Abstract

Rolipram, a specific inhibitor of the phosphodiesterase IV (PDE IV), has recently been shown to exert neuroprotective effects in an Alzheimer transgenic mouse model and in hypoxic-ischemic damage in the rat brain. It activates the cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA)/cAMP regulatory element-binding protein (CREB) signaling pathway and it inhibits inflammation. We tested the neuroprotective effects of the specific PDE IV inhibitor rolipram in C57BL/6 mice treated with 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP). We found that rolipram administered at 1.25mg/kg or 2.5mg/kg doses significantly attenuated MPTP-induced dopamine depletion in the striatum, and reduced the loss of tyrosine hydroxylase-positive neurons in the substantia nigra. There was a bell-shaped dose effect with greater efficacy at the 1.25 mg/kg dose than 2.5 mg/kg and a higher dose of rolipram, 5mg/kg, had no protective effect and even increased the mortality of animals when co-administered with MPTP. Rolipram did not interact with MPTP in its absorption into the brain and in its metabolism to 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+). Our data show a neuroprotective effect of the PDE IV specific inhibitor rolipram against dopaminergic neuron degeneration, suggesting that PDE IV inhibitors might be a potential treatment for Parkinson’s disease.

Keywords: Rolipram, Phosphodiesterase IV inhibitor, Parkinson’s disease

Rolipram is a specific inhibitor of phosphodiesterase IV (Barad et al., 1998). It has previously been shown to exert protective effects in animal models of inflammation including experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (Dinter et al., 2000; Martinez et al., 1999). It has several potential mechanisms by which it could exert neuroprotective effects. It acts on macrophages to exert anti-inflammatory effects. Specifically, it can block lipopolysaccharide and tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced increases in inducible nitric oxide synthase as well as superoxide anion production from microglial cells (Beshay et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2002). In addition, it can increase phosphorylation of cyclic AMP response element binding protein (CREB), which may exert neuroprotective effects by increasing the expression of growth factors such as BDNF (MacKenzie and Houslay, 2000). Inhibiting BDNF expression in the substantia nigra causes a loss of dopaminergic neurons (Porritt et al., 2005). Increased activity of CREB protects against hypoxia induced damage in neonatal rats and it improves memory and synaptic transmission in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease (Lee et al., 2004; Gong et al., 2004). A previous study showed that several other type IV phosphodiesterase inhibitors showed efficacy against MPTP toxicity (Hulley et al., 1995). In the present experiments, we therefore investigated whether administration of rolipram, a specific phosphodiesterase IV inhibitor, could exert neuroprotective effects against MPTP induced neurotoxicity.

Rolipram obtained from Schering Aktiengesellschaft in Germany, is the racemate of 4-(3’-cyclopentyloxy-4’-methoxyphenyl)-2-pyrrolidone, has good solubility in polar organic solvents like ethanol or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), but is only sparingly soluble in water. Therefore, DMSO was used as the vehicle to deliver rolipram. DMSO has been widely used as a solvent for delivering a variety of non-water-soluble compounds to experimental animals. There were controversial reports that DMSO may have potential neuroprotective effects (Repine et al., 1981; Shimizu et al., 1997; Little et al., 1981; Little et al., 1983). We observed that a DMSO injection volume exceeded over 4ml/kg causes mortality in mice. DMSO used as a vehicle was reported to be non-toxic at a dose of 2ml/kg (Ginsberg et al., 2003). MPTP (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was administered to 12 weeks old male C57Bl/6 mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) with two different i.p. dosage regimens in our two separate experiments, i.e. 15mg/kg every 2 hours for 3 doses and 10mg/kg every 2 hours for 4 doses. Rolipram, 1.25 mg/kg, 2.5 mg/kg and 5 mg/kg, was injected i.p. 1 hour before the first MPTP injection, between the MPTP injections, 1 and 12 hours after the last MPTP injection (cumulative doses of 5 mg/kg, 10 mg/kg and 20 mg/kg over 24h). Control mice were injected with the same volume of pure DMSO (1.6ml/kg, 6.4 ml/kg over 24h).

Animals were sacrificed 7 days after the MPTP injection and the striata were rapidly dissected and kept at −80°C for catecholamine measurement. Midbrains of these mice were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for histology. Mice treated with MPTP 15mg/kg, 3 doses with/without rolipram 1.25 mg/kg were sacrificed 90 min after the last dose of MPTP and striata were dissected for measurement of MPP+ levels.

Striatal dopamine (DA) and its metabolites 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) and homovanillic acid (HVA) were measured by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with electrochemical detection as previously described (Yang et al., 2005) and MPP+ was measured by HPLC with a fluorescence detector (Naoi et al., 1987). Midbrain sections (50 um) including substantia nigra were prepared for tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) immunohistochemistry and Nissl staining and the cells in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) were counted using the optical fractionator method as described previously (Yang et al., 2005).

The data are expressed as the means ± standard error of mean. Statistical comparisons were made by one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey-Kramer test for multiple group comparisons.

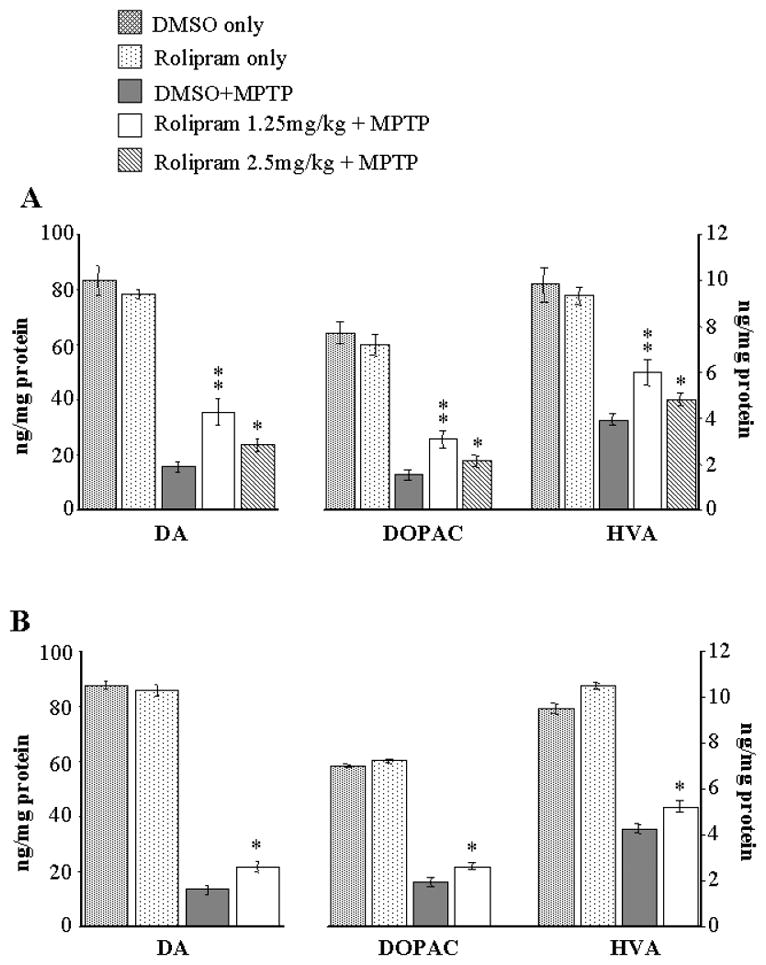

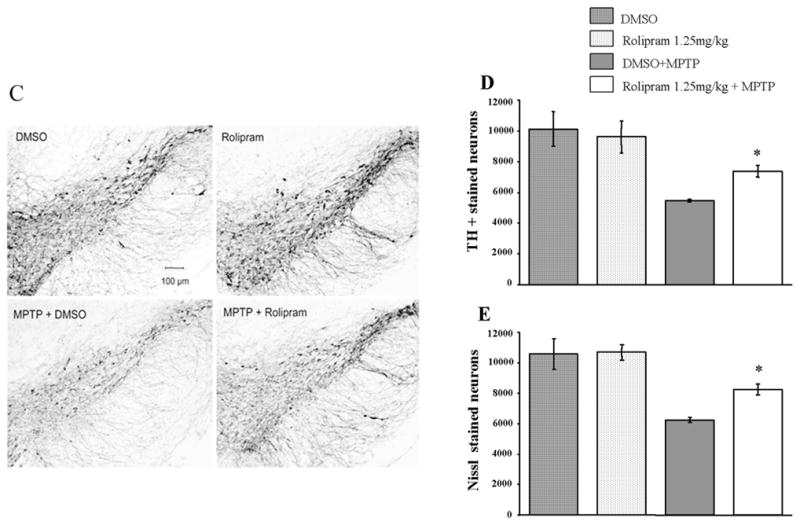

Figure 1 shows protective effects of rolipram on MPTP treated mice. In our initial trial, both the 1.25mg/kg and 2.5mg/kg rolipram dose regimens significantly protected dopamine and its metabolites levels in the striatum of mice treated with MPTP, 15mg/kg for 3 doses (Figure 1A). The 1.25mg/kg dose regimen showed better protection than 2.5mg/kg one. However, the 5mg/kg dose regimen had no protective effect and increased the mortality of animals when co-administered MPTP in our second experiment. We were, therefore, unable to measure dopamine and its metabolites in this high dose rolipram group. The protective effect of rolipram was confirmed in a second experiment (Figure 1B), with the 1.25mg/kg rolipram dose used in mice treated with MPTP 10mg/kg for 4 doses. The neurotoxic effect of MPTP on dopaminergic TH-positive neurons in the SNpc was significantly attenuated by co-injection with 1.25mg/kg rolipram (Figure 1C and D), and this was confirmed with Nissl stained neuron counts (Figure 1E). MPP+ levels at 90 min after MPTP injection showed no significant difference between animals treated with MPTP/vehicle and with MPTP/rolipram (4.24 ± 0.5 vs 4.15 ± 0.2 ng/mg wet tissue). This indicates that rolipram has no effect on MPTP uptake into brain or MPTP metabolism to MPP+.

Figure 1.

Protective effects of rolipram on MPTP treated mice. (A) Animals received MPTP 15mg/kg, i.p., every 2 hours for 3 doses. The MPTP-induced dopamine and metabolites depletion was attenuated significantly by rolipram at both 1.25 and 2.5mg/kg (* p<0.05, compared to DMSO+MPTP), with a better protective effect at 1.25mg/kg (** p<0.01, compared to DMSO+MPTP). (B) Animals were given 10mg/kg of MPTP i.p., every 2 hours for total 4 doses, and co-administration of rolipram 1.25mg/kg significantly protected against MPTP-induced dopamine and metabolites depletion in the striatum (* p<0.05, compared to DMSO+MPTP). (C) Representative slices show that neurotoxic effect of MPTP on tyrosine hydroxylase-positive neurons in the substantia nigra compacta is attenuated by co-injection with rolipram. MPTP was dosed i.p., 15mg/kg, every 2 hours for 3 doses and rolipram was dosed 1.25mg/kg with the regimen described in text. Scale bar = 100 um. (D) The quantitative data show that the loss of tyrosine hydroxylase-positive (TH+) staining in the substantia nigra compacta is significantly abated by co-injection of rolipram (* p<0.05, compared to DMSO+MPTP). (E) TH+ neuron loss caused by MPTP and attenuation by rolipram was confirmed with Nissl stained neuron counts. DMSO means dimethyl sulphoxide used as vehicle.

In the present experiments, we show that administration of the specific phosphodiesterase IV inhibitor rolipram exerts neuroprotective effects in the MPTP model of Parkinson’s disease in mice. We found that it significantly attenuates MPTP induced dopamine depletion and it protects against loss of tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactive neurons in the substantia nigra. The effects show an inverted dose response trend. Efficacy at the 1.25 mg dose was better than 2.5 mg dose. A higher dose of rolipram, 5mg/kg, had no protective effect and even increased the mortality of animals when co-administered with MPTP. Rolipram’s effects did not appear to be due to alteration in the pharmacokinetics or metabolism of MPTP, since MPP+ levels were unaltered.

Rolipram may exert its neuroprotective effects by two different mechanisms. It has been shown in numerous studies to block the effects of inflammatory cytokines on macrophages and in particular to block the induction to iNOS (Beshay et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2002). iNOS knockout mice are resistant to MPTP toxicity (Dehmer et al., 2000; Liberatore et al., 1999). Furthermore, rolipram may block microglial produced superoxide. Mice deficient in NADPH oxidase also are partially resistant to MPTP neurotoxicity (Wu et al., 2003). The doses of rolipram required for anti-inflammatory effects are in the range used in the present experiments (Dinter et al., 2000; Martinez et al., 1999).

An alternative mechanism of protection is by increasing phosphorylation of CREB which occurs with low doses of rolipram (Gong et al., 2004; Monti B et al., 2006). CREB is a transcription factor, which modulates the production of a number of growth factors including NGF and BDNF. Administration of BDNF is neuroprotective against MPTP and 6-hydroxydopamine (Porritt et al., 2005; Firm et al. 1994; Tsukahara et al., 1995). It is, therefore, possible that increased phosphorylation of CREB mediated by activation of protein kinase A due to increased cyclic AMP may play a role in the neuroprotective effects of rolipram. CREB-dependent transcriptional activation protects against polyglutamine induced cytotoxicity (Shimohata et al., 2005). Our studies are consistent with a previous report that other inhibitors of type IV phosphodiesterases produced neuroprotective effects against MPTP toxicity (Hulley et al., 1995). It was demonstrated that they increased survival of dopaminergic neurons in culture and they reduced MPTP induced dopamine depletion in the striatum of C57 Bl/6 mice. Our studies, therefore, provide further evidence that administration of phosphodiesterase IV inhibitors might be useful as a potential treatment for Parkinson’s disease. The inverted dose response curve however, would suggest that one would have to obtain an optimal dosage. Rolipram was previously under development as an anti-depressant but clinical development was halted due to nausea at higher doses. Other phosphodiesterase inhibitors are currently under development and appears to be better tolerated, and therefore, more attractive as neuroprotective agents.

Acknowledgments

Grants: Department of Defense and Parkinson’s Disease Foundation

The secretarial assistance of Greta Strong is gratefully acknowledged. This work was supported by grants from the Department of Defense and the Parkinson’s Disease Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Barad M, Bourtchouladze R, Winder DG, Golan H, Kandel E. Rolipram, a type IV- specific phosphodiesterase inhibitor, facilitates the establishment of long-lasting long- term potentiation and improves memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15020–15025. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.15020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beshay E, Croze F, Prud’homme GJ. The phosphodiesterase inhibitors pentoxifylline and rolipram suppress macrophage activation and nitric oxide production in vitro and in vivo. Clin Immunol. 2001;98:272–279. doi: 10.1006/clim.2000.4964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehmer T, Lindenau J, Haid S, Dichgans J, Schulz JB. Deficiency of inducible nitric oxide synthase protects against MPTP toxcity in vivo. J Neurochem. 2000;74:2213–2216. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0742213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinter H, Tse J, Halks-Miller M, Asarnow D, Onuffer J, Faulds D, Mitrovic B. The type IV phosphodiesterase specific inhibitor mesopram inhibits experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in rodents. J Neuroimmun. 2000;108:136–146. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(00)00265-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frim DM, Uhler RA, Galpern WR, Beal MF, Breakefield XO, Isacson O. Implanted fibroblasts genetically engineered to produce brain-derived neurotrophic factor prevent 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium toxicity to dopaminergic neurons in the rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5104–5108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.5104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsberg MD, Becker DA, Busto R, Belayev A, Zhang Y, Khoutorova L, Ley JJ, Zhao W, Belayev L. Stilbazulenyl nitrone, a novel antioxidant, is highly neuroprotective in focal ischemia. Ann Neurol. 2003;54(3):330–42. doi: 10.1002/ana.10659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong B, Vitolo OV, Trinchese F, Liu S, Shelanski M, Arancio O. Persistent improvement in synaptic and cognitive functions in an Alzheimer mouse model after rolipram treatment. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1624– 1634. doi: 10.1172/JCI22831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulley P, MHartikka J, Abdel’Al S, Engels P, Buerki HR, Wiederhold KH, Muller T, Kelly P, Lowe D, Lubbert H. Inhibitors of type IV phosphodiesterases reduce the toxicity of MPTP in substantia nigra neurons in vivo. Eur J Neurosci. 1995;7:2431–2440. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1995.tb01041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H-T, Chang Y-C, Wang L-Y, Wang S-T, Huang C-C, Ho C-J. cAMP response element-binding protein activation in ligation preconditioning in neonatal brain. Ann Neurol. 2004;56:611–623. doi: 10.1002/ana.20259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberatore GT, Jackson-Lewis V, Vukosavic S, Mandir AS, Vila M, McAuliffe WG, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Przedborski S. Inducible nitric oxide synthase stimulates dopaminergic neurodegeneration in the MPTP model of Parkinson’s disease. Nat Med. 1999;5:1354–1355. doi: 10.1038/70978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little JR, Cook A, Lesser RP. Treatment of acute focal cerebral ischemia with dimethyl sulfoxide. Neurosurgery. 1981;9:34–39. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198107000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little JR, Spetzler RF, Roski RA. Ineffectiveness of DMSO in treating experimental brain ischemia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1983;411:269–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1983.tb47308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie SJ, Houslay MD. Action of rolipram on specific PDE4 cAMP phosphodiesterase isoforms and on the phosphorylation of cAMP-response-element-binding protein (CREB) and p38 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase in U937 monocytic cells. Biochem J. 2000;347:571–578. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3470571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez I, Puerta C, Redondo C, Garcia-Moreno A. Type IV phosphodiesterase inhibition in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis of Lewis rats: Sequential gene expression analysis of cytokines, adhesion molecules and the inducible nitric oxide synthase. J Neurol Sci. 1999;164:13–23. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(99)00050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti B, Bertetotti C, Contestabile A. Subchronic rolipram delivery activates hippocampal CREB and Arc, enhances retention and slows down extinction of conditioned fear. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:278–286. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naoi M, Takahashi T, Nagatsu T. A fluorometric determination of N-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium ion, using high-performance liquid chromatograpgy. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:540–545. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90431-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porritt MJ, Batchelor PE, Howells DW. Inhibiting BDNF expression by antisense oligonucleotide infusion causes loss of nigral dopaminergic neurons. Exp Neurol. 2005;192:226–234. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repine JE, Pfenninger OW, Talmage DW. Dimethyl sulfoxide prevents DNA nicking mediated by ionizing radiation or iron/hydrogen peroxide-generated hydroxyl radical. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:1001–1003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.2.1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu S, Simon RP, Graham SH. Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) treatment reduces infarction volume after permanent focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Neurosci Lett. 1997;239:125–127. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00915-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimohata M, Shimohata T, Igarashi S, Naruse S, Tsuji S. Interference of CREB-dependent transcriptional activation by expanded polyglutamine stretches – augmentation of transcriptional activation as a potential therapeutic strategy for polyglutamine diseases. J Neurochem. 2005;93:654–663. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukahara T, Takeda M, Shimohama S, Ohara O, Hashimoto N. Effects of brain-derived nerotrophic factor on 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-induced parkinsonism in monkeys. Neurosurgery. 1995;37:733–739. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199510000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu DC, Teismann P, Tieu K, Vila M, Jackson-Lewis V, Ischiropoulos H, Przedborski S. NADPH oxidase mediates oxidative stress in the 1-methyl-4-phenyl- 1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine model of Parkinson’s Disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:6145–6150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0937239100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Calingasan NY, Chen J, Ley JJ, Becker DA, Beal MF. A novel azulenyl nitrone antioxidant protects against MPTP and 3-nitropropionic acid neurotoxicities. Exp Neurol. 2005;191:86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Yang L, Konishi Y, Maeda N, Sakanaka M, Tanaka J. Suppressive effects of phosphodiesterase type IV inhibitors on rat cultured microglial cells: comparison with other types of camp-elevating agents. Neuropharmacology. 2002;42:262–269. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00174-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]