Abstract

Objective

Resveratrol, trans-3, 4’, 5,-trihydroxystilbene, suppresses multiple myeloma (MM). The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress response component IRE1α/XBP1 axis is essential for MM pathogenesis. We investigated the molecular action of resveratrol on IRE1α/XBP1 axis in human MM cells.

Methods

Human MM cell lines ANBL-6, OPM2, and MM.1S were utilized to determine the molecular signaling events following the treatment with resveratrol. The stimulation of IRE1α/XBP1 axis was analyzed by Western blot and reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. The effect of resveratrol on the transcriptional activity of spliced XBP1 was assessed by luciferase assays. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was performed to determine the effects of resveratrol on the DNA binding activity of XBP1 in MM cells.

Results

Resveratrol activated IRE1α as evidenced by XBP1 mRNA splicing and the phosphorylation of both IRE1α and its downstream kinase JNK in MM cells. These responses were associated with resveratrol-induced cytotoxicity of MM cells. Resveratrol selectively suppressed the transcriptional activity of XBP1s while it stimulated gene expression of the molecules that are regulated by non-IRE1/XBP1 axis of the ER stress response. Luciferase assays indicated that resveratrol suppressed the transcriptional activity of XBP1s through sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), a downstream molecular target of resveratrol. ChIP studies revealed that resveratrol decreased the DNA binding capacity of XBP1 and increased the enrichment of SIRT1 at the XBP1 binding region in the XBP1 promoter.

Conclusion

Resveratrol exerts its chemotherapeutic effect on human MM cells through mechanisms involving the impairment of the pro-survival XBP1 signaling and the activation of pro-apoptotic ER stress response.

Keywords: Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Response, IRE1α, Multiple Myeloma, Resveratrol, XBP1

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a severely debilitating, incurable hematologic malignancy originating from plasma cells. It results in anemia, bone destruction, and impaired renal function. With conventional therapies, MM remains incurable [1]. Both the MM cells and normal plasma cells produce and secrete a large amount of immunoglobulin [2], which require highly developed endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to maintain intracellular protein homeostasis in response to their increased protein synthesis. Agents that disturb the normal function of the ER have displayed efficacy in causing regression and stabilization of MM disease [3-5].

Disturbance of ER homeostasis activates the ER stress response, which is mediated by three parallel signaling branches initiated by PKR-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK), inositol-requiring enzyme 1α (IRE1α), and activating transcription factor-6 (ATF6) [6, 7]. X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1) is the transcription factor central to the IRE1α signaling branch. Upon ER stress, the endoribonulease IRE1α splices the XBP1 transcript to generate the active form, termed spliced XBP1 (XBP1s) [8]. XBP1s regulates genes that are implicated in protein folding, trafficking and secretion, and thus contributes to restoration of ER homeostasis and favors cell survival under ER stress [9]. In contrast, unspliced XBP1 (XBP1u) functions as the dominant negative form that antagonizes the function of XBP1s [10]. Several studies have shown that XBP1s plays a critical role in the development of MM [11, 12]. The mRNA levels of XBP1s have been suggested to be a prognosis indicator for MM patients [13]. To date several strategies have been employed to target IRE1α/XBP1s signaling in treating MM. For instance, Bortezomib, a proteasome inhibitor and a first-in-class drug for MM treatment, has been shown to impair XBP1s signaling via stabilizing XBP1u to antagonize the functions of XBP1s [3]. Pharmacological intervention of IRE1α activation to limit the generation of XBP1s represents another effective strategy to treat MM [5]. Of note, IRE1α also acts as a kinase to activate pro-apoptotic c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling to induce cell death [14]. Inhibition of IRE1α in MM cells might also prevent generation of active JNK to induce cell death in the targeted cells. The seemingly paradoxical dual roles of IREα in generating both pro-survival and pro-apoptotic signaling upon ER stress challenge suggested to us that an agent that activates IRE1α and conserves its capacity to induce JNK while selectively inhibiting XBP1s signaling should be of therapeutic value in the treatment of MM.

Resveratrol (trans-3, 4’, 5,-trihydroxystilbene) is naturally produced by plants in response to external attack and is present in red wine. Numerous reports have demonstrated that resveratrol can prevent the pathogenesis and/or slow down the progression of a variety of diseases, ranging from cancer and metabolic disorders to premature aging [15, 16]. In particular, resveratrol has been reported to inhibit proliferation, induce apoptosis, and overcome chemo-resistance of human MM cells [17-20]. Although the pivotal role of IRE1α/XBP1 in tumorigenicity has been well recognized [21], it remains unclear whether resveratrol regulates the ER stress response in cancer cells such as MM cells. We recently found that sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), a molecular target of resveratrol [22], inhibits the transcriptional activity of XBP1s and sensitizes cells to ER stress-induced apoptosis [23]. This finding raised the possibility that regulation of XBP1s is involved in resveratrol-induced MM cell death. Therefore, we investigated the effect of resveratrol on the IRE1α/XBP1s component of ER stress response in human MM cells.

Materials and methods

Reagents and antibodies

Resveratrol was purchased from Enzo Life Scienes (Plymouth Meeting, PA). Tunicamycin, protease inhibitor cocktail, trypan blue (T8154) and anti-β-actin antibody (A5316) were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Anti-phospho-IRE1α (S724) antibody (ab48187) was from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Anti-IRE1α antibody (#3294), anti-SAPK/JNK antibody (#9258), anti-phospho-SAPK/JNK (T183/Y185) antibody (#4668), and anti-Caspase-3 antibody (#9662) were from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Rabbit normal IgG, anti-GADD153/CHOP antibody (sc-793), anti-SIRT1 antibody (sc-15404), and anti-XBP-1 antibody (sc-7160) were from Santa Cruz Technology (Santa Cruz, CA). HRP-conjugated IgG secondary antibodies were from GE Healthcare Life Sciences (Little Chalfont, UK). Polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes were from Millipore (Bedford, MA).

Cell lines and culture conditions

ANBL-6 cells, an IL-6-dependent MM cell line kindly provided by Dr Diane F. Jelinek (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN), were grown in RPMI1640 containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1×pen/strep antibiotics, and 2 mM L-glutamine (Invitrogen) and supplemented with 2 ng/mL IL-6 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). MM.1S cells, kindly provided by Dr Steven Rosen (Northwestern University, Chicago, IL), and OPM2 cells, kindly provided by Dr Klaus Podar (Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA), were grown in RPMI1640 containing 10% FBS, 1×pen/strep antibiotics, and 2 mM L-glutamine (Invitrogen). HEK 293 cells were cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS and 1×pen/strep antibiotics.

Cell viability assay

Cells were treated with resveratrol for 24 h and then stained with trypan blue. The number of live and dead cells was counted using a hemacytometer. Apoptotic cells were enumerated with a fluorescent microscope after Hoechest 33342 staining.

Western blot

Cells were collected and centrifuged at 500 ×g for 5 min. After the washing with cold PBS, cell pellets were lysed in cell lysis buffer (20 mM Tris HCl pH7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40,1 mM EGTA, 1mM EDTA, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM orthovanadate, 1×protease inhibitor cocktail, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). Protein was extracted after centrifuge at 14,000×g for 15 min at 4°C. Equal amounts (10 μg) of boiled protein samples were run on an SDS polyacrylamide gel. The separated proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes. The following primary antibodies were used: anti-XBP1 (1:1000), anti-phospho-IRE1α (1:2000), anti-IRE1α (1:1000), anti-SIRT1 (1:1000), anti-phospho-SAPK/JNK (1:000), anti-SAPK/JNK (1:1000), anti-CHOP (1:500), anti-Caspase-3 (1:1000) and β-actin (1:20000). Signals were detected using HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:2000) and ECL™ reagents (GE Healthcare Life Sciences).

RNA extraction, Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, and detection of XBP1splicing

Total RNA was isolated from cell pellets using Trizol® reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription was conducted using a reverse transcription system kit (Promega, Cat.A3500). An aliquot of the product cDNA was used for real-time PCR with iQ™ SYBR Green Supermix and iCycler iQ PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories). 18S rRNA was applied as an internal control for data analysis. The nucleotide sequences of primers used for PCR are as follow: 18S rRNA 5’- ATCCCTGAAAAGTTCCAGCA-3’ and 5’- CCCTCTTGGTGAGGTCAATG-3’; XBP1 5’- CCCATGGATTCTGGCGGTATTGAC-3’ and 5’- TCCTTCTGGGTAGACCTCTGGGAG-3’; VEGFA 5’- TACCTCCACCATGCCAAGTG-3’ and 5’- GATGATTCTGCCCTCCTCCTT-3’; GADD34 5’- GTGGAAGCAGTAAAAGGAGCAG-3’ and 5’ CAGCAACTCCCTCTTCCTCG-3’; CHOP 5’- CAGAACCAGCAGAGGTCACA-3’ and 5’- AGCTGTGCCACTTTCCTTTC-3’.

XBP1 mRNA processing was measured by amplifying the XBP1 cDNA with the primers: 5’-AAACAGAGTAGCAGCTCAGACTGC-3’; 5’-TCCTTCTGGGTAGACCTCTGGGAG-3’. The PCR products were digested with PstI and resolved on a 1.5% agarose gel.

Plasmids and luciferase reporter assay

Constructs expressing XBP1s, 5×UPR element (UPRE), or SIRT1 shRNA were described previously [23]. Transfection was done in HEK293 using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen). The transcriptional activity of XBP1s was determined by the dual luciferase assay (Promega).

Chromatin immuoprecipitation (ChIP)

Chromatin immunoprecipitation was performed using the SimpleCHIP enzymatic chromatin immunoprecipitation kit (Cell Signaling Technology) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For immunoprecipitation, each aliquot of total chromatin was incubated with 2 μg of anti-XBP1 antibody or anti-SIRT1 antibody or rabbit normal IgG served as the negative control. The occupancy of protein was assessed by real time-PCR using the following primers: 5’-AATCCGTTTGTGGAGGAC-3’; 5’-TTTCAGGACCGTGGCTAT-3’.

Statistical analysis

All the experiments were repeated at least 2 times. Data are presented as means ± S.E.M. Statistical significance was analyzed by Student’s t-test using Graphpad (http://www.graphpad.com).

Results

Resveratrol triggers the ER stress response and induces MM cell death

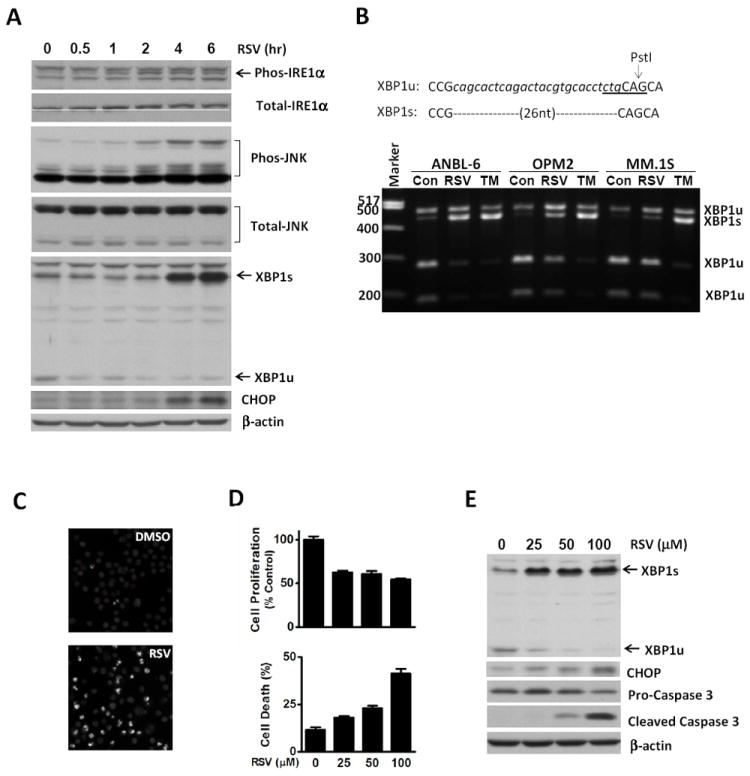

Since ER stress is one of the major cell stress responses that are inherently linked to cell apoptosis [24], and MM cells are hypersensitive to ER stress challenge [12, 25], we determined whether resveratol activated the ER stress response and its pro-apoptotic effects in MM cells. As shown in Fig. 1A, treatment of ANBL-6 MM cells with resveratrol increased the phosphorylation of IRE1α as detected by a specific antibody. We also observed a slower migration of IRE1α which was correlated with its phosphorylation modification. In accordance with the report that the activation of IRE1α results in activation of JNK [14], we found that the phosphorylation of JNK showed a similar time-course pattern as IRE1α (Fig. 1A). Consistent with the phosphorylation of IRE1α, there was a significant increase in XBP1s protein levels. The decrease of XBP1u protein levels was also seen with the antibody to XBP1s. The ER stress response of MM cells exposed to resveratrol was also evidenced by the increase in CHOP protein levels (Fig. 1A). When we analyzed the XBP1 mRNA, we found that resveratrol induced splicing of XBP1 mRNA. The splicing of XBP1 mRNA caused by resveratrol in ANBL-6 cells was comparable to that induced by the classical ER stress inducer, tunicamycin (Fig. 1B). In OPM2 and MM.1S cells, the treatment of resveratrol also induced the splicing of XBP1 mRNA. These results indicate that resveratrol activates the ER stress response and induces both XBP1s production and the pro-apoptotic molecules JNK and CHOP in MM cells.

Figure 1.

Resveratrol induces activation of IRE1α and causes cell death in MM cells. (A) ANBL-6 cells were treated with 100 μM resveratrol (RSV) for the indicated time periods. Whole cell lysates were harvested and analyzed for phosphorylated and total IRE1α, phosphorylated and total JNK, XBP1s and XBP1u, CHOP, and the loading control β-actin. (B) ANBL-6, OPM2, and MM.1S MM cells were treated with vehicle (DMSO, Con), 100 μM RSV, and a classical ER stressor tunicamycin (2.5 μg/ml, TM) for 6 hrs. The splicing of XBP1 mRNA was examined. (C-E) ANBL-6 cells were treated with RSV for 24 hrs at the indicated concentrations. (C) Cells, treated with vehicle (DMSO) or 100 μM RSV, were stained with Hoechest 33342 and visualized under a fluorescence microscope. (D) Cell viability was assessed by trypan blue exclusion. (E) Whole cell lysates were harvested and analyzed for XBP1, CHOP, Caspase-3 and the loading control β-actin.

We confirmed by DNA staining that resveratrol induced cell apoptosis in our experimental model system (Fig. 1C), and resveratrol inhibited cell proliferation and induced cell death dose-dependently in ANBL-6 MM cells (Fig. 1D). The apoptotic change in these cells was reflected by the cleavage of Caspase-3 (Fig. 1E). Importantly, we found that under the identical experimental conditions, resveratol dose-dependently triggered splicing of XBP1 mRNA, as shown by increased XBP1s and decreased XBP1u protein levels as well as induced CHOP protein (Fig. 1E). These results clearly demonstrate that the resveratrol-induced ER stress response is correlated with resveratrol-induced cell apoptosis.

Resveratrol represses XBP1s signaling in MM cells

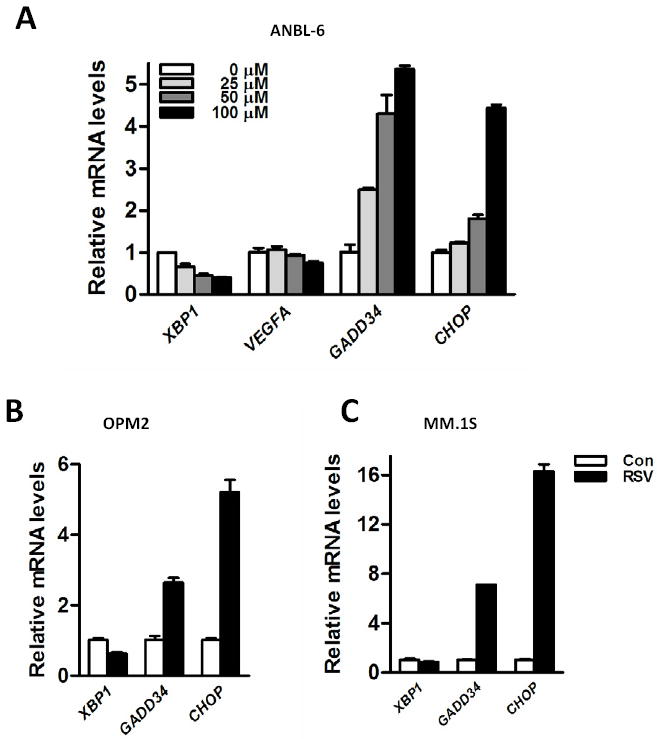

Having observed that resveratrol activates the ER stress response, we next analyzed the effects of resveratrol on mRNA expression of the target genes (XBP1, VEGFA, GADD34, and GADD153/CHOP) of these signaling pathways in various human MM cells. Among these target genes, both GADD34 and CHOP are regulated by non-IRE1α (PERK and ATF6) branches of the ER stress response [2]. Human VEGFA contains putative XBP1s binding sites in its promoters and the presence of these sites are believed to be conserved across the species among human, murine and rat as recently shown [26]. XBP1 has been reported to be one of the downstream target genes of XBP1s in a positive feedback loop [27]. As shown in Fig. 2A, we found that resveratrol suppressed the expression levels of VEGFA and total XBP1 mRNA in ANBL-6 cells, whereas the expression levels of GADD34 mRNA and CHOP mRNA were strongly induced. In OPM2 and MM.1S cells, resveratrol caused a similar pattern of changes in ER stress response downstream genes (Fig. 2B and C). These results indicated that resveratrol selectively inhibits the signal transduction of the XBP1s pathway while enhancing the mRNA expression of downstream target genes of the non-IRE1α cascades of the ER stress response, such as the PERK/eIF2α signaling pathway, as reflected by up-regulated mRNA levels of CHOP and GADD34 in resveratrol-treated MM cells (Figs. 2A to 2C).

Figure 2.

XBP1 signaling is down-regulated by resveratrol in MM cells. (A) ANBL-6 cells were treated with resveratrol for 24 hrs at the indicated concentrations. RNA was extracted from each sample and real-time RT-PCR was performed to analyze the levels of XBP1, VEGFA, GADD34, and CHOP mRNA. OPM2 (B) and MM.1S (C) cells were treated with or without 100 μM resveratrol. RNA was extracted from each sample and real-time RT-PCR was performed to analyze the levels of XBP1, GADD34, and CHOP mRNA.

Resveratrol suppresses the transcriptional activity of XBP1s through SIRT1

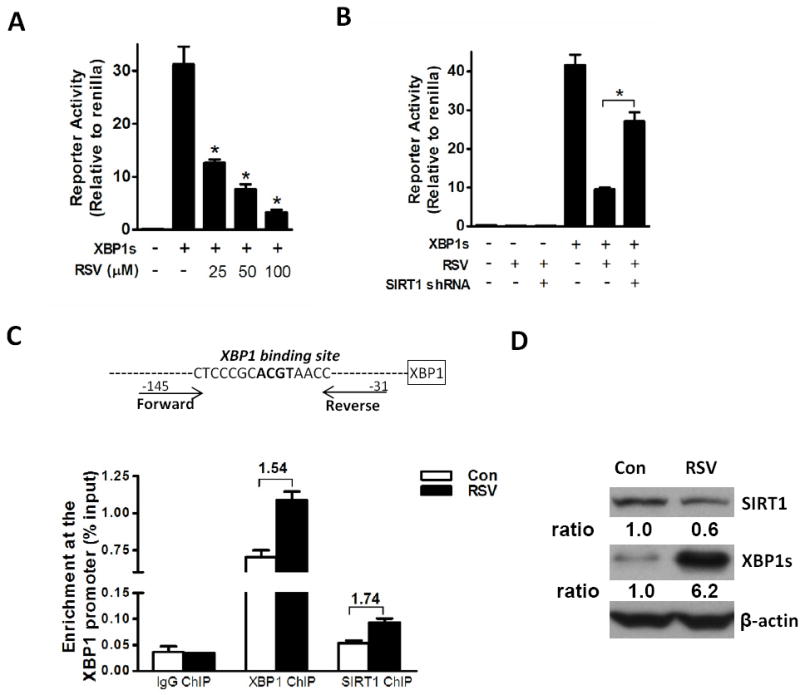

The reduced mRNA levels of XBP1 in resveratrol-treated human MM cells in the presence of elevated XBP1s protein suggest that resveratrol may inhibit the transcriptional activity of XBP1s. To test this possibility, we used a 5×UPRE luciferase reporter construct, a reporter system that is widely used to reflect the transcriptional activity of XBP1s [28]. We found that resveratrol dose-dependently inhibited the relative luciferase activity of 5×UPRE induced by co-transfected XBP1s (Fig. 3A). Since we have demonstrated previously that SIRT1, a resveratrol target, repressed the transcriptional activity of XBP1s [23], these results suggested that SIRT1 may play a role in mediating the effects of resveratrol on the transcriptional activity of XBP1s. To test this hypothesis, we knocked down endogenous SIRT1 using SIRT1 shRNA. The SIRT1 shRNA significantly blocked the inhibitory effects of resveratrol on the transcriptional activity of XBP1s (Fig. 3B). These results promoted us to test the possibility that SIRT1 is involved in the action of resveratrol on the XBP1 autoregulation loop, where XBP1s binds to the promoter of XBP1 gene in human species [27]. ChIP assays confirmed a significant occupancy of XBP1s at the promoter binding site of human XBP1 gene in both control and resveratrol treated ANBL-6 cells (Fig. 3C). Consistent with the finding that resveratrol induced XBP1 mRNA splicing (Fig. 1A and B), resveratrol induced a 6.2-fold increase in XBP1s protein levels in ANBL-6 cells (Fig. 3D). However, compared with the dramatic increase in XBP1s protein levels, there was only a slight increase (1.54-fold) of enrichment of XBP1s on the XBP1 promoter. Further, we noticed an enrichment of SIRT1 (1.74-fold) at the XBP1 binding site although total protein levels of SIRT1 decreased after exposure to resveratrol (Fig. 3D). These results suggest that resveratrol possibly affects the transcriptional activity of XBP1s by recruiting SIRT1 to the promoter.

Figure 3.

Resveratrol represses the transcriptional activity of XBP1s through SIRT1. (A and B) 5×UPRE-luciferase reporter and XBP1s expression constructs were used to measure the transcriptional activity of XBP1s. Firefly luciferase value was divided by Renilla luciferase value for normalization in each sample. (A) Cells were treated with resveratrol (RSV) at the indicated concentrations for 6 hrs. *P < 0.01 compared to the control group (with XBP1s, no RSV), as determined using Student’s t-test. (B) Cells were co-transfected with the construct expressing SIRT1 shRNA or an empty control vector. Luciferase assays were done after a 6 hr treatment with 50 μM RSV. *P < 0.01, as determined using Student’s t test. (C) The upper panel shows the design of the primers around XBP1 binding site in the human XBP1 promoter. In the lower left panel, ChIP assays were performed on the samples from cells treated with vehicle (DMSO) or 100 μM RSV for 6 hrs. Signals obtained from each ChIP were calculated by dividing with signals obtained from the corresponding input sample. (D) In a parallel experiment with (C), the cell lysates were analyzed for the protein levels of SIRT1 and XBP1s expression via Western blot.

Discussion

Resveratrol has been shown to inhibit proliferation and cause apoptosis of MM cells [18-20]. Its anti-myeloma efficacy has been linked to its capacity to induce a mitochondrial stress response [20], suppress constitutive NF-κB and STAT3 signaling pathways [19], or to modify the expression of apoptotic regulatory proteins [29]. However, whether resveratrol induces the pro-apoptotic effects of ER stress responses in MM tumor cells remains unclear. Our study demonstrates that resveratrol is sufficient to induce ER stress and its pro-apoptotic effects. Consistent with the findings in resveratrol-induced apoptosis in human colon cancer cells [30], we found that resveratrol induced CHOP expression, a downstream mediator of the PERK signaling branch of the ER stress response [2] and pro-apoptotic molecules [24]. The induction of CHOP has also been shown to mediate cell death associated with bortezomib-induced ER stress in MM [13]. In addition, we demonstrated that resveratrol activates the IRE1α/XBP1s signaling pathway, the most conserved ER stress response signaling in MM cells. This was shown by the elevated phosphorylation of IRE1α, a prerequisite of IRE1α activation, and consequently XBP1 mRNA splicing and activation of JNK (Fig. 1A). The latter has been implicated in MM apoptosis [31]. Further the JNK inhibitor SP600125 inhibited resveratrol-induced apoptosis of MM cells [20]. In addition, resveratrol displayed similar dose-dependent effects on activating Caspase-3 signaling and the pro-apoptotic signaling of ER stress responses (Figs. 1D and 1E), indicating that the two events are linked. These data demonstrate that resveratrol induces the ER stress response, and that induction of the pro-apoptotic effects of ER stress represents a novel mechanism underlying resveratrol-induced MM cell death.

The IRE1α/JNK/XBP1 signaling plays both pro-survival and pro-apoptotic roles under stress conditions mediated by XBP1s and JNK, respectively [14, 32]. XBP1s drives mRNA expression of proteins that are involved in protein trafficking, folding and the protein quality control ER-associated degradation pathway [28]. XBP1s is essential for pathogenesis of MM and the survival and growth of MM cells because MM cells synthesize large amounts of proteins and have great amounts of intrinsic ER stress [11]. Thus, various strategies have been developed to target XBP1s and its function to treat MM cells. For instance, pharmacological repression of IRE1α endoribonulease activity led to inhibition of XBP1 mRNA splicing and sensitization of cells to ER stress-induced cell death [5]. Bortezomib increased the intrinsic ER stress in MM cells by blocking protein degradation and thus inducing the accumulation of a large amount of unfolded and/or misfolded proteins. However, Bortezomib repressed XBP1s function via elevating the protein levels of XBP1u, the unspliced and transcriptionally inactive form of XBP1 which antagonizes the functions of XBP1s [3]. Intriguingly, our study revealed a distinct mechanism by which resveratrol affects the XBP1s signaling in MM cells. We demonstrated that although resveratrol activated IRE1α activity and consequently enhanced mRNA splicing of XBP1, it paradoxically exerted a specific inhibitory effect on the transcriptional activity of XBP1s without elevating XBP1u, which consequently led to a defective auto-regulation loop for XBP1, in which XBP1s transcriptionally regulates mRNA expression of total XBP1. This notion is supported by the observation that there were reduced total XBP1 mRNA levels despite the increased XBP1s protein levels in MM cells in response to resveratrol treatment (Fig. 1E and 2A). Further, it was noticed that resveratrol also repressed mRNA expression of another XBP1s target gene VEGFA (Fig. 2A). Taken together, these results suggest that resveratrol induces ER stress and inhibits the mRNA expression of XBP1s inducible genes, such as XBP1 and VEGFA, which favor the survival of MM cells upon ER stress.

We examined the mechanism underlying the effects of resveratrol on the autoregulation loop of XBP1 mRNA expression and found that resveratrol was a potent inhibitor of the transcriptional activity of XBP1s in a SIRT1-dependent manner. SIRT1 is a well-known downstream molecular target of resveratrol [22]. In the current study, we found that in MM cells, resveratrol increased the chromatin-bound SIRT1 at the XBP1 binding region in the promoter of XBP1 gene (Fig. 3C). Recently, we found that SIRT1 negatively regulates the transcriptional activity of XBP1s [23]. Our results suggest that resveratrol inhibits the transcriptional activity of XBP1s via promoting the enrichment of SIRT1 on the promoter of XBP1s downstream target genes, thus revealing an important role of SIRT1 in mediating resveratrol’s inhibitory effect on XBP1s transcriptional activity. Given the essential role of XBP1s in MM cells, this mechanism may explain a recent finding that the SIRT1 activator, SIRT1720, induced cytotoxicity in human MM cells [33]. Although many studies examined if SIRT1 is a prognosis indicator in a wide range of solid tumor cancers, little is known about the role of SIRT1 in MM. Further studies to test whether inhibition of SIRT1 contributes to the high transcriptional activity of XBP1s in MM cells are warranted. Another important question that requires future studies is how resveratrol enhances recruitment of SIRT1 to the promoter of XBP1 gene. It has been shown that resveratrol can activate SIRT1 both directly and indirectly [22]. In addition, we recently reported that SIRT1 binds and posttranslationally modifies XBP1s [23]. Therefore, resveratrol can likely regulate either SIRT1 and/or XBP1s to modulate their binding affinities for each other and consequently increase SIRT1 recruitment to the XBP1 promoter via XBP1s protein, which directly binds the XBP1 promoter. To test the postulation, future studies are required to identify the putative sites of XBP1s, which resveratrol and/or SIRT1 could act upon, and to determine the roles of the XBP1s WT and mutant(s) proteins that are either resistant or prone to the actions of resveratrol and/or SIRT1 in mediating the effects of resveratol on SIRT1 recruitment to the XBP1 promoter.

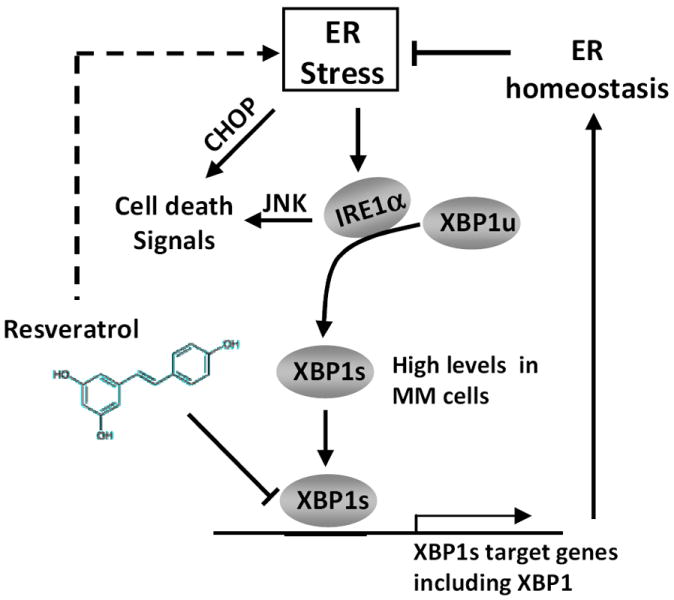

In summary, this study reveals a novel mechanism by which resveratrol induces cell death in MM cells. Resveratrol activates ER stress signaling and its pro-apoptotic effects while inhibiting transcriptional function of XBP1s and the pro-survival signaling of the ER stress signaling (Fig. 4). These results suggest that resveratrol might be an excellent pharmaceutical agent for treating MM by subjecting MM cells to double-jeopardy and tilt the survival/apoptosis balance of the ER stress response towards cell death. It is also plausible that resveratrol may function in the same manner in other cancers in which the tumor growth relies on a highly expressed IRE1α/XBP1 branch of the ER stress response.

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of the molecular mechanisms by which resveratrol induces the pro-apoptotic effects of ER stress responses and represses the cell survival signals (XBP1s signaling) in MM. Resveratrol increases ER stress and the 3 main pathway branches PERK, ATF6, and IRE1α. This results in activation of cell death signals via IRE1α activation of JNK and PERK and ATF6 activation of CHOP. While activation of IRE1α also results in increased XBP1s, resveratrol specifically inhibits the transcriptional activity of XBP1s, which leads to impairment of the cell survival functions and promotes cell death.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, USA [grant number DE017439 (to H.-J. O.)], and the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation (to H.-J.O.). F.M.W is in part supported by the National Natural Science Foundation, P. R. China [grant number30901677].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Raab MS, Podar K, Breitkreutz I, Richardson PG, Anderson KC. Multiple myeloma. Lancet. 2009;374:324–339. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60221-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Todd DJ, Lee AH, Glimcher LH. The endoplasmic reticulum stress response in immunity and autoimmunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:663–674. doi: 10.1038/nri2359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee AH, Iwakoshi NN, Anderson KC, Glimcher LH. Proteasome inhibitors disrupt the unfolded protein response in myeloma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9946–9951. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1334037100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Obeng EA, Carlson LM, Gutman DM, Harrington WJ, Jr, Lee KP, Boise LH. Proteasome inhibitors induce a terminal unfolded protein response in multiple myeloma cells. Blood. 2006;107:4907–4916. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Papandreou I, Denko NC, Olson M, et al. Identification of an Ire1alpha endonuclease specific inhibitor with cytotoxic activity against human multiple myeloma. Blood. 2011;117:1311–1314. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-303099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin JH, Walter P, Yen TS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in disease pathogenesis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2008;3:399–425. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.151434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:519–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoshida H, Matsui T, Yamamoto A, Okada T, Mori K. XBP1 mRNA is induced by ATF6 and spliced by IRE1 in response to ER stress to produce a highly active transcription factor. Cell. 2001;107:881–891. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00611-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin JH, Li H, Yasumura D, et al. IRE1 signaling affects cell fate during the unfolded protein response. Science. 2007;318:944–949. doi: 10.1126/science.1146361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoshida H, Oku M, Suzuki M, Mori K. pXBP1(U) encoded in XBP1 pre-mRNA negatively regulates unfolded protein response activator pXBP1(S) in mammalian ER stress response. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:565–575. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200508145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carrasco DR, Sukhdeo K, Protopopova M, et al. The differentiation and stress response factor XBP-1 drives multiple myeloma pathogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:349–360. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iwakoshi NN, Lee AH, Vallabhajosyula P, Otipoby KL, Rajewsky K, Glimcher LH. Plasma cell differentiation and the unfolded protein response intersect at the transcription factor XBP-1. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:321–329. doi: 10.1038/ni907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bagratuni T, Wu P, Gonzalez de, Castro D, et al. XBP1s levels are implicated in the biology and outcome of myeloma mediating different clinical outcomes to thalidomide-based treatments. Blood. 2010;116:250–253. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-263236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Urano F, Wang X, Bertolotti A, et al. Coupling of stress in the ER to activation of JNK protein kinases by transmembrane protein kinase IRE1. Science. 2000;287:664–666. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5453.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baur JA, Sinclair DA. Therapeutic potential of resveratrol: the in vivo evidence. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:493–506. doi: 10.1038/nrd2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan N, Afaq F, Mukhtar H. Cancer Chemoprevention Through Dietary Antioxidants: Progress and Promise. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10:475–510. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun C, Hu Y, Liu X, et al. Resveratrol downregulates the constitutional activation of nuclear factor-kappaB in multiple myeloma cells, leading to suppression of proliferation and invasion, arrest of cell cycle, and induction of apoptosis. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2006;165:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2005.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boissy P, Andersen TL, Abdallah BM, Kassem M, Plesner T, Delaisse JM. Resveratrol inhibits myeloma cell growth, prevents osteoclast formation, and promotes osteoblast differentiation. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9943–9952. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhardwaj A, Sethi G, Vadhan-Raj S, et al. Resveratrol inhibits proliferation, induces apoptosis, and overcomes chemoresistance through down-regulation of STAT3 and nuclear factor-kappaB-regulated antiapoptotic and cell survival gene products in human multiple myeloma cells. Blood. 2007;109:2293–2302. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-003988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reis-Sobreiro M, Gajate C, Mollinedo F. Involvement of mitochondria and recruitment of Fas/CD95 signaling in lipid rafts in resveratrol-mediated antimyeloma and antileukemia actions. Oncogene. 2009;28:3221–3234. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shajahan AN, Riggins RB, Clarke R. The role of X-box binding protein-1 in tumorigenicity. Drug News Perspect. 2009;22:241–246. doi: 10.1358/dnp.2009.22.5.1378631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herranz D, Serrano M. SIRT1: recent lessons from mouse models. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:819–823. doi: 10.1038/nrc2962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang FM, Chen YJ, Ouyang HJ. Regulation of unfolded protein response modulator XBP1s by acetylation and deacetylation. Biochem J. 2010;433:245–252. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merksamer PI, Papa FR. The UPR and cell fate at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:1003–1006. doi: 10.1242/jcs.035832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davenport EL, Moore HE, Dunlop AS, et al. Heat shock protein inhibition is associated with activation of the unfolded protein response pathway in myeloma plasma cells. Blood. 2007;110:2641–2649. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-053728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pereira ER, Liao N, Neale GA, Hendershot LM. Transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of proangiogenic factors by the unfolded protein response. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12521. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kakiuchi C, Iwamoto K, Ishiwata M, et al. Impaired feedback regulation of XBP1 as a genetic risk factor for bipolar disorder. Nat Genet. 2003;35:171–175. doi: 10.1038/ng1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee AH, Iwakoshi NN, Glimcher LH. XBP-1 regulates a subset of endoplasmic reticulum resident chaperone genes in the unfolded protein response. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:7448–7459. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.21.7448-7459.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jazirehi AR, Bonavida B. Resveratrol modifies the expression of apoptotic regulatory proteins and sensitizes non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and multiple myeloma cell lines to paclitaxel-induced apoptosis. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:71–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woo KJ, Lee TJ, Lee SH, et al. Elevated gadd153/chop expression during resveratrol-induced apoptosis in human colon cancer cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;73:68–76. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chauhan D, Li G, Hideshima T, et al. JNK-dependent release of mitochondrial protein, Smac, during apoptosis in multiple myeloma (MM) cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:17593–17596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300076200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gupta S, Deepti A, Deegan S, Lisbona F, Hetz C, Samali A. HSP72 protects cells from ER stress-induced apoptosis via enhancement of IRE1alpha-XBP1 signaling through a physical interaction. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000410. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chauhan D, Bandi M, Singh AV, et al. A Novel SIRT1 Activator SIRT1720 Triggers In Vitro and In Vivo Cytotoxicity In Multiple Myeloma Via ATM-Dependent Mechanism. Blood. 2010;116 doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-276626. Abstact 3007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]