Abstract

Background

Chromosome 15q24 microdeletion syndrome is a rare genomic disorder characterised by intellectual disability, growth retardation, unusual facial morphology and other anomalies. To date, 20 patients have been reported; 18 have had detailed breakpoint analysis.

Aim

To further delineate the features of the 15q24 microdeletion syndrome, the clinical and molecular characterisation of fifteen patients with deletions in the 15q24 region was performed, nearly doubling the number of reported patients.

Methods

Breakpoints were characterised using a custom, high-density array comparative hybridisation platform, and detailed phenotype information was collected for each patient.

Results

Nine distinct deletions with different breakpoints ranging in size from 266 kb to 3.75 Mb were identified. The majority of breakpoints lie within segmental duplication (SD) blocks. Low sequence identity and large intervals of unique sequence between SD blocks likely contribute to the rarity of 15q24 deletions, which occur 8–10 times less frequently than 1q21 or 15q13 microdeletions in our series. Two small, atypical deletions were identified within the region that help delineate the critical region for the core phenotype in the 15q24 microdeletion syndrome.

Conclusion

The molecular characterisation of these patients suggests that the core cognitive features of the 15q24 microdeletion syndrome, including developmental delays and severe speech problems, are largely due to deletion of genes in a 1.1–Mb critical region. However, genes just distal to the critical region also play an important role in cognition and in the development of characteristic facial features associated with 15q24 deletions. Clearly, deletions in the 15q24 region are variable in size and extent. Knowledge of the breakpoints and size of deletion combined with the natural history and medical problems of our patients provide insights that will inform management guidelines. Based on common phenotypic features, all patients with 15q24 microdeletions should receive a thorough neurodevelopmental evaluation, physical, occupational and speech therapies, and regular audiologic and ophthalmologic screening.

Keywords: Academic medicine, clinical genetics, epilepsy and seizures, cytogenetics, molecular genetics, genetics, copy-number, developmental, epilepsy and seizures, neurology, neuroophthalmology, cancer: breast, cancer: colon, genetic screening/counselling, obstetrics and gynaecology

Introduction

The introduction of genome-wide approaches to identify deletions and duplications throughout the human genome has facilitated the discovery of numerous novel causes for intellectual disability (ID), autism, and other developmental disorders.1 2 In the clinical work-up of undiagnosed intellectual disability, array comparative genomic hybridisation (aCGH) has the ability to make a diagnosis in 10–30% of cases. Recently, an international consensus has been reached that chromosomal microarray should be a first-tier clinical diagnostic test for individuals with developmental disabilities or congenital anomalies.3 It has also been shown that in many patients abnormal chromosomal microarray testing influences medical care by precipitating specialty referral, diagnostic imaging, or specific laboratory testing.4 For patients with well known classical microdeletion syndromes such as 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, Prader-Willi syndrome and Williams syndrome, extensive data exist on clinical features observed in patients, and management guidelines have been developed. For newly discovered microdeletion/duplication syndromes, case reports and family support groups such as Unique, the Rare Chromosome Disorder Support Group (http://www.rarechromo.org), offer limited resources. Systematic characterisation of newly reported patients provides much needed information for clinicians and patients.

Recurrent microdeletion of chromosome 15q24 was described as a new genomic disorder after identification of patients with overlapping deletions, intellectual disability and similar clinical features.5 The 15q24 region is a complex genomic region with at least five segmental duplication (SD) blocks, also known as low copy repeats. These SD blocks, referred to as breakpoints A, B, C, D, and E, have varying amounts and degrees of sequence similarity to one another and can facilitate non-allelic homologous recombination (NAHR) at meiosis, leading to deletion of the intervening sequence. NAHR between different SD blocks can lead to deletions of various sizes and with different breakpoints. To date, 18 patients with 15q24 deletions and detailed breakpoint analysis have been described in the medical literature.6–15 A characteristic 15q24 phenotype has been delineated with major features that include growth retardation, microcephaly, dysmorphic facial features, genital anomalies, and digital anomalies. Here we report clinical and molecular data for 15 patients with deletions in the 15q24 region, nearly doubling the number of reported patients. Among these, there are nine distinct deletions with different breakpoints, and two patients carry small, atypical deletions within the region that help delineate the critical region for core phenotypes in the 15q24 microdeletion syndrome. Finally, we offer recommendations for evaluation and management of patients with 15q24 deletion syndrome.

Subjects and methods

Study subjects

Fifteen individuals (10 males and five females) with a 15q24 deletion were included in this study. Fourteen cases were initially ascertained based on clinical aCGH or single nucleotide polymorphism microarray analysis. The deletion in patient 13 was initially identified using a custom bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) array as previously described.5 Clinical information and facial photographs were obtained from the referring clinicians or families. Several of the patients met through the ‘Unique’ support group and shared information between themselves and their clinicians. This study was approved by institutional review boards at the University of Washington, Rhode Island Hospital, and Spokane.

Molecular studies

Refinement of the 15q24 deletion intervals in 13/15 cases for which DNA was available was conducted using a custom high density oligonucleotide array with 7450 probes in the 15q24 region (hg18, chr15: 69 000 000–77 000 000) with an average probe spacing of 1074 bp. When possible, parent-of-origin studies were performed using microsatellite markers within the deleted region.

Results

Identification of novel 15q24 deletions

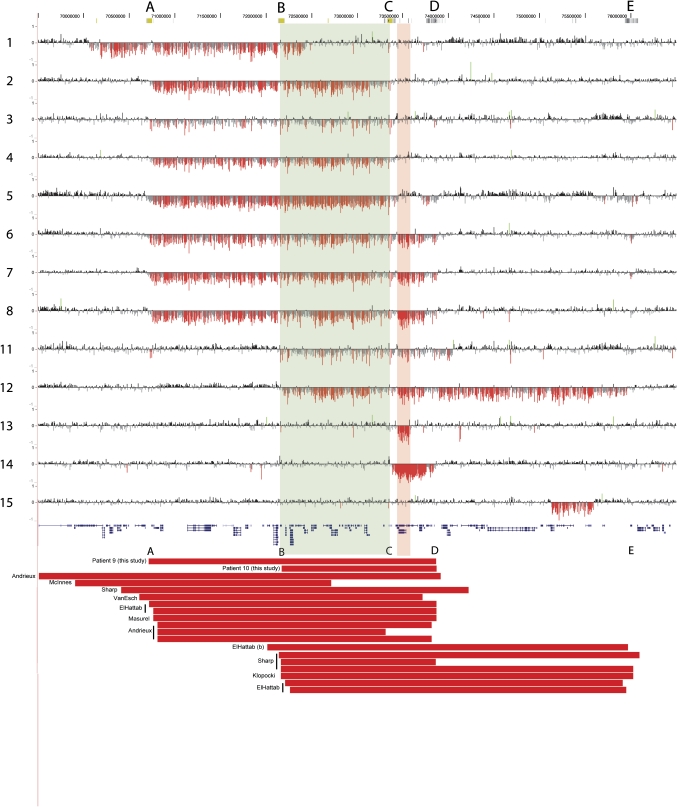

We report 15 patients with deletions in the 15q24 region (table 1, figure 1). Deletions range from 266 kb to 3.75 Mb in size. The majority of deletions have both breakpoints in one of the SD blocks in this region of chromosome 15. We have adopted the nomenclature put forth by El-Hattab and colleagues8 for the SD blocks in the region and will refer to them as breakpoints A–E (figure 1, table 1). Four patients have nearly identical 2.6 Mb deletions with breakpoints in A and C, and four patients have 3.1 Mb deletions with breakpoints in A and D. In addition, we identified deletions with breakpoints in B and D (n=1), B and E (n=1), and C and D (n=1). Four patients have atypical deletions with only one or no breakpoints within segmental duplications (figure 1, table 1).

Table 1.

Frequency of 15q24 deletions with different breakpoints

| Breakpoints | Deletion size | N (this study) | N (literature)6,8,10–14 | Total N | Size, identity of flanking SDs* |

| A–C | 2.6 Mb | 4 | 1 | 5 | 25 kb, >98% |

| A–D | 3.1 Mb | 4 | 6 | 10 | 21 kb, 94% |

| B–D | 1.7 Mb | 1 | 1 | 2 | – |

| B–E | 3.8 Mb | 1 | 5 | 6 | 42 kb, >95% |

| C–D | 500 kb | 1 | 0 | 1 | 27 kb, >93% |

| Atypical | Varies | 4 | 4 | 8 | |

| Total | 15 | 17 | 32 |

Based on NCBI Build 36/hg18, the size and percentage identity of the longest stretch of directly oriented, highly homologous sequence is listed.

Figure 1.

High density array comparative genomic hybridisation (aCGH) data for the 15q24 region (NCBI Build 36, chr15:69 500 000–76 500 000 shown) for 13 new patients. Breakpoints are labelled as breakpoints A through E as described in the text. For each individual, deviations of probe log2 ratios from zero are depicted by vertical grey/black lines, with those exceeding a threshold of 1.5 standard deviations from the mean probe ratio coloured green and red to represent relative gains (duplications) and losses (deletions), respectively. Genes are depicted in blue below the aCGH data. The red bars represent the deletions for two patients (9 and 10) for which additional DNA was unavailable as well as previously published cases. The breakpoints are as described in clinical reports (patients 9 or 10) or within the publications noted.

Atypical deletions

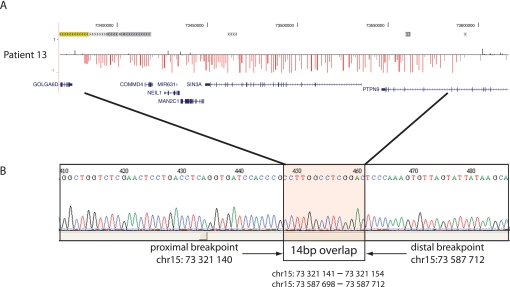

We identified four atypical deletions that have not yet been reported in the literature. Patient 1 has a large de novo deletion with both breakpoints in unique sequence. The proximal breakpoint in this patient is in unique sequence proximal to breakpoint A, and the distal breakpoint lies between B and C. The deletion carried by patient 11 has a proximal breakpoint in B and distal breakpoint that is distal to D. The smallest deletion we detected was a de novo 266 kb deletion in patient 13 that involves only five genes (COMMD4, NEIL1, MAN2C1,SIN3A, and PTPN9) within the region between breakpoints C and D. Sequencing the breakpoints of this small deletion revealed that it likely occurred by Alu-Alu recombination (figure 2). Finally, we identified one severely affected patient (patient 15) with a clinical diagnosis of Johanson-Blizzard syndrome who has a 470 kb atypical distal 15q24 deletion that is within the region between D and E but has breakpoints in unique sequence. The significance of this deletion is unclear, and parents were unavailable to determine inheritance. In addition, patient 14 has a small, de novo deletion with breakpoints at C and D (chr15: 73.38–73.88 Mb); although both breakpoints are in SD blocks, this deletion has not been previously reported to our knowledge.

Figure 2.

Breakpoint sequence for patient 13, who has the smallest deletion detected in our series. (A) Array comparative genomic hybridisation data for the deletion in patient 13, as displayed in figure 1. Segmental duplications are shown at the top. Note that the breakpoints lie outside of the segmental duplication regions. (B) Sequence data across the breakpoint revealed that each breakpoint was located within an Alu sequence: an AluSx at the proximal breakpoint and an AluJo at the distal breakpoint. Comparison of the two sequences revealed a 14 bp stretch of perfect sequence identity at the breakpoints.

Clinical details of the study subjects

We were able to obtain clinical information for all 15 patients (table 2, figure 3). In order to assess for possible genotype–phenotype correlations, we grouped patients according to deletion size and location. We will first discuss features in patients whose deletion includes the proposed critical region between breakpoints B–C (patients 2–12). We will then consider patients whose deletion includes only the region between breakpoints C–D (patient 13 and 14). Finally, we consider clinical features in patient 1, whose deletion involves only the proximal 300 kb of the B–C region. Because the inheritance—and therefore clinical significance—of the deletion in patient 15 is not known, we will not discuss this patient further.

Table 2.

Clinical features of patients with deletions of 15q24

| Patient | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| Coord (Mb) | 70.06–72.43 | 70.73–73.33 | 70.73–73.33 | 70.73–73.33 | 70.73–73.33 | 70.73–73.89 | 70.73–73.89 | 70.73–73.89 |

| Breakpoints | Atypical | A–C | A–C | A–C | A–C | A–D | A–D | A–D |

| Size (# genes) | 2.37 Mb (33 genes) | 2.60 Mb (45 genes) | 2.60 Mb (45 genes) | 2.60 Mb (45 genes) | 2.60 Mb (45 genes) | 3.16 Mb (>50 genes) | 3.16 Mb (>50 genes) | 3.16 Mb (>50 genes) |

| Inheritance | De novo (maternal) | Unknown | De novo | De novo | De novo | Unknown | De novo (maternal) | De novo |

| Age at diagnosis | 29 years | 6 years | 7 years | 12 years | 30 months | 33 months | 5 years | 30 months |

| Growth |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Motor development | Mild delay | Receives OT, PT | Moderate delay |

|

|

Walks with assistance, 33 m | Walked at 30 m | Walked at 30 m |

| Cognitive | IQ 47 at 15 y | Mod to severe ID | Moderate ID | Global developmental delay | Moderate ID | Global developmental delay | ||

| Speech | Significant expressive speech delay | 2 words at 7 years | Non-verbal | 20 words at 32 m | Babbles, blows raspberries | Few words at 2 years, lost with increased seizure activity; some gestures | Non-verbal | |

| Face | Prominent philtrum, high palate, retrognathia | Broad mouth, broad nasal tip | Small mandible, widely spaced eyes | Prominent nasal bridge, full nasal tip, wide mouth, upslanting palpebral fissures | Non-dysmorphic | Pierre-Robin sequence, prominent forehead, small mouth | Long slim face, bilateral epicanthic folds, long smooth philtrum, thin upper vermillion, small mouth | Long face, high anterior hairline, downslanting palpebral fissures, epicanthic folds, long philtrum |

| Eyes | Strabismus, R amblyopia, high hyperopia | Chorioretinal coloboma, microphthalmia | Pseudo esotropia, L exotropia | Strabismus | Exotropia | Legally blind, L 20/540, R 20/80 | Anisocoria with L pupil > R pupil | |

| Ears | Low-set, dysplastic | Normal | PE tubes | Large fleshy earlobes, PE tubes | Conductive hearing loss | Moderate SNHL | Prone to ear infections | Conductive hearing loss, PE tubes |

| Brain, neurologic exam | MRI—3 small lesions of periventricular nodular heterotopia; one seizure at 25 years, EEG with paroxysmal activity R central region | Hypotonia | Normal exam | Focal seizures since 3 years, hypotonia | MRI normal; hypotonic with brisk reflexes, normal strength, wide based gait | MRI at 34 m showed subtle closed lip schizencephaly or grey matter heterotopia in the frontal lobe | MRI of brain, spine normal; L temporal lobe epilepsy with generalisation | Hypotonia, normal brain MRI |

| Psychiatric | Impulsivity, ADHD | Autistic disorder; poor social awareness | Autism, aggressive behaviours | Minimal eye contact | Happy personality | Happy personality, affectionate | ||

| Cardiac | Normal echo | Normal echo, ECG | PDA, PFO, PPS | Murmur, not evaluated | Normal | Normal echo, ECG, bradycardia during seizures | Normal | |

| GI/GU | Normal abdominal, renal, pelvic US | Normal | Constipation | G-tube and fundoplication, starting to put food around her mouth | Imperforate anus | Normal | ||

| Skeletal | Brachydactyly type E | Lumbar lordosis, pes planus | Ligamentous laxity | Decreased carrying angle at elbows, pes planus, osteopenia, long tapered fingers, long toes | Long flexible flat feet with significant pronation | Long fingers | Pectus excavatum, long fingers and feet, joint laxity | |

| Skin | Hypopigmented macules on abdomen and neck | Eczema, 3 CALs | 2 CALs | Small CAL on left leg | Dimples over elbow, shoulders, sacrum, knees |

| Patient | 9 | 10 | 11† | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | Previously published |

| Coord (Mb) | 70.73–73.74* | 72.22–73.81* | 72.20–74.04 | 72.20–75.95 | 73.32–73.59 | 73.38–73.88 | 75.12–75.60 | |

| Breakpoints | A–D | B–D | B-unique | B–E | Atypical | C–D | Atypical | |

| Size (# genes) | 3.01 Mb (>50 genes) | 1.59 Mb (36 genes) | 1.84 Mb (40 genes) | 3.75 Mb (>50 genes) | 266 kb (5 genes) | 500 kb (11 genes) | 480 kb (4 genes) | |

| Inheritance | De novo | Unknown | De novo (maternal) | De novo | De novo | De novo | Unknown | |

| Age at diagnosis | 6 years | 18 years | 6 years | 30 months | 20 years | 9.5 years | 24 years | |

| Growth |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Motor development |

|

|

|

Mild delay | Normal | Severe delay | 18/18 with developmental delays | |

| Cognitive | Mild to moderate ID | Moderate global developmental delay | IQ 65 | IQ 73 | Severe ID | 18/18 delayed | ||

| Speech | Non-verbal | Speaks in sentences | <12 words at 6 years | Some sounds, signs | First words at 4 years, reasonable speech after | First words at 1 year | Non-verbal | 9/18 with severe speech delays |

| Face | High anterior hairline, full lips, epicanthi, flared medial eyebrows | Thick medial eyebrows, bilateral epicanthi, retrognathia | Brachycephaly, broad forehead, flared medial eyebrows | Round face, flared medial eyebrows | Telecanthus, bilateral epicanthi | Low anterior hairline, broad nasal tip, smooth philtrum, narrow palpebral fissures, bilateral epicanthi, flat zygomatic arches | 13/18 high forehead | |

| Eyes | Normal exam | Normal vision | Anisocoria, normal vision | Normal vision | Normal exam | 6/18 strabismus | ||

| Ears | Low-set ears, PE tubes | Thick anteverted lobes, R profound and L progressive SNHL | Cup-shaped ears, PE tubes; moderate HL in one twin | PE tubes | Profound SNHL |

|

||

| Brain, neurologic exam | MRI brain normal; hypotonic | MRI normal; tethered cord | Normal exam aside from delays | MRI normal; hypotonic | MRI—colpocephaly, mild dilatation of lateral ventricles, hypoplastic CC; normal EEG | Normal exam aside from delays and behaviour |

|

|

| Psychiatric | Autism | Food seeking behaviour | Obsessive compulsive behaviours | Poor attention, possible Asperger syndrome | Aggression, self stimulatory behaviour | 4/18 ADHD, hyperactivity | ||

| Cardiac | Normal ECG | Pulmonic stenosis | Normal echo | 4/18 cardiac malformation | ||||

| GI/GU | Normal renal US, mild hypospadias | Constipation, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease | Cryptorchidism, hypospadias, bilateral inguinal hernias |

|

||||

| Skeletal | Thenar hypoplasia | Mild kyphoscoliosis, camptodactyly of 4th fingers, pronounced 5th finger brachydactyly with bilateral shortening of 5th middle phalanges, absent epiphyses, broad great toes with L hallux valgus | Small fingers, pes planus | Hyperextensible joints | Hyperextensible joints, short 5th metacarpals, mild cutaneous syndactyly of toes 2–3–4, small 5th toenails | Bilateral short 5th fingers, bone age delayed 1 year | Proximally placed thumbs, short 5th fingers, mild camptodactyly of fingers 3–4, broad feet with short phalanges, disproportionate short stature |

|

| Skin | Acanthosis nigricans | 2 CALs | 3/18 CALs |

From clinical report—DNA unavailable for high-density array.

One of monozygotic twins who both have the same 15q24 deletion and share the majority of clinical features listed.

ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; CAL, café-au-lait macule; CC, corpus callosum; EEG, electroencephalogram; GI, gastrointestinal; GU, genitourinary; Ht, height; ID, intellectual disability; L, left; OFC, occipitofrontal circumference; OT, occupational therapy; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; PE, pressure equalisation; PFO, patent foramen ovale; PPS, peripheral pulmonic stenosis; PT, physical therapy; R, right; SNHL, sensorineural hearing loss; US, ultrasound; Wt, weight.

Figure 3.

Clinical features of patients with 15q24 deletions. Photographs and hand radiographs of patient 1 (A) showing pronounced shortening of the fourth metacarpals; photographs of patient 4 (B), patient 6 at 9 months and 2 years (C), patient 7 at 13 months and 6 years (D), patient 9 (E), patient 10 (F), patient 12 (G), and patient 14 (H).

Deletions involving region B–C

Eleven patients had deletions including the 1.1 Mb proposed critical region between breakpoints B–C. The subjects were diagnosed from immediately after birth to young adulthood. Most were born full term after uncomplicated pregnancies. In the newborn period, several had feeding difficulties or failure to thrive. One patient was born with Pierre Robin sequence and required prolonged neonatal intensive care unit stay.

In terms of development, the majority of patients had motor delays. For eight patients who reported the age at which independent walking was achieved, this milestone was achieved between 18 and 33 months (average 26 months). Ten of 11 patients had significant expressive speech delay with three described as non-verbal. Intellectual disability ranged from mild to severe. Dysmorphic facial features included high anterior hairline, prominent forehead, and epicanthal folds. Four patients had deep-set eyes. Digital anomalies included short fifth fingers with fourth finger camptodactyly in one patient and thenar hypoplasia in another. Three patients were described as having long fingers.

Neurologically, several patients had hypotonia. Seven of 11 patients in this group had had a brain MRI; six had normal results. One patient had subtle abnormalities in the frontal lobe. Two patients had reported at least one seizure. Three patients were diagnosed with autism.

Of note, seven patients in this group had eye or vision abnormalities including strabismus (n=3), blindness (n=1), anisocoria (n=2), and coloboma (n=1). Four patients suffered from hearing loss, and six reported recurrent ear infections, ear effusions or ear tubes.

Cardiac evaluations were performed in seven patients. One patient had pulmonic stenosis, and another had a patent foramen ovale, patent ductus arteriosus, and peripheral pulmonic stenosis. Though genital abnormalities have been commonly reported in patients with 15q24 deletions, only 1/8 males with deletions involving region B–C had hypospadias. One female patient had an imperforate anus. A few of the patients had endocrine problems. One patient had delayed puberty and insulin dependent diabetes, and another patient had acanthosis nigricans. Two patients had obesity later in life.

Deletions involving only region C–D

Two patients were found to have small, previously unreported deletions between breakpoints C and D. As described above (Atypical deletions), patient 13 has a de novo 266 kb deletion that involves only five genes. Patient 14 has a de novo 500 kb deletion with breakpoints in the flanking SDs. Both of these patients have borderline to mild intellectual disability with IQ scores of 65 and 73, respectively. In addition, although patient 13 did not speak until age 4, both patients now have reasonable speech and communication skills. Interestingly, both patients have dysmorphic features similar to patients with deletions of the B–C region including large forehead, and both have short fifth fingers.

Patient 1: proximal deletion

Patient 1 has a 2.37 Mb deletion that begins proximal to BP-A and extends only 300 kb into the 1.1 Mb critical region. She presented with mild motor delays, an IQ of 47 at 15 years of age, dysmorphic features (figure 3), periventricular nodular heterotopia, and brachydactyly type E. The brachydactyly was not present in other family members, suggesting that one of more genes in the large, proximal deletion may be responsible.

Inheritance

In 11 cases, parents were available for analysis, and in each case the deletion was de novo. In four cases, we were unable to determine inheritance. In addition, we determined that the deletion originated on the maternal chromosome in three cases. We were unable to determine parent of origin for the remaining cases.

Discussion

The 15q24 microdeletion syndrome is a newly characterised microdeletion syndrome. We performed an extensive clinical and molecular characterisation of 15 patients. In the majority of cases the microdeletion was initially identified by clinical aCGH performed because of multiple congenital anomalies and/or intellectual disability. Of these, eight patients were identified at Signature Genomic Laboratories between November 2007 and December 2009. During this period, 21 820 patients were evaluated. This suggests that, despite a genomic architecture that predicts recurrent rearrangement, deletions in the region account for only 3–4/10 000 cases that are sent for clinical aCGH studies. In comparison, the rate at which recurrent deletions of 15q13 or 1q21 were identified during the same time period was eightfold to 10-fold higher. The larger interval of unique sequence between SD blocks (2.6–3.8 Mb compared to 1.3–1.5 Mb for 1q21 and 15q13) and the lower sequence identity between SD blocks in direct orientation likely contribute to the lower frequency of 15q24 deletion events.

The 15q24 region contains several clusters of segmental duplications that are thought to facilitate non-allelic homologous recombination resulting in recurrent deletion.8 16 The deletions in our series of patients, which ranged from 266 kb to 3.75 Mb, support this assertion. Eleven of the 15 deletions had both breakpoints in segmental duplications flanking the deleted region. Three patients had deletions with both breakpoints in unique sequence. One deletion had one breakpoint in unique sequence and the other in a segmental duplication. The most common deletions in our series, found in four patients each, were the 2.6 Mb deletion between breakpoints A and C and the 3.1 Mb deletion between breakpoints A and D (table 1, figure 1). Evaluation of previously reported deletions suggest that the deletion between breakpoints A and D occurs most frequently and accounts for about one third of deletions in the region (10/32 reported; table 1). Deletions between A and C and between B and E occur with approximately equal frequency, accounting for 15–20% of deletions. The breakpoint combinations are consistent with an NAHR mechanism between directly oriented segmental duplications. Breakpoints A and C share a ∼25 kb directly oriented sequence block with >98% sequence identity. Similarly, breakpoints A and D share a ∼21 kb directly oriented sequence block with 94% identity. Breakpoints B and E share a 42 kb stretch of >95% identity, and C and D share a 27 kb stretch of >93% identity. Conversely, there are no large stretches of highly homologous and directly oriented repeats between blocks A and B, A and E, B and C, or B and D, suggesting the deletions are much less likely to occur via NAHR between these blocks.

Our analysis of the clinical features in our series of patients with 15q24 deletions is largely consistent with previous reports.6 8 9 11 12 14 Common features, present in more than 50% of the patients and that should prompt consideration of this diagnosis, include dysmorphic facial features, including a prominent forehead, high anterior hairline, prominent nasal bridge, and micrognathia. Other features include deep-set eyes, strabismus, or other ocular anomalies. Short metacarpals and proximally placed thumbs may also be a clue to diagnosis. A history of failure to thrive and developmental delay is typical. Severe speech delay or absence of speech is a consistent feature in patients with typical deletions. Diaphragmatic hernia has been reported in some patients with the deletion,11 12 but no patients in our series reported this. Similarly, we found only 1/8 males with hypospadias.

It is important to note that we identified nine distinct deletions with different breakpoints in 15 patients. In fact, the deletions in patients 1–5 have no overlap with the deletions in patients 13, 14, and 15. Combining the deletions in our series with those in the literature, 28% of reported deletions are ‘private’ mutations seen in a single patient. The vast majority of reported deletions include the region between breakpoints B and C and most also include the C–D region. We identified two patients with small, atypical deletions that lie within the region between breakpoints C and D. Notably, both of these patients had only mild or borderline ID, with IQ scores of 65 and 73. Unlike the majority of patients with larger deletions, both have developed reasonable speech. This suggests that the severity of the core cognitive deficits of the 15q24 microdeletion syndrome are due to deletion of one or more genes with the 1.1 Mb critical region between breakpoints B and C containing 24 RefSeq genes. However, given the delays and dysmorphic features in our two atypical cases, some or all of the eight genes between C and D, and indeed the five genes deleted in case 13, must be important for normal development and behaviour. Furthermore, review of photographs for patients with deletions that do not include the region between C and D (patients 13 and 14 from this study, patient 3 in Andrieux et al6 and McInnes et al13) suggest that their facial features are slightly less striking. This would suggest that some of the genes in the C–D region are important for the syndromic facies described for 15q24 deletions. On the other hand, we found that patients with deletions including the BP B–C region were more likely to have eye abnormalities. In addition, cardiac features and seizures were noted in several patients with deletions including the B–C region, but not in patients 1, 13 or 14, whose deletions do not include the critical region.

Based on common features of our patients, we feel that certain management recommendations can be made. Since there is a high incidence of eye and ear anomalies, ophthalmological evaluation and audiology evaluation should be routine referrals. Additional screening for genitourinary and cardiac anomalies should be considered. A formal developmental evaluation and careful screening for autism and related entities could help diagnose these potential problems early and initiate targeted services. Families should be counselled to observe closely for seizures, since there appears to be an increased risk in these patients. The families of our patients have reported that support group information is especially helpful to them.

In conclusion, the molecular and clinical characterisation of 15 individuals with the 15q24 microdeletion syndrome further defines the phenotypic features associated with this novel syndrome and provides further insight into the critical region for core features of this syndrome.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the patients and families who have participated in this study, with special thanks to Jason and Marissa Campbell, the Sjostrands, Samantha and Jerry Torres, and Carol Smith.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by a Burroughs Wellcome Fund Career Award for Medical Scientists, grant number 1007607 (HCM); by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (EEE); and by the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre (HF).

Competing interests: JAR and AL are employees of Signature Genomics, a subsidiary of PerkinElmer.

Ethics approval: University of Washington, Rhode Island Hospital, Spokane.

Contributors: Wrote the manuscript: HCM, JAR, NS; edited the manuscript: AL, EEE; conceived the study: HCM, JAR, NS, EEE; performed experiments: HCM, JC; provided clinical data: JAR, AS, VAC, RH, HF, LW, PW, EM, RS, AO, JZ, KK, MH, SB, JK, JG, SZ, VB, WS, RS, LP, KNR, SJA, JS.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Custom array information is available upon request.

References

- 1.Mefford HC, Eichler EE. Duplication hotspots, rare genomic disorders, and common disease. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2009;19:196–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slavotinek AM. Novel microdeletion syndromes detected by chromosome microarrays. Hum Genet 2008;124:1–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller DT, Adam MP, Aradhya S, Biesecker LG, Brothman AR, Carter NP, Church DM, Crolla JA, Eichler EE, Epstein CJ, Faucett WA, Feuk L, Friedman JM, Hamosh A, Jackson L, Kaminsky EB, Kok K, Krantz ID, Kuhn RM, Lee C, Ostell JM, Rosenberg C, Scherer SW, Spinner NB, Stavropoulos DJ, Tepperberg JH, Thorland EC, Vermeesch JR, Waggoner DJ, Watson MS, Martin CL, Ledbetter DH. Consensus statement: chromosomal microarray is a first-tier clinical diagnostic test for individuals with developmental disabilities or congenital anomalies. Am J Hum Genet 2010;86:749–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coulter ME, Miller DT, Harris DJ, Hawley P, Picker J, Roberts AE, Sobeih MM, Irons M. Chromosomal microarray testing influences medical management. Genet Med 2011;13:770–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharp AJ, Hansen S, Selzer RR, Cheng Z, Regan R, Hurst JA, Stewart H, Price SM, Blair E, Hennekam RC, Fitzpatrick CA, Segraves R, Richmond TA, Guiver C, Albertson DG, Pinkel D, Eis PS, Schwartz S, Knight SJ, Eichler EE. Discovery of previously unidentified genomic disorders from the duplication architecture of the human genome. Nat Genet 2006;38:1038–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andrieux J, Dubourg C, Rio M, Attie-Bitach T, Delaby E, Mathieu M, Journel H, Copin H, Blondeel E, Doco-Fenzy M, Landais E, Delobel B, Odent S, Manouvrier-Hanu S, Holder-Espinasse M. Genotype-phenotype correlation in four 15q24 deleted patients identified by array-CGH. Am J Med Genet A 2009;149A:2813–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cushman LJ, Torres-Martinez W, Cherry AM, Manning MA, Abdul-Rahman O, Anderson CE, Punnett HH, Thurston VC, Sweeney D, Vance GH. A report of three patients with an interstitial deletion of chromosome 15q24. Am J Med Genet A 2005;137:65–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-Hattab AW, Smolarek TA, Walker ME, Schorry EK, Immken LL, Patel G, Abbott MA, Lanpher BC, Ou Z, Kang SH, Patel A, Scaglia F, Lupski JR, Cheung SW, Stankiewicz P. Redefined genomic architecture in 15q24 directed by patient deletion/duplication breakpoint mapping. Hum Genet 2009;126:589–602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klopocki E, Graul-Neumann LM, Grieben U, Tonnies H, Ropers HH, Horn D, Mundlos S, Ullmann R. A further case of the recurrent 15q24 microdeletion syndrome, detected by array CGH. Eur J Pediatr 2008;167:903–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Masurel-Paulet A, Callier P, Thauvin-Robinet C, Chouchane M, Mejean N, Marle N, Mosca AL, Ben Salem D, Giroud M, Guibaud L, Huet F, Mugneret F, Faivre L. Multiple cysts of the corpus callosum and psychomotor delay in a patient with a 3.1 Mb 15q24.1q24.2 interstitial deletion identified by array-CGH. Am J Med Genet A 2009;149A:1504–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharp AJ, Selzer RR, Veltman JA, Gimelli S, Gimelli G, Striano P, Coppola A, Regan R, Price SM, Knoers NV, Eis PS, Brunner HG, Hennekam RC, Knight SJ, de Vries BB, Zuffardi O, Eichler EE. Characterization of a recurrent 15q24 microdeletion syndrome. Hum Mol Genet 2007;16:567–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Esch H, Backx L, Pijkels E, Fryns JP. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia is part of the new 15q24 microdeletion syndrome. Eur J Med Genet 2009;52:153–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McInnes LA, Nakamine A, Pilorge M, Brandt T, Jimenez Gonzalez P, Fallas M, Manghi ER, Edelmann L, Glessner J, Hakonarson H, Betancur C, Buxbaum JD. A large-scale survey of the novel 15q24 microdeletion syndrome in autism spectrum disorders identifies an atypical deletion that narrows the critical region. Molecular autism 2010;1:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Hattab AW, Zhang F, Maxim R, Christensen KM, Ward JC, Hines-Dowell S, Scaglia F, Lupski JR, Cheung SW. Deletion and duplication of 15q24: molecular mechanisms and potential modification by additional copy number variants. Genet Med 2010;12:573–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marshall CR, Noor A, Vincent JB, Lionel AC, Feuk L, Skaug J, Shago M, Moessner R, Pinto D, Ren Y, Thiruvahindrapduram B, Fiebig A, Schreiber S, Friedman J, Ketelaars CE, Vos YJ, Ficicioglu C, Kirkpatrick S, Nicolson R, Sloman L, Summers A, Gibbons CA, Teebi A, Chitayat D, Weksberg R, Thompson A, Vardy C, Crosbie V, Luscombe S, Baatjes R, Zwaigenbaum L, Roberts W, Fernandez B, Szatmari P, Scherer SW. Structural variation of chromosomes in autism spectrum disorder. Am J Hum Genet 2008;82:477–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bailey JA, Gu Z, Clark RA, Reinert K, Samonte RV, Schwartz S, Adams MD, Myers EW, Li PW, Eichler EE. Recent segmental duplications in the human genome. Science 2002;297:1003–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]