Abstract

Purpose: Partial scan reconstruction (PSR) artifacts are present in myocardial perfusion imaging using dynamic multidetector computed tomography (MDCT). PSR artifacts appear as temporal CT number variations due to inconsistencies in the angular data range used to reconstruct images and compromise the quantitative value of myocardial perfusion when using MDCT. The purpose of this work is to present and evaluate a technique termed targeted spatial frequency filtration (TSFF) to reduce CT number variations due to PSR when applied to myocardial perfusion imaging using MDCT.

Methods: The TSFF algorithm requires acquiring enough X-ray projections to reconstruct both partial (π + fan angle α) and full (2π) scans. Then, using spatial linear filters, the TSFF-corrected image data are created by superimposing the low spatial frequency content of the full scan reconstruction (containing no PSR artifacts, but having low spatial resolution and worse temporal resolution) with the high spatial frequency content of the partial scan reconstruction (containing high spatial frequencies and better temporal resolution). The TSFF method was evaluated both in a static anthropomorphic thoracic phantom and using an in vivo porcine model and compared with a previously validated reference standard technique that avoids PSR artifacts by pacing the animal heart in synchrony with the gantry rotation. CT number variations were quantified by measuring the range and standard deviation of CT numbers in selected regions of interest (ROIs) over time. Myocardial perfusion parameters such as blood volume (BV), mean transit time (MTT), and blood flow (BF) were quantified and compared in the in vivo study.

Results: Phantom experiments demonstrated that TSFF reduced PSR artifacts by as much as tenfold, depending on the location of the ROI. For the in vivo experiments, the TSFF-corrected data showed two- to threefold decrease in CT number variations. Also, after TSFF, the perfusion parameters had an average difference of 13.1% (range 4.5%–25.6%) relative to the reference method, in contrast to an average difference of 31.8% (range 0.3%–54.0%) between the non-TSFF processed data with the reference method.

Conclusions: TSFF demonstrated consistent reduction in CT number variations due to PSR using controlled phantom and in vivo experiments. TSFF-corrected data provided quantitative measures of perfusion (BV, MTT, and BF) with better agreement to a reference method compared to noncorrected data. Practical implementation of TSFF is expected to incur in an additional radiation exposure of 14%, when tube current is modulated to 20% of its maximum, to complete the needed full scan reconstruction.

Keywords: computed tomography, myocardial perfusion, functional imaging, partial scan reconstruction artifacts, linear filters

INTRODUCTION

Quantitative myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI) using multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) remains challenging due to demands in temporal resolution. Early work in MPI made use of the electron beam CT (EBCT)1, 2 and the dynamic spatial reconstructor (DSR).3, 4 EBCT provided a temporal resolution in the range of 50–100 ms; by magnetically steering an electron beam around a 210° stationary tungsten target, hence, by its design, the EBCT ensured that the partial scans always covered a consistent angular range.5 Through the advent of faster gantry rotations in MDCT scanners, it became possible to scan the beating heart.6 With dual source CT, it is possible to obtain a temporal resolution of 75 ms,7, 8 similar to that of the EBCT.

Initial experiences in animal models demonstrated the feasibility to perform MPI using MDCT,9, 10, 11 although with some limitations. Mahnken et al.9 showed that infarcted areas detected by MDCT correlated well with cardiac MR perfusion and histology, but quantitative estimations differed significantly between imaging modalities. George et al.10 used a canine model and found good blood flow (BF) correlation with microspheres-based estimates, although initial experiments did not use ECG-gated acquisition and the temporal resolution was limited to 400 ms. Daghini et al.,11 using a porcine model, compared both EBCT and single source MDCT and found that the latter was affected by CT number fluctuations, which were suggested to be due to partial scan reconstructions (PSR). Using Patlak analysis, however, good agreement was found between EBCT and MDCT.

Using prospectively gated acquisitions in MDCT, it is not possible to guarantee that the angular data range, corresponding to a specific anatomic location and phase in the cardiac cycle, consistently uses the same angular source positions, as in the EBCT. Hence, variations in beam hardening and scatter as a function of source position leads to artifactual variations in CT numbers, since different angular ranges are covered from one partial scan to another.12 Such fluctuations, different from statistical noise, compromise the quantitative value of MPI with CT and have been characterized as PSR artifacts. Primak et al. demonstrated in animal studies that when the gantry rotation was synchronized with an animal’s heart rate driven by a pacing device, guaranteeing consistent angular data ranges for each phase of the cardiac cycle (such as in EBCT), PSR artifacts were avoided.12 While the technique effectively avoided PSR artifacts, its invasiveness precludes clinical use. Meinel et al.13 proposed a correction using a full scan to correct subsequently acquired partial scans. Stenner et al.14 extended this idea by creating an artificial full scan and a virtual partial scan, both of which were used to correct the original partial scans reconstructions. This method did not require a priori information as in Ref. 13 and proved to be very effective to reduce PSR artifacts in a stationary phantom and an ex vivo kidney perfusion model. The approach has not been validated or compared to a reference standard in vivo, although preliminary observations were reported in one case.15

Here, we present a method, named targeted spatial frequency filtration (TSFF), which requires acquiring enough X-ray projections to reconstruct both a partial and a full scan. The TSFF uses the low spatial frequency information of a full scan reconstruction and combines it with the high spatial frequency information of a partial scan reconstruction. This general approach was first presented in Refs. 16, 17. In this work, we describe the method and our specific implementation in detail and demonstrate the effectiveness of the TSFF using a stationary anthropomorphic phantom and in vivo animal experiments. Furthermore, we compare the results of the TSFF correction with acquisitions in which the animal’s heart was paced in synchrony with the gantry rotation, guaranteeing consistent angular ranges for each partial scan.12

METHODS

Targeted spatial frequency filtration

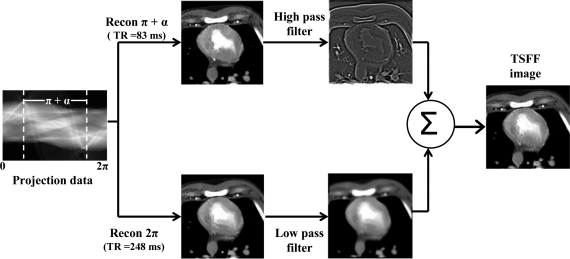

TSFF requires that a full scan, hence 2π of projection data, be collected around the desired phase of the cardiac cycle where the images are to be reconstructed. Images reconstructed using 2π of data, I2π, do not contain the PSR artifacts. However, they are subject to greater amounts of motion artifacts due to heart motion as well as passage of the transient bolus of contrast agent (Fig. 1). Images acquired using partial scans, requiring only π + fan angle α of projection data, Iπ+α, have improved temporal resolution18 but worse CT number accuracy due to PSR artifacts (Fig. 1). TSFF uses both of these reconstructed images at a selected cardiac phase (e.g., 65% of the RR interval) and convolves them with a linear, zero-phase filter to separate low and high spatial frequencies. For this purpose, we used a transfer function h corresponding to a bidimensional binomial filter.19 The low spatial frequency information of the images using full scan reconstructions is combined with the high spatial frequency information of the images reconstructed with partial scans. Hence, the TSFF images, ITSFF, combine the more accurate CT number information from the full scan reconstructions with the improved temporal resolution of the partial scan reconstructions. Formally, this can be expressed as

| (1) |

where ⊗ corresponds to the convolution operation, and hLP and hHP are complementary low and high pass filter transfer functions, respectively. The coefficients for the one-dimensional N-point transfer function h are given by

| (2) |

where and N: odd. The order N controls the cutoff frequency of the filter. The equivalent two-dimensional binomial filter transfer function h(n1,n2) was obtained using a McClellan frequency transformation.

Figure 1.

Scheme explaining the targeted spatial frequency filtration algorithm. TR = temporal resolution.

Data acquisition

Phantom validation

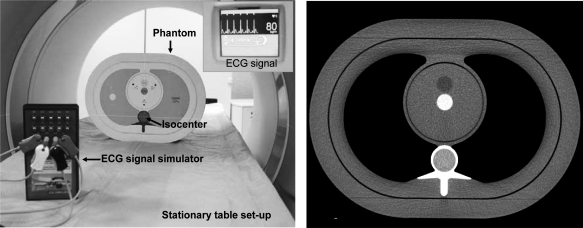

An anthropomorphic thorax phantom (QRM, Möhrendorf, Germany) with the cardiac calcium insert was scanned using a dual-source MDCT scanner (Somatom Definition, Siemens Healthcare, Forchheim, Germany). The phantom was placed 5 cm off isocenter in the vertical direction (Fig. 2) with the purpose of exacerbating PSR artifacts, as shown in Ref. 12. Two different scan protocols were used to obtain full and partial scan reconstructions with and without TSFF correction (Table Table I.). The tube current–time product (mAs) was adjusted to obtain approximately the same image noise for the full and partial scans.

Figure 2.

(a) Scanning setup for phantom validation and (b) sample image of scanned phantom.

Table 1.

Phantom scans protocols.

| Full scans | TSFF scans | |

|---|---|---|

| kVp | 120 | 120 |

| mAs/rot | 125 | 300 |

| Collimation (mm) | 24 × 1.2 | 24 × 1.2 |

| Automatic exposure control | Off | Off |

| Simulated ECG | No | Yes |

| Scan duration (s) | 24.0 | 25.2 |

| Cycle time (s) | 0.75 | 0.75 |

| Temporal resolution (ms) | 330 | 83–248aa |

| Special acquisition setup | No | Yes |

Dual source cardiac reconstruction with 83 ms temporal resolution (¼ of a rotation), from which the high spatial frequency information was obtained, and a dual source full scan reconstruction with 248 ms temporal resolution (¾ of a rotation), from which the low spatial frequency information was obtained.

The TSFF algorithm requires 2π of projection data acquired in a cardiac dual source mode; the ECG signal must be recorded with the projection data for appropriate reconstruction, and this acquisition must occur with a stationary table. A scanning mode meeting these criteria was not available on the scanner used in this work. Hence, we used a free-standing stationary tabletop and the manufacturer-provided cardiac dual source acquisition protocol (Fig. 2). An ECG signal generator was set up at 80 bpm and connected to the CT scanner ECG leads. Data were acquired using a spiral coronary CT angiogram protocol. The phantom was held stationary on the free-standing tabletop, which was isolated from the scanner’s moving patient table. The recorded projection data were equivalent to what would have been acquired using a dual source cardiac perfusion scan protocol, if such had been available, and included default scatter and beam hardening corrections. Offline image reconstruction was performed using an in house, previously validated fan beam filtered backprojection algorithm.20 Partial scan reconstructions were performed using the method of projection weighting as described by Parker18 and a dual source reconstruction approach.21, 22 Reconstructed image width was 4.8 mm, corresponding to projections from the central detector rows, to avoid potential cone beam artifacts from the outer rows.

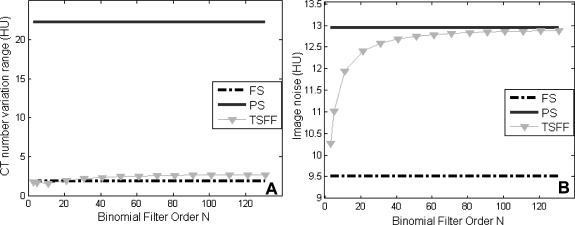

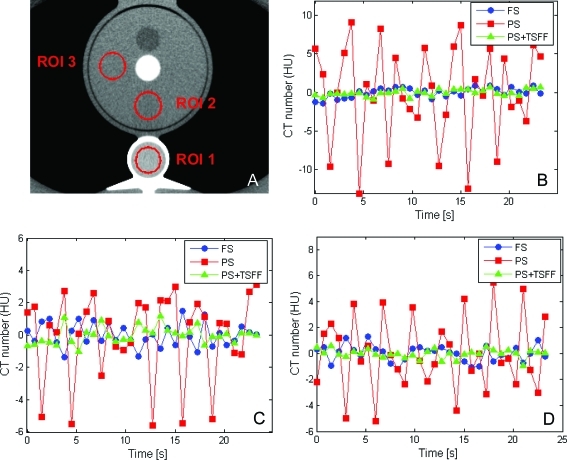

To assess the effect of the binomial filter order, which controls the spatial frequency cutoff, on the PSR artifact reduction and image noise, we varied the filter order from N = 3 to 141. Image noise was measured as the standard deviation of CT numbers in uniform regions of interest (ROIs). Temporal CT number variations were assessed in three ROIs within the phantom for each condition (Fig. 3). PSR artifacts were quantified using the CT number range (maximum CT number–minimum CT number) and standard deviation of the PSR artifacts over all time points for each ROI.

Figure 3.

Effect of the TSFF spatial linear filter order N on (a) CT number variation range and (b) image noise. FS = full scan, PS = partial scan, TSFF = targeted spatial frequency filtration scan. CT number variation range was determined as the difference between the maximum and minimum CT numbers.

Animal experiments

Preparation

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved this study. An 86 kg female pig was intubated with an intramuscular injection (Telazol, 2.2 mg/kg; Ketamine, 2.2 mg/kg; Xylazine, 2.2 mg/kg) and mechanically ventilated with room air. Anesthesia was maintained on a cocktail drip of ketamine 2 mg/kg/l, amidate 0.08 mg/kg/l, and fentanyl 0.02 mg/kg/l in a 5% dextrose solution at 100–140 ml/h. A pigtail catheter was advanced through the jugular sheath into the superior vena cava for contrast injection. Before each perfusion scan, the animal was hyperventilated. Ventilation was suspended for 40 s during scanning to minimize spontaneous respiratory thoracic motion.

Synchronization of animal heart with gantry rotation

The animal’s heart rate was synchronized with the gantry rotation (at 90.9 bpm), as described in Ref. 12, such that the angular positions of the X-ray tubes were consistent across heartbeats. A gantry synchronization signal was generated by adding an infrared light source and detector to the gantry. A signal was generated once per rotation and used to trigger an ECG input signal for the CT scanner and for triggering a pacing catheter, which was placed in the animal’s coronary sinus.

Animal scanning

The animal was scanned under two pacing conditions: one with and one without synchronizing the heart rate with gantry rotation, which we will refer as locked and unlocked conditions, respectively. For each pacing condition, the pig was scanned under two physiological conditions: rest and stress. Pharmacological stress was induced by selective infusion of adenosine into the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery, using 100 μg/kg/min dosage, initiated 5 min prior to scanning. Heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate were recorded. The CT scan parameters were similar to TSFF scans performed with the phantom (Table Table I.).

Contrast injection

Nonionic, iodinated contrast (Omnipaque 350 mgI/ml, GE Healthcare, Princeton, NJ) was injected at 10 ml/s and 800 PSI, 0.3 ml/kg, using an automated power injector (Medrad Inc, Indianola, PA). Contrast was injected 5 s after scanning started for the locked condition and 15 s after scanning for the unlocked condition. All scans were performed on the same day, with at least 15 min between scans to allow for clearance of contrast media from the myocardium.

Perfusion estimation

Time–attenuation curves (TACs) were generated for an ROI in the left ventricular chamber CLV(t) and myocardium CM(t). A section of myocardium was selected within the territory perfused by the LAD. Curves were fitted with a dual gamma variate model using least squares minimization, resulting in two curves, separating the intravascular and extravascular components from the myocardial TAC. Using the fitted curves, fractional blood volume (BV), mean transit time (MTT) corrected by the appearance time t0, and BF in milliliter per gram per minute, were calculated, as previously described.4, 23

Data analysis

To evaluate the effectiveness of TSFF in reducing CT number variability in vivo, we evaluated the first 15–20 s of the myocardial TAC, which corresponded to the time prior to contrast appearing in the myocardium. Paired comparisons were performed for identical scan data from the unlocked acquisition, both with and without the TSFF correction. The range and standard deviation of CT number variations were used to quantify the fluctuation in CT numbers prior to contrast enhancement.

Additionally, we compared quantitative perfusion parameters (BV, MTT, and BF) between the reference scan (locked condition) and the unlocked scan, both with and without TSFF correction.

RESULTS

Phantom experiments

Spatial frequency cutoff of the TSFF

A broad range of choices for the binomial filter N (3–131) reduced the CT number variations substantially, with little dependency on the value of N (Fig. 3a). As expected, the image noise of the TSFF image depended on N, being bounded between the image noise level of the partial and full scan reconstructions of the TSFF acquisition (Fig. 3b). A large N, which corresponds to using a lower spatial frequency cutoff, leaves the TSFF image noise closer to that of the partial scan image (Fig. 3b). To minimize potential motion blurring coming from the full scans, which had poorer temporal resolution, we used a higher binomial filter order of N = 101, corresponding to a roll off at 6% of the maximum spatial frequency.

PSR artifact reduction

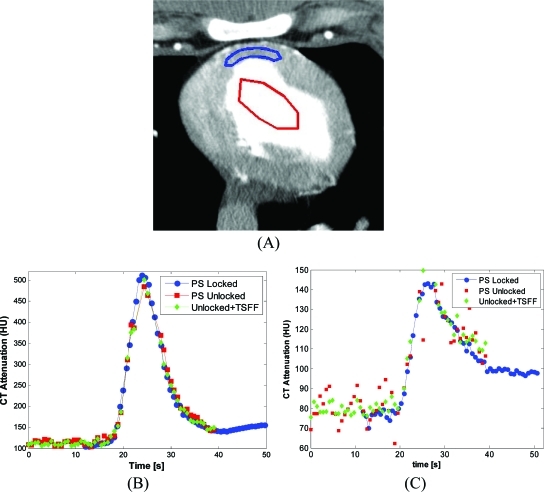

Analysis of selected ROIs in the static anthropomorphic phantom revealed larger CT number variations through time in each ROI for the partial scans relative to the full scans, which were dependent on ROI location (Fig. 4). When the PSR artifacts were quantitated with CT number range, we found variations up to 22.3, 2.9, and 2.2 HU for partial scans, full scans, and TSFF corrected partial scans, respectively. A similar trend was observed when variations were quantified with the standard deviation (Table Table II.).

Figure 4.

Temporal CT number variations in full scans (FS), partial scans (PS), and partial scans processed with targeted spatial frequency filtration (PS + TSFF). Three ROIs were evaluated (a). Temporal CT number variations are shown for ROI 1 (b), ROI 2 (c), and ROI 3 (d).

Table 2.

Quantitative assessment of CT number variations in the phantom study before and after the use of TSFF.

| CT number range (HU) | Standard deviation of PSR artifacts (HU) | Noise (HU) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | FS | PS | PS + TSFF | FS | PS | PS + TSFF | FS | PS | PS + TSFF |

| ROI 1 | 2.3 | 22.3 | 1.6 | 0.6 | 6.3 | 0.4 | 12.4 | 12.9 | 12.1 |

| ROI 2 | 2.9 | 8.7 | 2.2 | 0.7 | 2.7 | 0.5 | 12.1 | 12.3 | 11.8 |

| ROI 3 | 2.2 | 10.6 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 2.9 | 0.3 | 11.5 | 12.5 | 11.4 |

Animal experiments

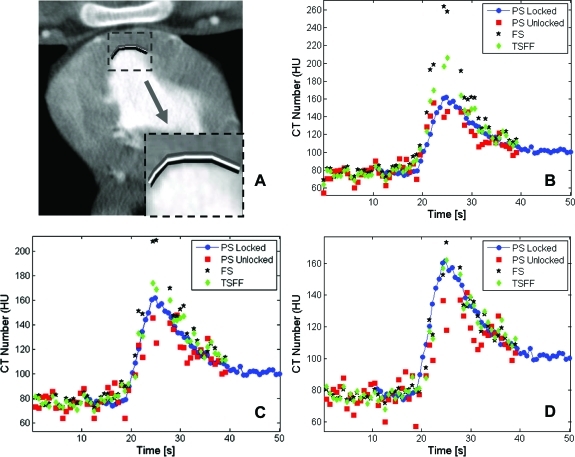

During scanning, the animal’s heart was paced at 86 and 90.9 bpm during the unlocked and locked conditions, respectively. TACs for the locked condition, as well as for the unlocked condition with and without TSFF correction demonstrated larger CT number variations for the unlocked condition without correction (Fig. 5). Over the first 15–20 s, before contrast arrival to myocardium, the maximum CT number variations were up to 35.2 and 11.9 HU for the uncorrected and TSFF corrected data, respectively (Table Table III.). Quantitative perfusion parameter estimates such as BV, MTT, and BF had better agreement after TSFF filtration (Table Table IV.).

Figure 5.

Regions of interest (ROIs) and time–attenuation curves (TACs). (a) Selected ROIs in left ventricular (LV) chamber and left anterior descending (LAD) supplied territory of the myocardium. TACs comparing the reference method (PS locked), partial scan (PS unlocked), and corrected partial scan (Unlocked + TSFF) are shown for the LV (b) and the LAD territory (c). The TACs correspond to the scan 5 min after injection of adenosine.

Table 3.

Quantitative assessment of CT number variations in vivo during the unenhanced period of the TACs. All measurements were done in the ROIs traced in the myocardial territory of the LAD coronary artery.

| CT number range (HU) | Standard deviation of PSR artifacts (HU) | Noise (HU) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physiological condition | PS | PS + TSFF | PS | PS + TSFF | PS | PS + TSFF |

| Rest | 35.2 | 11.9 | 7.7 | 2.9 | 13.6 | 13.2 |

| Adenosine stress | 32.0 | 10.5 | 7.6 | 2.7 | 13.8 | 13.4 |

Table 4.

Comparison of perfusion parameter calculation.

| Rest | Stress | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perfusion parameter | PS unlocked | TSFF unlocked | PS locked | PS unlocked | TSFF unlocked | PS locked |

| BV (relative) | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.20 |

| MTT (s) | 8.72 | 13.85 | 11.02 | 8.64 | 7.66 | 8.61 |

| BF (ml/g/min) | 0.49 | 0.77 | 0.92 | 1.08 | 1.59 | 1.71 |

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated in phantoms and in vivo that TSFF can reduce PSR artifacts. In our phantom experiment, CT number variations over time were approximately ten times larger for partial scan images compared to full scan images, even when the magnitude of the image noise was matched (Table Table II.). TSFF reduced CT number variations over time to the level of full scans (Fig. 4).

For the in vivo scans, TSFF consistently reduced the CT number variability over time in myocardium (Fig. 5). CT number variations for the noncontrast enhanced portion of the unlocked scans were reduced by about a factor of 3 using TSFF correction (Table Table III.). Quantitative estimates of perfusion (BV, MTT, and BF) showed better agreement between the locked and unlocked scans after TSFF correction (Table Table IV.). The average difference in perfusion parameters between the locked and unlocked conditions was 31.8% (range 0.3%–54.0%) prior to correction and 13.1% (range 4.5%–25.6%) after TSFF correction.

Previously published, noninvasive methods to reduce PSR artifacts did not include comparisons to a reference standard or in vivo validation.13, 14 Recent animal experiments,24 using a commercial implementation of PSR artifact reduction similar to that presented in Refs. 16, 17, demonstrated sufficient accuracy in quantitative perfusion measures to differentiate the perfusion values at rest and stress with statistical significance.

We believe the work described here is the first description of an in vivo validation of this approach relative to a reference standard having no PSR artifacts. It is also the first to investigate the tradeoff between artifact reduction, image noise, and filter order.

Practical implementation

Relative to a partial scan acquisition, TSFF requires a longer X-ray exposure to acquired sufficient data to reconstruct a full scan. Using a fan angle of 50° and taking into account the dual source CT image reconstruction approach,25 the excess exposure to produce dual source full scans is about 70%, assuming the tube current is kept constant throughout the acquisition. If the tube current is reduced for the additional projections required to complete a full scan reconstruction, for example, to 20% as in ECG-based tube current modulation in coronary CT angiography technique,26 the additional exposure required to perform TSFF is only 14%. A dedicated tube current modulation scheme, as the one described above, was implemented in the second generation of the dual source CT scanner (Definition Flash, Siemens Healthcare, Forchheim, Germany)17 and has been successfully used in patient MPI studies.27, 28, 29

Limitations and future work

In this study, we did not assess the impact of TSFF on temporal resolution. While the premise that the high spatial frequency portions of the data should preserve edge information is reasonable, there could be a blurring effect in low spatial frequency portions of the data due to cardiac motion that is expected to be more pronounced with heart rates (Fig. 6). Future work is needed to quantitate the effect of TSFF algorithm on temporal resolution and the subsequent impact on spatial resolution. While the full and TSFF scan images can provide similar perfusion estimates for areas not severely affected by motion, the TSFF provides superior performance for those areas closer to endocardial borders or coronary vessels. When we traced small ROIs, only two to three voxels thick, with similar contours in close proximity to endocardial borders (Fig. 7), it can be appreciated that the TSFF images provide more stable estimations of the TAC, when comparing them to the TAC from the reference standard image data (locked condition). When the ROI is directly adjacent to the endocardium, the motion artifact in the full scan results in an overestimation of the peak CT number of the TAC (Fig. 7b) relative to the partial and TSFF scan images. Because the TSFF image carries with it some of the contents of the full scan image, it also overestimates the peak of the TAC, but not as strongly. As the narrow ROIs are moved away from the endocardial border, this effect lessens; the full scan image still results in an overestimation of the peak of the TAC, but not as severely. Thus, as long as the selected ROIs include fewer voxels at the endocardial border, the full scan images provide sufficient estimates of TACs. However, especially for thinned myocardium subsequent to disease, this is not always possible. In these cases, the use of partial scan images with higher temporal resolution images is needed. However, the PSR artifacts cause variations in CT number that degrades the TAC (Figs. 7c, 7d). The TSFF images correct this variation without overestimating the peak of the TAC and are thus preferred.

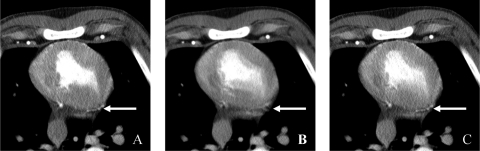

Figure 6.

Impact of TSFF in temporal resolution in an animal with a heart rate of 86 bpm. (a) Partial scan acquisition with 83 ms temporal resolution. (b) Full scan reconstruction with 248 ms temporal resolution. (c) TSFF-corrected image using the high spatial frequency portion of (a) and the low spatial frequency portion of (b). The TSFF used a linear binomial filter with order N = 101. Arrow indicates a vessel that becomes discontinuous and blurry at 248 ms temporal resolution (b), but that remains sharp after TSFF correction (c).

Figure 7.

Tradeoff between PSR artifacts and motion artifacts at (a) three adjacent and thin ROIs with similar contours close to the endocardial border, (b) TACs from innermost ROI (in black), (c) TACs from medium ROI (in white), and (d) TACs from outermost ROI (in gray). ROIs are two to three voxels thick. The TACs correspond to the scan 5 min after injection of adenosine.

We anticipate the TSFF images to be advantageous for small ROI image analysis30 and for the visualization of myocardial perfusion maps29 since they inherit the higher temporal resolution properties from the partial scans; hence, it is less affected by motion artifacts compared to a full scan. Qualitative, only minor motion artifacts were observed in the animal TSFF images even at heart rates of approximately 90 bpm. While technically the TSFF can be applied to conventional single-source CT approaches, further investigation is deserved, since one can expect a higher susceptibility to cardiac motion artifacts with more limited temporal resolution, as evidenced in previous studies.11

This study was limited to one animal. However, it demonstrated a viable PSR artifact correction method in vivo and to directly compare the results of the correction to a reference standard. Future studies are underway to evaluate the accuracy of the technique in a larger sample size. In patient studies, we expect shorter breath hold times of about 30 s and aided with breath monitoring systems used to allow subjects to monitor and maintain their own breath.31 Additionally, quantitative MPI requires minimization of artifacts including beam hardening,32, 33 which we did not address in this study.

Future work will assess lower tube potential values (e.g., 80 or 100 kV)34 and lower tube current approaches, anticipating that noise reduction and iterative reconstruction strategies35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42 can be used to lower the dose, potentially increasing the utilization of CT MPI in clinical practice.

CONCLUSION

TSFF demonstrated consistent reduction in temporal CT number variations due to PSR artifacts, both in a stationary thorax phantom and in vivo in an animal model. TSFF correction provided considerably better agreement with a reference standard for quantitative measures of perfusion (BV, MTT, and BF) compared to noncorrected images. Practical implementation of TSFF is expected to incur in an additional radiation exposure of 14%, when the tube current is modulated to 20% of its maximum to complete the full scan reconstruction. We expect this radiation dose increase can be overcome by using lower tube potential settings as well as noise reduction techniques. The reported preliminary experience indicates the TSFF technique should be useful for human applications.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Kristina Nunez for assistance in manuscript submission and Dr. Rainer Raupach and Dr. Andrew Primak for their contributions to the development of this approach. This work was supported in part by the American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowship No. 10PRE2560028, NIH Grant No. R01EB07986 from National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and by the NIH Opus CT Imaging Resource Construction Grant No. R018898.

References

- Lipton M. J., Higgins C. B., Farmer D., and Boyd D. P., “Cardiac imaging with a high-speed Cine-CT Scanner: Preliminary results,” Radiology 152, 579–582 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman L. O., Siripornpitak S., Maffei N. L., P. F.Sheedy, II, and Ritman E. L., “Measurement of in vivo myocardial microcirculatory function with electron beam CT,” J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 23, 390–398 (1999). 10.1097/00004728-199905000-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robb R. A. and Ritman E. L., “High-speed synchronous volume computer tomography of the heart,” Radiology 133, 655–661 (1979). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T., Wu X., Chung N., and Erik L. R., “Myocardial blood flow estimated by synchronous, multislice, high-speed computed tomography,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 8, 70–77 (1989). 10.1109/42.20364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCollough C. H. and Morin R. L., “The technical design and performance of ultrafast computed tomography,” Radiol. Clin. North Am. 32, 521–536 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann M. H., Shi H., Schmitz B., Schmid F. T., Lieberknecht M., Schulze R., Ludwig B., Kroschel U., Jahnke N., Haerer W., Brambs H. J., and Aschoff A. J., “Noninvasive coronary angiography with multislice computed tomography,” JAMA 293, 2471–2478 (2005). 10.1001/jama.293.20.2471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flohr T. G., McCollough C. H., Bruder H., Petersilka M., Gruber K., Suss C., Grasruck M., Stierstorfer K., Krauss B., Raupach R., Primak A. N., Kuttner A., Achenbach S., Becker C., Kopp A., and Ohnesorge B. M., “First performance evaluation of a dual-source CT (DSCT) system,” Eur. Radiol. 16, 256–268 (2006). 10.1007/s00330-005-2919-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flohr T. G., Leng S., Yu L., Aiimendinger T., Bruder H., Petersilka M., Eusemann C. D., Stierstorfer K., Schmidt B., and McCollough C. H., “Dual-source spiral CT with pitch up to 3.2 and 75 ms temporal resolution: Image reconstruction and assessment of image quality,” Med. Phys. 36, 5641–5653 (2009). 10.1118/1.3259739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahnken A., Bruners P., Katoh M., Wildberger J., Günther R., and Buecker A., “Dynamic multi-section CT imaging in acute myocardial infarction: Preliminary animal experience,” Eur. Radiol. 16, 746–752 (2006). 10.1007/s00330-005-0057-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George R. T., Jerosch-Herold M., Silva C., Kitagawa K., Bluemke D. A., Lima J. A. C., and Lardo A. C., “Quantification of myocardial perfusion using dynamic 64-detector computed tomography,” Invest. Radiol. 42, 815–822 (2007). 10.1097/RLI.0b013e318124a884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daghini E., Primak A. N., Chade A. R., Zhu X., Ritman E. L., McCollough C. H., and Lerman L. O., “Evaluation of porcine myocardial microvascular permeability and fractional vascular volume using 64-slice helical computed tomography (CT),” Invest. Radiol. 42, 274–282 (2007). 10.1097/01.rli.0000258086.78179.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primak A. N., Dong Y., Dzyubak O. P., Jorgensen S. M., McCollough C. H., and Ritman E. L., “A technical solution to avoid partial scan artifacts in cardiac MDCT,” Med. Phys. 34, 4726–4737 (2007). 10.1118/1.2805476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinel J. A., Hoffman E., Clough A., and Wang G., “Reduction of half-scan shading artifact based on full-scan correction,” Acad. Radiol. 13, 55–62 (2006). 10.1016/j.acra.2005.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenner P., Schmidt B., Bruder H., Allmendinger T., Haberland U., Flohr T., and Kachelriess M., “Partial scan artifact reduction (PSAR) for the assessment of cardiac perfusion in dynamic phase-correlated CT,” Med. Phys. 36, 5683–5694 (2009). 10.1118/1.3259734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenner P., Schmidt B., Bruder H., Flohr T., and Kachelriess M., “Partial scan artifact reduction (PSAR) for the assessment of cardiac perfusion in dynamic phase-correlated CT,” Nuclear Science Symposium Conference Record, 2008, NSS’08 (IEEE, Dresden, Germany,2008), pp. 5203–5209. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Primak A. N., Raupach R., Yu L., Flohr T. G., and McCollough C. H., “A novel approach to reduce partial scan artifacts in cardiac multi-detector row CT (MDCT),” Annual Meeting of the Radiological Society of North America, p.1051, RSNA, Chicago, Illinois (2008).

- Raupach R., Bruder H., Schmidt B., Klotz E., and Flohr T. G., “A novel spatiotemporal filter for artifact and noise reduction in CT,” Eur. Congr. Radiol. No. SS 1013, B-518 A (2009).

- Parker D. L., “Optimal short scan convolution reconstruction for fan beam CT,” Med. Phys. 9, 254–257 (1982). 10.1118/1.595078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubury M. and Luk W., “Binomial filters,” J. VLSI Signal Proc. Syst. Signal, Image, Video Technol. 12, 35–50 (1996). 10.1007/BF00936945 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Primak A. N., Ramirez Giraldo J. C., Liu X., Yu L., and McCollough C. H., “Improved dual-energy material discrimination for dual-source CT by means of additional spectral filtration,” Med. Phys. 36, 1359–1369 (2009). 10.1118/1.3083567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flohr T. G., Stierstorfer K., Ulzheimer S., Bruder H., Primak A. N., and McCollough C. H., “Image reconstruction and image quality evaluation for a 64-slice CT scanner with z-flying focal spot,” Med. Phys. 32, 2536–2547 (2005). 10.1118/1.1949787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flohr T. G., Bruder H., Stierstorfer K., Petersilka M., Schmidt B., and McCollough C. H., “Image reconstruction and image quality evaluation for a dual source CT scanner,” Med. Phys. 35, 5882–5897 (2008). 10.1118/1.3020756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohlenkamp S., Behrenbeck T. R., Lerman A., Lerman L. O., Pankratz V. S., Sheedy P. F., 2nd, Weaver A. L., and Ritman E. L., “Coronary microvascular functional reserve: Quantification of long-term changes with electron-beam CT preliminary results in a porcine model,” Radiology 221, 229–236 (2001). 10.1148/radiol.2211001004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahnken A. H., Klotz E., Pietsch H., Schmidt B., Allmendinger T., Haberland U., Kalender W. A., and Flohr T., “Quantitative whole heart stress perfusion CT imaging as noninvasive assessment of hemodynamics in coronary artery stenosis: Preliminary animal experience,” Invest. Radiol. 45, 298–305 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCollough C. H., Primak A. N., Saba O., Bruder H., Stierstorfer K., Raupach R., Suess C., Schmidt B., Ohnesorge B. M., and Flohr T. G., “Dose performance of a 64-channel dual-source CT scanner,” Radiology 243, 775–784 (2007). 10.1148/radiol.2433061165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobs T. F., Becker C. R., Ohnesorge B., Flohr T., Suess C., Schoepf U. J., and Reiser M. F., “Multislice helical CT of the heart with retrospective ECG gating: Reduction of radiation exposure by ECG-controlled tube current modulation,” Eur. Radiol. 12, 1081–1086 (2002). 10.1007/s00330-001-1278-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho K.-T., Chua K.-C., Klotz E., and Panknin C., “Stress and rest dynamic myocardial perfusion imaging by evaluation of complete time-attenuation curves with dual-source CT,” J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. Imaging 3, 811–820 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastarrika G., Ramos-Duran L., Rosenblum M. A., Kang D. K., Rowe G. W., and Schoepf U. J., “Adenosine-stress dynamic myocardial CT perfusion imaging: Initial clinical experience,” Invest. Radiol. 45, 306–313 (2010). 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3181c4f535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamberg F., Becker A., Schwarz F., Marcus R. P., Greif M., von Ziegler F., Blankstein R., Hoffmann U., Sommer W. H., Hoffmann V. S., Johnson T. R. C., Becker H. -C. R., Wintersperger B. J., Reiser M. F., and Nikolaou K., “Detection of hemodynamically significant coronary artery stenosis: Incremental diagnostic value of dynamic CT-based myocardial perfusion imaging,” Radiology 260, 689–698 (2011). 10.1148/radiol.11110638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritman E. L., “Temporospatial heterogeneity of myocardial perfusion and blood volume in the porcine heart wall,” Ann. Biomed. Eng. 26, 519–525 (1998). 10.1114/1.98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson S. K., Felmlee J. P., Bender C. E., Ehman R. L., Classic K. L., Hoskin T. L., Harmsen W. S., and Hu H. H., “CT fluoroscopy–guided biopsy of the lung or upper abdomen with a breath-hold monitoring and feedback system: A prospective randomized controlled clinical trial,” Radiology 237, 701–708 (2005). 10.1148/radiol.2372041323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenner P., Schmidt B., Allmendinger T., Flohr T., and Kachelrie M., “Dynamic iterative beam hardening correction (DIBHC) in myocardial perfusion imaging using contrast-enhanced computed tomography,” Invest. Radiol. 45, 314–323 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa K., George R. T., Arbab-Zadeh A., Lima J. A. C., and Lardo A. C., “Characterization and correction of beam-hardening artifacts during dynamic volume CT assessment of myocardial perfusion,” Radiology 256, 111–118 (2010). 10.1148/radiol.10091399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L., Li H., Fletcher J. G., and McCollough C. H., “Automatic selection of tube potential for radiation dose reduction in CT: A general strategy,” Med. Phys. 37, 234–243 (2010). 10.1118/1.3264614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Primak A. N., Krier J. D., Yu L., Lerman L. O., and McCollough C. H., “Renal perfusion and hemodynamics: Accurate in vivo determination at Ct with a 10-fold decrease in radiation dose and HYPR noise reduction,” Radiology 253, 98–105 (2009). 10.1148/radiol.2531081677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruder H., Raupach R., Klotz E., Stierstorfer K., and Flohr T., “Spatio-temporal filtration of dynamic CT data using diffusion filters,” Proc. SPIE 7258, 725857 (2009). 10.1117/12.811085 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manduca A., Yu L., Trzasko J., D., Khaylova N., Kofler J. M., McCollough C., and Fletcher J. G., “Projection space denoising with bilateral filtering and CT noise modeling for dose reduction in CT,” Med. Phys. 36, 4911–4919 (2009). 10.1118/1.3232004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibault J. B., Sauer K. D., Bouman C. A., and Hsieh J., “A three-dimensional statistical approach to improved image quality for multislice helical CT,” Med. Phys. 34, 4526–4544 (2007). 10.1118/1.2789499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leipsic J., LaBounty T. M., Heilbron B., Min J. K., Mancini G. B. J., Lin F. Y., Taylor C., Dunning A., and Earls J. P., “Adaptive statistical iterative reconstruction: Assessment of image noise and image quality in coronary CT angiography,” Am. J. Roentgenol 195, 649–654 (2010). 10.2214/AJR.10.4285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidky E. Y. and Pan X., “Image reconstruction in circular cone-beam computed tomography by constrained, total-variation minimization,” Phys. Med. Biol. 53, 4777–4807 (2008). 10.1088/0031-9155/53/17/021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G. H., Tang J., and Leng S., “Prior image constrained compressed sensing (PICCS): A method to accurately reconstruct dynamic CT images from highly undersampled projection data sets,” Med. Phys. 35, 660–663 (2008). 10.1118/1.2836423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Giraldo J. C., Trzasko J., Leng S., Yu L., Manduca A., and McCollough C. H., “Nonconvex prior image constrained compressed sensing (NCPICCS): Theory and simulations on perfusion CT,” Med. Phys. 38, 2157–2167 (2011). 10.1118/1.3560878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]