct exiting the gut prevents acute lung injury, neutrophil priming, cardiac dysfunction, bone marrow suppression, increased endothelial cell activation and RBC dysfunction in various preclinical models, including rat and non-human primate models of trauma-hemorrhagic shock (T/HS), superior mesenteric artery occlusion and burn injury (2); second, mesenteric lymph collected from T/HS animals has major in vitro effects including PMN priming, endothelial cell cytotoxicity and the ability to increase the permeability of endothelial monolayers (2); third, the injection of T/HS, but not trauma sham-shock (T/SS), lymph into naive mice or rats recreates the acute lung injury, RBC dysfunction and PMN priming observed after actual T/HS (2,3,4). However, while investigating the mechanisms and mediators responsible for the biologic activity of T/HS lymph, we discovered that the dose of heparin used to prevent blood clotting of the reinfused shed blood in our experimental T/HS model was sufficient by itself, in the absence of T/HS, to produce lymph highly cytotoxic for human umbilical vein endothelial cells (5). This cytotoxicity of T/HS lymph was directly related to increased lipase activity in the lymph, which was induced by heparin. In follow up to this work, in the current study, we investigated 1) the relative role of heparin in the pathogenesis of T/HS and T/HS lymph-induced MODS, 2) the effect of heparin-induced lipase on organ injury in vivo and 3) the role of lymph in acute T/HS-induced MODS in rats utilizing anticoagulants alternative to native heparin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Adult male specific pathogen-free Sprague-Dawley rats (Taconic Farms, Germantown, NY) weighing 325–450g or C57BL/6 mice weighing 20–30 g (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor Maine) were used in the experiments. Animals underwent a 7-day acclimatization period with 12-hour light/dark cycles under barrier-sustained conditions, during which time they had free access to water and Harlan Teklad laboratory chow (Teklad 22/5 Rodent diet [W] 8640, Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI). The animals were maintained in accordance with the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and all the experiments were approved by the New Jersey Medical School Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Trauma-Hemorrhagic shock (T/HS), lymph duct cannulation and lymph duct ligation (LDL) models

T/HS was induced as previously described (6). Briefly, the rats were anesthetized with intraperitoneal pentobarbital (50mg/kg) following which the femoral artery and jugular veins were cannulated. After the lines were placed, a laparotomy was performed to create tissue injury. Subsequently, the abdomen was closed in two layers. In the animals that were subjected to hemorrhagic shock, the shed blood was withdrawn into a syringe containing heparin (250 U/kg), the synthetic pentastarch anticoagulant arixtra (3mg/kg) or citrate (0.1 ml of 0.109 M citrate per ml of whole blood withdrawn) via the jugular vein catheter until the mean arterial pressure was reduced to 30–40 mmHg. Mean arterial pressure was maintained at this level for 90 min by reinfusing or withdrawing blood as needed. The shed blood was kept at 37°C. At the end of the shock period, the rats were resuscitated with their own shed blood. T/SS rats underwent the same procedure but no blood was withdrawn or infused. The dose of arixtra used was based on dose-response in vitro pilot studies testing the ability of arixtra to prevent clotting of withdrawn blood at room temperature.

To obtain mesenteric lymph for injection into the control mice, separate groups of rats underwent mesenteric lymph duct cannulation followed by T/HS or T/SS, as previously described (6). Specifically, the efferent mesenteric lymph duct draining the majority of the small intestine, cecum, and the proximal one half of the colon was identified and cannulated. The mesenteric lymph from each rat was collected continuously for 3 hrs after T/HS or T/SS into heparin-wetted sterile tuberculin syringes, placed on ice in hourly aliquots. The lymph samples were centrifuged for 15 min at 400g to remove all cellular components and the lymph samples collected from each rat were pooled prior to being stored at −80°C until tested.

In the subgroup of rats that underwent lymph duct ligation, the mesenteric lymph duct was identified, following which it was doubly ligated with 3-0 silk and then divided to prevent the intestinal lymph from reaching the systemic circulation.

Lymph infusion protocol

Male C57BL/6J mice were anesthetized, had jugular vein catheters placed and were subjected to a laparotomy. Pooled T/HS or T/SS mesenteric lymph specimens collected during the post-T/HS or post-T/SS periods were then injected intravenously at a rate of 3.3 µl/gm body weight per hour via the jugular vein catheter for 3h as previously described (3). Thus, each mouse received a total volume of 10 µl of lymph per gm of body weight.

Lung injury assays

3 hours after actual T/HS (T/SS) or the initiation of T/HS (T/SS) lymph injection, the animals were injected with 10 mg (rats) or 1 mg (mice) of Evans Blue dye via an internal jugular vein catheter (7). After 5 minutes (allowing for complete circulation of the dye), a blood sample (1.5 ml in the rat, 0.3 ml in the mouse) was withdrawn from the femoral artery catheter. The blood sample was centrifuged at 1500 rpm at 4°C for 20 minutes, and the resultant plasma was serially diluted to form a standard Evans Blue dye curve. Twenty minutes after injection of the Evans Blue dye, the rats or mice were killed and the lungs harvested. Bronchoalveolar lavage was then performed by lavaging the excised lungs with PBS. In the rats, 5 ml of PBS and in the mice, 1 ml of PBS was instilled into the excised lungs and rinsed in and out three times. To facilitate recovery of the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), a small (1–2 mm) incision is made at the base of the lungs with microscissors. The WBC and RBC count in the recovered BALF was measured using a cell counter (HemaTrue machine; Heska Co.) following which the BALF was centrifuged (1500 rpm for 20 minutes at 4°C) to remove cells, and the supernatant was assayed spectrophotometrically at 620 nm to determine the Evans Blue dye concentration. The concentration of Evans Blue dye in the BALF was plotted on the standard curve, and the percentage relative to that in plasma was determined. The protein content in the BALF was also measured as was the serum protein level.

Neutrophils (PMN) Respiratory burst activity

Neutrophil respiratory burst was performed on rat and mouse neutrophils as described previously (8). Briefly, heparinized whole blood samples collected from rats or mice (100 µL) subjected to various experimental conditions were incubated with dihydrorhodamine (15 ng/mL). Five minutes after the dihydrorhodamine was added, the PMNs were stimulated with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) (270 ng/ml). After an additional 15 mins at 37°C, the PMN respiratory burst was measured by flow cytometry. Data were expressed as mean fluorescence intensities (MFI) of intracellular rhodamine 123.

To assess the in vitro effects of lymph samples collected under various conditions on normal PMNs, whole blood from naïve rats was incubated with medium or the lymph samples (10% v/v) for 5 minutes, following which the samples were treated as above.

RBC Deformability

RBC deformability was determined by laser diffraction analysis using an ektacytometer (LORCA; RR Mechatronics Hoorn, The Netherlands) as previously described (9,10). Briefly, shear stress was applied to RBC samples and the degree of RBC deformability measured. In this system, a laser beam was projected through the sample and the RBC diffraction pattern produced was analyzed by a microcomputer. RBC deformability was assessed by calculating the elongation index (EI) at shear stresses ranging from 0.3 to 30 Pa. From the shear stress elongation curve created above, the data were further analyzed using a double reciprocal plot to determine the overall degree of deformability changes as previously described (11). The calculated Kei is the level of shear stress (in Pascal) that is required for the erythrocytes to reach 50 percent of their maximal elongation. Thus, RBC deformability alterations were assessed by either the elongation index (EI) measured at low shear stress similar to that occurring during low flow conditions in the microcirculation (0.3 Pa) as well as by calculating Kei, which is an indicator of the overall status of RBC deformability. Since EI is a direct measure of RBC deformability, the smaller the number the less deformable are the cells. In contrast, since the Kei is a measure of the amount of stress needed to deform the RBC to half-maximal deformation, an increase in Kei indicates a decrease in RBC deformability.

The in vitro effect of T/HS and T/SS lymph on RBC deformability was tested by incubating whole blood from naïve male rats with the various lymph samples at 37°C for 1 hr at a 5% v/v concentration after which RBC samples were removed and their EI and Kei was measured as described above.

Human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC) monolayer permeability assay

HUVECs were seeded at 2 ×104 cells per insert (0.33 cm2) on type I rat-tailed collagen-coated membranes (pore size 3 µm) contained on the apical chamber of the two chambered Transwell system (Costar, Cambridge, MA). As previously described (6), the HUVECs had formed confluent monolayers at 72 h after seeding. At this time, the monolayers were pre-incubated with medium, 10% T/HS or T/SS lymph for 1 hour, following which a 0.05% solution of the 40kd dextran rhodamine permeability probe (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oregon USA) was added to the apical chamber of the Transwell system. After an additional 3 or 6 hour incubation period, medium in the basal chamber was removed and the amount of dextran rhodamine present was determined spectrophotometrically with excitation and emission wavelengths of 555 and 580 nm. Permeability of the HUVEC monolayers was expressed as dextran-rhodamine clearance (C as nL/cm2/h) according to the following equation:

Fa−b is the flux of the dye probe from the apical to the basolateral compartment (light units/h). [tracer]a is the concentration of Dextran rhodamine in the apical chamber at the beginning of the incubation period, S is the surface area of the monolayer (cm2), and nL equals nanoliters.

HUVEC viability assay

HUVECs were seeded at 2×104 cells per well in 96-well plates (Corning, NY) and were grown for 24 hours. Medium only, or medium containing 10% T/HS or T/SS lymph, were added to each well and the HUVECs were incubated for 3 or 18 hours. At the end of the 3 or 18 hour incubation period, viability was measured using the MTT-based cell cytotoxicity assay kit (Sigma, St. Louis MO). As previously described (6), the medium only MTT value was used as the baseline and expressed as 100% viability. HUVEC viability after exposure to the lymph samples was expressed as a percentage of the viability of medium-treated cells.

Assay of free fatty acids

Lymph and plasma free fatty acids were determined using a NEFA kit from Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd, (Osaka, Japan) according to the protocol supplied by the company.

Assay of serum lipase activity

Serum lipase activity was measured by determining the amount of free fatty acids released from a standard T/SS lymph sample incubated with serum samples. In this assay, T/SS lymph served as the substrate, since it contains significant amounts of fatty acids bound to the triglycerides in chylomicrons. One µl of T/SS lymph was diluted to 25 µl with Krebs-Henseleit buffer Modified (KHBM) (Sigma, Saint Louis, Missouri) and added to each well of a 96 well plate containing 1 µl of serum and 24 µl of KHBM. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 10 min and the reaction was stopped by adding 50 µl of the reagent A of the NEFA kit. Free fatty acid levels were assayed according to the manufacturers protocol. Serum lipase-induced free fatty acid release was corrected for by subtracting the basal level of free fatty acids in the lymph.

Statistics

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the post hoc Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison test or the unpaired Students t-test was used for comparisons between groups based on whether multiple versus two groups were compared. Results are expressed as mean ± SD or SEM. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Heparin increases serum lipase activity but does not cause injury in naive rats

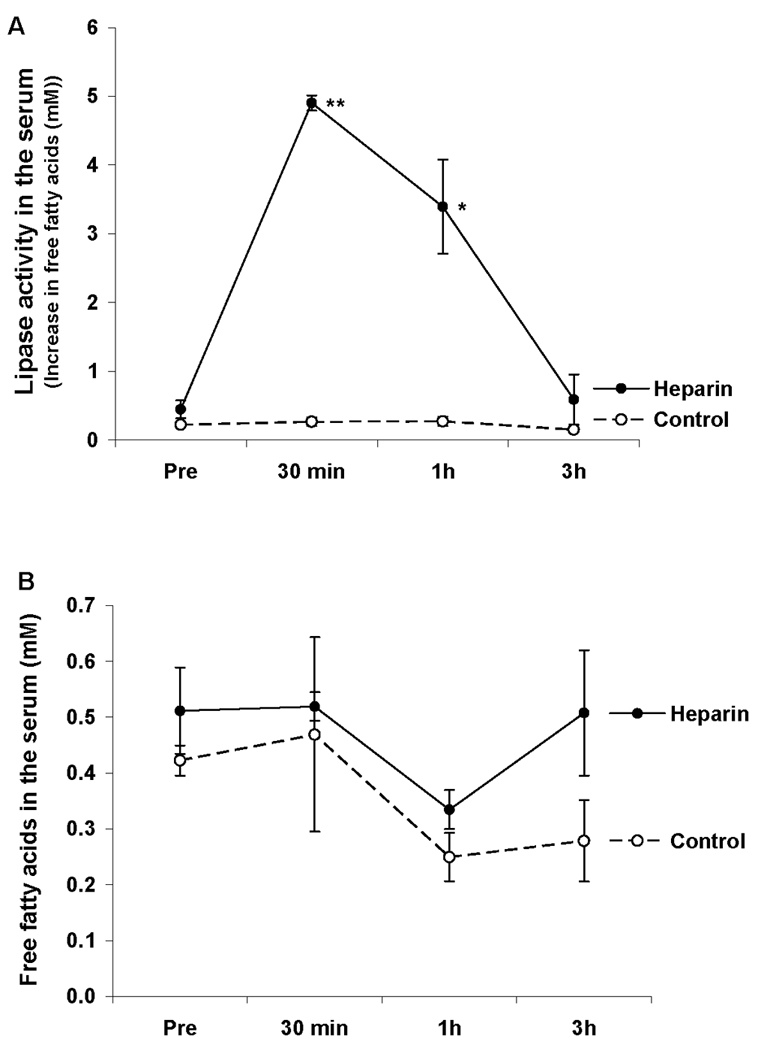

Since the administration of 250 Units/kg of heparin to naive rats led to the generation of lymph that was cytotoxic to HUVECs in vitro (5), our first experiment tested the ability of this dose of heparin to cause injury in vivo. This dose of heparin (250 U/kg) induced a rapid increase in serum lipase activity that peaked at 30 minutes after heparin injection (Figure 1A), yet it was not associated with an increase in serum free fatty acid levels (Figure 1B). Furthermore, this increase in heparin-induced serum lipase did not cause lung injury, RBC dysfunction or neutrophil priming in the control rats (Table 1).

Figure 1.

A: The IV injection of heparin (250 U/kg) led to a rapid increase in serum lipase activity; B: IV heparin did not increase the free fatty acids concentration, in the serum of normal rats. Data expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 4). * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 versus control.

Table 1.

Heparin does not cause lung injury, RBC injury or PMN activation in naive rats.

| Group | Lung Permeability EBD (%) |

BALF WBC/µl |

BALF RBC ×103/µl |

RBC Deformability | PMN Respiratory Burst |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EI | Kei | |||||

| Control | 1.8 ± 0.1% | 17.2 ± 5.7 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 3.1 ± 0.4 | 225 ± 20 |

| Heparin | 2.0 ± 0.6% | 19.1 ± 2.8 | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 2.9 ± 0.5 | 190 ± 28 |

Data expresses as mean ± SD;

n = 4 per group;

BALF = bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; EBD = Evans Blue dye

T/HS causes organ injury and cellular dysfunction in rats anticoagulated with arixtra

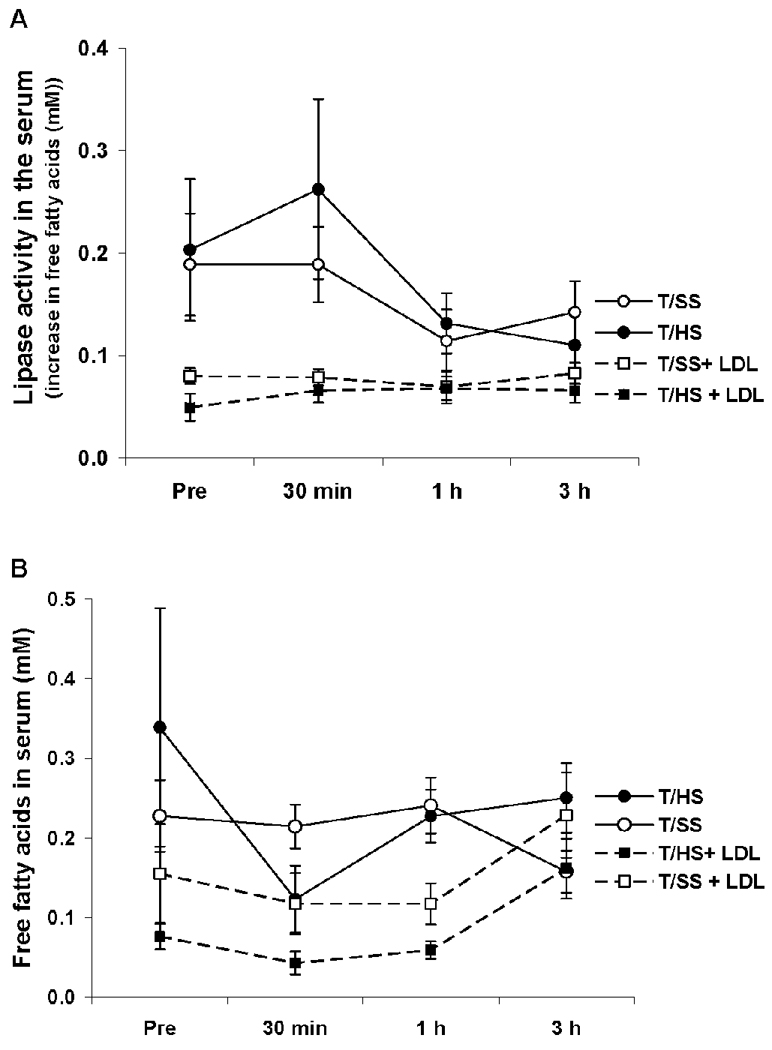

Although heparin did not increase lung injury, RBC dysfunction or prime neutrophils in the control rats, it was still possible that heparin could have contributed to the organ injury in T/HS rats. Thus, we tested the synthetic anticoagulant, arixtra in our T/HS model, since arixtra in contrast to heparin, has been reported not to increase lipoprotein lipase (12). As shown in Figure 2, neither serum lipase activity nor the level of serum free fatty acids were increased after T/HS in the rats infused with arixtra-anticoagulated blood. Although arixtra, in contrast to heparin, was not associated with increased serum lipase activity, the arixtra-treated T/HS rats still manifested evidence of acute lung injury (Table 2), RBC dysfunction and PMN priming (Table 3) when compared to arixtra-treated T/SS controls.

Figure 2.

Serum lipase activity (A) and free fatty acids concentrations (B) were not increased in the serum of arixtra-treated (3mg/kg) rats subjected to T/SS or T/HS with or without lymph duct ligation (LDL). Data expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6–10).

Table 2.

T/HS causes actute lung injury in Arixtra-anticoagulated rats which is prevented by lymph duct ligation (LDL).

| Group | N | BALF EBD (%) |

BALF Plasma Protein ratio |

BALF Protein g/dl |

BALF WBC/µl |

BALF RBC × 103/µl |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T/SS | 9 | 2.6 ± 1.0 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 15 ± 2.4 | 1.5 ± 0.5 |

| T/HS | 10 | 6.3 ± 0.4* | 0.22 ± 0.02+ | 1.1 ± 0.1+ | 25 ± 1.9+ | 2.5 ± 0.4+ |

| T/SS + LDL | 6 | 1.2 ± 0.6 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 15 ± 3.3 | 1.3 ± 0.4 |

| T/HS + LDL | 6 | 3.2 ± 0.9 | 0.12 ± 0.03 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 16 ± 4.4 | 1.8 ± 0.5 |

Data expressed as mean ± SD;

p < 0.05 vs other groups;

p < 0.001 vs other groups;

BALF = bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; EBD = Evans Blue dye

Table 3.

T/HS decreased RBC deformability and increased PMN activation in arixtra-anticoagulated rats which is prevented by lymph duct ligation (LDL)

| Group | N | RBC Deformability | PMN Respiratory Burst |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBC EI | RBC Kei | |||

| T/SS | 6 | 0.56 ± 0.002 | 3.2 ± 0.7 | 236 ± 15 |

| T/HS | 6 | 0.41 ± 0.002+ | 10 ± 1.2* | 404 ± 44+ |

| T/SS + LDL | 4 | 0.56 ± 0.003 | 4.0 ± 0.6 | 224 ± 9 |

| T/HS + LDL | 4 | 0.52 ± 0.004 | 5.8 ± 2.8 | 279 ± 29 |

Data expressed as mean ± SD;

p < 0.05 vs all other groups;

p < 0.001 vs all other groups;

EI = Elongation Index; Kei = mean stress to half-maximally deform RBC

To validate the observation made in heparin-treated rats that mesenteric lymph duct ligation abrogated T/HS-induced lung injury, RBC dysfunction and PMN priming, we repeated this experiment in arixtra-treated rats. Mesenteric lymph duct ligation (LDL) prevented T/HS-induced acute lung injury (Table 2), RBC dysfunction and PMN activation (Table 3). Additionally, the arixtra-treated T/HS and T/SS rats subjected to LDL did not show any increases in serum lipase activity or free fatty acid levels (Figure 2). Thus, LDL was as effective in limiting T/HS-induced lung injury, RBC dysfunction and PMN activation in the arixtra-treated rats as was previously observed in heparin-treated rats (2).

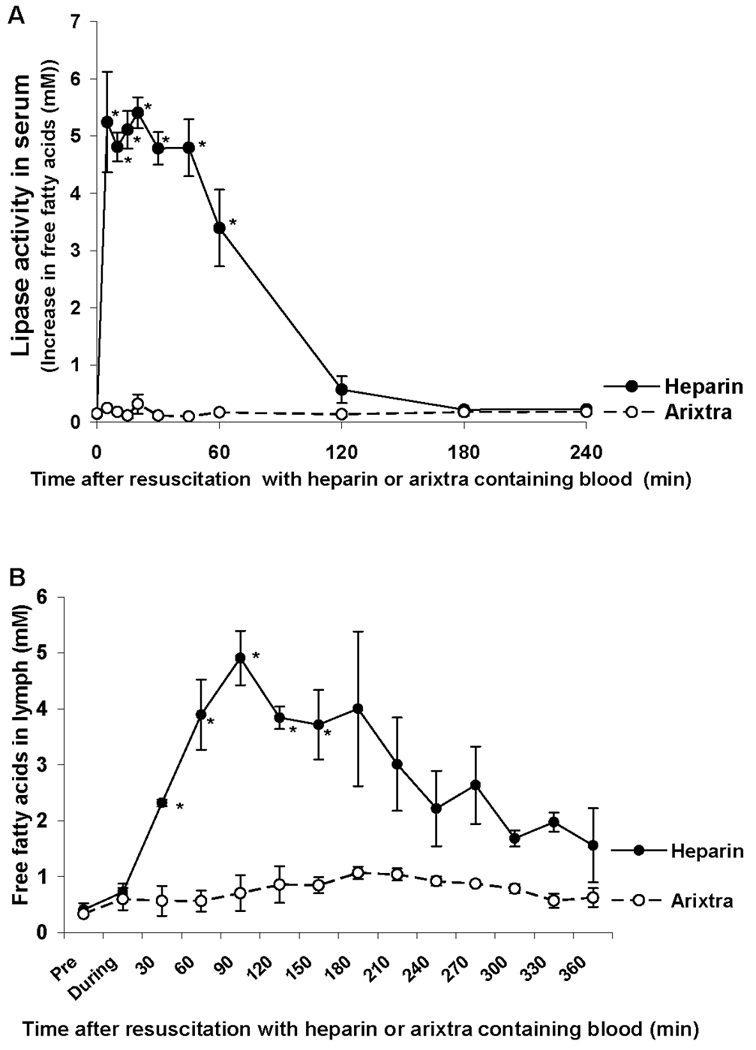

T/HS lymph from heparin-anticoagulated but not arixtra anticoagulated rats had increased lymph lipase and free fatty acids levels

Next, we characterized the effects of arixtra versus heparin anticoagulation on T/HS lymph lipase activity and free fatty acid levels. Heparin, but not arixtra, anticoagulation was associated with an early and rapid increase in serum lipase activity that began shortly after the shed blood was returned to the animals and persisted for greater than 1 hr after volume resuscitation (Figure 3A). This increase in serum lipase activity was associated with a significant increase in lymph free fatty acid levels in the T/HS heparin but not the arixtra group (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

T/HS lymph lipase activity was increased in the heparin, but not the arixtra anticoagulated rats (A) as were free fatty acid concentrations (B). Data expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 3). * P < 0.05 versus arixtra.

T/HS lymph from arixtra-treated rats recreated the pattern of organ injury and cellular dysfunction observed after actual T/HS

Since our previous work has documented that the injection of T/HS lymph from heparin-anticoagulated rats into control rats and mice is sufficient to recreate the effects of actual T/HS in terms of lung injury (3), we repeated these studies using T/HS lymph collected from arixtra-anticoagulated rats. The intravenous injection of T/HS but not T/SS lymph from the arixtra-anticoagulated rats caused lung injury in naive mice (Table 4) as well as RBC dysfunction and PMN priming (Table 5). Since the T/HS lymph samples from the arixtra-treated rats did not have increased lipase activity or elevated free fatty acid levels and were able to recreate the lung injury, RBC dysfunction and PMN activation states observed after actual T/HS, it appears that elevated levels of lipase activity or free fatty acids are not necessary for the adverse systemic effects of T/HS lymph.

Table 4.

Injection of T/HS lymph from Arixtra-anticoagulated rats causes lung injury in naïve mice

| Group | BALF EBD (%) |

BALF Plasma Protein Ratio |

BALF Protein g/dl |

BALF WBC/µl |

BALF RBC × 103/µl |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T/SS Lymph | 3.2 ± 0.5 | 0.1 ± 0.3 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 17 ± 11 | 1.5 ± 0.6 |

| T/HS Lymph | 9.0 ± 2.2* | 0.2 ± 0.03* | 0.8 ± 0.1* | 81 ± 2* | 7.6 ± 5.5* |

Data expressed as mean ± SD;

n = 5 per group;

p < 0.01 vs other groups

Table 5.

Injection of T/HS lymph from Arixtra-anticoagulated rats decreases RBC deformability and activated PMNs in naïve mice

| Group | RBC Deformability | PMN Respiratory Burst |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| RBC EI | RBC Kei | ||

| T/SS Lymph | 0.063 ± 0.005 | 2.8 ± 1.0 | 221 ± 18 |

| T/HS Lymph | 0.052 ± 0.004* | 4.6 ± 0.7* | 315 ± 66* |

Data expressed as mean ± SD;

n = 9 per group;

p < 0.01 vs other groups

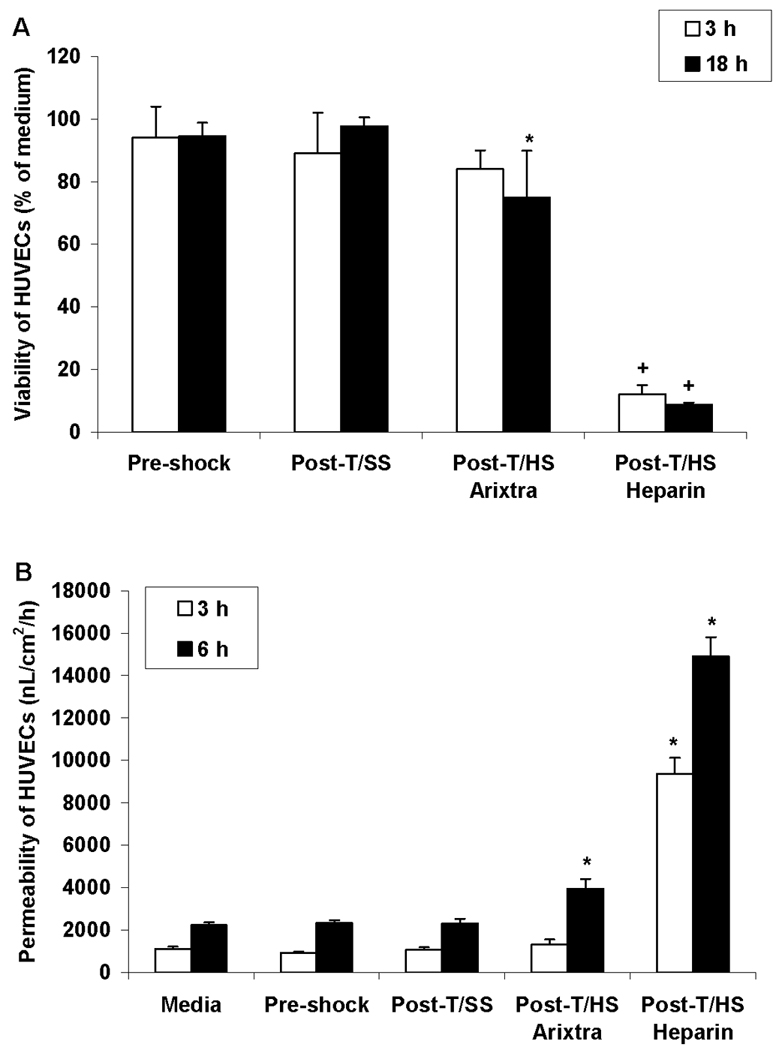

Comparison of in vitro activities of T/HS lymph collected from heparin or arixtra-treated rats

Having shown that T/HS lymph from the arixtra-anticoagulated rats does not have increased lipase activity or contain increased levels of free fatty acids, yet was still able to recreate the in vivo deleterious effects on organ and cellular injury when injected into naive mice, we next examined the in vitro activity of T/HS lymph from the arixtra-anticoagulated rats in endothelial cell, RBC and PMN assays. As previously reported (6), T/HS lymph from heparin-anticoagulated rats exhibited a high level of HUVEC cytotoxicity (~ 90% cell death) after a 3 hr incubation period (Figure 4A). However, although the arixtra T/HS lymph did cause HUVEC cell death, it required an 18 hr incubation period for this to occur and the magnitude of cytotoxicity was much less than that observed with heparin T/HS lymph (Figure 4A). Since the heparin T/HS lymph samples have significant direct cytotoxic effects, it is not surprising that HUVEC monolayer permeability was rapidly and greatly increased after incubation with heparin T/HS lymph (Figure 4B). The arixtra T/HS lymph samples were also able to increase HUVEC monolayer permeability after a 6 but not a 3 hr incubation period and the effect was less than that observed for heparin T/HS lymph (Figure 4B). The in vitro effects of the T/HS arixtra lymph on RBC deformability and PMN priming mimicked what was observed in vivo, with the T/HS, but not the T/SS, lymph samples impairing RBC deformability and priming PMN for an augmented respiratory burst (Table 6). Furthermore, the magnitude of the effects of the T/HS arixtra samples were similar to that previously reported for the heparin T/HS lymph samples (4,13). Thus, it appears that the in vitro biologic effect of T/HS lymph on HUVEC viability and permeability is greater in the lymph samples collected from the heparin than from the arixtra anticoagulated rats. However, the in vitro RBC and PMN modulating effects of the T/HS lymph from the heparin and arixtra anticoagulated rats were similar.

Figure 4.

A) Effects of a 3 or 18 hr incubation period with T/SS or T/HS lymph from arixtra or heparin anticoagulated rats on human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC) viability. Data expressed as mean ± SD with n= 5–6 samples per group. * p < 0.05 versus T/SS or pre-shock lymph and + p < 0.01 versus all other groups; B) Effect of T/SS or T/HS lymph from arixtra or heparin anticoagulated rats on HUVEC monolayer permeability. Data expressed as mean ± SD with n= 4–7 samples per group. * p < 0.01 versus all other groups.

Table 6.

In vitro incubation of naïve rat blood with T/HS lymph from Arixtra-anticoagulated rats impairs RBC deformability and activates PMN

| Group | RBC Deformability | PMN Respiratory Burst |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| RBC EI | RBC Kei | ||

| T/SS Lymph | 0.063 ± 0.002 | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 222 ± 11 |

| T/HS Lymph | 0.044 ± 0 .01* | 4.4 ± 0.9* | 307 ± 13* |

Data expressed as mean ± SD;

n = 4–6 lymph samples per group;

p<0.01 vs T/SS Lymph

T/HS-induced lung injury occured in rats receiving citrate as an anticoagulant

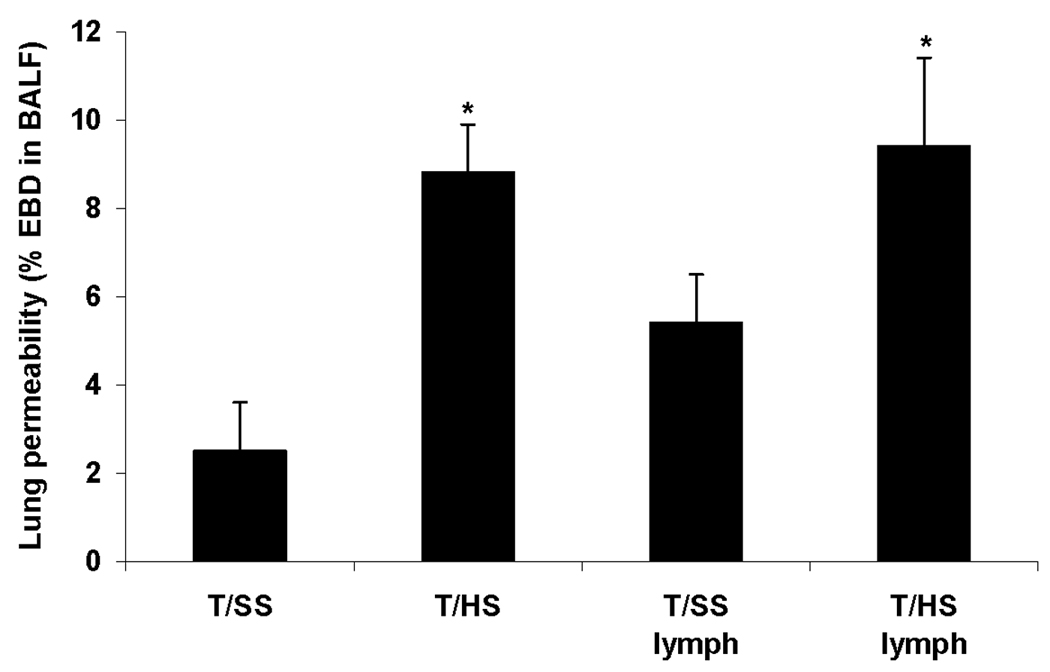

To further validate the arixtra T/HS data, we tested the effect of citrate anticoagulation on T/HS-induced lung injury since citrate does not increase lymph lipase activity (5) or increase lymph free fatty acid levels (data not shown). However, one limitation of using citrate as an anticoagulant is that it has been reported to interfere with PMN activation studies due to its calcium-chelating activities (14). Similar to our previously published studies using heparin as an anticoagulant as well as the current arixtra studies, citrate-anticoagulated rats subjected to T/HS developed lung injury and the injection of citrate T/HS lymph into naive mice resulted in lung injury (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

T/HS causes lung injury in rats anticoagulated with citrate while injection of naive rats with T/HS but not T/SS lymph from citrate anticoagulated rats causes lung injury. Data expressed as mean ± SD with n= 4–6 animals per group. * p < 0.01 versus comparable T/SS group. EBD: Evans Blue dye

DISCUSSION

Because of the importance of MODS as a continuing cause of morbidity and mortality in severely injured trauma patients as well as other ICU populations (1), we and others have focused on elucidating the pathogenesis of this syndrome (2,15). Work carried over the last decade in preclinical models by us (2,6,7) and subsequently by the laboratory of Dr E. E. Moore (16,17) have implicated intestinal mesenteric lymph as the source of gut-derived factors contributing to acute MODS. Although the exact identity of the factors in intestinal lymph responsible for its deleterious in vivo effects remain to be fully determined, in vitro studies have shown that these effects are not related to cytokines, endotoxins or other putative mediators in lymph, but instead have implicated both protein and lipid moieties as being important in this process (18–21). As a result of our investigations into the lipid species responsible for the endothelial cell injurious effects of T/HS lymph, we recently found that the heparin used in our T/HS model, rather than the actual T/HS insult, was primarily responsible for the endothelial cell cytotoxic properties of the T/HS lymph samples (5). Specifically, although the rats subjected to T/HS were not directly anticoagulated, several aspects of the shock protocol results in the rats receiving anticoagulated blood. First, the reservoir into which the shed blood was withdrawn contained low doses of heparin to prevent the shed blood from clotting resulting in the shed blood being anticoagulated. Since it is necessary to re-infuse aliquots of the shed blood during the 90 minute shock period to maintain a stable mean arterial blood pressure of 30–40 mm Hg, the animals will receive some anticoagulated blood. In addition, the implanted catheters require anticoagulant coating to promote blood flow. Lastly, at the end of the shock period, the animals were resuscitated by re-infusing the remaining shed blood. Thus, the rats received a dose of heparin equivalent to approximately 250 U/kg body weight. However, based on the literature, it appears that the effect of the administration of heparinized anticoagulated blood at the end of the shock period would be beneficial, since Chaudry’s laboratory in a series of studies showed that pre-heparinization ameliorated some of the physiologic consequences of trauma-hemorrhage (22,23). These results by Chaudry are consistent with a body of literature indicating that heparin has significant anti-inflammatory effects (24). However, none of these studies investigated the effects of heparin on the biologic activity of intestinal lymph. Consequently, the observation that heparin directly results in the intestinal lymph, of even naive rats, becoming cytotoxic for endothelial cells (5) led us to believe that it was critical to re-examine our lymph gut hypothesis of acute MODS. In this context, the current results show that although heparin increases the in vitro endothelial cell cytotoxicity of lymph in T/SS rats (5), it has no measurable in vivo deleterious effects on lung permeability, RBC deformability or neutrophil priming.

A second major conclusion from the current study is that T/HS lymph was still a critical factor in the induction of acute MODS when non-heparin anticoagulants were employed. This conclusion is based on the following observations in studies using arixtra or citrate as anticoagulants. First, lung injury, RBC dysfunction and neutrophil priming were observed in rats subjected to T/HS receiving arixtra to prevent clotting of the shed blood. Secondly, this observation that arixtra-treated rats subjected to T/HS still had lung injury was replicated using citrate as an anticoagulant. Additionally, lymph duct ligation was fully protective in the arixtra-treated T/HS rats and, lastly, the in vivo injection of T/HS, but not T/SS lymph from arixtra-treated rats into normal mice recreated the pattern of injury observed after actual T/HS shock. Taken together these results support the concept that, while heparin anticoagulation results in T/HS lymph having an in vitro cytotoxic activity, this heparin-induced property of T/HS lymph is not responsible for the ability of T/HS lymph to cause lung injury in vivo. This concept is further supported by the fact that neither the arixtra nor citrate-anticoagulated rats developed an increase in lymph lipase activity or free fatty acid levels as was observed in the heparin-anticoagulated rats.

The observation that heparin administration can result in the generation of increased plasma free fatty acids through heparin’s ability to increase lipoprotein lipase has been described (25). Furthermore, it has been reported that under certain circumstances lipolytically-released free fatty acids manifest cytotoxic properties (26) as well as increase endothelial permeability (27). Although little attention has been focused on intestinal lymph, our current and previous studies (5) indicating that heparin can result in intestinal lymph from normal animals becoming cytotoxic for endothelial cells as well as increasing endothelial cell monolayer permeability is consistent with plasma and serum studies. The dose of heparin required to induce the observed endothelial cytotoxic effects of mesenteric lymph was in the range of 75–100 U/Kg of heparin (unpublished data).Even though heparin’s lipolytic-inducing effects did not cause damage in vivo, this observation is important when studying T/HS for two major reasons. First, the use of heparin results in non-T/HS-induced changes in the biologic activity of T/HS lymph thereby resulting in potentially confounding information on the pathogenesis of early MODS. Secondly, the heparin-induced changes in the lipid species of T/HS lymph will confound isolation and identification studies focusing on the key factors in T/HS lymph that contribute to gut-origin MODS. Since, in contrast to heparin, the synthetic anticoagulant arixtra does not increase lipoprotein lipase or result in the generation of highly cytotoxic lymph when administered to naive rats or rats subjected to T/HS, the use of arixtra should avoid the confounding effects of heparin in future studies investigating the role of mesenteric lymph in the pathogenesis of acute MODS.

In summary, most models of hemorrhagic shock involves the reinfusion of at least some of the anticoagulated shed blood and all require anticoagulated catheters to ensure blood flow. Since we have recently observed that heparin-induced lymph lipase activity was responsible for the endothelial cytotoxic properties of mesenteric lymph, we were prompted to examine the effects of different anticoagulants on the systemic effects of T/HS as well as the in vivo and in vitro effects of T/HS lymph. While validating the gut lymph hypothesis of early MODS, these studies urge caution in the use of heparin as an anticoagulant in hemorrhagic shock studies, especially those investigating the biology or composition of T/HS mesenteric lymph.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH Grants: GM 059841 and T32 069330

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dewar D, Moore FA, Moore EE, Balogh Z. Postinjury multiple organ failure. Injury. 2009;40:912–918. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2009.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deitch EA, Xu DZ, Lu Q. Gut lymph hypothesis of early shock and trauma-induced multiple organ dysfunction syndrome: A new look at gut origin sepsis. J Organ Dys. 2006;2:70–79. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Senthil M, Watkins A, Barlos D, Xu DZ, Lu Q, Abungo B, Caputo F, Feinman R, Deitch EA. Intravenous injection of trauma hemorrhagic shock mesenteric lymph causes lung injury that is dependent upon activation of the inducible nitric oxide synthase pathway. Ann Surg. 2007;246:822–830. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3180caa3af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Condon M, Senthil M, Xu DZ, Mason L, Sheth SU, Spolarics Z, Feketeova E, Machiedo GW, Deitch EA. Intravenous injection of mesenteric lymph produced during hemorrhagic shock decreases RBC deformability in the rat. J Trauma. 2011;70:489–495. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31820329d8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qin Y, Prescott LM, Deitch EA, Kaiser VL. Heparin use in a trauma-hemorrhagic shock model induces biologic activity in rat mesenteric lymph. Shock. 2011;35:411–421. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31820239ee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deitch EA, Adams CA, Lu Q, Xu DZ. A time course of the protective effects of mesenteric lymph duct ligation on hemorrhagic shock-induced pulmonary injury and the toxic effects of lymph from shocked rats on endothelial cell monolayer permeability. Surgery. 2001;129:39–47. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.109119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Magnotti LJ, Upperman JS, Xu DZ, Lu Q, Deitch EA. Gut-derived mesenteric lymph but not portal blood increases endothelial cell permeability and promotes lung injury after hemorrhagic shock. Ann Surg. 1998;228:518–527. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199810000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deitch EA, Shi HP, Lu Q, Feketeova E, Skurnick J, Xu DZ. Mesenteric lymph from burned rats induces endothelial cell injury and activates neutrophils. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:533–538. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000109773.00644.F4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zaets SB, Berezina TL, Caruso J, Xu DZ, Deitch EA, Machiedo GW. Mesenteric lymph duct ligation prevents shock-induced RBC deformability and shape changes. J Surg Res. 2003;109:51–56. doi: 10.1016/s0022-4804(02)00024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zaets SB, Berezina TL, Morgan C, Kamiyama M, Spolarics Z, Xu DZ, Deitch EA, Machiedo GW. Effect of trauma-hemorrhagic shock on red blood cell deformability and shape. Shock. 2003;19:268–273. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200303000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Condon mR, Kim E, Siddiqi M, Deitch EA, Machiedo GW, Spolarics Z. Appearance of an erythrocyte population with decreased deformability and hemoglobin content following sepsis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H2177–H2184. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01069.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffman P, Bernat A, Dumas A, Petitou M, Herault JP, Herbert JM. The synthetic pentastarch SR90107A/ORG 3150 does not release lipase activity into the plasma. Thrombosis Res. 1997;86:325–332. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(97)00075-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caruso JM, Feketeova E, Dayal SD, Hauser CJ, Deitch EA. Factors in intestinal lymph after shock increase neutrophil adhesion molecule expression and pulmonary leukosequestration. J Trauma. 2003;55:727–733. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000037410.85492.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pfister RR, Haddox JL, Dodson RW, Deshozo WF. Polymorphonuclear leukocyte inhibition by citrate, other metal chelators and trifluoperazine. Invest Opthalmol Vis Sci. 1984;25:955–970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fink MP, Delude RL. Epithelial barrier dysfunction: a unifying theme to explain the pathogenesis of multiple organ dysfunction at the cellular level. Crit Care Clin. 2005;21:177–196. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zallen G, Moore EE, Johnson JL, Tamura DY, Ciesla DJ, Silliman CC. Posthemorrhagic shock mesenteric lymph primes circulating neutrophils and provokes lung injury. J Surg Res. 1999;83:83–88. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1999.5569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jordan JR, Moore EE, Sarin EL, Damle SS, Kashik SB, Silliman CC, Banerjee A. Arachidonic acid in post-shock mesenteric lymph induces pulmonary synthesis of leukotriene B4. J Appl Physiol. 2008;104:1161–1166. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00022.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaiser VL, Sifri ZC, Dikdan GS, Berezina T, Zaets S, Lu Q, Xu DZ, Deitch EA. Trauma-hemorrhagic shock mesenteric lymph from rat contains a modified form of albumin that is implicated in endothelial cell toxicity. Shock. 2005;23:417–425. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000160524.14235.6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davidson MT, Deitch EA, Lu Q, Osband A, Feketeova E, Nemeth ZH, Hasko G, Xu DZ. A study of the biologic activity of trauma-hemorrhagic shock mesenteric lymph over time and the relative role of cytokines. Surgery. 2004;136:32–41. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2003.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sarin EL, Moore EE, Moore JB, Masuno T, Moore JL, Banerjee A, Silliman CC. Systemic neutrophil priming by lipid mediators in post-shock mesenteric lymph exists across species. J Trauma. 2004;57:950–954. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000149493.95859.6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pelz ED, Moore EE, Zurawel AA, Jordan JR, Damle SS, Redzic JS, Masuno T, Eun J, Hansen KC, Banerjee A. Proteome and systemic ontology of hemorrhagic shock: Exploring early constitutive changes in postshock mesenteric lymph. Surgery. 2009;146:347–357. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang P, Singh G, Rana MW, Ba ZF, Chaudry IH. Preheparinization improves organ function after trauma and hemorrhage. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:R645–R650. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1990.259.3.R645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rana MW, Singh G, Wang P, Ayala A, Zhou M, Chaudry IH. Protective effects of preheparinization on the microvasculature during and after hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma. 1992;32:420–426. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199204000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Young E. The anti-inflammatory effects of heparin and related compounds. Thrombosis Res. 2008;122:743–752. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2006.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goodfriend TL, Pedersen TL, Grekin RJ, Hammock BD, Ball DL, Vollmer A. Heparin, lipoproteins and oxygenated fatty acids in blood: A cautionary note. Prostgland Leuko Fatty Acids. 2007;77:363–366. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chung BH, Hennig B, Cho BHS, Darnell BE. Effect of the fat composition of a single meal on the composition and cytotoxic potencies of lipolytically-releasable free fatty acids in postprandial plasma. Atherosclerosis. 1998;141:321–332. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(98)00168-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eiselein L, Wilson DW, Lame MW, Rutledge JC. Lipolysis products from triglyceride-rich lipoproteins increase endothelial permeability, perturb zona occludens-1 and F-actin and induce apoptosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H2745–H2753. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00686.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]